Abstract

Glycosphingolipids (GSLs) and gangliosides are a group of bioactive glycolipids that include cerebrosides, globosides, and gangliosides. These lipids play major roles in signal transduction, cell adhesion, modulating growth factor/hormone receptor, antigen recognition, and protein trafficking. Specific genetic defects in lysosomal hydrolases disrupt normal GSL and ganglioside metabolism leading to their excess accumulation in cellular compartments, particularly in the lysosome, i.e., lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs). The storage diseases of GSLs and gangliosides affect all organ systems, but the central nervous system (CNS) is primarily involved in many. Current treatments can attenuate the visceral disease, but the management of CNS involvement remains an unmet medical need. Early interventions that alter the CNS disease have shown promise in delaying neurologic involvement in several CNS LSDs. Consequently, effective treatment for such devastating inherited diseases requires an understanding of the early developmental and pathological mechanisms of GSL and ganglioside flux (synthesis and degradation) that underlie the CNS diseases. These are the focus of this review.

Keywords: lysosomal storage diseases, pathological mechanism, brain development, neuronal degeneration

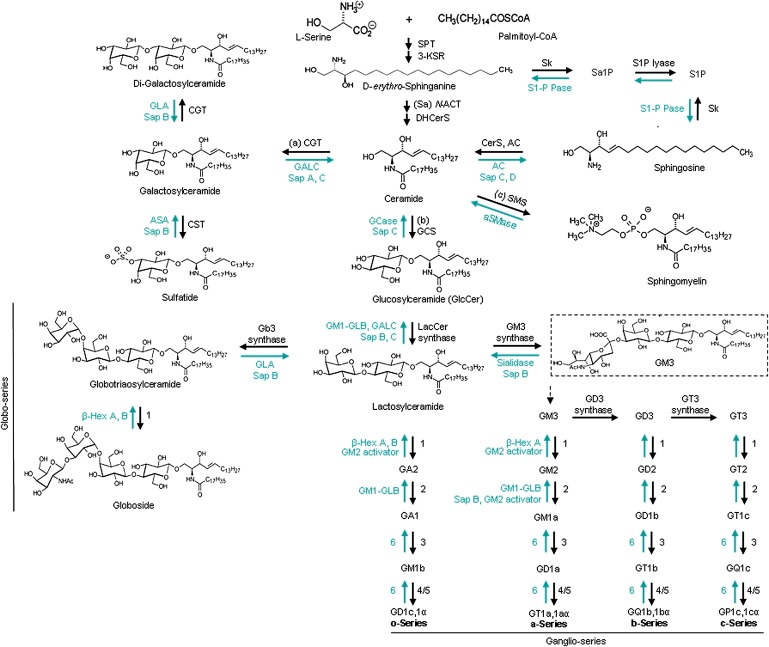

Glycosphingolipids (GSLs) consist of ceramide and one or more attached carbohydrates. The nature of the oligosaccharide head groups categorizes the GSLs into neutral or acidic types due to the absence or presence of sialic acid residues, respectively (Fig. 1). Gangliosides are sialic acid containing GSLs. In eukaryotic cells, GSLs and gangliosides compose 10–20% of the total lipids (1), which are important to a variety of cellular functions. GSLs and gangliosides are synthesized at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and are remodeled during transit from cis to trans Golgi by a series of glycosyl- and sialyl-transferases. These are then transported to the intracellular compartments and the plasma membrane where they become enriched in microdomains and membrane bilayers. During plasma membrane turnover, GSLs and gangliosides can be internalized and partially or completely degraded in the endosomal/lysosomal system to sphingosine and free fatty acids that are then transported or flipped across late endosomal and lysosomal membranes for recycling or for use as signaling molecules (2, 3).

Fig. 1.

Schematic view of the GSL metabolism pathways. The synthesis of GSLs and gangliosides progress stepwise and are catalyzed by membranous glycosyltransferases in the ER or Golgi apparatus (see text). The degradation reactions are also sequential and occur within the lysosomes by various hydrolases. The black arrows show the synthesis pathway in the ER and Golgi and the green arrows show the degradation pathway in the lysosome. The enzymes in o-, a-, b-, and c-ganglioside series are numbered: 1. GM2/GD2/GA2/GT2-synthase (β-1,4-N-acetyl-galactosaminyltransferase, GalNacT), 2. GA1/GM1a/GD1b/GT1c-synthase (UDP-Gal:βGalNAc β-1,3-galactosyltransferase), 3. sialyltransferase IV, 4. sialyltransferase V, 5. sialyltransferase VII, 6. sialidase. Abbreviations: 3-KSR (3-ketosphinganine reductase), Sk (sphingosine kinase), Sa1P (sphinganine 1-phosphate), S1P (sphingosine 1-phosphate), S1-P Pase (sphingosine 1-phosphate phosphatase), (Sa) N-ACT (sphinganine N-acyltransferase), DHCerS (dihydroceramide desaturase), CerS (ceramide synthase, also called longevity assurance genes), SMS (sphingomyelin synthase), GT3 synthase (α-N-acetyl-neuraminide α-2,8- sialyltransferase). The chemical structures are adapted from (3, 36, 100, 313–315) and http://www.cybercolloids.net/library/sugars/hexoses.php. Nomenclature of the enzymes and protein are from IUBMB (http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/iubmb/enzyme) (37, 43, 315).

GSL metabolic pathways

GSL biosynthesis begins with condensation of serine and palmitoyl-CoA catalyzed by serine-palmitoyltransferase (SPT) on the cytoplasmic face of the ER, leading to de novo biosynthesis of ceramide, the core of GSLs (Fig. 1) (3–5). Ceramide consists of a fatty acid acyl chain that varies in length and saturation, and a sphingoid base that differs in the number and position of double bonds and hydroxyl groups (6–8). The fatty acid chain length of ceramide is controlled by tissue- and cell-specific ceramide synthases (also called longevity assurance genes) (9). In addition, ceramide can be generated by acid sphingomyelinase (aSMase) hydrolysis of sphingomyelin in the lysosome or at the plasma membrane and by activities of secreted aSMase at the plasma membrane or associated with lipoproteins (Figs. 1 and 2) (10). Neutral sphingomyelinase (nSMase) also cleaves plasma membrane sphingomyelin to ceramide (11). In the salvage pathway, lysosomally derived sphingosine can be reacylated (Fig. 2) (12). Once formed, ceramide is sorted to three pathways: 1) GalCer synthesis in the ER that is followed by 3-sulfo-GalCer (sulfatide) synthesis in the Golgi (13, 14); 2) GlcCer synthesis on the cytoplasmic face of the Golgi as the precursor of most GSLs; and 3) ceramide transfer protein (CERT) delivery to the mid-Golgi for sphingomyelin synthesis (15, 16). In the trans Golgi lumen, the transfer of a β-galactose onto GlcCer by lactosylceramide (LacCer) synthase forms LacCer (17). Several galactosyl-, N-acetylgalactosaminyl-, N-acetylglucosaminyl-, and sialyltransferases can elongate the oligosaccharide chain of GSLs along the luminal side of Golgi (18, 19), thereby defining the different series of GSLs. Addition of sialic acid to LacCer forms GM3 ganglioside by LacCer α-2,3-sialyltransferase (GM3 synthase) that initiates synthesis of the ganglioside or sialo-GSL series (Fig. 1). The type of sugars in the oligosaccharide backbone depends on the activity of glycosyltransferases in the Golgi, the cell type, and the developmental or disease stage (19–22) (see below).

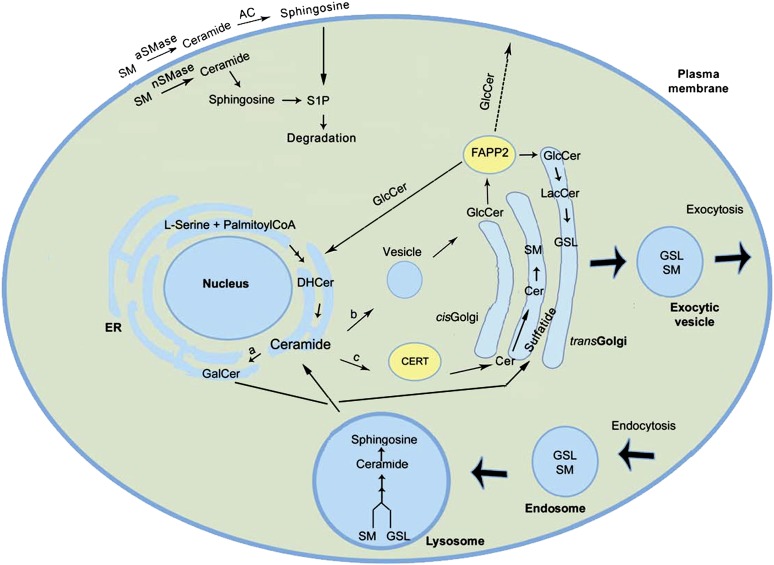

Fig. 2.

Intracellular topology of GSL biosynthesis and trafficking. Ceramide, formed by condensation of serine and palmitoyl-CoA on the cytoplasmic face of ER, has one of three fates (16): a) conversion to galactosylceramide (GalCer) in the ER lumen, which is subsequently converted to sulfatide in the mid-Golgi (13, 14), b) vesicular transport to the cytoplasmic face of the cis-Golgi where it is a precursor for GlcCer synthesis (26, 316), and c) transport by ceramide transfer protein (CERT) to the mid-Golgi where sphingomyelin is formed within the lumen (319). Once formed, GlcCer also has several fates (27, 317): 1) transport by FAPP2 to the ER and/or to the trans-Golgi lumen where it is converted to lactosylceramide (LacCer) (17, 26, 27), 2) to the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane by unknown mechanisms, and 3) to the extracellular matrix by exocytosis. Addition of sialic acid to LacCer initiates synthesis of gangliosides or the sialo-GSL series (318). Ceramide can also be generated through degradation of sphingomyelin in the lysosome or at the plasma membrane by aSMase and nSMase (10). Newly synthesized GSLs can exit the cell by exocytic vesicles while membrane and extracellular GSLs can be transported intracellularly via endocytosis with subsequent degradation sphingosine and free fatty acids by hydrolases in the lysosome (2, 10). Abbreviations: DHCer (dihydroceramide), S1P (sphingosine 1-phosphate), SM (sphingomyelin).

