Abstract

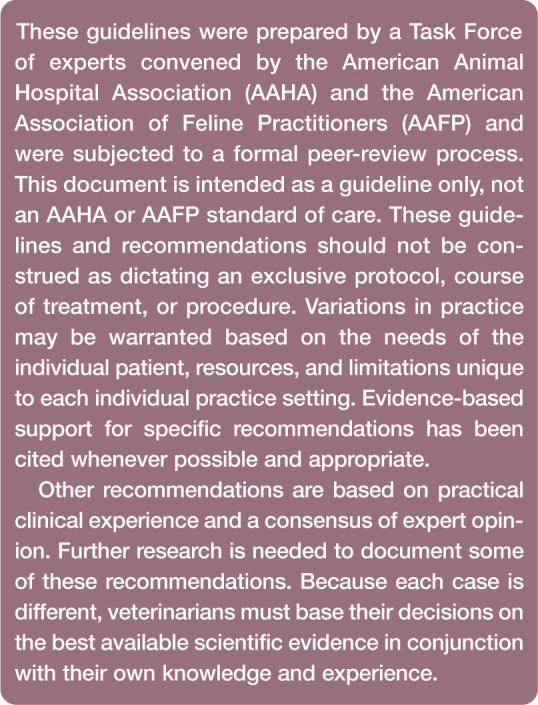

The guidelines, authored by a Task Force of experts in feline clinical medicine, are an update and extension of the AAFP–AAHA Feline Life Stage Guidelines published in 2010. The guidelines are published simultaneously in the Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery (volume 23, issue 3, pages 211–233, DOI: 10.1177/1098612X21993657) and the Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association (volume 57, issue 2, pages 51–72, DOI: 10.5326/JAAHA-MS-7189). A noteworthy change from the earlier guidelines is the division of the cat’s lifespan into a five-stage grouping with four distinct age-related stages (kitten, young adult, mature adult, and senior) as well as an end-of-life stage, instead of the previous six. This simplified grouping is consistent with how pet owners generally perceive their cat’s maturation and aging process, and provides a readily understood basis for an evolving, individualized, lifelong feline healthcare strategy. The guidelines include a comprehensive table on the components of a feline wellness visit that provides a framework for systematically implementing an individualized life stage approach to feline healthcare. Included are recommendations for managing the most critical health-related factors in relation to a cat’s life stage. These recommendations are further explained in the following categories: behavior and environmental needs; elimination; life stage nutrition and weight management; oral health; parasite control; vaccination; zoonoses and human safety; and recommended diagnostics based on life stage. A discussion on overcoming barriers to veterinary visits by cat owners offers practical advice on one of the most challenging aspects of delivering regular feline healthcare.

Keywords: Feline life stage, kitten, adult, senior, veterinary, healthcare examination, medical history, behavior, risk assessment, elimination

Introduction

The feline patient’s life stage is the most fundamental presentation factor the practitioner encounters in a regular examination visit. Most of the components of a treatment or healthcare plan are guided by the patient’s life stage, progressing from kitten to young adult, mature adult, and senior and concluding with the end-of-life stage. Because a cat can transition from one life stage to another in a short period of time, each examination visit should include a life stage assessment. The “2021 AAHA/AAFP Feline Life Stage Guidelines” provide a comprehensive age-associated framework for promoting health and longevity throughout a cat’s lifetime. The guidelines were developed by a Task Force of experts in feline clinical medicine. Their recommendations are a practical resource to guide individualized risk assessment, preventive healthcare strategies, and treatment pathways that evolve as the cat matures.

An evidence-guided framework for managing a cat’s healthcare throughout its lifetime has never been more important in feline practice than it is now. Cats are the most popular pet in the United States. 1 A great anomaly in feline practice is that although most owners consider their cats to be family members, cats are substantially underserved in the primary care setting compared with dogs. 2 In 2006, owners took their dogs to veterinarians more than twice as often as cats: 2.3 times/year for dogs versus 1.1 times/year for cats. 3 This healthcare use imbalance persists to the present day. Cat owners often express a belief that their pets “do not need medical care.” Two reasons for this misconception are that signs of illness and pain are often difficult to detect in the sometimes reclusive or stoic cat, and that cats are perceived to be self-sufficient.

Specific objectives of the guidelines are (1) to define distinct feline life stages consistent with how pet owners generally perceive their cat’s maturation and aging process, and (2) to provide a readily understood basis for an evolving, individualized, lifelong healthcare strategy for each feline patient at every life stage. In this regard, the Task Force has identified certain common features of each feline life stage that provide an incentive for regular healthcare visits and inform a patient-specific healthcare approach. These life stage characteristics are defined in a comprehensive table listing the client discussion topics and action items for each feline life stage. In effect, the table defines what needs to be done at each life stage. This prescriptive approach to healthcare management based on a cat’s life stage is explained and justified in the well-referenced narrative that makes up the rest of the guidelines. The Task Force considers end of life and its precursor events to be a separate feline life stage. Rather than discussing end of life in these guidelines, practitioners can access this topic in previously published “2016 AAHA/IAAHPC End-of-Life Care Guidelines” 4 and the “2021 AAFP End of Life Online Educational Toolkit”. 5

A recurring emphasis throughout the guidelines is the importance of feline-friendly handling techniques in the waiting area and examination settings. Using feline-friendly handling is a critical factor in eliminating the barriers to regular feline healthcare. This patient-centric approach can reduce the cat’s stress, improve handler safety, and create a more positive experience for the patient, client, and care provider. Together, these outcomes have the potential to increase the frequency of feline examination visits and improve compliance with preventive healthcare recommendations.

These guidelines complement and update earlier feline life stage guidelines published in 2010. 6 An important distinction of the 2021 guidelines is the Task Force’s decision to reduce the number of feline life stages from six to four distinct age-related stages as well as an end-of-life stage (five stages overall; Table 1). Although the physiologic basis for six feline life stages remains valid, a five-stage grouping makes clinical protocols easier to implement and simplifies the dialog between the practice team and cat owners. In this regard, the guidelines are not only a useful resource for practitioners but also the basis for client education that is tailored to the feline patient’s life stage progression.

Table 1.

Feline life stages

|

Image © Vorenl/iStock, spxChrome/E+, AaronAmat/iStock, AngiePhotos/iStock via Getty Images Plus

The items to perform or discuss during each life stage are highlighted in Table 2. Veterinary professionals should use this table to identify the differences between each life stage. The text in the rest of the guidelines document identifies select areas in the table that warrant further explanation, but is not intended as a comprehensive review.

Table 2.

Items to perform or discuss during each life stage (continued on page 214)

| ALL CATS NEED A FULL THOROUGH PHYSICAL EXAMINATION | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kitten (birth up to 1 year) | Young adult (1–6 years) | Mature adult (7–10 years) Senior (>10 years) | ||

| Discussion items for all life stages | • Frequency of visits: minimum of annual examinations and at least every 6 months for seniors • Educate the client on: - The subtle signs of behavior, illness, pain, and anxiety - Normal feline behaviors and the significance of changes in the cat’s behavior - The importance of preventive healthcare and carrier acclimation - Disaster preparedness - Identification options such as microchipping - Sterilization - Claw care, natural scratching behavior, and alternatives to declawing • Discuss elimination habits and any house-soiling • Present pet insurance and financial planning options • Obtain previous medical/surgical history (including medications and supplements) • Evaluate personality and temperament; make recommendations for optimal future examinations • Evaluate patient demeanor to determine the appropriate approach to the physical examination • Ask about daily food and water intake • Discuss diets and feeding as well as make recommendations • Assess and discuss quality of life when clinically relevant • Veterinarians should familiarize themselves with common breed predispositions |

|||

| Medical history | • Discuss breed healthcare predispositions and congenital/genetic concerns | • Ask about vomiting, vomiting hairballs, and diarrhea • Ask about changes in grooming habits • Ask about changes in behavior |

