Abstract

The development of potent, specific, and pharmacologically viable chemical probes and therapeutics is a central focus of chemical biology and therapeutic development. However, a significant portion of predicted disease-causal proteins have proven resistant to targeting by traditional small molecule and biologic modalities. Many of these so-called “undruggable” targets feature extended, dynamic protein–protein and protein–nucleic acid interfaces that are central to their roles in normal and diseased signaling pathways. Here, we discuss the development of synthetically stabilized peptide and protein mimetics as an everexpanding and powerful region of chemical space to tackle undruggable targets. These molecules aim to combine the synthetic tunability and pharmacologic properties typically associated with small molecules with the binding footprints, affinities and specificities of biologics. In this review, we discuss the historical and emerging platforms and approaches to design, screen, select and optimize synthetic “designer” peptidomimetics and synthetic biologics. We examine the inspiration and design of different classes of designer peptidomimetics: (i) macrocyclic peptides, (ii) side chain stabilized peptides, (iii) non-natural peptidomimetics, and (iv) synthetic proteomimetics, and notable examples of their application to challenging biomolecules. Finally, we summarize key learnings and remaining challenges for these molecules to become useful chemical probes and therapeutics for historically undruggable targets.

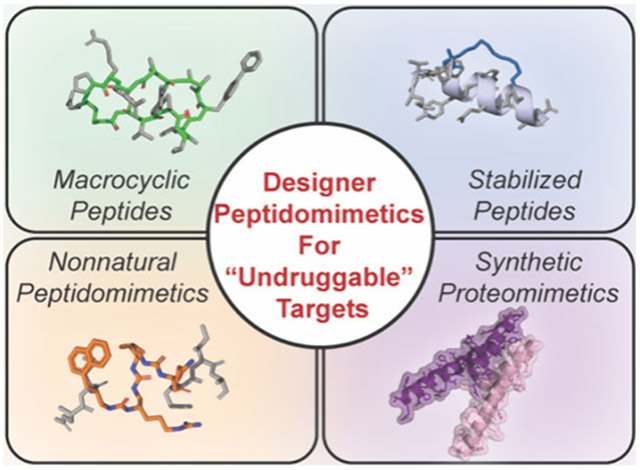

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION: DESIGNING AND DEPLOYING DESIGNER PEPTIDES, PEPTIDOMIMETICS, AND PROTEOMIMETICS FOR “UNDRUGGABLE” TARGETS

Over the past few decades, rapid development in the fields of molecular biology and chemistry have ushered in an era of tremendous progress for drug discovery. Modern techniques for protein and nucleic acid purification along with data-drivenomics approaches have identified an ever-expanding list of disease-causal targets—typically proteins—that may serve as starting points for the development of chemical probes and therapeutics. Specific protein classes have proven to be intrinsically druggable by current modalities, including specific receptor families like ion channels and GPCRs, as well as intracellular enzymes and nuclear hormone receptor transcription factors (NHR-TFs).1,2 These protein targets are typically characterized by the presence of defined ligand binding sites and other hydrophobic pockets amenable to small molecule discovery and medicinal chemistry optimization.3 Other disease-associated protein targets are present on the surface of cells or are secreted into the extracellular space, thus enabling targeting by large, hydrophilic biologic modalities, including monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), recombinant proteins, and engineered peptides (Figure 1A). A significant number of disease-associated targets fall between these two druggable landscapes, with neither obvious ligand binding sites nor extracellular exposure lending themselves toward cell permeable small molecules or traditional biologics, respectively. This landscape of targets therefore has been referred to by many as being “undruggable” (Figure 1A).4,5 Additional characteristic features shared by many undruggable targets generally include the lack of enzymatic activity and reliance upon large, dynamic surfaces and disordered structures that mediate protein–protein interactions (PPIs) and/or protein–nucleic acid interactions integral to their function (Figure 1A). While all protein families contain disease-associated targets that could be considered undruggable, several families have emerged as particularly challenging, including small GTPases, phosphatases, transcription factors (TFs), epigenetic enzymes, and chromatin regulatory factors.3

Figure 1.

Designer peptides and peptidomimetics for undruggable targets. A) The vast majority of putative disease drivers lack structural features conventionally targeted by small molecules or antibodies. B) Molecular dynamics simulations (50 ns) of unmodified and Diels–Alder cyclized loop designer peptide, demonstrating significant stabilization of structural topology. C) Classes and respective characteristics of designer peptides and proteomimetics, discussed in this review.

