Abstract

Background

The T-box family transcription-factor gene, Brachyury, has two expression domains with discrete functions during animal embryogenesis. The primary domain, associated with the blastopore, is shared by most metazoans, while the secondary domain, involved in the notochord, is specific to chordates. In most animals, Brachyury is present in a single copy, but in cephalochordates, the most basal of the chordates, the gene is present in two copies, suggesting allotment of the two domains to each of the duplicates.

Results

In order to clarify whether Brachyury duplication occurred in the common ancestor of chordates after which one of duplicates was lost in the urochordate and vertebrate lineages, we estimated phylogenetic relationships of Brachyury genes and examined the synteny of a Brachyury-containing genomic region of deuterostomes with decoded genomes. The monophyletic origin of tandemly arranged Brachyury genes of cephalochordates indicates that the tandem duplication occurred in the cephalochordate lineage, but not in the chordate ancestor.

Conclusions

Our results thus suggest that, in the common ancestor of chordates, a single copy of Brachyury acquired two expression domains and that the duplication was not involved in the acquisition of the notochord. However, in relation to regulatory mechanisms, both possibilities—namely a single copy with two domains and two copies with different domains—should be considered in future studies of Brachyury.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s40851-017-0064-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Brachyury, Primary and secondary expression domains, Blastopore, Notochord, Gene duplication, Chordate evolution

Background

We are interested in genetic mechanisms involved in the origins and evolution of chordates [1]. Chordates comprise three taxa, cephalochordates, urochordates or tunicates, and vertebrates [2]. These are thought to have originated from a common ancestor of the deuterostomes, together with ambulacrarians, a clade containing echinoderms and hemichordates. The organ that best characterizes chordates is the notochord, an organ that supports the beating of the muscular tail of fish-like larvae or adults [1, 3, 4]. The T-box family transcription-factor gene, Brachyury, plays an essential role in notochord formation [5]. In ascidians (urochordates), for example, Brachyury is expressed exclusively in primordial embryonic notochord cells [6, 7]. Loss of Brachyury function results in the failure of notochord formation, while its ectopic expression induces endoderm cells to become notochord cells [8, 9].

Interestingly, Brachyury is not specific to chordates, but is present in most metazoans, including non-chordate deuterostomes [5, 10]. Beside paralogs derived from ancient whole genome duplication (referred to as “ohnologs”), Brachyury is usually present as a single copy, with some exceptions (Hydra [11], calcisponge [12], and cephalochordates (see below)), and is expressed around the blastopore during gastrulation. A recent study by our group using coral embryos demonstrated that the evolutionarily conserved function of Brachyury is associated with formation of blastopore-derived organs, such as the pharynx of coral embryos [13]. In non-chordate deuterostomes, ambulacrarians, Brachyury is expressed in the archenteron invagination region in early gastrulae and in the stomodeum invagination region in later stage embryos [14, 15]. Although an overexpression experiment with sea urchin Brachyury suggested its role in gastrulation [16], the developmental role of ambulacrarian Brachyury remains to be determined.

We proposed an evolutionary scenario for Brachyury emphasizing its primary and secondary expression domains and functions [5]. Namely, ambulacrarians require Brachyury in its primary domain of expression and function associated with the blastopore (PEF), while chordates employ the gene, not only for PEF, but also for the secondary domain of expression and function associated with the notochord (SEF). In urochordates, the PEF was likely lost due to the precocious mode of embryogenesis [1, 5]. For the past decade, evolutionary developmental biologists have been asking how the chordate ancestor acquired the Brachyury SEF. Answering this question is critical to our understanding of genetic and molecular mechanisms involved in the origins of chordates. Genomes of the cephalochordates, Branchiostoma floridae and B. belcheri, each contain a set of duplicated Brachyury, Amphi-Bra1 and Amphi-Bra2 [17, 18]. These duplicated genes have both PEF and SEF, but the expression domains of each have not been determined [17, 19]. In contrast, urochordates have only a single copy [20]. Most vertebrates also have a single copy of Brachyury/T, although they have variable numbers of T ohnologs, which arose from the two rounds of genome-wide gene duplication (2R-GWGD) that occurred in this lineage [21, 22]. In mice, only a T gene exhibits PEF and SEF during early embryogenesis [22].

