Summary

Characterization of unfolded states, while critical to a complete understanding of protein folding, is inherently difficult due to structural heterogeneity and dynamic interchange between states. Equilibrium fluorescence studies of single molecules or tens of molecules are beginning to be applied to studies of unfolded proteins. These methods can obtain conformational information about individual subpopulations of molecules in an ensemble, and measure dynamics without the need for synchronizing the molecules, The studies highlighted here demonstrate the promise of these techniques for obtaining novel information about unfolded states in vitro and in more physiologically relevant milieu.

Introduction

A complete understanding of protein folding requires not only characterization of the folded and functional forms of proteins, but also a description of the structures and dynamics of the unfolded ensemble. The earliest steps of folding likely involve intramolecular contacts formed in the denatured states, and while these contacts may be transient, they may also play a critical role in the folding process.

Unfolded states are complicated to study due to their inherent heterogeneity, lack of stable, well-defined structures, and dynamic motions of the protein chain over a range of timescales. For very fast dynamics, on the timescale of the excited-state lifetime of the probe, time-resolved luminescent methods have been applied with great success to characterize transiently populated states and dynamics of both proteins and model polypeptides (Reviewed in [1–3] ). NMR has also proven to be a powerful technique for the study of disordered proteins, particularly in its ability to provide information about dynamics over a range of timescales and atomic resolution characterization of regions of local structure in an otherwise disordered protein (Reviewed in [4]).

Single molecule fluorescence methods are ideal for studying denatured states because they uniquely allow for independent analyses of the signals from different conformational subpopulations. Denatured populations can thus be studied in native-like conditions where signals from the folded proteins would otherwise dominate. In this review we focus on recent developments in the application of fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) and single molecule Förster resonance energy transfer smFRET to the characterization of the conformations and dynamics of denatured proteins. In these closely related methods, global or local structural fluctuations of a denatured protein can be quantified by observing changes in the emission of a fluorescent probe or probes attached to the protein (Box 1). We will present and briefly discuss examples where these methods have been used to measure the dimensions of denatured states, investigate the presence of residual structure, and determine the relevance of chain dynamics on a range of timescales.

Box 1

Mechanisms for detecting chain dynamics in denatured proteins. Fluorescence studies of chain dynamics probe conformationally-sensitive fluorophores whose quantum efficiencies are mediated by their surrounding environments. The two main mechanisms for conformational sensitivity are FRET and quenching. (A) In FRET, the efficiency of transfer is dependent upon the distance between the donor and acceptor molecules to the sixth power [66]. Typically both the donor and the acceptor molecules are fluorescent, but it is also possible to use a non-fluorescent molecule as the acceptor. Quenching can occur by two primary mechanisms: (B) In photoinduced electron transfer (PET) the excited fluorophore donates or accepts an electron from the quencher, and returns to the ground state without emission of a photon. For the FCS experiments described here, the quenching molecule is a single residue or a number of residues in the protein chain, which may or may not be identifiable [67]. (C) Self-quenching occurs due to intermolecular interactions that take place when two identical fluorophores come into close proximity [68]. Quenching requires almost van der Waals contact of the fluorophore and quencher, whereas FRET occurs over longer distances, typically 10–100 Å with commonly used fluorophores. In a completely denatured protein where close contact between probe molecules may be too transient or infrequent for a significant fluctuation signal to be detected, FRET can measure dynamics that may not result in contact between two molecules. Lastly, FRET acceptor emission intensity is dependent on its separation from the donor, whereas quenching involves complete absence of photon emission.

Experimental Approaches

Single Molecule Förster Resonance Energy Transfer, smFRET

FRET occurs via a non-radiative dipole-dipole interaction between the donor and acceptor fluorophore (Box 2). The efficiency of transfer is strongly dependent upon the distance between the two fluorophores making it a powerful tool for measuring inter- and intramolecular distances [5]. Time-resolved FRET (trFRET) and smFRET share the ability to characterize heterogeneous populations and detect rapid chain motions, and the application of trFRET to protein folding and dynamics has been reviewed recently [1,2]. While the number of publications featuring smFRET is growing rapidly, the technique is still in its infancy when applied to protein folding studies. A number of recent reviews that focus on smFRET studies of protein folding provide excellent background to the technique and its strengths and difficulties that will not be covered in this contribution [6– 8].

Box 2

Representations of smFRET efficiency histograms as a function of denaturant concentration. In smFRET measurements, the observation or sampling time, and thus resolution of the measurement, is determined by the duration of the time bins in which photons are collected. For diffusion studies, 1–2 ms time bins are chosen to help ensure that only a single protein is observed at a time, whereas with immobilized molecules, larger time bins are necessary to reduce noise.

