Abstract

Zebrafish Csrp1 is a member of the cysteine- and glycine-rich protein (CSRP) family and is expressed in the mesendoderm and its derivatives. Csrp1 interacts with Dishevelled 2 (Dvl2) and Diversin (Div), which control cell morphology and other dynamic cell behaviors via the noncanonical Wnt and JNK pathways. When csrp1 message is knocked down, abnormal convergent extension cell movement is induced, resulting in severe deformities in midline structures. In addition, cardiac bifida is induced as a consequence of defects in cardiac mesoderm cell migration. Our data highlight Csrp1 as a key molecule of the noncanonical Wnt pathway, which orchestrates cell behaviors during dynamic morphogenetic movements of tissues and organs.

Keywords: gastrulation, heart, Wnt, zebrafish

Morphogenetic movement of cells is regulated by processes involving signaling, cell adhesion, and cytoskeletal remodeling. Before gastrulation in the zebrafish embryo, cells divide on the animal pole and then migrate toward the vegetal pole by shielding movement (1). This dynamic movement commences at 50% epiboly to form three distinct layers: endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm. During this event, mesendoderm cells involute beneath the ectoderm and migrate toward the anterior side. Next, these cells form the notochord, in which the next intercalation movement occurs. Consequently, the notochord extends along the anterior–posterior axis (2). These characteristic convergent extension (CE) cell movements are crucial for orchestrated morphogenetic events.

During the CE movement, multiple signaling cascades control coordinated cell behaviors. silberblick (slb) and pipetail (ppt) zebrafish mutants show abnormal CE movement and display a shortened tail and body axis (3, 4). Because slb and ppt encode Wnt11 and Wnt5, respectively (5), the noncanonical Wnt cascade has been proposed to be essential for CE movement (6). In Drosophila, noncanonical Wnt signaling establishes planar cell polarity of the imaginal discs. In the wing disk, prehairs give rise to distally pointing hairs, where polarity is controlled by several planar cell polarity genes (7). For example, Dishevelled (Dsh) redistributes to the plasma membrane in response to Frizzled (Fz) and localizes to F-actin containing filopodia. This asymmetric translocation is involved in cytoskeletal remodeling, which specifies the polarity of these prehairs (8). In Xenopus, formation of polarized cell protrusions has been shown to be regulated by two GTPases, Rho and Rac (9). These different lines of evidence suggest a close relationship between the noncanonical Wnt pathway and remodeling of the cytoskeleton, which is crucial for cell shape, adhesion, and migration. Nonetheless, factors that mediate noncanonical Wnt signals remain unclear.

Cysteine- and glycine-rich proteins (CSRPs) belong to the LIM domain superfamily and are highly conserved in both vertebrates and invertebrates. The LIM domain can be found in many different proteins, which act on a wide range of phenomena from gene expression to remodeling of the cytoskeleton (10). In vertebrates, three members of the Csrp family, Csrp1, Csrp2, and Csrp3/MLP, have been identified (11–15). Despite extensive structure–function analysis on this protein family, the molecular functions of Csrp1 remain largely unknown.

We found that zebrafish csrp1 is expressed in the mesendoderm, prechordal plate, notochord, and endoderm underlying the cardiac mesoderm. When Csrp1 function is inhibited, embryos display abnormal cell behavior during gastrulation and notochord formation. In addition, these embryos exhibit cardiac bifida. Our analyses reveal that Csrp1 is a novel component of the noncanonical Wnt cascade and coordinates cell behaviors during development.

Results

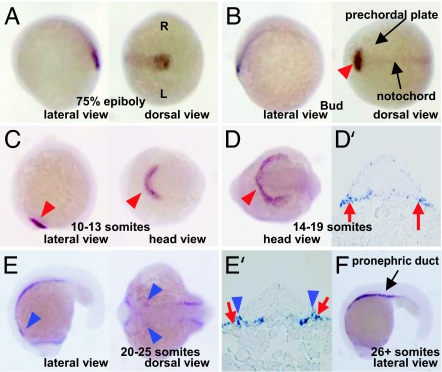

Expression Pattern of Zebrafish csrp1.

To examine the expression pattern of csrp1 in zebrafish embryos, the full-length cDNA was cloned by means of an RT-PCR strategy using the assembled sequences in the Zebrafish Information Network, National Center for Biotechnology Information, and Ensembl databases. csrp1 was found to encode a small protein that contains two LIM motifs with two glycine-rich repeats [supporting information (SI) Fig. 6] (16). Expression of csrp1 is not detected until gastrulation. Robust expression begins in the axis at the 75% epiboly stage (Fig. 1A). This expression extends to the anterior side, and, when the embryo reaches the tail bud stage, csrp1 can be detected in the prepolster (red arrowhead in Fig. 1B) (17). Weak expression is also observed in the prechordal plate and notochord (Fig. 1B). The shape of the csrp1-positive region changes as formation of the polster proceeds (Fig. 1 C and D). By the one- to four-somite stage, expression in the notochord is reduced. csrp1 is also found in the polster precursor cells as examined by coexpression of a prepolster marker, kruppel-like factor 4 (klf4) (data not shown) (17). At the 14- to 19-somite stage, csrp1 expression is evident in the endoderm beneath the cardiac mesoderm (Fig. 1D′). At later stages, expression is found in the polster, pronephric ducts, the endoderm underlying cardiac mesoderm, and a restricted part of the cardiac mesoderm (Fig. 1 E and E′). At the 26-somite stage, expression is detected predominantly in the pronephric ducts (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

