Abstract

Assigning functions to every gene in a living organism is the next challenge for functional genomics. In fact, 85–90% of the 19,000 genes of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans genome do not produce any visible phenotype when inactivated, which hampers determining their function, especially when they do not belong to previously characterized gene families. We used 1H high-resolution magic angle spinning NMR spectroscopy (1H HRMAS-NMR) to reveal the latent phenotype associated to superoxide dismutase (sod-1) and catalase (ctl-1) C. elegans mutations, both involved in the elimination of radical oxidative species. These two silent mutations are significantly discriminated from the wild-type strain and from each other. We identify a metabotype significantly associated with these mutations involving a general reduction of fatty acyl resonances from triglycerides, unsaturated lipids being known targets of free radicals. This work opens up perspectives for the use of 1H HRMAS-NMR as a molecular phenotyping device for model organisms. Because it is amenable to high throughput and is shown to be highly informative, this approach may rapidly lead to a functional and integrated metabonomic mapping of the C. elegans genome at the systems biology level.

Keywords: functional genomics, metabolic profiling, metabonomics, nuclear magnetic resonance

Assigning functions to every gene in a living organism is the next challenge for functional genomics. However, only a small proportion of genes produce visible phenotypes when inactivated; for example, only 10–15% of the 19,000 genes of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans produce a visible phenotype (1, 2). For the remaining ones, determining their function is more difficult, especially when they do not belong to previously characterized gene families.

For example, oxidative stress is a key, yet subtle, biological process involved in aging, with long-term integration of many slow processes leading to irreversible cellular and molecular damage.

Phenotyping plays a critical role in postgenomic sciences. Today, a range of molecular phenotyping tools is available to characterize mutations. Although gene expression and protein profiling are predominantly used (3–5), metabonomic and metabolomic strategies (6, 7) advantageously produce metabolic fingerprints that allow identification of variations in low-molecular-weight compounds in biofluids or organs in response to pathophysiological events (8), drug treatments (9), or genetic polymorphisms (10). It is therefore an attractive hypothesis-free approach for large-scale functional genomics in model organisms (11).

Here we capitalize on recent developments in solid-state NMR that allow the acquisition of highly resolved 1H spectra of metabolites from inhomogeneous materials such as biopsies (12) or food (13). As shown below, when applying 1H high-resolution magic angle spinning NMR spectroscopy (1H HRMAS-NMR), we provide complex metabolic phenotypes (6) or metabotypes (8) suitable for discriminating between C. elegans oxidative stress mutants, which cannot otherwise be distinguished phenotypically (14). In this study, we develop, validate, and apply a strategy using 1H HRMAS-NMR spectroscopy of whole-model organisms, in this case C. elegans, to reveal the latent phenotypes associated with silent mutations (11) in Metazoans, an approach already developed in yeast and plants using mass spectrometry and liquid-state NMR (15, 16). In particular, we investigate subtle metabolic disruptions induced by mutations of oxidative stress enzymes. We show, as a proof of concept of this strategy, a metabotype significantly associated to oxidative stress mutants with otherwise no overt phenotypes, i.e., silent mutations in the terminology of Oliver and coworkers (11).

Results

1H HRMAS-NMR Reveals Metabolic Phenotypes for Both Morphological and Invisible Mutations.

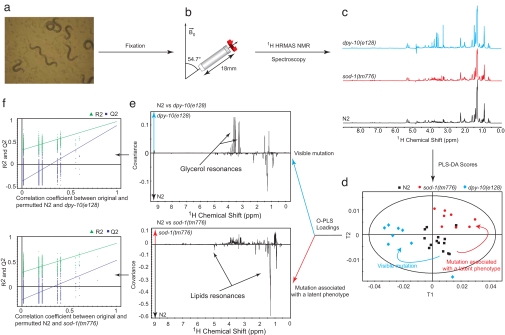

To investigate the potential of metabonomics to produce reliable metabolic phenotypes for C. elegans, we first recorded 1H HRMAS-NMR spectra of three C. elegans strains: a wild-type strain (N2), the collagen dpy-10(e128) mutant, which displays a visible (morphological) phenotype, and the sod-1(tm776) mutant, which has no overt phenotype.

