Abstract

Purpose of Review

Many studies have identified positive effects of physiotherapy and exercise for persons with Parkinson’s disease (PD). Most work has thus far focused on the therapeutic modality of exercise as used within physiotherapy programs. Stimulated by these positive findings, there is now a strong move to take exercise out of the clinical setting and to deliver the interventions in the community. Although the goals and effects of many such community-based exercise programs overlap with those of physiotherapy, it has also become more clear that both exercise modalities also differ in various ways. Here, we aim to comprehensively review the evidence for community-based exercise in PD.

Recent Findings

Many different types of community-based exercise for people with PD are emerging and they are increasingly being studied. There is a great heterogeneity considering the types of exercise, study designs, and outcome measures used in research on this subject. While this review is positive regarding the feasibility and potential effects of community-based exercise, it is also evident that the general quality of these studies needs improvement.

Summary

By focusing on community-based exercise, we hope to generate more knowledge on the effects of a wide range of different exercise modalities that can be beneficial for people with PD. This knowledge may help people with PD to select the type and setting of exercise activity that matches best with their personal abilities and preferences. As such, these insights will contribute to an improved self-management of PD.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11910-023-01303-0.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, Community-based exercise, Sport, Physiotherapy

Introduction

Many studies have reported on the positive effects of both physiotherapy and exercise in persons with Parkinson’s disease (PD) [1, 2]. Frequently, no clear distinction is being made between these two options. In previous guidelines, reviews, and meta-analyses on physiotherapy, exercise was included equally to other therapeutic modalities (i.e., balance training, strategy training) [1–4]. In the past years, however, the evidence for many different types of community-based exercise for people with PD has increased enormously. Although the goals and effects of many such community-based exercise programs overlap with those of physiotherapy, it has become more clear that both modalities also differ in various ways.

It is interesting to consider some differences between exercise as part of physiotherapy versus community-based exercise programs. Physiotherapy works according to movement-related questions for help, SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound) treatment goals, and a personalized treatment plan. In contrast, community-based exercise can be performed just for the fun of it [5]. Physiotherapists can use exercise as a treatment modality during their therapy, but they are usually not trained as instructors in specific types of exercise, such as boxing or dance. On the other hand, exercise instructors are normally not specialized in the consequences of having PD and the specific challenges that these may generate when engaging in an exercise program. For example, people with PD may respond differently on high-intensity exercise because of autonomic dysfunction [6]. Just like exercise programs led by trained physiotherapists, community-based exercise may also have positive effects on general health, on PD symptoms, and possibly even on disease progression [7]. However, these positive effects are, unlike physiotherapy, typically not quantified during training. Moreover, community-based exercise is usually not adjusted to the personal goals or individual capacities of each person with PD, yet both of these may be affected because of the impact of PD. This raises safety concerns when instructors do not have specialized knowledge of PD. On the other hand, performing exercise in the community offers many different options and practical advantages: it is often fun and includes a social element when performed in groups, it is performed close to home (thus reducing traveling time) and is generally much more accessible, and people can start on their own initiative and decide for themselves where, when, and how often they participate. Community-based exercise is therefore an important tool for self-management in people with PD [8].

Because of these crucial differences between physiotherapy and community-based exercise, we propose to make a clearer distinction between these two approaches, both in research and clinical practice. A personalized assessment is needed to decide whether community-based exercise is sufficient, or whether additional specialized physiotherapy is needed. We also need to further consider the level of PD-specific knowledge and expertise that is needed for instructors to work with people with PD. Finally, more research on the cost-effectiveness and dosing is necessary. A previous review indicated that community-based exercise may improve motor functions [9]. However, only motor functioning was considered as outcome in this study. We here aim to comprehensively review the evidence of different types of community-based exercise in PD. We deliberately chose to exclude aerobic exercise and strength training from this review while these can also be performed as community-based exercise in for example the gym. We excluded these types of exercise because [1] these training modalities are often also performed in physiotherapy (i.e., physiotherapists are trained in using these training modalities and they are part of the standard physiotherapy repertoire) and [2] both, but in particular aerobic exercise, have already been extensively studied and reviewed, indicating that aerobic exercise has a positive effect on cardiorespiratory fitness and motor symptoms [10–13]. Importantly, a disease-modifying potential is hypothesized based on animal studies [14, 15], observational studies [16, 17], and the first observations in clinical trials in humans [18, 19]. Future clinical trials will need to confirm and unravel this disease-modifying potential. Considering strength training, we know that this positively impacts muscle strength, motor problems, mobility, and balance [20, 21].

By focusing on community-based exercise, we hope to generate more knowledge on the effects of a wide range of different exercise modalities that can be beneficial for people with PD. This knowledge may help people with PD to select the type and setting of exercise activity that matches best with their personal abilities and preferences. As such, these insights will contribute to an improved self-management of PD.

Methods

We reviewed papers that evaluated the effects of community-based exercise in people with PD. We searched PubMed between January 2013 and November 2022 as part of the development of a new guideline for allied healthcare professionals in PD in The Netherlands (Supplementary 1). This search resulted in many hits for articles on community-based exercise, which were not included in the guideline because we classified them as not being physiotherapy. To not let this comprehensive overview go to waste, we decided to perform additional search specifically aimed at community-based exercise and review the current literature on this topic. We included randomized controlled trials (RCT) and controlled clinical trials (CCT) that compared the effect of any type of community-based exercise with (any type of) control intervention and included people with PD.

Study selection

Two reviewers screened all papers independently for inclusion. Title and abstract were screened and when necessary the full text was retrieved and evaluated. Disagreements were solved in a discussion meeting and all inclusions were based on consensus between the reviewers.

Data extraction

We extracted data from all articles using a standardized data collection form. We extracted the following data: (1) publication information (author, year), (2) study design, (3) study sample (size, age, in- and exclusion criteria), (4) intervention (type, frequency, duration, supervision, location), (5) primary and secondary outcomes, (6) results (primary and secondary outcomes), (7) conclusions. We categorized the community-based exercise into (1) yoga, (2) wuqinxi and qigong, (3) tai chi and ai chi, (4) dance, (5) Pilates, (6) (Nordic) walking, (7) climbing, and (8) kayaking.

Outcome measures

Because of the large heterogeneity in outcomes used, we decided not to limit this review based on specific outcomes. However, we did focus primarily on the primary outcomes as reported in the included papers and on the between group differences at follow-up in Table 1. In order to be as comprehensive as possible, we report the secondary outcomes in the Supplementary table.

Table 1.

Primary outcomes as reported in the included papers

| Authors (year) | Design | Sample | Primary outcome | Intervention | Control group | Result primary outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yoga (total n = 275) | ||||||

| Ni et al. (2016) [22]** | Secondary analysis |

N: 27 Age: 60–90 yrs HY: I–III MMSE: ≥ 24 |

NA | Power yoga, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group | Usual care with health education, 1 × /month, 12 wks | NA |

| Kwok et al. (2019) [23] | Single-blinded RCT |

N: 138 Age: > 18 yrs HY: I–III AMTS: < 6 |

HADS |

Mindfulness yoga, 1 × /wk, 1.5 h/ × , 8 wks, supervised, group AND Mindfulness yoga, 2 × /wk, 20 min/ × , 8 wks unsupervised, individual |

Stretching and resistance training, 1 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 8 wks, supervised, groups. 2 × /wk 20 min/ × , 8 wks unsupervised, individual | HADS: yoga >> CON |

| Van Puymbroeck et al. (2018) [24] | RCT |

N: 30 Age: ≥ 18 yrs HY: I1/2–III Short minimental status exam: ≥ 4 |

NA | Yoga, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 8 wks, supervision, group | Wait list | NA |

| Cherup et al. (2021) [25] | RCT |

N: 46 Age: 40–90 yrs HY: I–III Cognition: NA |

Joint position sense, joint kinesthesia, Tinetti balance assessment | Yoga meditation, 2 × /wk, 45 min/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group | Proprioceptive training, 2 × /wk, 45 min/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group |

Joint position sense: 0 Joint kinesthesia: yoga >> CON Tinetti balance assessment: yoga >> CON |

| Walter et al. (2019) [26]** | RCT |

N: 30 Age: NA yrs HY: I1/2 SIS: ≥ 4 |

PFS-16, ABC, FCS, FMS, ACS, PDQ-8 | Yoga, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 8 wks, supervised, group | Wait list |

