Abstract

Neural activity in awake organisms shows widespread and spatiotemporally diverse correlations with behavioral and physiological measurements. We propose that this covariation reflects in part the dynamics of a unified, arousal-related process that regulates brain-wide physiology on the timescale of seconds. Taken together with theoretical foundations in dynamical systems, this interpretation leads us to a surprising prediction: that a single, scalar measurement of arousal (e.g., pupil diameter) should suffice to reconstruct the continuous evolution of multimodal, spatiotemporal measurements of large-scale brain physiology. To test this hypothesis, we perform multimodal, cortex-wide optical imaging and behavioral monitoring in awake mice. We demonstrate that spatiotemporal measurements of neuronal calcium, metabolism, and blood-oxygen can be accurately and parsimoniously modeled from a low-dimensional state-space reconstructed from the time history of pupil diameter. Extending this framework to behavioral and electrophysiological measurements from the Allen Brain Observatory, we demonstrate the ability to integrate diverse experimental data into a unified generative model via mappings from an intrinsic arousal manifold. Our results support the hypothesis that spontaneous, spatially structured fluctuations in brain-wide physiology—widely interpreted to reflect regionally-specific neural communication—are in large part reflections of an arousal-related process. This enriched view of arousal dynamics has broad implications for interpreting observations of brain, body, and behavior as measured across modalities, contexts, and scales.

Introduction

The past decade has seen a proliferation of research into the organizing principles, physiology, and function of ongoing brain activity and brain “states” as observed in many species across widely varying recording modalities and spatiotemporal scales [1–4]. Ultimately, it is of interest to understand how such wide-ranging phenomena are coordinated within a functioning brain. However, as different domains of neuroscience have evolved around unique subsets of observables, the integration of this research into a unified framework remains an outstanding challenge [5, 6].

The interpretation of ongoing neural activity is further complicated by a growing awareness that such activity exhibits widespread, spatiotemporally heterogeneous relationships with behavioral and physiological variables [7–11]. For example, in awake mice, individual cells and brain regions show reliable temporal offsets and multiphasic patterns in relation to spontaneous whisker movements or running bouts [7, 8, 12]. Such findings have motivated significant attention to the decomposition and interpretation of neural variance that appears intermingled with the effects of ongoing state changes and movements [13–15]. However, the field has primarily focused on characterizing covariance rather than identifying underlying processes.

In this work, we posit a parsimonious explanation that unifies these diverse physiological and behavioral phenomena: that an intrinsic, arousal-related process evolving on an underlying, latent manifold continuously regulates brain and organismal physiology in concert with behavior on the timescale of seconds. This unified perspective is motivated by the fact that nominally arousal-related fluctuations are observed across—and thus, have the potential to bridge—effectively all domains of (neuro-)physiology and behavior [16–22]. Most recently, ongoing arousal fluctuations—variably indexed according to pupil diameter, locomotion, cardiorespiratory physiology, or electroencephalography (EEG) [23]—have emerged as a principal factor of global neural variance [7, 24]. We further strengthen and extend this connection by showing that the dynamics of an underlying process, which we refer to as arousal dynamics, accounts for even more of the spatiotemporal heterogeneity discussed above than is conventionally attributed to arousal (e.g. via linear regression).

At the core of our approach is a hypothesized connection between two largely independent lines of research on brain states. The first of these has established regional dependence of cortical activity upon ongoing fluctuations in arousal and behavioral state [8, 9, 11]; however, general principles have remained elusive [1, 5]. A second line of work has established general principles of spontaneous spatiotemporal patterns in large-scale brain activity [25–27], which are characterized by a topographically organized covariance structure. This structure is widely thought to emerge from specific inter-regional interactions [28–30]; as such, arousal is not thought to be fundamental to the physiology or phenomenology of interest. Instead, in this paradigm, arousal emerges as a slow or intermittent modulator of interregional covariance structure [22, 31–34], or as a distinct global component [35–38]. In contrast, we propose that the above lines of research capture the same underlying physiology—specifically, that an organism-wide regulatory process constitutes the primary mechanism underlying spatially structured patterns of spontaneous activity observed on the timescale of seconds [39]. We refer to this latent process as “arousal”, though we provide a data-driven procedure to compute it from observables.

In this study, we test a central prediction of this unified perspective: specifically, that a scalar index of arousal suffices to accurately reconstruct multimodal measurements of large-scale spatiotemporal brain dynamics. We provide experimental support for this prediction across simultaneously recorded measurements of neuronal calcium, metabolism, and hemodynamics, demonstrating that the spatiotemporal evolution of these measurements is largely reducible by a common latent process that is continuously tracked by pupil diameter. Specifically, we show that a time delay embedding [40–42] of the scalar pupil diameter may be used to reconstruct a latent arousal manifold, from which time-invariant mappings predict a surprising amount of spatiotemporal variation in other modalities. Time delay embedding is a powerful technique in data-driven dynamical systems [43] with strong theoretical guarantees, that under certain conditions it is possible to reconstruct dynamics on a manifold from incomplete, and even scalar, measurements. This theory is further strengthened by the Koopman perspective of modern dynamical systems [44], which shows that time delay coordinates provide universal embeddings across a wide array of observables [45]. We exploit this property to show that generative models based on an intrinsic arousal manifold enable us to accurately reconstruct multimodal measurements of spatiotemporal brain dynamics. Taken together, our findings reveal a deep connection between the mechanisms supporting spatiotemporal organization in brain-wide physiology and organism-wide regulation.

Results

We performed simultaneous multimodal widefield optical imaging [46] and face videography in awake, head-fixed mice. Fluorescence across the dorsal cortex was measured in 10-minute sessions from a total of N = 7 transgenic mice expressing the red-shifted calcium indicator jRGECO1a in excitatory neurons.

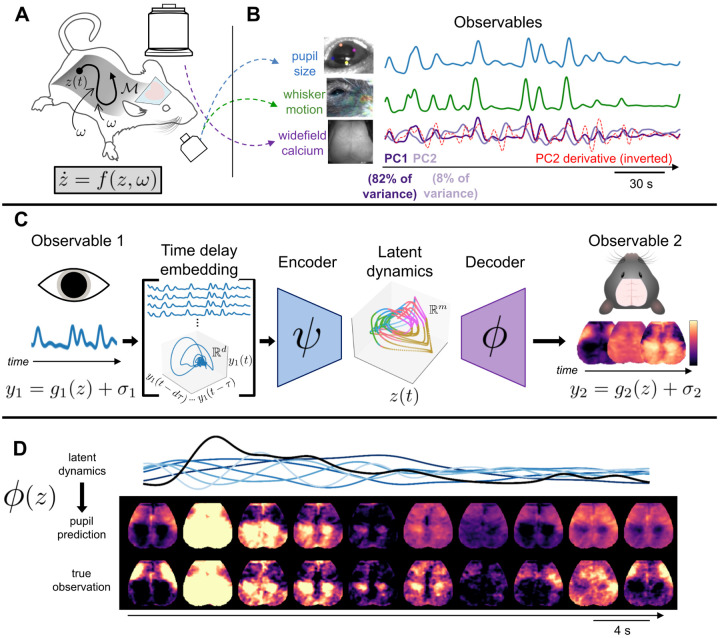

We observed prominent, spontaneous fluctuations in pupil diameter and whisker motion throughout each recording session (Fig. 1B). Consistent with prior work [7, 47], linear decomposition using traditional principal component analysis (PCA) of the neuronal calcium time series revealed a leading component (PC1) that closely tracked these fluctuations (Fig. 1B). Notably, we found that this leading component dominated the calcium time series, accounting for between 70 – 90% of the variance in all seven mice (Fig. S1).

Figure 1: Study overview.

A We performed simultaneous widefield optical imaging and face videography in awake mice. We interpret these measurements as observations of dynamics on an organism-intrinsic arousal manifold ℳ (i.e., a low-dimensional surface within the state space). Trajectories of the state z along ℳ result from intrinsic arousal dynamics and various stochastic (i.e., arousal-independent) perturbations ω(t) (arising from within and outside the organism), such that B Three observable quantities derived from these recordings: scalar indices of pupil diameter and of whisker motion, and high-dimensional images of widefield calcium fluorescence. Here, widefield images are represented as the time series of the first two principal components (PCs). The first brain PC (PC1) closely tracked pupil diameter and whisker motion and accounted for 70–90% of the variance in each mouse (Fig. S1). However, remaining PCs often retained a clear temporal relationship with arousal. Specifically, here PC1 closely resembles PC2’s derivative (red dashed line, Pearson r = −.73), implying that (nonlinear) correlation with arousal dynamics extends even beyond the dominant “arousal component” [7, 47]. C Our study describes an approach to parsimoniously model “arousal dynamics” and its manifestations. Each observable yi is interpreted as the sum of an observation function on z and observation-specific variability σi (i.e., yi = gi(z) + σi). We test the specific hypothesis that pupil size and large-scale brain activity are both regulated by a common arousal-related process. Takens’ embedding theorem [40] implies the possibility of relating these observables via a composition of encoder and decoder functions (i.e., ψ and ϕ) that map to and from a low-dimensional latent space representing the full state dynamics (z(t)). The encoder maps to this low-dimensional latent space from a d–dimensional “time delay embedding” comprising d time-lagged copies of y1 (i.e., pupil diameter). D An example epoch contrasting original and pupil-reconstructed widefield images (held-out test data from one mouse). Black is pupil diameter; blue traces are delay coordinates, where increasing lightness indicates increasing order (Methods).

