1. The early days of mismatch repair

I first learned about the existence of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) in the early 1970’s as a graduate student from Robert “Bob” C. Warner, who was one of the few people in our department whose lab worked on DNA. Bob was interested in isolating and proving the existence of Holliday junction-containing DNA molecules, the homologous recombination (HR) intermediate Robin Holliday had postulated in 1964 to form mispaired bases that could then account for some aspects of gene conversion when they were acted on by MMR [1]. I only later became aware of parallel studies on the possibility that MMR functioned in mutagenesis and replication fidelity [2]; the roles of mismatch repair in suppressing HR between divergent DNA and in the DNA damage response were discovered many years later (Discussed below). My many stimulating discussions with Bob led me to purify the only restriction endonuclease known at the time, the Hind II+III mixture, for use by his lab in their studies of HR intermediates. This experience led me away from my graduate studies with Krishna Tewari with whom I had worked performing quite challenging studies on the molecular characterization of chloroplast DNA to doing postdoctoral work on the enzymology of DNA replication. While I really enjoyed my postdoctoral studies on bacteriophage T7 DNA replication proteins and felt I was learning about protein purification from a true master, Charles Richardson, I also felt this was not the area I wanted to establish my own laboratory in. This rekindled my interest in HR and MMR and Charles was extremely generous to let me spend part of my time using new methods of site-directed mutagenesis to make mutations that altered restriction endonuclease cleavage sites in plasmid DNAs for use in making DNA substrates that I planned to use to study the genetics and biochemistry of HR and MMR. I cannot emphasize enough that I had three great mentors and how they each helped to educate me and aided in the advancement of my career. In this vein, I am also pleased that so many of my own trainees have gone on to establish their own successful labs.

When I moved to the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in 1978 to start my own lab, I began studying plasmid recombination and, to a lesser extent, MMR in Escherichia coli, areas that I really had never worked in before. Given this, it seems amazing that I was able to obtain an academic position and obtain funding for my lab; I think there is a lesson in my career experiences that I hope current day research institutions and funding agencies will reflect on leading them to adjust their ways to make it easier than presently seems possible for young scientists to go in new directions. During the 1960’s, 1970’s and early 1980’s the genetic basis for the model for E. coli methyl-directed MMR was worked out, to a great extent through the efforts of the Meselson, Marinus and Radman labs as well as others [3–8]. This system was thought to act on mispairs that were formed as a result of DNA replication errors as well as on mispairs that were formed in heteroduplex HR intermediates when mutant and wild-type single strands were paired with each other [9, 10]. The key MMR genes including mutS, mutL, mutH, uvrD and dam were identified through genetic studies [9, 10].

Transient under-methylation of the newly synthesized DNA strand was proposed to be the strand specificity mark during post-replication MMR and some studies suggested that MutS might be involved at the mispair recognition step and that MutL and MutH might be involved in strand discrimination [9–12]. These studies as well as the availability of the replication proteins and exonucleases set the stage for the subsequent reconstitution studies from the Modrich lab [13, 14] and mechanistic studies of individual E. coli MMR proteins from the Modrich lab and many other labs (For representative reviews see [15, 16]). In retrospect, it is ironic that the studies of E. coli MMR have been so influential in the MMR field given that methyl-directed post-replication MMR only occurs in a small group of bacteria (see the minireview by Putnam in this issue). Below I provide a personal overview of eukaryotic MMR including my views of the history of MMR, what we know about MMR mechanisms, the role of MMR defects in cancer and questions that remain to be answered. However, I refer the reader to the work of the authors contributing articles to this volume as well as other papers for the details and the many aspects of MMR, including E. coli MMR, that I have not had space to cover in detail.

The nomenclature for MMR genes/proteins is confusing because the human homolog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae PMS1 was named PMS2 and the human homolog of S. cerevisiae MLH2 was named PMS1. In this article, I have generally used S. cerevisiae gene/protein names. However, in places where it was important to specifically refer to a human or mouse gene/protein, I have included the suffixes sc (S. cerevisiae), h (human) and mus (mouse) to help prevent confusion. A useful summary table of MMR genes, proteins and protein complexes has been published recently [17] (see the minireview by Putnam in this issue).

2. Identification of eukaryotic mismatch repair genes and proteins

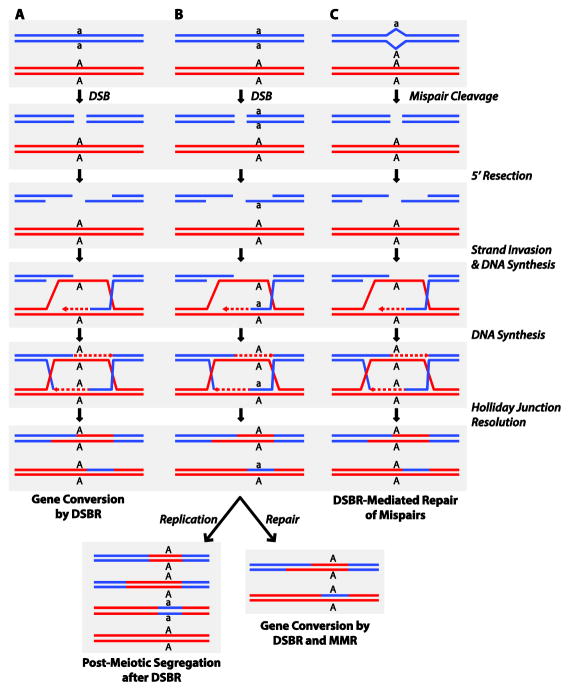

Having already developed studies of HR in the yeast S. cerevisiae, my lab initiated studies on S. cerevisiae MMR because of two observations suggesting that eukaryotic MMR might be quite different from E. coli MMR. First, S. cerevisiae was found to have no DNA methylation and therefore could not have methyl-directed MMR [18, 19]. Second, with the development of the double strand break repair (DSB/DSBR) model of HR [20], it was proposed that DSBR could account for the relationship between gene conversion and post-meiotic segregation of genetic markers without the need for classical MMR [20]. Thus, it was proposed that gene conversion would occur when a genetic marker was located in the region near the DSB that was degraded during DSBR to form a double strand gap eliminating the mutant or wild-type allele, and post-meiotic segregation would occur when the genetic marker was located in the region of heteroduplex DNA flanking the DSB during DSBR, thus resulting in a mispair that was then not acted on by MMR. Further, post-replication MMR could be explained if an endonuclease were to make a DSB at the site of a mispair followed by DSBR with the sister DNA serving as a donor during repair [21]; endonucleases that could cleave at mispairs had been discovered [22]. This model was in contrast to more classical models where heteroduplex HR intermediates containing mispaired bases were formed and were then either repaired by MMR resulting in gene conversion or escaped repair resulting in post-meiotic segregation of the genetic marker [20]. A model illustrating these views of HR is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Double strand break repair models illustrating potential roles of mismatch repair in recombination and potential roles of double strand break repair in mismatch repair.

A. DSBR model that explains how gene conversion can occur without the need to invoke MMR. One (the a allele) of the two alleles (a allele-containing chromosome in blue and A allele-containing chromosome in red) whose segregation during DSBR is illustrated is located on the recipient chromosome at the location where the DSB occurs and is then expanded into a gap with 3′ single strand overhangs thus eliminating the a allele. Strand invasion to form a D-loop followed by priming of repair synthesis (dashed lines) and strand displacement, capture of the other end of the DSB and additional repair DNA synthesis result in the formation of a double Holliday junction intermediate. Resolution of the two Holliday junctions in the non-crossover directions yields two A allele-containing chromosomes and hence a gene conversion event. Other resolution directions are possible, but these do not alter the illustrated gene conversion event. B. An alternative of the DSBR model illustrated in A where one (the a allele) of the two alleles whose segregation during DSBR is illustrated is located on the recipient chromosome in the region that is converted to a 3′ single strand overhang. This then results in the formation of a heteroduplex region containing an A:a mispair on one of product chromosomes whereas repair synthesis recreates the starting allele on both strands of the other produce chromosome. If DNA replication then occurs without MMR (Left) Post-Meiotic Segregation results whereas if MMR occurs prior to DNA replication as illustrated (Right), then gene conversion occurs. C. The DSBR model can account for post-replication repair of mispairs if a mispair (illustrated as a:A) generated as the result of a replication error is simply cleaved by a mismatch-specific endonuclease to generate a DSB. Then DSBR will result in copying the wild-type allele into the broken chromosome effectively producing the same outcome as classical excision repair mechanisms of MMR.

