The initiation of transcription is a complex process involving many different steps. These steps are all potential control points for regulating gene expression, and many have been exploited by bacteria to give rise to sophisticated regulatory mechanisms that allow the cell to adapt to changing growth regimens. Before they can transcribe from specific DNA promoter sequences, bacterial core RNA polymerases (with subunit composition α2ββ′) must combine with a dissociable sigma subunit (ς) to form RNA polymerase holoenzyme (α2ββ′ς). Since the discovery of ς factors (6), it has become clear that these proteins are central to the function of the RNA polymerase holoenzyme. The reversible binding of alternative ς factors allows formation of different holoenzymes able to distinguish groups of promoters required for different cellular functions. In addition to double-strand DNA promoter recognition and binding, ς proteins are closely involved in promoter melting (e.g., references 31, 36, 49, 51, 74, 76, 128), inhibit nonspecific initiation, are targets for activators, and control early transcription through promoter clearance and release from RNA polymerase (48, 49, 53). Here we describe the functioning of the bacterial ς54-RNA polymerase that is the target for sophisticated signal transduction pathways (103) involving activation via remote enhancer elements (5, 95).

Based on structural and functional criteria, the different ς factors identified in bacteria can be grouped in two classes, one of which has a single member, ς54. Many ς factors belong to the ς70 class, the major ς factor which is involved in expression of most genes during exponential growth (72). ς54 (also called ςN) differs both in amino acid sequence and in transcription mechanism from the ς70 class (80). Despite the lack of any significant sequence similarity, both types of ς bind the same core RNA polymerase. Nonetheless, they produce holoenzymes with different properties.

With the recognition that the ς54 protein represented an entirely new class of ς factor, what had once been regarded as an aspect of transcription restricted to higher organisms became a well-established feature of certain bacterial regulatory systems, particularly those associated with nitrogen metabolism. Activation of ς54-RNA polymerase employs specialized bacterial enhancer-binding proteins whose activating function requires nucleotide hydrolysis (94, 96, 122) (Fig. 1). In this system, initiation rates are controlled via regulation of the DNA melting step that is necessary for establishing the open promoter complex (85, 94, 97). Bacterial enhancer-dependent transcription can be studied with just two purified proteins (an activator and the ς54-RNA polymerase holoenzyme) and the appropriate DNA template, facilitating progress in understanding mechanistic aspects of ς54 functioning. Below we review the biology and biochemistry of the ς54-RNA polymerase.

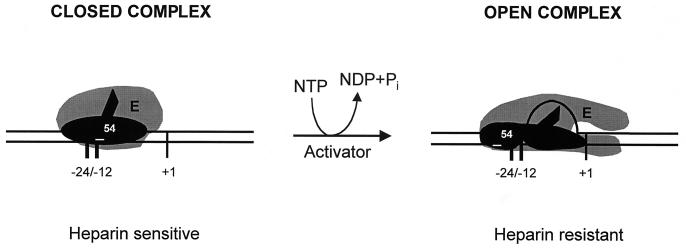

FIG. 1.

RNA polymerase holoenzyme containing ς54 binds to −24 and −12 consensus promoters to form a stable closed complex which is transcriptionally silent. This complex can be disrupted by heparin in vitro. Activator-mediated nucleotide hydrolysis drives full open promoter complex formation. Open complexes are insensitive to heparin in vitro. NTP, nucleoside triphosphate; NDP, nucleoside diphosphate.

OCCURRENCE AND FUNCTION OF ς54

Although ς54 was originally recognized in the enteric bacteria, it is now clear that ς54 is widely distributed among the bacteria. The role of ς54-RNA polymerase, historically in regulation of nitrogen metabolism and subsequently in many other biological activities, is well established in many proteobacteria (80). Genes encoding ς54 have also been cloned from the gram-positive Bacillus subtilis, where ς54 is involved in utilization of arginine and ornithine (43) and transport of fructose (29), and from Planctomyces limnophilus (68). Furthermore, genome sequencing projects have revealed open reading frames potentially encoding ς54 in diverse bacteria such as an extreme thermophile (30, 105), obligate intracellular pathogens (58, 102), spirochetes (37, 38), and green sulfur bacteria (104). However, complete genome sequences have also revealed the absence of ς54 in a diverse range of bacteria including the high-G+C gram-positive Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the extreme thermophile Thermotoga maritima, the specialized pathogens Rickettsia prowazekii, Mycoplasma genitalium, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae, the photosynthetic Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803, and Deinococcus radiodurans (for a recent review, see reference 104).

Most bacteria contain several alternative ς factors belonging to the ς70 class, but two forms of ς54 rarely coexist in the same organism. That is, no more than one ς54 gene is usually found, the exceptions so far being Bradyrhizobium japonicum, Rhodobacter sphaeroides, and Rhizobium etli which each contain two rpoN genes encoding two ς54 proteins (24, 65, 82). Nonetheless, ς54-RNA polymerase can be regulated independently at a wide variety of genes by virtue of a family of sequence-dependent enhancer proteins with promoter-specific binding sites (26). Each protein is controlled by its own signal transduction pathway, thus allowing a single ς54 polypeptide type to mediate transcriptional responses to a wide variety of physiological needs.

There is no obvious theme in the repertoire of functions carried out by the products of ς54-dependent transcription. Among the proteobacteria, these include utilization of various nitrogen and carbon sources, energy metabolism (70), RNA modification (44), chemotaxis, development, flagellation, electron transport, response to heat and phage shock (123), and expression of alternative ς factors (reviewed in references 1, 66, 80, and 104). It appears that ς54 is not usually essential for survival and growth under favorable conditions, except in Myxococcus xanthus (62).

The pattern of its occurrence in the bacterial domain argues for ς54 being biologically important and advantageous. Because initiation of transcription at a ς54-dependent promoter absolutely requires the activity of the cognate activator protein, transcription can be very tightly regulated, with low levels of leaky expression (118). Moreover, the use of ς54 may confer one notable advantage: the capacity to vary transcriptional efficiency at a given promoter over a wide range without the use of a separate repressor. Genes transcribed by this form of polymerase can be silent or highly expressed (when activated), depending on the physiological or environmental conditions. Given these advantages, why then are relatively few bacterial genes transcribed by ς54-RNA polymerase? The pathogenic Neisseria spp. seem to have abandoned the ς54-RNA polymerase mode of transcription recently, their genomes still containing rpoN pseudogenes which have apparently undergone a deletion of the DNA-binding region (67). Presumably the main disadvantage of the ς54-RNA polymerase mode of transcription is the requirement for significant stretches of intergenic DNA, and thus the need for larger chromosomes. The requirement for additional intergenic DNA arises from the DNA-looping mechanism of activator-RNA polymerase contact (5, 95). In order for cross talk between transcription units to be minimized, promoters would need to be well isolated from each other (73), as occurs in higher organisms where looping is common. In the case of nif genes in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Azotobacter vinelandii, their clustering could lead to promiscuous activation of one nif operon by the NifA bound to another nif operon's DNA. However, any cross activation would still be by the same signal transduction pathway, and might therefore be readily tolerated. Therefore, the same pressures that have led to the compactness characteristic of bacterial genomes may select against the increased use of ς54-RNA polymerase.

