Abstract

We developed and tested a simple method for fluorescence labeling and interaction analysis of proteins based on a highly efficient in vitro translation system combined with high-throughput technologies such as microarrays and fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy (FCCS). By use of puromycin analogs linked to various fluorophores through a deoxycytidylic acid linker, a single fluorophore can be efficiently incorporated into a protein at the carboxyl terminus during in vitro translation. We confirmed that the resulting fluorescently labeled proteins are useful for probing protein–protein and protein–DNA interactions by means of pulldown assay, DNA microarrays, and FCCS in model experiments. These fluorescence assay systems can be easily extended to highly parallel analysis of protein interactions in studies of functional genomics.

[Online supplementary material available at http://www.genome.org.]

The draft sequences of the human genome appear to contain about 30,000–40,000 protein-coding genes (Lander et al. 2001; Venter et al. 2001). For most of them, full-length cDNAs may soon be available (Strausberg et al. 1999; Wiemann et al. 2001), and thus the large-scale analysis of protein interactions (i.e., protein–protein, protein–DNA, and protein–substrate interactions) will become possible. In recent years, fluorescence assay technologies have played an increasing role in the high-throughput analysis of protein interactions. In microarray technologies, for example, >10,000 DNAs or proteins can be arrayed on a single slide glass and probed with fluorescently labeled proteins for the large-scale analysis of protein–DNA and protein–protein interactions (Schena et al. 1995; Bulyk et al. 1999; MacBeath and Schreiber 2000; Haab et al. 2001; Zhu et al. 2001). In contrast to the microarray analyses that detect protein interactions on a solid phase, fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy (FCCS) made it possible to monitor interactions of fluorescent molecules in liquid solution (Schwille et al. 1997; Kettling et al. 1998; Koltermann et al. 1998; Bieschke et al. 2000; Rippe 2000). In the FCCS analysis, the sample volume is quite small (∼1 fL) and analysis rates of 10,000 samples per day can potentially be achieved (Koltermann et al. 1998). These miniaturized assay systems based on fluorescence are expected to facilitate the in vitro analysis of protein interactions on a genome-wide level.

One of the most crucial and laborious steps in such fluorescence assay systems is obtaining the protein samples labeled with fluorescent dyes. Most frequently, the proteins have been expressed in living cells, purified to homogeneity, and then fluorescently labeled by chemical modification of the amino, sulfhydryl, and hydroxyl groups of side chains of amino acids such as lysine, cysteine, serine, and threonine. Applying these procedures to thousands of proteins is a daunting task and also has several other demerits. Bacterial expression of eukaryotic genes can produce only those proteins that do not affect cellular metabolism and often fails to yield correctly folded proteins. Moreover, chemical modifications of amino acid side chains often affect the enzymatic or binding activities of the proteins. To overcome these limitations, a simple method for the fluorescence labeling of proteins has been developed, in which the target cDNA product is synthesized in vitro and its carboxyl terminus is simultaneously labeled with a puromycin–fluorophore conjugate on the ribosome (Nemoto et al. 1999; Miyamoto-Sato et al. 2000). This method can be performed in one step (the expression and labeling steps are synchronized and a purification step before labeling is unnecessary) and is thus suitable for the large-scale analysis of proteins. By use of a highly efficient cell-free protein synthesis system (Madin et al. 2000), large amounts of active proteins, high-molecular-weight proteins, and even harmful proteins are expected to be obtainable in labeled form with this method. Furthermore, carboxy-terminal labeling would be much less perturbative for the protein function than chemical modification of internal residues, because the protein terminal regions have large flexibility in general and tend to be located far from the active site (Thornton and Sibanda 1983).

