Abstract

Studies of cancer heterogeneity have received considerable attention recently, because the presence or absence of resistant sub-clones may determine whether or not certain therapeutic treatments are effective. Previously, we have reported G64, a co-regulated gene module composed of 64 different genes, can differentiate tumor intra- or inter-subpopulations in lung adenocarcinomas (LADCs). Here, we investigated whether the G64 module genes were also expressed distinctively in different subpopulations of other cancers. RNA sequencing-based transcriptome data derived from 22 cancers, except LADC, were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). Interestingly, the 22 cancers also expressed the G64 genes in a correlated manner, as observed previously in an LADC study. Considering that gene expression levels were continuous among different tumor samples, tumor subpopulations were investigated using extreme expressional ranges of G64—i.e., tumor subpopulation with the lowest 15% of G64 expression, tumor subpopulation with the highest 15% of G64 expression, and tumor subpopulation with intermediate expression. In each of the 22 cancers, we examined whether patient survival was different among the three different subgroups and found that G64 could differentiate tumor subpopulations in six other cancers, including sarcoma, kidney, brain, liver, and esophageal cancers.

Keywords: differentially expressed genes, lung adenocarcinoma, single cell analysis, survival analyses, tumor heterogeneity

Introduction

Different tumors or cancers in different patients have distinct genetic and cellular profiles, including kinds of genetic mutations, patterns of gene expression, and metastatic potential, which is often called cancer heterogeneity. The heterogeneity occurs both within and between tumors and leads to intra-tumor heterogeneity and inter-tumor heterogeneity, respectively [1,2,3]. Understanding cancer heterogeneity has recently been one of the important research subjects, because it is the base of difficulty in developing effective cancer treatments.

Tumor heterogeneity is basically due to the different origins of tumor cells or tissues. Various biological factors, such as smoking, gender, age, or hormonal status, can influence cancer initiation or progression, as well. Fundamentally, there are genetic variations among the hosts, even for the same cancer [4,5,6]. Astonishingly rapid development of massively parallel sequencing, alternatively called nextgeneration sequencing technologies, has recently elucidated the extent of tumor heterogeneity, and several hundred somatic mutations and structural variants that drive cancers have been identified [7,8,9].

Previously, we reported the characterization of the heterogeneity of human lung adenocarcinomas (LADCs) from patient-derived xenografts via single-cell transcriptome sequencing [10]. These cells were categorized into two separate subpopulations based on their expression of a module gene named G64. We found that G64 upregulation/ down-regulation was also present in patient tissue samples obtained from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), with G64 up-regulation corresponding to poor survival and associated with multiple clinical variables, such as smoking status (which exhibited the highest correlation) and tumor stage.

In the present study, we investigated if G64 can differentiate tumor subpopulations in other cancers, as well.

Methods

Websites for downloading RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data for 22 cancer datasets

The TCGA website (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/tcgaHome2.jsp) was used for downloading RNA-seq-based transcriptome data and patient survival information for 22 cancers. The RNA-seq data downloaded for each cancer are listed in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1. As described in the previous report [10], expression values of 0<FPKM (fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped)<0.1 were all converted to 0.1 to avoid the infinity problem. Each FPKM value of each gene was divided by the average FPKM estimated for the total patient samples where the gene is expressed and was log2-transformed, for which heat map analysis combined with hierarchical clustering was performed with the 'hclust' function of R package (https://stat.ethz.ch/R-manual/R-patched/library/stats/html/hclust.html).

