Abstract

Purpose

This study was aimed at developing and validating a quantitative multigene assay for predicting tumor recurrence after gastric cancer surgery.

Experimental Design

Gene expression data were generated from tumor tissues of patients who underwent surgery for gastric cancer (n=267, training cohort). Genes whose expression was significantly associated with activation of YAP1 (a frequently activated oncogene in gastrointestinal cancer), 5-year recurrence-free survival, and 5-year overall survival were first identified as candidates for prognostic genes (156 genes, P < 0.001). We developed the recurrence risk score (RRS) by using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction to identify genes whose expression levels were significantly associated with YAP1 activation and patient survival in the training cohort.

Results

We based the RRS assay on six genes—IGFBP4, SFRP4, SPOCK1, SULF1, THBS, and GADD45B—whose expression levels were significantly associated with YAP1 activation and prognosis in the training cohort The RRS assay was further validated in an independent cohort of 317 patients. In multivariate analysis, the RRS was an independent predictor of recurrence (hazard ratio, 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.02–2.4; P = 0.03). In patients with stage II disease, the RRS had a hazard ratio of 2.9 (95% confidence interval, 1.1–7.9; P = 0.03) and was the only significant independent predictor of recurrence.

Conclusions

The RRS assay was a valid predictor of recurrence in the two cohorts of patients with gastric cancer. Independent prospective studies to assess the clinical utility of this assay are warranted.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Recurrence risk score, YAP1, Prognosis

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer (GC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide (1) and surgery is the mainstay of treatment (2, 3). However, surgery alone benefits primarily patients with relatively early-stage disease. Multimodality therapies, consisting of surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or both, have been established to improve the survival rates of patients (4–7).

Two recent phase III trials showed that more than 40% of patients with stage II or III GC experience a recurrence within 5 years after a curative D2 gastrectomy without adjuvant chemotherapy (6, 7). When chemotherapy was administered in conjunction with a D2 gastrectomy, the absolute increase in 3-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) or disease-free survival was about 13–15% (6, 7). Given the very high clinical burden of GC worldwide, tools are clearly needed for predicting outcomes in patients after gastrectomy. Although conventional approaches using clinicopathological characteristics have been highly useful for prognostication, gene/genomics-based approaches will very likely give us better prognostication and prediction of response to treatment (8–11). Understanding of the biological characteristics associated with the inherent heterogeneity of GC and identification of molecular markers reflecting that heterogeneity would significantly improve patient care.

One of the promising candidate markers of cancer recurrence might be YAP1. When Hippo signaling, a tumor suppressor pathway that is well conserved among species (12, 13), is reduced or absent, YAP1 enters the cell nucleus and increases transcriptional activation of genes involved in proliferation and survival of cancer cells (13, 14). The fact that a high expression level and amplification of YAP1 have been observed in many cancers, including GC (15–21), supports the idea that YAP1 is an oncogene.

In the current study, we found that activated YAP1 is significantly associated with poor prognosis in GC. We used a systematic multistep strategy to develop and validate a robust recurrence risk score (RRS) assay that, by reflecting underlying biological differences among tumors, can help identify patients at high risk of disease recurrence after surgery.

METHODS

Patients, Tissue Samples, and Gene Expression Data

Tumor tissues for the training cohort of GC patients (n = 267) had been obtained surgically between 1999 and 2006 at the Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul; Kosin University College of Medicine, Busan; and Yonsei University Severance Hospital, Seoul; South Korea. All patients underwent a D2 gastrectomy. Of the 267 patients in training cohort, 155 had received adjuvant chemotherapy (either single-agent 5-fluorouracil or a combination of 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin/oxaliplatin, doxorubicin, or paclitaxel). Tumor tissues for the validation cohort (n = 317) had been obtained surgically between 2000 and 2010 at the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam; and Yonsei University Severance Hospital, Seoul; South Korea (the validation cohort did not overlap with the training cohort). All patients in validation cohort also underwent a D2 gastrectomy and received adjuvant chemotherapy (either fluoropyrimidine alone [5-fluorouracil or S-1] or a combination of 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin/oxaliplatin, or doxorubicin). Because any pretreatments can have significant effect on genome characteristics of tumors, pre-treated tissues were not included in training and validation cohorts. Patients were followed up - once every 3–6 months for first 3 years after surgery and once every 6 months after 3 years of surgery. Informed consent for sample collection had been obtained from all patients. The study protocol for retrospective analysis of tumor samples and clinical information was approved by the institutional review boards of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX) and the five Korean hospitals where the tumor tissues had been obtained. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from surgery to death, and RFS was defined as the time from surgery to the first confirmed recurrence. Data were censored when a patient was alive without recurrence at last contact. Samples from the training cohort were fresh frozen tissues; samples from the validation cohort were formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues. Gene expression data from the 267 patients in the training cohort and GC cell lines MKN45 were generated as described in Supplementary Methods. Gene expression data from cell line are available from Gene Expression Omnibus data base (GSE41387). Cell line authentication was performed in 2011 using STR analysis conducted by Yonsei University Severance Hospital DNA analysis facility. All of experiments and analyses were carried out at MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Statistical Analysis

BRB-ArrayTools software v4.3 was used for all statistical analyses (22). Gene expression differences were considered statistically significant if the P value was less than 0.005. Cluster analysis was performed with Cluster and TreeView v3.0 (23). Prediction of a patient’s class was made as described previously (24–28) and in the supplementary methods. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to evaluate independent prognostic factors associated with survival; the RRS (defined below), tumor stage, and other clinicopathological characteristics were included as covariates. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted in the R language environment (http://www.r-project.org).

