Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the hypoallergenicity of an extensively hydrolysed (EH) casein formula supplemented with Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG).

Design

A prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial.

Setting

Two study sites in Italy and The Netherlands.

Study participants

Children with documented cow's milk allergy were eligible for inclusion in this trial.

Interventions

After a 7-day period of strict avoidance of cow's milk protein and other suspected food allergens, participants were tested with an EH casein formula with demonstrated hypoallergenicity (control, EHF) and a formula of the same composition with LGG added at 108 colony-forming units per gram powder (EHF-LGG) in randomised order in a double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC). After absence of adverse reactions in the DBPCFC, an open challenge was performed with EHF-LGG, followed by a 7-day home feeding period with the same formula.

Main outcome measure

Clinical assessment of any adverse reactions to ingestion of study formulae during the DBPCFC.

Results

For all participants with confirmed cow's milk allergy (n=31), the DBPCFC and open challenge were classified as negative.

Conclusion

The EH casein formula supplemented with LGG is hypoallergenic and can be recommended for infants and children allergic to cow's milk who require an alternative to formulae containing intact cow's milk protein.

Trial registration number

http://ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01181297.

Keywords: Cow's milk protein, cow's milk allergy, extensively hydrolysed formula, double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge, hypoallergenic formula, infant, Lactobacillus GG

Article summary

Article focus

Hypoallergenic extensively hydrolysed (EH) cow's milk-based or amino acid-based formulae are recommended for management of cow's milk allergy in formula-fed infants.

Although Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) has over 25 years of safe use as a dietary probiotic, the safety and hypoallergenic status of EH casein formula supplemented with LGG has not yet been demonstrated.

Key messages

Supplementing the EH casein formula with LGG to provide additional benefits does not change its hypoallergenic status.

The LGG-supplemented EH formula can be safely used for management of cow's milk allergy in infants and children.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Testing the LGG-supplemented EH formula in a properly designed double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge in accordance with accepted European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) and American Academy of Pediatrics standards to establish hypoallergenicity is a major strength of this study.

One limitation is the potentially low novelty of our finding. Because LGG is the most used dietary probiotic, accumulated safety data for LGG as a stand-alone dietary supplement in infants and adults are available.

Introduction

Breast milk is the gold standard for infant nutrition and is recommended for most infants.1 2 A cow's milk-based infant formula is most commonly used if a breast milk substitute is needed during the first year of life.1 However, allergy to cow's milk protein affects 2.2–2.8% of all infants.3 4 Diagnostic confirmation of cow's milk allergy (CMA) is based on clinical history, physical exam and controlled elimination of cow's milk protein followed by challenge procedures, including double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC).5 Quantification of specific IgE to cow's milk is used to diagnose IgE-mediated CMA and may eliminate the need to perform a DBPCFC for confirmation.5 6 A child may be considered allergic to cow's milk with no need for DBPCFC confirmation if the specific IgE concentration by CAP RAST is greater than or equal to the 95% positive predictive value as established in earlier studies (5 and 15 kUA/l for children ≤1 year of age and >1 year of age, respectively).6 7 Management of CMA is based on complete avoidance of intact cow's milk protein. One alternative, soy-based formula, is generally not recommended, particularly for infants younger than 6 months of age with non-IgE-mediated manifestations of CMA, who are more likely to develop concomitant soy allergy.8 9 Thus, formulae with reduced allergenicity, such as those with extensively hydrolysed (EH) protein, are recommended for formula-fed infants with CMA.2 8 10 EH casein formula has a long history of demonstrated efficacy and safety to manage infants and children with CMA.11–13

Determination of β-lactoglobulin (βLG) level, a major cow's milk allergen, is a first assessment of the suitability of a substitute infant formula for infants and children with CMA.14 The minute amount of βLG detected in EH casein formula14 is in the lower range of the amounts detected in breast milk (0.9–150 μg/l).15 According to the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) and the American Academy of Pediatrics, a formula must be tested in a properly designed DBPCFC and can be considered hypoallergenic when demonstrated with 95% confidence that at least 90% of infants and children with confirmed CMA would have no reaction to the formula under double-blind, placebo-controlled conditions.10 14 16 To control for possible false negatives, a negative DBPCFC should be followed by an open challenge (OC) with the tested formula.5 After negative challenges, further assessment of tolerance to the tested formula during a 7-day feeding period to detect potential late-onset reactions is also recommended.10 14

