Keywords: endothelial cells, flow-induced vasodilation, shear stress, vascular myogenic response, vascular smooth muscle cells

Abstract

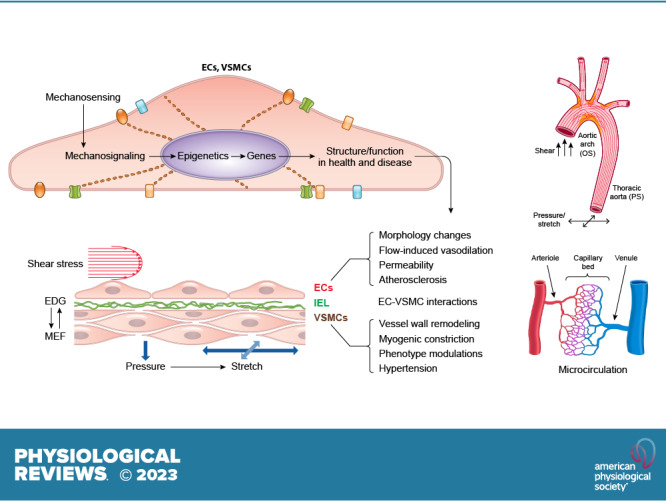

This review aims to survey the current state of mechanotransduction in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and endothelial cells (ECs), including their sensing of mechanical stimuli and transduction of mechanical signals that result in the acute functional modulation and longer-term transcriptomic and epigenetic regulation of blood vessels. The mechanosensors discussed include ion channels, plasma membrane-associated structures and receptors, and junction proteins. The mechanosignaling pathways presented include the cytoskeleton, integrins, extracellular matrix, and intracellular signaling molecules. These are followed by discussions on mechanical regulation of transcriptome and epigenetics, relevance of mechanotransduction to health and disease, and interactions between VSMCs and ECs. Throughout this review, we offer suggestions for specific topics that require further understanding. In the closing section on conclusions and perspectives, we summarize what is known and point out the need to treat the vasculature as a system, including not only VSMCs and ECs but also the extracellular matrix and other types of cells such as resident macrophages and pericytes, so that we can fully understand the physiology and pathophysiology of the blood vessel as a whole, thus enhancing the comprehension, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of vascular diseases.

CLINICAL HIGHLIGHTS.

-

1)

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases occur preferentially at the branch points and curved regions of the arterial tree because of mechanotransduction events elicited by the oscillatory shear stress associated with disturbed, instead of laminar, flow that acts on the vascular endothelial cells in those regions.

-

2)

Vascular smooth muscle cells respond to pressure-induced distension of the vascular wall, resulting in acute vasoconstriction that, if sustained, progresses to vascular remodeling and hypertension.

-

3)

The vascular endothelium exerts both acute and chronic vasodilatory effects on vascular smooth muscle cells to counteract pressure-induced constriction; loss of this interaction between the two cell layers promotes the progression of hypertension and atherosclerosis.

-

4)

Understanding of the mechanisms of mechanotransduction in vascular endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells and their interactions is essential for the elucidation of the pathophysiological basis of important cardiovascular diseases and the development of effective treatments.

1. INTRODUCTION

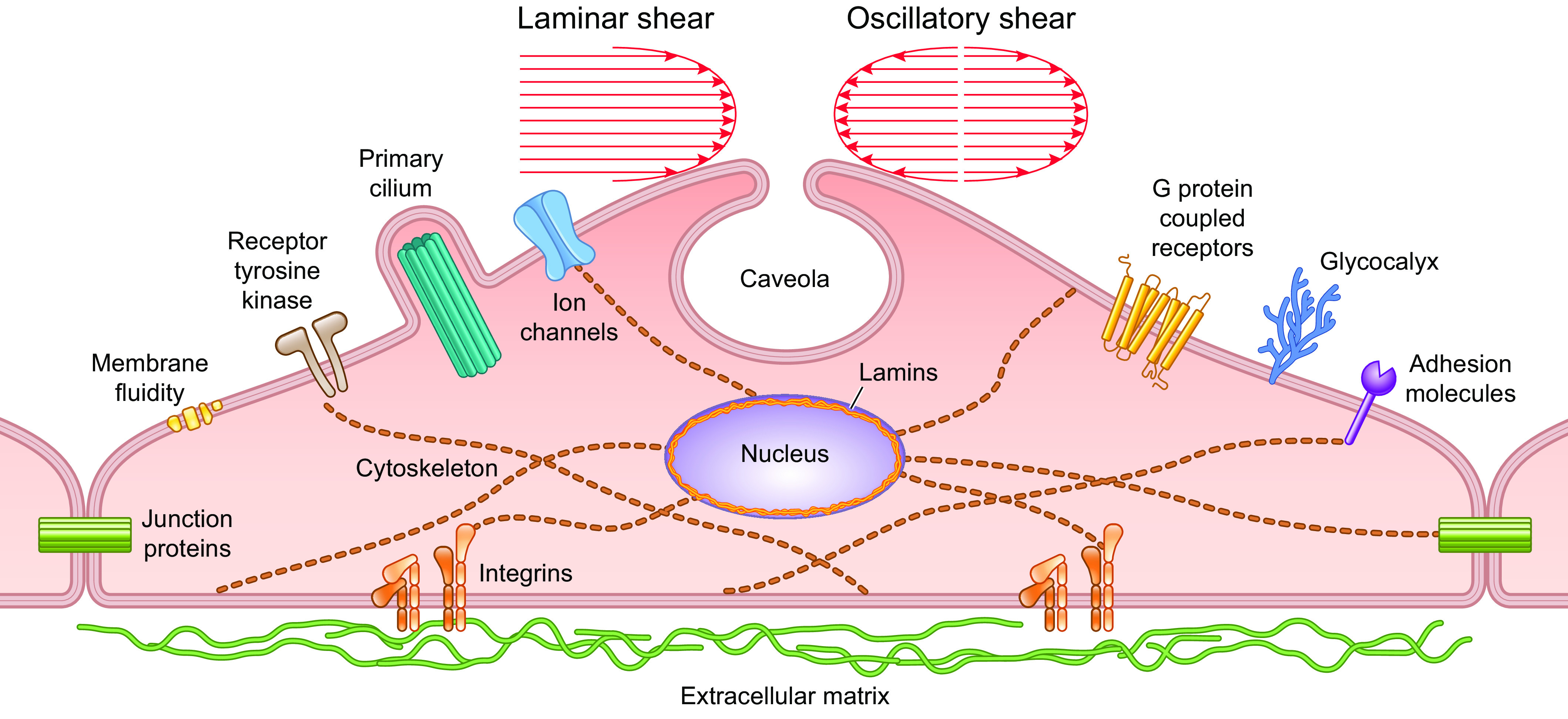

Every cell can detect and respond to changes in its external environment, whether the stimulus involves mechanical, electrical, chemical, magnetic, light, and/or other forms of energy. Although some cells serve as specialized sensors (e.g., cochlear hair cells, photoreceptors), most cells appear to share some basic mechanisms of mechanosensing and downstream signal transduction pathways. Cells in the cardiovascular system are constantly subjected to hemodynamic forces resulting from the pressure generated by the repetitive cardiac contraction and the consequent flow of blood through the systemic and pulmonary circulations. This review addresses the mechanisms of pressure and shear stress detection (i.e., mechanosensing) by vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and endothelial cells (ECs), as well as the subsequent downstream signaling mechanisms (i.e., mechanosignaling) that are activated to produce single-cell or multicell responses. These processes are grouped together under the term “mechanotransduction.” Other cell types in the cardiovascular system also sense and transduce mechanical forces, including cardiomyocytes (1, 2), red blood cells (3, 4), white blood cells (5), platelets (6), and baroreceptor nerve endings (7, 8). This review focuses on the responses of VSMCs and ECs to hemodynamic forces that lead to regulatory or adaptive mechanisms in the circulatory system, including the vascular myogenic response and flow-induced dilation. These processes are complex and involve not only multiple signaling pathways but also multiple temporal components: from rapid events (milliseconds to seconds) such as changes in membrane potential and intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]), to intermediate events (minutes to hours) such as changes in cell alignment, and to long-term events (days to months) such as vascular remodeling or plaque formation.

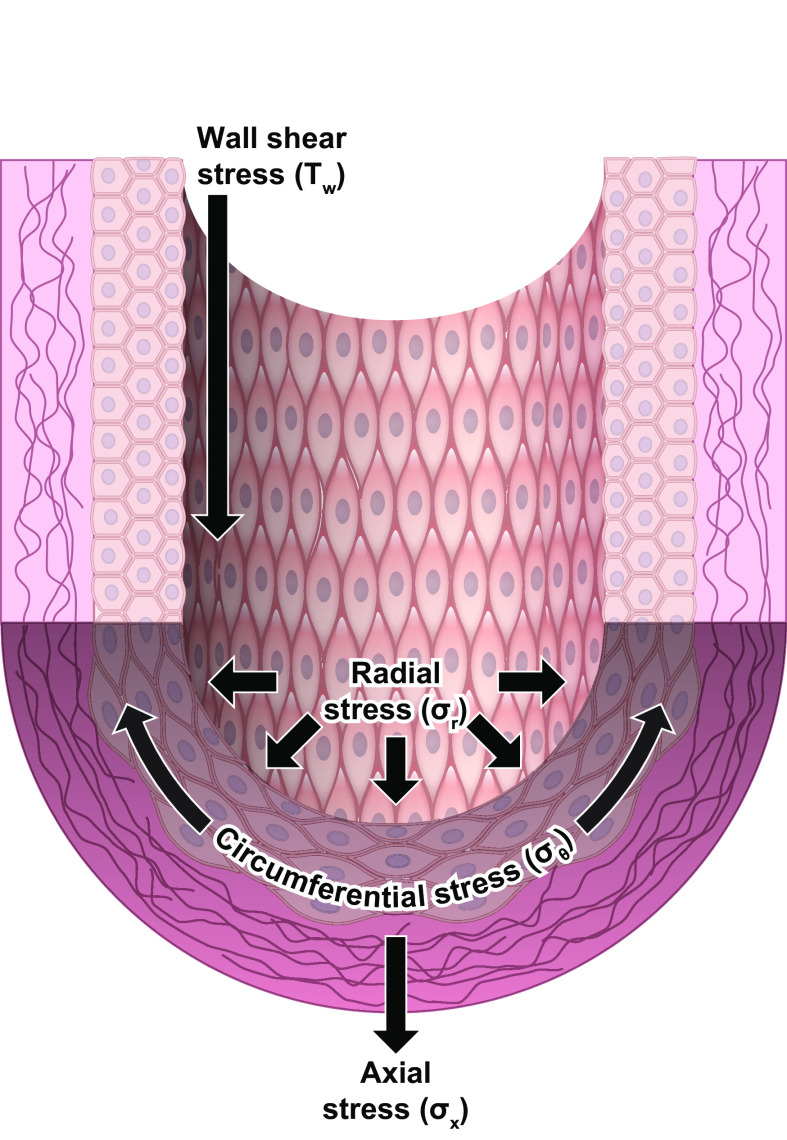

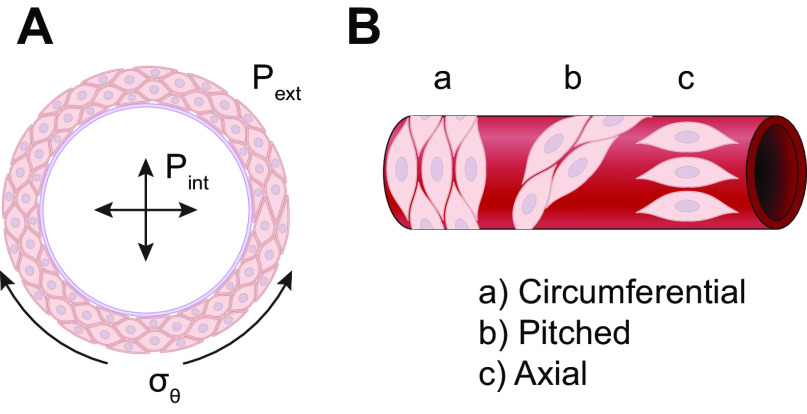

Hemodynamic forces are characterized by different modalities (pressure, shear), different vectors (circumferential, radial, axial; FIGURE 1), both static and dynamic components, and a wide range of magnitudes and temporal characteristics, each of which may vary among blood vessels in different regions of the body. For example, as arterial pressure increases during each cardiac cycle, arteries experience a distending stress. This distending stress acts on the longitudinally oriented ECs in the radial direction of the vessel (σr) and on the circumferentially oriented VSMCs in their longitudinal direction (σθ). The magnitudes of σr and σθ vary within each cardiac cycle, with the prevailing pressure level (e.g., artery vs. vein), within a given vascular bed (e.g., as the pressure profile changes from artery to vein), and across regional circulations (e.g., systemic vs. pulmonary). Additional hydrostatic loads may be imposed, or reduced, by gravitational forces acting on standing columns of blood, especially in bipeds. During each cardiac cycle, ECs directly experience a force resulting from the frictional drag of blood (τw, wall shear stress) on their surface; this effect is greatly attenuated in the medial layer where VSMCs reside, because of the presence of the internal elastic lamina. Wall shear stress varies with the location of an EC within a vascular network (whether it is located in a straight segment, bifurcation, or curvature, in arteries, microvessels, or veins, in a cardiac or venous valve leaflet, or in a valve sinus) and depends on the flow rate, vessel size, and location. The direction and magnitude of shear stress not only change in synchrony with the cardiac cycle but also oscillate at lower frequencies within vascular networks, e.g., in arcading vessels during vasomotion. ECs, which align parallel to the flow stream, have responses to σr and τw (9, 10) different from VSMCs, which are physically separated from the flow stream but aligned perpendicularly to it.

FIGURE 1.

Mechanical forces acting on the arterial wall. Modified from Ref. 9, with permission from the American Physiological Society.

For additional perspectives, the reader is referred to previous reviews addressing the topic of vascular mechanotransduction, some of which focus on vascular smooth muscle (12–16) or endothelium (9, 11, 17), others on selected mechanisms such as shear-stress sensing by EC ion channels (18, 19) or pressure sensing by G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) in VSMCs (20–23), or EC-VSMC interactions (24, 25), as well as other topics that overlap with vascular mechanotransduction, such as vascular transient receptor potential (TRP) channel function (26–28). In addition to reviewing the primary literature, we aim to integrate relevant concepts to provide an updated, comprehensive review that addresses mechanotransduction by vascular smooth muscle and endothelium in health and disease.

