SUMMARY

Cancer cell genetic variability and similarity to host cells has stymied development of broad anti-cancer therapeutics. Our innate immune system evolved to clear genetically diverse pathogens and limit host toxicity; however, whether/how innate immunity can produce similar effects in cancer is unknown. Here we show that human, but not murine, neutrophils release catalytically active neutrophil elastase (ELANE) to kill many cancer cell types while sparing non-cancer cells. ELANE proteolytically liberates the CD95 death domain, which interacts with histone H1 isoforms to selectively eradicate cancer cells. ELANE attenuates primary tumor growth and produces a CD8+T-cell-mediated abscopal effect to attack distant metastases. Porcine pancreatic elastase (ELANE homolog) resists tumor-derived protease inhibitors and exhibits markedly improved therapeutic efficacy. Altogether, our studies suggest that ELANE kills genetically diverse cancer cells with minimal toxicity to non-cancer cells, raising the possibility of developing it as a broad anti-cancer therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is a disease of mutations, which exhibits a high degree of spatial and temporal genetic heterogeneity (Stratton et al., 2009; Vogelstein et al., 2013). In addition to overcoming this heterogeneity, eradicating cancer cells while sparing non-cancer cells remains a formidable task. For these reasons, identifying agents that couple broad efficacy across cancer types while maintaining specificity to limit host toxicity has been challenging.

Broad efficacy and specificity are integral properties of innate immunity. Our innate immune system protects against a wide range of infectious pathogens including bacteria, fungi, and protozoa, whose genetic variability far exceeds cancer. As critical effectors of innate immunity, neutrophils eliminate genetically diverse pathogens, and may be ideally poised to perform a comparable function in cancer. Indeed, human blood polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) can kill cancer cells (Sagiv et al., 2015; Yan et al., 2014), and their therapeutic potential is being explored in clinical trials. Despite the emerging focus on PMNs, the mechanisms by which they kill cancer cells are incompletely understood.

In contrast to the anti-cancer function of PMNs, many studies showed that neutrophils can also promote tumorigenesis. This conflict could be due to species differences in neutrophil function and/or their tissue source and activation status, all of which can produce striking functional differences (Coffelt et al., 2016; Eruslanov et al., 2017; Kruger et al., 2015). For instance, murine studies suggest that tumor cells ‘hijack neutrophils’ to release molecules to facilitate metastatic spread (Coffelt et al., 2015; Finisguerra et al., 2015). And, increased tumor-associated neutrophil accumulation is a poor prognostic marker in many cancers (Coffelt et al., 2016; Powell and Huttenlocher, 2016; Shen et al., 2014).

Considering the complex roles neutrophils play in cancer, we sought to identify anti-cancer factor(s) in PMNs from healthy donors, understand their regulation across human and murine neutrophils of different sources, and explore their therapeutic potential. Our studies identified neutrophil elastase (ELANE) and its porcine homolog, porcine pancreatic elastase (PPE), as powerful anti-cancer proteins that combine broad efficacy across many cancer types with specificity to limit host toxicity. They further revealed a fundamental difference between human and murine neutrophils in mobilizing this ELANE-mediated anti-cancer pathway, which has important implications for translating mechanistic insights from mice to humans.

RESULTS

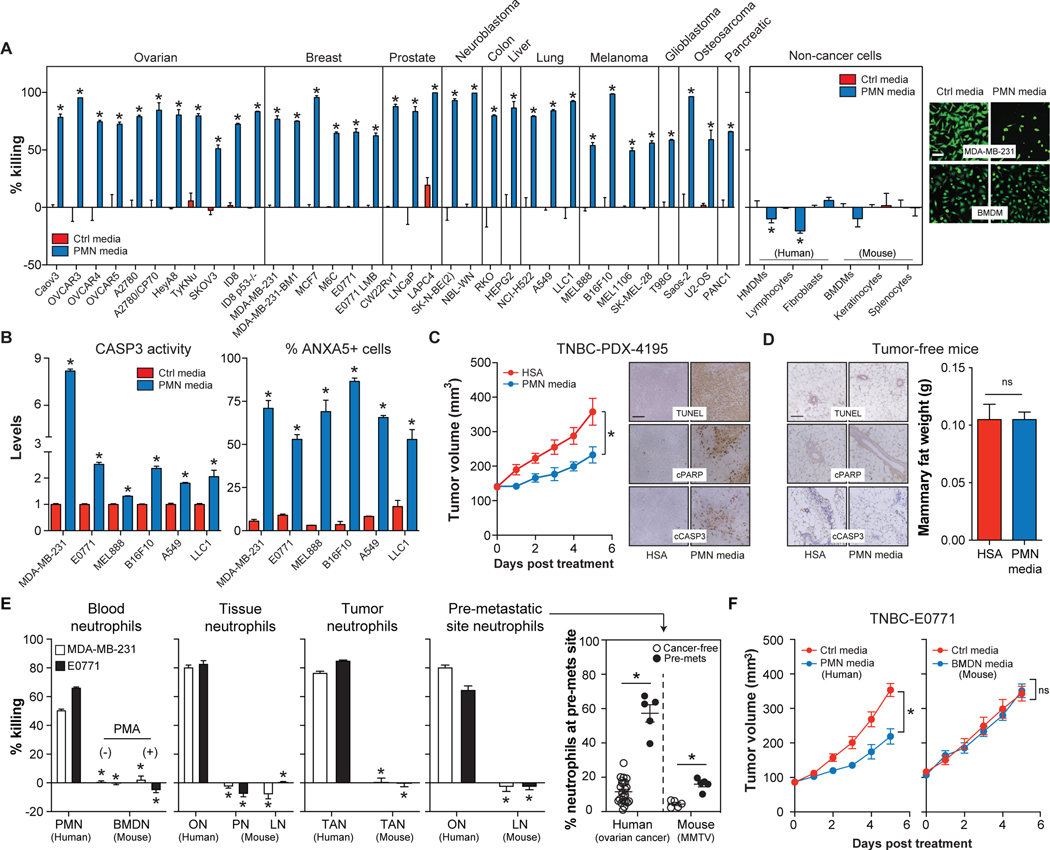

Human, but not murine, neutrophils release factor(s) that selectively kill cancer cells

Human PMNs have a short half-life in vivo (~8h) and undergo apoptosis to release potent anti-microbial factors (Dancey et al., 1976; Nathan, 2006). To determine if these factors also kill cancer cells, we treated 35 different human or murine cancer cells with serum-free media conditioned by apoptotic PMNs (PMN media) (Figures S1A–B). PMN media effectively killed all 35 cancer cells tested via apoptosis (Figures 1A–B, S1C). In contrast, PMN media was not toxic to all non-cancer cells tested (Figure 1A). Cancer cell killing by PMN media was inhibited by serum, but serum could not rescue cancer cells if delivered after exposure to PMN media under serum-free conditions (Figures S1D–E), suggesting the presence of an inhibitor.

Figure. 1. Human, but not murine, neutrophils release factor(s) that selectively kill cancer cells.

(A-B) Cancer or non-cancer cells were treated with PMN media (30μg/mL protein) for 24h. Cell viability was quantified by calcein-AM fluorescence and representative images are provided (A). CASP3 activity assay and ANXA5 staining (B). n=3–6/group. Scale bar = 30μm.

(C) PMN media or human serum albumin (HSA) (50μg protein/day, 5 days) were injected into TNBC PDX-4195 tumors and tumor volume and apoptosis were assessed. n=14–16/group. Scale bar = 100μm.

(D) PMN media or HSA (50μg protein/day, 5 days) were injected into mammary fat pads of tumor-free C57BL/6 mice. Mammary fat apoptosis and weight were monitored. n=4/group.

(E) Human and murine neutrophils were isolated from various tissues. MDA-MB-231 and E0771 cell viability (calcein-AM) was assessed following treatment with neutrophil media for 24h. n=3–6/group. Neutrophil accumulation at pre-metastatic (pre-mets) sites was quantified by flow cytometry. n=5–24/group. See also Figure S1.

(F) PMN media or BMDN media (50μg protein/day, 5 days) or Ctrl media were injected intratumorally into TNBC-E0771 tumors and tumor volume was monitored daily. n=7–12/group.

*, p<0.05 Student’s t-test, data are mean ± SEM. Ctrl media = serum-free DMEM.

We further determined if PMN media induced cancer cell apoptosis in vivo. Because serum antagonized PMN media, we injected it intratumorally into syngeneic E0771 (triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)), LLC1 (lung cancer), and B16F10 tumors (melanoma) or TNBC patient-derived xenograft (PDX)-4195 tumors. PMN media attenuated tumor growth and induced cancer cell apoptosis in every model tested (Figures 1C, S1F–H). In contrast, PMN media injected into mammary fat of tumor-free C57BL/6 mice (control for TNBC studies) did not induce apoptosis or reduce fat mass at the injection site (Figure 1D). Thus, PMN media contains factor(s) that selectively kill cancer cells in vitro and in vivo.

To determine if this anti-cancer function was a general property of neutrophils, we purified human and murine neutrophils from a variety of different sources (Figures S1I–K). Human sources included PMNs from healthy donors, omental adipose tissue neutrophils (ONs) from non-cancer patients, tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) from ovarian cancer patients with metastatic tumors, and ONs from omental adipose tissue (primary metastatic site) of pre-metastatic ovarian cancer patients, whose levels were elevated prior to metastatic dissemination (Figure 1E, Table S1) (Lee et al., 2019; Peinado et al., 2017). Murine sources included bone marrow-derived neutrophils (BMDNs) with and without activation with phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA), peritoneal neutrophils (PNs) 7h-post thioglycolate injection, TANs from E0771 tumors, and pre-metastatic lung neutrophils (LNs) from MMTV-PyMT mice, which accumulate (Figure 1E) and facilitate metastasis (Wculek and Malanchi, 2015).

All human neutrophil conditioned media tested killed human MDA-MB-231 and murine E0771 cancer cells. However, none of the murine neutrophil conditioned media tested had this capability (Figure 1E). Furthermore, unlike human PMN media, intratumorally injected murine BMDN media failed to attenuate E0771 tumor growth in vivo (Figure 1F).

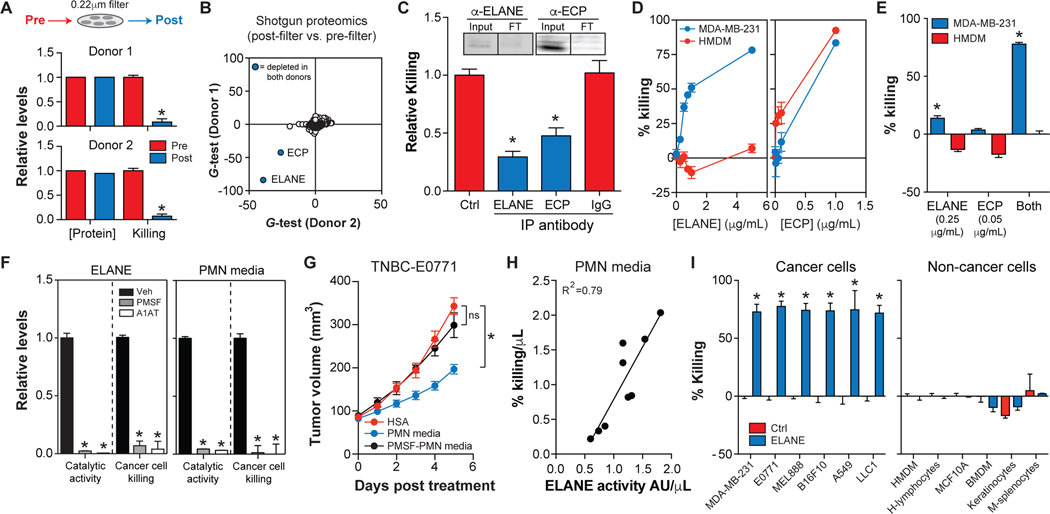

ELANE is the major anti-cancer protein released by human PMNs

Our findings indicate that human neutrophils release factor(s) that selectively kill a wide range of cancer cells, but this property is absent in murine neutrophils. To identify anti-cancer factor(s) in human PMN media, we developed a quantitative killing assay to track bioactive factors (Figure S1L). Boiling, dialysis, and size exclusion experiments prompted us to search for proteins (Figure S1M). Next, we sought to purify the proteins responsible. PMN media was prepared for fractionation by clarification through a 0.22μm filter. Surprisingly, filtration eliminated cancer killing by PMN media from 2 donors without lowering total protein (Figure 2A), suggesting a selective depletion of the bioactive proteins.

