ABSTRACT

The plant-pathogenic bacterium Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria employs a type III secretion (T3S) system to translocate effector proteins into plant cells. The T3S apparatus spans both bacterial membranes and is associated with an extracellular pilus and a channel-like translocon in the host plasma membrane. T3S is controlled by the switch protein HpaC, which suppresses secretion and translocation of the predicted inner rod protein HrpB2 and promotes secretion of translocon and effector proteins. We previously reported that HrpB2 interacts with HpaC and the cytoplasmic domain of the inner membrane protein HrcU (C. Lorenz, S. Schulz, T. Wolsch, O. Rossier, U. Bonas, and D. Büttner, PLoS Pathog 4:e1000094, 2008, http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1000094). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the control of HrpB2 secretion are not yet understood. Here, we located a T3S and translocation signal in the N-terminal 40 amino acids of HrpB2. The results of complementation experiments with HrpB2 deletion derivatives revealed that the T3S signal of HrpB2 is essential for protein function. Furthermore, interaction studies showed that the N-terminal region of HrpB2 interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of HrcU, suggesting that the T3S signal of HrpB2 contributes to substrate docking. Translocation of HrpB2 is suppressed not only by HpaC but also by the T3S chaperone HpaB and its secreted regulator, HpaA. Deletion of hpaA, hpaB, and hpaC leads to a loss of pathogenicity but allows the translocation of fusion proteins between the HrpB2 T3S signal and effector proteins into leaves of host and non-host plants.

IMPORTANCE The T3S system of the plant-pathogenic bacterium Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria is essential for pathogenicity and delivers effector proteins into plant cells. T3S depends on HrpB2, which is a component of the predicted periplasmic inner rod structure of the secretion apparatus. HrpB2 is secreted during the early stages of the secretion process and interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of the inner membrane protein HrcU. Here, we localized the secretion and translocation signal of HrpB2 in the N-terminal 40 amino acids and show that this region is sufficient for the interaction with the cytoplasmic domain of HrcU. Our results suggest that the T3S signal of HrpB2 is required for the docking of HrpB2 to the secretion apparatus. Furthermore, we provide experimental evidence that the N-terminal region of HrpB2 is sufficient to target effector proteins for translocation in a nonpathogenic X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strain.

INTRODUCTION

Pathogenicity of many Gram-negative plant- and animal-pathogenic bacteria depends on a type III secretion (T3S) system, which translocates bacterial effector proteins directly into eukaryotic host cells (1). T3S systems are highly complex protein machines and consist of ring structures in the inner membrane (IM) and outer membrane (OM) (2, 3). The IM ring is associated with the export apparatus, which is assembled by members of at least five different families of transmembrane proteins, designated YscR, YscS, YscT, YscV, and YscU. The nomenclature refers to Ysc proteins from the animal-pathogenic bacterium Yersinia (1, 4). Components of the export apparatus interact with the predicted cytoplasmic ring structure (C ring) and the ATPase complex, which provides the energy for the transport process and/or contributes to the unfolding of T3S substrates prior to their entry into the T3S system (5). The ATPase, the predicted C ring, and the cytoplasmic domains of members of the YscU and YscV families of IM proteins were reported to interact with secreted proteins, suggesting that they are involved in substrate recognition (2).

Proteins destined for type III-dependent secretion can be grouped into (i) extracellular components of the T3S system, such as pilus/needle and translocon proteins, and (ii) effector proteins, which are translocated into eukaryotic cells. Effector protein delivery depends on the extracellular T3S pilus or needle, which is associated with the membrane-spanning secretion apparatus and serves as a transport channel for secreted proteins to the host-pathogen interface (2). The translocation of effector proteins across the eukaryotic plasma membrane is mediated by the bacterial channel-like T3S translocon (6). Secretion and translocation of T3S substrates depend on an export signal, which is not conserved on the amino acid level and is often located in the N-terminal 20 to 30 amino acids (2). Despite the lack of amino acid sequence conservation, many T3S signals consist of specific amino acid compositions or patterns and are often structurally disordered (7–12). In some T3S substrates, export signals have also been identified in the C-terminal protein region or the 5′ region of the mRNA (13–17). Given that mRNA-based T3S signals probably do not account for the observed rapid transport rates of type III effectors, a combination of signals present in the mRNA and the N-terminal peptide sequence has been proposed (18, 19, 20–22). In addition to the T3S signal, the efficient secretion of many T3S substrates also depends on T3S chaperones, which bind to and often stabilize secreted proteins and facilitate their recognition by components of the T3S system (23–28). The precise molecular mechanisms underlying the recognition of T3S substrates by components of the T3S system as well as the role of the T3S signal in substrate docking are not yet understood.

In the present study, we analyzed the secretion and translocation signal of the T3S system component HrpB2 from the plant-pathogenic bacterium Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria (29). The hrpB2 gene is part of the chromosomal hrp (hypersensitive response and pathogenicity) gene cluster, which encodes components of the T3S system (30). hrpB2 expression is activated in planta and in specific minimal media by the products of two regulatory genes, hrpG and hrpX, which are the key regulators of the hrp gene cluster (31, 32). Deletion of hrpB2 leads to a loss of pathogenicity, suggesting that HrpB2 is an essential component of the T3S system (29). Previous studies revealed that HrpB2 predominantly localizes to the bacterial periplasm and is essential for the formation of the extracellular T3S pilus and thus for T3S (29, 33, 34). HrpB2 interacts with components of the T3S pilus and the OM ring (33); therefore, it was proposed to be a component of the predicted inner rod, which presumably provides a periplasmic assembly platform for the T3S pilus.

HrpB2 is itself secreted and translocated by the T3S system similarly to predicted inner rod proteins from animal-pathogenic bacteria (35–37). Therefore, it was suggested that HrpB2 is one of the first substrates that travels the T3S system (29). The efficient secretion and translocation of HrpB2 is suppressed by the control protein HpaC, which acts as a T3S substrate specificity switch (T3S4) protein and also promotes the secretion of translocon and effector proteins (38–40). The analysis of HrpB2 reporter fusions revealed the presence of a translocation signal within the N-terminal 76 amino acids of HrpB2, which is suppressed by HpaC (41). The HpaC-mediated switch in T3S substrate specificity depends on the cytoplasmic domain of the IM protein HrcU (HrcUC), which interacts with both HpaC and HrpB2 (38, 40). HpaC presumably induces a conformational change in HrcUC and thus alters the substrate specificity of the T3S system from HrpB2 secretion to the secretion of translocon and effector proteins (40, 41).

There is likely a second substrate specificity switch that triggers effector protein translocation after the insertion of the translocon into the host plasma membrane. In X. campestris pv. vesicatoria, effector protein translocation depends on the general T3S chaperone HpaB and its secreted regulator, HpaA (42, 43). HpaB binds to different sequence-unrelated effector proteins and presumably targets them to the ATPase of the T3S system (23, 42). The lack of HpaB leads to a significant reduction in effector protein translocation and a loss of bacterial pathogenicity (42). Experimental evidence suggests that the activity of HpaB is regulated by the secreted HpaA protein, which binds to and thus inactivates HpaB during the assembly of the T3S system (43). In the absence of HpaA, HpaB presumably blocks the T3S system and thus interferes with the secretion of early and late substrates. Therefore, it was assumed that the secretion and translocation of HpaA after assembly of the secretion apparatus liberates HpaB and activates effector protein delivery (43).

The mechanisms underlying the recognition of early and late T3S substrates from X. campestris pv. vesicatoria by components of the T3S system are largely unknown. The results of previous interaction studies suggest that effector proteins and HrpB2 interact with the putative C ring component HrcQ and the cytoplasmic domain of the IM protein HrcV (HrcVC) (44, 45). Furthermore, as mentioned above, HrpB2 binds to the cytoplasmic domain of HrcU (38). In the present study, we localized the secretion and translocation signal in the N-terminal 40 amino acids of HrpB2. We show that this region contains a binding site for HrcUC, suggesting that the T3S signal of HrpB2 contributes to the docking of HrpB2 to HrcUC. Furthermore, we provide experimental evidence that the translocation of HrpB2 is suppressed not only by HpaC but also by the general T3S chaperone HpaB and its regulator, HpaA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli and X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strains were cultivated at 37°C in lysogeny broth (LB) and at 30°C in nutrient-yeast-glycerol (NYG) medium (46), respectively. For the analysis of in vitro T3S, X. campestris pv. vesicatoria was cultivated in minimal medium A (47) supplemented with sucrose (10 mM) and Casamino Acids (0.3%).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| X. campestris pv. vesicatoria | ||

| 85-10 | Pepper-race 2; wild type; Rifr | 49, 80 |

| 85* | 85-10 derivative containing the hrpG* mutation | 58 |

| 85*ΔavrBs1 | 85* derivative containing a 1,251-bp in-frame deletion in avrBs1 | This study |

| 85*ΔhrcN | 85* derivative deleted in the ATPase gene hrcN | 23 |

| 85*ΔhpaA | 85* derivative with a 532-bp deletion in hpaA and a frameshift | 43 |

| 85*ΔhpaB | Derivative of strain 85* deleted in codons 13 to 149 of hpaB | 42 |

| 85*ΔavrBs1ΔhpaB | 85* derivative deleted in avrBs1 and hpaB | This study |

| 85*ΔhpaC | 85* derivative deleted in the T3S4 gene hpaC | 81 |

| 85-10ΔhpaC | 85-10 derivative deleted in the T3S4 gene hpaC | 81 |

| 85*ΔavrBs1ΔhpaC | 85* derivative deleted in avrBs1 and hpaC | This study |

| 85*ΔhpaAB | Derivative of strain 85* deleted in hpaA and hpaB | 43 |

| 85*ΔhpaAC | Derivative of strain 85* deleted in hpaA and hpaC | This study |

| 85*ΔhpaBC | Derivative of strain 85* deleted in hpaB and hpaC | 81 |

| 85*ΔhpaABC | Derivative of strain 85* deleted in hpaA, hpaB and hpaC | This study |

| 85-10ΔhpaABC | Derivative of strain 85-10 deleted in hpaA, hpaB and hpaC | This study |

| 85*ΔhpaABCΔhrcN | Derivative of strain 85* deleted in hpaA, hpaB, hpaC and hrcN | This study |

| 85*ΔhpaCΔhrpF | Derivative of strain 85* deleted in hpaC and hrpF | 41 |

| 85*ΔhpaCΔhrpE | Derivative of strain 85* deleted in hpaC and hrpE | 38 |

| 85-10ΔhrpB2 | Derivative of strain 85-10 deleted in hrpB2 | 29 |

| 85*ΔhrpB2 | Derivative of strain 85* deleted in hrpB2 | 29 |

| 85*ΔhrpB2ΔhpaC | Derivative of strain 85* deleted in hrpB2 and hpaC | 33 |

| E. coli | ||

| BL21(DE3) | F− ompT hsdSB (rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) | Stratagene |

| Top10 | F− mcrAΔ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) ϕ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 araΔ139Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| DH5αλpir | F− recA hsdR17(rK− mK+) ϕ80dlacZΔM15 [λpir] | 82 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBRM | Golden Gate-compatible derivative of pBBR1MCS-5 containing the lac promoter, a lacZα fragment flanked by BsaI recognition sites and a 3× c-Myc epitope-encoding sequence; Gmr | 83 |

| pBRMavrBs1 | Derivative of pBRM encoding AvrBs1-c-Myc | This study |

| pBRMhrcU265–357 | Derivative of pBRM encoding HrcU265–357-c-Myc | 40 |

| pBRMhrpB21–40-avrBs1 | Derivative of pBRM encoding HrpB21–40-AvrBs1-c-Myc | This study |

| pBRMhrpB2Stop | Derivative of pBRM encoding HrpB2 | This study |

| pBRMhrpB2Δ2–8Stop | Derivative of pBRM encoding HrpB2Δ2–8 | This study |

| pBRMhrpB2Δ2–9Stop | Derivative of pBRM encoding HrpB2Δ2–9 | This study |

| pBRMhrpB2Δ2–10Stop | Derivative of pBRM encoding HrpB2Δ2–10 | This study |

| pBRMhrpB2Δ2–11Stop | Derivative of pBRM encoding HrpB2Δ2–11 | This study |

| pBRMhrpB2Δ2–20Stop | Derivative of pBRM encoding HrpB2Δ2–20 | This study |

| pBRMhrpB21–90Stop | Derivative of pBRM encoding HrpB21–90 | This study |

| pBRMhrpB21–90/Δ2–10Stop | Derivative of pBRM encoding HrpB21–90/Δ2–10 | This study |

| pBRMhrpB21–20-356 | Derivative of pBR356 encoding HrpB21–20-AvrBs3Δ2 | This study |