PFS-16: yoga << control ABC: yoga >> control FCS: yoga >> control FMS: yoga >> control ACS: yoga >> control PDQ-8: yoga << control |

| Kwok et al. (2022) [27]** | Multicenter RCT |

N: 138 Age: > 18 yrs HY: I–III AMTS: ≥ 6 |

NA | Mindfulness yoga, 1 × /wk, 1.5 h/ × , 8 wks, supervised, group | Strength and resistance training, 1 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 8 wks, supervised, group | NA |

| Elangovan et al. (2020) [28] | RCT (pilot) |

N: 20 Age: 45–75 yrs HY: I–III MoCA: ≥ 26 |

NA | Hatha yoga, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × 12 wks, group/personal unclear, supervised | Wait list | NA |

| Ni et al. (2016) [22] | RCT |

N: 41 Age: 60–90 yrs HY: I–III MMSE: ≥ 24 |

MDS-UPDRS III |

Power training, 2 × /wk, 3 circuits of 10–12 reps, 12 wks, personal, supervised AND Yoga, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 12 wks, group, supervised |

Health education class, non-exercise | MDS-UPDRS III: PWT: + ; yoga: + ; CON: 0 |

| Wuqinxi and qigong (total n = 477) | ||||||

| Wang et al. (2020) [29] | RCT |

N: 46 Age: 55–80 yrs HY: I–III Cognition: cognitive impairment based on medical history and/or clinical assessment |

NA | Wuqinxi, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group/personal unclear | Stretching, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group/personal unclear | NA |

| Shen et al. (2021) [30] | RCT |

N: 32 Age: 55–80 yrs HY: I–III MMSE: ≥ 24 |

Stroop color and word test/FAB/MoCA | Wuqinxi, 2 × /wk, 1.5 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group/personal unclear | Stretching, 2 × /wk, 1.5 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group |

ST1: wuqinxi >> stretching; wuqinxi: + ; stretching: + ST2: wuqinxi = stretching; wuqinxi: 0; stretching: 0 FAB: wuqinxi >> stretching; wuqinxi: + ; stretching: + MoCA: wuqinxi >> stretching; wuqinxi: + ; stretching: + |

| Wan et al. (2021) [31] | RCT |

N: 52 Age: 40–85 yrs HY: I–IV MMSE: ≥ 24 |

NA | Qigong, 4 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group/personal unclear | Routine stable drug treatment was maintained within 12 weeks without any other intervention | NA |

| Xiao and Zhuang (2016) [32] | Single-blinded RCT |

N: 100 Age: 55–80 yrs HY: I–III MMSE: ≥ 23 |

UPDRS, Parkinson’s Disease Sleep Scale-2, Parkinson Fatigue Scale (PFS-16), MMSE, BBS, TUG, 6 camera Vicon 512 motion capture system (to test gait), Freezing of Gait questionnaire |

Part 1: Baduanjin qigong, 4 × 45 min supervised, group/personal unclear; audiovisual learning package of 12–15 min (8 exercises repeated 6 times at 43–49% of max HR) unsupervised Part 2: Baduanjin qigong, 4 × /week, 1 × per day, 6 months AND walking, 7 × /week, 0.5 h/ × , 6 months, unsupervised |

Walking, 7 × /week, 0.5 h/ × , 6 months, unsupervised |

UPDRS: qigong: + ; CON: 0 PDSS-2: qigong: + ; CON: 0 BBS: qigong: + ; CON: 0 6 MW: qigong: + ; CON: 0 TUG: qigong: + ; CON: 0 Gait speed: qigong: + ; CON: 0 |

| Liu et al. (2016) [33] | RCT |

N: 54 Age: NA yrs HY: NA Cognition: NA |

Myometry (Myoton-3), BDW-85-II |

Health qigong, 5 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 10 wks, supervision unclear, group/personal unclear AND Drug therapy and participation in regular daily activities |

Drug therapy and participated in regular daily activities |

Myometry (left): qigong: + ; CON: 0 Myometry (right): qigong: + ; CON: 0 |

| Moon et al. (2020) [34] | RCT (pilot) |

N: 32 Age: 40–80 yrs HY: NA MMSE: ≥ 24 |

NA |

Qigong, 1 × /wk, 0.75–1 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group AND Qigong, 14 × /wk, 0.25 h/ × , 12 weeks, unsupervised, personal |

Sham qigong, 1 × /wk, 0.75–1 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group AND Sham qigong, 14 × /wk, 0.25 h/ × , 12 weeks, unsupervised, personal |

NA |

| Li et al. (2022) [35] | Single-blinded RCT |

N: 40 Age: 60–80 yrs HY: I–III MMSE: ≥ 24 |

Gait parameters measured on a walkway: - Single-task - Obstacle crossing - Backward digit span - Serial-3 subtraction |

Wuqinxi qigong, 2 × /wk, 1.5 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group | Stretching, 2 × /wk, 1.5 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group |

Single-task (gait speed): wuqinxi qigong (WQ): + ; CON: 0; WQ >> CON Single-task (stride length): WQ: + ; CON: 0; WQ >> CON Single-task (double support): WQ: 0; CON: + ; WQ = CON Obstacle crossing (gait speed): WQ: 0; CON: 0; WQ << CON Obstacle crossing (stride length): WQ: 0; CON: 0; WQ = CON Obstacle crossing (double support): WQ: + ; CON: 0; WQ >> CON Backward digit span (gait speed): WQ: 0; CON: 0; WQ = CON Backward digit span (stride length): WQ: 0; CON: 0; WQ = CON Backward digit span (double support): WQ: 0; CON: 0; WQ >> CON Serial-3 subtraction (gait speed): WQ: 0; CON: 0; WQ = CON Serial-3 subtraction (stride length): WQ: + ; CON: 0; WQ = CON Serial-3 subtraction (double support): WQ: 0; CON: 0; WQ >> CON |

| Li et al. (2022) [35] | RCT |

N: 40 Age: 50–80 HY: I–III Cognition: NA |

NA | Health qigong, 5 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised | Wait list | NA |

| Wang et al. (2022) [36] | RCT |

N: 60 Age: 50–80 HY: I–II Cognition: NA |

NA | Wu Qin Xi, 3 × /wk, 90 min/ × , 24 wks, supervised, group | Stretching exercise, 3 × /wk, 90 min/ × , 24 wks, supervised, group | NA |

| Amano et al. (2013) [37]* | Independent single-blinded randomized controlled trials |

N: 21 Age: NA yrs HY: NA MMSE: > 26 |

(1) The magnitude of posterior and lateral COP displacement [2] The mean COP velocity in posterior and lateral directions prior to an initial heel-off of the swing limb |

Qigong meditation control, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 16 wks, supervised, group | Tai chi, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 16 wks, supervised, group |

S1DisAP: qigong = CON S1DisML: qigong << CON S1VelAP: qigong = CON S1VelML: qigong = CON |

| Tai chi and ai chi (total n = 515) | ||||||

| Amano et al. (2013) [37]* | Independent single-blinded randomized controlled trials |

N: 21 Age: NA yrs HY: NA MMSE: > 26 |

(1) The magnitude of posterior and lateral COP displacement (2) The mean COP velocity in posterior and lateral directions prior to an initial heel-off of the swing limb |

Tai chi, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 16 wks, supervised, group | Qigong meditation control, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 16 wks, supervised, group |

S1DisAP: tai chi = CON S1DisML: tai chi >> CON S1VelAP: tai chi = CON S1VelML: tai chi = CON |

| Amano et al. (2013) [37]* | Independent single-blinded randomized controlled trials |

N: 24 Age: NA yrs HY: NA MMSE: > 26 |

(1) The magnitude of posterior and lateral COP displacement (2) The mean COP velocity in posterior and lateral directions prior to an initial heel-off of the swing limb UPDRS-III |

Tai chi, 3 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 16 wks, supervised, group | Non-contact control |

S1DisAP: tai chi = CON S1DisML: tai chi = CON S1VelAP: tai chi = CON S1VelML: tai chi = CON |

| Li et al. (2014) [38] | Single-blinded randomized controlled trial |

N: 195 Age: 40–85 yrs HY: I–IV |

NA |

Tai chi, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 26 wks, supervised, group OR Resistance training, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 26 wks, supervised, group |