Probiotics are live microorganisms which, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit to the host.17 Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) is the most studied probiotic, with demonstrated benefits when added to an EH formula, including decreased severity of atopic dermatitis (AD),18 19 reduced intestinal inflammation18 20 and faster induction of tolerance21 in infants with CMA and improved recovery from allergic colitis.20 We previously demonstrated that LGG was well tolerated, promoted normal growth and transiently colonised the intestine when added to an EH casein formula fed to healthy term infants.22 23 An EH formula with the same casein hydrolysate and many years of clinical experience of safety use in children with CMA was demonstrated to be hypoallergenic in those children in a DBPCFC trial.13 However, the hypoallergenic status of the EH casein formula with added LGG has not yet been demonstrated. In the current study, we evaluated if LGG addition to this EH casein formula affected its hypoallergenic status for use in management of confirmed CMA in infants and children.

Methods

Study design and participants

A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled prospective crossover trial was conducted at two study sites to assess the hypoallergenicity of an EH casein formula with the same formulation of a previously existing formula (Nutramigen®; Mead Johnson & Company, Evansville, Indiana, USA; control, EHF) that differed only in supplementation with LGG at 108 colony-forming units per gram of powder (EHF-LGG). Each powdered formula provided 2.8 g protein/100 kcal. The LGG raw material used in the formula demonstrated absence of βLG, as determined by an ELISA test with a detection limit of 0.1 μg/g (data on file).

Infants and children ≤14 years of age with confirmed CMA were eligible for this study if their allergic manifestations were under sufficient control, so that a positive response to a food challenge would be recognisable. In addition, participants should have successfully consumed the control formula within 1 week of study enrolment. Exclusion criteria were presence of systemic disease or illness that could compromise participation in the study, use of β-blockers within 12 h of DBPCFC, use of short-acting, medium-acting or long-acting antihistamines more than once within 3, 7 or 21 days of DBPCFC, respectively, or oral steroids within 21 days of DBPCFC. Adverse events were recorded throughout the study.

Confirmation of CMA

Confirmation of CMA required one of the following criteria: (1) a positive DBPCFC to cow's milk or cow's milk-based formula within 6 months of study enrolment; (2) a positive confirmatory value of CAP RAST (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) to cow's milk within 6 months of study enrolment (≥5 kUA/l in participants ≤1 year of age or ≥15 kUA/l in participants >1 year of age); (3) a documented significant adverse reaction to inadvertent ingestion of cow's milk or cow's milk-based formula within 6 months of enrolment plus a positive DBPCFC or a confirmatory CAP RAST value to cow's milk within 12 months of enrolment or (4) a physician-documented anaphylaxis to cow's milk or cow's milk-based formula within 6 months of study enrolment plus a confirmatory CAP RAST value to cow's milk within 12 months of enrolment.