• Ask about changes in appetite and hydration • Ask about polyuria, polydipsia, vomiting, and diarrhea • Ask about increased nocturnal activity and vocalization • Discuss early signs of cognitive decline • Ask about changes in mobility • Ask about changes in vision • Ask about changes in grooming habits • Ask about masses |

|

| Examination focus (extra attention during physical examination) | • Discuss congenital/genetic findings (murmurs, hernias, and dentition) • Discuss infectious disease |

• Increase focus on cardiorespiratory and dermatologic findings • Focus on oral examination to detect periodontal disease and tooth resorption |

• Increase focus on oral examination, abdominal palpation, and ophthalmic (fundic), cardiorespiratory, and musculoskeletal examination • Concentrate on thyroid gland and kidney palpation • Conduct thorough pain assessment |

|

| • Record body weight, BCS, and MCS • Consider (dorsal and lateral) photographs of patient to help identify future changes • Monitor for changes in usual patient demeanor • Record successful feline-friendly handling techniques and preferences | ||||

| Nutrition and weight management | • Discuss diet, quantity being fed, intake amounts, and frequency of feeding • Introduce variety of food flavors and textures • Introduce food foraging toys and puzzles |

• Monitor for weight gain • Discuss obesity risks • Provide ongoing advice for enrichment, play, and exercise |

• Monitor for weight loss and weight gain • Discuss diseases associated with changes in appetite or weight • Discuss use of appropriate therapeutic diets |

|

| • Feed to ideal BCS and MCS | ||||

| Behavior and environment | • Discuss importance of: - Introducing kittens to various people and pets during the socialization period - Acclimating to handling, brushing, nail trimming, grooming, and medication administration - Acclimating to carrier, car, and veterinary visits - Discourage use of hands or feet as toys during play to avoid risk of future aggressive behavior • Encourage teaching cue/response, such as come or sit, using positive reinforcement |

• Discuss that intercat interactions may decline • Discuss that intercat or human-cat relationships may change with maturity or following stressful events • Encourage acceptance of manipulation of mouth, ears, and feet by providing gentle handling |

• Environmental needs may change: ensure good/easy accessibility to litter box, warm soft bed, food/water • Educate clients about subtle behavior changes that are not “just old age” • Monitor cognitive function |

|

| • Ensure number, distribution, and location of resources is adequate | ||||

| • Discuss importance of number, distribution, and location of resources for each cat in the home • Ask about housing (indoor/outdoor/partial outdoor access), hunting activity, and children and other pets in the home • Discuss housemate cats and their usual interactions. Ask if there are any concerns • Ask about problematic or changes in behavior • Ensure environmental needs of the cat(s) are met (toys, scratching posts, resting places, play) • Discuss managing unwanted behaviors; discourage punishment and encourage positive reinforcement |

||||

| Elimination | • Discuss litter box setup, cleaning, and normal elimination behavior • Start with unscented clumping sand litter and/or the litter type the kitten was previously using • Allow kittens to choose litter preference by offering a variety of litter types |

• Confirm that litter box size (length and height) accommodates the growing cat | • Review the location of the litter boxes to avoid stairs for painful cats including those with DJD • Review and adjust litter box size (length and height), location, and cleaning regimens as necessary |

|

| • Discuss elimination habits • Ask if any urination or defecation occur outside the litter box - Distinguish between toileting and marking behaviors • Discuss litter box management (number, size, location, litter type, and cleaning) • Educate clients about how to assess stool appearance and litter ball size | ||||

| Oral health | • Acclimate to mouth handling and brushing/wiping of teeth • Examine for malocclusion or developmental dental issues |

• Recommend dental diet if clinically indicated | • Monitor for oral tumors, inability to eat and decreased quality of life from painful dental disease | |

| • Perform detailed dental examination; discuss dental disease, preventive healthcare, dental prophylaxis, and importance of treatment/home care with brushing/wiping of teeth | ||||

| Parasite control | • Assess risks of exposure based on lifestyle, geographic location, and travel • Educate clients that even indoor-only cats have a real risk for parasitic infections • Recommend year-round broad-spectrum antiparasitics with efficacy against heartworms, intestinal parasites, and fleas for all patients, regardless of indoor/outdoor status • Recommend tick control as indicated by risk assessment • Perform fecal examination as appropriate • Discuss and mitigate zoonotic risks |

|||

| Vaccination | • FCV, FHV-1, FPV, FeLV, and rabies are considered core vaccines. The interval between the initial series vaccines varies depending on the infectious disease, age at initial vaccination, vaccine label, type of vaccine (inactivated, attenuated live, and recombinant), and route of administration (parenteral versus intranasal) • FCV, FHV-1, and FPV revaccination is administered at 6 months of age 7 |

• FCV, FHV-1, FPV, and rabies are considered core vaccines. Ongoing FeLV vaccination is based on risk assessment of exposure to infected cats. Intervals between FCV, FHV-1, and FPV revaccinations depend on vaccine label, type of vaccine, route of administration, and risk assessment • Cats should be revaccinated 12 months after the last dose in the kitten series, and then annually for cats at high risk 7 |

• The risk/benefit of vaccinating senior cats should be carefully considered in the light of their overall health status. Where appropriate, FCV, FHV-1, FPV, and rabies are considered core vaccines for healthy seniors. FeLV vaccination is based on risk assessment | |

| • For rabies vaccinations, AAHA and the AAFP recommend following vaccine label instructions and local laws. Chlamydia felis and Bordetella bronchiseptica vaccines are considered non-core vaccines | ||||

Importance of feline-friendly handling

Both AAHA and the AAFP understand that a major barrier to feline veterinary visits is the concern about the level of stress the patient will be experiencing during the visit. There are many recommendations available to help decrease the stress of feline patients during transportation to, and time spent in, the veterinary practice. Unless otherwise specified, the reader should assume that these stress-reduction recommendations and techniques are applicable to all aspects of the veterinary visit at all life stages described in these guidelines.

Safe and gentle handling will reduce the stress response of the patient. By applying feline-friendly handling techniques, the team can proactively perform the entire examination and diagnostic procedures in a way that improves patient comfort and time efficiency as well as the patient, client, and practice team experience. In efforts to reduce stress, keep the most invasive parts until the end, such as the dental examination, temperature assessment or nail trim, sample collection, and imaging. It is important to note in the patient record which aspect(s) of the examination may stress that individual cat so those components can be saved until the end during future visits.

Using feline-friendly handling techniques to reduce stress will give the patient and owner a positive experience that will carry over to future examination visits. The patient will often retain this positive conditioning, allowing the practice team to provide the best possible care throughout the cat’s lifetime. A feline-friendly approach will also positively impact the practice team dynamic and confidence when handling, treating, and caring for cats.

Life stage definitions and relevant clinical perspectives

The Task Force has designated four age-related life stages (Table 1): the kitten stage, from birth up to 1 year; young adult, from 1 year through 6 years; mature adult, from 7 to 10 years; and senior, aged over 10 years. The fifth, end-of-life stage can occur at any age. These guidelines focus on the life stages of kitten through to senior. These age designations help to focus attention on the physical and behavioral changes, as well as the evolving medical needs, that occur at different stages of feline life. Examples include detection of congenital defects in kittens, obesity prevention in the young adult cat, and increased vigilance for early detection of renal disease in mature adult and senior cats. It must be recognized, however, that any age groupings are inevitably arbitrary demarcations along a spectrum and not absolutes.

Although ages have been used to identify life stages, it is recognized that there may be significant variation among individual cats. For example, some senior cats aged 10 years and older may remain in excellent physical condition and would be best treated as a mature adult at the veterinarian’s discretion. The guidelines are intended to be a starting point from which individualized care recommendations can be developed.