Here we describe the establishment of a fluorescence assay system for in vitro analysis of protein interactions by combining a simple protein labeling method, an efficient cell-free protein synthesis system, and miniaturized assay systems such as microarray and FCCS technologies. We have used classical oncogenes, Fos and Jun, as model proteins, because they are known to form a heterodimer that specifically binds to a DNA sequence (Angel and Karin 1991) and thus they can be used to examine both protein–protein and protein–DNA interactions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

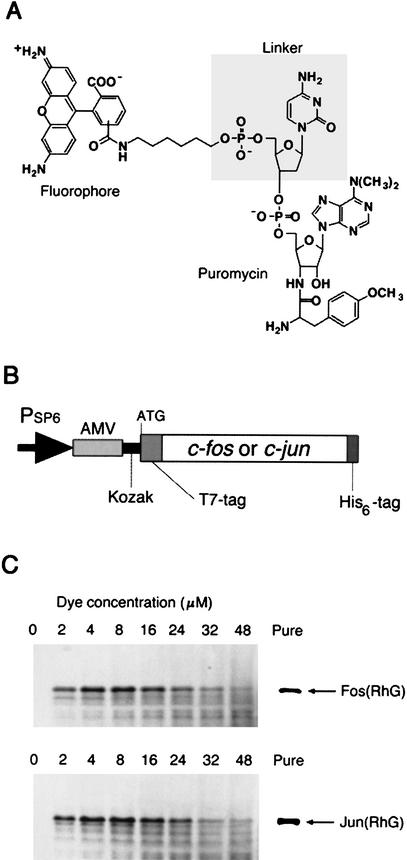

Fluorescence Labeling with Puromycin Analogs

Puromycin is an antibiotic that mimics the aminoacyl end of tRNA and acts as a translation inhibitor by being linked to the nascent peptide by the peptidyl transferase activity of the ribosome. Recently, it has been shown that puromycin and its derivatives at low concentrations can bind to the carboxyl terminus of full-length proteins (Miyamoto-Sato et al. 2000) and that a fluorescein–puromycin conjugate was successfully used for the fluorescein labeling of proteins (Nemoto et al. 1999). To confirm the general utility of this labeling method, we chemically synthesized various puromycin analogs containing a different fluorophore such as fluorescein, rhodamine green (RhG), tetramethyl-rhodamine (TAMRA), Cy3, or Cy5. Further, one or two (deoxy-)cytidylic acid(s) (i.e., dC, dCdC, rC, or rCrC) was inserted between fluorophore and puromycin as a linker (Fig. 1A) to enhance the incorporation of puromycin analogs into proteins by mimicking the CCA sequence at the 3′-end of tRNA. These puromycin analogs were added to the wheat germ in vitro translation system (Madin et al. 2000) supplemented with a template RNA transcribed from a part of the c-fos (118–211 amino acids) or c-jun (216–318 amino acids) gene encoding DNA-binding and leucine-zipper regions (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Fluorescence labeling of proteins. (A) The structure of fluorescent puromycin. A fluorophore (fluorescein, RhG, TAMRA, Cy3, or Cy5) was chemically joined to puromycin through a linker (dC, dCdC, rC, rCrC, or none). (B) Template DNA containing SP6 promoter (Morishita et al. 1999), AMV (alfalfa mosaic virus) leader sequence (Jobling and Gehrke 1987), Kozak sequence (Kozak 1986), and c-fos (118–211 amino acids) or c-jun (216–318 amino acids) gene with T7-tag (11 amino acids, MASMTGGQQMG) and His6-tag sequences. (C) RhG-labeled Fos and Jun proteins. In vitro translation reaction was carried out in the presence of the template RNA and 0–48 μM of RhG–dC–puromycin. The products were analyzed by 16.5% Tricine-SDS-PAGE with an imaging analyzer. The labeled proteins with His6-tag were purified by affinity chromatography (Pure).

The Fos and Jun proteins were labeled with all the fluorophores. A typical result for RhG-dC-puromycin is shown in Figure 1C. The intensities of the fluorescent bands depended on the concentration of fluorescent puromycin and the labeling efficiencies at the peak concentration ranged from 10% to 30%. With increasing dye concentration, extra bands of lower molecular weight than that of the target band appeared. These bands might originate from the incorporation of puromycin analogs into the nascent polypeptides as they could be removed by affinity purification of translated products with carboxy-terminal His6-tag sequences (Fig. 1C, Pure), but not with the amino-terminal His6-tag (data not shown).