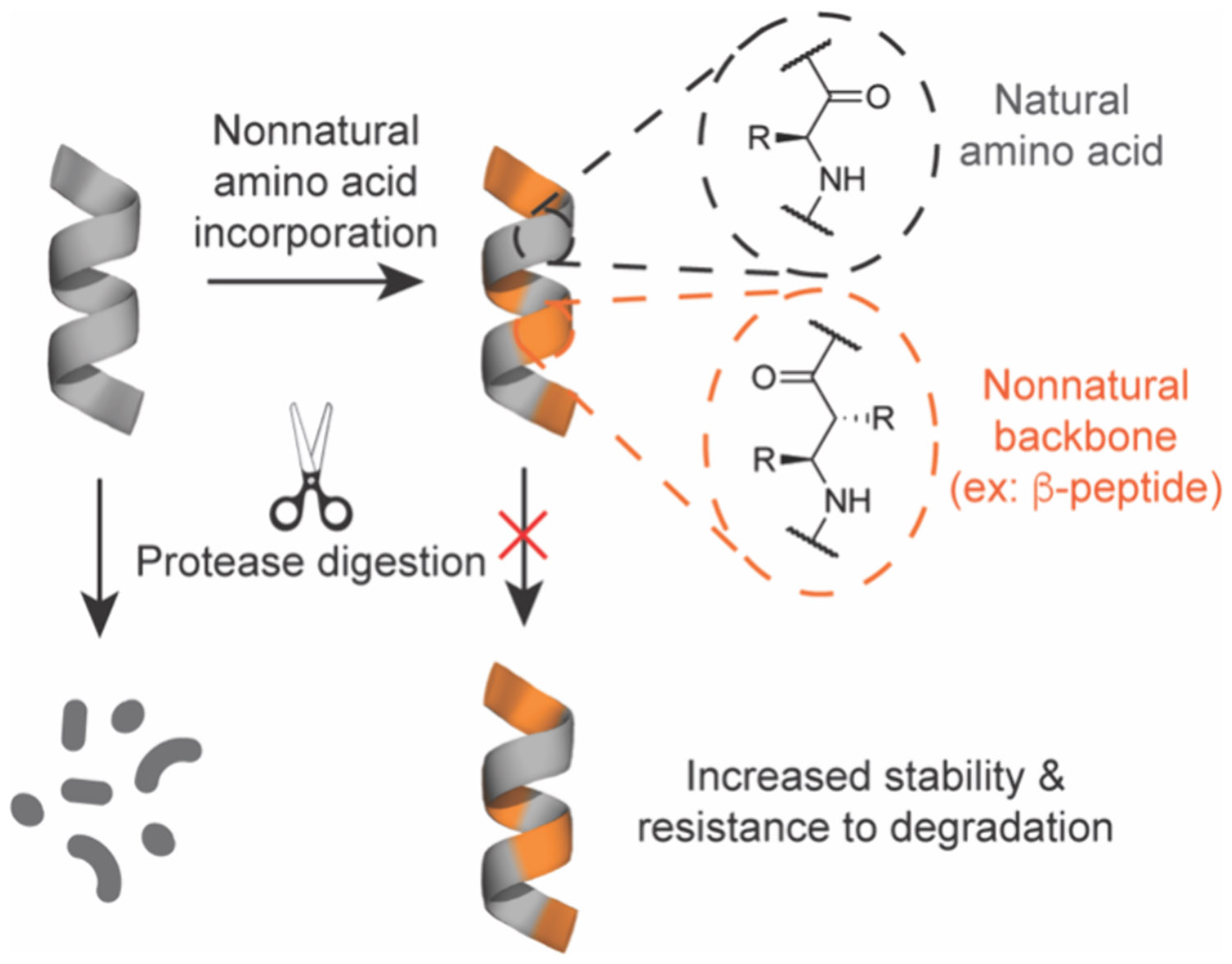

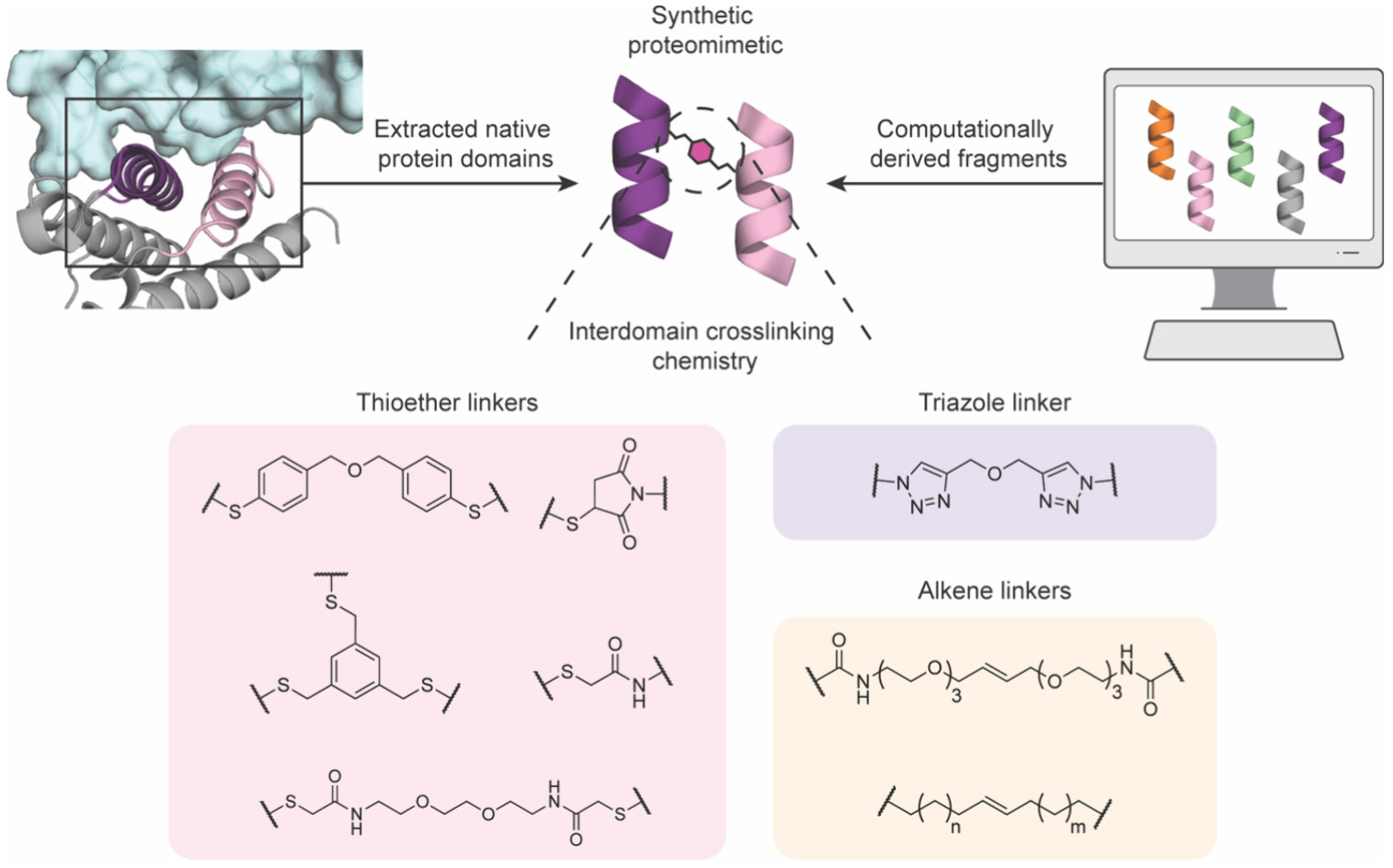

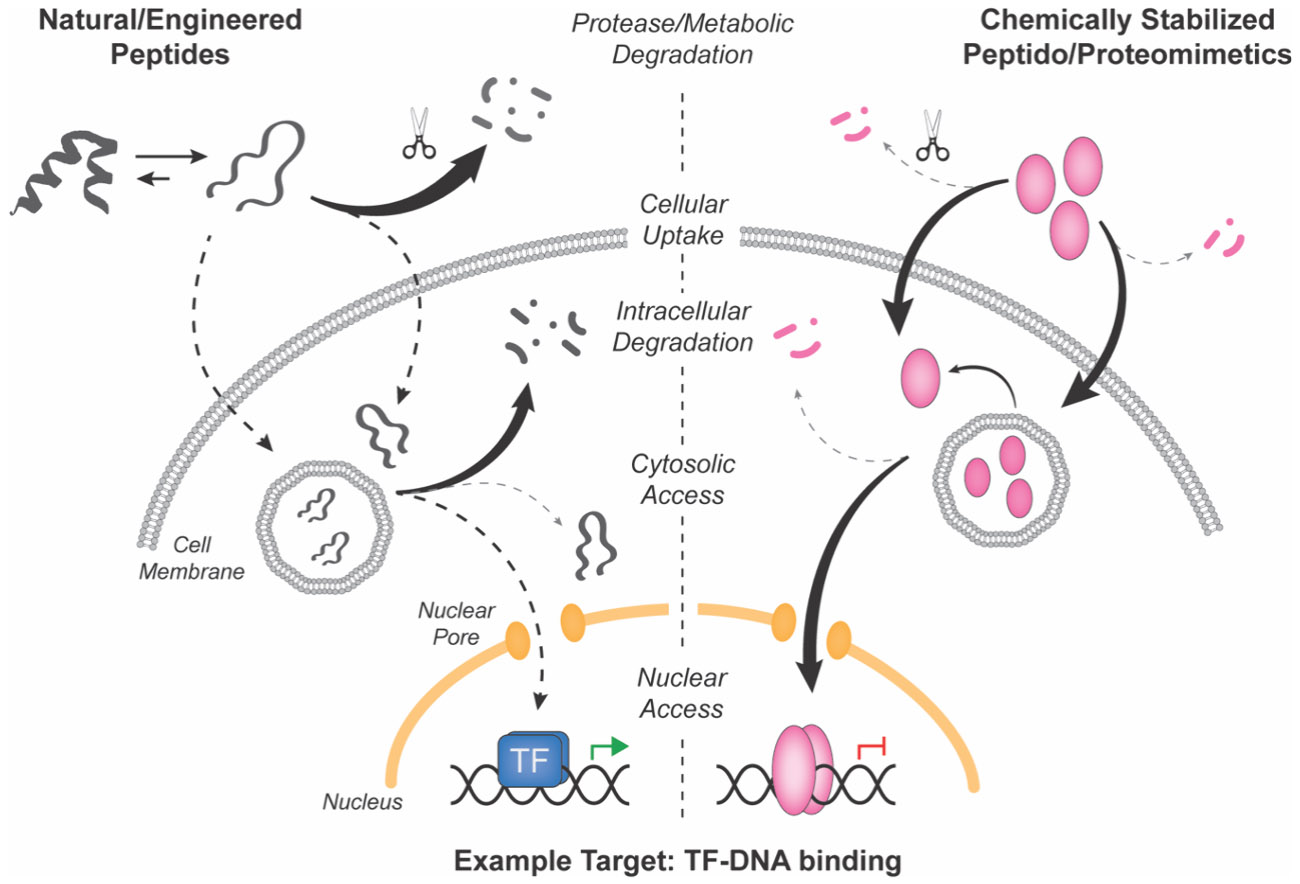

Molecules that blend some of the physicochemical properties of synthetic small molecules with the higher energy and specificity of protein therapeutics could serve as attractive starting points for undruggable targets. Peptides naturally embody this molecular middle ground, owing to their larger binding footprint and propensity for specific interactions at PPI and protein–nucleic acid interfaces in myriad natural biological processes. Indeed, dozens of natural and engineered peptides are currently in the clinic for diverse disease indications.6,7 Relative to biologics, natural peptides are significantly smaller in size, which can confer increased stability, synthetic tractability, reduced manufacturing costs, and higher likelihood of developing peptide analogs with reasonable cell and tissue penetration for intracellular target engagement.8 However, as a class natural peptide sequences composed of linear α-amino acids generally exhibit poor cell membrane permeability, high in vivo clearance rates from blood, and susceptibility to proteolytic and other metabolic degradation outside and inside cells (Figure 1B).9-14 Therefore, considerable research effort has been focused upon chemical strategies to improve the physicochemical properties of peptides to overcome these limitations. A hallmark approach is to use synthetic modifications to stabilize local and global structural motifs, which can theoretically provide enhanced affinity and specificity for intended molecular targets, as well as vastly improved pharmacological properties (Figure 1B). These chemically stabilized molecules, generally termed peptidomimetics,15 have a rich history in drug discovery as ligands for various receptors or enzymes as described in several reviews.16-21 In this review, we consider these synthetically modified compounds “designer” peptides or peptidomimetics, as well as larger mimetics of protein domains, which encompass proteomimetics or “synthetic biologics.” In this review, we will specifically focus on the development for and application of these molecules to tackle undruggable targets (Figure 1C).

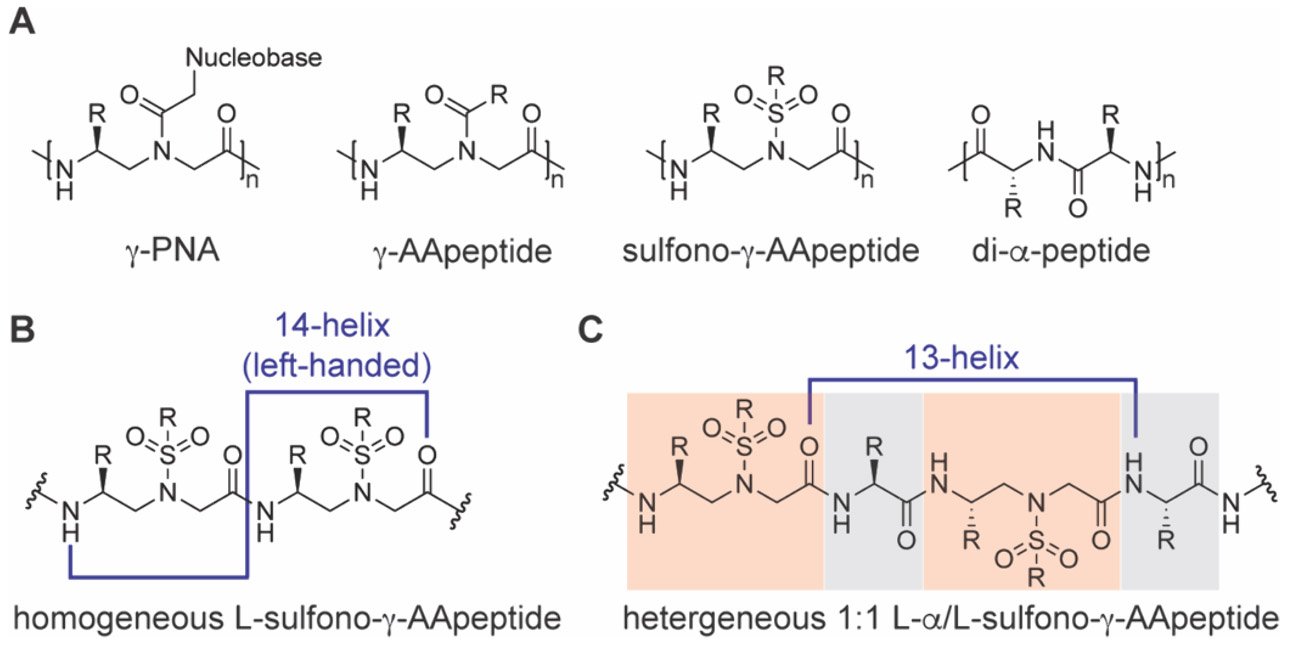

Designer peptides and peptidomimetics have previously been categorized into four classes.22 Class A represent minimally modified peptides wherein small changes to the backbone or side chains result in structurally stable or more active analogues. Class B are significantly modified with unnatural amino acids forming substantial backbone alterations such as foldamers. Class C are scaffolds that replace the peptide backbone entirely with an unnatural nonpeptidic scaffold but retain side chain functionality. Class D are mainly small molecule-like scaffolds that may mimic the mechanism of peptides but do not have a direct link to structure or design and therefore will not be discussed in this review and have been reviewed elsewhere.22-24

In this review, we will focus on designer peptides and peptidomimetics in four general classes, including: (i) natural product-like macrocyclic peptides (MCPs); (ii) side chain stabilized peptides; (iii) peptidomimetics containing nonnatural backbones; and (iv) synthetic proteomimetics and biologics (Figure 1C). Sections (i) and (ii) mainly cover class A mimetics, whereas section (iii) will discuss class B and class C mimetics. Section (iv) focuses on larger mimetics of protein tertiary and quaternary structures for expanded recognition properties suitable for challenging protein and nucleic acid targets. We will focus on the defining structural features that characterize each class, the breadth of synthetic strategies previously employed to construct each class as well as notable examples of their applications in modulating undruggable disease targets. While there are numerous small molecule and biologic-inspired modalities developed for undruggable targets that may share properties with the classes above, such as class D mimetics and engineered recombinant proteins, we find these to be outside the scope of the current review and direct readers to other excellent recent reviews.3,4,22-27 We will conclude our review with an outlook on the enormous potential of designer peptides, peptidomimetics, and synthetic biologics in targeting the “undruggable” as well as unmet requirements for advancing these promising modalities to the clinic.

2. MACROCYCLIC PEPTIDES

Peptide therapeutics are an attractive modality due to their synthetic accessibility and broad range of targetable biomolecules and interactions. However, naturally derived linear peptides suffer from pharmacological liabilities such as lack of cell entry and rapid degradation by cellular proteases, as well as reduced target affinity and specificity.12-14 Structural preorganization through cyclization—either “head-to-tail” or via interchain cross-links—has been shown to significantly enhance several or all of these pharmacological pitfalls. Indeed, nature has devised numerous routes to biologically active macrocyclic peptides, including head-to-tail cyclized molecules like cyclosporin A, amantins, and somatostatin or depsipeptides such as romidepsin, FK228, and leualacin, and hybrids of similar structure.28-30 Typically, these molecules are synthesized by nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) clusters and further modified with noncanonical peptide bonds, amino acid side chains, and other modifications.31 Researchers can take inspiration from the structure–function properties of these natural products to initiate campaigns to produce synthetic macrocyclic peptides (MCPs) with desirable properties.32 Due to their larger surface areas, arrayed amide backbone and chemically diverse side chains, synthetic MCPs could be developed to target traditional ligand binding pockets, as well as shallower allosteric pockets and grooves on the surface of or at the interface between proteins; these target features may be more prevalent in undruggable targets. Therefore, MCPs occupy a Goldilocks zone of physicochemical space to yield FDA-approved therapeutic molecules.33-36 In this review, we focus on synthetic MCPs containing a natural peptide backbone with the formation of at least one covalent cyclic linkage to induce conformational constraints. While natural product-derived and synthetic MCPs such as cyclotide scaffolds have been developed to target classically druggable targets such as enzymes and receptors,29,37-39 here we will focus primarily on their development for undruggable targets and surfaces.

2.1. Design Principles for MCPs

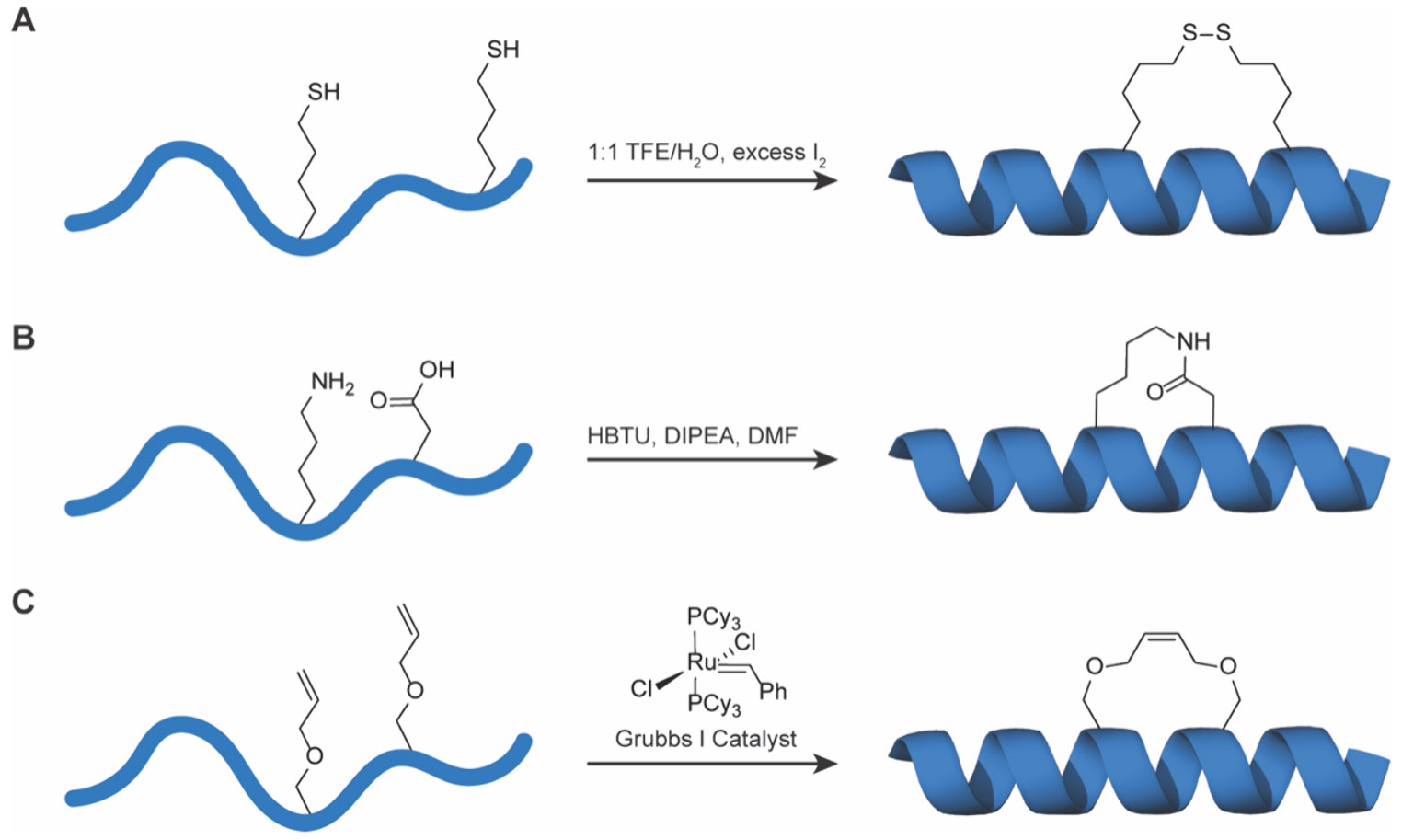

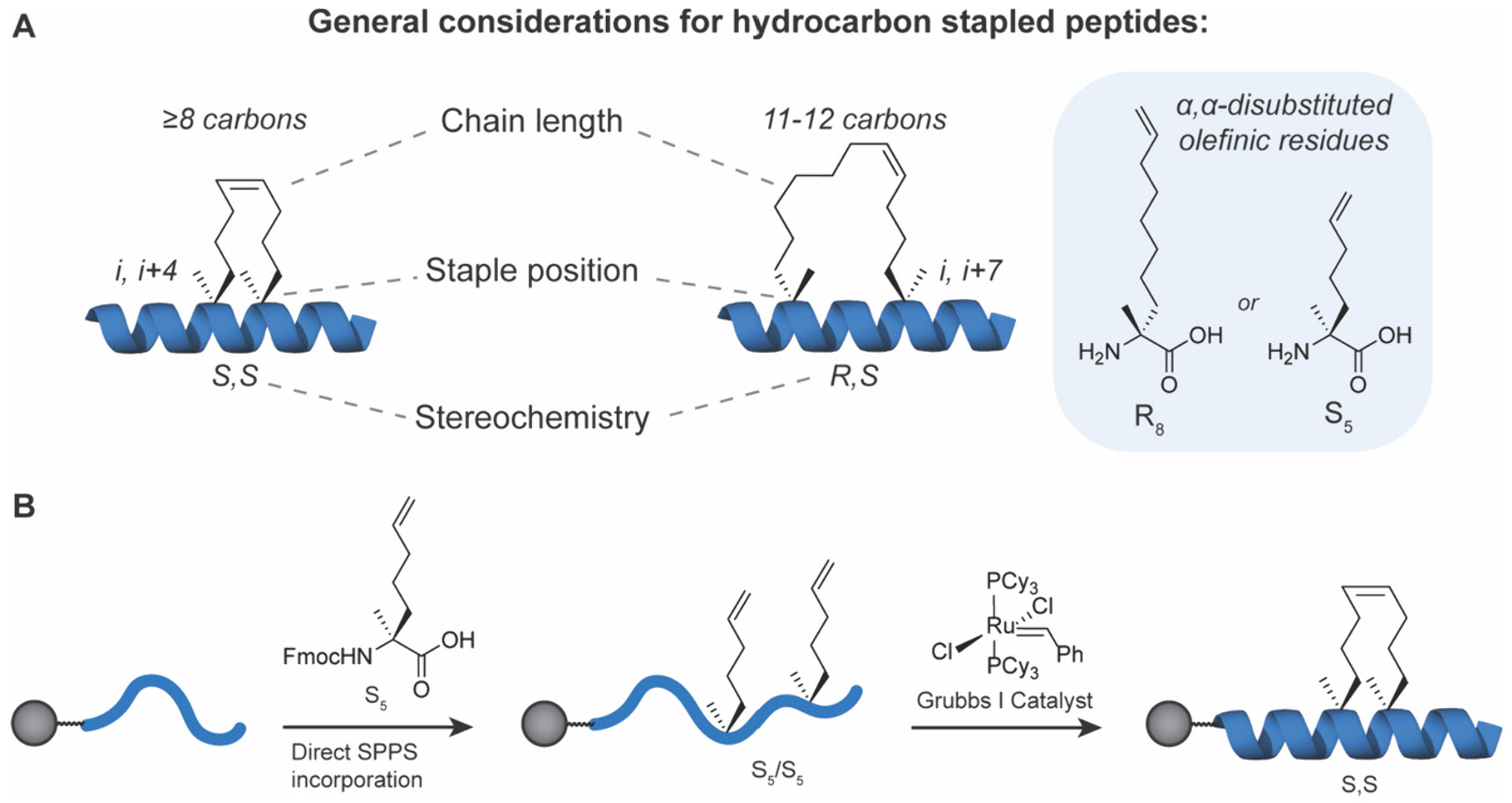

MCPs are generally constructed with ~5–20 amino acids to span a molecular weight range of ~0.5–3 kDa, making these one of the smallest classes of designer peptides (Figure 1C). This size confers small molecule character that is beneficial for biological applications. Conformational constraint and preorganization is often accomplished via head-to-tail cyclization with or without additional side chain linkages, which collectively introduce significant rigidity into MCP backbone conformations. In addition to protecting structures from metabolic degradation, the preorganization of active binding poses can reduce the entropic cost of folding during target binding. Common cyclization chemistries typically must proceed with high yield, chemoselectivity and operate under aqueous reaction environments. These include disulfide bridges, thioether linkages, amide bonds, unsaturated hydrocarbons, and cycloaddition adducts, for example through [3+2] azide–alkyne Huisgen “click” chemistry or [4+2] Diels–Alder cycloadditions (Figure 2).40-42 These common approaches each serve to provide unique properties that have advantages and disadvantages dependent upon application and design.