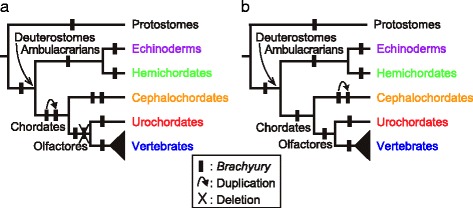

The occurrence of two domains of Brachyury expression and function may be explained by one of two alternative evolutionary scenarios (Fig. 1). In scenario 1, Brachyury was present as a single copy in deuterostome ancestors, while it became duplicated in an ancestor of chordates, such that the original gene retained PEF and its newly formed counterpart obtained SEF (Fig. 1a). The cephalochordate lineage retained this arrangement, whereas the urochordate and vertebrate lineages lost one of duplicates. In scenario 2 (Fig. 1b), chordates retained a single copy of Brachyury as did the non-chordate invertebrates. Duplication occurred in the lineage leading to cephalochordates, but not in the lineage leading to olfactores (urochordates + vertebrates). Evolution of vertebrate T-box family genes seems to have been complicated by the 2R-GWGD, and vertebrate Brachyury/T needs to be examined more carefully in the future (Yasuoka et al., in preparation).

Fig. 1.

Two alternative evolutionary scenarios for Brachyury in relation to gene duplication along with diversification of five deuterostome lineages. a In the first scenario, Brachyury duplicated in a common ancestor of chordates, with an original gene copy retaining the primary expression-function (PEF) while the duplicate developed the secondary expression-function (SEF). The cephalochordate lineage retains this feature while the urochordate and vertebrate lineages lost one of duplicates in their last common ancestor. Brachyury evolution in vertebrates is complex, due to the 2R-GWGD that occurred in this lineage. b In the second scenario, chordates maintained a single-copy of Brachyury, just as non-chordate deuterostomes did. Duplication occurred only in the lineage leading to cephalochordates, but not in lineages leading to urochordates and vertebrates

In 2015, the genomes of two hemichordate species, an indirectly developing acorn worm, Ptychodera lava, and a directly developing acorn worm, Saccoglossus kowalevskii, were decoded [23]. Genomes of animals belonging to each of the four other phyla were already decoded prior to 2014; echinoderm sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus; [24]) and starfish (Acanthaster planci [25]), cephalochordate amphioxus (Branchiostoma floridae [26] and Branchiostoma belcheri [27]), urochordates (e.g., Ciona intestinalis [20] and Oikopleura dioica [28]) and vertebrates (e.g., Homo sapiens [29]). We obtained genomic information for all five phyla of deuterostomes, enabling us to examine which of the two scenarios outlined above better explains the genetic and molecular evolution of Brachyury in relation to chordate origins.

Methods

Gene trees were estimated with an analytical pipeline implementing BLAST search and the maximum likelihood method (modified from Inoue et al. [30]).

BLAST search

Human and lancelet protein-coding sequences (amino acids) were used as queries for BLASTP search [31] against all protein-coding sequences in 18 selected animal genomes (Table 1). The resulting BLAST top 20 hits were screened using an E-value cutoff of <10−3 [32]. Where transcript variants existed for a single locus, only the longest sequence was used in the present analysis.

Table 1.

