Abstract

The transcription factor IRF4 is required during an immune response for lymphocyte activation and the generation of immunoglobulin-secreting plasma cells1-3. Multiple myeloma, a malignancy of plasma cells, has a complex molecular etiology with several subgroups defined by gene expression profiling and recurrent chromosomal translocations4,5. Moreover, the malignant clone can sustain multiple oncogenic lesions, accumulating genetic damage as the disease progresses6,7. Current therapies for myeloma can extend survival but are not curative8,9. Hence, new therapeutic strategies are needed that target molecular pathways shared by all subtypes of myeloma. Using a loss-of-function, RNA-interference-based genetic screen we show here that IRF4 inhibition was toxic to myeloma cell lines, regardless of transforming oncogenic mechanism. Gene expression profiling and genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis uncovered an extensive network of IRF4 target genes and identified MYC as a direct target of IRF4 in activated B cells and myeloma. Unexpectedly, IRF4 was itself a direct target of MYC transactivation, generating an autoregulatory circuit in myeloma cells. Though IRF4 is not genetically altered in most myelomas, they are nonetheless addicted to an aberrant IRF4 regulatory network that fuses the gene expression programs of normal plasma cells and activated B cells.

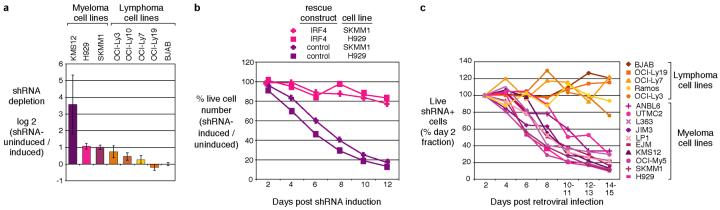

Recently, we developed a genetic method to identify therapeutic targets in cancer in which small hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) that mediate RNA interference are screened for their ability to block cancer cell proliferation and/or survival10. Here we report the results of such an “Achilles heel” screen in multiple myeloma (Supplementary Table 3). We used myeloma cell lines from three molecular subtypes: KMS12 (CCND1 translocation), H929 (FGFR3/MMSET translocation), and SKMM1 (MAFB, IRF4 translocations). Myeloma cells that received an shRNA targeting the coding region of IRF4 were depleted from cultures by 2-8 fold (Fig.1a). Lymphoma cell lines were largely unaffected by IRF4 knockdown, with the exception of OCI-Ly3, an activated B cell-like diffuse large B cell lymphoma line that expresses IRF4 highly11.

Figure 1. IRF4 is required for myeloma cell survival.

a, Cell lines were screened using a retrovirally-delivered, doxycycline-inducible, shRNA library to identify genes required for cell growth or survival, as described10. Depletion of cells bearing an IRF4-targeted shRNA in shRNA-induced versus uninduced cells is plotted; error bars represent the s.d. of triplicate measurements. b, Expression of the IRF4 coding region rescues myeloma cells from lethality of an shRNA targeting the IRF4 3'UTR (see text for details). c, An IRF4 shRNA is toxic to myeloma but not lymphoma cell lines. A vector for constitutive expression of IRF4 shRNA was transduced into cell lines, and viability of shRNA+ cells was monitored. In (b) and (c), cells expressing shRNA were monitored by flow cytometry for a co-expressed GFP marker and data were normalized to the % of GFP+ cells at day 2 post infection.

We next identified two additional shRNAs against IRF4 that were toxic to myeloma cell lines, one directed against the IRF4 3' untranslated region (UTR, Supplementary Fig.1). The toxicity of this shRNA was associated with a 50-75% decrease in IRF4 mRNA and protein (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b, c). Cell death occurred within 3 days, as measured by an increase in sub-G1 DNA content; there was, however, no effect on the cell cycle (Supplementary Fig. 2d, e, f, g). Expression of a cDNA containing only the coding region of IRF4 was able to rescue myeloma cells from the toxicity of the 3'UTR-directed IRF4 shRNA, confirming that the toxicity of this shRNA was specific (Fig.1b).