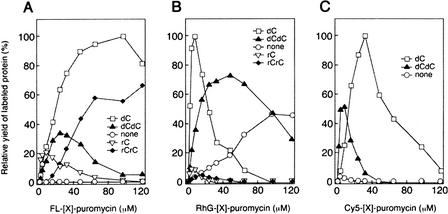

Figure 2 shows the relative yields of Jun proteins labeled with fluorescein, RhG, and Cy5. These values were highly sensitive to the linker structure. For example, the maximum yields of proteins labeled with fluorescein–, RhG–, and Cy5–dC–puromycin were 140–, 2–, and 25-fold higher than those of proteins labeled with fluorescein–, RhG–, and Cy5–puromycin, respectively. For all the fluorophores, use of the dC linker resulted in the highest yields of labeled Jun proteins, and thus fluorophore–dC–puromycin conjugates were used in further experiments. By use of these fluorescent reagents, >10 proteins derived from human, mouse, and other organisms could also be labeled with various fluorophores (N. Doi, H. Takashima, R. Oyama, E. Miyamoto-Sato, and H. Yanagawa, unpubl.).

Figure 2.

Effect of the linker structure on the yields of labeled Jun proteins. Fluorescein (A), RhG (B), or Cy5 (C) linked to puromycin through various linkers was added to the in vitro translation reaction mixture at various dye concentrations. The products were analyzed by 16.5% Tricine-SDS-PAGE and quantified with an imaging analyzer.

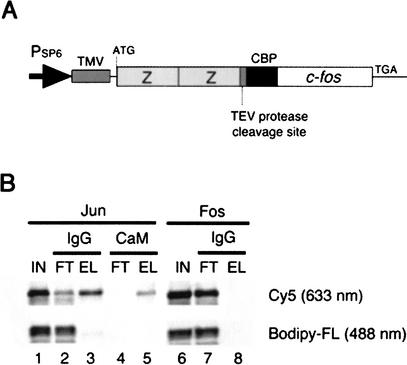

Detecting Protein–Protein Interactions by Pulldown Assay

As the bait protein, Fos was fused with the IgG-binding domain of protein A (ZZ domain) and calmodulin-binding peptide (CBP) for a tandem affinity purification method (Rigaut et al. 1999; Fig. 3A). The prey Jun and Fos (as a negative control) were carboxy-terminally labeled with Cy5–dC–puromycin as described above. Further, as a control with another labeling method, Jun and Fos proteins labeled with Bodipy-FL at their lysine residues were also prepared by means of an in vitro translation reaction containing fluorescently labeled lysine tRNA. As shown in Figure 3B, the carboxy-terminally labeled Jun (Cy5) bound to ZZ–CBP–Fos and was purified by tandem affinity beads (lanes 3 and 5, top), whereas the internal lysine-labeled Jun (Bodipy-FL) did not bind to the bait Fos (lanes 3 and 5, bottom). This is a typical example of the advantage of the carboxy-terminal labeling of proteins.

Figure 3.

Pulldown assay. (A) A gene encoding the bait Fos (118–211 amino acids) fused with the ZZ domain and the CBP tag. TMV, tobacco mosaic virus leader sequence (Gallie et al. 1988). (B) Tandem affinity purification. The in vitro-translated Jun (lanes 1–5) and Fos (lanes 6–8) proteins labeled with Cy5 (excited at 633 nm) at the carboxyl terminus and those with Bodipy-FL (488 nm) at the internal lysine residues were mixed with the bait Fos (lanes 1–6; IN, input) and captured on IgG beads (lanes 2 and 7; FT, flowthrough), washed, and eluted by TEV protease cleavage (lanes 3 and 8). The eluate was then bound to calmodulin (CaM) beads (lane 4, FT), which were washed, and eluted with EGTA (lane 5). The carboxy-terminally labeled Jun only bound to the bait Fos (Cy5, lanes 3 and 5).