CONTROL CIRCUITRY

ς54-dependent activators bind to DNA sites at atypically long distances (for bacteria) from the start site for transcription, consistent with the looping mechanism of activation. This mechanism coexists with those regulating activity of the ς70-holoenzyme, for which activators bind adjacent to the polymerase site and touch the enzyme without looping (45). The ς54-holoenzyme forms a closed complex and occupies the promoter in this state prior to activation (97). This closed complex is unusually stable in the sense that it does not spontaneously isomerize into an open complex. Basal, unactivated transcription from the closed complex is intrinsically very low, consistent with the lack of repressors (see reference 26 but see reference 121 also) associated with ς54-dependent promoters. This stable closed complex is a convenient target for the looping of activators bound to remote sites (106). At some promoters, the looping-out of the intervening DNA is facilitated by the bending protein integration host factor (IHF) (54). This effect can be mimicked by HU or even the mammalian nonhistone chromatin protein HMG-1 and can be bypassed by intrinsically curved DNA (13, 15, 92, 93). IHF has been proposed to stimulate recruitment of ς54-polymerase at least one promoter (2). The outcome of looping is an activator-dependent isomerization of the closed complex into an open one, which leads to initiation of transcription. This mechanism is not observed for ς70-holoenzyme, where both highly stable closed complexes and looping are rarely, if ever, used directly for activation (46). In essence, ς54 binding to RNA polymerase imposes a block on the initiation pathway whereby open-complex formation (DNA melting) can be controlled independently from closed-complex formation (DNA binding).

The use of enhancers, nucleotide hydrolysis for melting (120), and chromosome structure modification by bending are more commonly found in cases of eukaryotic polymerase II transcription than with bacterial ς70-based transcription (reviewed in reference 64). Their involvement in bacterial ς54-dependent transcription indicates that ς54 is responsible for significantly modifying the properties of the RNA polymerase to endow enhancer responsiveness. In this sense ς54 converts the polymerase to an enhancer-requiring enzyme (115). The mechanisms used by eukaryotic enhancers are not limited to the melting control observed in bacteria. The need for compactness in bacterial genomes may preclude the greater diversity of mechanisms that occur in mammalian cells.

As is the case for ς70-holoenzyme, activation of ς54-RNA polymerase occurs by signal transduction pathways using numerous and diverse activators (reviewed in reference 101). Although these pathways are diverse, they have a common terminal mechanism. In each case, the output appears to involve the triggering of a hidden ATPase activity within an enhancer-binding activator protein. This ATPase is then used to overcome the block to DNA melting within the closed transcription complex and thereby allow transcription to initiate (122). When the physiological stimulus is removed, the activators no longer have their ATPase activities triggered and the cognate promoters revert to the inactive closed complex state. Many activators have their ATPase activities triggered by a phosphorylation cascade, as typified by the nitrogen regulator NtrC (124). Changing physiological conditions typically leads to phosphorylation of the protein's N terminus. Conformational changes then can lead to changes in activator affinity for enhancer DNA sites, multimerization on the DNA, and most important, assembly of a DNA-bound complex with ATPase activity (96). The ATPase activity is within the central domain of the activator, which may adopt a fold common to other purine nucleotide-binding and hydrolyzing proteins, and is predicted to show some structural similarity to members of the AAA+ protein family to which it belongs (87). Our understanding of NtrC is increasing with knowledge of its N- and C-terminal domain structures and how its activities are controlled by phosphorelay (61, 90, 91). Many other activators, e.g., NifA and PspF, do not rely on phosphorylation but instead react with small-molecule effectors or inhibitory polypeptides (e.g., references 32, 34, 101 and 129).

Additional physiological controls may be superimposed on the activator-dependent control of transcription from ς54-dependent promoters. For example, the pseudomonas putida Pu and Po promoters and the Rhizobium meliloti dct promoter are subject to catabolic repression by mechanisms which appear to be independent of signal transduction via the cognate activators (19–21, 33, 75, 83, 121). RNA polymerase holoenzyme at these promoters may also be regulated by a mechanism involving ppGpp (e.g., reference 110). Furthermore, the FtsH (HflB) protease is required for full ς54 activity in vivo at least at some promoters (14).

Although expression of ς54 is constitutive in many bacteria investigated (reviewed in reference 128), it is temporally regulated in Caulobacter crescentus (3) and Chlamydia trachomatis (77). Transcription of rpoN, encoding ς54, is probably subject to negative autoregulation in several bacteria including Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (35), Azotobacter vinelandii (79), B. japonicum (65), K. pneumoniae (47, 78), P. putida (63), and R. etli (82, 83).

The paradigm for enhancer-dependent transcription in eubacteria is characterized by interaction between ς54-RNA polymerase and an activator of the NtrC/NifA family. However, evidence is emerging that there may be more-complex assemblies of protein at some promoters controlled by ς54 that contribute to sophisticated regulatory responses. For example, cyclic AMP receptor protein mediates repression at the dctA promoter of Sinorhizobium meliloti (121).

A further example of complex control of ς54-dependent transcription may occur in B. subtilis where the AhrC protein represses arginine biosynthesis by binding to operator sites in the promoter regions of arginine biosynthetic genes (71, 84). An AhrC-binding site is located between the genes for glutamate dehydrogenase (rocG) and 1-pyrroline 5-carboxylate dehydrogenase (rocA), both of which may be under the control of ς54-RNA polymerase and the activator RocR (43). AhrC footprints a region directly adjacent to the rocA gene (nucleotides −22 to −2), suggesting the possibility of a regulatory interaction with ς54-RNA polymerase.

ς54 DOMAIN STRUCTURE, PROMOTER RECOGNITION, AND CORE INTERACTIONS

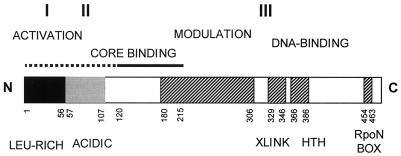

Sequence alignments, mutation analyses, and protein fragmentation studies have led to a picture of the overall domain structure of ς54, mainly using the proteins from enteric bacteria (11, 40, 79, 98, 127). ς54 was divided into three regions by sequence conservation (Fig. 2) (80). Primary DNA-binding functions (127) are in region III with a DNA cross-linking region (7) and associated motifs, the helix-turn-helix motif (81) and RpoN box (111) near the C terminus. Adjacent sequences modulate this activity (12) and others constitute the minimal core-binding domain (40, 113). Region II is variable and in some species, such as Rhodobacter capsulatus, is almost completely absent. In many (but not all) bacteria, region II is acidic, and it has been implicated in DNA melting (126), in the transition from the closed to open complex (E. Southern and M. Merrick, submitted for publication), and in assisting ς54 binding to homoduplex and heteroduplex DNA (8). The lack of conservation of region II suggests that none of its activities are essential. The amino-terminal 50 residues (region I) comprise a domain that performs two distinct functions: (i) inhibiting polymerase isomerization and initiation in the absence of activation (10, 109, 115) and (ii) stimulating initiation in response to activation (98, 109). It is now clear that there is considerable cross talk among these domains for the full function of ς54.

