Abstract

Activity-dependent release of ATP from synapses, axons and glia activates purinergic membrane receptors that modulate intracellular calcium and cyclic AMP. This enables glia to detect neural activity and communicate among other glial cells by releasing ATP through membrane channels and vesicles. Through purinergic signalling, impulse activity regulates glial proliferation, motility, survival, differentiation and myelination, and facilitates interactions between neurons, and vascular and immune system cells. Interactions among purinergic, growth factor and cytokine signalling regulate synaptic strength, development and responses to injury. We review the involvement of ATP and adenosine receptors in neuron–glia signalling, including the release and hydrolysis of ATP, how the receptors signal, the pharmacological tools used to study them, and their functional significance.

Functional interactions between neurons and glia have been suspected for decades, but how glia might detect neural activity, communicate with other glial cells, and influence neuronal function have proved to be difficult questions to answer. Before purinergic signalling was considered, several other mechanisms were explored for neuron–glia communication, but each of these was comparatively limited. Astrocytes can communicate through gap junctions1, but this was viewed in the context of maintaining homeostasis of extracellular potassium. Bursts of action potentials fired by axons release potassium, which is taken up by astrocytes and dispersed through an astrocytic syncytium coupled by gap junctions. The build up of potassium during prolonged high-frequency stimulation can produce calcium transients in myelinating glia (Schwann cells) in the sciatic nerve2, but stimulation in the normal physiological range does not have this effect. Glial membrane receptors can be activated by many different neurotransmitters3, although this is most relevant to glia having access to neurotransmitter spreading beyond the synaptic cleft4. Purinergic signalling has emerged as the most pervasive mechanism for intercellular communication in the nervous system, affecting communication between many types of neurons, all types of glia, and vascular cells5,6.

Here we examine the history and recent developments of neuron–glia signalling and the prominent role of extracellular ATP in these interactions. We review the mechanisms of ATP release from cells and the large family of membrane receptors for extracellular ATP and adenosine. The pharmacology and expression of these receptors in glia are summarized, and the consequences of purinergic signalling in neuron–glia communication are discussed, with an emphasis on glial regulation of synaptic transmission, activity-dependent myelination, and nervous system response to injury.

ATP in cell–cell signalling

ATP has long been recognized as an intracellular energy source, although its acceptance as an extracellular signalling molecule has taken considerably longer. The potent effects of ATP on the heart and blood vessels were first described by Drury and Szent-Györgyi in 1929 (REF. 7). Some 40 years later, ATP, a purine, was proposed as a neurotransmitter in non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic nerves in the gut and bladder, and the word ‘purinergic’ was coined8.

ATP was first proposed as a putative transmitter in sensory nerves9, and later established as a transmitter in motor nerves10,11 and some CNS neurons12. Complex effects of ATP signalling were immediately apparent, as either excitation13 or inhibition14 of neurotransmission could result. In part, this reflected interactions between signalling by ATP and its co-transmitter, but it was recognized that the three phosphate bonds of ATP were readily cleaved by enzymatic hydrolysis to yield ADP, AMP and adenosine (FIG. 1). The supposition that there must be a complex family of membrane receptors specialized to respond to these different reaction products of ATP hydrolysis was quickly confirmed, and the past decade has seen rapid advances in the identification and characterization of 19 distinct purinergic receptors6,15.

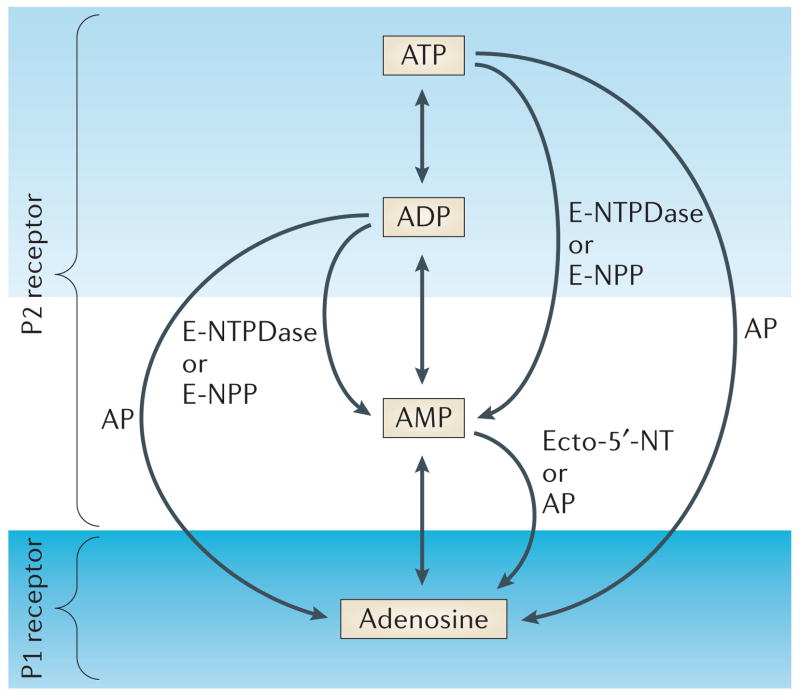

Figure 1. Purinergic receptors bind extracellular ATP and the reaction products that result from its enzymatic hydrolysis by ectonucleotidases.

P2 receptors bind ATP and ADP, whereas P1 receptors bind adenosine. The metabolism of extracellular ATP is regulated by several ectonucleotidases, including members of the E-NTPDase (ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase) family and the E-NPP (ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase) family. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase (Ecto-5′-NT) and alkaline phosphatase (AP) catalyse the nucleotide degradation to adenosine.

Unlike other neurotransmitter systems, the hallmark of which is exquisite specificity, purinergic signalling confounded early investigators by its promiscuity. Not only is ATP released by the presynaptic terminal16, it can also be released by the postsynaptic membrane17 and other cells. This release occurs not only in response to neurotransmitter stimulation, but also in response to other physiological states, such as hypoxia (for a review, see REF. 18). This greatly expands the functional significance of purinergic signalling in the brain. Although it was apparent from the earliest studies that this cell–cell signalling is not limited to the heart and vasculature7, purinergic signalling reached bewildering complexity as the involvement of extracellular ATP was found in studies of intercellular signalling between a wide variety of cells, including those well outside the field of neuronal signalling, such as vascular and immune system cells, platelets, macrophages, lymphocytes and mast cells (for a review, see REF. 5). Moreover, purinergic receptor activation can engage a host of second messenger systems and other cell–cell signalling molecules, including calcium, cyclic AMP (cAMP), inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (Ins(1,4,5)P3), phospholipase C (PLC), arachidonic acid and nitric oxide. Although this complexity was a challenge to early investigators, it was but a hint at the broad scope of phenomena supported by this cell–cell signalling system.

Whereas classical neurotransmitters are regulated simply by the release and removal of transmitter from the synaptic cleft, each of the products of ATP hydrolysis can activate different types of receptor (FIG. 1). For example, P2 receptors bind ATP and ADP, and P1 receptors bind adenosine (FIG. 2). ATP and its final reaction product, adenosine, often have antagonistic effects, providing an elegant mechanism of homeostatic regulation. The complexity of the purinergic receptor family balances the promiscuity of ATP release, thereby providing functional specificity and universality.

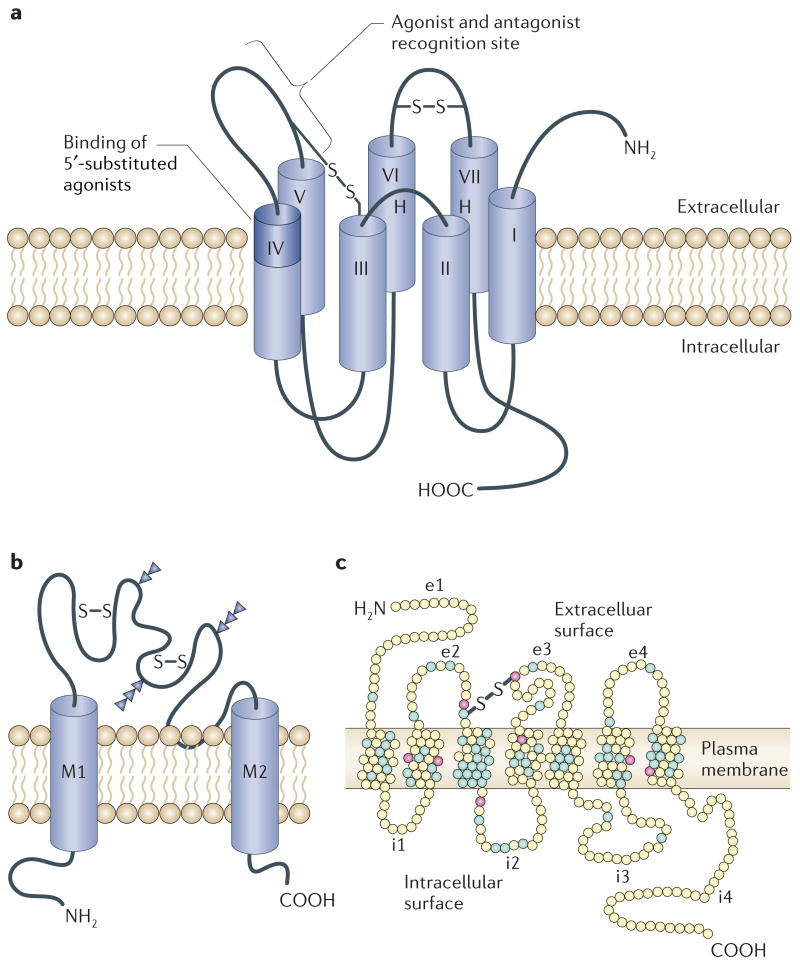

Figure 2. Membrane receptors for extracellular ATP and adenosine.