Stretching, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 26 wks, supervised, group | NA |

| Gao et al. (2014) [39] | Single-blinded randomized control trial |

N: 80 Age: > 40 yrs HY: NA MMSE: ≥ 24 |

UPDRS III, BBS, TUG | Tai chi, 3 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group | No intervention |

UPDRS-III: tai chi = CON BBS: tai chi >> CON TUG: tai chi = CON |

| Kurt et al. (2018) [40] | RCT |

N: 40 Age: NA yrs HY: II–III MMSE: ≥ 24 |

Biodex-3.1, BBS, TUG, PDQ-39, UPDRS-III | Ai chi, 5 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 5 wks, supervised, group/personal unclear | Land-based exercise, 5 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 5 wks, supervision unclear, group/personal unclear |

Biodex-3.1 (API): ai chi: + ; CON: + ; ai chi >> CON Biodex-3.1 (ML): ai chi: + ; CON: + ; ai chi >> CON Biodex-3.1 (OBI): ai chi: + ; CON: + ; ai chi >> CON BBS: ai chi: + ; CON: + ; ai chi >> CON TUG: ai chi: + ; CON: + ; ai chi >> CON UPDRS-III: ai chi: + ; CON: + ; ai chi >> CON PDQ-39: ai chi: + ; CON: + ; ai chi >> CON |

| Pérez de la Cruz (2017) [41] | Prospective single-blind RCT |

N: 30 Age: > 40 yrs HY: I–III MMSE: ≥ 24 |

Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for pain | Ai chi, 2 × /wk, 45 min/ × , 10 wks, supervised, group | Dry land therapy, 2 × /wk, 45 min/ × , 10 wks, supervised, group | VAS: ai chi: + ; CON: + (ai chi more significant) |

| Pérez de la Cruz (2018) [42] | RCT (pilot) |

N: 29 Age: > 40 yrs HY: I–III MMSE: ≥ 24 |

NA | Ai chi, 2 × /wk, 45 min/ × , 11 wks, supervised, group | Dry land therapy, 2 × /wk, 45 min/ × , 11 wks, supervised, group | NA |

| Pérez de la Cruz (2019) [43]** | Single-blind RCT |

N: 30 Age: > 40 yrs HY: I–III MMSE: ≥ 24 |

NA | Ai chi, 2 × /wk, 45 min/ × , 10 wks, supervised, group | Dry land therapy, 2 × /wk, 45 min/ × , 10 wks, supervised, group | NA |

| Khuzema et al. (2020) [44]* | RCT |

N: 27 Age: 60–85 yrs HY: II1/2–III Cognition: NA |

NA |

Tai chi, 5 × /wk, 30–40 min/ × , 10 wks, supervised (first time) remainder of time unsupervised, personal OR Yoga, 5 × /wk, 30–40 min/ × , 10 wks, supervised (first time) remainder of time unsupervised, personal |

Conventional balance exercise program, 5 × /wk, 40–45 min/ × , 10 wks, supervised (first time) remainder of time unsupervised, personal | NA |

| Zhang et al. (2015) [45] | RCT |

N: 40 Age: NA HY: I–IV MMSE: ≥ 24 MMSE: ≥ 17 (if participant did not attend school) MMSE: ≥ 20 (if participant only finished elementary education) |

Berg Balance Scale (BBS) | Tai chi, 2 × /wk, 60 min/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group | Multimodal exercise training, 2 × /wk, 60 min/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group | BBS: tai chi: 0; CON: + ; tai chi = CON |

| Poier et al. (2019) [46]* | RCT (pilot) |

N: 29 Age: 50–90 yrs HY: NA Cognition: NA |

PDQ-39 | Tai chi, 1 × /wk, 60 min/ × , 10wks, supervised, group, with own partner | Tango Argentino, 1 × /wk, 60 min/ × , 10wks, supervised, group, with own partner | PDQ-39: tai chi: 0; CON: 0; tai chi = CON |

| Dance (total n = 692) | ||||||

| Duncan and Earhart (2014) [47] | RCT (pilot) |

N: 10 Age: > 40 yrs HY: NA Cognition: NA |

MDS-UPDRS III | Argentine tango, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 2 yrs, supervised, group | No prescribed exercise, instructed to maintain current level of physical activity | MDS-UPDRS III: tango >> CON |

| Rios Romenets et al. (2015) [48] | RCT (pilot) |

N: 33 Age: NA yrs HY: I–III Cognition: no dementia |

MDS-UPRDS-3 | Argentine tango, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group | Wait list | MDS-UPDRS III: tango = CON |

| Hashimoto et al. (2015) [49] | Quasi RCT (pilot) |

N: 59 Age: NA yrs HY: NA Cognition: NA |

NA |

Dance, 1 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group/personal unclear OR PD-exercise, 1 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group/personal unclear |

Usual care | |

| Shanahan et al. (2017) [50] | RCT (pilot) |

N: 90 Age: NA yrs HY: I–II1/2 Cognition: NA |

Feasibility: correct randomization and allocation, resources, recruitment rates, willingness of participation, attrition rates |

Dancing, 1 × /wk, 1.5 h/ × , 10 wks, supervised, group AND 20-min home dance program, 3 × /wk |

Usual care | Attendance was 93.5%. Compliance with home program was 71.46% |

| Hulbert et al. (2017) [51] | RCT |

N: 27 Age: NA yrs HY: I–III Cognition: NA |

NA | Dance (ballroom and Latin American), 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 10 wks, supervised, group | Usual care | NA |

| Lee et al. (2018) [52] | RCT |

N: 32 Age: 50–80 yrs HY: I–III MMSE: > 20 |

MDS-UPDRS | Turo (qi dance), 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 8 wks, supervised, group/personal unclear | Wait list |

UPDRS (mentation and mood): Turo = CON UPDRS (activities): Turo >> CON UPDRS (motor examination): Turo >> CON UPDRS (total): Turo >> CON |

| Michels et al. (2018) [53] | RCT |

N: 13 Age: > 18 yrs HY: I–V MMSE: ≥ 24 |

Class attendance, safety and satisfaction | Dance/movement therapy (DT), 1 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 10 wks, supervised, group | Talk therapy/support group, 1 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 10 wks, supervised, group | No adverse events, 7 out of 9 participants in intervention group and 4 out of 4 in control group were attended 70% of the sessions (which was the aim). Satisfaction; 7 out of 9 felt they benefited, 2 felt neutral. One person did not enjoy of feel benefited from the classes, but this person was in the control group and indicated to be disappointed not to be in the DT group |

| Rawson et al. (2019) [54] | RCT |

N: 119 Age: ≥ 30 yrs HY: I–IV Cognition: NA |

NA |

Tango, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group OR Treadmill, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group |

Stretching, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group | NA |

| Kalyani et al. (2019) [55] | Quasi-experimental parallel group pre-test post-test study |

N: 38 Age: 40–85 yrs HY: I–III ACE: > 82 |

NA | Dance, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group | Usual care | NA |

| Tillmann et al. (2020) [56] | Non-randomized CT (feasibility study) |

N: 20 Age: ≥ 50 yrs HY: I–IV MMSE: ≥ 13 for illiterate people ≥ 18 for average education ≥ 26 for high schooling |

NA | Brazilian samba, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group | Monthly lectures on health, prevention of falls and psychological care, advise to avoid beginning new physical activity | NA |

| Frisaldi et al. (2021) [57] | Single-blind RCT (pilot) |

N: 38 Age: NA yrs HY: I–II Cognition: NA |

MDS-UPDRS III |

Dance (DArT), 3 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 5 wks, supervised, group Followed by (after 30 min break): Conventional physiotherapy, 3 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 5 wks, supervised, group |

Conventional physiotherapy, 3 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 5 wks, supervised, group Followed by (after 30 min break): Conventional physiotherapy, 3 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 5 wks, supervised, group |

MDS-UPDRS III (total): Dance >> CON MDS-UPDRS III (upper): Dance >> CON MDS-UPDRS III (lower): Dance = CON MDS-UPDRS III (axial): Dance = CON |

| Foster et al. (2013) [58] | RCT |

N: 62 Age: NA yrs HY: I–IV Cognition: NA |

ACS2 | Argentine tango, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 52 wks, supervised, group | Usual care | Total current participation in the tango group was higher at 3, 6, and 12 months compared with baseline (Ps .008), while the control group did not change (Ps!.11). Total activity retention (since onset of PD) in the tango group increased from 77 to 90% (PZ.006) over the course of the study, whereas the control group remained around 80% (PZ.60). These patterns were similar in the separate activity domains. The tango group gained a significant number of new social activities (PZ.003), but the control group did not (PZ.71) |

| Kunkel et al. (2017) [59] | RCT (feasibility) |

N: 51 Age: NA yrs HY: I–III Cognition: NA |

BBS, spinal mouse | Dance, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 10 wks, supervised, group | Usual care |

