Abstract

Background:

It is unclear whether participation in a randomized controlled trial (RCT), irrespective of assigned treatment, is harmful or beneficial to participants. We compared outcomes for patients with the same diagnoses who did (“insiders”) and did not (“outsiders”) enter RCTs, without regard to the specific therapies received for their respective diagnoses.

Methods:

By searching the MEDLINE (1966–2010), Embase (1980–2010), CENTRAL (1960–2010) and PsycINFO (1880–2010) databases, we identified 147 studies that reported the health outcomes of “insiders” and a group of parallel or consecutive “outsiders” within the same time period. We prepared a narrative review and, as appropriate, meta-analyses of patients’ outcomes.

Results:

We found no clinically or statistically significant differences in outcomes between “insiders” and “outsiders” in the 23 studies in which the experimental intervention was ineffective (standard mean difference in continuous outcomes −0.03, 95% confidence interval [CI] −0.1 to 0.04) or in the 7 studies in which the experimental intervention was effective and was received by both “insiders” and “outsiders” (mean difference 0.04, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.13). However, in 9 studies in which an effective intervention was received only by “insiders,” the “outsiders” experienced significantly worse health outcomes (mean difference −0.36, 95% CI −0.61 to −0.12).

Interpretation:

We found no evidence to support clinically important overall harm or benefit arising from participation in RCTs. This conclusion refutes earlier claims that trial participants are at increased risk of harm.

When people are asked to participate in a randomized controlled trial (RCT), it is natural for them to ask several questions in return. How safe are these treatments? How many extra visits and tests must I undergo? Will the researchers keep my family doctor informed about what’s going on? What outcomes are to be measured, and do they include ones that are of interest to me as a patient?

These multiple questions can be summarized as follows: Would I fare better being treated within the trial (as an “insider”) or in routine clinical care outside it (as an “outsider”)? Patients may ask this question in 1 of 2 ways. The first is highly specific: “Am I better off receiving this specific treatment as an insider or as an outsider?” Alternatively, they might ask a more general question: “Am I better off having my illness managed, regardless of the specific treatment I would receive, as an insider or as an outsider?” These questions are highly appropriate, and both deserve to be asked and answered,1,2 especially given that nonsystematic reviews have suggested a possible “inclusion benefit” from participating in trials.3

These 2 specific patient questions are analogous to those posed by researchers asking whether treatments do more good than harm when applied under “ideal” circumstances (in explanatory trials) or in the “real world” of routine health care (in pragmatic trials). Vist and colleagues answered the explanatory question when their earlier review4 found no advantage or disadvantage from receiving the same treatment inside or outside an RCT. Left unanswered, however, was the broader, more pragmatic question. In our experience, trial participants are often offered new, as-yet-untested treatments that would not be available to them outside the trial. This review looks at the dilemma faced by these patients, which needs to be addressed before general conclusions can be drawn about trial safety.

Methods

Data sources and searches

We searched the following databases: MEDLINE (1966 to November 2010), Embase (1980 to November 2010), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 1960 to last quarter of 2010) and PsycINFO (1880 to November 2010). The search strategy for each database is available upon request to the corresponding author. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they reported the same set of outcomes for “insiders” and “outsiders,” either simultaneously or within 2 months, where “insiders” were patients with a particular diagnosis who entered an RCT (whether treated with the intervention or a comparator) and “outsiders” were patients with the same diagnosis who did not enter the RCT. To validate our search, we compared our yield with the list of articles reviewed by Vist and colleagues.4

Study selection

Working in pairs, we reviewed the resulting titles and abstracts to screen for eligibility. Two reviewers independently screened the full text of eligible articles, with an independent third adjudicator resolving disagreements. Agreement was summarized with a weighted kappa coefficient.

Data extraction

Our primary outcome was mortality, and secondary outcomes included patient-reported or other clinically important outcomes. We calculated the relative risk (RR), unless count data were not reported, in which case we extracted the authors’ RR. We used adjusted RRs whenever they were reported.5 When RRs could not be calculated, we assumed that the reported odds ratios (ORs) approximated the RR for low event-rate outcomes.

For continuous outcomes, we extracted mean between-group differences and their standard deviations. We created rules for calculating missing outcomes using various statistical measures that were reported (Table 1).

Table 1:

Assumptions and imputations used to calculate data if missing from published report

| Data needed | Data available | Assumptions/imputations |

|---|---|---|

| SD of the difference | SE of the difference | Multiply SE by square root of sample size |

| Confidence interval around the difference | For n ≥ 100, assume standard normal distribution For n < 100, assume t distribution |

|

| SE of the difference | p value for mean difference | Convert p value to t value at same degrees of freedom; divide mean difference by t value |

| Final score | Baseline and change scores | Add or subtract the change score from baseline value |

| SD of final scores | SD of baseline and change scores | Sum baseline and change variances |

| SD | Range | No appropriate conversion possible |

Note: SD = standard deviation, SE = standard error.

Prespecified causes of heterogeneity

We used the I2 statistic to measure the extent of heterogeneity between studies, where I2 values of 25%, 50% and 75% indicated low, medium and high heterogeneity, respectively.6 In addition, we constructed a priori hypotheses to potentially explain between-study heterogeneity, based on differences in types of outcomes, methodologic quality, types of care provided, potential for detection bias (due to differential follow-up or use of better diagnostic tools), potential for exclusion bias (if patients were excluded after enrolment because of characteristics related to outcome), potential for selection bias (due to imbalance of baseline characteristics), medical specialty and treatments provided.

In particular, we proposed 6 subgroups to explain observed heterogeneity due to treatment effect:

when the randomized experimental intervention given to “insiders” was effective (i.e., the outcome was statistically significantly superior to the comparator), and “outsiders” received that same intervention or comparator

when the randomized experimental intervention was effective, and “outsiders” received that same effective intervention only (without the comparator that was provided within the RCT)

when the randomized experimental intervention was effective, and “outsiders” received the less effective comparator intervention only (without the experimental intervention provided within the RCT)

when the randomized experimental intervention was effective, and “outsiders” received a different intervention (this subgroup acted as a positive control for the current analysis, since we anticipated better outcomes in the RCT group)

when the randomized experimental and comparator interventions generated equivalent outcomes, with no further subdivision of this group (because any differences in outcomes between those treated inside and outside the RCT could be attributed to a trial effect)

when insufficient information was provided about the effectiveness of the treatment in the trial and/or insufficient details were provided about the interventions received by “outsiders”

Data synthesis and analysis

Statistical calculations were performed with SPSS (version 20).7 Forest plots and funnel plots were created using Review Manager (version 5.1).8 When event counts were available, we used the Mantel–Haenszel method to estimate overall RR.9 If a study had a zero event rate in one group, we added a 0.5 correction to all cells. If only estimates of effect size and standard errors were provided, we used the generic inverse-variance meta-analysis function of Review Manager 5.1. We used the random-effects model to summarize outcomes.9

We first separated the studies into 2 groups according to whether randomization was applied in determining whether potential participants would be “insiders” or “outsiders.” Next, we separated studies by type of outcome: continuous or dichotomous, with the latter being further subdivided as nonmortality or mortality.

We created a funnel plot and conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine the stability of our conclusions.

Results

Summary of evidence

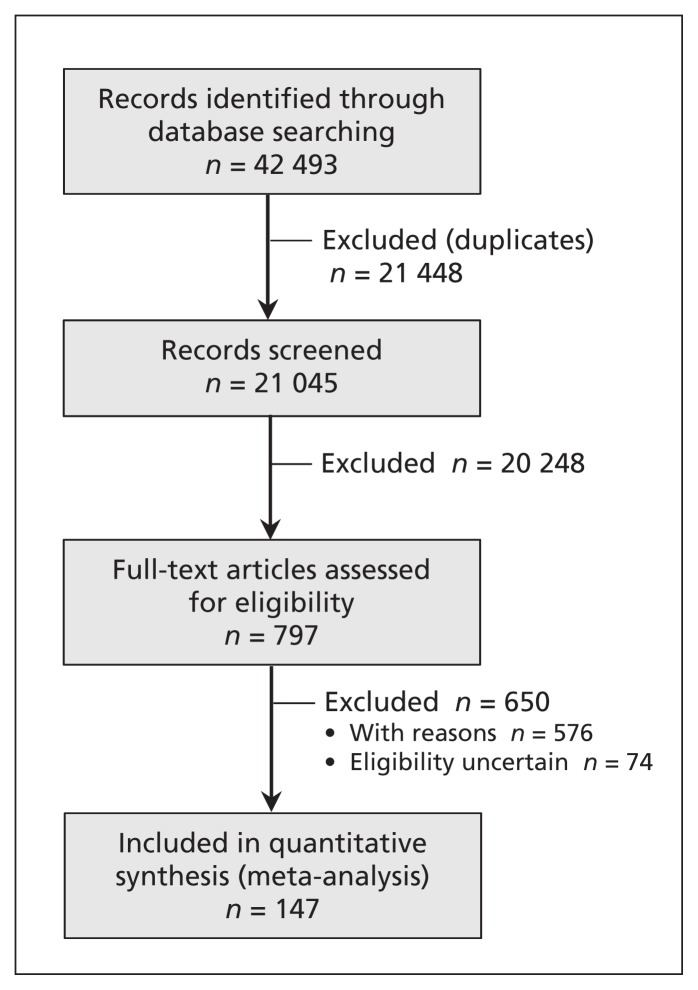

Following elimination of duplicate records and exclusions on the basis of initial screening and full-text review, 147 articles met our eligibility criteria and provided sufficient information to be included in our analysis (Figure 1).10–156 Details for the 576 articles excluded after full-text review, including reasons for exclusion, are available upon request. The eligibility of the remaining 74 articles was uncertain, and they were not included in the analysis.

