Abstract

It was previously concluded that opposing gradients of sulphate and methane, observations of 16S ribosomal DNA sequences displaying great similarity to those of anaerobic methane-oxidizing Archaea and a peak in sulphide concentration in groundwater from a depth of 250–350 m in Olkiluoto, Finland, indicated proper conditions for methane oxidation with sulphate. In the present research, pressure-resistant, gas-tight circulating systems were constructed to enable the investigation of attached and unattached anaerobic microbial populations from a depth of 327 m in Olkiluoto under in situ pressure (2.4 MPa), diversity, dissolved gas and chemistry conditions. Three parallel flow cell cabinets were configured to allow observation of the influence on microbial metabolic activity of 11 mℳ methane, 11 mℳ methane plus 10 mℳ H2 or 2.1 mℳ O2 plus 7.9 mℳ N2 (that is, air). The concentrations of these gases and of organic acids and carbon, sulphur chemistry, pH and Eh, ATP, numbers of cultivable micro-organisms, and total numbers of cells and bacteriophages were subsequently recorded under batch conditions for 105 days. The system containing H2 and methane displayed microbial reduction of 0.7 mℳ sulphate to sulphide, whereas the system containing only methane resulted in 0.2 mℳ reduced sulphate. The system containing added air became inhibited and displayed no signs of microbial activity. Added H2 and methane induced increasing numbers of lysogenic bacteriophages per cell. It appears likely that a microbial anaerobic methane-oxidizing process coupled to acetate formation and sulphate reduction may be ongoing in aquifers at a depth of 250–350 m in Olkiluoto.

Keywords: acetate, AMO, ATP, redox potential, bacteriophage, microarray

Introduction

Depth profiles of anaerobic aquatic sediments where sulphate and methane meet with the concomitant occurrence of sulphide have been interpreted as evidence of anaerobic methane oxidation (AOM) with sulphate as the final electron acceptor (Zehnder and Brock, 1980; Thomsen et al., 2001; Knittel and Boetius, 2009). A typical such sulphate–methane transition zone, albeit on a much broader scale than in aquatic sediments, was evident from the analysis of methane, sulphate and sulphide over depth in groundwater below the island of Olkiluoto, Finland (Pedersen et al., 2008). In the 250–350-m depth zone, the sulphate concentration decreased with depth from 5 to <0.1 mℳ, whereas methane increased with depth from 40 μℳ to 4 mℳ. In addition, the sulphide concentration in this zone reached approximately 300 μℳ at several sampled sites, which was 10–15 times higher than that found in shallower or deeper groundwater. Similarly, the total number of cells (TNCs), ATP concentration and numbers of culturable sulphate-reducing bacteria (SRB) were greater in groundwater samples from this zone than in shallower or deeper samples (Pedersen et al., 2008). It was concluded that the sulphate–methane transition zone under Olkiluoto likely offered proper conditions for a microbial AOM process involving sulphate as electron acceptor.

The island of Olkiluoto has been selected for the construction of a deep repository for spent nuclear fuel (SNF) and other high-level radioactive wastes. A tunnel system denoted ONKALO is under construction (www.posiva.fi) and has reached its final depth of 454 m below ground. This tunnel system serves two purposes, allowing research into issues related to the safe disposal of SNF and access to the future SNF repository. The Olkiluoto SNF repository will be situated at a sulphate-free and methane-rich depth of 500 m. The safety analysis of repository performance must include a scenario in which shallow, sulphate-rich groundwater reaches the repository. This is because the Finnish disposal concept includes encapsulation of SNF in copper and SRB produce sulphide that is corrosive to copper. Therefore, a research programme has been initiated to study the risk of sulphide production in the event that sulphate-rich groundwater penetrates to repository depth and mixes with deep, methane-rich groundwater (Aalto et al., 2009). The research presented here was a part of that programme, which addresses the following question: will microbial AOM commence with sulphate reduction and generate sulphide in amounts that could threaten the integrity of the copper canisters?

The ONKALO tunnel enables investigations of microbial activity under in situ conditions, similar to the investigations previously performed in the Äspö Hard Rock Laboratory (HRL) tunnel. In the Äspö HRL, the influence of acetate, H2, and O2 on microbial activity could be investigated using flow cell (FC) circulating systems operating under in situ conditions, including pressure, at a depth of 450 m (Pedersen et al., 2012a, 2012b). Installing FC circulating systems in the ONKALO tunnel at a depth of 327 m enabled the investigation of microbial sulphate-reduction activity in groundwater from an aquifer where mixing between methane- and sulphate-rich deep and shallow groundwater, respectively, was ongoing. This mixing was driven by a slow and diffuse outflow of groundwater to the tunnel via aquifers intersected by the tunnel.

In the present work, three parallel FC cabinets (FCCs) were configured with four FCs each to permit observation of the effect on microbial metabolic activity of 11 mℳ methane, 10 mℳ H2 plus 11 mℳ methane or 2.1 mℳ O2 plus 7.9 mℳ N2 (that is, air). The FCs were first inoculated under an in situ pressure of 2.4 MPa in the ONKALO tunnel with circulating groundwater from a selected aquifer at a depth of 327 m for 110 days, after which they were installed in the laboratory in three independent FCCs under in situ conditions and supplied with their respective added gases. The concentrations of H2, methane, sulphate, sulphide, ferrous iron, and organic acids and carbon as well as pH and Eh were subsequently recorded under batch conditions for 105 days. The numbers of cultivable heterotrophic aerobic bacteria (CHAB), SRB, nitrate-reducing bacteria (NRB), iron-reducing bacteria (IRB), manganese-reducing bacteria (MRB), autotrophic acetogens (AAs), autotrophic methanogens (AMs) and virus-like particles (VLPs) as well as the TNC and amounts of unattached and attached biomass measured as ATP were also monitored over this period. The microbial diversities of cultures and of attached micro-organisms were compared using microarrays. The effects of the different gas additions were evaluated.

Materials and methods

Groundwater source

A 76-mm diameter borehole denoted ONK-PVA06 was drilled in a niche of the ONKALO tunnel at a depth of 318.7 m (Toropainen, 2009). The drilling was done at a –14.8% inclination on 3–4 November 2009 to a total length of 35.15 m. A metal-free packer system isolated an aquifer in the borehole located 32.7–32.9 m from the tunnel rock face at a depth of 327 m; the groundwater was directed by this packer system to the FCs described below and back to the aquifer via two parallel, 1/8-inch polyetheretherketone thermoplastic tubes of high-pressure liquid chromatography quality (IDEX Health and Science, Oak Harbor, WA, USA). The packer system is described in detail elsewhere (Pedersen, 2005) and an overview is presented in Supplementary Figure 1.