Generally, for each photon ‘burst’ or at each timepoint of an intensity trace, the FRET efficiency is calculated as a ratio of the number of acceptor photons over the total photons detected in donor and acceptor channels. The raw photon counts must be corrected for background signal, direct excitation of the acceptor fluorophore, ‘leaking’ of the donor signal into the acceptor channel, and differences in quantum yields of the fluorophores and quantum efficiencies of the detectors [7,34,69]. FRET efficiencies are compiled into histograms which are then fit to Gaussian or related functions to extract parameters of interest, including the mean FRET efficiency and the width of the distribution. (A) For a two-state folding protein, assuming the folding rate is sufficiently slower than the sampling time, two peaks are detected, which are assigned to the folded and unfolded populations. At low denaturant concentrations, the folded peak dominates (black), whereas high denaturant favors the unfolded protein (red). (B) Important information about both the structures and dynamics of unfolded proteins can be extracted from the mean FRET efficiency and the width of the peak associated with the denatured population.

Though FRET is often referred to as a “spectroscopic ruler” due to its potential to determine exact distances, in single molecule studies it has typically been used to measure relative as opposed to absolute distances. Obtaining quantitative parameters from FRET measurements is a topic of much interest and was recently addressed in detail in a review on smFRET studies of protein folding [8]. For applications to disordered proteins, there are two concerns of particular importance: (1) The calculated FRET efficiency depends upon the dipole orientations of the donor and acceptor molecules, and while it is frequently assumed that the fluorophores experience free rotation, this may not be a valid assumption in denatured proteins where hydrophobic dyes may be more likely to interact with the exposed hydrophobic regions of the protein chain; and (2) Denatured protein chains may undergo some very rapid dynamics, on the order of the lifetime of the fluorophores, which could affect the calculated FRET efficiency values [70].

Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy, FCS

Though it was experimentally realized nearly 40 years ago [9,10], FCS only became a powerful tool for biochemical and biophysical characterization when technological advances produced stable lasers and single photon detectors. As the theory and experimental implementation of FCS have already been covered in detail in many excellent reviews [7,11–13], we will only briefly review key features. In FCS, the temporal autocorrelation of spontaneous fluctuations in fluorescence intensity yields quantitative parameters associated with concentration, diffusion, and chemical or photophysical kinetics of the observed species (Box 3). It is commonly used to analyze diffusion behavior, which is dependent upon the hydrodynamic radius, Rh, of the diffusing species. This approach has been used to study protein folding, where the transition from the extended denatured state to a compact native one results in a decrease in the diffusion time [13–15]. However, conformational changes that do not result in significant change in Rh can also be detected if they modulate emission of the fluorophore via FRET or quenching mechanisms (Box 1). Measurements of both the diffusion time and chain dynamics are of interest for studies of disordered proteins by FCS [13]. While FCS is not strictly a single molecule technique, it can be carried out at the single molecule level and is most sensitive for studies of <100 molecules.

Box 3

Using FCS to measure protein dimensions and dynamics. In FCS, the fluorescence intensity is temporally-correlated and appropriate analytical functions are fit to the resulting curve. For a single diffusing protein in three dimensions, in the absence of other dynamic processes, the autocorrelation function is given by:

| Equation 1 |

where N is the average number of molecules, τD is the diffusion time, and ω is the ratio of axial to radial dimensions of the observation volume. As a protein unfolds it will diffuse more slowly, resulting in a shift of G(τ) to the right (black curves).

The simplest case of intrachain dynamics can be modeled as an isomerization between two states, one fluorescent and one dark. The resulting autocorrelation curves are fit by:

| Equation 2 |

where A is the fraction of molecules in the dark state (often referred to as the amplitude of the fluctuation) and τA is the time constant of the motion, both of which can be written in terms of the forward and backward rate constants of the isomerization [12,71]. In this plot, the effect of increasing A (for a fixed τA) can be seen in the increasing amplitude of the red curves, whereas the effect of increasing τA (for a fixed A), results in a shift to the right at short times of the blue curves. Note that all the curves converge at longer timescales associated with diffusion.

It is theoretically possible to measure dynamics ranging from ns to seconds. In practice, very short timescales are dominated by noise or afterpulsing of the photon detectors. Splitting the fluorescence emission and cross-correlating the resulting signals allows for resolution as high as 10’s of ns [62,67]. At longer times, τA is only distinguishable from τD if it is roughly an order of magnitude faster, placing an upper limit on τA of hundreds of µs for most proteins, though approaches for extending the observation time of diffusing molecule are being developed[72]. Furthermore, triplet state dynamics of a fluorophore can appear as correlated fluorescence fluctuations in the µs region of G(τ) [73]. These photophysical effects can be distinguished from dynamics as they are dependent upon the excitation intensity of the laser, whereas chain motions are not.

Because the expression used to fit FCS curves is derived assuming a 3D Gaussian focal volume, changes in the refractive index of the solution due to high concentrations of denaturant may result in aberrations that complicate data analysis. Two recent papers present methods for characterizing the effects of and correcting for the presence of denaturants in FCS measurements [74,75].

Dimensions of the denatured state

The predominant model for describing the denatured states of proteins has long been the Gaussian random coil; based on this model, the radius of gyration, Rg, of a denatured protein is expected to scale with the number of residues, N, as follows: Rg=RoN0.588 [16]. Experimental support for this theoretical model comes largely from small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) experiments that show that denatured protein dimensions agree with those predicted for a similarly sized random coil [16]; historically, this has been interpreted as the absence of residual structure. In recent years, however, convincing spectroscopic experiments, primarily from NMR, show that some denatured proteins display considerable amounts of secondary structure [17–20]. These findings are supported by computational studies that demonstrate that the presence of local, native-like structure is not incompatible with end-to-end distances and Rg predicted by the random-coil model [21–24]. The existence of residual structure in denatured proteins is of extreme interest to the protein folding community, as the presence of even transient residual structure in the denatured state could have a profound effect on protein folding rates.