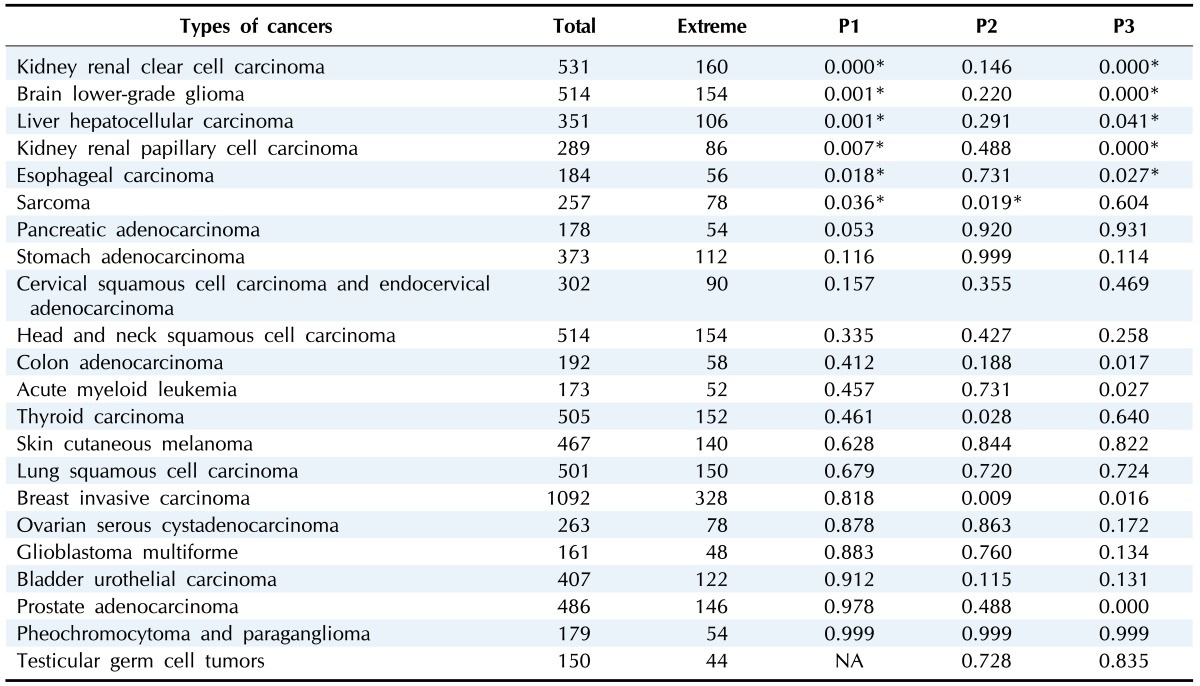

Table 1. List of the 22 cancers.

P1, P2, and P3 indicate three different comparisons: the highest 15% versus the lowest 15%, the lowest 15% versus the intermediate, and the highest 15% versus the intermediate, respectively.

*Significant comparisons of p<0.05.

Statistical tests

We used R (v 3.1.3) for all statistical tests (https://cran.r-project.org/). Using the factoMineR (http://factominer.free.fr) and rgl (https://r-forge.r-project.org/projects/rgl/) packages, principal component analysis (PCA) and visualization were performed [11]. The survival packages were used (http://r-forge.r-project.org) to compare patient survival rates and draw Kaplan-Meier plots. The coxph function in the survival packages was used for performing the Cox regression analysis [12,13].

Results

Selection of two extreme patient groups and one intermediate group determined by G64 expression

The G64 genes were originally identified by their coregulated expression pattern in single cells derived from a single LADC tumor region [10]. Interestingly, we have reported that 488 LADC patients samples downloaded from the TCGA were also separated into two distinct groups by the G64 genes. In the present work, we examined whether G64 could be a classifier for other cancers, as well. For this analysis, 22 RNA-seq-based transcriptome data with a sample size ≥150 were retrieved from the TCGA. The threshold of 150 was selected, because it was considered to be the minimum number of samples for statistical tests between different groups (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1).