Strikingly, knockdown of IRF4 killed 10 myeloma cell lines, but had minimal effect on 5 lymphoma cell lines (Fig.1c). These myeloma lines bear many of the recurrent genetic aberrations typical of this cancer, including translocations of CCND1, MYC, MAF, MAFB, FGFR3: MMSET, NIK and IRF4, as well as RAS mutations, inactivation of TP53 and CDKN2C, and genetic abnormalities that activate the NF-κB pathway (Supplementary Table 1). Resequencing of the IRF4 coding exons in these lines revealed that 9 had a wild type sequence and one had a heterozygous mutation in exon 8 resulting in a missense substitution whose functional significance is unknown. Moreover, no amplification of the IRF4 locus was detected by array-based comparative genomic hybridization and no translocations involving IRF4 were detected by cytogenetics, with the exception of the previously documented IRF4 translocation in SKMM1 cells (data not shown). Thus, IRF4 dependency spans many myeloma subtypes and does not require genetic abnormalities in the IRF4 locus.

To understand the molecular basis for this dependency, we identified downstream targets of IRF4 by profiling gene expression changes in myeloma lines following induction of IRF4 shRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 3). A total of 308 genes were consistently downregulated following IRF4 knockdown (Supplementary Table 2). This list was significantly enriched for genes that are more highly expressed in primary myeloma samples than in normal mature B cells, based on gene set enrichment analysis12 of published gene expression profiling data (p=0.002 ; Fig. 2a)13 . Thus, IRF4 directs a broad gene expression program that is characteristic of primary myeloma cells.

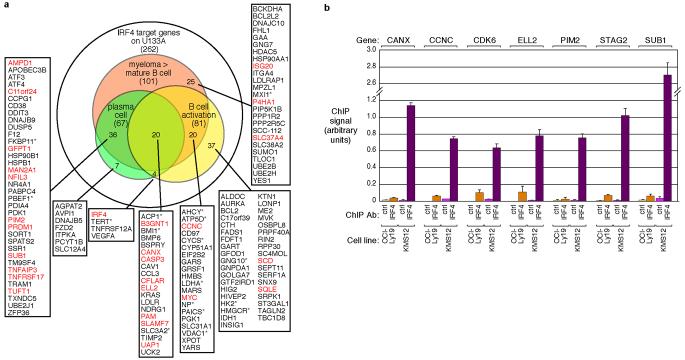

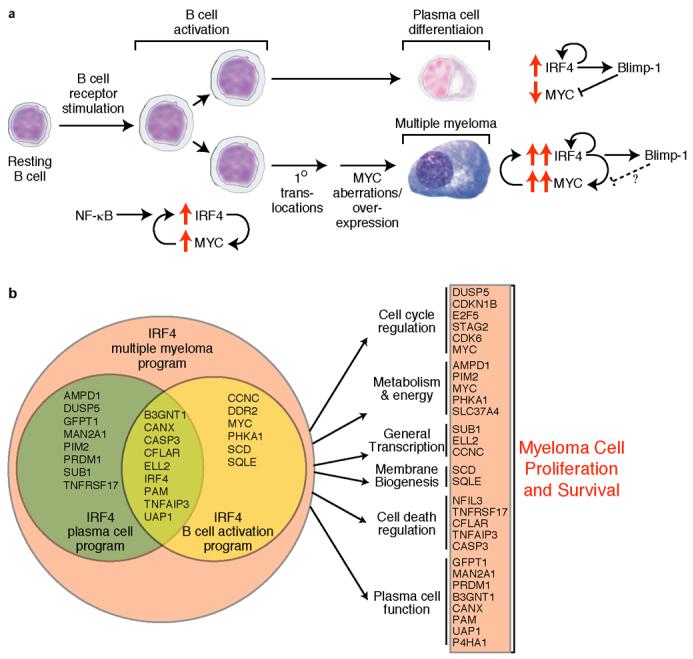

Figure 2. IRF4 target genes in multiple myeloma.