FIG. 2.

Domain organization of the ς54 protein. E. coli ς54 (amino acids 1 to 477) can be divided into three regions (I to III [80]). DNA-binding functions (127) and associated motifs (DNA cross-linking [XLINK] region [7], helix-turn-helix [HTH] motif [81], and RpoN box [111]) reside in the C terminus, adjacent to sequences that modulate DNA binding (amino acids 180 to 306) (12). Activator responsiveness involves region I sequences (10, 98, 109), and region II is acid and variable. The main core binding determinant from amino acids 120 to 215 (40, 127) is shown. A full ς54 amino acid alignment of known sequences is available at http://www.bio.ic.ac.uk/staff/mbuck/alignment.rtf.

DNA binding.

The primary DNA-binding activity for recognition of double-stranded promoter DNA resides in a C-terminal domain (7, 50, 81, 98, 111, 127). Mutations within this region eliminate such binding. Unlike ς70, the DNA-binding activity of ς54 is not fully masked and ς54 is able to bind to certain promoters in the absence of core polymerase (4). Nonetheless, holoenzyme binds tighter than does ς54 alone. Two other regions can affect the affinity of binding: the N terminus plays complex multiple roles in binding to both duplex and melted DNA (10, 17, 41, 52, 59, 60, 98, 117), and the segment between the C terminus and the major core-binding determinant influences binding affinity (12, 50). These regions do not necessarily make direct DNA contact.

The ς54 promoter recognition sequence includes short elements at nucleotides −12 and −24 (85) with extensive conservation in between these two (1, 118). Mutant analyses suggest that the −24 element makes the greater contribution to binding, an argument based on the ability of mutant complexes to retain −24 contacts while losing −12 region contacts; no complex has been found that retains only −12 region contacts (55, 127). Remarkably, the subdomains that recognize these elements are not yet definitively identified. Recognition of the −12 sequence appears to be very complex (41, 55, 81, 86, 98, 118, 119, 127). It was initially proposed to involve a C-terminal potential helix-turn-helix motif (27, 81) and the N terminus (98). It is likely that −12 recognition is accomplished by a structure contributed by more than one region of the protein (22; L. Wang and J. D. Gralla, unpublished data). The −24 recognition is presumed to occur via the C terminus (50, 98, 127), although direct evidence is still lacking. The highly conserved RpoN box (111) is a candidate for this interaction.

There is considerable variation in the DNA sequences of ς54-dependent promoters; as is the case for ς70 promoters, virtually all sequences deviate from the consensus sequence (1). The artificial introduction of consensus nucleotides generally increases binding, but transcription is not increased in all cases (25). Some sequence changes lead to detectable levels of leaky transcription, apparently through defects in the use of the −12 element (118, 119). It appears that a balance must be struck between promoter occupancy, transcription levels, and prevention of unregulated transcription. The affinity of the closed complex can be high enough so that promoters are occupied in vivo prior to activation. The number of ς54 molecules in Escherichia coli cells is close to 100 (compared to 600 to 700 of ς70 [57]) which is greater than the number of promoters (less than 20 in the E. coli genome). Thus, even low-affinity promoters may be significantly occupied prior to activation. This seems likely given the apparent lack of promoter recruitment of the ς54-RNA polymerase holoenzyme by its activators (95, 121).

Core polymerase binding.

The interface between ς54 and core RNA polymerase is probably very extensive. Mutations in the central region of ς54 eliminate binding to core (56, 112, 113, 127). Additional contributions come from the C-terminal DNA-binding domain and N-terminal region I (16, 17, 40). Although ς54 is not related to ς70 by primary sequence, it binds to the same core polymerase, likely with similar affinity (40, 99). However, there is a short region of potential similarity in the central domain (112) and small-angle X-ray-scattering studies suggest that the core-binding domains of ς54 and ς70 have similar shapes (107). Results with tethered iron chelate methodology have suggested related binding arrangements (125). The core-binding interface of ς70 also involves widely separated regions of that protein (100), yet another point of similarity between ς54 and ς70. ς70 has determinants of interaction with the core and with the DNA in close proximity. The N terminus of ς54 also has these properties, which may reflect a coordinated behavior of domains during transcription initiation.

Indeed, the ς54-core interface appears to change during the transcription cycle. After initial binding, there is a slow conformational change in the holoenzyme, suggestive of a stabilization of ς54-core interactions (99). In initiated complexes, the N-terminal region I conformation appears to have changed with respect to closed complexes (16). This region is central to the control of DNA melting (127). The interaction of region I with core likely contributes some of the specialized properties of the holoenzyme, including its ability to be controlled at the DNA melting step (9, 10, 40, 41).

Some sequences in the DNA-binding domain of ς54 appear to be required for the activator-independent heparin stability of the holoenzyme on early melted DNA, suggesting that they contribute to the interface of ς54 that interacts with core (88, 89; M. Pitt and M. Buck, unpublished data). The functioning of this interface may be important during the early stages of DNA opening. The existence of the interface was suggested by protein footprint experiments (16, 17).

MECHANISM OF PROMOTER ACTIVATION

The key activation event is the opening of the DNA within the closed complex of ς54 holoenzyme at the promoter. This is accomplished using the ATPase activity of the activator, which loops from the enhancer site (96). The interactions between activator and the ς54-RNA polymerase holoenzyme appear to be transient, and the only direct physical evidence has been by a cross-linking assay using the DctD activator (60, 69).

As activators of the ς54-holoenzyme are related to the purine nucleotide-binding and hydrolyzing proteins, they would be expected to use the ATPase to bring about conformational changes. It is not known how the proposed energy coupling impacts upon the holoenzyme to cause it to open the DNA. Sequence analysis of activators does not reveal obvious similarity to known helicases (96, 122).

Clues from deregulated transcription.

One view of the activation process is that ς54 organizes the holoenzyme so that it cannot fully melt DNA; the activator then overcomes this block. In this view, mutants that allow unregulated melting provide valuable clues to the mechanism of activation (115). Such mutants have been found in both the ς54 protein and in the DNA sequence of the promoter.