Approximately 1,000 worms (Fig. 1a) were filled in a HRMAS-NMR rotor and spun at 3.5 kHz for 1D 1H HRMAS-NMR acquisition (Fig. 1b). Spectra were recorded for each sample [Fig. 1c; see supporting information (SI) Table 1 for assignment] and bucketed with a 10−3-ppm resolution. We note that there is no particular indication in these spectra (broadening or splitting) of distributions of molecular environments within the sample. Supervised multivariate statistical modeling using partial least-squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) shows a significant discrimination of the three strains (Fig. 1d) and reveals strain-specific metabolic features for dpy-10(e128) and more remarkably for sod-1(tm776) (Fig. 1e). To validate discrimination of mutations, we resampled the model under the null hypothesis by generating 999 random permutations of the class vector. This shows that none of the random models outperforms the initial model in terms of prediction (Fig. 1f).

Fig. 1.

1H HRMAS-NMR analysis and supervised multivariate analysis of spectral data to probe metabolism of C. elegans oxidative stress mutants. Worms (a) were filled into a 4-mm diameter HRMAS-NMR rotor and spun at a frequency of 3.5 kHz (b) to acquire 1H NMR spectra at 700 MHz (c). Under rotation at the so-called magic angle, the various sources of NMR broadening, including the anisotropy of the magnetic susceptibility, dipolar interactions, and chemical shifts, are averaged to their isotropic contribution to produce spectra with sharp resonances (28). Partial least-squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) was applied to generate a model showing the variability between groups based on genetics (d), in which each point represents the projection of a HRMAS-NMR spectrum onto the optimal discrimination plan. Metabolic patterns supporting the genetic discrimination are identified (e) for both morphological and nonmorphological mutations. Each point in the pseudospectra represents the model coefficient associated with this region. Model validations (f) were performed by resampling the model 999 times under the null hypothesis H0 (i.e., generating null models with a randomly permuted YH0 not related to the factors of interest, genetics, and age, such as in the original YH1). The decrease in model goodness-of-fit statistics R2 and Q2 as a function of the correlation between YH1 and YH0 shows that none of the 999 randomly permuted models outperforms the initial model. R2 relates to the explained variance, i.e., the ability to describe data, whereas Q2 summarizes the predictive variance, i.e., the ability to predict correctly new data.

In this case the extent of metabolic variations in the spectra illustrated in Fig. 1e are just as large for the invisible sod-1 mutant as for the visible dpy-10 mutant. dpy-10 mutants are characterized by higher glycerol levels; such elevation was previously shown to be involved in the osmotic stress response of C. elegans (17) and is compliant with similar observations in other model organisms. These data clearly demonstrate the potential of 1H HRMAS-NMR to investigate metabolic changes induced by mutations, regardless of the extent of the observable morphological phenotypes. If these morphological and latent phenotypes are validated, this represents a major step forward for functional genomic studies of C. elegans.

Statistical Support for Latent Metabolic Phenotypes.

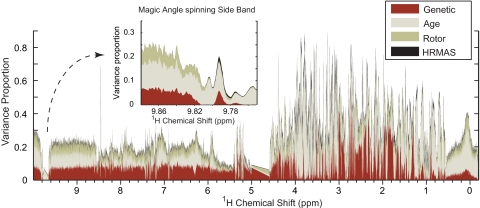

To address the reproducibility and robustness of C. elegans latent metabolic phenotypes using 1H HRMAS-NMR, we then tested and controlled several biological and technological factors that could potentially affect the observed metabotype, namely the effects of strain [N2 vs. sod-1(tm776)], age (L4 larvae vs. gravid adults), sample preparation (MAS rotors lightly vs. heavily loaded), and the NMR analysis itself (two acquisitions for each sample). A variance component model assesses the relative contribution of each factor to the variance of each of the 10,000 data points (Fig. 2), showing a baseline technological variation of ≈5–10% in regions with no NMR metabolic signal and a biological variation up to 85% for age and 70% for the mutation effect, mainly in the aliphatic region (δ[0;4.6]). This 24 full factorial design (involving 134 spectra from 67 samples) and variance component analysis clearly show that biological variation exceeds technological variation by nearly an order of magnitude. This is also confirmed by low coefficients of variation (SI Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Characterization of biological and technological factors. The effects of biological factors (i.e., genetics and age) and technological factors (i.e., rotor filling and instrumental reproducibility) were assessed by an O2PLS (29) variance component model by using a 24 full factorial design as Y matrix and NMR as X matrix. For each NMR variable, the model computes the proportion of variance (scaled to 1.0) attributed to each one of the four factors (genetics, age, rotor, and HRMAS) across the entire 1H HRMAS-NMR spectrum; the remaining white area corresponds to the residual of the model with a total of 100%. The maximum of the variance proportion for each factor is 54%, 82%, 21%, and 8% for genetics, age, rotor filling, and instrumental reproducibility, respectively. Biological factors show the strongest variance proportions in the aliphatic part of the spectrum (δ[0;4.6]), whereas technological parameters such as instrumental reproducibility show a stronger variance proportion in the magic angle spinning side bands of the residual water signal (δ 9.79), for instance. Further scores, loadings, and internal validation are presented in SI Fig. 5.