Figure. 2. ELANE is the major anti-cancer protein in human PMN media.

(A) Effect of passing PMN media through a 0.22μm filter on protein levels and MDA-MB-231 cell viability (calcein-AM). n=3/group.

(B) Proteomics analysis of PMN media pre- and post-filtration. Significantly down-regulated proteins were identified by the G-test (blue circle, p<0.05 with Bonferonni correction). See also Table S2.

(C) Effect of immunodepleting ECP or ELANE from PMN media on MDA-MB-231 cell viability (calcein-AM). Depletion of ECP or ELANE was confirmed by western blotting (Input = pre-depletion, FT = post-depletion). n=4/group.

(D) Dose-response effect of purified human ELANE or ECP on MDA-MB-231 cell or HMDM viability (calcein-AM). n=3/group.

(E) Effect of purified human ELANE or ECP on MDA-MB-231 cell or HMDM viability (calcein-AM) alone or in combination. n=3/group.

(F) Effect of serine protease inhibitors (1mM PMSF or 42nM A1AT) on catalytic activity and MDA-MB-231 cancer cell viability (calcein-AM) of purified ELANE or PMN media. n=4/group. Veh = ethanol.

(G) PMN media, PMSF-inactivated PMN media, or HSA were injected intratumorally into E0771 tumors and tumor volume was measured. n=8–9/group.

(H) Linear regression analysis of MDA-MB-231 cell killing by PMN media vs. ELANE catalytic activity in PMN media from 9 healthy donors. n=6/donor.

(I) Effect of ELANE (3μg/mL, 6h) on cancer and non-cancer cell viability (calcein-AM). n=3/group.

*, p<0.05 Student’s t-test, data are mean ± SEM.

Shotgun proteomics analysis of PMN media revealed that only 2 of 890 detected proteins were significantly lowered by filtration in both donors (Bonferroni corrected p<0.05): neutrophil elastase (ELANE) and eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) (Figures 2B, S2A, Table S2). ELANE is a serine protease thought to promote tumorigenesis (Houghton et al., 2010), while ECP is a pore-forming protein that kills both cancer and non-cancer cells (Young et al., 1986). Interestingly, T-cells kill a wide range of cancer cells through the concerted efforts of a serine protease (granzyme B) and a pore-forming protein (perforin) (Catalfamo and Henkart, 2003), raising the possibility that neutrophils might implement a similar mechanism.

Two approaches were used to determine if ELANE and/or ECP are responsible for cancer cell killing by PMN media. First, we immuno-depleted ELANE or ECP from PMN media and found that depleting either protein attenuated MDA-MB-231 cell killing (Figure 2C). Second, we tested whether purified ELANE or ECP could selectively kill cancer cells. ELANE killed MDA-MB-231 cells in a dose-dependent manner without affecting human monocyte-derived macrophages (HMDMs), while ECP was toxic to both cell types (Figure 2D).

Next, we treated MDA-MB-231 cells with concentrations of ELANE (0.25μg/mL) and ECP (0.05μg/mL) present in PMN media. Although PMN media levels of ECP did not kill MDA-MB-231 cells alone, they significantly enhanced ELANE-mediated killing (Figure 2E), suggesting a synergy between these proteins.

Because ELANE influences biological pathways by proteolysis (Pham, 2006), we hypothesized that its anti-cancer function requires catalytic activity, which ECP might enhance to support synergistic killing. We inactivated ELANE with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) or alpha-1-anti-trypsin (A1AT) and found that catalytically inactive ELANE could not kill MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 2F). Furthermore, inhibiting ELANE activity in PMN media with PMSF or A1AT eliminated the ability of PMN media to kill cancer cells in vitro and in vivo (Figures 2F–G). These results indicate that ELANE is the major anti-cancer protein in PMN media. Indeed, ELANE activity in PMN media was strongly correlated with MDA-MB-231 cell killing across nine healthy donors (Figure 2H).

We further determined if ECP could enhance ELANE’s enzymatic activity. Results showed that ECP is a type II allosteric activator of ELANE, wherein ECP binds ELANE with high affinity (KD = 17nM) and increases its catalytic turnover (kcat) by ~12-fold (Figures S2B–E). Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) experiments showed that ECP binds ELANE in human PMN media (Figure S2E). These results appear to explain why immunodepleting ECP (and ELANE by association) attenuated cancer cell killing even though PMN media levels of ECP were not toxic to cancer cells. Moreover, because ECP has a high affinity for biological membranes (Torrent et al., 2008), these findings may also help to explain why filtration through a 0.22μm filter selectively depleted ECP (and ELANE by association) from PMN media.

Moving forward, we focused on ELANE because it is both effective and safe in vitro, and ECP’s ability to enhance its catalytic activity could be mimicked by raising the concentration of ELANE. Indeed, higher doses of ELANE (3μg/mL) effectively killed all cancer cells tested but were not toxic to all non-cancer cells tested (Figures 2I, S2F).

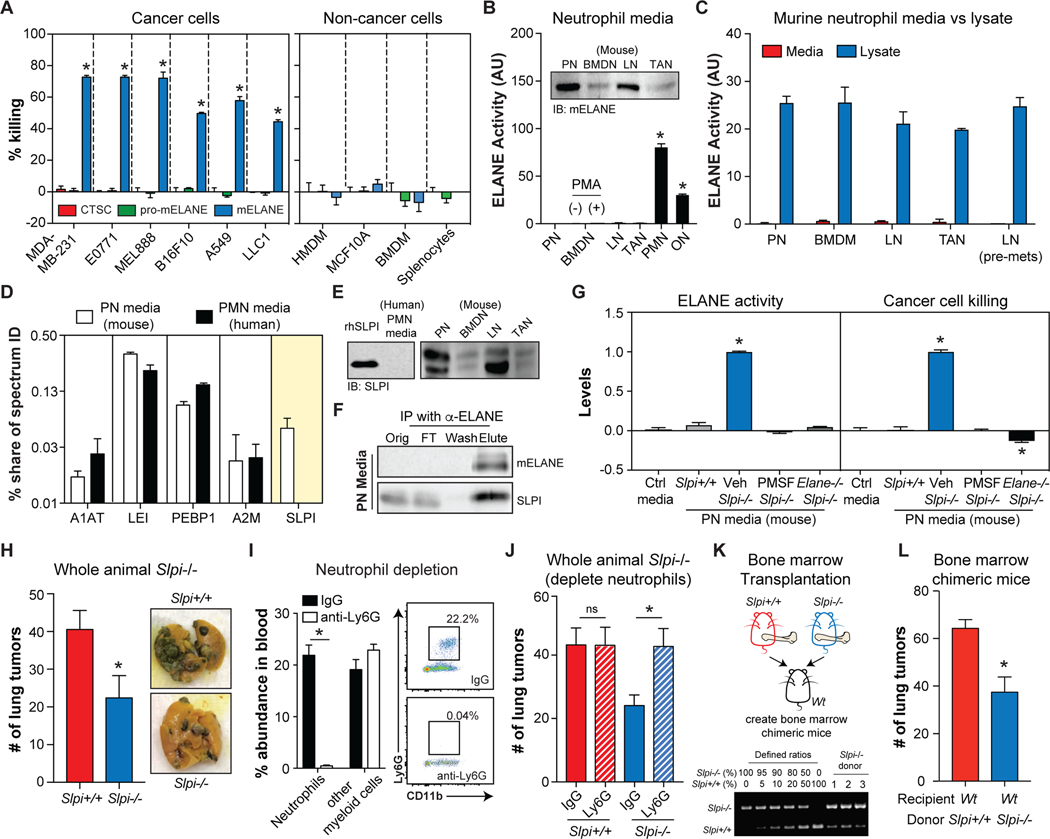

Murine neutrophils co-release SLPI to inactivate extracellular ELANE activity

Having identified ELANE as the predominant anti-cancer protein in human PMN media, we explored if differences in ELANE biology between human and murine neutrophils could explain their discrepant cancer cell killing. We first confirmed that murine ELANE (mELANE) could selectively kill human and murine cancer cells (Figure 3A), ruling out the idea that species differences in amino acid sequence and/or protein structure were responsible.

Figure. 3. Restoring extracellular ELANE activity in murine neutrophils attenuates tumorigenesis.

(A) Effect of CTSC, pro-mELANE, or mELANE (3μg/mL, 24h) on cancer and non-cancer cell viability (calcein-AM). n=6/group.

(B) ELANE catalytic activity in murine and human neutrophil media. n=4/group. Immunoblotting detects mELANE in murine neutrophil media (inset).

(C) Comparison of ELANE catalytic activity in murine neutrophil media (n=4/group) and lysates (n=2/group) isolated from various sources.

(D) Serine protease inhibitor levels in human PMN and murine PN media quantified by shotgun proteomics, n=2/group. See also Table S3.

(E) Immunoblots of SLPI in human and murine neutrophil media. Recombinant human SLPI (rhSLPI) was included as a control.

(F) Co-immunoprecipitation of SLPI with mELANE in murine PN media.

(G) mELANE activity in PN media from Slpi+/+, Slpi−/− mice with or without PMSF treatment, or Slpi−/− Elane−/− mice (left). Effects of those media on MDA-MB-231 cell viability (calcein-AM) (right). n=3/group.

(H-J) B16F10 lung tumor colonization in whole animal Slpi−/− mice and Slpi+/+ control mice (left), along with representative images (right); n=6–10/group (H). Effect of neutrophil depletion (I) on lung tumor colonization in Slpi+/+ and Slpi−/− mice (J); n=7–11/group.

(K) Schematic for generating Slpi+/+ or Slpi−/− chimeric mice (top). Engraftment efficiency was quantified using defined mixtures of Slpi+/+ and Slpi−/− bone marrow cells (bottom).

(L) B16F10 lung tumor colonization in Slpi+/+ and Slpi−/− chimeric mice; n=11/group.

*, p<0.05 Student’s t-test, data are mean ± SEM.

Next, we determined if murine neutrophils release mELANE in a catalytically active form, which is required for cancer cell killing. Whereas ELANE activity was detectable in human neutrophil media (PMNs, ONs), it was undetectable in murine neutrophil media (BMDNs, PNs, LNs, TANs, pre-metastatic LNs), including BMDNs treated with PMA, which activates neutrophils and induces degranulation (Figures 3B–C). Our inability to detect mELANE activity in murine neutrophil media was surprising given that mELANE protein was present in the media (Figure 3B), and mELANE activity was detectable in cell lysates from all murine neutrophils tested (Figure 3C).

We reasoned that murine neutrophils might co-release an inhibitor into media that is absent in their human counterparts. To explore this, we performed shotgun proteomics analysis of murine PN and human PMN media. These studies identified 5 serine protease inhibitors (Figure 3D, Table S3). Secretory leukocyte peptidase inhibitor (SLPI) was the only inhibitor exclusively detected in murine PN media and immunoblotting validated this finding (Figures 3D–E). Co-IP studies further showed that SLPI was bound to mELANE in murine PN media (Figure 3F), suggesting that SLPI may be responsible for inhibiting extracellular mELANE activity. Indeed, mELANE activity and cancer cell killing were detectable in Slpi-deficient PN media, and both of these effects were blocked by treatment with PMSF or with Elane−/− (Figure 3G).

