Abstract

Outbreak strains of Acinetobacter baumannii are highly clonal, and cross-infection investigations can be difficult. We sought targets based on AbaR resistance islands and on other genes found in some, but not all, sequenced isolates of A. baumannii among a set of clinical isolates (n = 70) that included multiple representatives of a number of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE)-defined types. These included representatives that varied in their profiles at two variable-number tandem repeat (VNTR) loci, which can provide discrimination within a PFGE cluster. Detection, or not, of each element sought provided some degree of discrimination among the set, with the presence or absence of genes coding for a phage terminase (ACICU_02185), a sialic acid synthase (ACICU_00080), a polysaccharide biosynthesis protein (AB57_0094), aphA1, blaTEM, and integron-associated orfX (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes [KEGG] no. K03830) proving the most helpful in discriminating between closely related isolates in our panel. The results support VNTR data in describing distinct populations of highly similar isolates. Such analysis, in combination with other typing methods, can inform epidemiological investigations and provide additional characterization of isolates. Most genotypes carrying blaOXA-23-like were PCR positive for a yeeA-blaOXA-23 fragment found in an AbaR4-type island, suggesting that this is widespread.

INTRODUCTION

Acinetobacter baumannii has emerged as an important nosocomial pathogen, particularly in intensive care units, not least because it is often associated with resistance to the vast majority of antibiotics (8). Hospital isolates, particularly from outbreaks, usually belong to one of two clonal lineages, originally described as European clones I and II but now known as “international” clones I and II, which are found globally; there is also a third international lineage (clone III) and novel types (ST15, ST25, and ST78), but these are less common (7, 9, 28). These lineages include a number of sublineages, which can be distinguished by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), or similar techniques, but it is clear that even the sublineages are found in multiple hospitals, and “fine typing” within a PFGE cluster has become necessary for cross-infection investigations. For example, the predominant PFGE type from United Kingdom hospitals, known as OXA-23 clone 1, a sublineage of international clone II, has been found in over 60 hospitals. We have successfully used variable-number tandem repeat (VNTR) analysis at two highly discriminatory loci to provide fine typing within a PFGE cluster, which does appear to reflect the known epidemiology (29). However, the finding of genetically similar isolates in multiple locations, sometimes with no known epidemiological link, raises questions about the relative roles of spread and selection by antibiotics, and it would be helpful to compare these isolates in more detail.

The whole-genome sequences of an ever-increasing number of isolates of A. baumannii have been determined and are available in GenBank (e.g., CP000521 and CP000863). In addition, a number of “AbaR”-type resistance islands, inserted in an ATPase gene (here called comM) and carrying genes associated with resistance to antibiotics and heavy metals, have been described previously (1, 2, 11, 16, 17, 20, 21). The latter show diversity, with that described in an isolate of international clone II (AbaR2 in ACICU) being considerably smaller than that found in isolates of international clone I; among the latter, a number of different islands have already been described. Comparative genomic studies, such as that by Adams et al. (1), have identified genes present in some isolates, but not in others, that make up the accessory genome; already, over 2,600 such genes have been described among sequenced isolates. This could be exploited in epidemiological studies. The presence of different acquired carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxacillinase (CHDL) genes in isolates of the international clonal lineages (and other isolates) is well documented, with blaOXA-58-like being particularly associated with isolates from Greece and Italy (10, 24), blaOXA-40-like being associated with isolates from Spain and Portugal (5, 6, 22, 23), and blaOXA-23-like being associated with those from the United Kingdom, Asia, and South America (3, 13, 19, 32). The study by Adams et al. (2) demonstrated that the resistance genotype of closely related isolates was variable, with each isolate examined having a unique genetic repertoire. Our aim was to seek genes of the accessory genome in numerous isolates, of known international clonal lineage and PFGE and VNTR type and various degrees of relatedness, to see if such analysis would be helpful in epidemiological studies.

(This work has been presented in part at the 8th International Symposium on the Biology of Acinetobacter, Rome, Italy, 1 to 3 September 2010.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates.

Our laboratory provides a typing service for this organism, and the majority of isolates were received from United Kingdom hospitals for this purpose. Thirty-six of the isolates were unselected isolates received during late 2009 and early 2010; the remainder (34 isolates) were “panel” isolates, selected to include multiple representatives of various PFGE clusters. This included isolates from all three international lineages and sporadic and minor strains, with some from other countries (France, Pakistan, Australia, Spain, Israel, the United States, and Canada), obtained from previous studies (e.g., references 27 and 28). Isolates in the set, therefore, ranged from those that were closely linked (within the same outbreak) through increasing degrees of diversity to those belonging to different international lineages and from those from the same ward and hospital to those from another continent.

