Background: Oxidation and protein misfolding are fundamental to prion diseases.

Results: Oxidation generates a monomeric, helical, and molten globule followed by a β-conformation that lacks a cooperative fold.

Conclusion: Oxidation of the prion protein destabilizes its native fold and shares a common misfolding pathway to amyloid fibers.

Significance: The misfolding may explain the high levels of oxidized methionine in scrapie isolates.

Keywords: Copper, Methionine, NMR, Oxidation-Reduction, Prions, Protein Misfolding, Protein Structure, Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

Abstract

Oxidative stress and misfolding of the prion protein (PrPC) are fundamental to prion diseases. We have therefore probed the effect of oxidation on the structure and stability of PrPC. Urea unfolding studies indicate that H2O2 oxidation reduces the thermodynamic stability of PrPC by as much as 9 kJ/mol. 1H-15N NMR studies indicate methionine oxidation perturbs key hydrophobic residues on one face of helix-C as follows: Met-205, Val-209, and Met-212 together with residues Val-160 and Tyr-156. These hydrophobic residues pack together and form the structured core of the protein, stabilizing its ternary structure. Copper-catalyzed oxidation of PrPC causes a more significant alteration of the structure, generating a monomeric molten globule species that retains its native helical content. Further copper-catalyzed oxidation promotes extended β-strand structures that lack a cooperative fold. This transition from the helical molten globule to β-conformation has striking similarities to a misfolding intermediate generated at low pH. PrP may therefore share a generic misfolding pathway to amyloid fibers, irrespective of the conditions promoting misfolding. Our observations support the hypothesis that oxidation of PrP destabilizes the native fold of PrPC, facilitating the transition to PrPSc. This study gives a structural and thermodynamic explanation for the high levels of oxidized methionine in scrapie isolates.

Introduction

Central to transmissible spongiform encephalopathies is the misfolding of the largely α-helical cellular prion protein (PrPC)3 into an oligomeric infectious scrapie prion protein isoform, PrPSc (1). Prion diseases are also characterized by oxidative stress (2, 3). For example, levels of oxidative stress markers are reported as being significantly increased in the brains of scrapie-infected mice (4, 5) and in the brains of patients suffering from Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (6, 7). In addition, scrapie-infected cells and animals are more sensitive to oxidative stress (8–12).

Early research noted methionine oxidation in PrPSc, although this was dismissed as an artifact caused by isolation of PrPSc from brain homogenates (13). However, more recently Canello et al. (14) have shown that a large fraction of the methionine residues from ex vivo PrPSc brain extracts contains methionine sulfoxides (MetOx), whereas for PrPC, the methionine residues remained unoxidized. The study went on to show that the MetOx formation was not an artifact of PrPSc isolation as believed previously (14). It has yet to be established whether the methionine oxidation is a cause of the cascade of events that leads to PrPC misfolding and the formation of toxic oligomers and amyloid plaques. Hypotheses on the role played by oxidative modification might include the destabilization of PrPC, the promotion PrPSc formation, or the inhibition of PrPSc clearance. Oxidative stress has been observed in early preclinical stages of mouse scrapie (5); therefore, the oxidative process might represent a risk factor in sporadic prion diseases (15). Copper-catalyzed oxidation has been shown to provoke aggregation in the protein (15) and PK resistance (16), both features of prion diseases. It has also been shown that the pathogenic mutant E200K, which is linked to the most common form of familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, may spontaneously undergo oxidation (16). Using analogs of methionine residues, the aggregation propensities of PrPC have been correlated with the degree of methionine oxidation (17). Indeed metal-catalyzed oxidation can generate oligomeric species, 10–40 nm in diameter that correspond to 25–100 PrPC molecules in size (18). Oligomeric and aggregated species may be favored over fiber formation (19), however, formation of amorphous aggregates, fibrils, or oligomers is very dependent on the particular experimental conditions in vitro (20).

Methionine oxidation of PrP in vitro has previously been characterized using mass spectrometry (15, 17, 21, 22). In addition, the effect of Cu2+-catalyzed oxidative damage has been reported for PrP (15, 18, 23). The Fenton and the Haber-Weiss reactions of copper ions, in the presence of a physiological reductant such as ascorbate, is a significant source of protein oxidation in vivo, generating highly reactive and damaging hydroxyl radicals and other reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as H2O2 (25, 26). For PrPC, Cu2+/Cu+ redox reactions in the presence of H2O2 will cause oxidation of both histidine residues to 2-oxo-His and also Met residues within PrPC; however, the oxidant H2O2 will readily cause the oxidation of methionine to methionine sulfoxide while the histidine residues remain unaffected (15, 21, 23, 27). The structures of methionine sulfoxide and 2-oxo-His are shown in supplemental Fig. S1. Copper redox-generated ROS can also mediate β-cleavage of the prion protein main chain, typically at residue-112 (28, 29), and this can seed aggregation (29) and dimerization of PrP (30).

Mammalian prion proteins have a high homology at the sequence and structural level (31–33). Mammalian PrPC consists of two structurally distinct domains (34). The C-terminal domain (residues 126–231) is predominantly helical, containing three α-helices as well as two short anti-parallel β-strands. Most of the nine methionines in PrP (mouse sequence) are in the structured domain, including Met-128, Met-133, Met-137, Met-153, Met-204, Met-205, and Met-212, whereas Met-23 and Met-37 are in the unstructured N-terminal domain. The N-terminal domain (residues 23–120) is highly disordered (35, 36) and is notable for its ability to bind as many as six Cu2+ ions (37–45) in a redox active form (23, 46). The role of redox active metal ions in protein misfolding diseases has recently been reviewed (47).

Critical to understanding the molecular mechanisms involved in amyloid formation is the characteristics of the misfolding pathway and the role of folding intermediates in this process. In vitro, amyloid fibers of PrP can be generated at neutral pH in the presence of denaturants (48). In addition, a soluble oligomeric form of PrP, with extended β-structure has been identified as the so-called β-oligomer, favored at low pH (∼3.5–4.0) with high salt content (48–52). Initial studies suggested that at low pH, PrPC would not generate amyloid fibers (48); however, it is now clear these low pH conditions are also capable of producing fibers (53, 54). Characterization of this species by NMR suggested the N-terminal residues (23–118) are unstructured and highly flexible, whereas the C-terminal residues formed a molten globule or oligomeric species (55). Subsequent studies suggest a transition from a molten globule, monomeric, α-helical species at pH 4.1 to an oligomeric species with β-strand content at pH 3.5 (56, 57). This pH 4 folding intermediate is of particular interest because it is on the pathway to fiber formation under physiologically attainable conditions; nonphysiological denaturants such as urea or guanidine HCl are not required (54). Similarly, the influence of oxidation of side chains from PrPC, on the folding and stability, has physiological relevance; here, we show oxidized PrP misfolding has striking similarities to the folding of PrP at pH 4–3.5. This suggests that PrP might share aspects of a misfolding pathway, even under very different conditions.

We aim to understand how the structure and folding properties of PrPC are perturbed by oxidation of the methionine and histidine residues, produced by hydrogen peroxide and copper-catalyzed oxidation. Using 1H-15N NMR, FT-IR, and UV-CD, we aim to characterize the effects of oxidized Met and His side chains on the main chain conformation of PrPC. We also determine the effect of PrP oxidation on the thermodynamic stability of the native fold of the protein. Here, we show that methionine oxidation of PrPC perturbs the hydrophobic core of the protein that causes a significant loss in its folding stability. Furthermore, Cu2+-catalyzed oxidation generates a monomeric molten globule structure with high helical content; more extensive oxidation generates an unstable structure with extended β-strand-like conformation. These studies represent a thermodynamic and structural rationale for the observation that PrPSc isolates contain predominantly oxidized methionine side chains, and oxidative stress markers are a significant feature of prion diseases.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression and Purification of Recombinant mPrP(23–231) and mPrP(113–231)

The coding region of the full-length mouse PrP(23–231) was cloned into a pET-23 vector to produce a tag-free protein as described previously (55). We also studied the PrP(113–231) fragment because it has been shown that the Cu2+ redox system can cause amide cleavage of PrP at residue 112 (28, 29); thus, PrP(113–231) represents a cleaved fragment of PrPC. PrP(113–231) predominantly contains the structured C-terminal domain of PrP. To generate His-tagged PrP(113–231), codons for amino acid residues 23–112 were deleted by mutation of the sequence to include an NdeI site prior to the codon for residue 113. This fragment retains a methionine residue prior to residue 113 and an N-terminal His tag. The proteins were expressed in 2-liter flasks of Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells in 15N-labeled minimal medium containing (1 g/liter) 15NH4Cl (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc.) as the sole nitrogen source. The proteins (both tag-free full-length PrP or His-tagged PrP(113–231)) were purified using a nickel-charged metal affinity column made from chelating Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences).

Oxidation of PrP Treatment

Ultra high quality water (10−18 megohms−1 cm−1 resistivity) was used throughout. Protein concentrations were determined using an extinction coefficient at 280 nm. This gave an extinction coefficient of 62,280 m−1 cm−1 at 280 nm for full-length mPrP(23–231). The pH was measured before and after acquiring each spectrum.

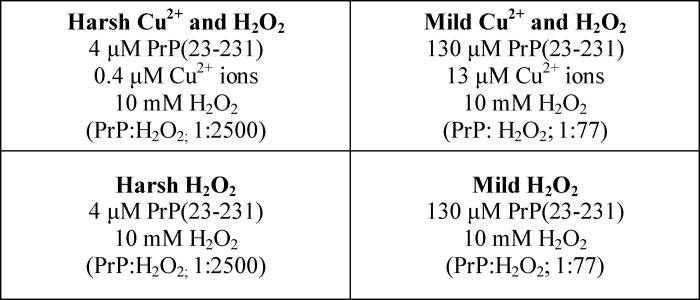

PrP samples were oxidized by incubation with H2O2 or a mixture of H2O2 and Cu2+ ions. Samples were oxidized under four sets of conditions as shown in Table 1. These conditions are designated as follows: H2O2 oxidized both “mild” and “harsh” and also copper-catalyzed oxidation (Cu2+ + H2O2) also mild and harsh. For the mild conditions, relatively concentrated PrPC was used, 130 μm, but only 10 mm H2O2. For the more harshly oxidizing conditions, more dilute PrP was used; 4 μm, with 10 mm H2O2. Thus, the ratio of H2O2 to protein was 30 times higher, causing considerably more oxidation of PrP.

TABLE 1.