We further investigated if deleting Slpi would equip neutrophils with the ability to oppose tumor development in vivo. To test this, we injected B16F10 cells i.v. and monitored lung tumor colonization. Lung tumor colonization was attenuated in whole animal Slpi−/− mice (Figure 3H). Depleting neutrophils increased the number of lung tumors in Slpi−/− mice but not in Slpi+/+ mice (Figures 3I–J). And eliminating Slpi selectively in myeloid cells (via bone marrow transplantation) was sufficient to lessen lung tumor colonization and phenocopy the whole animal Slpi−/− phenotype (Figures 3K–L). Altogether, these data suggest that ‘humanizing’ murine neutrophils (by deleting Slpi) restores extracellular ELANE activity and its associated anti-cancer function.

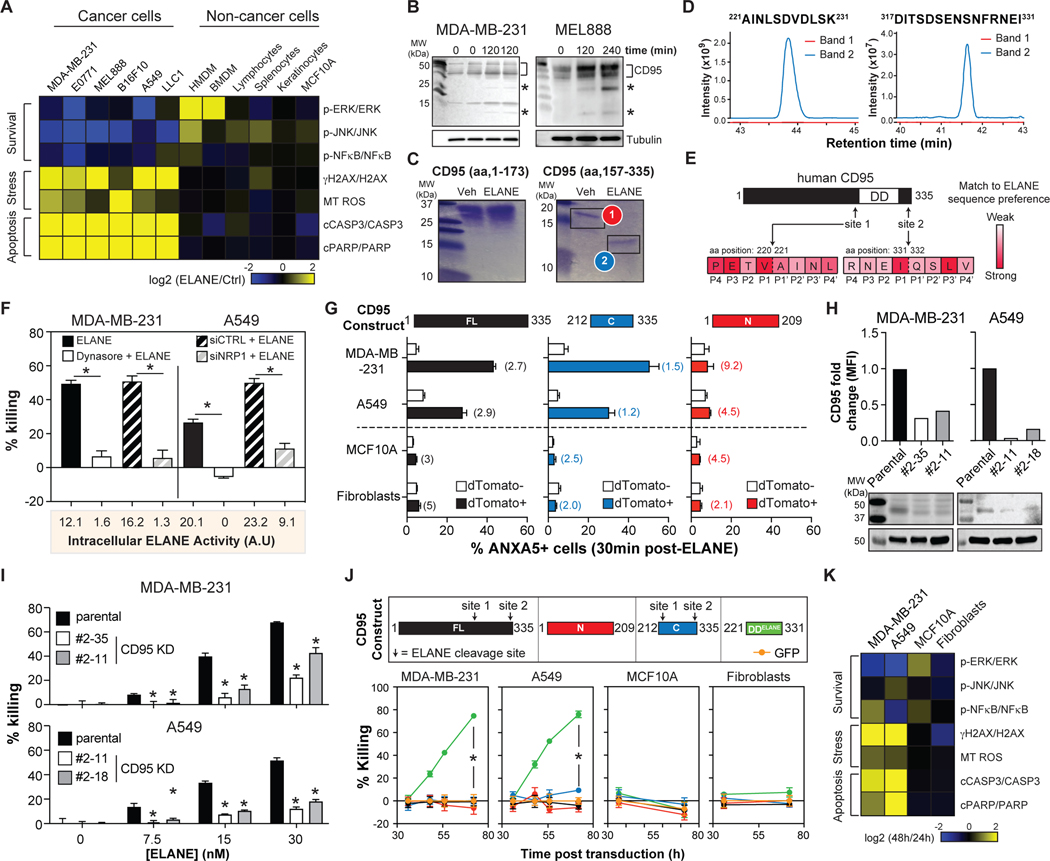

ELANE kills cancer cells by proteolytically liberating the CD95 death domain

To investigate how ELANE kills cancer cells, we studied its effects on signaling pathways linked to survival/apoptosis in cancer and non-cancer cells. ELANE induced a complex killing program in all murine and human cancer cells tested, but not in any non-cancer cells tested. This program was characterized by suppression of survival pathways (decreased phosphorylation of ERK, JNK, and NFκB), induction of DNA damage (increased γH2AX), elevated mitochondrial ROS production, and activation of effectors of apoptosis (increased cleaved PARP and CASP3) (Figures 4A, S3). Previous studies showed that lowering CD95 with shRNA mimicked ELANE’s complex killing program resulting in selective cancer cell killing (Chen et al., 2010). We therefore investigated the role CD95 in ELANE-mediated killing.

Figure. 4. ELANE cleaves CD95 to selectively kill cancer cells.

(A) Heatmap of ELANE’s (3μg/mL) effects on survival, stress, and apoptosis pathways in cancer and non-cancer cells. See also Figure S3 for raw data and quantification.

(B) Effect of ELANE (3μg/mL) on CD95 cleavage in cancer cells assessed by immunoblotting using anti-C-terminal CD95 antibody. *, CD95 fragment.

(C) Cleavage of the N-terminal or C-terminal domains of recombinant human CD95 by ELANE was assessed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. Veh = PBS.

(D) Bands from (C) were analyzed by mass spectrometry to identify ELANE cleavage sites (ie. non-tryptic peptides).

(E) Schematic of ELANE cleavage sites in human CD95. Heatmap shows overlap to ELANE’s sequence specificity (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/merops).

(F) Effect of Dynasore (60μM, 30min), control siRNA (siCTRL) or NRP1 siRNA (siNRP1) on MDA-MB-231 and A549 cell viability (calcein) following treatment with ELANE (1.2μg/mL, 4h); n=6/group. ELANE uptake was quantified by catalytic activity in cell lysates 30min post ELANE treatment and presented below.

(G) Cells transduced with various human CD95 constructs (with dTomato) were treated with ELANE (3μg/mL, 30min). Apoptosis was quantified by ANXA5 staining on dTomato+ and dTomato- populations. Flow cytometric analysis of CD95 expression levels in dTomato+ versus dTomato- cells 48h post-transduction (fold-change in parentheses). n=2/group.

(H) CRISPR knockdown (KD) of CD95 in MDA-MB-231 and A549 cells was measured by flow cytometry (top) and immunoblotting (bottom).

(I) Effects of ELANE (6h) on parental or CD95 KD colony viability (calcein-AM); n=6/group

(J) Cells were transduced to express various human CD95 constructs or GFP (top). Cell viability was determined by calcein-AM; n=10/group (bottom). See also Figures S5A–B.

(K) Heatmap of the effects DDELANE expression on survival, stress, and apoptosis pathways in cancer and non-cancer cells. See also Figures S5 for raw data and quantification.

*, p<0.05 Student’s t-test, data are mean ± SEM.

To begin, we determined if ELANE cleaves CD95 in cancer cells. We treated cancer cells with ELANE and observed lower molecular weight CD95 bands (Figure 4B). To identify cleavage sites in human CD95, we incubated ELANE with recombinant proteins corresponding to its N-terminal (aa 1–173) or C-terminal (aa 157–335) domains. ELANE preferentially cleaved the C-terminal domain (Figure 4C). Mass spectrometry identified two major cleavage sites in human CD95 – site 1: V220-A221, site 2: I331-Q332, both of which mapped well to ELANE’s sequence specificity (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/merops) (Figures 4D–E, S4A). Cleavage at both sites was further confirmed by incubating ELANE with synthetic peptides corresponding to aa 214–231 and aa 317–335 of human CD95 and monitoring degradation products by mass spectrometry (Figure S4B). Analysis of murine CD95 revealed the presence of analogous ELANE cleavage sites at comparable positions in the primary sequence (Figure S4C). Thus, ELANE cleavage of human CD95 liberates a C-terminal fragment containing its death domain (DD).

We reasoned that cancer cell killing by ELANE is dependent on CD95, and liberation of its DD. Three approaches were used to test this idea. First, because CD95 DD is intracellular, we determined if ELANE uptake is required for killing. Treatment with Dynasore (a broad endocytosis inhibitor) or siRNA for neuropilin 1 (NRP1), the receptor that mediates ELANE uptake by cancer cells (Mittendorf et al., 2012), attenuated ELANE uptake and protected cancer cells from ELANE (Figures 4F, S4D–F).

Second, we tested if altering CD95 levels could modulate the efficacy of ELANE-mediated killing. Overexpressing CD95 in human or murine cancer cells accelerated ELANE-mediated killing (Figures 4G, S4G–I), perhaps by providing more substrate for the reaction. And this effect was specific to cancer cells as overexpressing CD95 in non-cancer cells did not render these cells susceptible to ELANE (Figures 4G, S4G–I). Knocking down human CD95 in cancer cells with CRISPR protected them from ELANE-mediated killing (Figures 4H–I).

Third, we investigated if the human CD95 DD-containing fragment generated by ELANE proteolysis (DDELANE: aa 221–331) was sufficient to selectively kill cancer cells. We expressed DDELANE in human cancer cells and found that it killed them through an identical killing program as ELANE (Figures 4J–K, S5). In contrast expressing full-length human CD95 (FL-CD95) or an N-terminal domain lacking the DD (aa 1–209, N-CD95) had no effect on cancer cell survival (Figures 4J, S4G–I). Importantly, DDELANE was not toxic to all non-cancer cells tested, despite a similar level of overexpression (Figures 4J–K, S5A–B).

The toxicity of DDELANE to cancer cells could be mediated by special properties conferred by ELANE cleavage or simply by its liberation from the full-length protein and membrane. To differentiate between these possibilities, we expressed a C-terminal human CD95 construct with an additional 9 aa flanking site 1 and 4 aa flanking site 2 (C-CD95, aa 212–335). This construct liberates the DD from CD95 and excludes the transmembrane domain (aa. 174–190) but retains both ELANE cleavage sites. Although C-CD95 was unable to kill cancer cells in the absence of ELANE (Figure 4J), it accelerated ELANE-mediated killing – a result that mimicked overexpression of full-length CD95. This effect was specific because human C-CD95 did not lead to ELANE-mediated toxicity to non-cancer cells (Figures 4G, S4G–I).

Histone H1 isoforms contribute to ELANE’s selective toxicity to cancer cells

Our findings support a model wherein internalized ELANE cleaves CD95 to release DDELANE, which suppresses survival pathways, activates pro-apoptotic pathways, and selectively eliminates cancer cells. What is the molecular basis for ELANE’s selective toxicity to cancer cells? NRP1 (ELANE receptor) and CD95 (ELANE substrate) are comparably expressed by cancer and non-cancer cells (https://www.cancer.gov/tcga). And DDELANE (ELANE product) kills cancer, but not non-cancer cells. These findings suggest that the basis for selectivity lies downstream of ELANE uptake, substrate availability, and product generation. We reasoned that cancer cells express factor(s) that interact with DDELANE to drive apoptosis, and that these factor(s) are absent or minimally expressed by non-cancer cells.