The P1 family of receptors for extracellular adenosine are G-protein-coupled receptors that signal by inhibiting or activating adenylate cyclase (a). The P2 family of receptors bind extracellular ATP or ADP, and are comprised of two types of receptor (P2X and P2Y). The P2X family of receptors are ligand-gated ion channels (b) and the P2Y family are G-protein-coupled receptors (c). S–S, disulphide bond; e1–e4, extracellular domain loops 1–4; i1–i4, intracellular domain loops 1–4. Panel a modified, with permission, from REF. 83 © (1998) Elsevier Science. Panel b reproduced, with permission, from REF. 70 © (1994) Macmillan Publishers Ltd. Panel c modified, with permission, from REF. 167 © (2006) Elsevier Science.

Purines in neuron–glia signaling

New findings from purinergic research began to converge with findings from glial research as it became more widely appreciated that ATP was co-released from synaptic vesicles and was therefore accessible to perisynaptic glia. Pharmacological and receptor expression studies revealed a broad range of purinergic receptors in all major classes of glia, including Schwann cells in the PNS and oligodendrocytes, astrocytes and microglia in the CNS (TABLE 1). This discovery of a common currency for cell–cell communication suggested the possibility of an intercellular signalling system that could functionally unite glia and neurons19. Studies of astrocytes in culture20,21 and in brain slices4,22 revealed robust calcium responses to the application of ATP, and to more selective agonists of specific purinergic receptors (FIG. 3). Both types of myelinating glia — Schwann cells in the PNS23–25 and oligodendrocytes in the CNS26 — were found to exhibit robust calcium responses to application of ATP, and calcium responses were seen in specialized Schwann cells at the neuromuscular junction activated by purines released during synaptic transmission27.

Table 1.

Purinergic receptors in glial cells

| Receptor | Astrocyte | Müller (eye) | Enteric glia | Schwann cells

|

Oligodendrocytes

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myelin | Non-myelin | Terminal | Progenitor | Myelin | Microglia | ||||

| Adenosine | |||||||||

| A1 | R,P,F | F | R | P,F | F | ||||

| A2A | F | R,P,F | R | F | |||||

| A2B | F | R | R | F | |||||

| A3 | F | R | F | ||||||

| ATP (ionotropic) | |||||||||

| P2X1 | R,P,F | R | |||||||

| P2X2 | R,P,F | ||||||||

| P2X3 | R,P,F | ||||||||

| P2X4 | R,P,F | R | R,P,F | ||||||

| P2X5 | R,F | R | P | ||||||

| P2X6 | R,P | P | |||||||

| P2X7 | R,P | R,P,F | P | F | P,F | F | P,F | ||

| ATP (metabotropic) | |||||||||

| P2Y1 | R,P,F | F | F | R,F | |||||

| P2Y2 | R,F | F | F | F | F | F | F | ||

| P2Y4 | R,F | F | F | R,F | |||||

| P2Y6 | R,F | F | R,F | ||||||

| P2Y11 | F | ||||||||

| P2Y12 | F | R,F | |||||||

| P2Y13 | F | R | |||||||

| P2Y14 | F | ||||||||

R, mRNA evidence; P, protein evidence; F, functional evidence. Functional evidence includes calcium imaging, protein kinase activation, responses to selective agonists and antagonists, and electrophysiological studies. For more information about receptor subtypes on glial cells see also REFS 15,168.

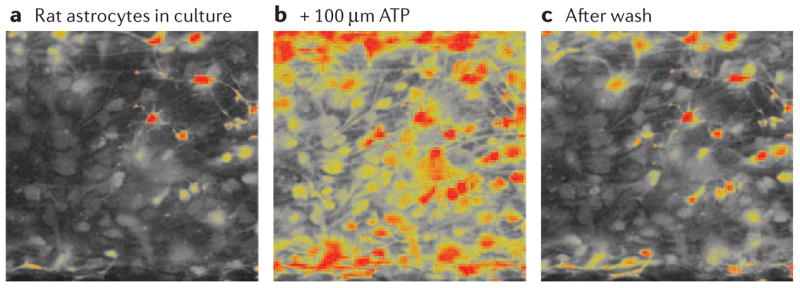

Figure 3. Astrocytes have several types of ionotropic and metabotropic membrane receptor for ATP and its breakdown products, ADP, AMP and adenosine, which increase intracellular calcium concentrations.

Calcium transients and waves induced by extracellular ATP are important in intercellular communication between astrocytes and between neurons and astrocytes. a | Rat astrocytes in culture. b | Application of 100 μM ATP to cultured rat astrocytes resulted in rapid and large increases in intracellular calcium concentrations. c | Shows recovery after a 15 min wash. Intracellular calcium concentration was monitored using confocal microscopy to measure the fluorescence intensity of the calcium-sensitive indicator, fluo-4. High concentrations of intracellular calcium are indicated in yellow and orange.

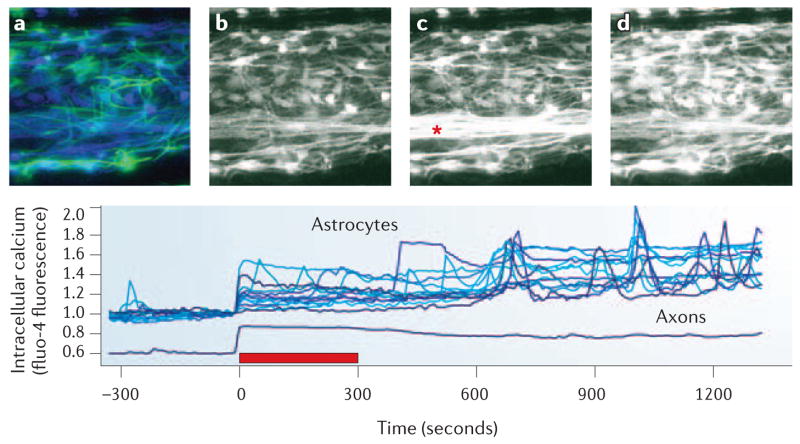

Activity-dependent neuron–glia communication by purinergic signalling was found to extend beyond synapses when it was shown that axons firing bursts of action potentials release adenosine and ATP28–30. Calcium imaging in glia revealed that purinergic receptors allow premyelinating Schwann cells30, oligodendrocytes31 and astrocytes (FIG. 4) to detect action potential firing.

Figure 4. Calcium imaging reveals that glial cells can respond to electrical activity in axons.

Impulse activity causes the release of ATP and other neurotransmitters from synapses and axons. This, in turn, activates membrane receptors on several types of glia, triggering increases in intracellular calcium concentration. Intracellular calcium responses in rat astrocytes are shown in response to 10 Hz of electrical stimulation of dorsal root ganglion axons (*) in co-culture. Increasing concentrations of intracellular calcium are indicated by increased fluorescence intensity of the calcium indicator, fluo-4. a | Immunocytochemical staining for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, green), a cytoskeletal protein expressed in astrocytes, is shown superimposed on the same field used for live-cell calcium imaging (blue). Not all astrocytes express GFAP at high levels at this stage (48 h in co-culture). b–d | Represent calcium imaging taken from cells at −300 s (b), 20 s (c) and 630 s (d) with respect to the 5 min train of 10 Hz action potentials (red bar in plot). The changes in the intracellular calcium concentrations in astrocytes as a result of neuronal firing are shown in the graph (bottom panel). There are no synapses in these cultures. For methods, see REF. 30. Note that intracellular calcium values in axons have been displaced by 0.4 to better distinguish axon responses from astrocyte responses in the plot. See also online Supplementary information S1 (movie).

ATP release from axons, dendrites and cell bodies of neurons, and from glia, by membrane channels and other mechanisms further expands the potential functional significance of purinergic signalling in the brain. In addition to its rapid neurotransmitter-like action in intracellular signalling in neurons and glia, it is evident that ATP can also act as a growth and trophic factor32,33, altering the development of neurons34 and glia30–35 by regulating the two most important second messengers: cytoplasmic calcium and cAMP. Moreover, the release of ATP by neural impulse activity provides a mechanism linking functional activity in neural circuits to the growth and differentiation of nervous system cells. How development is regulated by changes in expression of purinergic receptors and ecto-enzymes controlling ATP availability is only beginning to be explored.

Microglia, the highly dynamic immune cells of the nervous system, respond to a wide range of ATP receptor agonists through increases in intracellular calcium36, the triggering of potassium currents37, and secretion of cytokines38 and plasminogen39. Rapid changes in morphology40 and migration41 are induced in microglia by purinergic receptor activation.