BBS: dance = CON Spinal mouse: dance = CON |

| Poier et al. (2019) [46]* | RCT (pilot) |

N: 29 Age: 50–90 HY: NA Cognition: NA |

PDQ-39 | Tango Argentino, 1 × /wk, 60 min/ × , 10wks, supervised, group, with own partner | Tai chi, 1 × /wk, 60 min/ × , 10wks, supervised, group, with own partner | PDQ-39: tango: 0; CON: 0; tango = CON |

| Solla et al. (2019) [60] | RCT (pilot) |

N: 20 Age: NA HY: ≤ 3 MMSE: ≥ 24 |

NA | Ballu Sardu (Sardinian folk dance), 2 × /wk, 90 min/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group | Usual care | NA |

| Li et al. (2022) [35] | RCT (three arm) |

N: 51 Age: 40–85 HY: 1–3 Cognition: NA |

NA | Yang-ge dancing 5 × /wk, 60 min/ × , 4 wks, ? |

CON (I) Conventional exercise 5 × /wk, 60 min/ × , 4 wks, ? CON (II) Conventional exercise plus music 5 × /wk, 60 min/ × , 4 wks, ? |

NA |

| Pilates (total n = 91) | ||||||

| Maciel et al. (2020) [61] | Prospective open label non-randomized controlled clinical trial study |

N: 42 Age: > 40 yrs HY: < 3 Cognition: NA |

Balance improvement, not further specified | Pilates, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 6 wks, supervised, group | Regular exercise, at least 2 × /wk, NA hr/ × , 6 wks, supervised, personal | NA |

| Mollineda-Cardalda et al. (2018) [62] | RCT |

N: 26 Age: NA yrs HY: I–III Cognition: no clinical history of dementia |

NA | Pilates, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group | Physical activity program (calisthenics), 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group | NA |

| Göz et al. (2021) [63] | RCT (pilot) |

N: 23 Age: ≥ 18 HY: ≤ 2 MMSE: ≥ 24 |

NA |

Pilates, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 6 wks, supervised, group OR Pilates + elastic taping, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 6 wks, supervised, group |

Wait list | NA |

| (Nordic) walking (total n = 220) | ||||||

| Cugusi et al. (2015) [64] | RCT |

N: 20 Age: 40–80 yrs HY: I–III MMSE: ≥ 24 |

NA | Nordic walking, 2 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group | Conventional care | NA |

| Monteiro et al. (2017) [65] | RCT |

N: 33 Age: > 50 yrs HY: I–IV Cognition: NA |

NA | Nordic walking, 2 × /wk, 35–60 min/ × , 9 wks, supervised, group (6 familiarization sessions (35–50 min), 12 training sessions (1 h)) | Free walking, 2 × /wk, 35–50 min/ × , 9 wks, supervised, group (6 familiarization sessions (35–50 min), 12 training sessions (1 h)) | NA |

| Bang and Shin (2017) [66] | RCT (pilot) |

N: 20 Age: NA yrs HY: I–III MMSE: ≥ 24 |

NA | Nordic walking, 5 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 4 wks, supervised, group/personal unclear | Treadmill, 5 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 4 wks, supervised, group/personal unclear | NA |

| Granziera et al. (2021) [67] | RCT |

N: 37 Age: NA yrs HY: II–III MMSE: ≥ 24 |

UPDRS-III | Nordic walking, 2 × /wk, 1.25 h/ × , 8 wks, supervised, group | Walking, 2 × /wk, 1.25 h/ × , 8 wks, supervised, group | UPDRS-III: NW = CON |

| Mak and Wong (2021) [68] | RCT |

N: 70 Age: > 30 yrs HY: NA MoCA: ≥ 25 |

MDS-UPDRS-III | Brisk walking, 3 × /wk, 1–1.5 h/ × , 26 wks, supervised, group; first 6 weeks 1 training session of 90 min and 2 self-practice sessions of 60–90 min | Upper limb and hand dexterity, 3 × /wk, 1–1.5 h/ × , 26 wks, supervised, group | UPDRS-III: BW: + ; CON: 0; BW >> CON |

| Szefler-Derela et al. (2020) [69] | RCT |

N: 40 Age: NA yrs HY: II–III MMSE: ≥ 24 |

UPDRS-III | Nordic walking, 2 × /wk, 1.5 h/ × , 6 wks, supervised, group | Standard rehabilitation, 2 × /wk, 0.75 h/ × , 6 wks, supervised, personal | UPDRS-III: NW: + ; CON: + ; NW >> CON |

| Franzoni et al. (2018) [70]** | RCT |

N: 33 Age: > 50 yrs HY: I–IV MoCA: ≥ 26 |

NA | Nordic walking, 2 × /wk, 35–60 min/ × , 9 wks, supervised, group (6 familiarization sessions (35–50 min), 12 training sessions (1 h)) | Free walking, 2 × /wk, 35–50 min/ × , 9 wks, supervised, group (6 familiarization sessions (35–50 min), 12 training sessions (1 h)) | NA |

| Boxing (total n = 100) | ||||||

| Sangarapillai et al. (2021) [71] | RCT |

N: 40 Age: NA yrs HY: NA Cognition: NA |

UPDRS-III | Boxing, 3 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 10 wks, supervised, group | PD Sensory Attention Focused Exercise, 3 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 10 wks, supervised, group | UPDRS-III: Boxing: − ; CON: + ; Boxing << CON |

| Domingos et al. (2022) [8] | RCT (pilot) |

N: 29 Age: NA HY: NA MMSE: ≥ 24 |

Mini-BESTest, Feasibility | Boxing with kicks (BK), 1 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 10 wks, group, supervised | Boxing, 1 × /wk, 1 h/ × , 10 wks, group, supervised |

Mini-BESTest: BK: + ; CON: + ; BK = CON Feasibility: The trainings were completed by 85% of the participants |

| Combs et al. (2013) [72] | RCT |

N: 31 Age: ≥ 21 HY: NA Cognition: NA |

NA | Boxing, 2–3 × /wk, 90 min/ × , 12 wks, group, supervised | Traditional exercise, 2–3 × /wk, 90 min/ × , 12 wks, group, supervised | NA |

| Climbing (total n = 48) | ||||||

| Langer et al. (2021) [73] | RCT |

N: 48 Age: NA yrs HY: 2–3 MMSE: ≥ 24 |

MDS-UPDRS-III | Top rope sport climbing (SC), 1 × /wk, 1.5 h/ × , 12 wks, supervised, group | Unsupervised physical training group, 150 min per week moderate exercise or 75 min per week vigorous exercise, resistance training 2 × /wk, balance exercises 3 × /wk, 12 wks |

MDS-UPDRS-III: SC >> CON MDS-UPDRS-III (bradykinesia): SC >> CON MDS-UPDRS-III (rigidity): SC >> CON MDS-UPDRS-III (tremor): SC >> CON |

| Kayaking (total n = 48) | ||||||

| Shujaat et al. (2014) [74] | RCT |

N: 48 Age: 35–65 yrs HY: I–III Cognition: NA |

NA | Kayaking, 6 × /wk, 75 min/ × , 4 wks, group, supervised | Strengthening exercise, 6 × /wk, 75 min/ × , 4 wks, group, supervised | NA |

+ denotes a positive within-group effect, − denotes a negative within-group effect, 0 denotes no within-group effect, >> denotes a between-group effect favoring the group on the left of the sign, << denotes a between-group effect favoring the group on the right of the sign, = denotes a similar between-group effect in both groups