Discussion items for all life stages

The Task Force recommends a minimum of annual examinations for all cats, with increasing frequency as appropriate for their individual needs. 6 Senior cats should be seen at least every 6 months and more frequently for those with chronic conditions. More information can be found in the “AAFP Senior Care Guidelines”. 12 Seeing patients and clients at least annually provides an excellent opportunity for client education. Table 2 lists a number of discussion items relevant to all life stages. Some topics such as sterilization, claw care, the importance of identification and microchipping, and disaster preparedness may be covered once in an initial consultation. The AAFP Position Statement entitled “Early spay and castration” is a source of further information on timing of pediatric spay/neutering. 13

Open-ended questions and requests such as, “What would you like to discuss with me today?” or, “I hear that [cat’s name] hasn’t been eating well, tell me more about that” are an excellent start to setting the agenda for the consultation. An appointment template can be valuable to guide more specific questions such as, “Has there been any urination or defecation outside the litter box?” to ensure other relevant information is not missed or left to the end of the consultation.

Discussions regarding anticipated costs of care and presentation of pet insurance options can help clients to plan ahead for future care needs. In some cases, estate planning may be appropriate to discuss. Many other topics will be revisited and modified during subsequent examinations, including preventive healthcare and nutritional recommendations. Discussing what normal behaviors are expected at each life stage, relating this to the patient, and reviewing subtle signs of anxiety, illness, and pain in cats encourages clients to be vigilant and seek care early in the course of disease. 14 Veterinarians should educate owners of purebred cats about breed predispositions, keeping in mind that most North American cats are not purebred, and that these conditions are not necessarily restricted to particular breeds. 15

Taking a few moments to evaluate and discuss the temperament, demeanor, and handling preferences of the patient is time well spent in terms of setting the stage for a reduced-stress, thorough physical examination and for obtaining diagnostic samples. Observing how the cat is reacting to the environment may give clues as to its state of arousal. If the cat is a new patient to the veterinarian, the client may know from previous experience what works well for their pet. For example, does the cat relax when handled in a towel? What is the cat’s favorite treat? What handling methods have worked well or poorly in the past? This knowledge and an understanding of reduced-stress handling techniques can help to tailor the approach to each patient. Noting these important details in the physical examination record will facilitate successful, reduced-stress future visits and help to develop individualized approaches that work well for each patient. Decreasing stress may reduce confounding results during physical examination and diagnostic testing, as well as when taking vital signs.

Lifestyle risk assessment

Understanding the lifestyle of the cat is important for making thorough and accurate preventive healthcare and medical recommendations. The traditional classification of a cat as “indoor” or “outdoor” is oversimplified as there may be additional risk factors that warrant consideration. 16 Determining whether the cat is primarily indoor or has any outdoor access is, nevertheless, a starting point. Further questioning may reveal details including whether outdoor access is through an enclosure or leash walking versus free roaming, and if there is exposure to other cats – be they housemates, visiting cats, or foster cats from a shelter – and whether the cat attends boarding facilities or cat shows. For primarily indoor cats, environmental needs are likewise evaluated. Noting human–cat interaction is also important to determine zoonotic risks. 17 For example, a young adult cat hunting outdoors may need different preventive healthcare from a mature adult indoor cat living in a retirement home and interacting with residents. For further information, readers are referred to the “2019 AAFP Feline Zoonoses Guidelines” 17 and the “2020 AAFP Feline Retrovirus Testing and Management Guidelines”. 18 The role and relationship of the cat with respect to the client (i.e., the human–cat bond and the care philosophy of the owner) is also essential to understand.

Medical history and physical examination focus based on specific life stage

For new patients, a detailed history including any previous medical or surgical information is important to record, including any past or current medications or supplements.

An assessment of the cat’s current diet, including intake amount, frequency of feeding, and the manner in which the cat is fed, 19 is an important part of each consultation, as is making a nutritional recommendation to continue or change the current diet.

Evaluation and recording of body weight, body condition score (BCS), and muscle condition score (MCS) are important components of the physical examination at all life stages to allow early detection of changes and identification of trends. 20 Obtaining dorsal and lateral photographs of the patient is recommended to facilitate monitoring BCS/MCS as the cat ages, and can help the owner recognize subtle changes.

Diseases and conditions that require additional focus during the examination by each life stage are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Diseases and conditions that require particular focus during examination, by life stage

| Kitten (birth up to 1 year) | Young adult (1–6 years) | Mature adult (7–10 years) | Senior (<10 years) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diseases and conditions of relevance that require increased vigilance* | • Genetic and congenital conditions • Infectious diseases: parasitic, viral, retroviral, feline infectious peritonitis, upper respiratory infection, enteric • Dermatophytosis |

• Feline bronchial disease • Cardiomyopathy • Chronic enteropathy • FIC and urolithiasis • Feline atopic dermatitis (non-flea, flea allergy dermatitis, non-food allergic dermatitis) • Systemic fungal disease |

• Chronic enteropathies (GI lymphoma, inflammatory bowel disease) • Chronic kidney disease • Hyperthyroidism • Diabetes mellitus • Neoplasia • Cognitive dysfunction syndrome • Periodontal disease and tooth resorption21,22 • DJD: osteoarthritis and spondylosis deformans 23 |

|

This is not intended to represent a comprehensive list

Kittens

Kittens will have different health risks depending on their lifestyle and history, including exposure to other cats and the level of care provided. Vaccination and parasite control history, health status of related cats, if known, and clinical signs of upper respiratory or parasitic disease are all important areas of focus. Nutritional status and weaning history are also important areas of inquiry as orphaned or undersocialized kittens may have behavior concerns. 24 Changes in demeanor, activity level, and behavior are additionally key to note and trend over time.

Asking specific questions as to whether the kitten is displaying any unwanted behaviors, counselling clients on normal kitten behavior, and giving advice on positive methods to modify unwanted behavior are critical discussion points at this stage. Breed-related predispositions, signs of genetic disease, and the availability and accuracy of genetic testing to detect disease should be discussed when relevant.

The physical examination for kittens typically focuses on detection of congenital issues such as a heart murmur, hernia, or cleft palate. A detailed oral examination is performed to detect abnormalities of dentition. The use of fecal scoring charts is very helpful to ensure that the client can accurately identify stool consistency.25,26

Young adult cats

Lower airway disease is common in young adult cats. 27 Coughing is a typical sign of feline bronchial disease; however, the veterinarian must consider the role of heartworm-associated respiratory disease (HARD), transtracheal migration of roundworm (Toxocara cati), and lungworm. Asking specific questions regarding the presence of coughing is helpful for early diagnosis and treatment. Coughing is not typically a hallmark of cardiac disease in cats, in contrast to canine patients, nor is it caused by hairballs. Young adult cats developing cardiac conditions such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy are often asymptomatic or may display changes in activity level or exercise tolerance.

Asking specific questions concerning whether vomiting, vomiting hairballs, or diarrhea is occurring, and the frequency of each, is recommended as some clients may consider vomiting or vomiting hairballs to be normal for their cat. Additionally, discuss the importance of monitoring weight, and ask about any chronic enteropathy or gastrointestinal (GI) signs that could indicate early stages of disease.

Mature adult and senior cats

The medical history and examination of mature adult and senior cats will be focused on early detection of disease. Adult and senior cats are often diagnosed with comorbidities. Specific questions regarding changes in appetite, occurrence of polyuria and polydipsia, vomiting, vomiting hairballs, or diarrhea are of key importance to guide diagnostic testing. Discussion should also be held with the client about increased nocturnal activity and vocalization as well as changes in the cat’s normal habits or activity. These may indicate cognitive dysfunction, disease-reduced mobility, pain, or reduced vision. Detecting signs of pain or anxiety and evaluation of quality of life are most commonly of concern in the mature adult or senior cat but may be relevant at any life stage.

During the physical examination, particular focus is on pain assessment and abdominal and thyroid palpation. A detailed musculo-skeletal examination to detect signs of osteoarthritis is critical as this condition is one of the most significant and underdiagnosed diseases in cats.23,28 A fundic examination is key to detecting signs of ophthalmic disease or hypertension. 29 Practices should employ a validated pain assessment scale or tool to diagnose, monitor, and assist in the evaluation of patients for subtle signs of pain. 30

Changes in grooming habits, particularly increased grooming, may signal a dermatologic issue such as atopy, food allergy, an immune-mediated skin condition, infectious or parasitic disease, endocrine condition, or paraneoplastic syndrome. 31 Reduced grooming by the cat may also indicate underlying illness, bladder pain, degenerative joint disease (DJD) pain, or reduced mobility.