Tetanus toxin

Protein derived from Clostridium tetani that can block transmitter release owing to its ability to degrade synaptobrevin. Tetanus toxin is the causative agent of tetanus.

The most pivotal finding in research on neuron–glia interactions was the discovery of glia–glia communication via ATP42,43. This finding came from calcium imaging studies that showed calcium waves propagating among astrocytes (FIG. 3) across a cell-free barrier in culture, demonstrating that glia–glia communication is mediated, in part, by the release of intercellular signalling molecules rather than by the passage of cell–cell signalling molecules through gap junctions connecting adjacent cells44. Release of ATP from astrocytes was visualized using a luciferase fluorescence assay in parallel with increased intracellular calcium45; calcium-wave propagation could be inhibited by purinergic receptor blockers or an enzyme, apyrase, that rapidly degrades extracellular ATP46. The cytoplasmic calcium increase stimulated by ATP receptor activation, in turn, stimulates the release of glutamate and other signalling molecules from astrocytes to propagate the calcium wave to other cells47. Similar intercellular calcium waves in astrocytes mediated by ATP release have been observed in retinal explants48 and brain slices49.

This finding indicated a mechanism that could, in theory, enable glia to detect synaptic function, propagate the information through chains of glial cells, and then influence synaptic function at remote sites. In effect, glia–glia communication could provide a parallel system of intercellular communication in the brain, operating in concert with neurons but acting through an entirely distinct mechanism. Furthermore, widespread propagation of calcium waves through astrocytes in the intact brain appears to be particularly important in pathological states, such as seizure, and in brain trauma; more physiological stimulation tends to activate more discrete signalling among fewer astrocytes50.

ATP release and degradation

There is clear evidence for exocytotic vesicular release of ATP from nerves, and the concentration of these nucleotides in vesicles is claimed to be up to 1000 mM. It was generally assumed that the main sources of ATP acting on purinoceptors were damaged or dying cells. However, it is now recognized that ATP release from many cells is a physiological or pathophysiological response to mechanical stress, hypoxia, inflammation and some agonists51. There is debate, however, about the ATP transport mechanisms involved52. There is compelling evidence for exocytotic release from endothelial and urothelial cells, osteoblasts, astrocytes, and mast and chromaffin cells, but other transport mechanisms have also been proposed. These include ATP binding cassette transporters, connexin hemichannels and plasmalemmal voltage-dependent anion channels.

There is evidence for multiple pathways for ATP release from glial cells. Synaptic vesicle release proteins have been detected in astrocytes53, and interfering with their function using genetic54 or pharmacological55 methods inhibits ATP release. Vesicular release of ATP from astrocytes is less impaired by tetanus toxin, which cleaves synaptobrevin (a synaptic vesicle release protein), and more weakly induced by metabotropic glutamate receptor activation, suggesting possible differences in the vesicles that store ATP and glutamate55. Transfecting a glial cell line with the gap junction proteins connexin 43, 32 or 26 increases ATP release and intercellular calcium wave propagation43, suggesting that the gap junction proteins that are unpaired with those in adjacent cells (hemichannels) could release ATP. However, altering expression of connexins can alter P2Y purinergic receptor expression in astrocytes56, which could also affect calcium wave propagation, and many gap junction channel blockers are antagonists of the P2X7 receptor57. Other evidence supports a mechanism of ATP release from astrocytes through membrane channels with a large diameter pore, such as the P2X7 receptor, contributing to intercellular calcium waves58. ATP is also released from astrocytes during cell swelling59, implicating membrane channels that are involved in osmoregulation or activated by membrane stretch.

There is also growing evidence for the release of ATP from multiple sites in skeletal muscle. As in all tissues, muscle fibre damage results in the passive release of ATP and other nucleotides from cells. In addition, significant quantities of ATP are co-released with acetylcholine from motor nerve terminals on nerve activation14, and might be released from muscle fibres during contraction or from Schwann cells. Therefore, skeletal muscle, particularly after injury, would be expected to contain high levels of extracellular ATP. These findings suggest that purinergic signalling might have a significant role not only in skeletal muscle formation but also in muscle regeneration60.

Much is now known about the ectonucleotidases that break down the ATP released from neurons and non-neuronal cells61 (FIG. 1). Several enzyme families are involved: ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases (E-NTPDases), of which NTPDase1, 2, 3 and 8 are extracellular; ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase (E-NPP), which has 3 subtypes; alkaline phosphatases; ecto-5′-nucleotidase and ectonucleoside diphosphokinase (E-NDPK). NTPDase1 hydrolyses ATP directly to AMP, and UTP to UDP, whereas NTPDase2 hydrolyses ATP to ADP, and 5′-nucleotidase AMP to adenosine. These enzymes have a wide and potentially overlapping tissue distribution. In the brain, members of all ectonucleotidase families are expressed. In the nervous system, enzymes for the hydrolysis of 5′-mononucleotides reside primarily on glia, including astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia and Schwann cells, as well as on endothelia and ependyma62. These enzymes are involved in the modulation of synaptic transmission, ATP-mediated propagation of glial cell calcium waves, microglial function, adult neurogenesis and control of vascular tone. So far, NTPDase1, nucleotide pyrophosphatase phosphodiesterase (NPP1) and ecto-5′ nucleotidase and two isoforms of alkaline phosphatase have been deleted in mice, which should give further insights into the physiological roles of these ectonucleotidases; however, the development of selective inhibitors for the different enzymes is much needed.

Purinergic receptors

Separate families of receptors for adenosine (P1 receptors) and for ATP and ADP (P2 receptors) were proposed in 1978 (REF. 63). Concurrent with this, two subtypes of the P1 receptor were recognized64. However, the existence of two types of P2 receptor (P2X and P2Y) was not proposed until 1985 (REF. 65). Several other P2 receptors were discovered in the following years, and, to simplify matters, Abbracchio and Burnstock66 proposed that P2 receptors should belong to two main families: a P2X family of ligand-gated ion channel receptors, and a P2Y family of G-protein-coupled receptors. This division was made on the basis of transduction mechanism studies67 and the cloning of nucleotide receptors68–71. The nomenclature has been officially adopted by the International Union of Pharmacology subcommittee for purinergic receptor nomenclature and classification, and is now used by all researchers in the field. At present, seven P2X and eight P2Y receptor subtypes are recognized, including receptors that are sensitive to pyrimidines as well as to purines, and sugar nucleotides such as UDPglucose and UDPgalactose72,73.

The field is rapidly expanding, and it is clear that receptors for purines and pyrimidines are widely distributed not only in the nervous system, but also in many non-neuronal cells25. Both short-term purinergic signalling (found in neurotransmission, neuromodulation, exocrine and endocrine secretion, platelet aggregation, vascular endothelial cell-mediated vasodilatation, and nociceptive mechanosensory transduction) and long-term (trophic) purinergic signalling (involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, migration and death in embryological development, neural regeneration, cell turnover of epithelial cells in skin and visceral organs, wound healing, ageing and cancer) have been described25.

P2Y receptors

The metabotropic P2Y receptor sub-types (P2Y1,2,4,6,11–14; FIG. 2c) have a characteristic subunit topology of an extracellular amino (N) terminus and an intracellular carboxyl (C) terminus. The latter has consensus-binding motifs for protein kinases, seven transmembrane (TM)-spanning regions, which help to form the ligand docking pocket, and a high level of sequence homology between some TM-spanning regions, in particular TM3, TM6 and TM7. The intracellular loops and C terminus have structural diversity among P2Y subtypes, thereby influencing the degree of coupling with Gq/11, Gs and Gi proteins74. Under certain conditions, P2Y receptors might form homo- and heteromultimeric assemblies, and many tissues express several P2Y subtypes. P2Y1, P2Y12 and P2Y13 receptors are activated principally by nucleoside diphosphates, whereas P2Y2, P2Y4 and P2Y6 receptors are activated by both purine and pyrimidine nucleotides. In response to nucleotide activation, recombinant P2Y receptors either activate PLC and release intracellular calcium, or affect adenylyl cyclase and alter cAMP levels. To date, there is insufficient evidence to indicate that P2Y5, P2Y9 and P2Y10 are nucleotide receptors, or that they affect intracellular signalling cascades, although P2Y7 has been shown to be a leukotriene receptor75. P2Y8 is a receptor cloned from frog embryos at a developmental stage at which all nucleotides are equipotent76, but, with one exception, no mammalian homologue has been identified so far — P2Y8 mRNA in undifferentiated HL60 cells (a human leukaemia cell line) has been reported77. P2Y11 signalling is unusual in that it can activate two transduction pathways — adenylate cyclase, as well as Ins(1,4,5)P3, which is the second messenger system used by most of the P2Y receptors. The P2Y12 receptor found on platelets was not cloned until more recently78, although it has only 19% homology with the other P2Y receptor subtypes. This receptor, together with P2Y13 and P2Y14, might represent a subgroup of P2Y receptors for which transduction is entirely through adenylate cyclase73. A receptor on C6 glioma cells, and possibly a receptor in the midbrain, both of which are selective for diadenosine polyphosphate, might also operate through adenylate cyclase. Selective and non-selective agonists and antagonists to the P2Y receptor subtypes are summarized in TABLE 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of purine-mediated receptors

