Abstract

To process sensory stimuli, intense energy demands are placed on hair cells and primary afferents. Hair cells must both mechanotransduce and maintain pools of synaptic vesicles for neurotransmission. Furthermore, both hair cells and afferent neurons must continually maintain a polarized membrane to propagate sensory information. These processes are energy demanding and therefore both cell types are critically reliant on mitochondrial health and function for their activity and maintenance. Based on these demands, it is not surprising that deficits in mitochondrial health can negatively impact the auditory and vestibular systems. In this review, we reflect on how mitochondrial function and dysfunction are implicated in hair cell-mediated sensory system biology. Specifically, we focus on live imaging approaches that have been applied to study mitochondria using the zebrafish lateral-line system. We highlight the fluorescent dyes and genetically encoded biosensors that have been used to study mitochondria in lateral-line hair cells and afferent neurons. We then describe the impact this in vivo work has had on the field of mitochondrial biology as well as the relationship between mitochondria and sensory system development, function, and survival. Finally, we delineate the areas in need of further exploration. This includes in vivo analyses of mitochondrial dynamics and biogenesis, which will round out our understanding of mitochondrial biology in this sensitive sensory system.

Keywords: zebrafish, hearing and balance, lateral line, hair cells, afferent neurons, mitochondria, in vivo imaging

Introduction

Mitochondria fulfill several roles that are critical to the function of energetically active cell types in the nervous system. One of the primary roles of mitochondria across cell types is the generation of energy in the form of ATP (Bertram et al., 2006). In addition to being the heart of cellular metabolism, mitochondria can regulate calcium homeostasis, which plays critical roles in development, synapse function, and cell death (Britti et al., 2018; Calvo-Rodriguez et al., 2020; Contreras et al., 2010; Wong et al., 2019). Mitochondrial homeostasis is dependent on balanced cellular metabolism and proper mitochondrial transport and turnover. Mitochondrial homeostasis in turn is important for cellular function and health. In line with this important role, mitochondrial dysfunction has been implicated in many disorders including both hearing loss and balance disorders (Holmes et al., 2019; Kokotas et al., 2007).

For proper hearing and balance, sensory hair cells and primary afferents work in concert to convey auditory and vestibular information to the brain. In both cell types, processing sensory information is energetically demanding. Hair cells require ATP for mechanotransduction, a process that converts sensory stimuli into graded changes in membrane potential (Shin et al., 2007). These changes in potential must be matched with sustained exocytosis at the hair cell synapse. For exocytosis, synaptic vesicles must be recruited, filled with glutamate and recycled, processes that are all highly dependent on ATP (Pulido and Ryan, 2021). Additionally, both hair cells and neurons rely on ATP-dependent ion pumps to maintain a polarized membrane; this is essential to generate graded potentials and action potentials respectively (Hall et al., 2012; Harris et al., 2012; McLean et al., 2009). ATP demands are met by oxidative phosphorylation within the mitochondria. Oxidative phosphorylation produces ATP but is also accompanied by a host of metabolic byproducts, including reactive oxygen species (ROS). A buildup of ROS can be detrimental to cells as ROS can cause the errant oxidation of cellular components (Franco and Cidlowski, 2009, 2009; Sies et al., 2017). Environmental cellular stressors can also damage mitochondria and increase ROS levels. In the inner ear, these stressors include ototoxic drugs, loud noise, and aging. In hair cells in particular, mitochondrial stress and ROS production appear to play a central role in cell death (Esterberg et al., 2016, 2014; Lukasz et al., 2022; Pickett et al., 2018).

Techniques and model systems to study mitochondria

To understand the role of mitochondria in hair cells and primary afferents, confocal microscopy, super-resolution microscopy, and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) have proven to be powerful ways to visualize these organelles in fixed preparations (Drerup and Nechiporuk, 2016; Pickett et al., 2018; Wong et al., 2019). Of the various fixed preparations, electron microscopy provides unparalleled resolution of mitochondria in cross sections. In addition, electron microscopic-tomography and serial block-face scanning electron microscopy (SBSEM) provide valuable information regarding the 3D morphology of organelles, including mitochondria, at high resolution (Anttonen et al., 2014; Bullen et al., 2015; Perkins et al., 2020; Vranceanu et al., 2012). Fixed images can provide valuable insight in different contexts such as development, pathological states, and changes associated with specific genetic backgrounds. The main limitation to fixed preparations is that many features that define mitochondria are challenging to interpret at single timepoints in fixed samples. Understanding mitochondrial health and function over time is critical to understanding their formation, function, turnover, and pathology.

To study additional mitochondrial features and to examine the temporal dynamics of these organelles, in vivo imaging is required. Currently it is challenging to study the mammalian inner ear in vivo. While cultured ex vivo explants of mammalian inner ear organs are invaluable and can be used for live imaging, they have limitations. For example, the inner ear can be damaged during dissection and once cultured, the organs can only be sustained for a limited time (Ogier et al., 2019). In contrast to the mammalian inner ear, the lateral line (LL) of zebrafish can be studied in vivo (Figure 1). The LL is a specialized hair cell-dependent sensory system that enables aquatic vertebrates to sense near field water movement (Bleckmann and Zelick, 2009). The sensory organs of the LL system contain clusters of mechanosensory hair cells in discrete structures called neuromasts (Figure 1A,D,F). Neuromasts distributed around the zebrafish head and along the body make up the anterior and posterior LL systems respectively (Figure 1A). The zebrafish LL forms rapidly between 1–4 days post-fertilization (dpf) and is fully functional by 5 dpf (Chitnis et al., 2012; Ghysen and Dambly-Chaudière, 2007, 2004; Suli et al., 2012). When the primary LL system is mature, each neuromast is innervated by approximately 4 primary afferent neurons. Approximately 40–50 afferent neurons extend axons from two ganglia, the anterior- and posterior-LL ganglia (aLLg and pLLg) to innervate neuromasts (Figure 1A–E) (Haehnel et al., 2012). Primary afferents contact hair cells to form ribbon synapses with bouton-like endings (Figure 1G, afferent terminals). Importantly, the LL is located superficially, just beneath the surface of the zebrafish skin. Furthermore, zebrafish are translucent at embryonic and larval stages, making it possible to visualize living cells within the LL. These characteristics make the LL an invaluable model to study hair cell systems in real time in an in vivo context.

Figure 1.

Mitochondria in the zebrafish lateral line system.

(A) Schematic of the zebrafish lateral line at 5 dpf. Anterior and posterior LL neuromasts (orange dots) are contacted by axons that project from neurons in the anterior LL ganglion (aLLg) and posterior LL ganglion (pLLg) respectively (green). Dotted rectangles outline the anatomical locations from which the pLLg (B), axon (C-C’), and axon terminals (E) beneath neuromast hair cells (F) are imaged. (B,C-C’,E) Transient transgenesis enables mosaic expression of mitotagRFP (magenta). This in vivo, sparse labeling approach enables visualization of mitochondria in a single pLLg soma (B, arrowhead), the axon extending from it (C-C’), and the axon terminal contacting the pLL neuromast hair cells (E). The stable transgenic line neurod:GFPnl1 (green) is used as a reference to mark all soma, axons, and terminals. (D) Schematic of a neuromast viewed from the side. Axons from LL neurons form basket-shaped processes that innervate neuromast hair cells at axon terminals. (F) Hair cells, viewed from the side, labeled with MitoTracker to visualize mitochondria (magenta). Using this live label, long tubular mitochondria can be observed. (G) Representative TEM showing mitochondria (m, purple) near the presynaptic ribbon body (pink) in the hair cell (beige), and near postsynaptic densities in the afferent axon terminal (green). (H) Schematic of the region within the dashed outline in panel G. Areas occupied by the hair cell, mitochondria, synaptic vesicles (circles), ribbon body, afferent terminal, and postsynaptic density are replicated. At the hair cell presynapse, CaV1.3 calcium channels allow entry of calcium. At the postsynapse sodium and calcium enter via glutamate receptors. The image in G was taken by Ron Petralia. Scale bars = 10 μm (B-C’), 5 μm (E, F), 1 μm (G).

Using the in vivo imaging advantages of the LL system, research over the past decade has revealed that this sensory system is reliant on a healthy mitochondrial population. Using TEM, mitochondria can be readily observed in the periphery of the LL at hair cell synapses where they are enriched near the hair cell presynapse or ribbon, as well as in the afferent terminals beneath the hair cells (Figure 1G, H). In addition to these synaptic sites, mitochondria are also present in other locations including the hair cell and afferent soma as well as along the peripheral axons of primary afferents (Mandal et al., 2018; Owens et al., 2007). Using the translucence of zebrafish to their advantage, many labs have utilized both fluorescent dyes and genetically encoded indicators (GEIs) to label and visualize the hair cells and afferent neurons of the LL system and organelles such as mitochondria within these cell types. These approaches have advanced our understanding of mitochondria in the LL sensory system. For example, in vivo dye labeling of mitochondria has shown that in LL hair cells, these organelles form densely packed networks (Figure 1F), rather than the simple structures observed in cross section using TEM (Figure 1G). In addition, in the LL afferents, in vivo studies have demonstrated that mitochondria undergo frequent transport between the soma and afferent terminals (Drerup et al., 2017). To date, fluorescent dyes and GEIs have been used in the LL to study mitochondria in the context of development, cellular function, metabolism, morphology, transport, turnover, and cell death. In this review, we detail the GEIs and fluorescent dyes that have been used to study mitochondria in vivo in hair cells and afferent neurons of the zebrafish LL system. We also discuss how these approaches are implemented. In the latter sections, we discuss the specific studies that have used these approaches and what they have taught us about the importance of mitochondria in sensory system health and function. We end by discussing future lines of research – mitochondrial biogenesis and dynamics – that could further expand our understanding of the impact of mitochondrial biology on sensory systems.