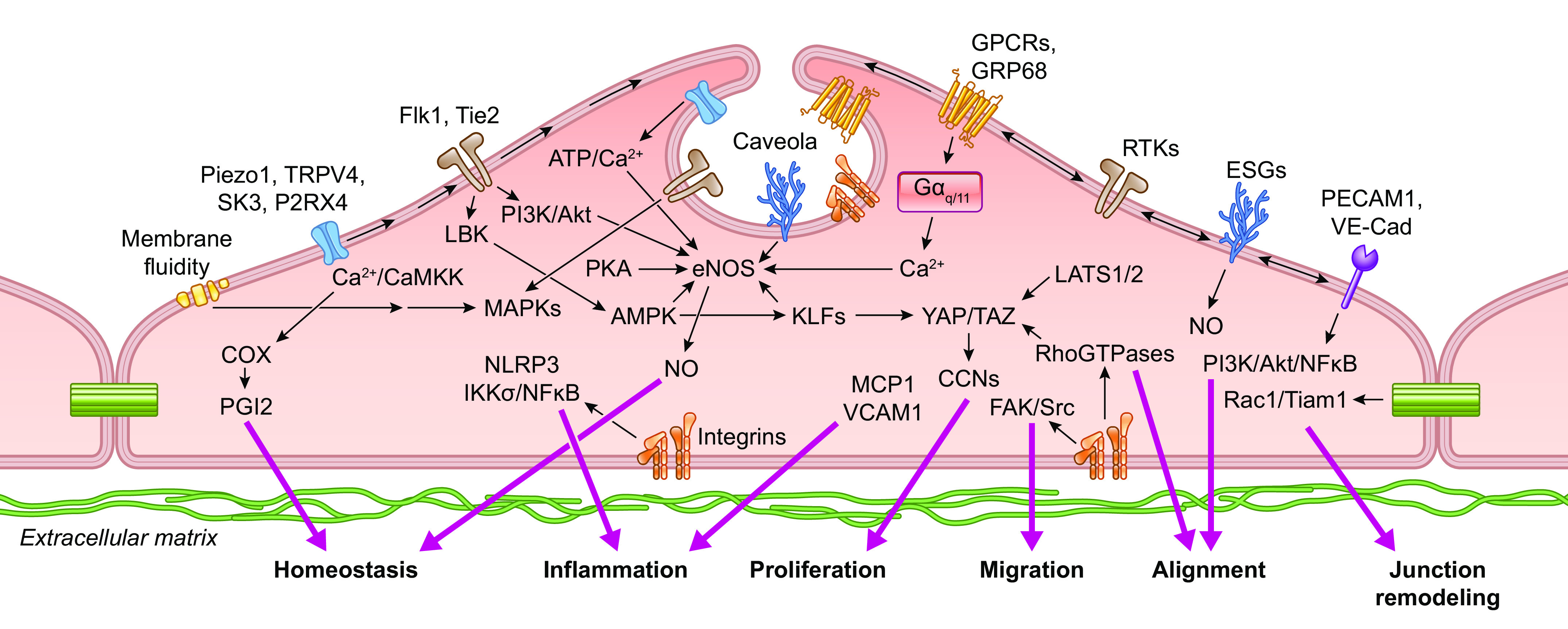

1.1. Mechanoresponses of ECs

1.1.1. Mechanical forces on ECs in the vascular system.

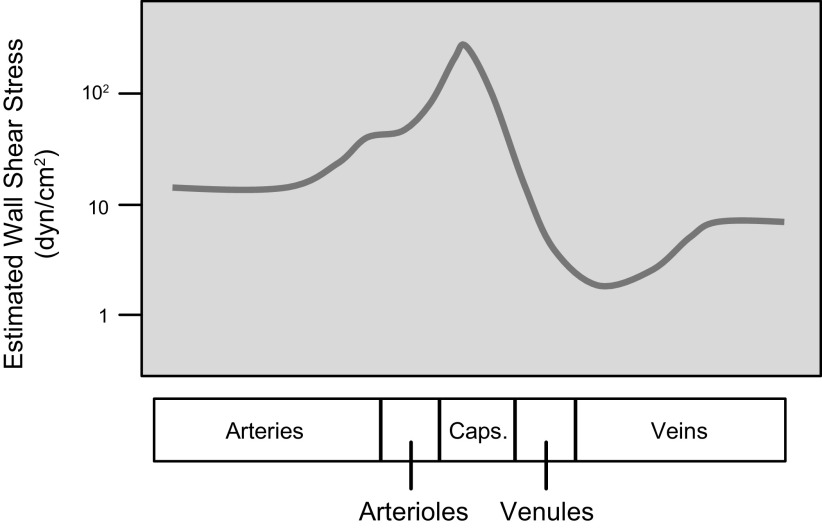

Vascular ECs serve important homeostatic functions in response to chemical and mechanical stimuli (9), including the modulation of vascular remodeling, inflammatory responses, hemostasis/thrombosis, VSMC contraction, and macromolecular permeability. Endothelial dysfunction can lead to pathophysiological changes and vascular disorders (29–31). As indicated above, ECs experience both a radial distending stress (σr) due to transmural pressure and the tangential wall shear stress (τw) due to blood flow (FIGURE 1). Both σr and τw vary with the location of the EC in various segments of the vascular tree because of the different levels of pressure and flow, as well as geometry. τw is a function of (vη/r), where v is mean linear velocity, η is blood viscosity and r is vessel radius. Based on this function, the mean τw in different longitudinal segments of the vascular tree under resting conditions can be estimated as shown in FIGURE 2 (32). Blood is a non-Newtonian fluid, with its viscosity rising at low shear rates (33); however, as a first approximation the Newtonian value of 4 centipoise (cP) is used in this estimation. τw is ∼12 dyn/cm2 in large arteries, but it is >10-fold higher in capillaries, where the high shear stress facilitates the deformation of erythrocytes in traversing the narrow channels. The τw is lowest in postcapillary venules, where the low shear stress is conducive to blood cell aggregation and adhesion. These values apply to systemic vessels in general, but there are regional variations, e.g., in the hepatic and renal circulations, where there are two networks of resistance vessels in series. In the pulmonary circulation, low pressure is accompanied by a low σr, but its greater values of v/r than in the systemic circulation in comparable segments lead to higher τw. Because of the pulsatile nature of the flow dynamics, the values of σr and τw change periodically with each cardiac cycle. ECs respond in both similar and different ways to changes in σr and τw.

FIGURE 2.

Estimated mean wall shear stress (τw, log scale) in different longitudinal segments of the vascular tree under resting condition using the formula 4vη/r, where v is the mean linear velocity, η is blood viscosity, and r is vessel radius. The abscissa scale for the microcirculation [arterioles, capillaries (Caps.), venules] is lengthened in comparison to the large vessels (arteries and veins). From Ref. 32, with permission from Academic Press.

1.1.2. Flow patterns in the arterial tree in relation to the focal nature of atherosclerosis.

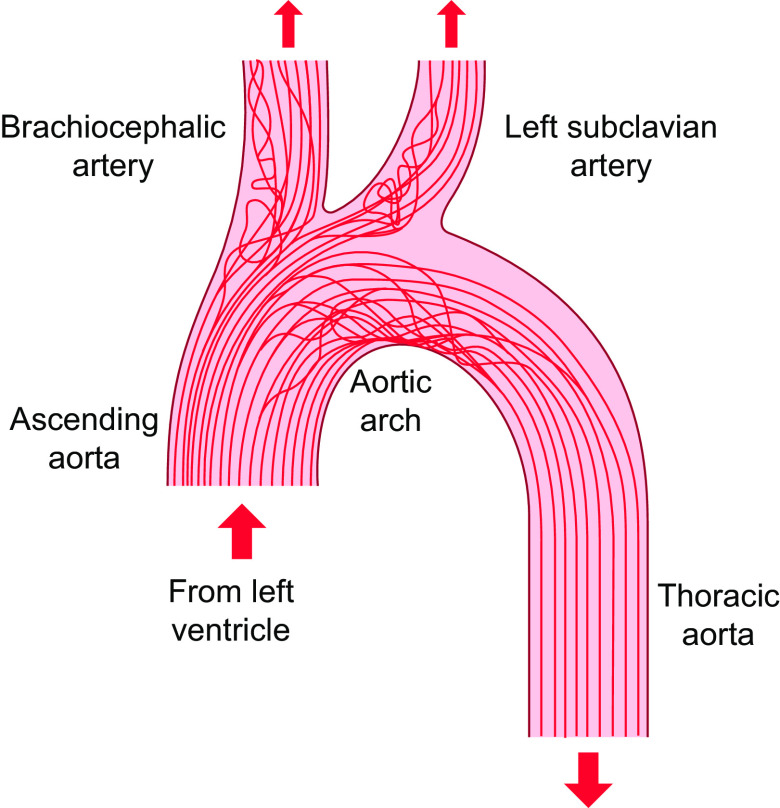

Studies by the Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) Research Group (34) have shown the preferential localization of atherosclerotic lesions at arterial branch points and regions of curvature. The flow patterns exhibit marked variations in the arterial system. The flow in the straight part of the arterial tree (e.g., most of the thoracic aorta) is mainly laminar, whereas the flows at the inner curvature of the aortic arch and arterial branch points are disturbed (FIGURE 3) (35–37). The correlation between the regions of flow disturbance and proneness to atherosclerosis suggests that disturbed flow is an important factor in atherogenesis. The focal nature of atherosclerosis has led to the hypothesis that disturbed flow patterns cause an accelerated EC turnover and an increase in EC permeability to large molecules such as LDL for their entry into the subendothelial layers to cause atherosclerosis (38). Experimental studies on the rabbit aorta (39) have shown that focal regions of disturbed flow (as reflected by nuclear orientation) colocalize with those of increased mitosis and enhanced macromolecular permeability.

FIGURE 3.

Schematic drawing of streamlined antiatherogenic flow (e.g., thoracic aorta) and disturbed atherogenic flow (aortic arch and branch points) in the arterial tree. The figure is based on work from Refs. 35, 36 and adapted from Ref. 37, with permission from the authors.

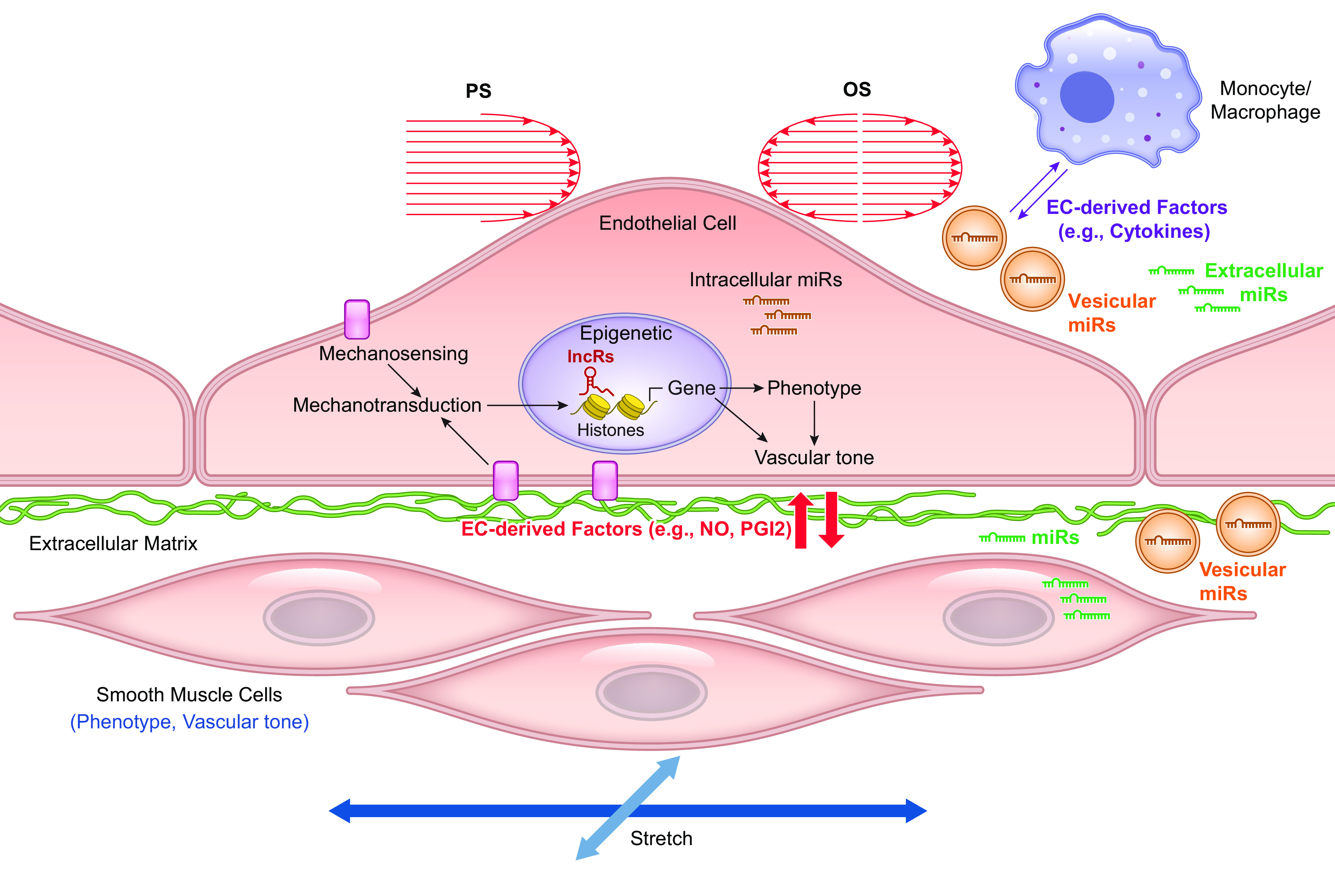

It is well established that, in the straight part of the arterial tree, the pulsatile blood flow is laminar with a clear direction; the pulsatile shear stress (PS) is antiproliferative, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidative, and hence protective against atherogenesis. In contrast, blood flow at branch points and curvatures (e.g., the inner aspect of aortic arch) is disturbed and oscillatory without a clear direction; such oscillatory shear stress (OS) is proproliferative, proinflammatory, and prooxidative, and hence atherogenic. TransWSS is the multidirectional flow with the average magnitude of wall shear stress (WSS) component acting transversely to the mean vector. The simulation of flow patterns based on micro-computer tomography (CT) imaging of rabbit aorta has demonstrated that high transWSS may serve as an important pathogenic factor for lesion formation, in comparison to shear flow without transWSS such as PS (40). The transWSS provides a three-dimensional (3-D) version of the disturbed flow. Although transWSS is different mechanically from OS, they share a lack of forward direction characteristic of PS and laminar shear stress (LS) and have similar biological effects. In vitro experiments have demonstrated that the application of shear or stretch in directions perpendicular to the aligned ECs leads to stress signaling (41, 42), which may contribute to pathogenesis and cell death in the vessel wall. Furthermore, the high temporal gradients of shear stress may also contribute to EC dysfunctions (43, 44). In general, appropriate hemodynamic forces are essential for physiological functions of ECs, whereas their abnormalities, e.g., due to flow disturbance (9, 40, 45–48), in concert with systemic risk factors (49), lead to atherogenesis. The low and oscillatory shear stress in arterial branches and curvatures causes the sustained activation of atherogenic genes. In contrast, the straight parts of the arterial tree exposed to PS with a definite direction are generally spared from atherosclerotic lesions, and ECs in these regions show downregulation of atherogenic genes and upregulation of antioxidant and growth-arrest genes (9). Thus, the disturbed and laminar flow patterns induce differential molecular signaling in ECs to result in the preferential occurrence of atherosclerotic lesions at arterial branches and curvatures and the sparing of the straight parts.

Disturbed flow also occurs on the aortic side of aortic valvular leaflets to contribute to preferential lesion development (50–52). In the venous system, the disturbed flow due to reflux through dysfunctional or incompetent valves, outflow obstruction, or stasis may cause venous hypertension to induce venous EC dysfunction and inflammation, and hence the development and progression of chronic venous diseases (53).

Understanding of the effects of disturbed flow on EC signaling, gene expression, structure, and function will help to define the molecular and mechanical bases for the role of complex flow patterns in the development of vascular pathologies and clinical consequences. Such information may also lead to the discovery of novel disease-related genes and the development of new therapeutic strategies.

1.1.3. Methods to study the effects of shear stress and stretch.

1.1.3.1. DEVICES FOR IN VITRO STUDIES.

The study of mechanosignaling in native vessels is potentially difficult because of the complexity of the in vivo mechanical environment and limitations in cellular, molecular, and genetic investigations, including the difficulties in obtaining sufficient target cells for analyses and implementing molecular manipulations for mechanistic investigations. To understand the detailed mechanisms of regulation of endothelial mechanosignaling and vascular function, in vitro systems have been established with well-controlled applications of shear stress and stretch. Such in vitro experiments using cultured ECs and VSMCs subjected to mechanical stresses in flow devices with precise control of the pulsatility, frequency, amplitude, and duration allow deciphering of the cellular and molecular mechanisms for mechanosensing, signal transduction, transcriptomic and epigenetic regulations, and functional modulations in relation to vascular homeostasis and pathology.

1.1.3.1.1. Flow devices.

Many types of flow devices have been developed to study the effects of the magnitude and pattern of flow on vascular cells, as described in a previous review (9). These devices are used to investigate the responses of ECs to the atheroprotective PS or laminar shear (LS) versus the atheroprone OS and disturbed flow. OS has oscillation without a clear direction, i.e., the net flow is close to zero. PS and LS have clear directions of net flow, with pulsatility present in PS but not LS. In general, the responses of ECs to PS and LS are similar, and the results are often discussed interchangeably in this review, in contrast to OS. Although these devices have been used primarily to study the effects of flow on ECs, they have also been used to study VSMCs.