Oxidizing conditions

For copper-catalyzed oxidation, 0.1 mol eq of Cu2+ (relative to PrP) was used in all experiments together with the same concentrations of PrP and H2O2 for the mild and harsh conditions. For some biophysical measurements, including CD and ANS binding, samples were oxidized at both PrP concentrations, 130 and 4 μm, for typically 16 h, and then the samples were diluted to 4 μm to record spectra. The details of these oxidizing conditions are summarized in Table 1. After 10 h of incubation, for three-dimensional NMR experiments only, 10 μm catalase (purchased from Sigma) was added to stop further oxidation.

Hydrogen peroxide is highly oxidizing but will not generate hydroxyl radicals. Hydroxyl radicals can be generated by redox cycling of Cu2+ ions by addition of a reducing agent, such as ascorbate, under aerobic conditions. Alternatively, a mixture of H2O2 with Cu2+ ions will also undergo Fenton and Harber-Weiss reactions to generate the highly reactive hydroxyl radical. We used the H2O2 plus Cu2+ conditions to avoid reductants such as ascorbate that will absorb light in the far-UV region and interfere with CD measurements. The ability of this reaction mixture, under these conditions (Table 1), to generate appreciable hydroxyl radicals was confirmed by a hydroxyl radical detection assay (supplemental Fig. S12).

The oxidizing effects of H2O2 (15, 17, 21–23) and copper-catalyzed oxidation (15, 18, 23) is well documented for PrP. In particular, H2O2 principally responsible for Met oxidation and Cu2+ plus H2O2 mixture will oxidize more widely, in particular His residues (see supplemental Fig. S1). We have used NMR to confirm the oxidative effects of H2O2 alone, and H2O2 with Cu2+ mixtures over time with our experimental conditions (see supplemental Fig. S13).

NMR Spectroscopy

NMR spectra were acquired at 37 °C on a Bruker Avance spectrometer operating at 600 or 700 MHz for 1H nuclei using a 5-mm inverse detection triple-resonance z-gradient probe or cryoprobe. Phase-sensitive two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra were acquired using Echo-anti-Echo gradient selection. 1H acquisition parameters were 0.122-s acquisition time, 1-s fixed delay, and 2048 complex (t2) points, and 256 complex points were collected for the 15N dimension. Thirty two transients were recorded for each t1 interval. The 1H and 15N dimensions possessed spectral widths of 14 and 25 ppm, respectively. The 15N dimension was zero-filled to 256 data points before squared cosine apodization and Fourier transformation.

Main chain amide resonance assignments have been reported by us for mouse PrPC (36). Assignments of H2O2-oxidized PrP(113–231) were made using unoxidized assignments as the starting point. Assignments were confirmed using phase-sensitive three-dimensional 1H-15N-HSQC-NOESY (58) and with Echo-anti-Echo gradient selection. The three-dimensional 15N-HSQC-NOESY spectra were obtained using a mixing time of 100 ms, and 2048 complex points were collected in the direct 1H dimension over a spectral width of 12 ppm, 64 complex points; 160 complex points were collected for the indirect 15N and 1H dimensions, respectively, over a 15N spectral width of 25 ppm and a 1H spectral width of 12 ppm. Spectra were zero-filled to 2048 data points in the direct 1H dimension, 128 data points in the indirect 15N dimension, and 512 data points in the indirect 1H dimension.

The extent of the chemical shift perturbations (CSP) in the 1H and 15N NMR chemical shifts of each amide resonance was presented as a standard weighted sum according to Equation 1 (59).

CSP were mapped onto the structure of mouse PrPC (Protein Data Bank code 1XYX) (31, 32) using PyMOL.

Circular Dichroism (CD)

CD spectra were recorded on an Applied Photophysics Chirascan instrument, as described previously (60). The direct CD measurements (θ, in millidegrees) were converted to molar ellipticity, Δϵ (m−1 cm−1), using the relationship Δϵ = θ/33,000·c·length, where c is concentration, and l is path length.

Urea Denaturation Studies

PrP(23–231) samples were incubated at 130 μm under oxidative conditions H2O2 or Cu2+ plus H2O2 for 10 h at 37 °C in 10 mm sodium acetate buffer at pH 5.5. Mild and harsher oxidizing conditions were used to mimic the NMR and CD experiments; 0.1 mol eq of Cu2+ were used and 10 or 300 mm H2O2. Samples were then diluted to 4.3 μm PrP(23–231) for the urea denaturation. Titrations were performed by combining stock PrP solutions, one in 10 m urea or in just water, to avoid any dilution of protein concentration with addition of urea. CD measurements for the urea unfolding studies were recorded at 225 nm along with a measurement at 260 nm to account for any base-line offset. All urea denaturation experiments carried out at 25 °C (after incubation under the oxidizing conditions).

The folding/unfolding transition for PrPC are rapid, within milliseconds (61). In the presence of urea, equilibrium was reached rapidly, as judged by identical repeat CD scans recorded over time.

PrP unfolding was treated as essentially a simple two-stage unfolding, and so the denaturation curves were fitted to a modified Hill equation (Equation 2),

where y is CD signal; a is ymax − ymin; [D] is concentration of urea; [D50%] concentration of urea at the midpoint of the folding transition, and n is the Hill coefficient (62).

The equilibrium constant (K) for unfolding at each urea concentration was calculated from the denaturation curve using Equation 3.

|

The Gibbs free energy of unfolding at a particular urea concentration is then given by ΔG = −RT ln(K). Where R is the gas constant, (8.314 J K−1 mol−1), and T is the temperature, 298 K. A plot of ΔG versus [urea] reveals a linear relationship; extrapolation of the line to where urea is at 0 concentration gives us the free energy of unfolding in the absences of urea (ΔGUH2O), and gradient of the line (m) is a measure of the cooperativity of the folding transition.

The difference in stability of unoxidized PrP(23–231) and oxidized PrP (ΔΔGU[D]50%) is given by Equation 4, using mean value of m (63).

ANS and bis-ANS Fluorescence

PrP samples were incubated with H2O2 and H2O2 with Cu2+ ions under the four different oxidizing conditions described in Table 1. PrP(23–231) samples were then diluted down to 4 μm. Aliquots of ANS and bis-ANS (Sigma) were added to make 8 mol eq of ANS and 4 mol eq of bis-ANS relative to PrP(23–231). Fluorescence emission spectra were obtained using a Hitachi F-2500 fluorescence spectrophotometer in a 1-cm quartz cuvette (Hellma), using an excitation wavelength of 380 nm for ANS and 365 nm for bis-ANS. Fluorescence emission was recorded between 400 and 600 nm.

ANS and the larger bis-ANS are dyes that bind to exposed hydrophobic regions of partially folded proteins such as the molten globule state (64). Partially unfolded molten globule proteins tend to exhibit a significant increase in fluorescence signal, although fully unfolded proteins typically do not exhibit an appreciable increase in fluorescence.

FT-IR

Spectra were obtained using a Bruker IFS 66/s FT-IR spectrometer, as described previously (40). Typically, 5 μl was aliquoted onto the attenuated total reflectance crystal (ZnSe prism) where it was purged with dry nitrogen to generate a protein film.

Size-exclusion Chromatography

The Tricorn Superdex 75 (10/300) and Superdex 200 (10/300) analytical gel filtration chromatography columns (GE Healthcare) were used, with an AKTA-FPLC system (GE Healthcare) at 4 °C. An aqueous buffer of 10 mm sodium acetate with 500 mm NaCl, pH 5.5, was used at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min−1. Sample injection of 0.5 ml, 0.1 mg/ml PrP was used.

RESULTS

Core Hydrophobic Packing within PrPC Is Perturbed by Oxidation of Methionines

As oxidative stress is observed in the early preclinical stage of scrapie infection (5) and a high proportion of methionines within scrapie isolates are oxidized (14), we were interested in the effects of oxidation on the structure and stability of PrPC. We have determined the effect of oxidation over time by monitoring changes in the main chain amide NMR chemical shifts of PrPC by recording 1H-15N HSQC spectra. These amide CSP can be used to monitor changes in structure on a per residue basis.

We used H2O2 to oxidize PrPC, and it has been shown that H2O2 will readily oxidize methionine side chains to sulfoxide, although other amino acid side chains remain unaffected. The effects of H2O2 oxidation for both the C-terminal fragment PrP(113–231) and full-length PrP(23–231) are very similar, as indicated by selected regions of the 1H-15N HSQC spectra shown in Fig. 1a and supplemental Figs. S2 and S3. Under these relatively mild oxidizing conditions (10 mm H2O2 with no Cu2+ ions) the changes in the spectra are largely complete by 9 h; as there is little difference between spectra recorded at 9 h to that recorded at 20 h. Separate sets of signals were observed for the oxidized and unoxidized PrPC. This would be expected as the oxidized PrP is a covalently altered species; rapid exchange between these species does not take place. For those residues that are perturbed by oxidation, the intensity of the unoxidized signals is completely lost in less than 9 h, whereas the new set of signals of the oxidized PrP have a comparable intensity to the unoxidized signals. Furthermore, there is no significant increase in 1H NMR line width between unoxidized and oxidized PrP, and this suggests that the oxidized forms of prion protein are predominantly monomeric. This is in agreement with size-exclusion chromatograph that indicates PrPC oxidized by H2O2 remains monomeric (supplemental Fig. S4). We see from the 1H-15N HSQC that for some of the perturbed amide resonances multiple new resonance are observed for the oxidized form with similar chemical shifts (Fig. 1a and supplemental Fig. S3). These variations in chemical shift must be attributed to variation in the local conformation of side chain packing for these residues. This might be expected as there may be multiple forms of the oxidized PrP with different combinations of the seven methionine residues oxidized, as has been observed by mass spectrometry (21).

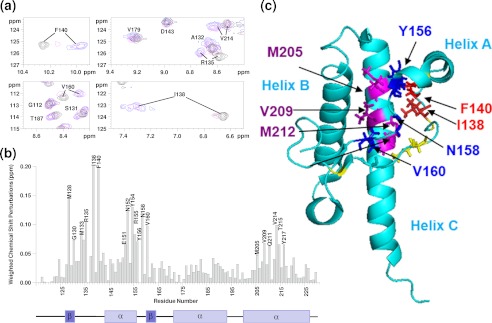

FIGURE 1.

Structural changes upon methionine oxidation of PrP indicated by chemical shift perturbations. a, two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of PrP(113–231) (3.0 mg/ml) in 10 mm acetate buffer, pH 5.6, at 37 °C, showing unoxidized spectra (black) and H2O2 (10 mm)-incubated sample after 3 h (pink) and 9 h (blue) of incubation. b, plot of chemical shift perturbation per residue. Strongly perturbed amide resonances are highlighted along with a representation of the secondary structural regions of PrPC showing the three α-helices (residues 144–156, 172–193, and 200–227) and two short anti-parallel β-strands (128–131 and 161–164). c, structure of mouse PrPC (chemical shift perturbation code 1XYX) with key perturbed side chains shown.