DBPCFC and OC

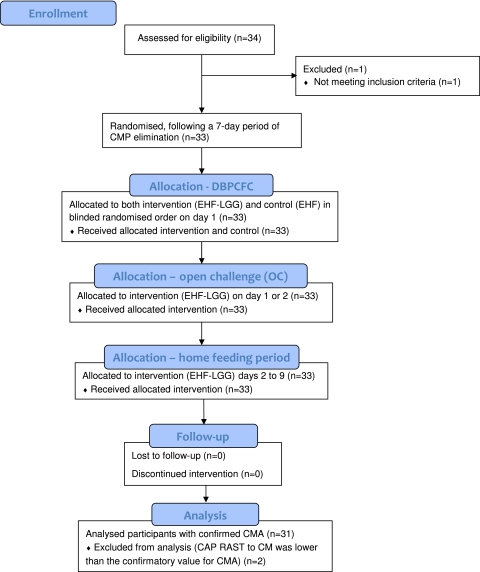

The hypoallergenicity of the EHF-LGG formula was evaluated in a DBPCFC and OC, as described previously.24 A 7-day period of strict elimination of cow's milk protein and other suspected food allergens preceded the DBPCFC (figure 1). On study day 1 prior to the beginning of the DBPCFC and OC, participants underwent a physical examination and medical history and status of allergic diseases was recorded. Participants were either asymptomatic or allergic manifestations had been stabilised for a minimum of 7 days prior to the DBPCFC. The study sponsor had issued a list of 6-digit participant numbers to each study site and the study coordinator sequentially assigned a participant number to each participant. The sponsor also created a separate computer-generated randomisation list of participant numbers that indicated the order in which each study formula should be offered in the DBPCFC challenge. At both study sites, the participant number was provided to a third-party pharmacist who referenced the number against the randomisation list in order to prepare the EHF and EHF-LGG formulae in the assigned randomised order for each participant.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC), open challenge (OC) and home feeding period (EHF, control formula; EHF-LGG, intervention; CM, cow's milk; CMP, cow's milk protein; CMA, cow's milk allergy).

In the DBPCFC, the EHF and EHF-LGG formulae fed in randomised order were administered in an initial 5–10 ml aliquot followed by gradually increasing volumes over a maximum period of 120 min to provide a cumulative volume of 150 ml. A minimum interval of approximately 120 min between the end of the challenge with the first formula separated the beginning of the challenge with the second formula. Times of consumption and amounts of study formula consumed during each challenge were recorded. Any signs or symptoms present before (baseline), during, or after the DBPCFC and OC were recorded using a scoring system to rate severity. The skin was observed for rash, urticaria/angioedema, or pruritus, with the percentage of body area affected recorded. The upper respiratory system was assessed for sneezing/itching, nasal congestion, rhinorrhoea, or laryngeal symptoms, and the lower respiratory system was assessed for wheezing. The gastrointestinal system was evaluated for subjective symptoms such as nausea and abdominal pain and objective symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhoea. Any changes in signs or symptoms from baseline would have resulted in classifying the challenge as positive and discontinuing the participant from the study. If the DBPCFC was negative, an OC with 150–250 ml of the EHF-LGG followed.

Home feeding period

To assess long-term tolerance and reveal any false-negative results to the challenges, all participants with negative responses to both the DBPCFC and OC consumed a minimum of 240 ml of EHF-LGG formula/day during a 7-day home feeding period. Participants' parents recorded in a daily diary volume of formula consumed: presence and severity of vomiting, diarrhoea, rash, runny nose, wheezing or any other symptoms (rated as mild, moderate or excessive); number of bowel movements and overall formula acceptance and tolerance (rated as satisfactory or unsatisfactory). The investigator completed a final evaluation at the end of the 7-day home feeding period.

Sample size determination

In a study with a binomial outcome (reaction versus no reaction), the sample size can be determined by calculating a binomial CI for p, the probability of having a reaction, as demonstrated previously.13 In the case of 0 observed reactions, the upper 95% CI for p is <0.10 when the sample size is 29 participants. Thus studying at least 29 participants and having none classified as positive in the DBPBFC allows the conclusion that the study provided 95% confidence that at least 90% of children with confirmed CMA who ingest the tested formula would have no reaction.10 16 Data were prepared using SAS® V.8.

Ethics approval

The research protocol and informed consent were approved by the Medical Ethics Committees of the The Food Allergy Referral Centre, Department of Pediatrics, Veneto Region, Università degli Studi di Padova, Padova, Italy and the Wilhelmina Children's Hospital, University Medical Centre, Utrecht, The Netherlands. The study complied with good clinical practice guidelines and the 1996 version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Of the 34 children enrolled in the study between April 2003 and February 2004, a total of 33 (males, 19; females, 14) completed the DBPCFC, OC and 7-day home feeding period (one participant who was enrolled but did not meet inclusion criteria was discontinued from the study) (figure 1). Two participants were excluded from further analyses because CAP RAST to cow's milk was lower than the confirmatory value for CMA. Neither participant experienced allergic reactions to the study formulae. Of the remaining 31 participants, 13 were <1 year, 17 were 1–3 years and 1 was 11 years of age. The primary criterion used to confirm ongoing CMA, values for CAP RAST to cow's milk and symptoms evoked after the most recent inadvertent cow's milk protein intake or DBPCFC are summarised in table 1 for these participants.