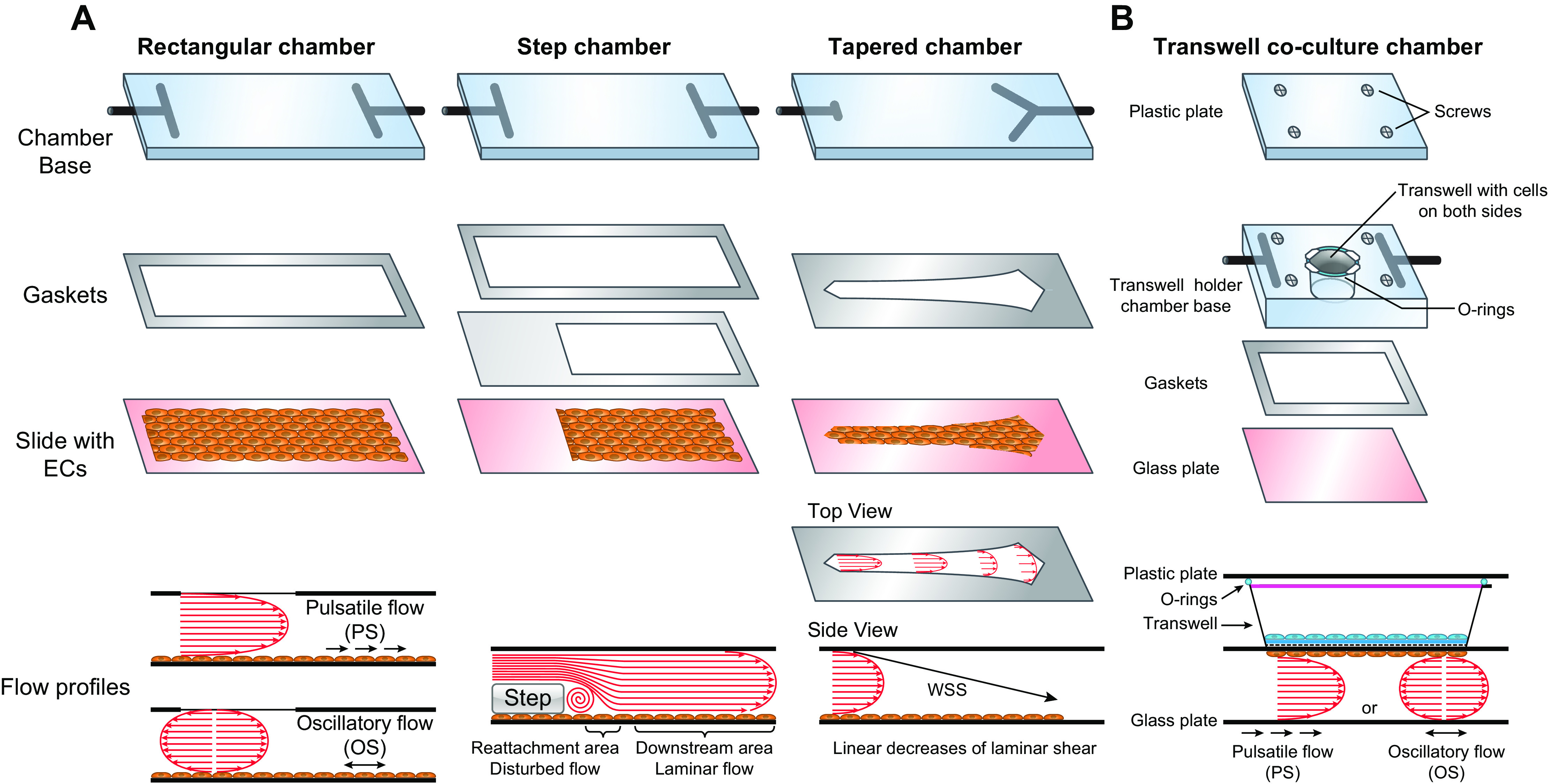

There are mainly two types of flow devices: the parallel-plate flow chamber (FIGURE 4) (54–56) and the cone-plate viscometer (57–59). Both systems have been used to study the effects of laminar shear (60, 61); with modifications, they allow the applications of other flow patterns such as PS and OS. The modification of the parallel-plate flow chamber with a computed continuous increase of the width of the channel over its length (FIGURE 4A, tapered chamber) leads to a linear decrease of the shear stress along the channel length from the entrance, thus allowing the study of cellular responses to different magnitudes of shear stress within the same system (62). The incorporation of a step at the entrance of the flow channel to create a reduction of channel height followed by its step increase can mimic the vessel branch point with the creation of flow disturbance immediately beyond the step, thus allowing the study of cellular responses to PS and OS in a single chamber (FIGURE 4A) (63, 64). In the cone-plate viscometer, different levels of LS, disturbed flow, as well as flows with various waveforms, can be generated with modifications of the cone angle and velocity, placement of surface obstacle strips, as well as addition of computerized controllers (65, 66).

FIGURE 4.

Flow chambers. A: monoculture flow chambers with various geometries for the creation of different flow patterns. B: coculture flow chamber with Transwell for the investigations of cell-cell interactions under different flow patterns. WSS, wall shear stress. See glossary for other abbreviations.

The incorporation of multiple-layered VSMC cultures, or VSMC-embedded ECM gel block with an EC culture on top, into the flow chamber system allows the investigation of the interactions between these two types of vascular cells under controlled flow patterns to reflect the in vivo vascular conditions (67, 68). The porous Transwell has been incorporated into the flow chamber to separate two types of cells (e.g., VSMCs and ECs) to investigate their interactions in responding to flow conditions applied to the EC (FIGURE 4B) (69, 70). This allows the clean separation, visualization, and collection of each cell type, thus enabling the investigation of interactions among different types of vascular cells and providing information reflecting the in vivo vascular conditions.

1.1.3.1.2. Stretch devices.

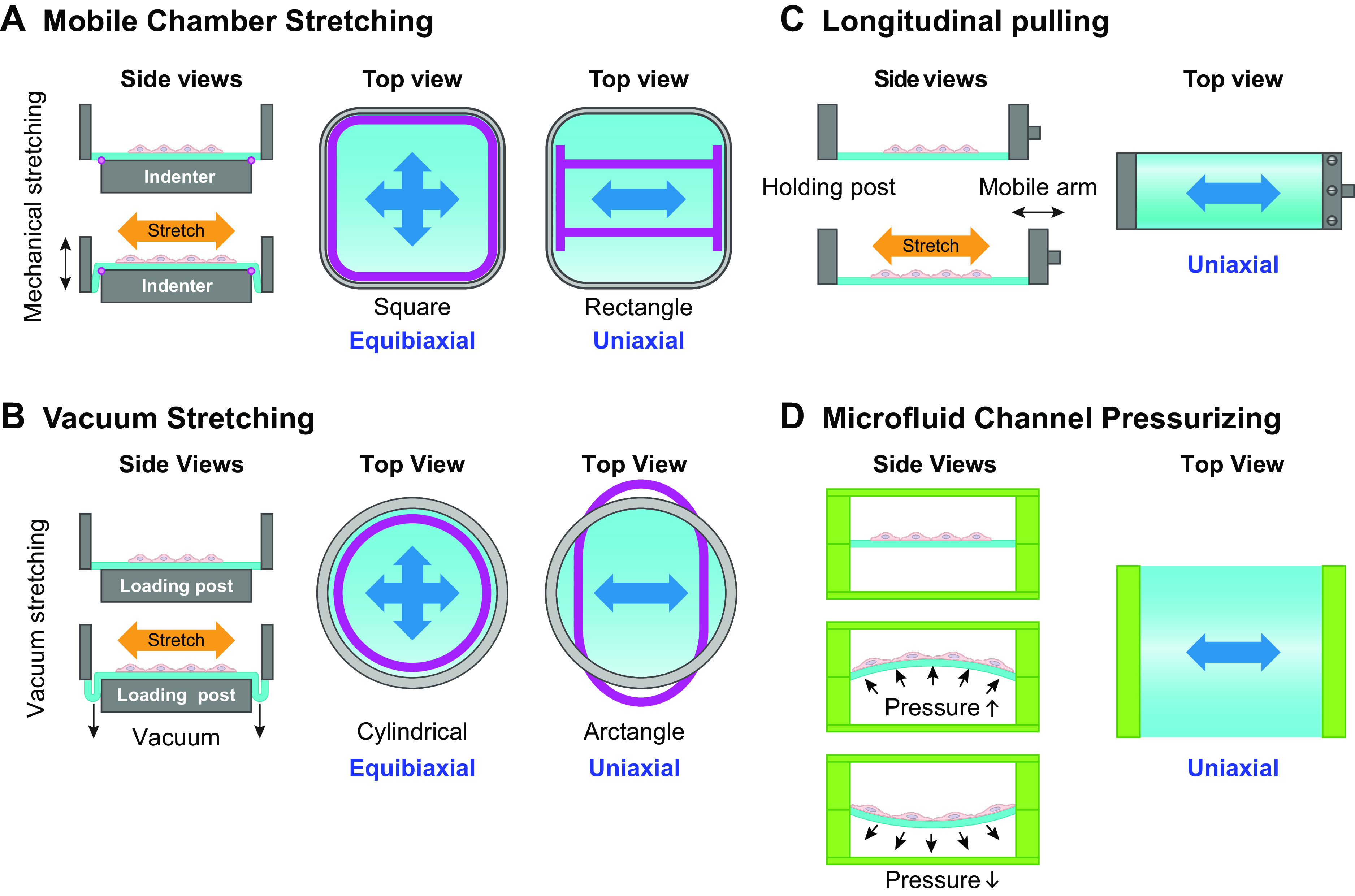

Stretch devices have been employed for mechanosignaling studies on cultured layers of VSMCs and ECs. Here (FIGURE 5) we only outline some examples of stretch devices used in studies on mechanosignaling in cells cultured on an elastic membrane. In general, a chamber with cells seeded on an elastic membrane coated with extracellular matrix is mounted in the device with various stretching mechanisms. In the mobile chamber system (FIGURE 5A), the elastic membrane (blue color) is stretched by pushing the chamber against the indenter. Biaxial stretch is generated by using an indenter with a geometry that matches with the chamber shape to produce even stretching along all sides (FIGURE 5A, left top view, pink lines), whereas uniaxial stretch is generated by using an indenter with a rectangular geometry (FIGURE 5A, right top view, pink lines) for pulling preferentially along the long axis, with only limited pulling along the short axis (FIGURE 5A). A similar principle is applied for the circular chamber using vacuum stretch systems (FIGURE 5B) with different geometries: Biaxial stretch is applied to a circular chamber well by even pulling in all directions against a loading post with cylindrical geometry (FIGURE 5B, left top view, pink lines), whereas uniaxial stretch is generated by using a loading post with an arctangular shape (FIGURE 5B, right top view, pink lines) to apply membrane pulling only along the short axis. The magnitude of stretch is governed by the position of the indenter or the vacuum strength. Another stretch device format is the unidirectional lateral pulling of an elastic membrane mounted on a fixed post at one end and on a mobile arm at the other end. The mobile arm moves cyclically in a lateral direction to generate uniaxial stretch (FIGURE 5C). A microfluid channel system has been constructed with cells seeded onto an elastic polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) membrane on top of the channel that can be deformed by pressure variation underneath in response to microfluid effects (FIGURE 5D). Such a device generates circumferential stress with uniaxial stretch as well as bending stress. All these devices can be used to effectively test the stretch regulation of cell function. However, the induction of stretch by the displacement of an elastic membrane can cause the movement of cell growth medium over the surface of cells in the chamber, and hence some level of undefined shear stress. The effects of shear stresses induced in this manner remain to be determined. Single-VSMC and -EC studies for ion channels mainly involve membrane stretch or compression with micropipettes, bead twisting, or osmotic stimuli during patch-clamp recording or calcium imaging, as discussed in sect. 2.1.2.

FIGURE 5.

Stretch chambers. A: vertical mobile stretch chambers against indenters. B: stretch chambers with vacuum pulling against loading posts. C: longitudinal mobile stretch chamber for uniaxial stretch. D: microfluid channel-based stretch devices.

1.1.4. Shear stress (or flow)-induced vasodilation.

An increase in shear stress in vivo can result from a number of different factors, e.g., as a consequence of arterial pressure elevation or upstream arterial dilation. Increased shear stress triggers multiple intracellular signaling processes in the endothelium, resulting in EC hyperpolarization and/or production of EC-derived metabolites such as nitric oxide (NO) and inhibition of vascular myogenic tone (71). This process, termed shear stress-induced dilation (or more often flow-induced dilation or flow-mediated dilation in human studies), has been extensively investigated in arteries by pressure myography, with which the effects of flow and pressure can be differentiated by keeping the intravascular pressure constant through adjustment of inflow and outflow pressures (72). Flow-induced dilation (or dilatation) often synergizes with other local blood flow control mechanisms, e.g., metabolic hyperemia, to recruit parallel and/or upstream vessels and produce larger network responses (73).