From a total of 110 resolved amide residues, in PrP(113–231), most are only mildly perturbed in terms of the amide main chain 1H-15N chemical shifts (CSP values) as shown in Fig. 1b. Specifically, 86 amino acids have changes in their chemical shift by less than 0.04 ppm. This indicates the basic fold of PrP is unaffected under these conditions. However, there are 24 amide main chain resonances that do have significant changes in their 1H and 15N shifts (>0.04 ppm). As might be expected, these include methionine residues. Perturbations are not restricted to these residues, and indeed, the most perturbed resonances are not from the methionine main chain amides. The amide resonances that show the most significant perturbations are highlighted in Fig. 1b and on the structure of PrPC in Fig. 1c.

Perturbed residues are concentrated at specific regions; in particular, residues in extended region Val-160, Asn-158, and Tyr-156 pack against methionine residues Met-205 and Met-212 together with Val-209 in helix-C (Fig. 1c). It seems clear that these hydrophobic residues (Val-160, Tyr-156, Val-209, Met-205, and Met-212) stabilize the core structure of PrPC and are perturbed upon oxidation of the methionines. A second group of residues that have significant chemical shift perturbations include hydrophobic residues Ile-138 and Phe-140 (Fig. 1c). These residues form close contacts with each other and a methionine residue, Met-137. In addition, residues in Asn-152 and Tyr-154 in helix-A on either side of another methionine, Met-153, have some chemical shift perturbations, as do residues Gly-130, Met-128, and Met-133, which are adjacent to Val-160 and Asn-158 and form part of a short anti-parallel β-sheet within PrPC.

Oxidation of methionine to methionine sulfoxide causes an increase in the size and hydrophilicity of the side chain, which can trigger changes in secondary structure (65). Consequently, upon oxidation, the change in methionine side chain will cause rearrangements of the hydrophobic packing of neighboring side chains. As is clear from Fig. 1c, residues that are in close contact with the oxidized methionine side chains have their conformation perturbed; this in turn perturbs the environment of the main chain amides. We note that oxidation of the ϵS at the end of the methionine side chain will not necessarily significantly perturb the amide resonance from the same methionine, as in the case of the solvent-exposed Met-153. The oxidation of Met-205 and Met-212 in the hydrophobic core of PrPC appears to be a key methionine perturbing the structure. The NMR data suggests that although Met-205 and Met-212 are substantially buried in the structure, H2O2 will readily oxidize these residues.

We have carried out the same treatment on full-length PrP and the same oxidation occurs, as the same set of new resonances for the oxidation of PrP appears in the two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectrum (see supplemental Fig. 2). This indicates that H2O2 oxidation affects the structured domain of PrP similarly in full-length PrPC, and the unstructured N-terminal domain does not significantly influence the H2O2-induced oxidation in the structured domain.

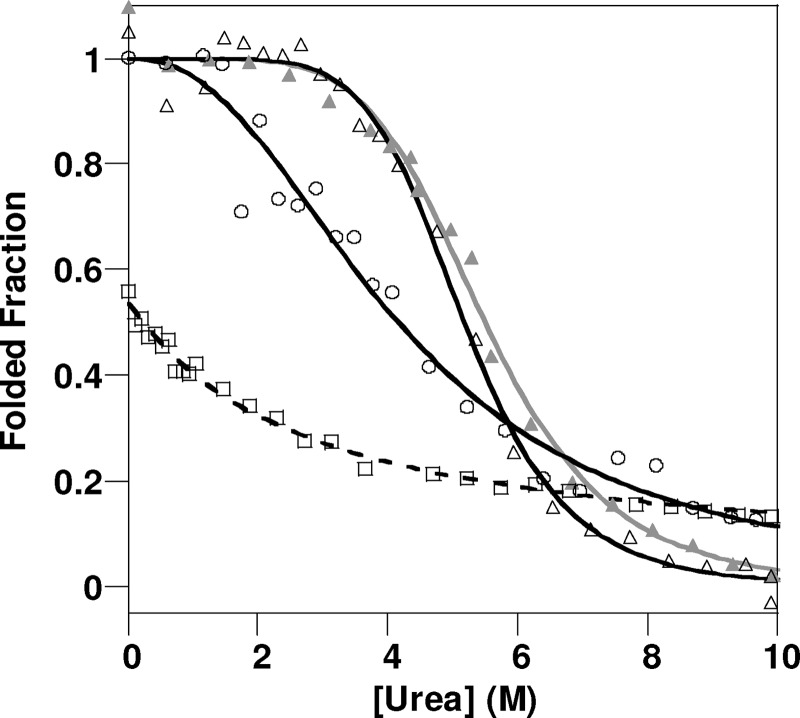

Methionine Oxidation of PrPC Destabilizes the Native Fold of PrPC

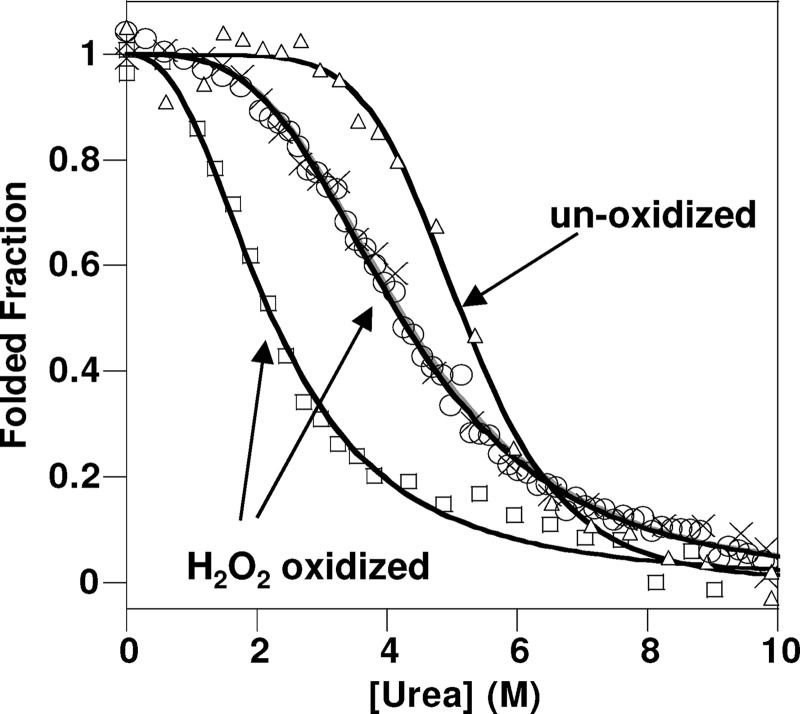

It is clear from the two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC data presented in Fig. 1 that the hydrophobic core of PrPC is perturbed by methionine oxidation but the fold of PrPC remains intact. Next, we wanted to determine whether the oxidation of PrPC has thermodynamically destabilized its native fold. Urea denaturation folding curves were generated for PrP(23–231) under various oxidizing conditions and were compared with unoxidized PrP(23–231). PrP exhibits a rapid unfolding and was treated as essentially a two-step process. The CD signal at 225 nm was used to monitor PrPC folding over a range of urea concentrations (Fig. 2). The urea concentration at the mid-point of unfolding, [D]50%, for PrP(23–231) is 5.2 (± 0.1) m at pH 5.5.

FIGURE 2.

Urea unfolding of H2O2-oxidized PrP(23–231). CD data at 225 nm with increasing [urea] for unoxidized PrP(23–231) (triangles), H2O2-oxidized PrP(23–231) under mild condition (circles), repeat measurements (crosses), and H2O2-oxidized PrP(23–231) under harsher conditions (squares) are shown. All PrP samples (130 μm) were incubated with 10 or 300 mm H2O2 for 8 h before urea titration. The protein concentration was diluted to 4.3 μm, pH 5.5, using 10 mm sodium acetate buffer.

PrP(23–231) was oxidized by incubation with H2O2 under two sets of conditions (see “Experimental Procedures” and Table 1) as follows: mild conditions, similar to those used for the NMR experiments, and harsher conditions with higher ratio of H2O2 to PrP. PrP samples were incubated for 10 h under the H2O2-oxidizing conditions prior to urea unfolding studies. Under both sets of conditions, oxidation of PrPC caused significant destabilizing of the native fold of PrPC. The mid-point of misfolding, [D]50%, drops from 5.2 m urea in unoxidized PrPC to 4.2 (±0.1) m urea for H2O2-oxidized PrP. The oxidation generated under the harsher conditions causes significantly more destabilization of the native fold of PrPC (Fig. 2). H2O2 oxidization reduced [D]50% from 5.2 to 2.2 (±0.1) m urea.

The thermodynamic parameters of folding stability are summarized in Table 2. The difference in the free energy of unfolding at the mid-point of the folding transition between oxidized and unoxidized, ΔΔGU50%, is 2.7 kJ/mol when the sample undergoes oxidation by H2O2 using the same condition used to obtain the NMR data. Higher ratios of H2O2 to PrPC cause even more destabilization and increase the difference in free energy of unfolding to ΔΔGU50% = 8.9 (± 0.6) kJ/mol.

TABLE 2.

Urea unfolding stabilities

The mean 〈m〉 value = 3.1 ± 0.3 kJ/mol/m.

| PrPC | [D]50% | ΔGUH2O | m | ΔΔGUH2O | ΔΔGU[D]50%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | kJ/mol | kJ/mol/m | kJ/mol | kJ/mol | |

| Un-oxidized | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 16.7 ± 0.4 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | ||

| Un-oxidized, 0.1 mol eq Cu2+ | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 17.1 ± 1.5 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | ||

| H2O2-oxidized, mild condition | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 9.4 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 7.3 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.4 |

| H2O2 + Cu2+-oxidized, mild condition | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 6.9 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 9.8 ± 0.6 | 3.0 ± 0.6 |

| H2O2-oxidized, harsh condition | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 7.8 ± 0.4 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 8.9 ± 0.6 | 8.9 ± 0.4 |

| H2O2 + Cu2+- oxidized, harsh condition | ∼0a |

a This harsh oxidizing condition causes a loss of a cooperative fold.

The transition between folded and unfolded is less defined for the more mild oxidizing conditions (Fig. 2). This is reflected in the folding cooperativity value (m), which is 3.1 kJ/mol/m for native PrPC and 2.3 kJ/mol/m for H2O2 oxidized PrP. This might reflect a mixture of oxidized species for the mildly oxidizing conditions. At higher ratios of H2O2 to PrP, the cooperativity of unfolding is quite similar for unoxidized and oxidized PrP, 3.1 and 3.4 (± 0.2) kJ/mol/m, respectively. It is clear that the oxidation of the methionine residues significantly destabilizes the native fold, and the extent of destabilization increases with oxidation.