Behavior and environmental needs

Understanding and enhancing behavior by life stage

Feline health and welfare are intricately interrelated at all life stages. From kitten to senior, an appreciation of the behavioral needs of the cat is essential for preventing behavior problems. Problem behaviors may be manifestations of normal feline behaviors, ranging from undesirable to pathological misbehaviors. Such problems continue to be a primary reason for relinquishment. 32 House-soiling (marking or toileting outside the litter box) 33 and aggression toward people, housemate cats, or housemate dogs 34 are commonly reported reasons for relinquishment.

The focus of this section of the guidelines is the identification of key interventions at various life stages. An outline of behavior and ways to enhance the cat’s welfare at each life stage is presented in Table 2. For detailed recommendations about normal cat behavior and management, readers are referred to the “AAFP Feline Behavior Guidelines”. 35

Many of the cat’s natural patterns are consistent with those of their ancestor, the African wild cat. 36 Although cats have become a favored companion around the world, they are not considered fully domesticated. Cats are highly social to those individuals they have experienced positive interactions with during their critical socialization period, while at the same time showing independent daily activities. 37 They use a wide territory in natural settings, quite unlike the limited environments within human homes. Thus, the ideal feline home environment requires plentiful and thoughtfully distributed resources including resting areas, feeding stations, water sources, scratching posts, and litter boxes. 38 Cats develop patterns of resting and hiding in the home that should be complemented by a variety of appealing places. They may naturally seek their preferred hiding spots if startled or fearful. Some cats prefer to go high, which is consistent with the natural behaviors of the African wild cat, whereas other cats retreat to low spaces. 36

Cats are popular pets that reside in 25% of U.S. households with a mean of 1.8 cats per household, 39 a demographic statistic that highlights the importance of understanding often complex feline interrelationships. Many people believe their cats get along, whereas in reality, they may display overt aggression (hissing or swatting) or become passively avoidant. In contrast, affiliative relationships are characterized by behaviors such as allogrooming, nose touching, or sleeping in close contact.40,41

Feline communication signs

Although cats may be distressed, they are stealthy in their ability to hide anxiety. A content cat will hold its ears forward, whiskers loose or relaxed, muscles soft, and tail loosely wrapped. Practitioners should closely observe feline body language postures for even the most subtle signs of anxiety and tension. Clinical signs of fear or stress in cats are displayed through characteristic body postures, vocalizations, and activity. A cowering (tense, flattened) position where the head is lower than the body may be indicative of stress or fear in cats. A state of distress may also be characterized by crouching, crawling, and muscular tension; activity may range from either freezing or hiding to frantic fleeing. The ears may be held flat, rotated to the side or all the way back when the cat is aroused, agitated or stressed. Dilated pupils indicate greater distress. The whiskers may be straight and directed forward. The paws may be flat on the examination surface so that the cat is ready to flee (versus the cat laying with them curled into the body in a typical relaxed pose).

Vocalizations, including hissing, yowling, growling, or screaming, may indicate defensiveness. A rapid respiratory rate not associated with disease or exertion may also be observed. The tail may flip or twitch as the cat becomes agitated; the rate and intensity of the tail movement correlates with the cat’s distress. Other activities and body language postures representing a fearful or distressed feline state include avoidance and carrying the tail low or tucked and swishing.

It is important to be aware of these signs of distress and to respect them. The cat must have a way to tell people to “please stop” or “I need a break.” When those signals are ignored or disregarded, then the cat’s fear increases and the signaling escalates.

Kittens

Genetics, in utero stresses, and poor maternal nutrition may affect physical and psychological development.37,42,43 Personality in kittens is strongly influenced by the tom and is thus genetic in nature rather than observed or learned. 44 Important aspects of kitten behavior are learned from the queen, including acceptance of foods, toileting habits, substrate preferences, and a fear response to other species (including people and dogs).35,43,45

The sensitive socialization period for new experiences, people, and other animals begins as early as 2–3 weeks and may be closing by 9–10 weeks.32,42 This period is fluid and can vary for each individual cat – what is truly important is the quality of the experience. Social interactions with littermates provide special social bonds. Ideally, kittens should have pleasant interactions with people for 30–60 minutes per day.37,46 Kittens should be gently, gradually, and positively acclimated to any stimuli (e.g., people including children, noises, animals, car transport, veterinary practice) or procedures (e.g., nail trims, grooming, medicating) they may encounter during their lifetime. This can be accomplished by pairing conditioning stimuli with food or other enticing rewards. Avoid stressful or unpleasant first encounters. Owners should introduce kittens to humans and other pets by allowing the kitten to approach and engage on their own terms.

Gentle, respectful handling will prepare the kitten for a lifetime of positive handling. The kitten that is startled or subjected to rough handling may develop fears that last a lifetime. Kittens have a high play drive and learn predatory behavior by watching, swatting, chasing, pouncing, and catching. Intercat social play peaks at around 12 weeks of age, 47 and then object play becomes more prevalent. Throughout the first year, kittens will often engage in predatory-type play. Clients should be taught not to use their hands or feet as toys during play, as cats will learn that this is an appropriate form of play and it can lead to scratching or biting injuries.

Toileting

Cats are innately fastidious. As a result, they may be naturally attracted to sand-type substrates for elimination. Elimination tends to occur away from primary resting locations, and feces and urine are often covered, presumably to avoid risk of discovery by predators. Some practitioners believe that kittens are most accepting of the litter they observe their queen using, which may influence future preferences. With this in mind, it may be beneficial to offer a young kitten a variety of toileting substrates, with a view to them evolving into an adult with greater acceptance for an array of litter types. 33 (See “Elimination” section later in the guidelines.)

Incorporating kitten socialization into the examination visit

The initial veterinary examination visit is an ideal opportunity to create a positive experience and set the stage for a lifetime of regular veterinary care. Practice team members should educate and show the cat owner how to read the cat’s body language, and identify signs of stress and fear, such as cowering, flattened ears, and hissing. They may even use tactics to encourage comfort such as slow-blink eyes. 48

Kittens should be allowed to explore and interact with practice team members. Provide toys that take advantage of the kitten’s strong prey drive, as well as palatable foods or treats. Kittens are more open to accepting foods and should be offered tidbits to divert their attention from more unpleasant aspects of the examination such as vaccination.

Currently, in North America, opportunities to attend kitten classes or structured socialization sessions are limited. Until these opportunities increase, veterinary professionals should consider each kitten’s visit as an opportunity to create a positive experience and familiarize the kitten with the practice team and environment. Team members should be trained to use appropriate interactions including positive reinforcement, gentle handling, and use of food or rewards to desensitize and countercondition kittens to veterinary or handling procedures; 8 aversive handling or punishment should always be avoided.

Training kittens in preparation to be adult cats

Kittens, and even older cats, can be taught many behaviors with well-timed positive reinforcement. For example, teaching a cat to come when called for a tasty treat can be used in carrier training, which will help build a positive association with the carrier and, in turn, assist with getting to the veterinary practice. It may be helpful for a cat owner to reward a cat for getting on a small mat so the cat will be better prepared for the veterinary examination. Interested cat owners can also teach their cats agility, fetching, or tricks. Moreover, cats can be taught to voluntarily accept grooming, nail trimming, instillation of ear treatments, application of topical anti-parasitics, and administration of medications both orally and subcutaneously. Ultimately, almost every cat is going to require medication at some time in its life, so it is prudent to acclimate cats to these types of procedures.