To investigate whether S. cerevisiae had classical MMR, we adapted our previously developed E. coli heteroduplex plasmid transformation system [11, 12] to the study of MMR in S. cerevisiae. On transformation of S. cerevisiae with heteroduplex plasmids, we recovered plasmid products that were consistent with MMR having acted on these plasmids [23, 24]. We also showed that cell-free extracts of S. cerevisiae were able to catalyze repair of mispair-containing M13 phage-based heteroduplex substrates [25]; other eukaryotic cell-free MMR systems were subsequently developed by others [26–28]. At this time we were aware of mutations identified in Seymour Fogel’s lab named pms mutations, for Post-Meiotic Segregation, which caused a decrease in gene conversion events and a concomitant increase in post-meiotic segregation events [29]. Interpreted in the context of classical MMR, these results were consistent with pms mutations causing a MMR defect. However, interpreted in the context of the DSBR model, these results were consistent with pms mutations causing a decrease in the size of the double strand gap and an increase in the length of the heteroduplex regions flanking the double strand gap increasing the chance that the position of the allele being followed would fall in the heteroduplex region flanking the DSB. We obtained pms1 mutations from the Fogel lab and used our heteroduplex plasmid transformation assays to show that pms1 mutations caused increased recovery of plasmid products that had escaped repair, thus establishing pms1 mutations as causing a MMR defect and defects in processing mispairs formed during meiotic recombination to gene conversion events resulting in increased post-meiotic segregation events [30]. Our subsequent studies of Seymour’s pms1 through pms6 mutations were of great value in helping to identify and study MMR genes. As a philosophical note, I have found trying to address this type of unanswered, possibly even somewhat controversial scientific question to be the most intellectually rewarding part of being a scientist.

Seymour’s lab went on to clone the PMS1 gene and discovered that it encoded a MutL homologue, a critical protein in E. coli MMR [31]. This was extremely surprising to me as we thought that eukaryotes did not have methyl-directed MMR. This motived my lab to use newly developed methods of degenerate PCR to search for S. cerevisiae genes encoding MutS homologues. We were able to initially identify two such MutS Homologue genes, MSH1 and MSH2 [32, 33]. Genetic studies suggested that MSH1 encoded a protein that functioned in the repair of mitochondrial DNA [33]; this was surprising because the prevailing view at the time, now no longer held, was that mitochondria lacked DNA repair systems. In contrast, genetic studies showed that msh2 defects caused increased nuclear mutation rates and increased post-meiotic segregation of genetic markers during meiosis establishing Msh2 as the first identified eukaryotic MutS related protein [33]; MSH2 was later found to be the gene mutated in Fogel’s pms5 mutant [34]. The Crouse laboratory identified MSH3, which was also known in humans and mouse, but msh3 defects were not initially found to cause phenotypes consistent with MMR defects [35]. We also identified MSH6 by analyzing the S. cerevisiae genome sequence and found that it was the gene mutated in Fogel’s pms3 and pms6 mutants, which had not yet been extensively studied [36, 37]. The MSH4 and MSH5 genes (see the minireview by Manhart and Alani in this issue), encoding proteins that function in meiotic recombination but not MMR, were described by others [38, 39] and will not be discussed in this article. A key clue to the Msh proteins came from studies of human cell-free extracts that catalyzed MMR performed in the Modrich and Jiricny labs, that identified the in vitro human msh2 MMR defect-complementing activity as a two subunit protein complex containing Msh2 and a fragment of GTBP (also called Msh6) [40, 41]. My lab performed two-hybrid interaction studies showing that Msh2 was the common subunit of the Msh2-Msh3 and Msh2-Msh6 complexes [36]. We further showed that these complexes were partially redundant with each other, consistent with the idea based on the function of bacterial MutS that these complexes were mispair recognition proteins with partially overlapping mispair-binding specificity [36]. Other genetic studies provided additional details about the predicted mispair recognition specificity of these two complexes [42]. Collaborative biochemical studies with the Fishel lab as well as biochemical studies by others quickly extended this model to the human MSH complexes [43, 44] and studies of mutant mice and mouse cell lines as well as human tumor cell lines provided supporting genetic evidence [45–49].

The discovery and characterization of the MutL Homologue or MLH complexes was similar to that of the MSH complexes. S. cerevisiae MLH1 was discovered by the Liskay lab using degenerate PCR similar to the discovery of MSH2 [50] and later found to be the gene mutated in Fogel’s pms2 and pms4 mutants [51]. Genetic studies showed that defects in MLH1 and PMS1 caused very similar mutator phenotypes [50] and, consistent with this early biochemical studies, established the existence of a Mlh1-Pms1 complex that could be recruited by Msh2 [52]. Protein fractionation studies identified the human in vitro mlh1 MMR defect-complementing activity as a two-subunit complex containing Mlh1 and Pms2 (Pms2 is the human homologue of S. cerevisiae Pms1) [53]. The other two S. cerevisiae MLH genes, MLH2 and MLH3 were identified through the analysis of the S. cerevisiae genome sequence as well as using two-hybrid screens [54–56]. Like Pms1, the Mlh3 protein forms a complex with Mlh1, and genetic studies have indicated that the Mlh1-Mlh3 complex plays a minor role in MMR by substituting for Mlh1-Pms1 in the repair of some types of mispairs [55, 56], as have biochemical studies of hMlh1-Mlh3 [57]. The Mlh1-Mlh3 complex also plays a role in meiotic recombination in conjunction with the Msh4-Msh5 complex [54, 58, 59]. The Mlh1-Mlh2 complex has remained enigmatic. Genetic studies in both S. cerevisiae and mouse as well as biochemical complementation studies utilizing human in vitro MMR reactions initially provided little evidence for a role in MMR [56, 60, 61] although some studies have suggested Mlh2 might play a minor role in meiotic recombination [54, 59]. However, recent studies have indicated that Mlh1-Mlh2 is more important for MMR when Mlh1-Pms1 levels are reduced suggestive of a different role in MMR than the other MutL homologue complexes [62].

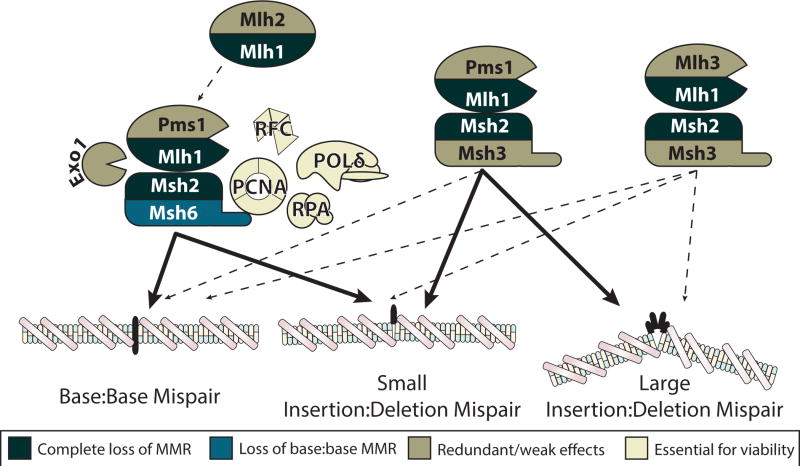

The other genes/proteins thought to be involved in MMR include Exonuclease 1 (Exo1), Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA), Replication Factor C (RFC), Replication Factor/Protein A (RPA) and DNA polymerase δ (DNA Pol δ). Exo1 was first described as a meiotic HR 5′ to 3′ exonuclease in S. pombe [63, 64]. A role for Exo1 in MMR in S. cerevisiae was discovered through the isolation of EXO1 as encoding an Msh2-interacting protein in a two-hybrid screen [65] and was subsequently found to also interact with Mlh1 [66, 67]. While Exo1 is thought to play a key role in the excision step of MMR, genetic studies have shown that Exo1 is not essential for MMR and that other excision mechanisms must exist [65, 68, 69]. PCNA was implicated in MMR through its role in the resynthesis step of MMR, through protein-protein interaction studies, and the identification of mutations in the S. cerevisiae POL30 gene encoding PCNA, which cause MMR defects and a mutator phenotype [70–73]. Subsequently, PCNA was shown to play a role in coupling MMR to DNA replication through interactions with PIP (PCNA-interacting peptide)-box motifs located in the N-termini of Msh3 and Msh6 [74–77]. PCNA also interacts with scMlh1-Pms1 and hMlh1-Pms2 [78, 79], and this interaction could play a role in activating the endonuclease activity of these 2 complexes [80, 81]. The PCNA loading factor RFC was implicated in MMR through the requirement for PCNA, and the identification of a MMR-defective mutation in one of the genes encoding RFC has provided genetic support for this requirement [82]. DNA Pol δ was implicated in MMR through in vitro reconstitution studies [83], but a possible role for other DNA polymerases has not been ruled out. Similarly, RPA was implicated in MMR through in vitro reconstitution studies [84–86]. Some studies have suggested that HMGB, PARP1, RFX and most recently the MCM8-MCM9 complex may play a role in MMR, but the evidence for these is in my view not yet well established [87–90]. A model summarizing the known MMR proteins is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Illustration summarizing the known eukaryotic proteins that function in mismatch repair.