Expression patterns of zebrafish csrp1. (A) At 75% epiboly stage, csrp1 is expressed in the mesendoderm in the axis. R, right side of embryo; L, left side of embryo. (B) At the bud stage, expression is observed in the developing notochord and prechordal plate (arrowhead). (C) Expression of csrp1 becomes restricted in the prepolster region (arrowheads) at the 10- to 13-somite stage. (D) Expression is maintained in the polster at the 14- to 19-somite stage (arrowhead). (D′) Expression is also observed in the endoderm (arrows). (E and E′) Expression is detected in the endoderm beneath the cardiac mesoderm (red arrows), as well as in an anterior portion of the cardiac mesoderm (blue arrowheads) at the 14- to 19-somite stage. (F) At the 26-somite stage, csrp1 is expressed in the pronephric ducts.

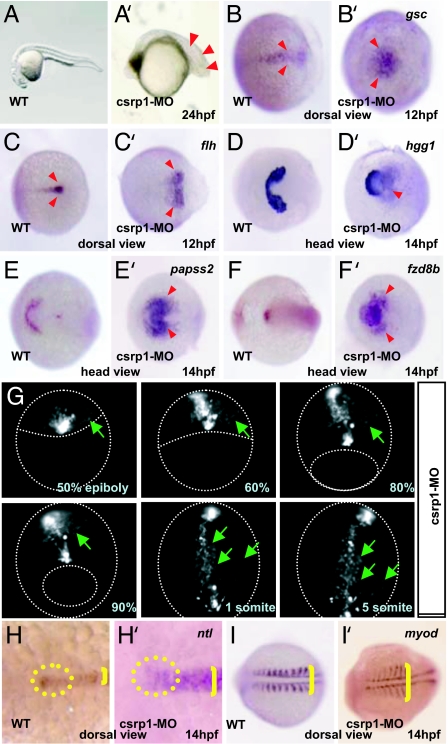

Loss of Csrp1 Function Results in Abnormal Axis Formation.

To investigate the role of Csrp1, we injected zebrafish embryos with two morpholino oligonucleotides (MO) against csrp1; both behaved similarly. A mismatch MO was designed as a negative control, and it did not cause any morphological changes. Injection of the csrp1 MO resulted in a delay of epiboly progression around the yolk. At 24 h postfertilization (hpf), somites were compressed in a shortened posterior region of the body (red arrowheads in Fig. 2A′). In addition, embryos injected with the cspr1 MO had a shorter tail and a disorganized anterior region of the body (Fig. 2A). These phenotypes were rescued by coinjection of mouse Csrp1 mRNA (SI Fig. 6).

Fig. 2.

Knockdown of csrp1 caused defects in gastrulation. (A and A′) Morphants of csrp1 had short bodies with compressed somites (arrowheads) compared with the WT (A). (B, B′, C, and C′) In the WT, marginal cells, which were marked by expression of gsc (B) and flh (C), accumulated at the margin. In the morphants, these cells did not accumulate, making large expression domains of gsc (B′) and flh (C′) at 12 hpf. Anterior migration of these cells was also impaired. (D–F and D′–F′) At 14 hpf, the prepolster region, marked by hgg1 (D) and papss2 (E), formed a U-shaped expression domain. In the morphants, this expression domain became deformed without a clear boundary (D′ and E′). (F and F′) Expression of fzd8b in the head mesenchyme was restricted in the WT at 14 hpf (F). This expression domain was expanded with dispersed signals in the morphants (F′). (G) Notochord cells were visualized by injection of pFlh-EGFP. In the morphants, marginal cells accumulated on the dorsal margin at 50% epiboly stage, but some cells were displaced without accumulation at the midline even at 60–80% epiboly stages (green arrows). At 90% epiboly stage, some mesen doderm cells (green arrows) localized beyond the territory of the notochord. Formation of the notochord was delayed and abnormal without elongation of cell shape. (H and H′) Morphology of the notochord was examined by ntl expression at 14 hpf. The faint but distinct accumulation of ntl-positive cells was observed in the anterior end of the notochord (circle in H). This group of cells was not observed in the morphants (circle in H′). The notochord of the morphants was wider than that of the WT (brackets in H and H′). These pictures were taken at the same magnification. (I and I′) Somites were visualized by expression of myod. In the morphants, thin and compressed somites were formed (bracket in I′) compared with the WT (bracket in I).