Kittens may be taught to accept pilling by administration of a tasty morsel of food instead of a pill. By giving treats that are soft enough that they may be wrapped around a pill, the young cat is exposed to those foods before the need for a pill. Commercially available pill pockets may be given empty or with a hard piece of kibble hidden inside to acclimate the cat to the change in texture. Kittens may even be taught to accept a novel use of the old-style “pet piller” by letting the kitten lick moist food off the end of the piller. While the kitten is eating, the piller plunger (not the piller itself) is advanced to deliver another morsel of food into the kitten’s mouth.49,50

It is imperative to educate cat owners that scratching is a normal feline behavior. Positive reinforcement for nail trimming warrants special consideration because many cats will scratch on undesirable surfaces including carpeting, window and door frames, curtains, and couches. Keeping the nails shorter can minimize the damage to household items as well as to people. Moreover, meeting the cat’s environmental needs may be beneficial in reducing scratching of unwanted surfaces. 38 Any intercat-related issues should be identified and addressed as soon as possible, as these can lead to increased territorial scratching behaviors. 51

Scratching posts and a variety of other scratching surfaces should be provided for cats as soon as they enter the home. Cats may have individual scratching habits, but consider provision of posts near resting areas and high-traffic pathways. Available scratching substrates include rope, cardboard, carpet, and wood. One study revealed that rope was most frequently used when offered, although carpet was offered more commonly. 52 Cats scratched the preferred substrate more often when the post was a simple upright type or a cat tree with two or more levels and at least 3 ft high. Narrower posts (base width less than or equal to 3 ft) were used more often than wider posts (base width greater than or equal to 5 ft). Cats between the ages of 10 and 14 years preferred carpet substrate. All other ages preferred rope. 52 The preference of older cats for carpet may be due to age-related musculo-skeletal changes or because these cats may not have had the opportunity to use the range of substrates as kittens. “Claw Counseling: Helping Clients Live Alongside Cats with Claws” 51 is one of several resources in the AAFP Claw Friendly Educational Toolkit. 53

Young adult cats

Young adult cats do not require as frequent routine medical care as kittens, so it is integral to educate the client about why regular healthcare examinations remain so important. Routine examinations can help identify behavioral changes or medical concerns that may affect a cat’s health long before they become significant, painful, or more costly to treat. Clients should be educated about the subtle changes in behavior and day-to-day life of the cat that may possibly be significant. Encouraging owners to routinely record behaviors in a journal and/or with photos and video will provide a basis for documenting any such changes. Simply asking the client, “Is your cat happy?” may help them think about their cat’s welfare.

Urine marking is most often displayed by intact male cats, although one study reported that about 10% of sterilized cats marked their territory with urine. 54 The onset of this behavior can coincide with sexual maturity. Both males and females may urine spray.

Cats may discontinue litter box use for a variety of reasons including the litter substrate offered, litter box cleaning and environmental hygiene, litter box style (e.g., covered, electronic), litter box size, location preferences, illness, or stress in the home, including conflict between housemate cats. Although individual preferences can vary, of the available litter types, most adult cats prefer clumping litter, and most cats prefer plain unscented litters. 55 Some cats may find scented litters significantly aversive. 56 Cats have shown a tendency to prefer larger litter boxes.57,58

Intercat relations

The reduction in social play combined with the dispersal effect (when free-living offspring leave the family unit at about 1–2 years of age) means that intercat aggression may develop at this stage of life. Conflict may occur when a new cat is introduced. Alternatively, a housemate cat may become the target of aggression following a stressful event (e.g., returning home from a veterinary visit) or owing to redirected aggression triggered by a cat outside the home.

Controversy exists over whether cats should be kept indoors only or in an indoor/outdoor environment (see the “Lifestyle choices” box). These debates reflect geographical and cultural differences as well as individual owner preferences.60-65 The focus should be on providing an appropriate, stimulating, and safe environment for the cat. 38 All cats should be microchipped for permanent identification.

Play

Declining play activity increases susceptibility to weight gain. In one study, three 10- to 15-minute exercise sessions per day led to a loss of approximately 1% of body weight in 1 month with no food intake restrictions. 66

Senior cats

Senior cats exhibiting new or unusual behavior should be evaluated for medical conditions. 12 Changes in litter box usage may indicate urinary tract disease, constipation, or diabetes but may also be due to reduced musculoskeletal strength, impaired balance, or onset of pain. Vocalization, especially nighttime waking, is a common concern and may represent sensory changes (declining hearing and vision), cognitive dysfunction syndrome, pain, hyperthyroidism, or hypertension. Veterinary visits may be more challenging for the senior cat, in part because many cat owners do not seek wellness visits, but present their cats only for acute care. 3 The use of pheromones or pre-veterinary visit pharmaceuticals such as gabapentin or trazodone may reduce stress while allowing thorough evaluations.68-71 As many senior patients may be experiencing some level of pain related to their disease or secondarily to DJD, analgesics may also be indicated for veterinary visits.

DJD and/or muscle weakness may initially manifest as a change or reduction in jumping or climbing in senior cats. Because of the challenges of diagnosing feline arthritis, it can be difficult to tell how many cats are affected. Estimates from published studies suggest that 40–92% of all cats may present with clinical signs associated with DJD. 72 These studies show that arthritis, in addition to being very common in cats, is much more prevalent and severe in older cats, and that the shoulders, hips, elbows, knees (stifles), and ankles (tarsi) are the most frequently affected joints. DJD is the inclusive terminology that includes the two most common changes in aging cats – osteoarthritis and spondylosis deformans of the intervertebral disc. Owners may report changes in behavior such as “not getting on the counters as much” or “doesn’t like his window seat anymore.”

Although it is important to ask about jumping and climbing, it is critical to listen carefully to descriptions of changes in behavior, even seemingly positive changes. Senior cats may have reduced muscle mass or orthopedic conditions such that they would benefit from comfortable and warm resting locations. It is also beneficial to increase resource availability to reduce the distance seniors might have to move in order to reach food, water, or a litter box. Conflict with housemate cats may occur at any age but may be especially problematic for the senior cat (e.g., may have little patience for a kitten).

Elimination

House-soiling is a common reason for cat owners to seek veterinary advice, 33 yet according to a 2016 study, only 31.7% of cats with house-soiling behavior were evaluated by a veterinarian for this condition. 73

Asking specific questions regarding elimination habits and inquiring whether any house-soiling has occurred since the last examination is an important discussion item for each visit. Clients may assume these behaviors are normal or cannot be corrected. Timely intervention is critical to address these behaviors effectively.

General litter box considerations

Litter boxes should be provided in different locations that are easily accessible throughout the house to the extent possible, particularly in multicat households. The rule of thumb is one litter box for each cat plus one additional box, or one litter box for each social group plus one additional box, if the number of social groups is known. Placing litter boxes in multiple quiet locations that are convenient for the cat, and provide an escape route if necessary, could help facilitate conditions for normal elimination behaviors.

If different litters are offered, it may be preferable to test the cat’s preferences by providing choices in separate boxes, because individual preferences for litter type have been documented.33,58 For cats with a history of urinary problems, unscented clumping litter may be preferred.55,60 Litter boxes should be cleaned regularly and replaced, as well as scooped daily. Soap or strong chemicals should be avoided; hot water is best. Some cats seem quite sensitive to dirty litter boxes. 74 Litter box size and whether the box is open or covered may also be important to some cats.75,76 It is recommended that the litter box be at least one and a half times in size based on the length of the cat from nose to tip of the tail, which means most manufactured boxes are not large enough. Using items such as larger storage containers is likely to achieve proper litter box size.

The litter box edges should not be too high in order for a kitten or senior cat to enter and exit easily. For kittens, discuss appropriate litter box management and locations with the client to assure proper use by the cat. Litter box rejection can stem from a variety of causes, and choices can be offered for the kitten to express their preference. If house-soiling is noted by the owner, the kitten should be evaluated for underlying conditions such as congenital abnormalities of the lower urinary or GI tract, GI parasites, or other infectious diseases. Mature adult and senior cats may house-soil secondarily to medical or behavioral conditions. Clients should be encouraged to seek veterinary assistance promptly, in order to diagnose life-threatening conditions such as urinary tract blockage, and to avoid having the behavior become entrenched.

Cats should never be reprimanded for toileting in undesired locations and should never be taken to a litter box punitively.