Interpretation of the peak shift of the unfolded population

A shared feature of the proteins studied thus far by smFRET is a shift of the average value of unfolded peak in the FRET efficiency histogram (Box 2, panel A) to higher values (smaller distances) with decreasing denaturant concentrations (Box 2, panel B) [15,25–30]. This behavior may not be unexpected, as both experimental evidence and predictions from computer simulations indicate that upon transfer from a good solvent (high denaturant concentration) to a poor solvent (low denaturant concentration or buffer), a protein chain will collapse from a random coil to a more compact albeit denatured structure. An open question is whether this transition is separate from or concurrent with the actual folding transition, particularly in the case of small proteins, where a number of SAXS studies have found no evidence for collapsed denatured states in small, two-state folding proteins [31,32].

With a microfluidic device, Lipman et al. used smFRET to measure the time-resolved folding of a small cold shock protein, CspTm, and found that intramolecular distances of the unfolded state decreased within the deadtime of the device (100ms), faster than the folding time of the protein, with no evidence of further compaction at subsequent timepoints [33]. In their study of Protein L (PL), where both smFRET and FCS indicate a compact denatured state at low GdnHCl concentrations, Sherman et al. used a mean field theory to model the compaction as a coil-globule transition, measuring a collapse transition that was thermodynamically distinct from the folding transition point of the protein [15]. It is possible that observations of compact denatured states by smFRET and the lack thereof by SAXS are not general features of proteins, but dependent upon the particular solvation properties of the proteins thus far studied. However, it is notable that two groups independently observed a compact denatured state for PL in low denaturant concentrations by smFRET [15,27] whereas SAXS experiments found no evidence for collapse under the same conditions [32].

While proteins in high concentrations of denaturant may be expected to behave as random coils, of particular interest are the dimensions of the unfolded states in low denaturant concentrations. Kuzmenkina et al. modeled the denatured state of RNase H as a continuum of unfolded substates, which allowed them to extract various energetic parameters, as well as Rg, from their measurements [26]. The Rg values were found to be in good agreement with results from NMR and SAXS measurements over the range of denaturant concentrations, with the most compact denatured state only ~30% larger than the native state of the protein, similar to the degree of enlargement estimated by Sherman et al. for the collapsed denatured state of PL [15]. Another study which compared PL and CspTm found that the dimensions of the protein were similar at high denaturant concentrations, consistent with a random coil; more striking was the observation that despite their similar chain lengths, PL was more compact than CspTm at low denaturant concentrations [27]. These findings appear to corroborate NMR and ensemble FRET studies that find partial structure of PL in the denatured state, as opposed to CspTm, where there is no evidence for unfolded state structures.

Probing multiple regions of the unfolded protein

Placing donor-acceptor pairs at multiple positions within the same protein allows for probing of specific contiguous regions of the protein chain, and thus a view both of the global and local structure of the unfolded states. This approach was used to probe 20–56 residue segments of the protein FynSH3 in 4 M GdnHCl [34]. The authors found that the calculated Rg values were in good agreement with those expected for random coils comparable to the length of each protein segment, although they suggest that potentially significant deviations at specific sites may be attributed to residual secondary structure, which has been observed with NMR [35]. Using the same multiple probe approach in a more extensive study of CspTm, Schuler and coworkers found good agreement with random coil structure both for measurements at high denaturant concentrations, as well as at low denaturant concentrations when the protein is collapsed [36]. Kinetic measurements using synchrotron radiation circular dichroism spectroscopy revealed significant amounts of β-sheet structure in the collapsed state, leading the authors to conclude what had been suggested by computational simulations, namely that the presence of secondary structure was not incompatible with the global random coil dimensions of CspTm.

Measuring conformational dynamics in unfolded proteins

Using FCS to measure dynamics

Frieden and coworkers were the first to use FCS to measure protein conformational dynamics in a study of intestinal fatty acid binding protein (IFABP) [13]. A fluctuation with a decay time of ~30–45 µs was measured, which was attributed to quenching by a tryptophan residue located in close proximity to the fluorophore in the native state. Persistence of the fluctuation in the acid denatured protein, combined with the compactness of this state as measured by its diffusion time, was interpreted to mean that the unfolded state contained or sampled some native-state topology. Altering their approach to use self-quenching of two tetramethyl rhodamine molecules as a probe, they detected fluctuations of 1.6 µs in 3M GdnHCl [37]. The amplitude of the fluctuations displayed the same sigmoidal increase with denaturant concentration as steady-state fluorescence measurements, confirming that the dynamics measured were associated with the denatured state. Furthermore, motion was determined to be diffusive in nature, as the measured fluctuation time followed the predicted linear dependence on solution viscosity; the dynamics were slower at low pH and in the presence of salt, where CD showed increased secondary structure, reflecting hindrance of diffusive motion by the residual structure. The ~µs fluctuations measured were roughly in agreement with contact rates observed for other small proteins [38,39], though significantly slower than the nanosecond contact rates predicted by homopolymer models [40], demonstrating the potential relevance of transient structures formed by more complex protein chains in determining contact and folding rates.