Importantly, inspection of additional PCs suggested a still richer interpretation: despite being orthogonal, higher PCs typically retained a clear temporal relationship to PC1, e.g., closely approximating successive derivatives in time (Fig. 1B). Thus, although variance associated with arousal is widely presumed to be restricted to one dimension, these dynamical relationships instead suggest that scalar indices of arousal, such as pupil size or a single PC, may be best interpreted as one-dimensional projections of an underlying process whose manifestations extend to multiple dimensions (Fig. 1A). We refer to this underlying process as “arousal dynamics”, and hypothesize that the spatiotemporal evolution of large-scale brain activity is primarily a reflection of this process. Below, we motivate this idea from a physiological perspective before introducing its dynamical systems framing. Ultimately, this framing enables us to empirically evaluate predictions motivated by this perspective.

Studying arousal dynamics

We interpret nominally arousal-related observables (e.g., pupil size, whisking) to primarily reflect the dynamics of a unified, organism-wide regulatory process (Fig. 1A). This dynamic regulation [48] may be viewed as a low-dimensional process whose evolution is tied to stereotyped variations in the high-dimensional state of the organism. Physiologically, this abstraction captures the familiar ability of arousal shifts to elicit multifaceted, coordinated changes throughout the organism (e.g., “fight-or-flight” vs. “rest-and-digest” modes) [49]. Operationally, this framing motivates a separation between the effective dynamics of the system, which can be represented on a low-dimensional manifold [50–52], and the high-dimensional “observation” space, which we express via time-invariant mappings from the latent manifold. In this way, rather than assuming high-dimensional and direct causal interactions among the measured variables (and neglecting causal relevance of the far greater number of unmeasured variables) [53–55], we attempt to parsimoniously attribute widespread variance to a common latent process.

To specify the instantaneous latent arousal state, our framework takes inspiration from Takens’ embedding theorem [40], which provides general conditions under which the embedding of a scalar time series in time delay coordinates preserves topological properties of (i.e., is diffeomorphic to) the full-state attractor. Delay embedding has become an increasingly powerful technique in modern data-driven dynamical systems [43]. Specifically, time delay coordinates have been shown to provide universal coordinates that represent complex dynamics for a wide array of observables [45], related to Koopman operator theory in dynamical systems [44, 56]. As we hypothesize that brain-wide physiology is spatiotemporally regulated in accordance with these arousal dynamics [39], Takens’ theorem leads us to a surprising empirical prediction: a scalar observable of arousal dynamics (e.g., pupil diameter) can suffice to reconstruct the states of a high-dimensional observable of brain physiology (e.g., optical images of cortex-wide activity), to the degree that the latter is in fact coupled to the same underlying dynamical process [42, 57, 58].

To test this hypothesis, we developed a framework for relating observables that evolve in time according to a shared dynamical system. Fig. 1C illustrates our data-driven approach to compute these relationships. In each mouse, we embed pupil diameter measurements in a high-dimensional space defined by its past values (i.e., time delay coordinates). We wish to discover a map (or encoder) ψ from this newly constructed observation space to a low-dimensional latent space z, which represents the instantaneous arousal state as a point within a continuous, observation-independent state space. We additionally seek a mapping (decoder) ϕ from this latent space to the observation space of widefield calcium images. These mappings can be approximated with data-driven models learned using linear or nonlinear methods. Ultimately, this procedure enables us to express each instantaneous widefield calcium image as a function of the present and preceding values of pupil size (i.e., pupil delay coordinates), to the extent that these two observables are deterministically linked to the same latent arousal state z.

Spatiotemporal dynamics from a scalar

For all analyses, we focused on (“infra-slow”) fluctuations < 0.2 Hz, as this frequency range distinguishes arousal-related dynamics from physiologically distinct processes manifesting at higher frequencies (e.g., delta waves) [59, 60]. We trained models on the first 5 minutes of data for each mouse and report model performance on the final 3.5 minutes of the 10-minute session. These models included a linear regression model based upon a single lag-optimized copy of pupil diameter (“No embedding”), as well as a model that used multiple delay coordinates and nonlinear mappings (“Latent model”). The latter model thus provided flexibility in capturing a greater diversity of shared variance that we hypothesized to evolve according to the same dynamics. Nonlinear mappings were learned through simple feedforward neural networks, which were trained within an architecture modeled after the variational autoencoder [61] (with hyperparameters fixed across mice; Methods). See Supplementary Appendix (Supplementary Text and Figs. S2–S3) for validation of this framework on a toy (stochastic Lorenz) system.

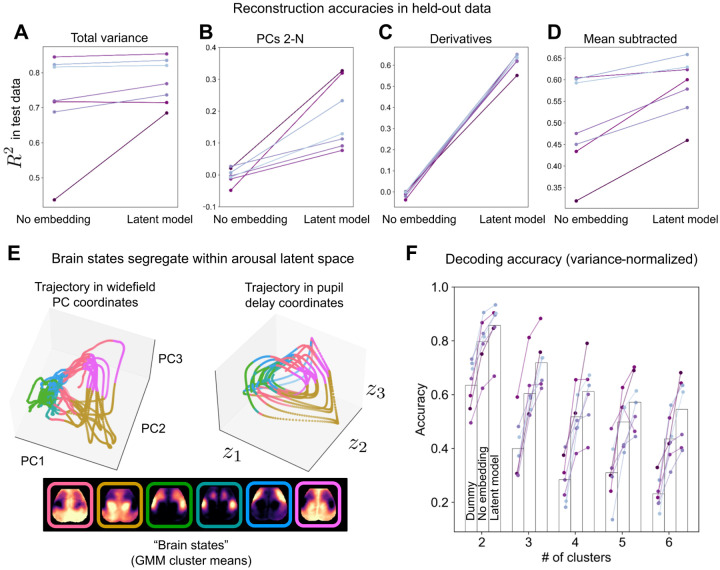

Modeling results are shown in Fig. 2A–D. In each of N = 7 mice, we succeeded in accurately reconstructing held-out widefield calcium images on the basis of (simultaneously measured) pupil diameter, accounting for 60–80% of the variance < 0.2 Hz (Fig. 2A). We achieved this level of accuracy in almost all mice via linear regression with a one-dimensional pupil regressor, owing to the predominance of the first PC and its tight, linear relationship with pupil size. Including multiple delays and nonlinearities further improved modeled variance, primarily by capturing variance spread along the remaining dimensions (Figs. 2B and S4–S5). Note that improved explanatory power in held-out data is not a trivial result of model complexity, as we confirmed by shuffling pupil and widefield measurements across mice (Fig. S6). Rather, these results are consistent with the notion that arousal dynamics are synchronized with the smooth spatiotemporal dynamics observed in widefield data, which cannot be captured in a single dimension. Consequently, an appreciable amount of widefield variance lying outside the dominant PC was predictable from a time-invariant mapping from pupil dynamics (Fig. 2B–C).

Figure 2: Pupil diameter enables reconstruction of spatiotemporal brain dynamics.

A Variance explained in widefield data test set (the last 3.5 minutes of imaging per mouse not used for model training). A simple linear regression model based on one (lag-optimized) pupil regressor (“No embedding”) accurately predicted 70–90% of variance in six of seven mice. Delay embedding and nonlinearities (“Latent model”) extended this level of performance to all mice, while further augmenting model performance, primarily by accounting for variance spread along higher dimensions (PCs 2-N) (B). C The latent model additionally accounted for the majority of variance in the temporal derivatives of widefield images in all seven mice, indicating that the dynamics of widefield images largely reflect the dynamics of arousal. The scalar, lag-optimized pupil regressor (i.e., “No embedding”) did not track the temporal dynamics of widefield images. D Although subtraction of the mean timecourse removed spatially uninformative variance, the latent model continued to explain a large fraction of the remaining, spatially-informative variance. E Example state trajectories (held-out data) visualized in coordinates defined by the first three widefield PCs (left) or three latent variables obtained from the delay-embedded pupil time series. Trajectories are color-coded by cluster identity as determined by a Gaussian mixture model (GMM) applied to widefield image frames (k = 6 clusters). Cluster means are shown below these trajectory plots. Color segregation in pupil delay coordinates indicates spatially-specific information encoded in pupil dynamics. F Decoding “brain states” from pupil dynamics. Comparison of classifier accuracy in properly identifying (high-confidence) GMM cluster assignments for each image frame based on the most frequent assignment in the training set (“Dummy” classifier), the “No embedding” model, or the “Latent model”. Classifier performance is shown as a function of allowable clusters (e.g., allowing for four possible clusters, pupil dynamics enabled > 60% classification accuracy.