Urine marking

If cats at any life stage present with lower urinary tract signs, the practitioner must obtain a definitive history to differentiate various underlying causes for the signs. Urine marking, which is recognized as a normal felid behavior, 77 is certainly not desirable for solely indoor-housed cats. Most cats that mark have a characteristic posture, whereby their tail is lifted and voiding often occurs on vertical surfaces. However, cats can mark on horizontal surfaces, especially on owners’ personal items. A detailed physical examination and environmental history, including a description of the behaviors, should be obtained for these cases. For some questions to consider, see the “Investigating urine marking” box.

Urine marking, although often associated with intact male cats, can be displayed by both feline sexes, intact or neutered. Neutering is nonetheless advisable, supported by a study showing that urine-spraying behavior in a small group of 17 free-roaming domestic cats almost disappeared when the cats were evaluated after neutering. 78 Unfortunately, neutering will not eliminate or prevent spraying in all cats. Because environmental stressors can trigger urine-marking behavior, assuring that the environmental needs of the cat are met is critical. 38

Lower urinary tract disease

If young adult or mature cats are presented with lower urinary tract signs, such as pollakiuria, hematuria, or periuria, feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC) is the most likely differential. 79 Although this is currently a diagnosis of exclusion, this disease can be exacerbated by a variety of stressors perceived by the cat. Notably, there is evidence that complex interactions exist between “susceptible” cats and “provocative” environments in the development of chronic lower urinary tract signs. 60 A study evaluating multimodal environmental modification suggested that this form of therapy can be beneficial for helping manage cats with FIC. 80 Affected cats were followed for 10 months, primarily by phone contact, and significant (P <0.05) reductions in lower urinary tract signs were noted.

Although urine-marking behavior and FIC are different conditions, the environmental management of both of these elimination problems is similar. Tailoring an environment that is optimal for the indoor cat to reduce urine marking could also help prevent the onset or reduce the severity of FIC. 81 Not all cats will require intense multimodal environmental modification therapy, giving practitioners scope to adapt environmental change recommendations based on the cat’s needs and owner’s desire and commitment to this process.

Senior cats

For all cats, but especially senior cats, that present with elimination issues, a thorough diagnostic evaluation is recommended. Disorders that result in polyuria or polydipsia such as diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and hyperthyroidism can lead to elimination behaviors. If the cat is defecating outside the litter box, a fecal score should be obtained and recorded to help follow potential trends and guide diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.25,26 Veterinarians should discuss other potential problems such as DJD that can lead to elimination problems in senior cats. Litter boxes should be easily accessible. Cats with mobility issues may need a lower litter box height, with the box placed close to their core areas. Avoiding the need to climb stairs can be beneficial.

Life stage nutrition and weight management

All life stages

In the wild, cats are exclusively solitary hunters and often will predate animals of much smaller body mass than their own. This requires them to hunt and feed several times during the day. 82 Because of evolutionary changes, the domestic cat has lost key metabolic enzymes, and this has resulted in very narrowly defined nutritional requirements. 83 All cats require protein, which is composed of 23 different amino acids; 11 are considered essential for the cat. Deficiencies in any essential nutrients could result in health problems. 83 No matter the life stage, to help avoid potential nutrient insufficiencies, cats should be fed diets labeled with an Association of American Feed Control Officials statement of nutritional adequacy. AAHA and the AAFP do not advocate or endorse feeding cats any raw or dehydrated non-sterilized foods, including treats that are of animal origin. 84

In order to make a nutritional recommendation, the practice team can assess nutritional status based on age, reproductive status, BCS, MCS, activity level, presence of disease, and future health concerns for the individual cat. 85 A diet is selected to best meet the nutritional needs of the patient, and a specific feeding plan is then developed. Clinical discretion is applied to allow gradual transitioning to the new diet over 7–l0 days. 85

Kittens

Kittens can be weaned onto commercially balanced kitten foods starting at 3–5 weeks of age. Growing kittens at 10 weeks of age have a very high energy requirement of 200 kcal/kg body weight/day compared with 80 kcal/kg/ day at 10 months of age. Generally, kitten food preferences have been reported to be highly influenced by the queen (i.e., the primary effect), 86 although these preferences can be modified in the adult cat based on experiences. 83 Behavioral and ethological research both suggest that cats prefer to eat individually in a quiet location where they will not be startled by other animals, sudden movement, or activity.87,88 Natural feline feeding behavior also includes predatory activities such as stalking and pouncing. These may be simulated by hiding small amounts of food around the house, or by using a food puzzle from which the cat has to extract the food (if such interventions appeal to the cat). 19 Implementing these options during the kitten life stage is recommended and also provides opportunity to enrich the environment.

Obesity prevention starts with kittens. As neutering is associated with weight gain, 89 this is an excellent time to evaluate the nutritional needs, obesity risks, and prevention strategies for the individual patient. Recommendations can be found in the AAFP’s “Feline Feeding Programs Consensus Statement”. 19

Young adult cats

Energy requirements of cats are influenced by a variety of factors including age (i.e., life stage), BCS, MCS, neuter status, health status, and activity level. Using indirect calorimetry, young adult active cats have been shown to have higher energy requirements compared with senior cats. 90

The amount fed should be adjusted to maintain or encourage ideal body condition, and a BCS should be documented by the veterinarian at each visit. 91 Photographs (dorsal and lateral) of the cat can be obtained and recorded. A BCS of 6/9 or 7/9 is considered overweight, and a score of greater than or equal to 8/9 is considered obese. 92 The prevalence of obesity in cats ranges from 1.8 to 40% in published studies. 60 Being overweight or obese can predispose to a variety of chronic health conditions including diabetes mellitus,93,94 lameness (presumably related to osteoarthritis and soft tissue injury),93,94 non-allergic skin disease,93,94 urethral obstruction, 95 and, according to one study, an increase in the prevalence of oral disease. 93

Neutering is a risk factor for obesity in cats, especially males, 96 and dietary energy restriction may be appropriate to prevent weight gain. 97 Free-choice feeding is a common strategy used by cat owners and can predispose to overconsumption. Maintenance of a healthy body weight requires monitoring and control of caloric intake. A good starting point is to calculate the adult feline patient’s resting energy requirements (RER) according to the following calculation: RER (kcal per day) = 30 x (body weight in kg) + 70. Daily energy requirements (DER) are determined based on multiplying by a needs factor, which in the case of young, healthy adults is 1. Food intake can be determined by comparing DER with the caloric density of the patient’s foods.85,98-100

Prescription diets are indicated for obesity treatment. These weight loss diets are formulated to provide adequate vitamins and minerals with reduced caloric content. It is important to inform owners of overweight cats that simply feeding less of a maintenance diet in order to reduce caloric intake may result in vitamin and mineral deficiencies.

Mature adult and senior cats

Mature adult and senior cats have changing dietary needs, and it is extremely important to provide guidance on daily feeding amounts. DER for mature adult cats (aged 7–10 years) may be equivalent to RER, although adjustments should be made based on the needs of the individual patient. For senior cats (greater than 10 years of age), the RER will need to be multiplied by a factor of 10–20%, and in some cases as high as 25%. 101 Senior cats may also experience a reduction in digestive capabilities, leading to decreased BCS and thus increased caloric intake. 92 Being underweight is a common problem in senior cats.102-104

Prescription therapeutic diets may be indicated more often for cats in the mature adult or senior life stage for a variety of reasons (e.g., chronic kidney disease, obesity, hyperthy-roidism, chronic enteropathies, osteoarthritis). If a dietary change is indicated, offering the new diet in a separate, adjacent container (rather than removing the usual food and replacing it with the new food) will permit the cat to express its preference. Dietary changes should be implemented in the home setting rather than in the practice in order to avoid stress-related food aversions. However, introduction of novel diets to inappetent, hospitalized cats should not be avoided if food consumption is a concern.