Figure 2.

Common macrocyclization adducts (right) generated from common synthons (left).

In general, the design, selection, and optimization of MCPs for undruggable targets should aim for several attributes including: (i) strong binding affinity and specificity for the protein of interest (POI); (ii) the ability to penetrate cellular membranes and access intracellular targets; (iii) high metabolic stability, and (iv) high bioavailability.6 Owing to their larger size and chemical properties, many FDA-approved MCPs33-36 do not adhere to Lipinski’s rule-of-5 or similar paradigms.43-46 Instead, many bioactive MCPs are thought to exhibit cell permeability and high bioavailability through their potential for “chameleon-like” structural character. In this theory, MCPs can adopt a conformation with a high polar surface area (PSA) and more exposed backbone NH bonds to retain solubility in aqueous conditions but adopt an alternative conformation minimizing PSA and exposed NH bonds when diffusing into hydrophobic membranes.47-50 Baker and colleagues explored this principle in examining MCPs from 6 to 12 amino acids in length, and found that internal hydrogen bonds and minimal exposed polar groups were critical to achieve cell entry.51 They designed cis/trans MCPs that isomerized around one peptide bond to achieve the chameleonic property, where the cis state is solvent exposed and the trans state leads to the formation of internal backbone hydrogen bonds. These findings agree with previous studies showing that backbone hydrogen bond matching as well as amide N-methylation and masking polarity contribute significantly to MCP cell uptake and oral bioavailability.52 Monovich and co-workers performed an extensive study assessing the properties of 6-, 7-, and 8-mer MCPs to determine that two factors are highly predictive of oral bioavailability and membrane permeability: (i) the lowest free energy of transition, ΔG*transfer, between aqueous and membrane states and (ii) the lowest number of solvent exposed backbone NH groups in an MCP.53 This study supported many others suggesting that the backbone plays a more critical role in permeability as opposed to the side chain, hence cell permeable MCP backbones with varied side chains could be used as a framework for large array library formats for discovering ligands to therapeutically relevant targets. For further discussion on MCP chameleonic design principles, refer to the excellent review by Monovich and co-workers.54

Although the smaller size and constrained structure of MCPs generally improves cell uptake, this does not directly translate for every design. Therefore, a simple and accessible method that many designer peptides have adopted is appending a cellpenetrating peptide (CPP). CPPs are short peptides that can cross the cell membrane, which facilitates the transport of various attached cargo.55-58 Typical CPP examples such as Tat,59 penetratin,60 or octa-arginine61 are popular choices for conjugating to MCPs, though amphipathic and anionic CPPs have also been reported.55,62 Physicochemical properties such as formal charge and hydrophobicity correlate with cell penetration, and CPPs are internalized through clathrin- and caveolin-independent, energy-dependent endocytosis pathways involving sulfated cell surface proteoglycans.56 Given that linear peptides suffer from protease digestion, cyclic CPPs have been developed that are more metabolically stable and membrane permeable than their linear counterparts and are nicely described in a recent review by Parangi, Tiwari, and co-workers.63 While appending CPPs to MCPs is useful for improving bioactivity, there have been no therapeutics containing a CPP approved by the FDA to date, likely due to potential for cellular toxicity, adverse immune response, and poor efficacy arising from the lack of specificity due to the CPP moiety.64

To create MCPs with desirable pharmacological properties without the need for external modifications such as CPPs, a team from Chugai Pharmaceuticals analyzed several properties inherent to MCPs that would yield the most pharmacologically viable molecules.65 Using naturally cell permeable cyclosporine A as a model, they designed and tested 553 analogs to understand the critical properties that drive potential therapeutic efficacy. They determined desirable properties for metabolic stability and cell uptake include high hydrophobicity, a high permeability coefficient, a medium-sized ring between 8 to 11 amino acids, extensive backbone amide N-alkylation of 6 or more residues, and reduced side chain polarity (Figure 3). They also found that, for medium-sized rings, oxidative metabolism is dominant over enzymatic hydrolysis, and MCPs of 8 residues, while having higher average membrane permeability than MCPs of 11 residues, have higher oxidative metabolism. Smaller rings more susceptible to oxidative metabolism are unlikely to overcome this limitation without decreasing lipophilicity necessary for membrane permeability. However, ring size and residue identity also play important roles in target recognition that must be balanced with desirable metabolic stability.13 While these studies greatly improved our knowledge of MCP design, general strategies for designing therapeutically viable MCPs remain elusive owing to the greater complexity afforded by larger and more diverse molecules and interactions. However, interest in MCPs as a drug modality is increasing exponentially with many biotechnology firms exploring MCP therapeutic discovery platforms,13,44 and an increased interest from large biopharma groups in exploring this modality for a range of targets.

Figure 3.

Summary of common structural features and modifications of drug-like MCPs. Representative features are highlighted on the structure of cyclosporin A, alongside a representative summary of structure–function correlations from a study65 that systematically explored cyclosporin A-derived macrocycle libraries (right).

2.2. Discovery, Design, and Synthesis of MCPs for Challenging Targets

MCPs are versatile and can be expressed by natural machinery or produced synthetically utilizing the diverse chemistries. Synthetic optimization typically follows derivatization from existing scaffolds or de novo selection from large combinatorial libraries in high-throughput screening. In the following section, we will discuss how MCPs are developed through rational design or selection from large libraries in multiwell screening, one-bead-one-compound, DNA-programmable libraries, phage display, mRNA display, and in-cell formats. We will also discuss the common synthetic methods to form the MCP libraries and provide key examples that have focused on generating chemical probes and therapeutics for undruggable targets.

2.2.1. Rational Design.

The majority of MCP rational design campaigns begin with the identification of specific binding epitopes within naturally occurring proteins and peptides that are potentially amenable to ligand development and optimization (Figure 4A). Early structure-blind approaches involved synthesis of cyclic analogs of complementarity determining regions (CDRs) of antibodies or endogenous peptides such as enkephalin to target various POIs.66-68 As more cocrystal structures of apo- or bound target structures have become publicly available, rational or structure-based drug design (SBDD) approaches have become more common. This methodology has been used to find MCPs that interfere with interactions such as TNKS-AXIN in WNT signaling,69 RGS4,70 and TGF-β-SMAD7.71 A notable recent example for a rationally designed MCP targeting an undruggable interaction is between the transcription factor TEAD1 and the coactivator YAP1, which represent a TF-co-activator complex that is central in the Hippo signaling pathway.72 The TEAD1/YAP1 interaction is highly implicated in many cancer types, and abolishing this interaction leads to the suppression of cell proliferation.73 Hu and co-workers examined the structure of the TEAD1/YAP1 interaction and identified a looped-coil segment of YAP1 that interacts with TEAD1.74 Using this structure as a guide, they generated a series of MCPs via disulfide bridging, and discovered optimized molecules that could bind to TEAD1 with greater potency than wild-type YAP1. Subsequent work has further focused on this interaction to identify small molecules that can disrupt this binding interaction,75 highlighting an important byproduct of identifying peptide leads to ultimately develop more drug-like small molecules. In a separate study, an MCP derived from the BB loop in MyD88 was developed to interrupt protein dimerization.76 MyD88 is an adaptor protein critical in the TLR and IL-1R signaling pathways that functions via dimerization and overexpression in cancers leads to overactivation of NF-κB and cancer metastasis.77 Nussbaum and co-workers identified a sequence from the BB loop that controls dimerization and synthesized an MCP via an amide linkage to form c(MyD 4-4).76 c(MyD 4-4) blocked the TLR/IL-1 signaling pathway both in vitro and in mice models. In a subsequent study, they sought to increase the bioactivity of c(MyD 4-4) and enable oral administration by myristoylating the MCP at the N-terminus.78 Myristolyation led to a significantly improved cellular bioactivity and in vivo oral bioavailability while still retaining activity in mice models. In addition to these PPIs, there are many MCPs that have been rationally designed against amyloid peptides, which have recently been covered in an excellent review by Khairnar et al.79

Figure 4.

Rational design of MCPs. A) MCP starting points can be directly extracted from key interacting loops discovered in natural protein–protein interactions. B) Structure of stonin2 (orange/green) bound to Eps15 (cyan), identified “hot loop” by LoopFinder highlighted in green. PDB: 2JXC. C) Chemical structure of Eps15 inhibitor ST1-oxy identified by LoopFinder. O-xylene macrocyclization linker is highlighted in green.81

One way that potentially druggable PPI interacting loops, also called “hot loops”, can be identified is through the program LoopFinder, designed by Kritzer and co-workers.80 Methodologically, LoopFinder identifies “hot loops” if the interacting loop fit one of three parameters: (i) three or more hot-spot residues (defined as ΔΔGresidue ≥ 1 kcal mol−1), (ii) two consecutive hot-spot residues, or (iii) the average ΔΔGresidue over the entire loop is greater than 1 kcal mol−1. Most loops identified in this approach were secondary structures such as β-turns and β-hairpins, though many had noncanonical structures. In the updated version, they improved on the energy calculations and benchmarked it against known PPIs to refine the selection criteria for an identified “hot loop” to (i) an average ΔΔGresidue ≥ 0.6 Rosetta Energy Units (REU, roughly equal to 1 kcal mol−1), (ii) three hot spot residues (ΔΔGresidue ≥ 0.6 REU), and (iii) a greater than 50% of binding energy contributed by the loop, represented as the sum of ΔΔGresidue.81 Loops that fulfilled all three criteria were seen as the best starting points for MCP development for a given target of interest. A close examination of the 210 “hot loops” that fulfilled all three criteria suggests that MCPs can only mimic some hot loops due to conformational constraints.82 It also suggests that, while larger MCPs can accommodate the native conformation of the hot loop, this must be balanced against the entropy loss of the larger MCP upon binding. One of the loops that fulfilled all three criteria is found in the interaction between Eps15 and stonin2, for which there are no known high affinity inhibitors (Figure 4B).81 Eps15 is a clathrin-associated protein and part of the endocytosis machinery83 and its interaction with stonin2 leads to the recruitment of AP-2 and endocytosis, which is implicated in Ebola infectivity and potentially other diseases.84 After identifying the loop on stonin2, cysteine or penicillamine residues were appended to both termini of the peptide sequence, and a panel of dithiol, bis-alkylation linkers were tested to cyclize the peptide by forming stable thioether linkages. The lead compound, ST1-oxy, was flanked by two cysteine residues and cyclized using dibromo-o-xylene to generate a selective and high affinity (Kd = 0.33 μM) ligand for Eps15 (Figure 4C). A 2D-NMR structure in water confirmed ST1-oxy recapitulated the structure of the stonin2 hot loop, displaying the powerful tools for computationally defining native protein structures for the discovery of designer peptide ligands.81

Expanding the discovery of cyclization-amenable loops at protein interfaces can identify starting points for chemical probe development. Building upon the LoopFinder work by the Kritzer group, Burgess and co-workers recently developed a virtual library approach termed backbone matching (BM) that is able to sample the conformations of cyclo-organopeptides composed of 4–10 residues cyclized with various organic elements through amide bonds.85 Compounds capable of adopting the proper low energy conformation in solution corresponding to the target backbone structure are prioritized for further evaluation and development. Using this approach, they identified and validated MCP inhibitors for interactions between iNOS/SPSB2 and uPA/uPAR. They also discovered candidates for 1245 of the 1398 hot loops screened, suggesting a plethora of other target interfaces that may be interesting to pursue. The continued alignment of computational methods with experimentally determined protein structures for discovery and validation of interacting loop structures has been and will continue to be a powerful approach to rationally design MCP probes and therapeutics.