Next, we examined to the extent to which arousal dynamics indexed the spatial topography of widefield images. We began by examining variance explained in mean-subtracted widefield data. The global mean timecourse captures (by definition) widefield variance devoid of spatial information. Accordingly, subtracting this timecourse would account for the common interpretation of arousal as a global upor down-regulation of neural activity, leaving behind only spatially-specific variation. Following this procedure, we found that pupil diameter continued to account for a large fraction of variance in mean-subtracted widefield images. In particular, inclusion of pupil dynamics enabled us to account for the majority of this remaining variance in 6/7 mice (Fig. 2D). Thus, arousal dynamics reliably account for the majority of spatially informative variance in cortex-wide calcium measurements.

To assess whether this correspondence was restricted to high-amplitude, temporally isolated events, we repeated the analysis after eliminating time-varying changes in both the mean and amplitude of widefield measurements. Thus, following subtraction of the global mean timecourse, we scaled each image frame to the same level of variance, then assigned these normalized images to clusters using a Gaussian mixture model (Methods). In this way, image frames were assigned to clusters purely based upon the similarity of their spatial patterns. Following this procedure, we asked whether pupil dynamics enabled us to infer the cluster assignment of widefield data on a frame-to-frame basis.

Fig. 2E–F illustrates the results of these clustering and decoding analyses. Fig. 2E demonstrates the segregation of distinct spatial topographies to different regions of the arousal latent space (derived from pupil diameter), indicating that arousal dynamics are informative of spatially-specific patterns of cortex-wide activity. Fig. 2F shows decoding accuracy in the test data as a function of the number of allowable clusters. This decoding accuracy is reported for three classifiers: a nonlinear classifier based on the “No embedding” model; a (linear) classifier based on the “Latent model”; and a “Dummy” classifier that labeled all frames in the test data according to the most frequent assignment in the training data (i.e., the prior) (Methods).

In general, we observed that spatial patterns largely alternated between two primary patterns, consistent with large-scale spatiotemporal measurements reported across modalities and species [39, 62–64]. With a two-cluster solution, pupil dynamics enabled accurate assignment of on average > 80% of high-confidence image frames (Fig. 2F). Classification accuracy remained high with three distinct topographies, with the latent model enabling an average accuracy of > 70%. With more than three clusters, we found spatial topographies to be increasingly less distinctive, leading to gradually worsening classification accuracy. Yet, decoding accuracy continued to follow a common trend, steadily improving from the “Dummy” classifier to the “No embedding” classifier, and, finally, to the “Latent model” classifier. These results confirm that arousal dynamics reliably index the instantaneous spatial topography of large-scale calcium fluorescence.

Taken together, our analyses support the interpretation that arousal, as indexed by pupil diameter, is the predominant physiological process underlying cortex-wide spatiotemporal dynamics on the timescale of seconds.

Multimodal spatiotemporal dynamics from a shared latent space

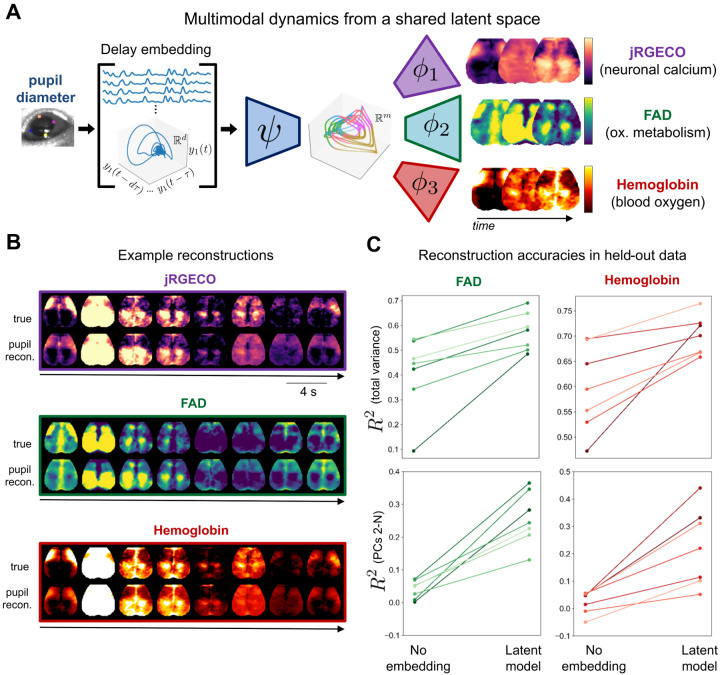

We have hypothesized that arousal dynamics support the spatiotemporal regulation of brain-wide physiology—thus extending beyond the activity of neurons per se (e.g., [20, 47, 65]). Spatially structured fluctuations in metabolic and hemodynamic measurements are also well-established, and are generally interpreted to reflect state-, region-, and context-dependent responses to local neuronal signaling [66]. On the other hand, our account posits that multiple aspects of physiology are jointly regulated according to a common process. This suggests the possibility of more parsimoniously relating multiple spatiotemporal readouts of brain physiology through a common low-dimensional latent space reconstructed from pupil diameter.

We found that it is indeed possible to link the dynamics of multiple readouts of brain physiology through a shared latent space (Fig. 3). To do this, we took advantage of a novel multispectral optical imaging platform [46] that simultaneously maps neuronal activity (jRGECO1a fluorescence), oxidative metabolism (as indexed by FAD autofluorescence [67, 68]), and hemodynamics (which approximates the physiological basis for fMRI in humans). We attempted to reconstruct all three biological variables on the basis of delay embedded pupil measurements. Importantly, we did not retrain the encoder ψ after training to predict calcium measurements; instead, we learned separate decoders ϕi that map to spatiotemporal measurements of FAD and oxygenated hemoglobin.

Figure 3: Multimodal physiological measurements can be reconstructed from a shared latent manifold.

A. The delay embedding framework extended to model multimodal observables. We used the same encoder previously trained to predict calcium images. We coupled this encoder to decoders trained separately for FAD and hemoglobin. B. Example reconstructions of neuronal calcium (jRGECO fluorescence), metabolism (FAD), and blood oxygen (concentration of oxygenated hemoglobin). C. Reconstruction performance for each observable (as in Fig. 2A). See Fig. 2 for results with calcium.

Modeling accuracy for FAD and hemoglobin measurements are shown in Fig. 3B. As with calcium fluorescence, we were able to accurately model the large-scale spatiotemporal dynamics of these two measurements in each of N = 7 mice. Interestingly, for these measurements, delay embeddings and nonlinearities made a much larger contribution to the explained variance (Fig. 3C). Thus, a far larger portion of metabolic and hemodynamic fluctuations can be attributed to a common, arousal-related mechanism than has been previously recognized (see also [39, 69]).

Unifying observables through arousal dynamics

So far, our analyses support the interpretation of arousal as a state variable with physiologically relevant dynamics. This generalized, dynamical interpretation of arousal enables us to parsimoniously account for ongoing fluctuations in “brain state” as observed across multimodal measurements of large-scale spatiotemporal activity. A central motivation for this perspective is the extraordinary breadth of observables that have been related to common arousal measurements [6]. How does the proposed account relate to other common indices of arousal?

A key aspect of our framework is that it distinguishes measurements (“observables”) from the lower-dimensional, latent generative factors of arousal dynamics. Thus, our framework can readily accommodate data from additional recording modalities—while maintaining a parsimonious, phenomenological representation of arousal dynamics—simply by approximating additional observation functions (as in Fig. 3). Importantly, as these observation functions are defined as mappings from an organism-intrinsic manifold, rather than an imposed stimulus or task (cf. [70]), this raises the possibility of further generalizing our framework to observables recorded across experimental datasets. That is, we may construct a unified generative model for a wide range of observables based upon their learned relations to a common arousal manifold. In this way, our framework enables us to formally integrate the present findings into a more holistic context than is typically possible in any single experimental study.