Section 1: Genetically encoded indicators to study mitochondria in vivo

GEIs and fluorescent proteins have been powerful ways to study mitochondria in vivo. This includes fluorescent biosensors to monitor ATP (ATPSnFR and PercevalHR), reactive oxygen species production (roGFP2 and TIMER), calcium (GCaMP and R-GECO1), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD(H)) (Rex-YFP) as well as fluorescent proteins to visualize mitochondria (GFP, TagRFP and mEos). A major advantage of GEIs and fluorescent proteins is that they can be subcellularly localized using signal sequences to analyze local metabolic processes. Using this approach, several GEIs and fluorescent proteins have been tagged to promote localization to mitochondria, specifically the mitochondrial matrix and outer membrane of mitochondria. The mitochondrial matrix can be targeted by fusing the signal sequence from cytochrome C oxidase subunit VIII (Cox8a) to a protein, while the signal sequence from the mitochondrial import receptor subunit Tom20 (Tomm20) can be used to anchor proteins to the outer mitochondrial membrane (Kanaji et al., 2000; Shu et al., 2011). Using these specific signal sequences, fluorescent proteins and GEIs have been used to monitor mitochondrial localization and morphology, matrix calcium, transport, and mitochondrial-linked oxidative byproducts. Here, we will discuss these GEIs, how they are utilized, and what they have taught us about mitochondrial biology in the LL sensory system (also see Table 1).

Table 1.

Genetically encoded indicators used to study mitochondria in the LL

| Genetically encoded indicator | Description of biosensor | Color: excitation wavelength | Hair cell, afferent or both | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mitoGFP mitoTagRFP |

Mitochondrial label | Green: 488 nm Red: 561 nm |

Afferents | (Drerup and Nechiporuk, 2016; Mandal et al., 2020) |

| mitoGCaMP3 mitoG-GECO1 mitoR-GECO1 |

Mitochondrial matrix calcium | Green: 488 nm Red: 561 nm |

Both | (Esterberg et al., 2014; Mandal et al., 2020; Wong et al., 2019) |

| mito-mEos | Mitochondrial turnover | Native: Green: 488 nm Converted: Red: 561 nm |

Both | (Mandal et al., 2020; Pickett et al., 2018) |

| mitoTIMER | Mitochondrial oxidation, accumulated | Reduced: Green: 488 nm Oxidized: Red: 561 nm |

Both | (Mandal et al., 2020; Pickett et al., 2018) |

| mito-roGFP2 | Mitochondrial oxidation, acute | Reduced: Green: 488 nm Oxidized: Blue: 405 nm |

Afferent | (Mandal et al., 2020) |

| PercevalHR | Cytosolic ATP/ADP | ATP: Green: 488 nm ADP: Blue: 405 nm |

Afferent | (Mandal et al., 2020) |

| ATPSnFR | Cytosolic ATP | Green: 488 nm | Afferent | (Mandal et al., 2020) |

| Rex-YFP | Cytosolic NAD+/NADH |

Green: 488 nm | Hair cell | (Wong et al., 2019) |

GEIs to analyze mitochondrial function

Perhaps the most well-known role of mitochondria is the support of cellular functions through the production of ATP. ATP is produced in mitochondria via oxidative phosphorylation (Figure 2). ATP levels can be measured in vivo using two GEIs, PercevalHR and ATPSnFR. PercevalHR is an ATP/ADP biosensor that closely matches the expected physiological ATP/ADP ratio (Berg et al., 2009; Tantama et al., 2013). The binding of ATP and ADP to PercevalHR are mutually exclusive and, upon binding, regulate the fluorescence emission intensity of PercevalHR when excited at 488 and 405 nm. ATP binding increases fluorescence intensity upon 488 nm excitation while ADP binding increases fluorescence upon 405 nm excitation (Tantama et al., 2013). ATPSnFR is a newer GEI engineered to detect ATP with a single excitation wavelength (Lobas et al., 2019). Upon ATP binding there is a conformational change that results in an increase in fluorescence intensity (with peak emission at 510 nm) that can be detected with 488 nm excitation. Unlike PercevalHR, ATPSnFR does not fluoresce in physiologically relevant ADP concentrations, and therefore strictly detects ATP concentration.

Figure 2.

Metabolism and ROS production in mitochondria.

Schematic model of mitochondrial structure and ion exchange mechanisms. The mitochondrion is composed of an outer and an inner mitochondrial membrane. The mitochondrial matrix is enclosed within the inner membrane. Folds in the inner membrane form compartments called the cristae. The inner membrane is where oxidative phosphorylation occurs. The ETC (yellow), oxidizes the electron carrier NADH into NAD+ to generate a mitochondrial membrane potential measured at ~−160 mV in the matrix side. ATP synthase (pink) uses this potential to generate ATP. Calcium enters the mitochondrion through calcium permeable channels (green) VDAC and MCU. NCLX (orange) contributes to calcium ion efflux out of the matrix and sodium and proton exchange. MPTP (blue) facilitates the catastrophic release of calcium from the mitochondrion, for example prior to apoptosis. Inset illustrates the process of ROS formation at the ETC. Oxygen is converted into superoxide radical, which is locally neutralized by SOD into H2O2 which may degenerate into derivative radicals or exit the mitochondrion.

To generate ATP, mitochondria rely on cofactors, including the electron shuttling agent NAD(H). Oxidation of NADH to NAD+ is required for ATP production in the electron transport chain (Figure 2). In addition, NAD(H) is essential for metabolic events within the TCA cycle (in the mitochondrial matrix) and glycolysis (in the cytosol). To monitor NAD+ and NADH, the GEI Rex-YFP can be used (Bilan et al., 2014). Rex-YFP can be excited at 488 nm. Rex-YFP fluorescence intensity increases with NAD+ binding and decreases with NADH binding. Therefore, higher Rex-YFP fluorescence intensity corresponds to a higher NAD+/NADH ratio. By targeting these sensors to the cytosol or mitochondria, ATPSnFR, PercevalHR, and REX-YFP provide valuable readouts related to mitochondrial function.

GEIs to analyze mitochondrial calcium

The genetically encoded calcium indicators GCaMP3, G-GECO1, and R-GECO1 have been successfully targeted to the mitochondria to measure mitochondrial calcium levels and dynamics (Akerboom et al., 2012). When calcium levels increase, a conformational change in the protein increases the fluorescence emission intensity. By targeting these indicators to either the mitochondrial matrix or outer membrane, these calcium indicators provide a way to monitor steady state mitochondrial calcium during homeostasis and calcium dynamics during pathological conditions, development, and activity.

GEIs to analyze mitochondrial oxidation

An important measure of mitochondrial health is reflected in oxidation of mitochondrial proteins. Within mitochondria, as part of oxidative phosphorylation, free radicals with unpaired electrons are generated. When O2 is reduced by these electrons, cytotoxic byproducts called reactive oxygen species (ROS) can be generated, including superoxide anions and hydrogen peroxide (Figure 2). Over time, as mitochondria age, ROS can accumulate. The GEIs TIMER and roGFP2 have been used to monitor ROS accumulation and assess mitochondrial redox homeostasis (Hanson et al., 2004; Hernandez et al., 2013). In its unoxidized (reduced) state roGFP2 is excited at 488 nm, but when it is oxidized roGFP2 is excited at 405 nm. To study mitochondrial oxidation and ROS, intensity of roGFP2 fluorescence emission upon 488 nm and 405 nm excitation are measured, and the oxidized/reduced ratio is taken. Importantly, roGFP2 oxidation is also reversible making it an acute sensor of mitochondrial oxidation. Similar to roGFP2, the GEI TIMER also shifts its excitation upon oxidation (Terskikh Alexey et al., 2000)(. TIMER is a mutated variant of DsRed. While TIMER has a with a similar emission spectrum as DsRed, the excitation of TIMER shift from 488 nm to 561 nm upon oxidation. In contrast to roGFP2, TIMER is irreversibly oxidized and therefore useful as a readout of a chronic or accumulated oxidation. When localized to the mitochondria, these proteins can serve as a readout of mitochondrial oxidative potential or chronic exposure to reactive oxygen species. Both indicators have proved useful in studying mitochondria aging, turnover, and pathology.