In addition to CERT, several other proteins participate in GSL trafficking in the cells. GlcCer can be flipped into the Golgi lumen or across plasma membrane by the ATP-binding cassette transporter [also called multidrug resistance protein, MDR1, or P-glycoprotein (Pgp)]. Although this has been shown for short-chain GlcCer or neutral GlcCer, transport of naturally occurring GlcCer by Pgp has not been shown in vivo (23–25). Four-phosphate adaptor protein 2 (FAPP2) can transport newly synthesized GlcCer to the trans Golgi and back to the ER (26). It is not clear how FAPP2 transports GlcCer through the cytosol to the plasma membrane (26, 27). Although glycolipid transfer protein has been shown to have binding affinity for GSLs, transport of GSLs by glycolipid transfer protein has not been reported (28). The mechanisms of intracellular transport of GSLs continue to emerge.

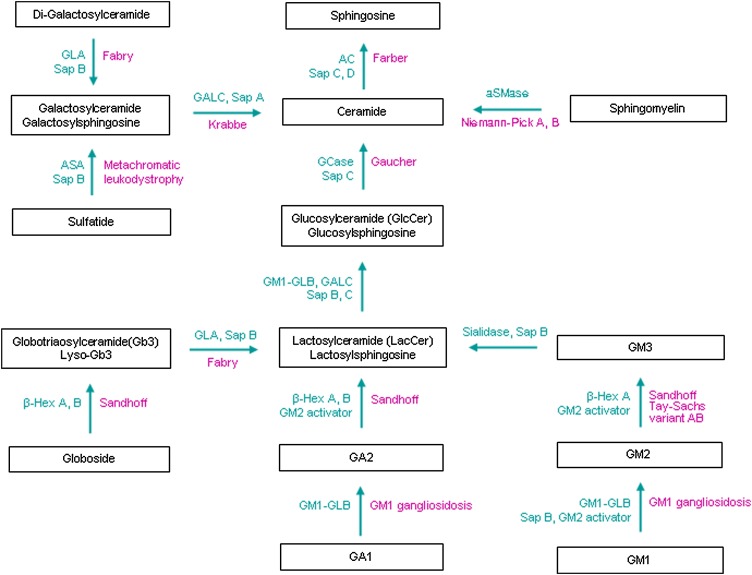

The catabolism of complex GSLs also proceeds by stepwise, sequential removal of sugars by lysosomal exohydrolases to the final common products, sphingosine and fatty acids (Fig. 1). Individual defects in GSL hydrolases (Fig. 3) result in excessive accumulation of specific GSLs in lysosomes leading to the various lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs) (see Table 1). Nonenzymatic proteins are essential to GSL degradation either by presenting lipid substrates to their cognate enzymes or by interacting with their specific enzyme (2). Two genes, PSAP (prosaposin) and GM2A (GM2 activator protein), encode five such proteins (Fig. 3) (2, 29). Four saposins (A, B, C, and D) or sphingolipid activator proteins (Sap) are derived from proteolytic cleavage of a single precursor protein, prosaposin, in the late endosome and lysosome (30, 31). Each of these saposins has specificity for a particular GSL hydrolase (Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Disorders of GSL and ganglioside degradation. Inherited diseases (violet) caused by genetic defects of individual hydrolases/proteins (green) in the GSL and ganglioside degradation pathway. Increased levels of lysosphingolipids occur in the GSL LSDs, e.g., glucosylsphingosine in Gaucher disease, Lyso-Gb3 in Fabry disease, and galactosylsphingosine in Krabbe disease. Variant AB is GM2 activator deficiency disease. Tay-Sach disease, Sandhoff disease, and Variant AB are GM2 gangliosidosis. Abbreviations are listed in Fig. 1 legend.

TABLE 1.

Human and mouse disorders of GSL and ganglioside degradation

| Disease (Frequencies) | Gene Symbol, Chr. Location,a Name(s) | Species | Gene Defectb | Major Storage Materials | Phenotype | Onset | Lifespan | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farber disease (lipo granulomatosis) (rare) | ASAH1 Chr 8: p22-p21.3 AC, N-acylsphingosine amidohydrolase 1; N-acylsphingosine deacylase, AC, ASAH1 | Human | >17 Different mutations including point mutations and splice-site mutations | Ceramide, hydroxyl ceramide | Granulomas, lipid-laden macrophages in the CNS and viscera, mild or no neurological involvement, subcutaneous skin nodules near or over joints | 0 days – 1.7 year | 3 days–16 year | (96, 108, 321–323) |

| Asah1 Chr 8: 42425551-42460127(-) Asah1−/− | Mouse | Three copies of targeting constructs (PGK-neo cassette replacing exons 3 through 5) inserted into intron 12 | Ceramide | Embryonic lethal | 2-cell stage (E0–E1) | <E8.5 | (39, 102) | |

| Asah1 Chr 8: 42425551-42460127(-) Asah1+/- | Mouse | Three copies of targeting constructs (PGK-neo cassette replacing exons 3 through 5) inserted into intron 12 | Ceramide | Normal, progressive lipid-laden inclusions in liver Kupffer cells. | 6 months | Normal lifespan | (102) | |

| NPA (0.5 to 1/100,000) | SMPD1 Chr 11: p15.4- p15.1 aSMase, sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 1, aSMase, ASM, aSMase, Zn-SMase | Human | >100 mutations Single nucleotide deletions, missense mutations | Sphingomyelin, Cholesterol, Bis (monoaclglycero)phosphate, GlcCer, LacCer Gb3, GM2, GM3 | Neurovisceral disease, hepatosplenomegaly, failure to thrive, rapid neurodegeneration, foamy cells in multiple organs | 3–6 months | 2–3 years | (104, 109, 324, 325) |

| NPB (0.5 to 1/100,000) | Same as NPA | Human | A single mutation, a 3-base deletion (ΔR608) | Sphingomyelin, Cholesterol, Bis(monoaclglyc ero)phosphate, GlcCer, LacCer, Gb3, GM2, GM3 | Visceral disease, minor neurological involvement, mental retardation, foamy cells in multiple organs | Early childhood to adulthod | Adolescence to adulthood | (104, 109, 325) |

| NPA/B | Smpd1 Chr 7: 112702939-112706901(+) ASM−/− | Mouse | Insertion of a neomycin resistance cassette into exon 3 | Sphingomyelin | Hepatosplenomegaly, tremors, ataxia, impaired coordination, lethargic, poor feeding, hunched posture, progressive CNS disease, Purkinje cell loss Dysregulated Ca2+ homeostasis | 2–3 months | 4 months | (106, 109) |

| Asm Asm−/− | Mouse | Insertion of a neomycin resistance cassette into exon 2 | Sphingomyelin, Cholesterol | Hepatosplenomegaly, mild tremors, ataxia, lethargic, poor feeding, hunched posture, progressive CNS disease, Purkinje cell loss, atrophy of brain, fertile | 2 months | 6–8 months | (105) | |

| NPC (1/120,000 to 1/150,000) | NPC1 (95% cases) Chr18:q11-q12 NPC1 | Human | Infantile and "classic" (severe) phenotype: Premature stop codon mutations,missense mutations in the sterol-sensing domain (SSD), A1054T in the cysteine-rich luminal loop "Variant" (mild) phenotype: Missense mutations (I943M, V950M, G986S, G992R, P1007A) clustered within the cysteine-rich luminal loop between transmembrane domains 8 and 9 | Cholesterol, Sphingomyelin, GlcCer, LacCer and GM2 | Progressive Purkinje cell loss, ataxia, dystonia, dementia, variable hepa tosplenomegaly, sea blue histiocytes in bone marrow, liver, spleen, and lung | In utero to adult | <6 months to adult | (312, 326–330) |

| Npc1 Chr 18: 12348202-12394909(-)spm NPC1−/− | Mouse | Spontaneous mutation | Cholesterol, GlcCer, LacCer and GM2 | Progressive Purkinje cell loss, demyelination, tremors, hind limb paralysis, poor fee ding, foamy macrophages in viscera, hepatosplenomegaly, enlarge lymph nodes, infertile | 7 weeks | 12–14 weeks | (260, 326, 331) | |

| Npc1 Chr 18: 12348202- 12394909(-)nih NPC1−/− | Mouse | Spontaneous mutation, transposon insertion deleting 11/13 transmembrane domains | Cholesterol, Sphingomyelin, lyso(bis)phosphatidic acid, GlcCer, LacCer, GA2, GM2 and GM3 | Progressive Purkinje cell loss, demyelination, tremors, hind limb paralysis, poor feeding, foamy macrophages in viscera | 5–7 weeks | 11–14 weeks | (218, 260, 326, 332–334) | |

| NPC2/HE1 (5% cases) Chr 14: q24.3 HE1, NP-C2, NPC2, HE1/NPC2 | Human | Severe disease: 27delG leading to early termination of protein, a missense mutation (S67P),E20X, E118X, S67P, and E20X/27delG mutations Milder disease: splice mutation (VS2+5G→A) in the consensus sequence of the 5′ donor site of intron 2 | Cholesterol, Sphingomyelin, GlcCer, LacCer and GM2 | Same as NPC1 | In utero to adult | <6 mos to adult | (326–330) | |

| Npc2 Chr 12: 86097442-86113848(-) | Mouse | Insertion of neo cassette into intron 3 | Cholesterol, Sphingomyelin, lyso(bis)phosphatidic acid, GlcCer, LacCer, GA2, GM2 and GM3 | Weight loss, tremors, ataxia, generalized locomotor dysfunction | 7.9 weeks | 13–18.5 weeks | (200) | |

| Krabbe disease (1/100,000) | GALC Chr 14: q31 Galactocereborside β-galactosidase Galactosylceramide β-galactosidase | Human | >60 mutationsInfantile patients:502C→T polymorphism associated with a 30 kb deletion in intron 10Late onset patients: missense mutations (R63H, G95S, M101L, G268S, G270D, Y298C, and I234T), nonsense mutation (S7X), a one-base deletion (805delG), mutations interfere with the splicing of intron 1and intron 6 | GalCer, Galactosylsphingosine | Progressive CNS and PNS involvement, hypertonicity/ hyperactive reflexes, progressive flaccidity, peripheral neuropathy, severe developmental delay, blindness, spastic paraparesis, dementia and loss of vision in later onset patients, infiltration of characteristic "globoid cells" | 3–6 months or 10– 40 years | < 2 years or adult | (111, 113, 335, 336, 337, 338) |

| Galc Chr 12: 99440510-99497547(-) twitcher | Mouse | Spontaneous mutation; G to A transition at codon 339 | GalCer, Galactosylsphingosine | Generalized tremors, progressive weakness, wasting, dys/demyelination, abnormal multinucleated "globoid" cells infiltration, gray matter unaffected | 3 weeks | 6.5–12 weeks | (116, 209, 210, 339, 340) | |