Next, we found that ablation of csrp1 causes failure of midline convergence of the presumptive prechordal plate as visualized by goosecoid (gsc) expression (18). As a result, there was a round and broad accumulation of cells at the margin and an extensive delay of subsequent anterior movement (red arrowheads in Fig. 2B′). This was compared with the WT embryo, which displayed a narrow anterior extension of gsc expression (red arrowheads in Fig. 1B). We confirmed these findings by floating head (flh) expression (Fig. 2 C and C′) (19).

We examined expression of hatching gland 1 (hgg1) and 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate synthase 2 (papss2), both of which are expressed in the polster, the most anterior region of the prechordal plate (20). At 14 hpf, the WT embryo displays a U-shaped expression of hgg1 in the polster (Fig. 2D). In the csrp1 morphants, hgg1 expression is restricted to a smaller area (Fig. 2D′). Furthermore, the posterior half of the hgg1-positive region does not form a clear boundary; rather, this area displays a dispersed expression in posterior regions where hgg1 is not normally expressed. In contrast to normal papss2 expression, which is restricted to a distinct region of the polster (Fig. 2E), the expression pattern in the morphants is expanded and does not display a well defined border (Fig. 2E′). Another marker, fzd8b, is expressed in a restricted portion of the ventral telencephalon at 14 hpf in the WT (Fig. 2F) (21). Similar to borders demarcated by other markers, the morphants display expanded and dispersed fzd8b expression in lateral and posterior regions of the telencephalon (red arrowheads in Fig. 2F′), indicating a failure of mesendoderm cell migration in this region.

Involution of the Mesendoderm Is Affected in the csrp1 Morphants.

To observe migration of mesendoderm cells, we injected an EGFP expression construct driven by the flh promoter to restrict EGFP to the notochord (Fig. 2G). When injected into the WT embryos, most EGFP-positive cells are found in the notochord starting from the 90% epiboly stage (SI Fig. 7). During gastrulation and subsequent notochord formation, EGFP-positive cells display the CE cell movement with lateral elongation of cell shape and intercalation (SI Movie 1).

In contrast, the morphants have EGFP-positive cells that do not accumulate at the margin during the onset of gastrulation (Fig. 2G). Some cells indicated by green arrows migrate to the margin at the 50% epiboly stage yet fail to complete midline convergence at the 60–90% epiboly stages. As a result, EGFP-positive cells do not form a clear notochord structure, but rather are dispersed in the lateral plate mesoderm where flh-positive cells are normally not present (green arrows in Fig. 2G and SI Movie 2). These results, together with the expression patterns of csrp1 (Fig. 1), indicate that Csrp1 plays crucial roles in involution and migration of mesendoderm cells during gastrulation.

To further confirm this, we examined ntl expression. In the WT, a cluster of ntl-expressing cells is formed at the anterior end of the notochord at 14 hpf (Fig. 2H). Contrary to this, the ntl cell cluster is not formed in the csrp1 morphants; rather, the expression of ntl fades toward the anterior end (Fig. 2H′). In addition, the notochord of these embryos becomes wider (Fig. 2H′). Visualization of myoD expression reveals that somites are compressed along the anterior–posterior axis, with each thin somite elongated laterally (Fig. 2I′).

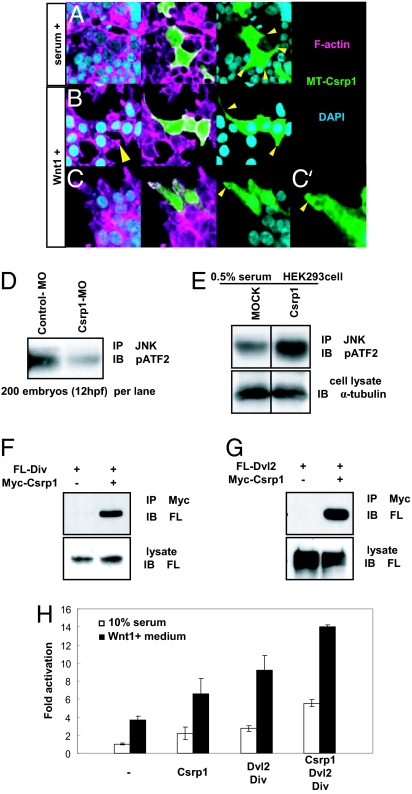

Noncanonical Wnt Signaling and Csrp1.

Wnt11 is expressed in the mesendoderm cells and the presumptive notochord, whereas Wnt5 is expressed in the posterior presomitic mesoderm (4, 22). We examined the expression of csrp1 in wnt11 and wnt5 morphants. csrp1 expression is not affected in either morphant (SI Fig. 8). This suggests that expression of csrp1 is regulated independent of Wnt11 and Wnt5. Consistent with this, expression of wnt11 and wnt5 is not affected in the csrp1 morphants (data not shown).