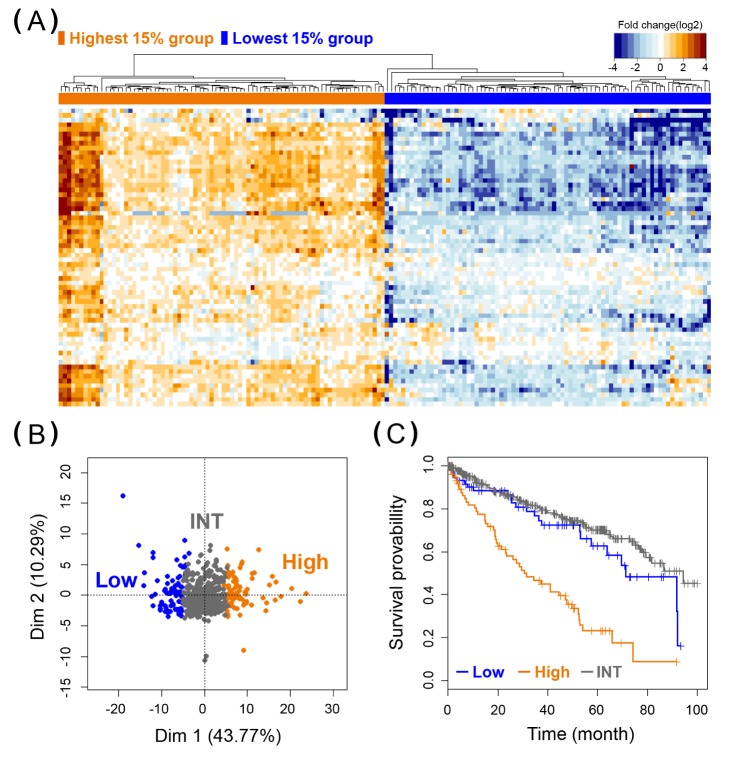

As done in the previous LADC study [10], heat map analysis was performed for each cancer type to see how patient samples were separated by G64 (Supplementary Fig. 1). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, the co-regulated patterns of G64 expression were confirmed in all types of cancers we tested. However, distinct two-group separations were not as evident as the case for LADC. Therefore, we classifies patient samples further into three different categories by using a 15% extreme threshold of G64 expression (Supplementary Fig. 2): the highest 15% group, the lowest 15% group, and an intermediate group. For this purpose, the patients were sorted out by the intensity of the average FPKM values of the G64 genes expressed in each patient. As a result, for instance, among a total of 531 kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC) samples, 160 samples were assigned into the two extreme groups—the highest 15% and the lowest 15%—whereas the remaining 371 samples were classified into the intermediate group.

G64 up-regulating cancers tend to have a poor prognosis in six different cancers

We next investigated whether patient survival was significantly different in these three groups classified by the average intensity of G64 expression. Patient survival rates were compared among the three patient groups for each of the 22 cancers. As done in the LADC study, we performed Kaplan-Meier analysis using the patients' survival data obtained from the TCGA in each type of cancer. Survival rates were compared between the lowest 15% versus highest 15% groups (i.e., P1 comparison in Table 1), the lowest 15% versus intermediate groups (i.e., P2 comparison in Table 1), and the intermediate versus highest 15% groups (i.e., P3 comparison in Table 1). PCA confirmed the groups' separations by G64 expression (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7). As summarized in Table 1, only six cancers were shown to have statistically significant differences between groups, including KIRC, brain lower grade glioma, liver hepatocellular carcinoma, kidney renal papilloma cell carcinoma, esophageal carcinoma, and sarcoma. In all comparisons between groups in these 6 cancers, G64 up-regulation was consistently observed to be associated with worse patient prognosis in the Cox regression analysis (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8).

Fig. 1. Heat map, principal component analysis (PCA), and Kaplan Meier (KM) plot analysis of G64 in kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC). (A) Heat map was plotted using the 160 samples corresponding to the highest 15% and lowest 15% of G64 expression among the total of 531 KIRC samples. (B) A PCA plot of G64 expression was performed using the 531 KIRC samples. Low, the lowest 15% group; INT, intermediate group; High, the highest 15% group. (C) KM analysis of the 531 KIRC samples based on the average G64 expression. Cox regression analysis was used to investigate whether the survival duration of the two different groups was significantly different (p<0.001), as shown in Table 1.