| Galc Chr 12: 99440510-99497547(-) Transgenic Krabbe | Mouse | Insertion of human mutation (H168C) in exon 5 | GalCer, Galactosylsphingosine | Tremor, hindleg weakness, microphage infiltration in PNS | 25–30 days | 58 days | (120) | |

| MLD (1/40,000) | ARSA Chr 22: q13.31- qter Arylsulphatase A cerebroside-3-sulfate 3-sulfohydrolase, ASA | Human | >40 mutations Deletions, insertions, splice site mutation, and missense mutations | Sulfatide | Difficulty walking after the first year of life, progressive peripheral neuropathies, muscle wasting/weakness, developmental delay, seizures, dementia | 6 months –16+ years | 5–63+ years | (122, 123, 341, 342) |

| Asa Chr 15: 89302959-89306545(-) Asa−/− | Mouse | A neomycin selection cassette inserted into exon 4 | Sulfatide | Mild phenotype compared with humans, normal lifespan, no widespread demyelination | 1 year | Normal lifespan | (129) | |

| Asa + Gal3st1 | Mouse | ASA−/− mice overexpressing sulfatide synthesizing enzyme CST | Sulfatide | More severe phenotype of ASA deficiency alone, more aggressive CNS and PNS demyelination | 1 year | < 2 years | (130) | |

| Fabry disease (1/40,000 to 1/117,000) | GLA Chr X: q22-q21 α-Galactosidase A | Human | >400 mutations in the GLA gene, including missense (76.4%), nonsense (16.4%), frameshift (3.6%), and splice site defects (3.6%) | Gb3, lyso-Gb3 | Males more severely affected, painful acroparesthesias, angiokeratoma, renal disease, cardiomyopathy, stroke, no clear neuronal involvement, ∼50% of heterozygous females affected | Childhood to 30+ years | 20–75.4 years | (137, 295, 343–348) |

| Gla Chr X: 131122688- 131135664(-) Gla−/− | Mouse | A neomycin resistance cassette inserted into fragment containing part of exon 3 and intron 3 | Gb3 | Normal lipid accumulation in kidneys, endothelium, liver, and peripheral nerve | Normal lifespan | (137, 138, 349) | ||

| Gaucher disease Type 1 - nonneuronopathic (1/800 in Ashkenazi Jewish, 1/100,000 in non-Jewish) | GBA1 Chr 1: q21 Acid β-glucosidase, β-glucosidase, glucosylceramide-β-glucosidase, glucosylceramidase, glucocerebrosidase, GCase | Human | Mutation substitution of amino acid asparagine for serine (N370S), N370S/84GG, N370S/L444P associated with Gaucher disease type 1 > 350 mutations associated with all Gaucher disease variants | GlcCer, GM1, GM2, GM3, GD3, Glucosylsphingosine | No neuronal involvement, chronic bone marrow expansion, bony deterioration, hepatosplenomegaly, hyper splenism, hepatic dysfunction, extensive fibrosis and tissue scarring, associated with Parkinson disease | 4–25 years | 6–80+ years | (95, 141, 226) |

| Gba1 Chr 3: 89006850-89012603(+) | Mouse | Human disease point mutations (N370S, D409V, D409H, and V394L) at gba1 locus in exon 9 | GlcCer | Mild phenotype with occasional storage cells in lung, spleen and liver, lipid accumulation in viscera, not in brain | <24 h or 3–7 months | Neonatal lethal (N370S), or normal lifespan (V394L, D409V, D409H) | (350) | |

| Mouse | Conditional gba knockout in hematopoietic and endothelial cells | GlcCer | Modest storage cells in liver and spleen, progressive splenomegaly, no bone marrow involvement | 16 weeks | Normal lifespan | (351) | ||

| Mouse | Conditional gba knockout in hematopoeitic endothelial cells | GlcCer | Splenomegaly and microcytic anemia | 12 months post induction | Normal lifespan | (352) | ||

| Gaucher disease type 2 - neuronopathic (1/500,000) | GBA1 Chr 1: q21 Acid β-glucosidase, β-glucosidase, glucosylceramide-β-glucosidase, glucosylceramidase, glucocerebrosidase, GCase | Human | A mutation causing leucine to proline change (L444P) associated with the neuronopathic forms of Gaucher disease, numerous other mutations | GlcCer, GM1, GM2, GM3, GD3, Glucosylsphingosine | Progressive CNS and lung involvement, neuronal death/drop-out, visceral involvement as type 1 disease | 3 months | <2 years | (95, 141) |

| Gba1 Chr 3: 89006850-89012603(+) Gba−/− | Mouse | A neomycin resistance cassette was inserted into exons 9 and 10 | GlcCer, Glucosylsphingosine | Mice die <24 h, lipid storage in lung, brain, a nd liver, glucosylsphingosine in brain and viscera | Embryonic lethal | (148) | ||

| Mouse | Conditional knockout (skin rescue), a floxed neo cassette was inserted into intron 8 | GlcCer | Rapid motor dysfunction, severe neurodegener ation, apoptotic cell death in brain, seizures | 7 days | 14 days | (149) | ||

| Mouse | Conditional knockout (skin rescue), reactivation of a low activity allele in keratinocytes | GlcCer | GlcCer accumulation brain, spleen, and liver, infiltration of Gaucher cells in sple en and liver. Rapid motor dysfunction, severe neurodegeneration, and cell death in CNS | 10 days | 14 days | (150) | ||

| Gaucher disease type 3 -neuronopathic (1/100,000) | GBA Chr 1: q21 Acid β-glucosidase, glucosylceramide-β-glucosidase, glucosylceramidase, glucocerebrosidase, GCase | Human | Homozygosity for L444P and D409H, numerous other mutations | GlcCer | Slower progression than Type 2 disease, normal intelligence, short stature with splenomegaly, abnormal eye movements, variable seizures | 1–5 years | 20–40 years | (95, 141, 353) |

| Complete Prosaposin/Sap deficiency (rare) | PSAP Chr 10: q21 Prosaposin, Sap precursor, PS, SAP1 | Human | 1 bp deletion (c.803delG) within the SAP-B domain of the prosaposin gene leads to a frameshift and premature stop codon, A to T transversion in the initiation codon | GlcCer, LacCer, Gb3, Ceramide, Sulfatides, Globotetraosylceramide | Rapid neurological disease, neuronal storage, loss of cortical neurons, astrocytosis, demyelination | 3 weeks | 16 weeks to 2 years | (176–178, 181) |

| Psap Chr 10: 59740375-59765342(+) PS−/− | Mouse | Exon 3 disrupted by insertion of a neomycin selection cassette | GlcCer, LacCer, Gb3, Ceramide, Sulfatides, Globotetraosylceramide | Rapidly neurological disease, hypomyelination, infl ammation, multiple GSLs accumulation in various organs | 20 days | Neonatal lethality or 5–7 weeks | (190) | |

| Psap Chr 10: 59740375-59765342(+) PS-NA | Mouse | Expression of transgenic prosaposin in PS−/− | GlcCer, LacCer, Ceramide, Sulfatides, | Ataxia, waddle gait, hypomyelination, inflammation, multi ple GSLs accumulation in various organs, Purkinje cell loss | 10–12 weeks | 7 months | (192) | |

| SapA deficiency late onset Krabbe disease(rare) | PSAP Saposin A, Sap A | Human | A 3 bp deletion in the SapA coding sequence of the prosaposin gene causing deletion of a conserved valine at amino acid number 11 of the SapA protein | GalCer, Galac tosylsphingosine | Normal development, rapid neurologic deterioration, loss of acquired milestones, vegetative state, eye contact and spontaneous movement at end stage | 3.5 months | 8 months | (187) |

| Psap Sap A−/− | Mouse | Amino acid substitution in the SapA domain on exon 4, Cys → Phe | GalCer, Galac tosylsphingosine | Hind limb paralysis, tremors, shaking at end stage, pathology and biochemistry identical but milder than twitcher mice | 2.5 months | 5 months | (191) | |

| SapB deficiency - variant MLD (rare) | PSAP Sap B | Human | Mutations destroy glycosylation sites, in-frame deletion of the first 21 bases of exon 6 | Sulfatide, Gangliosides, LacCer, Gb3, Digalactosylceramide | Variant form of MLD, normal ASA activity in white blood cells, increased lipid in urine | 1–10 years | 5–22 years | (124) |

| Psap Sap B−/− | Mouse | Amino acid substitution was introduced into the cysteine in SapB domain on exon 7, Cys →Phe | Hydroxy and nonhydroxy fatty acid sulfatide, LacCer, Gb3 | Neuromotor deterioration, minor head tremor, closely resembles MLD mice, no demyelination unlike human disease | 15 months | <2 years | (194) | |

| SapC deficiency (rare) | PSAP Sap C | Human | Neuronopathic: mutations on SapC domain (p.C382G, p.C382F, p.C315S) and premature stop codon in the SapD domain (p.Q430X), each on separate allele Non-neuronopathic: missense mutation on the SapC domain and the initiation codon mutation (p.L349P/ p.M1L) | GlcCer | Hepatosplenomegaly and severe mental deterioration, no Gaucher cells in bone marrow, slight retardation, focal seizures then generalized, ataxia, tremors opthalmoplegia, dysarthia, spastic tetraparesis, normal GCase activity | 1–8 years | 14–15.5 years | (124, 188, 189, 354–356) |

| Psap Sap C−/− | Mouse | Amino acid substitution on the SapC domain in exon 11, Cys → Pro | GlcCer, LacCer, LacSph | Progressive ataxia, Purkinje cell loss, cerebellum atrophy, impaired hippocampal LTP, slower disease progression than human, reduced GCase activity | 1 year | <2 years | (193) | |

| Psap Sap D−/− | Mouse | Amino acid substitution on the SapD domain in exon 13, Cys → Ser | Ceramide and hydroxyl ceramide | Renal degeneration, progressive polyuria, progressive, selective loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells | 6 months | 15 months | (98) | |

| Psap Sap CD−/− | Mouse | Amino acid substitutions were introduced into cysteine on SapC, (Cys → Pro) and D domains (Cys → Ser) | GlcCer and α-hydroxy ceramides | Severe neurological phenotype with ataxia, kyphotic posturing, hind limb paralysis, lipid accumulation in brain and kidney | 4 weeks | 8 weeks | (266) | |