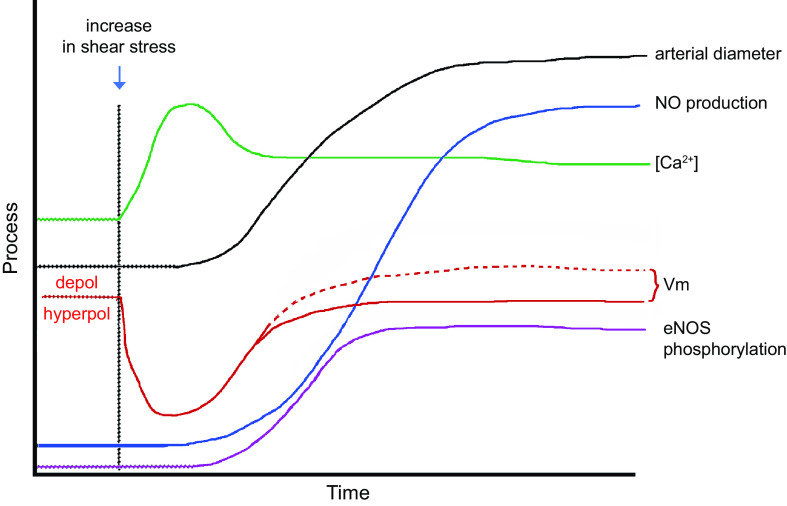

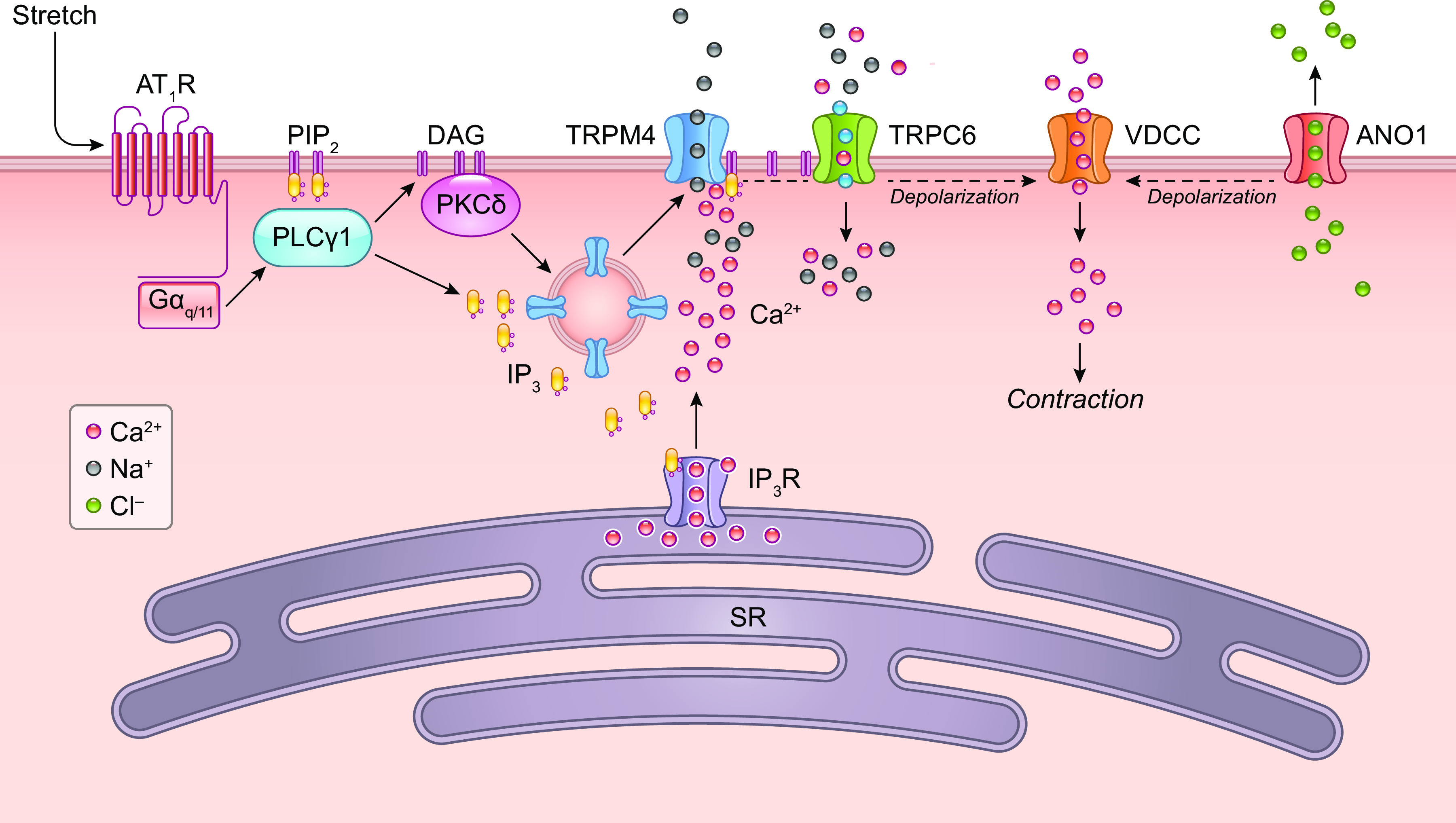

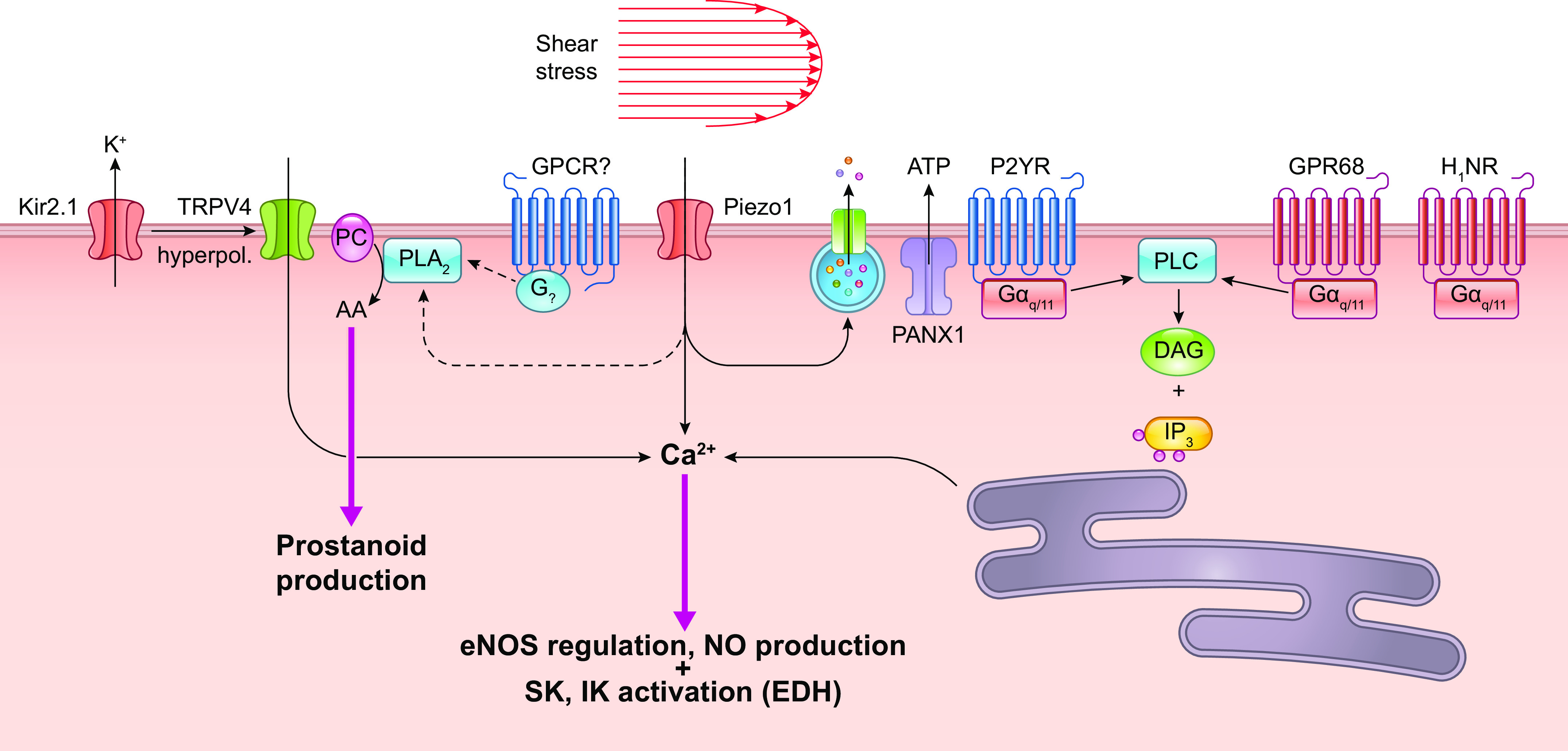

The mechanisms underlying flow-induced dilation and NO production have been studied extensively in intact arteries as well as in cultured ECs (FIGURE 6). Flow-induced dilation can be mediated in part by Ca2+-dependent production of NO and/or prostanoids from the endothelium (74–76), which diffuse to the VSMC layer and inhibit tone (71). After the onset of flow, arterial dilation is reported to have ∼6- to 15-s delay (72, 77, 78), consistent with the activation of intracellular processes that lead to enhancement of endothelial NO production. However, shear stress also induces endothelium-derived hyperpolarization (EDH), which conducts directly to the VSMC layer via myoendothelial gap junctions in most arteries/arterioles such that blocking gap junctions can inhibit flow-induced dilation in some arteries (79). However, the EDH mechanism may be more prevalent under pathological than normal conditions (80).

FIGURE 6.

Hypothesized relative time course of events contributing to flow-induced dilation. Vm: initial hyperpolarization through Kir2 channels followed by secondary depolarization (dotted red line) due to the activation of a Ca2+-activated Cl− channel. [Ca2+]: initial Ca2+ release from endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stores, followed by sustained Ca2+ entry through various Ca2+-permeable ion channels. These events occur in parallel with or are followed by enhanced endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) phosphorylation. All these mechanisms combine to increase arterial diameter through inhibition of myogenic tone. See glossary for other abbreviations.

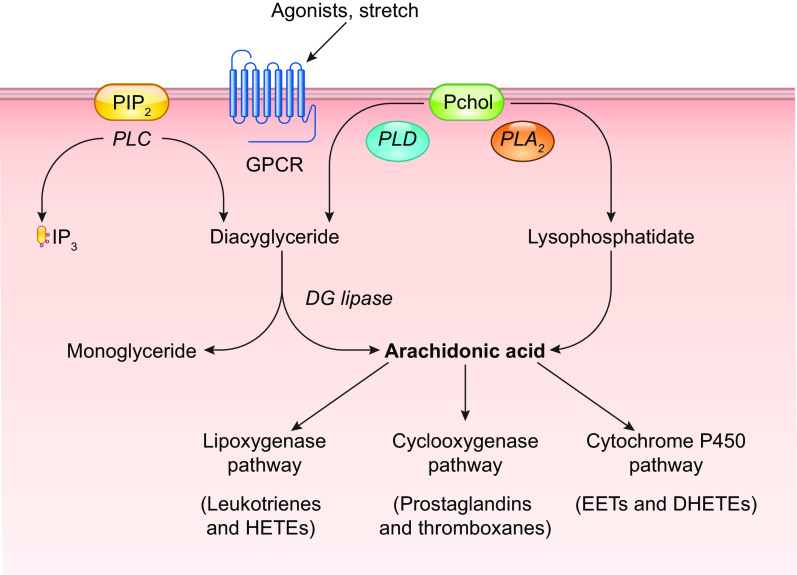

The initial event triggered by increased shear stress is thought to be the activation of one or more K+ conductances, possibly by activation of a mechanosensitive K+ channel, as discussed in sect. 2.1. Hyperpolarization increases the “passive” movement of Ca2+ down its electrochemical gradient into the cytosol (81, 82) of “nonexcitable” ECs, which do not normally express voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) (83–85). The EC isoform of nitric oxide synthase, eNOS, is a Ca2+/calmodulin-regulated enzyme (86–88). A large number of studies have demonstrated that shear stress induces a rise in EC cytosolic Ca2+ levels, both in cultured ECs (for review see Ref. 18) and in intact arteries/arterioles (89, 90). Resting membrane potentials in ECs generally average approximately −30 mV, although a wider range of potentials has been reported in populations of cultured ECs, whose membrane potentials are not as synchronized by gap junction coupling as they are in intact arteries (91). The hyperpolarization triggered by shear stress (as well as by EC-dependent vasodilators) has an upper limit of approximately −90 mV, as determined by the K+ equilibrium potential (EK). Although only an approximate twofold increase in the driving force for Ca2+ entry can potentially occur through this mechanism, shear stress (and most agonists) often induces much greater increases in EC global Ca2+ levels, implying that membrane Ca2+ conductance also changes (92). EC Ca2+ conductance can increase through the opening of non-voltage-gated Ca2+-permeable ion channels, including Piezo1 (93), TRPV4 (94), polycystins (95), and P2X4 (96), as discussed in sect. 2.2. In parallel with EC hyperpolarization, shear stress induces the activation of phospholipase C (PLC), with consequent production of diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol trisphosphate (IP3) (97, 98). IP3 binds to IP3 receptors and induces rapid Ca2+ release from endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stores. Multiple ion channels are potentially activated by these signaling pathways, including transient receptor potential (TRP) cation channels and store-operated Ca2+ entry channels such as Orai (99). The effects of NO are further enhanced through the Ca2+ sensitization of eNOS by phosphorylation at specific COOH-terminal residues (Refs. 100–103; for review see Ref. 104). Prostanoid production may require the activation of additional downstream events (105).

Although one or more ion channels have been hypothesized to be the EC mechanosensor (for review see Ref. 18), other membrane elements may be upstream of ion channels, including receptor tyrosine kinases (102, 106), mechanosensitive GPCRs (107–111), and junctional proteins (112). Each of these mechanisms is discussed in subsequent sections.

1.2. Mechanoresponses of VSMCs

1.2.1. Intravascular pressure exerts a mechanical force on VSMCs.

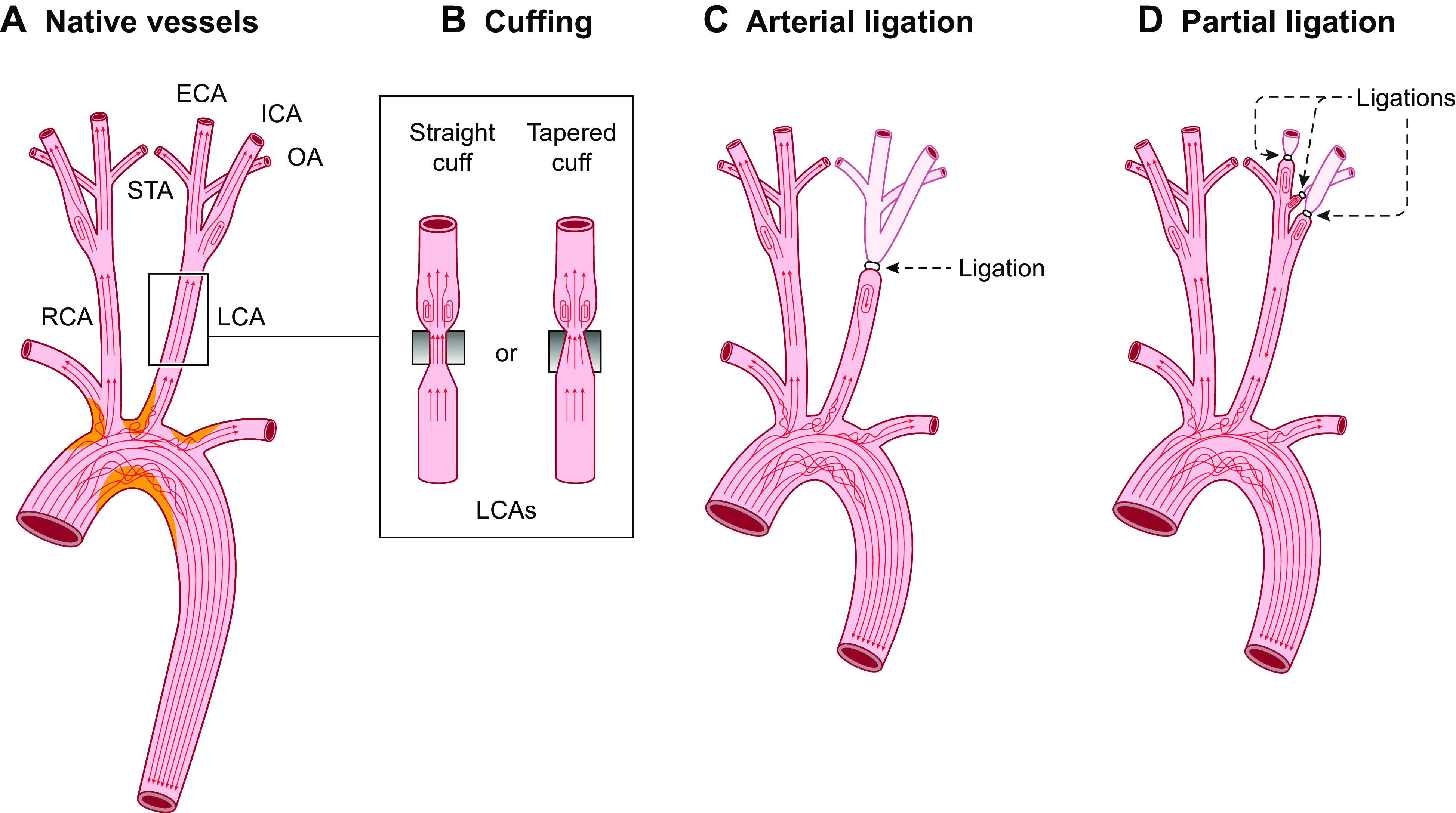

An increase in intraluminal pressure leads to expansion of a blood vessel (FIGURE 7A), subjecting VSMCs to varying degrees of stretch, depending on their orientation (FIGURE 7B). In the medial layers of most arteries, VSMCs are oriented circumferentially so that the primary force, σθ, is distributed along the long axis of the spindle-shaped cell (FIGURE 7Ba). The relationship between σθ and pressure is dictated by the law of Laplace, such that stress σθ = T/h, where T = tension and h = wall thickness. In turn, T = (Pint − Pext)·r, where r denotes vessel radius. Therefore, circumferential stress is determined by the vessel radius and the transmural pressure difference. Because Pext (external or tissue hydrostatic pressure) is usually low and nearly constant in the systemic circulation, a change in Pint (intraluminal pressure) is the most physiologically relevant force that determines the acute change in circumferential stress acting on VSMCs. Arterioles and many small arteries may have a significant fraction of VSMCs oriented with their axis differing significantly from 90° to the flow direction (FIGURE 7Bb; Ref. 113), and some vessels even have axially or helically oriented VSMCs (e.g., the outer layer of some arteries and portal vein; FIGURE 7Bc). The orientation of a VSMC will determine the extent to which σθ is transmitted to the mechanosensing (and force bearing) elements of that cell.

FIGURE 7.

Relationships between transmural pressure, σθ, and VSMC orientation. Cross-sectional (A) and axial (B) views of a blood vessel. See glossary for abbreviations.