Fluorescent proteins to study mitochondrial location, turnover, and dynamics

Mitochondria are not stationary in cells. They are actively transported by motor proteins for localization and degradation, processes that are essential for the maintenance of mitochondrial and cellular health (Mandal et al., 2020). Mitochondria can be tracked for short (on the order of minutes) or long (hours to days) periods of time using different types of fluorescent proteins (Drerup and Nechiporuk, 2016; Mandal et al., 2018; Pickett et al., 2018). Short-term tracking is possible using uninterrupted imaging of mitochondrial-targeted fluorescent proteins such as GFP and TagRFP. In contrast, long-term tracking of organelles is more effectively accomplished by labeling organelles with photoconvertible proteins. Originally identified in coral, photoconvertible proteins, such as mEos, shift their excitation/emission spectra upon illumination with 405 nm light (McKinney et al., 2009). By tightly controlling illumination during conversion, mitochondrially targeted mEos can be used to label small subsets of mitochondria in individual cells. Careful imaging post-conversion can be used to monitor many aspects of mitochondrial biology including location and, indirectly, fission/fusion dynamics, and biogenesis. Together, short- and long-term imaging of mitochondria using these approaches can provide valuable information on the movement and turnover dynamics of this organelle in vivo.

Methods to express GEIs and fluorescent proteins to study LL mitochondria

To reliably express mitochondrial-relevant GEIs and fluorescent proteins in the LL, many stable transgenic lines have been established (Table 1). In the LL, myo6b and neurod1 promoters are commonly used to drive expression in hair cells or afferent neurons respectively (e.g., myo6b:tdTomatovo13 or neurod1:tdTomatovo12) (Obholzer et al., 2008; Toro et al., 2015). Additionally, a minimal promoter, along with a 3’ enhancer (SILL1) has provided another way to selectively express GEIs in the afferent neurons of the LL (e.g., en.sill,hsp70:mcherry) (Pujol-Martí et al., 2012). After a stable transgenic line is established, each transgenic adult zebrafish can be used to produce hundreds of embryos weekly. Within these embryos, there is reliable and consistent expression of the transgene that is maintained in subsequent generations. Furthermore, the lines can then be crossed to different genetic backgrounds, examined over development, and used in pharmacological studies or screens.

In addition to stable transgenic lines, mosaic or sparse expression using transient transgenesis has also proved to be a powerful way to examine mitochondria, especially in LL afferent neurons. For mosaic expression of GEIs and fluorescent proteins, embryos and larvae are examined in just days after DNA constructs are injected into zygotes. This expression method is similar to transfection methods utilized in cultured cell lines. Because plasmid DNA is mosaically inherited during cell division in early embryogenesis, by carefully titrating injection amounts, it is possible to target a small number of cells in zebrafish larvae. This mosaic labeling is a powerful way to parse out and study a single LL afferent soma, axon, and terminal (e.g., Figure 1B, C, E). The ability to fluorescently label mitochondria in an individual LL neuron and its axon facilitates the ability to visualize and track these organelles in real time (Drerup and Nechiporuk, 2016; Mandal et al., 2018). Tracking is considerably more difficult in a stable transgenic in which all neurons and therefore all axons in a nerve have fluorescently labeled mitochondria.

One consideration for using a mosaic labelling approach is that unlike stable transgenic lines, transgene expression is variable, due to minute differences in plasmid DNA inheritance. In some cases, variable expression is not critical, for example when using mosaic expression to visualize mitochondrial localization. When expression levels are important (e.g., intensity measurements), expression can be normalized to an internal control. Some GEIs have their own internal control, e.g., PercevalHR, TIMER, and roGFP2. These GEIs are measured using two wavelengths and the readout is ratiometric. Other GEIs require that an additional normalization factor be built into the expression construct. Typically, this is done by linking a control fluorescent protein (with a different excitation wavelength) to the GEI transcript using a viral p2a peptide. This peptide is used as a cleavage sequence which produces two separate proteins from the same transcript (Liu et al., 2017). For example, the GEI ATPSnFR (488 nm excitation) can be joined to mRuby (561 nm excitation) with a p2A peptide. In this way, in each cell, ATPSnFR measurements can be normalized to the mRuby intensity (ATPSnFR/mRuby), and comparisons can be made despite differences in expression level. When well controlled, transient transgenesis can be a valuable way to analyze mitochondrial parameters in individual LL neurons and hair cells in vivo.

Methods to monitor mitochondrial GEIs in the lateral line

Mitochondria and mitochondrial-relevant parameters in hair cells and afferent neurons are constantly in flux. GEIs are a powerful way to visualize the location and status of mitochondria steady-state and over various time windows (seconds to days). After a stable or mosaic expression of a GEI or fluorescent protein is established, whole larvae can be mounted and directly viewed or imaged on a compound, fluorescent microscope such as a laser scanning confocal microscope using 40–60x objectives with a high numerical aperture (0.8–1.4 N.A). To capture information at steady state, Z-stacks can be acquired in LL hair cells or LL afferent somas, axons, and terminals. Fluorescent signals in these Z-stacks can be used to assay mitochondrial size/density/load/location, ATP, and mitochondrial calcium levels as well as acute and accumulated ROS levels in the LL system (Mandal et al., 2020; Pickett et al., 2018; Wong et al., 2019).

In addition to information gathered at steady-state, GEIs and fluorescent proteins can be monitored continuously over short-time windows (seconds to minutes) to assess fluctuating mitochondrial parameters. One aspect of mitochondrial biology studied during a short-time window is mitochondrial calcium signals. Mitochondrial calcium dynamics have been studied in LL hair cells using mitoGCaMP3 and mitoR-GECO1. Here mitochondrial calcium uptake has been measured over 10–30 s during hair cell stimulation using a fluid-jet (Figure 3A, C) (Wong et al., 2019). In addition, mitochondrial calcium uptake has been measured during spontaneous events (10–20 min) and during cell death (60 min) (Esterberg et al., 2014; Wong et al., 2019) (Figure 3B, C).

Figure 3.

Mitochondrial calcium dynamics in lateral line hair cells.

(A-A”) Evoked mitoGCaMP3 responses in a mature hair cell (5 dpf) viewed from the side. Heatmaps show changes in mitoGCaMP3 fluorescent signal (A, inset) in a hair cell captured before (A), during (A’), and after (A”) delivery of fluid-jet stimulus. Heatmaps are overlaid onto the grayscale pre-stimulation images. White dotted line outlines one hair cell. (A’”) Temporal curves of the mitoGCaMP3 fluorescence intensity. The red, orange, and blue circles in A indicate the ROIs used for plotting the fluorescence intensity traces in A’”. Gray bar indicates the 2-s period of fluid-jet stimulus delivery. (B-B’) Spontaneous mitoGCaMP3 responses in developing hair cells (3 dpf) viewed from the top down. The Red, orange, green, and blue ROIs in B correspond to the temporal curves of the mitoGCaMP3 fluorescence intensity changes monitoring during the 600 s recording in B’. (C) Schematic model of the relationship between synaptic activity and mitochondrial-calcium uptake. In hair cells either evoked or spontaneous presynaptic-calcium influx (via CaV1.3 channels) triggers uptake of calcium into the mitochondria (via MCU and VDAC channels). Presynaptic calcium influx in hair cells triggers release of glutamate-filled synaptic vesicles onto afferent terminals. Upon release, glutamate binds to AMPA receptors at the postsynapse, triggering sodium and calcium influx through AMPA receptors composed of GluA2 or GluA2 and GluA3/4 subunits. The role of mitochondria in the afferent terminal with regards to calcium signaling is not completely understood. Scale bars = 5 μm.

Over short-time windows (5–10 min), mitochondrial movement in individual LL axons has been monitored in LL afferents using mitochondrially localized fluorescent proteins (Drerup and Nechiporuk, 2016). Transient transgenesis is especially useful for this type of tracking as it allows the labeling of mitochondria in individual neurons which is essential for analyzing mitochondrial movement parameters. For adequate sampling, images must be taken at least 2 times per second to capture the rapid nature of mitochondrial movement (~1 μm/sec). After image acquisition, mitochondrial density, frequency, and direction of movement as well as transport parameters (e.g., distance and velocity of individual movement bouts) can be ascertained. Similar methods can be used in long-term imaging to analyze mitochondria turnover and aging (Figure 5). This can be done in afferent axons using transient transgenesis (Figure 1B, C, E; Mandal et al., 2020) and in LL hair cells in stable transgenic lines (Pickett et al., 2018). These long-term analyses in the LL have provided important information regarding mitochondrial movement, turnover, and aging.