Precursor cells of the prechordal plate have polarized pseudopod-like processes at the onset of gastrulation. Formation of these cell protrusions is controlled by the planar cell polarity/noncanonical Wnt cascade (23). An intriguing possibility is that these pseudopodial processes might be formed via interplay between Csrp1 and the noncanonical Wnt pathway. To test this possibility, we examined morphological changes induced by introduction of Csrp1 in HEK293 cells. In the presence of serum, Csrp1-expressing HEK293 cells form multiple tiny protrusions where Csrp1 localized (yellow arrowheads in Fig. 3A). In this condition, Csrp1-negative cells do not form such distinct processes (SI Table 1). As reported previously (24, 25), stimulation by Wnt1 alone induces polarized elongation of cell shape even in Csrp1-negative cells (yellow arrowhead in Fig. 3B Left). When Csrp1 is expressed in HEK293 cells stimulated by Wnt1, the cells elongate to form even larger protrusions (yellow arrowheads in Fig. 3B Right). In this case, the cells did not make multiple processes, but rather formed a single, larger protrusion. Membrane ruffling is induced in such protrusions, where Csrp1 colocalized (Fig. 3 C and C′). This implies that Csrp1 acts in a cooperative manner with the noncanonical Wnt pathway. Therefore, Csrp1 most likely transforms the classical Wnt1-induced cell elongation into polarized protrusions.

Fig. 3.

Csrp1 and the noncanonical Wnt/JNK signaling cascade. (A) Overexpression of Csrp1 in HEK293 cells induced formation of multiple cell protrusions (arrowheads) in the presence of 10% serum. In these protrusions, Csrp1 localized as shown by antibody staining. (B) When stimulated by Wnt1-conditioned medium, Csrp1-negative HEK293 cells elongated and formed small protrusions (arrowhead in Left). In contrast, Csrp1-expressing cells formed large protrusions where Csrp1 colocalized (arrowheads in Right). (C) Csrp1 accumulated in ruffling membrane formed at the edge of protrusions (arrowhead). A higher-magnification view is shown in C′. (D) Cell lysates prepared from zebrafish embryos were used for immunoprecipitation using an anti-JNK antibody. The amount of phosphorylated ATF2 in the precipitate was decreased in the csrp1 morphants, as revealed by an anti-phospho ATF2 antibody, compared with embryos injected with control MO. (E) Cell lysates were prepared from mock-transfected and Csrp1-expressing HEK293 cells. Phosphorylation of ATF2 was enhanced in the Csrp1-expressing cells. α-Tubulin was stained for a control. (F) From HEK293 cells expressing Flag-tagged Div (FL-Div) and Myc-tagged Csrp1 (Myc-Csrp1), Div was coprecipitated with Csrp1. (G) Immunoprecipitation assay using HEK293 cells. Flag-tagged Dvl2 (FL-Dvl2) and/or Myc-Csrp1 was introduced, and then Csrp1 was precipitated from lysates. In the precipitates, Dvl2 was detected. (H) A pAR-luciferase reporter and an expression vector for cJun were introduced in HEK293 cells along with Csrp1, Dvl2, and Div. This reporter is activated synergistically by Csrp1 and Dvl2/Div. This effect is further enhanced in the presence of Wnt1.

The JNK pathway is involved in cytoskeletal remodeling, as previously suggested (26). Indeed, the amount of phosphorylated activating transcription factor (ATF) is reduced in the csrp1 morphants (Fig. 3D). To further examine this, we determined whether JNK was activated in HEK293 cells. Introduction of Csrp1 in HEK293 cells significantly increases the amount of phosphorylated ATF2 that is coprecipitated with JNK (Fig. 3E), indicating that Csrp1 is involved in activation of the JNK pathway. In addition, Diversin (Div), which is involved in JNK activation (27), is found to interact with Csrp1, as revealed by coprecipitation of these two proteins from HEK293 cells (Fig. 3F). Next, we examined the functional relationship between Csrp1 and components of noncanonical Wnt signaling. First, we analyzed molecules coprecipitated with Csrp1. Interestingly, Dishevelled 2 (Dvl2) was found in the precipitate (Fig. 3G).

For further confirmation, we coexpressed Csrp1, Div2, Div, c-Jun, and a JNK responsive reporter gene in HEK293 cells (Fig. 3H). In this assay, these three components acted synergistically on luciferase activity. Interestingly, this synergism is more evident in the presence of Wnt1.

Additional data using zebrafish embryos are presented in SI Figs. 9 and 10.

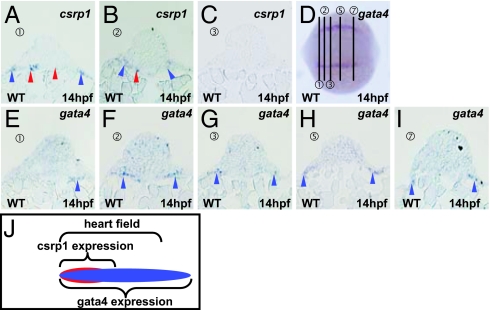

Csrp1 and Heart Development.