Groundwater characterization

The microbiology of the ONK-PVA06 groundwater was analysed in samples collected on 23 September 2010 as described elsewhere (Pedersen et al., 2008). Groundwater chemistry was analysed in samples collected on 8 November 2010 and transferred to the Teollisuuden Voima Oy laboratory directly after sampling. The chemical analyses were performed by Teollisuuden Voima Oy according to their protocols, or were subcontracted to external laboratories as described in detail elsewhere (see Supplementary Table 3 in Pedersen et al., 2008).

FC systems for fieldwork, configuration of experiments and sampling procedures

Three identical field systems with four FCs each were installed in a container placed in a tunnel niche at a depth of 320 m in the ONKALO tunnel, as shown in Supplementary Figure 2, and connected to the packer system in ONK-PVA06 as described in Supplementary materials and methods. The 12 FCs exposed to ONK-PVA06 groundwater for 110 days were transported under pressure from the ONKALO tunnel to the laboratory in Mölnlycke and installed, four by four, in three FCCs. These FCCs have been described in detail elsewhere (Pedersen, 2005; Hallbeck and Pedersen, 2008) and are shown in Supplementary Figure 3. Gases were added corresponding to final theoretical concentrations of 7.9 mℳ N2 plus 2.1 mℳ O2, 11 mℳ methane and 11 mℳ methane plus 10 mℳ H2 (including 2.7 mℳ naturally occurring methane in the groundwater); these treatments are hereafter denoted O2:N2, CH4 and H2:CH4, respectively. Further configuration details are given in Supplementary materials and methods. Sampling for analysis was performed six times, on days 3, 21, 42, 63, 84 and 105, as described in Supplementary materials and methods.

Eh in FCCs with internal electrodes

Four pressure-resistant microsensor Eh electrode couples, each with one platinum micro-electrode with a tip diameter of 400–600 μm (RD500; Unisense A/S, Aarhus, Denmark) and one Ag/AgCl reference electrode with a tip diameter of 90–110 μm in gel-stabilized electrolyte (REF100; Unisense A/S), were installed in line in each FCC circulation system as described previously (Pedersen, 2012b).

pH and Eh measured using external electrodes

Eh was analysed using a HACH HQ40d portable multimetre (HACH Lange AB, Sköndal, Sweden) equipped with a MTC101-05 probe (HACH Lange AB) installed in a FC connected to the analysed FCC. This installation avoided contact with air that could have influenced Eh because of the degassing of H2, carbon dioxide and sulphide from the samples. pH was determined using 5 ml subsamples immediately following extraction from the FCCs, using a Schott CG84310 pH metre (SI Analytics GmbH, Mainz, Germany) fitted with a BlueLine 13 pH electrode (VWR International LLX, Radnor, PA, USA), calibrated as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Analysis of sulphate and of sulphur isotope composition in sulphate

Samples for sulphate analysis were collected in sterile 15 ml PP tubes and frozen at –20 °C until analysis using the SulfaVer 4 method (method no. 8051, programme 680; HACH Lange AB; range 0.03–0.73 mℳ with 95% confidence limits of distribution of ±10%). Samples for the analysis of the δ34S values of sulphate were collected in 125 ml polypropylene bottles (Nalgene, Rochester, NY, USA; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and sent for analysis using an elemental analyser–isotopic ratio mass spectrometer to Iso-Analytical Limited (Crewe, UK).

Acetate, lactate, organic carbon, ferrous iron and sulphide analyses

Acetate and lactate concentrations were determined using the enzymatic UV method (kit no. 10148261035 for acetate and kit no. 10139084035, for lactate; Boehringer Mannheim/R-Biopharm AG, Darmstadt, Germany) using a Genesys 10UV spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for detection. Samples for the analysis of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) were diluted 1–100 times before analysis to obtain the optimal analytical concentration range. Samples of 14 ml were filtered through 0.2 μm hydrophilic syringe filters (Minisart; Sartorius Stedim Biotech, Goettingen, Germany) and deep frozen at −20 °C until analysis at the Department of System Ecology, Stockholm University, according to Swedish Standard SS-EN 1484. The detection limit for DOC was 20 μℳ and the uncertainty was ±20 μℳ<420 μℳ and 7%>420 μℳ. Sulphide was analysed using a colorimetric methylene blue method with an uncertainty of ±17% (Swedish standard method SIS 028115). Ferrous iron concentrations were determined using the 1–10 phenanthroline method (method no. 8146, programme 255, HACH Lange AB; range 0.4–54 mℳ with 95% confidence limits of distribution of ±11%).

ATP analysis

The ATP Biomass Kit HS (no. 266–311; BioThema, Handen, Stockholm, Sweden) was used to determine total ATP in living cells in groundwater. The ATP biomass method used here has been described, tested in detail and evaluated for use with Fennoscandian Shield groundwater (Eydal and Pedersen, 2007). The method was applied on biomass attached to the rock grains with the following modification. Approximately 10 rock grains were sampled from each of two FCs per FCC and placed in ATP extraction solution and analysed. Samples were diluted before analysis to obtain the optimal analytical concentration range.

Total number of cells

The TNC ml–1 was determined in 10 ml samples using the acridine orange direct count method as devised by Hobbie et al. (1977) and modified by Pedersen and Ekendahl (1990).

Total number of VLPs

Total numbers of VLPs were determined using a direct count method with SYBR Gold (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to Noble and Fuhrman (1998) and Chen et al. (2001).

Gas sampling and analysis

Water samples were collected using a pressure vessel as described elsewhere (Hallbeck and Pedersen, 2008). Extraction and analysis of gas subsequently followed procedures described previously by Pedersen (2012b).

Analysis of most probable numbers of culturable anaerobic micro-organisms

Media were prepared for CHAB and the most probable number analysis (MPN) of NRB, IRB, MRB, SRB, AA and AM as described elsewhere (Hallbeck and Pedersen, 2008). Five tubes were used for each 10 times dilution, resulting in an approximate 95% confidence interval lower limit of 1/3 of the obtained value and an upper limit of three times the value (Greenberg et al., 1992). The cultivation time was about 8 weeks to ensure that slow-growing micro-organisms would be included in the results. Sampling and analysis were conducted on days 0 and 105 for IRB and MRB, whereas NRB, SRB and AA were sampled and analysed on all full sampling occasions.