Expression Analysis Using 48×48 Dynamic quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) Arrays

All expression analyses were carried out as described in the supplementary methods.

Development of the RRS

A multistep strategy was used to develop the RRS from the reference-normalized expression measurements. Six cancer genes were selected and grouped into three categories based on correlation between the results of microarray and qRT-PCR experiments and nonoverlapping biological characteristics as described in Results: stress response (GADD45B), cellular signaling (IGFBP4 and SFRP4), and interaction with the microenvironment (SPOCK1, SULF1, and THBS). To calculate the RSS, first, the expression level of each gene was multiplied by the Cox coefficient value derived from RFS data of the training cohort, generating a GENEcox value. Second, category scores were calculated by multiplying the total GENEcox value for each category by a contribution factor as follows: stress response score = GADD45Bcox × 0.4, cell signaling score = (IGFBP4cox + SFRP4cox) × 0.2, and microenvironment score = (SPOCK4cox + SULF4cox + THBS4cox) × 0.1. The contribution factors were set so that the three categories had approximately equal contributions to the RRS. Third, to generate a dynamic score range, each category score was transformed by applying a natural exponential function (ecategory score), and RRSraw was generated by summation of the transformed scores. Fourth, to generate a range of 0 to 100, the RRSraw was rescaled as follows: RRS = (RRSraw − 10) × 10, with RRS = 0 if RRS < 0 and RRS = 100 if RRS > 100. RRSs were categorized as follows: <20, low risk; 20 to 40, intermediate risk; >40, high risk as indicated in Supplementary methods.

RESULTS

Activation of YAP1 Is Significantly Associated with Prognosis in GC Patients

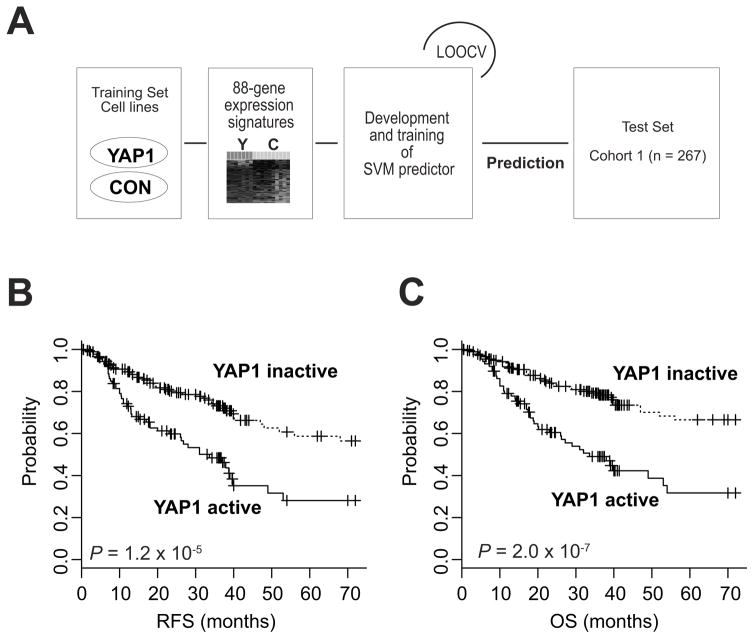

Since YAP1 is frequently activated in many cancers, including GC (29–32), we first examined the clinical relevance of YAP1 activation in GC by generating gene expression data from GC cells overexpressing YAP1 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Further analysis of gene expression data identified 88 genes whose expression was significantly associated with YAP1 activation (Supplementary Fig. 2A). We next tested the clinical significance of YAP1 activation in human GC by comparing the YAP1 signature with gene expression data from GC tissue samples. Gene expression data from the 267 samples in the training cohort (Table 1) were used for this analysis. An SVM algorithm (33) was applied to calculate the probability of YAP1 activation in each tumor sample (Fig. 1A). Briefly, YAP1 signature expression data from cell lines were used to generate an SVM classifier for estimating the likelihood that a particular gastric tumor belonged to the subgroup in which the YAP1 signature was present (active YAP1 subgroup) or the subgroup in which the signature was absent (inactive YAP1 subgroup). When the tumors were thus categorized, a third of the patients (n = 88) were predicted to be classified into the active YAP1 GC subgroup. Kaplan-Meier plots for the training cohort showed significant differences in RFS and OS (P < 0.001) between the two subgroups (Fig. 1B,C), strongly indicating that YAP1 may play an important role in the clinical course of GC. Further analysis showed that YAP1 signature is independent of stages (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Clinical and Pathological Features of Gastric Cancer Patients