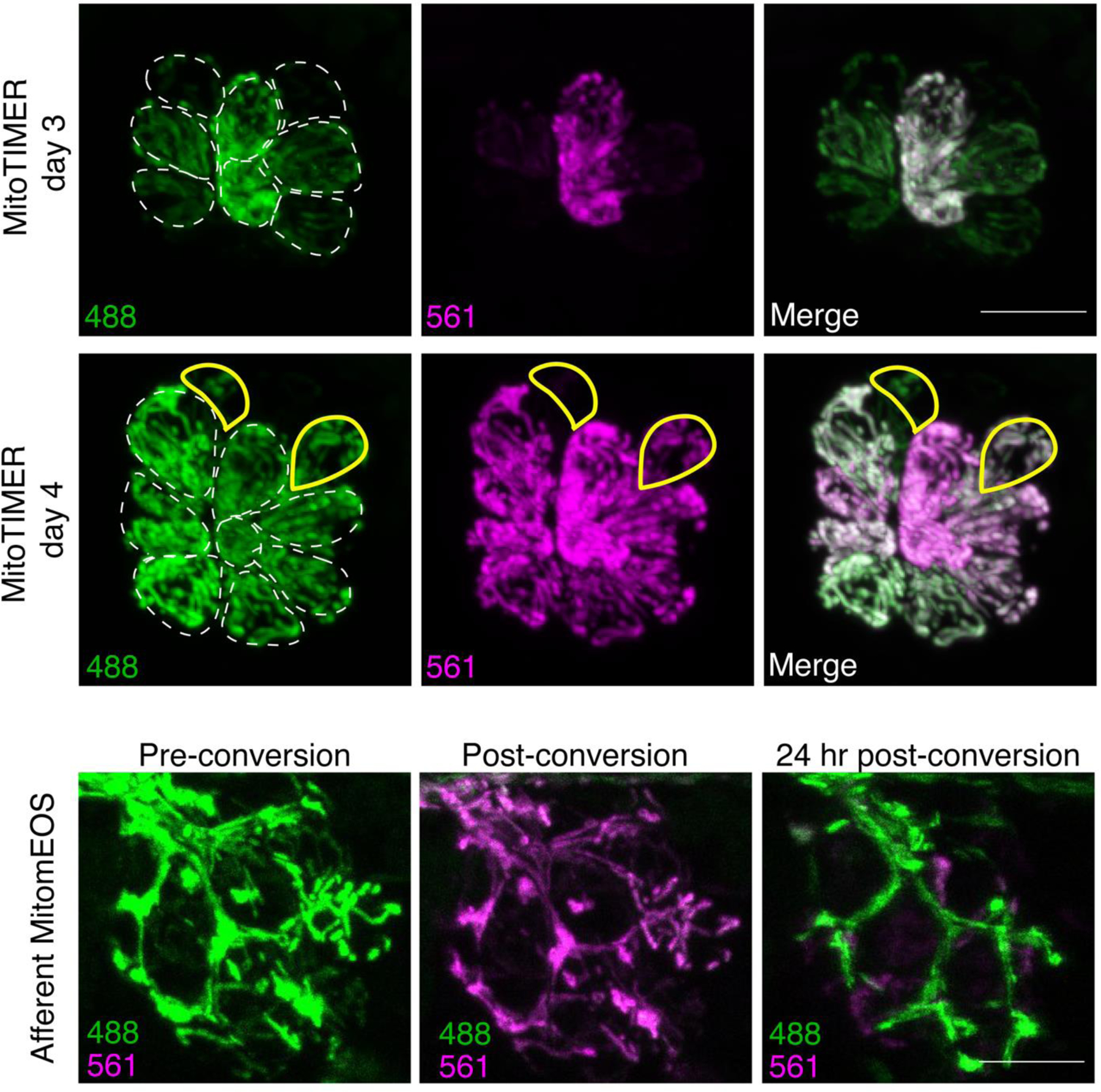

Figure 5.

GEIs can be used to monitor LL hair cells and afferent terminals over time.

Top panels. MitoTIMER can be monitored in subsets of LL hair cells as they age. Shown in this example are hair cells within the same neuromast at 3 and 4 dpf stably expressing the transgene myo6b:mitoTimerw208. Hair cells present at both imaging time points are outlined in white dotted lines. The mitoTIMER label in the white outlined hair cells shifts from a reduced form of TIMER (green) to an oxidized form of TIMER (shown as magenta) as the cells age for 24 hr. Hair cells differentiated between 3 and 4 dpf are outlined in yellow and show less of the oxidized form of TIMER. Bottom panels. Photoconvertible mitomEOS can be used to visualize mitochondrial lifetime in neurons. In the left panel, expression of mitochondrially-localized mEOS in the axon terminals stably expressing the transgene Tg(5kbneurod:mito-mEos)y586 at 4 dpf. In the middle panel, after 405 nm wavelength light exposure, mEOS is converted from green to red (shown as magenta). At 24 hr-post-conversion (5 dpf), minimal converted (magenta) mEOS remains in the axon terminal. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Section 2: Fluorescent dyes used to study mitochondria in vivo

In addition to GEIs and fluorescent proteins, fluorescent vital dyes are a powerful way to quickly visualize mitochondria and mitochondrial processes in vivo. These include dyes to monitor mitochondrial localization and morphology (MitoTracker and DASPEI), mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) (TMRE and JC-1) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (MitoSOX and CellROX) (Table 2) (Bone et al., 2013; Johnson-Cadwell et al., 2007). All these dyes are cell permeant. In addition, MitoTracker, DASPEI, TMRE, JC-1 and MitoSOX all carry a positive charge. The cationic charge of these dyes and the negative ΔΨm allow them to enter and localize in the matrix of the mitochondria. In contrast to these mitochondrial localized dyes, CellROX can localize more broadly within the cell.

Table 2.

Vital dyes used to study mitochondria in the LL

| Vital dye | Description of vital dye | Color: excitation wavelength | Concentration: incubation time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMRE | Mitochondrial membrane potential | Red: 561 nm | Hair cells: 1–25 nM: 20–30 min Afferents: 25 μM: 1 hr |

(Esterberg et al., 2013; Mandal et al., 2020) |

| JC-1 | Mitochondrial membrane potential | Low potential: Green: 488 nm High potential: Red: 561 nm |

Hair cells: 1.5 μM:30 min Afferents: n.d. |

(Pickett et al., 2018) |

| MitoTracker | Gross mitochondrial morphology, location and movement | Green: 488 nm Red: 561 nm Far red: 647 nm |

Hair cells: 100 nM: 5 min Afferents: n.d. |

(Holmgren and Sheets, 2021) |

| CellROX | General cellular oxidation | Green: 488 nm Red: 561 nm Far red: 647 nm |

Hair cells: 2–10 μM: 30–90 min Afferents: n.d. |

(Esterberg et al., 2016) |

| MitoSOX Red |

Mitochondrial superoxide | Red: 561 nm | Hair cells: 1–2 μM: 30–90 min Afferents: n.d. |

(Esterberg et al., 2016) |

Dyes to analyze mitochondrial distribution within the cell

Similar to the mitochondrial-localized fluorescent proteins discussed above (e.g., mitoGFP and mitoTagRFP), MitoTracker and DASPEI dyes provide a way to visualize mitochondria morphology and density. DASPEI is a vital dye that has been used to label and count LL hair cells in many assays (Harris et al., 2003). DASPEI localizes to mitochondria and fluoresces when excited at 488 nm. MitoTracker comes in several colors that have distinct excitation wavelengths (488 nm, 561 nm, 647 nm) (Chazotte, 2011). The 647 nm variant of MitoTracker is fixable. Although MitoTracker dye uptake depends on the ΔΨm, unlike the other fluorescent mitochondrial dyes (DAPSEI, TMRE, JC-1, and MitoSOX), once inside the mitochondrial matrix, MitoTracker is permanently sequestered. This sequestration makes it possible to label mitochondria even under conditions when the ΔΨm is diminished.

Dyes to analyze mitochondrial membrane potential

The mitochondrial matrix is negatively charged. This is due to the protein complexes within the electron transport chain which pump protons from the mitochondrial matrix into the intermembrane space. The potential of the mitochondrial matrix relative to the intermembrane space is ~−160 mV (Gerencser et al., 2012). Together with the proton gradient, ATP synthase uses the ΔΨm to synthesize ATP through oxidative phosphorylation (Figure 2). Therefore, deficits in ΔΨm are a key indicator of mitochondrial health or dysfunction. TMRE and JC-1 offer a direct readout of Δψm: the amount of the cationic dye that enters the mitochondrial matrix is directly proportional to the negative charge present within the matrix. TMRE is excited at 561 nm; an increase in TMRE fluorescence indicates a more depolarized Δψm and more active mitochondria. In contrast to TMRE, JC-1 is a ratiometric dye. JC-1 exists as a monomer at low concentrations and is fluorescent upon 488 nm excitation. At higher JC-1 concentrations (more depolarized Δψm), the dye forms J-aggregates that fluoresce at 561 nm (Reers et al., 1991; Smiley et al., 1991). For JC-1, more depolarized Δψm is indicated by an increase in the 561 nm to 488 nm fluorescence intensity ratio. TMRE measurements of Δψm can be impacted by factors that may influence fluorescence signals detected using a single wavelength, such as mitochondrial size, shape, and density. Because JC-1 is readout as a ratio of red-to-green fluorescence, it is primarily dependent only on the Δψm. Both TMRE and JC-1 are effective ways to analyze ΔΨm to assess mitochondrial health.