a, Venn diagram depicting IRF4 target genes and the overlap between the myeloma, plasma cell, and activated B cell gene expression programs. Of the 308 IRF4 target genes (Supplemental Fig. 3), 262 were well-measured on Affymetrix gene expression arrays. 101 were more highly expressed in primary myeloma samples than primary mature B cells (>1.4-fold, red circle), 67 were more highly expressed in primary plasma cells than mature B cells (>1.4-fold, green circle), and 81 are induced between 1 hr and 24 hr following activation of primary human B cells by anti-IgM crosslinking (>2-fold, yellow circle). red: direct IRF4 targets by ChIP, *: direct MYC targets. b, Representative conventional ChIP assays for genes identified as IRF4 targets by both gene expression profiling and ChIP-CHIP. Individual ChIP assays were performed on chromatin from the KMS12 myeloma line and the OCI-Ly19 lymphoma line using either anti-IRF4 or control antibodies. The ChIP signal is given in arbitrary relative units calculated from quantitative PCR data, based on the relative abundance of the indicated gene in the immunoprecipitated DNA versus input DNA. Error bars are s.d. from triplicate measurements.

We next investigated whether the IRF4 target genes in myeloma are also upregulated in other normal hematopoietic cells that require high IRF4 expression, including plasma cells3, mitogenically activated mature B cells1, and dendritic cells14. Human bone marrow-derived plasma cells expressed 22% of the IRF4 target genes at higher levels than mature blood B cells (Fig. 2a)13. Likewise, 25% of the IRF4 targets were more highly expressed in plasmacytoid dendritic cells than in monocytes (Supplementary Fig. 4)15. Blood B cells activated by anti-IgM crosslinking expressed one third of the IRF4 target genes more highly than resting B cells (Fig. 2a).

However, IRF4 regulates a broader set of genes in myeloma than in individual hematopoietic subsets. Roughly one quarter of the IRF4 target genes in myeloma were upregulated in activated B cells but not plasma cells, including genes known to be important in cellular growth and proliferation, such as MYC (Fig. 2a). Conversely, one sixth of the myeloma IRF4 target genes were highly expressed in plasma cells but not activated B cells.

To identify direct IRF4 targets, we performed genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP-CHIP), using DNA microarrays with probes spanning ∼10kb at the 5' end of 17,574 human genes. Specific IRF4 binding to 558 genes was detected in a myeloma cell line (KMS12) but not a lymphoma cell line (OCI-Ly19). Of these, 35 were also IRF4 targets by gene expression profiling, a highly significant overlap (p=1.0 × 10−16, Chi-square; Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 5), and were considered presumptive direct IRF4 targets (Supplementary Table 2). Direct binding of IRF4 was confirmed by conventional chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) for 22 genes, leading us to conclude that all 35 genes are likely IRF4 direct targets (Fig. 2b, and data not shown). This list of IRF4 direct targets is a conservative estimate since the ChIP-CHIP arrays interrogate limited regions around each gene. Indeed, direct ChIP experiments demonstrated that two other IRF4 target genes, PRDM1 and SQLE, were directly bound by IRF4 in regions not covered by our ChIP-CHIP analyses (Supplementary Fig. 5). IRF4 bound to the promoter and fourth intron of PRDM1, which encodes Blimp-1, another key regulator of plasmacytic differentiation (Supplementary Fig. 5). These observations support the proposal that IRF4 lies genetically upstream of PRDM1 in the regulatory hierarchy of terminal B cell differentiation3. Notably, IRF4 bound to its own promoter, supporting a positive feedback mechanism by which plasma cells can maintain high IRF4 expression3 (Supplementary Fig. 5).