Figure 1:

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow chart of studies identified and included in the analysis.10–156 The reasons for exclusions at screening and full-text review are available upon request to the corresponding author.

For full-text screening, the calculated average of the weighted kappa for eligibility was 0.68. There was 83% raw agreement between reviewers in the data-extraction phase for outcomes.

In 5 of the 147 eligible studies, patients were randomly assigned to become “insiders” and “outsiders.”38,41,86,87,141 In the remaining 142 studies, patients became part of the “outsiders” group for a variety of reasons. Table 2 presents the details about each included study.

Table 2:

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | No. of “insiders” | No. of “outsiders” | Specialty | Intervention | Care setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akaza et al. 199510 | 107 | 13 | Oncology | Vaccination | Hospital |

| Amar et al. 199711 | 70 | 40 | Surgery | Anti-arrhythmic drugs | Hospital |

| Andersson et al. 200312 | 24 | 8 | Family | Counselling | Home |

| Antman et al. 198513 | 42 | 42 | Oncology | Chemotherapy | Cancer centre |

| Ashok et al. 200214 | 229 | 45 | Ob/gyn | Abortion | Hospital |

| Bain et al. 200115 | 36 | 62 | Anesthesia | Sedatives | Operating room |

| Bakker et al. 200016 | 113 | 24 | Psychiatry | Counselling | Outpatient clinic |

| Balmukhanov et al. 198917 | 108 | 287 | Oncology | Radiation | Hospital |

| Bannister et al. 200118 | 202 | 38 | Anesthesia | Analgesics | Operation room |

| Bedi et al. 200019 | 85 | 164 | Family | Counselling | Family clinic |

| Bell and Palma 200020 | 59 | 56 | Ob/gyn | Exercise program | Unclear |

| Bhattacharya et al. 199821 | 92 | 68 | Ob/gyn | Longer hospital stay | Hospital |

| Biasoli et al. 200822 | 52 | 41 | Oncology | Chemotherapy | Hospital |

| Biederman et al. 198523 | 24 | 18 | Psychiatry | Drugs | Inpatient |

| Bijker et al. 200224 | 268 | 155 | Oncology | Excision | Unclear |

| Blichert-Toft et al. 198825 | 619 | 136 | Oncology | Mastectomy | Surgical departments |

| Blumenthal et al. 199726 | 66 | 38 | Cardiology | Exercise | Hospital |

| Boesen et al. 200727 | 258 | 137 | Oncology | Psychoeducation | Outpatient clinic |

| Boezaart et al. 199828 | 240 | 136 | Anesthesia | Drugs | Private hospital |

| Brinkhaus et al. 200829 | 902 | 3 888 | Allergy | Acupuncture | Unclear |

| Caplan and Buchanan 198430 | 29 | 46 | ID | Drugs | Hospital |

| CASS 198431 | 779 | 1 309 | Cardiology | Surgery | Unclear |

| Chauhan et al. 199232 | 38 | 15 | Ob/gyn | Amnio-infusion | Labour unit |

| Chesebro et al. 198333 | 351 | 183 | Internal | Anticoagulant | Unclear |

| Chilvers et al. 200134 | 98 | 207 | Family | Counselling v. drugs | Outpatient |

| Clagett et al. 198435 | 29 | 28 | Surgery | Surgery | Unclear |

| Clapp et al. 198936 | 115 | 85 | ID | Drugs | Pediatric hospital |

| Clemens et al. 199237 | 20 744 | 21 943 | ID | Vaccine | Research centre |

| Cooper et al. 199738 | – | – | Ob/gyn | Surgery | Hospital |

| Cowchock et al. 199239 | 20 | 13 | Ob/gyn | Drugs | Unclear |

| Creutzig et al. 199340 | 31 | 25 | Oncology | Radiation | Unclear |

| Dahan et al. 198641 | – | – | Research design | Informed consent | Unclear |

| Dalal et al. 200742 | 100 | 84 | Cardiology | Rehabilitation | Hospital, home |

| Decensi et al. 200343 | 116 | 29 | Oncology | Drugs | Hospital |

| Detre et al. 199944 | 343 | 299 | Cardiology | Surgery | Hospital |

| Eberhardt et al. 199646 | 43 | 37 | Rheumatology | Drugs | Hospital |

| Edsmyr et al. 197847 | 18 | 9 | Urology | Drugs | Unclear |

| Ekstein et al. 200248 | 91 | 1 202 | Cardiology | Surgery | Hospital |

| Emery et al. 200349 | 168 | 49 | Ob/gyn | Counselling | Hospital |

| Euler et al. 200550 | 58 | 14 | Pediatrics | Diet | Unclear |

| Feit et al. 200051 | 1 169 | 1 336 | Cardiology | Surgery | Hospital |

| Forbes and Collins 200052 | 102 | 88 | Gastrointestinal | Drugs | Hospital |

| Franz et al. 199553 | 179 | 62 | Nutrition | Diet | Unclear |

| Gall et al. 200754 | 46 | 41 | Gastrointestinal | Follow-up | Hospital |

| Girón et al. 201055 | 24 | 45 | Psychiatry | Family intervention | Mental health centre |

| Goodkin et al. 198756 | 27 | 24 | Neurology | Drugs | Unclear |

| Gossop et al. 198657 | 20 | 40 | Addiction | Inpatient treatment | Unclear |

| Grant et al. 200858 | 299 | 375 | Gastrointestinal | Surgery | Hospital |

| Gunn et al. 200059 | 122 | 308 | Pediatrics | Home support | Hospital |

| Helsing et al. 199860 | 47 | 97 | Oncology | Supportive care | Unclear |

| Henriksson and Edhaq 198661 | 91 | 9 | Urology | Surgery | Unclear |

| Heuss et al. 200462 | 74 | 40 | Gastrointestinal | Sedation | Hospital |

| Hoh et al. 199863 | 13 | 39 | Nutrition | Diet | Hospital |

| Howard et al. 200964 | 44 | 28 | Psychiatry | Crisis houses | Hospital |

| Howie et al. 199765 | 77 | 63 | Ob/gyn | Abortion | Hospital |

| Jena et al. 200866 | 2 792 | 10 410 | Alternative | Acupuncture | Unclear |

| Jensen et al. 200367 | 897 | 294 | Geriatrics | Hormones | Hospital |

| Kane 198868 | 59 | 116 | Orthopedics | Bone growth stimulator | Unclear |

| Karande et al. 199969 | 63 | 57 | Ob/gyn | IVF | Infertility clinic |

| Kayser et al. 200870 | 31 | 44 | Travel | Drugs | Unclear |

| Kendrick et al. 200171 | 394 | 50 | Technology | Radiography | General practice or hospital |

| Kieler et al. 199872 | 526 | 4 801 | Ob/gyn | Ultrasonography | Antenatal care clinic |

| King et al. 200073 | 165 | 106 | Psychiatry | Counselling | Unclear |

| Kirke et al. 199274 | 351 | 106 | Ob/gyn | Folic acid | Unclear |

| Koch-Henriksen et al. 200675 | 224 | 74 | Neurology | Drugs | Unclear |

| Lansky and Vance 198376 | 55 | 59 | Psychology | Diet and exercise | Unclear |

| Lichtenberg et al. 200877 | 217 | 153 | Psychiatry | Case management | Unclear |