Table 1.

Participants with confirmed CMA: primary criterion used to confirm CMA, age at CAP RAST to CM and CAP RAST values and symptoms evoked by the participants' most recent exposure to CMP

| Primary criterion to confirm CMA | Age (years) | CAP RAST to CM (kUA/l) | Symptoms evoked after most recent inadvertent CMP intake or DBPCFC to CMP |

| Positive DBPCFC to CMP within 6 months of study enrolment | 0.7 | 70 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema, rhinorrhoea |

| 0.9 | 12.2 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema | |

| 1.1 | <0.35 | Pruritus, rash | |

| 1.3 | >100 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema | |

| 1.4 | 9.9 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema | |

| 1.6 | 15.7 | Urticaria/angioedema, sneezing/itching, laryngeal oedema | |

| 11.6 | 12.3 | Laryngeal oedema | |

| Confirmatory CAP RAST to CM within 6 months of study enrolment | 0.6 | 7.16 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema, wheezing |

| 0.8 | 17.1 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema | |

| 1.5 | 22.4 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema, sneezing/itching | |

| 1.6 | 34.5 | Pruritus, rash, vomiting | |

| 2.3 | >100 | * | |

| 2.4 | 61.8 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema, vomiting | |

| Adverse reaction to inadvertent CMP intake within 6 months and positive CAP RAST to CM within 12 months of study enrolment | 0.3 | 68.3 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema, nasal congestion, sneezing/itching |

| 0.4 | 6.09 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema, vomiting | |

| 0.5 | 4.59† | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema, nasal congestion, sneezing/itching | |

| 0.6 | 10.5 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema, vomiting | |

| 0.6 | 9.01 | Pruritus, urticaria/angioedema, nasal congestion, sneezing/itching | |

| 0.6 | 57.3 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema, nasal congestion, sneezing/itching, laryngeal oedema | |

| 0.7 | 7.46 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema, nasal congestion, rhinorrhoea, sneezing/itching | |

| 0.7 | 9.05 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema, rhinorrhoea, sneezing/itching | |

| 0.8 | 6.84 | Pruritus, rash, wheezing, vomiting | |

| 1.0 | 29.1 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema | |

| 1.0 | 29.5 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema | |

| 1.1 | 60.8 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema, vomiting | |

| 1.3 | >100 | Urticaria/angioedema, rhinorrhoea, wheezing, diarrhoea, vomiting | |

| 1.4 | 23.9 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema, vomiting | |

| 1.5 | 25.0 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema, vomiting | |

| 1.6 | 30.5 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema, rhinorrhoea, sneezing/itching | |

| Anaphylaxis to CMP within 6 months and positive CAP RAST to CM within 12 months of study enrolment | 0.3 | 8.01 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema, systemic anaphylaxis |

| 0.4 | 5 | Pruritus, rash, urticaria/angioedema, nasal congestion, rhinorrhoea, sneezing/itching, systemic anaphylaxis | |

Participant had a history suggestive of CMA beginning at 6 months of age and ongoing symptoms of atopic dermatitis at enrolment.

Participant had sufficient evidence of CMA (exhibited multiple symptoms upon inadvertent CM intake within 3 months of enrolment) although CAP RAST to CM was slightly <5 kUA/l.

CM, cow's milk; CMA, cow's milk allergy; CMP, cow's milk protein; DBPCFC, double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge.