Typing.

Isolates belonging to international clone I, II, or III were identified by the use of multiplex PCRs or had previously been identified as belonging to these lineages by sequence-based typing (28). This was also used to characterize strains A and CAC-10. PFGE of ApaI-digested genomic DNA and determination of the number of repeat units at two VNTR loci (VNTR-1 and VNTR-10) were carried out as described previously (29). To accommodate a polymorphism in sequences corresponding to the forward primer of VNTR-1, a slightly modified fluorescently labeled primer (GAAGAAATATAAAGTGARGG) was used in some determinations.

Detection of genes of the accessory genome.

Acquired CHDL genes found in A. baumannii and the class 1 integrase gene (int1) were detected by multiplex PCR (26, 31). O-antigen genes (ACICU_00080, ABAYE3807, A1S_0057, and AB57_0094) and regions of AbaR islands were detected using primer pairs (RIA, RIC, RID, RIE, and RIG) described by Adams et al. (1), as was also detection of a second island (RIK). Detection of the presence of an AbaR island by insertion in comM and detection of the AbaR-comM junction were carried out with primers described by Post et al. (21). Those for other elements (e.g., IS26, blaTEM, and aphA1) that can be found in AbaR islands were as used by Post and others (4, 12, 20). Primers for a copper resistance D gene (AB57_0657, ABAYE3207, and A1S_2941); cusS (coding for a sensor kinase; AB57_0660, ABAYE3204, and A1S_2938); a putative pilus subunit gene, filA (ABAYE3128 and ACICU_00635); a phage terminase gene (AB57_1270 and ACICU_02185); esvB (for ethanol-stimulated virulence; A1S_1232, ABAYE2526, ACICU_01218, and AB57_1375); a toxin-antitoxin target (ACICU_2140); a macrolide efflux pump gene (mel) (as in GenBank accession number EF102240); and a molybdate system target (ACICU_1787) were designed from regions of sequence that were common to all isolates for which sequence was available. Primers for detection and determination of the copy number of integron-associated orfX (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes [KEGG] number K03830, as in GenBank accession number AY922991) have been described previously (25). The aacA4-catB8-aadA1 integron (AY922989), usually associated with OXA-23 clone 1, was detected using the 5′CS integron conserved segment forward primer and a catB8 reverse primer and/or the aacA4-catB8 primer combination. A selection of primers from this study is described in Table 1; a full list of primers used, together with target information, is included in the supplemental material (see Table S1). KEGG numbers were found at http://www.genome.jp/kegg/.

Table 1.

Primers from this study for selected targetsa

| Target/primer pair name | Primer (5′ to 3′) | Size (bp) | Annealing temp (°C) | Locus tags/relevant GenBank accession nos. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cusS (K07644b) | GGACATTCCCTTTTCAGC | 219 | 55 | AB57_0660, ABAYE3204, A1S_2938 |

| TGTTTATCTCGTAGTCGGGA | ||||

| Copper resistance D gene (K07245b) | GGAAGTTTTGCCAATACAGG | 548 | 55 | AB57_0657, ABAYE3207, A1S_2941 |

| CCATTTGTTAAAGGCAGC | ||||

| esvB | GATTTCCAGCGGAGCTTAG | 154 | 55 | A1S_1232, ABAYE2526, ACICU_01218, AB57_1375 |

| CAGGAAATAAACTCTCCCC | ||||

| Phage terminase gene | GTCACGGCCAACACCAC | 588 | 60 | AB57_1270, ACICU_02185 |

| GCACGATTGAAGCAAGGG | ||||

| mel (macrolide efflux gene) | GGTCTTGTGGGTGATAACGG | 253 | 60 | EF102240, EU294228 |

| CTTGTTGGGAAAATGCGG | ||||

| YeeA-OXA-23 | GACAGATGAAGAGCGTCTA | 1,365 | 55 | HQ700358, GQ268326, AB57_0554 to AB57_0551 |

| ATGGAAATGCGGTCAGAAATG | ||||

| Transposition helper protein C-fragmented area | GCAAGTGATCCTGAAGCCA | 388 or 3,238 | 60 | HQ700358 or AB0057, CP001182c |

| CTCAGAATTTTCAGCGCGTC |

The last two primer pairs are from sequences in an AbaR4-type island found in representatives of OXA-23 clone 1, with a deletion relative to AB0057 in the sequence between the primers in the last primer pair. Previously described primer pairs are included in Materials and Methods, and a list of primer sequences is provided in the supplemental material (Table S1).