An MMR pathway involving the Msh2-Msh6 mispair recognition complex, the Mlh1-Pms1 endonuclease, Exo1, PCNA, the RFC clamp loader, RPA and DNA Pol δ is illustrated on the left side of the figure. Interactions between Msh2 and Mlh1, between Exo1 and both Msh2 and Mlh1, and between PCNA and the N-terminus of Msh6 are indicated. The Mlh1-Mlh2 complex, which is not an endonuclease, is indicated because it appears to have a role in MMR when the level of Mlh1-Pms1 is experimentally reduced. Substitution of the Msh2-Msh3 mispair recognition complex for Msh2-Msh6 is illustrated in the center and on the right, and substitution of the Mlh1-Mlh3 complex for the Mlh1-Pms1 complex in MMR reactions involving Msh2-Msh3 is illustrated to the right (note that it has not been resolved whether Mlh1-Mlh3 can also function in conjunction with Msh2-Msh6). The thickness of the arrows connecting each pathway to the three classes of mispairs illustrated reflects the relative importance of each pathway in repair of the different classes of mispairs. The color-coding indicates whether the different genes are essential or are redundant/partially redundant with each other and hence whether loss-of-function mutations in the different genes result in complete or partial loss of MMR or inviability. All gene/protein names are S. cerevisiae gene/protein names.

3. Biochemical activities of MMR proteins

The presently known MMR proteins fall into two groups. One consists of proteins that function in many aspects of DNA metabolism including DNA replication and recombination, such as Exo1, RPA, PCNA, RFC and DNA Pol δ. These proteins have been extensively characterized in a variety of contexts and will not be generally commented on here. The second consists of proteins that are more specific to MMR, including the MutS-related heterodimers Msh2-Msh6 and Msh2-Msh3 and the MutL-related heterodimers Mlh1-Pms1 (Mlh1-Pms2 in human), Mlh1-Mlh3 and Mlh1-Mlh2 (Mlh1-Pms1 in human) (see the minireview by Putnam in this issue). Many of these proteins have been extensively characterized using a diversity of techniques beyond more standard biochemical studies including X-ray crystallography, small angle X-ray scattering, deuterium-exchange mass spectrometry, imaging proteins in vivo and single molecule biochemistry approaches, many of which have been coupled to different types of genetics studies [91, 92] (see the minireviews by Groothuizen and Sixma, by Friedhoff and Gotthardt and by Schmidt and Hombauer in this issue). The application of these approaches has been exciting to follow and has brought many new insights to the field.

The Msh2-Msh6 and Msh2-Msh3 mispair-recognition complexes have been shown to form a ring around DNA and under certain conditions form a sliding clamp structure, a conformation that the Fishel lab has extensively studied and incorporated into specific models for MMR mechanisms [93, 94] (see the minireview by Hingorani in this issue). In the absence of nucleotide or in the presence of ADP, these mispair recognition factors appear to form an unstable ring on base paired DNA and similarly form an unstable ring at the site of the mispair in mispaired DNA [95]. On addition of ATP, the proteins bound to base paired DNA dissociate whereas the mispair-bound proteins are converted to a stable clamp that then slides along the DNA and, on linear DNAs, dissociates from the ends of the DNA [93, 96–98]. The pioneering X-ray crystallography studies of the bacterial MutS proteins performed by Sixma [99] as well as Hsieh and Yang [100], followed later by structural studies of the eukaryotic Msh complexes [101, 102] as well as structure-function genetics studies have contributed enormously to the understanding of the mispair-bound forms of these proteins. The Msh2-Msh6 and Msh2-Msh3 complexes can also recruit Mlh1-Pms1 and Mlh1-Mlh2, and most likely Mlh1-Mlh3, in a mispair-dependent, ATP-dependent reaction corresponding to the conditions where sliding clamps form [62, 95, 97, 103–107]. However, while mutations that disrupt sliding clamp formation also disrupt MMR [37, 108, 109], it is not clear at which step of MMR sliding clamps are required because at least one sliding clamp-defective Msh2-Msh6 mutant is proficient for recruiting and activating the Mlh1-Pms1 endonuclease and promotes Mlh1-Pms1 endonuclease-dependent MMR reactions in vitro [110]. It is also possible that sliding clamps reflect an ATP-induced conformational change required for MMR with sliding clamps being predominantly seen in the absence of other MMR proteins. Many studies have suggested that a stable 1:1 complex of an Msh complex with an Mlh complex plays a role in MMR (for representative papers see [97, 103, 104, 106, 107]). In contrast, imaging of MMR proteins in living cells has suggested that Msh2-Msh6, and likely Msh2-Msh3, can act to catalytically load multiple molecules of Mlh1-Pms1 and Mlh1-Mlh2 (and possibly Mlh1-Mlh3) onto DNA in a mispair-dependent reaction [62, 77]. Determining if the Msh complexes can catalytically load Mlh complexes onto DNA in reconstituted biochemical reactions and then elucidating the biochemical activities of the Msh complex-free Mlh complexes will be critical to decipher the mechanism of the early steps in MMR.

The function of the eukaryotic MutL-related complexes, Mlh1-Pms1, Mlh1-Mlh3 and Mlh1-Mlh2 remained poorly understood for approximately twelve years after the first such complex, Mlh1-Pms1, was discovered. Then the Modrich lab demonstrated that both the human hMlh1-Pms2 complex and its S. cerevisiae homolog scMlh1-Pms1 have an endonuclease activity [70, 111] (see the minireview by Kadyrova and Kadyrov in this issue). The endonuclease active site has been extensively characterized by structure-function genetics and X-ray crystallography [110, 112, 113]. This endonuclease has very weak activity on its own but can be activated to nick supercoiled, base paired DNA by PCNA and RFC and can be more strikingly activated by Msh2-Msh6 (or Msh2-Msh3), PCNA and RFC to nick mispaired DNA containing a pre-existing nick. Remarkably, in this latter 4-protein nicking reaction, the Mlh1-Pms1 complex is highly specific for nicking the already nicked strand [70, 80, 110, 111]. Not only is the molecular mechanism for this strand-specific nicking unknown, a role for such a mechanism in MMR seems paradoxical given that pre-existing nicks are often present in newly replicated DNA, in particular during lagging strand replication and these can potentially serve as sites for the initiation of excision reactions. It is possible that such a mechanism simply increases the probability of nicks being present 5′ to mispairs to act as substrates for Exo1 or other excision processes, or it is possible that this mechanism reflects other excision mechanisms possibly mediated by high-density nicking at or near the mispair [81, 114]. Sequence homology relationships suggested that Mlh1-Mlh3 would have an endonuclease activity (see the minireview by Putnam in this issue) and this has been demonstrated, although the properties of the Mlh1-Mlh3 endonuclease thus far reported are strikingly different from those of the Mlh1-Pms1 endonuclease [115, 116]. The Mlh1-Mlh2 complex is not predicted to have an endonuclease activity (see the minireview by Putnam in this issue) and its possible role in MMR has remained unclear. Surprisingly, Mlh1-Mlh2 shares many properties with Mlh1-Pms1 including mispair-dependent recruitment by Msh2-Msh6 and Msh2-Msh3 and mispair- and Msh2-Msh6-dependent formation of foci in living cells, suggesting that Mlh1-Msh2 may play some type of accessory role in MMR [62]. Much remains to be learned about Mlh1-Mlh2 and Mlh1-Mlh3 in comparison to what we know about Mlh1-Pms1.