Like unoxidized PrPC, urea unfolding of oxidized PrP is reversible as shown in supplemental Fig. S5. We also investigated the thermal unfolding of oxidized compared with unoxidized PrP. Again oxidation destabilizes the PrP fold; however, thermal unfolding is not reversible, and these data have not been analyzed any further.

Cu2+-catalyzed Oxidation Destabilizes PrPC and Generates a Monomeric Molten Globule Conformation

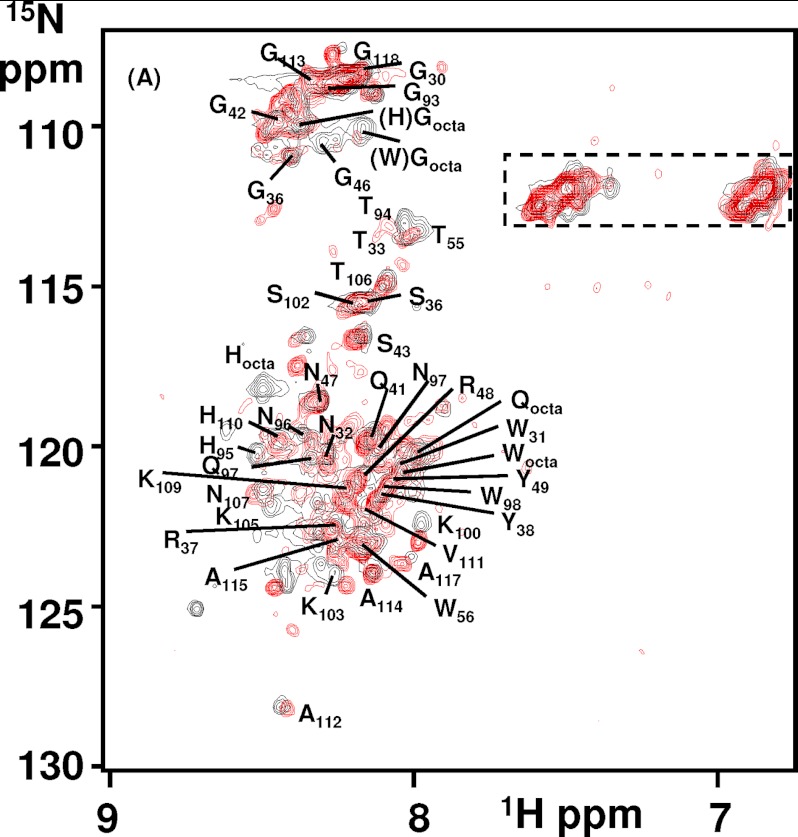

Cu2+ binds to PrPC in vivo (37), and copper redox cycling is a key source of ROS; generating hydroxyl radicals that will oxidize PrPC more widely than H2O2 alone (15, 23). Next, we aimed to investigate the effects of Cu2+-catalyzed oxidation of PrPC using NMR spectroscopy. First, we confirmed any changes in the two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra were not simply due to the paramagnetic line-broadening effect of the Cu2+ ions. Comparison of the two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of PrP(23–231) with and without 0.1 mol eq Cu2+ ions showed little difference in the amide signals (supplemental Fig. S6). This level of Cu2+ was sufficiently low to not broaden the amide signals directly. Upon addition of H2O2 (at pH 5.5) to PrP(23–231) with Cu2+ present (0.1 mol eq), there is a significant change in the appearance of the two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra. Two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra were recorded every hour for 32 h, as PrPC underwent copper-catalyzed oxidation. In marked contrast to H2O2 oxidation alone within 4 h, a third of the amide signals were lost (Fig. 3b). Typically, amide signals that were lost were from residues within the structured region of PrPC. Interestingly, a number of residues from helix-C specifically (Thr-200, Met-205, Arg-207, Gln-211, Gln-222, Ala-223, and Gly-227) retain their chemical shift values, 1H line width, and their intensity, whereas most signals from helix-A and -B are lost (Fig. 3b and supplemental Fig. S7). These changes suggest that the topology of the PrP fold is to some degree retained during copper-catalyzed oxidation under these conditions. After 16 h, approximately a third (∼65) of the amide signals are still retained (Fig. 3c), and these signals have little chemical shift dispersion and are assigned to the unfolded N-terminal domain of PrP, residues 23–118.

FIGURE 3.

Copper-catalyzed oxidation of PrP(23–231). a, unoxidized; b, after 4 h of Cu2+ + H2O2 oxidized; c, 16 h after copper-catalyzed oxidation. After 4 h some resonances from helix-C retain their signal and chemical shift values (labeled in black), although many other signals from the structured domain lose their signal intensity (labeled in gray) due to exchange broadening of a molten globule fold. After 16 h only signals from the N-terminal residues (23–122) were observed. 130 μm PrP(23–231) was used with 0.1 mol eq of Cu2+ ions with 10 mm H2O2 in 10 mm sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.6.

The loss of NMR intensity for two-thirds of the amide signals can be attributed to considerable line-broadening. The increase in line width can be due to the formation of a high molecular weight oligomeric species; alternatively, the formation of a molten globule fold can cause significant line-broadening of NMR signals due to slow milli-microsecond conformational exchange dynamics of the main chain. We note that paramagnetic broadening by the Cu2+ ions has been ruled out (supplemental Fig. S6).

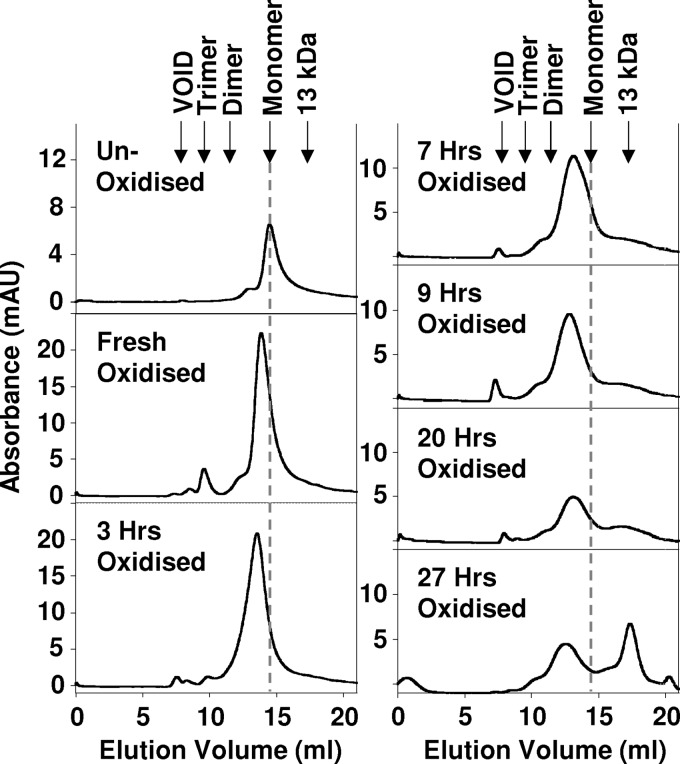

We used size-exclusion chromatography to establish if the Cu2+-catalyzed oxidation of PrP generated an oligomeric or a monomeric molten globule species. Copper-catalyzed oxidation of PrP(23–231) was monitored over time by recording a chromatogram every 90 min (Fig. 4). Unoxidized PrP gave a single main elution band with a retention volume appropriate for monomeric PrP(23–321). Incubation of PrP with Cu2+ and H2O2 also generated a single elution band but with a slightly faster retention time. This band indicates a molecular size only slightly larger than a monomer but not large enough to be a dimer. The retention volume suggests a partially unfolded monomer of PrP after copper-catalyzed oxidation. We note that molten globule proteins elute from size-exclusion columns slightly faster than their molecular mass would indicate because they are less compact. A very minor additional band (less than 5% total protein) was also observed, assigned to tetrameric PrP oligomers. After 3 h of incubation with Cu2+ and H2O2, a very small band eluted in the void volume indicating the presence of a larger oligomer. After 9 h of oxidation, the intensity of the elution bands indicates that most of the PrP present is still detected eluting from the column as a monomer. Even after 20 h of incubation, the main band eluting from the column is monomeric. It is only at 27 h of incubation that we observe fragmentation of PrP with an elution band at ∼13 kDa. It is well documented that copper-catalyzed oxidation can cause peptide cleavage at reside 113 of PrP to generate a 13- and 10-kDa fragment (28, 29).

FIGURE 4.

Size-exclusion chromatogram of Cu2+-catalyzed oxidation of PrP(23–231). A series of chromatograms showing the change in Cu2+-catalyzed oxidation of PrP(23–231) under the milder conditions, from unoxidized and freshly oxidized to 27 h of incubation at 37 °C. All were carried out using a Superdex-75 column. The incubation was carried out using 130 μm PrP(23–231) with 0.1 mol eq of Cu2+ ions and 10 mm H2O2 in 10 mm sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.5.

Size-exclusion chromatography suggests that the broadening in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra is due to the formation of a monomeric molten globule rather than oligomerization of PrP. This is supported by the NMR data, as a number of peaks from the structured portion of PrPC that do not have any additional flexibility remain intense, and their line widths are unaffected. In particular, six residues from helix-C that exhibit the largest line width in native PrPC (36) retain their intensity, line width, and native chemical shift values, indicating that a large oligomeric species, with the associated increased line width, has not been formed.

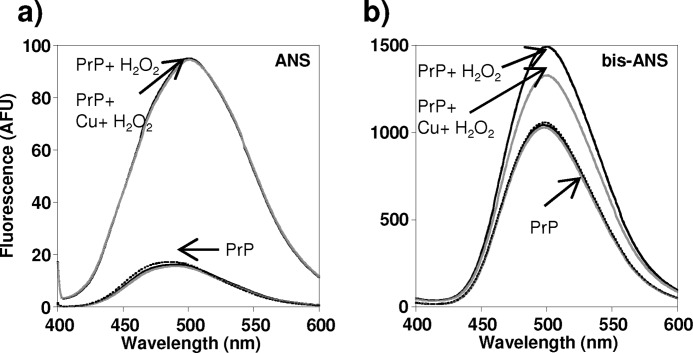

Next, we used ANS and bis-ANS binding to probe the nature of the Cu2+-catalyzed oxidized species under the mild oxidizing conditions used for the NMR experiments (see Table 1 and under “Experimental Procedures”). These molecules have been shown to have significant fluorescence when exposed to hydrophobic residues in the partially folded protein and have been widely used to characterize molten globule conformations. Fig. 5 shows that both that ANS and bis-ANS have a marked increase in fluorescence for the Cu2+-oxidized species, with a 4-fold increase in fluorescence upon ANS binding. We note that native PrPC is known to generate some fluorescence when bound to ANS and bis-ANS; this is due to the exposed hydrophobic nature in its native conformation (66).