As described above, csrp1 is expressed in the endoderm underlying cardiac mesoderm and a restricted region of cardiac mesoderm (Fig. 1E). To explore further, we examined csrp1 expression as it relates to expression of a cardiac marker, gata4. At 14 hpf, csrp1 is expressed in the cardiac mesoderm and underlying endoderm (blue and red arrowheads, respectively, in Fig. 4 A–C), as shown in sections made at positions indicated in Fig. 4D. In corresponding serial sections, expression of gata4 is detected in the cardiac mesoderm, yet its expression domain is larger and expanded posteriorly (blue arrowheads in Fig. 4 E–I). These data indicate that expression of csrp1 is restricted to an anterior portion of the cardiac mesoderm as contrasted with the broad expression of gata4; hence, csrp1 expression defines a unique subregion of cardiac mesoderm (Fig. 4J). In addition, csrp1 is expressed in the endoderm beneath cardiac mesoderm.

Fig. 4.

Expression of csrp1 in the cardiac mesoderm. Expression of csrp1 (A–C) and gata4 (E–I) was examined at 14 hpf in sections made at positions indicated in D. In an anterior region of the cardiac mesoderm that expresses gata4 (E), expression of csrp1 was observed in the mesoderm (blue arrowheads) and endoderm (red arrowheads) (A). (B and F) In a serial section, expression of csrp1 and gata4 was detected in the cardiac mesoderm (blue arrowheads). In this section, csrp1 is also expressed in the underlying endoderm (red arrowhead, B). (C and G) Expression of csrp1 was not detected in the next caudal sections, although gata4 expression was detected. (H and I) In a more posterior section, gata4 was still expressed. (J) A schematic illustration of the csrp1-positive and the gata4-positive domains in the heart field.

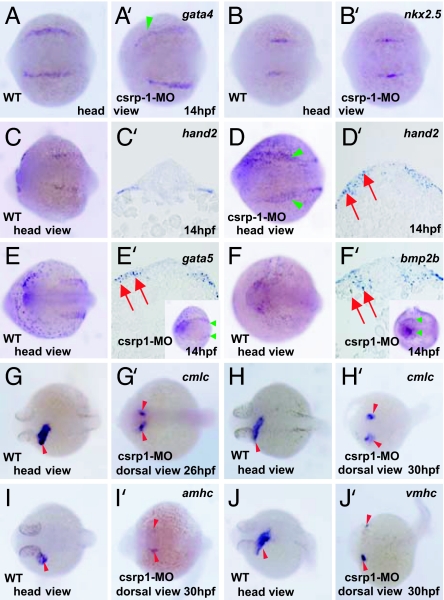

To explore the potential functions of Csrp1 in cardiac development, we examined the expression of several cardiac markers, such as gata4, nkx2.5, hand2, gata5, and bmp2b (Fig. 5 A–F and A′–F′) (28–31). In the csrp1 morphants, expression of gata4 and nkx2.5 is not affected at 14 hpf; however, the expression domain becomes muddled and laterally located (Fig. 5 A, A′, B, and B′). hand2 is expressed in the cardiac mesoderm in the WT (Fig. 5 C and D), whereas its expression in the morphants is broader (Fig. 5 C′ and D′). gata5 and bmp2b are expressed in the endoderm in the WT (Fig. 5 E and F). Expression of these genes also becomes broad and muddled in the morphants, with some cells distributed in an ectopic area (Fig. 5F′).

Fig. 5.

Cardiac bifida in the csrp1 morphants. (A–D and A′–D′) Expression of cardiac markers, such as gata4 or nkx2.5, was not affected in the csrp1 morphants at 14 hpf (A′ and B′, respectively), compared with the WT (A and B). In some cases, expression domains of these genes became faint and muddled (green arrowhead in A′). Note that the expression domain of gata4 shifted laterally, leaving a wider space in the middle. (C, C′, D, and D′) hand2, which is expressed in the cardiac mesoderm of the WT (C), was expressed in wider domains in the morphants (green arrowheads in D). This expansion was confirmed in sections (red arrows in D′) compared with the WT (C′). (E, E′, F, and F′) Expression of endodermal markers, such as gata5 (E and E′) and bmp2b (F and F′) was examined. Both genes were expressed in the endoderm beneath the cardiac mesoderm in the WT (E and F). In the morphants, expression of these genes became expanded (red arrows in sections and green arrowheads in whole mount, E′ and F′). (G and H) cmlc is normally expressed in the heart tube at 26 hpf (G) and 30 hpf (H). (G′ and H′) Cardiac mesoderm cells did not fuse to form a heart tube in the csrp1 morphants at 26 hpf (G′) and 30 hpf (H′). (I, I′, J, and J′) Likewise, as revealed by expression of amhc (I and I′) and vmhc (J and J′) at 30 hpf, cardiac mesoderm cells were kept separated.

More profound effects are observed at later stages. At 26 hpf, expression of cmlc becomes separated in the morphants (Fig. 5G′), whereas formation of a single heart tube is visualized by its expression in the WT (Fig. 5G). At 30 hpf, cardiac mesoderm cells remain separated, as visualized by expression of cmlc, amhc, and vmhc (Fig. 5 H′, I′, and J′, respectively). These lines of evidence indicate that Csrp1 regulates migration of cardiac mesoderm cells. Hence, by preventing migration of cells and subsequent fusion of the bilateral cardiac mesoderm at the midline, a loss of Csrp1 function results in cardiac bifida.