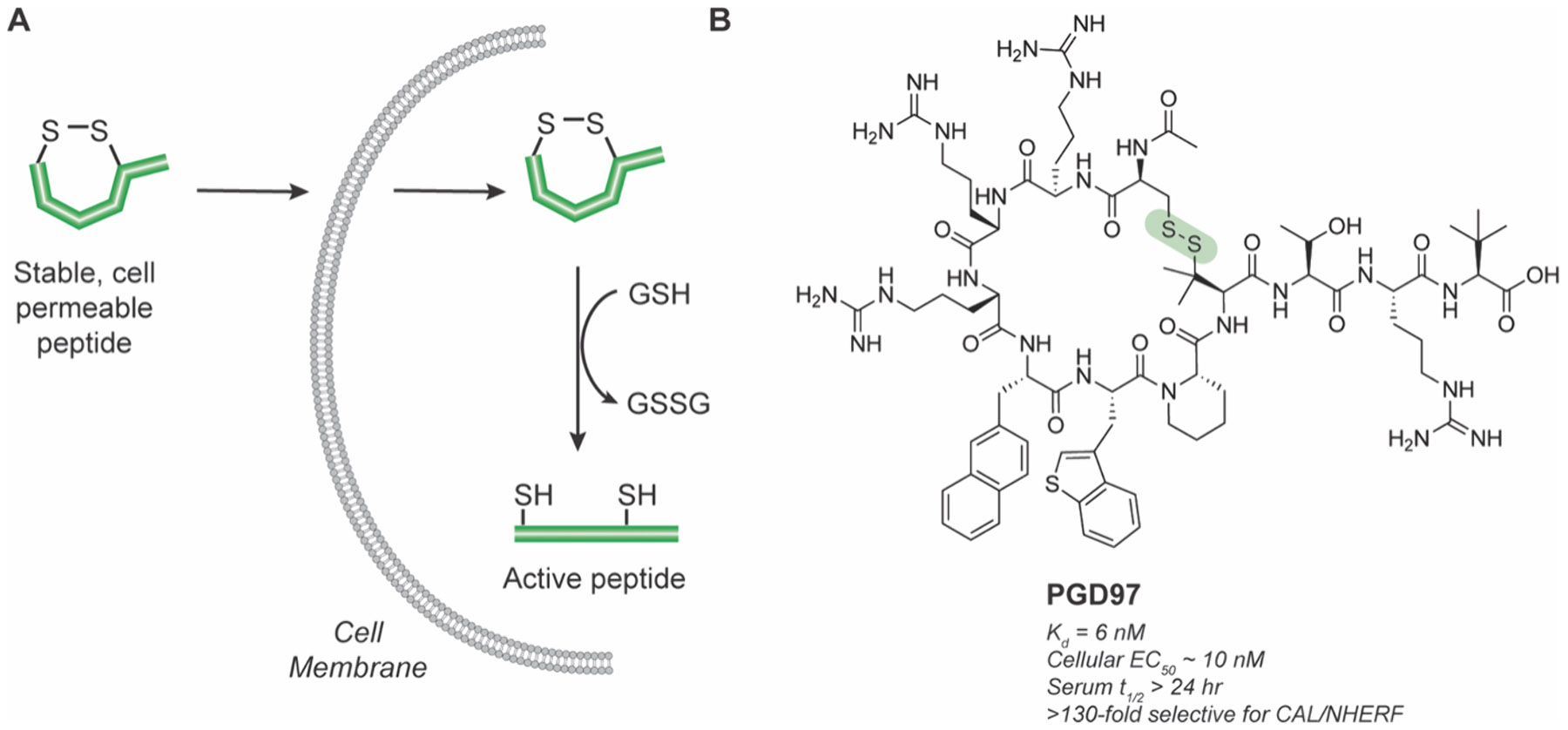

MCPs derived from natural protein surfaces can also be designed based on more active linear epitopes, which can be cyclized then reversed to develop pro-drugs. For example, on disulfide linked MCPs, a reversible cyclization strategy could leverage intracellular glutathione to reduce the disulfide bridge and linearize the peptide upon cell uptake (Figure 5A). The cyclic peptide gains stability and cell permeability afforded by rigidification but retains the linear binding epitope once inside of cells. Using this strategy, Dougherty et al. designed an MCP derived from a section in the C-terminus of CFTR to inhibit the intracellular CAL-CFTR interaction to prevent lysosomal degradation of the CFTR ion channel, a potential treatment strategy for cystic fibrosis.86 Although symptomatic treatments using small molecules for dysregulated ion channels exist, direct modulation of intracellular CFTR mutant interactions remains challenging. In this design, a disulfide linked MCP, PGD97, containing a cell penetrating handle was generated that exhibited high affinity and specificity for the PDZ domain of CAL and an in vitro serum half-life over 24 h (Figure 5B). PGD97 acted as a stabilizer of F508del-CFTR and improved the CFTR function in cells. This strategy is also amenable to bicyclic peptides (BCPs). Qian et al. designed a disulfide BCP targeting the undruggable interaction between NEMO and IKK-β, which are part of the IKK kinase complex that mediates NF-κB signaling and is implicated in cancer and autoimmune diseases.87-91 Similar to the CAL-CFTR inhibitor, a cyclic recognition domain was connected to a cyclic CPP to ensure entry into the cell to generate a BCP. The recognition domain binds to NEMO in linear form but not in cyclic form, thus acting as a prodrug to only function in reducing environments.92 Although only achieving modest inhibition (IC50 ~20 μM), this strategy increases metabolic stability and cell permeability. Other approaches to create prodrug MCPs to function in reducing or oxidative environments take advantage of the redox lability of disulfides.93

Figure 5.

Pro-drug disulfide linked MCPs. A) Dithiol cyclization improves cell permeability and is reduced by glutathione to produce active linear peptide in cells. B) Structure of stable, cell permeable pro-drug CAL-CFTR inhibitor PGD97. The reversible disulfide bond is highlighted in green.86

Recent advances in computational approaches such as docking analysis and molecular dynamics simulations have contributed to the design of MCPs for challenging POIs. Baker and co-workers used computational analysis to design an MCP that could specifically bind HDAC6 over HDAC2, which is a notoriously difficult challenge to distinguish HDAC family members with small molecules or peptides.94 They started with an “anchor” moiety ((2S)-2-amino-7-sulfanylheptanoic acid; SHA), based on a pan-HDAC inhibitor that coordinated with the zinc ion in the HDAC active site to situate the model peptides to the HDAC surface (Figure 6A). Their first attempt used two peptides of known structure and a library of previously generated MCPs of 7–10 residues that were docked to the anchor.95 Using this method, they found an MCP that was decently potent in vitro (sub-μM IC50) but was not specific for either HDAC. They then added an additional tryptophan anchor because indole moieties are present in some known small molecule HDAC inhibitors before extending the peptide to form new MCPs. This MCP also displayed good affinity but little selectivity. From there, they sampled and optimized the torsional angle of the anchors. This led to an MCP designated des4.3.1 that was 88-fold selective for HDAC6 compared to HDAC2 (Figure 6B).94 Satisfying both binding and structural criteria is essential for generating de novo highly selective and efficacious MCP inhibitors. This and related studies are notable because they interrogate not only on-target95-99 but also propensity for off-target specificity, which is essential for the concurrent development of specific probes and therapeutic leads.

Figure 6.

Docking analysis and molecular simulations select for HDAC6-specific inhibitors. A) Crystal structure of des4.3.1 bound to HDAC6 anchored with SHA. PDB: 6WSJ. B) Chemical structure of HDAC6-specific inhibitor des4.3.1.94

The examples above demonstrate the key advantage of rational design: the lower barrier of entry to discover an MCP derived from a native protein structure. Identifying a potential interactor does not require lengthy and sometimes complicated screening approaches. However, there are a few limitations to the rational design approach: (i) requires prior knowledge of the target structure or interaction surface to identify potential ligands, (ii) identified ligands may not be amenable to structural stabilization after isolation, as proper folding may be dictated by interactions within the entire protein structure or interface,100 and (iii) identified ligands may not represent the optimal binders as not all combinatorial space is explored compared to screening approaches. Many of these shortcomings are being addressed with the integration of computational design and virtual screening, which has and will continue to explode in coming years with improvements to computational methods and technologies. For example, Des3PI101,102 and cPEPmatch,103 have been used to predict MCP binding to classically undruggable PPIs but have yet to be substantiated with experimental results. Improved structural prediction methods such as AlphaFold104 and RoseTTAFold105,106 provide further tools for predicting ligand interactions. For further reading on the quickly evolving computational approaches to design macrocyclic peptide interactions, we point readers to other reviews.107-110 While rational design approaches serve as solid starting points for MCP discovery particularly for identifying ligand-protein interactions, many undruggable targets are characterized by large, flat surfaces and disordered structures, and therefore unlikely to possess obvious domains from which to derive a potential ligand. For these challenging targets, large compound library screening is a more powerful approach for the de novo discovery of MCPs as described in the following sections.

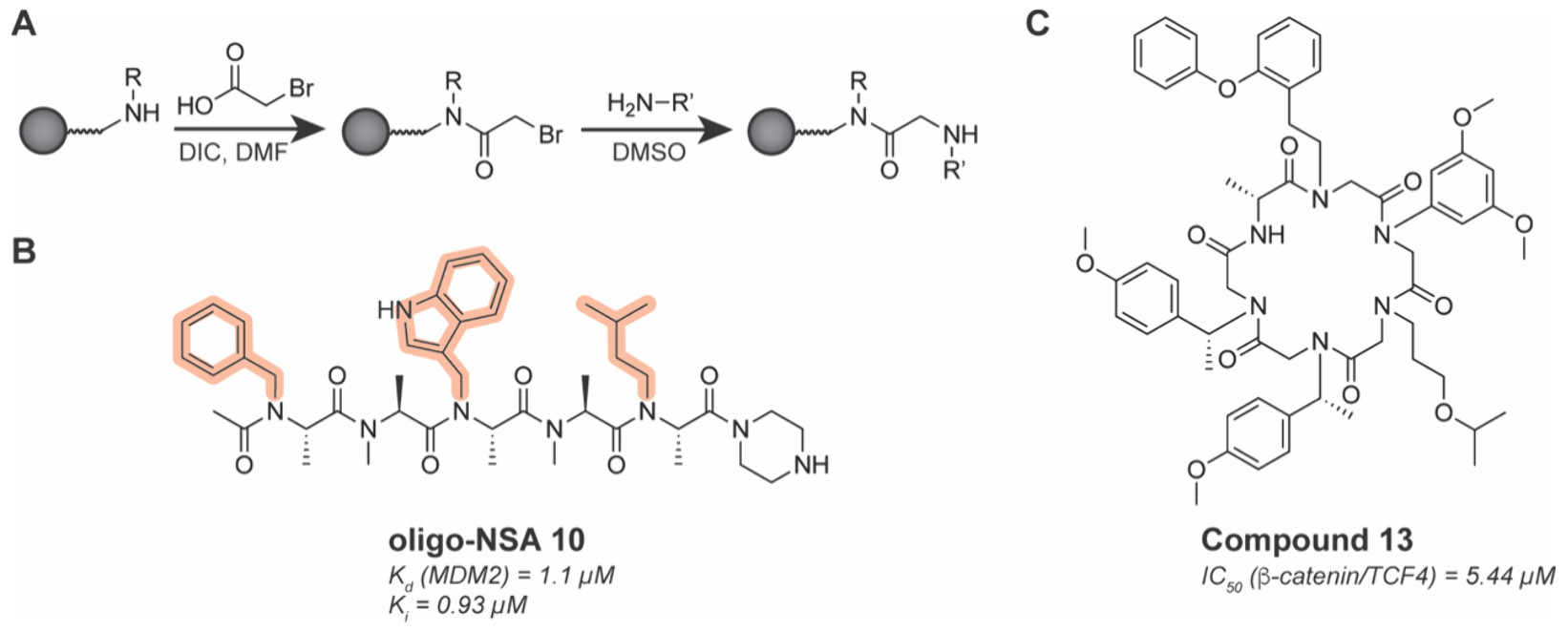

2.2.2. Multiwell MCP Synthesis and Screening.

Multiwell screening involves plating a library of known compounds into a microtiter plate for subsequent biochemical or cellular testing, or concurrent synthesis and testing in multiwell formats. These methods are now anchor approaches to library screening in academia and pharmaceutical companies.111 Tranzyme Pharma demonstrated an early approach to multiwell screening of an MCP compound library, with the main scaffold containing a tripeptide with a tether moiety bridging the two termini via amide linkages (Figure 7).112 By diversifying the tethers used and incorporating ncAAs, they generated a 104 member library that was used to design MCPs to targets such as the motilin receptor and the ghrelin receptor and others that made it into clinical trials.113-117

Figure 7.

Scheme for the combinatorial synthesis of a diversified tripeptide MCP library in multiwell format, representing an early example reported by Tranzyme Pharma.112 Bts: benzothiazole-2-sulfonyl, Ddz: α,α-dimethyl-3,5-dimethoxybenzyloxycarbonyl; DIAD: diisopropyl azodicarboxylate, MP: microporous, PS: polystyrene.

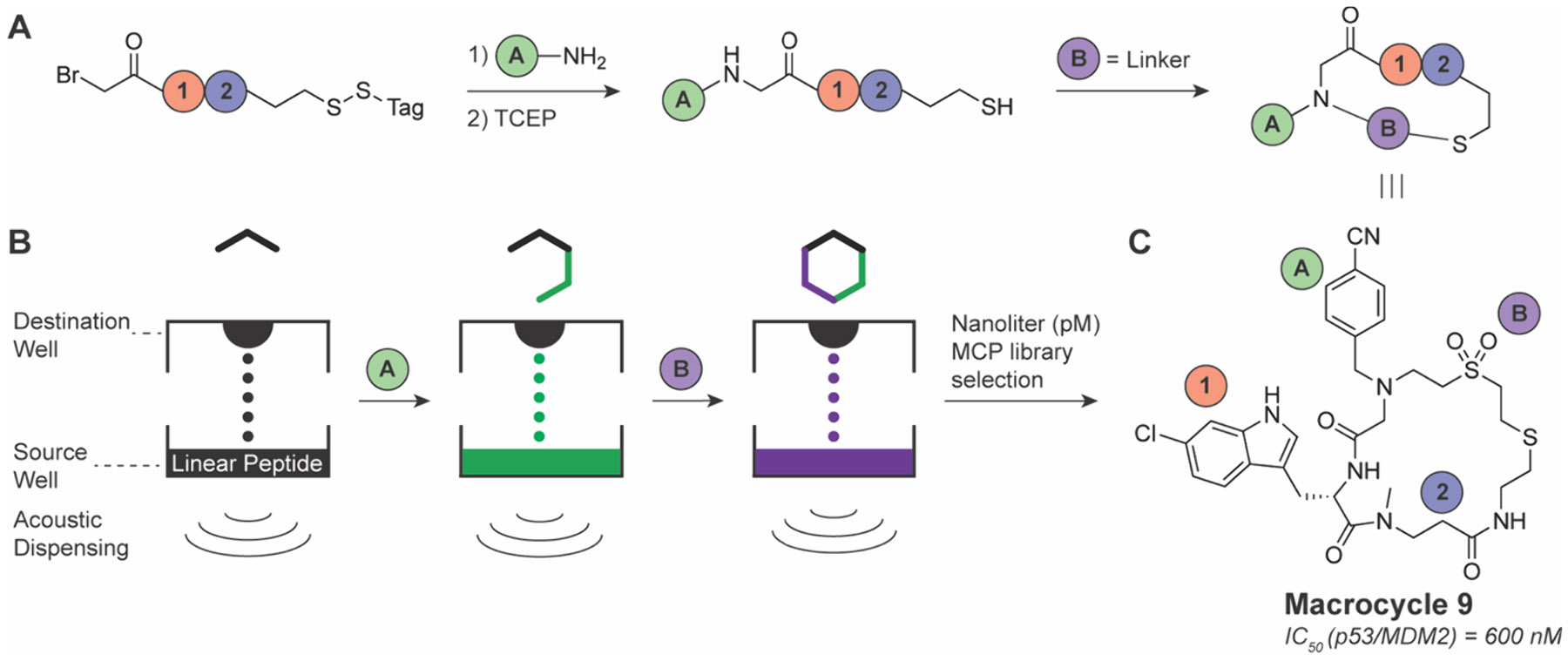

Many alternative approaches for the synthesis and screening of diverse MCP libraries have been developed in recent years. For example, Heinis and co-workers have reported the generation of low molecular weight MCPs through the cyclization of tri- and tetrapeptides via thioether linkages.118-122 In one report they synthesized a core of Na-bromoacetyl-activated linear peptides, which were reacted with diverse primary amines.119 Reduction of a masked thiol and introduction of a reactive linker moiety thus enabled cyclization with the newly formed secondary amine for MCP generation. This approach used acoustic liquid transfer to generate macrocyclic peptides at a picomolar scale, which minimizes the use of reagents and decreases the cost of producing the macrocyclic library (Figure 8A,B). This library of 2700 MCPs was tested against the classically undruggable p53/MDM2 interaction, which is a critical interaction in numerous cancers and a bellwether target used by many studies for designer peptide synthesis.123,124 Screening the library in a competition format against a displacement peptide bound to MDM2 in a 384-well plate format resulted in the identification of several hit scaffolds with low-to-sub-μM inhibition, including the sulfone containing macrocycle 9 (Figure 8C).119

Figure 8.