4. Reconstitution of MMR in vitro

The demonstration that extracts of S. cerevisiae, Xenopus, Drosophilia, human and mouse cells could catalyze repair of mispair-containing DNAs [25–28, 69] set the stage for biochemical fractionation and reconstitution studies demonstrating that eukaryotic MMR proteins can catalyze a nick-directed MMR reaction similar to the reaction catalyzed by E. coli MMR proteins. The most rapid progress was made in the human system, largely due to work performed in the Modrich and Li labs. However, I am pleased that my lab was ultimately able to reconstitute MMR reactions using purified S. cerevisiae MMR proteins, making it possible to apply the wealth of insights from genetics studies of MMR in S. cerevisiae to the biochemistry of reconstituted MMR reactions. To date, reconstitution studies have defined two types of mispair-directed excision/repair reactions. In one reaction, a combination of Msh2-Msh6 or Msh2-Msh3, Exo1, DNA Pol δ, the single-stranded DNA binding protein RPA, PCNA and RFC promotes the repair of a circular mispaired substrate containing a nick on the 5′ side of the mispair. In this reaction, the mispair recognition factors and other proteins promote excision by Exo1 past the mispair, followed by repair DNA synthesis to fill in the resulting gap repairing the initial mispair [85, 86, 117]. In a second reaction, a combination of Msh2-Msh6 or Msh2-Msh3, Mlh1-Pms1 (hMlh1-Pms2), Exo1, DNA Pol δ, RPA, PCNA and RFC promotes the repair of a circular mispaired substrate containing a nick on the 3′ side of the mispair. In this reaction, the Mlh1-Pms1 endonuclease is activated to generate nicks 5′ to the mispair, which then allows Exo1-dependent 5′ excision and subsequent gap filling to occur essentially as in the 5′-nick-directed in vitro MMR reactions [86, 110]. In both of these reactions, mispair recognition by Msh2-Msh6 and Msh2-Msh3 appears to stimulate excision by Exo1, in part by overcoming inhibition of Exo1 by RPA [118]. Whether the ability of Exo1 to interact with Msh2, and potentially with the Msh2-Msh6 and Msh2-Msh3 sliding clamps, plays a role in this stimulation of Exo1 is unclear. Mlh1-Pms1 does not stimulate excision in reconstituted 5′-nick-directed MMR reactions even though hMlh1-Pms2 appears to be required for maximal 5′-nick-directed excision in human extract-based MMR reactions under conditions where the hMlh1-Pms2 endonuclease should not be required [119].

A critical question about the reconstituted MMR reactions discussed above is how well they correspond to MMR in vivo. It seems likely that these reactions recapitulate nick-directed Exo1-mediated mispair excision and coupled gap-filling by DNA Pol δ that functions in MMR, particularly on the lagging strand, which is expected to have a high density of nicks due to discontinuous DNA synthesis. It is not clear whether other DNA polymerases besides DNA Pol δ can participate in the gap-filling reaction. In contrast, genetic studies in S. cerevisiae and mice have shown that Exo1 defects only cause small defects in MMR and that redundant excision mechanisms exist [65, 69, 120]. Strikingly, all known mutations that specifically inactivate Exo1-independent MMR but not Exo1-dependent MMR that have been characterized to date are highly but not completely defective for activation of the Mlh1-Pms1 endonuclease [68, 81, 110]. These mutations all cause defects in reconstituted Mlh1-Pms1-dependent MMR reactions suggesting that these reactions could represent coupling of the Exo1-independent MMR Mlh1-Pms1 activation pathway to an Exo1-dependent excision system [110]. These results also suggest that high levels of Mlh1-Pms1 endonuclease activation are required for Exo1-independent MMR, raising the possibility that high levels of Mlh1-Pms1 endonuclease activation could represent an endonuclease-promoted mispair excision pathway [81, 114]. Other possible Exo1-independent mispair excision mechanisms have also been proposed [120, 121]. Finally, MMR is coupled to DNA replication in vivo [77, 122], but little is known about how the MMR mechanisms defined in vitro are coupled to DNA replication.

5. Genetics of mammalian MMR defects

My initial interest in a possible relationship between MMR defects and human disease came from the similarity between the phenotypes caused by defects in S. cerevisiae MSH1 and some of the human mitochondrial myopathies; this idea did not prove to be relevant as mammals do not appear to contain a gene encoding an Msh1 protein. Regardless, I set out to try to clone human and mouse MSH2 in collaboration with Rick Fishel and later to clone human MLH1 and PMS1 (known in the literature as PMS2) by extending the collaboration to include Mike Liskay. I knew that defects in MMR genes caused microsatellite instability due to the published work on E. coli MMR and because I had given my msh2 mutations to Tom Petes for his studies on microsatellite instability in S. cerevisiae [123, 124]. We had already cloned the human MSH2 gene when reports appeared on microsatellite instability in human tumors and in tumors associated with Hereditary Non-polyposis Colorectal Cancer (HNPCC, now called Lynch Syndrome) [125, 126], causing considerable excitement. We rapidly mapped the MSH2 gene to the Chromosome 2 HNPCC locus, setting off our search for evidence that MSH2 was mutated in HNPCC [127, 128]. The chromosome 3 HNPCC locus was reported a few months later [129] leading to our subsequent studies demonstrating that MLH1 was the chromosome 3 HNPCC gene [130, 131]. We focused on these two genes because they were the only two genes that could be linked to HNPCC by mapping studies. Similar studies were performed de la Chapelle and Vogelstein [132, 133]. It was exciting for me to learn how to clone and determine the structure of mammalian genes and to set up molecular diagnostics assays. I was particularly grateful to my colleagues at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute who worked very hard to help identify collaborators who could provide samples from HNPCC families for analysis. I was also grateful to be able to work with these clinical collaborators, whose efforts were essential in ultimately showing that MSH2 and MLH1 were the major HNPCC genes and in bringing these genes into the area of molecular diagnostics of cancer predisposition. A particularly striking moment occurred when a mutation carrier identified in our initial studies who did not have cancer was reexamined by their physician and found to have a previously undetected cancer, thereby potentially saving her life; this impressed on me the true importance of finding ways to use basic science discoveries to impact human health.

Many laboratories rapidly started working on the relationship between MMR defects and cancer susceptibility, both through studies of human patients and the establishment of mouse models (see the minireviews by Heinen, by Begum and Martin, by Peña-Diaz and Rasmussen, by Sijmons and Hofstra and by Lee, Tosti and Edelmann in this issue). My lab focused on further developing the genetics and biochemistry of S. cerevisiae MMR, which has provided an excellent foundation for studies of the genetics of MMR in human and mouse, the development of molecular diagnostics for defects in MSH2 and MLH1 as these were clearly the major Lynch Syndrome genes (they were also the only cancers we had good access to), and providing the first evidence for silencing of MLH1 in sporadic MMR-defective cancers and for MLH1 epimutations [128, 131, 134, 135]. Studies from other labs established that hPMS2 and MSH6 were also defective in cancer, albeit in cancers/syndromes that seem somewhat different from classical Lynch syndrome, whereas defects in hPMS1 (scMLH2), MLH3 and EXO1 were not convincingly demonstrated or were very rare, consistent with the weak mutator phenotypes caused by defects in these genes in model organisms (For representative papers see [136–140]). Studies of human cancer cell lines containing MMR defects initially characterized in the Karran and Kunkel labs as well as by others also helped establish the nature of human MMR defects and the relationships between MMR and DNA damage responses [141–145]. The first mouse models of MMR defects were produced by the Liskay (mPMS2) and Mak (MSH2) labs and de Wind working with te Riele (MSH2); these were rapidly followed by studies of other mouse MMR genes by Edelmann and Kucherlapati (MLH1, MSH6, MSH3, EXO1), Liskay (MLH1), de Wind and te Riele (MSH6, MSH3) and Lipkin (MLH3) [45–47, 60, 69, 146–151] (see the minireview by Lee, Tosti and Edelmann in this issue). The extensive efforts in human and mouse genetics, most recently incorporating data generated by cancer genome sequencing projects such as The Cancer Genome Atlas Project have provided a broad picture of the contribution of human MMR defects to cancer susceptibility; it is gratifying to me that studies in S. cerevisiae have provided such an accurate road map for the study of the mammalian MMR genes attesting to the importance of studies in model organisms. In the long run, I hope that understanding MMR defects in cancer will lead to treatments for MMR-defective cancers and in this regard, recent reports that MMR defects may predict responses to immunotherapy are cause for optimism [152, 153].

6. Unanswered or incompletely answered big-picture questions about MMR mechanisms

While we have learned a great deal about eukaryotic MMR, there is still much that we do not know. The unanswered questions about MMR appear to fall in three general areas. First, what are the detailed reaction mechanisms of individual MMR proteins and key groups of MMR proteins that functionally interact? Second, how do we reconstitute complete MMR reactions that reflect coupling to DNA replication, processing of chromatin substrates and how are strand-discrimination signals produced and recognized? Third, how do MMR proteins function in other processes beyond post-replication MMR such as preventing recombination between divergent DNA sequences and the DNA damage response?