ABC, Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale; ACE, Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination; ACS, Activities Constraint Scale; ACS2, Activity Card Sort; AMTS, Abbreviated Mental Test Score; API, anteroposterior index; BBS, Berg Balance Scale; BDW-85-II, muscle stability; BK, boxing with kicks; BW, brisk walking; CON, control group; COP, center of pressure; DT, dance therapy; FAB, frontal assessment battery; FCS, Falls Control Scale; FMS, Falls Management Scale; HADS, Hamilton Anxiety and Depression Scale; HR, heart rate; HY, Hoehn and Yahr stage; MDS-UPDRS, Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; MMSE, Mini-State Examination; N, sample size; NA, not applicable; OBI, overall balance index; PD, Parkinson’s disease; PDQ-8, Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire 8; PDQ-39, Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire 39; PDSS-2, Parkinson’s Disease Sleep Scale-2; PFS-16, Parkinson’s Disease Fatigue Scale; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SC, sport climbing; SIS, Six-Item Screener; S1DisAP, magnitude of the posterior COP displacement; S1DisML, magnitude of the lateral COP displacement; S1VelAP, mean COP velocity in posterior direction; S1VelML, mean COP velocity in lateral direction; TUG, Timed Up and Go; VAS, Visual Analog Scale; WQ, wuqinxi qigong

Results

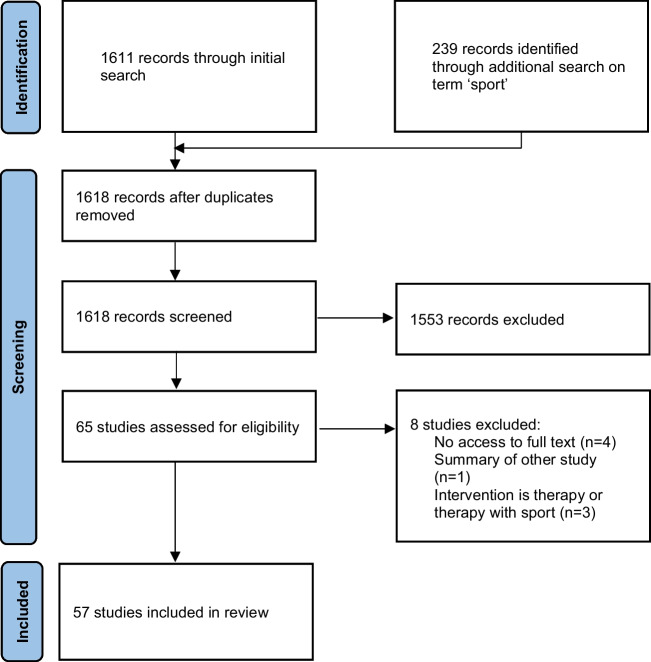

Our search yielded 1618 unique publications. After title and abstract screening, 65 studies remained of which 57 were included in the final review (Fig. 1). These 57 studies described 53 exercise interventions (five studies described a secondary analysis, one study described two interventions) in a total of 2416 participants. The interventions varied in frequency (1–6 sessions/week), duration (mostly for 12 weeks or shorter with only a few that lasted longer (up to 2 years) [47]), and supervision (mostly supervised and in a group setting). Only few studies reported a single primary outcome measure. Overall, outcome measures were very heterogeneous but focused mostly on PD motor symptoms and balance.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of studies

Our results are summarized in Table 1. We will now briefly describe the main results of each exercise category separately.

Yoga

Eight studies investigated the effect of (different types of) yoga, of which three reported a secondary analysis [24, 27, 75]. Yoga may alleviate non-motor problems such as anxiety and depressive symptoms, as was shown by the largest of the yoga studies including 138 participants [23, 27]. Other studies found a potential positive effect on motor problems such as balance [22, 26]. Conflicting evidence was found for the effects on quality of life [26, 27].

Wuqinxi and Qigong

Ten studies investigated the effect of wuqinxi or qigong in a total of 477 people with PD. Most of the studies were in the pilot phase, mainly studying safety and feasibility. While wuqinxi and qigong were found to be safe and feasible for people with PD, we cannot draw firm conclusions on its effects. Most studies show preliminary effects (mostly within group differences) on physical functioning. The largest and longest study (n = 100, 6 months) compared Baduanjin qigong with an active control intervention (i.e., walking exercises, 7 times per week) and found no group differences [32]. However, motor symptoms, sleep, endurance, and balance improved in both groups. Interestingly, another study found that qigong was associated with a promising improvement of motor symptoms, sleep quality, balance, and endurance; these findings warrant further study [34].

Tai Chi and Ai Chi

Ten studies investigated the effect of tai chi or ai chi; nine were original studies, while one reported a secondary analysis [76] and one study described two interventions [37]. All studies were supervised, except the study of Khuzema et al. [44] who provided the first session under supervision, while the remainder of the intervention was unsupervised. Tai chi and ai chi seem to improve balance (as measured with the Berg Balance Scale), as confirmed by three studies showing a between-group effect compared to a control group [39–41] and one study showing a within-group effect [44]. Another study showed a within-group improvement in balance only in the control group that received multimodal exercise training, but not in the tai chi group [45]. Also, some beneficial effects on motor symptoms (MDS-UPDRS) and health-related quality of life (PDQ-8) were found (Table 1).

Dance

Sixteen studies investigated the effect of very different types of dance on PD ranging from tango, samba and folk, to ballroom dance. All interventions were supervised and delivered in a group setting, except for three studies, for which the group setting was unclear [35, 49, 52]. One study combined supervised group dance sessions with a dance program at home, which 71.5% of the participants complied with [50]. In another study, participants danced with their own partner [46]. Dance had a beneficial effect on (parts of the) MDS-UPDRS compared to the control group in four studies [47, 52, 56, 57, 60]. However, one study did not find such an effect [48]. The study of Duncan et al. [47] evaluated a 24-month intervention which showed that improvements were maintained over a prolonged period of time. However, this study was performed in a small group of only 10 participants. Finally, some studies emphasized that dance may improve not only physical functioning, but also cognitive and mental functioning. Results on other outcome measures were scarce.

Pilates

Three studies investigated the effect of Pilates in 91 persons with PD. None of the studies specified a primary outcome and all secondary outcomes assessed motor function (i.e., UPDRS, TUG, BBS; Table 1). At the moment, there is insufficient evidence for Pilates.

(Nordic) Walking

Six studies (one secondary analysis) investigated the effect of Nordic walking, while one study evaluated brisk walking. Most studies assessed the effects on PD motor symptoms, endurance, balance, and mobility and found beneficial effects favoring the (Nordic) walking group. Granziera et al. [67] compared Nordic walking with regular walking and found no added beneficial effect of Nordic walking. In contrast, three studies [65, 66, 70] also compared Nordic walking to a regular walking control group and did find an additional beneficial effect on gait and balance. Altogether, (Nordic) walking seems to improve functional mobility and gait. The effects on non-motor problems and quality of life remain unclear.

Boxing

Three studies investigated the effect of (kick)-boxing. All of them included an active control group (PD Sensory Attention Focused Exercise, boxing without kicks and traditional exercise). Overall, boxing did not show many additional effects over exercise performed in the control groups. However, boxing seemed feasible and safe and within-group improvements on gait, balance, and motor symptoms were found. Given the limited number of studies, small sample sizes, and small contrast between the intervention and control groups, we cannot draw firm conclusions about the effects of boxing for people with PD.

Rope Sport

Langer et al. [73] investigated the effect of sport climbing compared (12 weeks) to a control group that received unsupervised physical training in 48 people with PD. Climbing had a significant beneficial effect on motor symptoms (MDS-UPDRS-III) compared to the control group. Safety would seem to be an issue but no adverse events were reported and adherence to the climbing sessions was 99%. This novel intervention certainly deserves further study.

Kayaking

Shujaat et al. [74] investigated the effect of kayaking six times per week for 4 weeks compared to a strengthening exercise group that exercised at the same frequency. Both interventions resulted in improvements in mobility.

Discussion

Many different types of community-based exercise for people with PD are emerging and they are increasingly being studied. We here reviewed the evidence that is currently available for different types of community-based exercise in people with PD. This resulted in a heterogeneous overview of many types of exercise, study designs, and outcome measures. Despite limitations in study designs resulting in potential bias (e.g., selection bias), lack of generalizability, and modest effects sizes, all types of community-based exercise that we identified seem to be safe and feasible. We have to be more careful about the possible beneficial effects in light of the various limitations in study design, but overall, most programs appeared to have some beneficial effects in people with PD. But the positive experience with feasibility and adherence is perhaps the most important finding, because in order to achieve enduring benefits in a chronic and progressive disorder like PD, long-term adherence to exercise is critical, yet precisely this is challenging for many persons with PD, for a variety of reasons [9, 77]. Being able to choose from a range of activities to find an optimal fit between capability and preference will make exercise more enjoyable and thereby help to increase long-term adherence. Another interesting finding is that some types of community-based exercise (e.g., qigong, dance) are not only associated with the general physical benefits of exercise, but also seem to improve a range of non-motor symptoms and functioning, such as sleep, cognition, or emotional wellbeing. Because these symptoms of the disease generally respond less well to medical treatment [78, 79], this may have relevant effects on the quality of life of people with PD. Given the limitations in study design, it is uncertain whether these beneficial effects were driven by the intrinsic action of, e.g., qigong or dance, or whether these can also be ascribed — at least in part — to aspecific elements such as the social component of the group-based intervention.