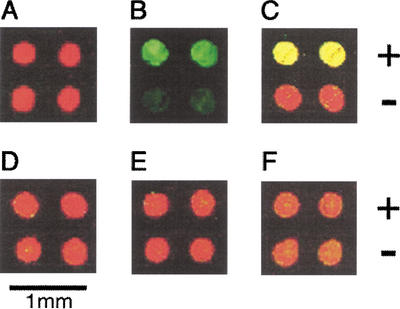

Detecting Protein–DNA Interactions with DNA Microarrays

DNA microarrays have been used widely for monitoring gene expression patterns (Schena et al. 1995) but also can potentially be used for studying sequence-specific protein–DNA interactions (Bulyk et al. 1999; Iyer et al. 2001). We have tested this application by using as probes Fos/Jun proteins carboxy-terminally labeled with TAMRA-conjugated puromycin. The Fos–Jun heterodimer is known to bind to DNA containing a TGA(G/C)TCA consensus sequence (Angel and Karin 1991). We arrayed Cy5-labeled DNA containing or not containing the target sequence on poly-L-lysine-coated slides using commercially available arrayers (Fig. 4A). The slides were then probed with the TAMRA-labeled proteins, washed, and scanned with a fluorescence scanner. As anticipated, the heterodimer of TAMRA-labeled Jun with nonlabeled Fos bound to the DNA in the sequence-specific manner (Fig. 4B,C), whereas no binding was observed in control experiments (Fig. 4D–F). In a complementary experiment, the sequence-specific binding of the complex of TAMRA-labeled Fos with unlabeled Jun to the DNA was also observed (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Detecting protein–DNA interactions. (A) Two types of DNA labeled with Cy5 (650/670 nm) were spotted on a glass slide (represented as false-colored red), one containing a Fos–Jun bound sequence (+) and the other not (−). (B) The sequence-specific binding of the complex of the Jun labeled with TAMRA (542/568 nm) and unlabeled Fos to the DNA (+) was detected as false-colored green spots. (C) The same result as in B is represented as a superposition of red and green color. (D–F) As negative controls, the solution of TAMRA-labeled Jun (D) without Fos, (E) with unlabeled Fos, and an excess of competitive DNA, and (F) with unlabeled Jun were probed, and no binding was observed (shown by the superposition of red and green color).

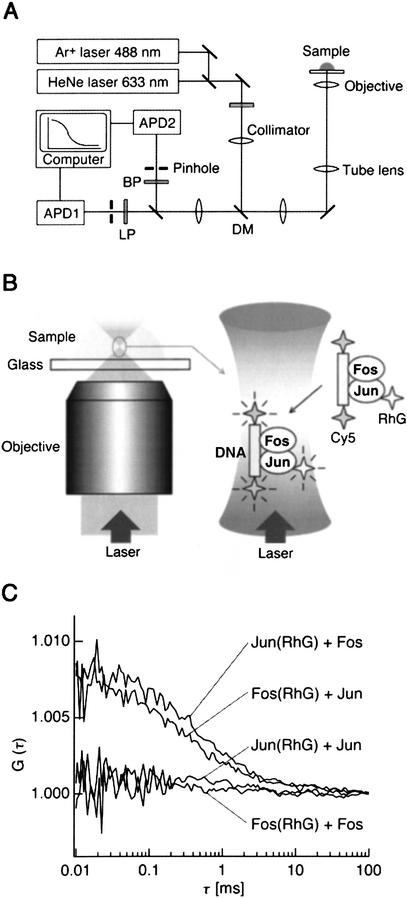

Kinetic Analysis of Protein Interactions with FCCS

Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) is a new, highly sensitive method that can, in principle, detect the motion or fluctuation of a single fluorescent molecule in a solution volume of <1 fL (Eigen and Rigler 1994; Rigler 1995; Maiti et al. 1997). By autocorrelation function analysis of the fluorescence fluctuations, the diffusion time and the molecular weight of the fluorescent molecule can be determined. Although FCS was invented >25 years ago, it has been applied only recently in the field of biology; for example, in vitro studies of DNA hybridization (Schwille et al. 1997), DNA amplification (Kinjo 1998), protein–protein interaction (Pack et al. 2000), protein aggregation (Pitschke et al. 1998; Bieschke et al. 2000), and protein dynamics (Haupts et al. 1998), and in vivo studies of protein transport (Terada et al. 2000) and flagellum rotation (Cluzel et al. 2000). The detection of protein interactions with single-color FCS requires drastic changes of the size or shape of the protein complex (Pack et al. 2000). In contrast, the FCCS (dual-color FCS) analysis is independent of the size and shape of the fluorescent molecule, but rather is based on the identification of fluctuations that occur simultaneously in two detected channels (Schwille et al. 1997). Hence, this method makes it possible to monitor whether two molecules labeled with different fluorophores bind or not, with higher sensitivity, specificity, and speed than those of single-color FCS.