| Receptor | Main distribution | Agonists | Antagonists | Transduction mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 (adenosine) | ||||

| A1 | Brain, spinal cord, testes, heart, autonomic nerve terminals | CCPA, CPA, S-ENBA | DPCPX, N-0840, MRS1754 | Gi/o ↓cAMP |

| A2A | Brain, heart, lungs, spleen | CGS 21680, HENECA | KF17837, SCH58261, ZM241385 | GS ↑cAMP |

| A2B | Large intestine, bladder | NECA (non-selective) | Enprofylline, MRE2029-F20, MRS17541, MRS 1706 | GS ↑cAMP |

| A3 | Lungs, liver, brain, testes, heart | IB-MECA, 2-Cl-IB-MECA, DBXRM, VT160 | MRS1220, L-268605, MRS1191, MRS1523, VUF8504 | Gi/o Gq/11 ↓cAMP ↑Ins(1,4,5)P3 |

| P2X | ||||

| P2X1 | Smooth muscle, platelets, cerebellum, spinal neurons in the dorsal horn | α,β-meATP = ATP= 2-MeSATP (rapid desensitization), L-β,γ-meATP | TNP-ATP, IP5I, NF023, NF449 | Intrinsic cation channel (calcium and sodium) |

| P2X2 | Smooth muscle cells, CNS, retinae, chromaffin cells, autonomic and sensory ganglia | ATP ≥ ATPγS ≥ 2-MeSATP≫ α,β-meATP (pH and zinc sensitive) | Suramin, isoPPADS, RB2, NF770 | Intrinsic ion channel (particularly calcium) |

| P2X3 | Sensory neurons, NTS, some sympathetic neurons | 2-MeSATP ≥ ATP ≥ α,β-meATP ≥ Ap4A (rapid desensitization) | TNP-ATP, PPADS, A317491, NF110 | Intrinsic cation channel |

| P2X4 | CNS, testes, colon | ATP ≫ α,β-meATP, CTP, ivermectin | TNP-ATP (weak), BBG (weak) | Intrinsic ion channel (especially calcium) |

| P2X5 | Proliferating cells in skin, gut, bladder, thymus and spinal cord | ATP ≫ α,β-meATP, ATPγS | Suramin, PPADS, BBG | Intrinsic ion channel |

| P2X6 | CNS, motor neurons in spinal cord | N/A (does not function as homomultimer) | N/A | Intrinsic ion channel |

| P2X7 | Apoptotic cells in, for example, immune cells, pancreas, skin | BzATP > ATP ≥ 2-MeSATP ≫α,β-meATP | KN62, KN04, MRS2427, Coomassie BBG | Intrinsic cation channel and a large pore with prolonged activation |

| P2Y | ||||

| P2Y1 | Epithelial and endothelial cells, platelets, immune cells, osteoclasts | 2-MeSADP = ADPβS >2-MeSATP = ADP > ATP, MRS2365 | MRS2179, MRS2500, MRS2279, PIT | Gq/G11; PLCβ activation |

| P2Y2 | Immune cells, epithelial and endothelial cells, kidney tubules, osteoblasts | UTP = ATP, UTPγS, INS 37217 | Suramin > RB2, AR-C126313 | Gq/G11 and possibly Gi; PLCβ activation |

| P2Y4 | Endothelial cells | UTP ≥ ATP, UTPγS | RB2 > suramin | Gq/G11 and possibly Gi; PLCβ activation |

| P2Y6 | Some epithelial cells, placenta, T cells, thymus | UDP > UTP ≫ ATP, UDPβS | MRS2578 | Gq/G11; PLCβ activation |

| P2Y11 | Spleen, intestine, granulocytes | AR-C67085MX > BzATP ≥ ATPγS > ATP | Suramin > RB2, NF157 | Gq/G11 and GS; PLCβ activation |

| P2Y12 | Platelets, glial cells | 2-MeSADP ≥ ADP ≫ ATP | CT50547, AR-C69931MX, INS49266, AZD6140, PSB0413, ARL66096 | Gi/o; inhibition of adenylate cyclase |

| P2Y13 | Spleen, brain, lymph nodes, bone marrow | ADP = 2-MeSADP ≫ ATP and 2-MeSATP | MRS2211 | Gi/o |

| P2Y14 | Placenta, adipose tissue, stomach, intestine, discrete brain regions | UDP glucose = UDP-galactose | N/A | Gq/G11 |

BBG, Brilliant blue green; BzATP, 2′- and 3′-O-(4-benzoyl-benzoyl)-ATP; cAMP, cyclic AMP; CCPA, chlorocyclopentyl adenosine; CPA, cyclopentyl adenosine; CTP, cytosine triphosphate; Ins(1,4,5)P3, inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate; Ip5I, di-inosine pentaphosphate; 2-MeSADP, 2-methylthio ADP; 2-MeSATP, 2-methylthio ATP; NECA, 5′-N-ethyl-carboxamido adenosine; NTS, nucleus tractus solaritus; PLC, phospholipase C; RB2, reactive blue 2. Table modified, with permission, from REF. 168 © (2003) Elsevier Science.

Adenylyl cyclase

An enzyme that synthesizes cAMP, a second messenger molecule that relays signals received from receptors on the cell surface to intracellular signalling pathways.

Diadenosine polyphosphate

A phosphorylated form of adenosine dinucleotide, which is released from neurosecretory vesicles together with ATP.

P2X receptors

Members of the family of ionotropic P2X1–7 receptors show a subunit topology of intracellular N and C termini that have consensus-binding motifs for protein kinases; two TM-spanning regions, the first (TM1) being involved with channel gating and the second (TM2) lining the ion pore; a large extracellular loop with 10 conserved cysteine residues forming a series of disulphide bridges; a hydrophobic H5 region close to the pore vestibule, for possible receptor/channel modulation by cations; and an ATP-binding site, which might involve regions of the extracellular loop adjacent to TM1 and TM2 (FIG. 2b). The P2X1–7 receptors show 30–50% sequence identity at the peptide level. The stoichiometry of P2X1–7 receptors is thought to involve three subunits that form a stretched trimer79.

The pharmacology of the recombinant P2X receptor subtypes expressed in oocytes and other cell types has significant differences when compared with the pharmacology of P2X receptor-mediated responses at naturally occurring sites. There are several contributing factors that might explain these differences. First, the trimer ion pore might form heteromultimers as well as homomultimers72,80. For example, heteromultimers of P2X2 and P2X3 receptor subtypes (P2X2/3) are clearly established in nodose ganglia, P2X4/6 in CNS neurons, P2X1/5 in some blood vessels and P2X2/6 in the brainstem. P2X7 does not form heteromultimers, and P2X6 does not form a functional homomultimer. Second, spliced variants of P2X receptor subtypes might be a contributing factor. For example, a splice variant of the P2X4 receptor, although non-functional on its own, can potentiate the actions of ATP through the full-length P2X4 receptors81. Third, the presence of powerful ecto-enzymes that rapidly break down purines and pyrimidines in native tissues is not a factor when examining recombinant receptors82.

P1 Receptors

The adenosine/P1 receptor family comprises the A1, A2A, A2B and A3 adenosine receptors, which were identified by convergent data from molecular, biochemical and pharmacological studies83,84. Receptors from each of these four distinct subtypes have been cloned from various species, and characterized following functional expression in mammalian cells or Xenopus oocytes.

All adenosine receptors couple to G proteins. In common with other G-protein-coupled receptors, they have seven putative TM domains of hydrophobic amino acids. The N-terminal of the protein lies on the extracellular side and the C-terminal on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane (FIG. 2a). The transmembrane regions are generally highly conserved. Selective agonists and antagonists for all four P1 receptor subtypes are summarised in TABLE 2.

The most widely recognized signalling pathway of A1 receptors is the inhibition of adenylate cyclase, which causes a decrease in the second messenger cAMP. A1 receptors are widely distributed in most species, and mediate diverse biological effects. They are dominant in the CNS, where they mediate prejunctional inhibition of transmitter release. High levels are expressed in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum, thalamus, brainstem and spinal cord. A1 receptors have been implicated in sedative, anticonvulsant, anxiolytic and locomotor depressant effects85.

The most well-known signal transduction mechanism for A2A receptors is the activation of adenylate cyclase. A2A receptors have a wide-ranging distribution that includes immune tissues, platelets, the CNS, and vascular smooth muscle and endothelium. In the brain, the highest levels of A2A receptors are in the striatum, nucleus accumbens and olfactory tubercle (regions that are rich in dopamine). A2A receptors in the CNS and particularly in the PNS generally facilitate neurotransmitter release. The observation of negative interactions between A2A and dopamine D2 receptors raises the possibility of using A2A receptor antagonists as a new therapeutic approach in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease85.