To demonstrate this generalizability, we extended our framework to publicly available behavioral and electrophysiological recordings from the Allen Institute Brain Observatory [71]. This dataset includes 30-minute recording sessions of mice in a task-free context, i.e., without explicit experimental intervention. From this dataset, we computed eight commonly used indices of brain state and arousal (see Methods): pupil diameter, running speed, hippocampal θ/δ ratio, the instantaneous rate of hippocampal sharp-wave ripples (SWRs), bandlimited power (BLP) derived from the local field potential (LFP) across visual cortical regions, and mean firing rate across several hundred neurons per mouse recorded with Neuropixels probes [72]. The two hippocampal indices were both defined from the CA1 LFP. BLP across visual cortex was further analyzed within three canonical frequency ranges: 0.5–4 Hz (“delta”), 3–6 Hz (“alpha” [73]), and 40–100 Hz (“gamma”).

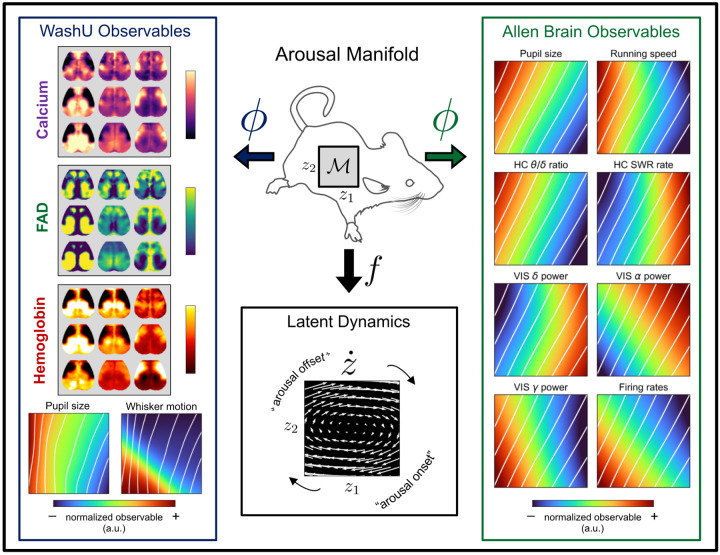

We trained neural networks to predict each observable from a latent space constructed from (delay embedded) pupil measurements. Fig. 4 shows a visualization of these results based on a two-dimensional, group-level embedding computed from time series concatenated across mice. We note that, in practice, individual-specific observations can be aligned to a universal, analytically defined orthogonal basis [74, 75] (rather than the two-dimensional, nonlinear coordinates used here for efficient visualization); see Supplementary Text for details. After training on concatenated measurements, for each mouse, we applied the learned encoding to that mouse’s delay embedded pupil measurements, then trained a decoder to map from this latent space to that mouse’s observables. Finally, we repeated this procedure for the primary widefield dataset—thus using pupil diameter as a common reference to align observables across datasets (and mice) to a shared manifold (see Methods for further details).

Figure 4: Unifying observables through arousal dynamics.

Our framework distinguishes recorded observables from their lower-dimensional, latent generative factors. This enables a systems-level characterization of arousal that readily accommodates new measurement data. For visualization purposes, pupil delay coordinates were reduced to two latent factors z1 and z2, providing a 2D parameterization of the manifold. From a sample grid of points, we used the discovered observation functions (i.e., decoders ϕ) to evaluate the expected value of each observable at each point on the manifold. This procedure was repeated for the observations recorded from animals at Washington University (WashU) and those recorded through the Allen Brain Observatory. In each case, the results shown were averaged over mice for presentation (see Fig. S7 for quantification in individual mice). White diagonals are iso-contours of pupil diameter. Estimation of the vector field at each point (via a data-driven analytical approximation of the dynamics [76]) clarifies the average direction of flow along the manifold (“Latent Dynamics”). This vector field characterizes cyclical (clockwise) flow of the latent arousal dynamics (governed by f), while the “observable” plots can be used to infer how this evolution would manifest in the space of each physical observable (given by ϕ).

Fig. 4 illustrates the resulting, multi-dataset generative model that unifies numerous measurements of brain state and arousal. As the latent space was regularized to be continuous (roughly, an isotropic Gaussian [61]), we characterized the arousal manifold ℳ by simply evaluating the data-driven mapping (ϕ) for each observable at each point within a 2D grid in the latent space. In addition, by obtaining a data-driven analytic representation of the latent dynamics [76] (Methods), we evaluated the vector field at each point on the 2D grid, thus summarizing the average flow of arousal dynamics. Taken together, for each point along ℳ, the representation in Fig. 4 depicts 1) the expected direction of flow of the latent arousal dynamics (governed by f), and 2) the expected value in the space of each observable (determined by ϕ).

This representation unifies and clarifies relations among several themes appearing in different sectors of the experimental literature, which we briefly summarize here. As expected, running speed, hippocampal θ/δ ratio, cortical gamma BLP, and mean firing rate are all positively correlated with pupil diameter along a single, principal dimension, z1 (i.e., the horizontal coordinate) (Fig. 4, “Allen Brain Observables”). Delta and “alpha” BLP, as well as hippocampal SWR rate, are inversely correlated with pupil diameter along the same z1 dimension [12, 77, 78].

A second dimension (z2, vertical) clarifies more subtle temporal relationships, parsimoniously capturing diverse phenomenology previously reported in the context of brain and behavioral state transitions [79–82]. Thus, the “arousal onset” (Fig. 4) begins with decreasing alpha BLP [80] and subsequent increases in firing rates and gamma BLP, which precede an increase in pupil diameter [47, 79]. The “WashU observables” indicate that this arousal onset period is also characterized by the onset of whisking and a propagation toward posterior cortical activity [59, 64, 83].

Following this “arousal onset” period, the Allen Brain Observables indicate roughly synchronous increases in pupil diameter, locomotion, and hippocampal θ/δ ratio. After these observables reach their maximum, alpha BLP begins to increase, consistent with the appearance of this cortical oscillation at the offset of locomotion [73] (marked as “arousal offset” in Fig. 4). This is succeeded by a general increase in delta BLP and hippocampal SWR rate. Across the cortex, this behavioral and electrophysiological sequence at “arousal offset” (as indicated by the Allen Brain Observables) is associated with a propagation of activity from posterior to anterior cortical regions (as indicated by the WashU observables). Finally, activity propagates toward lateral orofacial cortices, which remain preferentially active until the next arousal onset. This embedding of cortex-wide topographic maps within a canonical “arousal cycle” resembles prior results obtained from multimodal measurements in humans and monkeys, which additionally link these cortical dynamics to topographically parallel rotating waves in subcortical structures [39]. Taken together, this framework enables a coherent and parsimonious representation of heterogeneous phenomena reported across a wide range of experimental techniques.

Discussion

We have proposed that an arousal-related dynamical process spatiotemporally regulates brain-wide physiology in accordance with global physiology and behavior. We have provided support for this account through a data-driven modeling framework, which we used to demonstrate that a scalar index of arousal, pupil diameter, suffices to accurately predict multimodal measurements of cortex-wide spatiotemporal dynamics. We interpret the success of this procedure as support for the hypothesis that the widely studied phenomenon of slow, spontaneous spatiotemporal patterns in large-scale brain activity are primarily reflective of an intrinsic regulatory mechanism [39]. Taken together, these results carry implications for the phenomenological and physiological interpretation of arousal, large-scale brain dynamics, and the interrelations among multimodal readouts of brain physiology. These implications are considered in what follows.

The present findings support the existence of an arousal-related process whose dynamics can account for multidimensional variance across diverse measurements. This finding indicates a much broader explanatory value for arousal than is presently recognized. Importantly, this generalized interpretation of arousal is corroborated by two emerging themes in the literature. First, brain or arousal states correspond to distinct (neuro)physiological regimes, involving sweeping changes to neuronal dynamics and brain-wide physiology and metabolism [20, 84, 85]. This limits the degree to which arousal-dependence can be accounted for by orthogonalizing observations with respect to a scalar arousal index (e.g., via linear regression of pupil diameter or removal of the leading PC; Fig. 2B). Second, numerous studies have established non-random transitions among brain states [1, 86, 87], as well as diverse functional (and often nonlinear) correlates of dynamical indices of arousal, such as the phase or derivative of pupil size [39, 47, 79, 81, 88]. Collectively, these findings support the interpretation of arousal as a state variable for an organism-intrinsic dynamical process—one whose manifestations cannot be easily separated from other biological or behavioral sources of variation.

Our findings additionally challenge existing interpretations of large-scale spatiotemporal brain dynamics. The study of these dynamics has gained considerable attention across multiple experimental communities over a span of decades. Across these communities, large-scale spatiotemporal structure has been over-whelmingly interpreted to reflect a summation of diverse interregional interactions [26, 28, 30, 89]. Our results support a more parsimonious alternative: that the primary generative mechanism of this structure, on seconds-to-minutes timescales, is an arousal-related regulation of brain-wide physiology [39]. This interpretation unifies two largely independent branches of brain state research, simultaneously addressing two major questions in systems neuroscience: specifically, whether there exist general principles describing the spatial organization of arousal dependence [8, 9, 11], and what is the physiological or mechanistic basis of slow, large-scale spatiotemporal patterns of spontaneous brain activity [25, 28]. Our results are in line with recent evidence that, despite the plethora of analyses used to study these spontaneous spatiotemporal patterns, they are largely reducible to low-dimensional global dynamics [90] organized into arousal-synchronized rotating waves [39].

