Abstract

MutLα is a key component of the DNA mismatch repair system in eukaryotes. The DNA mismatch repair system has several genetic stabilization functions. Of these functions, DNA mismatch repair is the major one. The loss of MutLα abolishes DNA mismatch repair, thereby predisposing humans to cancer. MutLα has an endonuclease activity that is required for DNA mismatch repair. The endonuclease activity of MutLα depends on the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif which is a part of the active site of the nuclease. This motif is also present in many bacterial MutL and eukaryotic MutLγ proteins, DNA mismatch repair system factors that are homologous to MutLα. Recent studies have shown that yeast MutLγ and several MutL proteins containing the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif possess endonuclease activities. Here, we review the endonuclease activities of MutLα and its homologs in the context of DNA mismatch repair.

1. Introduction

The DNA mismatch repair (MMR) system genes have been found in the majority of living organisms, indicating that this DNA repair system is important for maintaining life. Studies in model organisms and human cells have demonstrated that the MMR system has multiple functions in DNA metabolism ((1–16), and other reviews in this special issue). Most functions of the MMR system promote genome stability, but some of its functions contribute to the instability of certain genomic loci (7,17,18). Repair of DNA mismatches that are formed during replication and homologous recombination is the major genetic stabilization function of the MMR system (19–25). MMR is more efficient on the lagging strand than on the leading strand (26). The most common substrates for the MMR system are small DNA insertion/deletion loops and single DNA base-base mispairs (27–29). The MMR system also corrects DNA mispairs containing 8-oxoguanine and other oxidatively damaged bases (17,30–33). Furthermore, the MMR system removes 1-nucleotide Okazaki fragment flaps (34) and single ribonucleotides, which are incorporated into DNA opposite noncomplementary deoxyribonucleotides (35). MutSα (MSH2-MSH6 heterodimer) and MutLα (MLH1-PMS2 heterodimer in humans and MLH1-PMS1 heterodimer in the yeast S. cerevisiae) are required for the majority of MMR events in eukaryotes (28,36,37). MutSα is the key mismatch recognition factor (28,29,38), and MutLα acts as an endonuclease in MMR (39,40). In addition to MutSα and MutLα, MutSβ (MSH2-MSH3 heterodimer) (29,41–45), Exonuclease 1 (EXO1) (45–48), proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (49–53), replication factor C (RFC) (53), replication protein A (RPA) (52,54,55), DNA polymerase δ (Pol δ) (44,51,56–58), MutLγ (MLH1-MLH3 heterodimer) (59–61), the 3′→5′ exonuclease activity of Pol δ (62), HMGB1 (44,63,64), DNA ligase I (44), and RNAse H2 (65,66) have also been implicated in eukaryotic MMR. Furthermore, PARP1 (67), CAF-1-dependent chromatin assembly (68,69), and SETD2-dependent histone H3 trimethylation on K36 (16,70) have been suggested to regulate MMR. Genetic inactivation of MMR strongly predisposes humans and mice to several types of cancer (43,71–82).

A key feature of MMR is its strand specificity that ensures that a mismatch is corrected on the daughter strand, but not the parental strand. Without strand specificity MMR would be a mutagenic process because it would often result in the removal of a mismatch on the parental strand, converting the replication error into a mutation. MMR is directed to the daughter strands by strand discrimination signals. Strong evidence indicates that strand breaks involved in the leading- and lagging-strand synthesis are the strand discrimination signals for eukaryotic MMR. First, eukaryotic MMR in nuclear extracts, whole-cell extracts, and reconstituted systems occurs on the discontinuous strands, but not the continuous strands (39,40,44,45,48,52,53,57,58,83–86). Second, strand breaks produced by RNAse H2 serve as strand discrimination signals for a small but significant subset of MMR events on the leading strand in the yeast S. cerevisiae (65,66). Here we review how the endonuclease activity of MutL homologs is involved in creating strand breaks during MMR, and how these strand breaks are directed to the daughter strand via interactions with other components of the MMR machinery.

2. Endonuclease activity of MutLα

MutLα is essential for MMR and many other functions of the MMR system (36,37,73,76,77,87–90). During MMR, the major mismatch recognition factor MutSα, the replicative clamp PCNA, the clamp loader RFC, and ATP-Mg2+ activate MutLα endonuclease to incise the discontinuous daughter strand near the mismatch (39,40,58). The second mismatch recognition factor MutSβ can substitute for MutSα in the activation of the endonuclease provided that the mismatch is a small insertion/deletion loop (91). The function of RFC in the endonuclease activation is to load PCNA at a strand discontinuity (92). The incision of the discontinuous daughter strand by MutLα initiates downstream reactions that are necessary to remove the mismatch (39,40,58).

MutLα is also able to act as an ATP-Mn2+-dependent endonuclease in defined reactions that are not involved in MMR (39,40). In these reactions, MutLα alone nicks DNA. RFC and PCNA strongly stimulate the ATP-Mn2+-dependent endonuclease activity of MutLα. The ATP-Mn2+-dependent endonuclease activity of MutLα is maximal in the presence of 1 mM Mn2+, but is not detectable at physiological Mn2+ concentration (35 μM (93)). The latter observation suggests that the ATP-Mn2+-dependent endonuclease activity of MutLα is silent in vivo and does not contribute to eukaryotic MMR (39). In agreement with this idea, Mn2+ is not required for the endonucleolytic function of MutLα in reconstituted MMR reactions (39,40,53,57,58).

The C-terminal part of the PMS2 subunit of hMutLα endonuclease hosts a metal-binding site that includes the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif at position 699–710 (39,94,95). A hMutLα variant carrying the PMS2 D699N substitution (hMutLα-D699N) and another one carrying the PMS2 E705K substitution (hMutLα-E705K) are unable to act as endonucleases in MMR in nuclear extracts and reconstituted systems (39,58). The hMutLα-D699N and hMutLα-E705K mutant proteins also lack the ATP-Mn2+-dependent endonuclease and metal-binding activities. Consistent with these biochemical findings, PMS2-E705K expression in PMS2-deficient cells does not rescue their defect in MMR and the MMR system-dependent apoptotic response to an SN1-type methylating drug (89,96). Further biochemical examination of the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif has suggested that the PMS2 H701 is required for the endonucleolytic function of MutLα in MMR, but the PMS2 E710 is not (97). If the PMS2 E710 is indeed not needed for the action of MutLα endonuclease in MMR, its conservation suggests that it may be involved in another as yet undefined function of MutLα..

The Pms1 subunit of yMutLα and the homologous PMS2 subunit of mMutLα also contain the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif (39). The yPMS1 E707 and mPMS2 E702 are located at the same position within the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif as the hPMS2 E705. Not only does the yPMS1 E707K substitution disrupt the endonuclease activity of yMutLα (40), it also completely inactivates MMR and strongly compromises the MMR system-dependent suppression of homeologous recombination (40,89,96). In agreement with these findings, the mouse Pms2E702K/E702K mutation causes genetic instability, MMR deficiency, and strong predisposition to cancer (79). Importantly, the phenotypes of the mouse Pms2E702K/E702K mutation are the same or nearly the same as those of the Pms2−/−. Collectively, the studies in the human, yeast, and mouse systems have provided strong evidence that the endonuclease activity of MutLα is required for multiple functions of the MMR system: MMR, cancer suppression, prevention of homeologous recombination, and initiation of the apoptotic response to specific DNA lesions.