Dyes to analyze cellular and mitochondrial ROS

Cellular and mitochondrial ROS can be assayed by vital dyes CellROX and MitoSOX respectively. ROS are generated as byproducts of normal mitochondrial metabolism; ROS can build up over time or can be produced excessively under pathological conditions (Figure 2). While MitoTracker, DASPEI, TMRE and JC-1 robustly label healthy mitochondria at rest, MitoSOX and CellROX are nonfluorescent or very weakly fluorescent under homeostatic conditions but exhibit bright fluorescence upon oxidation by ROS (Dikalov and Harrison, 2014; Pyle et al., 2019). MitoSOX comes in a single variant, MitoSOX Red; this variant is excited at 561 nm and localizes to mitochondria. MitoSOX selectively detects superoxide, one of the main ROS produced by the mitochondria. In contrast, CellROX dyes are more general indicators of cellular ROS. CellROX dyes can permeate a number of intracellular compartments, including the cytoplasm, nucleus, and mitochondria. CellROX dyes come in several variants: CellROX Green, CellROX Orange and CellROX Deep Red that are excited at 488, 561 and 647 nm respectively. After CellROX Green is oxidized by ROS it subsequently binds to DNA (CellROX Green is a derivative of Ethidium Bromide) and then fluoresces (Pyle et al., 2019). In contrast, CellROX Orange and CellROX Deep Red do not require DNA binding for fluorescence, and upon oxidation by ROS, can fluoresce throughout the cell. Lot-to-lot variability of these ROS dyes has been noted previously (Esterberg et al., 2016). Due to this variability, careful attention should be paid to dye efficacy and samples should be normalized to a control tissue to assess dye labeling with each lot. Despite these limitations, these dyes are incredibly useful for measure cellular and mitochondrial ROS in vivo.

Methods to apply fluorescent dyes to study lateral line mitochondria

Fluorescent dye labeling using cell permeant dyes in zebrafish is straightforward in theory. Whole zebrafish larvae are simply immersed in zebrafish embryo media containing the dye of interest. After the labeling is complete, the larvae are washed, mounted, and in vivo LL labeling can be directly imaged on a laser-scanning confocal microscope with 40–60x objectives with a high numerical aperture (0.8–1.4 N.A) (e.g., Figure 1F). Table 2 outlines concentrations of fluorescent dyes along with incubation times that have been used to probe mitochondrial relevant information in LL hair cells and afferent neurons. In practice, fluorescent dye methods are dependent on several variables including the age of the animal (before or after 4 dpf) and the cell type being labeled (hair cells vs. afferent terminals). Current protocols are available for older larvae (Table 2 lists labeling conditions for larvae after 4 dpf) and careful titration of incubation times and concentrations is needed to establish labeling parameters for other, previously unutilized, developmental stages. In addition to age differences, fluorescent dye labeling requires different treatment conditions for hair cells (Alassaf et al., 2019) and afferent neurons (Mandal et al., 2018). Although many fluorescent dyes are listed as cell permeant, they do not have equal access to hair cells and afferent terminals. Hair cells are more superficial and tend to take up dyes more easily than afferent neurons. Furthermore, many cationic, fluorescent dyes (e.g., DASPEI, MitoTracker) can enter hair cells via mechanoelectrical transduction channels within 10s of seconds (Meyers et al., 2003). While both DASPEI and MitoTracker are extremely efficient at labeling hair cells, these dyes fail to penetrate LL afferent neurons effectively. Therefore, GEIs and fluorescent proteins remain the most effective way to analyze mitochondrial density in LL afferent neurons.

There are several factors to take into consideration when using fluorescent dyes. First, unlike GEIs where expression is maintained for days or even over the lifetime of the animal, most fluorescent dyes are cleared from cells after several hours. Dye clearance makes it challenging to track mitochondria-relevant information over longer time periods. Second, unlike stable transgenic lines that provide a consistent level of GEI expression, dye labeling can be variable. Therefore, to minimize variability, it is important to tightly control the dye concentration, incubation times, and wash out times used when labeling. Third, unlike GEIs, dyes will label all cells. To clearly delineate hair cell and afferent axon signals, the use of cell type specific markers can be used to identify and isolate the cell population of interest for analysis (Figure 6). Lastly, an important consideration when using these fluorescent dyes are the effects the dyes themselves may have on the cells and mitochondria. This is particularly true for cationic dyes that label the mitochondrial matrix. In essence, these dyes can alter the ΔΨm and impart negative consequences on mitochondrial health and productivity in the long term. This is of highest concern for TMRE (Scaduto and Grotyohann, 1999). Therefore, care should be taken to use low dye concentrations along with short incubation times to ensure minimal disruption to the natural state of the organelle. Despite these considerations, fluorescent dyes can be extremely advantageous. They can be used to study mitochondria in vivo and can be used without delay in any genetic background. In addition, dyes can be combined with transgenic lines to increase the power of analyses. For example, TMRE can be combined with mitoGCaMP3 to measure Δψm and mitochondrial calcium simultaneously (Esterberg et al., 2014). Overall, when fluorescent dyes are used properly, they represent a fast and powerful in vivo way to visualize mitochondria in hair cell systems.

Figure 6.

Image subtraction to visualize and quantify dye label in LL axon terminals.

(A-F) Example TMRE labeling to visualize mitochondrial matrix potential in LL neuromasts. (A-B) Expression of cytosolic GFP in the LL terminal of a TgBAC(neuroD:eGFP)nl1 transgenic larvae. (B) TMRE, when applied to the larvae, accumulates in the negatively charged mitochondrial matrix of all cells at a rate relative to membrane potential. The dye preferentially accumulates in hair cells within the neuromast. (C-D) Image subtraction of the TMRE Z-stack (C) by the cytosolic GFP stack allows for the isolation of TMRE signal in the afferent terminals from extraneous TMRE labeling (shown in D). (E) Sum-projection of TMRE signal in the mitochondrial matrix within LL axon terminals. (F) Merged sum-projection of cytosolic eGFP (green) and TMRE signal (magenta, white when colocalized with eGFP). Scale bar = 10 μm.

Section 3: Studies on mitochondrial calcium in the lateral line

Calcium is critical to mitochondrial function. Calcium levels within the mitochondrial matrix can help maintain the ΔΨm to drive ATP synthesis (Poburko et al., 2011). Additionally, mitochondria are thought to serve as a calcium buffer. Mitochondria take up calcium near hotspots of activity such as synapses or at close contacts with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Calcium influx into the mitochondria is also important in initiating cell death (Calvo-Rodriguez et al., 2020; Contreras et al., 2010; Esterberg et al., 2014). Calcium signaling also plays important roles in both mitochondrial transport and localization as well as mitochondrial biogenesis and turnover (Diaz and Moraes, 2008; Misgeld and Schwarz, 2017). Within mitochondria, calcium entry and exit are controlled by several channels. Calcium enters the mitochondria from the cytosol into the mitochondrial intermembrane space via voltage-dependent anion channels (VDACs) and continues into the mitochondrial matrix via the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) complex (Chaudhuri et al., 2021; Shoshan-Barmatz et al., 2018). In contrast, the sodium calcium exchanger (NCLX) allows calcium to leave the mitochondria (Palty et al., 2010) (Figure 2).

Disruptions in mitochondrial calcium flux are associated with loss of or damage to hair cells, synapses, and primary afferents (Esterberg et al., 2014; Holmgren and Sheets, 2021; Liu et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2019). For example, exposure to insults such as ototoxins or loud noise can trigger a significant influx of calcium into hair cells or afferent terminals. Work in mouse auditory hair cells indicates that during overstimulation, such as loud noise, calcium influx through the MCU is implicated in calcium overload. This overload can lead to hair cell death and may contribute to noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) (Kurabi et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2021; Shen et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2019). Although mitochondrial calcium uptake has not been directly implicated in the loss of afferents neurons, it has been associated with neuronal death in other contexts and is thought to contribute to neurodegeneration (Calvo-Rodriguez et al., 2020; Ludtmann and Abramov, 2018). Furthermore, disruptions in mitochondrial calcium homeostasis have the potential to disturb other important physiological functions. For example, calcium flow into mitochondria helps to regulate PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1) signaling, which protects cells by inducing mitophagy, a process that degrades damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria (Quinn et al., 2020). In Parkinson’s disease, failure to clear damaged mitochondria through this calcium-mediated pathway is implicated in disease pathology (Ashrafi and Schwarz, 2013). Importantly, mitophagy impairment has also been implicated in age-related hearing loss (Youn et al., 2020).

Mitochondrial calcium and lateral line synapse function

Mitochondria are known to cluster most densely at calcium hotspots such as the presynapse in hair cells and the postsynaptic density in primary afferents (Figure 1G) (Datta and Jaiswal, 2021; Wong et al., 2019). In hair cells, calcium enters near presynaptic sites through L-type voltagegated Cav1.3 calcium channels (Figure 1H). Presynaptic calcium influx via Cav1.3 channels is essential for neurotransmission in both mouse and zebrafish hair cells (Brandt et al., 2003; Sidi et al., 2004). Calcium influx at postsynaptic sites in primary afferents is also associated with neurotransmission. The localization of mitochondria at these pre- and post-synaptic calcium hotspots can have critical implications for the health and function of hair cells and neurons.

Work in the LL has shown that during hair cell stimulation, mitochondria robustly take up calcium (Wong et al., 2019). Using mitoGCaMP3, this work found that calcium uptake occurs adjacent to the hair cell presynapse, near sites of neurotransmission (Figure 3A). In addition, this work also assessed the role of this mitochondrial calcium uptake in presynapse function (Wong et al., 2019). For this analysis, a transgenic line expressing membrane-localized GCaMP6s in LL hair cells (myo6b:GCaMP6sCAAXidc1) was used to measure evoked, presynaptic calcium responses. After blocking mitochondrial calcium uptake, a dramatic reduction in presynaptic calcium influx was observed. Overall, it is likely that evoked mitochondrial calcium uptake ultimately modulates cellular metabolism to affect synaptic activity. Future work combining GEIs of ATP with genetic or pharmacological manipulations of mitochondrial calcium could be used to understand this relationship in more detail.