A2B receptors have been cloned from the human hippocampus, rat brain and mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells. A2B-receptor coupling to different signalling pathways has been reported, including the activation of adenylate cyclase, Gq/G11-mediated coupling to PLC, and Ins(1,4,5)P3-dependent increase in intracellular calcium concentration (in human mast cells). A2B receptors are found on almost every cell in most species. However, selective agonists are still not available, which limits our knowledge of the biological effects of this type of receptor.

A3, the fourth distinct adenosine receptor, was identified relatively late in the history of adenosine/P1 receptors by the cloning, expression and functional characterization of a newly identified adenosine receptor from rat striatum. The A3 receptor is G-protein-linked, coupling to Giα2, Giα3 and, to a lesser extent, to Gq/11 proteins. In rat basophilic leukaemia cells and in the rat brain, the A3 receptor stimulates PLC and elevates Ins(1,4,5)P3 levels and intracellular calcium concentration. The A3 receptor has also been shown to inhibit adenylate cyclase activity. It is widely distributed, but its physiological roles are not fully known.

A1, A2A, A2B and A3 adenosine receptors have distinct but frequently overlapping tissue distributions. The fact that more than one adenosine/P1 receptor subtype might be expressed by the same cell raises questions about the functional significance of this co-localization. The extracellular adenosine concentration might be a crucial determinant of the differential activation of coexisting adenosine/P1 receptors under pathophysiological as well as physiological conditions. For example, low concentrations of adenosine activate the A1 receptor expressed on neutrophils, whereas high concentrations of adenosine, acting on A2 receptors, inhibit the effects produced by A1 occupancy. A2A and A2B receptors coexist on fetal chick heart cells; the high affinity A2A receptor is a modulator of myocyte contractility under physiological conditions, whereas under pathophysiological conditions — such as cardiac ischaemia resulting in the release of large amounts of adenosine — the low affinity A2B receptor may assume functional significance.

Expression of purinergic receptors in neurons, glia and muscle

Most P2X receptors and some P2Y receptor subtypes are expressed on neurons in the CNS5,86. P2X2, P2X4 and P2X6 receptors are widespread and often form heteromultimers. Some P2X receptors are found in other regions — for example P2X1 receptors in the cerebellum, and P2X3 receptors in the brainstem. P2X7 receptors are probably largely pre-junctional. P2Y1 receptors are also abundant and widespread in the brain. The hippocampus expresses all P2X receptor subtypes, P2Y1,2,4,6 receptors, and the cortex expresses the P2Y13, P2Y1 and P2X2 receptors. Electron microscopic immunohistochemistry allows us to distinguish the localization of P2 receptors at pre- and postsynaptic sites, as well as on glial cells.

Multiple P2 receptor subtypes are expressed by glial cells87 (TABLE 1), and P2 receptors expressed by oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells have been implicated in myelination30,31. All four adenosine receptors are detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from the mouse forebrain31. In addition, A2A receptors have been identified in mouse Schwann cells and shown to inhibit cell proliferation88. Astrocytes and microglia express many purinergic receptors, but, as with myelinating glia, the patterns of expression are complex and can change with physiological and developmental state. Many glial cells co-express various types of P1 and P2 receptor, but there can be considerable heterogeneity in expression patterns among individual cells.

The expression of purinoceptors during skeletal muscle cell development is well established. Responses characteristic of P2 receptor activation have been detected on myoblasts and myotubes cultured from embryonic chick muscle and C2C12 myoblasts89. More recently, the expression of specific P2X and P2Y receptor subtypes during skeletal muscle development has been demonstrated. P2Y1, P2X5 and P2X6 are expressed in chick skeletal muscle development, and expression of the P2X2, P2X5, P2X6, P2Y1, P2Y2 and P2Y4 receptors has been shown in rat skeletal muscle development90. Whereas the P2Y1 receptor has been implicated in the regulation of acetylcholine receptors and acetylcholinesterase expression91, a role for the P2X5 receptor in the regulation of myoblast activity and differentiation has been demonstrated92. In vitro experiments show that activation of the P2X5 receptor by ATP (but not adenosine, ADP or UTP) results in a shift in the balance between myoblast proliferation and differentiation. Rat skeletal satellite cells (in primary culture) exposed to ATP have a reduced rate of proliferation, but express markers of differentiation.

In summary, experimental evidence suggests a role for purines and pyrimidines in both glial and microglial function. These molecules are able to induce markedly different actions such as mitogenesis and apoptosis, depending on the functional state of these cells, the expression of selective receptor subtypes and the presence of different receptors on the same cells.

Direct regulation of synaptic transmission

Both ATP and adenosine receptor activation can exert bidirectional control of synaptic transmission in the hippocampus and at other synapses of the CNS and PNS. ATP receptor activation can stimulate or inhibit glutamate release from rat hippocampal neurons, and ATP release has been implicated in hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP)93. P2X1, P2X2/3 and P2X3 receptors can act presynaptically to facilitate glutamate release, and P2Y1, P2Y2 and P2Y4 receptor activation can inhibit release from hippocampal neurons94. P2 receptor activation can also trigger adenosine release, and, by the subsequent activation of A2A receptors, can indirectly facilitate LTP induction in the rat hippocampus95.

Adenosine can either facilitate or inhibit synaptic transmission in the hippocampus by acting on A1or A2A receptors, respectively96, and both receptors are frequently co-expressed in single hippocampal pyramidal neurons97. A1 receptor activation can inhibit the release of acetylcholine98,99 and glutamate100. At mossy fibre synapses, adenosine activation of presynaptic A1 receptors decreases transmitter release by more than 75%96,101. Conversely, A2A receptor stimulation can stimulate the release of glutamate from rat hippocampal neurons102, and increase GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) release from hippocampal interneurons103. Modulatory effects of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) activation on pyramidal neurons occur through A2A receptors co-localized with mGluR5 at CA1 hippocampal synapses104.

ATP and adenosine signalling are highly interrelated in hippocampal synaptic function, through interactive effects on purine release, activity of ecto-enzymes, nucleoside transporters and different receptor subtypes stimulating opposing second messenger systems. For example, the release of ATP from hippocampal neurons is promoted by high-frequency stimulation, but accumulation of adenosine predominates during prolonged low-frequency stimulation105. Also, ATP can inhibit ecto-5′-nucleotidase activity in the hippocampus, allowing the burst-like formation of adenosine, which, in turn, facilitates glutamate release by A2A receptor activation on presynaptic terminals106. Furthermore, activation of A2A receptors can facilitate nucleoside transporters, thereby promoting the clearance of adenosine from the extracellular space107. Lee and Chao108 have shown that purinergic signalling interacts with neurotrophin signalling by transactivating the receptor tyrosine kinases TrkA and TrkB via A2A receptor stimulation. Activation of the A2A receptor has been reported to underlie the mechanism of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) facilitation of hippocampal LTP109.

Regulation of synaptic transmission through glia

The well-established function of glial cells in supporting neurons provides them with effective mechanisms for modulating neuronal communication110. Glia help to maintain extracellular ion homeostasis, clear neurotransmitter from the synaptic cleft using membrane transporters, provide molecular substrates for neuronal energy requirements and neurotransmitter synthesis, and release a myriad of neuromodulatory molecules — from growth factors to cytokines — in addition to ATP and adenosine. This allows glial cells to regulate the information flow through neural networks in the retina111, CNS54,112 and at synaptic junctions with muscle113.

Purinergic signalling facilitates glial intervention in synaptic transmission through ATP-mediated intercellular communication, and the involvement of ATP in regulating synaptic transmission through purinergic receptors on the pre- and postsynaptic membranes. Purinergic signalling also interacts with other intercellular signalling molecules (notably neurotransmitters and trophic factors), and second messenger systems (notably calcium and cAMP) that are key regulators of synaptic function and plasticity.

Astrocytes in hippocampal synaptic plasticity

Focal electric field stimulation applied to a single astrocyte in mixed cultures of rat forebrain astrocytes and neurons causes a prompt elevation of calcium in the astrocyte that propagates from cell to cell114,115. Neurons associated with these astrocytes respond with large increases in cytosolic calcium concentration, and similar effects are seen in brain slices50,116. By acting on different types of metabotropic glutamate receptor, glutamate released from astrocytes can stimulate117,118 or inhibit119 synaptic transmission through hippocampal inhibitory interneurons. Adenosine receptor activation modulates astrocyte calcium fluxes in situ4, suggesting the involvement of both P1 and P2 receptors in glial regulation of synaptic transmission.

Astrocytes affect both excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission in the hippocampus through purinergic signalling. ATP application or the electrical stimulation of the Schaffer collaterals causes a rise in cytoplasmic calcium concentration in hippocampal astrocytes. These then release ATP, which activates inhibitory interneurons to increase synaptic inhibition120. Both the calcium response in astrocytes and the activation of interneurons are blocked by P2Y1 receptor antagonists. ATP released by astrocytes can also mediate glutamatergic activity-dependent heterosynaptic suppression by acting on P2Y receptors — an effect that can also be mediated by adenosine produced from ATP degradation121.