List of bilaterian species with decoded genomes used in this study

| Species | Brachyury genes | |

|---|---|---|

| Gene name | Gene/Protein ID | |

| Protostomia | ||

| Ecdysozoa | ||

| Drosophila melanogaster a | brachyenteron | FBpp0304380 |

| Caenorhabditis elegans a | — | — |

| Lophotrochozoa | ||

| Lingula anatina a | brachyury | g6294 |

| Octopus bimaculoides a | brachyury | Ocbimv22020340m.p |

| Lottia gigantea a | brachyury | LotgiP154800 |

| Crassostrea gigas a | brachyury | EKC28765 |

| Deuterostomia | ||

| Ambulacraria | ||

| Hemichordata | ||

| Ptychodera flava b | brachyury | g18670 |

| Saccoglossus b | brachyury | Sakowv30011577 |

| kowalevskii | ||

| Echinodermata | ||

| Strongylocentrotus | brachyury | SPU_013015 |

| purpuratus a | ||

| Acanthaster planci c | brachyury | oki15-190 |

| Chordata | ||

| Cephalochordata | ||

| Branchiostoma floridae d | Amphi-Bra1 | 279431 |

| Amphi-Bra2 | 121413 | |

| Branchiostoma belcheri e | Amphi-Bra1 | 102780R |

| Amphi-Bra2 | 102770 F | |

| Urochordata | ||

| Oikopleura dioica f | brachyury | GSOIDT00000279001 |

| Botryllus schlosseri g | brachyury | g63408 |

| Ciona intestinalis h | brachyury | ENSCINP00000001477 |

| Ciona savignyi h | brachyury | ENSCSAVP00000003798 |

| Vertebrata | ||

| Gallus gallus h | brachyury/T | ENSGALP00000018703 |

| tbx19 | ENSGALP00000024551 | |

| Homo sapiens h | brachyury/T | ENSP00000296946 |

| TBX19 | ENSP00000356795 | |

Alignment

The sequences of proteins obtained by the BLASTP search were aligned using MAFFT [33]. Multiple sequence alignments were trimmed by removing poorly aligned regions using TRIMAL 1.2 [34] with option “gappyout.” Corresponding cDNA sequences were forced onto the amino acid alignment using PAL2NAL [35] to generate nucleotide alignments for later comparative analysis. Each gene sequence was checked, and removed from the alignment as spurious BLAST hits if the sequence was shorter than 55% of the length of the query sequence in the unambiguously aligned sites.

Gene tree search

Phylogenetic analyses were conducted by the maximum likelihood method aligned with bootstrap analysis based upon 100 replicates. The first and second codon positions were used for DNA analysis. The analysis was performed by RAxML 8.2.4 [36], which invokes a rapid bootstrap analysis and search for the best scoring ML tree. The GTRGAMMA (general time-reversible [37] with the gamma [38]) and the PROTGAMMAWAGF (WAG [39] with gamma and empirical base frequencies) models were used for DNA and amino acid analyses, respectively. The synteny of a Brachyury-containing genomic region was assessed by identifying human/Drosophila ortholog of each neighboring gene by estimating each gene tree via our analytical pipeline.

Results

We examined Brachyury of representative protostomes and deuterostomes, the genomes of which have been decoded (Table 1, with Brachyury gene/protein ID and information from the genomes). Phylogenetic relationships of deuterostome species are based on previous studies (e.g., [23]).

Copy number of Brachyury in deuterostomes and the chordate ancestor

Molecular cloning of mouse Brachyury was followed by identifying its orthologs in various metazoans (reviewed by [5, 40]). In addition, cloning of other T-box-containing transcription factor genes, including T-brain, Tbx1, Tbox2, and Tbx6, shows that they form a family called the T-box family (e.g., [21]). Although Brachyury has been identified and characterized in each bilaterian with a decoded genome, we examined Brachyury copy numbers in 18 species, including six protostomes and 12 deuterostomes (Table 1). To evaluate the two scenarios (Fig. 1), we did not include ohnologs in vertebrates as the copy number of Brachyury because that duplication is not associated with the acquisition of SEF.

To this end, we first carefully identified all T-box containing genes from the decoded genomes. In order to identify a candidate query sequence from non-vertebrate chordate lineages, using the human Brachyury amino acid sequence as a query, phylogenetic relationships were roughly estimated to delineate a clade comprising the Brachyury subfamily. Using queries of human and cephalochordate Brachyury amino acid sequences (Additional file 1), we next searched for the Brachyury gene in selected bilaterian genomes by estimating phylogenetic relationships (Additional file 2). Although no ortholog was found in the present genome assembly of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans, a single copy of Brachyury was found in each of the other bilaterians in both resultant trees based on nucleotide and amino acid datasets. An exception was that lancelets (cephalochordates) possessed two copies in their genome, as shown previously [17, 18].