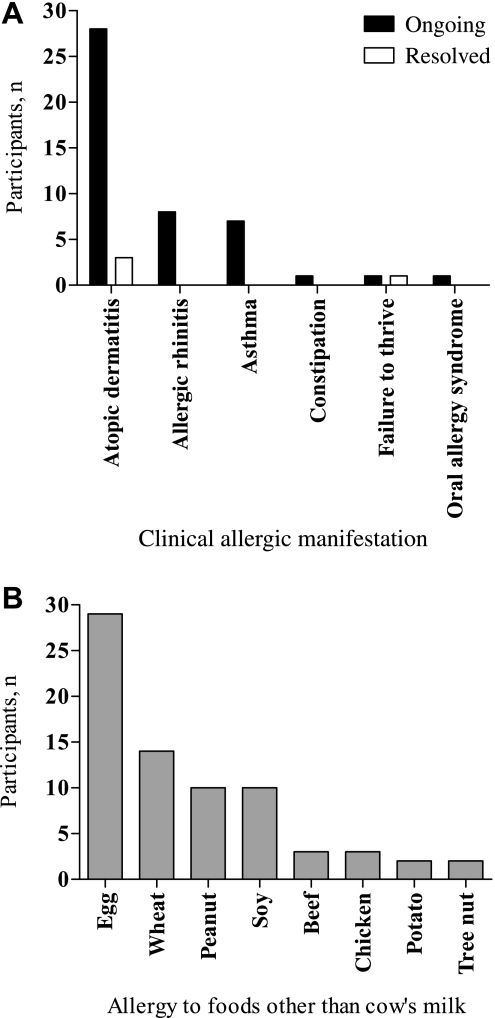

Ongoing allergic diseases including AD, asthma and/or allergic rhinitis were noted in 29 participants at study entry. Two participants reported a history of AD but no active allergic manifestation at study entry. Participants' status of allergic manifestations and presence of food allergies other than CMA at enrolment are shown in figure 2A,B, respectively. Ongoing allergy to multiple foods was reported for 29 participants, with 18 participants having two or more reported food allergies in addition to CMA.

Figure 2.

Medical history of participants with confirmed cow's milk allergy (n=31): (A) ongoing and resolved clinical allergic manifestations at enrolment and (B) number of participants who reported allergy to foods other than cow's milk at enrolment.

After the pre-challenge 7-day period of cow's milk protein elimination, 29 of 31 participants had no allergic symptoms and remained asymptomatic throughout the DBPCFC and OC. Of the two remaining participants, one had no change in the mild rhinorrhoea reported at baseline and one had an improvement in the pruritus and rash reported at baseline. The DBPCFC and OC were thus classified as negative for all participants. Parent-recorded diaries during the home feeding period were returned for 30 participants and indicated that overall acceptance and tolerance of the EHF-LGG formula was generally good. Mean daily intake (mL/day±SD) reported was 546±251 and 522±132 for participants <1 year and 1–3 years of age, respectively, and 561 for the 11-year-old participant. Mean daily stool frequencies (±SD) were 1.9±0.5 and 1.7±0.9 for participants <1 year and 1–3 years of age, respectively, and 1.3 for the 11-year-old. No serious adverse events were reported during the DBPCFC, OC or home feeding period.

Discussion

These findings demonstrate that a hypoallergenic EH casein hydrolysate formula remains hypoallergenic following the addition of LGG, satisfying both ESPHGAN and American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines. In this study, all 31 study participants with confirmed CMA had a previous history of experiencing one or more types of allergic symptoms in the skin, respiratory and/or gastrointestinal systems or had systemic anaphylaxis after ingestion of cow's milk protein, meeting recognised criterion to confirm CMA using a combination of convincing symptoms upon exposure to cow's milk protein and a strongly positive confirmatory value of specific IgE to cow's milk by RAST.6 7 24 In accordance with reports of sensitisation to other food allergens commonly observed in children with CMA,13 24 allergy to one or more foods in addition to cow's milk was reported in 94% of participants in this study. After 7 days of strict cow's milk protein elimination from the diet, 29 of 31 participants had no allergic symptoms and remained asymptomatic throughout the DBPCFC and OC, whereas the other two had mild symptoms that either did not change or improved during the challenges. No serious adverse events were reported during the DBPCFC, OC or the 7-day home feeding period.