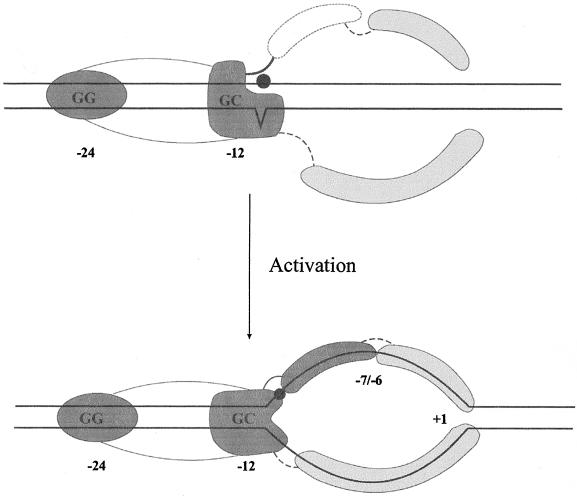

Deregulated ς54 mutants, allowing activator-independent transcription, map predominantly in the N-terminal region I and in a very limited set of sites within the C-terminal DNA-binding domain (18, 22, 108, 109, 115–117; Wang and Gralla, unpublished). Mutant promoters that allow activator independent transcription have in common a substitution for the consensus C at nucleotide −12 (118, 119). These locations and other data concerning −12 region recognition have led to the idea that there may be a complex molecular structure, involving the protein's N and C termini and the promoter −12 region, that keeps the DNA firmly closed (Fig. 3) (9, 22, 41, 52, 60; Y. Guo, C. M. Lew, and J. D. Gralla, submitted for publication).

FIG. 3.

Cartoon model showing activities proposed for activation via DNA melting. Dark shading indicates activities primarily in ς54. These activities include duplex (double-stranded DNA) binding at nucleotides −24 and −12 and fork junction binding. The −7 to −11 single-strand binding activity is seen only after activation. Light shading indicates single-strand binding activities contributed by RNA polymerase holoenzyme. The solid circle represents the −11 connector nucleotide that inhibits the spread of unactivated melting when unpaired. (Top) Prior to activation, the holoenzyme is stabilized on the DNA using primary interactions at nucleotide −24. The unactivated complex includes a form shown here in which a molecular structure near −12 contributes to binding and prevents the spread of early DNA melting to downstream positions. The N terminus and the fork junction connector position −11 (solid circle) are key determinants in locking the system in a closed state. Deregulated bypass mutations destroy this ς54-DNA structure at −11 and allow partial engagement of the downstream single-strand binding activities; these are shown downstream of −12 and above and below the DNA in an unengaged state. (Bottom) Upon activation, ATP triggers conformational changes in ς54 at the fork junction that involve the ς54 N terminus. The upstream nontemplate strand binding activity is exposed, and interactions through the connector can now be established. The single-strand DNA-binding activities stabilize the spread of melting.

In order to understand how DNA melting originates and propagates, various studies have used DNA probes that attempt to mimic intermediates along the melting pathway. Initial studies showed that transcription of preopened promoter DNA heteroduplexes did not bypass the activator requirement (10, 122). This suggests that conformational changes in the protein must be required in addition to those in the DNA (10). More-recent studies confirmed this but showed that heteroduplexes that keep nontemplate position −11 firmly double stranded could be transcribed without activator (Guo, Lew, and Gralla, submitted). Certain DNA probes that mimic the critically important upstream −11 fork junction of the transcription bubble (51) bind both isolated ς54 and holoenzyme exceptionally tightly, using the template strand of the fork (9, 41, 52; W. Cannon and M. Buck, unpublished data). This binding is also inhibited by exposure of the nontemplate position −11 (52). These observations suggest that interactions near −11 are critical, perhaps in controlling the required conformational changes in the holoenzyme (Fig. 3) (Guo, Lew, and Gralla, submitted).

Deregulated ς54 mutants lose tight DNA binding to a variety of fork and heteroduplex probes (9, 41, 52, 59, 60; M. Chaney and M. Buck, unpublished data), particularly when the fork junction is at −11 (52). This is true whether the deregulation mutation is in the N or C terminus of ς54 or in the −12 region of the promoter. Deregulated mutants gain the ability to bind more tightly to downstream structures containing melted DNA (10, 18, 52, 119; Wang and Gralla, unpublished). Thus, one aspect of regulation is to prevent this. In closed complexes, ς54 contributes to the maintenance of a very local DNA distortion that has all the signatures of local DNA opening and with which a fork junction structure must be associated. If base pair −11 is transiently melted by wild-type holoenzyme (Fig. 3), a tight fork junction complex would be created along the template strand. This would not propagate melting due to the exposure of the inhibitory nontemplate (52; Guo, Lew, and Gralla, submitted). Thus, inappropriate downstream opening would be prevented.

The nature of the interaction at this upstream fork junction changes during activation, as indicated by altered sensitivity of the DNA to chemical probes and altered patterns of protein-DNA cross-linking, suggesting that the activator overcomes this inhibition of melting (9, 11, 85, 86, 94; Guo, Lew, and Gralla, submitted). The N terminus is centrally involved in these changes as suggested by the results of experiments with a ς54 in which this region had been deleted (10, 42, 52, 127). Activator can no longer function, confirming that region I has a positive role in activation (109, 117). With this mutant, one can supply the missing region in trans and restore tight binding to heteroduplex probes (9, 10, 42). Thus, one view is that the N-terminal region I is part of a molecular switch (52) that helps keep melting in check within closed complexes but upon activation switches its interactions to a new set that contributes to open-complex formation (Fig. 3) (9, 10, 41, 42; Guo, Lew, and Gralla, submitted).

Role of the ς54 polypeptide.

Various results underscore the pivotal role of ς54 in activation and DNA melting by holoenzyme and suggest that it may be the primary target of the activator. ς54 has the specificity that recognizes the DNA at the upstream fork junction (52). ς54 bound to heteroduplex DNA probes containing such junctions changes conformation independently of core polymerase in a reaction that requires activator and nucleotide hydrolysis (9). In the isomerized complex, ς54 interactions give an extended DNase I footprint that approaches the start site and some DNA melting occurs over this region, (W. Cannon, M.-T. Gallegos, and M. Buck, unpublished data). These considerations indicate that conformational changes in ς54 itself are likely to be very early events triggered by activators.

These activator-driven conformational changes in ς54 are associated with conformational changes in the holoenzyme. The DNA cross-linking pattern of ς54 in holoenzyme is altered upon activation, and this and other changes occur specifically at the upstream fork junction (Guo, Lew, and Gralla, submitted). The new cross-link requires activator and ATP and establishes interactions with the melted nontemplate strand segment adjacent to the upstream fork junction. Related changes have been detected during melting by ς70-holoenzyme, which also has an inhibitory nucleotide (Fig. 3) separating the fork junction and nontemplate strand interactions (51; Guo, Lew, and Gralla, submitted). The emerging view is that the two melting pathways (ς70 and ς54) may be similar with the fundamental distinction that ς54 organizes the holoenzyme so that its conformational changes are firmly prevented in the absence of activator. The N-terminal region I of ς54 plays a key role in this process.