There is a lack of consensus regarding optimal dietary protein levels in mature adult cats. A published study demonstrated that aging cats should in fact receive diets higher in protein to avoid loss of lean muscle mass. 105 Healthy mature adult/senior cats should not be protein restricted; a diet with a minimum protein allowance of 30–45% dry matter is considered to be moderate protein and is recommended. However, cats with chronic kidney disease may benefit from prescription renal diets, which have restricted, high-quality protein and restricted phosphorus levels, as well as other ingredients that may promote renal health. Ongoing research is examining the role of antioxidants in the progression of renal disease; one study demonstrated the benefits of feeding a diet with highly bioavailable protein supplemented with fish oil, L-carnitine, antioxidants, and amino acids to senior cats in early renal failure. 106 Further studies are needed to develop definitive recommendations.

Oral health

Lifelong proactive dental care will improve a cat’s health and well-being and should begin with the initial kitten visits. If the practice team starts to discuss the importance of oral health at kitten wellness appointments, the owner will come to think of the cat’s dental health as being a significant contributor to its quality of life. 107 After the practitioner has determined that no malocclusion or dental eruption problems are present, 108 practice team members can instruct owners on how to examine the cat’s mouth and how to brush the teeth. Providing videos, written and verbal instructions, and samples of products that have Veterinary Oral Health Council approval will also encourage the owner to begin providing oral care.109,110 If these training sessions include a treat reward or palatable toothpaste, the kitten will learn that handling of its mouth normally is not aversive.110,111

If adult cats will not allow routine tooth-brushing, a dental diet may be beneficial.107,111-113 If both the owner and practitioner routinely examine the cat’s mouth as it matures, a diagnosis of dental disease, masses, or orofacial pain can be made before problems escalate and cause pain and hyporexia.107,113,114

The use of photographic or radiographic images of sequential oral examinations, as well as scoring sheets for dental pathology, generally better communicates the degree and progression of pathology. Improved client education can encourage cat owners to comply with veterinary recommendations regarding dental care. Periodic complete dental prophylaxis, including full oral dental radiography, even if gross pathology is not present, can be beneficial. 107 The use of feline-friendly handling techniques and anxiolytics will allow a more thorough oral examination. Only after the patient has been anesthetized can a complete and thorough oral evaluation be successfully performed. The comprehensive examination includes a tooth-by-tooth visual assessment, probing, mobility assessment, radiographic examination, and oral examination charting.115,116 Anesthesia-free dentistry is not appropriate because of patient stress, injury, risk of aspiration, and lack of diagnostic capabilities. Furthermore, because this procedure is intended only to clean the visible surface of the teeth, it provides the pet owner with a false sense of benefit to their pet’s oral health.117-119

Parasite control

For kittens and newly adopted cats with an unknown history of medical care, it is prudent to administer prophylactic treatment for parasites with broad-spectrum products efficacious against heartworms, intestinal parasites, and fleas.17,120,121 This approach will eliminate existing infections, as well as decrease the risk of further infestation and subsequent associated clinical problems. Canine and feline housemates may be at risk of transmission of infectious parasites including roundworm and fleas and therefore should be treated in synchronicity with newly acquired kittens or cats. Preventing cats’ access to gardens and children’s play sand areas will, combined with parasite prophylaxis, decrease environmental contamination with infectious and zoonotic agents such as hookworms and Toxoplasma gondii. 33

Routine, regular use of broad-spectrum products is likely to be beneficial for the majority of pet cats, regardless of lifestyle. Certain outdoor lifestyles, geographic location, and whether a cat spends time away from the home (travel, boarding facilities, groomer, etc.) may increase the existing risk of parasitic infection. Thus, recommendations for prevention and control should reflect knowledge of the risks and benefits for the individual cat. Fecal examinations, when appropriate, may diagnose specific infections and guide therapy; however, negative testing does not rule out infection. Ectoparasite prevention will lower the risk of cutaneous and systemic diseases. 120 As tick populations increase in number and expand geographically, the prevention of tick infestations in cats is becoming increasingly important. Ticks may act as vectors of feline diseases such as rickettsial infection and hemotropic mycoplasmosis, and cats may act as transport hosts of infected ticks to humans.122,123 There has been an upward trend in heartworm incidence reported by veterinarians over the past 3 years in the United States. 124 Prevention of heartworm infection, and subsequent feline HARD or heartworm disease, is preferable, as diagnosis is challenging at best and treatment difficult because of the inherent risks associated with therapy. 125

Vaccination

Practitioners can develop individualized vaccination protocols consisting of core vaccines (rabies virus, feline herpesvirus type 1 [FHV-1], feline calicivirus [FCV], and feline panleukopenia virus [FPV]) and non-core vaccines based on exposure and susceptibility risk as defined by the patient’s life stage, lifestyle, and place of origin as well as by environmental and epidemiologic factors.

The Task Force supports the “2020 AAHA/AAFP Feline Vaccination Guidelines” 7 and the World Small Animal Veterinary Association’s recommendation that veterinarians should vaccinate every animal with core vaccines and give non-core vaccines no more frequently than is deemed necessary based on risk exposure. 126 Revaccination against FPV, FHV-1, and FCV at 6 months of age to potentially reduce the window of susceptibility in kittens with maternally derived antibodies toward the end of the kitten series (16–18 weeks) is recommended. 7 Feline leukemia virus (FeLV) vaccination is considered core for kittens and young cats owing to age-related susceptibility, especially those with a high risk of regular exposure. It is recommended to revaccinate for FeLV 12 months after the last dose in the kitten series, and then annually for individual cats at high risk. Veterinarians have considerable ability to use biologics in a discretionary manner but also should be aware of any state- or provincial-specific restrictions in their veterinary practice act relating to implementation, especially in regard to rabies. Detailed information regarding the role of vaccination as an essential component of preventive healthcare is given in the “2020 AAHA/AAFP Feline Vaccination Guidelines”. 7

Feline injection-site sarcoma is a real, albeit low, risk for cats receiving injectable vaccines. 7 Feline injection-site sarcomas are aggressive, locally invasive neoplasms that are difficult to diagnose and surgically remove. 7 Practitioners should follow the “3-2-1 rule” when investigating suspicious masses.7,127 In order to facilitate surgical excision or amputation in the event of sarcoma formation, and the opportunity to obtain two or three surgical planes, all vaccines should be administered in the lower limbs or tail, as recommended in the “2020 AAHA/AAFP Feline Vaccination Guidelines”. 7 Distal limb injections should be administered below the elbow or stifle; tail injections should be in the distal third of the tail. Because complete surgical excision of a mass is most difficult in the intrascapular space, administration at this location is not recommended. Education of owners regarding injection-site reactions is prudent. Practitioners are strongly advised to keep complete, accurate records of antigen administration site and route of vaccine administration.

Zoonoses and human safety

Healthy humans are at very low risk of infection with a zoonotic agent through exposure to a healthy cat. 17 However, immunocompro-mised individuals (e.g., older adults, children younger than 5 years of age, pregnant women, or immunosuppressed individuals) are at increased risk of acquiring zoonotic disease from pets. Common zoonotic diseases in cats (e.g., toxocariasis, toxoplasmosis, ringworm, bartonellosis [cat scratch fever]) are described in detail in the “2019 AAFP Feline Zoonoses Guidelines”, 17 as well as within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s “healthy pets, healthy people” resource. 128 This information can aid in education of the practice team and help guide discussions with pet owners.

Basic preventive healthcare (e.g., internal and external parasite control, vaccination) protects both feline and human health and is further enhanced by management to prevent pet roaming. Understanding and instituting proper biosecurity measures is a basic tenet of preventing zoonoses. Detailed guidance for assessing and instituting biosecurity protocols can be found in the “2018 AAHA Infection Control, Prevention, and Biosecurity Guidelines”. 129 The practice team should ensure proper hand hygiene and personal protection at all times and alert coworkers to likely infectious animals so that possible exposure can be mitigated.

Pet food, particularly raw or undercooked meat, is also a source of potential zoonotic agents. 130 Many veterinary and human health organizations, including AAHA and the AAFP, do not advocate or endorse feeding pets any raw or dehydrated non-sterilized foods, including treats that are of animal ori-gin. 84 Safe food handling should be practiced with all pets.