Nanoliter (pM scale) MCP library preparation using acoustic liquid transfer. A) General reaction scheme to prepare dipeptide library. B) Schematic of acoustic liquid transfer for small volume mixing. C) Chemical structure of macrocycle 9.119

Recently, a new “blind” screening strategy termed Peptide Exploration Platform with Tag-Free Intramolecular Chemistry (PEPTIC), was introduced for label-free MCP library synthesis.125 This platform uses “CyClick” chemistry to cyclize peptides, where an N-terminal amine reacts with an embedded C-terminal aldehyde to generate a 4-imidazolidinone cyclization group (Figure 9A).126 After screening for hit compounds binding to a POI, MCPs are then linearized using a DeClick approach, wherein hydrolysis of the 4-imidazolidinone linker occurs at high temperatures and low pH (pH 2–3). Remaining hits are then deconvoluted using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to determine the MCP sequence. This selection strategy is beneficial as it eliminates the need to append an additional biomolecule tag for identification, which may interfere with the intended interaction and lead to false-positive or false-negative results. As a proof-of-concept, this strategy was used to select an MCP that binds to an HIV-1 capsid protein that is critical in viral replication to prevent its interaction with other proteins.127 A generated hit molecule, cyFG-3, displayed submicromolar affinity for the capsid protein (Figure 9B).125

Figure 9.

Tag-free PEPTIC selection strategy for MCPs. A) Schematic workflow of PEPTIC. B) Chemical structure of cyFG-3.125

2.2.3. One-Bead-One-Compound MCP Libraries.

A classic approach to MCP library generation and screening is the use of “one-bead-one-compound” (OBOC) libraries.128 Here, MCPs are synthesized through a split-and-pool model, where individual beads react with a single amino acid at a time before being split to react with another amino acid. This continues until a library of up to 109-members is created that can then be screened against various targets, after which hit compounds are sequenced via Edman degradation or mass spectrometry.129-131 An early example of OBOC used to select MCPs against intractable targets was the discovery of inhibitors specific to HDAC6, which is implicated in the development of several cancers and neurodegenerative disorders.132 Ghadiri and Olsen designed an OBOC MCP library based on a α3β tetrapeptide scaffold cyclized via head-to-tail cyclization.133 Initial attempts to use a fully α-amino acid tetrapeptide failed due to difficulty in lactam formation, presumably due to high ring strain.134 Including an additional backbone methylene in the single β-amino acid residue led to a much higher yield of lactamization.134,135 After two generations of focused OBOC selections determined by structure–activity relationship (SAR) analysis, a highly potent and HDAC6-selective MCP emerged, which was confirmed in cells by observing increased α-tubulin acetylation, a hallmark of HDAC6 inhibition. Finally, they explored inhibition of cell proliferation in HeLa cells and showed only compounds that also inhibited HDAC1 reduced cell growth, suggesting HDAC1 is much more important for cell viability than HDAC6.133 Since then, OBOC has been used to discover MCP inhibitors for other difficult-to-drug targets including the RGS4/Gα0 interaction,136 PTP1B,137 c-MYC,138,139 hLysRS/CA,140 and the calcineurin/NFAT interaction.141 For additional reading on OBOC and similar methods, we point readers to other reviews.142,143

The early version of OBOC had two significant limitations that hampered its widespread use: (i) high false positive rates and (ii) difficulty in sequencing MCPs.144 The first problem has been improved by lowering the density of peptide ligand on beads, testing diverse bead substrates and also requires ad hoc optimization based on the libraries and targets of interest. Solutions to the second identification problem have been approached through several strategies that incorporate a second molecular barcode onto each bead, including DNA, small molecules, and peptides themselves in a so-called one bead two compound (OBTC) approach. OBTC screens a linear peptide barcode that identifies the MCP sequence that is synthesized in the interior of the bead and does not interfere with selection (Figure 10).145-147 Additional innovations include DNA-encoded solid phase synthesis to encode peptide information into DNA barcodes read by sequencing.148 A seminal example using OBTC involved screening the Ras–Raf interaction, and more generally, the interaction of Ras with its effector proteins. The Ras family of proteins are a group of G-proteins (K-Ras, H-Ras, N-Ras) and are a hallmark of cancer, with 30% of human cancers having at least one Ras gene mutated.149 Ras has over 50 different effector proteins that interact with and modulate Ras signaling, with the most famous of these being Raf kinase. Pei and co-workers focused on a specific K-Ras mutation, G12V and discovered a peptide termed peptide 12, that has submicromolar in vitro IC50 values.150 It bound specifically to K-Ras(G12V) but did not have activity in cells due to poor cell uptake. To improve cell uptake and increase potency, a second-generation MCP library was generated with OBTC.151 Optimization of the cyclic peptide led to cyclorasin 9A5, which exhibited an in vitro IC50 value of 120 nM and an EC50 value of 3 μM in cells and prevented Ras signaling events such as phosphorylation of Akt. To further increase cell uptake, they rescreened using OBTC with a bicyclic peptide framework where one of the cycles was a cell-penetrating peptide (CPP).152 With this BCP framework, they generated peptide 49 that selectively bound to K-Ras(G12V) and exhibited good cell penetration (Figure 11). Peptide 49 inhibited Akt phosphorylation in cellulo and reduced proliferation of H1299 lung cancer cells with an EC50 value of 8 μM. However, peptide 49 displayed a higher affinity for inactive state Ras·GDP over active state Ras·GTP, leading to high concentrations required to inhibit cell proliferation. Following this, they sought to make a pan-K-Ras-GTP MCP inhibitor.153 Using OBOC based on a previous design, cyclorasin B3-4, they screened to find a BCP that preferentially bound to Ras-GTP. After a comprehensive optimization campaign, cyclorasin B4-27 was developed as a 10-fold selective inhibitor of K-Ras-GTP over K-Ras-GDP (Figure 11). B4-27 was successful in acting as a pan-Ras inhibitor against various Ras mutant cancer lines and reduced proliferation with modest potency (single-digit μM EC50 values). Importantly, B4-27 exhibited a > 24 h half-life in vitro in human serum and significantly reduced tumor growth in A549 xenograft models following subcutaneous administration.154

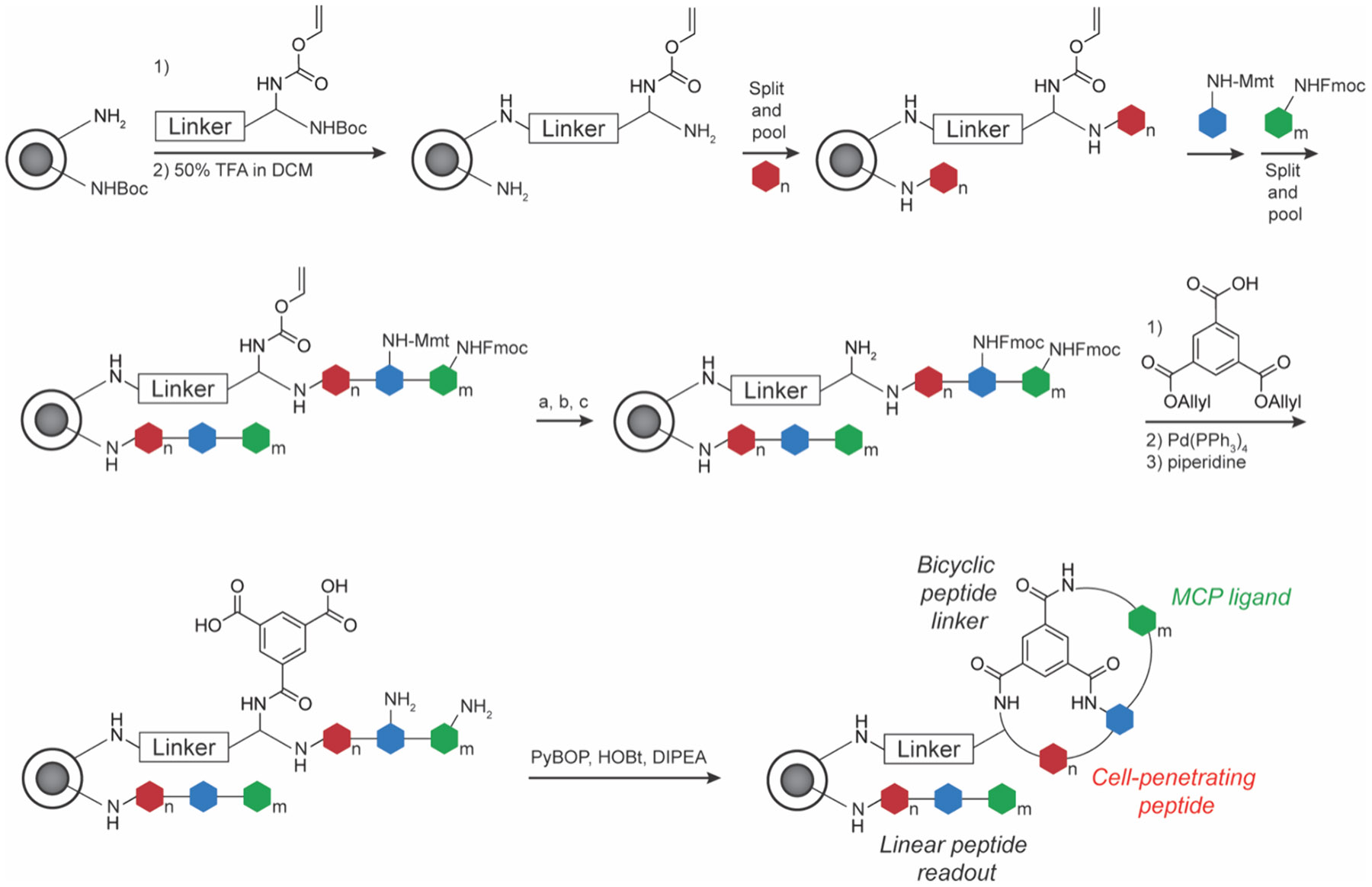

Figure 10.

One-bead-two-compound BCP library preparation using standard SPPS chemistry and split-and-pool diversification. Peptide chain is extended on both inner and outer bead sites. Inner chain is used as the identified readout by LC-MS/MS. Outer chain is cyclized and interacts with POI. (a) 2% TFA in DCM; (b) Fmoc-OSu/DIPEA in DCM; (c) Pd(PPh3)4.147

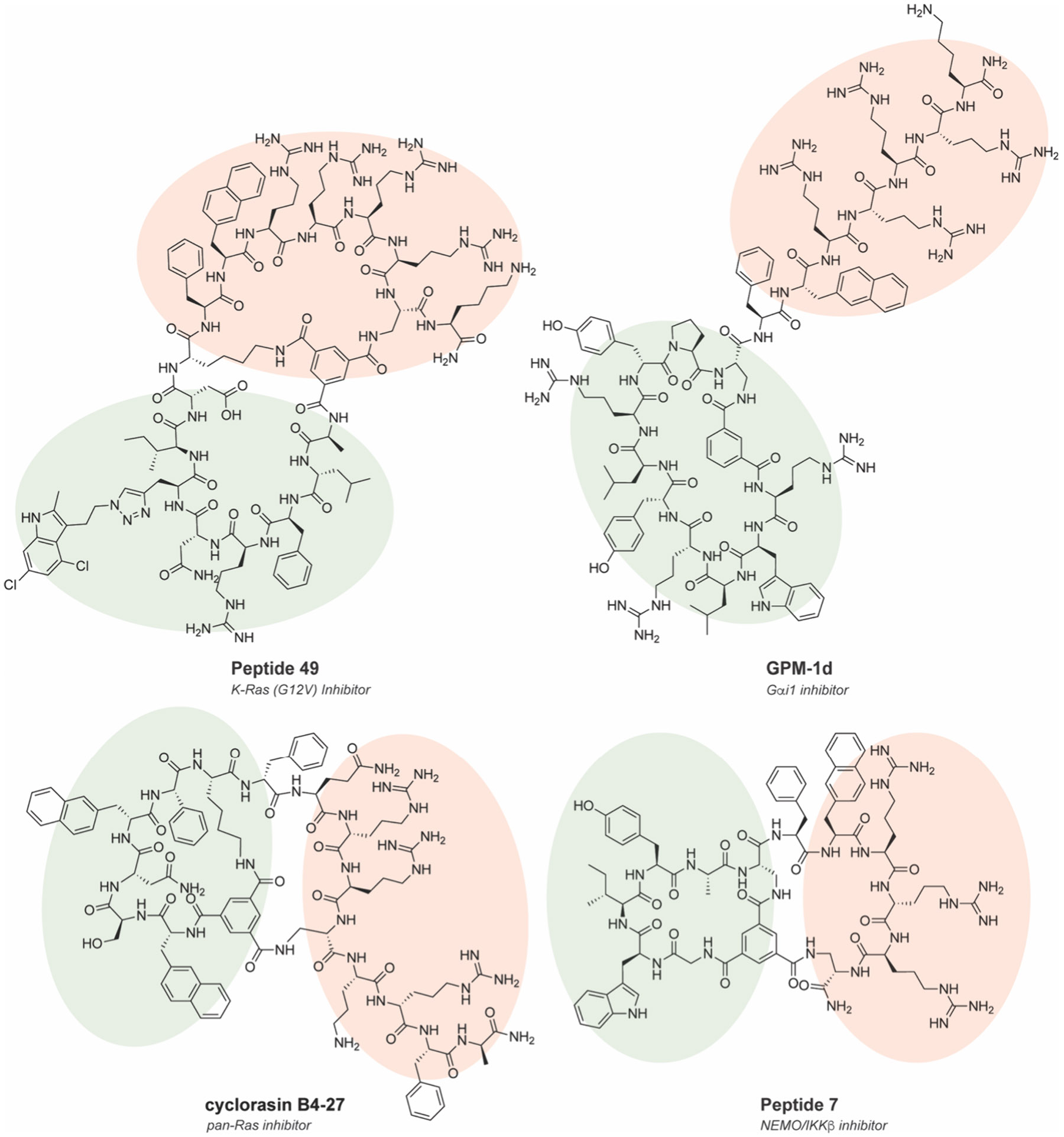

Figure 11.