Here we have shown the quantitative analysis of protein–DNA interactions with FCCS (Fig. 5). The Fos and Jun proteins were labeled with RhG–dC–puromycin at the carboxyl terminus, and the target DNA was labeled with Cy5 at the 5′-ends. As shown in Figure 5C, only the Fos–Jun–DNA complex molecule carrying both RhG and Cy5 was observed in the cross-correlation and quantified, but not the Fos–Fos and Jun–Jun pairs. The apparent dissociation constant Kd for the binding of the Fos–Jun heterodimer to DNA can be obtained from a single FCCS measurement (Földes-Papp and Kinjo 2001; Jankowski and Janka 2001): The Kd value was found to be 30 nM (see supplemental data on the web site), which is consistent with a value of 50 nM independently derived from the results of gel shift assay (John et al. 1996).

Figure 5.

FCCS setup and measured cross-correlation curves. (A) The beampath of the ConfoCor 2 FCCS setup. A sample droplet is excited with two-color laser beams through the objective lens. The emission light is divided and detected by two avalanche photodiodes (APD1 and APD2), and the signals are analyzed by a computer with a correlator. DM, dichroic mirror 488/633 nm; BP, bandpass filter 530–600 nm; LP, longpass filter 650 nm. (B) Schematic diagram of FCCS detection apparatus. (Left) Laser beams are focused in the sample droplet on the coverglass. (Right) In the superimposed confocal volume, RhG-labeled proteins and Cy5-labeled DNA are simultaneously excited. (C) Typical cross-correlation curves obtained from samples of DNA–protein complexes. Fos–Jun heterodimers were bound to Cy5-labeled DNA (top curves), whereas no or little formation of the Fos–Fos–DNA or Jun–Jun–DNA complexes was observed (bottom curves).

In summary, we have established a simple method for fluorescence labeling of proteins and confirmed that the resulting fluorescently labeled proteins are useful for probing protein–protein and protein–DNA interactions by means of pulldown assay, DNA microarrays, and FCCS measurements. To our knowledge, this work is the first to describe the successful detection of protein–DNA interactions with FCCS and DNA microarray by using fluorescently labeled proteins. These assay systems should also be applicable to the detection of protein–protein interactions. Our labeling method is so simple that it can easily be extended to the large-scale analysis of proteins, and, hence, we believe that these technologies will contribute greatly to studies of genomic function.

METHODS

Synthesis of Fluorescent Puromycin Derivatives

Protected nucleoside phosphoramidites, fluorophore phosphoramidites, 5′-amino-modifier C6 phosphoramidite, and Poly-pak II cartridges were purchased from Glen Research. Rhodamine green succinimidyl ester (RhG-OSu) was purchased from Molecular Probes. N-Fluorenylmethoxycarbonylpuromycin and N-t-butyloxycarbonylpuromycin attached to controlled pore glass supports [Puromycin(Fmoc)-CPG and Puromycin(Boc)-CPG] were synthesized according to the published procedure (Ikeda et al. 1998). Fluorescein–[X]–puromycin, Cy5–[X]–puromycin and TAMRA–dC–puromycin were synthesized from Puromycin(Fmoc)-CPG according to the standard solid-phase phosphoramidite method (Ikeda et al. 1998). After deprotection according to the recommended protocol (Glen Research) for nucleosides and fluorophores, fluorescent puromycin analogs were purified by reverse-phase HPLC on a YMC-Pack ODS-A column (2 cm × 30 cm, YMC, Kyoto, Japan) with 0.1 M triethylammonium acetate (pH 7.0) as solvent A and acetonitrile as solvent B at a flow rate of 10 mL/min. A linear gradient of 10%–60% solvent B over 30 min was used for elution. The 5′-amino-modifier C6–[X]–puromycin(Boc) was synthesized from Puromycin(Boc)-CPG according to the standard solid-phase phosphoramidite method. After deprotection according to the recommended protocol for each nucleoside, the puromycin analogs were purified by reverse-phase HPLC under the elution condition described above. The 5′-amino-modifier C6–[X]–puromycin(Boc) was then reacted with RhG-OSu (5 equivalent) in 0.1 M NaHCO3 (pH 8.3)/dimethylformamide (1:1, vol/vol) at 25°C for 2 h. Desalting by the Poly-pak II cartridge, acid treatment (60% CF3COOH-H2O, 25°C, 30 min), and following HPLC purification under the elution condition described above gave RhG-[X]-puromycin. The structures of fluorescent puromycin analogs were confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Lasermat 2000, Thermo Finnigan). A list of structures (Supplementary Fig. 1), and UV and Mass spectral data (Supplementary Table 1) of fluorescent puromycin analogs were provided as supplemental data on the web site.