Other studies demonstrate the range of dynamics possible in the denatured state. Rischel et al. observed progressive quenching of Alexa 488 labeled cytochrome via energy transfer to the heme group as the protein folded [41]. Although they were unable to detect fluctuations of the denatured protein by FCS, modeling autocorrelation curves allowed them to conclude that the fluctuations responsible for quenching must be faster than 4 µs. A study of acid denatured apomyoglobin revealed fluctuations on three distinct timescales ranging from 3–200 µs [14]. The observation of such slow dynamics in the denatured protein were supported by predictions from NMR for µs-ms contacts between specific protein segments known to sample compact conformations under denaturing conditions [42,43].

Using FRET to measure dynamics

For many proteins, the width of the denatured peak in the FRET efficiency histogram, which is a source of much discussion and the focus of interesting theoretical studies [44,45], has been related to dynamics of the unfolded proteins. In early smFRET folding studies, the width in excess of what was predicted for shot noise was attributed to denatured state dynamics of the protein on a timescale greater than the sampling time [25,46]. Eaton and coworkers, on the other hand, concluded that chain dynamics were not a source of peak broadening in denatured CspTm based on comparable measurements of polyproline, which was assumed to behave as a rigid rod [28]. However, subsequent work from several groups found evidence for dynamics and structural heterogeneity in polyproline [47–49]. Recently, in a study that combined smFRET with fluorescence lifetime measurements and simulations, Eaton and coworkers attributed broadening of the denatured state distribution in both CspTm and PL to slow dynamics that result in incomplete sampling of the accessible conformational states during the 1–2 ms observation times [27].

Based on FRET efficiency histograms compiled from time traces of immobilized RNase H (Figure 1B and upcoming text), Kuzmenkina et al. concluded that the distribution in the calculated Rg values of the denatured protein was due to fluctuations between many conformational states, rather than a broad distribution of static conformations [50]. Additional dynamic information can be obtained from folding trajectories by cross-correlation of the donor and acceptor signals to resolve events that are faster than the time bins. With this approach, in addition to the slow dynamics obtained from smFRET trajectories, a 20 µs relaxation time was observed and used to estimate the height of the unfolded state free energy barrier [50]. Interestingly, they also found that the width of the unfolded FRET efficiency peak decreased as the GdnHCl concentration was increased through the folding transition mid-point [26]. The authors interpreted this as evidence of less heterogeneity in the unfolded population at high denaturant, which may be supported by the observation of Sherman et al. that high denaturant concentrations results in an increased persistence length and thus a more rigid protein chain [15]. Laurence et al. observed a similar broadening of the FRET efficiency peak in the compact denatured states of both chymotrypsin inhibitor 2 (CI2) and acyl-CoA binding protein (ACBP) which they attributed to dynamic sampling of residual structure in the denatured state [30].