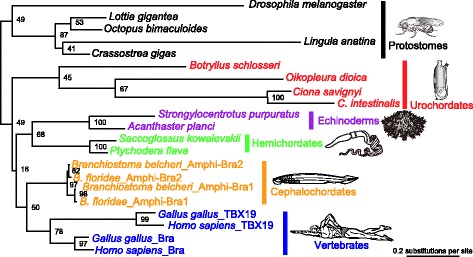

In order to estimate the copy number of Brachyury in the chordate ancestor, we reconstructed phylogenetic relationships of Brachyury using only Brachyury gene sequences (Additional file 3) selected from the estimated tree of T-box containing genes (Additional file 2). Estimated gene trees based on the comparison of nuclear (Fig. 2) and amino acid (Additional file 4) sequences produced the same deuterostome relationships, except for the positions of the urochordate, Botryllus schlosseri and a clade consisting of the remaining urochordates. For subsequent discussion, we used the tree obtained from DNA analysis because of the longer sequences. The Brachyury tree (Fig. 2) differed from the species tree (e.g., [23]) in that, in the Brachyury tree, urochordate genes formed a sister clade with all remaining deuterostome genes. This may be the result of a faster evolutionary rate of urochordate proteins than in other deuterostome taxa. Our results (Fig. 2) indicate that, with bootstrap support of 97%, Amphi-Bra1 and Amphi-Bra2 of the two species of cephalochordates forms a monophyletic group, consistent with our previous study [19].

Fig. 2.

Molecular phylogeny of Brachyury family members. The tree was estimated based on a DNA dataset comprising 872 unambiguously aligned sites (excluding 3rd codon positions) of the sequences selected from the estimated gene tree of T-box family members (Additional file 2). Numbers at nodes are bootstrap probabilities obtained for 100 replicates. Because base-pair change is apparently faster in urochordates than in other deuterostomes, urochordate Brachyury forms a clade with that of other deuterostomes. It should be noted that the two species of cephalochordate each have two copies of Brachyury

Given that cephalochordates are the only deuterostome taxon with the duplicated state of Brachyury, and that the two copies form a monophyletic clade (Fig. 2), it is highly likely that the duplication of Brachyury was specific to the cephalochordate lineage, and did not occur in the chordate ancestor. Namely Brachyury was present in a single copy in the chordate ancestor. Therefore, our results support the second of the two scenarios described above (Fig. 1b). In vertebrates (chicken and human, here), Brachyury/T forms a clade while Tbx19 forms another clade (Fig. 2). This suggests that 2R-GWGD resulted in divergence of the ancestral Brachyury into a clade including Brachyury or Tbx19.

Genomic organization of Brachyury in deuterostomes

Next, to gain a better understanding of the evolutionary changes in the genetic and genomic organization of Brachyury in relation to chordate evolution, we examined the synteny of genes in Brachyury-containing genomic regions, especially in deuterostome taxa. Although global synteny analyses have shown comparable and conserved synteny between cephalochordate and vertebrate genomes [26] and between hemichordate and cephalochordate genomes [23], no detailed analyses were carried out on genomic regions that contain Brachyury.