| β-glucosidase (Gba) + prosaposin/ Sap deficiency | Gba + Psap V394L/PS-NA D409H/PS-NA | Mouse | Gba point mutants (V394L or D409H) crossed with mice expressing a low level Psap transgene (NA) | GlcCer, LacCer, Gb3 | Engorged macrophages infiltration in liver, lung, spleen, thymus, Purkinje cell loss, ataxia | 12 weeks | 22 weeks | (357) |

| Gba +Psap V394L/Sap C | Mouse | Gba point mutant crossed with SapC- deficiency mice | GlcCer, glucosylsphingosine | Hind limb paresis, axonal degeneration in CNS, hippocampal LTP attenuated | 30 days | 48 days | (205) | |

| GM1 gangliosidosis (1/100,000 to 1/300,000) | GLB1 Chr 3: p2.33 GM1- β-Galactosidase acid- β-galactosidase | Human | 78 missense/ nonsense mutations, 10 splicing mutations, 7 insertions, and 7 deletions Missense/nonsense mutations are primarily located in exon 2, 6, and 15 | GM1, GA1, GM2, GM3, GD1A, lyso-GM1, GlcCer, LacCer, oligosaccharides, keratan sulfate | Hepatosplenomegaly, localized skeletal involvement, CNS deterioration, seizures, mental regression, dystonia, gait disturbances, dysarthria | Birth to 3 years | 1–30 years | (155, 358, 359) |

| Glb1 Chr 9: 114310237-114383495(+) GM1 gangliosidosis mouse | Mouse | A neomycin resistance gene was inserted into exon 6 | GM1, GA1, GM2, GM3, GD1A, lyso-GM1, GlcCer, LacCer, oligosaccharides, keratan sulfate | Progressive spastic diplegia, clinical, pathological, biochemical manifestations similar to human | 4 months | 7–10 months | (156, 360) | |

| GM2 gangliosidosis Tay-Sachs (variant B) (1/4000 in Jewish 1/320,000 in non-Jewish) | HEX A Chr 15: q23-q24 β-hexosaminidase A (αβ) β-hexosaminidase S (αα) Hexosaminidase A | Human | Single nucleotide changes, deletions or insertions of varying size | GM2, GD1aGalNac, GA2, lyso-GM2 | CNS disease, rapid mental and motor deterioration, variable early dementia in adults | 3 months to adult | 2–40 years | (161, 162) |

| Hex A Chr 9: 59387504-59412914(+) Tay-Sachs mouse | Mouse | A neomycin resistance cassette was inserted into and disrupted exon 8 of the gene | GM2, GD1aGalNac, GA2, lyso-GM2 | Mouse normal, rare storage neurons in posterior horn of spinal cord, no obvious storage cells in viscera | Normal | (361, 362) | ||

| GM2 gangliosidosis Sandhoff disease (variant 0) (1/1000,000 in Jewish 1/390,000 in non- Jewish) | HEX B Chr 5: q13 β-hexosaminidases A (αβ) and B (ββ) Hexosaminidase A/B, HexA/HexB | Human | The most common mutation is a deletion of 16 kb including the HEXB promoter, exons 1–5, and part of intron 5 | GM2, GD1aGalNac, globoside, oligosaccharides, lyso-GM2 | Neurologic symptoms begin within first year, facial dysmorphism, skeletal dysplasia, hepatosplenomegaly | 5–6 months | 1.5–5.5 years | (161, 172, 363) |

| Hexb Chr 13: 97946362-97968225(-) Sandhoff mouse | Mouse | A neomycin resistance cassette was inserted into and disrupted exon 13 of the gene | GM2, GD1aGalNac, globoside, oligosaccharides, lyso-GM2 (PND2) | Motor function deterioration, head tremor, ataxia, bradykinesia, impaired balance, hind limb paralysis | 3 months | 5 months | (169) | |

| GM2 gangliosidosis GM2 Activator deficiency (Tay Sachs variant AB), (rare) | GM2A Chr 5: q31. 3-q33.1GM2 Activator GM2 ganglioside activator protein | Human | Single nonsense mutation in exon 2 | GM2, GA2 (minor) | Infantile acute encephalopathic phenot ype, closely resembles Tay-Sachs disease | 1 month | 5 months–5 years | (165, 172, 364) |

| Gm2a Chr 11: 54911617-54924400(+) Gm2a−/− | Mouse | A neomycin resistance cassette replaced exon 3 and exon 4 | GM2, GA2(minor) | Mouse normal, minor storage in cerebellum unlike Tay-Sachs disease mice | Normal | (175) |

Mouse Genome Database at the Mouse Genome Informatics Web site, The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME. World Wide Web (URL: http://www.informatics.jax.org), January, 2010.

Detailed mutation information for each disease can be found in the references.

The interconnection of synthesis and degradation pathway network

Many enzymes in GSL metabolic pathways are regulated in response to extra- and intracellular stimuli leading to modulation of bioactive lipid levels (32). The synthesis/degradation pathways (Fig. 1) of GSL metabolism form a network with the product of one enzyme serving as a substrate for other enzymes; e.g., ceramide formed from sphingomyelin may act directly or serve as a substrate for ceramidase, for sphingomyelin synthase, or for GCS, thereby being "converted" to sphingosine, sphingomyelin, and a by product, diacylglycerol, or GlcCer, respectively (33). Also, many cell stimuli modulate the function of more than one of these enzymes in a cell- or tissue-specific manner; upregulation of GCS by tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and interleukin (IL)-1 has been reported in the liver (34). The inhibition of GCS and sphingomyelin synthase activities by TNFα was found in the rhabdomyosarcoma cells (35). Thus, the coordinate regulation of such enzymes in response to cellular stimuli alters the lipid flux through this network (Fig. 1) (32). In addition, cellular compartmentalization topologically restricts enzymes and their products to subcellular organelles in which metabolic fluxes are modulated by enzymatic and GSL endocytotic/exocytotic balances (36, 37). Also, disruption of ER- and Golgi-associated endocytotic/exocytotic systems by unrelated pathways (e.g., mucopolysaccharide degradation) may increase levels of a particular GSL and cause secondary accumulations of other GSLs and gangliosides (38). These secondary storage compounds contribute directly to disease pathogenesis and to complex metabolic events leading to multiple, apparently unrelated substrate storage diseases (See Pathological consequences of disorders in GSL metabolism).

Roles of GSLs during normal development and adult stage

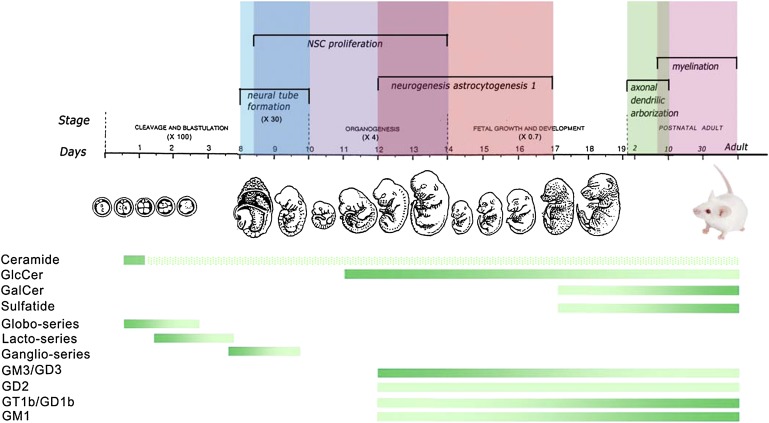

Changes in brain GSL synthesis and metabolism correlate with the stage-specific brain development and function, indicating a coordinated spatial-temporal regulation (Fig. 4). Elucidating the timing of GSL synthesis and the alterations of GSL fluxes in the disease states is essential to understanding the pathogenesis and propagation of the various GSL LSDs.

Fig. 4.

GSLs and gangliosides in developmental stages of the nervous system. The diagram shows GSL profiles during development of the mouse nervous system. Mouse embryonic developmental stages are from single cell (∼ day 1), 16 cells (∼ day 3) to fetal (day 19). The mouse embryonic and neural developmental stages are described (320). Colored (vertical) bars above the timeline illustrate overlapping developmental stages. The horizontal gradient bars show the dynamic changes of GSL and ganglioside levels that occur during the stages of mouse embryo and neural development based upon experimental observations (22, 39, 40, 43, 44) (Sun et al., unpublished observations). The dark green indicates increased levels of the specific lipids and the less dense green implies lower levels. Ceramide could be identified at 2-4 cell stage (39). The hatched bar demonstrates the hypothetical ceramide levels since ceramide synthesis remains active throughout life.

In the mouse embryo, ceramide, the core structure of GSLs, is detected by the 2-4-cell stage following fertilization, before neural tube formation, and is present throughout life (39, 40). The globo-series lipids occur at the 2-cell stage (E0.5) followed by the lacto-series at E1.5, and the ganglio series at E7 (40–42) (Fig. 4). GlcCer is present by E11 during the neuronal stem cell proliferation stage. The concentrations of GlcCer are greater during the neurogenesis and astrocytogenesis at mid-embryonic stages (E12 and E14); these steadily decline at later stages (43, 44). By postnatal day 11, GlcCer continues to decrease coincidently with axonal dendritic arborization during adulthood (43) (Sun et al., unpublished observations). Around E16 during fetal development, the central nervous system (CNS) ganglioside distribution patterns shift sequentially from predominantly GM3 and GD3 to the a- and b-series (GD1a, GD1b, and GT1b) and GM1 (22). GalCer and sulfatide become detectable at E17 and predominate at maturity in the adult mouse brain (43). A steady increase in sulfatide content begins at about postnatal day 7 and continues into adulthood in the rat, correlating with active myelin formation. This is regional, because sulfatide levels in the spinal cord are 5-fold higher than in cerebral cortex (45).

These lipid shifts are primarily modulated by differential expression of specific glycosyltransferases because glycosidases vary little during brain development. GD3-synthase and GM2/GD2-synthase are key enzymes in ganglioside biosynthetic pathways (Fig. 1). GM2/GD2-synthase expression significantly increases during in utero development (46–48) and ex vivo in differentiating primary neural precursor cells (43). In comparison, the key enzymes, GCS, ceramide UDP-galactosyltransferase (CGT), and GM3 synthase are not differentially expressed during development (43).

