Dear Editor,

The cryptochrome (CRY) flavoproteins are critical components of the mammalian molecular circadian clock, which operates through an auto-regulatory transcription-translation feedback loop1. In this clockwork, a pair of transcription factors, CLOCK and BMAL1, drive the expression of CRYs, Periods (PERs), and other clock-controlled genes, while CRYs and PERs heterodimerize and repress their own gene expression by inhibiting CLOCK-BMAL1-mediated transcription2,3. To establish rhythmic protein oscillation, CRYs are ubiquitinated by the SCFFBXL3 ubiquitin ligase and targeted for rapid proteasomal degradation4,5,6.

A recent cell-based screen of small-molecule circadian modulators identified three carbazole derivatives, which are characterized by their common dose-dependent circadian period-lengthening activity7. Further analyses have shown that the representative compound, KL001, acts by directly interacting with CRYs and protecting them from SCFFBXL3-mediated ubiquitination. This pharmacological activity results in CRY stabilization, which lengthens the circadian period.

Our recent studies have shown that CRY2-FBXL3 complex formation depends on the insertion of the FBXL3 C-terminal tail into the flavin adenosine dinucleotide (FAD)-binding pocket of the clock protein8. Because FAD can compete with both KL001 and FBXL3 for binding CRYs7, we postulated that KL001 might inhibit CRY ubiquitination by occupying its cofactor pocket and impairing its association with FBXL3. It is, however, equally possible that the small molecule binds at an allosteric site on CRYs.