Spatially structured patterns of spontaneous brain activity have been reported across modalities spanning electrophysiology, hemodynamics, and metabolism. These physiological measurements share a tight and evolutionarily ancient link [24], forming the foundation of non-invasive human neuroimaging techniques. Ongoing fluctuations in these variables are generally viewed to be interrelated through complex, region-dependent, and incompletely understood neurovascular and neurometabolic cascades operating locally throughout the brain [66]. On the other hand, there has long been evidence that global neuromodulatory processes act upon each of these neural, hemodynamic, and metabolic variables in parallel [91–93]. This oft-overlooked evidence lends support to our parsimonious viewpoint: that spontaneous fluctuations coordinated across multimodal spatiotemporal measurements reflect in large part a globally acting regulatory mechanism. Future experiments will be required to discern the degree to which global neuromodulatory processes play a more direct role in neurovascular and neurometabolic coupling than presently recognized. Nonetheless, the question of direct mechanism may be viewed as distinct from the question of how these variables relate to each other in a functional or phenomenological sense.

Finally, although we have adopted the term “arousal” given widespread adoption of this term for the observables discussed herein, our results are obtained through an entirely data-driven approach: “arousal” is simply the label we assign to the latent process inferred from the observables. In other words, we make no a priori assumptions about how arousal might be represented in these observables in comparison to other behavioral processes or states [94]. For this same reason, our results are likely relevant to a range of cognitive and behavioral processes that are traditionally distinguished from arousal (e.g., “attention”), but which may be intimately coupled (or largely redundant) with the dynamical process formalized herein [2, 95].

Methods

Datasets and preprocessing

Dataset 1: Widefield optical imaging (WashU)

Animal preparation

All procedures described below were approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee in compliance with the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care guidelines. Mice were raised in standard cages in a double-barrier mouse facility with a 12 h–12 h light/dark cycle and ad libitum access to food and water. Experiments used N=7 12-week old mice hemizygous for Thy1-jRGECO1a (JAX 030525). Prior to imaging, a cranial window was secured to the intact skull of each mouse with dental cement under isoflurane anesthesia according to previously published protocols [96].

Data acquisition

Widefield imaging was conducted on dual fluorophore optical imaging system; details of this system have been describe in detail elsewhere [46, 97]. Mice were head-fixed under the imaging system objective using an aluminum bracket attached to a skull-mounted Plexiglas window. Prior to data acquisition in the awake state, mice were acclimated to head-fixation over several days.

The mouse’s body was supported by a felt pouch suspended by optical posts (Thorlabs). Resting state imaging was performed for 10 minutes in each mouse. Before each imaging run, dark counts were imaged for each mouse for 1 second with all LEDs off in order to remove background sensor noise.

Preprocessing

Images were spatially normalized, downsampled (to a resolution of 128×128), co-registered, and affine-transformed to the Paxinos atlas, temporally detrended and spatially smoothed as described previously [98]. Changes in 530nm, and 625nm reflectance were interpreted using the modified Beer-Lambert law to calculate changes in hemoglobin concentration as described previously [46].

Image sequences of fluorescence emission detected by CMOS1 (i.e., uncorrected FAD autofluorescence) and CMOS2 (i.e., uncorrected jRGECO1a) were converted to percent change (dF/F) by dividing each pixel’s time trace by its average fluorescence over each imaging run. Absorption of excitation and emission light for each fluorophore due to hemoglobin was corrected as outlined in [99]. From the face videography we derived scalar indices of pupil size via DeepLabCut software [100] and whisker motion via the Lucas-Kanade optical flow method [101] applied to and subsequently averaged across five manually selected data points on the whiskers. Except where noted, the resulting pupil diameter, whisker motion, and widefield time series were bandpass filtered between 0.01 < f < 0.2 Hz in order to distinguish the hypothesized spatiotemporal process from distinct phenomena occurring at higher frequencies (e.g., slow waves) [59], and to accommodate finite scan duration 10 minutes.

Dataset 2: Allen Brain Observatory

We additionally analyzed recordings obtained from awake mice and publicly released via the Allen Brain Observatory Neuropixels Visual Coding project [71]. These recordings include eye-tracking, running speed (estimated from running wheel velocity), and high-dimensional electrophysiological recordings obtained with Neuropixels probes [72]. We restricted analyses to the “Functional Connectivity” stimulus set, which included a 30-minute “spontaneous” session with no overt experimental stimulation. Data were accessed via the Allen Software Development Kit (SDK) (https://allensdk.readthedocs.io/en/latest/). From 26 available recording sessions, we excluded two lacking eye-tracking data and four sessions with compromised eye-tracking quality.

Preprocessing

From the electrophysiological data we derived estimates of population firing rates and several quantities based upon the local field potential (LFP). We accessed spiking activity as already extracted by Kilosort2 [7]. Spikes were binned in 1.2 s bins as previously [7], and a mean firing rate was computed across all available units from neocortical regions surpassing the default quality control criteria. Neocortical LFPs were used to compute band-limited power within three canonical frequency bands: gamma (40 – 100 Hz), “alpha” (3 – 6 Hz) and delta (0.5 – 4 Hz). Thus, LFPs were first filtered into the frequency band of interest, temporally smoothed with a Gaussian filter, downsampled to 30 Hz (matching the eye-tracking sampling rate), bandpass filtered between 0.001 < f < 0.2 Hz, and averaged across all channels of probes falling within “VIS” regions (including primary and secondary visual cortical areas). A similar procedure was applied to LFP recordings from the hippocampal CA1 region to derive estimates of hippocampal theta (5–8 Hz) and delta (0.5–4 Hz) band-limited power. Hippocampal sharp-wave ripples were detected on the basis of the hippocampal CA1 LFP via an automated algorithm [102] following previously described procedures [103]. Finally, all time series were downsampled to a sampling rate of 20 Hz to facilitate integration with Dataset 1.

Data analysis

State-space framework

Formally, we consider the generic state-space model:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where the nonlinear function f determines the (nonautonomous) flow of the latent (i.e., unobserved), vector-valued arousal state z = [z1,z2,··· ,zm]T along a low-dimensional attractor manifold ℳ, while ω(t) reflects random (external or internal) perturbations decoupled from f that nonetheless influence the evolution of z (i.e., “dynamical noise”). We consider our observables {y1,y2,…,yn} as measurements of the arousal dynamics, each resulting from an observation equation gi, along with other contributions σn(t) that are decoupled from the dynamics of z (and in general are unique to each observable). Thus, in this framing, samples of the observable yi at consecutive time points t and t+1 are linked only through the evolution of the latent variable z as determined by f. Note that f is expected to include many causal influences spanning both brain and body (and the feedback between them), while measurements (of either brain or body) yi are decoupled from these dynamics. This framework provides a formal, data-driven approach to parsimoniously capture the diverse manifestations of arousal dynamics, represented by the proportion of variance in each observable yi that can be modeled purely as a time-invariant mapping from the state space of z.

State-space reconstruction: time delay embedding

Our principal task is to learn a mapping from arousal-related observables to the multidimensional space where the hypothesized arousal process evolves in time. To do this, we take advantage of Takens’ embedding theorem from dynamical systems theory, which has been widely used for the purpose of nonlinear state space reconstruction from an observable. Given p snapshots of the scalar observable y in time, we begin by constructing the following Hankel matrix H ∈ Rd×(p–d+1):

| (3) |

for p time points and d time delays. Each column in this matrix corresponds to a short trajectory of y over d time points. Each such trajectory may be interpreted as the realization of augmented, d–dimensional state vector for our observable—which we will refer to as the delay vector h(t). The rows of H then characterize the evolution of the observable in this d–dimensional state space.

We initially construct H as a high-dimensional (and rank-deficient) matrix to ensure it covers a sufficiently large span to embed the manifold. We subsequently reduce the dimensionality of this matrix to improve conditioning and reduce noise. Dimensionality reduction is carried out in two steps—first, through projection onto an orthogonal set of basis vectors (below), and subsequently through nonlinear dimensionality reduction via a neural network (detailed in the next section).

For the initial projection, we note that the leading left eigenvectors of H converge to Legendre polynomials in the limit of short delay windows [104]. Accordingly, we use the first r = 10 discrete Legendre polynomials as the basis vectors of an orthogonal projection matrix:

| (4) |

(polynomials obtained from the special.legendre function in SciPy [105]). We apply this projection to the Hankel matrix constructed from a pupil diameter timecourse. The resulting matrix may be considered as an augmented observable :

| (5) |

whose columns are the projections of the delay vectors onto the leading r Legendre polynomials. These Legendre coordinates [104] form the input to the neural network encoder.