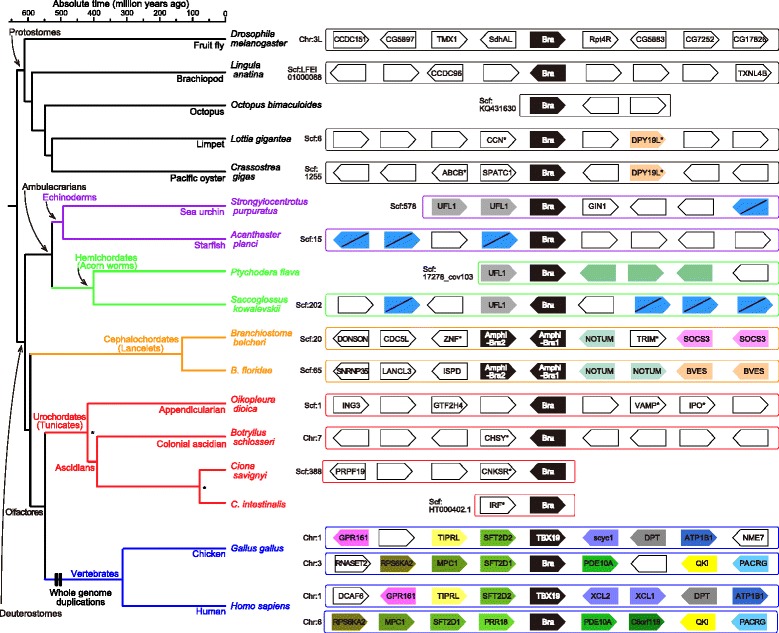

In the genomes of two cephalochordate species, B. floridae and B. belcheri, the two Brachyury were tandemly aligned (Fig. 3). In both genomes, although a neighboring NOTUM-like gene is present syntenically, synteny of neighboring genes is limited to the four genes. This suggests that the two copies of Brachyury arose from a tandem duplication, not from an ancient segmental duplication.

Fig. 3.

A schematic comparing the genomic organization of Brachyury and its neighboring genes within scaffolds/chromosomes. Presence and transcriptional direction of the genes are shown with boxes. Boxes of the same color or protein names show orthologous relationships (or paralogous within a given species) while white boxes show no orthologous relationship to any known proteins. Note that genes indicated in blue boxes with black slanting lines share domains with a comparable or similar DNA sequence. Divergence times are based on TIMETREE database [42], except for nodes with asterisks (no estimate)

Beside the trait of tandem duplication of cephalochordate Brachyury, our synteny analysis characterized conserved synteny around Brachyury of major deuterostome lineages (Fig. 3). A global view of synteny indicates that it is comparable among ambulacrarian species, because genes with comparable sequences were found in echinoderms and an acorn worm. On the contrary, no conserved synteny was found among four species of tunicates. Although the synteny analysis among vertebrate genomes was complicated by 2R-GWGD, it is evident that there are no scaffolds with duplicated Brachyury/T or its ohnolog, Tbx19, in chicken or human genomes. Detailed synteny of the Brachyury-containing genomic region is discussed in Additional file 5.

Discussion

Brachyury is thought to be the most ancient T-box family member (e.g., [21, 22]). It has been speculated that during their histories of over 500 million years, each of the five deuterostome taxa altered the genetic and genomic constitution of Brachyury from its original forms, rending analysis of the present question of Brachyury evolution more difficult than that of more recently evolved genes. Nevertheless, the tandem duplicated state of Brachyury is found only in cephalochordates. Recently, another example of tandem duplication of chordate Brachyury has been reported in an amphibian, Xenopus tropicalis [41]. It thus appears likely that cases of Brachyury duplication [1] are exceptional. As previously described, Brachyury has two domains of expression and function. The primary domain of expression is in the blastopore during gastrulation (PEF), which is shared by all metazoans [5, 13]. The secondary domain is associated with the notochord (SEF), and is specific to chordates. It is tempting to speculate that one is the original Brachyury gene with its original function and the other is a new copy with a secondary function, and that the duplication occurred very early in chordate evolution. However, as shown in the present study, Brachyury was present as a single copy in the common ancestor of chordates and a single copy of Brachyury acquired the secondary function, SEF, in the chordate ancestor.

Conclusions

The presence of a single copy of Brachyury in the chordate ancestor indicates that the gene duplication was not associated with the acquisition of SEF leading to the development of the notochord. Considering that copy numbers of Brachyury vary between cephalochordates and other deuterostome lineages, the question of regulatory mechanisms still remains. Intensive analyses have been carried out to elucidate 5′ upstream sequences or modules that regulate PEF and SEF, respectively [1]. Therefore, we have to keep the two cases, namely a single copy with two domains and two copies with different domains, in mind for future studies of Brachyury in relation to regulatory mechanisms.