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) number.

Nucleotides 592806 to 596043.

PCRs were carried out in 25-μl reaction volumes with 1× PCR buffer (Qiagen) containing 1.5 mM MgCl2, deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs; 200 μM each), Taq DNA polymerase (1.5 U), 10 pmol of each primer, and 2 μl of bacterial extract, prepared by suspending a loopful of growth in 100 μl tissue culture water, followed by vortexing and centrifugation; the supernatant was used. An annealing temperature of 55°C or 60°C was used, as appropriate for the primer pairs included; combinations of up to 4 primer pairs were used in multiplex PCRs, with single PCRs also being carried out where there was any ambiguity. Thermocycler conditions were as follows: 94°C for 3 min followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 90 s and then a final extension at 72°C for 10 min (for 60°C-annealing-temperature reactions) or 94°C for 3 min followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 45 s, 55°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 60 s and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min (for 55°C-annealing-temperature reactions).

Detection of orfX and uspA was carried out in single PCRs with annealing temperatures of 50°C and 52°C, respectively. Appropriate positive controls were included in all assays. The following combinations of targets were particularly useful in our study: comM, phage terminase gene, and AB57_0094; comM, aphA1, and ACICU_00080; AbaR-comM, ISPpu12 (RIG), and ABAYE3807; AB57_0094, blaTEM, and phage terminase gene; and aphA1 and ACICU_00080 (all with an annealing temperature of 60°C); cusS and copper resistance D gene (55°C annealing temperature).

Sequencing of the insert in the comM gene of representatives of OXA-23 clone 1 (AB210 [14] and isolates 13 and 15) was performed by a combination of conventional sequencing and use of contigs generated by 454 GS FLX pyrosequencing of AB210 (provided by M. Hornsey, N. Woodford, and A. Underwood). Conventional sequencing was undertaken using primers RH791, RH916, and RH928 (21; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material) and additional primers designed from the beginning and/or end of the contigs and from successive rounds of chromosome walking. A yeeA-blaOXA-23 fragment found in this island and a further fragment from the island with a 2.85-kb deletion relative to AB0057 were sought in blaOXA-23-positive isolates using primers described in Table 1.

RESULTS

The 70 isolates in the study included 38 isolates of the international clone II lineage, which fell into 12 PFGE clusters, with distinct VNTR types within these clusters; the isolates were from 4 countries (see Table S2 in the supplemental material; isolates 1 to 37 and AB210); selected results for blaOXA-23-positive isolates are given in Table 2. All failed to produce a comM amplicon, indicating the presence of an AbaR island insertion, and were PCR positive for the AbaR-comM junction, confirming the presence of an AbaR-type island. As with other representatives of international clone II, regions amplified by the RIC (transposon), RIA (arsenate resistance operon), RID (topA), and RIE (includes mercury resistance operon) primer pairs were not detected. Only one isolate was PCR positive for ISPpu12 (sought using the RIG primer pair). All isolates tested were PCR positive for IS26, thought to be responsible for deletions and insertions in these islands, and most gave an amplicon for the uspA gene, encoding a universal stress protein, indicating that at least one copy of this gene is not interrupted by a multiple-antibiotic resistance region (MARR), as in AbaR1, AbaR3, AbaR5, AbaR6, and AbaR7, found in representatives of international clone I (21).

Table 2.

Results of seeking selected accessory elements by PCR in blaOXA-23-like-positive isolatesg

| Isolate | Hospitala | Date (wk/yr) | PFGE | VNTR | comMb | AbaR-comM | RIA | yeeA-blaOXA-23c | Transposition helper protein C-fragmented areac | mel | TEM | aphA1 | orfX | Phage terminase | ACICU_80 | AB57_94 | cusS | Copper resistance D | int1 | Clonal lineage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C (L) | 45/2009 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 13, 19 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 2 | C (L) | 6/2010 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 13, 19 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 3 | C (L) | 20/2010 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 13, 19 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 4 | C (L) | 20/2010 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 13, 19 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 5 | C (L) | 20/2010 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 13, 19 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 6 | C (L) | 21/2010 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 13, 19 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | II |