Discussion

Expression of csrp1 is observed in the mesendoderm and notochord, but its notochord expression is reduced before the intercalation movement it initiates (Fig. 1). Nonetheless, knockdown of csrp1 results in abnormal cell behaviors in both notochord and mesendoderm (Fig. 2). As shown in SI Movies 1 and 2, mesen doderm cells in WT embryos display organized behaviors and subsequent CE movement, whereas those of the morphants stay disorganized without exhibiting polarized movement and elongation of cell shape. This suggests that Csrp1 is involved in the initiation of cell behaviors in the mesendoderm, which affects subsequent intercalation movement. We also suggest a possibility that Csrp1-positive cells at the frontier of mesendoderm cell migration might regulate behaviors of caudally located migrating cells. Several markers, such as shh and ntl, are expressed in the notochord normally, suggesting that Csrp1 is not involved in this differentiation pathway. csrp1 is strongly expressed in the prepolster (Fig. 1), and its expression pattern resembles that of klf4. Nonetheless, a loss of Klf4 function results in a loss of polster formation and down-regulation of marker genes (17). In contrast, in the csrp1 morphants, the polster was formed without extinction of hgg1 or papss2 expression; however, the morphology is altered (Fig. 2 D′ and E′). Consistent with this, klf4 expression is maintained in the morphants (data not shown). These results suggest that Klf4 regulates differentiation of the polster, whereas Csrp1 controls its morphogenesis based on cell movement. In this sense, morphology of Cap1 (cyclase-associated protein-1) morphants resembles that of the csrp1 morphants (20). Cap1 is required for the apical regulation of actin dynamics during morphogenetic movement (32). Because cap1 is expressed in the anterior mesendoderm (20), there might be a functional interaction between Cap1 and Csrp1. To explore this further, putative interacting partners for Csrp1 must be identified.

As shown in Fig. 3 A and B, introduction of Csrp1 into HEK293 cells induced formation of cell protrusions, which is regulated cooperatively with Wnt1, suggesting synergism between Csrp1 and the noncanonical Wnt pathway. Mesendoderm cells migrate in an integrin/focal adhesion kinase signaling-dependent manner in axis formation. Abrogation of integrin or focal adhesion kinase signaling results in a failure of gastrulation in both Xenopus and zebrafish (33, 34). Formation of cell protrusion is induced by activation of Rac-GTPase, which is regulated by multiple factors and their interactions (35). Among them, paxillin and zyxin contain multiple LIM domains (36, 37). In fact, Csrp1 has been shown to interact with zyxin, which is essential for the integrin-linked cascade to control cell motility (38). Therefore, Csrp1 could be a component of complexes that control integrin-dependent cell migration of mesendoderm and cardiac mesoderm cells.

It has been shown that Csrp1 and Csrp2 interact with GATA2/4/6 to up-regulate serum response factor-dependent transcription (39). Because gata5 is expressed in the endoderm underlying cardiac mesoderm, we performed the same immunoprecipitation assay yet failed to detect interaction between Csrp1 and Gata5 (data not shown). To explore possible involvement in gene regulation, microarray analysis should be carried out to examine gene expression profiles in csrp1 morphants, because Csrp1 is indeed in the nucleus and its nuclear translocation is enhanced by Wnt1 as shown in Fig. 3 A and C. In addition, functions of Csrp proteins in establishment of cytoarchitecture must be analyzed to understand tissue interactions and signaling from the cytoskeleton to the nucleus, which seems to depend on Wnt1 (data not shown).

As suggested by cardiac bifida mutants, such as mil, oep, bon, fau, and cas, endoderm is involved in migration of heart precursors (30, 40–43), and tissue interaction between endoderm and cardiac mesoderm is a key for correct migration of cardiac progenitors. Consistent with this, csrp1 is expressed in the endoderm underlying cardiac mesoderm, and a loss of Csrp1 function results in the same cardiac bifida as shown in this study. In addition to the endodermal expression, csrp1 is expressed in a subset of cardiac mesoderm cells (Fig. 4). Because injection of the csrp1 MOs abrogates the function in both endoderm and mesoderm, we do not know whether Csrp1 plays distinct roles in mesoderm and endoderm. Nonetheless, during the formation of the notochord, Csrp1, which is expressed only in the anterior-most population of cells, is involved in the cell behaviors of the caudally located Csrp1-negative cells (additional data are shown in SI Fig. 11). This suggests that Csrp1 expressed in a small population of cardiac progenitors might control migration of Csrp1-negative cardiac mesoderm cells. Although precise analysis is needed to explore the Csrp1 functions, our data highlight Csrp1 as an essential factor that connects the noncanonical Wnt signals to cell behaviors and migration.

Materials and Methods

cDNA Probes and in Situ Hybridization.