| pBRMhrpB21–25-356 | Derivative of pBR356 encoding HrpB21–25-AvrBs3Δ2 | This study |

| pBRMhrpB21–30-356 | Derivative of pBR356 encoding HrpB21–30-AvrBs3Δ2 | This study |

| pBRMhrpB21–40-356 | Derivative of pBR356 encoding HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 | This study |

| pBRMhrpB21–40/Δ2–8-356 | Derivative of pBR356 encoding HrpB21–40/Δ2–8-AvrBs3Δ2 | This study |

| pBRMhrpB21–40/Δ2–9-356 | Derivative of pBR356 encoding HrpB21–40/Δ2–9-AvrBs3Δ2 | This study |

| pBRMhrpB21–40/Δ13–22-356 | Derivative of pBR356 encoding HrpB21–40/Δ13–22-AvrBs3Δ2 | This study |

| pBRMhrpB21–40/Δ12–25-356 | Derivative of pBR356 encoding HrpB21–40/Δ12–25-AvrBs3Δ2 | This study |

| pBRMhrpB21–40/Δ16–25-356 | Derivative of pBR356 encoding HrpB21–40/Δ16–25-AvrBs3Δ2 | This study |

| pBR356 | Derivative of plasmid pBBR1MCS-5 containing avrBs3Δ2 downstream of the lac promoter and the lacZα fragment, which is flanked by BsaI sites | This study |

| pDSK602 | Broad-host-range vector; contains triple lacUV5 promoter; Smr | 84 |

| pDS356F | Derivative of pDSK602 encoding AvrBs3Δ2-FLAG | 60 |

| pGEX-6p-1 | GST expression vector; pBR322 ori; Apr | GE Healthcare |

| pGhrpB2 | Derivative of pGEX-2TKM encoding GST-HrpB2 | 39 |

| pGhrpB2Δ2–20 | Derivative of pGEX-2TKM encoding GST-HrpB2Δ2–20 | This study |

| pGhrpB2Δ2–40 | Derivative of pGEX-2TKM encoding GST-HrpB2Δ2–40 | This study |

| pGhrpB21–40 | Derivative of pGEX-2TKM encoding GST-HrpB21–40 | This study |

| pGhrpB21–40/Δ2–9 | Derivative of pGEX-2TKM encoding GST-HrpB21–40/Δ2–9 | This study |

| pOK1 | Suicide vector; sacB sacQ mobRK2 oriR6K; Smr | 54 |

| pOKΔhpaB | pOK1 derivative containing the flanking regions of hpaB and hpaB with an in-frame deletion of codons 13 to 149 of hpaB | 42 |

| pOKΔhpaC | pOK1 derivative containing the flanking regions of hpaC including the first 39 and the last 130 bp of the gene | 81 |

| pOKΔhrcN | pOK1 derivative containing the flanking regions of hrcN including the first 36 and the last 33 bp of the gene | 23 |

| pOGG2 | Golden Gate-compatible derivative of pOK1 | 85 |

| pOGG2ΔavrBs1 | pOGG2 derivative containing the flanking regions, the first 58 bp and the last 28 bp of avrBs1 | This study |

| pUC19 | Cloning vector with lacZα fragment and pMB1-type ColE1 origin of replication, Apr | 86 |

| pBBRmod1 | Derivative of pBBR1MCS-5 which contains a single EcoRI and HindIII site that replace the polylinker | 83 |

| pIC18951 | Viral vector construct, a derivative of pICH17272, containing the RdRp-encoding sequence under the control of the alcA promoter and gfp | 50, 87 |

| pICH77739 | Derivative of pBIN19, RK2 ori, level 2 vector containing the lacZα flanked by BpiI sites; Kmr | 53, S. Marillonnet, unpublished |

| pAGB128/1 | Derivative of pICH77739 encoding dTALE-2 | This study |

| pAGB146/1 | Derivative of pICH77739 encoding dTALE-2ΔN deleted in the N-terminal 64 amino acids | This study |

| pAGB143/1 | Derivative of pICH77739 encoding HrpB21–40-dTALE-2ΔN | This study |

| pAGB145/1 | Derivative of pICH77739 encoding HrpB21–40/Δ2–9-dTALE-2ΔN | This study |

| pAGB144/1 | Derivative of pICH77739 encoding HrpB21–40/Δ2–10-dTALE-2ΔN | This study |

Ap, ampicillin; Km, kanamycin; Rif, rifampin; Sm, spectinomycin; Gm, gentamicin.

Plant material and infection experiments.

X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strains were inoculated into leaves of the near-isogenic pepper cultivars Early Cal Wonder (ECW), ECW-10R, and ECW-30R, as well as into leaves of gfp (green fluorescent protein)-transgenic N. benthamiana at a concentration of 4 × 108 CFU ml−1 in 1 mM MgCl2 if not stated otherwise (30, 48, 49). gfp-transgenic N. benthamiana plants were generated using the viral construct pICH18951, which contains the gfp gene and the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp)-encoding sequence downstream of the alcA promoter as described previously (50). After infection, pepper plants were incubated in an incubation chamber for 16 h of light at 28°C and 65% humidity and 8 h of darkness at 22°C and 65% humidity. N. benthamiana plants were incubated for 16 h of light at 20°C and 75% humidity and 8 h of darkness at 18°C and 70% humidity. The appearance of plant reactions was scored over a period of 1 to 12 days postinfection (dpi). For the better visualization of the hypersensitive response (HR), leaves were destained in 70% ethanol. In planta bacterial growth curves were performed as described previously (30). Experiments were repeated at least twice.

Generation of expression constructs.

To generate plasmid pBR356, the lacZα gene from pUC19 was amplified by PCR and primers lacZ-for and lacZ-BstY-rev (Table 2) from pUC19. The corresponding PCR fragment was digested with BpiI and ligated with avrBs3Δ2, which was excised from plasmid pBS300 by HindIII and partial BstYI digestion into pBBR1mod1, generating pBR356.

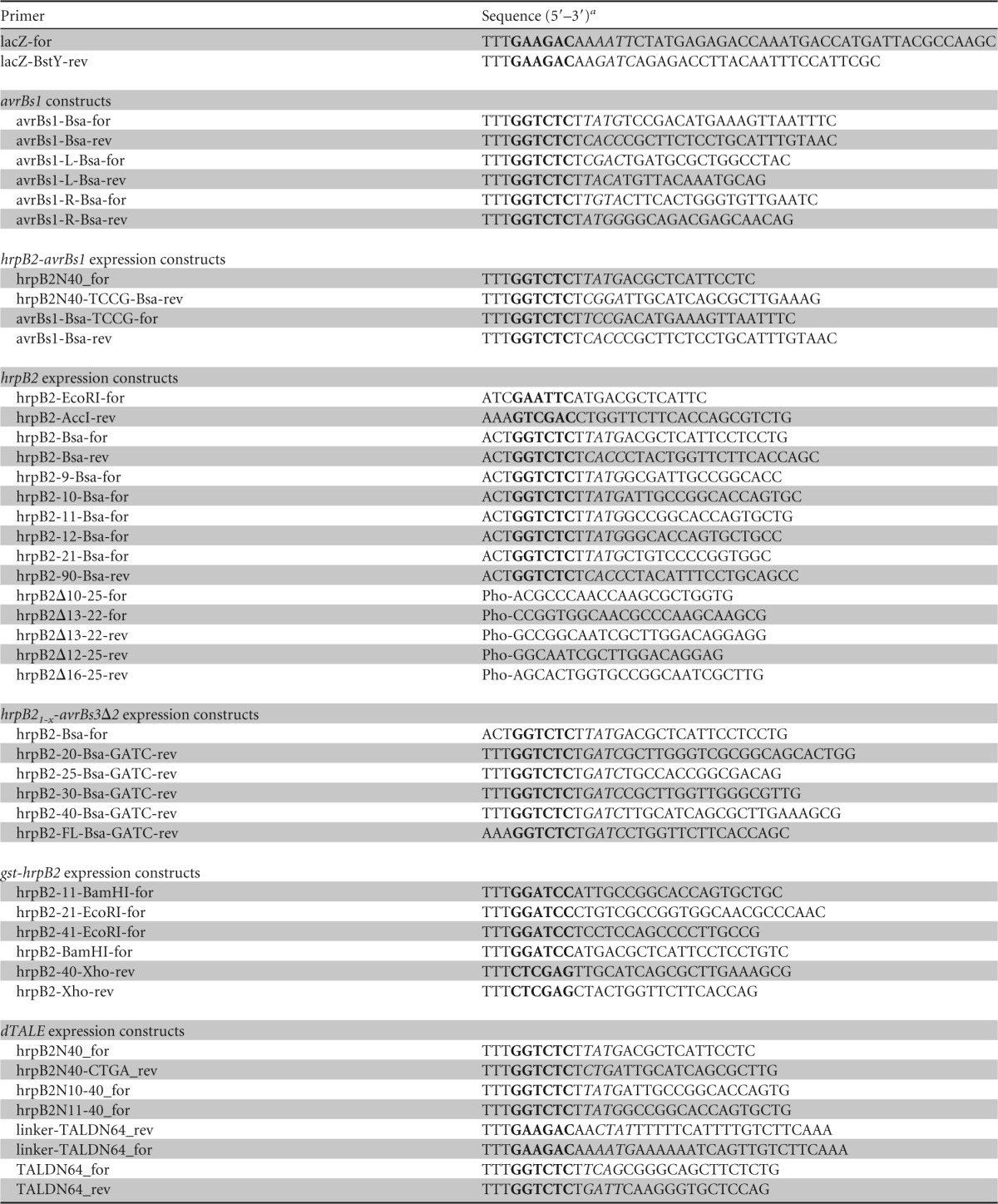

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

Recognition sites of restriction enzymes are indicated in boldface, and overhangs generated after restriction by BsaI or BpiI are in italics. Pho, 5′ phosphate group.

For the generation of hrpB2 expression constructs, hrpB2 fragments, including the stop codon, were amplified by PCR from X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strain 85-10 and cloned into the Golden Gate-compatible expression vector pBRM in a restriction/ligation reaction (51). pBRM contains a lac promoter upstream of the lacZα gene. The lacZα gene is flanked by recognition sites for the type IIS enzyme BsaI. To introduce internal deletions into the 5′ region of hrpB2, hrpB2 was first cloned using SmaI and ligase into pUC57ΔBsaI, giving pUC57hrpB2 (52). hrpB2 deletion derivatives were generated by PCR using pUC57hrpB2 as the template and primers that contained a 5′ phosphate group and were annealed back to back to the flanking sequences of the deleted regions. The resulting hrpB2 fragments were cloned into pBRM using BsaI and ligase.

For the generation of glutathione S-transferase (GST) expression constructs, derivatives of hrpB2 were amplified by PCR and cloned into the BamHI and XhoI sites of pGEX-6p-1. To obtain expression constructs encoding HrpB2-AvrBs3Δ2 fusions, 5′ regions of hrpB2 were amplified by PCR and cloned into the BsaI sites of the Golden Gate-compatible vector pBR356. dTALE-2 (designer transcription activator-like effector) expression constructs and derivatives thereof were generated by Golden Gate assembly of individual DNA modules (51, 53). For the generation of the dTALE-2 expression construct, modules containing the lac promoter, the dTALE-2-encoding sequence, and a transcription terminator were combined. The expression construct encoding dTALE-2ΔN was assembled with modules encoding a linker of lysine residues, amino acids 65 to 288, the central repeats, and the C-terminal region of dTALE-2. The module containing the linker was generated by annealing two oligonucleotides. For the generation of HrpB21-x-dTALE-2ΔN expression constructs, we generated modules encoding amino acids 1 to 40, 10 to 40, and 11 to 40 of HrpB2, respectively, and assembled them with modules encoding the N-terminal, the repeat, and the C-terminal regions of dTALE-2ΔN in a Golden Gate reaction mixture as described above. The DNA sequences of the final constructs are given in the supplemental material. All primer sequences are listed in Table 2.

Generation of X. campestris pv. vesicatoria deletion mutants.

For the generation of X. campestris pv. vesicatoria deletion mutants, we used derivatives of the suicide vector pOK1, which contained the flanking regions of the deleted genes (Table 1). For the generation of the avrBs1 deletion mutant, 727-bp and 692-bp fragments flanking avrBs1 and containing the last 29 and the first 58 bp of avrBs1, respectively, were amplified by PCR and cloned into the Golden Gate-compatible vector pOGG2. Derivatives of pOK1 and pOGG2 were introduced into X. campestris pv. vesicatoria by triparental conjugation, and deletion mutants were selected as described previously (54).

Preparation of protein extracts and in vitro secretion assays.