Bacterial promoter melting relies on activities that engage the single-stranded DNA within the open complex (51, 52, 76; Guo, Lew, and Gralla, submitted). Although region I controls melting, the activities likely lie in several parts of ς54 and probably in core as well. Both ς54 and ς70-holoenzymes have activities that bind upstream fork junctions and activities that bind the single-stranded DNA (51, 52). In the case of ς70-holoenzyme, a series of two conformational changes occurs that allows these activities to work together to fully engage the melted DNA (Guo, Lew, and Gralla, submitted). In ς54-holoenzyme, the engagement of the downstream single-stranded DNA can lead to transient transcription in vitro but this is promiscuous, as evidenced by its sensitivity to heparin (10, 114, 116, 117). One view is that ς54 organizes the holoenzyme into a closed form that cannot engage the full DNA bubble from upstream fork to start site, which would need to propagate through the −11 inhibitory nucleotide. The N-terminal region I would have central involvement in keeping the enzyme closed and in responding to activator to change conformation to open the enzyme and hence the DNA (9, 10; Guo, Lew, and Gralla, submitted; Cannon, Gallegos, and Buck, unpublished data).

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Remaining problems include determining the precise sites of contact for activators in ς54-holoenzyme, working out how the activator uses ATP to achieve conformational changes, and determining what these conformational changes are and how they are used. Some answers will depend upon structural information and biophysical approaches. Genetic methods still continue to be a way forward (e.g., reference 47). We note that the ς54 transcription mechanism complements the common bacterial mechanism with a dependence on enhancers and ATP hydrolysis for initiation that is like mammalian RNA polymerase II. In a sense, this bacterial arrangement mimics the specialization in eukaryotes where different polymerases have differing dependencies on enhancers and ATP hydrolysis. It will be a challenge to work out the advantages of each type of mechanism and place them together in evolutionary context.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Work in M.B.'s laboratory was supported by research grants from the European Union, Wellcome Trust, and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council. M.-T.G. received a Marie Curie TMR fellowship. Work in J.D.G.'s laboratory was supported by USPHS grant GM 35754.