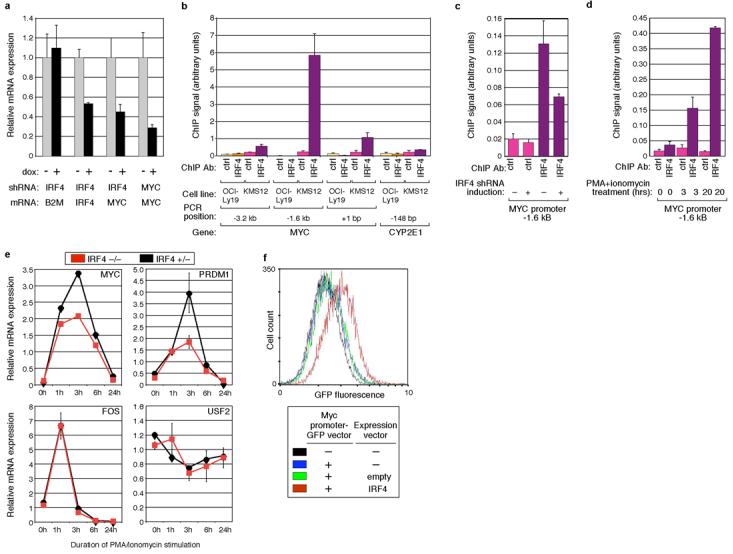

A direct IRF4 target of particular interest is MYC, given its prominent role in the pathogenesis of myeloma16. Knockdown of IRF4 reduced MYC mRNA levels by more than 2-fold in myeloma cell lines and caused MYC DNA binding activity to decrease in nuclear extracts of myeloma cells. Conversely, ectopic expression of IRF4 in a lymphoma cell line increased MYC mRNA levels (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 6). By ChIP, we surveyed regions of the MYC locus for binding by IRF4 in myeloma cells and detected a peak of binding around −1.6 kb upstream of the MYC start site, coinciding with a region detected by ChIP-CHIP (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig.7). Knockdown of IRF4 expression diminished the amount of IRF4 bound to this region of the MYC promoter (Fig. 3c). In human B cells, phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin (P/I) treatment induces transcription of IRF4 and MYC (data not shown). Correspondingly, a sharp increase in IRF4 binding to the MYC promoter was detected after 3 and 20 hours of P/I activation (Fig. 3d). Genetic evidence that Myc is an IRF4 target was provided by analysis of mitogenically-stimulated wild-type and IRF4-deficient mouse B cells (Fig. 3e). In IRF4-deficient cells, both Myc and Prdm1 failed to be fully induced by P/I treatment whereas the immediate early gene fos was normally induced, and a housekeeping gene, Usf2, did not change in expression. Finally, ectopic expression of IRF4 in a lymphoma cell line was able to transactivate a reporter construct in which GFP is under the control of the MYC promoter (Fig. 3f).

Figure 3. MYC is a direct IRF4 target gene in myeloma and activated B cells.

a, Knockdown of IRF4 decreases MYC mRNA expression. The SKMM1 myeloma line was transduced with IRF4 or MYC shRNAs, and gene expression was measured by quantitative RT-PCR after 4 days of shRNA induction, normalized to the signal from uninduced cells. b, Binding of IRF4 to the MYC promoter. ChIP was performed as in Figure 2, comparing the myeloma line KMS12 to the lymphoma line OCI-LY19, for regions of the MYC promoter (as indicated relative to the transcriptional start site) or a control locus, CYP2E1. c, IRF4 knockdown decreases IRF4 binding to the MYC promoter. ChIP was performed using KMS12 cells with or without shRNA induction for 4 days. d, Activation of human blood B cells leads to IRF4 binding to the MYC promoter. ChIP assays were performed using purified peripheral human blood B cells, either unstimulated or activated with P/I for the indicated times. e, Genetic deficiency of IRF4 impairs MYC induction during lymphocyte activation. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed on RNA from resting splenic B cells of IRF4-deficient or wild type mice, either unstimulated or activated with P/I for the indicated times. Values were normalized to B2M expression. f, IRF4 transactivates the MYC promoter. The OCI-Ly7 lymphoma line was transiently transfected with a GFP expression vector driven by the human MYC promoter, either alone, with an IRF4 expression vector, or with an empty vector control. Flow cytometry for GFP fluorescence is shown, with error bars indicating s.d. of triplicate measurements.