An important question that remains to be answered is who should supervise community-based exercise for people with PD? In general, exercise instructors working in the community do not have PD-specific expertise, but physiotherapists (who are more skilled in PD care) are not qualified as exercise instructors of specific types of exercise like tai chi or dance. The main concerns here include safety and being able to adjust the activity to the capacities of the participant with PD. For physiotherapy, treatment by a therapist who is specialized in PD (through education and hands-on experience) has been shown to be more (cost-)effective than usual care physiotherapy [80, 81]. These benefits of specialized physiotherapy could be ascribed in part to the prevention of PD-related complications, including falls and fall-related injuries. We could argue that exercise instructors working with groups of people with PD should also receive some elementary education about PD, its progression, and safety. We mentioned the risk of falls as one potential but realistic concern, but another one is cardiovascular complications — persons with PD have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease [82], so strenuous exercise programs could potentially be associated with, e.g., myocardial infarction. This is not to say that all persons with PD should be screened for such cardiovascular risks prior to engaging in community-based exercise programs, but it is a factor that should be considered on a personal basis, based on a good understanding of PD and health issues in general. On the other hand, community-based exercise could rightly be considered as a leisure activity that is not part of regular healthcare. Should problems or symptoms emerge that make it difficult to participate in community-based exercise (or that need treatment), then a specialized physiotherapist could be consulted to receive further detailed personalized advice. Another option would be that a physiotherapist is consulted for a comprehensive evaluation and individually tailored exercise prescription, which is then subsequently performed in the community.

While this review is positive regarding the feasibility and potential effects of community-based exercise, it is also evident that the quality of the studies needs much improvement. For example, only a few studies specified a primary outcome. Many studies included multiple primary outcomes and some studies did not even differentiate between primary and secondary outcomes. In addition, the outcomes varied considerably across different studies. Most studies assessed physical functioning and motor symptoms, but non-motor symptoms and quality of life were often not included. It is essential to select outcome measures that are clinically relevant and meaningful for people with PD. This issue of relevance can sometimes be questioned, for example when joint angles or gait kinematics are the only outcomes (notwithstanding their merits for understanding the basic working mechanism of a given intervention). Consequently, the great variability in outcomes and the lack of primary, hypothesis-driven, outcomes make it difficult to draw any firm conclusions. Moreover, hardly any adequately powered studies were performed, and the large majority of studies used small sample sizes and short-duration interventions, further decreasing the strength of the evidence. Finally, the participants included in these studies were mainly in Hoehn and Yahr stages 1–3. Nine studies also allowed participants in Hoehn and Yahr stage 4. However, only very few people in Hoehn and Yahr stage 4 actually participated. Therefore, we cannot generalize these results to more advanced disease stages.

These challenges are not new and are partly inherent to studying non-pharmacological interventions which are inherently complex in nature. Challenges mainly relate to selecting appropriate interventions (both experimental and control), intervention dosing, adherence, and potential confounding. Other than in medication studies, dosing (including intensity, frequency, and duration) of a non-pharmacological intervention is very difficult and depends on many contextual factors (i.e., motivation and time of participant, expertise of the supervisor, etc.). It is also notoriously hard to measure adherence and the actual dosage received, often relying on self-report. Choosing an appropriate control intervention may be even more difficult, allowing for enough contrast while limiting nocebo effects (the negative effect of knowing to not be in the active intervention group). In the field of non-pharmacological interventions, there is no such thing as a true placebo intervention, and blinding of participants is hardly possible. Moreover, contamination between the treatment and control intervention and selection bias of participants interested in the subject occur frequently. While these challenges make these types of studies more complex, many of these can be overcome by carefully designing studies based on solid hypotheses about working mechanisms and based on pilot work that is abundantly available, as was shown by our present review. In general, we plea that the same quality criteria, as applied to pharmacological studies, should be applied to non-pharmacological interventions as well. The time is ripe for adequately designed (phase III) RCTs in the field of exercise in PD that not only assess efficacy but also to unravel the underlying working mechanisms.

In this review, we offered an extensive overview of the many studies that have been performed on community-based exercise in PD so far. We started this review from an initiative that intended to systematically search the literature for physiotherapy interventions and we adopted a pragmatic search strategy along the way. Therefore, we might have missed several trials. However, given the broad search strategy and systematic selection of articles, we believe that we covered the subject comprehensively. We would have liked to perform a meta-analysis on the results, based on which we could have drawn more rigorous conclusions about effect sizes and the comparative effectiveness of the different types of community-based exercise. We ultimately chose not to do this because of the large variety in interventions (types, dosing, duration), the great variety in outcome measures, and the overall small sample sizes, which would have reduced the power of such an analysis. Future studies are warranted to further study the clinical effects of community-based exercise, mainly in the long term, where we feel that the greatest promise lies. On the other hand, we doubt whether it is useful and needed to study every type of community-based exercise on (long-term) effectiveness, especially in a time of limited financial recourse for research. The effects of exercise have been widely studied in PD [2], and community-based exercise could be seen as way to keep people engaged in exercise in the long term [8]. This review shows that all types of community-based exercise seem to have some clinical effects as studied in many small pilot studies. At this point, we need innovative and efficient designs to push the field forward, beyond the pilot testing phase. The multiple arm multiple stage (MAMS) platform trials may offer an attractive solution by allowing efficient clinical evaluations across multiple interventions with one shared control group [83, 84]. An additional advantage of a MAMS trial is that a standard set of outcome measures allows for comparison between interventions and working mechanisms and that interim analyses make adaptations during the trial possible. In the meantime, different types of community-based exercise can be safely performed by people with PD, supporting them in managing their disease and maintaining or even improving quality of life.

Conclusion

Many types of community-based exercise are available for people with PD, increasing access to exercise for more people. While feasibility has been largely shown, the evidence on the effects remains scarce for most of the interventions because of methodological constraints. However, the knowledge provided in this review may help people with PD to select the type and setting of exercise activity that matches best with their personal abilities and preferences. As such, these insights will contribute to an improved self-management of PD.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author Contribution

Literature search, data collection and analyses were performed by AL, SS and LB. AL, SS and NMdV interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to critically revising the manuscript. All authors approved submission of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development. The Radboudumc Center of Expertise for Parkinson & Movement Disorders was supported by a center of excellence grant of the Parkinson’s Foundation.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Radder DLM, Lígia Silva de Lima A, Domingos J, Keus SHJ, van Nimwegen M, Bloem BR, et al. Physiotherapy in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of present treatment modalities. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2020;34(10):871–80. doi: 10.1177/1545968320952799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ernst M, Folkerts AK, Gollan R, Lieker E, Caro-Valenzuela J, Adams A, et al. Physical exercise for people with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;1(1):Cd013856. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013856.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keus SH, Munneke M, Graziano M, et al. European physiotherapy guideline for Parkinson’s disease The Netherlands: KNGF/ ParkinsonNet; 2014.