FIGURE 5.

ANS (a) and bis-ANS (b) fluorescence for oxidized H2O2 and copper-oxidized PrP. 130 μm PrP(23–231) was oxidized by incubation with 10 mm H2O2 (black line) or with 10 mm H2O2 plus 0.1 mol eq Cu2+ ions (gray line). Samples were incubated for 22 h at 37 °C, before being diluted to 4 μm for fluorescence assay. Unoxidized PrP(23–231) is also shown. Under this relatively mild oxidizing condition, both H2O2 and copper-catalyzed oxidations caused increased fluorescence relative to unoxidized PrP(23–231) for both ANS and bis-ANS binding suggesting a molten globule folding intermediate had formed.

The ANS and bis-ANS fluorescence observed supports the NMR data (Fig. 3) that suggest a molten globule has been generated. Interestingly, mildly oxidized PrP generated with H2O2 only, where the hydrophobic core is destabilized, also yields a strong increase in ANS and bis-ANS fluorescence. This suggests that the H2O2-oxidized PrP also has some molten globule-like properties. The HSQC data (Fig. 1) indicate the hydrophobic core of PrPC is disrupted under these conditions, although the amide signals do not exhibit exchange-broadening motions often observed for molten globule proteins.

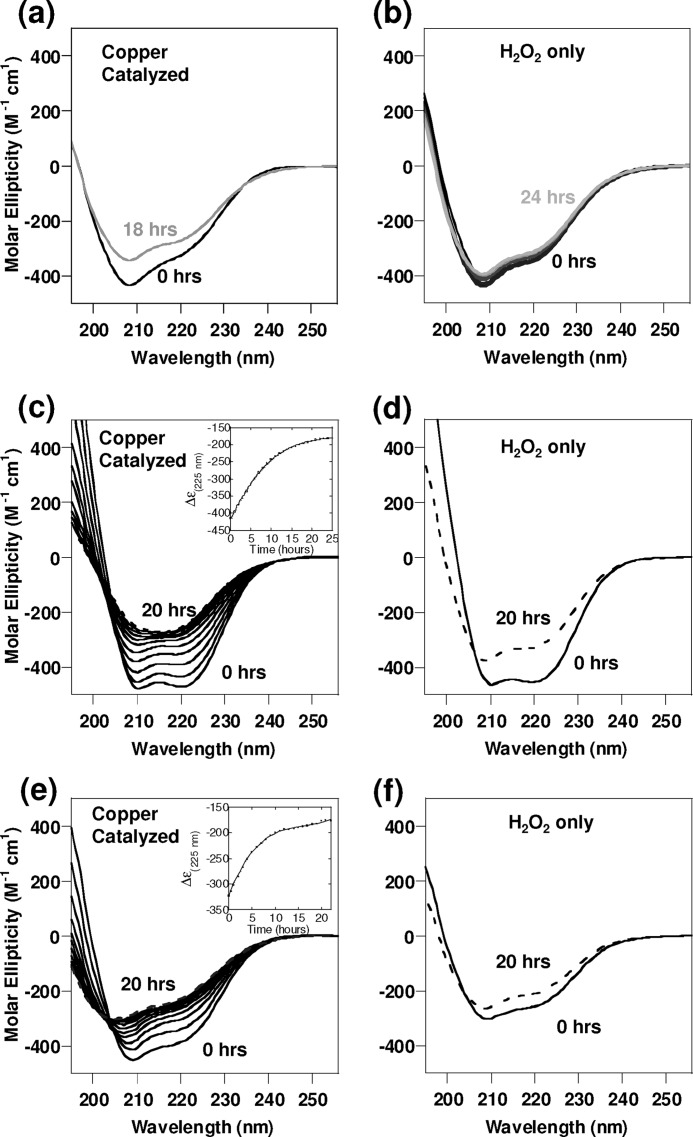

Further support for the generation of a less compact molten globule fold is derived from UV-CD spectra of PrP(23–231) oxidized under the same mild copper-catalyzed conditions. It is clear from the CD spectra (Fig. 6a), there is almost no change in secondary structure after 4 h of oxidation even though the 1H-15N HSQC spectra (Fig. 3, b and c) exhibits profound changes in appearance. Substantial helical content was retained even after 18 h of incubation, suggesting a molten globule had formed in which the basic helical topology remained unchanged but in a less compact form.

FIGURE 6.

UV-CD of oxidation of PrP. Structural transitions monitored by UV-CD of full-length and a fragment of PrP when incubated with H2O2, with and without the presence of Cu2+ ions. a, PrP(23–231) (130 μm) incubated with H2O2 (10 mm) and Cu2+ (0.1 mol eq); b, PrP(23–231) (130 mm) incubated with H2O2 (10 mm) only; c, PrP(113–231) (4 μm) and Cu2+ (0.1 mol eq) incubated with H2O2 (10 mm), spectra at 2-h time intervals; d, PrP(113–231) (4 μm) incubated with H2O2 (10 mm) only; e, PrP(23–231) (4 μm) and Cu2+ (0.1 mol eq) incubated with H2O2 (10 mm), spectra at 2-h time intervals, are shown. f, PrP(23–231) (4 μm) incubated with H2O2 (10 mm) only. All spectra recorded at pH 5.5 at 37 °C and diluted to 4 μm PrP.

Next, we studied the thermodynamic folding stability of PrP after undergoing copper-catalyzed oxidation by monitoring unfolding in the presence of urea (Fig. 7). Relatively mild Cu2+-catalyzed oxidation (which generates a helical molten globule) causes destabilization of PrPC. In particular, the urea mid-point of unfolding is reduced from 5.2 ± 0.1 to 4.2 ± 0.4 m urea. This equates to a difference in the free energy of unfolding of ΔΔG50% 3.0 ± 0.6 kJ/mol (Table 2).

FIGURE 7.

Urea unfolding of Cu2+-catalyzed oxidized PrP(23–231). CD data at 225 nm with increasing [urea] of unoxidized PrP(23–231) (triangles), PrP(23–231) with 0.1 mol eq of Cu2+ (filled triangles), Cu2+-catalyzed oxidized PrP(23–231) under the mild conditions (circles), and Cu2+-catalyzed oxidized PrP(23–231) under harsher conditions (squares) are shown. All PrP samples (130 μm) were incubated with 0.1 mol eq Cu2+ and 10 or 300 mm H2O2 for 8 h before urea titration. The protein concentration was diluted to 4.3 μm, pH 5.5, using 10 mm sodium acetate buffer.

Further Cu2+-catalyzed Oxidation Promotes Extended β-Strand-like Conformations in PrPC with Little Stability

It is clear that under the relatively mild oxidizing conditions used for the NMR experiments (used for data in Figs. 1 and 3), there are quite profound perturbations in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra and reduced stability of the native fold. However, there is very little change in total secondary structure, as indicated by CD spectra for both the H2O2-oxidized and copper-catalyzed oxidation (Fig. 6, a and b, and supplemental Fig. 8).

Next, we wanted to probe the structure of PrP under harsher oxidizing conditions (see Table 1 and see under “Experimental Procedures”)) using FT-IR and UV-CD. We incubated PrPC in the presence of H2O2 or a mixture of H2O2 and Cu2+ ions and recorded UV-CD spectra every 2 h. Fig. 6 shows the effect of oxidation on both the C-terminal structured domain, PrP(113–231) (Fig. 6, c and d), and the full-length PrP(23–231) (Fig. 6, e and f). With harsher oxidizing conditions over 10 h of incubation, Cu2+ with H2O2 will cause a loss of the α-helix signal, as indicated by a loss in intensity of bands at 222, 208, and 190 nm and an increase in extended β-strand structure, as indicated by the appearance of a minimum at 217 nm. Fig. 6, c and e, insets, shows the change in the helical CD signal at 225 nm over time. Most of the changes occur in the first 10 h of incubation, and after this there is little change in the spectra.

Under these harsher copper-catalyzed oxidizing conditions, there is a large reduction in the CD signal at 225 nm even in the absence of urea, and indeed, the CD spectra are more indicative of β-sheet. The urea unfolding curve is shown in Fig. 7. The CD signal has been monitored at 225 nm, and both α-helical and β-sheet secondary structure will produce significant CD signals at this wavelength. It is clear from the appearance of the urea unfolding curve (Fig. 7) that this form of the protein with the extended β-strand conformation has very little stability, and addition of very small amounts of urea (0.1 m) immediately causes further loss in the fold, suggesting the apparent structure formed under these conditions does not possess a cooperative fold. For this reason a [D]50% value was not determined.

We note that CD spectra may not readily distinguish between regular stable β-sheets and extended main chain conformation that may not have formed a regular hydrogen-bonding network. The urea unfolding measurement indicates that the extended β-strand like conformation indicated by CD was too unstable to be from highly ordered β-sheets, typically found in amyloids.

Incubation with H2O2 alone under harsher conditions also causes a loss of α-helical signal, although less β-sheet-like CD signal was generated, as the negative band at 217 nm is less apparent (Fig. 6, d and f). Urea unfolding measurements under these conditions show substantially reduced stability, but they still reveal that the corporative fold is maintained (Fig. 7). To confirm the changes in the CD were due to oxidation of PrP, unoxidized PrPC shows no change in the UV-CD spectra when recorded over a 20-h period. Similarly, addition of small substoichiometric amounts of Cu2+ ions (0.1 mol eq) to PrPC (in the absence of H2O2) causes no change in the CD spectrum as recorded over a 20-h period (supplemental Fig. S9).