DNA analysis of attached communities

DNA was extracted from attached communities on rock grains collected from CH4 and H2:CH4 FCs on day 118 and analysed using the G3 PhyloChip assay (Hazen et al., 2010) by Second Genome Inc. (San Bruno, CA, USA) as outlined in Supplementary materials and methods.

Statistical analyses

Data graphics design and statistical analyses were performed in Statistica 10 (Statsoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

Results

Experimental conditions

Previous groundwater microbiology experiments at in situ pressure and chemistry were performed from start to finish in the underground Äspö HRL (Nielsen et al., 2006; Anderson et al., 2007; Pedersen, 2012a, 2012b). In the present work, the transfer of the pressurized FCs, containing biofilms and groundwater, to the FCCs in the ground-level laboratory offered improved continuous surveillance of the systems and more efficient sampling and analytical conditions than in the previous underground FCC installation.

Groundwater characterization

There were 3.7 × 104 cells ml–1 and 2.8 × 104 amol ATP ml–1 in the groundwater analysed on 23 September 2010. NRB dominated the MPN determination and, except for the MPN of methanogens, all samples were above the detection limit (Table 1). The groundwater analysed on 8 November 2010 had a pH of 7.6 (analysed in the Teollisuuden Voima Oy laboratory), a conductivity of 1520 ms m–1, and a temperature of 11 °C. The major dissolved solids were 150 mℳ Cl–, 91 mℳ Na+, 28 mℳ Ca2+ and 1.0 mℳ SO42–. The following were also analysed: PO4– and NO3– at <0.01 μℳ, 1.7 μℳ NH4+, 36 μℳ Fe2+, <0.01 μℳ HS–, 230 μℳ HCO3 and 0.2 mℳ DOC. There was 0.07 μℳ H2 and 4.5 mℳ CH4 dissolved in the groundwater analysed on 23 September 2010.

Table 1. The most probable numbers of culturable micro-organisms and the total number of cells in groundwater from borehole ONK-PVA06 sampled on 23 September 2010.

| Analysis | Cells ml–1 | Amol ml–1 | s.d. (n=3) | Upper–lower 95% confidence interval (cells ml–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of cells | 37 000 | — | 6100 | — |

| ATP | 27 300 | 3170 | — | |

| Cultivable heterotrophic aerobic bacteria | 16 300 | — | 3210 | — |

| Nitrate-reducing bacteria | 90 000 | — | — | 30 000–290 000 |

| Iron-reducing bacteria | 500 | — | — | 200–2000 |

| Manganese-reducing bacteria | 220 | — | — | 100–580 |

| Sulphate-reducing bacteria | 80 | — | — | 30–250 |

| Autotrophic acetogens | 17 | — | — | 7–48 |

| Heterotrophic acetogens | 110 | — | — | 40–300 |

| Autotrophic methanogens | <0.2 | — | — | — |

| Heterotrophic methanogens | <0.2 | — | — | — |

pH, Eh and gases

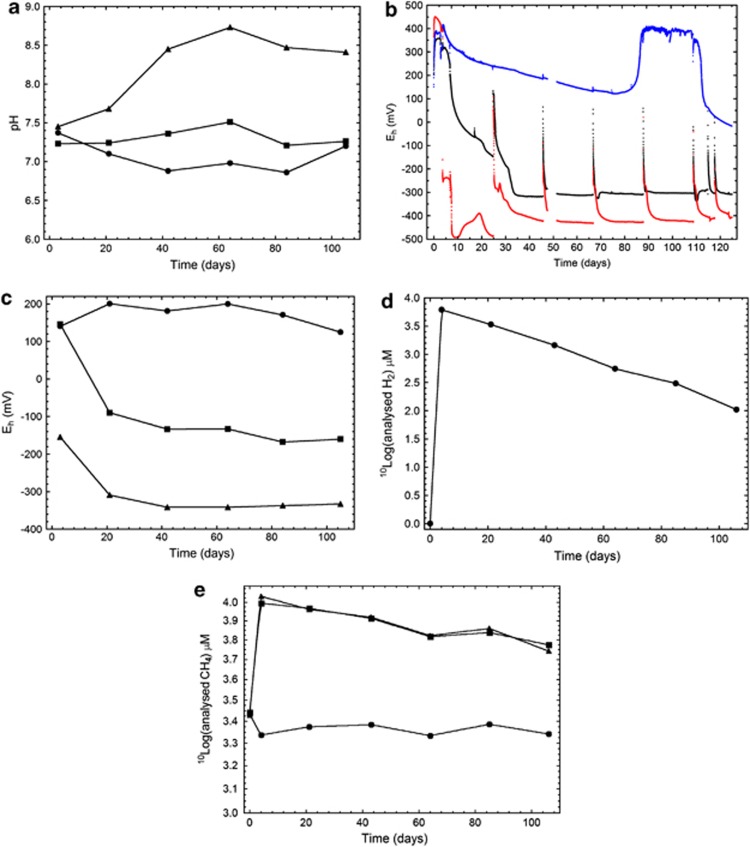

The pH increased from the starting value of approximately 7.4 to approximately 8.5 in the H2:CH4 FCC after 40 days, but did not increase in the other two FCCs (Figure 1a). The Eh of the H2:CH4 FCC rapidly decreased to approximately –400 mV, as registered by the internal microelectrodes (Figure 1b). The Eh of the CH4 FCC decreased as well, reaching a steady level of –300 mV after 35 days, whereas the Eh of the O2:N2 FCC slowly decreased to 0 mV by the end of the experiment. A technical problem occurred with the electrodes in O2:N2, which lost contact with the FCC between days 90 and 110. Sampling the rock grains for ATP and DNA analysis inevitably introduced small amounts of O2 when the FCs were opened, as indicated by the peaks in Eh after each sampling occasion (Figure 1b). This effect diminished within a few days, as expected from previous Äspö HRL results, indicating the effect of adding 0.1–0.2 mℳ O2 (Pedersen, 2012b). The internal Eh electrodes reported these effects in continuous mode and were superior in sensitivity to the external Eh electrode (Figure 1c). The addition of gases resulted in expected concentrations of H2 (10 mℳ) and methane (11 mℳ Figures 1d and e). The O2 concentration was 2.2 mℳ in the O2:N2 system on day 0 and decreased linearly to 0.2 mℳ by day 105.

Figure 1.