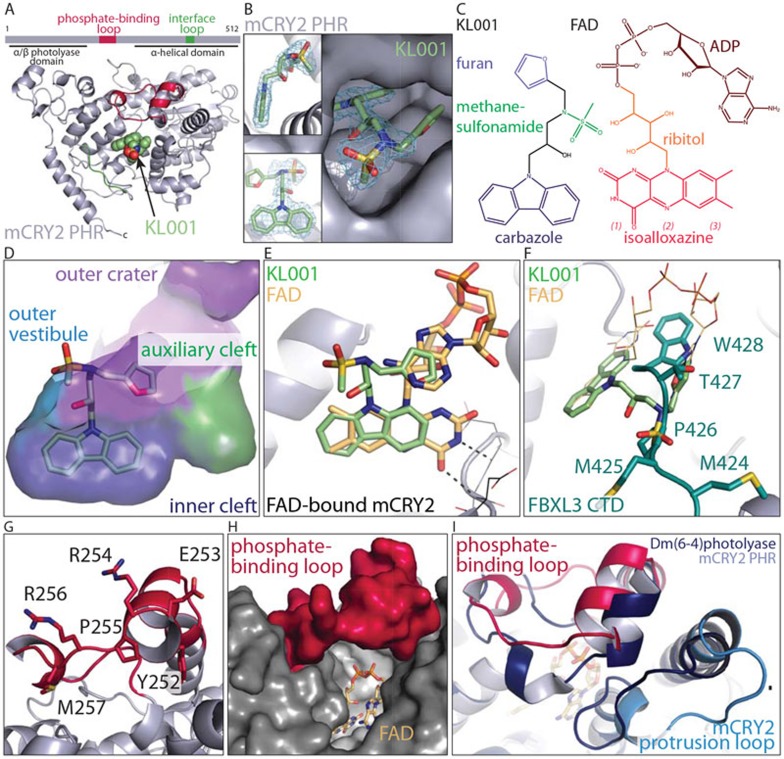

To unravel the binding mode of KL001, we co-purified and crystallized murine CRY2 PHR core domain (1-512) with KL001 and determined the complex structure at 1.94 Å resolution (Figure 1A and Supplementary information, Table S1). In the crystal, CRY2 adopts an overall structure nearly identical to its apo, FAD-bound, and FBXL3-complexed forms8. The largest conformational differences are limited to two local structural elements, namely the phosphate-binding loop and the interface loop (Figure 1A and Supplementary information, Figure S1). KL001 can be readily located in the FAD-binding pocket of CRY2. Clear density is found for the majority of the molecule except its furan moiety, which likely has a flexible conformation (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Structure of murine CRY2 in complex with KL001.(A) Overall structure of KL001-bound mCRY2 PHR domain. (B) Three close-up views of KL001 bound to CRY2 with positive Fo-Fc electron density contoured at 3.5 σ and calculated before the compound was built. (C) FAD and KL001 with their functional groups labeled. Subdivisions of the isoalloxazine ring: (1) pyrimidine, (2) pyrazine, (3) xylene. (D) Docking of the KL001 carbazole ring at the inner cleft (blue) of the FAD-binding pocket with the nearby auxiliary cleft (green), the outer crater (purple) and part of the outer vestibule shown. (E) A comparison of KL001 and FAD bound to CRY2. FAD is modeled onto the KL001-bound CRY2 (ribbon diagram) by CRY2 superposition. Two hydrogen bonds formed between the backbone of FAD-bound CRY2 (line representation) and the pyrimidine moiety of the FAD isoalloxazine ring are shown. (F) A different view of CRY2-bound KL001 in comparison with FAD (line representation) and the C-terminal tail of FBXL3 (teal). (G) Conformation of the ordered phosphate-binding loop of CRY2 with highly conserved but solvent exposed residues. (H) A model of FAD-bound CRY2 with an ordered phosphate-binding loop showing an open cofactor pocket. (I) A structural comparison between KL001-bound murine CRY2 (grey) and Drosophila(6-4)photolyase (dark blue) showing the phosphate-binding loop (pink in CRY2) and its nearby protrusion loop (light blue in CRY2). FAD is modeled in to replace KL001.

The CRY2 cofactor pocket can be subdivided into three parts: an inner cleft accommodating the FAD isoalloxazine moiety, an outer crater occupied by the ribitol and ADP moieties of FAD, and an auxiliary cleft, which is empty (Supplementary information, Figure S2). KL001 buries its carbazole ring deep into the inner cleft, indicating that the compound targets the clock protein as a cofactor mimic (Figure 1D). Despite their analogous tricyclic scaffolds (Figure 1C), however, the KL001 carbazole group sterically mimics the outer xylene and central pyrazine moieties of the FAD isoalloxazine ring instead of its entire tricyclic system (Figure 1E). Associated with this lateral shift of the carbazole ring, the rest of KL001 significantly deviates from the FAD cofactor. Instead of interacting with the outer crater, the methanesulfonamide group of KL001 is anchored at an outer vestibule of the FAD-binding pocket, where the FBXL3 C-terminal tail enters in the Skp1-FBXL3-CRY2 structure (Figure 1F and Supplementary information, Figure S2). Overall, the clock-modulating small molecule represents a molecular chimera — one half of it resembles part of the FAD cofactor and the other half sterically imitates the tail of the ubiquitin ligase. Based on previous studies showing that free FAD and point mutations of two inner cleft residues in CRY1, D387N and N393D (D405N and N411D in CRY2, Supplementary information, Figure S3), are each capable of abolishing KL001-CRY1 interaction7, the carbazole moiety of the compound likely plays a determining role in complex formation.

By stabilizing CRYs, KL001 has been shown to inhibit glucagon-induced gluconeogenesis in hepatocytes, suggesting a therapeutic potential for diabetes7. The CRY2-KL001 complex structure provides structural basis for further improving its potency. For example, functional groups can be introduced to one end of its carbazole ring to mimic the pyrimidine portion of the FAD isoalloxazine ring, which forms two hydrogen bonds with CRY2 (Figure 1E). Such modifications can be further extended to exploit the nearby auxiliary cleft of the FAD-binding pocket, which is enriched in polar amino acids. Although the methanesulfonamide group of KL001 is already snugly embedded in an induced pocket at the outer vestibule of the cofactor-binding site (Supplementary information, Figure S3), its adjacent flexible furan moiety presents yet another opportunity for compound optimization.