For the analysis of protein synthesis, bacteria were cultivated overnight in liquid NYG medium and cells were harvested by centrifugation. Equal amounts of proteins adjusted according to the optical density of the culture were analyzed by immunoblotting, using AvrBs3- or HrpB2-specific antibodies. In vitro secretion assays were performed as described previously (55). Equal amounts of bacterial total cell extracts and culture supernatants (adjusted according to the optical density of the cultures) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using antibodies specific for AvrBs3, HrpB2, the predicted IM ring protein HrcJ, the periplasmic HrpB1 protein, and the secreted translocon protein HrpF, respectively (29, 56, 57). Horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-rabbit antibodies (GE Healthcare) were used as secondary antibodies. Experiments were performed three times.

GST pulldown assays.

GST pulldown assays were performed as described previously (33). Total protein lysates and eluted proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using antibodies specific for the c-Myc epitope and GST (Roche Applied Science), respectively. Experiments were performed at least three times.

RESULTS

The N-terminal nine amino acids of HrpB2 are dispensable for secretion and/or protein function.

We previously reported that the secretion of HrpB2 presumably depends on a protein region spanning amino acids 10 to 25 (38). To further localize the T3S signal of HrpB2 and to analyze the contribution of the N-terminal region of HrpB2 to protein function, we generated expression constructs encoding HrpB2 derivatives deleted in amino acids 2 to 8, 2 to 9, and 2 to 10, respectively. Given our earlier observation that the presence of a C-terminal epitope tag interferes with HrpB2 function (33), we analyzed untagged HrpB2 derivatives in an X. campestris pv. vesicatoria hrpB2 deletion mutant. Immunoblot analysis with an HrpB2-specific antiserum revealed that all HrpB2 derivatives were stably synthesized in the 85-10hrpG*ΔhrpB2 (85*ΔhrpB2) strain, which contains a constitutively active version of the key regulator HrpG, HrpG*, and therefore expresses the hrp genes in vitro (58) (Fig. 1A). For the analysis of T3S, bacteria were incubated in secretion medium, and cell extracts and culture supernatants were analyzed by immunoblotting. HrpB2, but not the N-terminal deletion derivatives of HrpB2, was detected in the culture supernatant of the 85*ΔhrpB2 strain, suggesting that amino acids 2 to 10 are required for the efficient secretion of HrpB2 (Fig. 1A). However, when analyzed in the 85*ΔhrpB2ΔhpaC strain, which lacks the T3S4 gene hpaC and therefore oversecretes HrpB2 (38), HrpB2Δ2–8 and HrpB2Δ2–9 were detectable in the culture supernatant. No secretion was observed for HrpB2Δ2–10 (Fig. 1B), suggesting that the N-terminal 10 amino acids are essential for secretion of HrpB2. The blots were reprobed with antibodies specific for the periplasmic HrpB1 protein and the predicted IM ring protein HrcJ to ensure that no cell lysis had occurred (Fig. 1A and B).

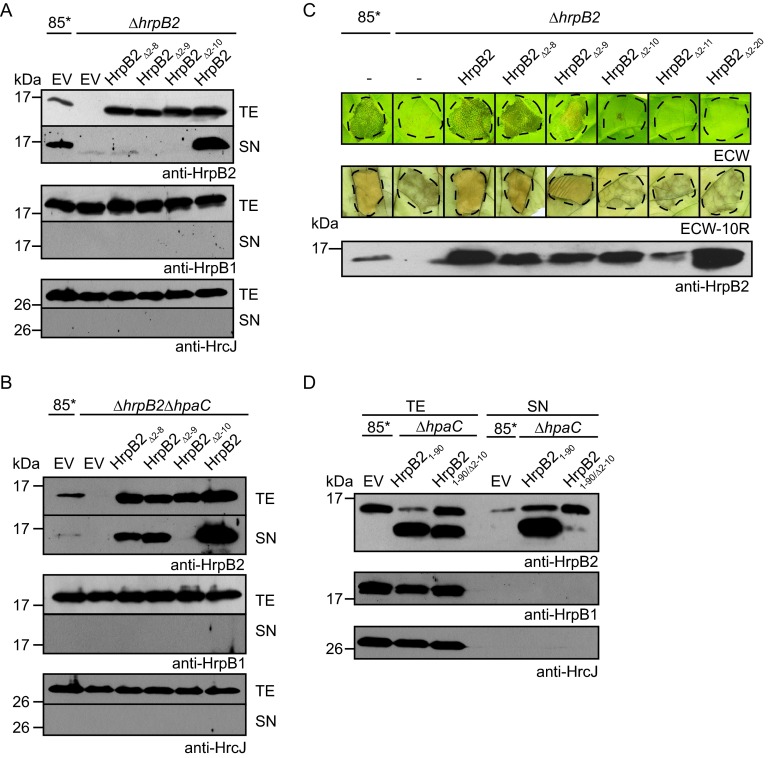

FIG 1.

N-terminal 10 amino acids are required for secretion of HrpB2 and protein function. (A) The N-terminal 10 amino acids are essential for HrpB2 secretion in X. campestris pv. vesicatoria wild-type strains. Strain 85* and the 85*ΔhrpB2 (ΔhrpB2) strain, containing the empty vector (EV) or expression constructs encoding HrpB2 or N-terminal deletion derivatives thereof, as indicated, were incubated in secretion medium. Total cell extracts (TE) and culture supernatants (SN) were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies specific for HrpB2, the periplasmic HrpB1 protein, and the IM ring protein HrcJ, respectively. (B) The N-terminal nine amino acids of HrpB2 are dispensable for HrpB2 secretion in the absence of the T3S4 protein HpaC. 85* and 85*ΔhrpB2ΔhpaC strains, containing the empty vector or expression constructs encoding HrpB2 or N-terminal deletion derivatives thereof, as indicated, were incubated in secretion medium. TE and SN were analyzed as described for panel A. (C) The N-terminal 10 amino acids of HrpB2 are essential for protein function. 85* and 85*ΔhrpB2 (ΔhrpB2) strains without plasmid (−) or with expression constructs encoding HrpB2 or N-terminal deletion derivatives thereof, as indicated, were inoculated into leaves of susceptible ECW and resistant ECW-10R pepper plants. Disease symptoms were photographed 9 dpi. For better visualization of the HR, infected leaves of ECW-10R plants were destained in ethanol 2 dpi. Dashed lines mark the infiltrated areas. (D) Secretion assays with HrpB21–90 derivatives. Strain 85* (wild type) and the 85*ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC) mutant, containing the empty vector or expression plasmids encoding HrpB21–90 or HrpB21–90/Δ2–10, as indicated, were incubated in secretion medium. TE and SN were analyzed by immunoblotting as described for panel A.

Given the essential role of HrpB2 in T3S, it cannot be excluded that the observed lack of secretion of HrpB2 derivatives was caused by their inability to compensate for the loss of HrpB2 in 85*ΔhrpB2 and 85*ΔhrpB2ΔhpaC strains. Therefore, we investigated whether HrpB2 derivatives can complement the in planta hrpB2 mutant phenotype in leaves of susceptible and resistant pepper plants. As expected, strain 85* induced water-soaked lesions in susceptible ECW plants and the HR in resistant ECW-10R plants (Fig. 1C). The HR is a local cell death response at the infection site and is part of the plant defense response, which is activated upon recognition of individual effector proteins in plants with a matching resistance gene (59). Pepper ECW-10R plants contain the resistance gene Bs1 and induce the HR upon recognition of the effector protein AvrBs1 (48). In contrast to strain 85*, no plant reactions were observed after inoculation of the hrpB2 deletion strain, as reported previously (Fig. 1C). The wild-type phenotype was restored in the 85*ΔhrpB2 strain by HrpB2, HrpB2Δ2–8, and HrpB2Δ2–9 but not by HrpB2Δ2–10 (Fig. 1C). Similar results were obtained for derivatives of the hrpG wild-type strain 85-10 and the 85-10ΔhrpB2 strain (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), suggesting that amino acids 2 to 10 of HrpB2 are essential for protein function. To confirm this finding, we generated two additional HrpB2 deletion derivatives lacking amino acids 2 to 11 and 2 to 20, respectively. As was observed for HrpB2Δ2–10, HrpB2Δ2–11 and HrpB2Δ2–20 did not restore the wild-type phenotype in 85*ΔhrpB2 (Fig. 1C) and 85-10ΔhrpB2 (see Fig. S1) strains. Loss of protein function was not caused by a dominant-negative effect of HrpB2 derivatives on the host-pathogen interaction, because ectopic expression of hrpB2 deletion derivatives in strain 85-10 did not alter the wild-type phenotype in planta (see Fig. S1).

To further analyze whether the observed lack of secretion of HrpB2Δ2–10 in 85*ΔhrpB2 and 85*ΔhrpB2ΔhpaC strains was caused by a loss of protein function (i.e., the inability of this HrpB2 derivative to complement the hrpB2 mutant phenotype) or a nonfunctional T3S signal, we also performed T3S assays with truncated HrpB2 derivatives, which were deleted in the C-terminal 40 amino acids (HrpB21–90; deletion of amino acids 91 to 130). HrpB21–90 migrated at a different molecular size than the native HrpB2 protein and therefore could be analyzed in hrpB2 wild-type strains (Fig. 1D). T3S assays with the 85*ΔhpaC strain revealed that HrpB2 and HrpB21–90 were detectable in the culture supernatant, suggesting that both proteins were secreted (Fig. 1D). In contrast, secretion of HrpB21–90/Δ2–10 was significantly reduced, indicating that the deletion of amino acids 2 to 10 interferes with HrpB2 secretion (Fig. 1D). Therefore, it is possible that the observed loss of protein function of HrpB2Δ2–10 was caused by the absence of a functional T3S signal (Fig. 1C and as described above).

The N-terminal 40 amino acids of HrpB2 provide a binding site for HrcUC.

We previously reported that the N-terminal 89 amino acids of HrpB2 are required for the binding of HrpB2 to HrcUC (amino acids 265 to 357 of HrcU) (33). To investigate whether the T3S signal of HrpB2 contributes to this interaction, we performed GST pulldown assays with GST-HrpB2 derivatives and a C-terminally c-Myc epitope-tagged derivative of HrcU265–357. GST and GST-HrpB2 derivatives were immobilized on glutathione Sepharose and incubated with bacterial lysates containing HrcU265–357-c-Myc. Immunoblot analyses of eluted proteins revealed that HrcU265–357-c-Myc coeluted with GST-HrpB2 and a GST-HrpB2 derivative lacking amino acids 2 to 20 (GST-HrpB2Δ2–20) (Fig. 2A). In contrast, HrcU265–357-c-Myc was not detected in the eluate of GST-HrpB2Δ2–40 (Fig. 2A). We also observed an interaction of HrcU265–357-c-Myc with GST-HrpB21–40 and GST-HrpB21–40/Δ2–9; however, compared to GST-HrpB2, reduced amounts of HrcU265–357-c-Myc were detected in the eluates of both fusion proteins (Fig. 2B). Taken together, these experiments suggest that the N-terminal 40 amino acids of HrpB2 are essential and sufficient for the interaction with HrcU265–357.

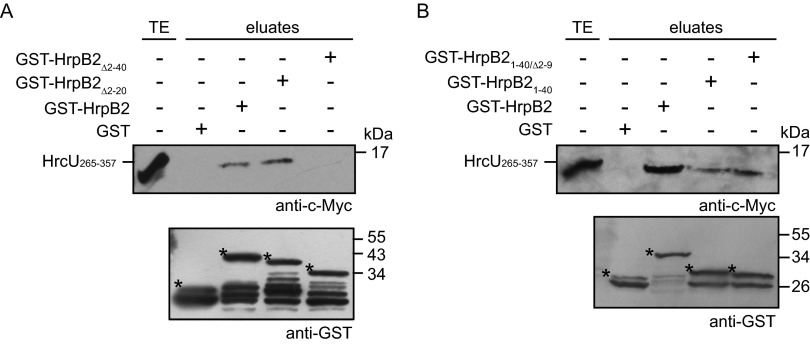

FIG 2.

N-terminal 40 amino acids of HrpB2 are essential and sufficient for the interaction with HrcUC. (A) The N-terminal 40 amino acids of HrpB2 are essential for the interaction with HrcUC. GST, GST-HrpB2, and N-terminal deletion derivatives thereof, as indicated, were immobilized on glutathione Sepharose and incubated with a bacterial lysate containing HrcU265–357-c-Myc. The total cell extract (TE) and eluted proteins (eluates) were analyzed by immunoblotting using c-Myc- and GST-specific antibodies. Asterisks indicate GST and GST fusion proteins, and additional bands presumably represent degradation products. (B) Amino acids 10 to 40 of HrpB2 are sufficient for the interaction with HrcU265–357. GST, GST-HrpB2, GST-HrpB21–40, and GST-HrpB21–40/Δ2–9 were immobilized on glutathione Sepharose and incubated with a bacterial lysate containing HrcU265–357-c-Myc. TE and eluates were analyzed as described for panel A.