The MMR proteins are a fascinating group of proteins and individual activities have been linked to each protein and studied in almost all cases. A striking property of virtually all known MMR proteins is that their function in MMR is driven by different conformational changes and different protein-protein interactions. Yet how these interactions then modulate the activities of each MMR protein seems less clear. Some examples include: 1) do interactions of Exo1 with Msh2-Msh6 (or Msh2-Msh3) and/or Mlh1-Pms1 play a role in recruiting and activating Exo1; 2) how does Mlh1-Pms1 interact with its activating proteins so that its nicking activity is directed to the already nicked strand; 3) does Mlh1-Pms1 function as a stable complex with Msh2-6 (or Msh2-Msh3) or is it loaded onto the DNA and then acts independently of the mispair recognition proteins; 4) does Mlh1-Mlh2 stimulate the activity of Mlh1-Pms1 and if so, how; and 5) how does the Mlh1-Mlh3 endonuclease function in MMR given that its activity seems so different from that of Mlh1-Pms1. These types of questions as well as whether post-translational modifications modulate the activity of MMR proteins and whether there are MMR proteins yet to be identified will likely be addressed over the next few years using a combination of genetics and biophysical methods.

Tremendous progress has been made in identifying eukaryotic MMR proteins, elucidating their activities and reconstituting MMR reactions in vitro, although many questions about MMR mechanisms remain to be answered. These reconstituted MMR reactions in many ways mimic the mechanisms of E. coli MMR reactions, despite the greater number of MutS-related and MutL-related heterodimeric complexes involved in eukaryotic MMR. However, eukaryotic MMR does not use post-replication DNA methylation asymmetries as a strand specificity signal, and the eukaryotic strand specificity signal has not been definitively established. An attractive hypothesis that has existed for many years due to the fact that MMR proteins catalyze nick-directed MMR is that nicks in the newly replicated strand due to discontinuous DNA synthesis serve as a strand specificity signal [27, 154]. In addition, it has been suggested that PCNA loaded at these nicks or remaining at these nicks after DNA synthesis [155] plays a role in strand specificity [74, 156], which is especially attractive given the activation of the nick-directed Mlh1-Pms1 (hMLH1-PMS2) endonuclease by PCNA loaded at nicks [80]. This hypothesis is most applicable to the lagging strand where nicks are expected to be prevalent; however, there is currently little direct evidence for this mechanism of strand recognition and it raises the question of what is the exact role of the Mlh1-Pms1 (hMLH1-PMS2) endonuclease, given that nicks are already present in the DNA. This hypothesis is likely less applicable to the leading strand that is synthesized more continuously and where PCNA is less important in DNA synthesis compared to its role in Pol δ-dependent lagging strand DNA synthesis [157]. Nicking of misincorporated ribonucleotides by RNase H2 has been postulated to provide a strand specificity signal that could act on the leading strand [158, 159]; however, the mutator phenotype caused by RNase H2 defects seem too weak for this to be a major strand discrimination mechanism [160]. MMR is also coupled to DNA replication, which could aid in the recognition of rarely occurring mispairs in vivo [77, 122](for a review see [161]). This coupling occurs by at least two different mechanisms, one of which utilizes the interaction between PCNA and the N-terminus of either Msh6 or Msh3 whereas the other mechanism(s) has not been identified [74, 75, 77]. There is some evidence that an interaction between the deuterostome-specific Msh6 PWWP domain (not present in Msh3) and a histone modification can help target Msh2-Msh6 to chromatin during S-phase, although PWWP domain mutations have not been tested to verify the significance of this interaction [162]. Finally, MMR must act on chromatin and interact with chromatin dis-assembly and assembly pathways as well as other pathways that process replication intermediates [163–166]. It is possible that studies focused on using purified proteins to reconstitute MMR reactions that are coupled to DNA replication and chromosome dis-assembly and assembly in vitro could provide new insights into MMR mechanisms and how MMR is targeted to the newly synthesized DNA strands.