(a) The pH and (b) Eh measured using internal electrode couples, average of four electrode signals; (c) Eh measured using an external multimetre (mV); (d) dissolved H2 concentration and (e) dissolved methane concentration in FCC circulations supplemented with 2.2 mℳ O2 plus 7.9 mℳ N2 (•, blue line in b), 11 mℳ methane (▪, black lines in b) and 10 mℳ H2 plus 11 mℳ methane (▴, red lines in b).

The H2 concentration decreased exponentially in the H2:CH4 FCC from just below 10 mℳ at start to 0.1 mℳ after 105 days as a result of microbial consumption and diffusion out of the system (Figure 1d). Similar decreasing trends have been observed and discussed previously for H2 in the FCCs (Pedersen, 2012a). Both the CH4 and the H2:CH4 FCCs were amended with 8 mℳ methane, which supplemented the in situ concentration of 2.7 mℳ as found in the O2:N2 system, resulting in a total of just below 11 mℳ methane (Figure 1e). The methane concentration decreased exponentially in the CH4 and the H2:CH4 FCCs from just below 11 mℳ at start to 5.5 mℳ after 105 days, possibly due to microbial consumption. Diffusion of methane out of the system, or aerobic microbial oxidation, did not occur in the inactivated N2:O2 FCC, suggesting that the observed drop in methane concentration for the amended FCCs was due to an AOM process.

Numbers of cells and VLPs; amount of ATP

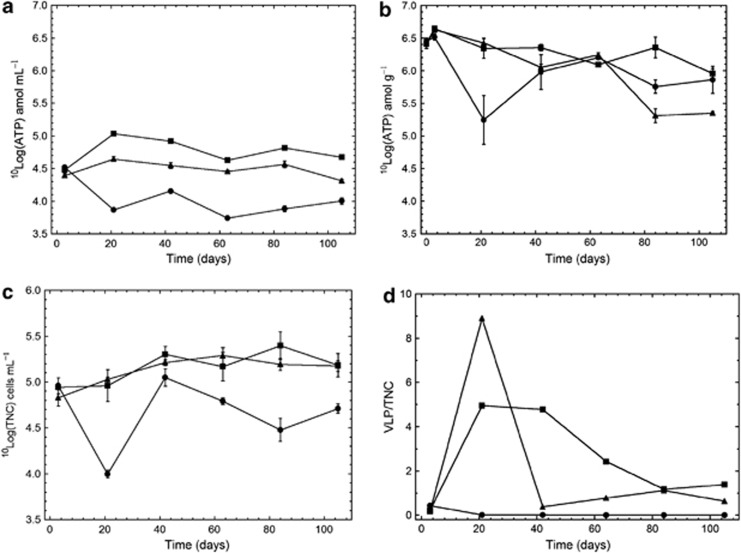

The rock grains in the FCCs were colonized by micro-organisms, as revealed by the ATP (Figure 2b) and DNA (Supplementary information Figure 4) analyses. Applying the previously observed average ATP content of approximately 0.4 amol per cell (Eydal and Pedersen, 2007; Pedersen, 2012a), the number of attached cells averaged 1.1 × 109 cells per FCC, that is, 106 amol ATP g–1 × 440 g FCC–1/0.4 amol ATP cell–1. The corresponding average number of unattached cells was 0.5 × 109 cells per FCC (that is, 1 × 105 cells ml–1 × 5000 ml). Consequently, approximately two-thirds of the biomass was attached and one third was unattached in the FCCs.

Figure 2.

(a) ATP in circulating groundwater; (b) ATP on rock grains; (c) TNCs in circulating groundwater; and (d) the number of VLPs per cell in circulating groundwater in the three FCCs supplemented with 2.2 mℳ O2 plus 7.9 mℳ N2 (•), 11 mℳ methane (▪) and 10 mℳ H2 plus 11 mℳ methane (▴). Whiskers indicate ±1 s.d.; n=3 in a, c; and n=6 in b.

The amount of ATP ml–1 and the TNC ml–1 did not differ significantly between the CH4 and H2:CH4 FCCs, but was significantly lower in the O2:N2 FCC (Figures 2a and c). In contrast, the amounts of ATP g–1 rock grain did not differ over time between any of the FCCs (Figure 2b). The number of VLPs increased rapidly after 20 days in both the CH4 and the H2:CH4 systems, as indicated by the numbers of VLPs per cell in Figure 2d, whereas the VLP counts decreased to below detection (<100 VLPs ml–1) in the O2:N2 FCC after 20 days.

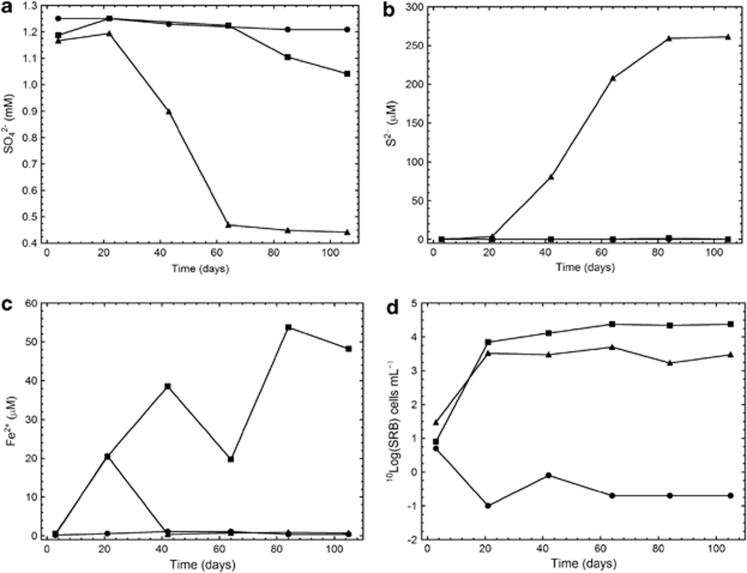

FCC chemistry

The sulphate concentration decreased by approximately 700 μℳ by day 105 compared with the starting concentration in the H2:CH4 FCC (Figure 3a). Sulphate decreased by 200 μℳ in the CH4 FCC and did not change significantly in the O2:N2 system. The sulphide concentration increased to approximately 250 μℳ in the H2:CH4 FCC and was below detection (0.01 μℳ) in the other two FCCs (Figure 3b). Ferrous iron increased to approximately 50 μℳ in the CH4 FCC and was below detection in the other FCCs, except on day 20 in the H2:CH4 FCC when the concentration was 20 μℳ (Figure 3c). An increase in pH was observed in the H2:CH4 FCC because of the protons consumed by the sulphate-reduction process with H2 (that is, 4 H2+SO42–+H+→HS–+4 H2O).

Figure 3.