The N-terminal 40 amino acids of HrpB2 harbor a functional translocation signal.

To localize the translocation signal of HrpB2, we analyzed fusion proteins between the N-terminal 20, 25, 30, and 40 amino acids of HrpB2 and the reporter protein AvrBs3Δ2, which is an N-terminal deletion derivative of the transcription activator-like (TAL) effector AvrBs3. AvrBs3Δ2 lacks amino acids 2 to 152 and, thus, the secretion and translocation signal (60). When present as a fusion partner of a functional secretion and translocation signal, AvrBs3Δ2 is translocated by the T3S system and triggers the HR in AvrBs3-responsive ECW-30R pepper plants (60, 61). HrpB21–20-AvrBs3Δ2, HrpB21–25-AvrBs3Δ2, and HrpB21–30-AvrBs3Δ2 did not elicit the AvrBs3-specific HR when analyzed in 85* and 85*ΔhpaC strains, suggesting that they were not translocated (Fig. 3A). In contrast, HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 induced the HR in leaves of ECW-30R pepper plants when delivered by the 85*ΔhpaC strain but not by 85* (Fig. 3A). This implies that the N-terminal 40 amino acids of HrpB2 contain a functional translocation signal that targets the AvrBs3Δ2 reporter for translocation in the absence of HpaC. HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 did not induce the HR when analyzed in 85*ΔhpaCΔhrpF and 85*ΔhpaCΔhrpE strains, which additionally lack the translocon gene hrpF and the pilus gene hrpE, respectively, and are deficient in T3S-dependent protein translocation (Fig. 3B). All 85* strains induced the AvrBs1-specific HR when inoculated into leaves of AvrBs1-responsive ECW-10R pepper plants, suggesting that HrpB2-AvrBs3Δ2 fusion proteins did not interfere with the activity of the T3S system (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In contrast to HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2, translocation of the full-length AvrBs3 protein was not significantly affected by the deletion of hpaC (Fig. 3B). T3S assays showed that HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 was secreted by the 85*ΔhpaC strain but was not detectable in the supernatant of strain 85* (Fig. 3C). No secretion was observed for HrpB2-AvrBs3Δ2 fusions containing the N-terminal 20, 25, or 30 amino acids of HrpB2 (Fig. 3C). This is in agreement with the results of the translocation assay and suggests that the N-terminal 30 amino acids of HrpB2 do not contain a functional secretion and translocation signal.

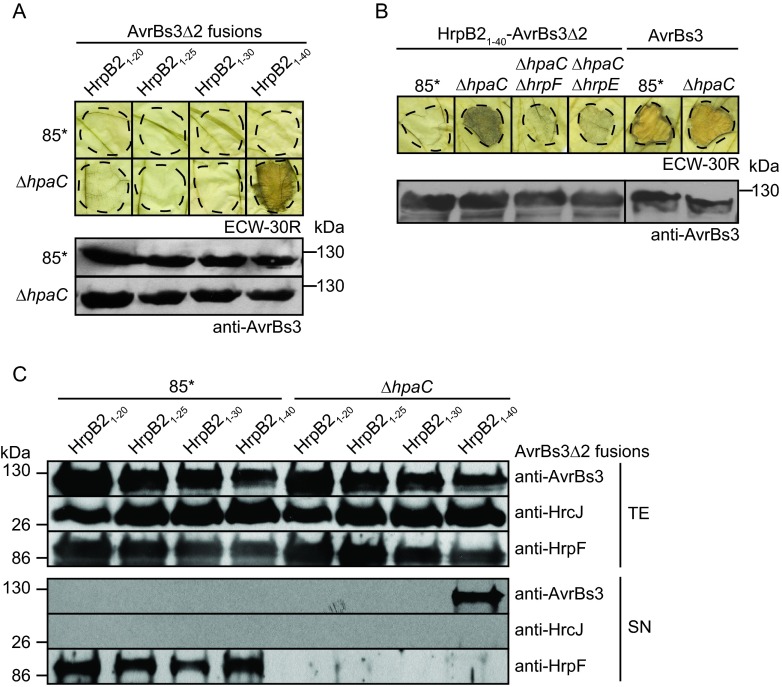

FIG 3.

N-terminal 40 amino acids of HrpB2 contain a functional translocation signal which is suppressed by HpaC. (A) The N-terminal 40 amino acids of HrpB2 target AvrBs3Δ2 for translocation. X. campestris pv. vesicatoria 85* and 85*ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC) strains, containing HrpB2-AvrBs3Δ2 fusion proteins as indicated, were inoculated into leaves of AvrBs3-responsive ECW-30R pepper plants. For the better visualization of the HR, leaves were destained in ethanol 3 dpi. Dashed lines indicate the infiltrated areas. Equal amounts of cell extracts (adjusted according to the optical density) were analyzed by immunoblotting using an AvrBs3-specific antiserum. (B) Translocation of HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 depends on a functional T3S system. 85*, 85*ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC), 85*ΔhpaCΔhrpF (ΔhpaC ΔhrpF), and 85*ΔhpaCΔhrpE (ΔhpaC ΔhrpE) strains, containing HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2, as well as 85* and 85*ΔhpaC strains, delivering AvrBs3, were inoculated into leaves of ECW-30R pepper plants. Leaves were destained in ethanol 3 dpi. Equal amounts of cell extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting as described for panel A. The phenotypes on ECW-10R plants are shown in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material. (C) Secretion of HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 is suppressed by HpaC. 85* and 85*ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC) strains, containing HrpB2-AvrBs3Δ2 fusion proteins as indicated, were incubated in secretion medium, and total cell extracts (TE) and culture supernatants (SN) were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies specific for AvrBs3, the predicted IM ring protein HrcJ, and the secreted translocon protein HrpF. As expected, secretion of HrpF is reduced in hpaC deletion mutants.

To further analyze the contribution of the N-terminal region of HrpB2 to translocation, we performed translocation assays with HrpB21–40/Δ2–8-AvrBs3Δ2 and HrpB21–40/Δ2–9-AvrBs3Δ2 fusion proteins, which are deleted in amino acids 2 to 8 and 2 to 9 of HrpB2, respectively. Compared with HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2, both fusion proteins induced a reduced and delayed AvrBs3-specific HR after delivery by the 85*ΔhpaC strain, suggesting that amino acids 2 to 9 contribute to but are not essential for the translocation of HrpB2 (Fig. 4A). Similar results were obtained with the hrpG wild-type 85-10ΔhpaC strain (Fig. 4A). As expected, HrpB21–40/Δ2–8-AvrBs3Δ2 and HrpB21–40/Δ2–9-AvrBs3Δ2 were secreted by the 85*ΔhpaC strain, and small amounts of both proteins were also detected in the culture supernatant of strain 85* (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

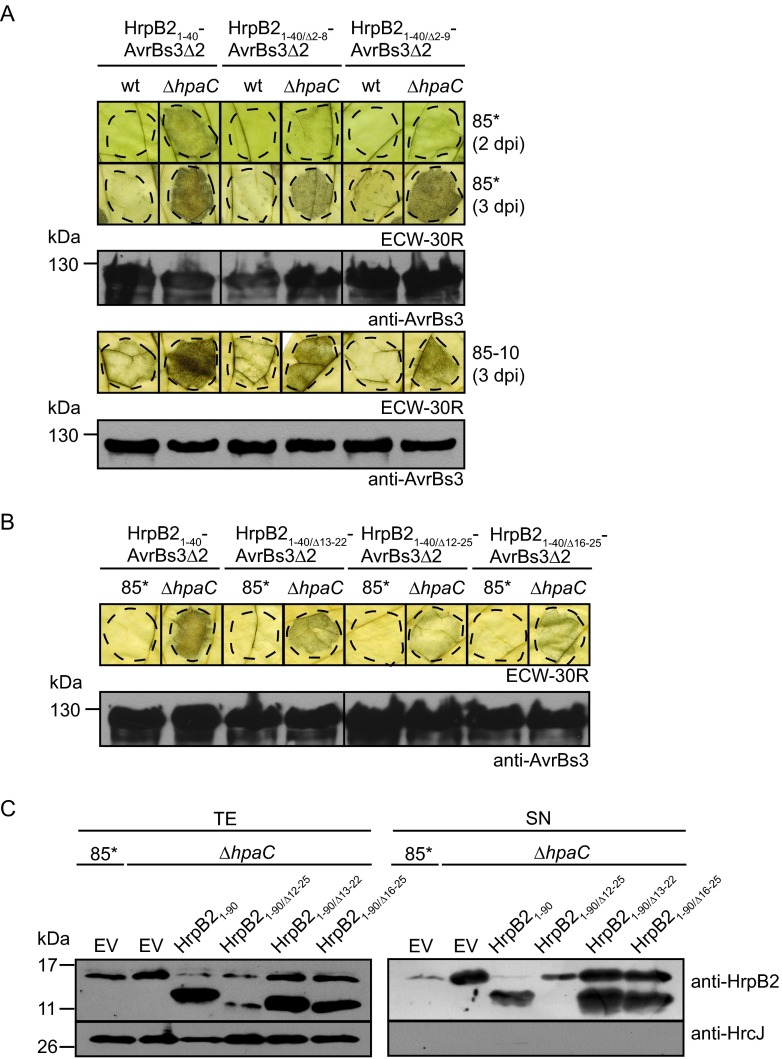

FIG 4.

Amino acids 2 to 9 and 12 to 25 are dispensable for translocation of HrpB2. (A) HrpB21–40/Δ2–8-AvrBs3Δ2 and HrpB21–40/Δ2–9-AvrBs3Δ2 are translocated by the hpaC deletion mutant. Strains 85* (wt) and 85-10 (wt) and the 85*ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC) and 85-10ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC) mutants, containing HrpB2-AvrBs3Δ2 fusion proteins as indicated, were inoculated into leaves of AvrBs3-responsive ECW-30R plants. For the better visualization of the HR, leaves were destained in ethanol 2 and 3 dpi. Dashed lines indicate the infiltrated areas. Equal amounts of cell extracts (adjusted according to the optical density) were analyzed by immunoblotting using an AvrBs3-specific antiserum. Fusion proteins did not interfere with the AvrBs1-specific HR, as shown in Fig. S3 in the supplemental material. (B) Amino acids 12 to 25 are dispensable for the translocation of HrpB2-AvrBs3Δ2 fusion proteins. Strain 85* and the 85*ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC) mutant, containing HrpB2-AvrBs3Δ2 fusion proteins as indicated, were inoculated into leaves of AvrBs3-responsive ECW-30R plants. Leaves were destained in ethanol 3 dpi. Fusion proteins were analyzed as described for panel A. The phenotypes on ECW-10R plants are shown in Fig. S3. (C) Secretion assays with C-terminal deletion derivatives of HrpB2 containing deletions within the region spanning amino acids 12 to 25. Strain 85* and the 85*ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC) mutant, containing the empty vector (EV), HrpB21–90, and derivatives thereof, as indicated, were incubated in secretion medium. Total cell extracts (TE) and culture supernatants (SN) were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies specific for HrpB2 and HrcJ, respectively.

Amino acids 12 to 25 are dispensable for secretion and translocation of HrpB2.

We also investigated the possible contribution of internal N-terminal protein regions of HrpB2 to translocation. For this, we generated HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 fusion proteins with deletions of amino acids 13 to 22, 12 to 25, and 16 to 25, respectively. All fusion proteins induced the AvrBs3-specific HR when delivered by the 85*ΔhpaC strain (Fig. 4B). However, compared to that of HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2, the HR induced by HrpB21–40/Δ13–22-AvrBs3Δ2, HrpB21–40/Δ12–25-AvrBs3Δ2, and HrpB21–40/Δ16–25-AvrBs3Δ2 was slightly reduced (Fig. 4B). To investigate the contribution of amino acids 12 to 25 to the secretion of HrpB2, we generated HrpB21–90 derivatives with internal deletions. Secretion of HrpB21–90 in the 85*ΔhpaC strain was not significantly affected by deletions of amino acids 13 to 22 and 16 to 25, respectively (Fig. 4C). In contrast, HrpB21–90/Δ12–25 was not detectable in the culture supernatant of the 85*ΔhpaC strain (Fig. 4C). However, the protein was probably unstable because it was only present in small amounts in the cell extract (Fig. 4C). Taken together, we conclude from these findings that amino acids 12 to 25 contribute to but are not essential for the secretion and translocation of HrpB2. The results of the secretion and translocation assays with HrpB2 derivatives and reporter fusion proteins are summarized in Tables 3 and 4.