We thank T. Hoover, V. de Lorenzo, M. Merrick, and B. T. Nixon for communicating unpublished data. We are grateful to R. Dixon, B. Magasanik, and M. Merrick for constructive criticism and valuable comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrios H, Valderrama B, Morett E. Compilation and analysis of ς54-dependent promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4305–4313. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.22.4305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertoni G, Fujita N, Ishihama A, de Lorenzo V. Active recruitment of ς54 RNA polymerase to the Pu promoter of Pseudomonas putida: role of IHF and αCTD. EMBO J. 1998;17:5120–5128. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.17.5120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brun Y V, Shapiro L. A temporally controlled sigma-factor is required for polar morphogenesis and normal cell division in Caulobacter. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2395–2408. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12a.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buck M, Cannon W. Specific binding of the transcription factor sigma-54 to promoter DNA. Nature. 1992;358:422–424. doi: 10.1038/358422a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buck M, Miller S, Drummond M, Dixon R. Upstream activator sequences are present in the promoters of nitrogen-fixation genes. Nature. 1986;320:374–378. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgess R R, Travers A A, Dunn J J, Bautz E K. Factor stimulating transcription by RNA polymerase. Nature. 1969;221:43–46. doi: 10.1038/221043a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cannon W, Claverie-Martin F, Austin S, Buck M. Identification of a DNA-contacting surface in the transcription factor sigma-54. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:227–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannon W, Chaney M, Buck M. Characterisation of holoenzyme lacking ςN regions I and II. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2478–2486. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.12.2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cannon, W., M. T. Gallegos, and M. Buck. Isomerisation of a binary sigma-promoter DNA complex by enhancer binding transcription activators. Nat. Struct. Biol. in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Cannon W, Gallegos M T, Casaz P, Buck M. Amino-terminal sequences of ς54 (ςN) inhibit RNA polymerase isomerization. Genes Dev. 1999;13:357–370. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cannon W, Missailidis S, Smith C, Cottier A, Austin S, Moore M, Buck M. Core RNA polymerase and promoter DNA interactions of purified domains of ςN: bipartite functions. J Mol Biol. 1995;248:781–803. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cannon W V, Chaney M K, Wang X, Buck M. Two domains within ςN (ς54) cooperate for DNA binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5006–5011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carmona M, Magasanik B. Activation of transcription at sigma 54-dependent promoters on linear templates requires intrinsic or induced bending of the DNA. J Mol Biol. 1996;261:348–356. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carmona M, de Lorenzo V. Involvement of the FtsH (HflB) protease in the activity of ς54 promoters. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:261–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carmona M, Claverie-Martin F, Magasanik B. DNA bending and the initiation of transcription at sigma54-dependent bacterial promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9568–9572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casaz P, Buck M. Probing the assembly of transcription initiation complexes through changes in ςN protease sensitivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12145–12150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casaz P, Buck M. Region I modifies DNA-binding domain conformation of ςN within the holoenzyme. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:507–514. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casaz P, Gallegos M T, Buck M. Systematic analysis of ς54 N-terminal sequences identifies regions involved in positive and negative regulation of transcription. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:229–239. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casés I, Pérez-Martin J, de Lorenzo V. The IIA(Ntr) (PtsN) protein of Pseudomonas putida mediates the C source inhibition of the ς54-dependent Pu promoter of the TOL plasmid. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15562–15568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casés I, de Lorenzo V, Pérez-Martin J. Involvement of sigma(54) in exponential silencing of the Pseudomonas putida TOL plasmid Pu promoter. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:7–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.345873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casés I, de Lorenzo V. Genetic evidence of distinct physiological regulation mechanisms in the ς54 Pu promoter of Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:956–960. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.4.956-960.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaney M, Buck M. The ς54 DNA-binding domain includes a determinant of enhancer responsiveness. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:1200–1209. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaney, M., M. Pitt, and M. Buck. Sequences within the DNA-crosslinking patch of sigma54 involved in promoter recognition, sigma isomerisation and open complex formation. J. Biol. Chem. in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Choudhary M, Mackenzie C, Mouncey N J, Kaplan S. RsGDB, the Rhodobacter sphaeroides Genome Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:61–62. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Claverie-Martín F, Magasanik B. Positive and negative effects of DNA bending on activation of transcription from a distant site. J Mol Biol. 1992;227:996–1008. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90516-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collado-Vides J, Magasanik B, Gralla J D. Control site location and transcriptional regulation in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:371–394. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.3.371-394.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coppard J R, Merrick M J. Cassette mutagenesis implicates a helix-turn-helix motif in promoter recognition by the novel RNA polymerase sigma factor sigma 54. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1309–1317. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cullen P J, Foster-Hartnett D, Gabbert K K, Kranz R G. Structure and expression of the alternative sigma factor, RpoN, in Rhodobacter capsulatus: physiological relevance of an autoactivated nifU2-rpoN superoperon. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:51–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Debarbouille M, Martin-Verstraete I, Kunst F, Rapoport G. The Bacillus subtilis sigL gene encodes an equivalent of ς54 from gram-negative bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9092–9096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.9092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deckert G, Warren P V, Gaasterland T, Young W G, Lenox A L, Graham D E, Overbeek R, Snead M A, Keller M, Aujay M, Huber R, Feldman R A, Short J M, Olsen G J, Swanson R V. The complete genome of the hyperthermophilic bacterium Aquifex aeolicus. Nature. 1998;392:353–358. doi: 10.1038/32831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeHaseth P I, Helmann J D. Open complex-formation by Escherichia coli RNA-polymerase—the mechanism of polymerase-induced strand separation of double-helical DNA. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:817–824. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dixon R. The oxygen-responsive NIFL-NIFA complex: a novel two-component regulatory system controlling nitrogenase synthesis in gamma-proteobacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1998;169:371–380. doi: 10.1007/s002030050585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duetz W A, Marqués S, Wind B, Ramos J L, van Andel J G. Catabolite repression of the toluene degradation pathway in Pseudomonas putida harboring pWWO under various conditions of nutrient limitation in chemostat culture. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:601–606. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.601-606.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dworkin J, Jovanovic G, Model P. The PspA protein of Escherichia coli is a negative regulator of ς54-dependent transcription. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:311–319. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.2.311-319.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ehrt S, Ornston L N, Hillen W. RpoN (ς54) is required for conversion of phenol to catechol in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3493–3499. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.12.3493-3499.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fenton M, Lee S J, Gralla J D. E. coli promoter opening and −10 recognition: mutational analysis of sigma 70. EMBO J. 2000;19:1130–1137. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.5.1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fraser C M, Casjens S, Huang W M, Sutton G G, Clayton R, Lathigra R, White O, Ketchum K A, Dodson R, Hickey E K, Gwinn M, Dougherty B, Tomb J F, Fleischmann R D, Richardson D, Peterson J, Kerlavage A R, Quackenbush J, Salzberg S, Hanson M, van Vugt R, Palmer N, Adams M D, Gocayne J C, Weidman J, Utterback T, Watthey L, McDonald L, Artiach P, Bowman C, Garland S, Fujii C, Cotton M D, Horst K, Roberts K, Hatch B, Smith H O, Venter J C. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–586. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fraser C M, Norris S J, Weinstock G M, White O, Sutton G G, Dodson R, Gwinn M, Hickey E K, Clayton R, Ketchum K A, Sodergren E, Hardham J M, McLeod M P, Salzberg S, Peterson J, Khalak H, Richardson D, Howell J K, Chidambaram M, Utterback T, McDonald L, Artiach P, Bowman C, Cotton M D, Fujii C, Garland S, Hatch B, Horst K, Roberts K, Sandusky M, Weidman J, Smith H O, Venter J C. Complete genome sequence of Treponema pallidum, the syphilis spirochete. Science. 1998;281:375–388. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5375.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fredrick K L, Helmann J D. Dual chemotaxis signaling pathways in Bacillus subtilis: ςD-dependent gene encodes a novel protein with both CheW and CheY homologous domains. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2727–2735. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.9.2727-2735.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gallegos M T, Buck M. Sequences in ς54 determining holoenzyme formation and properties. J Mol Biol. 1999;288:539–553. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gallegos M T, Buck M. Sequences in ς54 Region I required for binding to early melted DNA and their involvement in sigma-DNA isomerisation. J Mol Biol. 2000;297:849–859. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gallegos M T, Cannon W, Buck M. Functions of the ς54 Region I in trans and implications for transcription activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25285–25290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gardan R, Rapoport G, Debarbouille M. Role of the transcriptional activator RocR in the arginine-degradation pathway of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:825–837. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3881754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Genschik P, Drabikowski K, Filipowicz W. Characterization of the Escherichia coli RNA 3′-terminal phosphate cyclase and its ς54-regulated operon. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25516–25526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.39.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gralla J D. Transcriptional control—lessons from an E. coli promoter database. Cell. 1991;66:415–418. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gralla J D. Activation and repression of E. coli promoters. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;16:1614–1621. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grande R A, Valderrama B, Morett E. Suppression analysis of positive control mutants of NifA reveals two overlapping promoters for Klebsiella pneumoniae rpoN. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:291–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gribskov M, Burgess R R. Sigma factors from E. coli, B. subtilis, phage SP01, and phage T4 are homologous proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:6745–6763. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.16.6745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gross C A, Chan C, Dombroski A, Gruber T, Sharp M, Tupy J, Young B. The functional and regulatory roles of sigma factors in transcription. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1998;63:141–155. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guo Y, Gralla J D. DNA-binding determinants of ς54 as deduced from libraries of mutations. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1239–1245. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.1239-1245.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo Y, Gralla J D. Promoter opening via a DNA fork junction binding activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11655–11660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guo Y, Wang L, Gralla J D. A fork junction DNA-protein switch that controls promoter melting by the bacterial enhancer-dependent sigma factor. EMBO J. 1999;18:3736–3745. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.13.3736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Helmann J D, Chamberlin M J. Structure and function of bacterial sigma factors. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:839–872. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.004203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoover T R, Santero E, Porter S, Kustu S. The integration host factor stimulates interaction of RNA polymerase with NIFA, the transcriptional activator for nitrogen fixation operons. Cell. 1990;63:11–22. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90284-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hsieh M, Gralla J D. Analysis of the N-terminal leucine heptad and hexad repeats of sigma 54. J Mol Biol. 1994;239:15–24. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hsieh M, Hsu H M, Hwang S F, Wen F C, Yu J S, Wen C C, Li C. The hydrophobic heptad repeat in Region III of Escherichia coli transcription factor ς54 is essential for core RNA polymerase binding. Microbiology. 1999;145:3081–3088. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-11-3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jishage M, Iwata A, Ueda S, Ishihama A. Regulation of RNA polymerase sigma subunit levels in Escherichia coli: intracellular levels of four species of sigma subunits under various growth conditions. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5447–5451. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.18.5447-5451.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kalman S, Mitchell W, Marathe R, Lammel C, Fan J, Hyman R W, Olinger L, Grimwood J, Davis R W, Stephens R S. Comparative genomes of Chlamydia pneumoniae and C. trachomatis. Nat Genet. 1999;21:385–389. doi: 10.1038/7716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kelly M T, Hoover T R. Mutant forms of Salmonella typhimurium ς54 defective in transcription initiation but not promoter binding activity. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3351–3357. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.11.3351-3357.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kelly M T, Hoover T R. The amino terminus of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium ς54 is required for interactions with an enhancer-binding protein and binding to fork junction DNA. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:513–517. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.2.513-517.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kern D, Volkman B F, Luginbühl P, Nohaile M J, Kustu S, Wemmer D E. Structure of a transiently phosphorylated switch in bacterial signal transduction. Nature. 1999;402:894–898. doi: 10.1038/47273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Keseler I M, Kaiser D. ς54, a vital protein for Myxococcus xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1979–1984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kohler T, Alvarez J F, Harayama S. Regulation of the rpoN, ORF102 and ORF154 genes in Pseudomonas putida. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;115:177–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kornberg R D. Mechanism and regulation of yeast RNA polymerase II transcription. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1998;63:229–232. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kullik I, Fritsche S, Knobel H, Sanjuan J, Hennecke H, Fischer H M. Bradyrhizobium japonicum has two differentially regulated, functional homologs of the ς54 gene (rpoN) J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1125–1138. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.3.1125-1138.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kustu S, Santero E, Keener J, Popham D, Weiss D. Expression of ς54 (ntrA)-dependent genes is probably united by a common mechanism. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:367–376. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.3.367-376.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Laskos L, Dillard J P, Seifert H S, Fyfe J A M, Davies J K. The pathogenic neisseriae contain an inactive rpoN gene and do not utilize the pilE ς54 promoter. Gene. 1998;208:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00664-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leary B A, Ward-Rainey N, Hoover T R. Cloning and characterization of Planctomyces limnophilus rpoN: complementation of a Salmonella typhimurium rpoN mutant strain. Gene. 1998;221:151–157. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee J H, Hoover T R. Protein cross-linking studies suggest that Rhizobium meliloti C-4-dicarboxylic acid transport protein-D, a ς54-dependent transcriptional activator, interacts with ς54-subunit and the beta-subunit of RNA-polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9702–9706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lenz O, Strack A, Tran-Betcke A, Friedrich B. A hydrogen-sensing system in transcriptional regulation of hydrogenase gene expression in Alcaligenes species. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1655–1663. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1655-1663.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lingel U, Miller C M, North A K, Stockley P G, Baumberg S. A binding site for activation by the Bacillus subtilis AhrC protein, a repressor/activator of arginine metabolism. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;248:329–340. doi: 10.1007/BF02191600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lonetto M, Gribskov M, Gross C A. The ς70 family: sequence conservation and evolutionary relationships. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3843–3849. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.3843-3849.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Magasanik B. Gene regulation from sites near and far. New Biol. 1989;1:247–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Malhotra A, Severinova E, Darst S A. Crystal structure of a ς70 subunit fragment from E. coli RNA polymerase. Cell. 1990;87:127–136. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81329-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Marqués S, Holtel A, Timmis K N, Ramos J L. Transcriptional induction kinetics from the promoters of the catabolic pathways of TOL plasmid pWW0 of Pseudomonas putida for metabolism of aromatics. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2517–2524. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.9.2517-2524.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marr M T, Roberts J W. Promoter recognition as measured by binding of polymerase to nontemplate strand oligonucleotide. Science. 1997;276:1258–1260. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5316.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mathews S A, Volp K M, Timms P. Development of a quantitative gene expression assay for Chlamydia trachomatis identified temporal expression of sigma factors. FEBS Lett. 1999;458:354–358. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Merrick M J, Gibbins J R. The nucleotide sequence of the nitrogen-regulation gene ntrA of Klebsiella pneumoniae and comparison with conserved features in bacteril RNA polymerase sigma factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:7607–7620. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.21.7607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Merrick M, Gibbins J, Toukdarian A. The nucleotide sequence of the sigma factor gene ntrA (rpoN) of Azotobacter vinelandii: analysis of conserved sequences in NtrA proteins. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;210:323–330. doi: 10.1007/BF00325701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Merrick M J. In a class of its own—the RNA polymerase sigma factor ςN (ς54) Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:903–909. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Merrick M J, Chambers S. The helix-turn-helix motif of ς54 is involved in recognition of the −13 promoter region. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7221–7226. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.22.7221-7226.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Michiels J, Moris M, Dombrecht B, Verreth C, Vanderleyden J. Differential regulation of Rhizobium etli rpoN2 gene expression during symbiosis and free-living growth. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3620–3628. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3620-3628.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Michiels J, Van Soom T, D'hooghe I, Dombrecht B, Benhassine T, de Wilde P, Vanderleyden J. The Rhizobium etli rpoN locus: DNA sequence analysis and phenotypical characterization of rpoN, ptsN, and ptsA mutants. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1729–1740. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.7.1729-1740.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Miller C M, Baumberg S, Stockley P G. Operator interactions by the Bacillus subtilis arginine repressor/activator, AhrC: novel positioning and DNA-mediated assembly of a transcriptional activator at catabolic sites. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:37–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5441907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Morett E, Buck M. In vivo studies on the interaction of RNA polymerase-ς54 with the Klebsiella pneumoniae and Rhizobium meliloti nifH promoters. J Mol Biol. 1989;210:65–77. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90291-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Morris L, Cannon W, Claverie-Martin F, Austin S, Buck M. DNA distortion and nucleation of local DNA unwinding within ς54 (ςN) holoenzyme closed promoter complexes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11563–11571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Neuwald A F, Aravind L, Spouge J L, Koonin E V. AAA+: a class of chaperone-like ATPases associated with the assembly, operation, and disassembly of protein complexes. Genome Res. 1999;9:27–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Oguiza J A, Buck M. DNA-binding domain mutants of sigma-N (ςN, ς54) defective between closed and stable open promoter complex formation. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:655–664. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5861954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Oguiza J A, Gallegos M T, Chaney M K, Cannon W V, Buck M. Involvement of the ςN DNA-binding domain in open complex formation. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:873–885. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Osuna J, Soberon X, Morett E. A proposed architecture for the central domain of the bacterial enhancer-binding proteins based on secondary structure prediction and fold recognition. Protein Sci. 1997;6:543–555. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pelton J G, Kustu S, Wemmer D E. Solution structure of the DNA-binding domain of NtrC with three alanine substitutions. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:1095–1110. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pérez-Martin J, de Lorenzo V. Coactivation in vitro of the ς54-dependent promoter Pu of the TOL plasmid of Pseudomonas putida by HU and the mammalian HMG-1 protein. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2757–2760. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2757-2760.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pérez-Martín J, de Lorenzo V. The ς54-dependent promoter Ps of the TOL plasmid of Pseudomonas putida requires HU for transcriptional activation in vivo by XylR. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3758–3763. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.13.3758-3763.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Popham D L, Szeto D, Keener J, Kustu S. Function of a bacterial activator protein that binds to transcriptional enhancers. Science. 1989;243:629–635. doi: 10.1126/science.2563595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Reitzer L J, Magasanik B. Transcription of glnA in E. coli is stimulated by activator bound to sites far from the promoter. Cell. 1986;45:785–792. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90553-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rombel I, North A, Hwang I, Wyman C, Kustu S. The bacterial enhancer-binding protein NtrC as a molecular machine. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1998;63:157–166. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sasse-Dwight S, Gralla J D. Probing the E. coli gln ALG upstream activation mechanism in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:8934–8938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.8934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sasse-Dwight S, Gralla J D. Role of eukaryotic-type functional domains found in the prokaryotic enhancer receptor factor ς54. Cell. 1990;62:945–954. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90269-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Scott, D. J., A. L. Ferguson, M. Buck, M.-T. Gallegos, M. Pitt, and J. G. Hoggett. Interaction of ςN with Escherichia coli RNA polymerase core enzyme. Biochem. J., in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 100.Sharp M M, Chan C L, Lu C Z, Marr M T, Nechaev S, Merritt E W, Severinov K, Roberts J W, Gross C A. The interface of sigma with core RNA polymerase is extensive, conserved, and functionally specialized. Genes Dev. 1999;13:3015–3026. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shingler V. Signal sensing by sigma 54-dependent regulators: derepression as a control mechanism. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:409–416. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.388920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Stephens R S, Kalman S, Lammel C, Fan J, Marathe R, Aravind L, Mitchell W, Olinger L, Tatusov R L, Zhao Q, Koonin E V, Davis R W. Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis. Science. 1998;282:754–759. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Stock J B, Stock A M, Mottonen J M. Signal transduction in bacteria. Nature. 1990;344:395–400. doi: 10.1038/344395a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Studholme D J, Buck M. The biology of enhancer-dependent transcriptional regulation in Bacteria: insights from genome sequences. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;186:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Studholme D J, Wigneshwereraraj S R, Gallegos M T, Buck M. Functionality of the purified ςN (ς54) and a NifA-like protein from the hyperthermophile Aquifex aeolicus. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1616–1623. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1616-1623.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Su W, Porter S, Kustu S, Echols H. DNA-looping and enhancer activity: association between DNA-bound NtrC activator and RNA polymerase at the bacterial glnA promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5504–5508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.14.5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Svergun D I, Malfois M, Koch M H J, Wigneshweraraj S R, Buck M. Low resolution structure of the ς54 transcription factor revealed by X-ray solution scattering. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4210–4214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Syed A, Gralla J D. Isolation and properties of enhancer-bypass mutants of sigma 54. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:987–995. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2851651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Syed A, Gralla J D. Identification of an N-terminal region of ς54 required for enhancer responsiveness. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5619–5625. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.21.5619-5625.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sze C C, Shingler V. The alarmone ppGpp mediates physiological-responsive control at the ς54-dependent Po promoter. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1217–1228. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Taylor M, Butler R, Chambers S, Casimiro M, Badii F, Merrick M J. The RpoN-box motif of the RNA polymerase sigma factor ςN plays a role in promoter recognition. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:1045–1054. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tintut Y, Gralla J D. PCR mutagenesis identifies a polymerase-binding sequence of sigma 54 that includes a sigma 70 homology region. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5818–5825. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5818-5825.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tintut Y, Wong C, Jiang Y, Hsieh M, Gralla J D. RNA polymerase binding using a strongly acidic hydrophobic-repeat region of sigma 54. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2120–2124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wang J T, Syed A, Gralla J D. Multiple pathways to bypass the enhancer requirement of ς54 RNA polymerase: roles for DNA and protein determinants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9538–9543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wang J T, Syed A, Hsieh M, Gralla J D. Converting Escherichia coli RNA polymerase into an enhancer-responsive enzyme: role of an NH2-terminal leucine patch in ς54. Science. 1995;270:992–994. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wang J T, Gralla J D. The transcription initiation pathway of sigma 54 mutants that bypass the enhancer protein requirement. Implications for the mechanism of activation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32707–32713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wang J T, Syed A, Gralla J D. Multiple pathways to bypass the enhancer requirment of sigma 54 RNA polymerase: roles for DNA and protein determinants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9538–9543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wang L, Gralla J D. Multiple in vivo roles for the −12-region elements of sigma 54 promoters. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5626–5631. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.21.5626-5631.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wang L, Guo Y, Gralla J D. Regulation of ς54-dependent transcription by core promoter sequences: role of −12 region nucleotides. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7558–7565. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.24.7558-7565.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wang W, Carey M, Gralla J D. Polymerase II promoter activation: closed complex formation and ATP-driven start site opening. Science. 1992;255:450–453. doi: 10.1126/science.1310361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wang Y P, Kolb A, Buck M, Wen J, O'Gara F, Buc H. CRP interacts with promoter-bound ς54 RNA polymerase and blocks transcriptional activation of the dctA promoter. EMBO J. 1998;17:786–796. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.3.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wedel A, Kustu S. The bacterial enhancer-binding protein NtrC is a molecular machine: ATP hydrolysis is coupled to transcriptional activation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2042–2052. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.16.2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Weiner L, Brissette J L, Model P. Stress-induced expression of the Escherichia coli phage shock protein operon is dependent on ς54 and modulated by positive and negative feedback mechanisms. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1912–1923. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.10.1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Weiss D S, Batut J, Klose K E, Keener J, Kustu S. The phosphorylated form of the enhancer-binding protein NTRC has an ATPase activity that is essential for activation of transcription. Cell. 1991;67:155–167. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90579-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wigneshweraraj, S. R., N. Fujita, A. Ishihama, and M. Buck. Conservation of sigma-core RNA polymerase proximity relationships between the enhancer independent and enhancer dependent sigma classes. EMBO J., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 126.Wong C, Gralla J D. A role for the acidic trimer repeat region of transcription factor sigma 54 in setting the rate and temperature dependence of promoter melting in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:24762–24768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wong C, Tintut Y, Gralla J D. The domain structure of ς54 as determined by analysis of a set of deletion mutants. J Mol Biol. 1994;236:81–90. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Wosten M M S M. Eubacterial sigma-factors. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1998;22:127–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1998.tb00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Xiao Y, Heu S, Yi J, Lu Y, Hutcheson S W. Identification of a putative alternate sigma factor and characterization of a multicomponent regulatory cascade controlling the expression of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae Pss61 hrp and hrmA genes. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1025–1036. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.4.1025-1036.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]