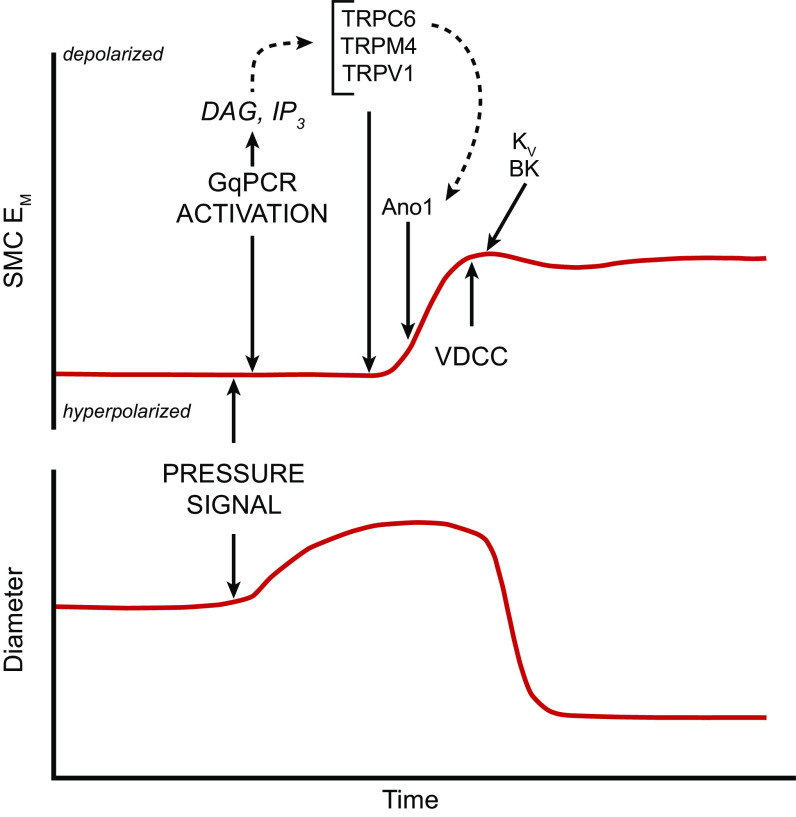

1.2.2. The vascular myogenic response.

1.2.2.1. DEFINITION.

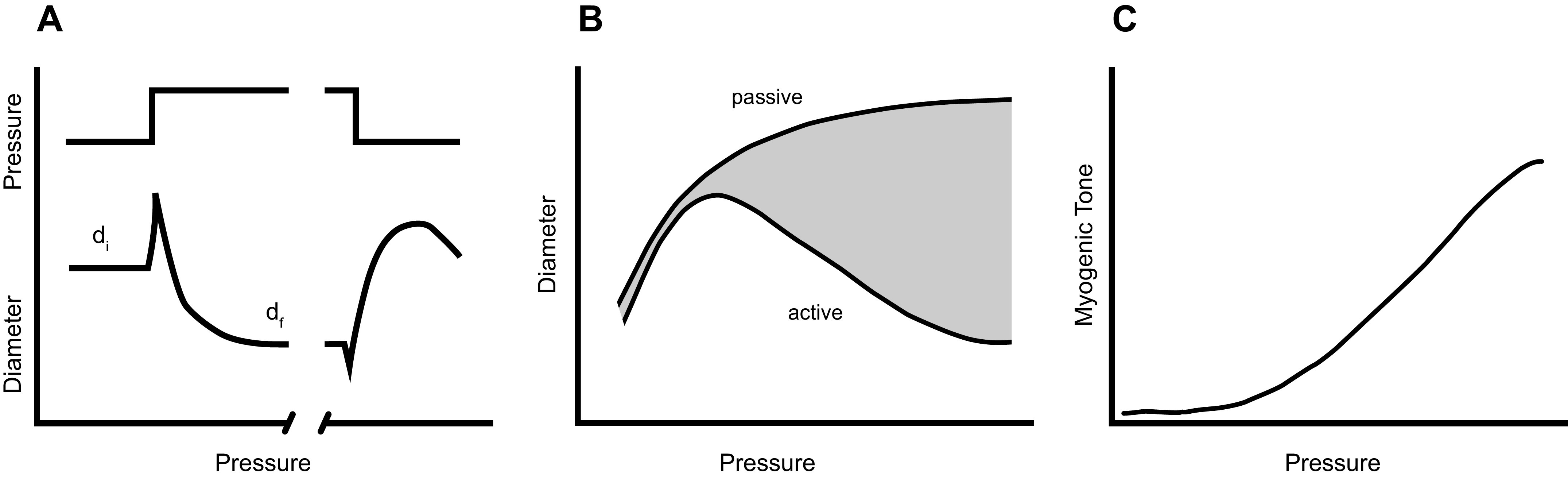

One of the more significant vascular responses to an increase in Pint (hereafter referred to simply as an increase in pressure) is the acute contractile response of VSMCs to circumferential stretch (FIGURE 8A). This phenomenon was initially described by Bayliss (114). When pressure is elevated within a certain range (e.g., in arteries after an increase in systemic arterial pressure or in arterioles as a result of constriction of the terminal arterioles), the vessel transiently distends and then constricts, reaching a final diameter (df) that is smaller than the initial diameter (di), even as pressure remains elevated. The constriction occurs over a time course of fractions of seconds to minutes and reflects active force development by VSMCs within the vessel wall in response to the increase in σθ. The active constriction to pressure elevation is intrinsic to VSMCs and does not require an intact endothelium or innervation (12). Most small arteries and arterioles exhibit this response, and it is detectable in some veins (115, 116) and lymphatic vessels (117). When pressure is lowered, a “myogenically reactive” vessel typically shows the opposite behavior, dilating and remaining dilated even at the new (lower) pressure (FIGURE 8A). The dilation is typically slower and less often studied than the constriction (12), but in the discussions that follow it is assumed that the processes are the same (but see counterargument in Ref. 118). Collectively, the constriction to elevated pressure and the dilation to reduced pressure are referred to as the “myogenic response,” or more properly the “vascular myogenic response.” The magnitude and speed of myogenic constriction, as well as the sensitivity to the initial stretch (determined in part by the relative distensibility of the vessel), may be interrelated and vary widely among different branching orders of arteries/arterioles and between vessels of similar sizes from different vascular beds. Myogenic constrictions occur in most vessels on the arterial side of the systemic circulation and are strongest at the level of small arterioles (119). Arteries/arterioles from the renal and cerebral circulations have the most pronounced myogenic responses (12); e.g., renal afferent arterioles begin to constrict within 300 ms after an initial pressure-induced distension and can completely close within seconds (118). Coronary and skeletal muscle arteries show myogenic constrictions of intermediate magnitude, whereas mesenteric arteries typically have weaker responses (120) and pulmonary arteries often fail to show any constriction (121). The relative gain of the myogenic response in arteries/arterioles of these various vascular beds is proportional to the degree of blood flow autoregulation in those same beds, pointing to one of its presumed physiological roles (discussed below). The activation of the myogenic response is independent of extrinsic factors related to the endothelium, circulating agonists, and components of blood and perivascular nerves, and yet it is modulated by most of these. In vivo assessment of the myogenic response can be complicated by the influences of all these factors.

FIGURE 8.

Various representations of the vascular myogenic response. A: time course of arterial myogenic constriction to a step increase in internal pressure. B: plot of arterial diameter as a function of pressure showing progressive constriction in physiological saline (active) vs. dilation in calcium-free physiological saline (passive). C: myogenic tone (passive-active) curves in B plotted as a function of pressure.

1.2.2.2. METHODS FOR STUDYING THE MYOGENIC RESPONSE.

Multiple methods have classically been used to study the myogenic response. Whole organ studies originally suggested that both metabolic and myogenic components contributed to the calculated vascular resistance changes evoked by manipulation of perfusion pressure and/or venous pressure (122, 123). Clever modifications to these whole organ methods were employed in attempts to understand the underlying segmental resistance changes (124, 125). Multiple laboratories extended this line of investigation to studies of the microcirculation using intravital microscopy, where the diameters of individual small arteries and arterioles could be observed while manipulating pressure (126–131). These studies have been summarized in review articles and chapters (132, 133). However, even with the use of these methods, the pressure change at the level of a particular vessel was usually unknown and could not be precisely controlled. Investigations of mechanisms underlying the myogenic response were not advanced until the development of methods to study single small arteries or arterioles under controlled conditions, either under isometric conditions with a wire myograph (134, 135) or under isobaric conditions with “pressure myography” (136, 137). In wire myograph experiments, myogenic tone development is represented by the secondary development of force after an initial stretch (138–141); however, myogenic responses under these conditions are highly variable and labile (115, 141). Myogenic responses are now most often studied with pressure myography of cannulated arteries/arterioles, where it is possible to control Pint and/or Pext in the absence of flow, exchange luminal and extraluminal solutions, and regulate temperature while accurately measuring internal diameter. An additional advantage of pressure myography is that the VSMC layer is maintained in its normal geometry (135, 142). The experimentally measured variable is usually the time course of constriction/dilation, and the data are analyzed and presented in comparison to the responses of the same vessels to equivalent pressure steps after elimination of all active tone in calcium-free solution. The active and passive steady-state diameters are plotted against pressure (FIGURE 8B), with the difference between the two curves representing the myogenic responsiveness of the vessel (shaded area in FIGURE 8B). Active myogenic tone developed at every measured pressure is often described by the relationship shown in FIGURE 8C.

1.2.2.3. PHYSIOLOGICAL ROLE OF THE MYOGENIC RESPONSE.

The myogenic response is proposed to subserve several physiological roles, including 1) the autoregulation of blood flow (the ability of a vascular network to maintain flow at different levels of perfusion pressure); 2) the establishment of a basal level of vascular tone on which vasodilators and vasoconstrictors can bidirectionally regulate flow; 3) the partial regulation of capillary hydrostatic pressure (Pc) if perfusion pressure to an organ falls; 4) protection against excessive increases in Pc and subsequent net fluid movement from capillaries during various conditions associated with elevated vascular pressure, including venous occlusion, increased gravitational hydrostatic loads, and systemic hypertension; and 5) contribution to the initial phase of reactive hyperemia (the transient increase in blood flow to an organ that occurs after a period of ischemia) (143). Metabolic, neural, and shear stress control mechanisms of blood flow can attenuate or potentiate the vascular myogenic response (71, 144). The physiological relevance of the myogenic response is the focus of detailed discussions in previous reviews (71, 143, 145, 146).

1.2.2.4. CONCEPTUALIZING THE UNDERLYING MYOGENIC MECHANISM.

Conceptual arguments for how the myogenic response might be initiated and sustained were advanced by Johnson in his Handbook of Physiology chapter (146). These and earlier discussions (147–149) served as initial attempts to elucidate the underlying mechanisms. Johnson asked how a system with vessel radius as the sensed variable could explain myogenic constriction to a radius lower than control in response to sustained, elevated pressure, because the error signal would have been eliminated once the radius reaches its initial level. Indeed, elimination of the error signal is a long-standing question addressed by subsequent reviews on mechanotransduction in general (150–153). Johnson, and Burton before him (149, 154, 155), proposed that if wall tension, rather than radius, were a sensed variable, tension would increase in response to pressure elevation and return toward, but not completely back to, or below, control as the vessel constricted. In this way, an error signal for regulating wall tension would persist after steady-state constriction of the vessel to a smaller radius. The concept of myogenic control of arteriolar diameter through regulation of wall tension, although not proven, is generally consistent with experimental data (131, 156–158), even though the supporting data are only correlative in nature. Similar, widely accepted arguments have been advanced in favor of acute regulation of wall shear stress (78, 159) and long-term regulation of wall tension during vascular remodeling (160, 161). Although these are useful for discussing homeostasis, additional insights are needed into the underlying cellular mechanisms.