TABLE 3.

Results of in vitro T3S assays with HrpB2 derivatives

| HrpB2 derivative | Secretion in mutanta: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔhpaC | ΔhrpB2 | ΔhrpB2 ΔhpaC | |

| HrpB2 | NA | + | + |

| HrpB2Δ2–8 | NA | − | + |

| HrpB2Δ2–9 | NA | − | + |

| HrpB2Δ2–10 | NA | − | − |

| HrpB21–90 | + | NA | NA |

| HrpB21–90/Δ2–10 | +/− | NA | NA |

| HrpB21–90/Δ12–25b | − | NA | NA |

| HrpB21–90/Δ13–22 | + | NA | NA |

| HrpB21–90/Δ16–25 | + | NA | NA |

NA, not analyzed; +, secreted; +/−, significantly reduced secretion; −, no secretion detectable.

Protein is unstable in cell extracts of X. campestris pv. vesicatoria.

TABLE 4.

Results of translocation assays

| Protein-reporter fusion | Result of translocation assaysa |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt | ΔhpaC | ΔhpaB | ΔhpaBC | ΔhpaA | ΔhpaAC | ΔhpaAB | ΔhpaABC | |

| AvrBs3 | + | + | + | + | NA | NA | NA | + |

| AvrBs3Δ2 fusion partners | ||||||||

| HrpB21–20 | − | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| HrpB21–25 | − | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| HrpB21–30 | − | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| HrpB21–40b | − | + | − | ++ | − | − | +/− | ++ |

| HrpB21–40/Δ2–8 | − | +/− | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | + |

| HrpB21–40/Δ2–9 | − | +/− | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | + |

| HrpB21–40/Δ13–22 | − | +/− | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| HrpB21–40/Δ12–25 | − | +/− | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| HrpB21–40/Δ16–25 | − | +/− | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| AvrBs1 | +c | NA | +/−c | − | NA | NA | NA | − |

| AvrBs1 fusion partners | ||||||||

| HrpB21–40 | +d | +d | +d | + | NA | NA | NA | + |

| dTALE-2 | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | +/−e |

| dTALE-2ΔN | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | − |

| dTALE-2ΔN fusion partners | ||||||||

| HrpB21–40 | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | +e |

| HrpB21–40/Δ2–9 | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | (+/−) |

| HrpB21–40/Δ2–10 | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | − |

For translocation assays, X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strain 85* and hpa deletion mutants containing effector proteins or effector fusions were inoculated at an optical density of 4 × 108 CFU ml−1 into leaves of AvrBs1- or AvrBs3-responsive pepper plants. wt, wild type. For AvrBs3 and its AvrBs3Δ2 fusion partners, translocation assays were performed in AvrBs3-responsive pepper plants; for AvrBs1 and its fusion partners, translocation assays were performed in AvrBs1-responsive pepper plants; for dTALE-2 and its dTALE-2ΔN fusion partners, assays were performed in gfp-transgenic N. benthamiana. Symbols for pepper plant assays: +, HR induction; ++, strong HR induction; +/−, reduced HR induction; −, no HR induction visible; NA, not analyzed. Symbols for N. benthamiana assay (strain 85* induces a necrosis reaction in N. benthamiana): +, fluorescence; +/−, weak fluorescence; (+/−), only a few fluorescent spots were detectable; −, no detectable fluorescence.

HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 was not translocated when analyzed in 85*ΔhpaCΔhrpF, 85*ΔhpaCΔhrpE, and 85*ΔhpaABCΔhrcN strains.

Translocation of AvrBs1-c-Myc was analyzed in 85*ΔavrBs1 and 85*ΔavrBs1ΔhpaB strains.

Translocation of HrpB21–40-AvrBs1-c-Myc was analyzed in 85*ΔavrBs1, 85*ΔavrBs1ΔhpaB, and 85*ΔavrBs1ΔhpaC strains.

No fluorescence was detectable with the 85*ΔhpaABCΔhrcN strain.

HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 is efficiently translocated by the nonpathogenic hpaABC deletion mutant.

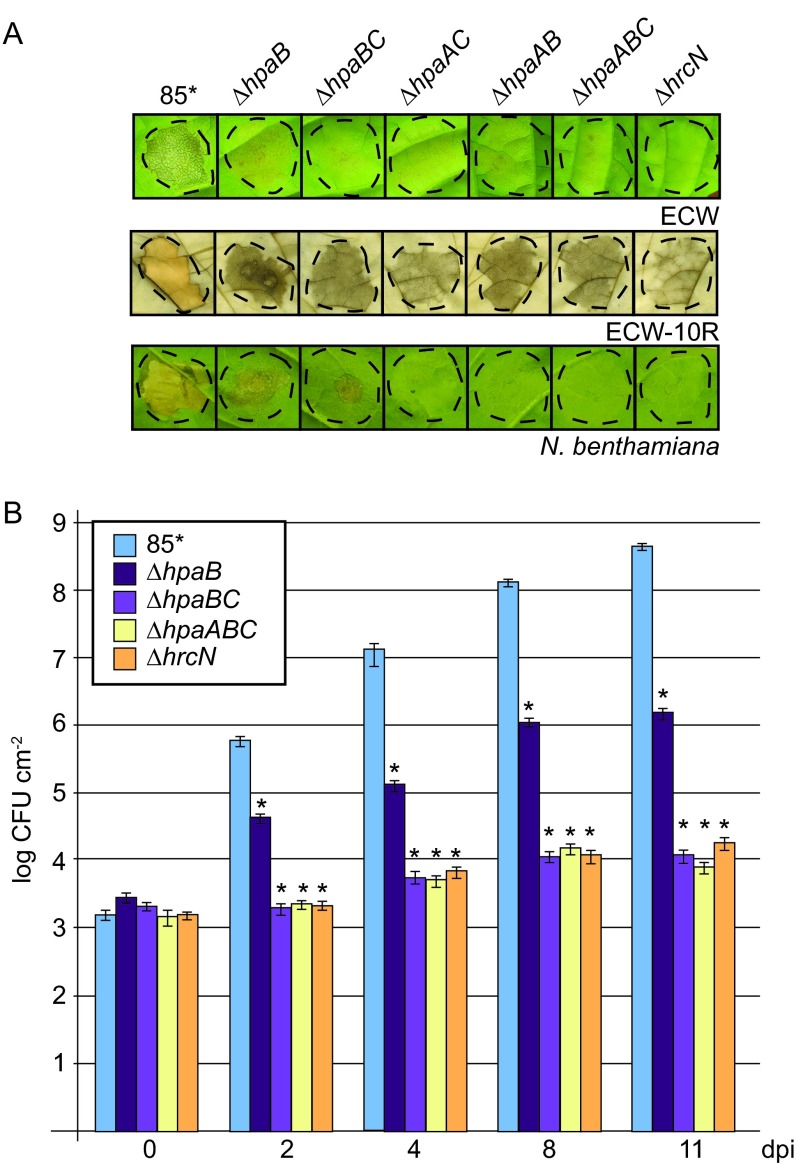

To investigate whether the translocation of HrpB2 is controlled not only by HpaC but also by additional Hpa proteins, we performed translocation assays with derivatives of strain 85* deleted in genes encoding the general T3S chaperone HpaB or its secreted regulator, HpaA. We also generated double and triple deletion mutants lacking hpaAB, hpaAC, and hpaABC. To investigate whether the combined deletion of several hpa genes leads to a loss of pathogenicity, bacteria were inoculated into leaves of susceptible ECW and resistant ECW-10R pepper plants. In contrast to 85*, the 85*ΔhpaAB, 85*ΔhpaAC, 85*ΔhpaBC, and 85*ΔhpaABC strains did not induce visible plant reactions, suggesting that they were not pathogenic (Fig. 5A). The analysis of the in planta bacterial growth revealed that strain 85* reached approximately 108 CFU cm−2 by 9 dpi, whereas growth of 85*ΔhpaB, 85*ΔhpaBC, and 85*ΔhpaABC strains was significantly reduced (Fig. 5B). Given the contribution of HpaA, HpaB, and HpaC to effector protein secretion, this suggests that 85*ΔhpaB, 85*ΔhpaBC, and 85*ΔhpaABC strains fail to efficiently translocate effector proteins into plant cells.

FIG 5.

hpaABC mutants do not induce macroscopic reactions on host and non-host plants. (A) Double and triple hpa deletion mutants do not elicit reactions in pepper and N. benthamiana leaves. Strain 85* and the 85*ΔhpaB (ΔhpaB), 85*ΔhpaBC (ΔhpaBC), 85*ΔhpaAC (ΔhpaAC), 85*ΔhpaAB (ΔhpaAB), 85*ΔhpaABC (ΔhpaABC), and 85*ΔhrcN (ΔhrcN) mutants were inoculated into leaves of susceptible ECW and AvrBs1-responsive ECW-10R pepper plants as well as into leaves of the non-host plant N. benthamiana. Leaves of ECW-10R plants were destained in ethanol 2 dpi. Photographs were taken 9 dpi. Dashed lines indicate the infiltrated leaf areas. (B) In planta growth of double and triple hpa deletion mutants in susceptible pepper plants. Strain 85* and the 85*ΔhpaB (ΔhpaB), 85*ΔhpaBC (ΔhpaBC), 85*ΔhpaABC (ΔhpaABC) and 85*ΔhrcN (ΔhrcN) mutants were inoculated at a density of 104 CFU ml−1 into leaves of susceptible pepper plants, and bacterial growth was determined as mean values from three leaf discs of three plants over a time period from 0 to 11 days. Error bars represent standard deviations. The experiment was repeated twice with similar results. The asterisks indicate significant differences from results for the wild-type strain, with a P value of <0.05 based on the results of an unpaired Student's t test.

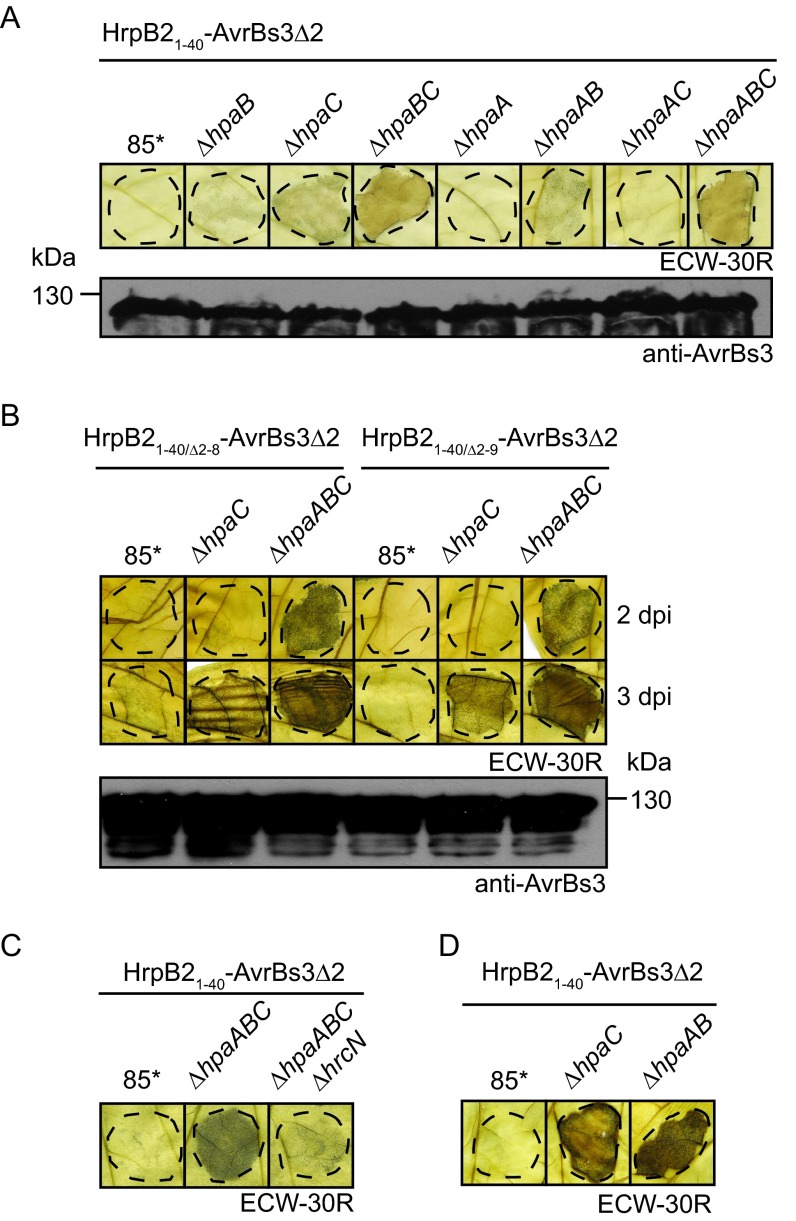

For translocation assays, double and triple hpa deletion mutants containing HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 were inoculated into leaves of AvrBs3-responsive pepper plants. Compared with the 85*ΔhpaC strain, 85*ΔhpaBC and 85*ΔhpaABC strains delivering HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 induced a stronger HR (Fig. 6A), suggesting that the T3S chaperone HpaB and possibly also HpaA are involved in the control of HrpB2 translocation. Similar findings were observed for the N-terminal deletion derivatives HrpB21–40/Δ2–8-AvrBs3Δ2 and HrpB21–40/Δ2–9-AvrBs3Δ2 (Fig. 6B). Translocation of HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 by the 85*ΔhpaABC strain was T3S dependent, because the additional deletion of the ATPase-encoding gene hrcN, which is essential for T3S, abolished HR induction (Fig. 6C). Unexpectedly, HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 also induced a weak HR when delivered by the 85*ΔhpaAB strain, suggesting that it was translocated in the presence of HpaC (Fig. 6A and D). Secretion assays revealed that HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 was detected in the culture supernatants of 85*ΔhpaC, 85*ΔhpaBC, and 85*ΔhpaABC strains, whereas secretion of HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 by the 85*ΔhpaAB strain was not detectable (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

FIG 6.