Heterosynaptic long-term depression (LTD) in the hippocampus, a phenomenon known to be regulated by adenosine but previously assumed to be exclusively neuronal, has recently been shown to involve purinergic astrocyte–neuron signalling. By selectively blocking ATP release from astrocytes, Pascuale et al.54 showed that adenosine, produced by the hydrolysis of ATP released from astrocytes, mediates heterosynaptic LTD by the activation of A1 receptors on presynaptic terminals of CA1 hippocampal neurons.

Hypothalamic astrocytes

The strength of excitatory synapses in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus is regulated by astrocytes through their effects on neuronal P2X7 receptors112. Noradrenaline from nerve terminals induces the release of ATP from astrocytes, which activates P2X7 receptors in the postsynaptic membrane of magnocellular neurosecretory neurons, thereby increasing synaptic efficacy by promoting the insertion of AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid) receptors into the postsynaptic membrane112. These astrocytes undergo anatomical changes, such as the withdrawal of processes ensheathing the axon terminals, under physiological states such as dehydration, parturition and lactation122,123. When the glial processes are retracted from synaptic contacts following dehydration, noradrenaline no longer affects synaptic strength through purinergic mechanisms. This morphological remodelling of the synapse also affects transmission by altering the accessibility of transporters on perisynaptic astrocytes, and by neuromodulatory substances such as taurine, D-serine and glutamate released by these glial cells124.

Retinal glia

In the retina, endogenous purines are released by potassium depolarization125 and by light stimulation126. The firing rate of retinal neurons is affected by the passage of a glial calcium wave127 through a mechanism requiring the release of ATP and adenosine from neurons126. ATP released by astrocytes can inhibit neuronal transmission by being hydrolysed to adenosine, and then activating A1receptors on retinal ganglion cells128. Increases in synaptic transmission can result in glial cell calcium waves through the release of D-serine, a co-agonist of the postsynaptic NMDA (N-methyl-3-aspartate) receptors129, but several other gliotransmitters are involved in pre- and postsynaptic regulation of synaptic transmission in the retina130.

Schwann cells at the neuromuscular junction

Early studies of ATP and adenosine signalling between synapses and perisynaptic glia were carried out at the neuromuscular junction. Specialized Schwann cells (known as terminal Schwann cells) tightly surround the neuromuscular junction and actively participate in the maintenance and repair of neuromuscular synapses131. These Schwann cells respond to nerve stimulation and modulate transmitter release through mechanisms involving ATP and adenosine signalling. Tetanic stimulation of the motor nerve axon elicits rapid calcium transients in the terminal Schwann cells of frogs132 and mice133, and similar responses can be induced by agonists of P2X, P2Y and A1 receptors27,134. Suramin, a non-selective antagonist of P2 receptors, blocks ~87% of the glial calcium response following high-frequency nervous stimulation in frogs27. In mice, the adenosine A1 receptors are one of the main means of activating calcium responses in terminal Schwann cells in response to nerve stimulation (for a review, see REF. 135).

Regulation of myelination by axon potential

Myelin, the insulating layers of membrane wrapped around axons by oligodendrocytes in the CNS and by Schwann cells in the PNS, is essential for normal impulse conduction. Myelination occurs during the late stages of fetal development but, curiously, continues into early adult life. Evidence from animal studies, cell culture and human brain imaging indicates that action potentials affect myelination136,137. In addition, raising animals in environments with enriched sensory stimulation and social interaction increases CNS myelination138, and children suffering neglect or abuse show decreased white matter in the corpus callosum139. These observations suggest that myelinating glia are in some way party to the flow of information through neural circuits, and that this might be an overlooked form of plasticity that modifies the nervous system according to functional requirements136,138.

In contrast to perisynaptic glia, which can detect neurotransmitter escaping the synaptic cleft, activity-dependent communication between axons and myelinating glia occurs in the absence of synapses. Studies showing that ATP is released from axons firing trains of action potentials have revealed that purinergic signalling can enable premyelinating glia to respond to impulse activity in axons, with effects on myelination30. Calcium responses in Schwann cells are blocked by the electrical stimulation of axons in the presence of apyrase, an enzyme that rapidly degrades extracellular ATP30, but responses are only partially blocked in oligodendrocytes31. This is consistent with the fact that different purinergic receptors are expressed in these two cell types. For example, oligodendrocytes have all four adenosine receptors31, whereas no adenosine receptors coupled to intracellular calcium are detected in premyelinating Schwann cells. A2A receptors have recently been detected in Schwann cells, and were found to inhibit proliferation through a different mechanism from the P2 receptor88.

Differences in purinergic receptors allow differential responses to impulse activity in peripheral and central myelinating glia on axons of the same dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neuron140. Impulse activity, acting through the activation of P2 receptors by ATP, inhibits Schwann cell proliferation, differentiation and myelination30. However, impulse activity has the opposite effect on oligodendrocytes, stimulating differentiation of oligodendrocytes from the progenitor stage, and promoting myelination through adenosine (P1) receptor activation.

More recently, purinergic signalling has been found to stimulate myelination by more mature oligodendrocytes through a mechanism involving astrocytes. The cytokine leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF) is secreted by astrocytes in response to ATP released from axons firing action potentials. LIF, in turn, stimulates oligodendrocytes to form myelin141. This involvement of astrocytes in myelination might explain the puzzling white matter defects seen in Alexander disease, a genetic mutation that affects astrocytes.

Response to injury, inflammation and pain

Cellular damage can result in the release of large amounts of ATP into the extracellular environment, because intracellular concentrations can reach 3–5 mM18. Such ATP release might be important in triggering cellular responses to trauma and ischaemia. Nucleosides and nucleotides released from dying cells might induce reactive astrogliosis, which involves striking changes in astrocyte proliferation and morphology142,143. ATP stimulates proliferation of microglia (for a review, see REF. 144) and acts as a powerful chemoattractant to the site of brain injury41.

Cell proliferation

Both adenosine and ATP induce astroglial cell proliferation and the formation of reactive astrocytes, as demonstrated by the increased expression of the astroglial-specific marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and the elongation of GFAP-positive processes145. The blockade of A2A receptors prevents basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF)-induced reactive astrogliosis in rat striatal primary astrocytes146.

Interactions between purinergic receptors and growth factor receptors can be synergistic, as in astrocytes35, or antagonistic, as in Schwann cells147. It has been suggested that, through the activation of distinct membrane receptors, ATP and bFGF signals merge at the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade, and that this integration might underlie the synergistic interactions of ATP and bFGF in astrocytes145.

The release of cytokines and growth factors can be affected by purinergic receptors, and can influence cell proliferation. Activation of A2 receptors enhances the release of nerve growth factor (NGF) and S100-β protein from cultured astrocytes148, and A2A receptor stimulation potentiates nitric oxide release by activated microglia149. Activation of P2X7 receptors induces GABA release from an astrocyte cell line150; the release of ATP and neurotransmitter from astrocytes is mentioned above.

The transactivation of neurotrophin receptors by purinergic receptors adds an activity-dependent aspect to the function of growth factors in controlling interactions between neurons and glia. A2A receptor activation activates TrkA in PC12 cells and TrkB in hippocampal neurons, preventing cell death after NGF or BDNF withdrawal108. Recently, P2Y2 receptors have been shown to activate NGF TrkA signalling in DRG neurons to enhance neurite outgrowth151.

Neuroprotection and pathophysiology

Some of the responses to ATP released during brain injury are neuroprotective, but in some circumstances ATP contributes to the pathophysiology initiated after trauma152. Activation of adenosine A2B receptors in astroglioma cells has been shown to increase interleukin-6 (IL-6) mRNA and IL-6 protein synthesis. P2Y receptors mediate reactive astrogliosis through induction of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2)153. The results of recent experiments suggest that astrocytes can sense the severity of damage in the CNS by the amount of ATP released from damaged cells, and can modulate the tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα)-mediated inflammatory response depending on the extracellular ATP concentration and subtype of astrocytic P2 receptor activated154. ATP can activate P2X7 receptors in astrocytes to release glutamate, GABA and ATP, which might regulate the excitability of neurons in certain pathological conditions150. Adenosine can be neuroprotective; for example, depression of synaptic transmission in the hippocampus during hypoxia is alleviated by A1 receptor agonists155.

Neuroimmune interactions

Microglia, the immune cells of the CNS, are also activated by purines and pyrimidines to release inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα. P2X7receptors mediate superoxide production in primary microglia, and are unregulated in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease, particularly around amyloid-β plaques156. Stimulation of microglial P2X7 receptors also leads to enhancement of interferon-γ (IFNγ)-induced type II nitric oxide synthase activity157. The roles of microglia in inflammatory pain have attracted strong interest during the past few years. ATP selectively suppresses the synthesis of the inflammatory protein microglial response factor through calcium influx via P2X7 receptors in microglia158. ATP, ADP and benzoyl-benzoyl ATP, acting through P2X7 receptors, induce the release of IL-1β from microglial cells159. Activation of P2X7 receptors enhances IFNγ-induced nitric oxide synthase activity in microglial cells, and might contribute to inflammatory responses. ATP, through P2X7 receptors, increases the production of 2-arachidonoylglycerol, which is also involved in inflammation by microglial cells. Finally, it has been shown that pharmacological blockade of P2X4 receptors or administration of P2X4 antisense oligodeoxynucleotide reverses tactile allodynia caused by peripheral nerve injury160.