The addition of probiotics in formula used for management of CMA requires that they be proven safe and are well tolerated. LGG has over 25 years of safe use25 including administration to preterm infants26 or to infants perinatally who were at high risk of allergy, in whom normal growth was demonstrated up to 2–4 years of age.27 28 To justify use, addition of a probiotic must also be shown to be of benefit. Early gut microbial colonisation is associated with modulation of inflammation and expression of allergy.18 20 29 30 LGG administration to atopic pregnant women followed by postnatal administration to their infants was associated with lower incidence of AD at 2, 4 and 7 years of age compared with placebo.30 Additionally, anti-inflammatory effects of LGG accompanied by amelioration of symptoms were observed in infants experiencing AD as a manifestation of CMA.19 31 In a study using fecal calprotectin as a marker of intestinal inflammation, infants with presumptive allergic colitis were randomised to receive an EH formula with or without LGG and the same casein hydrolysate as the formulae in the current study.20 After a 4-week feeding period, blood in stools, characteristic of allergic colitis, disappeared in all infants in the LGG-supplemented group versus only 63% in the non-supplemented group. The LGG-supplemented group also experienced a larger decrease in fecal calprotectin level. In a recent study, EH casein formula with LGG was demonstrated to accelerate the time of acquisition of tolerance to cow's milk protein in infants with CMA after 6 and 12 months of feeding.21

We previously demonstrated that LGG added to an EH casein formula was well tolerated and transiently colonised the intestinal tract of healthy term infants.22 Growth and other nutrition parameters, including circulating fatty acid levels, were demonstrated to be normal in healthy term infants who received this formula up to 4 months of age.23 Available data suggest that the LGG-supplemented EH casein formula assessed in the current study provides additional benefits of better management of allergic colitis, as well as faster tolerance acquisition, in infants with CMA that are not observed with the non-supplemented formula. We tested the EH casein formula supplemented with LGG according to established criteria and demonstrated that its hypoallergenic status is maintained. Therefore, this formula can be recommended for infants and children with CMA who require an alternative to formulae containing intact cow's milk protein.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank study site staff for their cooperation. The participation of parents and infants in this study is greatly acknowledged.

Footnotes

To cite: Muraro A, Hoekstra MO, Meijer Y, et al. Extensively hydrolysed casein formula supplemented with Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG maintains hypoallergenic status: randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000637. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000637

Contributors: AM, YM and MOH helped design the study, assessed study participants and collected study data, interpreted data and reviewed and revised the manuscript. CL interpreted data and reviewed and revised the manuscript. JLW and DMFS interpreted data and drafted the manuscript. CLH prepared and interpreted data and reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the intellectual content and approved the final version.

Funding: The study was funded by the study sponsor, Mead Johnson Nutrition (study number 3369-2). Mead Johnson Nutrition provided logistical support during the trial. Employees of the sponsor worked with study investigators to prepare the protocol, summarise the collected data and write the manuscript.

Competing interests: AM, MOH and YM have received research support from Mead Johnson Nutrition. CHL is a former employee of Mead Johnson Nutrition. JLW, CLH and DMFS work in the Department of Medical Affairs at Mead Johnson Nutrition.