| 7 | C (L) | 25/2010 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 13, 19 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 8 | C (L) | 26/2010 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 13, 19 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 9 | C (L) | 26/2010 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 13, 19 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 10 | B (SE) | 47/2009 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 8, 20 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 11 | D (L) | 13/2010 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 8, 20 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 12 | NIR | 45/2006 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 9, 19 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 13 | F (SE) | 44/2009 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 9, 21 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 14 | F (SE) | 14/2010 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 10, 20 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 15d | A (SE) | 2003 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 11, 19 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 16 | D (L) | 23/2008 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 11, 19 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | II |

| AB210 | D (L) | 12/2005 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 11, 19 | − | + | − | + | AB210 (388 bp) | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 17 | H (L) | 21/2009 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 12, 10 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 18 | I (NW) | 6/2010 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 12, 20 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 19 | J (NE) | 26/2010 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 13, 19 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 20 | D (L) | 13/2010 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 13, 21 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 21 | K (L) | 51/2009 | OXA-23 clone 1 | 14, 19 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 22 | Q (M) | 45/2009 | QAC-19 | 17, 20 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | − | − | + | 2 | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 23 | P (SE) | 5/2010 | PAC-1 | 16, 20 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 25 | Q (M) | 37/2009 | Southeast clone | 12, 19 | − | + | − | − | As AB210 | − | + | + | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 26 | K (L) | 51/2009 | Southeast clone | 19, 21 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | + | 2 | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 27 | T (L) | 16/2004 | Southeast clone | 27, 21 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | − | + | + | 2 | − | + | − | − | − | + | II |

| 30 | AU | 2007 | Australia 2 | 30, 20 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | II |

| 34 | PA | 2009 | AB-1 | 11, 26 | − | + | − | − | As AB210 | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | II |

| 36 | Q (M) | 22/2010 | QAC-9 | 15, 17 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | II |

| 38 | N (SE) | 45/2003 | OXA-23 clone 2 | 12, 10 | − | + | + | + | Full size | − | + | + | 1 | + | − | + | + | + | + | I |

| 39d | W (SE) | 22/2004 | OXA-23 clone 2 | 25, 10 | − | + | + | + | Full size | − | + | + | 1 | + | − | + | + | + | + | I |

| 40f | USA | 15/2005 | OXA-23 clone 2 | 23, 10 | − | + | + | + | Full size | − | + | + | 1 | + | − | + | + | + | + | I |

| 41f | CA | 2007 | OXA-23 clone 2 | 22, 9 | − | + | + | + | Full size | − | + | + | 1 | + | − | − | + | + | + | I |

| 42 | AU | 2007 | Australia 1 | 24, 10 | − | + | + | + | Full size | − | + | + | 1 | + | − | − | + | + | + | I |

| 43 | L (M) | 48/2007 | Burns Unit strain | 22, 9 | − | + | + | + | Full size | − | + | + | 1 | − | − | + | + | + | + | I |

| 44 | X (M) | 47/2007 | Burns Unit strain | 22, 9 | − | + | + | + | Full size | − | + | + | 1 | − | − | + | + | + | + | I |

| 45 | Q (M) | 22/2008 | Burns Unit strain | 22, 10 | − | + | + | + | Full size | − | + | + | 1 | − | − | + | + | + | + | I |

| 46 | R (SE) | 8/2006 | Burns Unit strain | 29, 26 | − | + | − | + | Full size | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | I |

| 48 | O (SE) | 42/2007 | Burns Unit strain | 23, 9 | − | + | + | + | Full size | − | − | + | 1 | − | − | − | + | + | + | I |

| 50 | PA | 2009 | AB-2 | 27, 9 | − | + | + | + | Full size | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | I |

| 52 | Q (M) | 14/2009 | QAC-16 | 17, 11 | − | + | − | + | Full size | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | I |

| 53 | C (L) | 20/2010 | CAC-9 | –, 25e | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | I |

| 54 | C (L) | 21/2010 | CAC-9 | –, 25 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | I |

| 55 | Q (M) | 21/2010 | QAC-24 | 21, 11 | − | + | − | + | Full size | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | I |

| 56 | Q (M) | 23/2010 | QAC-24 | 20, 11 | − | + | − | + | Full size | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | I |

| 60 | C (L) | 22/2010 | CAC-10 | –, 26 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| 61 | C (L) | 21/2010 | CAC-10 | –, 26 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| 62 | C (L) | 7/2010 | Unique | 16, 24 | − | + | − | + | As AB210 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| 64 | O (SE) | 25/2010 | Unique | 6, 26 | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 68f | Q (M) | 49/2010 | Strain A | 10, 19 | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| 69f | AB (S) | 49/2010 | Strain A | 10, 19 | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | − |

A to Z and AB were hospitals in mainland United Kingdom; regions (in parentheses) were as follows: L, London; S, South; SE, South-East; M, Midlands; NE, North-East; NW, North-West (all in England). NIR, AU, PA, USA, and CA were hospitals in Northern Ireland, Australia, Pakistan, the United States, and Canada, respectively.