The dimensionality of H is commonly reduced through the singular value decomposition (SVD) (e.g., [45, 106]. In practice, we find that projection onto Legendre polynomials yields marginal improvements over SVD of H, particularly in the low-data limit [104]. However, an additional advantage of the Legendre polynomials is that they provide a universal, analytic basis in which to represent the dynamics; this property is exploited for comparisons across mice and datasets.

Choice of delay embedding parameters was guided on the basis of autocorrelation time and attractor reconstruction quality (i.e., unfolding the attractor while maximally preserving geometry), following decomposition of H. The number of delay coordinates was guided based upon asymptoting reconstruction performance using a linear regression model. For all main text analyses, the Hankel matrix was constructed with d = 100 time delays, each separated by Δt = 3 time steps (i.e., successive rows of H are separated by 3 temporal samples). As all time series were analyzed at a sampling frequency of 20 Hz, this amounts to a maximum delay window of 100 × 3 × .05 = 15 seconds.

For all modeling, pupil diameter was first shifted in time to accommodate physiological delay between the neural signals and the pupil. This time shift was selected as the abscissa corresponding to the peak of the cross-correlation function (between 1 – 2 s for all mice).

State-space mappings: variational autoencoder

To interrelate observables through this state-space framework (and thus, through arousal dynamics), we wish to approximate the target functions

| (6) |

| (7) |

i.e., mappings from the delay vectors hi(t) (i.e., columns of the Hankel matrix constructed from a scalar observable yi) to the arousal latent space (part of which is provided by the intermediate projection matrix P(r)); and from this latent space to a second observable yj. A variety of linear and nonlinear methods can be used for this purpose (e.g., see [58]). Our primary results are obtained through a probabilistic modeling architecture based upon the variational autoencoder (VAE) [61, 107].

Briefly, a VAE is a deep generative model comprising a pair of neural networks (i.e., an encoder and decoder) that are jointly trained to map data observations to the mean and variance of a latent distribution (via the encoder), and to map random samples from this latent distribution back to the observation space (decoder). Thus, the VAE assumes that data observations y are taken from a distribution over some latent variable z, such that each data point is treated as a sample from the prior distribution pθ(z), typically initialized according to the standard diagonal Gaussian prior, i.e., pθ(z) = N(z|0,I). A variational distribution qφ(z|y) with trainable weights φ is introduced as an approximation to the true (but intractable) posterior distribution p(z|y).

As an autoencoder, qφ(z|y) and pθ(y|z) encode observations into a stochastic latent space, and decode from this latent space back to the original observation space. The training goal is to maximize the marginal likelihood of the observables given the latent states z. This problem is made tractable by instead maximizing an evidence lower-bound (ELBO), such that the loss is defined in terms of the negative ELBO:

| (8) |

where the first term corresponds to the log-likelihood of the data (reconstruction error), and the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence term regularizes the distribution of the latent states qφ(z|y) to be close to that of the prior pθ(z). Under Gaussian assumptions, the first term is simply obtained as the mean squared error, i.e., The KL-term is weighted according to an additional hyperparameter β, which controls the balance between these two losses [108, 109]. Model parameters (φ and θ) can be jointly optimized via stochastic gradient descent through the reparameterization trick [107].

In the present framework, rather than mapping back to the original observation space (or technically, the Legendre coordinates corresponding to the original observable), we use the decoder pθ(y|z) to map from z to a new observation space. In other words, we use a probabilistic encoder and decoder, respectively, to approximate our target functions ψ(h) (along with P(r)) and ϕ(z). Notably, VAE training incorporates stochastic perturbations to the latent space, thus promoting discovery of a smooth and continuous manifold. Such a representation is desirable in the present framework, such that changes within the latent space (which is based on the delay coordinates) are smoothly mapped to changes within the observation spaces [110].

Model training

VAE models were trained with the Adam optimizer [111] (learning rate = .02, number of epochs = 200, batch size = 1000 samples) with the KL divergence weight gradually annealed to a factor of 0.1 (mitigating posterior collapse [108, 112]). The latent space Gaussian was initialized with σ = .1. The encoder (a single-layer feedforward neural network with tanh activations) mapped from the leading Legendre coordinates (5) to (the mean and variance of) an m-dimensional latent space (m = 4 unless otherwise stated). The decoder from this latent space was instantiated as a feedforward neural network comprising a layer of 10 hidden units with tanh activations and a linear read-out layer matching the image dimensionality). To generate predicted trajectories, we simply feed the mean output from the encoder (i.e., q(μz|y)) through the decoder to (deterministically) generate the maximum a posteriori estimate.

Hyperparameters pertaining to delay embedding and the VAE were primarily selected by examining expressivity and robustness within the training set of a subset of mice. For reported analyses, all such hyperparameters were kept fixed across all mice and modalities to mitigate overfitting.

Model evaluation

All widefield models were trained on the first 5 minutes of data for each mouse, and we report model performance on the final 3.5 minutes of the 10-minute session. For analyses reporting “Total variance” explained (Figs 2A and 3C, upper), we simply report the R2 value over the full 128×128 image across the held-out time points. To examine variance explained beyond the first principal component (Figs. 2B and 3C, lower), we compute the singular value decomposition (SVD) on the widefield data from the training set Y = USVT and, after training, project the original and reconstructed widefield data from the test set onto all but the first spatial component (i.e, U2:N) prior to computing R2 values. The matrices from this SVD are also used for Figs. S1 and S3–S5.

To evaluate the capacity for prediction of widefield dynamics (i.e., temporal derivatives) (Fig. 2C) and mean-subtracted image frames (Fig. 2D), we first performed temporal differentiation or global mean timecourse subtraction on the original data, then trained models to predict the resulting image frames (following the same train-test split).

For the shuffled control analysis (Fig. S6), we examined total variance explained in widefield data from the test set (as in Fig. 2A), except that for each mouse we swapped the original pupil diameter timecourse with one from each of the other six mice (i.e., we shuffled pupil diameter and widefield calcium data series across mice).

Clustering and decoding analysis

We used Gaussian mixture models (GMMs) to probabilistically assign each (variance-normalized) image frame to one of k clusters (parameterized by the mean and covariance of a corresponding multivariate Gaussian) in an unsupervised fashion. This procedure enables assessment of the spatial specificity of cortical patterns predicted by arousal dynamics, with increasing number of clusters reflecting increased spatial specificity. Probabilistic assignments enable thresholding based upon the confidence of the assignment (posterior probability), such that classification accuracy is not penalized by image frames that whose ground truth value is ambiguous.

Briefly, a GMM models the observed distribution of feature values x as coming from some combination of k Gaussian distributions:

| (9) |

where μi and Σi are the mean and covariance matrix of the ith Gaussian, respectively, and πi is the probability of x belonging to the ith Gaussian (i.e., the Gaussian weight). We fit the mean, covariance, and weight parameters through the standard expectation-maximization algorithm (EM) as implemented in the GMM package available in scikit-learn [113]. This procedure results in a posterior probability for each data point’s membership to each of the k Gaussians (also referred to as the “responsibility” of Gaussian i for the data point); (hard) clustering can then be performed by simply assigning each data point to the Gaussian cluster with maximal responsibility.

To apply this procedure toward widefield image clustering, we begin by subtracting from each pixel the global mean timecourse, then scaling each pixel to unit variance over the course of the run. Then, for each mouse and each number of clusters k, the GMM was fit using ground truth image frames from the training set (using a uniform prior with spherical Gaussians) and used to predict the labels (clusters) for ground truth frames from the test set. For all analyses shown in Fig. 2C, assignments with confidence < 95% confidence were discarded, preserving 80% of all frames in the test set.

After obtaining these “ground truth” cluster assignments, classifiers were trained to predict cluster assignments from widefield data reconstructed under the “latent model”, using data from the training set. The classifier then predicted cluster assignments using reconstructed widefield data from the test set. A similar procedure was used for the “No embedding” model. We used a nonlinear classifier (K-nearest-neighbors) for the latter model, which we found to yield marginally superior performance over a linear classifier. For the latent model we simply used a linear classifier (linear discriminant analysis), as a nonlinear decoder was already employed during training.

Multi-dataset integration

To extend our framework to an independent set of observables, we train our architecture on concatenated time series from all available recordings through the Allen Institute Brain Observatory dataset (N = 18 mice). For visualization purposes, we seek to learn a group-level two-dimensional embedding (i.e., ) based upon delay embedded pupil measurements. After group-level training, we freeze the weights of this encoder and retrain the decoders independently for each mouse, enabling individual-specific predictions for the Allen Institute mice from a common (i.e., group-level) latent space. We further apply these encoder weights to delay embedded pupil observations from the original “WashU” dataset, once again retraining mouse-specific decoders to reconstruct observables from the common latent space.