Distinct from non-vertebrate cryptochromes and their closely related DNA photolyases, mammalian CRYs feature an open and dynamic FAD-binding pocket characterized by a flexible phosphate-binding loop and a moderate affinity of FAD binding8,9. Unexpectedly, our structure reveals an ordered phosphate-binding loop, which adopts a well-defined conformation in the crystal (Figure 1G). When modeled onto the structure of FAD-bound CRY2, this ordered loop is still well removed from the cofactor (> 5.3 Å) and the FAD-binding pocket remains largely open to the solvent (Figure 1H). By contrast, the same loop in Drosophila (6-4)photolyase, which shares a sequence identity of 53% with CRY2, folds into a lid and traps the cofactor within the pocket as a prosthetic group (Figure 1I)10.

Because the phosphate-binding loop is located at the opposite end of the FAD-binding pocket to KL001 (Figure 1G), its ordered structure is likely attributable to crystal packing instead of compound binding. Indeed, crystal analysis shows that the phosphate-binding loop is in close contact with a C-terminal Tyr residue from an adjacent molecule, which approaches the FAD-binding pocket under the loop (Supplementary information, Figure S4). In conjunction with its strictly conserved sequence among vertebrate orthologs (Supplementary information, Figure S5), the structural sensitivity of the phosphate-binding loop to its immediate environment implicates an important role in protein-protein interactions. We speculate that these interactions might increase the affinity of FAD and enable the cofactor to regulate the activity and possibly stability of CRYs, in a manner analogous to the function of the Drosophila cryptochrome C-terminal tail9,11.

KL001 is the first-in-class cryptochrome-targeting circadian modulator and substrate-targeting ubiquitination antagonist. The crystal structure of the CRY2-KL001 complex not only reveals its novel mechanism of action as a cofactor-mimicking interfacial inhibitor but also makes further development possible to realize its full therapeutic potential.

Acknowledgments

We thank the beamline staff of the Advanced Light Source at the University of California at Berkeley and Advanced Photon Source of Argonne National Laboratory for help with data collection, and members of the Zheng laboratory for discussion. This work is supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (NZ) and the National Institutes of Health (R01-CA107134 to NZ, and T32-GM007750 to SN).

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Information

Superposition analyses of murine CRY2 PHR domain structures.

Subdivision of the FAD-binding pocket of murine CRY2.

KL001-binding site on murine CRY2.

Stabilization of mCRY2 phosphate-binding loop by crystal packing.

Sequence alignment of cryptochrome phosphate-binding loop.

Data collection and refinement statistics

References

- Reppert SM, Weaver DR. Nature. 2002. pp. 935–941. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shearman LP, Sriram S, Weaver DR, et al. Science. 2000. pp. 1013–1019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lee C, Etchegaray JP, Cagampang FR, et al. Cell. 2001. pp. 855–867. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Busino L, Bassermann F, Maiolica A, et al. Science. 2007. pp. 900–904. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Godinho SI, Maywood ES, Shaw L, et al. Science. 2007. pp. 897–900. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Siepka SM, Yoo SH, Park J, et al. Cell. 2007. pp. 1011–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hirota T, Lee JW, St John PC, et al. Science. 2012. pp. 1094–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Xing W, Busino L, Hinds TR, et al. Nature. 2013. pp. 64–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Czarna A, Berndt A, Singh HR, et al. Cell. 2013. pp. 1394–1405. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Maul MJ, Barends TR, Glas AF, et al. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008. pp. 10076–10080. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zoltowski BD, Vaidya AT, Top D, et al. Nature. 2011. pp. 396–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Superposition analyses of murine CRY2 PHR domain structures.

Subdivision of the FAD-binding pocket of murine CRY2.

KL001-binding site on murine CRY2.

Stabilization of mCRY2 phosphate-binding loop by crystal packing.

Sequence alignment of cryptochrome phosphate-binding loop.

Data collection and refinement statistics