Lack of an amplicon for the comM target indicates the presence of an AbaR insert in this gene.

Elements in an AbaR4-type island in AB210; there is a deletion in the transposition helper C-fragmented area region of 2.85 kb relative to AB0057 (full size).

Isolates 15 and 39 are deposited in the NCTC collection as NCTC 13424 and 13421, respectively.

A dash in the profile indicates that no amplicon was obtained at that locus.

Associated with returning military casualties.

Isolates 38 to 41, 43 to 45, 48, and 50 have a further island, detected by lack of an amplicon with RIK primers, in addition to that in the comM gene.

In agreement with this, sequencing of the comM insert in representatives of OXA-23 clone 1 revealed an AbaR4-type island (GenBank accession number HQ700358) containing sequence corresponding to nucleotides (nt) 582394 to 599202 of AB0057 (GenBank accession number CP001182), with a section (corresponding to nt 593071 to 595920) missing; the uspA gene is uninterrupted. In common with AbaR4 (GQ268326), it contains blaOXA-23 but appears to have no other resistance determinants, other than the sulfate permease gene, common to all these islands, coding for sulfonamide resistance protein. IS26 was not found in this island. It includes a yeeA-blaOXA-23 fragment, with the two genes in opposite orientations, of 1,365 bp, which we sought in all blaOXA-23-positive isolates; irrespectively of genotype or clonal lineage, almost all contained this element, suggesting that AbaR4-type islands are common among blaOXA-23-positive isolates (Table 2). Amplification of the region of the sequence with a deletion of 2.85 kb relative to AB0057 revealed that this deletion was consistently found among representatives of OXA-23 clone 1 and blaOXA-23-positive representatives of other genotypes belonging to international clone II, while most blaOXA-23-positive representatives of international clone I gave amplicons of a size (∼3.2 kb) consistent with no deletion.

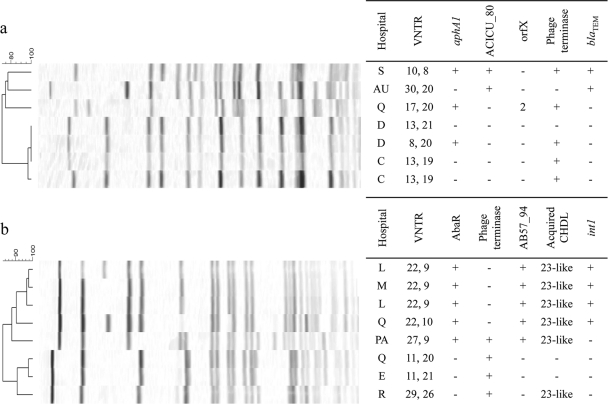

All isolates of international clone II tested were PCR negative for cusS, the copper resistance D gene, and AB57_0094 and ABAYE3807 genes and PCR positive for esvB. The presence of ACICU_00080, aphA1, blaTEM, the phage terminase gene, orfX, mel, int1, and acquired OXA carbapenemase genes was variable. The combination of these genes found among representatives of OXA-23 clone 1 during an outbreak in hospital C (Table 2; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material, isolates 1 to 9) was consistent, as was their VNTR profile (of 13,19); the only exception was one isolate alone lacking a class 1 integron and mel (isolate 6). Isolates of OXA-23 clone 1 from other hospitals differed in their VNTR profiles, and there was also variation in the presence or absence of aphA1 and the phage terminase gene. Two isolates from hospital D (isolates 11 and 20) with identical PFGE profiles, received at the same time, differed in VNTR profile and by the presence or absence of both these genes (Fig. 1a). A PFGE type that clusters loosely with OXA-23 clone 1, referred to as QAC-19, could readily be distinguished from it by the presence of orfX (2 copies) in the integron (isolate 22); the presence of the aacA4-catB8-aadA1 integron in integrase-positive isolates of OXA-23 clone 1 was confirmed by PCR.

Fig. 1.