HpaA and HpaB contribute to the control of HrpB2 translocation. (A) Translocation assays with HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 in double and triple hpa deletion mutants. Strain 85* and the 85*ΔhpaB (ΔhpaB), 85*ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC), 85*ΔhpaBC (ΔhpaBC), 85*ΔhpaA (ΔhpaA), 85*ΔhpaAB (ΔhpaAB), 85*ΔhpaAC (ΔhpaAC) and 85*ΔhpaABC (ΔhpaABC) mutants containing HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 were inoculated at a bacterial density of 4 × 108 CFU ml−1 into leaves of AvrBs3-responsive ECW-30R pepper plants. For the better visualization of the HR, leaves were destained in ethanol 3 dpi. Dashed lines indicate the infiltrated areas. Phenotypes in ECW-10R pepper plants are shown in Fig. S4 in the supplemental material. Equal amounts of cell extracts (adjusted according to the optical density) were analyzed by immunoblotting using an AvrBs3-specific antiserum. (B) The N-terminal nine amino acids of HrpB2 are dispensable for translocation by the 85*ΔhpaABC strain. Strain 85* and the 85*ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC) and 85*ΔhpaABC (ΔhpaABC) mutants, containing HrpB2-AvrBs3Δ2 fusion proteins as indicated, were inoculated into pepper plants as described for panel A. Leaves were destained in ethanol 2 and 3 dpi. Equal amounts of cell extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting using AvrBs3-specific antibodies. (C) Translocation of HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 in 85*ΔhpaABC mutant is T3S dependent. Strain 85* and the 85*ΔhpaABC (ΔhpaABC) and 85*ΔhpaABCΔhrcN (ΔhpaABC ΔhrcN) mutants containing HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 were inoculated into leaves of AvrBs3-responsive ECW-30R plants. Leaves were destained in ethanol 3 dpi. (D) HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 is translocated in the absence of HpaA and HpaB. Strain 85* and the 85*ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC) and 85*ΔhpaAB (ΔhpaAB) mutants containing HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 were inoculated at a bacterial density of 8 × 108 CFU ml−1 into leaves of AvrBs3-responsive ECW-30R plants. Leaves were destained in ethanol 3 dpi.

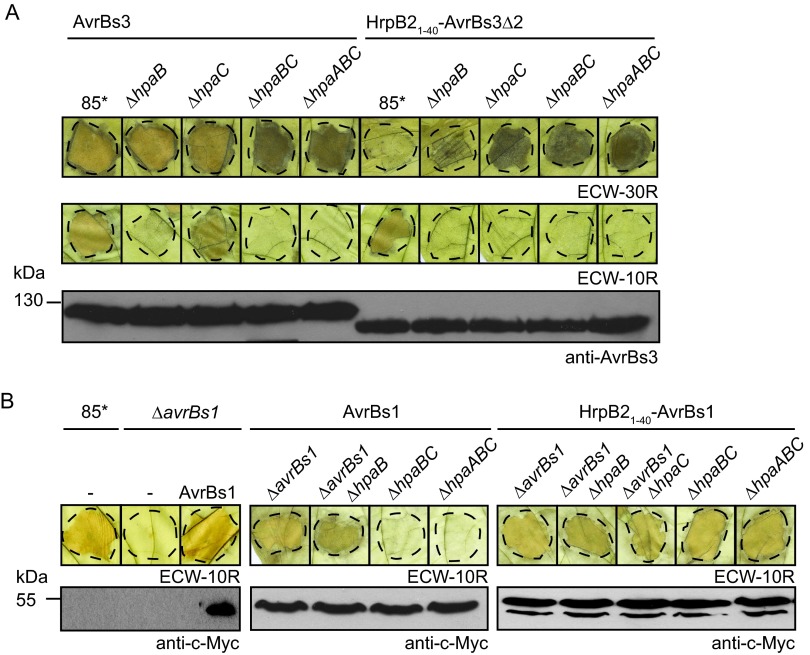

We also analyzed the translocation of the full-length AvrBs3 protein in hpa deletion mutants. For this, an expression construct encoding AvrBs3 was introduced into 85*, 85*ΔhpaB, 85*ΔhpaC, 85*ΔhpaBC, and 85*ΔhpaABC strains which lack the native avrBs3 gene. Infection assays with AvrBs3-responsive pepper plants revealed that AvrBs3 was translocated by all strains (Fig. 7A). We did not observe significant differences in HR induction by AvrBs3 and HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 when both proteins were delivered by 85*ΔhpaABC and 85-10ΔhpaABC strains (Fig. 7A; also see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). We conclude from these observations that AvrBs3 is translocated by the hpaABC mutant. This is in contrast to AvrBs1, which is not or not efficiently translocated by the 85*ΔhpaABC strain (see also below).

FIG 7.

Translocation of HrpB21–40-effector fusions by the hpaABC deletion mutant. (A) AvrBs3 is translocated by the 85*ΔhpaABC mutant. Strain 85* and the 85*ΔhpaB (ΔhpaB), 85*ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC), 85*ΔhpaBC (ΔhpaBC), and 85*ΔhpaABC (ΔhpaABC) mutants, containing AvrBs3 or HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 as indicated, were inoculated into leaves of AvrBs3-responsive ECW-30R pepper plants. For the better visualization of the HR, leaves were destained in ethanol 3 dpi. Dashed lines indicate the infiltrated areas. (B) The N-terminal 40 amino acids of HrpB2 target AvrBs1 for translocation in the hpaABC mutant. Strain 85* and the 85*ΔavrBs1 (ΔavrBs1), 85*ΔavrBs1ΔhpaB (ΔavrBs1 ΔhpaB), 85*ΔavrBs1ΔhpaC (ΔavrBs1 ΔhpaC), 85*ΔhpaBC (ΔhpaBC), and 85*ΔhpaABC (ΔhpaABC) mutants containing AvrBs1-c-Myc or HrpB21–40-AvrBs1-c-Myc as indicated were inoculated at a bacterial density of 2 × 108 CFU ml−1 into leaves of AvrBs1-responsive ECW-10R pepper plants. Leaves were destained in ethanol 2 dpi. Dashed lines indicate the infiltrated areas. Equal amounts of cell extracts (adjusted according to the optical density) were analyzed by immunoblotting using a c-Myc epitope-specific antiserum.

The hpaABC mutant translocates a HrpB21–40-AvrBs1 fusion protein.

We next investigated whether the HrpB2 T3S and translocation signal can target a full-length effector protein for translocation in the hpaABC deletion mutant. For this, we analyzed the effector protein AvrBs1, which induces the HR in AvrBs1-responsive ECW-10R pepper plants. To monitor the translocation of a fusion protein between the N-terminal 40 amino acids of HrpB2 and AvrBs1, we deleted the native avrBs1 gene from the genome of 85*, 85*ΔhpaB, and 85*ΔhpaC strains. As expected, deletion of avrBs1 in strain 85* led to a loss of HR induction in ECW-10R pepper plants (Fig. 7B). HR induction was restored by a C-terminally c-Myc epitope-tagged derivative of AvrBs1 (Fig. 7B). HrpB21–40-AvrBs1-c-Myc induced the HR in AvrBs1-responsive plants when delivered by 85*ΔavrBs1, 85*ΔavrBs1ΔhpaB, and 85*ΔavrBs1ΔhpaC strains, suggesting that it was translocated (Fig. 7B). We assume that the intrinsic effector-specific signal of AvrBs1 targets the fusion protein for translocation in the presence of HpaC (Fig. 7B). HrpB21–40-AvrBs1-c-Myc also induced the HR when delivered by 85*ΔhpaBC and 85*ΔhpaABC strains, indicating that the T3S and translocation signal of HrpB2 targets AvrBs1 for translocation in the absence of HpaA, HpaB, and HpaC (Fig. 7B). This is in contrast to AvrBs1-c-Myc, which did not induce the HR and presumably is not efficiently translocated in the absence of HpaA, HpaB, and HpaC (Fig. 7B).

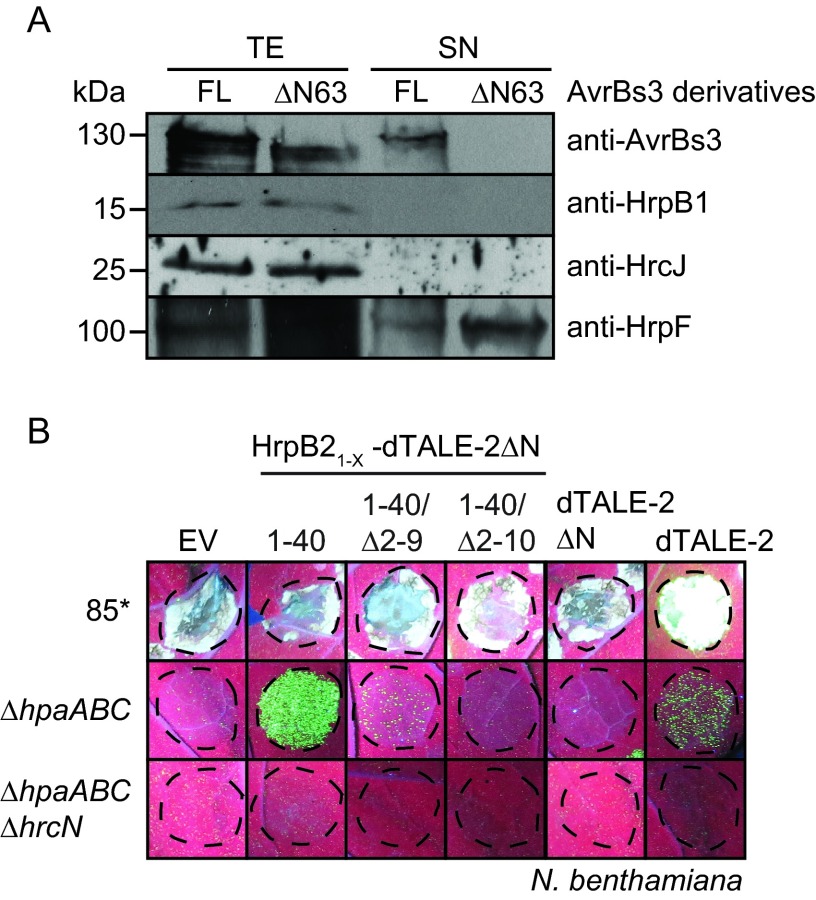

The N-terminal 40 amino acids of HrpB2 target a designer TAL effector for translocation into Nicotiana benthamiana.

We also analyzed whether the HrpB2 secretion and translocation signal targets effector proteins for translocation into cells of the non-host plant Nicotiana benthamiana. For this, we used a designer TAL effector (dTALE-2) as the reporter protein. TAL effectors contain a central repeat region with repeat-variable diresidues (RVDs), which bind to specific DNA sequences in the promoter regions of target genes (62). dTALE-2 is a derivative of the TAL effector AvrBs3 and contains modified RVDs, which were designed to bind to the DNA target sequence 5′-TCCCCGCATAGCTGAACAT-3′ (63). As a reporter system, we used transgenic N. benthamiana plants containing a stably integrated tobacco mosaic virus (TMV)-based viral vector which encodes an RdRp and GFP (50, 63). The viral vector construct was placed under the control of the alcA promoter from Aspergillus nidulans, which requires binding of the AlcR transcriptional activator for transcription activation. In transgenic N. benthamiana plants, which lack AlcR, transcription of the viral vector is induced in the presence of dTALE-2, which binds to a sequence upstream of the TATA box of the alcA promoter (63). The primary nuclear transcript is replicated in the cytosol by the RdRp, which leads to the expression of gfp from a subgenomic RNA transcript. The amplification of the viral vector in the presence of dTALE-2 results in a high-level expression of gfp. The resulting GFP fluorescence is locally restricted to infected cells because the viral vector lacks coding sequences for the movement and coat proteins, which are needed for cell-to-cell and systemic movement (50, 63).