Once trained, this procedure results in a generative model p(yi,z), which we use to express the posterior probability of each observable yi as a function of position within a common 2D latent space z (note that this formulation does not seek a complete generative model capturing all joint probabilities among the observables). This allows us to systematically evaluate the expectation for each observable over a grid of points in the latent space. Fig. 4 represents this expectation, averaged over decoder models trained for each mouse.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the Allen Institute for the publicly available data used in this study. We also thank Trevor Voss for assistance with the optical setup. The mouse cartoon in Figs. 1 & 3 is adapted from [114], obtained from SciDraw.io.

Funding:

R.V.R was supported by the Shanahan Family Foundation Fellowship at the Interface of Data and Neuroscience at the Allen Institute and the University of Washington, supported in part by the Allen Institute. This research was additionally supported by the American Heart Association grant 20PRE34990003 (Z.P.R.); National Institutes of Health grants R01NS126326 (A.Q.B), R01NS102870 (A.Q.B), RF1AG07950301 (A.Q.B.), R37NS110699 (J.M.L), R01NS084028 (J.M.L.), and R01NS094692 (J.M.L.); and the National Science Foundation AI Institute in Dynamic Systems grant 2112085 (J.N.K. and S.L.B.).

Funding Statement

R.V.R was supported by the Shanahan Family Foundation Fellowship at the Interface of Data and Neuroscience at the Allen Institute and the University of Washington, supported in part by the Allen Institute. This research was additionally supported by the American Heart Association grant 20PRE34990003 (Z.P.R.); National Institutes of Health grants R01NS126326 (A.Q.B), R01NS102870 (A.Q.B), RF1AG07950301 (A.Q.B.), R37NS110699 (J.M.L), R01NS084028 (J.M.L.), and R01NS094692 (J.M.L.); and the National Science Foundation AI Institute in Dynamic Systems grant 2112085 (J.N.K. and S.L.B.).

References

- 1.McCormick D. A., Nestvogel D. B. & He B. J. Neuromodulation of Brain State and Behavior. Annual Review of Neuroscience 43, 391–415. issn: 0147–006X, 1545–4126. doi: 10.1146/annurevneuro-100219-105424 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buzsáki G. The Brain from Inside Out Type: Book (Oxford University Press, New York, NY, USA, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raichle M. E. The restless brain: how intrinsic activity organizes brain function. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 370, 20140172. issn: 0962–8436, 1471–2970. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0172 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engel A. K., Gerloff C., Hilgetag C. C. & Nolte G. Intrinsic Coupling Modes: Multiscale Interactions in Ongoing Brain Activity. Neuron 80, 867–886. issn: 08966273. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.038 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nir Y. & de Lecea L. Sleep and vigilance states: Embracing spatiotemporal dynamics. Neuron. issn: 0896–6273. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2023.04.012 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greene A. S., Horien C., Barson D., Scheinost D. & Constable R. T. Why is everyone talking about brain state? Trends in Neurosciences 0. Publisher: Elsevier. issn: 0166–2236, 1878–108X. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2023.04.001 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stringer C. et al. Spontaneous behaviors drive multidimensional, brainwide activity. Science 364, eaav7893. issn: 0036–8075, 1095–9203. doi: 10.1126/science.aav7893 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimaoka D., Harris K. D. & Carandini M. Effects of Arousal on Mouse Sensory Cortex Depend on Modality. Cell Reports 22, 3160–3167. issn: 22111247. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.02.092 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Musall S., Kaufman M. T., Juavinett A. L., Gluf S. & Churchland A. K. Single-trial neural dynamics are dominated by richly varied movements. Nature Neuroscience 22, 1677–1686. issn: 1097–6256, 1546–1726. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0502-4 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan H. S. & Zimmer M. Brain-wide representations of ongoing behavior: a universal principle? Current Opinion in Neurobiology 64, 60–69. issn: 09594388. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2020.02.008 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salkoff D. B., Zagha E., McCarthy E. & McCormick D. A. Movement and Performance Explain Widespread Cortical Activity in a Visual Detection Task. Cerebral Cortex 30, 421–437. issn: 1047–3211, 1460–2199. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhz206 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X., Leopold D. A. & Yang Y. Single-neuron firing cascades underlie global spontaneous brain events. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, e2105395118. issn: 0027–8424, 1091–6490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2105395118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drew P. J., Winder A. T. & Zhang Q. Twitches, Blinks, and Fidgets: Important Generators of Ongoing Neural Activity. The Neuroscientist 25, 298–313. issn: 1073–8584, 1089–4098. doi: 10.1177/1073858418805427 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadeh S. & Clopath C. Contribution of behavioural variability to representational drift. eLife 11 (eds Palmer S. E., Frank M. J. & Ziv Y.) Publisher: eLife Sciences Publications, Ltd, e77907. issn: 2050–084X. doi: 10.7554/eLife.77907 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zagha E. et al. The Importance of Accounting for Movement When Relating Neuronal Activity to Sensory and Cognitive Processes. The Journal of Neuroscience 42, 1375–1382. issn: 0270–6474, 1529–2401. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1919-21.2021 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahneman D. Attention and effort First Edition. 246 pp. isbn: 978-0-13-050518-7 (Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J, 1973). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andrew R. J. Arousal and the Causation of Behaviour. Behaviour 51. Publisher: Brill, 135–165. issn: 0005–7959 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calderon D., Kilinc M., Maritan A., Banavar J. & Pfaff D. Generalized CNS arousal: An elementary force within the vertebrate nervous system. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 68, 167–176. issn: 01497634. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.05.014 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dampney R. A. L. Central neural control of the cardiovascular system: current perspectives. Advances in Physiology Education 40. Publisher: American Physiological Society, 283–296. issn: 1043–4046. doi: 10.1152/advan.00027.2016 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rasmussen R., O’Donnell J., Ding F. & Nedergaard M. Interstitial ions: A key regulator of state-dependent neural activity? Prog Neurobiol 193. Type: Journal Article, 101802. issn: 1873–5118. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2020.101802 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roeder T. The control of metabolic traits by octopamine and tyramine in invertebrates. Journal of Experimental Biology 223, jeb194282. issn: 0022–0949. doi: 10.1242/jeb.194282 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin C. G., He B. J. & Chang C. State-related neural influences on fMRI connectivity estimation. NeuroImage 244, 118590. issn: 1053–8119. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118590 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGinley M. J. et al. Waking State: Rapid Variations Modulate Neural and Behavioral Responses. Neuron 87, 1143–1161. issn: 08966273. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.012 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mann K., Deny S., Ganguli S. & Clandinin T. R. Coupling of activity, metabolism and behaviour across the Drosophila brain. Nature 593, 244–248. issn: 0028–0836, 1476–4687. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03497-0 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fox M. D. & Raichle M. E. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 8, 700–711. issn: 1471–003X, 14710048. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pais-Roldán P. et al. Contribution of animal models toward understanding resting state functional connectivity. NeuroImage 245, 118630. issn: 1053–8119. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118630 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grandjean J. et al. A consensus protocol for functional connectivity analysis in the rat brain. Nature Neuroscience 26. Number: 4 Publisher: Nature Publishing Group, 673–681. issn: 1546–1726. doi: 10.1038/s41593-023-01286-8 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cabral J., Kringelbach M. L. & Deco G. Functional connectivity dynamically evolves on multiple time-scales over a static structural connectome: Models and mechanisms. NeuroImage 160, 84–96. issn: 10538119. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.03.045 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reid A. T. et al. Advancing functional connectivity research from association to causation. Nature Neuroscience 22, 1751–1760. issn: 1097–6256, 1546–1726. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0510-4 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suárez L. E., Markello R. D., Betzel R. F. & Misic B. Linking Structure and Function in Macroscale Brain Networks. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 24, 302–315. issn: 13646613. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2020.01.008 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gu Y., Han F. & Liu X. Arousal Contributions to Resting-State fMRI Connectivity and Dynamics. Frontiers in Neuroscience 13, 1190. issn: 1662–453X. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.01190 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gutierrez-Barragan D. et al. Unique spatiotemporal fMRI dynamics in the awake mouse brain. Current Biology 32, 631–644.e6. issn: 09609822. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.12.015 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.West S. L. et al. Wide-Field Calcium Imaging of Dynamic Cortical Networks during Locomotion. Cerebral Cortex 32, 2668–2687. issn: 1047–3211. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhab373 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shahsavarani S. et al. Cortex-wide neural dynamics predict behavioral states and provide a neural basis for resting-state dynamic functional connectivity. Cell Reports 42. Publisher: Elsevier. issn: 2211–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112527 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Power J. D., Plitt M., Laumann T. O. & Martin A. Sources and implications of whole-brain fMRI signals in humans. NeuroImage 146, 609–625. issn: 10538119. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.09.038 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turchi J. et al. The Basal Forebrain Regulates Global Resting-State fMRI Fluctuations. Neuron 97, 940–952.e4. issn: 08966273. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.01.032 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Özbay P. S. et al. Sympathetic activity contributes to the fMRI signal. Communications Biology 2, 421. issn: 2399–3642. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0659-0 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bolt T. S. et al. A Unified Physiological Process Links Global Patterns of Functional MRI, Respiratory Activity, and Autonomic Signaling Pages: 2023.01.19.524818 Section: New Results. 2023. doi: 10.1101/2023.01.19.524818. [DOI]