Examples of discrimination within PFGE clusters provided by VNTR and accessory gene profiling among isolates of international clone II (a) and international clone I (b). In panel a, isolates from hospitals C and D were representatives of OXA-23 clone 1; those from hospitals S, AU, and Q were designated SAC-1, Australia 2, and QAC-19, respectively. Isolates in panel b from hospitals E, R, L, M, and Q were assigned to the Burns Unit strain. Note that, within each cluster, each VNTR profile was associated with a distinct accessory genome profile (except where they differed by only one repeat unit at the second locus, e.g., 22,9 and 22,10). Isolates were from United Kingdom hospitals C to S and hospitals in Australia (AU) and Pakistan (PA). AB57_94 and ACICU_80 are O-antigen genes, and AbaR is a resistance island inserted in the comM gene; orfX (KEGG number K03830) is in the aacC1-orfX-orfX′-aadA1 integron cassette array and can be present in multiple copies.

Representatives of international clone I, from 7 PFGE clusters, showed perhaps more variation, with the presence or absence of an AbaR insert, ISPpu12, blaTEM, aphA1, orfX, the phage terminase gene, AB57_0094, int1, and acquired OXA genes being variable among these isolates (see Table S2 in the supplemental material, isolates 38 to 56). Some representatives of one cluster (“Burns Unit” strain) differed by the presence or absence of all of the following: AbaR island, phage terminase gene, AB57_0094, class 1 integron, and blaOXA-23-like; distinct accessory gene profiles were associated with each VNTR type, despite the limited number of genes investigated (Fig. 1b; Table 2; see Table S2, isolates 43 to 48). In most cases, AbaR regions amplified by the RIA, RID, RIE, and RIG primer pairs were detected; these isolates were often also PCR positive for blaTEM and aphA1, not detected in isolates within the same PFGE cluster lacking an AbaR insert. However, some strains (QAC-16, QAC-24, and CAC-9) were PCR negative for all these elements, with the exception of aphA1 in isolates of QAC-16 (with or without an AbaR island). In contrast to the findings with representatives of international clone II, all isolates of international clone I tested were PCR positive for cusS; most were also PCR positive for the copper resistance D gene. We found ABAYE3807 only in the AYE strain (used as a positive control) and an isolate of international clone III (isolate 59, Spanish clone 1) and, perhaps not surprisingly, did not find ACICU_00080 in any of the international clone I isolates.

The remaining isolates (isolates 57 to 69) included three representatives of international clone III; two strains found in more than one patient not belonging to international clone I, II, or III; and six sporadic strains. Most, but not all, lacked an AbaR island and class 1 integrase gene; 9/13 were PCR positive for cusS, associated with international clone I. IS26 was detected in all isolates with AbaR inserts tested, with the exception of two (isolates 50 and 63), but in only some (4/10) isolates without AbaR inserts. There was variation in the presence or absence of a class 1 integron, blaOXA-40-like, and AYE3807 among the three representatives of international clone III.

All the isolates in our set were PCR positive for esvB, with the exception of one sporadic isolate. ACICU_2140 and A1S_0057 were not detected in any of 23 panel isolates tested, while filA and ACICU_1787 were detected in 14/15 and 20/21 isolates, respectively; since detection of these provided little additional discrimination, they were not sought in the remainder of the isolates. A second genomic island, found at a distinct insertion site from comM, indicated by the lack of an amplicon with the RIK primers (due to island insertion), was present in 9/19 isolates of international clone I tested but not in representatives of international clone II (0/38) or III (0/3) or in sporadic isolates (0/6). Notably, all representatives of OXA-23 clone 2 tested had inserts both in comM and at the RIK site, indicating the presence of two islands, consistent with the presence of an AbaR4-type island containing blaOXA-23, in addition to one containing the regions detected with the RIA, RID, RIE, and RIG primers, as in AB0057. The representative of the Burns Unit strain (isolate 47) that was PCR negative for blaOXA-23-like lacked inserts at both sites, but most representatives had inserts at both; one isolate (isolate 46) appears to have only an AbaR4-type island, in the comM gene (Table 2), as is the case with representatives of OXA-23 clone 1.

DISCUSSION

The population structure of A. baumannii in hospitals is dominated by international clones I and II; isolates with core genomes corresponding to these lineages have predominated for decades (7, 15, 28). However, the accessory genome is much more fluid, and differences between otherwise closely related isolates could quite readily be detected using this approach, despite the relatively limited number of elements sought. Differences in accessory gene profiles correlated with distinct VNTR profiles within a PFGE cluster, supporting VNTR data in describing distinct populations of highly similar organisms. Recognition of these distinct populations should facilitate more accurate identification of possible transmissions between patients and spread between hospitals and improve our understanding of transmission patterns. For example, it is unlikely that the two representatives of OXA-23 clone 1 from hospital D (isolates 11 and 20) in Fig. 1a are epidemiologically linked, since they have distinct VNTR profiles and accessory gene combinations, despite having identical PFGE profiles. In contrast, those from hospital C (isolates 6 and 7) have a common VNTR profile (of 13,19) and share the same accessory genome profile, consistent with an epidemiological link; the four isolates were indistinguishable by PFGE and were all received from London hospitals during early 2010, highlighting the value of this “finer typing” in local investigations.