We then focused on the two biological factors assessed in this analysis, i.e., the effect of mutation sod-1(tm776) and the effect of age (SI Fig. 5). Because oxidative stress is a physiological process, we need to evaluate potentially confounding physiological variations, such as age. The orthogonal partial least-square (OPLS) score plots show a remarkable capacity for discrimination of both the genetic component (SI Fig. 5a) and the age component (SI Fig. 5b), and the loadings plots show metabotypes supporting these discriminations. Discriminant metabolites are lower lipid resonances (δ 0.90 CH3CH2CH2C = C; 1.16 CH3CH2CH2; 1.30 CH2CH2CH2CO in fatty acyls; 1.41 CH2CH2CO; 1.59 CH2CH2C = C; 4.09 glyceryl of lipids CH2OCOR; 5.33 unsaturated lipids = CHCH2CH2) and higher trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) (δ 3.27) in sod-1(tm776) compared with N2 worms (SI Table 2). This pattern corresponds to strain discrimination regardless of age (L4 larvae and gravid adults).

Further validation was realized by using the soft independent modeling of class analogy (SIMCA) algorithm (18). SIMCA was run for age and genetic discrimination. In both cases test sets [for age, L4 larvae vs. gravid adults; for genetic, dpy-10(e128) vs. N2 and sod-1(tm776)] are projected in the exclusion area, affirming the efficiency of the model to discriminate nematode groups. There is no overlap between the different groups, which confirms that the oxidative stress and the age-related metabolic patterns are distinct (SI Fig. 6).

These results confirm that age and genetic factors generate two different patterns (SI Fig. 5 c and d), allowing NMR-based metabotyping to distinguish the subtle metabolic changes induced by mutation of a key oxidative stress enzyme from that due to age. They also validate the robustness of the latent metabolic phenotype associated with sod-1 (homology between the loadings in Fig. 1c and SI Fig. 5c).

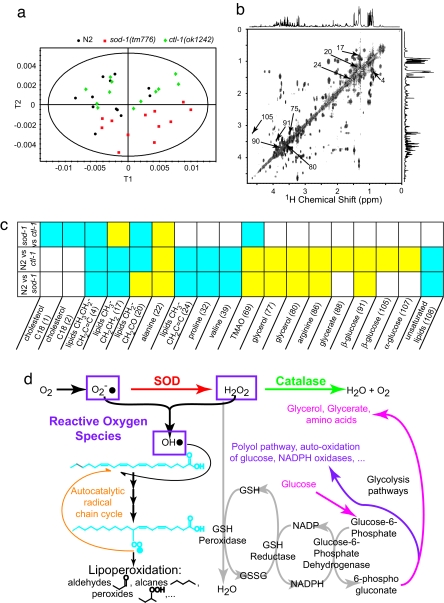

Metabonomic Mapping of Oxidative Stress Genes Reveals Similar Metabotypes.

To assess whether this strategy generates biologically relevant metabotypes that might qualify as candidate biomarkers, we then compared the profiles of strains lacking consecutive enzymes involved in oxygen dismutation (Fig. 3): sod-1(tm776) and ctl-1(ok1242). ctl-1 encodes a catalase downstream of superoxide dismutase in the detoxification pathway of reactive oxygen species (ROS). PLS-DA shows a discrimination of N2, sod-1(tm776), and ctl-1(ok1242) (Fig. 3a). sod-1(tm776) and ctl-1(ok1242) mutants are both metabolically characterized by a reduction of lipids signals (δ 0.90 CH3CH2CH2C = C; 1.30 CH2CH2CH2CO; 1.41 CH2CH2CO; 1.59 CH2CH2C = C; 5.33 unsaturated lipids = CHCH2CH2), as confirmed by 2D NMR (Fig. 3b). In addition, ctl-1(ok1242) presents an accumulation of glucose (δ 3.92 CH2-C6; 4.63 β-anomeric H1; 5.23 α-anomeric H1), glycerate (δ 3.84 CH2), and glycerol (δ 3.56 CH2; 3.65 CH2) as presented in SI Table 3.