- 4.Tomlinson CL, Patel S, Meek C, Herd CP, Clarke CE, Stowe R, et al. Physiotherapy versus placebo or no intervention in Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:Cd002817. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002817.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenfeldt AB, Koop MM, Penko AL, Zimmerman E, Miller DM, Alberts JL. Components of a successful community-based exercise program for individuals with Parkinson’s disease: results from a participant survey. Complement Ther Med. 2022;70:102867. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2022.102867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sabino-Carvalho JL, Vianna LC. Altered cardiorespiratory regulation during exercise in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a challenging non-motor feature. SAGE Open Med. 2020;8:2050312120921603. doi: 10.1177/2050312120921603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li JA, Loevaas MB, Guan C, Goh L, Allen NE, Mak MKY, et al. Does exercise attenuate disease progression in people with Parkinson’s disease? A systematic review with meta-analyses. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2023;37(5):328–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Domingos J, Dean J, Fernandes JB, Massano J, Godinho C. Community exercise: a new tool for personalized Parkinson’s care or just an addition to formal care? Front Syst Neurosci. 2022;16:916237. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2022.916237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang CL, Huang JP, Wang TT, Tan YC, Chen Y, Zhao ZQ, et al. Effects and parameters of community-based exercise on motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. 2022;22(1):505. doi: 10.1186/s12883-022-03027-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van der Kolk NM, de Vries NM, Kessels RPC, Joosten H, Zwinderman AH, Post B, et al. Effectiveness of home-based and remotely supervised aerobic exercise in Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(11):998–1008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Schenkman M, Moore CG, Kohrt WM, Hall DA, Delitto A, Comella CL, et al. Effect of high-intensity treadmill exercise on motor symptoms in patients with de novo Parkinson disease: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(2):219–226. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schootemeijer S, van der Kolk NM, Bloem BR, de Vries NM. Current perspectives on aerobic exercise in people with Parkinson’s disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2020;17(4):1418–1433. doi: 10.1007/s13311-020-00904-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gamborg M, Hvid LG, Dalgas U, Langeskov-Christensen M. Parkinson’s disease and intensive exercise therapy - an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2022;145(5):504–528. doi: 10.1111/ane.13579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petzinger GM, Fisher BE, McEwen S, Beeler JA, Walsh JP, Jakowec MW. Exercise-enhanced neuroplasticity targeting motor and cognitive circuitry in Parkinson’s disease. The Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(7):716–726. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70123-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jang Y, Koo JH, Kwon I, Kang EB, Um HS, Soya H, et al. Neuroprotective effects of endurance exercise against neuroinflammation in MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease mice. Brain Res. 2017;1655:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon SY, Suh JH, Yang SN, Han K, Kim YW. Association of physical activity, including amount and maintenance, with all-cause mortality in Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(12):1446–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Tsukita K, Sakamaki-Tsukita H, Takahashi R. Long-term effect of regular physical activity and exercise habits in patients with early parkinson disease. Neurology. 2022;98(8):e859–e871. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000013218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johansson ME, Cameron IGM, Van der Kolk NM, de Vries NM, Klimars E, Toni I, et al. Aerobic exercise alters brain function and structure in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Neurol. 2022;91(2):203–216. doi: 10.1002/ana.26291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hortobágyi T, Vetrovsky T, Balbim GM, Sorte Silva NCB, Manca A, Deriu F, et al. The impact of aerobic and resistance training intensity on markers of neuroplasticity in health and disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2022;80:101698. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2022.101698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gollan R, Ernst M, Lieker E, Caro-Valenzuela J, Monsef I, Dresen A, et al. Effects of resistance training on motor- and non-motor symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Parkinson’s Dis. 2022;12(6):1783–1806. doi: 10.3233/JPD-223252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gamborg M, Hvid LG, Thrue C, Johansson S, Franzén E, Dalgas U, et al. Muscle strength and power in people with Parkinson disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Phys Ther : JNPT. 2023;47(1):3–15. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ni M, Mooney K, Signorile JF. Controlled pilot study of the effects of power yoga in Parkinson’s disease. Complement Ther Med. 2016;25:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwok JYY, Kwan JCY, Auyeung M, Mok VCT, Lau CKY, Choi KC, et al. Effects of mindfulness yoga vs stretching and resistance training exercises on anxiety and depression for people with Parkinson disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(7):755–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Van Puymbroeck M, Walter AA, Hawkins BL, Sharp JL, Woschkolup K, Urrea-Mendoza E, et al. Functional improvements in Parkinson’s disease following a randomized trial of yoga. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018;2018:8516351. doi: 10.1155/2018/8516351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cherup NP, Strand KL, Lucchi L, Wooten SV, Luca C, Signorile JF. Yoga meditation enhances proprioception and balance in individuals diagnosed with parkinson’s disease. Percept Mot Skills. 2021;128(1):304–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Walter AA, Adams EV, Van Puymbroeck M, Crowe BM, Urrea-Mendoza E, Hawkins BL, et al. Changes in nonmotor symptoms following an 8-week yoga intervention for people with Parkinson’s disease. Int J Yoga Therap. 2019;29(1):91–99. doi: 10.17761/2019-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwok JYY, Choi EPH, Lee JJ, Lok KYW, Kwan JCY, Mok VCT, et al. Effects of mindfulness yoga versus conventional physical exercises on symptom experiences and health-related quality of life in people with Parkinson’s disease: the potential mediating roles of anxiety and depression. Ann Behav Med. 2022;56(10):1068–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Elangovan N, Cheung C, Mahnan A, Wyman JF, Tuite P, Konczak J. Hatha yoga training improves standing balance but not gait in Parkinson’s disease. Sports Med Health Sci. 2020;2(2):80–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Wang T, Xiao G, Li Z, Jie K, Shen M, Jiang Y, et al. Wuqinxi exercise improves hand dexterity in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020;2020:8352176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Shen M, Pi YL, Li Z, Song T, Jie K, Wang T, et al. The feasibility and positive effects of wuqinxi exercise on the cognitive and motor functions of patients with parkinson’s disease: a pilot study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021;2021:8833736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Wan Z, Liu X, Yang H, Li F, Yu L, Li L, et al. Effects of health qigong exercises on physical function on patients with parkinson’s disease. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:941–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Xiao CM, Zhuang YC. Effect of health Baduanjin Qigong for mild to moderate Parkinson’s disease. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16(8):911–919. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu XL, Chen S, Wang Y. Effects of health qigong exercises on relieving symptoms of parkinson’s disease. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:5935782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Moon S, Sarmento CVM, Steinbacher M, Smirnova IV, Colgrove Y, Lai SM, et al. Can Qigong improve non-motor symptoms in people with Parkinson’s disease - a pilot randomized controlled trial? Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2020;39:101169. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li F, Wang D, Ba X, Liu Z, Zhang M. The comparative effects of exercise type on motor function of patients with Parkinson’s disease: a three-arm randomized trial. Front Hum Neurosci. 2022;16:1033289. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2022.1033289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Z, Pi Y, Tan X, Wang Z, Chen R, Liu Y, et al. Effects of Wu Qin Xi exercise on reactive inhibition in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:961938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Amano S, Nocera JR, Vallabhajosula S, Juncos JL, Gregor RJ, Waddell DE, et al. The effect of Tai Chi exercise on gait initiation and gait performance in persons with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2013;19(11):955–960. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li F, Harmer P, Liu Y, Eckstrom E, Fitzgerald K, Stock R, et al. A randomized controlled trial of patient-reported outcomes with tai chi exercise in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2014;29(4):539–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Gao Q, Leung A, Yang Y, Wei Q, Guan M, Jia C, et al. Effects of Tai Chi on balance and fall prevention in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2014;28(8):748–753. doi: 10.1177/0269215514521044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kurt EE, Büyükturan B, Büyükturan Ö, Erdem HR, Tuncay F. Effects of Ai Chi on balance, quality of life, functional mobility, and motor impairment in patients with Parkinson’s disease<sup/>. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(7):791–797. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1276972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pérez de la Cruz S. Effectiveness of aquatic therapy for the control of pain and increased functionality in people with Parkinson’s disease: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2017;53(6):825–32. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.17.04647-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pérez-de la Cruz S. A bicentric controlled study on the effects of aquatic Ai Chi in Parkinson disease. Complement Ther Med. 2018;36:147–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Pérez-de la Cruz S. Mental health in Parkinson's disease after receiving aquatic therapy: a clinical trial. Acta Neurol Belg. 2019;119(2):193–200. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Khuzema A, Brammatha A, Arul SV. Effect of home-based Tai Chi, Yoga or conventional balance exercise on functional balance and mobility among persons with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: an experimental study. Hong Kong Physiother J. 2020;40(1):39–49. doi: 10.1142/S1013702520500055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang TY, Hu Y, Nie ZY, Jin RX, Chen F, Guan Q, et al. Effects of Tai Chi and multimodal exercise training on movement and balance function in mild to moderate idiopathic Parkinson disease. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;94(10 Suppl 1):921–929. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poier D, Rodrigues Recchia D, Ostermann T, Bussing A. A randomized controlled trial to investigate the impact of tango Argentino versus Tai Chi on quality of life in patients with Parkinson disease: a short report. Complement Med Res. 2019;26(6):398–403. doi: 10.1159/000500070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duncan RP, Earhart GM. Are the effects of community-based dance on Parkinson disease severity, balance, and functional mobility reduced with time? A 2-year prospective pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20(10):757–763. doi: 10.1089/acm.2012.0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rios Romenets S, Anang J, Fereshtehnejad SM, Pelletier A, Postuma R. Tango for treatment of motor and non-motor manifestations in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized control study. Complement Ther Med. 2015;23(2):175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hashimoto H, Takabatake S, Miyaguchi H, Nakanishi H, Naitou Y. Effects of dance on motor functions, cognitive functions, and mental symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: a quasi-randomized pilot trial. Complement Ther Med. 2015;23(2):210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shanahan J, Morris ME, Bhriain ON, Volpe D, Lynch T, Clifford AM. Dancing for Parkinson disease: a randomized trial of Irish set dancing compared with usual care. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(9):1744–1751. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hulbert S, Ashburn A, Roberts L, Verheyden G. Dance for Parkinson’s-the effects on whole body co-ordination during turning around. Complement Ther Med. 2017;32:91–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Lee HJ, Kim SY, Chae Y, Kim MY, Yin C, Jung WS, et al. Turo (qi dance) program for Parkinson’s disease patients: randomized, assessor blind, waiting-list control, partial crossover study. Explore (NY) 2018;14(3):216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Michels K, Dubaz O, Hornthal E, Bega D. “Dance Therapy” as a psychotherapeutic movement intervention in Parkinson’s disease. Complement Ther Med. 2018;40:248–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Rawson KS, McNeely ME, Duncan RP, Pickett KA, Perlmutter JS, Earhart GM. Exercise and parkinson disease: comparing tango, treadmill, and stretching. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2019;43(1):26–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Kalyani HHN, Sullivan KA, Moyle G, Brauer S, Jeffrey ER, Kerr GK. Impacts of dance on cognition, psychological symptoms and quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. NeuroRehabilitation. 2019;45(2):273–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Tillmann AC, Swarowsky A, Corrêa CL, Andrade A, Moratelli J, Boing L, et al. Feasibility of a Brazilian samba protocol for patients with Parkinson’s disease: a clinical non-randomized study. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2020;78(1):13–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Frisaldi E, Bottino P, Fabbri M, Trucco M, De Ceglia A, Esposito N, et al. Effectiveness of a dance-physiotherapy combined intervention in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Neurol Sci. 2021;42(12):5045–5053. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Foster ER, Golden L, Duncan RP, Earhart GM. Community-based Argentine tango dance program is associated with increased activity participation among individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(2):240–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Kunkel D, Fitton C, Roberts L, Pickering RM, Roberts HC, Wiles R, et al. A randomized controlled feasibility trial exploring partnered ballroom dancing for people with Parkinson’s disease. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(10):1340–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Solla P, Cugusi L, Bertoli M, Cereatti A, Della Croce U, Pani D, et al. Sardinian folk dance for individuals with Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled pilot trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(3):305–16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Maciel DP, Mesquita VL, Marinho AR, Ferreira GM, Abdon AP, Maia FM. Pilates method improves balance control in Parkinson’s disease patients: an open-label clinical trial. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2020;77:18–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Mollinedo-Cardalda I, Cancela-Carral JM, Vila-Suárez MH. Effect of a mat pilates program with theraband on dynamic balance in patients with parkinson's disease: feasibility study and randomized controlled trial. Rejuvenation Res. 2018;21(5):423–30. doi: 10.1089/rej.2017.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Göz E, Çolakoğlu BD, Çakmur R, Balci B. Effects of pilates and elastic taping on balance and postural control in early stage parkinson’s disease patients: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2021;58(4):308–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Cugusi L, Solla P, Serpe R, Carzedda T, Piras L, Oggianu M, et al. Effects of a nordic walking program on motor and non-motor symptoms, functional performance and body composition in patients with Parkinson’s disease. NeuroRehabilitation. 2015;37(2):245–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Monteiro EP, Franzoni LT, Cubillos DM, de Oliveira FA, Carvalho AR, Oliveira HB, et al. Effects of Nordic walking training on functional parameters in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017;27(3):351–358. doi: 10.1111/sms.12652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bang DH, Shin WS. Effects of an intensive Nordic walking intervention on the balance function and walking ability of individuals with Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2017;29(5):993–999. doi: 10.1007/s40520-016-0648-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Granziera S, Alessandri A, Lazzaro A, Zara D, Scarpa A. Nordic walking and walking in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized single-blind controlled trial. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33(4):965–971. doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01617-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mak MKY, Wong-Yu ISK. Six-month community-based brisk walking and balance exercise alleviates motor symptoms and promotes functions in people with parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Parkinsons Dis. 2021;11(3):1431–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Szefler-Derela J, Arkuszewski M, Knapik A, Wasiuk-Zowada D, Gorzkowska A, Krzystanek E. Effectiveness of 6-week nordic walking training on functional performance, gait quality, and quality of life in parkinson's disease. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;56(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Franzoni LT, Monteiro EP, Oliveira HB, da Rosa RG, Costa RR, Rieder C, et al. A 9-week Nordic and free walking improve postural balance in Parkinson’s disease. Sports Med Int Open. 2018;2(2):E28–E34. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-124757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sangarapillai K, Norman BM, Almeida QJ. Box vs sensory exercise for parkinson’s disease: a double-blinded randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2021;35(9):769–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Combs SA, Diehl MD, Chrzastowski C, Didrick N, McCoin B, Mox N, et al. Community-based group exercise for persons with Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled trial. NeuroRehabilitation. 2013;32(1):117–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Langer A, Hasenauer S, Flotz A, Gassner L, Pokan R, Dabnichki P, et al. A randomised controlled trial on effectiveness and feasibility of sport climbing in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinson’s Dis. 2021;7(1):49. doi: 10.1038/s41531-021-00193-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shujaat F, Soomro N, Khan M. The effectiveness of kayaking exercises as compared to general mobility exercises in reducing axial rigidity and improve bed mobility in early to mid stage of Parkinson’s disease. Pak J Med Sci. 2014;30(5):1094–1098. doi: 10.12669/pjms.305.5231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ni M, Signorile JF, Mooney K, Balachandran A, Potiaumpai M, Luca C, et al. Comparative effect of power training and high-speed yoga on motor function in older patients with Parkinson disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(3):345–54 e15. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.10.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pérez-de la Cruz S. A bicentric controlled study on the effects of aquatic Ai Chi in Parkinson disease. Complement Ther Med. 2018;36:147–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schootemeijer S, van der Kolk NM, Ellis T, Mirelman A, Nieuwboer A, Nieuwhof F, et al. Barriers and motivators to engage in exercise for persons with Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinson’s Dis. 2020;10(4):1293–1299. doi: 10.3233/JPD-202247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bloem BR, Okun MS, Klein C. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2021;397(10291):2284–2303. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00218-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nonnekes J, Timmer MH, de Vries NM, Rascol O, Helmich RC, Bloem BR. Unmasking levodopa resistance in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2016;31(11):1602–1609. doi: 10.1002/mds.26712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ypinga JHL, de Vries NM, Boonen L, Koolman X, Munneke M, Zwinderman AH, et al. Effectiveness and costs of specialised physiotherapy given via ParkinsonNet: a retrospective analysis of medical claims data. The Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):153–161. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30406-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Talebi AH, Ypinga JHL, De Vries NM, Nonnekes J, Munneke M, Bloem BR, et al. Specialized versus generic allied health therapy and the risk of Parkinson’s disease complications. Mov Disord. 2023;38(2):223–231. doi: 10.1002/mds.29274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nanhoe-Mahabier W, de Laat KF, Visser JE, Zijlmans J, de Leeuw FE, Bloem BR. Parkinson disease and comorbid cerebrovascular disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(10):533–541. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zeissler ML, Li V, Parmar MKB, Carroll CB. Is it possible to conduct a multi-arm multi-stage platform trial in Parkinson’s disease: lessons learned from other neurodegenerative disorders and cancer. J Parkinson’s Dis. 2020;10(2):413–428. doi: 10.3233/JPD-191856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Love SB, Cafferty F, Snowdon C, Carty K, Savage J, Pallmann P, et al. Practical guidance for running late-phase platform protocols for clinical trials: lessons from experienced UK clinical trials units. Trials. 2022;23(1):757. doi: 10.1186/s13063-022-06680-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.