Fluorescence Labeling of Proteins

The template DNAs encoding c-Fos (118–211 amino acids) and c-Jun (216–318 amino acids) genes (Fig. 1B) were prepared by PCR with Ex Taq DNA polymerase (Takara Shuzo) and purified with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN). Detailed methods and a list of the primer sequences (Supplementary Table 2) are provided as supplemental data on the web site. RNAs were transcribed from the DNAs by use of a RiboMAX large-scale RNA production system (Promega) and purified by using an RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN). In vitro translation was performed in a highly efficient cell-free protein synthesis system from wheat germ extract (Madin et al. 2000) supplemented with fluorescent puromycin described above or FluoroTect GreenLys tRNA (Promega) at 25°C for 2 h. The resulting fluorescently labeled proteins were subjected to 16.5% Tricine-SDS–PAGE (Schägger and von Jagow 1987), and the results were analyzed with a Molecular Imager FX (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The labeling efficiency was calculated from the values of total proteins estimated with T7-tag antibody (Novagen) and fluorescence labeled proteins determined with FCS measurements (see below) after affinity purification.

Pulldown Assay

A tandem affinity purification method (Rigaut et al. 1999) was used. A c-fos gene fused with a tandem affinity tag, that is, the ZZ domain from pEZZ18 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and synthesized CBP gene, was constructed by PCR (see supplemental data on the web site). The ZZ–CBP–Fos fusion protein was synthesized by use of the wheat cell-free dialysis system (Madin et al. 2000) and incubated with the fluorescently labeled Jun or Fos (negative control) in a buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% NP-40) at 37°C for 30 min. According to the protocol described previously (Rigaut et al. 1999), the ZZ–CBP–Fos–Jun complex was captured on IgG Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), digested with TEV protease (Invitrogen), and captured on calmodulin beads (Stratagene). Each of the flowthrough and eluate fractions was analyzed by Tricine-SDS-PAGE with a Molecular Imager FX.

DNA Microarrays

The 1.9-kb fragments of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) were prepared by PCR with Cy5-labeled primers from pET20b (Novagen) or from its plasmid derivative, pET20-FJ, containing a Fos/Jun bound sequence, TGA(G/C)TCA, in a XhoI site of pET20b. Similarly, nonlabeled competitive dsDNA (0.3 kb) with the target sequence was prepared. The PCR products were purified with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN) and the Cy5-labeled DNAs (0.4 mg/mL) were printed on commercially available poly-L-lysine-coated glass slides (DNA-Ready Type II slides, Clontech) with a MicroGrid arrayer (BioRobotics). The slides were subjected to heating, UV cross-linking, and blocking according to the recommended protocols (Clontech) and then treated with a PBS solution containing 3% skim milk and 0.02% sodium azide at 4°C overnight and washed twice with PBS. As the fluorescent probe, in vitro translation reaction solution containing TAMRA-labeled Fos or Jun (10 nM) and unlabeled Fos or Jun (1 μM) was taken up in a buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 20% glycerol, 0.01% NP-40, 50 mM NaCl, and 10 μg/mL poly(dIdC)] and applied to the DNA-arrayed slides. After a 10-min incubation at room temperature, the slides were washed twice with the previous buffer, twice with PBS, and then centrifuged at 200g for 1 min to remove excess buffer. The slides were scanned with a laser fluorescence scanner GenePix 4000A (Axon Instruments) to detect the interaction signals from the TAMRA-labeled Jun proteins (excited at 532 nm) and the Cy5-labeled DNA (excited at 635 nm).