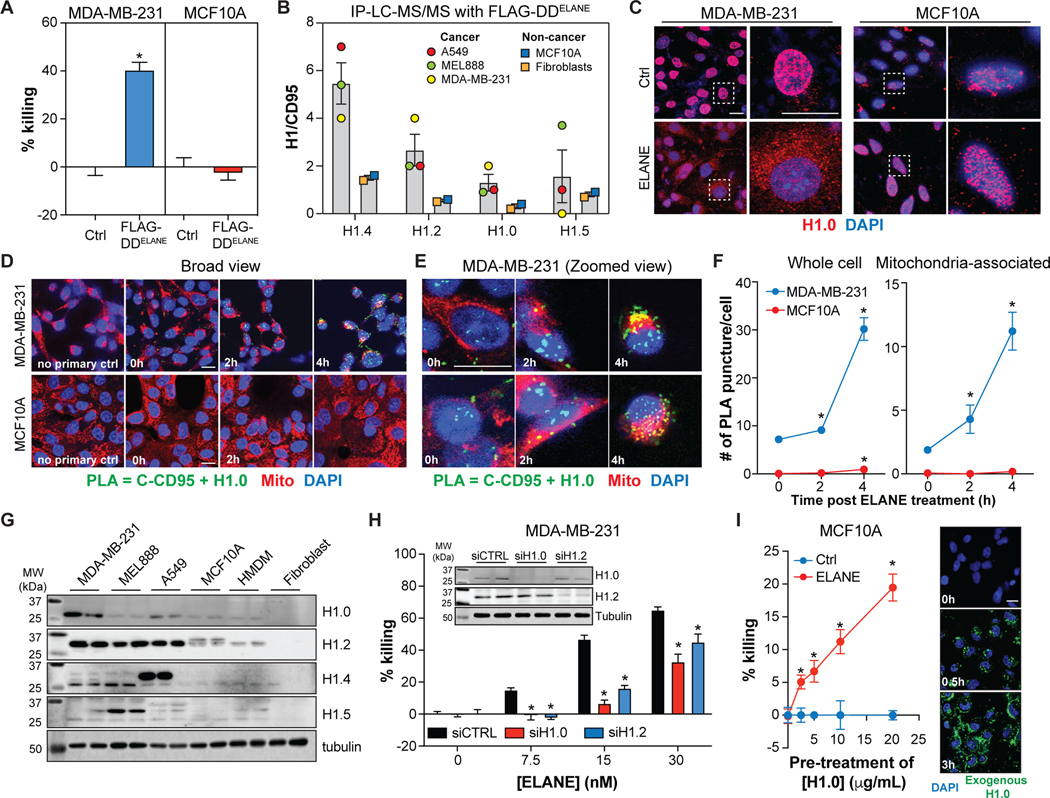

To explore this idea, we expressed FLAG-tagged DDELANE in cancer cells and non-cancer cells and performed IP mass spectrometry (IP-LC-MS/MS) to identify potential binding partners. We incorporated a FLAG tag because it allowed us to identify DDELANE-binding proteins without contamination from full-length CD95, and because introducing a FLAG-tag did not alter selective cancer cell killing by DDELANE (Figure 5A). IP-LC-MS/MS identified four histone H1 isoforms (H1.0, H1.2, H1.4, H1.5) that bound DDELANE in cancer but not non-cancer cells (Figure 5B, Table S4).

Figure 5. CD95-DDELANE interacts with histone H1 to selectively kill cancer cells.

(A) Effect of FLAG-DDELANE transduction on cancer and non-cancer cell viability (calcein-AM) 56h post-transduction; n=6/group (A).

(B) Proteomic quantification of H1 isoform levels in anti-FLAG co-immunoprecipitations (36h post-transduction). See also Table S4.

(C) Immunofluorescence of H1.0 (red) in MDA-MB-231 and MCF10A cells. Blue = DAPI.

(D-E) Proximity ligation assay (PLA) of CD95 and H1.0 in MDA-MB-231 and MCF10A following treatment with ELANE (1.5μg/mL). Representative images are shown at low (D) and high (E) magnification.

(F) Quantification of PLA signals in whole cells (left) and mitochondria (right). n=100 cells/group.

(G) Immunoblotting of histone H1 isoforms in cancer and non-cancer cells.

(H) Effects of control (siCTRL), H1.0 (siH1.0), or H1.2 (siH1.2) siRNA on MDA-MB-231 cell viability (calcein-AM) following treatment with ELANE (1.5μg/mL, 6h); n=6/group. Inset: Immunoblots confirm H1.0 and H1.2 knockdown.

(I) Effects Alexa Fluor™488-labeled histone H1.0 pre-treatment (3h) on MCF10A cell viability (calcein-AM) following ELANE treatment (1.5μg/mL, 18h). n=6/group. Representative images of H1.0 uptake (20μg/mL) at various time points (right).

*, p<0.05 Student’s t-test, data are mean ± SEM. Scale bars = 20μm.

Previous studies showed that DNA damage induces histone H1 translocation from the nucleus to the mitochondria, leading to cytochrome c release and apoptosis of cancer cells (Konishi et al., 2003). Given that ELANE induces DNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction, and histone H1 isoforms were identified as DDELANE-binding proteins, we studied the dynamics and importance of histone H1. Treating MDA-MB-231 cells with ELANE caused rapid histone H1.0 translocation from the nucleus (Figures 5C, S3C). However, this translocation was not observed in MCF10A cells (Figure 5C). Proximity ligation assays (PLA) using anti-C-terminal CD95 and anti-H1.0 antibodies further showed that ELANE triggered CD95-H1.0 interactions in MDA-MB-231 cells, but not in MCF10A cells (Figures 5D–F). Interestingly, many of the PLA signals in MDA-MB-231 cells co-localized with mitochondria (Figures 5D–F), which may help to explain the mitochondrial ROS induced by ELANE.

Western blot analysis revealed that histone H1 isoforms are generally elevated in cancer versus non-cancer cells. H1.2 was up-regulated across all cancer cell types tested, while H1.0 (MDA-MB-231), H1.4 (A549), and H1.5 (MEL888) were elevated in specific cancer cell types (Figure 5G). These findings, which are in general agreement with previous studies (Sato et al., 2012; Scaffidi, 2016), suggest that differential histone H1 expression might underlie ELANE’s selective toxicity to cancer cells. We explored this possibility using two approaches. First, we knocked down histone H1.0 or H1.2 using siRNA and found that lowering H1 levels protected MDA-MB-231 cells from ELANE-mediated killing (Figure 5H). Second, we treated MCF10A cells with exogenous recombinant H1.0, which was internalized and primarily localized in the cytosol (Figure 5I). Although H1.0 failed to kill MCF10A cells on its own, it made them susceptible to ELANE-mediated killing, albeit with lower efficacy than in cancer cells (Figure 5I). Together, these findings suggest that differential expression of histone H1 isoforms contributes to ELANE’s selective toxicity to cancer cells.

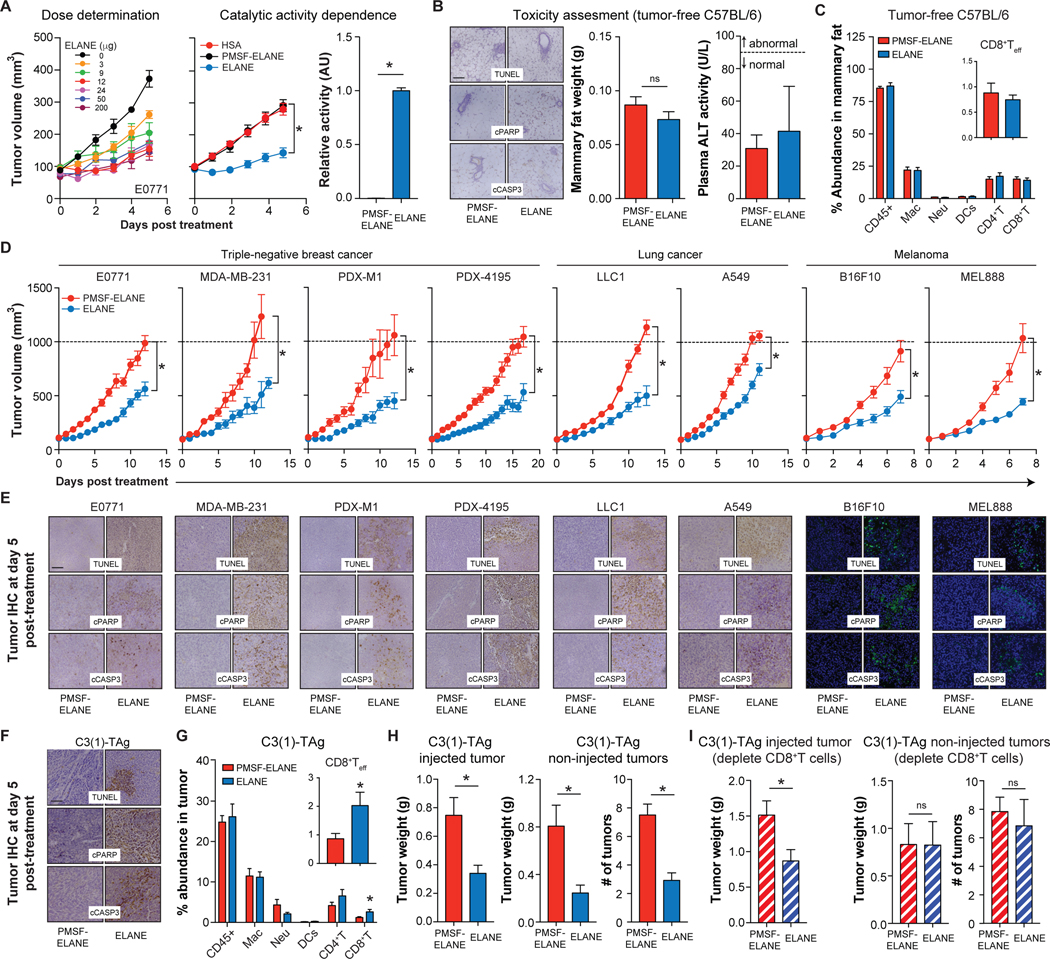

ELANE attenuates tumor growth and induces a CD8+ T cell mediated abscopal effect

To determine if ELANE selectively kills cancer cells and attenuates tumor growth in vivo, we injected it at various doses into E0771 tumors (TNBC). ELANE inhibited tumor growth at all doses tested, and its therapeutic benefit was eliminated with PMSF inactivation (Figure 6A). Importantly, injecting ELANE (12μg/day, 5 days) into mammary fat of tumor-free C57BL/6 mice (TNBC control) did not induce apoptosis or lower fat mass at the injection site, nor did it affect liver function (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. ELANE attenuates tumor growth and induces a CD8+ T cell-mediated abscopal effect.

(A) E0771 tumor growth following intertumoral injection of ELANE (left, dose/day, 5 days, n=3–5/group) or HSA, PMSF-ELANE, or ELANE (middle, 12μg/day, 5 days; n=10–17/group). Inactivation of ELANE by PMSF was confirmed by activity assays (right, n=3/group).

(B-C) PMSF-ELANE or ELANE (12 μg/day, 5 days) were injected into mammary fat pads of tumor-free C57BL/6 mice. Mammary fat apoptosis markers (left, B) and weight (middle, B), plasma ALT activity (right, B), and immune cell profiles (C) were measured one day after the final ELANE treatment. n=5–6/group.

(D) Murine or human cancer cells were orthotopically injected into the mammary fat pad (TNBC models) or flank (melanoma and lung models). PMSF-ELANE or ELANE (12 μg/day, 5 days) were injected intratumorally and tumor volume was monitored. n=8–16/group.

(E) Representative IHC images of TUNEL, cPARP, and cCASP3 staining on tumors isolated one day after the final ELANE treatment.

(F-H) ELANE or PMSF-ELANE (12 μg/day, 5 days) was injected into the first palpable tumor of C3(1)-TAg mice. Tumor apoptosis (F) and immune cell composition (G) was quantified 1 day following the final ELANE treatment; n=9/group. The weight of the injected tumor (left, H), and the total weight and number of non-injected tumors (middle and right, H) were measured. n=11/group.

(I) Effect of depleting CD8+ T cells on ELANE’s efficacy in injected (left) and non-injected (middle, right) tumors in the C3(1)-TAg model; n=6/group. See also Figure S6.