Studies in many neuronal subpopulations have demonstrated that mitochondria localize near postsynaptic sites and take up calcium during stimulation (Devine and Kittler, 2018; Ly and Verstreken, 2006; Pivovarova and Andrews, 2010). The terminals of afferent neurons that contact LL hair cells also contain mitochondria (Figure 1G). Work using GCaMP6s expressed in the LL afferent neurons has demonstrated postsynaptic calcium influx into afferent terminals in response to hair cell stimulation (Ji et al., 2018; Sebe et al., 2017). Evidence in mice and zebrafish indicates that this calcium influx occurs through GluA2-lacking calcium-permeable AMPA receptors (CP-AMPARs) present at the postsynapse (Sebe et al., 2017) (Figure 1H, Figure 3C). However, there have been no studies examining whether mitochondria take up calcium in the LL axon terminals during hair cell stimulation. In the future it will be interesting to examine whether, similar to LL hair cells, mitochondria in afferent terminals also take up calcium during stimulation and impact postsynaptic function.

Mitochondrial calcium and lateral line synapse formation

In addition to studying the relationship between mitochondrial calcium and synapse function, work in the LL has also examined its role during development. This work used mitoGCaMP3 to show that in developing LL hair cells, mitochondria spontaneously take up calcium. Importantly, this work found that this calcium uptake is essential for regulating presynaptic, but not postsynaptic size (Wong et al., 2019). When spontaneous mitochondrial calcium uptake was blocked using pharmacology, presynapses were significantly enlarged in developing LL hair cells. This pharmacological treatment did not impact postsynapse size, however, suggesting a specific role for mitochondrial calcium uptake in presynapse formation during development. Mechanistically, this aspect of presynapse formation was linked to an important part of mitochondrial metabolism, the NAD+/NADH redox balance (see Section 4).

Mitochondrial calcium in pathology and death in the lateral line

Mitochondrial calcium is critical for cell homeostasis and under pathological conditions can trigger cell death. In hair cells of mice and zebrafish, mitochondrial calcium flux has been implicated in pathological processes. In vivo approaches have been used to examine changes in cytosolic and mitochondrial calcium in the LL hair cells during exposure to several types of insults. For example, studies in LL hair cells have investigated pathological changes in mitochondrial calcium after exposure to ototoxic aminoglycoside antibiotics (Esterberg et al., 2014, 2013). This work used a variety of dyes and transgenic lines to link ΔΨm and the flux of calcium between the cytosol, ER, and mitochondria during aminoglycoside-induced hair cell death. Using TMRE and cytoGCaMP3, it was shown that a drop in ΔΨm is followed by sharp rise in cytosolic calcium preceding cell death (Esterberg et al., 2013). Subsequent work revealed the likely source of this calcium spike. Prior to the spike, calcium flows out of the ER into the mitochondria. This results in a rise in mitochondrial calcium (mitoGCaMP3) that is closely mirrored by increases in ΔΨm (TMRE). When the ΔΨm reaches excessive levels, the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opens, resulting in a catastrophic loss of the ΔΨm and calcium release into the cytosol. Disrupting the transfer of calcium from the ER to the mitochondria was able to prevent hair cell death (Esterberg et al., 2014). Importantly, this work was able to break this process down in real time using in vivo two-color imaging. This work in LL hair cells has been invaluable to our understanding of the cascade of events that leads to hair cell death.

While less well studied, changes in mitochondrial calcium handling may also be involved in neurodegenerative processes in afferent terminals of sensory systems as well. Increases in mitochondrial calcium have been detected in damaged neurons following axonal injury, and it is hypothesized that mitochondrial calcium overload contributes to axonal degeneration (Vargas et al., 2015). In the mammalian auditory system, loud noise is damaging to hair cells and afferent neurons (Fernandez et al., 2020; Kurabi et al., 2017). Mechanistically, this damage may be due to calcium elevation after excitotoxic stimulation of afferent neurons (Hu et al., 2020). In support of this, work in LL afferent terminals found that application of high concentrations of AMPA causes calcium influx into afferent terminals (Sebe et al., 2017). This calcium influx is followed by excitotoxic swelling and damage to the terminals. Blocking CP-AMPARs pharmacologically prevented these calcium increases and protected afferent terminals, suggesting that calcium is mechanistically involved in this pathology. However, it is not yet clear whether mitochondrial calcium influx contributes to this excitotoxicity. Future studies using established transgenic lines could be used to explore the role mitochondrial calcium plays in this pathological process.

Section 4: In vivo studies on mitochondrial metabolism in the lateral line

In order to effectively generate ATP, mitochondria must maintain a ΔΨm. ATP production also relies on other enzymes and cofactors for cellular metabolism such as NAD(H) (Stein and Imai, 2012). Imbalance in ΔΨm or the associated cofactors can be a sign of mitochondrial dysfunction and pathological conditions, including cell death (Esterberg et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2021). ATP production can come at a cost to the cell. During oxidative phosphorylation, protein complexes transfer electrons to pump protons and maintain the ΔΨm. Unfortunately, electrons can leak from these protein complexes, and reduce oxygen to form superoxide (Figure 2). Superoxide is commonly converted to hydrogen peroxide by enzymes in the mitochondria (superoxide dismutase (SOD) 1 and 2) (Wang et al., 2018). Both superoxide and hydrogen peroxide are reactive molecules and are considered mitochondrial ROS. A buildup of ROS can lead to the errant oxidation of membrane phospholipids, peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids, DNA oxidation, and protein carbonylation (Franco and Cidlowski, 2009; Sies et al., 2017).

In hair cell sensory systems, the balance between ATP production and ROS levels is important as both hair cells and primary afferents have a high demand for ATP. The critical requirement for mitochondria and ATP in hair cells and neurons is clear based on the loss of viability of these cells when mitochondrial function is impaired (Usami and Nishio, 1993). For example, abnormalities in mitochondrial DNA are associated with hair cell dysfunction and hearing loss in humans and animal models. Mitochondrial DNA mutations have been identified as the causative factor for 5% of post-lingual, non-syndromic sensorineural hearing loss in a European patient population (del Castillo et al., 2003; Jacobs et al., 2005; Wilch et al., 2010), and increase ototoxicity from aminoglycoside antibiotics (reviewed in: (Gao et al., 2017)). Additionally, loss of function mutations in the mitochondrial tRNA modifying enzyme Mitochondrial tRNA-specific 2-thioridylase 1 (MTU1) result in deficient oxidative phosphorylation and fewer hair cells, implicating mitochondrial health and function in hair cell survival (Zhang et al., 2018). Mitochondrial function is also tightly tied to drug and noise-induced hair cell death. After application of ototoxic drugs or noise exposure there are decreased measures of mitochondrial health and increased measures of ROS that precede cell death (Chen et al., 2015; Hirose et al., 1997). ROS also accumulate in hair cells with age and may play a role in age-related hearing loss (ARHL) (Fujimoto and Yamasoba, 2014).

ROS production and disrupted mitochondrial function are also pathological to spiral ganglion neurons (SGNs), the primary afferents in the mammalian auditory system. Work in mice has demonstrated that knockout of SOD1—an enzyme that converts superoxide radicals produced in the mitochondria into the less reactive hydrogen peroxide—leads to early onset of ARHL due to degeneration of SGNs (Keithley et al., 2005; McFadden et al., 1999). Similarly, disruptions in isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (IDH2), a critical participant in the TCA cycle that catalyzes the conversion of isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate and NADP+ to NADPH, results in increased oxidative DNA damage along with a concomitant acceleration of ARHL and profound loss of SGNs in mice (White et al., 2018). These studies have confirmed that a careful balance of mitochondrial function and ROS management is critical in both hair cells and afferent neurons.

The role of activity on cytotoxic stress in the lateral line

Hair cells require ATP to maintain a careful control of calcium levels for mechanotransduction (Beurg et al., 2010). ATP is also required to sustain membrane polarization and based on work in neurons, is likely essential for the maintenance of synaptic vesicle pools (Pulido and Ryan, 2021; Rangaraju et al., 2014). High levels of ATP production require consistent Δψm. Work in hair cells in the LL has examined how hair cell activity impacts mitochondrial function. These studies used genetics and pharmacology to explore how hair cell mechanotransduction and synaptic transmission impact Δψm in hair cells (Lukasz et al., 2022; Pickett et al., 2018). Using JC-1 and TMRE dye to assess Δψm, this work demonstrated that blocking mechanotransduction or synaptic transmission lowers Δψm levels compared to controls. These results suggest that both mechanotransduction and synaptic transmission normally increase Δψm levels, presumably due to the energy demanding nature of these processes. In future work, the GEIs PercevalHR and ATPSnFR could be used to link hair cell activity and ATP production more directly.