| Lidbrink et al. 199578 | 20 000 | 7 785 | Oncology | Mammography | Unclear |

| Link et al. 199179 | 36 | 77 | Oncology | Drugs | Unclear |

| Liu et al. 200980 | 169 | 163 | Alternative | Salvia | Delivery room |

| Lock et al. 201081 | 40 | 303 | Surgery | Tonsillectomy | ENT department |

| Loeffler et al. 199745 | 100 | 21 | Oncology | Radiotherapy | Hospital |

| Luby et al. 200282 | 162 | 79 | ID | Antibacterial soap | Home |

| Macdonald et al. 200783 | 5 | 48 | Nephrology | Drugs | Unclear |

| MacLennan et al. 198584 | 96 | 73 | Ob/gyn | Relaxin | IVF clinic |

| MacMillan et al. 198685 | 107 | 49 | Psychiatry | Drugs | Unclear |

| Mahon et al. 199686 | – | – | Respirology | Drugs | Hospital |

| Mahon et al. 199987 | – | – | Respirology | Drugs | Primary care |

| Marcinczyk et al. 199788 | 54 | 29 | Vascular surgery | Endarterectomy | Hospital |

| Martin 199489 | 46 | 54 | Gastrointestinal | Antacid | Hospital |

| Martínez-Amenos et al. 199090 | 589 | 133 | Family | Education | Primary care |

| Masood et al. 200291 | 96 | 14 | Urology | Nitrous oxide – oxygen | Urology department |

| Matilla et al. 200392 | 137 | 166 | ENT | Surgery | Study clinic |

| Mayo Group 199293 | 71 | 87 | Vascular surgery | Endarterectomy | Unclear |

| McCaughey et al. 199894 | 19 | 13 | Pediatrics | Hormone | Hospital |

| McKay et al. 199895 | 101 | 51 | Psychology | Day hospital | Hospital |

| McKay et al. 199596 | 40 | 80 | Psychology | Day hospital | Addiction recovery unit |

| Melchart et al. 200297 | 26 | 80 | Alternative | Acupuncture | Hospital |

| Moertel et al. 198498 | 62 | 10 | Oncology | Chemo + radiation | Hospital |

| Mori et al. 200699 | 712 | 158 | Gastrointestinal | Endoscopy | Hospital |

| Morrison et al. 2002100 | 454 | 302 | Cardiology | Surgery | Hospital |

| Nagel et al. 1998101 | 115 | 95 | Ob/gyn | Amniocentesis | Hospital |

| Neldam et al. 1986102 | 978 | 349 | Ob/gyn | Fetal heart monitor | Hospital |

| Nicolaides et al. 1994103 | 488 | 812 | Ob/gyn | Chorionic villus sampling | Research centre |

| Ogden et al. 2004104 | 285 | 47 | Orthopedics | Shock wave treatment | Unclear |

| Palmon et al. 1996105 | 50 | 10 | Critical care | Carbon dioxide monitor | Neuroradiology centre |

| Panagopoulou et al. 2009106 | 148 | 66 | Psychology | Diary writing | Clinic |

| Paradise et al. 1984107 | 42 | 28 | Surgery | Tonsillectomy | Hospital |

| Petersen et al. 2007108 | 79 | 33 | Orthopedics | Hip replacement | Hospital |

| Raistrick et al. 2005109 | 174 | 225 | Addiction | Drugs | Addiction recovery unit |

| Reddihough et al. 1998110 | 19 | 22 | Physiotherapy | Education | Unclear |

| Rigg et al. 2000111 | 455 | 237 | Anesthesia | Analgesia | Hospital |

| Rørbye et al. 2005112 | 105 | 727 | Ob/gyn | Abortion | Hospital |

| Rosen et al. 1987113 | 98 | 44 | Anesthesia | Nitrous oxide | Hospital |

| Salisbury et al. 2002114 | 253 | 129 | Family | School-based clinics | Unclear |

| Sesso et al. 2002115 | 22 071 | 11 152 | Cardiology | ASA | Unclear |

| Shain et al. 1989116 | 155 | 98 | Ob/gyn | Contraception | Unclear |

| Smith and Arnesen 1990117 | 1 214 | 270 | Internal | Warfarin | Cardiology centre |

| Smuts et al. 2003118 | 16 | 37 | Pediatrics | Diet | Unclear |

| Stecksén-Blicks et al. 2008119 | 115 | 64 | Dentistry | Lozenges | Clinic |

| Stern et al. 2003120 | 555 | 1 788 | Ob/gyn | Anticoagulants | Hospital |

| Stith et al. 2004121 | 19 | 4 | Psychology | Couple therapy | Unclear |

| Stockton and Mengersen 2009122 | 57 | 21 | Rehab | Physiotherapy | Hospital |

| Strandberg et al. 1995123 | 910 | 489 | Cardiology | Health checks | Hospital |

| Suherman et al. 1999124 | 83 | 29 | Ob/gyn | Contraception | Unclear |

| Sullivan et al. 1982125 | 144 | 25 | Oncology | Radiotherapy | Unclear |

| Sundar et al. 2008126 | 136 | 45 | ID | Drugs | Inpatient unit |

| Taddio et al. 2006127 | 98 | 20 | Pediatrics | Analgesics | Hospital |

| Tanai et al. 2009128 | 100 | 19 | Oncology | Drugs | Hospital |

| Tanaka et al. 1994129 | 30 | 10 | Anesthesia | Drugs | Unclear |

| Taplin et al. 1986130 | 63 | 30 | Dermatology | Permethrin cream | Unclear |

| Tenenbaum et al. 2002131 | 3 122 | 380 | Cardiology | Drugs | Hospital |

| Toprak et al. 2005132 | 30 | 15 | Ob/gyn | Hormone replacement | Clinic |

| Underwood et al. 2008133 | 187 | 271 | Geriatrics | Ibuprofen | Primary care |

| Urban et al. 1999134 | 55 | 24 | Cardiology | Early revascularization | Unclear |

| Van et al. 2009136 | 40 | 45 | Psychiatry | Therapy | Unclear |

| van Bergen et al. 1995135 | 350 | 587 | Cardiology | Anticoagulant | Centre |

| Verdonck et al. 1995137 | 69 | 37 | Oncology | Chemotherapy | Unclear |

| Vind et al. 2009138 | 256 | 297 | Geriatrics | Fall prevention | Unclear |

| Walker et al. 1986139 | 98 | 37 | Surgery | Antibiotics | Unclear |

| Wallage et al. 2003140 | 178 | 28 | Ob/gyn | Anesthesia | Hospital |

| Watzke et al. 2010141 | 180 | 97 | Psychiatry | Counselling | Inpatient unit |

| Welt et al. 1981142 | 23 | 40 | Ob/gyn | Drugs | Unclear |

| West et al. 2005143 | 86 | 322 | Critical care | Magnesium sulphate | Unclear |

| Wetzner et al. 1979144 | 34 | 64 | Radiology | Contrast | Unclear |

| Wieringa-de Waard et al. 2002146 | 122 | 305 | Ob/gyn | Evacuation | Clinic |

| Williford et al. 1993147 | 395 | 199 | Nutrition | Diet | Unclear |

| Witt et al. 2006a148 | 543 | 2 481 | Alternative | Acupuncture | Unclear |

| Witt et al. 2006b149 | 3 036 | 4 686 | Alternative | Acupuncture | Unclear |

| Witt et al. 2006c150 | 2 518 | 3 901 | Alternative | Acupuncture | Unclear |

| Witt et al. 2008151 | 57 | 21 | Alternative | Acupuncture | Unclear |

| Woodhouse et al. 1995152 | 194 | 145 | Cardiology | Adrenaline dose | Hospital |

| World Health Organization 1988145 | 40 | 32 | Ob/gyn | Contraception | Unclear |

| Wyse et al. 1991153 | 1 672 | 318 | Cardiology | Anti-arrhythmic drugs | Unclear |

| Yamamoto et al. 1992154 | 31 | 92 | Gastrointestinal | Esophageal dilator | Unclear |

| Yamani et al. 2005155 | 23 | 33 | ID | Vaccine | Unclear |

| Yersin et al. 1996156 | 20 | 10 | Addiction | Counselling | Unclear |

Note: ASA = acetylsalicylic acid, CASS = Coronary Artery Surgery Study, chemo = chemotherapy, ENT = ear, nose and throat, Family = family medicine, ID = infectious diseases, “insider” = patient receiving treatment within a randomized controlled trial, IVF = in vitro fertilization, Ob/gyn = obstetrics and gynecology, “outsider” = patient receiving treatment via routine clinical care outside the randomized controlled trial.