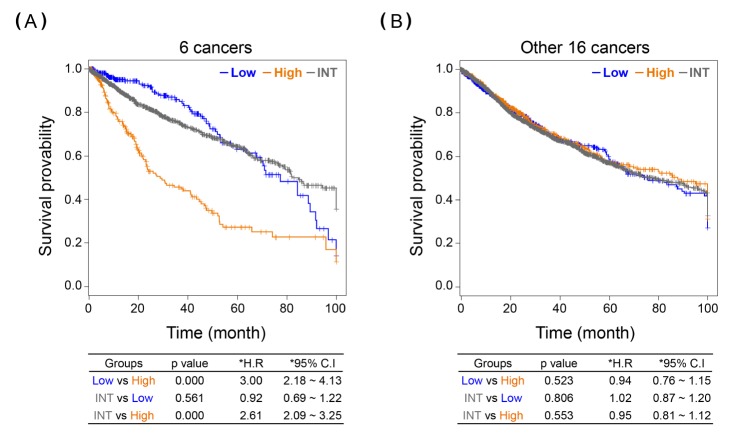

The 22 cancers were subsequently divided into two batches: i.e., six survival-differentiating cancers and 16 survivalnon- differentiating cancers. After the RNA-seq samples from the 22 cancers were collected as separate batches, we examined the aspect of survival difference by G64 expression in each batch. Consequently, the survival-differentiating batch, mixing up six different cancer samples (531 + 514 + 351 + 289 + 184 + 257 = 2,126 samples), clearly maintained the survival differentiation among the lowest 15%, the highest 15%, and the intermediate groups (Fig. 2), whereas the survival-non-differentiating batch, mixing up 16 different cancer samples (178 + 373 + 302 + …. + 179 + 150 = 5943 samples), showed no survival difference among the three different groups determined by G64 expression levels (Fig. 2). Taken together, the G64 genes can differentiate cancer samples by their survival rate differences in cancers other than LADC.

Fig. 2. KM analysis of combined samples of cancers on expression of G64. (A) KM plot of the combined six samples of the survival-differentiating cancers by G64, including kidney renal clear cell carcinoma, brain lower-grade glioma, liver hepatocellular carcinoma, kidney renal papilloma cell carcinoma, esophageal carcinoma, and sarcoma (see Table 1, upper six cancers). (B) KM plot of the 16 remaining samples of the survivalnon- differentiating cancers (see Table 1, lower 16 cancers). Low, the lowest 15% group; INT, intermediate group; High, the highest 15% group; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

Basically, it was an interesting finding that genes, named the G64 module in our previous study (i.e., a highly coregulated gene group), can classify not only single cells derived from a single tumor but also tumors that have originated from several different cancers. Various biomarkers have been identified and developed for molecular diagnostics in cancers. In fact, numerous genes included in the list of the G64 module have already been identified as cancer diagnostic or prognostic markers by several independent researchers [14,15,16]. For instance, CDCA5 and NCAPH have been characterized to be highly expressed in lung cancers [17,18]. Our previous study showed that cell cycle genes were a main functional GO category in the G64 module. Consistently, dysregulation of the cell cycle has long been proven to be a critical process causing cancers [19,20,21,22]. However, to our knowledge, it was the first finding ever that G64 genes were co-regulated in various cancers, and patient prognosis can be differentiated by these genes. Here, we clearly showed that the G64 module can be a good biomarker, predicting cancer prognosis at least for six different cancers—i.e., seven different cancers if LADC is included.

It is unclear what common molecular characteristics the seven cancers (i.e., 6 cancers in the present study and LADC) share together other than co-regulated G64 expression. The seven cancers must be initiated and progress by different genetic or environmental causes and pathways, and there is no proper explanation for the common subpopulation differentiation carried through G64 expression. It is also hard to explain at this moment why the 64 genes are co-regulated on an inter-tumoral level and intra-tumoral level and why up-regulating patients tend to have a poor prognosis. One possibility we can think of is that expression of these genes may be associated with drug metabolism, contributing to drug sensitivity or drug resistance. It will be interesting to study further how expression of G64 is changed during the recurrence of cancers. Taken together, G64 genes would be a good candidate of developing prognostic markers for multiple cancers.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a 2015 research grant from Kangwon National University (No. 520150328) to S.S.C.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data, including one table and eight figures, can be found with this article online at http://www.genominfo.org/src/sm/gni-13-132-s001.pdf.

Cancer names and their sample IDs of TCGA used in the analysis

Heat map analysis of the G64 expression in the 22 cancers.

Density plots of the average of the G64 expressions in each 22 cancer. BLCA, bladder urothelial carcinoma; BRCA, breast invasive CESC, Cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma; COAD, colon adenocarcinoma; ESCA, esophageal carcinoma; GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; HNSC, head and neck ESCA, esophageal carcinoma; GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; HNSC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; KIRC, kidney renal clear cell carcinoma; KIRP, squamous cell carcinoma; KIRC, kidney renal clear KIRP, squamous cell carcinoma; KIRC, kidney renal clear KIRP, kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma; LAML, acute myeloid leukemia; LGG, brain lower grade glioma; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; LUSC, lung squamous cell OV, ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma; PAAD, pancreatic adenocarcinoma; PCPG, pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma; PRAD, prostate adenocarcinoma; SARC, sarcoma; SKCM, skin cutaneous melanoma; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; TGCT, testicular germ cell tumors; THCA, thyroid carcinoma.