In addition, the impact hair cell activity has on hair cells as they age was examined in the LL. For this, mitoTIMER was used to explore how hair cells accumulate oxidated mitochondrial components as they age. This work found that as LL hair cells age, mitochondria become progressively more oxidized (Figure 5). Further, loss of mechanotransduction or synaptic transmission reduced levels of mitochondrial oxidation, as assayed by MitoSOX and CellROX vital dyes (Lukasz et al., 2022; Pickett et al., 2018). This indicates that hair cell activity is a major driver of mitochondrial oxidation. Further, work in LL hair cells also examined the relationship between mitochondrial oxidation, age, and susceptibility to insults. This work found that the older hair cells, with more accumulated mitochondrial oxidation (mitoTIMER), are more susceptible to aminoglycoside-induced cell death (Pickett et al., 2018). In addition, when hair cell activity is disrupted, they are less susceptible to aminoglycosides (Lukasz et al., 2022). Overall, these results indicate that the metabolic demands of hair cell activity led to the accumulation of ROS which can sensitize these cells to ototoxic insults, such as aminoglycoside antibiotics.

To link ROS more directly to cell death, Δψm and ROS have also been examined in hair cells under pathological conditions. Using the vital dyes TMRE, MitoSOX, and CellROX, work in the LL found that during application of ototoxic aminoglycosides (~20 mins) prior to hair cell death, TMRE fluorescence first rises dramatically then falls sharply, indicating Δψm hyperpolarization followed by Δψm collapse (Esterberg et al., 2016, 2013). This rise and fall in TMRE fluorescence are closely followed by an elevation in mitochondrial ROS and hair cell death (Esterberg et al., 2014).

In LL afferents, in vivo measurements of Δψm and ROS have not been monitored after disrupting afferent activity, during cell death, or during other pathological conditions. It would be interesting to monitor Δψm and ROS in mitochondria within the axon terminals of LL afferents during pathological processes such as excitotoxicity after application of glutamate receptor agonists such as AMPA.

Role of NAD(H) in lateral line synapse formation

Mitochondrial ATP production and Δψm maintenance relies on coenzymes including NAD(H), flavine adenine dinucleotide (FAD), and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP(H)) (Xiao et al., 2018). These coenzymes act in redox reactions and are oxidized and reduced by catabolic pathways in the cytosol and mitochondria. Of all the coenzymes required, NAD(H) is the main player in these pathways. NAD(H) exists as either NAD+ or NADH when it is oxidized or reduced respectively. Outside of these catabolic pathways, NAD(H) has additional functions in the cytosol. This includes the regulation of enzymes such as sirtuins and poly-ADP-ribose polymerases (PARPs) (Guarente, 2000; Pillai et al., 2005).

One additional function of NAD(H) in LL hair cells is regulating presynapse formation. Using the GEI Rex-YFP, Wong et al. identified a link between NAD+/NADH levels and presynapse size in developing LL hair cells (Wong et al., 2019). This function for NAD(H) relies on the NAD(H) binding site in the N-terminus of the structural protein, Ribeye, one of the primary components of the hair cell presynapse. This study demonstrated that elevation of mitochondrial calcium (see Section3) during development controls cytosolic NAD+/NADH levels. Blocking mitochondrial calcium uptake raises the NAD+/NADH ratio and increases presynapse size, linking these phenomena. Overall, these data indicate that during development, Ribeye interactions may be regulated by NAD+/NADH levels with higher NAD+ levels promoting presynapse assembly. A function for NAD(H) in synapse assembly and function on the post-synapse has not been investigated to date but is a clear question for future experiments.

In summary, work using GEIs and vital dyes has demonstrated the importance of maintaining mitochondrial health and function for the development, function and viability of the zebrafish LL sensory organ. These studies show that a careful balance of mitochondrial function is absolutely essential, not only for its role in ATP production but also for local regulation of calcium and NAD(H) levels which affect synapse assembly. Finally, when challenged with insults, cytotoxic ROS build up can lead to a loss of the sensory cells in this system. Therefore, there is a need for therapeutic options to control ROS and protect hair cells in these pathological situations.

Section 5: In vivo studies of mitochondrial transport in the lateral line

While we have at least a basic understanding of the functions of mitochondria in sensory systems, we are only beginning to understand how to keep mitochondrial populations healthy and properly localized to perform these functions. The metabolic activity and production of ROS, as discussed above, is damaging to the organelle and the cell. Therefore, regulated replenishment of healthy organelles is essential for the maintenance of afferent neurons and hair cells. In neurons, this replenishment is at least partially supported through the transport of healthy organelles to sites of high metabolic demand, such as the synapse. Evidence supports the removal of damaged mitochondria through transport as well and subsequent mitophagy, likely in the cell body. Therefore, at least in neurons, the maintenance of a healthy mitochondrial population requires active transport of these organelles (reviewed in: (Misgeld and Schwarz, 2017)).

While not much is known about mitochondrial motility in hair cells, mitochondrial transport in neurons has been a subject of intense investigation for several decades. This is largely due to the clear correlation between disrupted mitochondrial transport by microtubule motors and neurodegenerative diseases (Hirokawa et al., 2010; Sheng and Cai, 2012). Mitochondria undergo short- and long-range transport driven by actin- and microtubule-based motors respectively. Long distance mitochondrial transport is accomplished by microtubule-based motors in the kinesin and dynein families (Pilling et al., 2006). In axons, Kinesin motors drive anterograde mitochondrial transport from the neuronal cell body towards axon terminals. Cytoplasmic dynein 1 transports mitochondria in the opposite direction, towards the cell body. Short-range mitochondrial transport, particularly in dendritic spines, has been shown to depend on the actin cytoskeleton (Ligon and Steward, 2000; Sung et al., 2008). In the axon, however, inhibition of actin polymerization increases mitochondrial transport, suggesting that actin may also facilitate mitochondrial docking (Basu et al., 2021; Chada and Hollenbeck, 2004; Gutnick et al., 2019). The role of actin in the regulation of mitochondrial localization and transport in hair cells is currently unknown. Work has shown that the apical and synaptic regions of hair cells where mitochondria are concentrated are also actin rich (Guillet et al., 2016; Weaver et al., 1994). Given the roles attributed to mitochondria in hair cells, such as calcium uptake beneath the cuticular plate and at the presynapse (Beurg et al., 2010; Ikeda and Takasaka, 1993; Wong et al., 2019), the role of actin in mitochondrial transport is a topic of interest. Below we discuss the studies in the LL that have contributed to our understanding of the movement of mitochondrial populations in LL afferent neurons.

Importance of mitochondria transport on lateral line organelle health

Mitochondria transport is critical in long axonal processes such as the sensory axons of the LL. These axons are some of the longest in the fish, stretching from the pLLg, which is situated directly posterior to the ear, towards the tail (Figure 1A). An axon terminal can be several millimeters from the cell body in the LL. Similar to work in cultured mammalian neurons, mitochondria in LL axons actively move in the anterograde (toward the afferent terminal) or retrograde (toward the cell body) direction (Figure 4 and see (Drerup et al., 2017)). In the LL, mitochondrial-localized fluorescent proteins have been used to study the localization and transport of mitochondria within afferent neurons (e.g., Figure 1B, C, E, in the afferent soma, axons and terminals) (see Table 1, Section 1).

Figure 4.

Kymograph analysis reveal mitochondrial movement in lateral line axons.

(A-D) Mosaic expression of a mitochondrially targeted fluorescent protein (5kbneurod:mitoTagRFP) in a single pLL neuron enables imaging and tracking of mitochondrial movement within a region of an afferent axon (82 μm). The grayscale images in A-C are inverted such that a more intense fluorescent signal is darker. (A) The first frame of a 60 min movie taken of a single axon with mitoTagRFP label. Leftward is the somatic direction, rightward is towards the axon terminal. The axon is located between the two dotted lines. (B) Three representative time frames showing a mitochondrion moving in the anterograde direction (towards the axon terminal, red arrowheads). A stationary mitochondrion is shown with black arrowheads. For kymograph analysis, the axonal region is straightened and reduced to a one-dimensional line of signal intensity. (C) Kymograph of mitochondrial movement over time. In this kymograph, the intensity within the dotted region denoted in A is stacked at each subsequent frame of the 60 min time series – the vertical axis represents time. Vertical signals represent stationary mitochondria (e.g., black arrowhead in B), and slanted signals represent mitochondrial motility (e.g., red arrowhead, anterograde in B). (C’) Schematic of the kymograph showing representative anterograde (red lines) and retrograde movements (blue lines).

Although work in neurons indicates that inhibition of mitochondrial transport is detrimental to neuronal survival, little is known about why this is the case. To address the role of transport on mitochondrial homeostasis, mitochondrial transport was examined in LL afferent axons (Drerup and Nechiporuk, 2016; Mandal et al., 2018). For this work, LL mitochondria in single axons were labeled using mosaic expression of TagRFP targeted to mitochondria. By monitoring the movement of labeled mitochondria, this study identified a novel mutant (actr10) that specifically disrupts mitochondrial retrograde transport (cell body directed) in LL axons without affecting anterograde transport of mitochondria and transport of other cargos. Using vital dyes and GEIs, it was demonstrated that disruption of retrograde mitochondrial transport resulted in decreased Δψm (TMRE) and increased levels of accumulated ROS (mitoTIMER) in the mitochondria within LL afferent terminals (Mandal et al., 2020), suggesting mitochondrial damage. Though mitochondria in LL terminals of the actr10 mutant line displayed measures of failed health, no neurodegeneration or measurable functional deficit of LL afferents were observed. Future work on the resilience of LL afferent is warranted. Of particular interest would be longitudinal studies to determine if LL afferent terminals with mitochondria of failed health are hypersensitive to additional mitochondrial or excitotoxic insults. Together, these data implicate mitochondrial transport in the maintenance of a healthy mitochondrial population in LL afferent terminals.