We analyzed a total of 48 continuous outcomes and 99 dichotomous outcomes; of the dichotomous outcomes, 74 were nonmortality outcomes, 4 were recurring outcomes (such as relapse rates), and 21 were mortality outcomes.

Risk of bias

Sources of risk of bias are detailed by individual study in Appendix 1 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.131693/-/DC1). In terms of detection bias, about two-thirds of the studies (n = 100) employed identical follow-up strategies for “insiders” and “outsiders.” In terms of exclusion bias affecting “insiders,” 67 studies had no exclusions, 1 study employed a deliberate but appropriate exclusion, and 74 studies inappropriately excluded “insiders” unequally between treatment groups; for the remaining 5 studies, the details were unclear. Forest plots based on subgroups created for each of these sources of bias did not change the results described below.

Replication of earlier studies

As a method of calibrating our search strategies and statistical methods, we carried out analyses of our dataset that were restricted to “insiders” and “outsiders” receiving identical treatments. These restricted analyses replicated the results of previous studies by Vist and colleagues4 and Gross and associates.157

Outcomes for studies with participants not randomized as “insiders” or “outsiders”

Our initial pooled analyses revealed a high degree of between-study heterogeneity (p < 0.001, I 2 = 84% for studies with dichotomous mortality outcomes; p < 0.001, I2 = 70% for studies with dichotomous nonmortality outcomes; p < 0.001, I 2 = 88% for studies with continuous outcomes). In total, mortality was determined for 53 714 “insiders” and 25 817 “outsiders” (see Table 3 and Appendix 2, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.131693/-/DC1). Dichotomous nonmortality outcomes were reported for 30 253 “insiders” and 30 000 “outsiders” (see Table 4 and Appendix 3, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.131693/-/DC1). We present the results of our nonrandomized continuous outcomes and randomized comparisons according to treatment effects, by presenting the subgrouping that left the least amount of remaining heterogeneity. All other forest plots are available upon request.

Table 3:

Summary of meta-analyses for studies with mortality as an outcome, without randomization of potential participants as “insiders” v. “outsiders” (subgroups based on effectiveness of trial treatment)

| Subgroup | No. of trials | No. of events/no. of patients | Weight, % | RR (95% CI) | I2, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT | Cohort | |||||

| Trial treatment effective, same treatment and comparator given to “outsiders” | 3 | 273/2 000 | 251/2 447 | 15.2 | 1.30 (0.78 to 2.16) | 79 |

| Trial treatment effective, treatment only given to “outsiders” | 1 | 39/47 | 76/97 | 7.0 | 1.06 (0.90 to 1.25) | NA |

| Trial treatment effective, comparator only given to “outsiders” | 1 | 53/62 | 7/10 | 5.0 | 1.22 (0.80 to 1.86) | NA |

| Trial treatment effective, neither treatment nor comparator given to “outsiders” | 2 | 377/2 124 | 116/759 | 12.4 | 1.13 (0.43 to 2.94) | 96 |

| Trial treatment ineffective | 9 | 478/22 306 | 472/10 328 | 44.2 | 0.73 (0.50 to 1.05) | 92 |

| Trial effect or treatment given unknown | 5 | 640/27 175 | 192/12 176 | 16.2 | 0.83 (0.59 to 1.18) | 60 |

| Overall | 21 | 1 860/53 714 | 1 114/25 817 | 100.0 | 0.92 (0.78 to 1.07) | 84 |

Note: CI = confidence interval, NA = not applicable, RCT = randomized controlled trial, RR = relative risk.

Table 4:

Summary of meta-analyses for studies with dichotomous nonmortality outcomes, without randomization of potential participants as “insiders” v. “outsiders” (subgroups based on effectiveness of trial treatment)

| Subgroup | No. of trials | No. of patients | Weight, % | RR (95% CI) | I2, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT | Cohort | |||||

| Trial treatment effective, same treatment and comparator given to “outsiders” | 9 | 1 316 | 1 768 | 11.9 | 1.06 (0.81 to 1.40) | 54 |

| Trial treatment effective, treatment only given to “outsiders” | 3 | 382 | 168 | 4.6 | 1.68 (0.80 to 3.56) | 84 |

| Trial treatment effective, comparator only given to “outsiders” | 1 | 589 | 133 | 3.3 | 0.76 (0.62 to 0.92) | NA |

| Trial treatment effective, neither treatment nor comparator given to “outsiders” | 6 | 369 | 269 | 8.0 | 0.99 (0.61 to 1.63) | 77 |

| Trial treatment ineffective | 37 | 5 513 | 4 915 | 60.3 | 0.96 (0.89 to 1.04) | 58 |

| Trial effect or treatment given unknown | 13 | 22 084 | 22 747 | 12.0 | 1.06 (0.65 to 1.70) | 83 |

| Overall | 69 | 30 253 | 30 000 | 100.0 | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.08) | 70 |

Note: CI = confidence interval, NA = not applicable, RCT = randomized controlled trial, RR = relative risk.

Results for clinically relevant subgroups

The results for continuous outcomes are summarized by subgroup in Table 5 (see also Appendix 4, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.131693/-/DC1).

Table 5:

Summary of meta-analyses for studies with continuous outcomes, without randomization of potential participants as “insiders” v. “outsiders” (subgroups based on effectiveness of trial treatment)

| Subgroup | No. of trials | No. of patients | Weight, % | Standardized mean difference (95% CI) | I2, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT | Cohort | |||||

| Trial treatment effective, same treatment and comparator given to “outsiders” | 7 | 6 626 | 2 293 | 19.0 | 0.04 (−0.04 to 0.13) | 37 |

| Trial treatment effective, treatment only given to “outsiders” | 3 | 1 391 | 5 072 | 9.4 | 0.51 (0.21 to 0.82) | 95 |

| Trial treatment effective, comparator only given to “outsiders” | 4 | 5 794 | 9 035 | 11.8 | 0.16 (0.07 to 0.25) | 74 |

| Trial treatment effective, neither treatment nor comparator given to “outsiders” | 9 | 649 | 188 | 11.3 | −0.36 (−0.61 to −0.12) | 43 |

| Trial treatment ineffective | 23 | 5 940 | 11 927 | 45.4 | −0.03 (−0.10 to 0.04) | 29 |

| Trial effect or treatment given unknown | 2 | 137 | 69 | 3.1 | 0.35 (0.02 to 0.68) | 0 |

| Overall | 48 | 20 537 | 28 584 | 100.0 | 0.04 (−0.04 to 0.12) | 88 |

Note: CI = confidence interval, RCT = randomized controlled trial.

There were 7 studies in which the randomized experimental intervention given to “insiders” (n = 6626) was effective, and “outsiders” (n = 2293) received that same intervention or the comparator. The heterogeneity was low to moderate (p = 0.2, I 2 = 37%), and the pooled result indicated neither significant harm nor significant benefit attributable to being an “insider” or an “outsider” (standardized mean difference 0.04, 95% confidence interval [CI] −0.04 to 0.13).

There were 3 studies in which the randomized experimental intervention (given to 1391 “insiders”) was effective, and the 5072 “outsiders” received only that same effective intervention. In this subgroup, there was a high degree of heterogeneity (p < 0.001, I2 = 95%).

There were 4 studies in which the randomized experimental intervention was effective, and “outsiders” received only the less effective comparator. In these studies, the 5794 “insiders” (those assigned to receive the active intervention or comparator) experienced a positive effect of the intervention, but the 9035 “outsiders” were offered only the ineffective comparator. In this subgroup, there was also a high degree of heterogeneity (p = 0.01, I2 = 74%).

There were 9 studies in which the randomized experimental intervention had a positive effect inside the RCT, but “outsiders” received a completely different intervention or comparator. For these studies, results could be pooled for the 649 “insiders” and 188 “outsiders” (standardized mean difference −0.36, 95% CI −0.61 to −0.12, p = 0.08, I 2 = 43%). In this subgroup, “insiders” fared statistically significantly better than “outsiders.”

The largest subgroup consisted of 23 studies in which the randomized experimental and comparator interventions generated equivalent outcomes. In this subgroup, the 5 940 “insiders” and 11 927 “outsiders” were given both treatments, only the control or only the experimental treatment, or completely different interventions. Heterogeneity among these studies was low to moderate (p = 0.10, I 2 = 29%). The pooled result revealed neither net harm nor net benefit for “insiders” compared with “outsiders” (standardized mean difference −0.03, 95% CI −0.1 to 0.04).