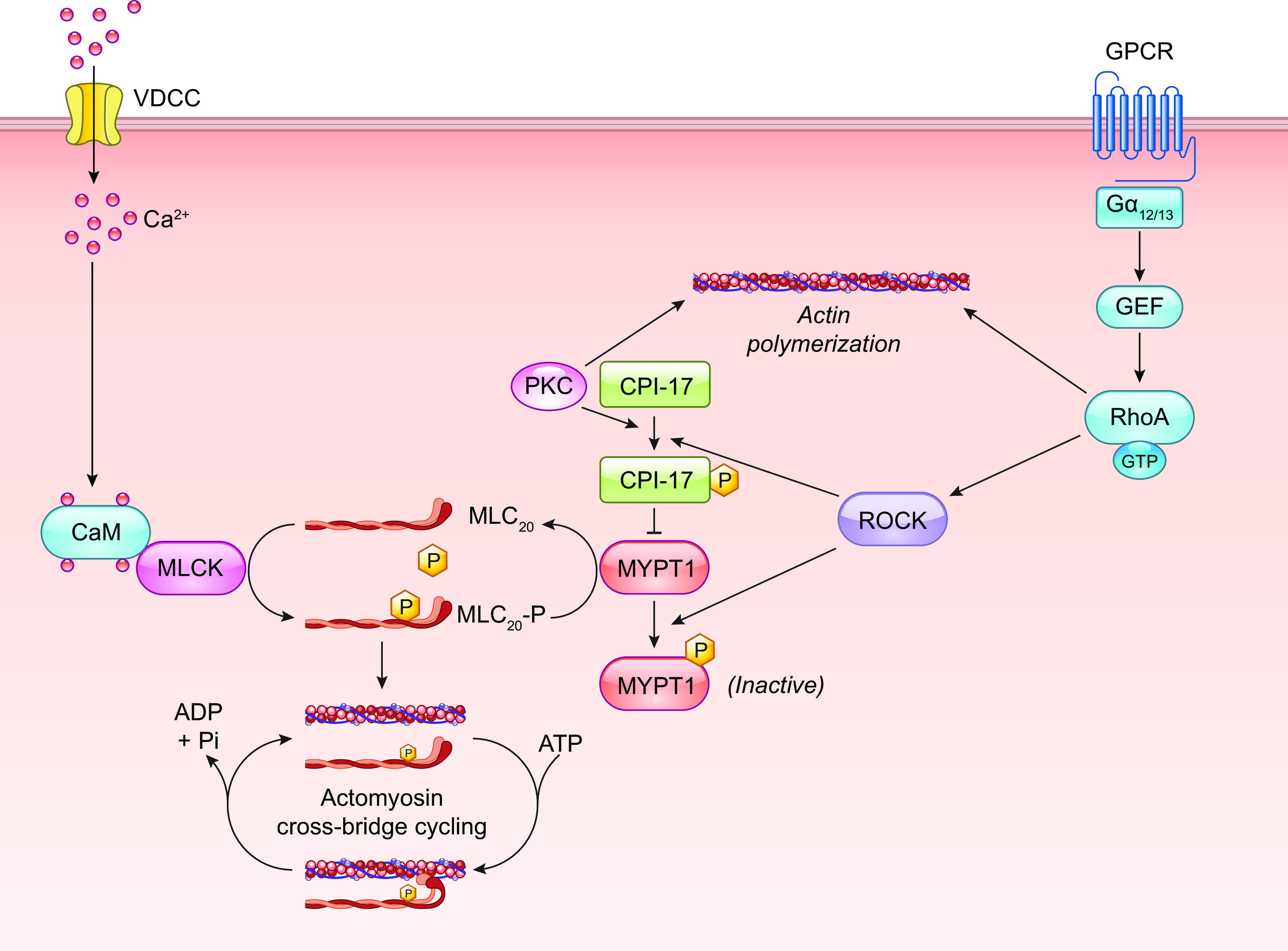

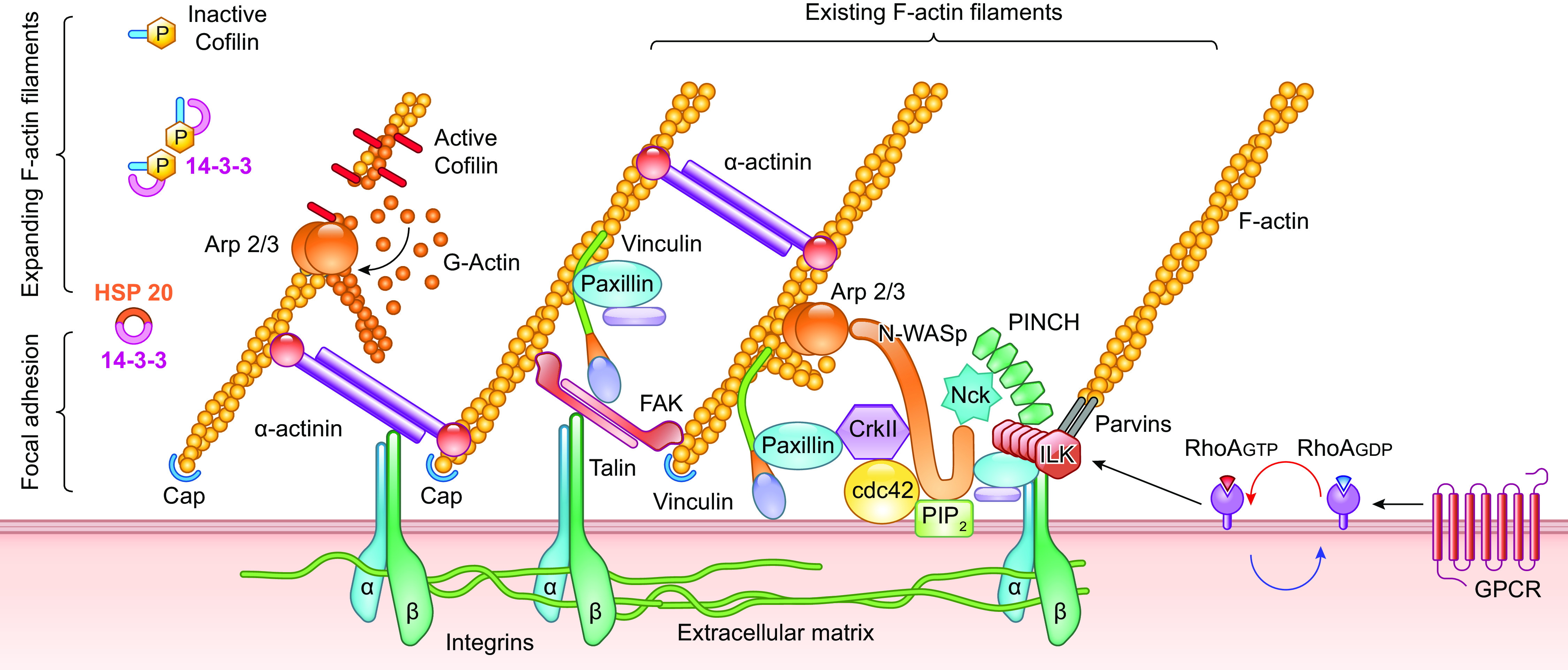

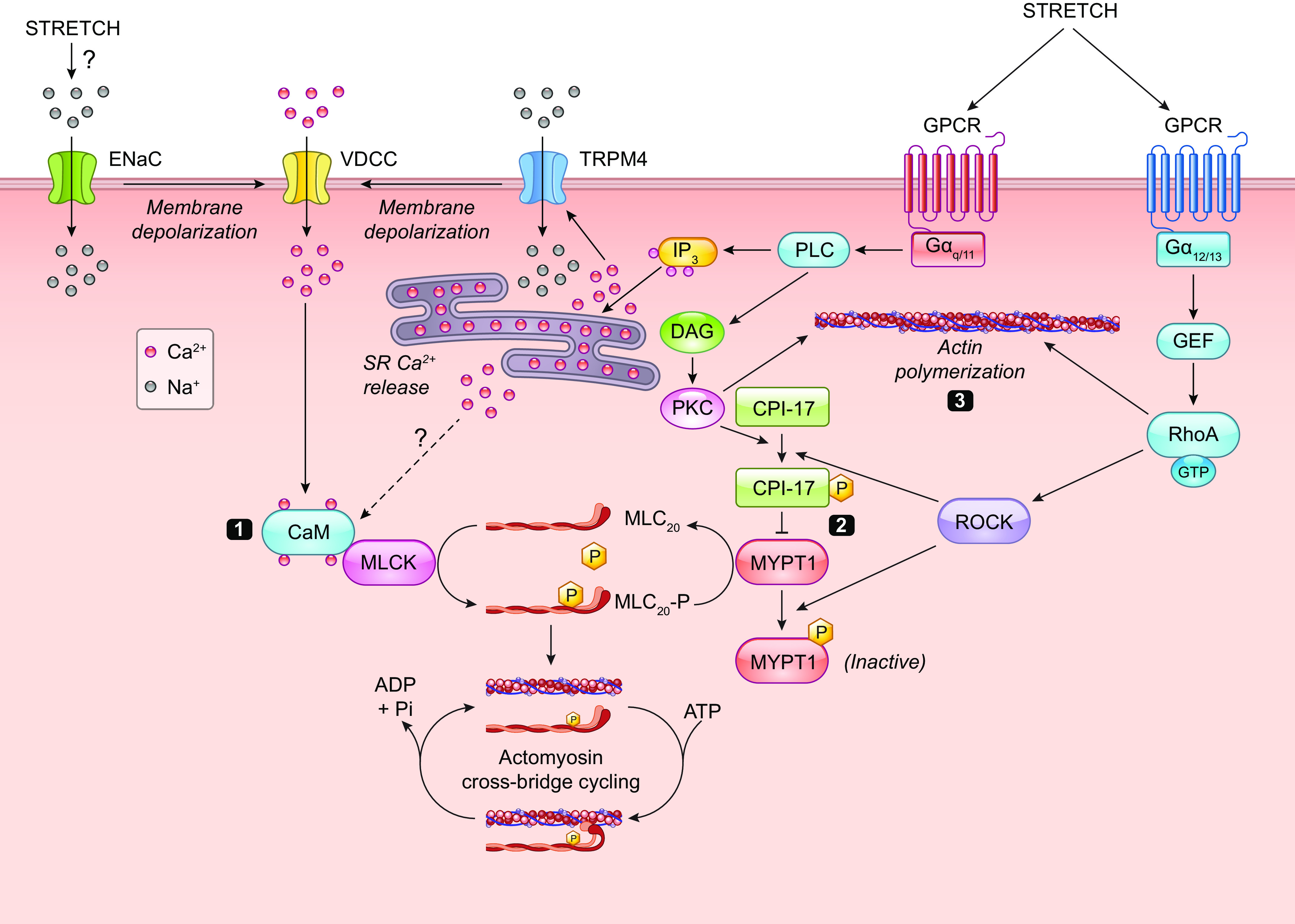

Myogenic constriction is thought to involve stretch activation of one or more VSMC mechanosensors, followed by activation of downstream signaling pathways that results in phosphorylation of a critical myosin light chain serine residue (MLC20) (162–164), leading to increased cross-bridge cycling and actomyosin force development. Multiple signaling pathways in addition to the myogenic response regulate MLC20 phosphorylation via activation of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) and/or inhibition of myosin light chain phosphatase (MLCP) (165, 166). It is often assumed that the mechanism underlying vascular myogenic constriction is common to all types of arterial vessels, but a few studies in which similar pathways were blocked in arteries from different tissues suggest possible differences in the underlying mechanism(s) (167). Force-sensing elements are considered to be the most upstream components of the myogenic response signaling pathway, whereas phosphorylation of MLC20 is considered the most downstream component. Potential force-sensing elements include ion channels, integrins, focal adhesion complexes, cell junction molecules, cytoskeletal complexes, caveolae, and G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). The sections below discuss the evidence for and against these mechanisms.

1.2.2.5. PRESSURE-INDUCED DEPOLARIZATION PRECEDES MYOGENIC CONSTRICTION AND IMPLIES THE INVOLVEMENT OF ION CHANNELS.

A hallmark of the arterial response to pressure elevation is rapid VSMC depolarization (168), which triggers a global VSMC calcium increase (169, 170) through activation of voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) (12). Ca2+ influx down its electrochemical gradient through VGCCs produces a global rise in cytosolic [Ca2+], leading to the activation of MLCK, MLC20 phosphorylation, and vasoconstriction (162, 171). It is well documented that myogenic tone- and pressure-induced constriction are suppressed by L-type Ca2+ channel (Cav1.2) inhibitors (12). Additionally, smooth muscle (SM)-specific deletion of Cav1.2 eliminates the arterial constriction to pressure elevation and lowers peripheral resistance and blood pressure (172), which are effects that would be predicted with the widespread loss of arterial myogenic tone. This Ca2+-sensitive pathway has been the most widely studied mechanism underlying the arterial myogenic response and is the primary reason for extensive discussions of mechanosensitive VSMC ionic mechanisms in sect. 2. However, two additional pressure-sensitive pathways regulate myogenic tone through MLCP and actin polymerization; these are discussed in sects. 5.1 and 5.2, respectively.

Pressure-induced vascular smooth muscle (VSM) depolarization appears to be the key initiating event in the vascular myogenic response. The membrane potential (Vm) of VSMCs is highly pressure dependent, with resting values ranging from approximately −60 mV at 10 mmHg to approximately −30 mV at 160 mmHg (168, 170, 173) (see Figures 1 and 8 in Ref. 173 for data from cerebral and skeletal muscle arteries, respectively). Data are typically compiled from steady-state Vm measurements made at multiple pressures after repeated impalements because measuring the time course of depolarization in a single VSMC before, during, and after a given pressure step usually is precluded by vessel wall movement that can easily dislodge a sharp microelectrode. It has not been possible to selectively prevent pressure-induced VSM depolarization to test whether constriction is blocked by such a maneuver (174). Elevating bath K+ concentration ([K+]) above 15 mM leads to VSMC depolarization and generally results in a blunting of myogenic responsiveness (175), i.e., reducing the slope of the curve in FIGURE 8C, but this intervention directly and indirectly affects the activity of multiple ion channels. Certain agonists also blunt myogenic responsiveness (176, 177), presumably with little or no VSM depolarization (178, 179). The similarity of the KCl and agonist effects suggests that wall stiffening per se may explain the decreased myogenic responsiveness under these conditions, although the possibility of attenuation of the initiating “error signal” cannot be ruled out.

The well-supported observation of pressure-induced depolarization naturally suggests a role for a mechanosensitive ion channel that would permit cation entry or anion efflux, but another possibility would be pressure-induced inhibition of a constitutively active K+ current (180). Initial studies on the ion currents activated by stretch in isolated single smooth muscle cells (SMCs) pointed to a nonselective cation channel with a relative ionic permeability Na+, Ca2+ > K+ ≫ Cl− and a conductance of ∼30 pS (181–185) that could produce depolarization when activated. Although these data were obtained before the molecular identification of TRP and Piezo channels, the measurements are consistent with the ionic permeabilities of several TRP family members, including TRPC6, TRPC3, TRPC7, and TRPM4, and other cation channels such as Piezo1 and ENaC. Subsequent functional studies on arteries have provided evidence for a component of myogenic constriction mediated by ENaC and ASIC channels or specific TRP isoforms. Evidence for these and other ion channels is discussed in sect. 2.2.

2. MECHANOSENSITIVE ION CHANNELS

Before providing detailed analyses of specific channels involved in shear stress-induced EC responses and pressure-induced VSMC responses, we first address general concepts about mechanosensitive channels because the experimental conditions under which mechanosensitivity is determined and the forces required for gating, particularly in biophysical protocols, have important implications for the physiological relevance of a given ion channel.

2.1. Background

2.1.1. General concepts.

What determines whether an ion channel functions as a legitimate, physiological mechanosensor? Many ion channels are polymodal, i.e., they can be gated by different types of stimuli, including electrical, chemical, and mechanical forces. A given channel may have a primary gating modality, but it may also respond to a lesser degree to other stimuli. Examples include channels such as TRPV1 that are sensitive to temperature, plant-derived chemical compounds, pH, and changes in osmolarity (186, 187) and Kv channels that exhibit both voltage sensitivity and mechanosensitivity (188, 189). Even photoreceptors have been found to require a mechanical component to gating under certain conditions (190). Posttranslational modification (phosphorylation, methylation, palmitoylation, etc.) of critical channel residues could potentially lead to switching between primary and secondary gating modalities. Because multiple ion channels have been implicated in VSMC and EC mechanosensitivity, polymodal gating is an important concept to clarify. Thus, although multiple ion channels can potentially be activated by circumferential stretch or shear stress under in vitro conditions, their primary sensitivity may be to nonmechanical factors and thus their contributions to pressure-induced myogenic constriction or flow-induced dilation might be minimal or undetectable in vivo.

2.1.2. Experimental methods for determining single-cell mechanosensitivity and their limitations.

Ion channel mechanosensitivity most often is assessed with patch-clamp electrophysiology methods. Patch clamping is a single-cell voltage-clamp method that enables ionic current contributed by a specific type of ion channel to be measured. For stability, the most commonly used recording mode is the cell-attached recording mode, in which the outside of the cell membrane is exposed to the solution in the patch pipette and the inside of the membrane to the normal cytoplasmic contents; an alternative method is the excised, inside-out recording mode, in which the patch is pulled off after gigaseal formation and the inside surface is exposed to the bath solution. Some studies employ the conventional whole cell recording mode, in which the patch is purposely ruptured and the cell is dialyzed with the pipette solution. Other studies use the perforated-patch recording mode, in which the membrane patch is not ruptured but exposed to a permeabilizing compound added to the patch pipette solution that makes the patch permeable to monovalent cations (and to a lesser extent anions) but not calcium (see details in Ref. 191); this method allows intracellular Ca2+ levels to remain undisturbed during the recording. The other method commonly used in studies of mechanosensitive ion channels involves the insertion of recombinant channels into a lipid bilayer (192). The experiments are performed in a chamber with cis- and trans-compartments connected through a small aperture. After a lipid solution is applied to the aperture, a planar bilayer membrane forms in the hole. Recombinant ion channels can then be inserted into the membrane from a micellar solution or after fusion with liposomes. The ion current associated with channel gating is recorded from the two sides of the chamber. Many electrophysiology studies have been made with recombinant channels to isolate the behavior of a specific ion channel, because studies performed in native cells can be complicated by lower channel density and the presence of multiple mechanosensitive currents.

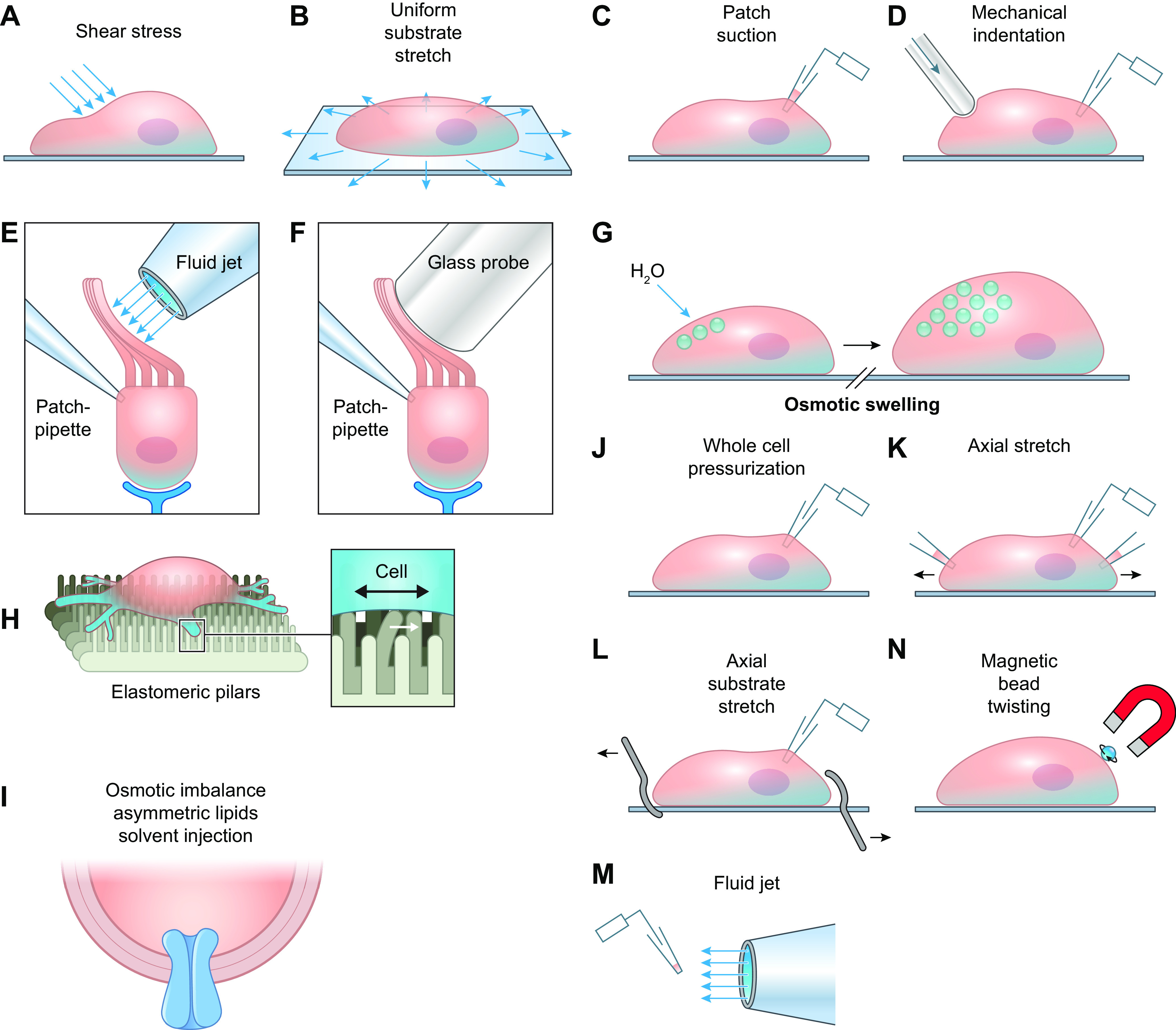

Conclusions about whether a particular ion channel is mechanosensitive may depend critically on how a mechanical stimulus is applied in an experimental protocol (193, 194). In bilayer studies of recombinant channels, asymmetric lipids are often used to create a hydrophobic mismatch and thereby increase the membrane curvature and tension (see examples below). In experiments with native cells, the types of mechanical stimuli vary widely (FIGURE 9). The approach used most commonly to assess mechanosensitivity of selected ion currents is to apply pressure or suction through a patch-clamp micropipette in the cell-attached or excised patch recording mode. Negative and positive pipette pressure may be equally effective in elevating membrane tension in cell-attached patches (196). Mechanical perturbation of whole cells has been accomplished in multiple ways, including indentation with blunt probes, substrate deformation, and the use of micropipettes or matrix-coated beads to pull on, or twist, the cell membrane (FIGURE 9). However, in some cases, macroscopic currents cannot be evoked by these means even if single-channel mechanosensitive currents are elicited in the same cells (197), raising the issue of possible artifacts arising from glass-lipid interactions in the latter recording mode (189, 198). Stretch activation of some channels becomes easier with repeated testing; this also raises concerns of artifacts (199) due to changes in the structural integrity of the patch (200) or the cortical actin cytoskeleton (CSK) (201). Both ECs and VSMCs have been subjected to LS or OS, acutely or chronically, by flow streams directed from micropipettes or small tubes or by controlling flow in open or closed chambers (FIGURE 4). Osmotic swelling is a widely used mechanical stimulus that requires only a solution change, but swelling can trigger chemical as well as mechanical responses because it dilutes cytoplasmic contents, decreases ionic strength (which in itself alters ion channel conductance), elicits production of metabolites such as arachidonic acid (202), and alters the cytoskeletal composition (200). For these reasons the response of an ion channel to an osmotic stimulus alone is generally not considered to be conclusive evidence of mechanosensitivity (195).