Chemical structures of CPP-MCPs selected from OBOC or OBTC libraries. Peptide 49152 and cyclorasin B4-27153 target Ras interactions, GPM-1d155 targets Gαi1, and Peptide 7156 targets NEMO/IKK interactions. CPP portion is highlighted in red. POI recognition portion is highlighted in green.

Another important example of using bead-based compound libraries was to target Gαi1 and Gαs, which are heterotrimeric G-protein subunits that function downstream of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) to route signals from GPCRs to downstream effector pathways.157 This pathway has been tied to many different cancers, such as thyroid and adrenal tumors, and directly targeting G-proteins represents attractive alternatives to GPCRs, yet as a class G-proteins remain challenging for conventional small molecules.158 Following a previously discovered MCP binding motif for Gαi1 and Gαs that follows a guanine-nucleotide exchange modulator (GEM) motif of ΦζΦX[±]ΩL, (where Φ is a hydrophobic residue, ζ is a uncharged hydrophilic residue, X is any residue, [±] is any positively or negative charged amino acid, Ω is an aromatic residue, and L is a leucine),159-163 Nubbemeyer et al. generated and screened a OBOC library to discover a peptide, GPM-1, that potently binds to Gαi/s.155 Optimization of GPM-1 by cyclization and conjugation with a CPP to form GPM-1d increased the affinity, structural stability, and cell permeability to modulate the activity of Gαi/s in cell culture in a bifunctional GEM-like manner (Figure 11). Structural analysis using biomolecular simulations analyzed underlying MCP-protein interactions by identifying a network of important H-bonds that occur between the CPP and the protein at Arg14-Asn250 and Arg16-Asn251. In addition, the MCP has a stacking interaction between Tyr8 and the N-terminal Ipa, along with a hydrophobic interaction between Trp2 and binding site.155 A second-generation design identified GPM-3, which binds to active-state Gαi1 with a submicromolar binding constant and was shown to act as a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) modulator.164 In a separate example, Rhodes et al. developed a 2.4 × 109-member OBTC BCP compound library and incorporated cell penetration and cyclization into the activity screen against the NEMO-IKKβ interaction.156 Optimization of the CPP and binding interface produced a BCP, peptide 7, with low μM inhibition activity on viability in multiple ovarian cancer cell lines and reduced canonical NF-κB signaling (Figure 11). Interestingly, as in the previous example, the positively charged CPP portion contributed to the binding of negatively charged NEMO surface, suggesting a potential cooperative approach for improving the affinity and cell permeability for MCP-CPP constructs.156

2.2.4. DNA-Encoded and DNA-Programmed MCP Libraries.

DNA-programmable MCP libraries were first reported using DNA-templated synthesis (DTS) by the Liu lab in 2001.165 DTS uses synthetic oligonucleotide-small molecule conjugates to template ordered monomer coupling as a result of proximity induced DNA hybridization and either regio- or chemoselective reactivity. Sequential addition of DNA-fragment conjugates, which react in a sequence-specific manner based on DNA templates in solution, can generate diverse linear and cyclized peptide, peptide-like and small molecule libraries. This technology was first adapted to generate MCPs by amino acid coupling and cyclization by Wittig olefination to generate libraries ranging from 104 to 105 members (Figure 12A,C).166-168 These libraries were used to screen for bioactive compounds against phosphatases (DEP1, MEG2, PRL2), GTPases (Cdc42, H-Ras-V12, RhoA), antiapoptotic proteins (BCL-XL), nuclear receptors, PDZ and SH2 domains, along with assorted kinases and proteases.168,169 The most potent molecules derived from these screens were focused within kinase and protease families, including Src, VEGFR2, and IDE. Other DNA-programmed MCP libraries, such as those generated by teams at Ensemble Therapeutics and Bristol-Myers Squibb using azide–alkyne cycloaddition (~160,000 members; Figure 12C), have also been successfully screened against the caspase inhibitor proteins cIAPs and XIAP, and could be applied to other challenging protein targets.170 These screens produced highly potent compounds that exhibited modest pharmacokinetic properties (half-lives ~2 h and mean residence times ~2.5 h in mice), and bioactivity against MDA-MB-231 xenografts in mice, showcasing potential for these libraries to produce MCP therapies.

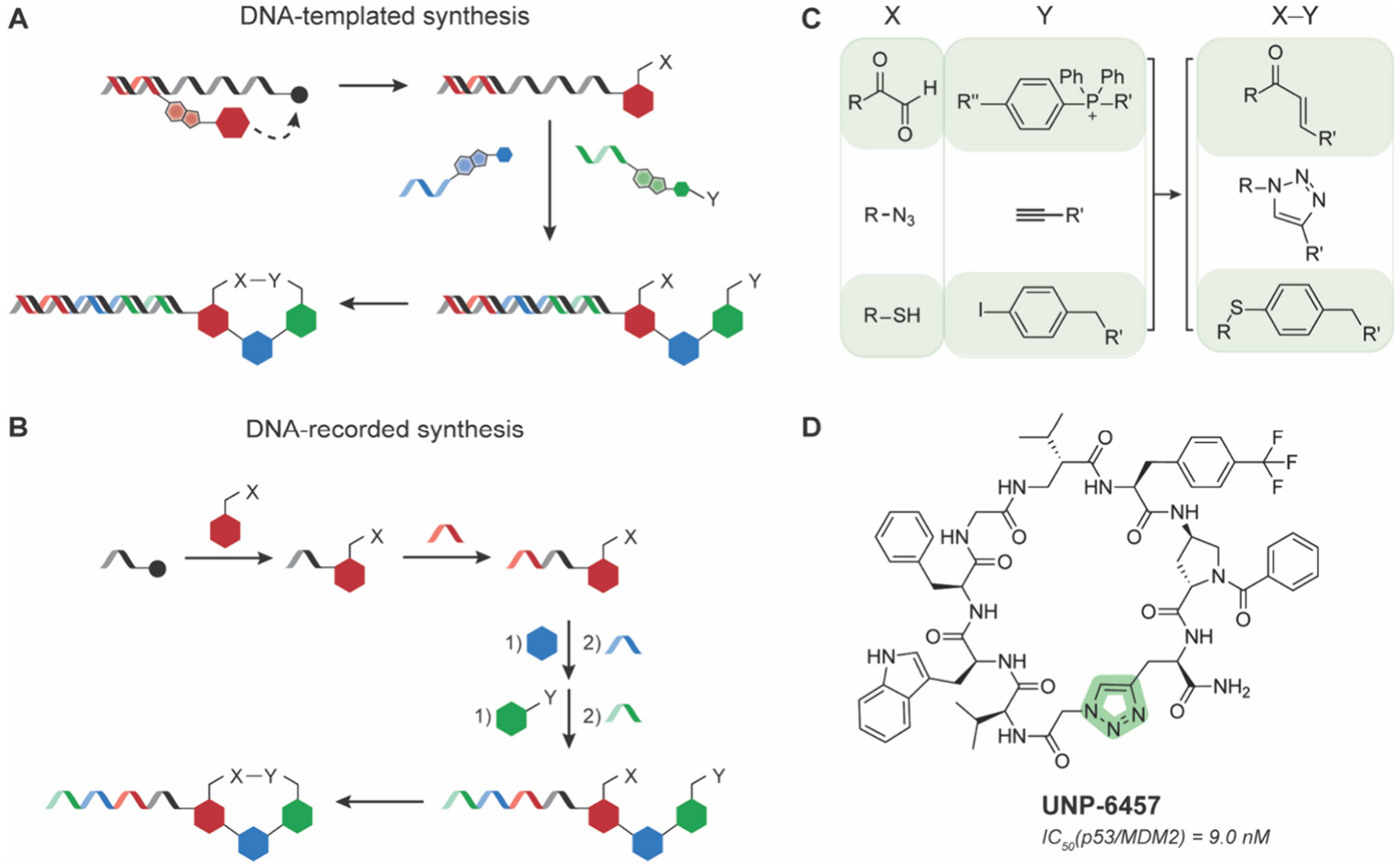

Figure 12.

DNA-programmable MCP libraries. Schematics of MCP library preparation by A) DNA-templated synthesis or B) DNA-recorded synthesis. C) Common DNA-compatible chemistries used to prepare MCP DNA-libraries. D) Chemical structure of UNP-6457.176

A conceptually similar and widely used approach for library synthesis and screening is DNA-encoded library (DEL) technology. First proposed in 1992171 as “DNA-recorded synthesis,”172,173 DEL libraries have been used extensively to record the synthesis sequence of complex and large MCP and small molecule libraries, now commonly reaching ~106–109 members. DEL synthesis uses small molecule or amino acid fragments ligated onto DNA oligonucleotides, which can be subjected to linear or parallel split-pool synthesis rounds for further fragment coupling, which is accompanied by DNA-ligation to encode the identity of each fragment in each round (Figure 12B). This process repeats multiple times until the library is synthesized and each compound has a unique DNA barcode for identification. Chen and co-workers generated a 106-member MCP DEL by performing a DNA-compatible palladium-catalyzed S-arylation reaction to react the thiol groups on cysteine residues with noncanonical aryl iodide side chains.174 As a proof-of-concept, they screened the library against p300, a transcriptional coactivator integral to oncoproteins function,175 and discovered two MCPs with single-digit μM inhibition potency. As expected, the linear precursors to these MCPs showed very poor (>100 μM) inhibition of p300, highlighting the necessary conformational constraints to achieve high affinity binding. DELs have also been used to target the transcription factor p53 and its interaction with MDM2. Su and co-workers synthesized an MCP DEL library of 109 tetrapeptides cyclized via azide–alkyne triazole formation to pan for molecules that disrupted the interaction.176 They discovered a hit compound, UNP-6457, that binds potently (low nanomolar Kd) to MDM2 and projected similar hydrophobic groups into the surface groove that interacts with the key p53 residues Phe19, Trp23, and Leu26, further confirming these necessary interactions for potent binding (Figure 12D). This compound, while not passively permeable in cells, could be a scaffold for improving biophysical and pharmacokinetic properties down the line.

DNA-programmable libraries have many potential advantages for MCP synthesis and screening. First, the miniaturization of synthesis and screening is enabled by the robust, enzyme mediated amplification of reaction products, but also places specific requirements and limitations on the compatible chemistries that can be deployed. Furthermore, because no purification of library members is needed, entire libraries can be generated, screened, retrieved and reintroduced to subsequent “evolution” rounds all in solution. Collectively, these attributes make DEL- and DTS-like approaches very attractive for MCP generation and application to undruggable targets. The requirement for DNA tags does hinder the use of DEL libraries against some undruggable targets, for example large families of TFs and chromatin regulatory proteins that have intrinsic affinity for DNA. Also, advances in the chemistries that can be used in DEL construction could continue to advance the likelihood that MCP hits are likely to contain other necessary attributes like cell penetration and metabolic stability.177-179 For additional reading on DTS and DELs, we refer readers to other in-depth reviews.180-182

2.2.5. Phage Display MCP Libraries.

First conceived by Smith in 1985, phage display is a powerful in vitro selection method that uses a bacteriophage, commonly M13 or fd, to express and display a library of peptides by fusing them to a surface protein, commonly pIII.183,184 This library is used to screen for binding to the POI typically through affinity purification of the phage particles. Iterative rounds of selection can be performed to isolate high affinity interactors that are identified by sequencing the phage DNA. This technology has been adapted to select for mono- and bicyclic peptides (Figure 13). The earliest examples of using phage display to discover MCP ligands date back to the early 1990s and was used to identify integrin-binding MCPs containing the RGD motif.185-188 In 1995, phage display was used to identify an MCP ligand for DNA matrix associated regions (MARs), the first example of a nonclassical drug target.189 Since then, phage display has been adapted to discover MCPs against various difficult-to-drug protein and nucleic acid targets including TEAD4,190 the Grb7-HER3 interaction,191 interactions between βB2-Crystallin fibrils,192 and the LEDGF/p75-IN interaction.193 For further reading on phage display or other related technologies capable of selecting peptide ligands, such as yeast display, bacterial display, or mammalian display, we point readers to other reviews.194,195

Figure 13.

Representative schematic of bicyclic phage display for selection of BCPs. Chemical structure of β-catenin/ICAT inhibitor BC1 is shown.196

An important set of intractable targets is selectively inhibiting the highly conserved B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) family members. These proteins that include the antiapoptotic members BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 regulate the intrinsic apoptosis pathway and are highly upregulated in cancer, thus represent important therapeutic targets.197-200 These proteins are very structurally similar and often perform the same role in the regulation of apoptotic cell death. Wu and co-workers used phage display to discover an MCP to target BCL-2.201 In their MCP design, they used 2-((alkylthio)(aryl)methylene) malononitrile (TAMM) conjugated with a chloroacetamide moiety as the scaffold molecule to cyclize via two included cysteine residues (Figure 14A).202 TAMM specifically reacts with the N-terminal cysteine residue to generate 2-aryl-4,5-dihydrothiazole (ADT) (Figure 14A). From this selection, they identified cp1, which selectively bound to BCL-2 19-fold more than BCL-XL (Figure 14 B,C).201 Interestingly, when the scaffold molecule TAMM is not present and the MCP is instead cyclized via a simple internal disulfide linkage, these MCPs had no binding affinity to BCL-2, suggesting the size and conformation of the ring plays a role in binding despite the exact same amino acid sequence or the scaffold molecule directly interacts with the protein. To look closer at the binding interactions of cp1 with BCL-2 over BCL-XL they solved a crystal structure and found that the hydrogen bond formed with BCL-2 at D111 and the backbone of cp1 at G6 is the critical differentiating factor (Figure 14C). In BCL-XL, A104, the closest residue to cp1 G6, is 7.2 Å away, precluding the formation of a hydrogen bond. Generating a BCL-2 D111A mutant led to significantly decreased cp1 binding. Another interesting finding was that cp1 binds to the BCL-2 surface without inducing conformational changes of the α3- or α4-helices, unlike small molecule or BH3-derived ligands. This unique binding mode allowed cp1 to interact with drugresistant BCL-2 mutants G101V and F104L. From here, a phage display library constructed from the cp1 sequence was prepared and used to discover MCPs specific for BCL-XL, which selected for cp3 that showed ~3-fold more selectivity for BCL-XL compared to BCL-2 (Figure 14D,E). Interestingly, they found that the residue at position 6 is key for affinity and selectivity, suggesting that highly similar surfaces require very few distinct interactions for selectivity. Unfortunately, poor membrane permeability even when tagged by the CPP Tat severely limited the MCPs efficacy in live cells, and significant efforts to produce clinically relevant compounds are needed.201 However, the ability to bind wild-type and drug-resistant mutant BCL-2 family proteins may provide starting points for additional ligand development for these challenging targets.