Defects of GSL biosynthesis in mice and some human patients provided insights into the importance of GSLs and gangliosides during brain development (Table 2). The specific roles of GSLs in survival, proliferation, and differentiation have been demonstrated by knockout mice with embryonic lethality (GCS and SPT) (49, 50) and severe neurodegenerative diseases (CGT) (51, 52). Disrupted gangolioside synthesis in mice with either GM3 synthase (53, 54), GM2/GD2 synthase (55), or α-N-acetyl-neuraminide α-2,8- sialyltransferase (GD3 synthase) (56) knocked out causes differential neurological impairments with normal brain formation. Mice lacking CGT are unable to synthesize galactosylceramide. They showed normal growth but had nerve conduction deficits (51, 52). A compensatory increase in GlcCer was observed. The early embryonic lethality of the GCS-deficient mouse delineates the essential roles of complex GSLs in survival (50). Furthermore, the neurodegeneration in the GCS neuronal knockout showed the importance of GSLs in the maintenance of the CNS (57, 58).

TABLE 2.

Disorders of GSL and ganglioside synthesis

| Affected Gene(s) | Enzyme, Name(s) | Affected GSLs | Species | Phenotype | Lifespan | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPTLC1 | Serine palmitoyltransferase, long chain base unit 1, SPTLC1 | Increased de novo glucosyl ceramide, accumulation of neurotoxic 1-deoxy-sphinganine and 1-deoxymethyl- sphingonine | Human | Distal sensory loss, sensorineural hearing loss starting between 20 and 50 years | Normal | (59, 60, 62) |

| Sptlc1 Sptlc2 | Serine palmitoyltransferase, long chain base unit 1 Sptlc1 or 2,SPT Sptlc1−/− and Sptlc2−/− Sptlcl+/− and Sptlc2+/− | Mouse | Embryonic lethal | (49) | ||

| Decrease ceramide and sphingosine in liver and plasma, decreased SIP levels in plasma | ||||||

| SIAT9 | GM3 synthase CMP-NeuAc:LacCer α2,3-sialyltransferase LacCer α-2,3-sialyltransferase | No a- and b-series gangliosides | Human | Developed severe epileptic seizures starting between 2 weeks and 3 months | 2–18+ years | (64) |

| Siat9 | GM3 synthase ST3 β-galactoside α-2,3-sialyltransferase | Mouse | Hearing loss detected 13 days after birth; increased insulin sensitivity detected in 6–8 week old mice | Normal lifespan | (53, 54) | |

| Siat8a | GD3 synthase CMPsialic acid:GM3 -2,8-sialyltransferase α-N-acetyl-neuraminate α-2,8- sialyltransferase | No b-series ganglioside | Mouse | Normal | Normal lifespan | (56) |

| GALGT1 | GM2/GD2 synthase UDP-N-acetyl-D-galactosamine: UDP-GalNAc: GM3 N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase | GM3 accumulation | Human | Poor physical and motor development, frequent seizures | 2–3 months | (61) |

| Galgt1 | GM2/GD2 synthase UDP-N-acetyl-D-galactosamine: GM3/GM2/GD2 synthase, β-1,4-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase, GalNAcT. | Lack all complex gangliosides, express high levels of GD3 and GM3 | Mouse | Slight reduced neural conduction velocity due to axonal and degeneration and demyelination in CNS and PNS, detected in 10–16 week old mice, males infertile | > 1 year | (55, 365, 366) |

| Galgt1 + siat8a | GM2/GD2, and GD3 synthases | GM3 ganglioside only | Mouse | Fatal audiogenic seizures and peripheral nerve degeneration detected in 2–4 month old mice, males infertile | 3–9 mos | (367) |

| Galgt1 + Siat9 | GM2 and GM3 synthases | No higher order gangliosides | Mouse | Severe neurodegeneration hind limb weakness, ataxia, and tremors starting at 2 weeks old | 2–5 mos | (368) |

| Cgt | Galactosyltransferase CGT | Lack galactosylceramide and sulfatide | Mouse | Severe generalized tremor and mild ataxia starting between 1 and 2 weeks | 2.5–4 weeks | (52) |

| Lack galactosylceramide and sulfatide | Mouse | Severe dys/demyelination and loss of nerve conduction velocity starting between 1 and 2 weeks | 3.5–4 weeks | (51) | ||

| Ugcg | Glucosylceramide synthase GCS | No GlcCer-based gangliosides | Mouse | Embryonic lethal | E7.5 | (50) |

| Ugcg knockout in neurons and glial cells | Trace levels of GlcCer- based gangliosides in neural and glial cells | Mouse | Cerebellum and peripheral nerve dysfunction, reduced axon branching of Purkinje cells beginning at 5 days after birth | 3 weeks | (58) | |

| Ugcg knockout in keratinocyte cells | Decreased GlcCer in epidermis | Mouse | Desquamation of the stratum corneum, transdermal water loss leading to death starting from 3 days postnatally | 5 days | (369) |

To date, three human diseases are associated with mutations in enzymes involved in de novo GSL synthesis (59–61). SPT consists of three subunits and catalyzes the first step in sphingolipid synthesis (Fig. 1). Six missense mutations in SPT long-chain subunit 1 (SPTLC1) were reported in 26 families that have autosomal dominant hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy type 1 (62, 63). These SPT mutations caused changes in substrate specificity that led to formation of two atypical neurotoxic deoxyl-sphingoid bases by condensation of palmitoyl-CoA and alanine or glycine, instead of serine (62). Thus, hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy type 1 is caused by a gain-of-function mutation. GM3 synthase catalyzes the first step of complex gangliosides synthesis (Fig. 1). A loss-of-function mutation in GM3 synthase (SIAT9) was identified in a cohort characterized by autosomal recessive infantile-onset symptomatic epilepsy syndrome (64). A nonsense mutation in exon 8 of the GM3 synthase gene produced premature termination that could abolish enzymatic activity (64). Affected individuals are homozygous for the mutation while heterozygous carriers are unaffected (64). A single case of GM2 synthase deficiency was reported by biochemical characterization only (61). The patient died at 3 months after presenting with abnormal motor function and seizures. GM3 accumulated in the brain and liver (61).

Phenotypic analyses from GSL synthase-deficient mice reveal that lack of all GSL is incompatible with embryonic development (49, 50). Simple to complex GSLs are nonessential for early brain development but are important for brain maturation and maintenance (51–56). Compensatory interchange between various GSLs also signifies additional complexities in their metabolism.

Distribution and functions of GSLs

The sialic acid-containing GSLs are ubiquitously expressed in the outer leaflet of the plasma membranes, e.g., liver (65), and are most abundant in CNS and other nervous tissues (22, 65, 66), but there is significant tissue/ regional variability in distribution. High concentrations of GD1a are present in extraneural tissues, erythrocytes, buffy coat, bone marrow, testis, spleen, and liver, whereas different GSLs are in high amounts in other tissues, e.g., GM4 in kidney, GM2 in bone marrow, GM1 in erythrocytes, and GM3 in intestine (19). GA2, GM2, and GM3 are at very low or nondetectable levels in normal brains from humans, cats, and mice (66). Cellular specificity is exemplified by GD1b localization to small neurons, whereas O-Ac-disialoganglioside localizes to large neurons (67). In liver, GM1 was detected on the canalicular and sinusoidal lining cells, but nearly absent from liver parenchymal cells; GM1 was increased in hepatic sinusoidal membranes during cholestasis (68). In skeletal muscle, the neutral GSLs and gangliosides were mostly in membrane vesicles with GlcCer predominating and only trace levels of LacCer (69, 70). GalCer, sulfatide, and sphingomyelin are structural to myelin sheaths and are major lipids in oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells (71). In skin, ceramide comprises about 50% of total epidermal lipid and is generated from GlcCer in the lamellar bodies (72). These cellular microdifferences in GSLs indicate subtle, yet potentially important, metabolic roles that have not been elucidated. Cellular distribution of GSLs can be altered in pathologic states. In MDCK kidney cells, mitochondrial and peroxisomal GSLs are very low/absent (73), whereas GD1b and GD3 had high contents in mitochondria from malignant hepatomas (74). During the apoptotic process, GD3 is rapidly synthesized and relocated from the cis Golgi to mitochondria, leading to the opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pores and release of apoptogenic factors (75).

GSLs have differentially ordered domains to create selectivity in membrane transport that is important in the spatial organization of cells (76). GSLs are enriched to 30–40 mol% in some cell types, e.g., in the apical membranes of intestinal and urinary tract epithelial cells or in the myelin of axons (77–79). Complex GSLs are generally enriched on the plasma membrane, but GlcCer is mostly localized to intracellular membranes (80). GSLs are found in the vacuoles of the exocytotic and endocytotic systems with low content in the ER (65, 73). Complex GSLs are not translocatable to the cytosolic surface of Golgi (81).

Rafts are ordered structures that participate in cell recognition and signaling. These microdomains or lipid rafts are composed of GSLs, sphingomyelin, and cholesterol (33, 82) that provide environments for enrichment of specific proteins (83) in a variety of membranes. Examples include Src family kinases that are important for signal transduction (84), glycosylation-dependent adhesion/ recognition and signaling (85), and G-protein-coupled receptor-signaling (86).

Additional roles of GSLs, including ceramide, sphingosine, sphingosine-1-phosphate, lysoglycolipids, and lysogangliosides, are their inhibition or activation of apoptosis, proliferation, and stress responses (87). Cellular ceramide is an important second messenger in signal transduction that modulates a variety of these physiologic and stress responses (Fig. 2) (87). Several possible intracellular ceramide-target enzymes and signaling pathways have been proposed, including the activation of Ras/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-MAPK cascade (88), protein kinases PKCζ (89), kinase suppressor of Ras/MAPK (90), SAPK/JNK signaling pathway (91), Raf-1 (92), protein phosphatases PP1 and PP2A (93), and JNK (91); all contribute to the control of cell growth, proliferation, and death through various downstream intermediates.

For the field of GSL LSDs, a major challenge remains in the unification of the cell and developmental specificity, biological functions, and pathogenic mechanisms. Given the plethora of diverse and essential cellular functions, the severity of disruptions in GSL metabolism would be anticipated to include more than just accumulation of the GSL in cells and architectural distortions of specific cell types. Such mechanistic understanding of the GSL storage diseases is just beginning to be delineated (See below).