Additional files

cDNA sequence alignment of T-box family members analyzed in the phylogenetic analysis (Additional file 2). Identity to one of the query gene sequences (underlined) is denoted by dots. Only unambiguously aligned sites are presented (525 out of 16,677 sites). Insertions/deletions of specific nucleotides are indicated by dashes. (PDF 9491 kb)

Molecular phylogenies of T-box family members based on a DNA dataset comprising 350 unambiguously aligned sites (excluding 3rd codon positions) (a) and based on an amino acid dataset comprising 175 sites (b). In both trees, the Brachyury family consistently forms a distinct clade among T-box family members. The resulting tree obtained from reanalysis using only this portion is shown in Fig. 2 and Additional file 4. Query sequences used for the BLAST search are marked with black dots. (PDF 551 kb)

cDNA sequence alignment of Brachyury genes (2625 sites in total) analyzed in the phylogenetic analyses (Fig. 2 and Additional file 4). The alignment was constructed using the selected gene sequences from the estimated tree of T-box-containing genes (Additional file 2). Unambiguously aligned sites indicated by a 1 (on the top of the sequences, 1308 sites) were used for the analyses. (PDF 3214 kb)

Molecular phylogeny of Brachyury family members based on an amino acid dataset comprising 436 unambiguously aligned sites. Arrowheads indicate topological incongruities with the tree obtained from comparisons of nucleotides (Fig. 2). Probably due to the short length of the analyzed sequence, the Botryllus schlosseri (urochordate) gene was placed as a sister lineage of a clade comprising cephalochordate and vertebrate genes. (PDF 150 kb)

Conserved synteny around Brachyury in deuterostomes. (DOCX 125 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Steven D. Aird for editing the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported in part by JSPS grants to NS (16H04824), YY (26650087 and 16K21559), HT(15K07174), and JI (15K07172).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors’ contributions

NS and YY conceived the project and JI performed analyses. NS, JI, YY, and HT prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- PEF

Primary domain of expression and function associated with the blastopore

- SEF

Secondary domain of expression and function associated with the notochord

Contributor Information

Jun Inoue, Email: jun.inoue@oist.jp.

Yuuri Yasuoka, Email: yuuri.yasuoka@oist.jp.

Hiroki Takahashi, Email: taka@nibb.ac.jp.