Figure 14.

Phage display selection of BCL-2 or BCL-XL-specific MCPs. A) Schematic of cyclization approach to generate MCPs with 2-((alkylthio)(aryl)methylene) malononitrile (TAMM) linker. B) Chemical structures of BCL-2 specific cp1 (left) and BCL-XL targeting cp3 (right). C) Crystal structure of cp1 bound to BCL-2. Key interacting H-bond between cp1(G6) and D114 of BCL-2 shown in yellow. PDB: 7Y90. D) Crystal structure of cp3 bound to BCL-XL. Key interacting residues between cp3(P6) and BCL-XL are shown. PDB: 7YAA.201

Another key family of undruggable targets to overcome are gain-of-function mutants of K-Ras. Sakamoto et al. used phage display and panned an MCP library to target K-Ras(G12D), the most common K-Ras mutation in human cancers.203 This screen identified a molecule, KRpep-2d, which contains a disulfide cyclization linkage and exhibited very high affinity (Kd = 51 nM) and more than 10-fold selectivity for K-Ras(G12D) over WT K-Ras, while the linear version of the peptide displayed no binding (Figure 15A). In cancer cell lines with the G12D mutant K-Ras, KRpep-2d suppressed cell proliferation and the Ras signaling cascade, suggesting the MCP may have some cell permeability and stability. This is unsurprising given that KRpep-2d contains 8 arginine residues in close proximity, which has previously been identified as a CPP motif.204,205 A 1.25 Å resolution crystal structure demonstrated that KR-pep2d recognizes a unique binding region not previously targeted by other small molecule inhibitors (Figure 15D).206 In a follow-up study by the same group, to increase the efficacy of KRpep-2d, they used SAR analysis to design a BCP that would have reduced molecular weight, not be susceptible to reducing conditions and remain protease-resistant.207 First, they started with the crystal structure of KRpep-2d binding to K-Ras(G12D) and introduced ncAA mutations at positions 6–14. They found that substituting linear aliphatic hydrophobic amino acids at positions 7 and 9, along with hydrophobic aromatic amino acids at positions 11 and 14 led to increased binding. In addition, (S)-2,3-diaminopropanoic acid (Dap) at position 10 forms a salt bridge with D69 of K-Ras(G12D), which increased binding approximately 5-fold. To eliminate bond cleavage under reductive conditions, they substituted the disulfide with an amide linkage between positions 5 and 15, which yielded a 0.6-fold weaker binding affinity. Combining these modifications led to KS-36, which bound to K-Ras(G12D) 30-fold stronger than KRpep-2d but had weaker than expected cell growth inhibition (Figure 15B). They identified the arginine-rich CPP region as the limiting factor due to its endocytosis-dependent uptake, so they eliminated the arginine residues and created BCPs by joining together positions 4 and 11, along with a head-to-tail amide linkage. By substituting in either Cys or d-Cys at positions 4 and 11, they determined that Cys4, d-Cys11, and a 1,4-diiodobutane linker led to the greatest cell uptake. Final optimization at positions 5 and 10 to introduce (S)-2-aminononanoic acid and a tryptophan residue, respectively, generated KS-58 (Figure 15C). Computational examination of KS-58’s mechanism for cell uptake revealed that it behaves like a chameleonic molecule, altering its polar surface area and internal hydrogen bond network depending on the solvent.208 KS-58 displayed improved K-Ras(G12D)-dependent cancer cell growth inhibition compared to KRpep-2d in both liver and lung cancer cells. This is likely because KS-58 inhibits the interactions of both SOS1 and B-Raf with K-Ras(G12D), whereas KRpep-2d only inhibits SOS1. In a PANC-1 mice xenograft model, administration of KS-58 led to a sizable decrease (~35%) of tumor growth. Co-administration with gemcitabine, a common chemotherapy drug, led to a larger decrease in tumor growth, showing similar efficacy in different xenograft models of colorectal and pancreatic cancer.209-211 However, KS-58 has low water solubility and requires frequent administration. To address both issues, KS-58 was made into a nanoformulation with a biocompatible surfactant, Cremophor EL, to generate a cell permeable nanoparticle.212 This formulation reduced the cancer cell growth rate in mice xenografts of both colorectal and pancreatic models. A separate team from Merck also looked to optimize KRpep-2d to improve its pharmacologic properties.213 Through SAR, they designed MCPs that are membrane-permeable, protease-resistant, and inhibit cell proliferation in K-Ras(G12D) cancer cells. However, these polyarginine-rich MCPs, which were included to improve cell uptake, induced mast cell degranulation (MCD) that in extreme cases can lead to patient death. They found that there was a strong correlation between the number of arginine residues and MCD, with MCPs containing greater than two arginine residues inducing MCD. Though these designs were not taken further, these studies demonstrated the potential to use MCP display approaches to identify high affinity and cell permeable ligands for a challenging and as-yet undrugged target like K-Ras (G12D).

Figure 15.

SAR optimization of KRpep-2d. Chemical structures and properties of KRpep-2d (A), KS-36 (B), and KS-58 (C). Cyclization linker is highlighted in green. D) Crystal structure of KRpep-2d bound to K-Ras (G12D). Key interacting residues are labeled. PDB: 5XCO.203,206,207

One of the biggest limitations of the first generation of phage display is the inability to incorporate ncAAs. Although ambercodon suppression can only incorporate the one ncAA, it can lead to a genetically encoded, intramolecular thioether linkage. A phage display library of MCPs that incorporated this design was used to discover MCPs with single-digit micromolar dissociation constant and in vitro IC50 values for HDAC8, a class I HDAC member.214 Macrocyclic organo-peptide hybrid phage display (MOrPH-PhD) developed by Owens et al. works in a similar vein, but incorporates O-(2-bromoethyl)-tyrosine as the ncAA.215 This new phage display technique was used to disrupt the KEAP1/NRF2 interaction, which is part of the stress response pathway.216,217 Owens et al. discovered an MCP that interacted strongly with KEAP1 (Kd = 40 nM) and the amino acid sequence closely matches the tip of the NRF2 β-hairpin that interacts with a natural cleft in KEAP1.215 Interestingly, though the most strongly binding sequences closely matched the NRF2 β-hairpin, there was one comparatively weak MCP (Kd = 2.8 μM) that contained a different sequence, suggesting that it interferes with the KEAP1/NRF2 interaction at a different location. Using a different variation of phage selection, Zheng et al. also generated an MCP against the KEAP1/NRF2 interaction.218 In this approach, two cysteine residues were introduced and cyclized with a special linker, 2-cyanobenzothiazole conjugated with an α-cyanoacrylamide. The N-terminal cysteine reacts specifically with the 2-cyanobenzothiazole while the other cysteine reacts with the α-cyanoacrylamide to generate the MCP, similar to the reaction with the TAMM scaffold.202 The highest affinity MCP (sub-μM Kd) also contained close sequence homology with the NRF2 β-hairpin as those selected by Owens et al. Interestingly, although using different linkers and ring sizes for generating MCPs, the top sequences between the two studies differed by only one residue within the β-hairpin sequence (DSETGE vs DIETGE), and obtained similar affinity. This suggests this sequence is likely highly specific for KEAP1 and can tolerate different substitutions, potentially to develop KEAP1-targeting MCPs with improved pharmacological properties.

To increase the diversity and versatility of phage display, a BCP selection strategy was developed by introducing three cysteines into the peptide sequence and adding 1,3,5-tris(bromomethyl)benzene (TBMB) to effectuate the production of BCPs via thioether bond formation.219 Using this strategy, BCPs have been selected against two different historically undruggable targets such as the β-catenin/ICAT interaction and Dcp2.196,220 β-catenin is a cell signaling molecule that is a central component of the WNT/β-catenin pathway, among other roles.221-223 Mutations in this pathway can lead to cancer, and β-catenin is seen as a key therapeutic target. Bertoldo et al. discovered a β-catenin-targeting BCP using phage display by testing three different scaffold molecules: TBMB, TATA (1,3,5-triacryloyl-1,3,5-triazinane), and N,N′,N”-(benzene-1,3,5-triyl)-tris(2-bromoacetamide) (TBAB). All three scaffold molecules yielded MCPs with single-digit micromolar dissociation constants; however, MCPs cyclized by TBMB and TBAB interfered with ICAT binding, which inactivates the WNT pathway by binding to β-catenin.196 In a separate study, Luo et al. selected a high affinity BCP (Kd = 116 nM) for Dcp2,220 which is an enzyme that removes the 5′ cap from a subset of mRNA molecules that is difficult to target due to an intrinsically disordered region (IDR) and intracellular delivery.224-226 This BCP engages the IDR of Dcp2 and inhibits its activity in cells. The BCP was also used to find novel mRNA sequences that are recognized by Dcp2 in the decapping process, demonstrating how MCPs can be used as chemical probes to elucidate novel biology surrounding undruggable targets.

Multiple different strategies have been reported to form BCPs and tricyclic peptides using phage display and are summarized in this recent excellent review.227 This strategy has yielded several bicyclic peptides now in clinical trials with Bicycle Therapeutics, such as BT8009 targeting nectin-4,228 BT5528 targeting the EphA2 receptor,229 BT1718 targeting the zinc metalloprotease MT1-MMP,230 and BCY12491 targeting the CD137 receptor.231 Even though none of these targets are classically undruggable, this selection strategy should be amenable to additional targets in the future. Further developments in incorporation of ncAAs may also yield MCPs with better pharmacological properties. Additional phage display technologies have been used to synthesize lanthipeptides, and these may be used to target classically undruggable proteins in the future.232 Finally, yeast selection, though used much less frequently than phage display, can also be used to find MCP inhibitors. First reported in 2012, Bowen et al. used yeast display to generate MCPs cyclized via lactam formation to target the WW-domain and the N-terminal region of YAP1, an intractable transcriptional coactivator in the Hippo signaling pathway.72,233,234

2.2.6. mRNA Display of MCPs.

Simultaneously designed by the Yanagawa lab and the Szostak lab in 1997, mRNA display involves transcribing a diverse DNA library into mRNAs before puromycin, an antibiotic that terminates translation in the ribosome, is conjugated at the 3′ end (Figure 16).235,236 Peptides translated from the mRNA are covalently attached to puromycin to terminate translation, leaving an mRNA-peptide conjugate that can be biopanned against various POIs. After identification of interacting peptides, RT-PCR is performed on the RNA to identify the peptide sequence. In a move away from endogenous expression systems, modern mRNA display methods largely rely on in vitro translation, an early example of which is the protein synthesis using recombinant elements (PURE) system developed in 2001 from purified aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, initiation factors, elongation factors, release factors, RNA polymerase and ribosomes to reconstitute translation.237 This approach can produce relatively large libraries of 1012-members. mRNA display has been used to select MCPs against numerous intractable targets and interactions such as p53/MDM2,238 SIRT2,239 SIRT7,240 TET1,241,242 and KDM7,243 among others.244-247

Figure 16.

General schematic of mRNA display for MCP selection.

An early example of using mRNA display to select MCPs against undruggable targets was performed by Millward et al. to target Gαi1·GDP.159 The initial MCP, cycGiBP, exhibited high target affinity but was prone to protease cleavage. To overcome this limitation, they developed scanning unnatural protease resistant (SUPR) mRNA display (Figure 17A). In SUPR, the library incorporates ncAAs such as N-methylalanine and is exposed to a protease cocktail prior to affinity purification, thus only selecting for protease-resistant interactors.161 This method was used to identify Gα SUPR (Figure 17B), which maintained similar binding affinity to cycGiBP but exhibited a > 35-fold increase in serum stability a half-life of 115 h, thus highlighting the versatility of in vitro display selection approaches.161

Figure 17.

Scanning unnatural protease resistant (SUPR) mRNA display. A) Schematic of SUPR mRNA display selection for protease-resistant MCP ligands. B) Chemical structure of Gαi1 inhibitor Gα SUPR.161

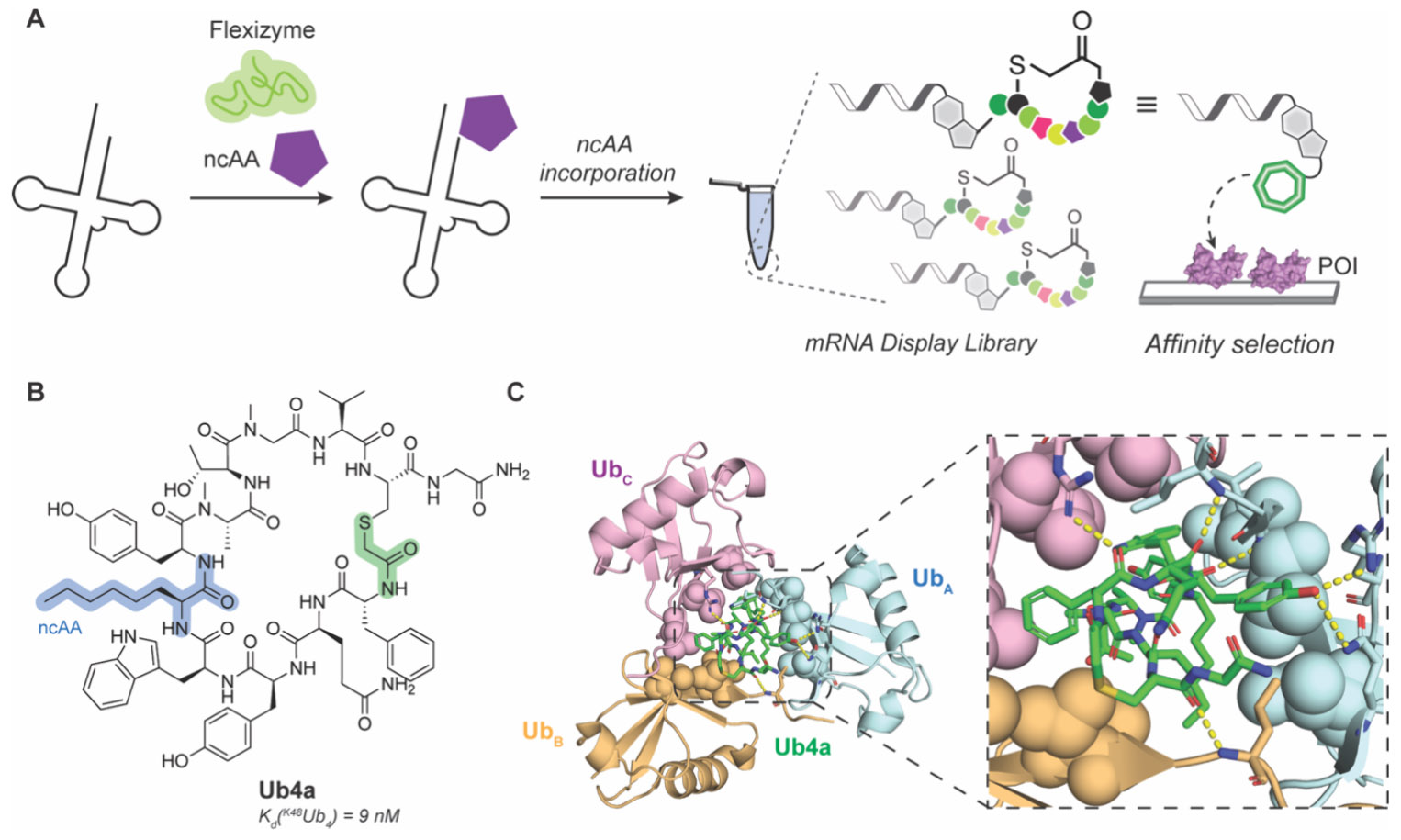

Building off of the PURE in vitro translation system, the Suga lab designed the random nonstandard peptide integrated discovery (RaPID) system, where mRNA display is combined with a flexible in vitro translation (FIT) system to screen large (>1012-member) MCP libraries.248,249 Along with the other recombinant elements, FIT involves flexizymes, which are tRNA-acylation ribozymes that can install ncAAs on to tRNAs that have been programmed to recognize different codons during translation (Figure 18A). The benefit of this system is that ncAAs can easily be incorporated into MCPs for testing via mRNA display, which expands the chemical diversity used to discover interactors. The most popular strategy for cyclization using RaPID incorporates a chloroacetamide moiety in the form of an N-chloroacetyl amino acid located at the N-terminus that reacts with an embedded cysteine to form a thioether bond.250 This strategy has been used to find MCPs against difficult-to-drug targets such as K-Ras-(G12D),251 α-Synuclein amyloid fibrils,252 and the retromer complex involved in endosomal membrane trafficking.253 For further reading on mRNA display or other similar display technologies, such as ribosome display, we point readers to other relevant reviews.254-256

Figure 18.