Myc-tagged zebrafish csrp1 and other zebrafish probes, hgg1, papss2, ntl, myod, gata4, gata5, nkx2.5, hand2, bmp2b, cmlc, vmhc, and amhc, for in situ hybridization were isolated from cDNA libraries using PCR techniques with appropriate sets of primers. Maintenance of our fish colony and whole-mount in situ hybridization were performed as described (44). HA-tagged zebrafish NDaam1a (1–417 aa region) was constructed from this cDNA by using RT-PCR techniques. Myc-tagged mouse full-length Daam1 was the kind gift of T. Yamaguchi (National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD) (45). Mouse Dvl2 and Xdd1 were kindly gifted by R. Habas (University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, NJ) (24) and S. Y. Sokol (Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY) (46), respectively. Human Div was purchased from Kazusa DNA Research Institute (Chiba, Japan). pFlh-EGFP was a kind gift from M. E. Halpern (Carnegie Institute, Baltimore, MD) (47). The zebrafish gsc and fzd8b probes were kindly provided by W. Shoji (Institute of Development, Aging, and Cancer, Miyagi, Japan) (48) and T. L. Huh (Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea) (49), respectively.

Immunocytochemistry, Immunoprecipitation, and Western Blotting.

HEK293 cells were maintained in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS. Transient transfection was performed by using polyethylenimine (Polysciences, Warrington, PA). For immunocytochemistry, cells were fixed for 15 min in a 3.7% formaldehyde/PBS solution. After fixation, cells were permeabilized for 5 min with 0.2% Triton X-100. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies for 1 h and then incubated with a second antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 594 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated Phalloidin for F-actin staining. Antibodies against Myc or Flag epitopes were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), Sigma (St. Louis, MO), and Rockland. For nuclear staining, cells were incubated with DAPI (Sigma). Images were recorded and processed with an Olympus (Tokyo, Japan) FV1000 confocal microscope and processed by Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting were performed as described (50).

cJun N-Terminal Kinase Activity Assay.

Transfected HEK293 cells were lysed by the RIPA buffer and transferred into microcentrifuge tubes. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 17,000 × g for 10 min. An anti-JNK antibody (Sigma) was added to cell lysates, and then EZview Red Protein A Affinity Gel beads (Sigma) were mixed. Samples were gently rocked for 4 h at 4°C and then were centrifuged at 8,000 × g for several seconds. Collected beads were washed with Wash Buffer 1 (Sigma). Assay buffer with ATF2 substrate (Sigma) was added, and samples were incubated for 30 min at 30°C. The reaction was terminated by addition of 4× SDS sample buffer and boiling. All samples were subjected to SDS/PAGE and transferred to a membrane to probe with an anti-phospho-ATF2 (pThr69,71) conjugated with peroxidase (Sigma) overnight at 4°C. For JNK activation experiments, HEK293 cells were transfected with various combinations of plasmids: a pFR-Luc construct (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), a β-galactosidase expression plasmid, and expression constructs containing Csrp1 and Gal4-DBD-fused cJun (pFA2-cJun; Stratagene). A total amount of transfected DNA was kept constant by adding an empty vector. Forty hours after transfection, cells were lysed, and luciferase activities were measured by standardizing the transfection efficiency with β-galactosidase activities.

Injection of MOs and mRNAs into Zebrafish Eggs.

MOs were designed and synthesized by Gene Tools (Philomath, OR). Sequences were as follows: zCsrp1, 5′-CTGCTAGGTGTGTGGATATGAAGAG and 5′-CTGTTGTGGGAATGAAGAGAGTTTG-3′. Control MOs have four base mismatches. MOs were solubilized in Danieau solution. For in vitro synthesis of mRNAs, the RiboMAX Large Scale RNA Production System (Promega, Madison, WI) was used. Injection was carried out as described (48).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Wataru Shoji for helpful discussions. We also thank Marnie E. Halpern, Raymond Habas, Sergei Sokol, Terry P. Yamaguchi, Wataru Shoji, and Tae-Lin Huh for supplying materials. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan (to T.O.), a Creative Basic Research Grant from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan (to T.O.), and the Exploratory Research Program for Young Scientists (Y.S.K.).

Abbreviations

- MO

morpholino oligonucleotide

- CE

convergent extension

- hpf

hours postfertilization.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0702000104/DC1.