Fluorescence Cross-Correlation Spectroscopy

The RhG-labeled Fos and Jun with carboxy-terminal His6-tag were purified on a Ni-NTA affinity column (QIAGEN), followed by size exclusion chromatography on a PD-10 column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) twice. The Cy5-labeled dsDNA was prepared by the hybridization of two complementary 20-nucleotide ssDNAs (TTCTCCTATGACTCATCCAT and AATGGATGAGTCATA-GGAGA, Fos/Jun-binding sequence in italics), which were synthesized with Cy5-label at their 5′-ends and HPLC-purified by Sigma Genosys Japan. Unlabeled Fos and Jun proteins were synthesized by use of the wheat cell-free dialysis system (Madin et al. 2000). Dual-color FCCS measurements and data analysis were carried out on a ConfoCor 2 fluorescence correlation microscope (Jankowski and Janka 2001) according to manufacturer's manual (Carl Zeiss). The details of the measurement setup have been described earlier (Schwille et al. 1997; Kettling et al. 1998; Koltermann et al. 1998). The RhG-labeled Fos or Jun, the Cy5-labeled dsDNA, and unlabeled Fos or Jun were immediately mixed in a buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, and 0.1 M NaCl) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Samples of 10 μL were applied to a coverglass chamber (Nalge Nunc), which was set on an objective lens (C-Apochromat 40× 1.2W; Carl Zeiss). The samples were excited by two laser beams at 488 nm (RhG) and 633 nm (Cy5) in the femtoliter focal volume positioned 200 μm above the surface of the glass. All measurements were performed at room temperature (23°C).

Acknowledgments

We thank Yoko Ogawa and Masato Yonezawa for assistance in the preparation of wheat germ extracts. This work was supported in part by Special Coordination Funds of the Science and Technology Agency (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology) of the Japanese Government.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL hyana@applc.keio.ac.jp.; FAX 81-45-566-1440.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.218802. Article published online before print in February 2002.

REFERENCES

- Angel P, Karin M. The role of Jun, Fos and the AP-1 complex in cell-proliferation and transformation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1072:129–157. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(91)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieschke J, Giese A, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Zerr I, Poser S, Eigen M, Kretzschmar H. Ultrasensitive detection of pathological prion protein aggregates by dual-color scanning for intensely fluorescent targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:5468–5473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulyk ML, Gentalen E, Lockhart DJ, Church GM. Quantifying DNA-protein interactions by double-stranded DNA arrays. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:573–577. doi: 10.1038/9878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluzel P, Surette M, Leibler S. An ultrasensitive bacterial motor revealed by monitoring signaling proteins in single cells. Science. 2000;287:1652–1655. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigen M, Rigler R. Sorting single molecules: Application to diagnostics and evolutionary biotechnology. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:5740–5747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Földes-Papp Z, Kinjo M. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy in nucleic acids analysis. In: Rigler R, Elson EL, editors. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy—Theory and applications. Boston, MA: Springer; 2001. pp. 25–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gallie DR, Sleat DE, Watts JW, Turner PC, Wilson TM. Mutational analysis of the tobacco mosaic virus 5′-leader for altered ability to enhance translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:883–893. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haab BB, Dunham MJ, Brown PO. Protein microarrays for highly parallel detection and quantitation of specific proteins and antibodies in complex solutions. Genome Biol. 2001;2:Research0004.1–13. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-2-research0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupts U, Maiti S, Schwille P, Webb WW. Dynamics of fluorescence fluctuations in green fluorescent protein observed by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:13573–13578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda S, Saito I, Sugiyama H. Facile synthesis of puromycin-tethered oligonucleotides at the 3′-end. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:5975–5978. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer VR, Horak CE, Scafe CS, Botstein D, Snyder M, Brown PO. Genomic binding sites of the yeast cell-cycle transcription factors SBF and MBF. Nature. 2001;409:533–538. doi: 10.1038/35054095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski T, Janka R. ConfoCor 2—the second generation of fluorescence correlation microscopes. In: Rigler R, Elson EL, editors. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy—theory and applications. Boston, MA: Springer; 2001. pp. 331–345. [Google Scholar]