*, p<0.05 Student’s t-test, data are mean ± SEM. Scale bars = 100μm.

We next explored the therapeutic potential of intratumorally-delivered ELANE in syngeneic, xenograft, and PDX models of TNBC (E0771, MDA-MB-231, PDX-M1, PDX-4195), lung cancer (LLC1, A549), and melanoma (B16F10, MEL888). ELANE attenuated tumor growth in all models tested (Figure 6D). Immunohistochemistry showed an increase in TUNEL, cPARP, and cCASP3 staining in all ELANE-treated tumors (Figure 6E), suggesting that ELANE’s anti-cancer action was on-target.

Notably, ELANE therapy produced a curious “tumor crater” in ~40% of mice across all immunocompetent models tested (Figure S6O). Craters were not observed in tumor-free C57BL/6 mice or in tumor-bearing immunocompromised mice (Figure S6O). These data suggest that ELANE-mediated cancer cell killing combined with a functional adaptive immune response create a crater in the tumor. However, mechanisms underlying crater development and its importance for therapeutic efficacy require further investigation.

Because ELANE kills cancer cells but not immune cells, we hypothesized that this selective killing might liberate antigens to increase/activate immune cells in vivo. Indeed, previous studies showed that ELANE uptake by breast cancer cells enhances antigen presentation to activate cytotoxic T cells (Chawla et al., 2016; Kerros et al., 2017). To test this, we delivered ELANE intratumorally in two immunocompetent syngeneic mouse models. We observed increased tumor dendritic cells (DCs), CD8+ T cells, and CD8+ T effector cells (CD8+ Teff) following ELANE treatment in both models (Figures S6A, D). Immune cells were not increased when ELANE was injected into mammary fat of tumor-free mice (Figures 6C, S6B), or into contralateral mammary fat (ie. opposite the tumor) of E0771 tumor-bearing mice (Figures 6C, E), where it failed to attenuate tumorigenesis (Figures S6K–L). Thus, the immune cell induction was not due to an immune reaction to human ELANE.

Next, we investigated if treating a primary tumor with ELANE could decrease tumorigenesis at distant sites through CD8+ T cells, a property referred to as the abscopal effect (Ngwa et al., 2018). We tested this in two syngeneic models: 1) a TNBC model in which E0771 cells were injected into the left (1o tumor) and right (2o tumor) mammary fat pads, and 2) a melanoma model in which B16F10 cells were injected into the flank (1o tumor) and intravenously to create 2o lung tumors. In both models, we treated the 1o tumor with ELANE once/day for 5 days and measured tumor growth at both sites.

Treating the 1o tumor with ELANE attenuated tumor growth at the injected and distant sites in both models (Figures S6G–J). This effect was not due to ELANE spillover from the 1o tumor since injecting ELANE into contralateral mammary fat (ie. opposite the tumor) failed to diminish E0771 tumor growth (Figures S6K–L). This abscopal effect was also specific since tumor growth in a genetically distinct 2o B16F10 tumor was unaffected by treatment of a 1o E0771 tumor with ELANE (Figures S6M–N). To examine the dependence of this abscopal effect on CD8+ T cells, we repeated this experiment in mice where CD8+ T cells were depleted prior to and following ELANE treatment. Results showed that depleting CD8+ T cells attenuated ELANE’s abscopal effect in both models (Figures S6F–J).

We further investigated if ELANE could induce a CD8+ T cell-mediated abscopal effect in a genetically engineered mouse (GEM) model, where tumors spontaneously and independent arise at multiple sites. We used the C3(1)-TAg GEM model of TNBC which shares many features with human TNBC patients (Green et al., 2000).

We injected the first palpable tumor with ELANE (12μg/day, 5 days) and monitored effects on injected and non-injected tumors until ~24 weeks of age. Consistent with our findings in syngeneic models, ELANE attenuated tumor growth, induced cancer cell apoptosis, and increased total and effector CD8+ T cells in injected tumors (Figures 6F–H). Moreover, ELANE decreased both the number and total weight of non-injected tumors (Figure 6H), and depleting CD8+ T cells eliminated this abscopal effect (Figure 6I). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that ELANE induces a CD8+ T-cell-mediated abscopal effect in multiple immunocompetent models.

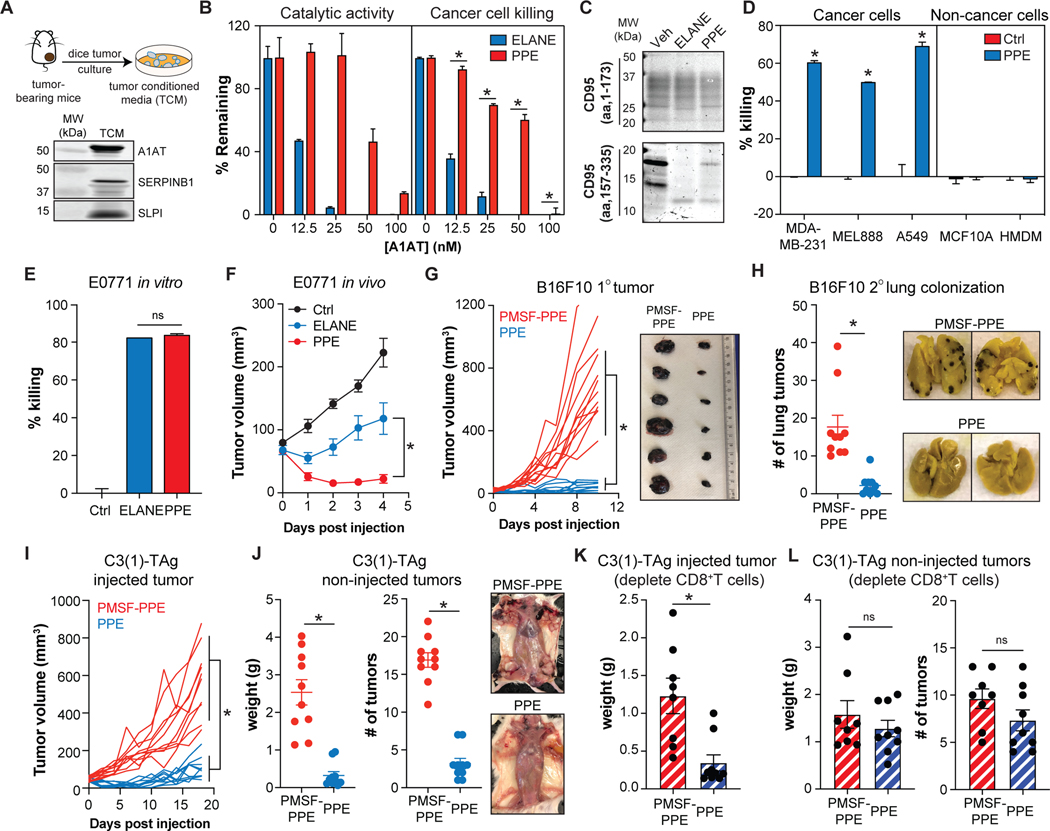

Serine protease inhibitors in the TME limit ELANE’s therapeutic efficacy

Although ELANE reduced tumor growth in all pre-clinical models tested, it’s efficacy in vivo was limited in comparison to its strong potency in vitro. We sought to understand the molecular basis of this discrepancy. Given that ELANE’s anti-cancer function requires catalytic activity and cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME) secrete serine protease inhibitors (Chang et al., 2012; Dudani et al., 2018), we tested the possibility that serine protease inhibitors in the TME limit ELANE’s efficacy in vivo. We collected tumor conditioned media (TCM) from E0771 tumors in organ culture and identified several serine protease inhibitors including alpha-1-antitrypsin (A1AT), secretory leukocyte peptidase inhibitor (SLPI), and serpin family B member 1 (SERPINB1) (Figure 7A). TCM potently antagonized ELANE’s catalytic activity and cancer cell killing capability in a dose-dependent manner (Figure S7A), and similar findings were obtained with purified A1AT (Figure 7B). These findings suggest that serine protease inhibitors in the TME might serve as a barrier to ELANE’s anti-tumor action.

Figure. 7. PPE resists serine protease inhibition and has improved therapeutic efficacy.

(A) Schematic for collecting E0771 tumor conditioned media (TCM) in serum-free DMEM for 24h. Serine protease inhibitors in the TCM were identified by immunoblotting.

(B) Effects of purified A1AT (0–100nM) on ELANE and PPE (40nM) catalytic activity (n=2/group) and MDA-MB-231 cancer cell viability (calcein-AM) (n=4/group).

(C) Cleavage of human CD95 N-or C-terminal recombinant proteins by ELANE or PPE was assessed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining.

(D) Effect of PPE (3μg/mL, 6h) on cancer and non-cancer cell viability (calcein-AM); n=3–6/group.

(E) Effects of PPE or ELANE (0.12 units of enzyme activity) on E0771 cell viability under serum-free conditions (calcein-AM); n=3/group.

(F) Effects of intratumorally injected ELANE or PPE (10 units/day for 5 and 2 days respectively) on E0771 tumor growth; n=5–6/group.

(G-H) Effects of PPE (intratumoral, 10units/day, 2 days) on the injected (G) and non-injected (H) tumors in the B16F10 model with lung colonization; n=10/group.

(I-J) Effects of PPE (intratumoral, 10units/day, 2 days) on the injected (I) and non-injected (J) tumors in the C3(1)-TAg model; n=10/group.

(K-L) Effect of depleting CD8+ T cells on PPE’s efficacy in injected (K) and non-injected (L) tumors in the C3(1)-TAg model; n=8–9/group. See also Figure S6.

*, p<0.05 Student’s t-test, data are mean ± SEM.

PPE resists serine protease inhibition and exhibits improved therapeutic efficacy.

Previous studies showed that porcine pancreatic elastase (PPE), an ELANE homolog with ~32% amino acid identity, has a differential susceptibility to inhibition despite a similar protein structure and primary substrate specificity (Bode et al., 1989; Kraunsoe et al., 1996; Ortwerth et al., 1994). We reasoned that PPE might be less susceptible to serine protease inhibition, which in turn, would increase its therapeutic efficacy. Similar to ELANE, PPE preferentially cleaved the C-terminal CD95 domain with a comparable degradation pattern (Figure 7C) and selectively killed cancer cells (Figure 7D). In the presence of TCM or A1AT, PPE showed significantly improved cancer cell killing which associated with resistance to serine protease inhibition of its catalytic activity (Figures 7B, S7A).

We further determined if PPE had improved therapeutic efficacy in vivo. To begin, we injected ELANE and PPE (standardized by units of activity) into E0771 tumors and found that PPE had improved efficacy despite a similar ability to kill E0771 cells in vitro in the absence of serine protease inhibitors (Figures 7E–F). Injecting PPE into mammary fat of tumor-free C57BL/6 mice (TNBC control) did not induce apoptosis or lower fat mass at the injection site, nor did it affect body weight, spleen weight, or liver function (Figures S7B–E).

Because PPE immediately lowered tumor volume after the first injection, we limited therapeutic dosing to 1 injection/day for 2 days. We explored PPE’s efficacy in the 1o tumor and at distant sites in the B16F10 model with lung colonization and the C3(1)-TAg GEM model. Results showed that 2 intratumoral injections of PPE into the 1o tumor had markedly improved potency in the 1o tumor and in lessening distant tumors in both models (Figures 7G–J). Similar to what we observed with ELANE, depleting CD8+ T cells, eliminated PPE’s abscopal effect in the C3(1)-TAg model (Figures 7K–L). Thus, by conferring protection from serine protease inhibitors, PPE improves upon the therapeutic efficacy of ELANE.