Patient consent: All participant information was completely anonymised.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from Italy: Tesoriere Azienda Ospedaliera Padova and The Netherlands: Medisch Ethische Toetsingscommissie.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Gartner LM, Morton J, Lawrence RA, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 2005;115:496–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyce JA, Assa'ad A, Burks AW, et al. ; NIAID-Sponsored Expert Panel Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126(6 Suppl):S1–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Höst A, Halken S, Jacobsen HP, et al. Clinical course of cow's milk protein allergy/intolerance and atopic diseases in childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2002;13(Suppl 15):23–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schrander JJ, van den Bogart JP, Forget PP, et al. Cow's milk protein intolerance in infants under 1 year of age: a prospective epidemiological study. Eur J Pediatr 1993;152:640–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bindslev-Jensen C, Ballmer-Weber BK, Bengtsson U, et al. Standardization of food challenges in patients with immediate reactions to foods–position paper from the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. Allergy 2004;59:690–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Ara C, Boyano-Martinez T, Diaz-Pena JM, et al. Specific IgE levels in the diagnosis of immediate hypersensitivity to cows' milk protein in the infant. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;107:185–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sampson HA. Utility of food-specific IgE concentrations in predicting symptomatic food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;107:891–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vandenplas Y, Koletzko S, Isolauri E, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of cow's milk protein allergy in infants. Arch Dis Child 2007;92:902–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatia J, Greer F. Use of soy protein-based formulas in infant feeding. Pediatrics 2008;121:1062–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Committee on Nutrition American Academy of Pediatrics. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics 2000;106:346–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oldæus G, Björkstén B, Einarsson R, et al. Antigenicity and allergenicity of cow milk hydrolysates intended for infant feeding. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 1991;2:156–64 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oldæus G, Bradley CK, Björkstén B, et al. Allergenicity screening of “hypoallergenic” milk-based formulas. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1992;90:133–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sampson HA, Bernhisel-Broadbent J, Yang E, et al. Safety of casein hydrolysate formula in children with cow milk allergy. J Pediatr 1991;118:520–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isolauri E, Sutas Y, Makinen-Kiljunen S, et al. Efficacy and safety of hydrolyzed cow milk and amino acid-derived formulas in infants with cow milk allergy. J Pediatr 1995;127:550–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Host A, Husby S, Hansen LG, et al. Bovine beta-lactoglobulin in human milk from atopic and non-atopic mothers. Relationship to maternal intake of homogenized and unhomogenized milk. Clin Exp Allergy 1990;20:383–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Host A, Koletzko B, Dreborg S, et al. Dietary products used in infants for treatment and prevention of food allergy. Joint statement of the European Society for Paediatric Allergology and Clinical Immunology (ESPACI) Committee on Hypoallergenic Formulas and the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Committee on Nutrition. Arch Dis Child 1999;81:80–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guarner F, Schaafsma GJ. Probiotics. Int J Food Microbiol 1998;39:237–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Isolauri E, Arvola T, Sutas Y, et al. Probiotics in the management of atopic eczema. Clin Exp Allergy 2000;30:1604–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viljanen M, Savilahti E, Haahtela T, et al. Probiotics in the treatment of atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome in infants: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Allergy 2005;60:494–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baldassarre ME, Laforgia N, Fanelli M, et al. Lactobacillus GG improves recovery in infants with blood in the stools and presumptive allergic colitis compared with extensively hydrolyzed formula alone. J Pediatr 2010;156:397–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canani RB, Nocerino R, Terrin G, et al. Effect of extensively hydrolyzed casein formula supplemented with Lactobacillus GG on tolerance acquisition in infants with cow's milk allergy: a randomized trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;129:580–2e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petschow BW, Figueroa R, Harris CL, et al. Effects of feeding an infant formula containing Lactobacillus GG on the colonization of the intestine: a dose-response study in healthy infants. J Clin Gastroenterol 2005;39:786–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scalabrin DM, Johnston WH, Hoffman DR, et al. Growth and tolerance of healthy term infants receiving hydrolyzed infant formulas supplemented with Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG: randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2009;48:734–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burks W, Jones SM, Berseth CL, et al. Hypoallergenicity and effects on growth and tolerance of a new amino acid-based formula with docosahexaenoic acid and arachidonic acid. J Pediatr 2008;153:266–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorbach SL. The discovery of Lactobacillus GG. (Lactobacillus GG). Nutr Today 1996;31:5S [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stansbridge EM, Walker V, Hall MA, et al. Effects of feeding premature infants with Lactobacillus GG on gut fermentation. Arch Dis Child 1993;69:488–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laitinen K, Kalliomaki M, Poussa T, et al. Evaluation of diet and growth in children with and without atopic eczema: follow-up study from birth to 4 years. Br J Nutr 2005;94:565–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rinne M, Kalliomaki M, Salminen S, et al. Probiotic intervention in the first months of life: short-term effects on gastrointestinal symptoms and long-term effects on gut microbiota. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2006;43:200–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pessi T, Sutas Y, Hurme M, et al. Interleukin-10 generation in atopic children following oral Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. Clin Exp Allergy 2000;30:1804–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalliomäki M, Salminen S, Poussa T, et al. Probiotics during the first 7 years of life: a cumulative risk reduction of eczema in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;119:1019–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Majamaa H, Isolauri E. Probiotics: a novel approach in the management of food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1997;99:179–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.