Avoiding situations that may lead to cat bites or scratches is a key part of human safety and, in turn, a means to help prevent zoonoses associated with these injuries. This is another important reason for the practice team to learn and engage in feline-friendly handling techniques 8 and to teach owners techniques to help them avoid being bitten or scratched by their pet. The risk of cat scratch fever, a zoonotic disease caused by Bartonella henselae transmitted by fleas, can also be reduced by the use of regular, effective flea prevention. 17

‘Diagnostics should be tailored to the individual cat and based on history/physical examination. These recommendations are based on the opinion of the Task Force for apparently healthy cats and do not include recommendations for preanesthetic laboratory work. In most cases, these tests are recommended to establish baseline data and to detect unapparent clinical disease

“These tests may be done as a single baseline evaluation or at repeated intervals based on the specific needs of the individual cat + = consider based on individual patient; ++ = recommended; +++ = strongly recommended

Recommended diagnostics based on life stage

Recommended diagnostics according to life stage are outlined in Table 4. These recommendations are intended for apparently healthy cats and do not extend to preanesthet-ic laboratory work. Although specific data documenting benefits are not available, the Task Force concluded that regular preventive healthcare examination and collection of associated medical data can be valuable, allowing early detection of disease or trends in clinical or laboratory parameters that may be of concern. Examples include increasing creatinine, symmetric dimethylarginine, total thyroxine (T4), or blood pressure and decreasing urine specific gravity. Additionally, these diagnostic results provide a baseline for interpretation of data recorded at subsequent visits.

Table 4.

Recommended diagnostics based on life stage*

| Kitten (birth up to 1 year) | Young adult (1-6 years) | Mature adult (7-10 years) | Senior (>10 years) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete blood count: hematocrit, red blood cells, white blood cells, differential count, cytology, platelets |

+ | ++ | +++ | |

| Serum biochemistry panel: at a minimum include total protein, albumin, globulin, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, glucose, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, potassium, phosphorus, sodium, calcium |

+ | ++ | +++ | |

| Urinalysis: specific gravity, sediment, glucose, ketones, bilirubin, protein |

+ | ++ | +++ | |

| T4 | + | ++ | +++ | |

| Symmetric dimethylarginine and other renal indices | + | ++ | +++ | |

| Blood pressure | + | ++ | +++ | |

| Retroviral testing | + | + | + | |

| Fecal examination | +++ | + | + | + |

| Testing frequency* | Single baseline, then as needed | Single baseline, then as needed | Every 1-2 years | At least yearly (every 6 months recommended) |

Detailed information on heartworm testing is available in the American Heartworm Society guidelines 125

Specific recommendations regarding frequency of laboratory testing by life stage depend on many factors. One consideration regarding testing frequency is that the incidence of many diseases increases as cats age. Although limited incidence studies have been performed to identify the age of onset of hyperthyroidism in cats, the Task Force recommends that veterinarians strongly consider T4 testing in the apparently healthy mature adult cat. More robust incidence data are needed to develop firmer recommendations.

Comorbidities are extremely common in the senior cat and can impact diagnostic, treatment, and management approaches. Additional considerations relating to diagnosis and management of diseases in mature adult and senior cats are described in the “AAFP Senior Care Guidelines”. 12 Consensus guidelines and toolkits for the diagnosis and treatment of specific medical conditions are available for more detailed information (see “Guidelines and toolkits” box).

For cats of all ages, timing and frequency of diagnostics may depend on lifestyle, exposure risks, and geographic location. Retroviral testing recommendations are discussed in detail in the “2020 AAFP Feline Retrovirus Testing and Management Guidelines”. 18 In addition to routine deworming, fecal examination should be performed regularly at intervals based on patient health and lifestyle factors.

Heartworm infection is more difficult to diagnose in cats than in dogs because of lower worm burden, single-sex infections, and infrequency of microfilaremia. HARD, which is an asthma-like inflammatory reaction of the pulmonary tissue to immature larval stages, is an added complexity relating to heartworm exposure in cats. Interpretation of antibody and antigen test results is challenging, and a thorough understanding of the limitations of both tests is necessary. More detailed information is available in the American Heartworm Society guidelines. 125 Testing does not need to be performed before starting preventive treatment.

N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide has been investigated as a diagnostic tool for cardiac disease in cats. 138 However, limited information exists about using this test as a screening tool and recommendations cannot be made on the frequency of use for the general population. The decision to use this test should be on an individual basis, and interpretation of test results should be made with an understanding of the sensitivity and specificity of the assay.

Practice team training and client education

Team training and education of clients are integral to implementing successful life stage recommendations. These two factors will allow the practice team to appropriately accomplish physical examination and diagnostics, and institute treatment protocols when indicated for the patient. Feline-specific training for the practice team should be delivered on a regular basis, incorporating continuing education as well as staff meetings and team-building events held at the practice.

Team training will ensure all staff members are knowledgeable and are following practice protocols for life stage recommendations. From the front office staff and veterinary technicians to the veterinarians, everyone will know what is expected of them and how to respond appropriately in the light of the feline patient’s life stage. Team training events to increase knowledge and confidence when taking patient histories (see “Conducting effective patient histories” box) and providing client education are just as important as further education on feline-friendly handling, disease processes, and technical skills.

Ideally, client education is a key responsibility for all staff members. Every life stage will have specific items that should be discussed in the veterinary visit (see Table 2), and both veterinary technicians and veterinarians should be familiar with current recommendations and practice protocols in order to educate clients on the most critical health-related factors relevant to each life stage. The practice team can better connect with clients when they understand that pet owners can become overwhelmed at veterinary visits. Moreover, communicating that the cat owner is an integral part of the healthcare team can reinforce the veterinary–client–patient relationship, as well as improve compliance.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jfm-10.1177_1098612X21993657 for 2021 AAHA/AAFP Feline Life Stage Guidelines by Jessica Quimby, Shannon Gowland, Hazel C Carney, Theresa DePorter, Paula Plummer and Jodi Westropp in Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-jfm-10.1177_1098612X21993657 for 2021 AAHA/AAFP Feline Life Stage Guidelines by Jessica Quimby, Shannon Gowland, Hazel C Carney, Theresa DePorter, Paula Plummer and Jodi Westropp in Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-3-jfm-10.1177_1098612X21993657 for 2021 AAHA/AAFP Feline Life Stage Guidelines by Jessica Quimby, Shannon Gowland, Hazel C Carney, Theresa DePorter, Paula Plummer and Jodi Westropp in Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery

Acknowledgments

The Task Force gratefully acknowledges the contribution of Mark Dana of Scientific Communications Services, LLC, and the Kanara Consulting Group, LLC, in the preparation of the guidelines manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BCS (body condition score); DER (daily energy requirements); DJD (degenerative joint disease); FCV (feline calicivirus); FeLV (feline leukemia virus); FHV-1 (feline herpesvirus type 1); FIC (feline idiopathic cystitis); FPV (feline panleukopenia virus); GI (gastrointestinal); HARD (heartworm-associated respiratory disease); MCS (muscle condition score); RER (resting energy requirements); T4 (thyroxine)

Hazel C Carney has received speaking fees from Royal Canin. Jessica Quimby is a consultant/key opinion leader for Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA Inc., Dechra Veterinary Products, Elanco Animal Health, Hill’s Pet Nutrition, Inc., IDEXX Laboratories, Inc., Kindred Biosciences, Inc., Nestle Purina Petcare, and Royal Canin. Jodi Westropp has received speaking fees from Bayer Animal Health, Nestle Purina Petcare, Hill’s Pet Nutrition, Inc., and Royal Canin; served as a consultant/ key opinion leader for Nestle Purina Petcare; and served on the academic board for the International School of Veterinary Postgraduate Studies. The other members of the Task Force have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA Inc., CareCredit, Dechra Veterinary Products, Hill’s Pet Nutrition, Inc., IDEXX Laboratories, Inc., Merck Animal Health, and Zoetis Petcare supported the development of the “2021 AAHA/AAFP Feline Life Stage Guidelines” and resources through an educational grant to AAHA.

Ethical approval: This work did not involve the use of animals and, therefore, ethical approval was not specifically required for publication.