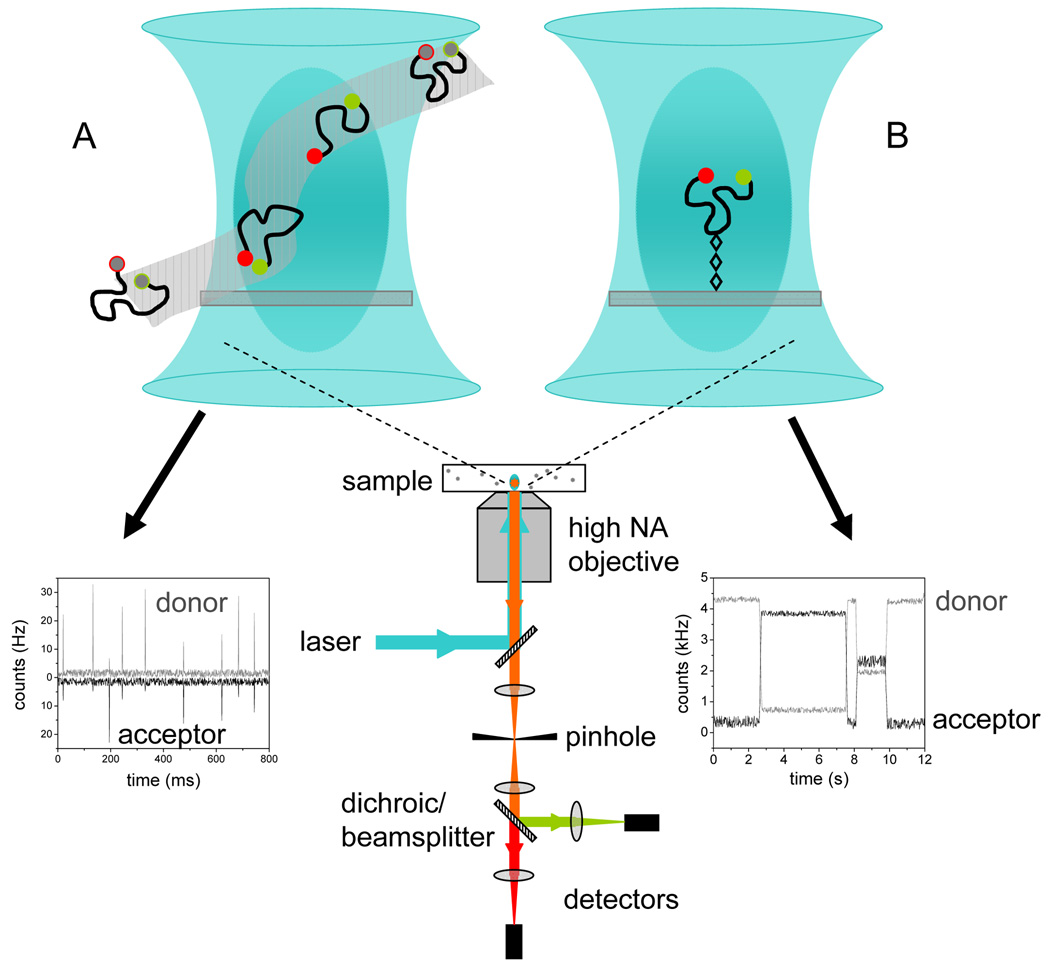

Figure 1.

Schematic of typical setup for smFRET or FCS. A laser, most commonly CW (although pulsed lasers which allow for TCSPC measurements have being used in a number of recent studies [27,30,36] is focused by a high NA (>0.9) objective lens to a diffraction-limited focal volume (~10−15 liter). Emitted fluorescence is collected through the objective, separated from the excitation beam by a dichroic mirror and focused onto a confocal aperture that provides depth discrimination. Donor and acceptor signals are separated by dichroic mirrors in smFRET or by a beamsplitter for cross-correlation of the signal in FCS before detection. (A) Measurements of freely diffusing molecules (pM for smFRET and nM for FCS) results in ‘bursts’ of photons which are further processed, as described in Box 2 and Box 3. (B) A single immobilized molecule must be first detected and localized in the focal volume to allow for measurement of an intensity trace, which typically lasts for a few seconds before photobleaching. A total internal reflection (TIR) setup, not shown here, allows for simultaneous measurement of intensity traces from multiple immobilized molecules albeit with reduced time resolution (see [7] review for further discussion).

Measuring at the extremes: very slow and very fast dynamics

As discussed above, excessive width of unfolded FRET efficiency peak has been attributed to incomplete conformational sampling, due to dynamics slower than the measurement sampling time. An extended observation time obtained by immobilizing the proteins is required to observe these slow dynamics (Figure 1B). Based on early observations that direct adsorption perturbs the denatured state conformations [46], recent approaches have focused on minimizing perturbations. Haran and coworkers encapsulated single proteins insides lipid vesicles, which were immobilized by tethering to a coverslip using biotin-avidin linkage [51]. In their folding studies of adenylate kinase, AK, they observed conformational changes in the denatured state of AK over a range of timescales, including very slow transitions that took place over several seconds [52]. Nienhaus and coworkers used biotin-avidin to directly tether proteins to a coverslip coated with cross-linked ‘star’ shaped poly(ethylene glycol) [53]. Using this method, they observed conformational changes within the denatured state of RNase H with a transition rate of ~0.4 s−1 [50]. Interestingly, although they become more infrequent, transitions between unfolded sub-states persisted with increasing denaturant concentrations, implying the existence non-random residual structures even in high denaturant concentrations.

More recently, Cohen and Moerner introduced an electrokinetic method for trapping molecules in solution that does not require surface attachment [54]. While this method is not currently capable of trapping small proteins, it has been used to localize the large bacterial chaperonin, GroEL, [55] and shows potential for application to protein conformation studies.

At the other extreme are rapid chain motions in the range of tens of nanoseconds, which have been observed in polypeptides [56–58] and may also be relevant for small denatured proteins or ultrafast folding proteins. The use of picosecond lasers allowed Schuler and coworkers to calculate a very high time-resolution autocorrelation function based on photon arrival times [59]. They measured a reconfiguration time in denatured CspTm of ~50 ns, which agrees with predictions for an ideal Gaussian chain, and supports the view that denatured state collapse of CspTm is a barrierless process. When they combined the ns resolution of their approach with traditional FCS, they did not observe any µs fluctuations in denatured CspTm [60]. These results are supportive of the view that the unfolded state of CspTm displays only rapid, diffusion-limited dynamics, in particular contrast to the very slow dynamics measured in other proteins discussed here.

Conclusions

While FCS and smFRET have contributed to our understanding of the structures and dynamics of chemically denatured proteins, they can be applied to a broader range of proteins than the ones currently being studied. Indeed, in single molecule folding studies, proteins other than two-state folders have largely been ignored. While two-state proteins serve as good models for folding studies, the complexities of the folding problem warrant a wider range of subjects. For example, the growing number of proteins classified as natively unstructured are overrepresented in proteins associated with cancers and neurodegenerative diseases (Reviewed in [61]), where their structural plasticity may be key to both their native and disease-associated functions.