DISORDERS OF GSL AND GANGLIOSIDE DEGRADATION IN HUMANS AND MOUSE MODELS

The catabolic defects in neutral GSL and ganglioside metabolism result in LSDs with complex, multi-system progressive diseases, including neurodegeneration, that can present early in utero or childhood. All the catabolic enzymes for these diseases exist in the lysosomes (Fig. 3). Later onset and more attenuated variants of each disorder have been or are anticipated to be present in humans (Table 1). All these diseases are autosomal recessive except Fabry disease, which is X-linked. The phenotypic variants and the molecular causes have been variably delineated. Attempts have been made to correlate the genotype with phenotype. This is a complex and incomplete task because of the variability in presentation, nonuniform clinical delineation, and lack of complete allele characterization. However, the residual in situ hydrolase activities in patients are a major, but not unique, determinant of the age at onset and/or severity of the disease. Work by Sandhoff et al. (94) clearly established in situ residual activity as a critical correlate of phenotype with a direct, albeit nonlinear, relationship between this activity and the age at onset in Tay-Sachs disease and metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD). Extensive clinical data show similar correlations in Gaucher disease type 1 (95). Mouse models of several LSDs have been developed (Table 1). Although the mouse phenotypes are qualitatively similar to its corresponding human disease, such models can show substantial differences because of differences in GSL metabolism between humans and mice. Analyses of such mouse models of GSL synthesis and degradation have provided insight into early pathological mechanisms of GSL and ganglioside flux aberrations.

The disorders of ceramide, GSLs, and gangliosides degradation in humans and mice are summarized below. The phenotypes and genotypes of these disorders are summarized in Table 1.

Disorders of ceramide degradation

Disorders of ceramide degradation are caused by acid ceramidase (AC; EC 3.5.1.23) deficiencies that lead to Farber disease, a.k.a. Farber lipogranulomatosis (96, 97). AC catalyzes the hydrolysis of ceramide to free fatty acid and sphingosine, and its function is optimized by saposin D (Figs. 1 and 3) (98). However, AC can also synthesize ceramide from sphingosine and free fatty acids (Fig. 1) (99, 100). This reverse reaction is optimally catalyzed at pH ∼6.0 compared with the hydrolytic activity optimum of pH ∼4.5, suggesting that the two reactions likely occur in different subcellular compartments. There are seven variant forms of Farber disease that are distinguished by severity and tissue involvement (96). Although allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in Farber disease patients without CNS manifestation showed improvement in joint movement (101), there is currently no effective therapy for this disease. The AC-deficient mouse (Asah1−/−) undergoes apoptotic death at the 2-cell stage (E1; Fig. 4) because of excessive ceramide accumulation (39, 102), demonstrating that AC is expressed in the embryo and that ceramide degradation is essential for survival beyond the 2-cell stage (E1) (102). In addition to increasing ceramide pools, loss of AC activity is thought to concurrently reduce pools of sphingosine and sphingosine-1-phosphate, two lipids known to promote cell growth and differentiation (103).

Disorders of GSL degradation

Mutations in the SMPD1 gene that encodes aSMase (ASM; EC 3.1.4.12) cause two types of Niemann-Pick disease: Types A and B (NPA and B) (Fig. 1, Table 1). NPA presents a neurovisceral phenotype, whereas NPB exhibits visceral manifestation (104). The ASM-deficient mice, developed independently in two laboratories, resemble NPA or NPB phenotypes (Table 1) (105, 106). Neither model has detectable lysosomal ASM activity in any tissue but has reduced levels of plasma membrane-bound nSMase activity, which cleaves nonlysosomal sphingomyelin at neutral pH (Fig. 2) (106, 107). The ASM gene is expressed prior to E11 during neuronal stem cell proliferation, and deficient ASM activity, due to genetic defects, can lead to loss of signaling molecules that regulate their proliferation very early on in brain development (108, 109).

Krabbe disease, globoid leukodystrophy disease, is a rapidly progressive, demyelinating disease that results from insufficient cleavage of galactosylceramide and galactosylsphingosine by galactosylceramide-β-galactosidase (GALC; EC 3.2.1.46) (Table 1, Fig. 3). This enzyme has specificity for both galactosylceramide and galactosylsphingosine, the latter being a specific substrate for this enzyme whereas galactosylceramide can be cleaved by at least two other lysosomal β-galactosidases (Fig. 1) (110), potentially accounting for the lack of large accumulations of galactosylceramide in the CNS (111). GALC has a number of nonsynonymous polymorphisms (missense or nonsense mutations) that affect the expression and function of the enzyme (111, 112). There are four forms of the disease that differ in age of onset (113). Secondary pathological changes including reactive astrocytic gliosis, infiltration of unique and often multinucleated macrophages (globoid cells), and other inflammatory responses accelerate disease progression (111). Bone marrow/stem cell transplantation with histocompatible cells has shown some positive effects on the CNS and peripheral nervous system (PNS) phenotypes in the infantile onset disease when performed prior to the onset of significant neurological involvement. However, the dementia and other aspects of the CNS and PNS disease eventually lead to death (114). GALC-deficient mice (twitcher mouse) were discovered at the Jackson Laboratory in 1976 (115, 116). This naturally occurring model is an excellent model of the infantile human disease (117–119). A transgenic globoid leukodystrophy disease Krabbe disease model was created by ‘knock-in’ of a missense mutation (H168C) (120). The analyses of these models demonstrated that there is a correlation between accumulation of galactosylsphingosine and the neuronal defects. The accumulation of galactosylsphingosine was detected before myelin formation (119). Bone marrow transplantation in twitcher mice stabilized galactosylsphingosine at low levels accompanied with remyelination (121). These findings provide support for galactosylsphingosine as the offending agent responsible for triggering proinflammation, oligodendrocyte depletion, and dysmyelination in Krabbe disease.

MLD is caused by a deficiency of arylsulfatase A (ASA; EC 3.1.6.8) that leads to the accumulation of sulfatide, a major lipid of myelin, in the CNS and PNS (Fig. 3) (122, 123). Currently, five allelic forms of ASA deficiency exist (Table 1). Also, there are two nonallelic variants of ASA deficiency: 1) MLD due to saposin B deficiency (described below) leads to inability to cleave sulfatide and globotrioaosylceramide (Gb3) in vivo as a result of the activator protein deficiency and impaired lipid presentation to the enzyme, even though ASA and α-galactosidase A are normally expressed and without mutations (124); and 2) multiple sulfatase deficiency is a disorder that combines features of a mucopolysaccharidosis with those of MLD (125) and results in a deficiency of all cellular sulfatases due to defects in a posttranslational enzyme essential for modification of an active site cysteine that is present in all sulfatases (122, 126). Details of multiple sulfatase deficiency have been reviewed (125, 127). For the infantile and juvenile MLD variants, bone marrow/stem cell transplantation has been attempted with initial improvement/stabilization followed by later progression of the CNS and PNS diseases (128). ASA-deficient mice (Asa−/−) have a very slowly progressive sulfatide storage resembling the early stages of human cases (129). A more severe phenotype of ASA deficiency was achieved by overexpressing the transgene for the sulfatide-synthesizing enzyme, galactose-3-O-sulfotransferase (CST), encoded by Gal3st1, in oligodendrocytes (130). These models have been used in preclinical trials of MLD (131, 132).

Fabry disease, the only X-linked GSL storage disease, is due to a deficiency of α-galactosidase A (133), the enzyme that cleaves Gb3 and di-galactosylceramide (Fig. 3, Table 1). Uncharacteristic of most X-linked traits, both males and females have significant to major clinical involvement (134). Affected patients accumulate the substrate, Gb3, in most tissues and organs (135), but the progressive deposition of Gb3 in capillary endothelial cells leads to many of the morbid manifestations (136). Increased deacylated Gb3, globotriaosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb3), in patient plasma suggests that it may be involved in pathogenesis of Fabry disease (137). The mouse model of Fabry disease (Gla−/−) has accumulation of Gb3 in peripheral nerves and alterations of sensory nerve function that resembles neuropathic pain in Fabry disease patients (138). Gb3 accumulation in endothelium leads to vascular dysfunction, thereby providing an in vivo model to delineate the basis of cardio- and cerebrovascular complications associated with Fabry disease (139, 140).

Gaucher disease results from insufficient cleavage of GlcCer and glucosylsphingosine by the lysosomal enzyme, acid β-glucosidase or glucocerebrosidase (GCase) (Fig. 3) (95, 141). A homologous pseudogene (ψGBA) located 16 kb downstream from the GBA gene has complicated the molecular diagnosis of Gaucher disease (142). The phenotypes are a continuum of degrees of involvement but can be divided categorically into neuronopathic (types 2 and 3) and nonneuronopathic (type 1) variants (Table 1). A nonlysosomal β-glucosidase (GBA2) has been identified as participating in GlcCer degradation (143). Inhibition or knockout of GBA2 activity is associated with GlcCer accumulation in testis and impairment in spermatogenesis (144). However, the link of GBA2 to Gaucher disease is unclear. Enzyme replacement therapy has been successfully used to treat Gaucher disease type 1 (145), whereas new substrate synthesis inhibition and enzyme enhancement therapies are in clinical trials to treat type 1 and 3 diseases (146, 147). There are no direct treatments available for Gaucher disease type 2. The Gaucher disease mouse models (Table 1) demonstrate that accumulation of GCase substrates, GlcCer and glucosylsphingosine, begin at embryonic day 13 (148). Also, substrate storage does not affect brain formation but does lead to early and severe degeneration of the brain and disruption of the skin permeability barrier (149, 150). The downstream biological consequences of GlcCer and glucosylsphingosine accumulation are currently being investigated (see section III).

Disorders of ganglioside degradation

Two types of ganglioside degradation disorders are characterized. GM1 gangliosidosis results from deficiency of lysosomal GM1-β-galactosidase (EC 3.2.1.23) that cleaves ganglioside GM1 (Fig. 3, Table 1), its asialo derivative, GA1, galactose-containing oligosaccharides, keratin sulfate, and other β-galactose-containing glycoconjugates including galactosylceramide (151). GM1-β-galactosidase is part of a multi-enzyme complex with α-neuraminidase and "protective protein"/cathepsin A (152, 153) that is assembled posttranslationally during transit through the Golgi (154). There is an inverse correlation between disease severity and residual β-galactosidase activity in GM1 gangliosidosis patients (155). GM1 gangliosidosis mice show severe neurological defects and resemble the human disease (156, 157). Preclinical studies using substrate reduction and gene therapies have been tested in animal models of GM1-gangliosidosis (158–160).