Much of the investigation of MMR has focused on the enzymatic mechanisms of post-replication MMR and mutagenesis mechanisms involving MMR. Yet MMR proteins function in other processes. One example is the role of MMR proteins along with other proteins such as the Sgs1 DNA helicase in preventing recombination between divergent DNA sequences, a reaction that was first described by Radman and Huang [167–170] (see the minireview by Tlam, Kanaar and Lebbnik in this issue). This process seems likely to play an important role in preventing non-allelic homologous recombination, which might otherwise lead to genome rearrangements [171]. Little is yet known about the enzymatic mechanisms of this process, although the recent demonstration that Msh2-Msh6 can recognize mispairs in the context of Rad51-mediated D-loops represents important progress [172]. Similarly, the mechanism by which MMR proteins act on mispairs in the intermediates formed during normal homologous recombination increasing gene conversion and decreasing post-meiotic segregation has not been extensively studied. MMR proteins also act in the processes that promote the expansion of trinucleotide repeats [173, 174], an important human disease process; however, the role of MMR proteins in this process has not been fully elucidated (see the minireview by Schmidt and Pearson in this issue). Finally, MMR proteins play a role in DNA damage signaling, in promoting cell death in response to DNA damaging agents such as chemotherapeutic agents and in suppressing mutations induced by DNA damage as well as promoting mutagenesis (For representative reviews see [144, 175–177]) (see the minireviews by Li, Pearlman and Hsieh, by Crouse, and by Zanotti and Gearhart in this issue). Considerable data have been accumulated on the interaction between MMR proteins and signaling proteins, and many cell biology studies have documented defects in cell death mechanisms in MMR-defective mutants. However, the MMR-dependent cell death mechanisms such as direct signaling to initiate cell death or the induction of futile cycles of DNA repair have not been fully elucidated. These important MMR-related pathways all warrant further study.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Drs. Eva Goellner, Chris Putnam and Anjana Srivatsan for helpful discussions, help with figures and comments on the manuscript, Dr. Rodney Rothstein for advice on Figure 1, and Drs. Rick Fishel and Chris Pearson for helpful discussions. Work on MMR in my lab was supported by the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research and NIH grant GM50006.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Holliday RA. A mechanism for gene conversion in fungi. Genetic research. 1964;5:282–304. doi: 10.1017/S0016672308009476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witkin EM, Sicurella NA. Pure Clones of Lactose-Negative Mutants Obtained in Escherichia Coli after Treatment with 5-Bromouracil. Journal of molecular biology. 1964;8:610–613. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(64)80017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wildenberg J, Meselson M. Mismatch repair in heteroduplex DNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1975;72:2202–2206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.6.2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagner R, Jr, Meselson M. Repair tracts in mismatched DNA heteroduplexes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1976;73:4135–4139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glickman B, van den Elsen P, Radman M. Induced mutagenesis in dam- mutants of Escherichia coli: a role for 6-methyladenine residues in mutation avoidance. Molecular and general genetics. 1978;163:307–312. doi: 10.1007/BF00271960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glickman BW, Radman M. Escherichia coli mutator mutants deficient in methylation-instructed DNA mismatch correction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1980;77:1063–1067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.2.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGraw BR, Marinus MG. Isolation and characterization of Dam+ revertants and suppressor mutations that modify secondary phenotypes of dam-3 strains of Escherichia coli K-12. Molecular and general genetics. 1980;178:309–315. doi: 10.1007/BF00270477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegel EC, Bryson V. Mutator gene of Escherichia coli B. Journal of bacteriology. 1967;94:38–47. doi: 10.1128/jb.94.1.38-47.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radman M, Wagner R. Mismatch repair in Escherichia coli. Annual review of genetics. 1986;20:523–538. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.002515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Modrich P. DNA mismatch correction. Annual review of biochemistry. 1987;56:435–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.002251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fishel R, Kolodner R. Gene conversion in Escherichia coli: the identification of two repair pathways for mismatched nucleotides. In: Friedberg E, Bridges B, editors. UCLA Symposia on Molecular and Cellular Biology. Alan R. Liss, Inc; New York: 1983. pp. 309–324. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fishel RA, Kolodner R. An Escherichia coli cell-free system that catalyzes the repair of symmetrically methylated heteroduplex DNA. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1984;49:603–609. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1984.049.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lahue RS, Au KG, Modrich P. DNA mismatch correction in a defined system. Science. 1989;245:160–164. doi: 10.1126/science.2665076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu AL, Clark S, Modrich P. Methyl-directed repair of DNA base-pair mismatches in vitro. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1983;80:4639–4643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.15.4639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Modrich P. Mechanisms and biological effects of mismatch repair. Annual review of genetics. 1991;25:229–253. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.25.120191.001305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Modrich P. Methyl-directed DNA mismatch correction. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1989;264:6597–6600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reyes GX, Schmidt TT, Kolodner RD, Hombauer H. New insights into the mechanism of DNA mismatch repair. Chromosoma. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00412-015-0514-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hattman S, Kenny C, Berger L, Pratt K. Comparative study of DNA methylation in three unicellular eucaryotes. Journal of bacteriology. 1978;135:1156–1157. doi: 10.1128/jb.135.3.1156-1157.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Proffitt JH, Davie JR, Swinton D, Hattman S. 5-Methylcytosine is not detectable in Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA. Molecular and cellular biology. 1984;4:985–988. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.5.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szostak JW, Orr-Weaver TL, Rothstein RJ, Stahl FW. The double-strand-break repair model for recombination. Cell. 1983;33:25–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90331-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagner R, Dohet C, Jones M, Doutriaux MP, Hutchinson F, Radman M. Involvement of Escherichia coli mismatch repair in DNA replication and recombination. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1984;49:611–615. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1984.049.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holloman WK, Rowe TC, Rusche JR. Studies on nuclease alpha from Ustilago maydis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1981;256:5087–5094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bishop DK, Andersen J, Kolodner RD. Specificity of mismatch repair following transformation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with heteroduplex plasmid DNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1989;86:3713–3717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bishop DK, Kolodner RD. Repair of heteroduplex plasmid DNA after transformation into Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Molecular and cellular biology. 1986;6:3401–3409. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.10.3401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muster-Nassal C, Kolodner R. Mismatch correction catalyzed by cell-free extracts of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1986;83:7618–7622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.20.7618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Varlet I, Radman M, Brooks P. DNA mismatch repair in Xenopus egg extracts: repair efficiency and DNA repair synthesis for all single base-pair mismatches. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1990;87:7883–7887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holmes J, Jr, Clark S, Modrich P. Strand-specific mismatch correction in nuclear extracts of human and Drosophila melanogaster cell lines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1990;87:5837–5841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas DC, Roberts JD, Kunkel TA. Heteroduplex repair in extracts of human HeLa cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1991;266:3744–3751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williamson MS, Game JC, Fogel S. Meiotic gene conversion mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. I. Isolation and characterization of pms1-1 and pms1-2. Genetics. 1985;110:609–646. doi: 10.1093/genetics/110.4.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bishop DK, Williamson MS, Fogel S, Kolodner RD. The role of heteroduplex correction in gene conversion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 1987;328:362–364. doi: 10.1038/328362a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kramer W, Kramer B, Williamson MS, Fogel S. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of DNA mismatch repair gene PMS1 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae: homology of PMS1 to procaryotic MutL and HexB. Journal of bacteriology. 1989;171:5339–5346. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.10.5339-5346.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reenan RA, Kolodner RD. Isolation and characterization of two Saccharomyces cerevisiae genes encoding homologs of the bacterial HexA and MutS mismatch repair proteins. Genetics. 1992;132:963–973. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.4.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reenan RA, Kolodner RD. Characterization of insertion mutations in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae MSH1 and MSH2 genes: evidence for separate mitochondrial and nuclear functions. Genetics. 1992;132:975–985. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.4.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeyaprakash A, Welch JW, Fogel S. Mutagenesis of yeast MW104-1B strain has identified the uncharacterized PMS6 DNA mismatch repair gene locus and additional alleles of existing PMS1, PMS2 and MSH2 genes. Mutation research. 1994;325:21–29. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(94)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.New L, Liu K, Crouse GF. The yeast gene MSH3 defines a new class of eukaryotic MutS homologues. Molecular and general genetics. 1993;239:97–108. doi: 10.1007/BF00281607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marsischky GT, Filosi N, Kane MF, Kolodner R. Redundancy of Saccharomyces cerevisiae MSH3 and MSH6 in MSH2-dependent mismatch repair. Genes & development. 1996;10:407–420. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Das Gupta R, Kolodner RD. Novel dominant mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae MSH6. Nature genetics. 2000;24:53–56. doi: 10.1038/71684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ross-Macdonald P, Roeder GS. Mutation of a meiosis-specific MutS homolog decreases crossing over but not mismatch correction. Cell. 1994;79:1069–1080. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hollingsworth NM, Ponte L, Halsey C. MSH5, a novel MutS homolog, facilitates meiotic reciprocal recombination between homologs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae but not mismatch repair. Genes & development. 1995;9:1728–1739. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.14.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drummond JT, Li GM, Longley MJ, Modrich P. Isolation of an hMSH2-p160 heterodimer that restores DNA mismatch repair to tumor cells. Science. 1995;268:1909–1912. doi: 10.1126/science.7604264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palombo F, Gallinari P, Iaccarino I, Lettieri T, Hughes M, D’Arrigo A, Truong O, Hsuan JJ, Jiricny J. GTBP, a 160-kilodalton protein essential for mismatch-binding activity in human cells. Science. 