(A—C) Heat map analysis using the 154 samples corresponding to the highest 15% and the lowest 15% of the G64 expression among the total 514 brain lower grade glioma samples. Low, the lowest 15% group; INT, intermediate group; High, the highest 15% group.

Heat map analysis using the 106 samples corresponding to the highest 15% and the lowest 15% of the G64 expression among the total 351 liver hepatocellular carcinoma samples. Low, the lowest 15% group; INT, intermediate group; High, the highest 15% group.

Heat map analysis using the 86 samples corresponding to the highest 15% and the lowest 15% of the G64 expression among the total 289 kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma samples. Low, the lowest 15% group; INT, intermediate group; High, the highest 15% group.

Heat map analysis using the 56 samples corresponding to the highest 15% and the lowest 15% of the G64 expression among the total 184 esophageal carcinoma samples. Low, the lowest 15% group; INT, intermediate group; High, the highest 15% group.

Heat map analysis using the 78 samples corresponding to the highest 15% and the lowest 15% of the G64 expression among the total 257 sarcoma samples. Low, the lowest 15% group; INT, intermediate group; High, the highest 15% group.

KM analysis of the 16 survival-non-differentiating cancers based on the G64 expression. BLCA, bladder urothelial carcinoma; BRCA, breast invasive carcinoma; CESC, Cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma; COAD, colon adenocarcinoma; GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; HNSC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; LAML, acute myeloid leukemia; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; OV, ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma; PAAD, pancreatic adenocarcinoma; PCPG, pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma; PRAD, prostate adenocarcinoma; SKCM, skin cutaneous melanoma; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; TGCT, testicular germ cell tumors; THCA, thyroid carcinoma; Low, the lowest 15% group; INT, intermediate group; High, the highest 15% group.

References

- 1.Bedard PL, Hansen AR, Ratain MJ, Siu LL. Tumour heterogeneity in the clinic. Nature. 2013;501:355–364. doi: 10.1038/nature12627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cusnir M, Cavalcante L. Inter-tumor heterogeneity. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8:1143–1145. doi: 10.4161/hv.21203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyng H, Vorren AO, Sundfor K, Taksdal I, Lien HH, Kaalhus O, et al. Intra- and intertumor heterogeneity in blood perfusion of human cervical cancer before treatment and after radiotherapy. Int J Cancer. 2001;96:182–190. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang YH, Yuen RK, Jin X, Wang M, Chen N, Wu X, et al. Detection of clinically relevant genetic variants in autism spectrum disorder by whole-genome sequencing. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;93:249–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinto N, Dolan ME. Clinically relevant genetic variations in drug metabolizing enzymes. Curr Drug Metab. 2011;12:487–497. doi: 10.2174/138920011795495321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yasuda SU, Zhang L, Huang SM. The role of ethnicity in variability in response to drugs: focus on clinical pharmacology studies. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:417–423. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, Ye K, Niu B, Lu C, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502:333–339. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roukos D, Batsis C, Baltogiannis G. Assessing tumor heterogeneity and emergence mutations using next-generation sequencing for overcoming cancer drugs resistance. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2012;12:1245–1248. doi: 10.1586/era.12.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Timmermann B, Kerick M, Roehr C, Fischer A, Isau M, Boerno ST, et al. Somatic mutation profiles of MSI and MSS colorectal cancer identified by whole exome next generation sequencing and bioinformatics analysis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Min JW, Kim WJ, Han JA, Jung YJ, Kim KT, Park WY, et al. Identification of Distinct Tumor Subpopulations in Lung Adenocarcinoma via Single-Cell RNA-seq. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyagi A, Takahashi H, Takahara K, Hirabayashi T, Nishimura Y, Tezuka T, et al. Principal component and hierarchical clustering analysis of metabolites in destructive weeds; polygonaceous plants. Metabolomics. 2010;6:146–155. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc Series B Methodol. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Efron B. Logistic regression, survival analysis, and the Kaplan-Meier curve. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;83:414–425. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayama S, Daigo Y, Yamabuki T, Hirata D, Kato T, Miyamoto M, et al. Phosphorylation and activation of cell division cycle associated 8 by aurora kinase B plays a significant role in human lung carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4113–4122. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soria JC, Jang SJ, Khuri FR, Hassan K, Liu D, Hong WK, et al. Overexpression of cyclin B1 in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer and its clinical implication. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4000–4004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong X, Guan X, Dong Q, Yang S, Liu W, Zhang L. Examining Nek2 as a better proliferation marker in non-small cell lung cancer prognosis. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:7155–7162. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1935-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beer D, Taylor J, Chen G, Kim S. United States patent US 20120295803 A1. Lung cancer signature. 2012 Nov 22;