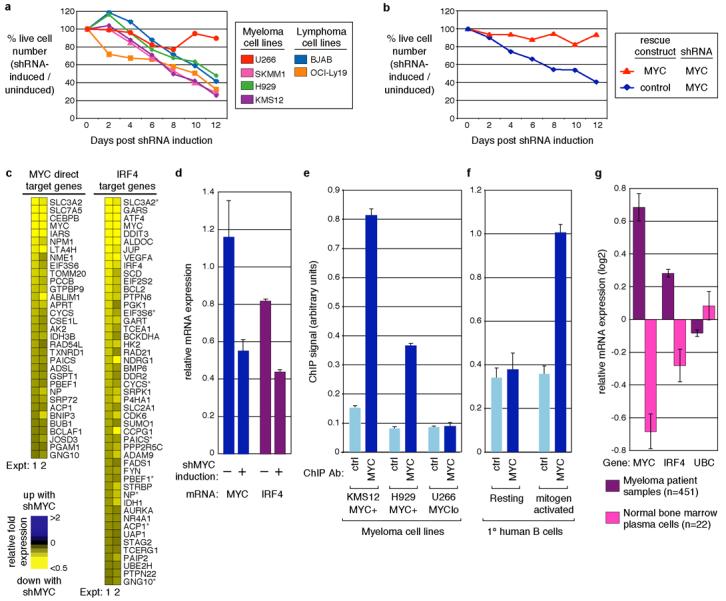

These data provide strong evidence implicating MYC as a direct target gene of IRF4. Accordingly, the list of IRF4 targets was highly enriched for genes that are directly transactivated by MYC17-19 (n=23; p=1 × 10−8, Chi-square; Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 9). These genes encode key components of glycolysis (LDHA, HK2, PDK1) and mitochondrial respiration (ATP5D, CYCS), as well as important regulators of cellular senescence (BMI1, TERT). Since MYC is a key coordinator of cellular growth, metabolism and proliferation20, we examined whether knockdown of MYC expression was toxic to myeloma cells. An shRNA targeting the MYC 3'UTR knocked down MYC expression and DNA binding by ∼2-fold (Supplementary Fig. 6). This shRNA was toxic to both myeloma and lymphoma cell lines but had little effect on the myeloma cell line U266, consistent with its high expression of MYCL1 instead of MYC (Fig. 4a)21. Expression of the MYC coding region was able to rescue cells from the toxicity of the MYC shRNA, confirming its specificity (Fig. 4b). Thus, loss of MYC expression may contribute to the toxicity of IRF4 shRNAs for myeloma cells.

Figure 4. IRF4 is a direct MYC target gene in myeloma and activated B cells.

a, Lethality of a MYC shRNA for cell lines expressing MYC. Cell lines were transduced with a MYC shRNA vector and the fraction of shRNA+ (GFP+) cells was monitored over time. All lines express MYC, except U266, which expresses MYCL1. b, Expression of the MYC coding region rescues H929 myeloma cells from lethality of an shRNA targeting the MYC 3'UTR. c, MYC knockdown downregulates MYC direct target genes and IRF4 target genes. KMS12 myeloma cells were induced for MYC shRNA expression for 4 days and profiled for gene expression changes. Each experiment utilized a different MYC shRNA. Exemplar array elements are shown (reduced by >1.3-fold in both experiments), for known MYC direct targets17 and IRF4 targets (this work). d, MYC knockdown decreases IRF4 mRNA expression. Shown are quantitative RT-PCR measurements of MYC and IRF4 mRNA levels in KMS12 myeloma cells, with or without induction of MYC shRNA. Error bars indicate s.d. of triplicate measurements. e, MYC binds to the IRF4 locus. ChIP of MYC binding to the IRF4 first intron in myeloma cells expressing MYC (KMS12, H929), but not in the myeloma line U266 that lacks MYC expression. f, MYC binding to the IRF4 locus is induced in activated human B cells. ChIP of MYC binding to the IRF4 first intron in human blood B cells, either unstimulated or activated with P/I for 6 hr. g, MYC and IRF4 are more highly expressed in primary myeloma patient samples than in normal human bone marrow plasma cells. Previously published gene expression profiling data4 was analyzed for mRNA expression of MYC, IRF4, and a control gene, UBC.