The inactivation of the metal-binding and endonuclease activities of hMutLα by the PMS2 D699N and E705K substitutions led to the suggestion that the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif is part of the endonuclease active site (39,40). The structural studies of B. subtilis MutL (98) and yeast MutLα (99) have confirmed this idea (94,95). In the structural model of the C-terminal domain of B. subtilis MutL, the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif and three other conserved motifs (ACR, CP/NHGRP, and FXR (97)) form an endonuclease active site (98). Though this active site differs from active sites of nucleases from other families, it has features that characterize many endonuclease active sites: a highly conserved aspartate residue and the ability to bind two divalent metal ions (100). Modeling of DNA onto the structural model of the B. subtilis MutL domain places the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif and a phosphodiester bond in the DNA within a distance from each other that allows the carboxylate side chain of the aspartate residue in the first position of the motif to activate catalysis of an endonucleolytic reaction (98). yPMS1 amino acid residues located within the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E, ACR, and CP/NHGRP motifs and the yMLH1 C769 constitute the yMutLα endonuclease active site (99). The yMutLα endonuclease active site contains two Zn2+ ions (99). Two Zn2+ ions have also been detected in the endonuclease active site of B. subtilis MutL (98). The first glutamate residue of the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif in both yMutLα and B. subtilis MutL participates in coordination of the two Zn2+ ions. The Zn2+ ions have been proposed to be important for regulation of the endonuclease activities of these proteins (97–99). Despite the significant progress that has already been achieved, more research is needed to elucidate how MutLα and its homologs accomplish and regulate the endonucleolytic reaction.

The N-terminal parts of MutLα endonuclease subunits carry conserved ATPase domains that are also present in bacterial MutLs and other members of the GHKL superfamily of proteins (101–105). Accordingly, each subunit of MutLα binds and hydrolyzes ATP. ATP binding and hydrolysis by MutLα subunits drive large conformational changes of the protein (106,107). As described below, the effects of ATP binding and hydrolysis by each MutLα subunit on MMR have been investigated in detail (106,108–110). The yMLH1 N35 and yPMS1 N65 are required for ATP binding by the respective subunits (103,104,106,108). The catalytic residue for ATP hydrolysis by yMLH1 is the E31 and equivalent residue in yPMS1 is the E61 (103,104,106,108). The disruption of ATP-binding activity of either yMLH1 with the N35A or yPMS1 with the N65A completely inactivates yeast MMR (108). On the other hand, the elimination of the ATP hydrolytic activity of yMLH1 with the E31A or yPMS1 with the E61A results only in a weak defect in yeast MMR.

Amino acid residues essential for ATP binding by hMLH1 are the N38 and D63, and the functionally similar residues in hPMS2 are the N45 and D70 (103,104,109,110). Blocking ATP binding with the hMLH1 N38A, hPMS2 N45A, or hPMS2 D70N substitution abolishes human MMR (109). The catalytic residues for hMLH1 and hPMS2 ATPases are the E34 and E41, respectively (103,104,109,110). The hMLH1 E34A and hPMS2 E41A substitutions each cause only a weak defect in human MMR. However, the hMLH1-E34A hPMS2-E41A double substitution obliterates human MMR (109) by inactivating the ability of MutLα to incise the discontinuous strand in the presence of MutSα, PCNA, RFC, ATP-Mg2+, and a mismatch (39). Collectively, these findings support the following conclusions. First, the endonucleolytic function of MutLα in MMR is abolished when either of its subunits loses the ability to bind ATP or both subunits are unable to hydrolyze ATP. Second, the endonucleolytic function of MutLα in MMR is only weakly compromised when only one of its subunits is defective in ATP hydrolysis.

MutLα binds both single-stranded and double-stranded DNAs (105,111,112). A structure-based candidate approach has revealed that the yMLH1-R273E-R274E double substitution, which weakens the DNA-binding activity of yMutLα, completely inactivates yeast MMR (112). The result supports the view that the ability of MutLα to bind DNA is required for the endonucleolytic function of this protein in MMR.

3. MutLα and human nick-directed MMR

3′- and 5′-nick directed modes of MMR have been demonstrated in extracts of human, Drosophila, mouse, and Xenopus cells and reconstituted systems (44,45,57,58,83,84,113–115). (3′-nick directed MMR occurs on a 3′ heteroduplex DNA, which contains a nick 3′ to a mismatch, and 5′-nick directed MMR takes place on a 5′ heteroduplex DNA, which carries a nick 5′ to a mismatch.) Mammalian MutLα, MutSα, MutSβ, EXO1, PCNA, RFC, and RPA are involved in both 3′- and 5′-nick directed MMR in extracts and reconstituted systems (28,29,37,39,41,44,46,48,52–54,57,58,91,116,117). The establishment and analysis of the reconstituted systems has been instrumental for defining the functions of these proteins in nick-directed MMR (39,44,52,53,57,58,91). The reconstituted systems rely on the action of MutSα or MutSβ for initiation and progression of the reaction. MutSα is the primary mismatch recognition factor required for repair of base-base mismatches and 1-nt insertion/deletion loops (28). In addition, MutSα is needed for repair of a large fraction of 2–12-nt insertion/deletion loops (29,44). Repair of the remainder of 2–12-nt insertion/deletion loops depends on MutSβ (29). The simplest reconstituted system includes MutSα, MutLα, EXO1, and RPA, and performs a 5′-nick directed mismatch excision (52). MutLα endonuclease activity is silent during the reconstituted 5 ′-nick directed mismatch excision due to the absence of loaded PCNA. The reconstituted 5′-nick directed mismatch excision is initiated by the recognition of a base-base mispair by MutSα. Upon mismatch recognition, MutSα activates EXO1 to degrade a mismatch-containing segment of the discontinuous strand in a 5′→3′ excision reaction that initiates from a pre-existing nick and is stimulated by RPA (52). Once the mismatch is excised, MutSα and RPA suppress EXO1 activity protecting the DNA from unnecessary degradation (52). Though MutLα does not influence the excision on heteroduplex DNA, the protein significantly enhances MutSα-dependent suppression of the exonucleolytic degradation on homoduplex DNA. The effect is probably a result of the inhibition of EXO1 activity by MutLα (118) and the MutSα-MutLα complex (119,120).

The addition of PCNA and its loader RFC to the four-protein system produces a six-protein system that is proficient in both 5′- and 3′-nick directed mismatch excision (53). Both modes of excision occurring in this system depend on MutSα and the 5′→3′-directed exonuclease activity of EXO1 (53,121). Furthermore, 3′-nick directed mismatch excision requires the endonuclease activity of MutLα, but 5′-nick directed mismatch excision does not. During 3′-nick directed mismatch excision, MutLα endonuclease activated by MutSα and loaded PCNA incises the discontinuous strand of 3′ heteroduplex DNA producing strand breaks that are often 5′ to the mismatch (39). A 5′ strand break produced by MutLα is used by EXO1 as the starting point of 5′→3′ excision that removes a part of the discontinuous strand containing the mismatch (Fig. 1). The effect of RFC on the 3′ excision is twofold. First, it loads PCNA onto the 3′ heteroduplex DNA. Second, RFC inhibits EXO1-mediated 5′→3′ excision that initiates from the pre-existing 3′ nick and occurs in a direction opposite to the location of the mismatch. RFC activity responsible for this effect has been mapped to the N-terminal domain of the largest subunit of the protein. Supplementation of the six-protein system with Pol δ yields a system that is competent in both 5′- and 3′-nick directed MMR (57). The reconstituted 3′-nick directed MMR depends on all seven proteins, but the reconstituted 5′-nick directed MMR does not require the MutLα endonuclease activity.

