The advanced trauma life support course teaches that if only the patient's carotid pulse is palpable, the systolic blood pressure is 60-70 mm Hg; if carotid and femoral pulses are palpable, the systolic blood pressure is 70-80 mm Hg; and if the radial pulse is also palpable, the systolic blood pressure is more than 80 mm Hg.1 The only study to examine the accuracy of this model used non-invasive blood pressure measurements, which have a tendency to underestimate systemic arterial blood pressure during hypotension.2 No reliable data are therefore available to support the advanced trauma life support guidelines on which clinical decisions are made. We assessed whether the guidelines accurately predict systolic blood pressure by palpation of radial, femoral, and carotid pulses in hypovolaemic patients in whom blood pressure was measured using invasive arterial monitoring.

Methods and results

After obtaining approval of the study by the ethics committee, we studied sequential patients with hypotension secondary to hypovolaemic shock and in whom invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring had been established. An observer blinded to the blood pressure palpated the radial, femoral, and carotid pulses, and the invasive systolic blood pressure was recorded.

The 20 sequential patients studied over the three year period were aged 18-79 years. Not all pulses were palpable when a reading was taken because a sterile operating field impaired access to the patients. The radial pulse always disappeared before the femoral pulse, which always disappeared before the carotid pulse. The data were split into four subgroups: radial, femoral, and carotid pulses present (group 1), femoral and carotid pulses only (group 2), carotid pulse only (group 3), and radial, femoral, and carotid pulses absent (group 4).

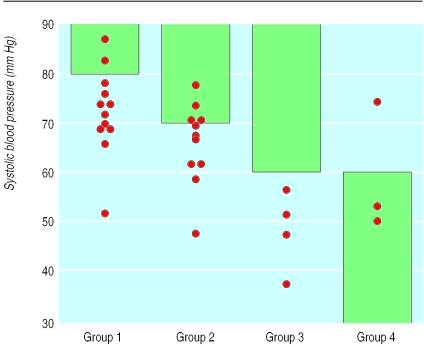

The figure shows the distribution of the systolic blood pressure in each of these groups. The reference lines in the figure at 80 mm Hg, 70 mm Hg, and 60 mm Hg represent the values that, according to the advanced trauma life support guidelines, the systolic blood pressure is expected to exceed for groups 1, 2, and 3 respectively.

In group 1, 10/12 (83%) subjects had a systolic blood pressure <80 mm Hg (mean 72.5 mm Hg (reference range 55.3-89.7 mm Hg)). In group 2, 10/12 (83%) subjects had a systolic blood pressure <70 mm Hg (mean 66.4 mm Hg (50.9-81.9 mm Hg)). In group 3, none of the four patients had a systolic blood pressure >60 mm Hg as predicted by the advanced trauma life support guidelines. And in group 4, 2/3 patients had a systolic blood pressure <60 mm Hg as predicted by the advanced trauma life support guidelines.

Comment

The advanced trauma life support guidelines for assessing systolic blood pressure are inaccurate and generally overestimate the patient's systolic blood pressure and therefore underestimate the degree of hypovolaemia. The minimum blood pressure predicted by the guidelines was exceeded in only four of 20 patients. The mean blood pressure and reference range obtained for each group indicate that the guidelines overestimate the systolic blood pressure associated with the number of pulses present. This study therefore does not support the teaching of the advanced trauma life support course on the relation between palpable pulses and systolic blood pressure.

Supplementary Material

Figure.

Dot plot showing the distribution of systolic blood pressure according to palpable pulses (group 1: radial, femoral, and carotid pulses present; group 2: femoral and carotid pulses only; group 3: carotid pulse only; group 4: radial, femoral, and carotid pulses absent); shaded areas indicate blood pressures expected according to advanced trauma life support guidelines

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

This article is part of the BMJ's randomised controlled trial of open peer review. Documentation relating to the editorial decision making process is available on the BMJ's website

References

- 1.Collicott PE. Advanced trauma life support course for physicians. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poulton TJ. ATLS paradigm fails. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:107. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(88)80538-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.