Using two independent MYC shRNAs, we identified the targets of MYC in myeloma cells. Following MYC shRNA induction, the expression levels of many direct MYC targets decreased (Fig. 4c). Unexpectedly, the expression of IRF4 also decreased, as did the expression of many IRF4 target genes (Fig. 4c, d). ChIP demonstrated binding of MYC to a region of the IRF4 first intron in two myeloma cell lines expressing MYC (KMS12, H929) but not in a cell line with very low MYC expression (U266, Fig. 4e). Further, we detected MYC binding to IRF4 in mitogenically activated B cells, which express MYC, but not resting B cells, which do not (Fig. 4f).

These data reveal a positive regulatory loop in myeloma cells in which IRF4 and MYC mutually reinforce each other's expression (Fig. 5a). In keeping with this model, myeloma patient samples express both MYC and IRF4 mRNA more highly than normal plasma cells (p=5.1 × 10−7 for IRF4; Fig. 4g). Moreover, MYC and IRF4 mRNA levels showed significant positive correlation across 451 primary myeloma samples4 (r= 0.24, p=2.5×10−7, Supplementary Fig. 7). This moderate correlation was remarkable since IRF4 is likely to be only one of many factors regulating MYC transcription in myelomas22. Although the MYC locus in myeloma is often amplified and inserted at ectopic genomic locations, especially within and near the immunoglobulin loci16, the MYC breakpoints in these chromosomal rearrangements are many kilobases from the MYC transcriptional start site and thus preserve the IRF4 binding region. Our data suggest that the oncogenic activation of MYC in myeloma upregulates IRF4, which in turn drives expression of MYC and other IRF4 target genes (Fig. 5a).

Figure 5. Model of IRF4 control over B cell development and multiple myeloma oncogenesis.

a, IRF4 and MYC form a positive autoregulatory loop during normal B cell activation and in multiple myeloma. Genetic abnormalities of MYC upregulate its expression in myeloma, thereby augmenting IRF4 expression. In normal plasma cells, Blimp-1 represses MYC, but this control circuit may be abrogated in myeloma. b, IRF4 as a master regulator of the myeloma phenotype. IRF4 controls a myeloma-specific gene expression program that fuses the IRF4 regulatory programs from activated B cells and plasma cells. IRF4 direct targets regulate many essential cellular processes, causing myeloma cells to be addicted to IRF4.

In some respects, the dependency of myeloma cells on IRF4 is reminiscent of the function of “lineage-survival” oncogenes23. These genes are primarily transcription factors that provide essential functions in a particular cellular lineage but are also dysregulated in cancers derived from that lineage. IRF4 differs from lineage survival oncogenes in two respects. First, many lineage survival oncogenes are altered by mutations or chromosomal structural alterations whereas the IRF4 locus appears to be unaltered in most myelomas. Second, the regulatory network that IRF4 controls in myeloma is decidedly abnormal, not merely reflecting the genetic program of normal plasma cells but also borrowing from the genetic program of antigen-stimulated mature B cells (Figs. 2a, 5b). This transcriptional promiscuity is exemplified by the direct IRF4 targets MYC, SCD, SQLE, CCNC, and CDK6, which are not highly expressed in normal plasma cells but are upregulated in mature B cells upon antigen receptor signaling (Figs. 2a, 5b). Thus, myelomas have broadened the genetic repertoire of IRF4, perhaps due to epigenetic alterations that allow IRF4 access to loci that are normally silenced in plasma cells. Hence, the dependency of myeloma on IRF4 may be best described as “nononcogene addiction” i.e. the aberrant function of a normal cellular protein that is required for cancer cell proliferation or survival24.