For the final subgroup of 2 studies, it was unclear whether there was a treatment effect or which interventions the “outsiders” received. We requested additional information from the study authors, but as of the date of publication, were still awaiting this clarification.

Outcomes for studies with participants randomized as “insiders” or “outsiders”

In 5 studies, potential participants were randomly assigned to become “insiders” or “outsiders.” One of these studies used a continuous outcome, with no reported difference between the 180 “insiders” and 97 “outsiders” (95% CI −0.22 to 0.27). The remaining 4 studies reported dichotomous nonmortality outcomes, with a moderate degree of heterogeneity (p = 0.06, I 2 = 60%). Their overall pooled effect indicated neither harm nor benefit when patients were treated inside or outside a trial (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.57).

Additional analyses

Our investigation into publication bias showed a lack of smaller studies (both positive and negative) in our study. Because the included studies were symmetric around the pooled estimate, we are confident that our estimates are valid.

Our sensitivity analysis confirmed the robust nature of our imputations. Removing the studies with imputed outcomes had no significant effect on our results. Similarly, the results were not affected by clinical specialty.

Interpretation

Our study has confirmed the earlier findings of Vist and colleagues4 and Gross and associates,157 who reported that when trial participants (“insiders”) and nonparticipants (“outsiders”) receive the same treatments, they experience similar outcomes. As such, there is neither a “trial advantage” nor a “guinea pig disadvantage” of participating in an RCT. Furthermore, we have shown that even when “insiders” and “outsiders” are offered different interventions, there is no disadvantage to trial participation.

Our findings do not support the theory of “inclusion benefits,” “protocol effects” or “care effects” proposed by other authors.3,158 We found no differences in outcomes that could be attributed to health care workers providing additional care to “insiders,” the setting in which “insiders” were treated or the closer follow-up and attention that “insiders” receive. Had there been better care because physicians were following strict study protocol, a difference would have been detected between the groups for whom treatments were identical and would have been amplified within the subgroup of studies in which detection bias and expertise bias were most probable.

As expected, our subanalysis of “insiders” and “outsiders” who received the same treatments confirmed the results of the Vist and Gross reviews.4,157 However, we suggest that their insistence on identical interventions for patients inside and outside of an RCT answered only a narrow, explanatory question. For our review, we posed a more pragmatic question: Will patients fare better being treated within a trial (as “insiders”) or in routine clinical care outside it (as “outsiders”), regardless of the treatment received? In other words, will they be “sacrificial guinea pigs,” or, conversely, will they enjoy an “inclusion benefit”? Or will they fare the same inside the RCT or outside it? Our pragmatic study supports the last of these options, that patients will, in general, fare just as well regardless of whether they are “insiders” or “outsiders.”

Stiller159 reported a beneficial effect on mortality for “insiders.” However, that conclusion was based on simply counting the number of studies in which “insiders” had lower mortality than “outsiders,” ignoring the size of each study. As such, smaller studies (which are more prone to type II error) were weighted the same as much larger studies. Our random-effects meta-analysis took into account the size and weight of each study, and we found no such benefit from trial participation.

Limitations

Although 68% of the studies included here employed identical follow-up protocols for both “insiders” and “outsiders,” some studies did not explicitly state whether “outsiders” included all eligible patients or only those for whom data could be obtained. If “outsiders” are more likely to become lost to follow-up, in part because they have died or suffered other adverse events, true trial advantages might be missed.

Conclusion

We found no evidence to support either clinically important harm or clinically important benefit when patients’ illnesses were managed inside or outside an RCT. These results can inform discussions between clinicians and the patients to whom they are offering entry into peer-reviewed, ethically conducted RCTs. These results are also relevant to the policies, procedures and actions of institutions, ethics committees and granting agencies that permit and support the execution of RCTs.

Our findings and conclusions are only as good as the publication base of relevant RCTs, and we look forward to the day when the proposals of Vickers160 and Altman and Cates161 are fully realized, with all trials registered and reported and with raw trial data made readily available. When that day arrives, our study should be repeated to determine the validity of the conclusions reached here.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. David Sackett for initiating this project. His insight and guidance throughout development of the manuscript were invaluable resources.

Footnotes

Competing interests: John Riva has received an NCMIC Foundation grant for work unrelated to the study reported here. He is also a board member of the Ontario Chiropractic Association. Lyndsay Somerville receives salary support (through her institution) from Smith & Nephew Canada. No other competing interests declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Neera Bhatnagar designed and carried out the search. Natasha Fernandes, Dianne Bryant, Mohamed El-Rabbany, Nisha Fernandes, Crystal Kean, Jacquelyn Marsh, Siddhi Mathur, Rebecca Moyer, Clare Reade, John Riva and Lyndsay Somerville chose the included studies and extracted data. Natasha Fernandes analyzed the data with supervision from Lauren Griffith. Natasha Fernandes wrote the primary draft of the protocol and manuscript, and all other authors edited and further developed these components. All authors approved the final version. Dianne Bryant supervised this project. All authors agree to act as guarantors of this paper.

Funding: This study was supported by an internal grant from the University of Western Ontario to Dianne Bryant; no external funding was received. Natasha Fernandes was supported by McMaster University, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canadian Graduate Scholarship and an Ontario Graduate Scholarship.