Figure 1. Models of EXO1-dependent and EXO1-independent MMR in human cells.

The models are adapted from Kadyrov et a 2006, 2007 (39,58) and are based on the results of studies of human MMR in the reconstituted systems (39,52,53,57,58). Pol δ HE, Pol δ holoenzyme. See text (Section 3) for details.

Contrary to the reconstituted 5′-nick directed MMR (57), 5′-nick directed MMR in some but not all nuclear extracts involves MutLα (37,122,123). We hypothesize that 5′-nick directed MMR in vivo requires the endonuclease activity of MutLα (Fig. 1). This hypothesis is supported by the observations that MutLα deficiency causes the same mutator phenotype and cancer predisposition as MutSα deficiency (26,50,90,124). It is probable that some protein factors like DNA ligases that are absent in the reconstituted system (57) do not allow 5′-nick directed MMR to occur in a MutLα-independent manner in vivo.

Loss of EXO1 in yeast and mouse cells causes only weak or modest defects in MMR (47,62,125). Moreover, inactivation of EXO1 has not been linked to carcinogenesis in humans, and Exo1−/− mice display a moderate predisposition to cancer (125). These observations have suggested that MMR remains functional in the absence of EXO1. As described above, MutLα endonuclease activity plays a central role in MMR that involves EXO1 (Fig. 1). In addition, MutLα is essential for EXO1-independent MMR (51,126,127). Analysis of whole-cell extracts and reconstituted systems has identified a mechanism for EXO1-independent MMR that does not involve mismatch excision (58). The mechanism requires the activities of MutSα, MutLα, PCNA, RFC, and Pol δ, and is directed by a strand discontinuity. In this mechanism, the activated MutLα endonuclease cleaves the discontinuous strand of a heteroduplex DNA producing strand breaks near the mismatch (Fig. 1). A new 3′ end created by the MutLα cleavage 5′ to the mismatch primes DNA synthesis that displaces a part of the discontinuous strand containing the mismatch. The strand-displacement synthesis is carried out by Pol δ holoenzyme and strongly stimulated by RPA. Thus, the combined action of six human proteins corrects mismatches in an excision-free process. Time-course analysis of the EXO1-independent repair has indicated that its rate is significantly slower than that of the repair involving EXO1 (58). This suggests that in the presence of EXO1, MMR probably occurs via the EXO1-dependent mechanism (Fig. 1). The involvement of the strand-displacement mechanism in yeast EXO1-independent MMR is supported by studies that have demonstrated that ablation of the Pol32 subunit causes defects in both the strand-displacement activity of Pol δ and MMR (51,128,129). A recent report has described that an MSH6 mutant defective in the interaction with PCNA does not support EXO1-independent MMR in yeast cells (130). It will be interesting to determine whether this mutation affects the reconstituted strand displacement-based MMR. The strand-displacement mechanism is probably not the only option for EXO1-independent MMR (62). Given the importance of EXO1-independent MMR for the suppression of carcinogenesis, it is important to continue to investigate its key players and mechanisms.

4. Models for the activation of MutLα endonuclease in MMR

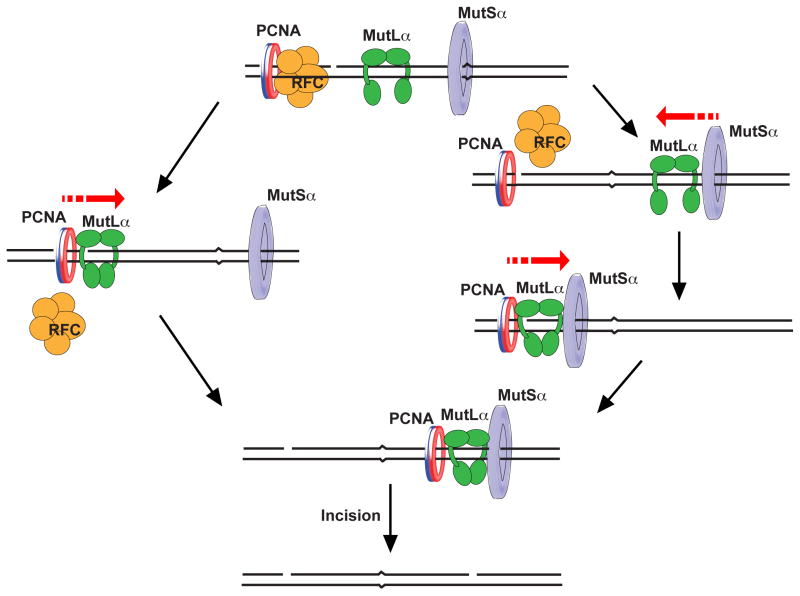

Despite the importance of the endonuclease activity of MutLα for MMR (39,40,79), the mechanism of its activation in this process remains undefined. Two models that are not mutually exclusive outline possible mechanisms of the MutSα-, PCNA-, RFC-, ATP-, and mismatch-dependent activation of MutLα endonuclease in MMR (Fig. 2). The models are based on the observations that 1) during MMR, MutSα, PCNA, RFC, and ATP-Mg2+ activate MutLα to incise the discontinuous strand (39,40,92), 2) the ATP-Mn2+-dependent endonuclease activity of MutLα incises both strands of nicked heteroduplex DNA with the same efficiency (40), 3) PCNA and RFC are sufficient to direct the ATP-Mn2+-dependent endonuclease activity of MutLα to cut the discontinuous strand (40), 4) MutLα activated by MutSα, PCNA, and RFC on heteroduplex DNA lacking a pre-existing strand break weakly incises both strands without displaying a strand bias (92), 5) MutLα and MutSα form a complex on heteroduplex DNA in a mismatch-dependent manner (119,120), 6) RFC function in the activation of MutLα endonuclease is to load PCNA (92), 7) after loading PCNA, RFC dissociates from DNA (131), and 8) when loaded at a strand discontinuity by RFC, the PCNA trimer is oriented such that its face containing the hydrophobic pocket, required for the interactions with numerous DNA replication and repair proteins (132–134), is directed towards the strand discontinuity (135).

Figure 2. Models for the activation of MutLα endonuclease in MutSα-dependent MMR.

See text (Section 4) for details.

In one of the models (Fig. 2, left panel), assembly of the complex between MutLα and loaded PCNA at a strand break is an early event in the activation of the endonuclease. The complex formation depends on the presence of the hydrophobic pocket in PCNA. During, immediately before, or after the complex formation, the MutLα utilizes the strand break to recognize which of the strands is discontinuous. A transient or permanent kink at the strand break (136) and/or the loaded PCNA might facilitate the recognition of the discontinuous strand by the MutLα. The strand recognition triggers ATP-dependent adoption of activated conformation by the MutLα. In the activated conformation, the MutLα is ready to incise the discontinuous strand, but not the continuous strand. Once the MutLα-PCNA complex is formed it starts sliding along DNA. When the sliding MutLα-PCNA complex contacts a mismatch-activated MutSα (137,138), the mismatch recognition factor activates the MutLα to incise the discontinuous strand.