Concentrations of (a) sulphate, (b) sulphide, and (c) ferrous iron as well as (d) the most probable number of SRB in the groundwater circulating through the three FC cabinets supplemented with 2.2 mℳ O2 plus 7.9 mℳ N2 (•), 11 mℳ methane (▪) and 10 mℳ H2 plus 11 mℳ methane (▴).

Cultivated micro-organisms and organic acids and carbon

The MPN of SRB increased in the CH4 and the H2:CH4 FCCs, with the largest values observed in the CH4 FCC, whereas the MPN of SRB decreased to below detection (0.2 cells ml–1) in the O2:N2 FCC (Figure 3d). The MPN of SRB was 5 to 10 times larger in the CH4 FCC than in the H2:CH4 FCC, but sulphate reduction, observed as a decrease in SO42– (Figure 3a), was only 200 μℳ compared with the 700 μℳ decrease in the H2:CH4 FCC. Although 700 μℳ sulphate was consumed, 250 μℳ sulphide was observed (Figure 3b); the remaining sulphide was likely precipitated as iron sulphide, which was observed as a black precipitate in the FCs when sampling the rock grains. Ferrous iron was observed after 20 days (Figure 3c), whereas sulphide was below detection. Thereafter, any produced ferrous iron would have been precipitated with sulphide. There were significant 1.5‰ and 2.5‰ increases in the δ34SV-CDT for sulphate in the CH4:H2 and the CH4 FCCs, respectively, compared with the inactive O2:N2 FCC, which attests that microbiological sulphate reduction did occur (Table 2). This fractionation was larger per amount of reduced sulphate in the CH4 FCC (1.5/200=0.008) than in the H2:CH4 FCC (2.5/700=0.004), possibly due to the difference in SRB diversity between the FCCs that was revealed by the PhyloChip analysis as described next. This is because there is a very large range of fractionation ability between various SRB species (Detmers et al., 2001).

Table 2. The most probable number of IRB and MRB, respectively, and the δ34S ratio for sulphate in the three FCCs supplemented with 2.2 mℳ O2 plus 7.9 mℳ N2 (O2:N2), 11 mℳ methane (CH4), and 10 mℳ H2 plus 11 mℳ methane (H2:CH4).

| Sampling day |

IRB (cells ml–1) (95% confidence limits cells ml–1) |

MRB (cells ml–1) (95% confidence limits cells ml–1) |

34SV-CDT(‰) ±s.d., n=3 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O2:N2 | CH4 | H2:CH4 | O2:N2 | CH4 | H2:CH4 | O2:N2 | CH4 | H2:CH4 | |

| 0 | 140 (60–360) | 140 (60–360) | 80 (36–250) | 500 (200–2000) | 300 (100–1300) | 900 (300–2900) | 29.57 (±0.22) | 29.92 (±0.14) | 30.58 (±0.13) |

| 3 | NA | — | — | — | — | — | 30.27(±0.19) | 30.04 (±0.21) | 29.85 (±0.20) |

| 105 | 2.3 (0.9–8.6) | >1600 (–) | 13 (5–39) | 1.1 (0.4.2.9) | 500 (200–2000) | 1.7 (0.7–4.6) | 29.14 (±0.24) | 31.69 (±0.21) | 32.64 (±0.19) |

Abbreviations: FCC, flow cell cabinet; IRB, iron-reducing bacteria; MRB, manganese-reducing bacteria; NA, not analysed; V-CDT, Vienna Cañon Diablo Meteorite Standard.

s.d., standard deviation.

All isotope ratios are reported in δ34S notation (per mil, ‰) relative to the V-CDT.

In the CH4 FCC, the MPN of IRB increased, as did the concentration of ferrous iron, on day 105 as compared with day 0, whereas the MPN of MRB remained essentially the same (Tables 1 and 2). In contrast, the MPNs of IRB and MRB decreased to values close to the detection limits in the H2:CH4 and the O2:N2 FCCs.

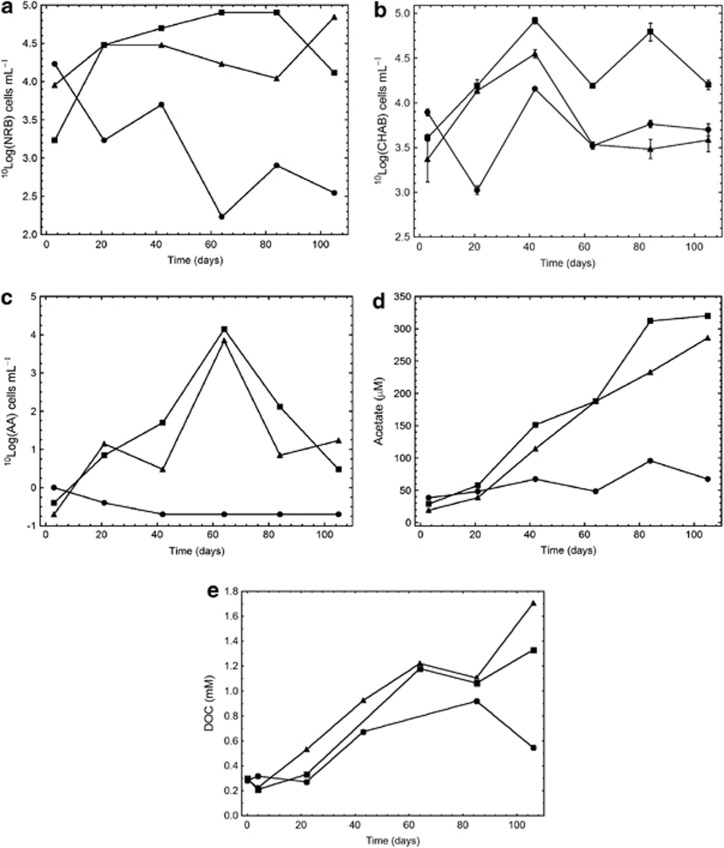

The MPNs of NRB were similar in the CH4 and H2:CH4 FCCs throughout the experiment at 3.2 × 104 cells ml–1, compared with what was observed in the groundwater at the start (9 × 104 cells ml–1, Table 1), but decreased to <500 cells ml–1 in the O2:N2 FCC (Figure 4a). Similarly, the numbers of CHAB were similar throughout the experiment in all FCCs, with approximately 4 × 103 cells ml–1 in the H2:CH4 and O2:N2 FCCs and 2.5 × 104 cells ml–1 in the CH4 FCC (Figure 4b). The MPN of AA increased concomitantly in the CH4 and the H2:CH4 FCCs to at most 1 × 104 AA ml–1 after 60 days (Figure 4c) and the acetate concentration increased to approximately 300 μℳ acetate after 105 days in both these FCCs (Figure 4d). The concentration of DOC increased to 1.3 and 1.7 mℳ in the CH4 and the H2:CH4 FCCs respectively, and stopped at <0.6 mℳ in the O2:N2 FCC (Figure 4e). The AA decreased to below detection and the acetate concentration did not change in the O2:N2 FCC. The MPNs of AM were below detection limits on all sampling occasions in all FCCs. Lactate was present at low concentrations, 10–16 μℳ, until day 40 when the concentration of this compound declined to below detection in all three FCCs.