Tracking mitochondrial docking and transport over time

Short-term mitochondrial tracking of mitochondrial axons in various systems (C. elegans, Drosophila, cultured mammalian neurons, etc.) has shown that 50–90% of mitochondria in axons are stationary over imaging periods from 5 to 30 minutes (Kang et al., 2008; Ligon and Steward, 2000; Overly et al., 1996; Schwarz, 2013). This finding is consistent with data from short-term mitochondrial imaging in zebrafish LL axons as well (Mandal et al., 2018). But how long these stationary mitochondria remain docked in place in neurons was not known. To assess the long-term movement and localization of mitochondria in the LL, the photoconvertible GEI mEos was used (Mandal et al., 2020, 2018). For this work, mEos-labeled mitochondria within the afferent terminal were photoconverted (convert from green to red fluorescence) and then tracked. By 24-hours after photoconversion, the majority of mitochondria leave the afferent terminal and have been replaced by new, unconverted (green) organelles (e.g., Figure 5). Additionally, this long-term imaging approach revealed that photoconverted mitochondria are not immediately degraded but are observed for the next several days in various areas of the neuron, including the cell body and proximal axon (Mandal et al., 2020). Together these long-term imaging studies reinforced the need to study mitochondria in vivo at a population level over varying time periods to better define the characteristics of their localization and movement in the compartmentalized neuronal environment.

Mitochondrial transport and docking have not been studied in detail in hair cells. It is thought that mitochondrial transport may not be as critical in hair cells as the organelle is restrained within a smaller cytosolic volume. In contrast, in neurons, mitochondria can be found a great distance from the cell body. Within hair cell, mitochondria are densely packed and form an interconnected network. This arrangement makes analyzing mitochondrial movement in hair cells technically challenging. However, the same general methodologies as used in LL axons could theoretically be used. Advances in light microscopy that provide higher Z-resolution while achieving a high frame rate, such as light-sheet microscopy, could be used to improve image resolution. Studies focused on mitochondrial transport and docking in hair cells would be of interest given the clear importance of mitochondria for hair cell viability and synapse formation and function (Esterberg et al., 2014; Pickett et al., 2018; Wong et al., 2019).

Together, imaging of mitochondria in vivo in afferent neurons has yielded novel insights into the lifetime, localization, and movement of these organelles. These approaches have contributed to and continue to define our understanding of mitochondrial physiology and maintenance, and how mitochondria influence cell survival.

Outlook and future work

Mitochondrial health, localization, and function are all critical for hair cells and primary afferents. Understanding how to maintain the health of these organelles within the complex compartments of sensory hair cells and afferent neurons will provide insight into the basic biology of mitochondria and the cellular pathology that underlies disease. To date, studies in mammals and zebrafish have provided valuable insight regarding the significance of this organelle in hair cell systems. To better understand mitochondrial pathology as it relates to cell survival and function, we need to understand additional aspects of mitochondrial biology in these cell types. For example, additional work is needed to explore mitochondrial fission/fusion dynamics and mitochondrial biogenesis, both during development and for the maintenance of mature cell types.

Mitochondrial fission and fusion

In addition to active mitochondrial transport, mitochondria undergo fission and fusion to divide and combine mitochondrial components. These mitochondrial dynamics are crucial for maintenance of organelle health and function. Disruption of mitochondrial fusion leads to mitochondrial fragmentation and neurodegeneration. Mutations in mitofusin 2, an essential mitochondrial fusion protein, cause the neurological Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2A (Züchner et al., 2004). Changes in mitofusin mRNA and protein levels have both been associated with Alzheimer’s disease (Manczak et al., 2011). Inhibition of mitochondrial fission has also been implicated in neurological and hair cell pathology. During aging, outer hair cell mitochondria dynamics, specifically fission, are thought to be decreased. This change leads to increased mitochondrial lengths and correlates with age-related hearing loss (Perkins et al., 2020). Changes in expression of fission associated proteins, such as the dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), correlate with Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease as well, implicating them in neuronal maintenance, though a causal link between Drp1 and disease in these cases has not been established (Oliver and Reddy, 2019).

While clearly critical for multiple mitochondria-related functions in cells, direct analyses of mitochondrial dynamics in neurons and hair cells are challenging. Due to the high density of mitochondria in these cell types, individual fission and fusion events are difficult to visualize in vivo, but multiple experimental approaches support the occurrence of these processes. Specifically, manipulation of essential fusion and fission proteins, including mitofusins and Drp1, causes expected alterations to mitochondria. For example, in the LL, expression of an active form of Drp1 in afferent neurons causes mitochondrial fragmentation in the cell body. With the continued advancement of light microscopy and the newly designed automated workflows which segment and quantify individual mitochondrion (Bosch and Calvo, 2019; Lihavainen et al., 2012; Ouellet et al., 2017) it will be possible to visualize mitochondrial dynamics related to fission and fusion in vivo in hair cells and neurons. The LL system, along with the in vivo tools outlined in this review, represents an ideal system to initiate this avenue of research. In the future, the LL system could be used to assess the frequency, location, compartmentalized function of fission and fusion.

Mitochondrial biogenesis and degradation

Equally important to maintaining the health of mitochondria already present in hair cells and primary afferents is the degradation of damaged organelles and the birth of new ones. Mitochondrial degradation, termed mitophagy, is an essential process in all cells. Disrupted mitophagy has been linked to several neurological disorders, specifically Parkinson’s disease (Clark et al., 2021). Indeed, mutations in key mitophagy proteins Pink1 and Parkin are causal in early onset Parkinson’s disease, which is caused by loss of neurons in the substantia nigra (Ge et al., 2020). There is also evidence linking mitophagy to hair cell function or survival. In auditory hair cells and SGNs in mice, loss of mitophagy is correlated with ARHL (Kim et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2019). Inhibition of mitophagy can induce hearing loss prematurely (Lin et al., 2019). Similarly, disruption of autophagy through ablation of Atg7, a core autophagy protein, in outer hair cells leads to ribbon synapse disruption, hair cell damage, and hearing loss in mice (Zhou et al., 2020). However, a direct link between mitochondrial degradation or disruption of this process and hair cell function and survival has not been thoroughly explored. Given the integral relationship between mitochondrial health and hair cell survival, this area deserves a thorough exploration.

A close companion to mitophagy is the birth of new mitochondria through mitochondrial biogenesis. Balanced degradation and biogenesis are essential for mitochondrial maintenance in all cell types. Mitochondrial biogenesis is a highly regulated and well-studied process. Because they have their own, albeit small, DNA (mtDNA), mitochondria cannot be synthesized de novo. Rather, seed organelles derived from mitochondrial fission are the likely building blocks of new organelles. To expand on these seeds, transcriptional programs have been identified that control the transcription of the >1500 mitochondrial proteins from nuclear DNA (Webb and Sideris, 2020). Specifically, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α) and its homolog PGC-1β have been shown to be master regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis. These transcriptional co-regulators facilitate the transcription of Nuclear respiratory factors 1 and 2 (Nrf1 and Nrf2). Nrf1/2 are transcription factors that promote the expression of mitochondrial transcription factor A (Tfam), which drives replication of mtDNA (reviewed in: (Jornayvaz and Shulman, 2010)). Increasing PGC-1α has been used in numerous studies to augment mitochondrial biogenesis in several cell types, including neurons, which has the potential to protect against neurodegeneration (Ciron et al., 2015; Rosenkranz et al., 2021). However, a direct examination of mitochondrial biogenesis upregulation after insults in hair cells has not been explored. A clear path forward would be to directly assay the basal rates of mitochondrial biogenesis in hair cells before and after injury. In addition, it will be important to assess whether augmenting biogenesis can protect hair cells after injury or insult. Tools such as mito-mEos could be used in the LL to study mitochondria biogenesis in hair cells after excitotoxic or pharmacological injury (Harris et al., 2003; Holmgren et al., 2021).

Similarly, the basal rate of mitochondrial biogenesis and location of this process in the highly compartmentalized environment of the afferent neuron has not been addressed. Studies in other neuronal subtypes have shown that indicators of mitochondrial biogenesis, such as mitochondrial DNA replication, are present in both the cell body and periphery of neurons (Amiri and Hollenbeck, 2008; Misgeld and Schwarz, 2017). To date, a conclusive understanding of the where, when, and how of mitochondrial biogenesis in neuronal compartments is lacking. By addressing the birth and death of this critical organelle in the sensory cells and afferent neurons of hair cell systems, we will obtain a better understanding of how to maintain these sensitive cell types.

Conclusion