DISCUSSION

Given that human PMNs release extracellular factors that kill a wide range of pathogens, we sought to explore whether these factors have a similar ability to kill cancer cells. Using this strategy, we i) identified ELANE as the major anti-cancer protein released by human PMNs, ii) uncovered differences between human and murine neutrophils in releasing catalytically active ELANE extracellularly, iii) deciphered that its mechanism of action involves cleaving CD95 at V220/A221 and I331/Q332 to liberate a DD-containing proteolytic fragment that interacts with histone H1 isoforms to selectively kill cancer cells, iv) demonstrated ELANE’s broad anti-cancer efficacy and selectivity in multiple pre-clinical models, and v) showed that PPE, an ELANE homolog that is less sensitive to serine protease inhibitors, has markedly improved therapeutic efficacy.

On a molecular level, we show that ELANE’s therapeutic properties stem from its ability to proteolytically liberate the CD95 death domain-containing fragment (DDELANE), which our studies show is sufficient to kill cancer cells through a gain-of-function mechanism. This gain-of-function is not simply due to liberating the DD from full-length CD95, since expressing a C-terminal DD-containing construct with 9 aa flanking cleavage site 1 and 4 aa flanking cleavage site 2 could only accelerate ELANE-mediated killing and could not kill cancer cells on its own. We speculate that these 13 aa contain inhibitory sequences and/or alter the conformation of the DD to prevent cancer cell apoptosis, and therefore require removal by ELANE. Previous studies support this model. For example, the CD95 DD adopts a closed conformation that prohibits binding of pro-apoptotic factors and self-elimination. An I313D mutation in CD95 opens its DD conformation to enable binding to pro-apoptotic factors resulting in cancer cell death in the presence and absence of external triggers (Scott et al., 2009). In addition, deleting three amino acids from the C-terminus of CD95 (which closely mimics ELANE cleavage at site 2) abrogates its interaction with the anti-apoptotic factor PTPL1, and sensitizes cancer cells to apoptosis (Ungefroren et al., 2001).

A major outstanding question is what forms the molecular basis for ELANE’s selective toxicity to cancer cells? We provide evidence that this selectivity is due in part to the interaction of DDELANE with histone H1 isoforms. Previous studies showed that in response to DNA damage, histone H1 translocates from the nucleus to the mitochondria, resulting in mitochondrial damage and apoptosis of cancer cells (Yan and Shi, 2003). Consistent with this study, we showed that ELANE induces DNA damage in cancer cells and H1.0 translocates into the cytoplasm where it binds DDELANE and subsequently co-localizes with mitochondria. In contrast, we found minimal evidence of these events following ELANE treatment of non-cancer cells. We posit that this difference is due to elevated levels of histone H1 isoforms in cancer versus non-cancer cells (Sato et al., 2012; Scaffidi, 2016), which may be important for regulating chromatin structure and promoting DNA repair during genotoxic stress (Misteli et al., 2000; Thorslund et al., 2015). Future studies aimed at understanding events triggering histone H1 translocation, the kinetics and stoichiometry of histone H1 and DDELANE complexes, and the mechanism by which these complexes promote apoptosis will be required to fully characterize the selective anti-cancer pathway triggered by ELANE.

Intratumorally delivered ELANE has several intriguing properties in pre-clinical models. First, its ability to kill a wide range of cancer cells may enable its implementation without knowledge of their genetics. Indeed, we demonstrate ELANE efficacy in 9 models spanning TNBC, melanoma, and lung cancer. Second, its specificity for cancer versus non-cancer cells may limit potential toxicity, a possibility that is strengthened by the lack of side effects observed in tumor-free mice injected with ELANE. This selective killing also preserves immune cells, allowing them to capitalize on liberated antigens and generate an adaptive immune response that extends efficacy to metastatic sites. This combination of therapeutic properties differentiates ELANE from other anti-cancer modalities.

The dependency of ELANE’s anti-cancer properties on its catalytic activity has important physiological and therapeutic implications. From a physiological perspective, we show that unlike human neutrophils, murine neutrophils release ELANE in a catalytically inactive form by co-releasing the serine protease inhibitor SLPI, which is absent in human neutrophils. This species difference in ELANE biology adds to the growing list of differential functional properties between human and murine neutrophils (Eruslanov et al., 2017), which may in part help to conceptualize their contentious roles in tumor development (Coffelt et al., 2016; Fridlender et al., 2009). It also suggests that previous studies of Elane−/− mice may require re-interpretation. For example, Elane−/− mice have diminished tumor growth (Houghton et al., 2010), suggesting that ELANE promotes tumorigenesis. However, we provide unequivocal evidence that ELANE kills cancer cells and opposes tumor development when injected intratumorally. Based on the inability of murine neutrophils to release catalytically active ELANE it is possible that these previously reported effects are due to changes in neutrophil biology due to loss of ELANE. Indeed, Elane−/− neutrophils have altered ability to migrate to inflammatory sites and respond to inflammatory challenges (Colom et al., 2015; Kessenbrock et al., 2008), both of which could impact tumor development through a mechanism independent of ELANE’s paracrine effects.

From a therapeutic perspective, the reliance of ELANE’s anti-cancer properties on catalytic activity and the abundance of serine protease inhibitors in blood restrict therapeutic delivery to the intratumoral route. Although this restriction would protect against potential toxicity due to ELANE/PPE spillover from the tumor (Fricker et al., 2014), it poses a roadblock to accessing metastatic sites. However, we show that ELANE can overcome this by creating a specific CD8+ T cell response that attacks distant tumors in mice with functional immune systems. Moreover, our demonstration of abscopal effects in a C3(1)-TAg GEM model, where genetically similar tumors arise independently and spontaneously in different mammary glands, raises the possibility of implementing ELANE therapy as an in-situ vaccination.

Serine protease inhibitors also limit therapeutic efficacy in the primary tumor. Because the TME contains many serine protease inhibitors (Chang et al., 2012; Dudani et al., 2018), albeit at lower levels than in blood, ELANE’s catalytic activity can be inactivated resulting in protection for cancer cells. Our findings demonstrate that a porcine-derived ELANE homolog (PPE) partially overcomes this barrier. PPE mimics ELANE in terms of its ability to cleave CD95 and selectively kill cancer cells. However, because PPE is more resistant to serine protease inhibition, its catalytic activity is preserved within the TME and its anti-cancer potency is markedly improved. Indeed, we showed that 2 intratumoral injections of PPE is sufficient to immediately shrink the primary tumor and produce a more powerful CD8+ T cell-mediated abscopal effect resulting in durable responses in a subset of mice.

Collectively, our findings suggest that the proteolytic liberation of the CD95 DD domain by ELANE/PPE eliminates genetically heterogenous cancer cells while sparing host cells. In addition to dissecting mechanisms downstream of CD95 DD liberation and histone H1 binding that underly this selective anti-cancer pathway, future studies aimed at maximizing the therapeutic efficacy of ELANE/PPE, both as a monotherapy and in combination with other therapeutic modalities, are warranted.

Limitations of the study

First, although our findings demonstrate that human PMN media kills 35 cancer cell types, this was shown with calcein-AM, which does not implicate a specific mechanism. For feasibility, we showed that PMN media kills 6 of these cell types (MDA-MB-231, E0771, MEL888, B16F10, A549, LLC1) via apoptosis. Similarly, ELANE’s ability to induce apoptosis and its mechanism of action were deciphered using these same 6 cell types. Accordingly, it is possible that other killing mechanisms could be involved in other cell types. Second, although our findings suggest that histone H1 isoforms contribute to selective cancer cell killing by ELANE, we mainly used H1.0 (and H1.2) to demonstrate this due to material availability. Thus, studies with other histone isoforms are warranted. Third, while our studies show that ELANE does not induce toxicity to 6 different sources of non-cancer cells (mostly primary human and mouse), extrapolation to other non-cancer cell types requires experimental validation.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Lev Becker (levb@uchicago.edu)

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

The proteomics data generated during this study are provided in Supplementary Tables.

EXPERIMENTAL MODELS AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Mice

Mouse studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUP72209, 72504) at the University of Chicago. 6–7 week old C57BL/6 mice, NOD.SCID mice, Elane−/−, Slpi−/− mice, C3T(1)-TAg mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. 6–7 week old athymic nude mice were purchased from Charles River. MMTV-PyMT mice were gifted from Dr. Geoffrey Greene, University of Chicago. Mice were housed in the animal facility at the Gordon Center for Integrative Science building at the University of Chicago. Female mice were used for all cancer models and associated controls (ie. tumor-free). Both male and female mice were used for isolation of primary cells, including neutrophils, macrophages, splenocytes, and keratinocytes.

Cell lines and Culture Conditions

Cancer cell lines and viral studies were approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC1503). The ovarian cancer cell lines – CaoV3, OVCAR3, OVCAR4, OVCAR5, A2780, A2780/CP70, HeyA8, TykNu, SKOV3, ID8, and ID8 p53−/− were a gift from Dr. Ernst Lengyel, University of Chicago. The breast cancer cell lines – MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-231.BM1, MCF-7, M6C, E0771, and E0771.LMB were a gift from Dr. Marsha Rosner, University of Chicago. The colon carcinoma cell line RKO, glioblastoma cancer cell line T98G, osteosarcoma cell lines U-2OS and Saos-2, and the hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG2 were a gift from Dr. Kay MacLeod, University of Chicago. The lung cancer cell line NCI-H552 was a gift from Dr. Stephanie Huang, University of Chicago, and A549 and LLC1 cells were purchased from ATTC. The melanoma cell lines – B16F10, MEL888, MEL1106, and SK-MEL-28 cells were a gift from Dr. Thomas Gajewski, University of Chicago. The pancreatic cancer cell line PANC1 was a gift from Dr. Yamuna Krishnan, University of Chicago. The leukemia cell line K562 was a gift from Dr. Amittha Wickrema, University of Chicago. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Medium (DMEM; HyClone) containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Gemini Bio Products) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (ThermoFisher Scientific). The prostate cancer cell lines – CWR22Rv1, LAPC4, and LNCaP were a gift from Dr. Donald Vander Griend, University of Chicago. The neuroblastoma cell lines – SK-N-BE(2) and NBL-WN cells were a gift from Dr. Lucy Godley, University of Chicago. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 media (Hyclone) containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Gemini Bio Products) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). The mammary gland epithelial cell line MCF10A was purchased from ATCC. Cells were cultured in DMEM/F10 (Invitrogen) containing 5% horse serum FBS (Invitrogen), 20ng/mL EGF (Peprotech), 0.5μg/ml hydrocortisone (Sigma), 100ng/mL cholera toxin (Sigma), 10μg/mL insulin (Sigma), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco).

Human Samples

Human studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Chicago (IRB160321, IRB13372B). Blood was obtained from both male and female healthy donors, while omental adipose tissue neutrophils (ONs) and tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) were obtained from female patients. ONs were obtained from patients undergoing surgery for benign conditions; pre-metastatic ONs were obtained from ovarian cancer patients diagnosed at early-stage IA-IC according to International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) classification. Omental TANs were obtained from ovarian cancer patients diagnosed at FIGO stage III-IV, metastatic ovarian cancer. Patient demographics for neutrophil isolation and quantification are shown in Table S1.

METHOD DETAILS

Primary human blood-derived cells

Blood was collected from healthy volunteers (IRB160321) into EDTA-coated collection tubes (BD Vacutainer), and cells were separated with Ficoll Paque Plus (GE Healthcare) to obtain a buffy coat (containing monocytes and lymphocytes) and a bottom layer (containing neutrophils and red blood cells).

Human blood polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) –

PMNs were purified as previously described (Kuhns et al. 2015). Briefly, cells from the bottom layer were treated with RBC lysis buffer (10min/treatment, 2 treatments, 50mL RBC lysis buffer per 5mL blood cell equivalent). Cells were centrifuged at 500xg for 5 min in between steps. Cells were resuspended into phenol red-free, serum-free DMEM, counted, and purity was assessed by flow cytometry.