1995;268:1912–1914. doi: 10.1126/science.7604265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sia EA, Kokoska RJ, Dominska M, Greenwell P, Petes TD. Microsatellite instability in yeast: dependence on repeat unit size and DNA mismatch repair genes. Molecular and cellular biology. 1997;17:2851–2858. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Acharya S, Wilson T, Gradia S, Kane MF, Guerrette S, Marsischky GT, Kolodner R, Fishel R. hMSH2 forms specific mispair-binding complexes with hMSH3 and hMSH6. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:13629–13634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palombo F, Iaccarino I, Nakajima E, Ikejima M, Shimada T, Jiricny J. hMutSbeta, a heterodimer of hMSH2 and hMSH3, binds to insertion/deletion loops in DNA. Current biology : CB. 1996;6:1181–1184. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70685-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edelmann W, Umar A, Yang K, Heyer J, Kucherlapati M, Lia M, Kneitz B, Avdievich E, Fan K, Wong E, Crouse G, Kunkel T, Lipkin M, Kolodner RD, Kucherlapati R. The DNA mismatch repair genes Msh3 and Msh6 cooperate in intestinal tumor suppression. Cancer research. 2000;60:803–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Edelmann W, Yang K, Umar A, Heyer J, Lau K, Fan K, Liedtke W, Cohen PE, Kane MF, Lipford JR, Yu N, Crouse GF, Pollard JW, Kunkel T, Lipkin M, Kolodner R, Kucherlapati R. Mutation in the mismatch repair gene Msh6 causes cancer susceptibility. Cell. 1997;91:467–477. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80433-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Wind N, Dekker M, Claij N, Jansen L, van Klink Y, Radman M, Riggins G, van der Valk M, van’t Wout K, te Riele H. HNPCC-like cancer predisposition in mice through simultaneous loss of Msh3 and Msh6 mismatch-repair protein functions. Nature genetics. 1999;23:359–362. doi: 10.1038/15544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Papadopoulos N, Nicolaides NC, Liu B, Parsons R, Lengauer C, Palombo F, D’Arrigo A, Markowitz S, Willson JK, Kinzler KW, et al. Mutations of GTBP in genetically unstable cells. Science. 1995;268:1915–1917. doi: 10.1126/science.7604266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Umar A, Risinger JI, Glaab WE, Tindall KR, Barrett JC, Kunkel TA. Functional overlap in mismatch repair by human MSH3 and MSH6. Genetics. 1998;148:1637–1646. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.4.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prolla TA, Christie DM, Liskay RM. Dual requirement in yeast DNA mismatch repair for MLH1 and PMS1, two homologs of the bacterial mutL gene. Molecular and cellular biology. 1994;14:407–415. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jeyaprakash A, Das Gupta R, Kolodner R. Saccharomyces cerevisiae pms2 mutations are alleles of MLH1, and pms2-2 corresponds to a hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma-causing missense mutation. Molecular and cellular biology. 1996;16:3008–3011. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prolla TA, Pang Q, Alani E, Kolodner RD, Liskay RM. MLH1, PMS1, and MSH2 interactions during the initiation of DNA mismatch repair in yeast. Science. 1994;265:1091–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.8066446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li GM, Modrich P. Restoration of mismatch repair to nuclear extracts of H6 colorectal tumor cells by a heterodimer of human MutL homologs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:1950–1954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang TF, Kleckner N, Hunter N. Functional specificity of MutL homologs in yeast: evidence for three Mlh1-based heterocomplexes with distinct roles during meiosis in recombination and mismatch correction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:13914–13919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Flores-Rozas H, Kolodner RD. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae MLH3 gene functions in MSH3-dependent suppression of frameshift mutations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:12404–12409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harfe BD, Minesinger BK, Jinks-Robertson S. Discrete in vivo roles for the MutL homologs Mlh2p and Mlh3p in the removal of frameshift intermediates in budding yeast. Current biology : CB. 2000;10:145–148. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cannavo E, Marra G, Sabates-Bellver J, Menigatti M, Lipkin SM, Fischer F, Cejka P, Jiricny J. Expression of the MutL homologue hMLH3 in human cells and its role in DNA mismatch repair. Cancer research. 2005;65:10759–10766. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nishant KT, Plys AJ, Alani E. A mutation in the putative MLH3 endonuclease domain confers a defect in both mismatch repair and meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2008;179:747–755. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.086645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abdullah MF, Hoffmann ER, Cotton VE, Borts RH. A role for the MutL homologue MLH2 in controlling heteroduplex formation and in regulating between two different crossover pathways in budding yeast. Cytogenetics and genome research. 2004;107:180–190. doi: 10.1159/000080596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prolla TA, Baker SM, Harris AC, Tsao JL, Yao X, Bronner CE, Zheng B, Gordon M, Reneker J, Arnheim N, Shibata D, Bradley A, Liskay RM. Tumour susceptibility and spontaneous mutation in mice deficient in Mlh1, Pms1 and Pms2 DNA mismatch repair. Nature genetics. 1998;18:276–279. doi: 10.1038/ng0398-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Raschle M, Marra G, Nystrom-Lahti M, Schar P, Jiricny J. Identification of hMutLbeta, a heterodimer of hMLH1 and hPMS1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:32368–32375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Campbell CS, Hombauer H, Srivatsan A, Bowen N, Gries K, Desai A, Putnam CD, Kolodner RD. Mlh2 is an accessory factor for DNA mismatch repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS genetics. 2014;10:e1004327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Szankasi P, Smith GR. A DNA exonuclease induced during meiosis of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1992;267:3014–3023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Szankasi P, Smith GR. A role for exonuclease I from S. pombe in mutation avoidance and mismatch correction. Science. 1995;267:1166–1169. doi: 10.1126/science.7855597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tishkoff DX, Boerger AL, Bertrand P, Filosi N, Gaida GM, Kane MF, Kolodner RD. Identification and characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae EXO1, a gene encoding an exonuclease that interacts with MSH2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:7487–7492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tran PT, Simon JA, Liskay RM. Interactions of Exo1p with components of MutLalpha in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:9760–9765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161175998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schmutte C, Sadoff MM, Shim KS, Acharya S, Fishel R. The interaction of DNA mismatch repair proteins with human exonuclease I. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:33011–33018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102670200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Amin NS, Nguyen MN, Oh S, Kolodner RD. exo1-Dependent mutator mutations: model system for studying functional interactions in mismatch repair. Molecular and cellular biology. 2001;21:5142–5155. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.15.5142-5155.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wei K, Clark AB, Wong E, Kane MF, Mazur DJ, Parris T, Kolas NK, Russell R, Hou H, Jr, Kneitz B, Yang G, Kunkel TA, Kolodner RD, Cohen PE, Edelmann W. Inactivation of Exonuclease 1 in mice results in DNA mismatch repair defects, increased cancer susceptibility, and male and female sterility. Genes & development. 2003;17:603–614. doi: 10.1101/gad.1060603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kadyrov FA, Dzantiev L, Constantin N, Modrich P. Endonucleolytic function of MutLalpha in human mismatch repair. Cell. 2006;126:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lau PJ, Flores-Rozas H, Kolodner RD. Isolation and characterization of new proliferating cell nuclear antigen (POL30) mutator mutants that are defective in DNA mismatch repair. Molecular and cellular biology. 2002;22:6669–6680. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.19.6669-6680.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Umar A, Buermeyer AB, Simon JA, Thomas DC, Clark AB, Liskay RM, Kunkel TA. Requirement for PCNA in DNA mismatch repair at a step preceding DNA resynthesis. Cell. 1996;87:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gu L, Hong Y, McCulloch S, Watanabe H, Li GM. ATP-dependent interaction of human mismatch repair proteins and dual role of PCNA in mismatch repair. Nucleic acids research. 1998;26:1173–1178. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.5.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Flores-Rozas H, Clark D, Kolodner RD. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen and Msh2p-Msh6p interact to form an active mispair recognition complex. Nature genetics. 2000;26:375–378. doi: 10.1038/81708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Clark AB, Valle F, Drotschmann K, Gary RK, Kunkel TA. Functional interaction of proliferating cell nuclear antigen with MSH2-MSH6 and MSH2-MSH3 complexes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:36498–36501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000513200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kleczkowska HE, Marra G, Lettieri T, Jiricny J. hMSH3 and hMSH6 interact with PCNA and colocalize with it to replication foci. Genes & development. 2001;15:724–736. doi: 10.1101/gad.191201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hombauer H, Campbell CS, Smith CE, Desai A, Kolodner RD. Visualization of eukaryotic DNA mismatch repair reveals distinct recognition and repair intermediates. Cell. 2011;147:1040–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee SD, Alani E. Analysis of interactions between mismatch repair initiation factors and the replication processivity factor PCNA. Journal of molecular biology. 2006;355:175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dzantiev L, Constantin N, Genschel J, Iyer RR, Burgers PM, Modrich P. A defined human system that supports bidirectional mismatch-provoked excision. Molecular cell. 2004;15:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pluciennik A, Dzantiev L, Iyer RR, Constantin N, Kadyrov FA, Modrich P. PCNA function in the activation and strand direction of MutLalpha endonuclease in mismatch repair. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:16066–16071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010662107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Goellner EM, Smith CE, Campbell CS, Hombauer H, Desai A, Putnam CD, Kolodner RD. PCNA and Msh2-Msh6 activate an Mlh1-Pms1 endonuclease pathway required for Exo1-independent mismatch repair. Molecular cell. 2014;55:291–304. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Xie Y, Counter C, Alani E. Characterization of the repeat-tract instability and mutator phenotypes conferred by a Tn3 insertion in RFC1, the large subunit of the yeast clamp loader. Genetics. 1999;151:499–509. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.2.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Longley MJ, Pierce AJ, Modrich P. DNA polymerase delta is required for human mismatch repair in vitro. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1997;272:10917–10921. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lin YL, Shivji MK, Chen C, Kolodner R, Wood RD, Dutta A. The evolutionarily conserved zinc finger motif in the largest subunit of human replication protein A is required for DNA replication and mismatch repair but not for nucleotide excision repair. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:1453–1461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang Y, Yuan F, Presnell SR, Tian K, Gao Y, Tomkinson AE, Gu L, Li GM. Reconstitution of 5′-directed human mismatch repair in a purified system. Cell. 2005;122:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Constantin N, Dzantiev L, Kadyrov FA, Modrich P. Human mismatch repair: reconstitution of a nick-directed bidirectional reaction. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:39752–39761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509701200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yuan F, Gu L, Guo S, Wang C, Li GM. Evidence for involvement of HMGB1 protein in human DNA mismatch repair. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:20935–20940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401931200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liu Y, Kadyrov FA, Modrich P. PARP-1 enhances the mismatch-dependence of 5′-directed excision in human mismatch repair in vitro. DNA repair. 2011;10:1145–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Traver S, Coulombe P, Peiffer I, Hutchins JR, Kitzmann M, Latreille D, Mechali M. MCM9 Is Required for Mammalian DNA Mismatch Repair. Molecular cell. 2015;59:831–839. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang Y, Yuan F, Wang D, Gu L, Li GM. Identification of regulatory factor X as a novel mismatch repair stimulatory factor. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:12730–12735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800460200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Erie DA, Weninger KR. Single molecule studies of DNA mismatch repair. DNA repair. 2014;20:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee JB, Cho WK, Park J, Jeon Y, Kim D, Lee SH, Fishel R. Single-molecule views of MutS on mismatched DNA. DNA repair. 2014;20:82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gradia S, Subramanian D, Wilson T, Acharya S, Makhov A, Griffith J, Fishel R. hMSH2-hMSH6 forms a hydrolysis-independent sliding clamp on mismatched DNA. Molecular cell. 1999;3:255–261. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80316-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fishel R. Mismatch repair, molecular switches, and signal transduction. Genes & development. 1998;12:2096–2101. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.14.2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mendillo ML, Hargreaves VV, Jamison JW, Mo AO, Li S, Putnam CD, Woods VL, Jr, Kolodner RD. A conserved MutS homolog connector domain interface interacts with MutL homologs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:22223–22228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912250106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mazur DJ, Mendillo ML, Kolodner RD. Inhibition of Msh6 ATPase activity by mispaired DNA induces a Msh2(ATP)-Msh6(ATP) state capable of hydrolysis-independent movement along DNA. Molecular cell. 2006;22:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mendillo ML, Mazur DJ, Kolodner RD. Analysis of the interaction between the Saccharomyces cerevisiae MSH2-MSH6 and MLH1-PMS1 complexes with DNA using a reversible DNA end-blocking system. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:22245–22257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407545200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wilson T, Guerrette S, Fishel R. Dissociation of mismatch recognition and ATPase activity by hMSH2-hMSH3. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:21659–21664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lamers MH, Perrakis A, Enzlin JH, Winterwerp HH, de Wind N, Sixma TK. The crystal structure of DNA mismatch repair protein MutS binding to a G x T mismatch. Nature. 2000;407:711–717. doi: 10.1038/35037523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Obmolova G, Ban C, Hsieh P, Yang W. Crystal structures of mismatch repair protein MutS and its complex with a substrate DNA. Nature. 2000;407:703–710. doi: 10.1038/35037509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Warren JJ, Pohlhaus TJ, Changela A, Iyer RR, Modrich PL, Beese LS. Structure of the human MutSalpha DNA lesion recognition complex. Molecular cell. 2007;26:579–592. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gupta S, Gellert M, Yang W. Mechanism of mismatch recognition revealed by human MutSbeta bound to unpaired DNA loops. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2012;19:72–78. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Srivatsan A, Bowen N, Kolodner RD. Mispair-specific recruitment of the Mlh1-Pms1 complex identifies repair substrates of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Msh2-Msh3 complex. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2014;289:9352–9364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.552190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Blackwell LJ, Wang S, Modrich P. DNA chain length dependence of formation and dynamics of hMutSalpha.hMutLalpha.heteroduplex complexes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:33233–33240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105076200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Groothuizen FS, Winkler I, Cristovao M, Fish A, Winterwerp HH, Reumer A, Marx AD, Hermans N, Nicholls RA, Murshudov GN, Lebbink JH, Friedhoff P, Sixma TK. MutS/MutL crystal structure reveals that the MutS sliding clamp loads MutL onto DNA. Elife. 2015;4:e06744. doi: 10.7554/eLife.06744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Habraken Y, Sung P, Prakash L, Prakash S. ATP-dependent assembly of a ternary complex consisting of a DNA mismatch and the yeast MSH2-MSH6 and MLH1-PMS1 protein complexes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:9837–9841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Raschle M, Dufner P, Marra G, Jiricny J. Mutations within the hMLH1 and hPMS2 subunits of the human MutLalpha mismatch repair factor affect its ATPase activity, but not its ability to interact with hMutSalpha. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:21810–21820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108787200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hess MT, Mendillo ML, Mazur DJ, Kolodner RD. Biochemical basis for dominant mutations in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae MSH6 gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:558–563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510078103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hargreaves VV, Shell SS, Mazur DJ, Hess MT, Kolodner RD. Interaction between the Msh2 and Msh6 nucleotide-binding sites in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Msh2-Msh6 complex. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:9301–9310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.096388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Smith CE, Bowen N, Graham WJt, Goellner EM, Srivatsan A, Kolodner RD. Activation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mlh1-Pms1 Endonuclease in a Reconstituted Mismatch Repair System. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2015;290:21580–21590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.662189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kadyrov FA, Holmes SF, Arana ME, Lukianova OA, O’Donnell M, Kunkel TA, Modrich P. Saccharomyces cerevisiae MutLalpha is a mismatch repair endonuclease. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:37181–37190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707617200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gueneau E, Dherin C, Legrand P, Tellier-Lebegue C, Gilquin B, Bonnesoeur P, Londino F, Quemener C, Le Du MH, Marquez JA, Moutiez M, Gondry M, Boiteux S, Charbonnier JB. Structure of the MutLalpha C-terminal domain reveals how Mlh1 contributes to Pms1 endonuclease site. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2013;20:461–468. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Smith CE, Mendillo ML, Bowen N, Hombauer H, Campbell CS, Desai A, Putnam CD, Kolodner RD. Dominant Mutations in S. cerevisiae PMS1 Identify the Mlh1-Pms1 Endonuclease Active Site and an Exonuclease 1-Independent Mismatch Repair Pathway. PLoS genetics. 2013;9:e1003869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Goellner EM, Putnam CD, Kolodner RD. Exonuclease 1-dependent and independent mismatch repair. DNA repair. 2015;32:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ranjha L, Anand R, Cejka P. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mlh1-Mlh3 heterodimer is an endonuclease that preferentially binds to Holliday junctions. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2014;289:5674–5686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.533810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Rogacheva MV, Manhart CM, Chen C, Guarne A, Surtees J, Alani E. Mlh1-Mlh3, a meiotic crossover and DNA mismatch repair factor, is a Msh2-Msh3-stimulated endonuclease. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2014;289:5664–5673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.534644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Bowen N, Smith CE, Srivatsan A, Willcox S, Griffith JD, Kolodner RD. Reconstitution of long and short patch mismatch repair reactions using Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:18472–18477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318971110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Genschel J, Modrich P. Mechanism of 5′-directed excision in human mismatch repair. Molecular cell. 2003;12:1077–1086. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00428-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Geng H, Du C, Chen S, Salerno V, Manfredi C, Hsieh P. In vitro studies of DNA mismatch repair proteins. Analytical biochemistry. 2011;413:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Tran HT, Gordenin DA, Resnick MA. The 3′-->5′ exonucleases of DNA polymerases delta and epsilon and the 5′-->3′ exonuclease Exo1 have major roles in postreplication mutation avoidance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Molecular and cellular biology. 1999;19:2000–2007. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kadyrov FA, Genschel J, Fang Y, Penland E, Edelmann W, Modrich P. A possible mechanism for exonuclease 1-independent eukaryotic mismatch repair. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:8495–8500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903654106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hombauer H, Srivatsan A, Putnam CD, Kolodner RD. Mismatch repair, but not heteroduplex rejection, is temporally coupled to DNA replication. Science. 2011;334:1713–1716. doi: 10.1126/science.1210770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Levinson G, Gutman GA. High frequencies of short frameshifts in poly-CA/TG tandem repeats borne by bacteriophage M13 in Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic acids research. 1987;15:5323–5338. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.13.5323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Strand M, Prolla TA, Liskay RM, Petes TD. Destabilization of tracts of simple repetitive DNA in yeast by mutations affecting DNA mismatch repair. Nature. 1993;365:274–276. doi: 10.1038/365274a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Aaltonen LA, Peltomaki P, Leach FS, Sistonen P, Pylkkanen L, Mecklin JP, Jarvinen H, Powell SM, Jen J, Hamilton SR, et al. Clues to the pathogenesis of familial colorectal cancer. Science. 1993;260:812–816. doi: 10.1126/science.8484121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Peltomaki P, Aaltonen LA, Sistonen P, Pylkkanen L, Mecklin JP, Jarvinen H, Green JS, Jass JR, Weber JL, Leach FS, et al. Genetic mapping of a locus predisposing to human colorectal cancer. Science. 1993;260:810–812. doi: 10.1126/science.8484120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Fishel R, Lescoe MK, Rao MR, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Garber J, Kane M, Kolodner R. The human mutator gene homolog MSH2 and its association with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. Cell. 1993;75:1027–1038. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90546-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kolodner RD, Hall NR, Lipford J, Kane MF, Rao MR, Morrison P, Wirth L, Finan PJ, Burn J, Chapman P. Structure of the human MSH2 locus and analysis of two Muir-Torre kindreds for msh2 mutations. Genomics. 1994;24:516–526. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Lindblom A, Tannergard P, Werelius B, Nordenskjold M. Genetic mapping of a second locus predisposing to hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer. Nature genetics. 1993;5:279–282. doi: 10.1038/ng1193-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Bronner CE, Baker SM, Morrison PT, Warren G, Smith LG, Lescoe MK, Kane M, Earabino C, Lipford J, Lindblom A, et al. Mutation in the DNA mismatch repair gene homologue hMLH1 is associated with hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer. Nature. 1994;368:258–261. doi: 10.1038/368258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kolodner RD, Hall NR, Lipford J, Kane MF, Morrison PT, Finan PJ, Burn J, Chapman P, Earabino C, Merchant E, et al. Structure of the human MLH1 locus and analysis of a large hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma kindred for mlh1 mutations. Cancer research. 1995;55:242–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]