Extensive differences were observed between some isolates within a cluster, such as the possession or otherwise of an AbaR island, likely to be of considerable size, in representatives of the Burns Unit strain and QAC-16, also accompanied by at least one other difference in accessory gene profile. In support of these observations, Adams et al. (2) similarly found variability in resistance genes associated with insertion sequences, plasmids, and the AbaR chromosomal resistance gene island among closely related clinical isolates of A. baumannii. Some of the differences between isolates were of a more general nature, such as the association of cusS with representatives of international clone I (and III) but not with those of international clone II.

The finding of the yeeA-blaOXA-23 combination of genes (in opposite orientations) in multiple genotypes of blaOXA-23-like-positive isolates, including among some from different countries, is interesting and suggests that most have the same AbaR4-type island, although there was variation in whether the 2.85-kb deletion was present. This is in agreement with findings from an Australian study of the same resistance elements among polyclonal isolates (30). The AbaR4-type island may be present as a second island, in a different insertion site from that of comM, as is the case for AB0057 (1).

It is notable that these elements were not detected in representatives of strain A (isolates 68 and 69), received from military casualties during late 2010, which has affected multiple patients (at least 38) but does not belong to international clone I, II, or III; it has novel ompA and blaOXA-51-like alleles (alleles 3-1 and 13, respectively), used in a sequence-based typing scheme for this organism (28) (http://www.hpa-bioinformatics.org.uk/AB/home.php) and failed to give amplicons at the third (csuE) locus, despite five different primer sets being tried, suggesting that it is significantly different from other outbreak strains of this organism.

Another approach that has been used to provide high-resolution typing involves identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) following whole-genome sequencing (18). While this technology is becoming more accessible and promises to provide discrimination at the highest level possible, it is not currently feasible for many laboratories.

Accessory genome profiles also provide information that may be clinically relevant, particularly in terms of resistance genes, virulence factors, and antigenic properties. Care should, however, be taken not to put too much emphasis on possession or otherwise of a particular gene, when other genes may fulfill a similar role; they are also best not considered in isolation. Information from a large number of isolates can readily be obtained using a PCR approach, extending current information about this organism beyond that based on a relatively small number of sequenced isolates. It is important that information about accessory genes is combined with that provided by other typing methods, so that the genetic context of each isolate is taken into account.