References

- 1.Driever W. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1995;5:610–618. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(95)80030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myers DC, Sepich DS, Solnica-Krezel L. Trends Genet. 2002;18:447–455. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02725-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heisenberg CP, Tada M, Rauch GJ, Saude L, Concha ML, Geisler R, Stemple DL, Smith JC, Wilson SW. Nature. 2000;405:76–81. doi: 10.1038/35011068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kilian B, Mansukoski H, Barbosa FC, Ulrich F, Tada M, Heisenberg CP. Mech Dev. 2003;120:467–476. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(03)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rauch GJ, Hammerschmidt M, Blader P, Schauerte HE, Strahle U, Ingham PW, McMahon AP, Haffter P. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1997;62:227–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu S, Liu L, Korzh V, Gong Z, Low BC. Cell Signalling. 2006;18:359–372. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong LL, Adler PN. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:209–221. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.1.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Axelrod JD, Miller JR, Shulman JM, Moon RT, Perrimon N. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2610–2622. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.16.2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tahinci E, Symes K. Dev Biol. 2003;259:318–335. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kadrmas JL, Beckerle MC. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:920–931. doi: 10.1038/nrm1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sadler I, Crawford AW, Michelsen JW, Beckerle MC. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1573–1587. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.6.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiskirchen R, Bister K. Oncogene. 1993;8:2317–2324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arber S, Halder G, Caroni P. Cell. 1994;79:221–231. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crawford AW, Pino JD, Beckerle MC. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:117–127. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiskirchen R, Pino JD, Macalma T, Bister K, Beckerle MC. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28946–28954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiskirchen R, Gunther K. BioEssays. 2003;25:152–162. doi: 10.1002/bies.10226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardiner MR, Daggett DF, Zon LI, Perkins AC. Dev Dyn. 2005;234:992–996. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schulte-Merker S, Hammerschmidt M, Beuchle D, Cho KW, De Robertis EM, Nusslein-Volhard C. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1994;120:843–852. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melby AE, Kimelman D, Kimmel CB. Dev Dyn. 1997;209:156–165. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199706)209:2<156::AID-AJA2>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daggett DF, Boyd CA, Gautier P, Bryson-Richardson RJ, Thisse C, Thisse B, Amacher SL, Currie PD. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1632–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SH, Park HC, Yeo SY, Hong SK, Choi JW, Kim CH, Weinstein BM, Huh TL. Mech Dev. 1998;78:193–201. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makita R, Mizuno T, Koshida S, Kuroiwa A, Takeda H. Mech Dev. 1998;71:165–176. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ulrich F, Concha ML, Heid PJ, Voss E, Witzel S, Roehl H, Tada M, Wilson SW, Adams RJ, Soll DR, Heisenberg CP. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2003;130:5375–5384. doi: 10.1242/dev.00758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Habas R, Kato Y, He X. Cell. 2001;107:843–854. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00614-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kida YS, Sato T, Miyasaka KY, Suto A, Ogura T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6708–6713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608946104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin-Blanco E, Pastor-Pareja JC, Garcia-Bellido A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7888–7893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.7888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwarz-Romond T, Asbrand C, Bakkers J, Kuhl M, Schaeffer HJ, Huelsken J, Behrens J, Hammerschmidt M, Birchmeier W. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2073–2084. doi: 10.1101/gad.230402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angelo S, Lohr J, Lee KH, Ticho BS, Breitbart RE, Hill S, Yost HJ, Srivastava D. Mech Dev. 2000;95:231–237. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reiter JF, Verkade H, Stainier DY. Dev Biol. 2001;234:330–338. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reiter JF, Alexander J, Rodaway A, Yelon D, Patient R, Holder N, Stainier DY. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2983–2995. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serbedzija GN, Chen JN, Fishman MC. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1998;125:1095–1101. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.6.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benlali A, Draskovic I, Hazelett DJ, Treisman JE. Cell. 2000;101:271–281. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80837-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hens MD, DeSimone DW. Dev Biol. 1995;170:274–288. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crawford BD, Henry CA, Clason TA, Becker AL, Hille MB. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3065–3081. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown JH, Del Re DP, Sussman MA. Circ Res. 2006;98:730–742. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000216039.75913.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaller MD. Oncogene. 2001;20:6459–6472. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmeichel KL, Beckerle MC. Cell. 1994;79:211–219. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beckerle MC. BioEssays. 1997;19:949–957. doi: 10.1002/bies.950191104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang DF, Belaguli NS, Iyer D, Roberts WB, Wu SP, Dong XR, Marx JG, Moore MS, Beckerle MC, Majesky MW, Schwartz RJ. Dev Cell. 2003;4:107–118. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00396-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alexander J, Rothenberg M, Henry GL, Stainier DY. Dev Biol. 1999;215:343–357. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kikuchi Y, Trinh LA, Reiter JF, Alexander J, Yelon D, Stainier DY. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1279–1289. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kupperman E, An S, Osborne N, Waldron S, Stainier DY. Nature. 2000;406:192–195. doi: 10.1038/35018092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schier AF, Neuhauss SC, Helde KA, Talbot WS, Driever W. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1997;124:327–342. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thisse C, Thisse B, Schilling TF, Postlethwait JH. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1993;119:1203–1215. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakaya MA, Habas R, Biris K, Dunty WC, Jr, Kato Y, He X, Yamaguchi TP. Gene Expression Patterns. 2004;5:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sokol SY. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1456–1467. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(96)00750-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gamse JT, Thisse C, Thisse B, Halpern ME. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2003;130:1059–1068. doi: 10.1242/dev.00270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shoji W, Isogai S, Sato-Maeda M, Obinata M, Kuwada JY. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2003;130:3227–3236. doi: 10.1242/dev.00516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim SH, Shin J, Park HC, Yeo SY, Hong SK, Han S, Rhee M, Kim CH, Chitnis AB, Huh TL. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2002;129:4443–4455. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kida Y, Maeda Y, Shiraishi T, Suzuki T, Ogura T. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2004;131:4179–4187. doi: 10.1242/dev.01252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.