Of particular relevance to many amyloid-associated diseases, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, is the transformation of proteins from a disordered soluble state to insoluble aggregated fibers. Both FCS and smFRET are promising methods for characterizing proteins that aggregate because they require exceedingly low protein concentrations, allowing the proteins to be studied without a competing aggregation reaction. Two recent studies illustrate how these techniques may be applied. smFRET studies of the predominantly unstructured NM domain of the yeast prion protein Sup35 showed that it exists in a compact collapsed state in buffer, akin to the compact denatured states discussed in this manuscript, with nanosecond conformational fluctuations measured by FCS [62]. FCS measurements of the diffusion time of intrinsically disordered polyglutamine (polyQ) molecules found that they were, given the hydrophilic nature of glutamine, surprisingly collapsed [63]. PolyQ expansions in proteins are implicated in Huntington’s disease, and, as with other disease-associated natively unstructured proteins, a description of their structural characteristics may be the key to understanding their role in disease.

Lastly, two recent papers on very different model systems highlight how FCS and smFRET may eventually be applied to cellular characterization of unfolded proteins. In the first, Neuweiler et al. measured contact rates in unstructured polypeptides with FCS in the presence of crowding reagents to simulate in vivo conditions [64]. In the second study, Sharma et al. used smFRET to demonstrate that a target protein bound to GroEL populates a distribution of conformations, ranging from highly expanded to more collapsed [65]. This last study is particularly noteworthy in that it demonstrates the potential of the methods discussed in this paper in helping to understand the mechanisms of the cellular machinery involved in protein folding.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Yong Xiong for making the figure in Box 1 and Tobias Baumgart for careful reading of the manuscript. ER is supported by grants from the Ellison Medical Foundation and NIH GM08439. HC is supported by the STC Program of the National Science Foundation under Agreement No. ECS-9876771.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bilsel O, Matthews CR. Molecular dimensions and their distributions in early folding intermediates. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haas E. The study of protein folding and dynamics by determination of intramolecular distance distributions and their fluctuations using ensemble and single-molecule FRET measurements. ChemPhysChem. 2005;6:858–870. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200400617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kubelka J, Hofrichter J, Eaton WA. The protein folding 'speed limit'. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:76–88. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mittag T, Forman-Kay JD. Atomic-level characterization of disordered protein ensembles. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stryer L, Haugland RP. Energy Transfer - a Spectroscopic Ruler. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1967;58:719-&. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.2.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haran G. Single-molecule fluorescence spectroscopy of biomolecular folding. J Phys Condes Matter. 2003;15:R1291–R1317. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michalet X, Weiss S, Jager M. Single-molecule fluorescence studies of protein folding and conformational dynamics. Chem Rev. 2006;106:1785–1813. doi: 10.1021/cr0404343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schuler B, Eaton WA. Protein folding studied by single-molecule FRET. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magde D, Elson EL, Webb WW. Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy .2. Experimental Realization. Biopolymers. 1974;13:29–61. doi: 10.1002/bip.1974.360130103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magde D, Webb WW, Elson E. Thermodynamic Fluctuations in a Reacting System - Measurement by Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy. Phys Rev Lett. 1972;29:705-&. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haustein E, Schwille P. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy: Novel variations of an established technique. Annu Rev Biophys Biomolec Struct. 2007;36:151–169. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.36.040306.132612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hess ST, Huang SH, Heikal AA, Webb WW. Biological and chemical applications of fluorescence correlation spectroscopy: A review. Biochemistry. 2002;41:697–705. doi: 10.1021/bi0118512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chattopadhyay K, Saffarian S, Elson EL, Frieden C. Measurement of microsecond dynamic motion in the intestinal fatty acid binding protein by using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14171–14176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172524899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen HM, Rhoades E, Butler JS, Loh SN, Webb WW. Dynamics of equilibrium structural fluctuations of apomyoglobin measured by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10459–10464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704073104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherman E, Haran G. Coil-globule transition in the denatured state of a small protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11539–11543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601395103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohn JE, Millett IS, Jacob J, Zagrovic B, Dillon TM, Cingel N, Dothager RS, Seifert S, Thiyagarajan P, Sosnick TR, et al. Random-coil behavior and the dimensions of chemically unfolded proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12491–12496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403643101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsh JA, Neale C, Jack FE, Choy WY, Lee AY, Crowhurst KA, Forman-Kay JD. Improved structural characterizations of the drkN SH3 domain unfolded state suggest a compact ensemble with native-like and non-native structure. J Mol Biol. 2007;367:1494–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shortle D, Ackerman MS. Persistence of native-like topology in a denatured protein in 8 M urea. Science. 2001;293:487–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1060438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yi Q, Scalley-Kim ML, Alm EJ, Baker D. NMR characterization of residual structure in the denatured state of protein L. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:1341–1351. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blanco FJ, Serrano L, Forman-Kay JD. High populations of non-native structures in the denatured state are compatible with the formation of the native folded state. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:1153–1164. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernado P, Blanchard L, Timmins P, Marion D, Ruigrok RWH, Blackledge M. A structural model for unfolded proteins from residual dipolar couplings and small-angle x-ray scattering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17002–17007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506202102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fitzkee NC, Rose GD. Reassessing random-coil statistics in unfolded proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12497–12502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404236101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jha AK, Colubri A, Freed KF, Sosnick TR. Statistical coil model of the unfolded state: Resolving the reconciliation problem. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13099–13104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506078102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zagrovic B, Pande VS. Structural correspondence between the alpha-helix and the random-flight chain resolves how unfolded proteins can have native-like properties. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:955–961. doi: 10.1038/nsb995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deniz AA, Laurence TA, Beligere GS, Dahan M, Martin AB, Chemla DS, Dawson PE, Schultz PG, Weiss S. Single-molecule protein folding: Diffusion fluorescence resonance energy transfer studies of the denaturation of chymotrypsin inhibitor 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5179–5184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090104997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuzmenkina EV, Heyes CD, Nienhaus GU. Single-molecule FRET study of denaturant induced unfolding of RNase H. J Mol Biol. 2006;357:313–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merchant KA, Best RB, Louis JM, Gopich IV, Eaton WA. Characterizing the unfolded states of proteins using single-molecule FRET spectroscopy and molecular simulations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1528–1533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607097104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuler B, Lipman EA, Eaton WA. Probing the free-energy surface for protein folding with single-molecule fluorescence spectroscopy. Nature. 2002;419:743–747. doi: 10.1038/nature01060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tezuka-Kawakami T, Gell C, Brockwell DJ, Radford SE, Smith DA. Urea-induced unfolding of the immunity protein Im9 monitored by spFRET. Biophys J. 2006;91:L42–L44. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.088344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laurence TA, Kong XX, Jager M, Weiss S. Probing structural heterogeneities and fluctuations of nucleic acids and denatured proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17348–17353. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508584102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacob J, Krantz B, Dothager RS, Thiyagarajan P, Sosnick TR: Early collapse is not an obligate step in protein folding. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:369–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plaxco KW, Millett IS, Segel DJ, Doniach S, Baker D. Chain collapse can occur concomitantly with the rate-limiting step in protein folding. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:554–556. doi: 10.1038/9329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lipman EA, Schuler B, Bakajin O, Eaton WA. Single-molecule measurement of protein folding kinetics. Science. 2003;301:1233–1235. doi: 10.1126/science.1085399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCarney ER, Werner JH, Bernstein SL, Ruczinski I, Makarov DE, Goodwin PM, Plaxco KW. Site-specific dimensions across a highly denatured protein; a single molecule study. J Mol Biol. 2005;352:672–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang OW, FormanKay JD. NMR studies of unfolded states of an SH3 domain in aqueous solution and denaturing conditions. Biochemistry. 1997;36:3959–3970. doi: 10.1021/bi9627626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoffmann A, Kane A, Nettels D, Hertzog DE, Baumgarte P, Lengefeld J, Reichardt G, Horsley DA, Seckler R, Bakajin O, et al. Mapping protein collapse with single-molecule fluorescence and kinetic synchrotron radiation circular dichroism spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:105–110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604353104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chattopadhyay K, Elson EL, Frieden C. The kinetics of conformational fluctuations in an unfolded protein measured by fluorescence methods. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2385–2389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500127102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buscaglia M, Schuler B, Lapidus LJ, Eaton WA, Hofrichter J. Kinetics of intramolecular contact formation in a denatured protein. J Mol Biol. 2003;332:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00891-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hagen SJ, Hofrichter J, Eaton WA. Rate of intrachain diffusion of unfolded cytochrome c. J Phys Chem B. 1997;101:2352–2365. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krieger F, Fierz B, Bieri O, Drewello M, Kiefhaber T. Dynamics of unfolded polypeptide chains as model for the earliest steps in protein folding. J Mol Biol. 2003;332:265–274. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00892-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rischel C, Jorgensen LE, Foldes-Papp Z. Microsecond structural fluctuations in denatured cytochrome c and the mechanism of rapid chain contraction. J Phys Condes Matter. 2003;15:S1725–S1735. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eliezer D, Yao J, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Structural and dynamic characterization of partially folded states of apomyoglobin and implications for protein folding. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:148–155. doi: 10.1038/nsb0298-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lietzow MA, Jamin M, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Mapping long-range contacts in a highly unfolded protein. J Mol Biol. 2002;322:655–662. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00847-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gopich IV, Szabo A. Single-molecule FRET with diffusion and conformational dynamics. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:12925–12932. doi: 10.1021/jp075255e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nir E, Michalet X, Hamadani KM, Laurence TA, Neuhauser D, Kovchegov Y, Weiss S. Shot-noise limited single-molecule FRET histograms: Comparison between theory and experiments. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:22103–22124. doi: 10.1021/jp063483n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Talaga DS, Lau WL, Roder H, Tang JY, Jia YW, DeGrado WF, Hochstrasser RM. Dynamics and folding of single two-stranded coiled-coil peptides studied by fluorescent energy transfer confocal microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13021–13026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.24.13021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Best RB, Merchant KA, Gopich IV, Schuler B, Bax A, Eaton WA. Effect of flexibility and cis residues in single-molecule FRET studies of polyproline. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18964–18969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709567104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doose S, Neuweiler H, Barsch H, Sauer M. Probing polyproline structure and dynamics by photoinduced electron transfer provides evidence for deviations from a regular polyproline type II helix. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17400–17405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705605104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schuler B, Lipman EA, Steinbach PJ, Kumke M, Eaton WA. Polyproline and the "spectroscopic ruler" revisited with single-molecule fluorescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2754–2759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408164102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuzmenkina EV, Heyes CD, Nienhaus GU. Single-molecule Forster resonance energy transfer study of protein dynamics under denaturing conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15471–15476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507728102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boukobza E, Sonnenfeld A, Haran G. Immobilization in surface-tethered lipid vesicles as a new tool for single biomolecule spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:12165–12170. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rhoades E, Gussakovsky E, Haran G. Watching proteins fold one molecule at a time. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3197–3202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2628068100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Amirgoulova EV, Groll J, Heyes CD, Ameringer T, Rocker C, Moller M, Nienhaus GU. Biofunctionalized polymer surfaces exhibiting minimal interaction towards immobilized proteins. ChemPhysChem. 2004;5:552–555. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200400024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cohen AE, Moerner WE. Method for trapping and manipulating nanoscale objects in solution. Appl Phys Lett. 2005;86 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moerner WE. New directions in single-molecule imaging and analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12596–12602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610081104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bieri O, Wirz J, Hellrung B, Schutkowski M, Drewello M, Kiefhaber T. The speed limit for protein folding measured by triplet-triplet energy transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9597–9601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fierz B, Satzger H, Root C, Gilch P, Zinth W, Kiefhaber T. Loop formation in unfolded polypeptide chains on the picoseconds to microseconds time scale. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2163–2168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611087104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lapidus LJ, Eaton WA, Hofrichter J. Measuring the rate of intramolecular contact formation in polypeptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7220–7225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nettels D, Gopich IV, Hoffmann A, Schuler B. Ultrafast dynamics of protein collapse from single-molecule photon statistics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2655–2660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611093104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nettels D, Hoffmann A, Schuler B. Unfolded Protein and Peptide Dynamics Investigated with Single-Molecule FRET and Correlation Spectroscopy from Picoseconds to Seconds. 2008;112:6137–6146. doi: 10.1021/jp076971j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xie HB, Vucetic S, Iakoucheva LM, Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK, Obradovic Z, Uversky VN. Functional anthology of intrinsic disorder. 3. Ligands, post-translational modifications, and diseases associated with intrinsically disordered proteins. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:1917–1932. doi: 10.1021/pr060394e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mukhopadhyay S, Krishnan R, Lemke EA, Lindquist S, Deniz AA. A natively unfolded yeast prion monomer adopts an ensemble of collapsed and rapidly fluctuating structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2649–2654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611503104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Crick SL, Jayaraman M, Frieden C, Wetzel R, Pappu RV. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy shows that monomeric polyglutamine molecules form collapsed structures in aqueous solutions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16764–16769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608175103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Neuweiler H, Lollmann M, Doose S, Sauer M. Dynamics of unfolded polypeptide chains in crowded environment studied by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:856–869. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sharma S, Chakraborty K, Mueller BK, Astola N, Tang YC, Lamb DC, Hayer-Hartl M, Hartl FU. Monitoring protein conformation along the pathway of chaperonin-assisted folding. Cell. 2008;133:142–153. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Forster T. *Zwischenmolekulare Energiewanderung Und Fluoreszenz. Ann Phys -Berlin. 1948;2:55–75. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Neuweiler H, Sauer M. Using photoinduced charge transfer reactions to study conformational dynamics of biopolymers at the single-molecule level. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2004;5:285–298. doi: 10.2174/1389201043376896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhuang XW, Ha T, Kim HD, Centner T, Labeit S, Chu S. Fluorescence quenching: A tool for single-molecule protein-folding study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14241–14244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ha TJ, Ting AY, Liang J, Caldwell WB, Deniz AA, Chemla DS, Schultz PG, Weiss S. Single-molecule fluorescence spectroscopy of enzyme conformational dynamics and cleavage mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:893–898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ratner V, Sinev M, Haas E. Determination of intramolecular distance distribution during protein folding on the millisecond timescale. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:1363–1371. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Elson EL, Magde D. Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy .1. Conceptual Basis and Theory. Biopolymers. 1974;13:1–27. doi: 10.1002/bip.1974.360130103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kinoshita M, Kamagata K, Maeda A, Goto Y, Komatsuzaki T, Takahashi S. Development of a technique for the investigation of folding dynamics of single proteins for extended time periods. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10453–10458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700267104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Widengren J, Mets U, Rigler R. Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy of Triplet- States in Solution - a Theoretical and Experimental-Study. J Phys Chem. 1995;99:13368–13379. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chattopadhyay K, Saffarian S, Elson EL, Frieden C. Measuring unfolding of proteins in the presence of denaturant using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Biophys J. 2005;88:1413–1422. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.053199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sherman E, Itkin A, Kuttner YY, Rhoades E, Amir D, Haas E, Haran G. Using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy to study conformational changes in denatured proteins. accepted by Biophys J. 2008 doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.120220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]