Fig. 3.

sod-1(tm776) and ctl-1(ok1242) oxidative stress metabotypes and biological relevance. (a) The PLS-DA scores plot shows a discrimation among the three strains. (b and c) Summaries of O-PLS loadings between sod-1(tm776) and N2, ctl-1(ok1242) and N2, and sod-1(tm776) and ctl-1(ok1242), respectively (c), show variations in concentration that can be linked to metabolites by the use of 2D HRMAS COSY (and other 2D HRMAS correlation experiments) for assignment (b). Yellow squares, positive correlation; blue squares, negative correlation (where the first strain mentioned is the negative control and the second strain is the positive control). (d) Biochemical mechanisms of oxidative stress observed in sod-1(tm776) and ctl-1(ok1242) strains.

As a result, these observations show that our metabotyping approach identifies close but distinct metabolic markers associated with oxidative stress silent mutations. Our analysis strongly suggests that oxidative stress caused by silent mutations is a distributed process across the whole metabolic system, because we identified a combination of several metabolites (a metabotype) predictive of oxidative stress.

Discussion

Biological Relevance of Oxidative Stress Metabotypes.

Different hypotheses can be proposed to explain these metabolic patterns (Fig. 3d): the reduction of lipid signals observed in both sod-1(tm776) and ctl-1(ok1242) suggests that the lack of ROS detoxification enzymes in these two strains leads to an elevation of ROS. This is consistent with the fact that lipids are primary targets of free radicals (19, 20). In this metabolic pattern established for both the sod-1(tm776) and ctl-1(ok1242) mutants, the reduction in lipids shows a new homeostatic equilibrium, in which increased lipoperoxidation (denoted by CH2CH2CO aldehyde resonances at δ 1.40 characteristic of some lipoperoxidation products) is balanced by reduced availability of substrate for free radical reactions. The increased amount of trimethylamine-N-oxide, an osmolyte-stabilizing protein conformation (21), could derive from the interplay between cellular oxidative stress and osmotic stress (22). Interestingly, TMAO is a sym-xenobiotic metabolite (23) (coprocessed by enterobacteria) that was shown to be involved in insulin resistance in mammals (8).

Thus, in both mutants we observe a similar reduction of lipid levels, consistent with a pathway-level signature. However, whereas SOD is the only pathway transforming superoxide radicals to hydrogen peroxide, in the absence of catalase, pathway redundancy leaves the GSH peroxidase pathway for the elimination of hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 3d). Because recycling of GSH is coupled to glucose metabolism by NADPH/NADP+ redox cycles, lack of catalase may indirectly lead to an increase in glucose and its degradation products (mainly glycerol and glycerate) (24) used to replenish NADP+. As for the sod-1(tm776) case above, this rationale is fully supported by the metabotypes we identify here for ctl-1(ok1242).

Mutations affecting consecutive enzymes in the same pathway lead to similar (SI Fig. 7 a and c), albeit distinct (SI Fig. 7e), metabotypes. Thus, not only does NMR analysis of the mutants distinguish these latent phenotypes from others, it also provides a clear picture of the subtle metabolic changes induced by silent mutations, with both pathway-specific and mutation-specific metabotypes.

Conclusions

Our results show that 1H HRMAS-NMR-based metabolic profiling is a powerful and reliable approach providing both metabolic fingerprints and metabolic phenotypes (metabotypes) for both morphological and invisible mutations in preparations of 1,000 worms, as well as fine mapping of metabolic consequences of oxidative stress mutations of C. elegans. A major advantage of the high-field 1H HRMAS methodology introduced here is the preservation of intracellular integrity, which is particularly relevant to the study of the intricate metabolic regulation linked to oxidative stress at the systems level.

Our 1H HRMAS-NMR metabotyping approach presented here is by no means limited to studying oxidative stress and should be useful in the detailed metabolic characterization of C. elegans and other model organisms in functional, chemical, and environmental genomics, providing key molecular phenotypes between the genome and classical markers of health and disease.

Methods

Nematodes.

The C. elegans strains used in this study were wild type (N2), and mutant genotypes sod-1(tm776), ctl-1(ok1242), and dpy-10(e128). Worms were raised at 15°C and fed well at all times. They were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in M9 saline buffer during 30 min at room temperature, then washed three times with water. A last wash was performed by using D2O to provide a field-frequency lock signal for NMR experiments. A population of ≈1,000 worms was then filled into a 4-mm HRMAS rotor with Kel-f inserts restricting the effective sample volume to a 12-μl sphere. A speed vacuum engine was used to remove D2O surplus, and NMR acquisition was then performed on the same day.