GM2 gangliosidoses are a group of severe neurodegenerative disorders unified by the excessive accumulation of GM2 ganglioside mainly in neuronal cells. GM2 is specifically hydrolyzed by β-hexosaminidase A (EC 3.2.1.52) (Fig. 3). Two genes are required for the formation of this enzyme. The HEXA and HEXB genes encode the α- and β-subunits, respectively (161, 162). The subunits assemble in the Golgi forming αβ2 [β-hexosaminidase A (Hex A)] and β3 [β-hexosaminidase B (Hex B)] (161, 163, 164). The nonallelic GM2A gene encodes the GM2 activator protein that complexes with the ganglioside GM2 (165) (see below). Defects in any of these three genes may lead to impaired degradation of GM2 gangliosides and related substrates. Tay-Sachs disease (variant B) is the classic GM2 gangliosidosis and results from the deficiency of the α-subunit that produces the specific loss of Hex A, whereas Hex B is at normal or somewhat increased levels, thereby designated as variant B (161). This specific deficiency in Hex A produces GM2 ganglioside accumulation in brain, because GM2 ganglioside is synthesized in appreciable amounts only in the CNS (Fig. 3). Currently, there is no effective treatment for Tay-Sachs disease, although trials of "molecular chaperone" approaches are underway for the late onset variants with residual Hex A activity (166). Sandhoff disease (variant 0) is caused by mutations of the HEXB gene that leads to loss of the β-subunit, resulting in deficiency of both Hex A and Hex B activities (Fig. 3). Unlike Tay-Sachs patients who store mainly GM2-ganglioside, Sandhoff patients accumulate additional N-acetyl β-galactosyl terminated glycolipids and oligosaccharides in the CNS and viscera (167, 168).

The Tay-Sachs disease mouse model (Hex A−/−) displays a milder phenotype compared with Tay-Sachs patients. This is accounted for by the differences in GM2 catabolism between mouse and human (169). Two pathways have been proposed for GM2 metabolism in mice. One involves GM2 hydrolysis to GM3 mainly by Hex A and GM2 activator, which is the major pathway in humans (Fig. 3) (161). The second one is specific to mice and involves GM2 hydrolysis by sialidase first to GA2 and then to LacCer by Hex B. In Hex A−/− mice with a complete loss of Hex A, GA2 can be degraded by Hex B (169). Unlike Hex A−/− mice that have minor GM2 storage in neurons and no detectable neurological impairment, Sandhoff mice (Hex B−/−) are severely affected. The lack of Hex A and B activities in Sandhoff mice provides an authentic model of acute human Sandhoff disease (169). Substrate reduction therapy with N-butyldeoxygalactonojirimycin (NB-DGJ), an imino sugar that inhibits GCS, has been tested in adult (170) and neonatal (171) Sandhoff mice. NB-DGJ significantly reduced total brain and GM2 ganglioside content when administered from postnatal days 2–5 in Sandhoff mice to a greater extent than in the adult mice. No adverse effects were found with NB-DGJ treatment in either age group. These results indicate that earlier intervention is an effective method for managing GSL LSDs.

Activator protein deficiency

The physiologic importance of sphingolipid activator proteins in GSL degradation has been highlighted in the patients with mutations in the GM2 activator and the prosaposin genes; the latter encodes a precursor of four saposins (A, B, C, and D).

GM2 activator (variant AB) deficiency is caused by mutations that lead to an inability to form GM2/GM2-activator complexes in the presence of normal amounts of Hex A and Hex B (Fig. 3) (165, 172, 173). Mechanistically, the GM2 activator protein is a "liftase" that extracts GM2 from intra-lysosomal membranes making the GM2 terminal N-acetyl-galactosamine accessible to β-hexosaminidase A for cleavage (174). The Gm2a−/− mice store mostly GM2-ganglioside and low amounts of GA2 (175), similar to the Hex A−/− mice, thereby establishing its essential role in the GM2 catabolism (175).

Prosaposin/total saposin deficiency was found in four families and was associated with multiple GSL storage (Table 1) (176–178). Saposin (Sap) A is an in vivo activator for GALC (124). Sap B has lipid transfer properties and participates in degradation of sulfatide by ASA, digalactosylceramide, and Gb3 by α-galactosidase A, and GM1 ganglioside and LacCer by β-galactosidases (Fig. 3) (179, 180). Sap C is required for GCase to achieve maximal activity in vitro and ex vivo and protects GCase from proteolysis (181, 182). In comparison to Sap B, Sap C physically interacts with either phospholipid membrane or acid β-glucosidase to optimize this enzyme's activity (183, 184). Direct binding of Sap C to the substrate, GlcCer, has not been shown as part of this optimization (185, 186). Individual Sap A, Sap B, or Sap C deficiencies in humans are rare (181, 187–189). Sap D activates AC for degradation of ceramide. Heteroallelic mutations were identified in the Sap D domain in a patient with an additional mutation in the Sap C domain on a different allele (189). Prosaposin and all four Sap-deficient mice have been developed (98, 190–194). In general, individual Sap deficiencies in mice results in slowly progressive diseases compared with total Sap-deficient mice or their cognate enzyme knockout mice (Fig. 3, Table 1). These could be due to cross-compensation in GSL degradation by multiple saposins (Fig. 1). Proinflammation is a common pathological finding in the CNS from such models because of GSL accumulation. The clinical, pathological, and biochemical phenotypes of prosaposin knockout mice closely resembles those of the human disease, whereas Sap B−/− and Sap C−/− models are more slowly developing than those in humans.

Lipid trafficking disorders

Niemann Pick disease Type C (NPC) is not a disorder directly related to the metabolism of GSLs and gangliosides but rather has major involvement in the egress of free cholesterol from the lysosome (195). NPC is characterized by the accumulation of unesterified cholesterol and other lipids in endosomal/lysosomal compartments that stem from inherited deficiencies of the NPC1 or NPC2 proteins. NPC1 is a transmembrane protein and NPC2 is a soluble protein. Both are involved in intralysosomal cholesterol trafficking (196). Recently, NPC2 was proposed to act as a donor of cholesterol to NPC1 that facilitates cholesterol transport across the lysosomal membrane (196). Loss-of-function mutations in the NPC1 gene also lead to failure of the calcium-mediated fusion of endosomes with lysosomes, resulting in the accumulation of GlcCer, LacCer, and GM2 in late endosomes and lysosomes (195). The exact mechanism of disease causality by either cholesterol (primarily) or GSLs (secondary or primary) accumulation has not been resolved. Elevation of sphingosine was found before cholesterol and GSL accumulation (195). The importance of sphingosine in NPC1 has been addressed recently (197). NPC1-deficient mouse models (NPC1−/−) show similarities with the human clinical NPC1 phenotypes (198). Lipid profile and disease phenotype in NPC1, NPC2, and NPC1/NPC2 double mutant mice were qualitatively and quantitatively very similar, indicating that both proteins operate cooperatively without compensation for each other in trafficking cholesterol to the lysosomes (196, 198–200).

Most GSL LSDs present with neurological phenotypes that begin early in life. The analyses of the mouse models show that the lipid accumulation in the CNS starts very early on in development. Such storage may subtly alter brain and cellular functions. GSL accumulation has been postulated as a trigger to abnormal cellular responses that potentiate the pathological disease process. Although some of the mouse phenotypes differ from the analogous human disease, the biochemical profiles in the GSL synthesis or degradation pathway have provided insight into the pathological mechanisms and GSL flux aberrations. However, systematic analyses of GSL profiles in relation to early brain development (Fig. 4) and the early molecular events have yet to be elucidated. Such understanding should be useful in defining the initiating and propagating mechanisms that would provide a road map for designing therapeutic strategies.

PATHOLOGICAL CONSEQUENCES OF DISORDERS IN GSL METABOLISM

GSL disorders present complex disease phenotypes and diverse pathological changes. The defects in GSL metabolism affect cellular and molecular functions and lead to abnormalities of the CNS and visceral organs (Fig. 5). The mechanisms leading to this pathology are poorly understood. Are these disorders triggered by accumulated lipid or insults from secondary molecular defects in the cells? Does inflammation potentiate the disease? What causes neuronal drop out? Could lesions result from lack of products as well as from storage of substrate in the GSL pathway? The following section summarizes some of the pathological and molecular findings, which may be preludes to understanding the signature pathways in the GSL diseases.

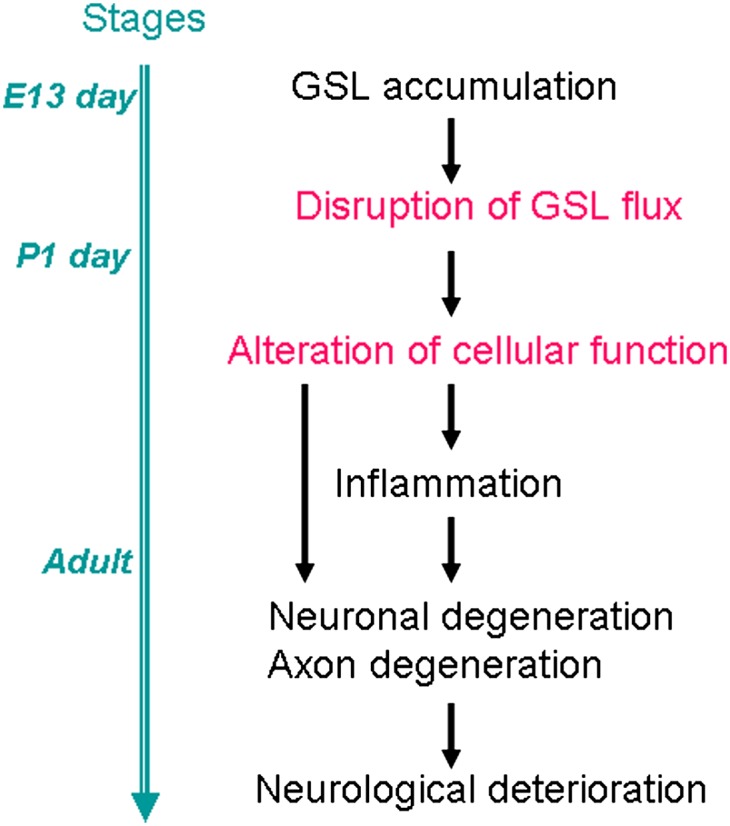

Fig. 5.

Hypothetical scheme for neuronal disease progression in the nervous system. Accumulation of GSLs causes abnormalities of neuronal cell functions in mouse models and the human diseases. Abnormal degradation of GSL may disrupt the normal flux of GSL in the cell, which can affect a variety of cellular functions. How the GSL accumulation alters GSL flux and cellular function is largely unknown. The changes of the cellular function may cause neuronal degeneration. Inflammation is often detected before the neuronal and axonal defects and it plays a role in potentiating disease progression. The blue line on the left shows the stage of brain development.