The other model envisions that the formation of the complex between mismatch-activated MutSα and MutLα on heteroduplex DNA occurs before loaded PCNA is engaged in the activation of the nuclease (Fig. 2, right panel). After the MutSα-MutLα complex is formed, it slides on the DNA and contacts loaded PCNA. This results in assembly of MutSα-MutLα-PCNA complex. When the three-protein complex sliding along the DNA reaches a strand-break, the MutLα recognizes the discontinuous strand and assumes the activated conformation. The complex resumes its movement on the DNA and then the activated MutLα incises the discontinuous strand. Though the two models are consistent with the existing data, it will be important to determine the actual mechanism of MutLα activation in both MutSα- and MutSβ-dependent MMR. The mechanism of MutLα endonuclease activation in MutSβ-dependent MMR is probably different from that in MutSα-dependent MMR (91).

5. Endonuclease activity of prokaryotic and eukaryotic MutLα homologs

MMR in bacteria depends on homodimeric MutL proteins that are prokaryotic homologs of MutLα (98,139–142). Many MutLs contain the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif (39,40,97) or a slightly modified sequence (142,143). Up to date, endonuclease activity has been demonstrated for the following DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif-containing MutLs: A. aeolicus MutL (141,143–145), T. thermophilus MutL (141), B. subtilis MutL (98), P. aeruginosa MutL (142,146), and N. gonorrhoeae MutL (147,148). These enzymes have Mn2+-dependent activities that nick supercoiled DNA. ngMutL and paMutL endonucleases are also activated by Mg2+(142,147). Endonuclease activities of these proteins are stimulated or inhibited by ATP (98,141,142,144,147,149). The involvement of endonuclease activities of ttMutL, bsMutL, and paMutL in bacterial MMR has been investigated (98,141,142). Replacing the aspartate residue of the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif with an asparagine residue in ttMutL and bsMutL eliminates their Mn2+-dependent endonuclease activities and the function of these proteins in MMR (98,141). A different result has been obtained during a similar biochemical and genetic examination of paMutL endonuclease (142). The study has revealed that the D-to-N substitution in the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif of paMutL does not affect the endonuclease activity of this MutLα homolog, but abolishes MMR in P. aeruginosa. Thus, the studies of ttMutL and bsMutL (98,141) support the conclusion that MutL proteins containing the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif act as endonucleases in MMR, but the analysis of paMutL (142) contradicts this conclusion. Given that the endonuclease activity of the mutant paMutL was measured in the reactions that are not provoked by a mismatch, it is possible that elimination of paMutL endonuclease activity by the D-N substitution can only be observed in P. aeruginosa mismatch-provoked reactions. It will be important to address this possibility in future studies.

The effects of protein factors implicated in MMR on the endonuclease activity of one MutL protein, ttMutL, have been determined (149). The endonuclease activity of ttMutL that nicks supercoiled DNA is strongly stimulated by ttMutS, a mismatch, ATP, and Mn2+ (149). Replacing Mn2+ with Mg2+ abolishes the endonuclease activation. The presence of the clamp and a clamp loader variant does not influence the Mn2+-dependent endonuclease activity of ttMutL even when the heteroduplex DNA carries a strand break. These findings have indicated the ttMutS- and mismatch-dependent activation of ttMutL does not require Mg2+, the clamp, the clamp loader, and a pre-existing strand break. Therefore, the mechanism of MMR in T. thermophilus may be quite different from that in human cells.

MutLγ is a eukaryotic MutLα homolog (59,150) that has the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif in its MLH3 subunit (39). yMutLγ has an ATP-independent nicking activity that is activated by Mg2+, Mn2+, or Co2+ ions (151,152). yMutLγ endonuclease plays a role in yeast MMR, acting in the MutSβ-dependent pathway (59,60,151,152). The D-to-N substitution in the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif eliminates the impact of yMutLγ on MMR (60). Strikingly, the endonuclease activity of yMutLγ is not affected by yRFC and yPCNA (151,152), but stimulated by yMutSβ (152). These results suggest that MutLγ endonuclease promotes MMR through a mechanism that differs from the one involving the MutLα endonuclease.

In summary, recent biochemical, genetic, and structural studies have provided novel insights into the functions of MutLα and some of its homologs. Future studies will undoubtedly lead to new discoveries that will advance our understanding of human MutLα endonuclease and its contribution to MMR, cancer suppression, and other functions of the MMR system.