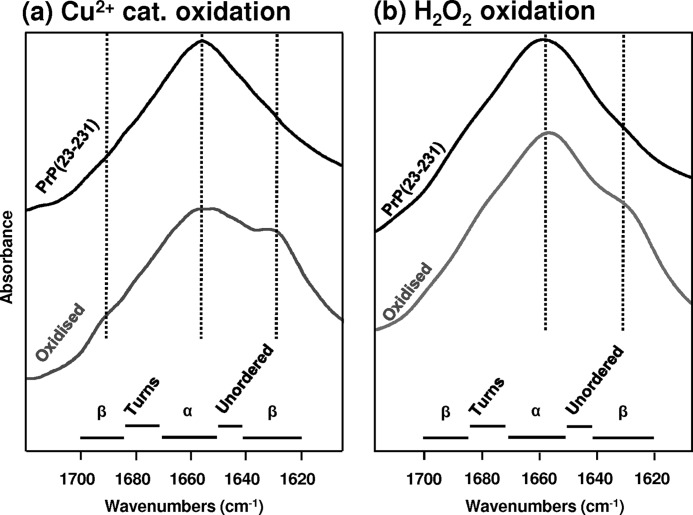

We considered the possibility that the reduction of the helical signal in the CD spectrum was simply due to some precipitation of PrP and consequently to a loss of signal. However, UV absorption spectra recorded after 20 h indicates some light scattering due to aggregation but only a relatively small reduction in the absorption band at 280 nm. FT-IR has the advantage that interpretations of secondary structural proportions are not so influenced by a loss of signal due to precipitation. The FT-IR data (Fig. 8) confirms that there is gain in β-sheet content for PrP(23–231) incubated with Cu2+ and H2O2 and also to a lesser extent by H2O2 oxidation alone. In particular, Fig. 8a shows the FT-IR spectra of Cu2+-catalyzed oxidation of PrP(23–231) compared with unoxidized PrPC. The frequency of the amide-I band is very diagnostic of secondary structure. The band at 1650 cm−1 is typical of a protein rich in α-helical content and some irregular structure as would be expected for PrP(23–231). After incubation (using the same harsh oxidizing conditions as the CD experiments, see Table 1) with H2O2 plus Cu2+ for 20 h, a significant shoulder on the amide-I band appeared at 1630 cm−1, and this is characteristic of β-sheet formation. Fig. 8b shows the effect of oxidation of PrP(23–231) by H2O2 only. After oxidation, a slight shoulder appears at ∼1630 cm−1 indicative of β-strand conformation. Cu2+ ions were also incubated with PrPC in the absence of H2O2 to confirm the effects were not due to Cu2+ binding to PrP alone (supplemental Fig. S9b). It appears that oxidation of PrPC under these harsher conditions will causes a loss in α-helical content and an increase in extended β-strand character, particularly for the Cu2+-catalyzed oxidation.

FIGURE 8.

FT-IR spectra of full-length PrPC oxidized. a, copper-catalyzed; b, H2O2 only. Amide-I band of unoxidized PrP(23–231) (black line) and oxidized PrP(23–231) (gray line). Oxidized PrP was generated by incubating for 20 h under conditions described in Fig. 6, e and f. The oxidized PrP(23–231) contains an amide-I band at 1630 cm−1 diagnostic of an increase in β-sheet content, particularly apparent for the Cu2+-catalyzed oxidized PrP.

We also investigated ANS and bis-ANS fluorescence binding using these more harshly oxidizing conditions. These data are shown and discussed in supplemental Fig. S10. For these more harshly oxidized species, a molten globule is not suggested as ANS and bis-ANS fluorescence are similar to native unoxidized PrPC.

Protease K (PK) resistance is a hallmark of scrapie PrP. We have therefore performed a PK digest of PrP(23–231), with H2O2 oxidized under the harsh conditions. Interestingly, the oxidized PrP is clearly protease-resistant, and an ∼16-kDa fragment was observed, although unoxidized PrP generates much smaller fragments after treatment with protease K. This is shown in supplemental Fig. S11.

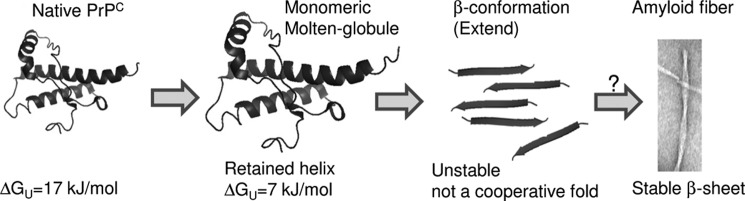

Copper-catalyzed Oxidation of PrP to Molten Globules Has Clear Similarities with the Low pH Folding Intermediates

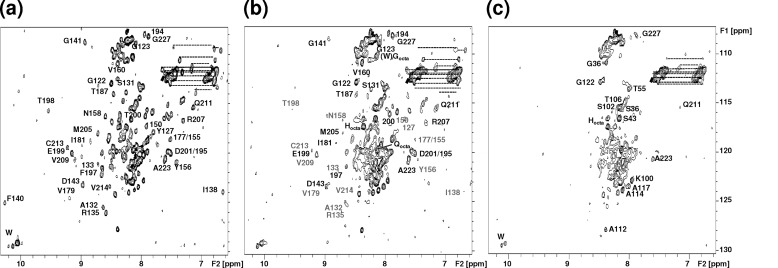

It is clear from NMR and CD that ANS binding and size-exclusion chromatography experiments of copper-catalyzed oxidation under mild conditions will generate a monomeric, helical, and molten globule conformation, within the C-terminal domain of PrPC. Interestingly, a folding intermediate of PrPC generated at low pH and high salt content has some clear similarities. 1H-15N HSQC spectra of PrP(23–231) at pH 3.6 as shown in Fig. 9 is overlaid with the copper-catalyzed oxidized PrP(23–231) spectra after 16 h. The two spectra of PrP generated under quite different conditions exhibit almost the same set of peaks that have been previously assigned to residues 23–118 of the N terminus, using three-dimensional HSQC-NOESY and TOCSY data (55). Although, the spectra have been recorded at different pH values (pH 3.6 and 5.5), there are only very minor differences between the two spectra. In particular, histidine amide resonances from the octa-repeats and adjacent amides have slight differences in chemical shift.

FIGURE 9.

Comparison of PrP(23–231) generated at pH 4 to Cu2+-catalyzed oxidation of PrP(23–231). Two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of PrP(23–231) (5.0 mg/ml) in 150 mm NaCl, 20 mm sodium acetate buffer, pH 3.6, 37 °C, in black and PrP(23–231) (3.0 mg/ml) in 10 mm sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.6, in the presence of H2O2 (10 mm) and 0.1 mol eq Cu2+ ions after 16 h of incubation at 37 °C in red.

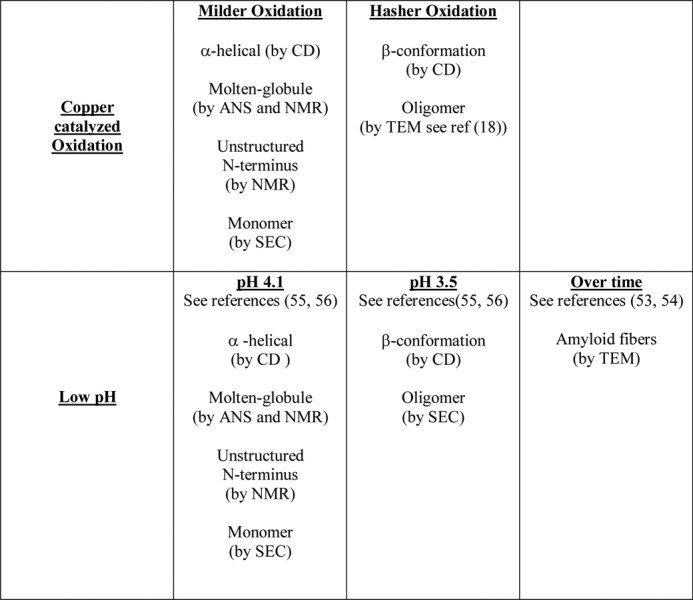

Like the copper-catalyzed species at pH 4.1, PrPC will also form a monomeric α-helical molten globule (55, 56). This work is also based on NMR, ANS binding, CD, and size-exclusion chromatography, and the comparisons are highlighted in Table 3 and Fig. 10.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of PrP folding intermediates generated by oxidation and low pH

SEC indicates size-exclusion chromatography.

FIGURE 10.

Misfolding pathway of PrP upon oxidation. Oxidation of methionines destabilizes the hydrophobic core of PrPC, and wider copper-catalyzed oxidation generates a monomeric molten globule of PrP with a high helical content. Further oxidation generates an extended β-conformation that lacks a stable cooperative fold. This has striking parallels with the pH 4 intermediate (see Table 3), which will go on and form amyloid fibers.

DISCUSSION

Oxidative stress is a key feature of the pathogenesis of prion disease (2–12); notably markers of oxidation are observed in the early preclinical stages of scrapie infection (5). Significantly, a large fraction of PrPSc isolates contain oxidized methionine residues (14). In vivo it is not clear if the significant oxidation of the methionine residues within PrP causes the cascade of events leading to PrP misfolding, mis-assembly, and disease.

Our structural studies characterize the effect of PrPC oxidation on a per residue basis. We have shown methionine oxidation to methionine sulfoxide substantially destabilizes the PrPC fold by as much as 9 kJ/mol. In particular, our data show that hydrophobic residues Val-209, Val-160, and Tyr-156 that pack against Met-212 and Met-205 are key residues perturbed upon methionine oxidation. Thermodynamically, the misfolding of PrPC to PrPSc might be favored by destabilizing the cellular form. In support of this, Met-212 and Met-205 in helix-C have been highlighted as key residues that are oxidized preceding the formation of PK-resistant PrPSc (16). In addition, molecular dynamic simulations have suggested the oxidation of Met-212 (Met-213 in the human sequence) destabilizes PrPC (67).

It is well established that Cu2+ ions bind to PrP in vivo (37). PrPC is concentrated at the synapse (68) where fluxes of Cu2+ are released during neuronal depolarization and may reach 15–250 μm levels (37, 69, 70). Cu2+ binds to PrPC in a redox active form that will readily generate hydroxyl radicals, H2O2, and other ROS in the presence of a reductant. Over time, small amounts of Cu2+ will catalytically generate appreciable levels of ROS. Like H2O2, copper-catalyzed oxidation will oxidize methionines to methionine sulfoxide but will also oxidize PrP more widely, in particular, the histidine side chains become oxidized to 2-oxo-His (15, 17, 18, 21–23). It is clear that binding of even small amounts of Cu2+ to PrPC (0.1 mol eq, 1 μm in these experiments) in the presence of physiological levels of reductant will profoundly destabilize the PrPC fold giving rise to a molten globule structure in the C-terminal half of the protein.

Interestingly, the molten globule species generated by copper-catalyzed oxidation, as shown here, has some very close parallels with the misfolded form of PrP generated under acid conditions, pH 3.5–4.1 (55). This form of PrP, referred to as the low pH intermediate, also forms a molten globule in the C-terminal domain (55). There is a transition from a molten globule, monomeric, α-helical rich species at pH 4.1 to an oligomeric species with a β-strand-like content at pH 3.5, which also causes a strong fluorescence signal with ANS binding (56, 57). Recent studies have shown this low pH form of PrP will generate amyloid fibers over time (53, 54). A similar behavior is observed for copper-catalyzed oxidized forms of PrP (highlighted in Fig. 10 and Table 3). Milder oxidizing conditions generate a monomeric molten globule form of PrP with native levels of α-helix. Further oxidation generates a β-strand-like content that has been shown by others to be oligomeric, i.e. 25–100 PrPC molecules in size (18). Our urea unfolding studies suggest this extended conformation has not formed a stable cooperative fold. It appears that although the conditions under which PrPC is destabilized (oxidation or low pH) are very different, the misfolding pathway may be shared. These observations add credence to the possibility that fiber formation under a variety of conditions will share a generic folding pathway (highlighted in Fig. 10).