The direct targets of IRF4 reveal it to be a master regulator influencing metabolic control, membrane biogenesis, cell cycle progression, cell death, transcriptional regulation and plasmacytic differentiation (Fig. 5b). Given this pleiotropic program, we believe that loss of IRF4 in a myeloma cell results in “death by a thousand cuts”. For example, several key cell cycle regulators are IRF4 targets, in keeping with its role in lymphocyte activation1, including STAG2, CDK6, and MYC. STAG2 encodes a component of the cohesin complex crucially involved in the segregation of chromosomes during mitosis25. Two different shRNAs targeting STAG2 were toxic for both a myeloma and a lymphoma cell line (Supplementary Fig. 8), as were shRNAs targeting MYC (Fig. 4a). Likewise, myeloma cells were specifically killed by 2 different shRNAs targeting SUB1, an IRF4 direct target that encodes a transcriptional coactivator26. It seems likely, therefore, that decreased expression of each of these IRF4 direct targets contributes to IRF4 shRNA toxicity. A prominent role for IRF4 in regulating membrane biogenesis was indicated by the many enzymes and regulators of sterol and lipid synthesis under its control (Supplementary Fig. 9), including SQLE and SCD, which encode rate-limiting enzymes in these pathways. Further, the IRF4 target gene set was strikingly enriched for genes encoding components of glucose metabolism and ATP production, many of which are targets of MYC (Supplementary Fig. 9). It is therefore plausible that metabolic collapse also contributes to cell death caused by IRF4 deprivation.

Our data demonstrate that myelomas are addicted to an abnormal regulatory network controlled by IRF4, irrespective of their molecular subtype and underlying oncogenic abnormalities. Hence, IRF4 emerges as a master regulator of an aberrant and malignancy-specific gene expression program relevant to all molecular subtypes of this cancer. Since mice lacking one allele of irf4 are phenotypically normal1 and since a ∼50% knockdown of IRF4 mRNA and protein was sufficient to kill myeloma cell lines, a therapeutic window may exist in which IRF4-directed therapy might kill myeloma cells while sparing normal cells. Though transcription factors have been considered intractable therapeutic targets, recent successful targeting of p5327 and BCL-628 provides hope that IRF4 can be exploited as an Achilles heel of multiple myeloma.