1H HRMAS-NMR Spectroscopy.

All NMR experiments were carried out on a Bruker Avance spectrometer operating at 700 MHz, using a standard double resonance (1H-13C) 4-mm HRMAS probe. Standard HRMAS 1D nOe spectroscopy experiments (25) (recycle delay–90°–τ–90°–tm–90°–acquisition) were carried out on each sample. Water suppression was achieved by using low-power irradiation of the water resonance during the recycle delay of 1.7 s. The mixing time, tm, was set to 100 ms. The 90° pulse length was adjusted to 5.3 μs, and τ was adjusted to 4 μs. A total of 16,000 data points with 512 scans were acquired by using a spectral width of 8,503 Hz, for a total acquisition time of ≈25 min. The magic angle spinning frequency was set to 3.5 kHz, and the sample temperature was regulated at 293 K. 1H chemical shifts were internally referenced to the alanine CH3 doublet at δ 1.48. All free induction decays were multiplied by an exponential function equivalent to a 1-Hz line-broadening factor before Fourier transformation.

For the purpose of assignment of the observed NMR spectral resonances to various metabolites, a set of 2D 1H HRMAS correlation experiments was carried out, as previously reported in the literature (26), including 1H COSY, total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY), and J-resolved experiments. Heteronuclear single quantum spectroscopy was used to reveal direct proton carbon connectivities. TOCSY was run by using the DIPSI2 spin-lock scheme for 1H-1H transfers with a 90° pulse of 80 μs and a mixing time of 0.1 s. For COSY, 2,048 t2 data points with 128 scans per increment and 300 t1 data points were acquired. For TOCSY, 2,048 t2 data points with 128 scans per increment and 470 t1 data points were acquired. The spectral width in both dimensions was 7,500 Hz for both COSY and TOCSY experiments. For the J-resolved experiment, 4,096 t2 data points with 128 t1 data points were acquired. Spectral widths were set to 7,500 Hz in F2 and 40 Hz in F1. Finally, HSQC was run with 2,048 t2 data points with 432 scans for each of the 256 t1 data points. Spectral widths were set to 7,500 Hz in F2 and 35,200 Hz in F1. Total acquisition time was ≈36 h for COSY, 13 h for TOCSY, 24 h for the J-resolved experiment, and 67 h for HSQC. Assignment was established from a Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill (27) spin-echo spectrum. The acquisition time was 8 min (256 scans). The spin–spin relaxation delay (τ–π–τ) was set to 810 μs, and 200 loops were performed before acquisition.

Data Import and Pattern Recognition.

1H HRMAS-NMR spectra were phased by using the Topspin 1.3 interface. They were reduced over the chemical shift range of −0.49 to 9.59 ppm with exclusion areas around residual water signal (4.61–4.99 ppm) and its magic angle spinning side band (−0.40 to −0.19 ppm), except for statistical support analysis, using AMIX (Bruker) to 10,000 10−3-ppm wide regions (buckets), and the signal intensity in each region was integrated. Spectra were scaled to total intensity, and integration was performed with the sum-of-intensities mode. The corresponding buckets table was then exported to the software Simca-P 11 (Umetrics) for statistical analysis.

Multivariate Statistics.

Principal component analyses (PCA) were run to check the homogeneity of each subpopulation and eventually exclude outliers. Data were then visualized by scores and loadings plots. In scores plots, each point represents a NMR spectrum and thus a sample. Loadings points stand for NMR spectral regions and show intensity variations sustaining the distinction between subpopulations.

OPLS analysis and PLS-DA were run to discriminate two respectively three populations of nematodes by adding a supplementary data matrix Y, containing information about genetic, age, or technological factors. These methods allow a clearer distinction between populations by canceling orthogonal information to the Y matrix, which are of no use for this particular discrimination. As for PCA, results were visualized by scores and loadings plots. Model validations were performed by resampling the model 999 times under the null hypothesis, meaning generating models with a randomly permuted Y matrix not related to the factors of interest. The decrease in model goodness-of-fit statistics R2 and Q2 as a function of the correlation between the permuted and the original Y matrix indicates the quality of the model.