This study involved seeking a substantial number of targets by PCR to characterize isolates. While many were sought in a multiplex format, a more efficient approach, such as a microarray, could streamline this work and facilitate more-detailed characterization. Exploiting information gained from whole-genome studies to extend characterization of isolates to include more elements of the accessory genome is an exciting development that promises to extend our knowledge of this organism and, in combination with other typing methods, help inform epidemiological studies.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to colleagues in United Kingdom hospitals for sending isolates to us and to Seema Irfan, Laurent Poirel, Jon Iredell, Cristina Valderry, Oren Zimhony, Michael Mulvey, and Paul Scott for the isolates from Pakistan, France, Australia, Spain, Israel, Canada, and the United States. We thank Michael Hornsey, Neil Woodford, and Anthony Underwood for providing DNA sequences of contigs generated by 454 genome sequencing relevant to the AbaR island in OXA-23 clone 1 isolate AB210.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jcm.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 2 February 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adams M. D., et al. 2008. Comparative genome sequence analysis of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Bacteriol. 190:8053–8064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adams M. D., Chan E. R., Molyneaux N. D., Bonomo R. A. 2010. Genomewide analysis of divergence of antibiotic resistance determinants in closely related isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3569–3577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coelho J. M., et al. 2006. Occurrence of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clones at multiple hospitals in London and Southeast England. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:3623–3627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Daly M., Villa L., Pezzella C., Fanning S., Carattoli A. 2005. Comparison of multidrug resistance gene regions between two geographically unrelated Salmonella serotypes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55:558–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Da Silva G. J., et al. 2004. Long-term dissemination of an OXA-40 carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter baumannii clone in the Iberian Peninsula. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54:255–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Da Silva G., Dijkshoorn L., van der Reijden T., van Strijen B., Duarte A. 2007. Identification of widespread, closely related Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in Portugal as a subgroup of European clone II. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13:190–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Diancourt L., Passet V., Nemec A., Dijkshoorn L., Brisse S. 2010. The population structure of Acinetobacter baumannii: expanding multiresistant clones from an ancestral susceptible genetic pool. PLoS One 5:e10034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dijkshoorn L., Nemec A., Seifert H. 2007. An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:939–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Di Popolo A., Giannouli M., Triassi M., Brisse S., Zarrilli R. 2011. Molecular epidemiological investigation of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strains in four Mediterranean countries with a multilocus sequence typing scheme. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17:197–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Donnarumma F., et al. 2010. Molecular characterization of Acinetobacter isolates collected in intensive care units of six hospitals in Florence, Italy, during a 3-year surveillance program: a population structure analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:1297–1304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fournier P. E., et al. 2006. Comparative genomics of multidrug resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS Genet. 2:e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Frana T. S., Carlson S. A., Griffith R. W. 2001. Relative distribution and conservation of genes encoding aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes in Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium phage type DT104. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:445–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fu Y., et al. 2010. Wide dissemination of OXA-23-producing carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clonal complex 22 in multiple cities of China. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:644–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hornsey M., et al. 2010. AdeABC-mediated efflux and tigecycline MICs for epidemic clones of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:1589–1593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huys G., Cnockaert M., Nemec A., Swings J. 2005. Sequence-based typing of adeB as a potential tool to identify intraspecific groups among clinical strains of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:5327–5331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Iacono M., et al. 2008. Whole-genome pyrosequencing of an epidemic multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strain belonging to the European clone II group. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2616–2625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Krizova L., Nemec A. 2010. A 63 kb genomic resistance island found in a multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolate of European clone I from 1977. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:1915–1918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lewis T., et al. 2010. High-throughput whole-genome sequencing to dissect the epidemiology of Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from a hospital outbreak. J. Hosp. Infect. 75:37–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mendes R. E., Bell J. M., Turnidge J. D., Castanheira M., Jones R. N. 2009. Emergence and widespread dissemination of OXA-23, -24/40 and -58 carbapenemases among Acinetobacter spp. in Asia-Pacific nations: report from the SENTRY surveillance program. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63:55–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Post V., Hall R. M. 2009. AbaR5, a large multiple-antibiotic resistance region found in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2667–2671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Post V., White P. A., Hall R. M. 2010. Evolution of AbaR-type genomic resistance islands in multiply antibiotic-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:1162–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Quinteira S., Grosso F., Ramos H., Peixe L. 2007. Molecular epidemiology of imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter haemolyticus and Acinetobacter baumannii isolates carrying plasmid-mediated OXA-40 from a Portuguese hospital. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3465–3466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ruiz M., Marti S., Fernandez-Cuenca F., Pascual A., Vila J. 2007. High prevalence of carbapenem-hydrolysing oxacillinases in epidemiologically related and unrelated Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates in Spain. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13:1192–1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tsakris A., et al. 2008. Clusters of imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clones producing different carbapenemases in an intensive care unit. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14:588–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Turton J. F., et al. 2005. Detection and typing of integrons in epidemic strains of Acinetobacter baumannii found in the United Kingdom. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:3074–3082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Turton J. F., et al. 2006. Identification of Acinetobacter baumannii by detection of the blaOXA-51-like carbapenemase gene intrinsic to this species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:2974–2976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Turton J. F., et al. 2006. Comparison of Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from the United Kingdom and the United States that were associated with repatriated casualties of the Iraq conflict. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:2630–2634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Turton J. F., Gabriel S. N., Valderrey C., Kaufmann M. E., Pitt T. L. 2007. Use of sequence-based typing and multiplex PCR to identify clonal lineages of outbreak strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13:807–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Turton J. F., Matos J., Kaufmann M. E., Pitt T. L. 2009. Variable number tandem repeat loci providing discrimination within widespread genotypes of Acinetobacter baumannii. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 28:499–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Valenzuela J. K., et al. 2007. Horizontal gene transfer in a polyclonal outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:453–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Woodford N., et al. 2006. Multiplex PCR for genes encoding prevalent OXA carbapenemases in Acinetobacter spp. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 27:351–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zarrilli R., Giannouli M., Tomasone F., Triassi M., Tsakris A. 2009. Carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii: the molecular epidemic features of an emerging problem in health care facilities. J. Infect. Dev. Countries 3:335–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.