Noriyuki Satoh, Email: norisky@oist.jp, Email: satoh32@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Satoh N. Chordate origins and evolution: the molecular evolutionary road to vertebrates. Boston: Elsevier; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Satoh N, Tagawa K, Lowe CJ, Yu JK, Kawashima T, Takahashi H, et al. On a possible evolutionary link of the stomochord of hemichordates to pharyngeal organs of chordates. Genesis. 2014;52:925–34. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kowalevsky A. Entwicklungsgeschichte der einfachen Ascidien. Mémoires de l’Académie impériale des sciences de St Pétersbourg. 1866;7:11–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gee H. Before the backbone : views on the origin of the vertebrates. 1. London; New York: Chapman & Hall; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satoh N, Tagawa K, Takahashi H. How was the notochord born? Evol Dev. 2012;14:56–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2011.00522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yasuo H, Satoh N. Function of vertebrate T gene. Nature. 1993;364:582–3. doi: 10.1038/364582b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corbo JC, Levine M, Zeller RW. Characterization of a notochord-specific enhancer from the Brachyury promoter region of the ascidian, Ciona intestinalis. Development. 1997;124:589–602. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.3.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi H, Hotta K, Erives A, Di Gregorio A, Zeller RW, Levine M, et al. Brachyury downstream notochord differentiation in the ascidian embryo. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1519–23. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiba S, Jiang D, Satoh N, Smith WC. Brachyury null mutant-induced defects in juvenile ascidian endodermal organs. Development. 2009;136:35–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.030981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Technau U. Brachyury, the blastopore and the evolution of the mesoderm. Bioessays. 2001;23:788–94. doi: 10.1002/bies.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bielen H, Oberleitner S, Marcellini S, Gee L, Lemaire P, Bode HR, et al. Divergent functions of two ancient Hydra Brachyury paralogues suggest specific roles for their C-terminal domains in tissue fate induction. Development. 2007;134:4187–97. doi: 10.1242/dev.010173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leininger S, Adamski M, Bergum B, Guder C, Liu J, Laplante M, et al. Developmental gene expression provides clues to relationships between sponge and eumetazoan body plans. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3905. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Yasuoka Y, Shinzato C, Satoh N. The mesoderm-forming Gene brachyury regulates ectoderm-endoderm demarcation in the coral Acropora digitifera. Curr Biol. 2016;26:2885–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peterson KJ, Harada Y, Cameron RA, Davidson EH. Expression pattern of Brachyury and Not in the sea urchin: Comparative implications for the origins of mesoderm in the basal deuterostomes. Dev Biol. 1999;207:419–31. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tagawa K, Humphreys T, Satoh N. Novel pattern of Brachyury gene expression in hemichordate embryos. Mech Dev. 1998;75:139–43. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(98)00078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gross JM, McClay DR. The role of Brachyury (T) during gastrulation movements in the sea urchin Lytechinus variegatus. Dev Biol. 2001;239:132–47. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holland PW, Koschorz B, Holland LZ, Herrmann BG. Conservation of Brachyury (T) genes in amphioxus and vertebrates: developmental and evolutionary implications. Development. 1995;121:4283–91. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.12.4283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terazawa K, Satoh N. Spatial expression of the amphioxus homolog of Brachyury (T) gene during early embryogenesis of Branchiostoma belcheri. Dev Growth Differ. 1995;37:395–401. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169X.1995.t01-3-00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terazawa K, Satoh N. Formation of the chordamesoderm in the amphioxus embryo: Analysis with Brachyury and fork head/HNF-3 genes. Dev Genes Evol. 1997;207:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s004270050086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dehal P, Satou Y, Campbell RK, Chapman J, Degnan B, De Tomaso A, et al. The draft genome of Ciona intestinalis: Insights into chordate and vertebrate origins. Science. 2002;298:2157–67. doi: 10.1126/science.1080049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papaioannou VE. T-box genes in development: from hydra to humans. Int Rev Cytol. 2001;207:1–70. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(01)07002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papaioannou VE. The T-box gene family: emerging roles in development, stem cells and cancer. Development. 2014;141:3819–33. doi: 10.1242/dev.104471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simakov O, Kawashima T, Marletaz F, Jenkins J, Koyanagi R, Mitros T, et al. Hemichordate genomes and deuterostome origins. Nature. 2015;527:459–65. doi: 10.1038/nature16150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sea Urchin Genome Sequencing C. Sodergren E, Weinstock GM, Davidson EH, Cameron RA, Gibbs RA, et al. The genome of the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Science. 2007;314:941–52. doi: 10.1126/science.1133609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baughman KW, McDougall C, Cummins SF, Hall M, Degnan BM, Satoh N, et al. Genomic organization of Hox and ParaHox clusters in the echinoderm, Acanthaster planci. Genesis. 2014;52:952–8. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Putnam NH, Butts T, Ferrier DE, Furlong RF, Hellsten U, Kawashima T, et al. The amphioxus genome and the evolution of the chordate karyotype. Nature. 2008;453:1064–71. doi: 10.1038/nature06967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang SF, Chen ZL, Yan XY, Yu T, Huang GR, Yan QY, et al. Decelerated genome evolution in modern vertebrates revealed by analysis of multiple lancelet genomes. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Denoeud F, Henriet S, Mungpakdee S, Aury JM, Da Silva C, Brinkmann H, et al. Plasticity of animal genome architecture unmasked by rapid evolution of a pelagic tunicate. Science. 2010;330:1381–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1194167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Mural RJ, Sutton GG, et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291:1304–51. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inoue J, Sato Y, Sinclair R, Tsukamoto K, Nishida M. Rapid genome reshaping by multiple-gene loss after whole-genome duplication in teleost fish suggested by mathematical modeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:14918–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507669112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang JH, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sato Y, Hashiguchi Y, Nishida M. Temporal pattern of loss/persistence of duplicate genes involved in signal transduction and metabolic pathways after teleost-specific genome duplication. BMC Evol Biol. 2009;9:127. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katoh K, Kuma K, Toh H, Miyata T. MAFFT version 5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:511–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Capella-Gutierrez S, Silla-Martinez JM, Gabaldon T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1972–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suyama M, Torrents D, Bork P. PAL2NAL: robust conversion of protein sequence alignments into the corresponding codon alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W609–12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Z. Estimating the pattern of nucleotide substitution. J Mol Evol. 1994;39:105–11. doi: 10.1007/BF00178256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Z. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic estimation from DNA sequences with variable rates over sites: approximate method. J Mol Evol. 1994;39:306–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00160154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whelan S, Goldman N. A general empirical model of protein evolution derived from multiple protein families using a maximum-likelihood approach. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:691–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilkinson DG, Bhatt S, Herrmann BG. Expression pattern of the mouse T gene and its role in mesoderm formation. Nature. 1990;343:657–9. doi: 10.1038/343657a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gentsch GE, Owens NDL, Martin SR, Piccinelli P, Faial T, Trotter MWB, et al. In vivo T-Box transcription factor profiling reveals joint regulation of embryonic neuromesodermal bipotency. Cell Rep. 2013;4:1185–96. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hedges SB, Marin J, Suleski M, Paymer M, Kumar S. Tree of life reveals clock-like speciation and diversification. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32:835–45. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.EnsemblMetazoa33. Ensembl, Hinxton. 2016. http://metazoa.ensembl.org/index.html. Accessed 23 Apr 2016.