FIGURE 9.

Commonly used mechanotransduction assays for ion channels. A: application of shear stress to a single cell. B: stretch of a cell by substrate deformation. C: deformation of local membrane by patch pipette suction while recording single-channel currents. D: focal indentation of cell with mechanical probe while recording whole-cell current. E: deformation of cell (in this case inner ear hair cell) using fluid jet from micropipette while recording whole-cell current. F: deformation of inner ear hair cell with blunt probe while recording whole-cell current. G: osmotic swelling of cell. H: deformation of cell seeded onto elastomeric pillars. I: deformation of channel incorporated into bilayer by injection of asymmetric lipids. J: pressurization of a single cell through a whole-cell recording pipette. K: stretch of a single cell using two patch pipettes while recording whole-cell current. L: stretch of a single cell on flexible substrate using two blunt pipettes while recording whole-cell current. M: recording of current from patch of an excised, inside-out cell membrane while moving it into a flow stream from a pipette. N: localized deformation of a cell membrane by twisting of a magnetic bead attached to the cell surface. Modified from Ref. 195, with permission from Neuron.

Many studies addressing the mechanosensitivity of ion channels employ supraphysiological forces, such as unusually large osmotic gradients (e.g., 500 mM mannitol) (203) or extreme membrane distortion generated by lipid-glass interactions in cell-attached patches (188, 189, 194, 198, 204). Cell dialysis with certain solutions, including KCl and KBr, can dissolve certain cytoskeletal components (205). Mechanosensitive studies of reconstituted channels suffer from additional problems, as discussed elsewhere (206, 207). It is therefore important to consider whether the mode or magnitude of the mechanical stimulus required to activate a channel in a bilayer, isolated cell, or membrane patch is consistent with the physiologically relevant force the channel would experience in vivo.

2.1.3. Criteria for true mechanosensitivity.

Chalfie and coworkers and Patapoutian et al. propose that a bona fide mechanosensitive ion channel should fulfill strict criteria to ensure that it is a direct, rather than indirect, mechanosensor (203, 208). The proposed criteria include the following:

-

1)

The channel should contain a pore-forming subunit permitting rapid ion conduction.

-

2)

When reconstituted into an artificial, cell-free lipid bilayer, the purified channel should gate when tension is applied to the bilayer.

-

3)

Site-directed mutagenesis of critical channel domains that affect pore selectivity or conductance should alter mechanosensitivity.

-

4)

Forced expression of the channel in a nonmechanosensitive cell should confer mechanosensitivity.

-

5)

Both gene and protein of the channel must be expressed in the purported mechanosensitive cell.

-

6)

Genetic deletion of the channel should abolish mechanosensitivity in a way that rules out the channel having only a developmental role or being a downstream signaling component of another mechanosensor. [However, genetic deletion can disrupt normal signaling complexes, leading to off-target effects, so that the expression of a dominant-negative (dead) channel construct may be an even better approach.]

Whether these criteria are sufficient to distinguish true mechanosensitive channels from those that are indirect mechanosensors is a matter of debate, and this issue is revisited in the summary sections for VSMC and EC ion channels.

Although multiple ion channels have been implicated in mechanosensing, the criteria above are met by only a few select ion channels, including the bacterial channels MscS and MscL and the mammalian channels Piezo1–2, TREK-1/2, TRAAK, and possibly ENaC and ASIC (195, 208). The first truly mechanosensitive ion channels, MscS and MscL, with small and large conductances, respectively, were identified in bacteria (209, 210). When reconstituted into liposomes, the channels retained mechanosensitivity without the need to include other proteins (e.g., CSK components). Under these conditions, membrane tension was altered by incorporation of asymmetric lipids into the two leaflets, and the relationship between channel open probability (Po) and tension was described by a Boltzmann function (211). Mutations in critical domains of MscS and MscL modulated their mechanosensitivity (212), and their combined genetic deletion abolished the response to osmotic swelling (208). Although MscS and MscL exhibit “high-threshold” mechanosensitivity and respond only to near-lytic membrane tensions (188, 196), their properties fulfill many of the requirements for mechanosensitivity proposed above. Mammalian channels such as Piezo1, TREK-1/2, and TRAAK exhibit lower thresholds for mechanosensitivity.

Not all investigators agree that such strict criteria should be applied to eukaryotic mechanosensitive ion channels (152, 198, 208, 213). In eukaryotes, mechanosensitivity may be inherent to not only the pore-forming subunit but also the auxiliary channel subunits, specialized lipid domains such as rafts, and/or CSK-tethering proteins (214, 215). A focus on forces that act only in the plasmalemmal bilayer may oversimplify how stress is distributed to many other elements of the cell, including the CSK, attachment sites to the extracellular matrix (ECM), and cell-cell junctions. Thus, although a mechanosensitive ion channel may change its conformation under stress and become activated (or inactivated) in response to increases in bilayer tension, those changes are also transmitted to the CSK (198), which is composed of multiple elements that bear and distribute a variable fraction of the imposed stress. Complicating this issue, force generated internally (e.g., by VSMC contraction) can be transmitted through the CSK network to the plasmalemma and associated scaffolding proteins, which could serve as a potential feedback mechanism for mechanosensitive ion channel inactivation. Because of this complex distribution of force, a stimulus such as osmotic stress can have widespread effects; for example, although osmotic swelling is predicted to increase tension in the cortical CSK, atomic force microscopy measurements show that the cortical CSK actually softens as the cell osmotically expands, presumably because of the redistribution of stress through internal CSK elements (216).

2.1.4. Basic mechanisms of ion channel mechanosensitivity.

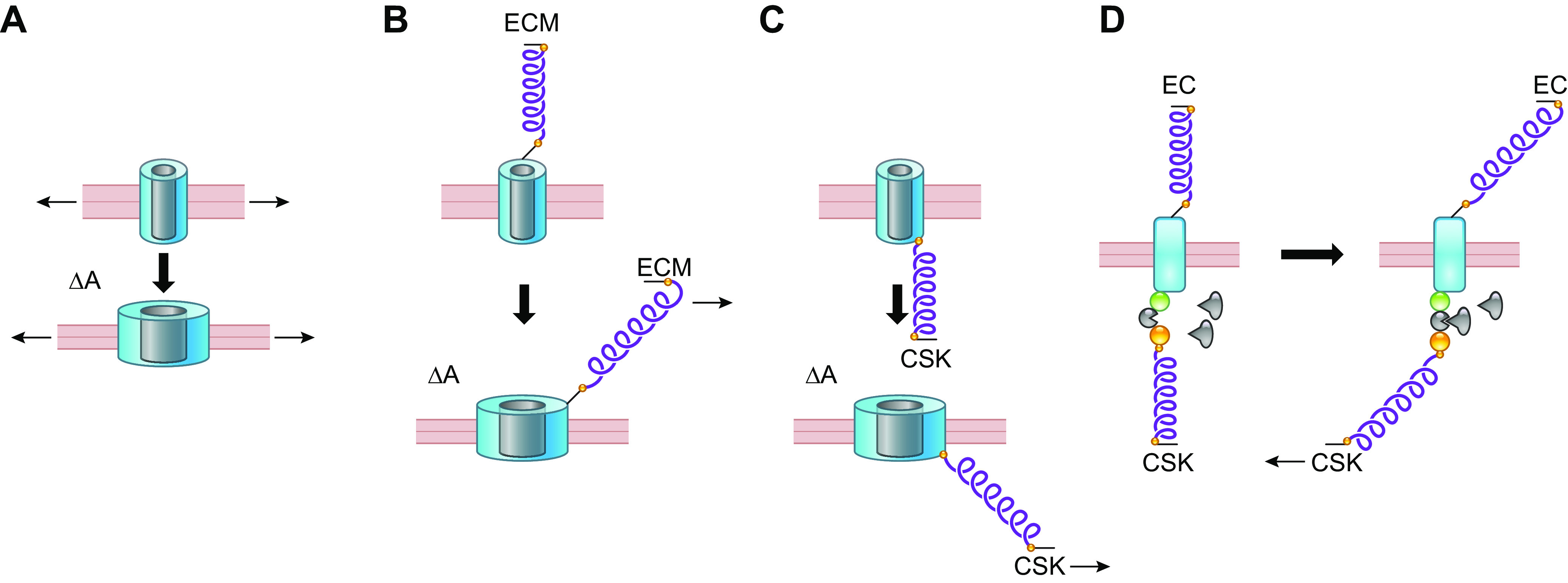

In line with the preceding discussion, two major hypotheses have been proposed for the molecular mechanism of mechanosensitive ion channel gating (FIGURE 10) (217–219): One involves forces intrinsic to the lipid bilayer, and the other involves tethering of the channel (or bilayer) to the CSK or other components. It is well established that some channels [e.g., MscS, MscL, Piezo1, two-pore domain K+ channels (K2P)] retain mechanosensitivity when purified and reconstituted into lipid bilayers in the absence of accessory subunits, CSK, and ECM components. The mechanosensitive gating of a channel resulting from increased bilayer tension is termed the “force-from-lipid (FFL) hypothesis,” which describes how force is transmitted from lipids to proteins (218). Proteins embedded in the membrane are subject to relatively large, anisotropic push-pull forces created by interactions of phospholipid polar head groups and interior acyl tails. At the lipid-water interface of each bilayer a large surface tension pulls outward on an embedded membrane protein, whereas at the bilayer midplane lateral compressive forces push inward (196, 220–222). The crystal structures of MscL and K2P channels provide insight into how changes in membrane tension might alter channel gating (223, 224): tension applied to the bilayer causes it to “thin” (FIGURE 10A), increasing the surface area (ΔA) of the channel and opening the pore (225, 226). Structural analyses also reveal the intimate association of lipid subpopulations with certain channel domains, facilitated for example by interactions between negatively charged phosphatidyl groups and positively charged arginine residues, as in the voltage sensor of Kv channels (188, 227–229). Thus, changes in tension may alter interactions of the channel protein with annular lipids to alter gating (196, 230). The maintenance of mechanosensitivity by the mammalian channels K2P and Piezo in isolated bilayers (203, 231) suggests that FFL is a general principle that applies to both prokaryotic and eukaryotic channels (218). FFL explains the requirement of Kir channels for an interaction with cholesterol (sect. 2.5.3) and the influence of fatty acids on K2P channel gating (sect. 2.5.5).

FIGURE 10.

Possible mechanisms for gating a mechanosensitive ion channel. A: changes in bilayer tension alone. B: tension applied to channel through ECM tether. C: tension applied to channel through CSK tether. D: tension on 1 or more tethers exposes an intracellular binding domain. See glossary for abbreviations. Modified from Refs. 217–219, with permission from Developmental Cell, Pflügers Archiv, and Nature, respectively.

Despite evidence in support of FFL, many channels behave differently in native cells than they do after reconstitution into lipid bilayers. For example, Piezo1 channels lose their normal property of rapid inactivation when studied in bilayers (203), possibly because of disruption of their normal association with STOML3, an integral membrane scaffolding protein. Piezo1 sensitivity in sensory neurons to a standardized mechanical stimulus is reduced fivefold after genetic deletion of STOML3 (214). Although the cortical CSK provides stability to the membrane bilayer (218), proteins such as β-spectrin and ankyrin that link the plasma membrane to the cortical CSK, as well as actin, which links the cortical and internal CSK elements, have been demonstrated to be critical for force transmission to mechanosensitive channels in other systems (215, 232, 233). These and many other observations suggest that tethers between channel proteins and ECM proteins (FIGURE 10B), or between channels and CSK components (FIGURE 10C), may be critical to confer normal mechanosensitivity to an ion channel. Ideally, evidence for mechanosensitivity should be supported by studies in intact systems. For example, Caenorhabditis elegans touch receptors are known to be tethered to complexes of both CSK and ECM proteins (208, 219), as discussed in sect. 2.2.2. Tethering may serve as a force multiplier, acting as a lever through which mechanosensitive channels with poor sensitivity can respond to weak but physiologically relevant forces (234). This is sometimes referred to as the “force from filament” mechanism (235). Indeed, there are many precedents at the cellular and multicellular levels for the advantage of a tethered force transmission system, including the tip link connectors in cochlear hair cell stereocilia (236) and the lanceolate endings in skin hair cells, both of which amplify the displacement associated with a given force. Another mechanism by which mechanical forces could gate an ion channel is through CSK and/or ECM tethers that result in the exposure of cryptic intracellular domains upon force application, allowing intracellular domains of the channel to interact with cytoplasmic proteins such as kinases to alter channel activity by phosphorylating critical residues (FIGURE 10D). Although the latter mechanism has not yet been described for a mechanosensitive ion channel, its relevance to other proteins is mentioned in sect. 5.2.

2.1.5. Mechanoprotection of ion channels?

Morris has argued (189, 237) that, because of the susceptibility of ion channels and other transmembrane proteins to mechanical deformation of the lipid bilayer, almost any large protein can potentially be mechanosensitive and that “mechanoprotection” measures, such as the cortical CSK (201), may be needed to delineate and/or protect specific mechanotransduction mechanisms. An example of delineation is the tethering protein system that enables vestibular hair cell ion channels to respond exclusively to mechanical deflection along the tip link axis (238, 239). Examples of protection include the regulation of TREK-1 by the actin CSK (240) and the inhibitory effects that the cortical actin cross-linking protein FlnA (241) normally exerts on the activity of Piezo1 (242) and on the interactions of TPPP1/TRPP2 (243) in VSMCs, such that SM-specific FlnA deletion enhances the stretch sensitivity of both Piezo1 and TRPP1. TRPP1/2 have also been shown to regulate MLC20 phosphorylation and cellular stiffness (244), implying that the function of one class of ion channel can indirectly alter the mechanosensitivity of other classes of channels. The preservation of ion channel interactions with their native lipid microdomains, auxiliary subunits, membrane scaffolding proteins, and other components that may tonically inhibit channel activity is critical to proper interpretation of data regarding mechanosensitive VSMC ion channels. These mechanoprotection mechanisms are likely to be reinforced at the multicellular/tissue level by the ECM and cell-cell junction proteins.

2.1.6. Use of inhibitors to study mechanosensitive ion channels.

In native cell systems including VSMCs, assessing the role of mechanosensitive ion channels is a complicated issue because there may be multiple types of mechanosensitive channels and they are likely to be present at much lower densities than those studied in heterologous expression systems. In addition, ion flux through a mechanosensitive channel can potentially gate a nonmechanosensitive channel (245). Multiple studies of VSMC mechanosensitivity have based their conclusions on the use of inhibitors such as the trivalent lanthanide Gd3+ (184, 245–247), ruthenium red (248, 249), or the tarantula toxin GsMTx4 (250–252). Although some studies have found that Gd3+ blocks or attenuates the vascular myogenic response (253), Gd3+ blocks almost every calcium entry pathway and is a well-known inhibitor of voltage-gated sodium channels (254), voltage-gated calcium channels (255–258), and Kv channels (259). Ruthenium red is an ion channel pore blocker (260) but it also blocks ryanodine receptors (261) and inhibits mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (262). GsMTx4 was originally screened as a selective inhibitor of cationic mechanosensitive channels (263, 264), and multiple studies have found that GsMTx4 inhibits the myogenic response to various degrees (167, 265). However, GsMTx4 is now known to block other classes of ion channels and nonchannel targets (266–271), and it may directly alter the properties of the lipid bilayer (272). Because L-type calcium channels and MLC20 phosphorylation are required for VSMC contraction and are presumably downstream from mechanosensitive elements, the use of inhibitors with off-target effects on these proteins may yield misleading conclusions. The molecular identification of specific ion channel families and screening of more specific inhibitors, as well as the use of RNA-knockdown approaches and genetically modified mice, have subsequently led to a better understanding of the mechanosensitive ion channels underlying pressure-induced arterial constriction and flow-mediated dilation.