Evidence of GSL accumulation correlating with disease progression

Disruption of GSL flux is thought to initiate and potentiate LSD phenotypes. The slow accumulation of sulfatide in Asa−/− mice does not disrupt myelin formation, which occurs in the first 3 weeks postnatally in the mice but does destabilize myelin integrity in adults (201). Although lysosomal accumulation of Gb3 begins in utero, the signs and symptoms of Fabry disease may not be apparent until childhood or adolescence (202). The association of GlcCer, and, especially glucosylsphingosine, with neuronal toxicity is evident in humans and mice with Gaucher disease. GSL composition studies show that glucosylsphingosine and GlcCer in Gaucher type 1 brains are substantially lower (3–10%) than that in Gaucher disease type 2 brain (203), suggesting a relationship between substrate accumulation and severity of brain disease. Galactosylsphingosine levels in twitcher mice brain progressively increase from 20 to 40 days as does the neurological phenotype (119, 204). Unlike galactosylsphingosine in Krabbe disease, glucosylsphingosine has not been proven in vivo as a direct cause of CNS Gaucher disease. However, a recent glucosylsphingosine storage disease mouse model supports this concept (205). The correlations between disease progression and age-dependent GSL levels also occur in NPC disease (206), Tay-Sachs disease (207), and GM1 gangliosidosis mice (156).

GSL accumulation occurs prior to the onset of a disease phenotype, e.g., glucosylsphingosine accumulation was found at the 11th week of pregnancy in human Gaucher disease (208). Elevated glucosylsphingosine can be detected as early as E13 during neurogenesis in Gba knockout mice (208). In V394L/SapC−/− mice, increased glucosylsphingosine is present by 14 days, i.e., before the onset of neurological signs at 30 days (Table 1). Abnormal accumulation of galactosylsphingosine in twitcher mice is detected in the brain and sciatic nerves at postnatal day 7, before the onset of demyelination, and progressively increases to 100-fold normal levels, predominantly in white matter (209, 210). In normal mice, GM2 is not detectable, but GM2 is elevated at postnatal day 2 in Sandhoff mice before any pathological signs (171). Such early lipid accumulation may trigger molecular alterations, e.g., proinflammation, as shown by global gene expression analyses in Sandhoff disease mice in which upregulation of inflammation-related genes preceded neuronal death (211). Similar temporal analyses of CNS tissues from prosaposin-deficient mice reveal the regionally specific gene expression abnormalities including upregulation of numerous proinflammatory genes prior to neuronal degeneration (212). Although low-level excess of GSLs may not lead to early histopathological changes, they do cause cellular alterations that initiate disease processes leading to eventual end stage disease. A final common pathway in the CNS for the GSL LSDs appears to be varying types and degrees of inflammatory and proinflammatory reactions leading to apoptotic or other types of programmed cell death.

Increased lipid levels at early embryonic stages also correlate with reduced expression of genes for neurotrophic factors [brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF)] and MAPK pathway genes (ERK) in the cortex, brainstem, and cerebellum of neuronopathic Gaucher disease mice at E17.5, E19.5, and P1 (213). The deficiencies in neurotrophic factors (BDNF and NGF) cause sensory neuron degeneration in mice (214, 215). These early abnormalities in lipid and neurotrophic factors correlated with substantial reductions in cellular density, neurodegeneration, and microglial infiltration in Gba knockout mouse brains at E13–14 (149, 150, 208). Injection of the GCase inhibitor (cyclopellitol) into wild-type mice led to a 17- to 31-fold increase of glucosylsphingosine in brain, liver, and spleen with concomitant neurological abnormalities (216). These findings provide further evidence for the relationship of abnormal substrate levels in GCase deficiencies and neuronopathic phenotypes. These data suggest that a toxic stimulus is present long before birth or at least early in postnatal life, and that therapy begun during infancy may not prevent progressive neurologic damage. In this regard, the conditional experiments of Xu et al. (150) are instructive. A chemically induced model of CNS Gaucher disease was produced by administering a covalent inhibitor, conduritol B epoxide (CBE), of GCase to neonatal mice (150). Wild-type and GCase point mutated mice were given daily injections of CBE from postnatal day 5 to day 11. About 1 day after CBE treatment was stopped, the mice developed neuropathic signs. No mice survived if CBE was continued through day 13. Because the wild-type and mutant GCases have t1/2 ∼60 h in cells (217), the neuropathic signs in wild-type mice or those with D409H homozygosity stabilized for the next several months in the absence of CBE. However, with a lower activity mutant, D409V/null, the neuropathic signs progressed to very severe within 2 months; unlike the wild-type and D409H homozygotes, the glucosylceramide levels in brain did not decrease, and there was continuing evidence of neuroinflammation. These data support the concept that specific reconstitution levels of in situ activity must occur at the appropriate developmental time frame to avoid propagation of disease. Furthermore, once established, the neuronopathic disease does not resolve but can be stabilized.

Secondary storage or deficiency of GSLs

Alterations of GSL flux can directly affect membrane composition and disrupt cell homeostasis that may cause secondary storage (38) and potentiate disease processes. Such secondary accumulations of GSLs and gangliosides are common features associated with neuropathology in several LSDs, e.g., Niemann-Pick diseases with GM2 and other GSL accumulation (218–220). Pronounced increases in gangliosides, GlcCer, and LacCer occur in prosaposin deficiency (178, 190) and increases in GM2 and GM3 are evident in the cathepsin D-deficient mouse (221), as they are in the CNS of several mucopolysaccharidoses, MLD, Tay-Sachs disease, and Gaucher disease (222). Importantly, in neurons with secondary gangliosides accumulation, the pathological changes were essentially identical to those in the gangliosidosis (223). Because GM2 and GM3 are precursors of many gangliosides and are the final common metabolites in the ganglioside degradative pathway (224), the discovery of secondary ganglioside accumulation indicates the importance of the endosomal/lysosomal system in the overall regulation of ganglioside expression in neurons.

In the NPC 1 mice, sphingosine accumulation reduces the lysosomal calcium pool and may trigger secondary GSL storage (195). GCase mutations, even in the heterozygous state, are predisposing factors for Parkinson disease (225, 226). It is unknown whether the GSL or other cellular abnormalities determine the association between these two diseases, but increased α-synuclein deposition and Lewy bodies occur in Gaucher disease type 1 brains (227).

A clear connection has yet to be established between the primary lysosomal defect and the accumulation or deficiency of secondary compounds that become involved in the storage process. Signal transduction derangements and altered trafficking of GSLs in the endosomal/lysosomal system would be possible causes. Regardless of the mechanism, secondary GSL storage compounds appear to be actively involved in disease pathogenesis.

Inflammation

Inflammation, constituting a local response to cellular insult, occurs in visceral and CNS tissues as a general pathological event in GSL and ganglioside LSDs. The excess lipid is causally linked to a proinflammatory response, including activation of the microglial/macrophage system to produce inflammatory cytokines leading to CNS damage. In Gaucher disease type 1, GlcCer accumulates mainly in cells of mononuclear phagocyte origin. Serum levels of macrophage-derived cytokines that are pro and antiinflammatory mediators have been variously elevated (228). They include IL-1α, IL-1 receptor antagonist, IL-6, TNFα, pulmonary and activation-regulated chemokine, and soluble IL-2 receptor (229–232). Such mediators clearly could play a role in disease progression (233–235). In ASM knockout mice, the majority of genes with elevated expression in lung and brain were those involved in the immune/inflammatory response (236). Activation of microglial cells and astrocytes in CNS and PNS parallels such cytokine increases. Ex vivo, gangliosides activate microglia to produce the proinflammatory mediators nitric oxide and TNFα (237). Alternatively, gangliosides also suppress toll-like receptor-induced proinflammatory cytokine expression (238). In Sandhoff disease mice and humans, macrophage/microglial activation and subsequent cytokine expression result in neuronal dysfunction (211). Similarly, progressive CNS inflammatory changes were coincident with the onset of clinical signs in Tay-Sachs, Sandhoff, and GM1 gangliosidosis mice (239).

Use of antiinflammatory drugs in several GSL LSD models slowed disease progression (240, 241). This indicates that multiple inflammatory pathways participate. Nonsteroidal cyclooxygenase-dependent antiinflammatory drugs (e.g., indomethacin, aspirin, and ibuprofen) extended the lifespans of Sandhoff disease and NPC1 mice (240, 242). In Sap A−/− mice, such treatment suppressed only early, but not later, proinflammation, indicating involvement of the cyclooxygenase pathway, but it is not the major inflammatory pathogenic pathway (Barnes et al., unpublished observations). Strikingly, continuous high levels of estrogen during the pregnancy period of Sap A−/− mice protected against proinflammation and demyelination even though galactosylceramide and galactosylsphingosine continued to accumulate (191, 243). These studies implicate the proinflammatory reactions in the propagation and potentially initiation of GSL-mediated CNS degeneration.

The underlying molecular mechanisms of GSL- or ganglioside-induced inflammation are not fully elucidated. Several disparate results have suggested signaling pathways. Macrophage inducible nitric oxide synthase can be regulated by GSL-mediated intracellular calcium elevation (244). AMP-activated protein kinase plays a role in regulating astrocytic galactosylsphingosine-mediated inflammatory responses (245). Similarly, sulfatide induces inflammatory cytokine production in microglia and astrocytes in addition to stimulating phosphorylation of p38, ERK, and JNK (246). Whole genome transcriptome analyses of prosaposin-deficient mice implicated CEBPδ as a common mediator in the STAT3 proinflammatory pathway (212). GlcCer-derived ceramide may play an antiinflammatory role by mediating p38δ MAPK activation, p38δ phosphorylation, and regulation of IL-6 (247); the partial deficiency of GlcCer-derived ceramide in Gaucher disease may release, via p38δ MAPK, suppression of IL-6 and the consequent downstream inflammatory effects (247). Greater insights into these basic mechanisms could facilitate developing adjunctive approaches to altering the progression of CNS disease in the GSL LSDs.

Several GSLs have roles as immune modulators through invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cell selection that relies on interaction of glycolipid antigens through the MHC class I-related glycoprotein CD1d in late endosome/lysosomes (248, 249). In addition to α-galactosylceramide, the mammalian lipid, isoglobotrihexosylceramide, was proposed as an endogenous glycolipid antigen (249). This has been questioned since the isoglobotrihexosylceramide synthase knockout mice do not have iNKT cell abnormalities (250). Deficiency of iNKT cells occurs in prosaposin deficiency, Sandhoff disease, and NPC1 disease (248, 249), indicating that several GSLs, gangliosides, and lysophospholipids may participate in iNKT cell selection (251), but the role of these cells and the molecular connection remain unclear.

Neuronal degeneration