- Jobling SA, Gehrke L. Enhanced translation of chimaeric messenger RNAs containing a plant viral untranslated leader sequence. Nature. 1987;325:622–625. doi: 10.1038/325622a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John M, Leppik R, Busch SJ, Granger-Schnarr M, Schnarr M. DNA binding of Jun and Fos bZip domains: Homodimers and heterodimers induce a DNA conformational change in solution. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4487–4494. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettling U, Koltermann A, Schwille P, Eigen M. Real-time enzyme kinetics monitored by dual-color fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:1416–1420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinjo M. Detection of asymmetric PCR products in homogeneous solution by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Biotechniques. 1998;25:706–715. doi: 10.2144/98254rr01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltermann A, Kettling U, Bieschke J, Winkler T, Eigen M. Rapid assay processing by integration of dual-color fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy: High throughput screening for enzyme activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:1421–1426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak M. Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Cell. 1986;44:283–292. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90762-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacBeath G, Schreiber SL. Printing proteins as microarrays for high-throughput function determination. Science. 2000;289:1760–1763. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5485.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madin K, Sawasaki T, Ogasawara T, Endo Y. A highly efficient and robust cell-free protein synthesis system prepared from wheat embryos: Plants apparently contain a suicide system directed at ribosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:559–564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiti S, Haupts U, Webb WW. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy: Diagnostics for sparse molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:11753–11757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.11753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto-Sato E, Nemoto N, Kobayashi K, Yanagawa H. Specific bonding of puromycin to full-length protein at the C-terminus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1176–1182. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.5.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita R, Kawagoshi A, Sawasaki T, Madin K, Ogasawara T, Oka T, Endo Y. Ribonuclease activity of rat liver perchloric acid-soluble protein, a potent inhibitor of protein synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20688–20692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto N, Miyamoto-Sato E, Yanagawa H. Fluorescence labeling of the C-terminus of proteins with a puromycin analogue in cell-free translation systems. FEBS Lett. 1999;462:43–46. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01474-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pack CG, Aoki K, Taguchi H, Yoshida M, Kinjo M, Tamura M. Effect of electrostatic interactions on the binding of charged substrate to GroEL studied by highly sensitive fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;267:300–304. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitschke M, Prior R, Haupt M, Riesner D. Detection of single amyloid b-protein aggregates in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer's patients by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Nature Med. 1998;4:832–834. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigaut G, Shevchenko A, Rutz B, Wilm M, Mann M, Seraphin B. A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nature Biotechnol. 1999;17:1030–1032. doi: 10.1038/13732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigler R. Fluorescence correlations, single molecule detection and large number screening. Applications in biotechnology. J Biotechnol. 1995;41:177–186. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(95)00054-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippe K. Simultaneous binding of two DNA duplexes to the NtrC-enhancer complex studied by two-color fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2000;39:2131–2139. doi: 10.1021/bi9922190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schägger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schena M, Shalon D, Davis RW, Brown PO. Quantitative monitoring of gene expression patterns with a complementary DNA microarray. Science. 1995;270:467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwille P, Meyer-Almes FJ, Rigler R. Dual-color fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy for multicomponent diffusional analysis in solution. Biophys J. 1997;72:1878–1886. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78833-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Klausner RD, Collins FS. The mammalian gene collection. Science. 1999;286:455–457. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada S, Kinjo M, Hirokawa N. Oligomeric tubulin in large transporting complex is transported via kinesin in squid giant axons. Cell. 2000;103:141–155. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton JM, Sibanda BL. Amino and carboxy-terminal regions in globular proteins. J Mol Biol. 1983;167:443–460. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80344-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Mural RJ, Sutton GG, Smith HO, Yandell M, Evans CA, Holt RA, et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291:1304–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiemann S, Weil B, Wellenreuther R, Gassenhuber J, Glassl S, Ansorge W, Bocher M, Blocker H, Bauersachs S, Blum H, et al. Toward a catalog of human genes and proteins: Sequencing and analysis of 500 novel complete protein coding human cDNAs. Genome Res. 2001;11:422–435. doi: 10.1101/gr.154701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Bilgin M, Bangham R, Hall D, Casamayor A, Bertone P, Lan N, Jansen R, Bidlingmaier S, Houfek T, et al. Global analysis of protein activities using proteome chips. Science. 2001;293:2101–2105. doi: 10.1126/science.1062191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]