- 18.Nguyen MH, Koinuma J, Ueda K, Ito T, Tsuchiya E, Nakamura Y, et al. Phosphorylation and activation of cell division cycle associated 5 by mitogen-activated protein kinase play a crucial role in human lung carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5337–5347. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodwin G, Johns E, Lehn D, Landsman D, Wright J, Ferrari S, et al. A cell cycle regulator potentially involved in genesis of many tumor types. Biol Chem. 1986;261:2274. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan H, Griep AE. Altered cell cycle regulation in the lens of HPV-16 E6 or E7 transgenic mice: implications for tumor suppressor gene function in development. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1285–1299. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.11.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sherr CJ. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274:1672–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitfield ML, Sherlock G, Saldanha AJ, Murray JI, Ball CA, Alexander KE, et al. Identification of genes periodically expressed in the human cell cycle and their expression in tumors. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1977–2000. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-02-0030.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cancer names and their sample IDs of TCGA used in the analysis

Heat map analysis of the G64 expression in the 22 cancers.

Density plots of the average of the G64 expressions in each 22 cancer. BLCA, bladder urothelial carcinoma; BRCA, breast invasive CESC, Cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma; COAD, colon adenocarcinoma; ESCA, esophageal carcinoma; GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; HNSC, head and neck ESCA, esophageal carcinoma; GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; HNSC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; KIRC, kidney renal clear cell carcinoma; KIRP, squamous cell carcinoma; KIRC, kidney renal clear KIRP, squamous cell carcinoma; KIRC, kidney renal clear KIRP, kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma; LAML, acute myeloid leukemia; LGG, brain lower grade glioma; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; LUSC, lung squamous cell OV, ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma; PAAD, pancreatic adenocarcinoma; PCPG, pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma; PRAD, prostate adenocarcinoma; SARC, sarcoma; SKCM, skin cutaneous melanoma; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; TGCT, testicular germ cell tumors; THCA, thyroid carcinoma.

(A—C) Heat map analysis using the 154 samples corresponding to the highest 15% and the lowest 15% of the G64 expression among the total 514 brain lower grade glioma samples. Low, the lowest 15% group; INT, intermediate group; High, the highest 15% group.

Heat map analysis using the 106 samples corresponding to the highest 15% and the lowest 15% of the G64 expression among the total 351 liver hepatocellular carcinoma samples. Low, the lowest 15% group; INT, intermediate group; High, the highest 15% group.

Heat map analysis using the 86 samples corresponding to the highest 15% and the lowest 15% of the G64 expression among the total 289 kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma samples. Low, the lowest 15% group; INT, intermediate group; High, the highest 15% group.

Heat map analysis using the 56 samples corresponding to the highest 15% and the lowest 15% of the G64 expression among the total 184 esophageal carcinoma samples. Low, the lowest 15% group; INT, intermediate group; High, the highest 15% group.

Heat map analysis using the 78 samples corresponding to the highest 15% and the lowest 15% of the G64 expression among the total 257 sarcoma samples. Low, the lowest 15% group; INT, intermediate group; High, the highest 15% group.

KM analysis of the 16 survival-non-differentiating cancers based on the G64 expression. BLCA, bladder urothelial carcinoma; BRCA, breast invasive carcinoma; CESC, Cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma; COAD, colon adenocarcinoma; GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; HNSC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; LAML, acute myeloid leukemia; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; OV, ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma; PAAD, pancreatic adenocarcinoma; PCPG, pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma; PRAD, prostate adenocarcinoma; SKCM, skin cutaneous melanoma; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; TGCT, testicular germ cell tumors; THCA, thyroid carcinoma; Low, the lowest 15% group; INT, intermediate group; High, the highest 15% group.