Human monocyte-derived macrophages (HMDMs) –

Monocytes were purified and differentiated into HMDMs as previously described (Kratz et al. 2014). In brief, monocytes were purified from the buffy coat using CD14 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Monocytes were differentiated into HMDMs by culturing in RPMI containing 10%FBS supplemented with M-CSF (125ng/mL, R&D Systems), with fresh media replacement every other day until day 7.

Human Lymphocytes –

Human lymphocytes were isolated from the buffy coat by collecting the flow through from CD14 and CD16 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec).

Primary human omental adipose tissue-derived cells

Human omental adipose tissue neutrophils (ONs) –

Omental tissue was digested with Type 1 Collagenase (1mg/mL, Worthington) in 1%BSA/PBS at 37oC with horizontal shaking at 130rpm for 75min to obtain stromal vascular cells (SVC). SVCs were filtered through 100μm filter (ThermoFisher Scientific), incubated in RBC lysis buffer for 5 min, and passed through a 40μm filter (ThermoFisher Scientific). ONs were isolated using CD16 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Purity was assessed by flow cytometry. Cells were centrifuged at 500xg for 5 min in between steps.

Human omental tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) –

Omental tumor was digested with Type 2 Collagenase (2mg/mL, Worthington) and Hyaluronidase (Sigma, 1.5mg/mL) 1%BSA/PBS at 37oC with horizontal shaking at 130rpm for 75min. Cells were filtered through 100μm filter (ThermoFisher Scientific), incubated in RBC lysis buffer for 5 min, and passed through a 40μm filter (ThermoFisher Scientific). TANs were isolated using CD16 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Purity was assessed by flow cytometry. Cells were centrifuged at 500xg for 5 min in between steps.

Human omental fibroblasts –

Human primary fibroblasts were isolated from omental adipose tissue as previously described (Kenny et al. 2007). In brief, omental adipose tissue was minced and incubated on an orbital shaker with 0.125% trypsin/12.5mM EDTA at 37oC for 30min. Tissue was further digested with hyaluronidase (Sigma, 100U) and Collagenase type 3 (Worthington, 1000U) at 37oC for 6h. Undigested tissue was discarded and solution containing cells was centrifuged at 1500rpm for 5min. Fibroblasts were cultured in DMEM (HyClone) containing 20% heat-inactivated FBS (Gemini Bio Products) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco).

Primary mouse cells

Murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) –

BMDMs were differentiated as previously described (Kratz et al., 2014). In brief, bone marrow cells were isolated from C57BL/6 mice and plated in 30% L-cell conditioned media (day 0), with fresh media replacement on days 3, 5, and 7.

Mouse splenocytes –

A murine spleen was mashed using a cell strainer (Celltreat) on a 70μm filter (ThermoFisher Scientific), incubated in RBC lysis buffer for 5min, and passed through a 40μm filter (ThermoFisher Scientific). Cells were centrifuged at 500xg for 5 min in between steps.

Mouse primary keratinocytes –

Mouse primary keratinocytes were isolated as previously described (Wu et al. 2008). In brief, primary mouse keratinocytes were isolated from the epidermis of newborn mice using trypsin, after prior separation of the epidermis from the dermis by an overnight dispase treatment. Keratinocytes were plated on mitomycin C-treated 3T3 fibroblast feeder cells until passage 3. Cells were cultured in E-low calcium media (0.05mM Ca2+) supplemented with 15% heat-inactivated FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

Murine bone marrow-derived neutrophils (BMDNs) –

BMDNs were purified as previously described (Swamydas et al. 2015). In brief, bone marrow cells were resuspended in 1mL of ice-cold PBS and layered on top of a pre-layered solution of Histopaque 1119 (3mL, 11191, Sigma) on the bottom and Histopaque 1077 (3mL, 10771, Sigma) on top. Cells were centrifuged at 500xg for 30min at room temperature without deceleration. BMDNs were collected at the interface of the Histopaque layers, and purity was assessed by flow cytometry. For PMA activation, BMDNs were treated with PMA (100nM, Abcam) for 15min, washed, and cultured for conditioned media collection.

Murine thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal neutrophils (PNs) –

PNs were isolated as previously described (Swamydas et al. 2015). In brief, mice were injected with 4% thioglycolate (3mL/mouse, Sigma). 7h-post injection, PNs were lavaged from the peritoneal cavity with 10mL of PBS, and purity was assessed by flow cytometry.

Murine tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) –

E0771 cells were injected into the mammary fat pad of C57BL/6 mice. When tumor volume reached ~500mm3, tumors were digested with Type 4 Collagenase (Worthington, 3mg/mL) and hyaluronidases (Sigma, 1.5mg/mL) in 1%BSA/PBS at 37oC with horizontal shaking at 200rpm for 45min. Digested tissue was passed through 100μm filter (ThermoFisher Scientific), incubated in RBC lysis buffer for 5 min, passed through a 40μm filter (ThermoFisher Scientific), and purified with Ly6G microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were centrifuged at 500xg for 5 min in between steps.

Murine lung neutrophils (LNs)–

Murine lung was isolated and digested with Liberase TM (0.2mg/mL, Roche) and DNAseI (40μg/mL, Sigma) 1%BSA/PBS at 37oC with horizontal shaking at 200rpm for 40min. Digested tissue was passed through a 70μm filter (ThermoFisher Scientific), incubated in RBC lysis buffer for 5 min, passed through a 40μm filter (ThermoFisher Scientific), and purified with the Ly6G microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were centrifuged at 500xg for 5 min in between steps.

Neutrophil media collection

Freshly isolated human or murine neutrophils were plated at 1 million cells/600μL serum-free DMEM for 24h. Conditioned media was collected, centrifuged at 500xg for 5min, and media protein levels were determined with a Bradford assay (Biorad): typically 30μg/mL. Control media is serum-free DMEM. Murine neutrophil media was collected in the presence 50ug/mL deoxyribonuclease I (D4513, Sigma).

PMN media manipulations

For in vivo studies, PMN or BMDN media was concentrated using a 3kDa cutoff centricon (Millipore) and 50μg/100μL was intratumorally injected. For boiling, PMN media was boiled at 95oC for 5min and centrifuged at 15,000xg for 10min to remove denautred proteins. For dialysis, PMN media was placed into a Slide-a-Lyzer™ cassette (3.5kDa cutoff, ThermoFisher Scientific) and dialyzed against 2×4L of PBS at 4oC for 4h. For size exclusion, PMN media was filtered through a 3kDa cutoff centricon (Millipore). For PMSF-inactivation, PMN media was treated with PMSF (1mM, Sigma) or A1AT (42nM, Athens Research & Technology) and incubated at room temperature for up to 2h. Residual PMSF was eliminated with a PD-10 desalting column (GE Healthcare Life). Inhibition of ELANE catalytic activity was confirmed using a chromogenic substrate activity assay (see below). For serum-spiking experiments, human, mouse, or fetal bovine serum (1% or 10%) was added to PMN media prior to or after exposing cancer cells. For immunodepletion studies, ELANE or ECP were immunoprecipitated using anti-ELANE (N2C3, GeneTx) or anti-ECP (MBS2535165, MyBioSource) antibodies coupled to Pierce™ Protein A/G Magnetic Beads (ThermoFisher Scientific).

In vitro cell viability assays

Cancer cells or non-cancer cells were plated in complete growth media and grown to 80–90% confluence. Cells were washed with serum-free DMEM, treated with various therapeutic agents (eg. PMN media, ELANE, etc.) for 4–24h, and cell viability was assessed using several methods:

Calcein-AM assay.

4–24h after treatment, cells were incubated with calcein-AM (ThermoFisher Scientific, 4ng/mL), washed with serum-free DMEM, and fluorescence was measured at 495nm/516nm using a Synergy HT Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Biotek).

CASP3 activity assay –

Cell-associated CASP3 activity was measured 6h after treatment using the Caspase-Glo® 3/7 Assay Systems (Promega). Luminescence was measured using a Victor X3 luminometer (PerkinElmer).

ANXA5/PI staining –

Cells were stained 30min-6h after treatment with the FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Pharmingen™) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were analyzed using a FACSCanto™ II flow cytometer (BD Pharmingen™).

Western blot analyses

Cells were lysed with 1% SDS containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma), and protein was quantified with the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce). Proteins (10–20μg) were resolved on SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore), blocked with either 5% BSA (Sigma) or 5% milk in 0.05% TBS/Tween-20 at RT for 2h, stained with primary and secondary antibodies, and visualized using the ECL detection kit (Biorad) and a LI-COR imager (Li-COR Biosciences).

Mitochondrial ROS measurements

Cells were treated with various doses of ELANE for 30min, washed, labeled with the CM-H2DCFDA dye (ThermoFisher Scientific, 10μM) for 30min at 37oC, and fluorescence was quantified by flow cytometry.

CD95 expression studies (adenovirus transduction)

Polycistronic adenoviral vectors were prepared to express the human and mouse CD95 sequences followed by the Encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) internal ribosome entry site and dTomato sequence under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter (VectorBuilder). Human and murine cancer cells or non-cancer cells were transduced to over-express full-length CD95, N-terminal CD95 (human: aa 1–209), C-terminal CD95 (human: aa 212–335), or express C-terminal CD95 that mimicked ELANE cleavage at both sites (aa 221–331, DDELANE). Cells were transduced with adenoviruses at an MOI of 50–250 depending on cell type, and expression of dTomato and CD95 (BD Biosciences) were confirmed by flow cytometry. A vector encoding GFP (VectorBuilder) was used as a control. To control for effects of viral transduction, results are plotted as a ratio of 48h (DDELANE is expressed) to 24h (DDELANE not yet expressed).

CRISPR CD95 knockdown studies

Cancer cells were transduced with Edit-r All-in-one lentiviral sgRNA (Dharmacon) at MOI 0.3. Knockdown cells were selected in puromycin (Sigma, 2.5μg/mL) containing media. Individual colonies were selected, screened for CD95 expression by immunoblotting, and colonies with lowest CD95 levels were selected for additional studies.

siRNA knockdown studies

Cancer cells were transfected with control siRNA (sc-37007) or NRP1 siRNA (sc-36038) using siRNA transfection reagents in siRNA transfection medium (sc-36868) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Transduction efficiency and subsequent experiments were performed 48h post transfection. Cancer cells were transfected with Silencer®control (4390843), H1.0 (S6394), or H1.2 siRNA (S194487) using Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent in Opti-MEM® I reduced serum medium according to the manufacturer’s protocol (ThermoFisher Scientific). Knockdown efficiency and subsequent experiments were performed 72h post transfection.

ELANE activity assays

Catalytic activity was measured using the chromogenic substrate N-Methoxysuccinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val p-nitroanilide (Sigma, 100μg/mL) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Absorbance was measured at 405nm using an accuSkan GO UV/Vis microplate spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). 1 unit is defined as the amount of enzyme hydrolyzes 1nmol of substrate/min at 37oC. For inactivation, ELANE or PPE was incubated with PMSF (1mM, Sigma) or A1AT (at indicated dose) for 2h. Residual PMSF was eliminated with a PD-10 desalting column (GE Healthcare Life). To monitor the effects of ECP on ELANE activity, ELANE (10nM) was incubated with various doses of ECP (0–180nM) at various substrate concentrations (0–1.7mM).

Recombinant mouse ELANE activation

Recombinant mouse ELANE (50μg/mL) was activated with CTSC (50μg/mL) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (R&D Systems).