Figure 4.

The numbers of NRB, (b) CHAB, and (c) AAs as well as (d) the acetate concentration and (e) DOC concentration in the groundwater circulating through the three FC cabinets supplemented with 2.2 mℳ O2 plus 7.9 mℳ N2 (•), 11 mℳ methane (▪) and 10 mℳ. Whiskers in b indicate ±1 s.d.; n=3.

Introducing 2.2 mℳ O2 into the O2:N2 FCC was chosen as a method to create an inactivated control, and this approach was successful in that the inactivation effect was sustained for 105 days. The obligate anaerobic micro-organisms, that is, the MPN of SRB and AA and the MPN of the facultative anaerobic NRB, all decreased toward their detection limits in the O2:N2 FCC (Figures 3d, 4a, c), whereas the aerobic CHAB results remained around the day 3 values for most of the experiment. Anaerobic microbial processes were obviously halted by the O2 addition, but some aerobic microbial activity may have been ongoing, as suggested by the slowly decreasing Eh in this FCC (Figure 1b). There was no acetate production or acetogen growth in the O2:N2 FCC, whereas acetate and the MPN of AA increased in the other two FCCs, which further attests to the inhibiting effect of the aeration. This also demonstrated that the acetate production in these systems was microbiological and not an artefact produced by the FC thermoplastic construction materials.

PhyloChip analysis

H2 addition narrowed the subfamily richness in the H2:CH4 FCC, revealed by the PhyloChip analysis, versus in the CH4 FCC. Adding excess H2 to an ecosystem adapted to high concentrations of methane and only traces of H2 narrowed the subfamily richness and markedly changed the species abundance (Supplementary Figure 4) compared with the in situ diversity reflected in the CH4 FCC. Bacterial subfamily richness was 199, 301 and 373 in the H2:CH4 × 4, CH4 × 4 and CH4 × 40 extraction samples, respectively, whereas archaeal subfamily richness was 3, 4 and 7, respectively (see Supplementary materials and methods, DNA extraction and concentration, for explanation of the × 4 and × 40 extractions). Methanomicrobiales and Methanosarcinales were present in all extractions in low but significant and comparable amounts. A larger percentage of Pseudomonadaceae appeared to be present in the CH4 × 40 than the CH4 × 4 sample, but a larger percentage of Pseudomonadaceae was present in the CH4 × 4 than the H2:CH4 × 4 sample. A larger percentage of Xanthomonadaceae was present in the H2:CH4 × 4 sample than in the other two samples; the H2:CH4 × 4 sample had no Micrococcaceae, whereas this family comprised 4% of the CH4 samples. The number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) in the Deltaproteobacteria class accounted for 3.9%, 4.0% and 2.7% of the OTUs in the H2:CH4 × 4, CH4 × 4 and CH4 × 40 samples, respectively. A circular tree showed that Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes OTUs varied in their abundance scores between the two treatments (Supplementary Figures 4 and 5). In particular, some of the largest differences were found for a Clostridium sequence (OTU 32005) that was much more abundant in the H2:CH4 than the CH4 samples and for Bacteroidales sequences (OTUs 46 869 and 47 213) that were much more abundant in the CH4 than the H2:CH4 samples. Large differences were evident in the Proteobacteria, as suggested by the different percentages of Pseudomonadaceae and Xanthomonadaceae in the samples. The tree consequently showed that most of the OTU abundance scores diverged between the CH4 and the H2:CH4 samples, that is, the different gas treatments resulted in different OTU abundances and diversities between the samples.

Discussion

Here, we present an in situ study of microbial metabolic activity in deep groundwater with hydrogen and methane as potential sources of energy and electron donors, and sulphate and Fe(III) as final electron acceptors. Adding hydrogen and methane induced the growth of NRB, SRB and AAs. The increase in these microbial numbers correlated with a marked reduction of sulphate to sulphide and the formation of acetate and DOC, as compared with an inactivated control. Supplementing the groundwater with methane alone similarly induced growth of NRB, SRB and AAs that correlated with the formation of acetate and DOC, but the reduction of sulphate was modest in comparison. IRB increased in numbers as did the concentration of ferrous iron in the methane-supplemented system.

The cultivation approach

It is often argued that most environmental micro-organisms cannot be cultured (Sharma et al., 2005). In this work, we successfully applied various culture procedures developed for the sampled environment (Vartoukian et al., 2010). The results of the MPN cultivation with the electron acceptors Fe(III), Mn(IV), NO3–, SO42– and CO2 and the electron donors H2, acetate and lactate indicated the presence of micro-organisms capable of iron, manganese, nitrate and sulphate reduction. The detection limit for the MPN analysis was 0.2 cells ml–1 (Greenberg et al., 1992), which makes this analysis very sensitive to cultivable micro-organisms. Here, the proportion of TNC detected using MPN analysis was >50% for NRB and SRB on several sampling occasions in the CH4 FCC and 10–50% on most other sampling occasions in the CH4 and the H2:CH4 FCCs. Consequently, the varied cultivation approach was successful, revealing that the microbial populations were dominated by cultivable micro-organisms capable of nitrate and sulphate reduction and of acetate formation in the CH4 and the H2:CH4 FCCs, and IRB and MRB were found in significant numbers in the CH4 FCC (Table 2). However, as many micro-organisms are facultative with respect to electron donors and acceptors, one cannot conclude the presence or absence of a metabolic process based solely on MPN results. The observed production of ferrous iron (Figure 3c), sulphide (Figure 3b) and acetate (Figure 4d) attests that the cultivated micro-organisms were active and expressed the metabolic activities that correlated with the MPN results. The MPN results were also in line with those for the original ONK-PVA06 groundwater, in which NRB was the dominant cultivable group of micro-organisms, followed by IRB and MRB (Table 1). It can be concluded that the CH4 FCC reproduced the growth conditions in the studied aquifer well, based on the similarity in the TNC, ATP, CHAB and MPN numbers. The increase in the MPN and metabolic activity of SRB in the CH4 and the H2:CH4 FCCs is discussed below.