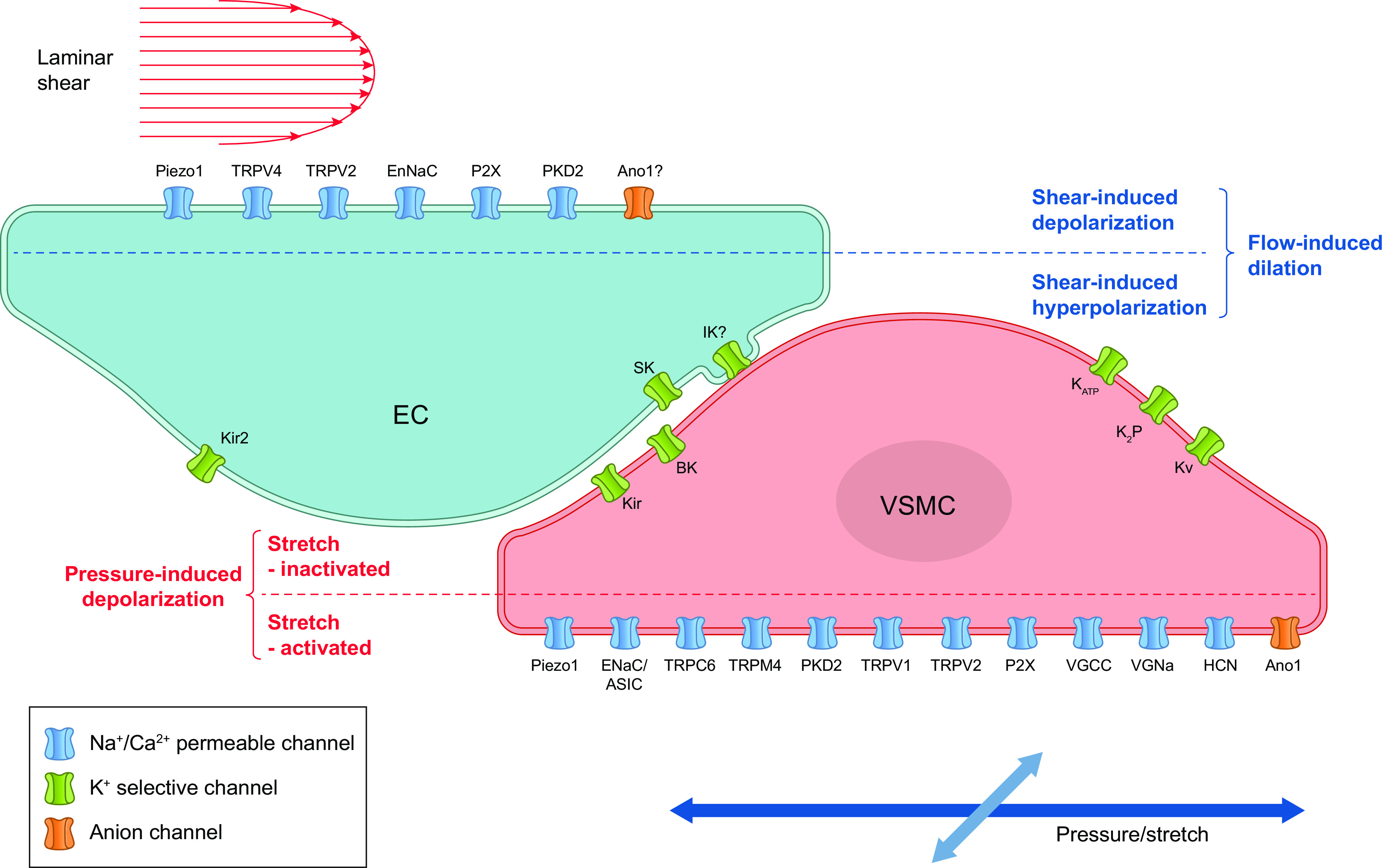

Mechanosensitive ion channels are a likely explanation for both the rapid depolarization of VSMCs in response to elevated pressure and the rapid hyperpolarization of ECs in response to elevated shear stress. The ion channels that could potentially account for these processes are depicted in FIGURE 11. In the following sections we examine the evidence for each of these channels in vascular mechanotransduction, starting with nonselective cation channels (Piezo, ENaC, ASIC, TRPs, P2X), then chloride channels, voltage-gated cation channels (Cav1.2, Cav3, Nav, HCN), and K+ channels (Kv, KCa, Kir, KATP, K2P). We conclude the section with integrative summaries and tables to assess the most relevant ion channels involved in EC and VSMC mechanotransduction.

FIGURE 11.

Ion channels in ECs and VSMCs that could potentially account for, or contribute to, flow-induced dilation and pressure-induced depolarization/constriction, respectively. Shear stress-induced activation of cation and Cl− channels in ECs can produce depolarization, but the EC response is normally dominated by the activation of K+ channels, leading to a net hyperpolarization. See glossary for abbreviations.

2.2. Nonselective Cation Channels

2.2.1. Piezo channels.

Piezo1 and Piezo2 are perhaps the best-characterized eukaryotic mechanosensitive channels. Piezo1 was first identified by the Patapoutian laboratory in 2010 (273). It is the largest known ion channel, with a molecular mass of ∼1 million daltons and an estimated 18–38 transmembrane domains. Functional Piezo1 channels are thought to form a trimeric complex of identical subunits (203, 274), in contrast to the more common four-subunit structures of TRP channels and voltage-gated Na+, K+, and Ca2+ channels. The Piezo1 structure is also unique in that it contains a large extracellular COOH-terminal domain, which forms an inverted dome that indents into the plasma membrane and may be critical for sensing membrane tension (275–277). Piezo1 and Piezo2 are nonselective cation channels that are slightly more permeable to Ca2+ than to monovalent cations (273); the relative permeability of Piezo1 to monovalent cations is PK > PCs > PNa > PLi (1.0:0.9:0.8:0.7). Piezo1 has a single-channel conductance of ∼115 pS in equimolar K+ (203) but a lower conductance of ∼30 pS if Ca2+ is present (278), as would occur under physiological conditions. Piezo2 has a lower single-channel conductance. Both Piezo1 and Piezo2 rapidly activate and inactivate in response to mechanical force (279), with Piezo2 exhibiting faster inactivation than Piezo1 (278). Selective pharmacology for Piezo channels is limited. Piezo channels are blocked by “classical” chemical antagonists of mechanosensitive channels, including Gd3+, ruthenium red (278), and GsMTx4 (280). Small-molecule screens identified Yoda1 as a Piezo1 activator (EC50 ∼20 μM) (281) and Dooku1 as a reversible antagonist of Yoda1 that lacks agonist activity (282). Specifically, Yoda1 prolongs activation but does not activate the channel in the absence of force. Yoda1 also has effects on cellular processes that are independent of Piezo1 (283). Although these agonists and antagonists have been widely used in vivo, the functional effects they may produce are not definitive evidence for Piezo1 involvement.

Piezo1 meets most or all of the six criteria listed for inherent mechanosensitivity in sect. 2.1.3. When recombinant Piezo1 channels are incorporated into droplet bilayers with asymmetric lipids, the channels are constitutively active. In contrast, channel activity is absent when incorporated into symmetric lipids, but interventions that increase membrane tension, including hyperosmotic solutions or solvent injection into the cis (intracellular) side (203), lead to channel activation (e.g., see Figure 2 in Ref. 203). In the absence of these stimuli, application of Yoda1 can also stimulate the channel (281). These same interventions do not activate KcsA channels (non-mechano-gated bacterial channels) incorporated into similar droplet bilayers. Heterologous expression of Piezo1 in N2A or HEK cells results in rapidly activating and inactivating inward currents upon application of patch pipette suction that exhibit sigmoidal (Boltzmann) activation as a function of pressure (e.g., see Figure 1 in Ref. 273). Finally, substitution of E2133A mutant Piezo1 channels, with altered pore properties (284), results in ∼50% decrease in single-channel conductance (203). Although these observations fulfill most of the criteria for true mechanosensitivity, the behavior of Piezo1 channels in a bilayer do not recapitulate all its characteristics in native cell systems, such as rapid inactivation. Additional proteins appear to be involved in modulating Piezo mechanosensitivity, including scaffolding proteins such as STOML3 (214), CSK proteins such as FlnA (242), and small molecules such as phosphoinositides (285).

Many lines of evidence support functional roles for Piezo channels in a number of physiological processes. Both gain-of-function and loss-of-function mutations in Piezo1 and Piezo2 have been linked to multiple human diseases (286), including dehydrated hereditary xerocytosis (287, 288), arthrogyropsis (289), and congenital lymphatic dysplasia (290, 291).

Piezo1 is highly expressed in a number of cells of the cardiovascular system, including VSMCs (242), ECs (292), and red blood cells (RBCs) (3, 195). Piezo2 channels appear to be expressed chiefly in peripheral neurons, where they are critical for the normal functioning of nearly all types of low-threshold (i.e., light touch) mechanoreceptors, including lanceolate endings and circumferential endings in hair follicles, as well as proprioception by Merkel cells and Meissner’s corpuscles (293–296). Combined genetic deletion of Piezo1 and Piezo2 from endothelium leads to developmental lethality in mice, indicating their requirement for the normal development of both blood (297) and lymphatic (298) vascular systems. The activation of Piezo1 by OS in developing lymphatic vessels could facilitate the Ca2+ entry required for nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) activation and subsequent induction of Foxc2, a transcription factor critical for valve development (292, 299). Conditional deletion of Piezo1 and Piezo2 (but neither alone) from sensory ganglia containing the baroreceptor cell bodies results in loss or attenuation of the baroreceptor-mediated heart rate reduction in response to blood pressure elevation and increased variability in 24-h blood pressure regulation (8), indicating that both channels are critical for baroreflex control of blood pressure in mice. Piezo1 is required for normal osmoregulation by RBCs, and its deletion leads to RBC dehydration and membrane fragility (3). Piezo1 is also critical for mechanosensitive release of ATP from RBCs (3, 4, 300), which is an important regulator of tone in the microcirculation, as RBCs constantly undergo large-scale deformation while passing through small arterioles, capillaries, and venules (301–304).

2.2.1.1. PIEZO CHANNELS IN VSMC MECHANOTRANSDUCTION.

Little is known about the roles of Piezo channels in VSMCs. The application of suction to cell-attached patches of VSMCs isolated from caudal arteries activated a stretch-activated, nonselective cation current that was nearly abolished in SM-specific Piezo1-knockout mice (242), suggesting that Piezo1 is expressed in VSMCs and can be activated by membrane deformation. Activation of a Piezo1-like current as a function of patch pipette suction in VSMCs (see Figure 2 in Ref. 242) followed a sigmoidal relationship similar to that of heterologously expressed Piezo1 channels. Interestingly, VSMCs from renal arteries and aorta exhibited much lower levels of stretch-activated current. Somewhat surprisingly, both caudal arteries and rostral cerebellar arteries from SM-specific Piezo-knockout mice, which express relatively high levels of Piezo1 compared with other arteries in wild-type (WT) mice, showed no significant defects in the development of myogenic tone, pressure-dependent vasomotion, or response to vasoconstrictors (242). Watts and colleagues (305) reported that the contractile properties of multiple arteries from rat were insensitive to the Piezo1 channel modulators Yoda1 and Dooku1. However, another study found that Piezo1 deletion from VSMCs substantially attenuated the remodeling of caudal arteries when mice were made hypertensive (242), suggesting that Piezo1 plays a role in long-term, but not acute, adaptive responses to elevated pressure (sect. 7.2). It is reasonable to expect that Piezo1 channels may be important for other aspects of VSMC function, but those roles remain to be elucidated.

In summary, Piezo channels meet all the criteria for bona fide mechanosensitive ion channels, can function as true mammalian mechanosensors, and are critical for multiple aspects of cardiovascular function, but they do not appear to play a significant role in acute, pressure-induced depolarization and contraction of VSMCs.

2.2.1.2. PIEZO CHANNELS IN EC MECHANOTRANSDUCTION.

Piezo1 is widely expressed in ECs and is essential for vascular development (93, 282, 297, 306). Only two studies have provided evidence that Piezo2 is expressed in ECs (307, 308), including one in which Piezo2 knockdown suppressed tumor growth via a reduction in angiogenesis (308). It remains to be determined whether Piezo2 is widely expressed in ECs and whether it is regulated by shear stress.

Piezo1 is an important component of a number of shear stress-induced processes in ECs. Evidence first presented by the Beech and Patapoutian laboratories demonstrated that Piezo1 channels were activated by shear stress and pressure (93, 297). Flow induced increases in intracellular [Ca2+] in several types of ECs [human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs), mouse embryonic ECs, and adult mouse mesenteric artery ECs] that were attenuated by Gd3+, GsMTx4, or EC-specific deletion of Piezo1 (Piezo1 ecKO) (93, 309). Patch-clamp recordings demonstrated that localized application of flow to whole ECs or to outside-out patches excised from ECs activated a nonselective cation current with a single-channel conductance of ∼25 pS (93, 309), consistent with the published characteristics of Piezo1 (273). These flow-evoked cation currents and Ca2+ increases were substantially impaired in Piezo1-deficient ECs (93, 309). Transfection of Piezo1 into HEK293 cells, which may not endogenously express Piezo1 (but see Refs. 310, 311 for contrary evidence), enabled them to respond to flow with Ca2+ influx (93, 297). A consistent observation in these protocols was a sustained activation of Piezo1 in native ECs as opposed to the activation and rapid inactivation of Piezo1 observed in heterologous expression systems. This finding may indicate the presence of as-yet-unidentified auxiliary proteins or interactions of Piezo1 with CSK/ECM elements in ECs, differing levels of sphingomyelinase activity, which modifies Piezo1 inactivation (312), or secondary activation of other channels/processes that depend on Piezo1-mediated Ca2+ influx, such as TRPV4 and/or ATP-P2Y2R signaling (300). The method of shear stress control in these electrophysiology studies was accomplished with a pressurized perfusion tube positioned near the patch-clamped EC, with shear stress subsequently estimated from the dimensions of the tube tip and/or particle tracking (297, 309). Under these conditions, the half-maximal shear stress for activation of Piezo1 expressed in HEK293 cells was 57 dyn/cm2 (297). In contrast, Piezo1-dependent Ca2+ increases in ECs were activated at shear stresses of 5–20 dyn/cm2 in a microfluidic chamber (93). The activation of Piezo1 channels in native ECs needs further investigation under controlled levels of shear stress to determine their threshold for activation, the extent to which they may be differentially activated by LS, OS, or PS, and the exclusion of other Piezo1-dependent Ca2+ influx mechanisms.

Shear stress activation of Piezo1 by itself would lead to EC depolarization, and this was indeed observed in sheets of mesenteric artery ECs, where flow induced ∼5-mV depolarization that was absent in Piezo1-deficient ECs (309). Piezo1-mediated depolarization appeared to be conducted through myoendothelial gap junctions (MEGJs) to the VSMC layer to activate VGCCs. In isolated mouse mesenteric arteries, luminal flow induced vasoconstriction (rather than vasodilation) and that response was abolished in Piezo1 ecKO mice (309). The authors proposed that flow-induced constriction through Piezo1 activation in exercise would facilitate shunting of blood flow away from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (although activation of the sympathetic nervous system is known to accomplish this). The observation that flow induced the constriction of mesenteric arteries conflicts with observations by other groups of flow-induced dilation in arteries from the mouse mesentery (300, 313) and other regions (for reviews see Refs. 71, 144), so the differences await explanation. In most cases, the depolarizing effect of EC Piezo1 activation in response to shear stress is presumably masked or overwhelmed by the simultaneous activation of Kir2 channels, which leads to net EC hyperpolarization (313, 314) (see sect. 2.5), although it is possible that this does not occur in all arteries. A hyperpolarized endothelium would increase the driving force for Ca2+ entry into the EC cytosol, implying that the major effect of Piezo1 activation in this context may be to increase EC Ca2+ conductance. Both mechanisms acting in concert would promote increases in EC [Ca2+].