Acknowledgments

We thank Farid F. Kadyrov for critical reading of the manuscript. We apologize to authors whose work was not cited in this review due to the space limitations. This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01GM095758.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Modrich P, Lahue R. Mismatch repair in replication fidelity, genetic recombination, and cancer biology. Ann Rev Biochem. 1996;65:101–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.000533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolodner RD, Marsischky GT. Eukaryotic DNA mismatch repair. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:89–96. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)80013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harfe BD, Jinks-Robertson S. DNA Mismatch Repair and Genetic Instability. Annu Rev Genet. 2000;34:359–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Surtees JA, Argueso JL, Alani E. Mismatch repair proteins: key regulators of genetic recombination. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2004;107:146–159. doi: 10.1159/000080593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edelmann L, Edelmann W. Loss of DNA mismatch repair function and cancer predisposition in the mouse: animal models for human hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2004;129C:91–99. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kunkel TA, Erie DA. DNA Mismatch Repair. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:681–710. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iyer RR, Pluciennik A, Burdett V, Modrich PL. DNA mismatch repair: functions and mechanisms. Chem Rev. 2006;106:302–323. doi: 10.1021/cr0404794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Modrich P. Mechanisms in eukaryotic mismatch repair. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30305–30309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600022200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang W. Human MutLalpha: the jack of all trades in MMR is also an endonuclease. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:135–139. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsieh P, Yamane K. DNA mismatch repair: molecular mechanism, cancer, and ageing. Mech Ageing Dev. 2008;129:391–407. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li GM. Mechanisms and functions of DNA mismatch repair. Cell Res. 2008;18:85–98. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boiteux S, Jinks-Robertson S. DNA Repair Mechanisms and the Bypass of DNA Damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2013;193:1025–1064. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.145219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pena-Diaz J, Jiricny J. Mammalian mismatch repair: error-free or error-prone? Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasmussen LJ, Heinen CD, Royer-Pokora B, Drost M, Tavtigian S, Hofstra RM, de Wind N. Pathological assessment of mismatch repair gene variants in Lynch syndrome: past, present, and future. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:1617–1625. doi: 10.1002/humu.22168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin-Lopez JV, Fishel R. The mechanism of mismatch repair and the functional analysis of mismatch repair defects in Lynch syndrome. Fam Cancer. 2013;12:159–168. doi: 10.1007/s10689-013-9635-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li GM. New insights and challenges in mismatch repair: getting over the chromatin hurdle. DNA Repair (Amst) 2014;19:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crouse GF. Non-canonical actions of MMR. DNA Repair (Amst) 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.11.020. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zanotti KJ, Gearhart PJ. Antibody diversification caused by abortive MMR and promiscuous DNA polymerases. DNA Repair (Amst) 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.11.011. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williamson MS, Game JC, Fogel S. Meiotic gene conversion mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. I. Isolation and characterization of pms1–1 and pms1–2. Genetics. 1985;110:609–646. doi: 10.1093/genetics/110.4.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reenan RA, Kolodner RD. Characterization of insertion mutations in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae MSH1 and MSH2 genes: evidence for separate mitochondrial and nuclear functions. Genetics. 1992;132:975–985. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.4.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison A, Johnson AL, Johnston LH, Sugino A. Pathway correcting DNA replication errors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1993;12:1467–1473. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05790.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrison A, Sugino A. The 3′-->5′ exonucleases of both DNA polymerases delta and epsilon participate in correcting errors of DNA replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;242:289–296. doi: 10.1007/BF00280418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tran HT, Keen JD, Kricker M, Resnick MA, Gordenin DA. Hypermutability of homonucleotide runs in mismatch repair and DNA polymerase proofreading yeast mutants. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2859–2865. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greene CN, Jinks-Robertson S. Spontaneous frameshift mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: accumulation during DNA replication and removal by proofreading and mismatch repair activities. Genetics. 2001;159:65–75. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tlam KC, Lebbink J. Functions of MMR in regulating genetic recombination. DNA Repair (Amst) 2016 this issue. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pavlov YI, Mian IM, Kunkel TA. Evidence for preferential mismatch repair of lagging strand DNA replication errors in yeast. Curr Biol. 2003;13:744–748. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Su S-S, Modrich P. Escherichia coli mutS-encoded protein binds to mismatched DNA base pairs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:5057–5061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drummond JT, Li GM, Longley MJ, Modrich P. Isolation of an hMSH2·p160 heterodimer that restores mismatch repair to tumor cells. Science. 1995;268:1909–1912. doi: 10.1126/science.7604264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Genschel J, Littman SJ, Drummond JT, Modrich P. Isolation of hMutSβ from human cells and comparison of the mismatch repair specificities of hMutSβ and hMutSα. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19895–19901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Earley MC, Crouse GF. The role of mismatch repair in the prevention of base pair mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15487–15491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ni TT, Marsischky GT, Kolodner RD. MSH2 and MSH6 are required for removal of adenine misincorporated opposite 8-oxo-guanine in S. cerevisiae. Mol Cell. 1999;4:439–444. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colussi C, Parlanti E, Degan P, Aquilina G, Barnes D, Macpherson P, Karran P, Crescenzi M, Dogliotti E, Bignami M. The mammalian mismatch repair pathway removes DNA 8-oxodGMP incorporated from the oxidized dNTP pool. Curr Biol. 2002;12:912–918. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00863-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russo MT, Blasi MF, Chiera F, Fortini P, Degan P, Macpherson P, Furuichi M, Nakabeppu Y, Karran P, Aquilina G, Bignami M. The oxidized deoxynucleoside triphosphate pool is a significant contributor to genetic instability in mismatch repair-deficient cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:465–474. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.1.465-474.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kadyrova LY, Dahal BK, Kadyrov FA. Evidence that the DNA Mismatch Repair System Removes 1-nt Okazaki Fragment Flaps. J Biol Chem. 2015 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.660357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen Y, Koh KD, Weiss B, Storici F. Mispaired rNMPs in DNA are mutagenic and are targets of mismatch repair and RNases H. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:98–104. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strand M, Prolla TA, Liskay RM, Petes TD. Destabilization of tracts of simple repetitive DNA in yeast by mutations affecting DNA mismatch repair. Nature. 1993;365:274–276. doi: 10.1038/365274a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li G-M, Modrich P. Restoration of mismatch repair to nuclear extracts of H6 colorectal tumor cells by a heterodimer of human MutL homologs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:1950–1954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hingorani MM. Mismatch binding, ADP-ATP exchange and intramolecular signaling during MMR. DNA Repair (Amst) 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.11.017. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kadyrov FA, Dzantiev L, Constantin N, Modrich P. Endonucleolytic function of MutLalpha in human mismatch repair. Cell. 2006;126:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kadyrov FA, Holmes SF, Arana ME, Lukianova OA, O′Donnell M, Kunkel TA, Modrich P. Saccharomyces cerevisiae MutLalpha is a mismatch repair endonuclease. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37181–37190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707617200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palombo F, Iaccarino I, Nakajima E, Ikejima M, Shimada T, Jiricny J. hMutSβ, a heterodimer of hMSH2 and hMSH3, binds to insertion/deletion loops in DNA. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1181–1184. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70685-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marsischky GT, Filosi N, Kane MF, Kolodner R. Redundancy of Saccharomyces cerevisiae MSH3 and MSH6 in MSH2-dependent mismatch repair. Genes Dev. 1996;10:407–420. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Wind N, Dekker M, Claij N, Jansen L, van Klink Y, Radman M, Riggins G, van der Valk M, van′t Wout K, te Riele H. HNPCC-like cancer predisposition in mice through simultaneous loss of Msh3 and Msh6 mismatch-repair protein functions. Nat Genet. 1999;23:359–362. doi: 10.1038/15544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Y, Yuan F, Presnell SR, Tian K, Gao Y, Tomkinson AE, Gu L, Li GM. Reconstitution of 5′-directed human mismatch repair in a purified system. Cell. 2005;122:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bowen N, Smith CE, Srivatsan A, Willcox S, Griffith JD, Kolodner RD. Reconstitution of long and short patch mismatch repair reactions using Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:18472–18477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318971110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Szankasi P, Smith GR. A role for exonuclease I from S. pombe in mutation avoidance and mismatch correction. Science. 1995;267:1166–1169. doi: 10.1126/science.7855597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tishkoff DX, Boerger AL, Bertrand P, Filosi N, Gaida GM, Kane MF, Kolodner RD. Identification and characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae EXO1, a gene encoding an exonuclease that interacts with MSH2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:7487–7492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Genschel J, Bazemore LR, Modrich P. Human exonuclease I is required for 5′ and 3′ mismatch repair. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13302–13311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Umar A, Buermeyer AB, Simon JA, Thomas DC, Clark AB, Liskay RM, Kunkel TA. Requirement for PCNA in DNA mismatch repair at a step preceding DNA resynthesis. Cell. 1996;87:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johnson RE, Kovvali GK, Guzder SN, Amin NS, Holm C, Habraken Y, Sung P, Prakash L, Prakash S. Evidence for involvement of yeast proliferating cell nuclear antigen in DNA mismatch repair. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27987–27990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.27987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amin NS, Nguyen MN, Oh S, Kolodner RD. exo1-Dependent mutator mutations: model system for studying functional interactions in mismatch repair. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5142–5155. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.15.5142-5155.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Genschel J, Modrich P. Mechanism of 5′-directed excision in human mismatch repair. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1077–1086. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00428-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dzantiev L, Constantin N, Genschel J, Iyer RR, Burgers PM, Modrich P. A defined human system that supports bidirectional mismatch-provoked excision. Mol Cell. 2004;15:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin YL, Shivji MK, Chen C, Kolodner R, Wood RD, Dutta A. The evolutionarily conserved zinc finger motif in the largest subunit of human replication protein A is required for DNA replication and mismatch repair but not for nucleotide excision repair. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1453–1461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramilo C, Gu L, Guo S, Zhang X, Patrick SM, Turchi JJ, Li GM. Partial reconstitution of human DNA mismatch repair in vitro: characterization of the role of human replication protein A. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2037–2046. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2037-2046.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Longley MJ, Pierce AJ, Modrich P. DNA polymerase delta is required for human mismatch repair in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10917–10921. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Constantin N, Dzantiev L, Kadyrov FA, Modrich P. Human mismatch repair: Reconstitution of a nick-directed bidirectional reaction. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39752–39761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509701200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kadyrov FA, Genschel J, Fang Y, Penland E, Edelmann W, Modrich P. A possible mechanism for exonuclease 1-independent eukaryotic mismatch repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8495–8500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903654106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Flores-Rozas H, Kolodner RD. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae MLH3 gene functions in MSH3-dependent suppression of frameshift mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:12404–12409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nishant KT, Plys AJ, Alani E. A mutation in the putative MLH3 endonuclease domain confers a defect in both mismatch repair and meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2008;179:747–755. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.086645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cannavo E, Marra G, Sabates-Bellver J, Menigatti M, Lipkin SM, Fischer F, Cejka P, Jiricny J. Expression of the MutL homologue hMLH3 in human cells and its role in DNA mismatch repair. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10759–10766. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tran HT, Gordenin DA, Resnick MA. The 3′-->5′ exonucleases of DNA polymerases delta and epsilon and the 5′-->3′ exonuclease Exo1 have major roles in postreplication mutation avoidance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2000–2007. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yuan F, Gu L, Guo S, Wang C, Li GM. Evidence for involvement of HMGB1 protein in human DNA mismatch repair. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20935–20940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401931200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Genschel J, Modrich P. Functions of MutLalpha, replication protein A (RPA), and HMGB1 in 5′-directed mismatch repair. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21536–21544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.021287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ghodgaonkar MM, Lazzaro F, Olivera-Pimentel M, Artola-Boran M, Cejka P, Reijns MA, Jackson AP, Plevani P, Muzi-Falconi M, Jiricny J. Ribonucleotides misincorporated into DNA act as strand-discrimination signals in eukaryotic mismatch repair. Mol Cell. 2013;50:323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lujan SA, Williams JS, Clausen AR, Clark AB, Kunkel TA. Ribonucleotides are signals for mismatch repair of leading-strand replication errors. Mol Cell. 2013;50:437–443. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu Y, Kadyrov FA, Modrich P. PARP-1 enhances the mismatch-dependence of 5′-directed excision in human mismatch repair in vitro. DNA Repair. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kadyrova LY, Rodriges Blanko E, Kadyrov FA. CAF-I-dependent control of degradation of the discontinuous strands during mismatch repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:2753–2758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015914108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schopf B, Bregenhorn S, Quivy JP, Kadyrov FA, Almouzni G, Jiricny J. Interplay between mismatch repair and chromatin assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:1895–1900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106696109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li F, Mao G, Tong D, Huang J, Gu L, Yang W, Li GM. The histone mark H3K36me3 regulates human DNA mismatch repair through its interaction with MutSalpha. Cell. 2013;153:590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fishel R, Lescoe MK, Rao MR, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Garber J, Kane M, Kolodner R. The human mutator gene homolog MSH2 and its association with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. Cell. 1993;75:1027–1038. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90546-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leach FS, Nicolaides NC, Papadopoulos N, Liu B, Jen J, Parsons R, Peltomäki P, Sistonen P, Aaltonen LA, Nyström-Lahti M, Guan XY, Zhang J, Meltzer PS, Yu JW, Kao FT, Chen DJ, Cerosaletti KM, Fournier REK, Todd S, Lewis T, Leach RJ, Naylor SL, Weissenbach J, Mecklin JP, Järvinen H, Petersen GM, Hamilton SR, Green J, Jass J, Watson P, Lynch HT, Trent JM, de la Chapelle A, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Mutations of a mutS homolog in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Cell. 1993;75:1215–1225. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90330-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Parsons R, Li GM, Longley MJ, Fang WH, Papadopoulos N, Jen J, de la Chapelle A, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Modrich P. Hypermutability and mismatch repair deficiency in RER+ tumor cells. Cell. 1993;75:1227–1236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90331-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Papadopoulos N, Nicolaides NC, Wei YF, Ruben SM, Carter KC, Rosen CA, Haseltine WA, Fleischmann RD, Fraser CM, Adams MD, Venter JC, Hamilton SR, Peterson GM, Watson P, Lynch HT, Peltomäki P, Mecklin JP, de la Chapelle A, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Mutation of a mutL homolog in hereditary colon cancer. Science. 1994;263:1625–1629. doi: 10.1126/science.8128251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.de Wind N, Dekker M, Berns A, Radman M, te Riele H. Inactivation of the mouse Msh2 gene results in mismatch repair deficiency, methylation tolerance, hyperrecombination, and predisposition to cancer. Cell. 1995;82:321–330. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90319-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Edelmann W, Cohen PE, Kane M, Lau K, Morrow B, Bennett S, Umar A, Kunkel T, Cattoretti G, Chaganti R, Pollard JW, Kolodner RD, Kucherlapati R. Meiotic pachytene arrest in MLH1-deficient mice. Cell. 1996;85:1125–1134. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Baker SM, Bronner CE, Zhang L, Plug A, Robatzek M, Warren G, Elliott EA, Yu J, Ashley T, Arnheim N, Flavell RA, Liskay RM. Male mice defective in the DNA mismatch repair gene PMS2 exhibit abnormal chromosome synapsis in meiosis. Cell. 1995;82:309–319. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90318-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nakagawa H, Lockman JC, Frankel WL, Hampel H, Steenblock K, Burgart LJ, Thibodeau SN, de la Chapelle A. Mismatch repair gene PMS2: disease-causing germline mutations are frequent in patients whose tumors stain negative for PMS2 protein, but paralogous genes obscure mutation detection and interpretation. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4721–4727. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van Oers JM, Roa S, Werling U, Liu Y, Genschel J, Hou H, Jr, Sellers RS, Modrich P, Scharff MD, Edelmann W. PMS2 endonuclease activity has distinct biological functions and is essential for genome maintenance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13384–13389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008589107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Heinen CD. MMR defects and Lynch syndrome: the role of the basic scientist in the battle against cancer. DNA Repair (Amst) 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.11.025. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee K, Tosti E, Edelmann W. Mouse models of MMR in cancer research. DNA Repair (Amst) 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.11.015. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sijmons RH, Hofstra RMW. Clinical aspects of hereditary MMR gene mutations. DNA Repair (Amst) 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.11.018. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Holmes J, Clark S, Modrich P. Strand-specific mismatch correction in nuclear extracts of human and Drosophila melanogaster cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:5837–5841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Thomas DC, Roberts JD, Kunkel TA. Heteroduplex repair in extracts of human HeLa cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3744–3751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Varlet I, Canard B, Brooks P, Cerovic G, Radman M. Mismatch repair in Xenopus egg extracts: DNA strand breaks act as signals rather than excision points. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:10156–10161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schanz S, Castor D, Fischer F, Jiricny J. Interference of mismatch and base excision repair during the processing of adjacent U/G mispairs may play a key role in somatic hypermutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5593–5598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901726106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Datta A, Adjiri A, New L, Crouse GF, Jinks Robertson S. Mitotic crossovers between diverged sequences are regulated by mismatch repair proteins in Saccaromyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1085–1093. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cejka P, Stojic L, Mojas N, Russell AM, Heinimann K, Cannavo E, di Pietro M, Marra G, Jiricny J. Methylation-induced G(2)/M arrest requires a full complement of the mismatch repair protein hMLH1. EMBO J. 2003;22:2245–2254. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Erdeniz N, Nguyen M, Deschenes SM, Liskay RM. Mutations affecting a putative MutLalpha endonuclease motif impact multiple mismatch repair functions. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:1463–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kadyrova LY, Mertz TM, Zhang Y, Northam MR, Sheng Z, Lobachev KS, Shcherbakova PV, Kadyrov FA. A reversible histone H3 acetylation cooperates with mismatch repair and replicative polymerases in maintaining genome stability. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Iyer RR, Pluciennik A, Genschel J, Tsai MS, Beese LS, Modrich P. MutLalpha and proliferating cell nuclear antigen share binding sites on MutSbeta. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11730–11739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.104125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pluciennik A, Dzantiev L, Iyer RR, Constantin N, Kadyrov FA, Modrich P. PCNA function in the activation and strand direction of MutLalpha endonuclease in mismatch repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2010;107:16066–16071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010662107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ash DE, Schramm VL. Determination of free and bound manganese(II) in hepatocytes from fed and fasted rats. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:9261–9264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Groothuizen FS, Sixma TK. The conserved molecular machinery in MMR structures. DNA Repair (Amst) 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.11.012. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Putnam CD. Evolution of the methyl directed MMR system in Escherichia coli. DNA Repair (Amst) 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.11.016. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Deschenes SM, Tomer G, Nguyen M, Erdeniz N, Juba NC, Sepulveda N, Pisani JE, Liskay RM. The E705K mutation in hPMS2 exerts recessive, not dominant, effects on mismatch repair. Cancer Lett. 2007;249:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kosinski J, Plotz G, Guarne A, Bujnicki JM, Friedhoff P. The PMS2 subunit of human MutLalpha contains a metal ion binding domain of the iron-dependent repressor protein family. J Mol Biol. 2008;382:610–627. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pillon MC, Lorenowicz JJ, Uckelmann M, Klocko AD, Mitchell RR, Chung YS, Modrich P, Walker GC, Simmons LA, Friedhoff P, Guarne A. Structure of the endonuclease domain of MutL: unlicensed to cut. Mol Cell. 2010;39:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gueneau E, Dherin C, Legrand P, Tellier-Lebegue C, Gilquin B, Bonnesoeur P, Londino F, Quemener C, Le Du MH, Marquez JA, Moutiez M, Gondry M, Boiteux S, Charbonnier JB. Structure of the MutLalpha C-terminal domain reveals how Mlh1 contributes to Pms1 endonuclease site. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:461–468. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yang W. An equivalent metal ion in one- and two-metal-ion catalysis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:1228–1231. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mushegian AR, Bassett DE, Jr, Boguski MS, Bork P, Koonin EV. Positionally cloned human disease genes: patterns of evolutionary conservation and functional motifs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:5831–5836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bergerat A, de Massy B, Gadelle D, Varoutas PC, Nicolas A, Forterre P. An atypical topoisomerase II from Archaea with implications for meiotic recombination. Nature. 1997;386:414–417. doi: 10.1038/386414a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ban C, Yang W. Crystal structure and ATPase activity of MutL: implications for DNA repair and mutagenesis. Cell. 1998;95:541–552. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81621-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ban C, Junop M, Yang W. Transformation of MutL by ATP binding and hydrolysis: a switch in DNA mismatch repair. Cell. 1999;97:85–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80717-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Guarne A, Junop MS, Yang W. Structure and function of the N-terminal 40 kDa fragment of human PMS2: a monomeric GHL ATPase. EMBO J. 2001;20:5521–5531. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tran PT, Liskay RM. Functional studies on the candidate ATPase domains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae MutLalpha. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6390–6398. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.17.6390-6398.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sacho EJ, Kadyrov FA, Modrich P, Kunkel TA, Erie DA. Direct visualization of asymmetric adenine-nucleotide-induced conformational changes in MutL alpha. Mol Cell. 2008;29:112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hall MC, Shcherbakova PV, Kunkel TA. Differential ATP binding and intrinsic ATP hydrolysis by amino terminal domains of the yeast Mlh1 and Pms1 proteins. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3673–3679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106120200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Raschle M, Dufner P, Marra G, Jiricny J. Mutations within the hMLH1 and hPMS2 subunits of the human MutLalpha mismatch repair factor affect its ATPase activity, but not its ability to interact with hMutSalpha. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21810–21820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108787200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tomer G, Buermeyer AB, Nguyen MM, Liskay RM. Contribution of human mlh1 and pms2 ATPase activities to DNA mismatch repair. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21801–21809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111342200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hall MC, Wang H, Erie DA, Kunkel TA. High affinity cooperative DNA binding by the yeast Mlh1-Pms1 heterodimer. J Mol Biol. 2001;312:637–647. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hall MC, Shcherbakova PV, Fortune JM, Borchers CH, Dial JM, Tomer KB, Kunkel TA. DNA binding by yeast Mlh1 and Pms1: implications for DNA mismatch repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2025–2034. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Varlet I, Radman M, Brooks P. DNA mismatch repair in Xenopus egg extracts: repair efficiency and DNA repair synthesis for all single base-pair mismatches. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:7883–7887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Repmann S, Olivera-Harris M, Jiricny J. Influence of oxidized purine processing on strand directionality of mismatch repair. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:9986–9999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.629907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Smith CE, Bowen N, Graham WJt, Goellner EM, Srivatsan A, Kolodner RD. Activation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mlh1-Pms1 Endonuclease in a Reconstituted Mismatch Repair System. J Biol Chem. 2015 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.662189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Palombo F, Gallinari P, Iaccarino I, Lettieri T, Hughes M, D′Arrigo A, Truong O, Hsuan JJ, Jiricny J. GTBP, a 160-kilodalton protein essential for mismatch-binding activity in human cells. Science. 1995;268:1912–1914. doi: 10.1126/science.7604265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wei K, Kucherlapati R, Edelmann W. Mouse models for human DNA mismatch-repair gene defects. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:346–353. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nielsen FC, Jager AC, Lutzen A, Bundgaard JR, Rasmussen LJ. Characterization of human exonuclease 1 in complex with mismatch repair proteins, subcellular localization and association with PCNA. Oncogene. 2004;23:1457–1468. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Habraken Y, Sung P, Prakash L, Prakash S. ATP-dependent assembly of a ternary complex consisting of a DNA mismatch and the yeast MSH2-MSH6 and MLH1-PMS1 protein complexes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9837–9841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Blackwell LJ, Wang S, Modrich P. DNA chain length dependence of formation and dynamics of hMutSa·hMutLa·heteroduplex complexes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33233–33240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105076200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Shao H, Baitinger C, Soderblom EJ, Burdett V, Modrich P. Hydrolytic function of Exo1 in mammalian mismatch repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:7104–7112. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Drummond JT, Anthoney A, Brown R, Modrich P. Cisplatin and adriamycin resistance are associated with MutLα and mismatch repair deficiency in an ovarian tumor cell line. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19645–19648. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ma AH, Xia L, Littman SJ, Swinler S, Lader G, Polinkovsky A, Olechnowicz J, Kasturi L, Lutterbaugh J, Modrich P, Veigl ML, Markowitz SD, Sedwick WD. Somatic mutation of hPMS2 as a possible cause of sporadic human colon cancer with microsatellite instability. Oncogene. 2000;19:2249–2256. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Peltomaki P. Lynch syndrome genes. Fam Cancer. 2005;4:227–232. doi: 10.1007/s10689-004-7993-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wei K, Clark AB, Wong E, Kane MF, Mazur DJ, Parris T, Kolas NK, Russell R, Hou H, Jr, Kneitz B, Yang G, Kunkel TA, Kolodner RD, Cohen PE, Edelmann W. Inactivation of Exonuclease 1 in mice results in DNA mismatch repair defects, increased cancer susceptibility, and male and female sterility. Genes Dev. 2003;17:603–614. doi: 10.1101/gad.1060603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Smith CE, Mendillo ML, Bowen N, Hombauer H, Campbell CS, Desai A, Putnam CD, Kolodner RD. Dominant mutations in S. cerevisiae PMS1 identify the Mlh1-Pms1 endonuclease active site and an exonuclease 1-independent mismatch repair pathway. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Goellner EM, Smith CE, Campbell CS, Hombauer H, Desai A, Putnam CD, Kolodner RD. PCNA and Msh2-Msh6 activate an Mlh1-Pms1 endonuclease pathway required for Exo1-independent mismatch repair. Mol Cell. 2014;55:291–304. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Stith CM, Sterling J, Resnick MA, Gordenin DA, Burgers PM. Flexibility of eukaryotic Okazaki fragment maturation through regulated strand displacement synthesis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34129–34140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806668200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Doerfler L, Schmidt KH. Exo1 phosphorylation status controls the hydroxyurea sensitivity of cells lacking the Pol32 subunit of DNA polymerases delta and zeta. DNA Repair (Amst) 2014;24C:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Hombauer H, Campbell CS, Smith CE, Desai A, Kolodner RD. Visualization of eukaryotic DNA mismatch repair reveals distinct recognition and repair intermediates. Cell. 2011;147:1040–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Gomes XV, Schmidt SL, Burgers PM. ATP utilization by yeast replication factor C. II. Multiple stepwise ATP binding events are required to load proliferating cell nuclear antigen onto primed DNA. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:34776–34783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Krishna TS, Kong XP, Gray S, Burgers P, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the eukaryotic DNA polymerase processivity factor PCNA. Cell. 1994;79:1233–1243. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Gulbis JM, Kelman Z, Hurwitz J, O′Donnell M, Kuriyan J. Structure of the C-terminal region of p21(WAF1/CIP1) complexed with human PCNA. Cell. 1996;87:297–306. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81347-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Moldovan GL, Pfander B, Jentsch S. PCNA, the maestro of the replication fork. Cell. 2007;129:665–679. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Bowman GD, O′Donnell M, Kuriyan J. Structural analysis of a eukaryotic sliding DNA clamp-clamp loader complex. Nature. 2004;429:724–730. doi: 10.1038/nature02585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kuhn H, Protozanova E, Demidov VV. Monitoring of single nicks in duplex DNA by gel electrophoretic mobility-shift assay. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:2384–2387. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200208)23:15<2384::AID-ELPS2384>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Gradia S, Acharya S, Fishel R. The human mismatch recognition complex hMSH2-hMSH6 functions as a novel molecular switch. Cell. 1997;91:995–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80490-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Blackwell LJ, Martik D, Bjornson KP, Bjornson ES, Modrich P. Nucleotide-promoted release of hMutSa from heteroduplex DNA is consistent with an ATP-dependent translocation mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32055–32062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Grilley M, Welsh KM, Su S-S, Modrich P. Isolation and characterization of the Escherichia coli mutL gene product. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:1000–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Lahue RS, Au KG, Modrich P. DNA mismatch correction in a defined system. Science. 1989;245:160–164. doi: 10.1126/science.2665076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Fukui K, Nishida M, Nakagawa N, Masui R, Kuramitsu S. Bound nucleotide controls the endonuclease activity of mismatch repair enzyme MutL. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12136–12145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800110200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Correa EM, Martina MA, De Tullio L, Argarana CE, Barra JL. Some amino acids of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa MutL D(Q/M)HA(X)(2)E(X)(4)E conserved motif are essential for the in vivo function of the protein but not for the in vitro endonuclease activity. DNA Repair (Amst) 2011;10:1106–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Iino H, Kim K, Shimada A, Masui R, Kuramitsu S, Fukui K. Characterization of C- and N-terminal domains of Aquifex aeolicus MutL endonuclease: N-terminal domain stimulates the endonuclease activity of C-terminal domain in a zinc-dependent manner. Biosci Rep. 2011;31:309–322. doi: 10.1042/BSR20100116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Mauris J, Evans TC. Adenosine triphosphate stimulates Aquifex aeolicus MutL endonuclease activity. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Mizushima R, Kim JY, Suetake I, Tanaka H, Takai T, Kamiya N, Takano Y, Mishima Y, Tajima S, Goto Y, Fukui K, Lee YH. NMR characterization of the interaction of the endonuclease domain of MutL with divalent metal ions and ATP. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Correa EM, De Tullio L, Velez PS, Martina MA, Argarana CE, Barra JL. Analysis of DNA structure and sequence requirements for Pseudomonas aeruginosa MutL endonuclease activity. J Biochem. 2013;154:505–511. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvt080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Duppatla V, Bodda C, Urbanke C, Friedhoff P, Rao DN. The C-terminal domain is sufficient for endonuclease activity of Neisseria gonorrhoeae MutL. Biochem J. 2009;423:265–277. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Namadurai S, Jain D, Kulkarni DS, Tabib CR, Friedhoff P, Rao DN, Nair DT. The C-terminal domain of the MutL homolog from Neisseria gonorrhoeae forms an inverted homodimer. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Shimada A, Kawasoe Y, Hata Y, Takahashi TS, Masui R, Kuramitsu S, Fukui K. MutS stimulates the endonuclease activity of MutL in an ATP-hydrolysis-dependent manner. FEBS J. 2013;280:3467–3479. doi: 10.1111/febs.12344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Wang TF, Kleckner N, Hunter N. Functional specificity of MutL homologs in yeast: evidence for three Mlh1-based heterocomplexes with distinct roles during meiosis in recombination and mismatch correction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13914–13919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Ranjha L, Anand R, Cejka P. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mlh1-Mlh3 heterodimer is an endonuclease that preferentially binds to Holliday junctions. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:5674–5686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.533810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Rogacheva MV, Manhart CM, Chen C, Guarne A, Surtees J, Alani E. Mlh1-Mlh3, a meiotic crossover and DNA mismatch repair factor, is a Msh2-Msh3-stimulated endonuclease. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:5664–5673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.534644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]