Random nonstandard peptide integrated discovery (RaPID). A) General schematic of RaPID incorporating flexizyme technology to include ncAAs during in vitro translation. B) Chemical structure of K48Ub4-selective MCP Ub4a generated by RaPID. Thioether linker used for head-to-tail cyclization is highlighted in green. C) Crystal structure of Ub4a bound to K48Ub3 displaying ring-like arrangement (left) and H-bonding network (right, insert, yellow dashes) for recognition. PDB: 8F1F.258,260

An interesting example of using RaPID to discover an MCP is for the recognition of poly ubiquitin (polyUb).257,258 Ubiquitination is a post-translational modification where a small protein (ubiquitin, Ub) is attached to mainly lysine side chains on cellular proteins to perform different functions including degradation by the proteasome.259 Interfering with the Ub-proteosome interaction is an attractive approach for cancer therapy. PolyUbs have diverse linkages that yield different conformations and diverse biological effects that are difficult to distinguish with small molecules like ubistatins. Using RaPID, Nawatha et al. specifically targeted K48-linked tetra-ubiquitin (K48Ub4), which is important for 26S proteosome recognition.257 They discovered a single MCP, Ub4ix, that was capable of distinguishing Ub linkage and chain size by targeting K48Ub4 with low nanomolar affinity. Ub4ix binding prevented USP2, a nonspecific deubiquitinase, from cleaving more than one Ub from the target, resulting in blocked deubiquitination of proteins like p53 and p27 that then accumulated in HeLa cells. To increase cell permeability and protease resistance, the same group performed another RaPID selection and incorporated ncAAs ClAc-d-Phe, N-methyl-Gly, N-methyl-Ala, N-methyl-Phe, d-Ala, d-Phe, and Aoc to replace Met, Glu, Asp, and Arg.258 This selection produced a cell permeable MCP, Ub4a, that bound to K48Ub4 with high affinity (Kd = 9 nM; Figure 18B). Interestingly, structural NMR analysis of Ub4a bound to K48Ub4 suggested that there is minimal interaction with the distal ubiquitin and that Ub4a is actually specific for K48Ub3, which may explain the mechanism of only allowing a single Ub cleavage similar to Ub4ix. This was later confirmed by a solved crystal structure showing tri-Ub wraps around Ub4a in a ring-like arrangement driven mainly by H-bonding and hydrophobic interactions (Figure 18C).260 Significantly, Ub4a demonstrated anticancer activity in a mouse model of CAG myeloma by reducing tumor burden in a manner similar to the approved 26S proteasome inhibitor medication bortezomib.258

RaPID can also be used to explore physicochemical properties of MCPs and the effects on target binding, as ring size and residue identity play important roles in target recognition. For example, Lin et al. used two separate RaPID libraries and compared 7–9 residue MCPs to 10–14 residue MCPs targeting the stimulator of interferon genes (STING) adaptor protein.261 These libraries were very diverse with 25 potential amino acids that could be incorporated. Surprisingly, they found that only 9-mer MCPs with 8-residue ring size exhibited measurable affinity using surface plasmon resonance (SPR). This is potentially due to the more thorough sampling of sequence space with fewer randomized positions or more likely the smaller loss of conformational entropy for shorter peptides to bind the target. Another key question is whether RaPID explores enough sequence space to select for the most efficient interactors. Suga and colleagues used RaPID to efficiently perform deep mutational scanning and explore the effects of ncAA incorporation for CP2, an MCP previously selected via RaPID to target the histone demethylase KDM4A-C.262-264 Including ncAAs changed properties such as charge, steric bulk, N-methylation, or number of hydrogen bonding groups. Interestingly, they found few mutations resulted in increased binding affinity, while many substitutions had little effect on binding energy. Although likely to be target-specific, many MCPs can potentially be screened and optimized through numerous modifications to gain desirable properties.

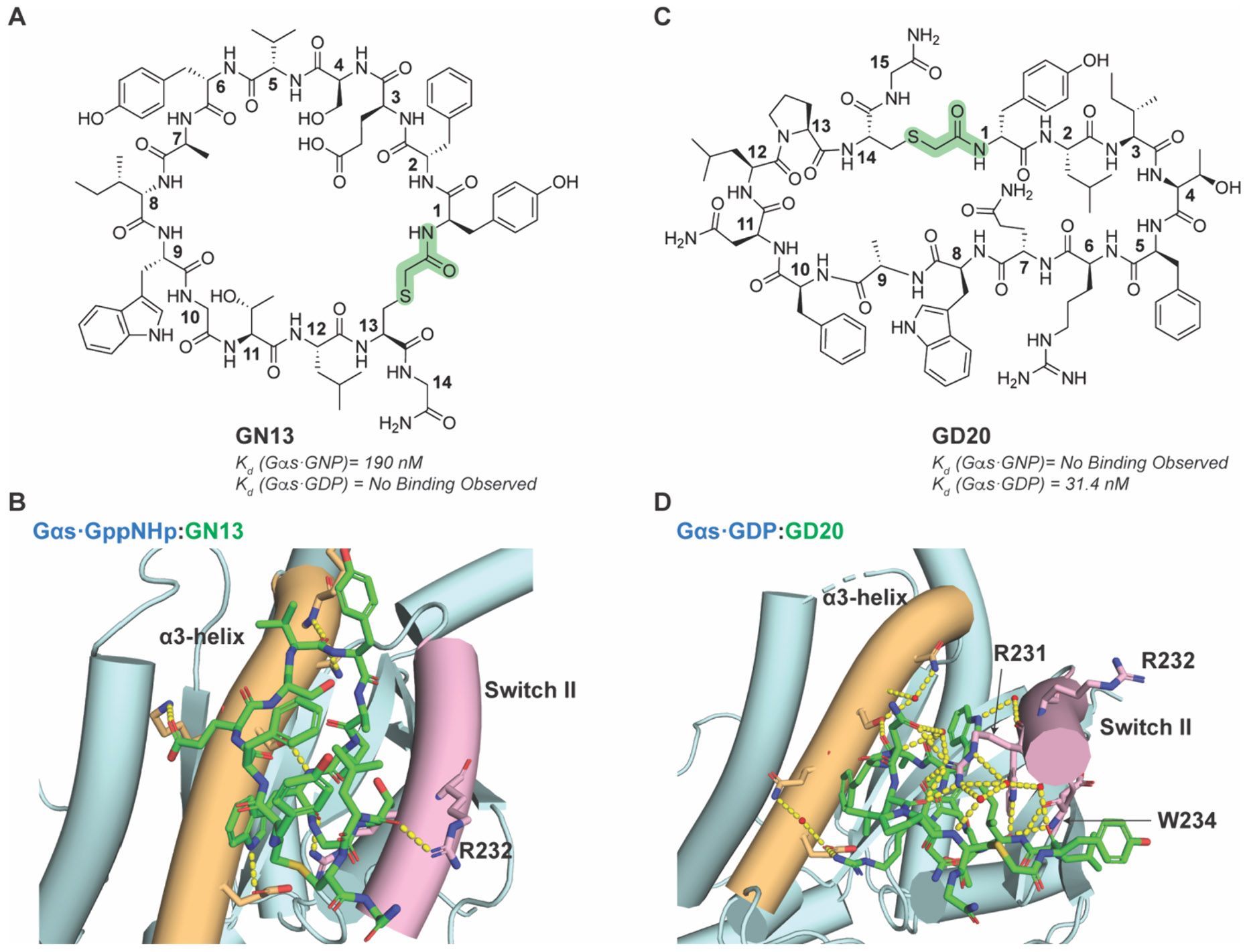

While small molecules have difficulty distinguishing between different conformational states, MCPs are more likely to behave as state-specific inhibitors. Dai, Hu, and Gao et al. showed this by using RaPID to select for MCPs that distinguish between GTP- or GDP-bound Gαs.265 To promote selectivity, MCP libraries were exposed to negative selection for the undesired alternate states. Using this approach, they developed MCPs that could target only the Gαs·GTP state (MCP termed GN13) or Gαs·GDP state (MCP termed GD20), which were determined to be at least 100-fold selective for their respective target state (Figure 19A and C). The MCPs bind to the Gαs switch II-α3 pocket, which adopts a different conformation dependent on nucleotide to discriminate between the different states. Analysis of crystal structures showed that GN13 interacts with active state Gαs through necessary and complex hydrogen-bonding network and hydrophobic interactions, whereas an expected steric clash of Gαs R232 in inactive-state switch II domain likely explains the conformationally selectivity (Figure 19B). Conversely, GD20 recognizes the inactive state Gαs through important electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic interactions, and likely sterically clashes with R231, R232, and W234 in the active state switch II domain (Figure 19D). In addition, both GN13 and GD20 demonstrated excellent specificity for Gαs over other structurally similar G-protein members regardless of state. Additional modifications to both MCPs improved cell permeability and bioactivity, resulting in compounds capable of in cellulo disruption of Gαs interactions and activity, demonstrating the power and versatility of RaPID and generated MCPs.265

Figure 19.

Discrimination of active and inactive Gαs GTPase by RaPID-selected MCP. A) Chemical structure of active Gαs-selective GN13. B) Crystal structure of GN13 bound to active-state Gαs. H-bond between GN13 and R232 is highlighted as yellow dashed line. PDB: 7BPH. C) Chemical structure of inactive Gαs-selective GD20. D) Crystal structure of GD20 bound to inactive-state Gαs. Key interactions between GD20 and R231 and W234 of Gαs are highlighted. PDB: 7E5E. Thioether cyclization linkage highlighted in green in chemical structures.265

The team at Chugai Pharmaceuticals who identified the previously described desirable MCP properties for drug-like molecules used their guidelines to generate an mRNA display library to select for inhibitors to K-Ras.65,266 Incorporating a high number ncAAs, particularly N-alkylated amino acids, and native chemical ligation for cyclization resulted in a library that could satisfy the criteria for drug-like MCPs. They discovered an 11-residue MCP, AP8784, that bound at the interface of KRas and SOS1 to potently inhibit the interaction with an IC50 of 54 nM but showed no activity in live cells (Figure 20). Following their guidelines and a crystal structure to improve the physicochemical properties of AP8784, they embarked on a comprehensive SAR campaign.266 The crystal structure revealed AP8784 interacted with the Switch II pocket on GDP-K-Ras(G12D), which identified positions 8 and 11 as likely to be amenable to modification without disrupting binding, while positions 2, 5, 7, and 10 made direct surface contacts. Positions 7 and 10 specifically occupied the SII-hole, and likely could be modified to enhance bioactivity. To summarize the outcome of the SAR analysis, positions 7 and 10 were optimized from 3-chloro-phenylalanine at position 7 and N-methyl-valine at position 10 to homophenylalanine(4-CF3,3,5-F2) and N-methyl-cyclopentyl for positions 7 and 10, respectively to improve bioactivity. Further improvement to cell permeability was achieved by altering positions 8 and 9 from tryptophan and N-methyl-phenylalanine to a proline and cycloleucine, respectively. Rigidity was increased by modifying positions 3 and 4 from N-methyl-glycine to N-methyl-alanine at position 3 and N-ethyl-azetidine-2-carboxylic acid at position 4. Finally, replacing position 1 to N-methyl-leucine, position 5 with an N-ethyl-4-methyl-phenylalanine, and N-alkylation of position 11 resulted in lead compound LUNA18 (Figure 20). This lead MCP contained desirable drug-like properties such as a high Clog P, and membrane permeability via Caco-2 assay without the need to significantly alter the scaffold. LUNA18 displayed a > 25-fold improvement to potency compared to AP8784 and exhibited low picomolar affinity for GDP-K-Ras-WT and G12C, G12D, and G12V mutants. LUNA18 selectively reduced proliferation in K-Ras-G12X-dependent cancer cell lines and showed dose-dependent antitumor activity after oral administration in mice.65 LUNA18 is currently undergoing a phase I clinical trial.

Figure 20.

SAR optimization of pan-K-Ras targeting MCPs. A) Chemical structure of AP8784. B) Chemical structure of LUNA18 after SAR optimization. Amide cyclization linkage is highlighted in green.266

mRNA display technologies are very powerful tools for selecting MCPs against various targets that have the potential to enter and succeed in clinical trials, key examples being FDA-approved zilucoplan267,268 and more recently orally available PCSK9 inhibitor MK-0616 currently in phase III.269-273 These examples and LUNA18 demonstrate how encodable designer peptides selected from large libraries can undergo synthetic optimization to produce viable clinical candidates. Including the ability of RaPID to incorporate multiple ncAAs during selection and SUPR to select for metabolically stable ligands, variations of mRNA display can be combined to generate MCPs with ideal pharmacological properties. Improvements to these technologies harness the power of computation to categorize the top hits into different binding modes on the POI, providing different starting points for further optimization.274,275 Given the relatively large library size, these technologies may generate more pharmacologically viable lead MCPs that function in cells or animals with less required modification and optimization.

2.2.7. Split Intein Circular Ligation of Peptides and Proteins.