METHODS SUMMARY

Lines were engineered to express the ecotropic retroviral receptor and the bacterial tetracycline repressor as described10. The retroviral constructs for shRNA expression and the design of shRNA library sequences have been described10; in some vectors, the puromycin selectable marker (puro) was replaced by a fusion between puro and green fluorescent protein (GFP) for tracking by flow cytometry. Doxycyline (20 ng/ml) was used for shRNA induction. IRF4 and MYC were expressed using retroviral vectors as described3. Primary human resting blood B cells were purified by magnetic separation (CD19+ beads Miltenyi) and grown at 2 million cells/ml in IMDM+10%FBS; primary mouse splenic, resting B cells were purified by magnetic separation (B cell kit, Miltenyi) and grown at 2 million cells/ml in RPMI+10%FBS. Lymphocytes were activated with PMA (40 ng/ml) and ionomycin (2μM). Gene expression profiling was performed using Agilent 4×44k or Lymphochip29 microarrays. ChiP-CHIP experiments were performed using Agilent Human Promoter Set microarrays.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. We wish to thank Kathleen Meyer for her assistance with GEO submissions, David Levens, Juhong Liu, Hye-Jung Chung for assistance with MYC ChIP assay design and the MYC promoter-GFP reporter construct, Keiko Ozato and Lakshmi Ramakrishna for IRF4-deficient mice, and Mike Kuehl and the members of the Staudt lab for their assistance and helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Full Methods are available in the Supplementary Materials in the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of this paper at www.nature.com/nature.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Mittrucker HW, et al. Requirement for the transcription factor LSIRF/IRF4 for mature B and T lymphocyte function. Science. 1997;275:540–3. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5299.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein U, et al. Transcription factor IRF4 controls plasma cell differentiation and class-switch recombination. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:773–82. doi: 10.1038/ni1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sciammas R, et al. Graded expression of interferon regulatory factor-4 coordinates isotype switching with plasma cell differentiation. Immunity. 2006;25:225–36. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhan F, et al. The molecular classification of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108:2020–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-013458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergsagel PL, et al. Promiscuous translocations into immunoglobulin heavy chain switch regions in multiple myeloma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:13931–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuehl WM, Bergsagel PL. Multiple myeloma: evolving genetic events and host interactions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:175–87. doi: 10.1038/nrc746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrasco DR, et al. High-resolution genomic profiles define distinct clinicopathogenetic subgroups of multiple myeloma patients. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:313–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barlogie B, et al. Treatment of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2004;103:20–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitsiades CS, Mitsiades N, Munshi NC, Anderson KC. Focus on multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:439–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ngo VN, et al. A loss-of-function RNA interference screen for molecular targets in cancer. Nature. 2006;441:106–10. doi: 10.1038/nature04687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis RE, Brown KD, Siebenlist U, Staudt LM. Constitutive Nuclear Factor kappaB Activity Is Required for Survival of Activated B Cell-like Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma Cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1861–1874. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.12.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subramanian A, et al. From the Cover: Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutierrez NC, et al. Gene expression profiling of B lymphocytes and plasma cells from Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia: comparison with expression patterns of the same cell counterparts from chronic lymphocytic leukemia, multiple myeloma and normal individuals. Leukemia. 2007;21:541–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamura T, et al. IFN regulatory factor-4 and -8 govern dendritic cell subset development and their functional diversity. J Immunol. 2005;174:2573–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su AI, et al. A gene atlas of the mouse and human protein-encoding transcriptomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6062–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400782101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shou Y, et al. Diverse karyotypic abnormalities of the c-myc locus associated with c-myc dysregulation and tumor progression in multiple myeloma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:228–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeller KI, et al. Global mapping of c-Myc binding sites and target gene networks in human B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17834–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604129103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guney I, Wu S, Sedivy JM. Reduced c-Myc signaling triggers telomere-independent senescence by regulating Bmi-1 and p16(INK4a) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3645–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600069103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim JW, Gao P, Liu YC, Semenza GL, Dang CV. HIF-1 and Dysregulated c-Myc Cooperatively Induces VEGF and Metabolic Switches, HK2 and PDK1. Mol Cell Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1128/MCB.00440-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dang CV, et al. The c-Myc target gene network. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:253–64. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dib A, Gabrea A, Glebov O, Bergsagel PL, Kuehl WM. Characterization of MYC translocations in multiple myeloma cell lines. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007 doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgn011. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu J, Levens D. Making myc. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;302:1–32. doi: 10.1007/3-540-32952-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garraway LA, Sellers WR. Lineage dependency and lineage-survival oncogenes in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:593–602. doi: 10.1038/nrc1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solimini NL, Luo J, Elledge SJ. Non-oncogene addiction and the stress phenotype of cancer cells. Cell. 2007;130:986–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hauf S, et al. Dissociation of cohesin from chromosome arms and loss of arm cohesion during early mitosis depends on phosphorylation of SA2. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e69. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ge H, Roeder RG. Purification, cloning, and characterization of a human coactivator, PC4, that mediates transcriptional activation of class II genes. Cell. 1994;78:513–23. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vassilev LT, et al. In vivo activation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule antagonists of MDM2. Science. 2004;303:844–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1092472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polo JM, et al. Specific peptide interference reveals BCL6 transcriptional and oncogenic mechanisms in B-cell lymphoma cells. Nat Med. 2004;10:1329–35. doi: 10.1038/nm1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alizadeh AA, et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403:503–511. doi: 10.1038/35000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.