Data sharing: The dataset is available from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Schwartz D, Lellouch J. Explanatory and pragmatic attitudes in therapeutic trials. J Chronic Dis 1967;20:637–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sackett DL, Gent M. Controversy in counting and attributing events in clinical trials. N Engl J Med 1979;301:1410–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lantos JD. The “inclusion benefit” in clinical trials. J Pediatr 1999; 134:130–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vist GE, Bryant D, Somerville L, et al. Outcomes of patients who participate in randomized controlled trials compared to similar patients receiving similar interventions who do not participate. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(3):MR000009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiCenso A. Systematic overviews of the prevention and predictors of adolescent pregnancy [dissertation]. Waterloo (ON): University of Waterloo; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.SPSS base 10.0 for Windows user’s guide. Chicago: SPSS Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Review Manager for Microsoft Word. Version 5.2. Copenhagen: Cochrane Collaboration, Nordic Cochrane Centre; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. Oxford (UK): The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [updated March 2011]. Available: www.cochrane-handbook.org (accessed 2012 Aug. 21). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akaza H, Hinotsu S, Aso Y, et al. Bacillus Calmette–Guerin treatment of existing papillary bladder cancer and carcinoma in situ of the bladder. Four-year results. The Bladder Cancer BCG Study Group. Cancer 1995;75:552–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amar D, Roistacher N, Burt ME, et al. Effects of diltiazem versus digoxin on dysrhythmias and cardiac function after pneumonectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 1997;63:1374–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersson G, Lundstrom P, Strom L. Internet-based treatment of headache: Does telephone contact add anything? Headache 2003; 43:353–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antman K, Amato D, Wood W, et al. Selection bias in clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 1985;3:1142–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashok PW, Kidd A, Flett GM, et al. A randomised comparison of medical abortion and surgical vacuum aspiration at 10–13 weeks gestation. Hum Reprod 2002;17:92–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bain C, Cooper KG, Parkin DE. A partially randomised patient preference trial of microwave endometrial ablation using local anaesthesia and intravenous sedation or general anaesthesia: a pilot study. Gynaecol Endosc 2001;10:223–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bakker A, Spinhoven P, van Balkom AJ, et al. Cognitive therapy by allocation versus cognitive therapy by preference in the treatment of panic disorder. Psychother Psychosom 2000;69:240–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balmukhanov SB, Beisebaev AA, Aitkoolova ZI, et al. Intratumoral and parametrial infusion of metronidazole in the radiotherapy of uterine cervix cancer: preliminary report. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1989;16:1061–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bannister CF, Brosius KK, Sigl JC, et al. The effect of bispectral index monitoring on anesthetic use and recovery in children anesthetized with sevoflurane in nitrous oxide. Anesth Analg 2001;92:877–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bedi N, Chilvers C, Churchill R, et al. Assessing effectiveness of treatment of depression in primary care: partially randomised preference trial. Br J Psychiatry 2000;177:312–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bell R, Palma S. Antenatal exercise and birthweight. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2000;40:70–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhattacharya S, Cameron IM, Mollison J, et al. Admission–discharge policies for hysteroscopic surgery: a randomised comparison of day case with in-patient admission. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1998;76:81–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biasoli I, Franchi-Rezgui P, Sibon D, et al. Analysis of factors influencing inclusion of 102 patients with stage III/IV Hodgkin’s lymphoma in a randomised trial for first-line chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 2008;19:1915–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biederman J, Herzog DB, Rivinus TM, et al. Amitriptyline in the treatment of anorexia nervosa: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1985;5:10–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bijker N, Peterse JL, Fentiman IS, et al. Effects of patient selection on the applicability of results from a randomized clinical trial (EORTC 10853) investigating breast-conserving therapy for DCIS. Br J Cancer 2002;87:615–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blichert-Toft M, Brincker H, Andersen JA, et al. A Danish randomised trial comparing breast-preserving therapy with mastectomy in mammary carcinoma. Preliminary results. Acta Oncol 1988;27:671–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blumenthal JA, Jiang W, Babyak MA, et al. Stress management and exercise training in cardiac patients with myocardial ischemia. Effects on prognosis and evaluation of mechanisms. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:2213–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boesen EH, Boesen SH, Frederiksen K, et al. Survival after a psychoeducational intervention for patients with cutaneous malignant melanoma: a replication study. J Clin Oncol 2007;25: 5698–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boezaart AP, Berry RA, Laubscher JJ, et al. Evaluation of anxiolysis and pain associated with combined peri- and retrobulbar eye block for cataract surgery. J Clin Anesth 1998;10:204–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brinkhaus B, Witt CM, Jena S, et al. Acupuncture in patients with allergic rhinitis: a pragmatic randomised trial. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008;101:535–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caplan DB, Buchanan CN. Treatment of lower respiratory tract infections due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients with cystic fibrosis. Rev Infect Dis 1984;6(Suppl 3):S705–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coronary artery surgery study (CASS) (1984): a randomised trial of coronary artery bypass surgery. Comparability of entry characteristics and survival in randomised patients and nonrandomised patients meeting randomization criteria. J Am Coll Cardiol 1984;3:114–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chauhan SP, Rutherford SE, Hess LW, et al. Prophylactic intrapartum amnioinfusion for patients with oligohydramnios. A prospective randomised study. J Reprod Med 1992;37:817–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chesebro JH, Fuster V, Elveback LR, et al. Trial of combined warfarin plus dipyridamole or aspirin therapy in prosthetic heart valve replacement: danger of aspirin compared with dipyridamole. Am J Cardiol 1983;51:1537–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chilvers C, Dewey M, Fielding K, et al. Antidepressant drugs and generic counselling for treatment of major depression in primary care: randomized trial with patient preference arms. BMJ 2001;322:772–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clagett GP, Youkey JR, Brigham RA, et al. Asymptomatic cervical bruit and abnormal ocular pneumoplethysmography: a prospective study comparing two approaches to management. Surgery 1984;96:823–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clapp DW, Kliegman RM, Baley JE, et al. Use of intravenously administered immune globulin to prevent nosocomial sepsis in low birth weight infants: report of a pilot study. J Pediatr 1989;115:973–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clemens JD, van Loon FF, Rao M, et al. Nonparticipation as a determinant of adverse health outcomes in a field trial of oral cholera vaccines. Am J Epidemiol 1992;135:865–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooper KG, Grant AM, Garratt AM. The impact of using a partially randomised patient preference design when evaluating alternative managements for heavy menstrual bleeding. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997;104:1367–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cowchock FS, Reece EA, Balaban D, et al. Repeated fetal losses associated with antiphospholipid antibodies: a collaborative randomised trial comparing prednisone with low-dose heparin treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992;166:1318–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Creutzig U, Ritter J, Zimmermann M, et al. Does cranial irradiation reduce the risk for bone marrow relapse in acute myelogenous leukemia? Unexpected results of the childhood acute myelogenous leukemia study BFM-87. J Clin Oncol 1993;11: 279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dahan R, Caulin C, Figea L, et al. Does informed consent influence therapeutic outcome? A clinical trial of the hypnotic activity of placebo in patients admitted to hospital. BMJ Clin Res Ed 1986;293:363–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dalal HM, Evans PH, Campbell JL, et al. Home-based versus hospital-based rehabilitation after myocardial infarction: a randomised trial with preference arms — Cornwall Heart Attack Rehabilitation Management Study (CHARMS). Int J Cardiol 2007;119:202–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Decensi A, Robertson C, Viale G, et al. A randomised trial of low-dose tamoxifen on breast cancer proliferation and blood estrogenic biomarkers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003;95:779–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Detre KM, Guo P, Holubkov R, et al. Coronary revascularization in diabetic patients: a comparison of the randomised and observational components of the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation (BARI). Circulation 1999;99:633–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loeffler M, Diehl V, Pfreundschuh M, et al. Dose–response relationship of complementary radiotherapy following four cycles of combination chemotherapy in intermediate-stage Hodgkin’s disease. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:2275–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eberhardt K, Rydgren L, Fex E, et al. d-Penicillamine in early rheumatoid arthritis: experience from a 2-year double blind placebo controlled study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1996;14:625–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edsmyr F, Esposti PL, Johansson B, et al. Clinical experimental randomised study of 2,6-cis-diphenylhexamethylcyclotetrasiloxane and estramustine-17-phosphate in the treatment of prostatic carcinoma. J Urol 1978;120:705–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ekstein S, Elami A, Merin G, et al. Balloon angioplasty versus bypass grafting in the era of coronary stenting. Isr Med Assoc J 2002;4:583–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Emery M, Beran MD, Darwiche J, et al. Results from a prospective, randomised, controlled study evaluating the acceptability and effects of routine pre-IVF counselling. Hum Reprod 2003;18:2647–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Euler AR, Mitchell DK, Kline R, et al. Prebiotic effect of fructo-oligosaccharide supplemented term infant formula at two concentrations compared with unsupplemented formula and human milk. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2005;40:157–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feit F, Brooks MM, Sopko G, et al. Long-term clinical outcome in the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation Registry: comparison with the randomised trial. BARI Investigators. Circulation 2000;101:2795–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Forbes GM, Collins BJ. Nitrous oxide for colonoscopy: a randomised controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc 2000;51:271–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Franz MJ, Monk A, Barry B, et al. Effectiveness of medical nutrition therapy provided by dietitians in the management of non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: a randomised, controlled clinical trial. J Am Diet Assoc 1995;95:1009–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gall CA, Weller D, Esterman A, et al. Patient satisfaction and health-related quality of life after treatment for colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2007;50:801–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Girón M, Fernandez-Yanez A, Mana-Alvarenga S, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of individual family intervention on social and clinical functioning and family burden in severe schizophrenia: a 2-year randomised controlled study. Psychol Med 2010;40:73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goodkin DE, Plencner S, Palmer-Saxerud J, et al. Cyclophosphamide in chronic progressive multiple sclerosis. Maintenance vs nonmaintenance therapy. Arch Neurol 1987;44:823–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gossop M, Johns A, Green L. Opiate withdrawal: inpatient versus outpatient programmes and preferred versus random assignment to treatment. BMJ 1986;293:103–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grant AM, Wileman SM, Ramsay CR, et al. Minimal access surgery compared with medical management for chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: UK collaborative randomised trial. BMJ 2008;337:a2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gunn TR, Thompson JM, Jackson H, et al. Does early hospital discharge with home support of families with preterm infants affect breastfeeding success? A randomised trial. Acta Paediatr 2000;89:1358–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Helsing M, Bergman B, Thaning L, et al. Quality of life and survival in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer receiving supportive care plus chemotherapy with carboplatin and etoposide or supportive care only. A multicentre randomised phase III trial. Eur J Cancer 1998;34:1036–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Henriksson P, Edhaq O. Orchidectomy versus oestrogen for prostatic cancer: cardiovascular effects. BMJ 1986;293:413–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Heuss LT, Drewe J, Schnieper P, et al. Patient-controlled versus nurse-administered sedation with propofol during colonoscopy. A prospective randomised trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2004; 99:511–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hoh R, Pelfini A, Neese RA, et al. De novo lipogenesis predicts short-term body-composition response by bioelectrical impedance analysis to oral nutritional supplements in HIV-associated wasting. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;68:154–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Howard LM, Flach C, Leese M, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of admissions to women’s crisis houses compared with traditional psychiatric wards: pilot patient-preference randomised controlled trial. J Nerv Ment Dis 2009;197:722–7.19829199 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Howie FL, Henshaw RC, Naji SA, et al. Medical abortion or vacuum aspiration? Two year follow up of a patient preference trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997;104:829–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jena S, Witt CM, Brinkhaus B, et al. Acupuncture in patients with headache. Cephalalgia 2008;28:969–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jensen LB, Vestergaard P, Hermann AP, et al. Hormone replacement therapy dissociates fat mass and bone mass, and tends to reduce weight gain in early postmenopausal women: a randomised controlled 5-year clinical trial of the Danish Osteoporosis Prevention Study. J Bone Miner Res 2003;18:333–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kane WJ. Direct current electrical bone growth stimulation for spinal fusion. Spine 1988;13:363–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Karande VC, Korn A, Morris R, et al. Prospective randomised trial comparing the outcome and cost of in vitro fertilization with that of a traditional treatment algorithm as first-line therapy for couples with infertility. Fertil Steril 1999;71:468–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kayser B, Hulsebosch R, Bosch F. Low-dose acetylsalicylic acid analog and acetazolamide for prevention of acute mountain sickness. High Alt Med Biol 2008;9:15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kendrick D, Fielding K, Bentley E, et al. The role of radiography in primary care patients with low back pain of at least 6 weeks duration: a randomised (unblinded) controlled trial. Health Technol Assess 2001;5:1–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kieler H, Hellberg D, Nilsson S, et al. Pregnancy outcome among non-participants in a trial on ultrasound screening. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1998;11:104–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.King M, Sibbald B, Ward E, et al. Randomised controlled trial of non-directive counselling, cognitive-behaviour therapy and usual general practitioner care in the management of depression as well as mixed anxiety and depression in primary care. Health Technol Assess 2000;4:1–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kirke PN, Daly LE, Elwood JH. A randomised trial of low dose folic acid to prevent neural tube defects. The Irish Vitamin Study Group. Arch Dis Child 1992;67:1442–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Koch-Henriksen N, Sorensen PS, Christensen T, et al. A randomised study of two interferon-beta treatments in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2006;66:1056–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lansky D, Vance MA. School-based intervention for adolescent obesity: analysis of treatment, randomly selected control, and self-selected control subjects. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983;51:147–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lichtenberg P, Levinson D, Sharshevsky Y, et al. Clinical case management of revolving door patients — a semi-randomised study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2008;117:449–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lidbrink E, Frisell J, Brandberg Y, et al. Nonattendance in the Stockholm mammography screening trial: relative mortality and reasons for nonattendance. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1995;35: 267–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Link MP, Goorin AM, Horowitz M, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy of high-grade osteosarcoma of the extremity. Updated results of the Multi-Institutional Osteosarcoma Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1991;35:8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu PL, Shen WZ, Jing T, et al. Effects of compound Red-rooted Salvia and aspirin on platelet aggregation and PKB activity in the elderly patients with ACS. Chinese J New Drug 2009;18:900–2. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lock C, Wilson J, Steen N, et al. North of England and Scotland Study of Tonsillectomy and Adeno-tonsillectomy in Children (NESSTAC): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial with a parallel non-randomised preference study. Health Technol Assess 2010;14:1–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Luby S, Agboatwalla M, Schnell BM, et al. The effect of antibacterial soap on impetigo incidence, Karachi, Pakistan. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2002;67:430–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Macdonald JH, Marcora SM, Jibani MM, et al. Nandrolone decanoate as anabolic therapy in chronic kidney disease: a randomised phase II dose-finding study. Nephron Clin Pract 2007; 106:c125–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.MacLennan AH, Kerin JF, Kirby C, et al. The effect of porcine relaxin vaginally applied at human embryo transfer in an in vitro fertilization programme. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1985;25: 68–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.MacMillan JF, Crow TJ, Johnson AL, et al. Short-term outcome in trial entrants and trial eligible patients. Br J Psychiatry 1986;148:128–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mahon J, Laupacis A, Donner A, et al. Randomised study of n of 1 trials versus standard practice. BMJ 1996;312:1069–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mahon JL, Laupacis A, Hodder RV, et al. Theophylline for irreversible chronic airflow limitation: a randomised study comparing n of 1 trials to standard practice. Chest 1999;115:38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Marcinczyk MJ, Nicholas GG, Reed JF, et al. Asymptomatic carotid endarterectomy: patient and surgeon selection. Stroke 1997;28:291–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Martin LF. Stress ulcers are common after aortic surgery. Endoscopic evaluation of prophylactic therapy. Am Surg 1994;60: 169–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Martínez-Amenos A, Fernandez Ferre ML, Mota Vidal C, et al. Evaluation of two educative models in a primary care hypertension programme. J Hum Hypertens 1990;4:362–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Masood J, Shah N, Lane T, et al. Nitrous oxide (Entonox) inhalation and tolerance of transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy: a double-blind randomised controlled study. J Urol 2002;168:116–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mattila PS, Joki-Erkkila VP, Kilpi T, et al. Prevention of otitis media by adenoidectomy in children younger than 2 years. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003;129:163–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mayo Asymptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Study Group. Results of a randomised controlled trial of carotid endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Mayo Clin Proc 1992;67:513–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McCaughey ES, Mulligan J, Voss LD, et al. Randomised trial of growth hormone in short normal girls. Lancet 1998;351: 940–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.McKay JR, Alterman AI, McLellan AT, et al. Random versus nonrandom assignment in the evaluation of treatment for cocaine abusers. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998;66:697–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.McKay JR, Alterman AI, McLellan AT, et al. Effect of random versus nonrandom assignment in a comparison of inpatient and day hospital rehabilitation for male alcoholics. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995;63:70–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Melchart D, Steger HG, Linde K, et al. Integrating patient preferences in clinical trials: a pilot study of acupuncture versus midazolam for gastroscopy. J Altern Complement Med 2002;8: 265–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Moertel CG, Childs DS, O’Fallon JR, et al. Combined 5-fluorouracil and radiation therapy as a surgical adjuvant for poor prognosis gastric carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 1984;2:1249–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mori A, Nobutoshi F, Asano T, et al. Cardiovascular tolerance in unsedated upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: prospective randomised comparison between transnasal and conventional oral procedures. Dig Endosc 2006;18:282–7. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Morrison DA, Sethi G, Sacks J, et al. VA AWESOME (Angina With Extremely Serious Operative Mortality Evaluation) Multicenter Registry. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary bypass graft surgery for patients with medically refractory myocardial ischemia and risk factors for adverse outcomes with bypass: the VA AWESOME multi-center registry: comparison with the randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:266–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nagel HT, Vandenbussche FP, Keirse MJ, et al. Amniocentesis before 14 completed weeks as an alternative to transabdominal chorionic villus sampling: a controlled trial with infant follow-up. Prenat Diagn 1998;18:465–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Neldam S, Osler M, Hansen PK, et al. Intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring in a combined low- and high-risk population: a controlled clinical trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1986; 23:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nicolaides K, Brizot ML, Patel F, et al. Comparison of chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis for fetal karyotyping at 10–13 weeks’ gestation. Lancet 1994;344:435–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ogden JA, Alvarez RG, Levitt RL, et al. Electrohydraulic high-energy shock-wave treatment for chronic plantar fasciitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86A:2216–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Palmon SC, Liu M, Moore LE, et al. Capnography facilitates tight control of ventilation during transport. Crit Care Med 1996; 24:608–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Panagopoulou E, Montgomery A, Tarlatzis B. Experimental emotional disclosure in women undergoing infertility treatment: Are drop outs better off? Soc Sci Med 2009;69:678–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Paradise JL, Bluestone CD, Bachman RZ, et al. Efficacy of tonsillectomy for recurrent throat infection in severely affected children. Results of parallel randomised and nonrandomised clinical trials. N Engl J Med 1984;310:674–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Petersen MK, Andersen KV, Andersen NT, et al. To whom do the results of this trial apply? External validity of a randomised controlled trial involving 130 patients scheduled for primary total hip replacement. Acta Orthop 2007;78:12–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Raistrick D, West D, Finnegan O, et al. A comparison of buprenorphine and lofexidine for community opiate detoxification: results from a randomised controlled trial. Addiction 2005;100:1860–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Reddihough DS, King J, Coleman G, et al. Efficacy of programmes based on conducive education for young children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 1998;40:763–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rigg JR, Jamrozik K, Myles PS. Design of the multicenter Australian study of epidural anesthesia and analgesia in major surgery: the MASTER trial. Control Clin Trials 2000;21:244–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rørbye C, Nørgaard M, Nilas L. Medical versus surgical abortion: comparing satisfaction and potential confounders in a partly randomised study. Hum Reprod 2005;20:834–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rosen MA, Roizen MF, Eger EI, et al. The effect of nitrous oxide on in vitro fertilization success rate. Anesthesiology 1987;67:42–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Salisbury C, Francis C, Rogers C, et al. A randomised controlled trial of clinics in secondary schools for adolescents with asthma. British J Gen Pract 2002;52:988–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sesso HD, Gaziano JM, VanDenburgh M, et al. Comparison of baseline characteristics and mortality experience of participants and nonparticipants in a randomised clinical trial: the Physicians’ Health Study. Control Clin Trials 2002;23:686–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Shain RN, Ratsula K, Toivonen J, et al. Acceptability of an experimental intracervical device: results of a study controlling for selection bias. Contraception 1989;39:73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Smith P, Arnesen H. Mortality in non-consenters in a post-myocardial infarction trial. J Intern Med 1990;228:253–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Smuts CM, Borod E, Peeples JM, et al. High-DHA eggs: feasibility as a means to enhance circulating DHA in mother and infant. Lipids 2003;38:407–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Stecksén-Blicks C, Holgerson PL, Twetman S. Effect of xylitol and xylitol-fluoride lozenges on approximal caries development in high-caries-risk children. Int J Paediatr Dent 2008;18:170–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Stern C, Chamley L, Norris H, et al. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of heparin and aspirin for women with in vitro fertilization implantation failure and antiphospholipid or antinuclear antibodies. Fertil Steril 2003;80:376–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Stith SM, Rosen KH, McCollum EE, et al. Treating intimate partner violence within intact couple relationships: outcomes of multi-couple versus individual couple therapy. J Marital Fam Ther 2004;30:305–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Stockton KA, Mengersen KA. Effect of multiple physiotherapy sessions on functional outcomes in the initial postoperative period after primary total hip replacement: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009;90:1652–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Strandberg TE, Salomaa VV, Vanhanen HT, et al. Mortality in participants and non-participants of a multifactorial prevention study of cardiovascular diseases: a 28 year follow up of the Helsinki Businessmen Study. Br Heart J 1995;74:449–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Suherman SK, Affandi B, Korver T. The effects of Implanon on lipid metabolism in comparison with Norplant. Contraception 1999;60:281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sullivan MP, Fuller LM, Chen T, et al. Intergroup Hodgkin’s disease in children study of stages I and II: a preliminary report. Cancer Treat Rep 1982;66:937–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Sundar S, Rai M, Chakravarty J, et al. New treatment approach in Indian visceral leishmaniasis: single-dose liposomal amphotericin B followed by short-course oral miltefosine. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:1000–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Taddio A, Lee C, Yip A, et al. Intravenous morphine and topical tetracaine for treatment of pain in neonates undergoing central line placement. JAMA 2006;295:793–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Tanai C, Nokihara H, Yamamoto S, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer who declined to participate in randomised clinical chemotherapy trials. Br J Cancer 2009;100:1037–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tanaka S, Tsuchida H, Namba H, et al. Clonidine and lidocaine inhibition of isoflurane-induced tachycardia in humans. Anesthesiology 1994;81:1341–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Taplin D, Meinking TL, Castillero PM, et al. Permethrin 1% creme rinse for the treatment of Pediculus humanus var capitis infestation. Pediatr Dermatol 1986;3:344–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Tenenbaum A, Motro M, Fisman EZ, et al. Does participation in a long-term clinical trial lead to survival gain for patients with coronary artery disease? Am J Med 2002;112:545–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Toprak A, Erenus M, Ilhan AH, et al. The effect of postmenopausal hormone therapy with or without folic acid supplementation on serum homocysteine level. Climacteric 2005;8:279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Underwood M, Ashby D, Carnes D, et al. Topical or oral ibuprofen for chronic knee pain in older people. The TOIB study. Health Technol Assess 2008;12: iii–iv, ix–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Urban P, Stauffer JC, Bleed D, et al. A randomised evaluation of early revascularization to treat shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. The (Swiss) Multicenter Trial of Angioplasty for Shock-(S)MASH. Eur Heart J 1999;20:1030–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.van Bergen PF, Jonker JJ, Molhoek GP, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of non-participants of a multi-centre trial of long-term anticoagulant treatment after myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 1995;49:135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Van HL, Dekker J, Koelen J, et al. Patient preference compared with random allocation in short-term psychodynamic supportive psychotherapy with indicated addition of pharmacotherapy for depression. Psychother Res 2009;19:205–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Verdonck LF, van Putten WL, Hagenbeek A, et al. Comparison of CHOP chemotherapy with autologous bone marrow transplantation for slowly responding patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med 1995;332:1045–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Vind AB, Andersen HE, Pedersen KD, et al. Baseline and follow-up characteristics of participants and nonparticipants in a randomised clinical trial of multifactorial fall prevention in Denmark. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1844–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Walker WS, Raychaudhury T, Faichney A, et al. Wound colonisation following cardiac surgery. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1986;27:662–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Wallage S, Cooper KG, Graham WJ, et al. A randomised trial comparing local versus general anaesthesia for microwave endometrial ablation. Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2003;110:799–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Watzke B, Ruddel H, Jurgensen R, et al. Effectiveness of systematic treatment selection for psychodynamic and cognitive–behavioural therapy: randomised controlled trial in routine mental healthcare. Br J Psychiatry 2010;197:96–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Welt SI, Dorminy JH, Jelovsek FR, et al. The effect of prophylactic management and therapeutics on hypertensive disease in pregnancy: preliminary studies. Obstet Gynecol 1981;57:557–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.West J, Wright J, Tuffnell D, et al. Do clinical trials improve quality of care? A comparison of clinical processes and outcomes in patients in a clinical trial and similar patients outside a trial where both groups are managed according to a strict protocol. Qual Saf Health Care 2005;14:175–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Wetzner SM, Vincent ME, Robbins AH. Ceruletide-assisted cholecystography: a clinical assessment. Radiology 1979;131:23–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.World Health Organization (WHO) Task Force on Oral Contraceptives. Effects of hormonal contraceptives on breast milk composition and infant growth. Stud Fam Plann 1988;19:361–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Wieringa-de Waard M, Vos J, Bensel GJ, et al. Management of miscarriage: a randomised controlled trial of expectant management versus surgical evacuation. Hum Reprod 2002;17:2445–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Williford WO, Krol WF, Buzby GP. Comparison of eligible randomised patients with two groups of ineligible patients: Can the results of the VA Total Parenteral Nutrition clinical trial be generalized? J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:1025–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Witt CM, Jena S, Brinkhaus B, et al. Acupuncture in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee or hip: a randomised, controlled trial with an additional nonrandomised arm. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:3485–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Witt CM, Jena S, Brinkhaus B, et al. Acupuncture for patients with chronic neck pain. Pain 2006;125:98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Witt CM, Jena S, Selim D, et al. Pragmatic randomised trial evaluating the clinical and economic effectiveness of acupuncture for chronic low back pain. Am J Epidemiol 2006;164:487–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Witt CM, Reinhold T, Brinkhaus B, et al. Acupuncture in patients with dysmenorrhea: a randomised study on clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness in usual care. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;198:166 e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Woodhouse SP, Cox S, Boyd P, et al. High dose and standard dose adrenaline do not alter survival, compared with placebo, in cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 1995;30:243–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Wyse DG, Hallstrom A, McBride R, et al. Events in the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST): mortality in patients surviving open label titration but not randomised to double-blind therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991;18:20–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Yamamoto H, Hughes RW, Schroeder KW, et al. Treatment of benign esophageal stricture by Eder-Puestow or balloon dilators: a comparison between randomised and prospective non-randomised trials. Mayo Clin Proc 1992;67:228–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Yamani MH, Avery R, Mawhorter SD, et al. The impact of CytoGam on cardiac transplant recipients with moderate hypogammaglobulinemia: a randomised single-center study. J Heart Lung Transplant 2005;24:1766–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Yersin B, Besson J, Duc-Mingot S, et al. Screening and referral of alcoholic patients in a general hospital. Eur Addict Res 1996; 2:94–101. [Google Scholar]

- 157.Gross CP, Krumholz HM, Van Wye G, et al. Does random treatment assignment cause harm to research participants? PLoS Med 2006;3:e188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Braunholtz DA, Edwards SJ, Lilford RJ, et al. Are randomized clinical trials good for us (in the short term)? Evidence for a “trial effect.” J Clin Epidemiol 2001;54:217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Stiller CA. Centralised treatment, entry to trials and survival. Br J Cancer 1994;70:352–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Vickers AJ. Whose data set is it anyway? Sharing raw data from randomised trials. Trials 2006;7:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Altman DG, Cates C. Authors should make their data available. BMJ 2001;323:1069–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.