For translocation assays, we used dTALE-2 and a deletion derivative thereof which lacks the N-terminal 64 amino acids (dTALE-2ΔN). It was shown for AvrBs3 that the N-terminal region is required for secretion (42, 64) (Fig. 8A). dTALE-2, dTALE-2ΔN, and dTALE-2ΔN fusion proteins containing amino acids 1 to 40, 10 to 40, and 11 to 40 of HrpB2, respectively, were analyzed in X. campestris pv. vesicatoria 85* and 85*ΔhpaABC strains and the 85*ΔhpaABCΔhrcN T3S-deficient strain. The delivery of dTALE-2 by strain 85* led to GFP fluorescence 3 dpi, suggesting that dTALE-2 was translocated and induced the expression of gfp (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Notably, however, strain 85* induced a necrosis in N. benthamiana leaves which interfered with the GFP fluorescence (Fig. 5A; also see Fig. S5). The induction of a necrosis reaction in N. benthamiana also was previously reported for X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strain GM98-38 (65). When delivered by the 85*ΔhpaABC strain, dTALE-2 induced a weak and spotty GFP fluorescence 8 dpi (Fig. 8B). This suggests that the translocation of dTALE-2 was significantly reduced in the 85*ΔhpaABC strain compared to that in strain 85*. The 85*ΔhpaABC strain delivering HrpB21–40-dTALE-2ΔN induced a spotty and nonconfluent fluorescence 4 dpi which increased in intensity at later time points, indicating that the fusion protein was translocated. GFP fluorescence after delivery of HrpB21–40-dTALE-2ΔN by the 85*ΔhpaABC strain was slightly increased compared to the GFP signal induced by dTALE-2 (Fig. 8B). Significantly reduced or no fluorescence was observed for HrpB21–40/Δ2–9-dTALE-2ΔN and HrpB21–40/Δ2–10-dTALE-2ΔN fusions (Fig. 8B; also see Fig. S5). Thus, amino acids 10 to 40 do not efficiently target the dTALE-2ΔN reporter for translocation in N. benthamiana. No GFP fluorescence was detected after inoculation of the 85*ΔhpaABCΔhrcN strain, which lacks the ATPase-encoding gene hrcN and therefore is deficient in T3S (Fig. 8B). All fusion proteins were detected by immunoblot analysis using an AvrBs3-specific antiserum; however, additional degradation products were present in all cases (see Fig. S5). Taken together, we conclude from these data that the N-terminal 40 amino acids of HrpB2 target dTALE-2ΔN for translocation into cells of the non-host plant N. benthamiana in the absence of HpaA, HpaB, and HpaC.

FIG 8.

hpaABC mutant delivers cargo proteins into N. benthamiana. (A) Secretion of the TAL effector AvrBs3 depends on the N-terminal 63 amino acids. X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strain 85* containing AvrBs3 (FL) and AvrBs3ΔN63 (ΔN63) as indicated was incubated in secretion medium. Total cell extracts (TE) and culture supernatants (SN) were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies specific for AvrBs3, HrpB1, HrcJ, and the secreted translocon protein HrpF. (B) The 85*ΔhpaABC mutant delivers HrpB21–40-dTALE-2ΔN into N. benthamiana. Strain 85* and the 85*ΔhpaABC (ΔhpaABC) and 85*ΔhpaABC ΔhrcN (ΔhpaABC ΔhrcN) mutants, containing the empty vector (EV), HrpB21–40-dTALE-2ΔN, HrpB21–40/Δ2–9-dTALE-2ΔN, HrpB21–40/Δ2–10-dTALE-2ΔN, dTALE-2ΔN, or dTALE-2 as indicated, were inoculated at a density of 8 × 108 CFU ml−1 into leaves of gfp-transgenic N. benthamiana plants. Photographs of GFP fluorescence were taken 8 dpi.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we localized the T3S and translocation signal of HrpB2 and analyzed its contribution to protein function and to the interaction of HrpB2 with HrcUC. The successive introduction of small deletions and the analysis of reporter fusion proteins revealed that the secretion and translocation signal of HrpB2 is located in the region spanning amino acids 10 to 40 (Fig. 1 and 3). However, not all amino acids in this region appear to be essential for the targeting of HrpB2 to the secretion apparatus, because internal deletions between amino acids 12 to 25 did not significantly interfere with the secretion and/or translocation of HrpB2 (Fig. 1 and 4). The N-terminal 40 amino acids of HrpB2 do not share homology with protein regions of known T3S substrates from X. campestris pv. vesicatoria. This is in agreement with the observed lack of sequence conservation in T3S signals. The N-terminal region of HrpB2 contains 10% leucine and 5% serine residues (compared to 6.7% leucine and 8.9% serine residues, respectively, in the rest of the protein); therefore, it does not match the criteria predicted for T3S signals, e.g., a depletion of leucine and an enrichment of serine residues (8, 9, 66–68). Notably, however, in the effector protein AvrPto from Pseudomonas syringae, the functional importance of these characteristic amino acid patterns could not be confirmed by mutational approaches, suggesting a high variability of the T3S signal and the presence of additional targeting patterns (12).

The finding that amino acids 10 to 40 of HrpB2 are sufficient for secretion and translocation of HrpB2 in the absence of HpaC suggests that HrpB2 contains one joint secretion and translocation signal which also determines the secretion specificity, i.e., the HpaC-mediated suppression of HrpB2 secretion and translocation. It is still unknown whether other T3S substrates from X. campestris pv. vesicatoria contain separate secretion and translocation signals and how the secretion specificity in hpaB or hpaC mutants is determined. We have previously shown that the N-terminal 50 and 200 amino acids of the putative translocon proteins XopA and HrpF, respectively, contain translocation signals which are suppressed by the general T3S chaperone HpaB (42). However, minimal transport signals as well as protein regions required for the HpaB-dependent translocation of XopA and HrpF have not yet been identified. To date, separate secretion and translocation signals have been described in effector proteins from the animal-pathogenic bacterium Yersinia and the plant pathogen Erwinia amylovora (69–72). In the case of the Yersinia effector protein YopE, the secretion specificity is determined by the minimal secretion signal (73). In contrast, the N-terminal minimal secretion and translocation signal of the translocon protein PopD from Pseudomonas aeruginosa is not sufficient for the secretion of PopD in the presence of calcium. It was shown that the translocon-specific secretion of PopD in the presence of calcium requires additional protein regions located next to the T3S signal and the C terminus (16). Similarly, the secretion and translocation signal in the N-terminal 20 amino acids of translocon proteins from enteropathogenic E. coli is not sufficient to mediate translocon-specific secretion in mutant strains which lack the control proteins SepD and SepL (74–78). Therefore, it was suggested that T3S is controlled by composite signals, which are involved in a multistep recognition process (68, 74, 75). Notably, however, this model does not appear to apply to HrpB2, suggesting that the presence of additive export signals in T3S substrates is not a general rule.

Our complementation studies revealed that the deletion of amino acids 2 to 9, which are dispensable for HrpB2 secretion, does not interfere with HrpB2 function. In contrast, HrpB2Δ2–10, which lacks a functional T3S signal, failed to complement the hrpB2 mutant phenotype, suggesting that the T3S signal is essential for HrpB2 function (Fig. 1). We assume that the T3S signal of HrpB2 is required for its recognition by components of the T3S system and allows the subsequent entry of HrpB2 into the inner secretion channel of the T3S system. Given the predicted role of HrpB2 as an inner rod protein, the entry of HrpB2 into the secretion apparatus presumably is required for its function. The results of interaction studies revealed that amino acids 10 to 40 of HrpB2 are essential and sufficient for the interaction of HrpB2 with HrcUC (Fig. 2). In agreement with the predicted role of the T3S signal in substrate recognition, it was previously reported that the T3S signal of the effector protein YopR from Yersinia enterocolitica contributes to the interaction of YopR with the T3S ATPase YscN (79). In contrast, however, in the case of the secreted filament protein EspA from enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), the interaction with the T3S-associated ATPase depends on the binding of the T3S chaperone CesAB to EspA and appears to be independent of the T3S signal of EspA (24). Similarly, our previous interaction studies revealed that the N-terminal region of the TAL effector AvrBs3 from X. campestris pv. vesicatoria, which contains the T3S and translocation signal, is dispensable for the interaction of AvrBs3 with the putative C ring component HrcQ and the IM protein HrcV (44, 45). HrcV and HrcQ are putative docking sites for T3S substrates, yet it cannot be excluded that additional components of the T3S system, such as the ATPase HrcN or HrcUC, are involved in the recognition of T3S signals. However, previous interaction studies did not reveal an interaction between HrcUC and effector proteins (38).

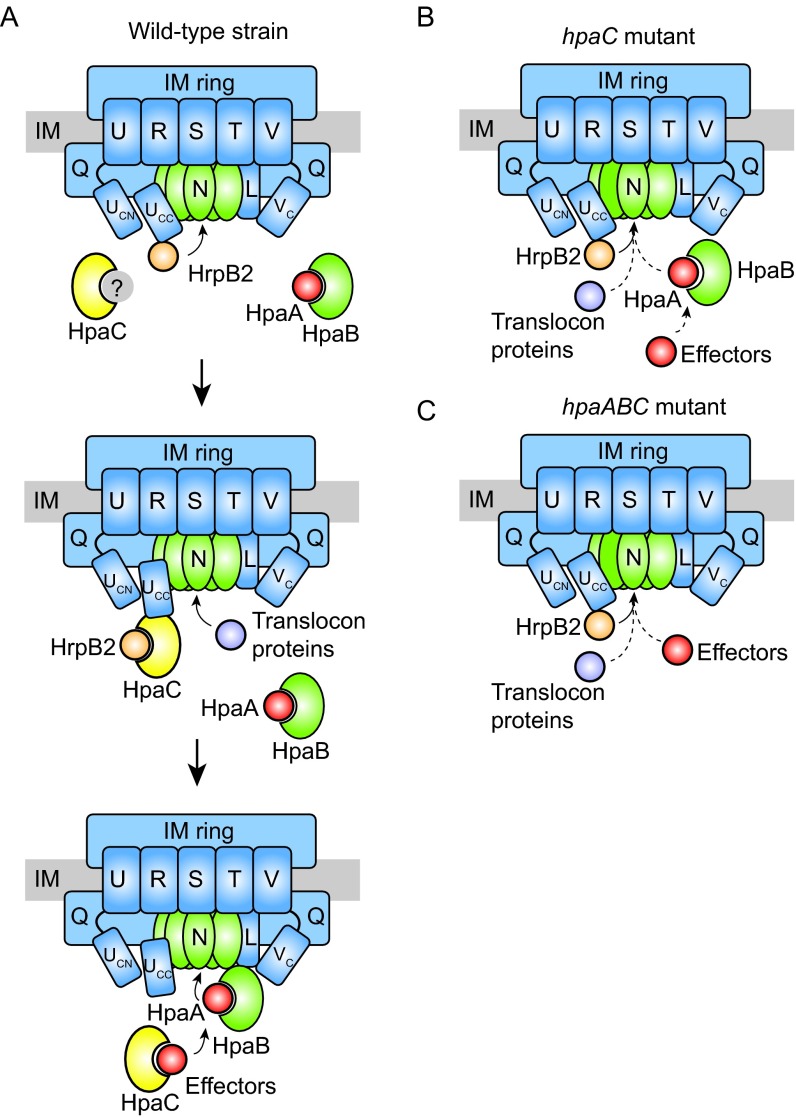

According to our current model, secretion of HrpB2 depends on the recognition of the HrpB2 T3S signal by HrcUC (Fig. 9). As described previously, a conformational change in HrcUC induced by the T3S4 protein HpaC likely suppresses the secretion and translocation of HrpB2 (38, 40, 41) (Fig. 9). The present study suggests that the translocation of HrpB2 is also controlled by the general T3S chaperone HpaB and its secreted regulator, HpaA, which are both essential for the efficient secretion of effector proteins (Fig. 6 and 7). It is possible that the reduced effector protein secretion in the absence of HpaB and/or HpaA indirectly promotes the secretion and translocation of components of the T3S system, as was previously proposed for the translocation of the putative translocon proteins HrpF and XopA in the hpaB deletion mutant (42). In agreement with this hypothesis, deletion of hpaB in the hpaC and hpaAC mutant led to significantly enhanced translocation of HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2. As expected, HrpB21–40-AvrBs3Δ2 was not translocated in the hpaAC deletion mutant because HpaB presumably blocks the T3S system in the absence of HpaA (43 and described above). Given the observed inhibitory influence of HpaA, HpaB, and HpaC on the translocation of HrpB2, we performed all further translocation assays using the nonpathogenic hpaABC triple deletion mutant. Notably, the results of the infection assays with resistant pepper plants suggest that the hpaABC deletion mutant translocates AvrBs3 but not AvrBs1 (Fig. 7). It remains to be investigated whether the observed differences in the translocation of AvrBs3 and AvrBs1 are caused by a more sensitive detection of AvrBs3 than AvrBs1 in corresponding resistant plants. It was previously reported that AvrBs3 efficiently induces the resistance gene Bs3, which triggers the AvrBs3-responsive HR (62). In future experiments, we will use AvrBs3Δ2 as a reporter to investigate the translocation of additional effectors in the hpaABC deletion mutant. Furthermore, we will also test whether AvrBs3 contains a translocation signal which specifically promotes its translocation in the absence of HpaA, HpaB, and HpaC.