The SIMCA algorithm was used to probe the prediction capacity of the established models. The data set was divided in three. Two of them are used as training sets to create a map. PCA of each group was run to establish the limit of membership to each class. These results are then organized on a 2D plan defining four areas. Upper left and lower right are the area of membership to one of the training set populations. Lower left is the region of membership to the two populations. Finally, upper right may be understood as an exclusion area, where no membership to the training set populations may be found. The last part of the data set is then used as a test set. Every point (representing a spectrum) is projected on this plan, and its membership to one of the training set populations is validated by the position of this projection with respect to the models' limits.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Armand M. Leroi and Dr. Jake Bundy for helpful discussions and Bruker Biospin (Drs. Martial Piotto, Alain Belguise, and Manfred Spraul) for its financial and scientific support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0707393104/DC1.

References

- 1.Kamath RS, Fraser AG, Dong Y, Poulin G, Durbin R, Gotta M, Kanapin A, Le Bot N, Moreno S, Sohrmann M, et al. Nature. 2003;421:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nature01278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simmer F, Moorman C, van der Linden AM, Kuijk E, van den Berghe PVE, Kamath RS, Fraser AG, Ahringer J, Plasterk RHA. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:77–84. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill AA, Hunter CP, Tsung BT, Tucker-Kellogg G, Brown EL. Science. 2000;290:809–812. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5492.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaletta T, Hengartner MO. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2006;5:387–398. doi: 10.1038/nrd2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwok TCY, Ricker N, Fraser R, Chan AW, Burns A, Stanley EF, McCourt P, Cutler SR, Roy PJ. Nature. 2006;441:91–95. doi: 10.1038/nature04657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholson JK, Lindon JC, Holmes E. Xenobiotica. 1999;29:1181–1189. doi: 10.1080/004982599238047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicholson JK, Connelly J, Lindon JC, Holmes E. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2002;1:153–161. doi: 10.1038/nrd728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dumas ME, Barton RH, Toye A, Cloarec O, Blancher C, Rothwell A, Fearnside J, Tatoud R, Blanc V, Lindon JC, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12511–12516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601056103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clayton TA, Lindon JC, Cloarec O, Antti H, Charuel C, Hanton G, Provost JP, Le Net JL, Baker D, Walley RJ, et al. Nature. 2006;440:1073–1077. doi: 10.1038/nature04648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dumas ME, Wilder SP, Bihoreau MT, Barton RH, Fearnside JF, Argoud K, D'Amato L, Wallis RH, Blancher C, Keun HC, et al. Nat Genet. 2007;39:666–672. doi: 10.1038/ng2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raamsdonk LM, Teusink B, Broadhurst D, Zhang NS, Hayes A, Walsh MC, Berden JA, Brindle KM, Kell DB, Rowland JJ, et al. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:45–50. doi: 10.1038/83496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng LL, Ma MJ, Becerra L, Ptak T, Tracey I, Lackner A, Gonzalez RG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6408–6413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shintu L, Caldarelli S. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:4026–4031. doi: 10.1021/jf048141y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antoshechkin I, Sternberg PW. Nat Genet. 2007;8:518–532. doi: 10.1038/nrg2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ward JL, Harris C, Lewis J, Beale MH. Phytochemistry. 2003;62:949–957. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00705-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiehn O, Kopka J, Dormann P, Altmann T, Trethewey RN, Willmitzer L. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:1157–1161. doi: 10.1038/81137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wheeler JM, Thomas JH. Genetics. 2006;174:1327–1336. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.059089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wold S. Pattern Recognit. 1976;8:127–139. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sohal RS. Free Radical Biol Med. 2002;33:573–574. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00885-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larsen PL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8905–8909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yancey PH. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:2819–2830. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schliess F, Gorg B, Haussinger D. Biol Chem. 2006;387:1363–1370. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicholson JK, Holmes E, Wilson ID. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:431–438. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brownlee M. Nature. 2001;414:813–820. doi: 10.1038/414813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeener J, Meier BH, Bachmann P, Ernst RR. J Chem Phys. 1979;71:4546–4553. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicholson JK, Foxall PJD, Spraul M, Farrant RD, Lindon JC. Anal Chem. 1995;67:793–811. doi: 10.1021/ac00101a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meiboom S, Gill D. Rev Sci Instrum. 1958;29:688–691. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piotto M, Elbayed K, Wieruszeski JM, Lippens G. J Magn Reson. 2005;173:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trygg J, Wold S. J Chemom. 2002;16:119–128. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.