- 39.Raut R. V. et al. Global waves synchronize the brain’s functional systems with fluctuating arousal. Science Advances 7, eabf2709. issn: 2375–2548. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abf2709 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takens F. Detecting strange attractors in turbulence. Lecture Notes in Mathematics 898, 366–381 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stark J., Broomhead D. S., Davies M. E. & Huke J. Takens embedding theorems for forced and stochastic systems. Nonlinear Analysis: Theory, Methods & Applications. Proceedings of the Second World Congress of Nonlinear Analysts 30, 5303–5314. issn: 0362–546X. doi: 10.1016/S0362-546X(96)00149-6 (1997). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sugihara G. et al. Detecting Causality in Complex Ecosystems. Science 338, 496–500. issn: 00368075, 1095–9203. doi: 10.1126/science.1227079 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brunton S. L. & Kutz J. N. Data-Driven Science and Engineering: Machine Learning, Dynamical Systems, and Control 2nd (Cambridge University Press, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brunton S. L., Budišić M., Kaiser E. & Kutz J. N. Modern Koopman Theory for Dynamical Systems. SIAM Review 64, 229–340. issn: 0036–1445, 1095–7200. doi: 10.1137/21M1401243 (2022). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brunton S. L., Brunton B. W., Proctor J. L., Kaiser E. & Kutz J. N. Chaos as an intermittently forced linear system. Nature Communications 8, 19. issn: 2041–1723. doi: 10.1038/s41467-01700030-8 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X. et al. Dual fluorophore imaging combined with optical intrinsic signal to acquire neural, metabolic and hemodynamic activity in Neural Imaging and Sensing 2022 Neural Imaging and Sensing 2022. PC11946 (SPIE, 2022), PC119460L. doi: 10.1117/12.2609860. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reitman M. E. et al. Norepinephrine links astrocytic activity to regulation of cortical state. Nature Neuroscience 26. Number: 4 Publisher: Nature Publishing Group, 579–593. issn: 1546–1726. doi: 10.1038/s41593-023-01284-w (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bich L., Mossio M., Ruiz-Mirazo K. & Moreno A. Biological regulation: controlling the system from within. Biology & Philosophy 31, 237–265. issn: 0169–3867, 1572–8404. doi: 10.1007/s10539-015-9497-8 (2016). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berntson G. G., Cacioppo J. T. & Quigley K. S. Autonomic determinism: The modes of autonomic control, the doctrine of autonomic space, and the laws of autonomic constraint. Psychological Review 98, 459–487. issn: 1939–1471, 0033–295X. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.98.4.459 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schöner G. & Kelso J. A. S. Dynamic Pattern Generation in Behavioral and Neural Systems. Science 239, 1513–1520. issn: 0036–8075, 1095–9203. doi: 10.1126/science.3281253 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Givon D., Kupferman R. & Stuart A. Extracting macroscopic dynamics: model problems and algorithms. Nonlinearity 17, R55–R127. issn: 0951–7715, 1361–6544. doi: 10.1088/0951-7715/17/6/R01 (2004). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haken H. Information and Self-Organization isbn: 978-3-540-33021-9. doi: 10.1007/3-540-33023-2 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2006). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bertalanffy L. v. General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications Second Printing edition. 289 pp. (George Braziller, 1969). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Macke J. H. et al. Empirical models of spiking in neural populations in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 24 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mannino M. & Bressler S. L. Foundational perspectives on causality in large-scale brain networks. Phys Life Rev 15. Type: Journal Article, 107–23. issn: 1873–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.plrev.2015.09.002 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mezić I. Spectral properties of dynamical systems, model reduction and decompositions. Nonlinear Dynamics 41, 309–325 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rulkov N. F., Sushchik M. M., Tsimring L. S. & Abarbanel H. D. I. Generalized synchronization of chaos in directionally coupled chaotic systems. Physical Review E 51, 980–994. issn: 1063–651X, 1095–3787. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.51.980 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abarbanel H. D. I., Carroll T. A., Pecora L. M., Sidorowich J. J. & Tsimring L. S. Predicting physical variables in time-delay embedding. Physical Review E 49. Publisher: American Physical Society, 1840–1853. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.49.1840 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mitra A. et al. Spontaneous Infra-slow Brain Activity Has Unique Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Laminar Structure. Neuron 98, 297–305.e6. issn: 08966273. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.03.015 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Okun M., Steinmetz N. A., Lak A., Dervinis M. & Harris K. D. Distinct Structure of Cortical Population Activity on Fast and Infraslow Timescales. Cerebral Cortex 29, 2196–2210. issn: 1047–3211, 1460–2199. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhz023 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kingma D. P. & Welling M. An Introduction to Variational Autoencoders. Foundations and Trends® in Machine Learning 12, 307–392. issn: 1935–8237, 1935–8245. doi: 10.1561/2200000056.arXiv:1906.02691[cs,stat] (2019). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Majeed W. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of low frequency BOLD fluctuations in rats and humans. NeuroImage 54, 1140–1150. issn: 10538119. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.08.030 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gozzi A. & Schwarz A. J. Large-scale functional connectivity networks in the rodent brain. NeuroImage 127, 496–509. issn: 10538119. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.12.017 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barson D. et al. Simultaneous mesoscopic and two-photon imaging of neuronal activity in cortical circuits. Nature Methods 17, 107–113. issn: 1548–7091, 1548–7105. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0625-2 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zuend M. et al. Arousal-induced cortical activity triggers lactate release from astrocytes. Nature Metabolism 2, 179–191. issn: 2522–5812. doi: 10.1038/s42255-020-0170-4 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schaeffer S. & Iadecola C. Revisiting the neurovascular unit. Nature Neuroscience 24, 1198–1209. issn: 1097–6256, 1546–1726. doi: 10.1038/s41593-021-00904-7 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kolenc O. I. & Quinn K. P. Evaluating Cell Metabolism Through Autofluorescence Imaging of NAD(P)H and FAD. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 30, 875–889. issn: 1523–0864, 1557–7716. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7451 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shvets-Ténéta-Gurii T. B., Troshin G. I. & Dubinin A. G. Changes in the redox potential of the rabbit cerebral cortex accompanying episodes of ECoG arousal during slow-wave sleep. Neuroscience and Behavioral Physiology 38, 63–70. issn: 1573–899X. doi: 10.1007/s11055-008-0009-z (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen J. E. et al. Resting-state “physiological networks”. NeuroImage 213, 116707. issn: 10538119. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116707 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dabagia M., Kording K. P. & Dyer E. L. Aligning latent representations of neural activity. Nature Biomedical Engineering. Publisher: Nature Publishing Group, 1–7. issn: 2157–846X. doi: 10.1038/s41551-022-00962-7 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Siegle J. H. et al. Survey of spiking in the mouse visual system reveals functional hierarchy. Nature. issn: 0028–0836, 1476–4687. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03171-x (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jun J. J. et al. Fully integrated silicon probes for high-density recording of neural activity. Nature 551, 232–236. issn: 0028–0836, 1476–4687. doi: 10.1038/nature24636 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nestvogel D. B. & McCormick D. A. Visual thalamocortical mechanisms of waking state-dependent activity and alpha oscillations. Neuron 110, 120–138.e4. issn: 08966273. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2021.10.005 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Williams M. O., Rowley C. W., Mezić I. & Kevrekidis I. G. Data fusion via intrinsic dynamic variables: An application of data-driven Koopman spectral analysis. Europhysics Letters 109. Publisher: EDP Sciences, IOP Publishing and Società Italiana di Fisica, 40007. issn: 0295–5075. doi: 10.1209/0295-5075/109/40007 (2015). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hirsh S. M., Ichinaga S. M., Brunton S. L., Nathan Kutz J. & Brunton B. W. Structured time-delay models for dynamical systems with connections to Frenet–Serret frame. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 477, 20210097. issn: 1364–5021, 1471–2946. doi: 10.1098/rspa.2021.0097 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]