- 44.Hemichordate Genomes. Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University, Okinawa. 2016. https://groups.oist.jp/molgenu/hemichordate-genomes. Accessed 7 Apr 2016.

- 45.MarinegenomicsDB. Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University, Okinawa. 2013. http://marinegenomics.oist.jp/gallery. Accessed 25 Apr 2016.

- 46.Branchiostoma floridae-JGI Genome Portal, v1. Joint Genome Institute, Walnut Creek. 2014. http://genome.jgi.doe.gov/Brafl1/Brafl1.home.html. Accessed 15 Jul 2016.

- 47.LanceletDB, v18h27r3. Sun Yatsen University, Guangzho. 2014. http://genome.bucm.edu.cn/lancelet/gbrowser_wel.php. Accessed 15 Jul 2016.

- 48.OikoBase. University of Bergen, Bergen. 2013. http://oikoarrays.biology.uiowa.edu/Oiko. Accessed 23 Apr 2016.

- 49.Botryllus schlosseri Genome Project. Stanford University, Stanford. 2013. http://botryllus.stanford.edu/botryllusgenome. Accessed 24 Apr 2016.

- 50.Ensembl79. Ensembl, Hinxton. 2015. http://mar2015.archive.ensembl.org/index.html. Accessed 5 May 2015.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

cDNA sequence alignment of T-box family members analyzed in the phylogenetic analysis (Additional file 2). Identity to one of the query gene sequences (underlined) is denoted by dots. Only unambiguously aligned sites are presented (525 out of 16,677 sites). Insertions/deletions of specific nucleotides are indicated by dashes. (PDF 9491 kb)

Molecular phylogenies of T-box family members based on a DNA dataset comprising 350 unambiguously aligned sites (excluding 3rd codon positions) (a) and based on an amino acid dataset comprising 175 sites (b). In both trees, the Brachyury family consistently forms a distinct clade among T-box family members. The resulting tree obtained from reanalysis using only this portion is shown in Fig. 2 and Additional file 4. Query sequences used for the BLAST search are marked with black dots. (PDF 551 kb)

cDNA sequence alignment of Brachyury genes (2625 sites in total) analyzed in the phylogenetic analyses (Fig. 2 and Additional file 4). The alignment was constructed using the selected gene sequences from the estimated tree of T-box-containing genes (Additional file 2). Unambiguously aligned sites indicated by a 1 (on the top of the sequences, 1308 sites) were used for the analyses. (PDF 3214 kb)

Molecular phylogeny of Brachyury family members based on an amino acid dataset comprising 436 unambiguously aligned sites. Arrowheads indicate topological incongruities with the tree obtained from comparisons of nucleotides (Fig. 2). Probably due to the short length of the analyzed sequence, the Botryllus schlosseri (urochordate) gene was placed as a sister lineage of a clade comprising cephalochordate and vertebrate genes. (PDF 150 kb)

Conserved synteny around Brachyury in deuterostomes. (DOCX 125 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.