Shotgun proteomics of neutrophil media

For trypsin digestion, 30μL of media (1μg protein) were denatured by heating at 65ºC and reduced with 5mM DTT for 1 h, alkylated with 15mM iodoacetamide for 30 min at room temperature in the dark, and excess iodoacetamide was quenched with an additional 5mM DTT. Samples were digested with trypsin (Promega) at 1:20 w/w ratio overnight at 37°C with mixing. After digestion, SDC was precipitated by addition of 1% trifluoroacetic acid and insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 14,000xg for 10min. Samples were then desalted by solid phase extraction using Oasis HLB 96-well μElution Plate, dried down, stored at −80°C, and reconstituted with 0.1% formic acid in 5% acetonitrile to a peptide concentration of 0.1μg/μL for LC-MS analysis.

Identification of ELANE cleavage sites in CD95 by mass spectrometry

Recombinant human C-terminal CD95 (aa 157–335, MyBioSource, 2μg) or recombinant N-terminal CD95 (aa 1–173, ThermoFisher Scientific, 1μg) were digested with human ELANE (0.01μg) for 2h at 37oC, and reactions were stopped with SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Proteins were separated on 20% SDS-PAGE gels, stained with Coomassie Blue (ThermoFisher Scientific), and bands were excised for mass spectrometric analyses. Proteins were extracted from excised bands and in-gel digests were performed as follows: excised bands were washed with 100mM ammonium bicarbonate and 50% acetonitrile in 100mM ammonium bicarbonate and digested in-gel with trypsin overnight. Digested peptides were extracted with 50% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid, and extracts were dried down and reconstituted in 20μL 1% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Analysis of recombinant peptides by mass spectrometry

Recombinant peptides (10μM) corresponding to aa 214-(TLNPETVAINLSDVDLSK)-231 or 317-(DITSDSENSNFRNEIQSLV)-335 of human CD95 (ThermoFisher Scientific) were incubated with ELANE (0.1–0.2μM) at 37oC for 15–30min. Reactions were stopped with 0.1% formic acid, and samples were analyzed by LC-MS/MS.

FLAG-DDELANE co-immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry

Cancer cells or non-cancer cells were transduced with FLAG-tag DDELANE adenovirus at MOI of 200 for 36h. Cell lysates were collected in RIPA buffer (150mM NaCl, 5mM EDTA, 50mM Tris, 1% NP-40, 0.5% SDC, 0.1% SDS) with freshly added Pierce protease inhibitor mini tablets and phosphatase inhibitors. Samples were immunoprecipitated using Pierce™ Anti-DYKDDDDK magnetic agarose (ThermoFisher Scientific), eluted in 0.1M glycine pH2.8, and subjected to mass spectrometry analysis using methods described for media.

LC-MS analyses

All mass spectrometry experiments were performed at the Quantitative and Functional Proteomics Core, Diabetes Research Center, University of Washington. For all studies, digested peptides were injected onto a trap column (40×0.1mm, Reprosil C18, 5μm, Dr.Maisch, Germany), desalted for 5 min at a flow of 4μL/min, and separated on a pulled tip analytical column (300 × 0.075 mm, Reprosil C18, 1.9 μm, Dr.Maisch, Germany) with a 3 segment linear gradient of acetonitrile, 0.1%FA (B) in water, 0.1%FA (A) as follows: 0–2 min 1–5%B, 2–150 min 5–25%B, 150–180 min 25–35%B followed by column wash at 80% B and re-equilibration at a flow rate 0.4μL/min (Waters NanoACQUITY UPLC). Tandem MS/MS spectra were acquired on Orbitrap Fusion Lumos (ThermoFisher Scientific) operated in data-dependent mode on charge states 2–4 with 2s cycle time, dynamic exclusion of 30s, HCD fragmentation (NCE 30%) and MS/MS acquisition in the Orbitrap.

MS spectra were acquired at a resolution 120,000 and MS/MS spectra (precursor selection window 1.6Da) at a resolution of 15,000. Peptides and proteins were identified using the Comet search engine (Eng et al., 2015) with PeptideProphet and ProteinProphet validation. Search criteria included a 20ppm tolerance window for precursors and products, fixed Cys alkylation, and variable Met oxidation. For recombinant peptides, data were analyzed in Skyline (MacLean et al., 2010) extracting ion chromatograms for all theoretical precursors arising from cleavage of all peptide bonds with a mass accuracy 10ppm. The identity of the peptides that provided significant chromatographic peaks was confirmed from MS/MS spectra.

Proximity ligation assay (PLA) and analysis

PLA was performed using Duolink® Proximity Ligation Assay Orange Kit (Sigma) containing Anti-Rabbit PLUS and Anti-Mouse MINUS PLA probes according to the manufacturer’s protocol. MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 cells were plated in 8 well-chambered cover glass dishes (C8–1.5H-N, CellVis) and grown to ~90% confluency. Cells were treated with ELANE (50nM) for, 0, 2, or 4 hours. For mitochondrial staining, Mito Deep Red (250 nM, ThermoFisher Scientific) was added 15min before fixation. Treated cells were fixed in acetone for 3 min, followed by a 20 min permeabilization in PBST (1XPBS containing 0.2% TritonX-100). Cells were blocked, stained with anti-FAS/CD95 (13098–1-AP Proteintech) and anti-Histone H1.0 (ab11079 Abcam) antibodies, and treated with PLUS/MINUS PLA probes. This was followed by ligation and amplification steps performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were stained with DAPI for 20 min at RT prior to imaging.

Confocal images were acquired on a Leica TCS SP5 II STED laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems) equipped with a 40x / 0.8 NA and 63X /1.4-NA oil-immersion objective. All image analyses were performed using Fiji ImageJ. For PLA quantification, whole cell regions of interest (ROIs) were selected on a three-color merged image of DAPI, MitoRed, and PLA channels. To count the number of PLA puncta per cell, a threshold binary image of the PLA channel was created. Using the ROI Manager, all ROI’s were combined, and puncta outside the combined area were cleared using Edit-Clear Outside command. Following this, the total number of punctate structures were calculated using Analyze Particles mode with a size selection of 1–250 pixels. The total number of PLA puncta per cell was calculated by dividing the number of PLA puncta per field by the total number of whole cell ROI’s selected. To count the number of PLA puncta per cell overlapped with the MitoRed signal a threshold binary image of the MitoRed channel was first created. This threshold image was multiplied with the PLA channel using the Image Calculator mode on ImageJ. The number of PLA puncta were then analyzed, similar to the method described above for the whole cell analysis.

Tumor inoculation and treatment

Mice in all experimental groups were sex and age matched.

Breast cancer models:

MDA-MB-231 cells (2×106 with Matrix Type 3) were injected into athymic nude mice; M1 or 4195 cells (50,000) were injected into NOD.SCID mice; and E0771 cells (0.5×106) were injected into C57BL/6 or Slpi−/− mice. All cells were injected into the 4th mammary fat pad of the right ventral side.

Flank models:

A549 cells (2×106 with Matrix Type 3), or MEL888 cells (2×106 with Matrix Type 3) were injected into athymic nude mice, LLC1 cells (0.5×106) or B16F10 cells (1×106) were injected into C57BL/6 or Slpi−/− mice. All cells were injected subcutaneously into the flank.

Intravenous models:

B16F10 cells (0.2×106) were injected into the lateral tail vein of C57BL/6 or Slpi−/− mice to create lung colonization. Lungs were excised and the number of tumors were quantified 14 days post injection.

Tumor treatments:

Once tumors reached ~50–100mm3, PMN or BMDN media or HSA (50μg/100μL), or ELANE or PMSF-ELANE (12μg/100μL; 10units) were intratumorally injected once/day for 5 days; PPE or PMSF-PPE (10 units) once/day for 2 days. Tumor volume was assessed by calipers, and experiments were terminated when tumor volume in control mice reached > 1000mm3.

Abscopal syngeneic models:

For the E0771 model, 0.5×106 cells were injected into the 4th mammary fat pad of the right ventral side (1o tumor), and 0.4×106 cells were injected into the 4th mammary fat pad of the left ventral side (2o tumor) of C57BL/6 mice. For the B16F10 model, 0.5×106 cells were injected into the flank (1o tumor). 7 days later, 0.2×106 cells were injected into the lateral tail vein to create 2o lung metastases.

For the ‘specificity control’, 0.5×106 E0771 cells were injected into the 4th mammary fat pad of the right ventral side (1o tumor) and 7 days later, 1×106 B16F10 cells were injected into the flank (2o tumor). ELANE or PMSF-ELANE was injected intratumorally into 1o tumors and tumor volume at both sites was measured by calipers.

For the ‘spillover control’, 0.5×106 E0771 cells were injected into the 4th mammary fat pad of the left ventral side (2o tumor). ELANE or PMSF-ELANE was injected into the tumor-free 4th mammary fat pad of the right ventral side (i.e., opposite the tumor) and tumor volume was measured by calipers.

C3T(1)-TAg GEM model:

Once the first palpable tumor in C3(1)-TAg mice reached ~50–100mm3 (17–18 weeks of age), ELANE or PMSF-ELANE (12μg, 10 units) were delivered intratumorally once/day for 5 days, or PPE or PMSF-PPE (10 units) once/day for 2 days. Tumor volume was assessed by calipers in live mice. Experiments were terminated when mice reached ~24 weeks of age and the weight of the injected tumor, and the total weight and number of non-injected tumors were measured.

Neutrophil depletion

Anti-mouse Ly6G (clone 1A8, Bio X Cells) or rat IgG2b (isotype control, Bio X Cells) were injected IP (12.5μg/injection, daily), 3 days prior to B16 cell injection (IV) and every day after injection. Neutrophil depletion was confirmed by flow cytometry.

CD8+ T cell depletion

Anti-mouse CD8α (clone 2.43, Bio X Cells) or rat IgG2b (isotype control, Bio X Cells) were injected IP (200μg/injection) 3 days before the first ELANE treatment, and once/week after the last ELANE treatment. C3(1)-TAg mice were treated with an anti-CD8 antibody 1 week prior to ELANE treatment and once/week following ELANE treatment until mice reached 23–24 weeks of age. CD8+ T cell depletion was confirmed by flow cytometry.

Bone marrow transplantation

Bone marrow cells (5×106) collected by PBS perfusion of the femurs and tibia of 8-week-old Slpi+/+ or Slpi−/− male mice were injected into the retro-orbital sinus of lethally irradiated (9.5 Gy ionizing radiation) 7-week-old male C57BL/6 wild type (Wt) recipient mice. Mice were maintained on a Uniprim diet for 1 week before and 2 weeks after transplant and allowed to recover for 6 weeks before tail vein injection of B16F10 cells (0.2×106). Engraftment was quantified by PCR as the ratio of Slpi−/− to Wt signal using pre-defined mixtures of Slpi−/− and Wt bone marrow cells as standards.

Tumor immunohistochemistry

Tumors were isolated on day 5 (1 day after ELANE/PMN media treatment, 4 days after PPE treatment). Tumors were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 24h, embedded in paraffin blocks, and sectioned (5μm). Slides were stained with cCASP3 (9661) and cPARP (9625) antibodies from Cell Signaling Technology. Signals were developed using the VECTASTAIN ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) or fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies (melanoma models). For the TUNEL assay, staining was performed with the DeadEnd™ colorimetric or fluorometric TUNEL systems (Promega). Cell nuclei were labeled with hematoxylin or Hoechst 33342 (ThermoFisher Scientific). Images were obtained with a Nikon Eclipse Ti2 microscope and analyzed using NIS-Elements software.

Tumor immune cell analyses

Tumors were isolated on day 5 (1 day after ELANE/PMN media treatment). Tumors were digested with Type 4 Collagenase (Worthington, 3mg/mL) and hyaluronidases (Sigma, 1.5mg/mL) at 37oC with shaking at 200rpm for 45min (E0771, C3(1)-TAg) or 30min (LLC1 and B16F10). Cells were labeled with various antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Assessment of toxicity