Cell density control by bacteriophages

The presence of a viral mechanism for population control, similar in function to a viral shunt (Suttle, 2005), in deep groundwater was indicated in previous FCC experiments (Pedersen 2012a, 2012b). It was hypothesized that bacteriophages exerted a significant mitigating effect on the numbers of microbial cells and on the observed production rate of sulphide, but VLP data were not obtained. In this investigation, the VLP/TNC data indicated that bacteriophages increased from 0.2 to 5 and 9 bacteriophages cells–1 after day 20 in the CH4 and the H2:CH4 FCCs, respectively (Figure 2d), and that the TNC did not exceed 2.6 × 105 cells ml–1 in any of the FCCs. In contrast, VLPs were below detection in the O2:N2 FCC, which attests that the metabolic activity of micro-organisms in this system was likely inactivated by the O2 addition to a level at which lytic phage activity was arrested. Taken together, is seems safe to conclude that bacteriophages controlled the number of cells in this experiment, keeping it at a cell density within the range observed in deep Fennoscandian groundwater, that is, between 5 × 103 and 1 × 106 cells ml−1 (Pedersen et al., 2008; Hallbeck and Pedersen, 2012).

H2-induced sulphate reduction

The marked sulphate reduction induced by H2 was expected because many SRB have low half-saturation constants (Km) and maximum uptake rates (Vmax) for sulphate and hydrogen. For example, Sonne-Hansen et al. (1999) determined Km to be approximately 3 μℳ for sulphate and approximately 2 μℳ for H2 for two thermophilic SRB. That was in line with the constants determined for mesophilic SRB (Ks=1 μℳ) (Kristjansson et al. 1982; Robinson and Tiedje, 1984). These numbers suggest that the SRB metabolized at the maximum sulphate-reduction rate, Vmax, in the H2:CH4 FCC, because the sulphate and hydrogen concentrations were much higher than the respective Km values. The stable isotope fractionation data confirmed that biological sulphate reduction was present. Although there was an excess of H2 in this FCC, which would suggest a rapid increase in the numbers of SRB, these numbers did not increase above 5000 cells ml–1, likely because the cell density was controlled by bacteriophages (Eydal et al., 2009).

Methane-induced acetogenesis and sulphate reduction

AOM is suggested to proceed via several pathways with a range of final electron acceptors (Caldwell et al., 2008). Some of these pathways include the formation of acetate from methane (Valentine and Reeburgh, 2000). Both the CH4 and the H2:CH4 populations produced much more acetate and DOC than did the inactivated control (Figure 4d), and the produced acetate constituted about 1/3 of the DOC in both systems. The only available electron donor and source of reduced carbon that can explain the formation of organic carbon in these systems was methane. About 5 mℳ methane were consumed in the methane-amended systems, which more than balanced the amounts of DOC formed. If there was an AOM-driven metabolism, biomass should be formed as well; however, because phages were active (Figure 2d), a net increase in TNC or ATP was not observed (Figures 2a–c). Possibly, growing cells were lysed by phages and the released cytoplasmic material contributed to the increase in DOC concentration over time.

The PhyloChip indicated a limited presence of the typical AOM orders Methanomicrobiales and Methanosarcinales (Knittel and Boetius, 2009) in the rock grain biofilms; various groups of SRB were also indicated, but methanogens could not be cultured. AOM is assumed to involve methanotrophic Archaea and syntrophic partners, and the absence of a large representation of Archaea in the populations studied here could imply that the generally accepted AOM process (Knittel and Boetius, 2009) may not be relevant for the studied deep groundwater. An alternative possibility that merits more research could be unknown AOM consortia that include methanotrophic Bacteria such as Methylomirabilis oxyfera (Wu et al., 2011), but with other electron acceptors than NO2−, for example, Fe(III) or Mn(IV).

Implications for the SNF repository in Olkiluoto

The growth-stimulating effect of hydrogen on the investigated communities was expected because this gas is readily used by many different phylogenetic traits of anaerobic micro-organisms, such as SRB (Barton and Fauque, 2009), acetogens (Drake et al., 2002) and methanogens (Ferry, 1992). Regarding the anaerobic metabolism of methane, the situation is more obscure. Although AOM with sulphate as final electron acceptor is a well-documented process, detailed information about the metabolic pathways of AOM awaits successful cultures (Knittel and Boetius, 2009). The combined use of cultivation with microarrays and chemical analysis in the present work resulted in a large data set. As discussed above, the data indicated that methane was a source of electrons and energy for metabolic activity, possibly in combination with acetate formation and sulphate reduction, but clear evidence of such an AOM process was not obtained. However, the present data form a solid basis for designing future experiments on AOM with sulphate in deep Olkiluoto groundwater.

In the event that sulphate-rich groundwater penetrates to the SNF repository in Olkiluoto and mixes with deep, methane-rich groundwater, this work has demonstrated that there seems to be a potential for microbial sulphate reduction to sulphide via two metabolic processes. First, in addition to the naturally occurring hydrogen in Olkiluoto groundwater, iron in water-filled deep underground SNF constructions is bound to corrode anaerobically with the concomitant production of H2 (Reardon, 1995), which may induce SRB growth and sulphide production. Secondly, the in-mixing of sulphate-rich groundwater with the deep methane-rich groundwater at repository depth will induce SRB growth and activity. The electron donor is likely to be methane, but more research is required before conclusions can be drawn regarding the detailed nature and extent of an AOM process in Olkiluoto.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Johanna Arlinger, Andreas Bengtsson, Johanna Edlund, Lena Eriksson, Jessica Johansson, Linda Johansson, Anna Pääjärvi and Lisa Rabe at Microbial Analytics Sweden for their excellent laboratory work. The research leading to these results received funding from Posiva Oy and the European Union's European Atomic Energy Community's (Euratom) Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2007-2011 under grant agreement no. 212287 (RECOSY project).