It is believed that proteins with solvent accessible methionine residues can serve as a first defense against oxidative damage, scavenging ROS before they react with other cellular components (71). It has been suggested that a function of PrPC might be to act as a sacrificial quencher of ROS at the synapse generated by Cu2+-catalyzed oxidation (23). A role as an antioxidant for PrPC is highlighted by the increased oxidative stress observed in PrPC knock-out mice (72, 73). It is well established that methionine oxidation is a general feature of aging (26, 74). Furthermore, the performance of the repair enzyme, methionine sulfoxide reductase (Msr) (75), is compromised at older age and is known to determine stress resistance and life span in mammals (76, 77). One might expect the methionine repair enzyme Msr to have a protective effect in prion diseases; however, MsrA knock-out mice show incubation times similar to controls when inoculated with scrapie (78). Msr is only effective for surface-exposed methionine residues, and indeed it has been shown that Msr is ineffective at repairing methionine sulfoxide in amyloid fibers (79). This might explain why MsrA knock-out mice are no more susceptible to scrapie infection than wild-type mice (16).

Oxidative stress is a feature of a number of protein misfolding diseases. For example, oxidized methionine residues have been found at high levels in amyloid-β plaques in Alzheimer disease patients (80). Metal-associated oxidation of α-synuclein of Parkinson disease promotes fibril formation (81) and also has implications for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (82). Furthermore, it has recently been shown that methionine oxidation of Sup35 protein in yeast induces yeast prions (83).

Our studies have shown that methionines are readily oxidized within the core of PrPC and profoundly destabilize PrPC fold. Small amounts of Cu2+ will catalyze the oxidation of PrPC more widely generating a molten globule fold within the structured domain of PrPC, thought to be a key step in protein misfolding. Our studies support the suggestion that PrP oxidation may constitute an early (5) and important step in prion disease and would explain the occurrence of methionine sulfoxide in scrapie isolates (14). It has been suggested that oxidative stress, due to impaired Cu2+ homeostasis for example, may be a risk factor in the development of sporadic prion diseases (15). Indeed, it has been shown that anti-oxidant treatments can be protective against prion disease progression (84). Furthermore, copper-chelating therapy has shown some efficacy in scrapie-infected mice (24).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Harold Toms (Queen Mary, University of London) and the National Institute of Medical Research for NMR support.

This work was supported by Wellcome Trust Project Grant 093241/Z/10/Z, Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Project Grant BBD0050271, and Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Quota studentships.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S13.

- PrPC

- cellular PrP

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- PrP

- prion protein

- PrPSc

- scrapie prion protein isoform

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- CSP

- chemical shift perturbation

- ANS

- 8-anilinonaphthalene-1-sulfonate

- bis-ANS

- 4,4′-dianilino-1,1′-binaphthyl-5,5′-ANS

- FT

- Fourier transform.

REFERENCES

- 1. Prusiner S. B. (1998) Prions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 13363–13383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Milhavet O., Lehmann S. (2002) Oxidative stress and the prion protein in transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 38, 328–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kim J. I., Choi S. I., Kim N. H., Jin J. K., Choi E. K., Carp R. I., Kim Y. S. (2001) Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration in prion diseases. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 928, 182–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martin S. F., Burón I., Espinosa J. C., Castilla J., Villalba J. M., Torres J. M. (2007) Coenzyme Q and protein/lipid oxidation in a BSE-infected transgenic mouse model. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 42, 1723–1729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yun S. W., Gerlach M., Riederer P., Klein M. A. (2006) Oxidative stress in the brain at early preclinical stages of mouse scrapie. Exp. Neurol. 201, 90–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pamplona R., Naudí A., Gavín R., Pastrana M. A., Sajnani G., Ilieva E. V., Del Río J. A., Portero-Otín M., Ferrer I., Requena J. R. (2008) Increased oxidation, glycoxidation, and lipoxidation of brain proteins in prion disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 45, 1159–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Freixes M., Rodríguez A., Dalfó E., Ferrer I. (2006) Oxidation, glycoxidation, lipoxidation, nitration, and responses to oxidative stress in the cerebral cortex in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurobiol. Aging 27, 1807–1815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Milhavet O., McMahon H. E., Rachidi W., Nishida N., Katamine S., Mangé A., Arlotto M., Casanova D., Riondel J., Favier A., Lehmann S. (2000) Prion infection impairs the cellular response to oxidative stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 13937–13942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fernaeus S., Reis K., Bedecs K., Land T. (2005) Increased susceptibility to oxidative stress in scrapie-infected neuroblastoma cells is associated with intracellular iron status. Neurosci. Lett. 389, 133–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brown D. R. (2005) Neurodegeneration and oxidative stress. Prion disease results from loss of antioxidant defence. Folia Neuropathol. 43, 229–243 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee D. W., Sohn H. O., Lim H. B., Lee Y. G., Kim Y. S., Carp R. I., Wisniewski H. M. (1999) Alteration of free radical metabolism in the brain of mice infected with scrapie agent. Free Radic. Res. 30, 499–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wong B. S., Pan T., Liu T., Li R., Petersen R. B., Jones I. M., Gambetti P., Brown D. R., Sy M. S. (2000) Prion disease. A loss of antioxidant function? Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 275, 249–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stahl N., Baldwin M. A., Teplow D. B., Hood L., Gibson B. W., Burlingame A. L., Prusiner S. B. (1993) Structural studies of the scrapie prion protein using mass spectrometry and amino acid sequencing. Biochemistry 32, 1991–2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Canello T., Engelstein R., Moshel O., Xanthopoulos K., Juanes M. E., Langeveld J., Sklaviadis T., Gasset M., Gabizon R. (2008) Methionine sulfoxides on PrPSc. A prion-specific covalent signature. Biochemistry 47, 8866–8873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Requena J. R., Groth D., Legname G., Stadtman E. R., Prusiner S. B., Levine R. L. (2001) Copper-catalyzed oxidation of the recombinant SHa(29–231) prion protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 7170–7175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Canello T., Frid K., Gabizon R., Lisa S., Friedler A., Moskovitz J., Gasset M. (2010) Oxidation of helix-3 methionines precedes the formation of PK-resistant PrP. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17. Wolschner C., Giese A., Kretzschmar H. A., Huber R., Moroder L., Budisa N. (2009) Design of anti- and pro-aggregation variants to assess the effects of methionine oxidation in human prion protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 7756–7761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Redecke L., von Bergen M., Clos J., Konarev P. V., Svergun D. I., Fittschen U. E., Broekaert J. A., Bruns O., Georgieva D., Mandelkow E., Genov N., Betzel C. (2007) Structural characterization of β-sheeted oligomers formed on the pathway of oxidative prion protein aggregation in vitro. J. Struct. Biol. 157, 308–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Breydo L., Bocharova O. V., Makarava N., Salnikov V. V., Anderson M., Baskakov I. V. (2005) Methionine oxidation interferes with conversion of the prion protein into the fibrillar proteinase K-resistant conformation. Biochemistry 44, 15534–15543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sarell C. J., Wilkinson S. R., Viles J. H. (2010) Substoichiometric levels of Cu2+ ions accelerate the kinetics of fiber formation and promote cell toxicity of amyloid-β from Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 41533–41540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Requena J. R., Dimitrova M. N., Legname G., Teijeira S., Prusiner S. B., Levine R. L. (2004) Oxidation of methionine residues in the prion protein by hydrogen peroxide. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 432, 188–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wong B. S., Wang H., Brown D. R., Jones I. M. (1999) Selective oxidation of methionine residues in prion proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 259, 352–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nadal R. C., Abdelraheim S. R., Brazier M. W., Rigby S. E., Brown D. R., Viles J. H. (2007) Prion protein does not redox-silence Cu2+, but is a sacrificial quencher of hydroxyl radicals. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 42, 79–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sigurdsson E. M., Brown D. R., Alim M. A., Scholtzova H., Carp R., Meeker H. C., Prelli F., Frangione B., Wisniewski T. (2003) Copper chelation delays the onset of prion disease. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 46199–46202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Halliwell B., Gutteridge J. M. (1984) Oxygen toxicity, oxygen radicals, transition metals, and disease. Biochem. J. 219, 1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stadtman E. R. (2006) Protein oxidation and aging. Free Radic. Res. 40, 1250–1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nadal R. C., Rigby S. E., Viles J. H. (2008) Amyloid β-Cu2+ complexes in both monomeric and fibrillar forms do not generate H2O2 catalytically but quench hydroxyl radicals. Biochemistry 47, 11653–11664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Watt N. T., Taylor D. R., Gillott A., Thomas D. A., Perera W. S., Hooper N. M. (2005) Reactive oxygen species-mediated β-cleavage of the prion protein in the cellular response to oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 35914–35921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abdelraheim S. R., Královicová S., Brown D. R. (2006) Hydrogen peroxide cleavage of the prion protein generates a fragment able to initiate polymerization of full-length prion protein. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 38, 1429–1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shiraishi N., Inai Y., Bi W., Nishikimi M. (2005) Fragmentation and dimerization of copper-loaded prion protein by copper-catalyzed oxidation. Biochem. J. 387, 247–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Riek R., Hornemann S., Wider G., Billeter M., Glockshuber R., Wüthrich K. (1996) NMR structure of the mouse prion protein domain PrP(121–231). Nature 382, 180–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Riek R., Wider G., Billeter M., Hornemann S., Glockshuber R., Wüthrich K. (1998) Prion protein NMR structure and familial human spongiform encephalopathies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 11667–11672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wüthrich K., Riek R. (2001) Three-dimensional structures of prion proteins. Adv. Protein Chem. 57, 55–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Donne D. G., Viles J. H., Groth D., Mehlhorn I., James T. L., Cohen F. E., Prusiner S. B., Wright P. E., Dyson H. J. (1997) Structure of the recombinant full-length hamster prion protein PrP(29–231). The N terminus is highly flexible. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 13452–13457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Viles J. H., Donne D., Kroon G., Prusiner S. B., Cohen F. E., Dyson H. J., Wright P. E. (2001) Local structural plasticity of the prion protein. Analysis of NMR relaxation dynamics. Biochemistry 40, 2743–2753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. O'Sullivan D. B., Jones C. E., Abdelraheim S. R., Brazier M. W., Toms H., Brown D. R., Viles J. H. (2009) Dynamics of a truncated prion protein, PrP(113–231), from 15N NMR relaxation. Order parameters calculated and slow conformational fluctuations localized to a distinct region. Protein Sci. 18, 410–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brown D. R., Qin K., Herms J. W., Madlung A., Manson J., Strome R., Fraser P. E., Kruck T., von Bohlen A., Schulz-Schaeffer W., Giese A., Westaway D., Kretzschmar H. (1997) The cellular prion protein binds copper in vivo. Nature 390, 684–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Klewpatinond M., Davies P., Bowen S., Brown D. R., Viles J. H. (2008) Deconvoluting the Cu2+-binding modes of full-length prion protein. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 1870–1881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nadal R. C., Davies P., Brown D. R., Viles J. H. (2009) Evaluation of Cu2+ affinities for the prion protein. Biochemistry 48, 8929–8931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Younan N. D., Klewpatinond M., Davies P., Ruban A. V., Brown D. R., Viles J. H. (2011) Copper(II)-induced secondary structure changes and reduced folding stability of the prion protein. J. Mol. Biol. 410, 369–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Viles J. H., Cohen F. E., Prusiner S. B., Goodin D. B., Wright P. E., Dyson H. J. (1999) Copper binding to the prion protein. Structural implications of four identical cooperative binding sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 2042–2047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jones C. E., Klewpatinond M., Abdelraheim S. R., Brown D. R., Viles J. H. (2005) Probing Cu2+ binding to the prion protein using diamagnetic Ni2+ and 1H NMR. The unstructured N terminus facilitates the coordination of six Cu2+ ions at physiological concentrations. J. Mol. Biol. 346, 1393–1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Klewpatinond M., Viles J. H. (2007) Fragment length influences affinity for Cu2+ and Ni2+ binding to His-96 or His-111 of the prion protein and spectroscopic evidence for a multiple histidine binding only at low pH. Biochem. J. 404, 393–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Millhauser G. L. (2004) Copper binding in the prion protein. Acc. Chem. Res. 37, 79–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Viles J. H., Klewpatinond M., Nadal R. C. (2008) Copper and the structural biology of the prion protein. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 36, 1288–1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Liu L., Jiang D., McDonald A., Hao Y., Millhauser G. L., Zhou F. (2011) Copper redox cycling in the prion protein depends critically on binding mode. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 12229–12237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Viles J. H. (2012) Metal ions and amyloid fiber formation in neurodegenerative diseases. Copper, zinc, and iron in Alzheimer, Parkinson, and prion diseases. Coordinat. Chem. Rev., in press [Google Scholar]