Neurological disorders

Several antiepileptic agents reduce the ability of astrocytes to transmit calcium waves, raising the possibility that intercellular calcium wave blockade in astrocytes by purinergic receptor antagonists could offer new treatments for epileptic disorders. Adenosine controls hyperexcitability and epileptogenesis161, and release of glutamate from astrocytes has been implicated in epileptogenesis162. The A2A receptor has also become a promising target for treating Parkinson’s disease (for a review, see REF. 163).

ATP contributes to the neurovascular changes responsible for pain associated with migraine headaches164. Intracellular calcium waves can propagate between pia-arachnoid cells and astrocytes, and this can be blocked by octanol or apyrase, indicating the involvement of gap junction communication and extracellular ATP. P2Y2 and P2Y4 receptors are strongly expressed in glial endfeet apposed to blood vessel walls165. Presumably, activation of these receptors by ATP participates in regulating either the blood–brain barrier, blood flow, metabolic trafficking or water homeostasis165,166.

Conclusions and future perspectives

Coordinating the wide variety of cells in the nervous system requires some means of intercellular communication that can integrate vascular, glial, immune and neural elements into a dynamic but highly regulated system. More than any other molecule, extracellular ATP meets this requirement. All of these neural and non-neural cell types can release ATP for intercellular communication, and all are equipped with a rich diversity of membrane receptors for extracellular ATP and its metabolites, as well as the extracellular enzymes that regulate ATP hydrolysis. The second messenger systems activated by these receptors mediate a diverse range of nervous system processes, from the millisecond duration of synaptic transmission to timescales of development and regeneration.

The last 10 years has been a period of rapid progress in the identification of the numerous types of purinergic receptor, and in understanding their relationships, pharmacology and intracellular signalling. This progress has led to new appreciation of ATP and adenosine in neuron–glia interactions, bringing new and unexpected insights into how glia respond to neural impulse activity and participate in nervous system function (see online Supplementary information S2 (table)).

Many mechanisms for the release of ATP from cells have been identified in recent years. The problem for the future will be to isolate which release mechanism operates in a given context. This will require considerably more research on ATP release from neurons and glia, and the development of new methods to probe and control the various release mechanisms.

ATP signalling must be considered together with adenosine signalling. The often antagonistic actions of ATP and adenosine provide a mechanism for glia (and other cells) to have biphasic effects in cellular interactions. This may be a particularly important mechanism for glia in maintaining homeostatic regulation of neural activity.

The expression of specific purinergic receptors in neurons and glia must be determined at a much finer level. This analysis is difficult, because of the large number of receptor types and the complex interactions between various types of purinergic receptor co-expressed in cells. This difficulty is augmented by the overlapping specificity of many agonists and antagonists. At the same time, the poorly understood heterogeneity of neuroglia, and the dynamic nature of glia, compound this challenge.

More selective pharmacological tools are continually being developed, and this will accelerate progress in uncovering the extremely broad scope of biological functions mediated by ATP signalling between neurons, glia and other types of cells. This will lead to more selective drugs for treating nervous system disorders. There is an equally demanding requirement to isolate the particular biological effects mediated by specific types of purinergic receptor. In addition to more selective agonists and antagonists, new animal models for studying purinergic signalling will facilitate collection of these essential data.

The chemistry of ATP in the extracellular environment is dynamic and complex, and comparatively little is known about the extracellular biochemistry and enzymes that regulate the synthesis and degradation of ATP outside the cell. Only a superficial understanding of how these systems of ecto-enzymes differ in various regions of the nervous system has been obtained. Similarly, the activity of ectonucleotidases in subcellular domains, and how these enzymes change with development, disease and physiological state are not known in sufficient detail.

Acting as a messenger outside the cell, ATP provides a system of neuron–glia signalling that operates at and beyond synapses. As the complex expression patterns and actions of purinergic receptors in neurons and glia are untangled, new interactions between them will be revealed, with wide-ranging medical implications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health intramural research funds.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

DATABASES

The following terms in this article are linked online to:

Entrez Gene: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=gene

BDNF | GFAP

OMIM: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=OMIM

Alexander disease | Alzheimer’s disease | Parkinson’s disease

FURTHER INFORMATION

Fields’s laboratory: http://nsdps.nichd.nih.gov/

Burnstock’s laboratory: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/ani

References

- 1.Altevogt BM, Paul DL. Four classes of intercellular channels between glial cells in the CNS. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4313–4323. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3303-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lev-Ram V, Ellisman MH. Axonal activation-induced calcium transients in myelinating Schwann cells, sources, and mechanisms. J Neurosci. 1995;15:2628–2637. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-02628.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCarthy KD, Salm AK. Pharmacologically-distinct subsets of astroglia can be indentified by their calcium response to neuroligands. Neuroscience. 1991;41:325–333. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90330-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porter JT, McCarthy KD. Hippocampal astrocytes in situ respond to glutamate released from synaptic terminals. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5073–5081. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-05073.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burnstock G. In: Current Topics in Membranes. Schwiebert EM, editor. Vol. 54. Academic; San Diego: 2003. pp. 307–368. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fields RD. Purinergic Signaling in Neuron–Glia Interactions. In: Chadwick DJ, Goode J, editors. Novartis Found Symp No. 276. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drury AN, Szent-Györgyi A. The physiological activity of adenine compounds with special reference to their action upon the mammalian heart. J Physiol (Lond) 1929;68:213–237. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1929.sp002608. Studies on cardiac function were the first to identify physiological actions of extracellular ATP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burnstock G. Purinergic nerves. Pharmacol Rev. 1972;24:509–581. Advanced the concept of ATP as a neurotransmitter/co-transmitter and coined the word ‘purinergic’. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holton FA, Holton P. The capillary dilator substances in dry powders of spinal roots; a possible role of adenosine triphosphate in chemical transmission from nerve endings. J Physiol. 1954;126:124–140. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burnstock G, Campbell G, Satchell D, Smythe A. Evidence that adenosine triphosphate or a related nucleotide is the transmitter substance released by non-adrenergic inhibitory nerves in the gut. Br J Pharmacol. 1970;40:668–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1970.tb10646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burnstock G. Do some nerve cells release more than one transmitter? Neuroscience. 1976;1:239–248. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(76)90054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards FA, Gibb AJ, Colquhoun D. ATP receptor-mediated synaptic currents in the central nervous system. Nature. 1992;369:144–147. doi: 10.1038/359144a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jahr CE, Jessell TM. ATP excites a subpopulation of rat dorsal horn neurons. Nature. 1983;304:730–733. doi: 10.1038/304730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Redman RS, Silinsky EM. ATP release together with acetylcholine as the mediator of neuromuscular depression at frog motor nerve endings. J Physiol (Lond) 1994;477:117–127. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burnstock G. Purinergic Signalling in Neuron–Glia Interactions. In: Chadwick DJ, Goode J, editors. Novartis Found Symp No. 276. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2006. pp. 26–53. A recent overview of purinergic signalling. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawynok J, et al. ATP release from dorsal spinal cord synaptosomes: characterization and neuronal origin. Brain Res. 1993;610:32–38. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91213-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vizi ES, Sperlagh B, Baranyi M. Evidence that ATP released from the postsynaptic site by noradrenaline is involved in mechanical response of guinea-pig vas deferens: cascade transmission. Neuroscience. 1992;50:455–465. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90437-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmermann H. Signalling via ATP in the nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:420–426. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fields RD, Stevens B. ATP in signaling between neurons and glia. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:625–633. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01674-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neary JT, van Breemen C, Forster E, Norenberg LO, Norenberg MD. ATP stimulates calcium influx in primary astrocyte cultures. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;157:1410–1416. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)81032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearce B, Murphy S, Jeremy J, Morrow C, Dandona P. ATP-evoked Ca2+ mobilisation and prostanoid release from astrocytes: P2-purinergic receptors linked to phosphoinositide hydrolysis. J Neurochem. 1989;52:971–977. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb02549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirischuk S, Moller T, Voitenko N, Kettenmann H, Verkhratsky A. ATP-induced cytoplasmic calcium mobilization in Bergmann glial cells. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7861–7871. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-07861.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyons SA, Morell P, McCarthy KD. Schwann cells exhibit P2Y purinergic receptors that regulate intracellular calcium and are up-regulated by cyclic AMP analogs. J Neurochem. 1994;63:552–560. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63020552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayer C, Quasthoff S, Grafe P. Differences in the sensitivity to purinergic stimulation of myelinating and non-myelinating Schwann cells in peripheral human and rat nerve. Glia. 1998;23:374–382. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199808)23:4<374::aid-glia9>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burnstock G, Knight GE. Cellular distribution and functions of P2 receptor subtypes in different systems. Int Rev Cytol. 2004;240:31–304. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(04)40002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kastritsis CH, McCarthy KD. Oligodendroglial lineage cells express neuroligand receptors. Glia. 1993;8:106–113. doi: 10.1002/glia.440080206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robitaille R. Purinergic receptors and their activation by endogenous purines at perisynaptic glial cells of the frog neuromuscular junction. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7121–7131. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07121.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuperman AS, Volpert WA, Okamoto M. Release of adenine nucleotide from nerve axons. Nature. 1964;204:1000–1001. doi: 10.1038/2041000a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kriegler S, Chiu SY. Calcium signaling of glial cells along mammalian axons. J Neurosci. 1993;13:4229–4245. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-10-04229.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stevens B, Fields RD. Action potentials regulate Schwann cell proliferation and development. Science. 2000;287:2267–2271. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2267. Showed that ATP is released from axons firing action potentials, and that this activates receptors on myelinating glia to regulate gene expression, inhibit cell proliferation, differentiation and myelination. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stevens B, et al. Adenosine: a neuron–glial transmitter promoting myelination in the CNS in response to action potentials. Neuron. 2002;36:855–868. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01067-x. Revealed a mechanism for action potentials promoting myelination in the CNS. Activation of adenosine receptors on oligodendrocyte progenitor cells promotes differentiation and increases myelination. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neary JT, Whittemore SR, Zhu O, Norenberg MD. Synergistic activation of DNA synthesis in astrocytes by fibroblast growth factors and extracellular ATP. J Neurochem. 1994;63:490–494. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63020490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abbracchio MP, et al. Effects of ATP analogues and basic fibroblast growth factor on astroglial cell differentiation in primary cultures of rat striatum. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1995;13:685–693. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(95)00064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mishra SK. Extracellular nucleotide signaling in adult neural stem cells: synergism with growth factor-mediated cellular proliferation. Development. 2006;133:675–684. doi: 10.1242/dev.02233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neary JT. Trophic roles of P2-purinoceptors in Central Nervous System Astroglial Cells. In: Chadwick DJ, Goode J, editors. CIBA Found Symp No. 198. 1996. pp. 130–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toescu EC, Moller T, Kettenmann H, Verkhratsky A. Long-term activation of capacitive Ca2+ entry in mouse microglial cells. Neuroscience. 1998;86:925–935. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boucsein C, et al. Purinergic receptors on microglia cells: functional expression in acute brain slices and modulation of microglial activation in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:2267–2276. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hide I, et al. Extracellular ATP triggers tumor necrosis factor-α release from rat microglia. J Neurochem. 2000;75:965–972. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inoue K, et al. ATP stimulation of Ca2+-dependent plasminogen release from cultured microglia. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123:1304–1310. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Light AR, Wu Y, Hughen RW, Guthrie PB. Purinergic receptors activating rapid intracellular Ca2+ increases in microglia. Neuron Glia Biol. 2006;2:125–138. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X05000323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davalos D, et al. ATP mediates rapid microglial response to local brain injury in vivo. Nature Neurosci. 2005;8:752–758. doi: 10.1038/nn1472. In vivo imaging of ATP-mediated microgial response to brain injury. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guthrie PB, et al. ATP release from astrocytes mediates glial calcium waves. J Neurosci. 1999;19:520–528. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00520.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cotrina ML, et al. Connexins regulate calcium signaling by controlling ATP release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15735–15740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hassinger TD, et al. An extracellular signaling component in propagation of astrocytic calcium waves. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13268–13273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13268. Showed that intercellular calcium waves in cultured astrocytes can propagate across glial free zones, implicating extracellular ATP and glutamate as cell–cell signalling molecules. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Z, Haydon PG, Yeung ES. Direct observation of calcium-independent intercellular ATP signaling in astrocytes. Anal Chem. 2000;72:2001–2007. doi: 10.1021/ac9912146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Innocent B, Parpura V, Haydon PG. Imaging extracellular waves of glutamate during calcium signaling in cultured astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1800–1808. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-01800.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Araque A, Sanzgiri RP, Parpura V, Haydon PG. Calcium elevation in astrocytes causes an NMDA receptor-dependent increase in the frequency of miniature synaptic currents in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6822–6829. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06822.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Newman EA. Propagation of intercellular calcium waves in retinal astrocytes and Müller cells. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1–13. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02215.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schipke CG, Boucsein C, Ohlemeyer C, Kirchhoff F, Kettenmann H. Astrocyte Ca2+ waves trigger responses in microglial cells in brain slices. FASEB J. 2002;16:255–257. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0514fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sul JY, Orosz G, Givens RS, Haydon PG. Astrocytic connectivity in the hippocampus. Neuron Glia Biol. 2004;1:3–12. doi: 10.1017/s1740925x04000031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bodin P, Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling: ATP release. Neurochem Res. 2001;26:959–969. doi: 10.1023/a:1012388618693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lazarowski ER, Boucher RC, Harden TK. Mechanisms of release of nucleotides and integration of their action as P2X- and P2Y-receptor activating molecules. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:785–795. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.4.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maienschein V, Marxen M, Volknandt W, Zimmermann H. A plethora of presynaptic proteins associated with ATP-storing organelles in cultured astrocytes. Glia. 1999;26:233–244. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199905)26:3<233::aid-glia5>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pascual O, et al. Astrocytic purinergic signaling coordinates synaptic networks. Science. 2005;310:113–116. doi: 10.1126/science.1116916. Reports that heterosynaptic LTD and threshold for LTP in the hippocampus are regulated by adenosine derived from ATP released from astrocytes. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coco S, et al. Storage and release of ATP from astrocytes in culture. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1354–1362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209454200. One of the first studies to show release of ATP from astrocytes as exocytotic. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suandicani SO, Pina-Benabou MH, Urban-Maldonado M, Spray DC, Scemes E. Acute downregulation of Cx43 alters P2Y receptor expression levels in mouse spinal cord astrocytes. Glia. 2003;42:160–171. doi: 10.1002/glia.10197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suadicani SO, Brosnan C. F & Scemes, E P2X7 receptor mediate ATP release and amplification of astrocytic intercellular calcium signaling. J Neurosci. 2003;26:1378–1385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3902-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arcuino G, et al. Intercellular calcium signaling mediated by point-source burst release of ATP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9840–9845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152588599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Darby M, Kuzmiski JB, Panenka W, Feighan D, MacVicar BA. ATP release from astrocytes during swelling activates chloride channels. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:1870–1877. doi: 10.1152/jn.00510.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ryten M, Yang SY, Dunn PM, Goldspink G, Burnstock G. Purinoceptor expression in regenerating skeletal muscle in the mdx mouse model of muscular dystrophy and in satellite cell cultures. FASEB J. 2004;18:1404–1406. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1175fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zimmermann H. Ectonucleotidases: some recent developments and a note on nomenclature. Drug Dev Res. 2001;52:44–56. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zimmermann H. 5′-Nucleotidase: molecular structure and functional aspects. Biochem J. 1992;285:345–365. doi: 10.1042/bj2850345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burnstock G. In: Cell Membrane Receptors for Drugs and Hormones: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Straub RW, Bolis L, editors. Raven; New York: 1978. pp. 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van Calker D, Müller M, Hamprecht B. Adenosine regulates via two different types of receptors, the accumulation of cyclic AMP in cultured brain cells. J Neurochem. 1979;33:999–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1979.tb05236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Burnstock G, Kennedy C. Is there a basis for distinguishing two types of P2-purinoceptor? Gen Pharmacol. 1985;16:433–440. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(85)90001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G. Purinoceptors: are there families of P2X and P2Y purinoceptors? Pharmacol Ther. 1994;64:445–475. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(94)00048-4. Review introducing the currently used nomenclature adopted for P2X and P2Y receptors. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dubyak GR. Signal transduction by P2-purinergic receptors for extracellular ATP. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1991;4:295–300. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/4.4.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lustig KD, Shiau AK, Brake AJ, Julius D. Expression cloning of an ATP receptor from mouse neuroblastoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5113–5117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Webb TE, et al. Cloning and functional expression of a brain G-protein-coupled ATP receptor. FEBS Lett. 1993;324:219–225. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81397-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brake AJ, Wagenbach MJ, Julius D. New structural motif for ligand-gated ion channels defined by an ionotropic ATP receptor. Nature. 1994;371:519–523. doi: 10.1038/371519a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Valera S, et al. A new class of ligand-gated ion channel defined by P2X receptor for extra-cellular ATP. Nature. 1994;371:516–519. doi: 10.1038/371516a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.North RA. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:1013–1067. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Abbracchio MP, et al. Characterization of the UDP-receptor) glucose receptor (re-named here the P2Y14 adds diversity to the P2Y receptor family. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:52–55. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(02)00038-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abbracchio MP, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. Update and subclassification of the P2Y G protein-coupled nucleotide receptors: from molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology to therapy. PharmacolRev. 2006 doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yokomizo T, Izumi T, Chang K, Takuwa Y, Shimizu T. A G-protein-coupled receptor for leukotriene B4 that mediates chemotaxis. Nature. 1997;387:620–624. doi: 10.1038/42506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bogdanov YD, Dale L, King BF, Whittock N, Burnstock G. Early expression of a novel nucleotide receptor in the neural plate of Xenopus embryos. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12583–12590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]