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

Supplementary Material

References

- Aalto P, Aaltonen I, Ahokas H, Andersson J, Hakala M, Hellä P, et al. 2009. Sulphate reduction under deep bedrock conditions In:Programme for Repository Host Rock Characterisation in the ONKALO (ReRoC Posiva Working Report 2009-31: Posiva Oy: Eurajoki, Finland; 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C, Jakobsson A-M, Pedersen K. Influence of in situ biofilm coverage on the radionuclide adsorption capacity of subsurface granite. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:830–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton LL, Fauque GD. Biochemistry, physiology and biotechnology of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2009;68:41–98. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(09)01202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell SL, Laidler JR, Brewer EA, Eberly JO, Sandborgh SC, Colwell FS. Anaerobic oxidation of methane: mechanisms, bioenergetics and the ecology of associated microorganisms. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:6791–6799. doi: 10.1021/es800120b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Lu JR, Binder BJ, Liu YC, Hodson RE. Application of digital image analysis and flow cytometry to enumerate marine viruses stained with SYBR gold. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:539–545. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.2.539-545.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detmers J, Brüchert V, Habicht K, Kuever J. Diversity of sulphur isotope fractionations by sulphate-reducing prokaryotes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:888–894. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.2.888-894.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake HL, Küsel K, Matthies C. Ecological consequences of the phylogenetic and physiological diversities of acetogens. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2002;81:203–212. doi: 10.1023/a:1020514617738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eydal HSC, Jägevall S, Hermansson M, Pedersen K. Bacteriophage lytic to Desulfovibrio aespoeensis isolated from deep groundwater. ISME J. 2009;3:1139–1147. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eydal HSC, Pedersen K. Use of an ATP assay to determine viable microbial biomass in Fennoscandian Shield groundwater from depths of 3–1000m. J Microbiol Methods. 2007;70:363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry J. Biochemistry of methanogenesis. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1992;27:473–503. doi: 10.3109/10409239209082570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg AE, Clesceri LS, Eaton AD.1992Estimation of Bacterial Density Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater18th edn.American Public Health Association: Washington, DC; 9–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hallbeck L, Pedersen K. Characterization of microbial processes in deep aquifers of the Fennoscandian Shield. Appl Geochem. 2008;23:1796–1819. [Google Scholar]

- Hallbeck L, Pedersen K. Culture-dependent comparison of microbial diversity in deep granitic groundwater from two sites considered for a Swedish final repository of spent nuclear fuel. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2012;81:66–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazen TC, Dubinsky EA, DeSantis TZ, Andersen GL, Piceno YM, Singh N, et al. Deep-sea oil plume enriches indigenous oil-degrading bacteria. Science. 2010;330:204–208. doi: 10.1126/science.1195979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbie JE, Daley RJ, Jasper S. Use of nucleopore filters for counting bacteria by fluorescence microscopy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977;33:1225–1228. doi: 10.1128/aem.33.5.1225-1228.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knittel K, Boetius A. Anaerobic oxidation of methane: progress of an unknown process. Ann Rev Microbiol. 2009;63:311–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristjansson JK, Schönheit P, Thauer RK. Different Ks values for hydrogen of methanogenic bacteria and sulfate reducing bacteria: an explanation for the apparent inhibition of methanogenesis by sulfate. Arch Microbiol. 1982;131:278–282. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen ME, Pedersen K, Fisk M, Istok J. Microbial nitrate respiration of lactate at in situ conditions in groundwater from a granitic aquifer situated 450 m underground. Geobiology. 2006;4:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Noble RT, Fuhrman JA. Use of SYBR Green I for rapid epifluorescence counts of marine viruses and bacteria. Aquat Microb Ecol. 1998;14:113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen K.2005The MICROBE Framework: Site Descriptions, Instrumentation, and Characterization Äspö Hard Rock Laboratory, International Progress Report IPR-05-05; Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Co.Stockholm [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen K. Subterranean microbial populations metabolize hydrogen and acetate under in situ conditions in granitic groundwater at 450 m depth in the Äspö Hard Rock Laboratory, Sweden. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2012a;81:217–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2012.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen K. Influence of H2 and O2 on sulphate-reducing activity of a subterranean community and the coupled response in redox potential. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2012b;82:653–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2012.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen K, Arlinger J, Edlund J, Eriksson L, Lydmark S, Johansson J, et al. Microbiology of Olkiluoto and ONKALO Groundwater: Results and Interpretations, 2008–2009. Posiva Working report 2010-60: Posiva Oy: Eurajoki, Finland; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen K, Arlinger J, Hallbeck A, Hallbeck L, Eriksson S, Johansson J. Numbers, biomass and cultivable diversity of microbial populations relate to depth and borehole-specific conditions in groundwater from depths of 4 to 450 m in Olkiluoto, Finland. ISME J. 2008;2:760–775. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen K, Ekendahl S. Distribution and activity of bacteria in deep granitic groundwaters of southeastern Sweden. Microb Ecol. 1990;20:37–52. doi: 10.1007/BF02543865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon E. Anaerobic corrosion of granular iron: measurement and interpretation of hydrogen evolution rates. Environ Sci Technol. 1995;29:2936–2945. doi: 10.1021/es00012a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JA, Tiedje JM. Competition between sulfate-reducing and methanogenic bacteria for H2 under resting and growing conditions. Arch Microbiol. 1984;137:26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R, Ranjan R, Kapardar RK, Grover A. Unculturable bacterial diversity: an untapped resource. Curr Sci India. 2005;89:72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Sonne-Hansen J, Westermann P, Ahring BK. Kinetics of sulfate and hydrogen uptake by the thermophilic sulfate-reducing bacteria Thermodesulfobacterium sp. strain JSP and Thermodesulfovibrio sp. strain R1Ha3. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1304–1307. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.3.1304-1307.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttle CA. Virus in the sea. Nature. 2005;437:356–361. doi: 10.1038/nature04160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen TR, Finster K, Ramsing NB. Biogeochemical and molecular signatures of anaerobic methane oxidation in a marine sediment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:1646–1656. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.4.1646-1656.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toropainen V. Core Drilling of Drillholes ONK-PVA06 and ONK-PVA07 in ONKALO at Olkiluoto 2009. Working report 2009-121: Posiva Oy: Eurajoki, Finland; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine DL, Reeburgh WS. New perspectives on anaerobic methane oxidation. Environ Microbiol. 2000;2:477–484. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2000.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartoukian SR, Palmer RM, Wade WG. Strategies for culture of ‘unculturable' bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;309:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ML, Ettwig KF, Jetten MSM, Strous M, Keltjens JT, van Niftrik L. A new intra-aerobic metabolism in the nitrite-dependent anaerobic methane-oxidizing bacterium Candidatus ‘Methylomirabilis oxyfera'. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:243–248. doi: 10.1042/BST0390243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehnder A, Brock T. Anaerobic methane oxidation: occurrence and ecology. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;39:194–204. doi: 10.1128/aem.39.1.194-204.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.