FIG 9.

Model of the HpaC/HrcU-mediated T3S substrate specificity switch in X. campestris pv. vesicatoria. (A) HpaA, HpaB, and HpaC control the secretion of HrpB2, translocon, and effector proteins. During the early stages of the T3S process, the cytoplasmic domain of HrcU is proteolytically cleaved and the C-terminal cleavage product of HrcU (HrcUCC) interacts with the early T3S substrate HrpB2. The interaction between HrcUCC and HrpB2 is presumably essential for HrpB2 secretion. The secretion of HrpB2 is subsequently suppressed by the T3S4 protein HpaC, which interacts with HrcUCC and HrpB2. It is unknown whether HpaC is inactivated by an unknown protein (indicated in gray) during the early stages of the secretion process to allow secretion of HrpB2. HpaC presumably induces a conformational change in HrcUCC, which might interfere with the docking of HrpB2 to HrcUCC and switches the T3S substrate specificity from secretion of HrpB2 to the secretion of translocon and effector proteins. The efficient secretion of effector proteins requires HpaC and the T3S chaperone HpaB, which both interact with effectors. HpaB presumably is inactivated by binding of the control protein HpaA during the assembly of the T3S system. Secretion of HpaA liberates HpaB and thus activates the secretion of effector proteins. IM, inner membrane. Letters refer to conserved components of the T3S system, i.e., HrcU (U), HrcR (R), HrcS (S), HrcT (T), HrcV (V), HrcVC (VC), HrcQ (Q), HrcN (N), and HrcL (L). The C-terminal domain of HrcU is cleaved at a conserved NPTH amino acid motif, resulting in the cytoplasmic HrcUCN (UCN) and HrcUCC (UCC) domains. (B) Secretion in the hpaC deletion mutant. The absence of HpaC allows the constitutive secretion of HrpB2 but interferes with the efficient secretion of translocon and effector proteins. (C) Secretion in the hpaABC deletion mutant. In the absence of HpaA, HpaB, and HpaC, only HrpB2 is efficiently secreted and translocated. Efficient secretion of translocon and effector proteins is abolished in the absence of HpaA, HpaB, and HpaC.

In addition to AvrBs3Δ2 reporter fusion proteins, we analyzed fusion proteins between the N-terminal 40 amino acids of HrpB2 and the effector protein AvrBs1. In contrast to AvrBs1, the HrpB21–40-AvrBs1 fusion protein was efficiently translocated by the hpaABC deletion mutant (Fig. 7). This suggests that the HrpB2 signal targets AvrBs1 for translocation in the absence of HpaA, HpaB, and HpaC. The HrpB2 T3S and translocation signal can also be used to deliver proteins into N. benthamiana cells, as was shown by the analysis of TAL reporter fusion proteins in the hpaABC mutant (Fig. 8). In the field of plant pathology, protein transport into plant cells is of special interest with regard to the functional characterization of bacterial type III effector proteins. Given that T3S systems of bacterial plant pathogens usually translocate a large set of effectors with redundant functions, the delivery of individual effectors by bacterial strains, which are either deprived of effectors or are deficient in the translocation of their native effector protein repertoire, as is the case for the hpaABC mutant, will help to elucidate effector-triggered modifications of host cellular pathways.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to U. Bonas for comments on the manuscript and for providing the AvrBs3-specific antibody, to T. Schreiber for discussing unpublished data on AvrBs3, to C. Lorenz and K. Schlien for generating constructs pBhrpB21–20-356, pBhrpB21–25-356, pBhrpB21–30-356, and pBhrpB21–40-356, and to M. Jordan for technical assistance.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (BU2145/1-2, BU2145/5-1, and CRC 648 [“Molecular mechanisms of information processing in plants”]) to D.B.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00537-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.He SY, Nomura K, Whittam TS. 2004. Type III protein secretion mechanism in mammalian and plant pathogens. Biochim Biophys Acta 1694:181–206. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Büttner D. 2012. Protein export according to schedule—architecture, assembly and regulation of type III secretion systems from plant and animal pathogenic bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 76:262–310. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05017-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galan JE, Lara-Tejero M, Marlovits TC, Wagner S. 2014. Bacterial type III secretion systems: specialized nanomachines for protein delivery into target cells. Annu Rev Microbiol 68:415–438. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bogdanove A, Beer SV, Bonas U, Boucher CA, Collmer A, Coplin DL, Cornelis GR, Huang H-C, Hutcheson SW, Panopoulos NJ, Van Gijsegem F. 1996. Unified nomenclature for broadly conserved hrp genes of phytopathogenic bacteria. Mol Microbiol 20:681–683. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5731077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee PC, Rietsch A. 2015. Fueling type III secretion. Trends Microbiol 23:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattei PJ, Faudry E, Job V, Izore T, Attree I, Dessen A. 2011. Membrane targeting and pore formation by the type III secretion system translocon. FEBS J 278:414–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchko GW, Niemann G, Baker ES, Belov ME, Smith RD, Heffron F, Adkins JN, McDermott JE. 2010. A multi-pronged search for a common structural motif in the secretion signal of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium type III effector proteins. Mol Biosyst 6:2448–2458. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00097c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Sun M, Bao H, White AP. 2013. T3_MM: a Markov model effectively classifies bacterial type III secretion signals. PLoS One 8:e58173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnold R, Brandmaier S, Kleine F, Tischler P, Heinz E, Behrens S, Niinikoski A, Mewes HW, Horn M, Rattei T. 2009. Sequence-based prediction of type III secreted proteins. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000376. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Löwer M, Schneider G. 2009. Prediction of type III secretion signals in genomes of Gram-negative bacteria. PLoS One 4:e5917. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samudrala R, Heffron F, McDermott JE. 2009. Accurate prediction of secreted substrates and identification of a conserved putative secretion signal for type III secretion systems. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000375. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schechter LM, Valenta JC, Schneider DJ, Collmer A, Sakk E. 2012. Functional and computational analysis of amino acid patterns predictive of type III secretion system substrates in Pseudomonas syringae. PLoS One 7:e36038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson DM, Schneewind O. 1997. A mRNA signal for the type III secretion of Yop proteins by Yersinia enterocolitica. Science 278:1140–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Majander K, Anton L, Antikainen J, Lang H, Brummer M, Korhonen TK, Westerlund-Wikstrom B. 2005. Extracellular secretion of polypeptides using a modified Escherichia coli flagellar secretion apparatus. Nat Biotechnol 23:475–481. doi: 10.1038/nbt1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niemann GS, Brown RN, Mushamiri IT, Nguyen NT, Taiwo R, Stufkens A, Smith RD, Adkins JN, McDermott JE, Heffron F. 2013. RNA type III secretion signals that require Hfq. J Bacteriol 195:2119–2125. doi: 10.1128/JB.00024-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomalka AG, Stopford CM, Lee PC, Rietsch A. 2012. A translocator-specific export signal establishes the translocator-effector secretion hierarchy that is important for type III secretion system function. Mol Microbiol 86:1464–1481. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allen-Vercoe E, Toh MC, Waddell B, Ho H, DeVinney R. 2005. A carboxy-terminal domain of Tir from enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 (EHEC O157:H7) required for efficient type III secretion. FEMS Microbiol Lett 243:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karlinsey JE, Lonner J, Brown KL, Hughes KT. 2000. Translation/secretion coupling by type III secretion systems. Cell 102:487–497. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singer HM, Erhardt M, Hughes KT. 2014. Comparative analysis of the secretion capability of early and late flagellar type III secretion substrates. Mol Microbiol 93:505–520. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enninga J, Mounier J, Sansonetti P, Tran Van Nhieu G. 2005. Secretion of type III effectors into host cells in real time. Nat Methods 2:959–965. doi: 10.1038/nmeth804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schlumberger MC, Muller AJ, Ehrbar K, Winnen B, Duss I, Stecher B, Hardt WD. 2005. Real-time imaging of type III secretion: Salmonella SipA injection into host cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:12548–12553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503407102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Engelenburg SB, Palmer AE. 2008. Quantification of real-time Salmonella effector type III secretion kinetics reveals differential secretion rates for SopE2 and SptP. Chem Biol 15:619–628. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lorenz C, Büttner D. 2009. Functional characterization of the type III secretion ATPase HrcN from the plant pathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. J Bacteriol 191:1414–1428. doi: 10.1128/JB.01446-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen L, Ai X, Portaliou AG, Minetti CA, Remeta DP, Economou A, Kalodimos CG. 2013. Substrate-activated conformational switch on chaperones encodes a targeting signal in type III secretion. Cell Rep 3:709–715. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lara-Tejero M, Kato J, Wagner S, Liu X, Galan JE. 2011. A sorting platform determines the order of protein secretion in bacterial type III systems. Science 331:1188–1191. doi: 10.1126/science.1201476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allison SE, Tuinema BR, Everson ES, Sugiman-Marangos S, Zhang K, Junop MS, Coombes BK. 2014. Identification of the docking site between a type III secretion system ATPase and a chaperone for effector cargo. J Biol Chem 289:23734–23744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.578476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper CA, Zhang K, Andres SN, Fang Y, Kaniuk NA, Hannemann M, Brumell JH, Foster LJ, Junop MS, Coombes BK. 2010. Structural and biochemical characterization of SrcA, a multi-cargo type III secretion chaperone in Salmonella required for pathogenic association with a host. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000751. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas NA, Deng W, Puente JL, Frey EA, Yip CK, Strynadka NC, Finlay BB. 2005. CesT is a multi-effector chaperone and recruitment factor required for the efficient type III secretion of both LEE- and non-LEE-encoded effectors of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 57:1762–1779. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rossier O, Van den Ackerveken G, Bonas U. 2000. HrpB2 and HrpF from Xanthomonas are type III-secreted proteins and essential for pathogenicity and recognition by the host plant. Mol Microbiol 38:828–838. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonas U, Schulte R, Fenselau S, Minsavage GV, Staskawicz BJ, Stall RE. 1991. Isolation of a gene-cluster from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria that determines pathogenicity and the hypersensitive response on pepper and tomato. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 4:81–88. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-4-081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wengelnik K, Bonas U. 1996. HrpXv, an AraC-type regulator, activates expression of five of the six loci in the hrp cluster of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. J Bacteriol 178:3462–3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wengelnik K, Van den Ackerveken G, Bonas U. 1996. HrpG, a key hrp regulatory protein of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria is homologous to two-component response regulators. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 9:704–712. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-9-0704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartmann N, Schulz S, Lorenz C, Fraas S, Hause G, Büttner D. 2012. Characterization of HrpB2 from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria identifies protein regions that are essential for type III secretion pilus formation. Microbiology 158:1334–1349. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.057604-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weber E, Ojanen-Reuhs T, Huguet E, Hause G, Romantschuk M, Korhonen TK, Bonas U, Koebnik R. 2005. The type III-dependent Hrp pilus is required for productive interaction of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria with pepper host plants. J Bacteriol 187:2458–2468. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.7.2458-2468.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sal-Man N, Deng W, Finlay BB. 2012. EscI: a crucial component of the type III secretion system forms the inner rod structure in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Biochem J 442:119–125. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wood S, Jin J, Lloyd SA. 2008. YscP and YscU switch the substrate specificity of the Yersinia type III secretion system by regulating export of the inner rod protein YscI. J Bacteriol 190:4252–4262. doi: 10.1128/JB.00328-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lefebre MD, Galan JE. 2014. The inner rod protein controls substrate switching and needle length in a Salmonella type III secretion system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:817–822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319698111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]