- 48. Baskakov I. V., Legname G., Prusiner S. B., Cohen F. E. (2001) Folding of prion protein to its native α-helical conformation is under kinetic control. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19687–19690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Swietnicki W., Morillas M., Chen S. G., Gambetti P., Surewicz W. K. (2000) Aggregation and fibrillization of the recombinant human prion protein huPrP(90–231). Biochemistry 39, 424–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Morillas M., Vanik D. L., Surewicz W. K. (2001) On the mechanism of α-helix to β-sheet transition in the recombinant prion protein. Biochemistry 40, 6982–6987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hornemann S., Glockshuber R. (1998) A scrapie-like unfolding intermediate of the prion protein domain PrP(121–231) induced by acidic pH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 6010–6014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Swietnicki W., Petersen R., Gambetti P., Surewicz W. K. (1997) pH-dependent stability and conformation of the recombinant human prion protein PrP(90–231). J. Biol. Chem. 272, 27517–27520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bjorndahl T. C., Zhou G. P., Liu X., Perez-Pineiro R., Semenchenko V., Saleem F., Acharya S., Bujold A., Sobsey C. A., Wishart D. S. (2011) Detailed biophysical characterization of the acid-induced PrP(c) to PrP(β) conversion process. Biochemistry 50, 1162–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cobb N. J., Apetri A. C., Surewicz W. K. (2008) Prion protein amyloid formation under native-like conditions involves refolding of the C-terminal α-helical domain. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 34704–34711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. O'Sullivan D. B., Jones C. E., Abdelraheim S. R., Thompsett A. R., Brazier M. W., Toms H., Brown D. R., Viles J. H. (2007) NMR characterization of the pH 4 β-intermediate of the prion protein. The N-terminal half of the protein remains unstructured and retains a high degree of flexibility. Biochem. J. 401, 533–540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gerber R., Tahiri-Alaoui A., Hore P. J., James W. (2007) Oligomerization of the human prion protein proceeds via a molten globule intermediate. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 6300–6307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gerber R., Tahiri-Alaoui A., Hore P. J., James W. (2008) Conformational pH dependence of intermediate states during oligomerization of the human prion protein. Protein Sci. 17, 537–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kay L., Keifer P., Saarinen T. (1992) Pure absorption gradient-enhanced heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectroscopy with improved sensitivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114, 10663–10665 [Google Scholar]

- 59. Garrett D. S., Seok Y. J., Peterkofsky A., Clore G. M., Gronenborn A. M. (1997) Identification by NMR of the binding surface for the histidine-containing phosphocarrier protein HPr on the N-terminal domain of enzyme I of the Escherichia coli phosphotransferase system. Biochemistry 36, 4393–4398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Klewpatinond M., Viles J. H. (2007) Empirical rules for rationalizing visible circular dichroism of Cu2+ and Ni2+ histidine complexes. Applications to the prion protein. FEBS Lett. 581, 1430–1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wildegger G., Liemann S., Glockshuber R. (1999) Extremely rapid folding of the C-terminal domain of the prion protein without kinetic intermediates. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 550–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Crowhurst K. A., Tollinger M., Forman-Kay J. D. (2002) Cooperative interactions and a non-native buried Trp in the unfolded state of an SH3 domain. J. Mol. Biol. 322, 163–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Clarke J., Fersht A. R. (1993) Engineered disulfide bonds as probes of the folding pathway of barnase. Increasing the stability of proteins against the rate of denaturation. Biochemistry 32, 4322–4329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hawe A., Sutter M., Jiskoot W. (2008) Extrinsic fluorescent dyes as tools for protein characterization. Pharm. Res. 25, 1487–1499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Schenck H. L., Dado G. P., Gellman S. H. (1996) Redox-triggered secondary structure changes in the aggregated states of a designed methionine-rich peptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 12487–12494 [Google Scholar]

- 66. Martins S. M., Chapeaurouge A., Ferreira S. T. (2003) Folding intermediates of the prion protein stabilized by hydrostatic pressure and low temperature. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 50449–50455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Colombo G., Meli M., Morra G., Gabizon R., Gasset M. (2009) Methionine sulfoxides on prion protein helix-3 switch on the α-fold destabilization required for conversion. PLoS One 4, e4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Herms J., Tings T., Gall S., Madlung A., Giese A., Siebert H., Schürmann P., Windl O., Brose N., Kretzschmar H. (1999) Evidence of presynaptic location and function of the prion protein. J. Neurosci. 19, 8866–8875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hartter D. E., Barnea A. (1988) Evidence for release of copper in the brain. Depolarization-induced release of newly taken-up 67Cu. Synapse 2, 412–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kardos J., Kovács I., Hajós F., Kálmán M., Simonyi M. (1989) Nerve endings from rat brain tissue release copper upon depolarization. A possible role in regulating neuronal excitability. Neurosci. Lett. 103, 139–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Levine R. L., Mosoni L., Berlett B. S., Stadtman E. R. (1996) Methionine residues as endogenous antioxidants in proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 15036–15040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Klamt F., Dal-Pizzol F., Conte da Frota M. L., Jr., Walz R., Andrades M. E., da Silva E. G., Brentani R. R., Izquierdo I., Fonseca Moreira J. C. (2001) Imbalance of antioxidant defense in mice lacking cellular prion protein. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 30, 1137–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wong B. S., Liu T., Li R., Pan T., Petersen R. B., Smith M. A., Gambetti P., Perry G., Manson J. C., Brown D. R., Sy M. S. (2001) Increased levels of oxidative stress markers detected in the brains of mice devoid of prion protein. J. Neurochem. 76, 565–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Stadtman E. R., Van Remmen H., Richardson A., Wehr N. B., Levine R. L. (2005) Methionine oxidation and aging. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1703, 135–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Weissbach H., Etienne F., Hoshi T., Heinemann S. H., Lowther W. T., Matthews B., St John G., Nathan C., Brot N. (2002) Peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase. Structure, mechanism of action, and biological function. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 397, 172–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Petropoulos I., Friguet B. (2005) Protein maintenance in aging and replicative senescence. A role for the peptide methionine sulfoxide reductases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1703, 261–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Cabreiro F., Picot C. R., Friguet B., Petropoulos I. (2006) Methionine sulfoxide reductases. Relevance to aging and protection against oxidative stress. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1067, 37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Tamgüney G., Giles K., Glidden D. V., Lessard P., Wille H., Tremblay P., Groth D. F., Yehiely F., Korth C., Moore R. C., Tatzelt J., Rubinstein E., Boucheix C., Yang X., Stanley P., Lisanti M. P., Dwek R. A., Rudd P. M., Moskovitz J., Epstein C. J., Cruz T. D., Kuziel W. A., Maeda N., Sap J., Ashe K. H., Carlson G. A., Tesseur I., Wyss-Coray T., Mucke L., Weisgraber K. H., Mahley R. W., Cohen F. E., Prusiner S. B. (2008) Genes contributing to prion pathogenesis. J. Gen. Virol. 89, 1777–1788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Binger K. J., Griffin M. D., Heinemann S. H., Howlett G. J. (2010) Methionine-oxidized amyloid fibrils are poor substrates for human methionine sulfoxide reductases A and B2. Biochemistry 49, 2981–2983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Dong J., Atwood C. S., Anderson V. E., Siedlak S. L., Smith M. A., Perry G., Carey P. R. (2003) Metal binding and oxidation of amyloid-β within isolated senile plaque cores. Raman microscopic evidence. Biochemistry 42, 2768–2773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Yamin G., Glaser C. B., Uversky V. N., Fink A. L. (2003) Certain metals trigger fibrillation of methionine-oxidized α-synuclein. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 27630–27635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Rakhit R., Cunningham P., Furtos-Matei A., Dahan S., Qi X. F., Crow J. P., Cashman N. R., Kondejewski L. H., Chakrabartty A. (2002) Oxidation-induced misfolding and aggregation of superoxide dismutase and its implications for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 47551–47556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Sideri T. C., Koloteva-Levine N., Tuite M. F., Grant C. M. (2011) Methionine oxidation of Sup35 protein induces formation of the [PSI+] prion in a yeast peroxiredoxin mutant. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 38924–38931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Brazier M. W., Doctrow S. R., Masters C. L., Collins S. J. (2008) A manganese-superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetic extends survival in a mouse model of human prion disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 45, 184–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.