| Variable | No. of Patients (%)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Training Cohort (n = 267) | Validation Cohort (n = 317) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 188 (70.4) | 193 (60.1) |

| Female | 79 (29.6) | 124 (39.9) |

| NA | 0 | 0 |

| Age, median (range) | 59 yr (28–83 yr) | 58 yr (25–82 yr) |

| AJCC stage | ||

| I | 63 (23.6) | 36 (11.3) |

| II | 48 (18.0) | 136 (42.9) |

| III | 87 (32.6) | 128 (40.4) |

| IV | 67 (25.1) | 17 (5.4) |

| NA | 2 (0.7) | 0 |

| Tumor stage | ||

| T1 | 22 (8.2) | 18 (5.6) |

| T2 | 89 (32.6) | 169 (53.3) |

| T3 | 120 (45.0) | 127 (40.1) |

| T4 | 29 (10.9) | 3 (0.9) |

| NA | 7 (3.3) | 0 |

| Nodal stage | ||

| N0 | 80 (30.0) | 39 (12.3) |

| N1 | 85 (31.9) | 183 (57.8) |

| N2 | 58 (21.7) | 80 (25.2) |

| N3 | 38 (14.2) | 15 (4.7) |

| NA | 6 (2.2) | 0 |

| Lauren classification | ||

| Intestinal | 160 (59.9) | 81 (25.5) |

| Diffuse | 72 (27) | 155 (48.9) |

| Mixed | 19 (7.1) | 17 (5.4) |

| NA | 16 (6.0) | 64 (20.2) |

Abbreviations: NA, information not available; AJCC, American Joint Commission on Cancer manual, 6th edition.

Figure 1. Construction of prediction models using data from the training cohorts.

(A) Schematic overview of the strategy used for constructing prediction models and evaluating predicted outcomes based on gene expression signatures. LOOCV, leave-one-out cross-validation. CON, control; SVM, support vector machine. (B & C) Kaplan-Meier plots of recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) of patients stratified according to activation of YAP1 in tumors. P values were obtained by using the log-rank test. Censored data are indicated by the + symbol.

Screening of Candidate Genes for Assessing Risk of Recurrence

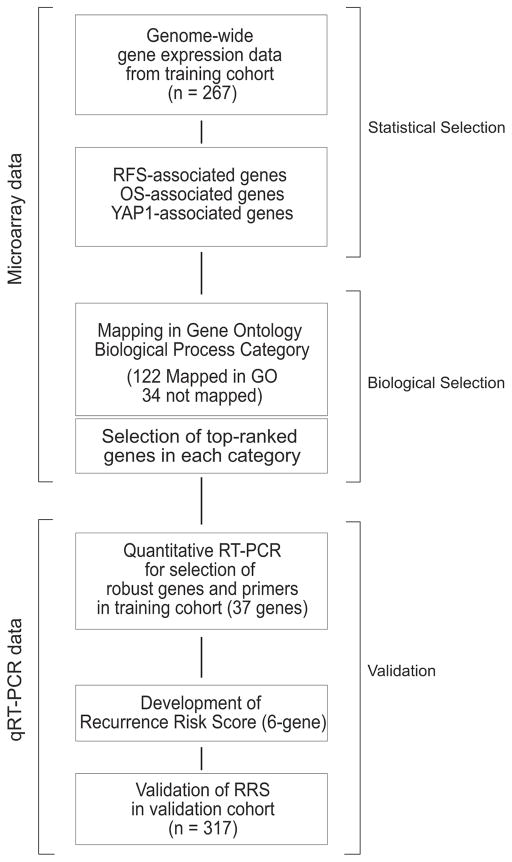

Because all gene expression data were generated from fresh frozen tissues, which are not easily available in the clinic, and because the prediction model used a complex algorithm with long gene list from microarray data, which is not practical in the clinic, we sought to identify a small number genes predictive of GC recurrence by using easily available FFPE tissues. We used a two-step strategy to identify candidate genes for development of an easy-to-use prognostic scoring system (Fig. 2). First, we identified candidate genes whose expression was significantly associated with RFS, OS, and activation of YAP1 in the training cohort; of the 824, 793, and 652 genes identified, respectively, 156 were associated with all three variables (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Second, we identified biologically nonredundant genes by an informatics approach. Because many of the 156 candidate genes could be involved in similar biological processes, we tried to identify a few genes that would represent diverse biological process. To avoid overrepresentation of particular biological processes or characteristics in the final gene set, we mapped these genes to biological processes in the Gene Ontology database (34) and selected top-ranked genes for each biological process (Supplementary Table 1). Of the 156 genes, 40 unique genes with minimum overlap in biological functions were selected (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Figure 2. Development and validation of the recurrence risk score assay.

RFS, recurrence-free survival; OS, overall survival; GO, Gene Ontology database; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Development of the RRS Assay

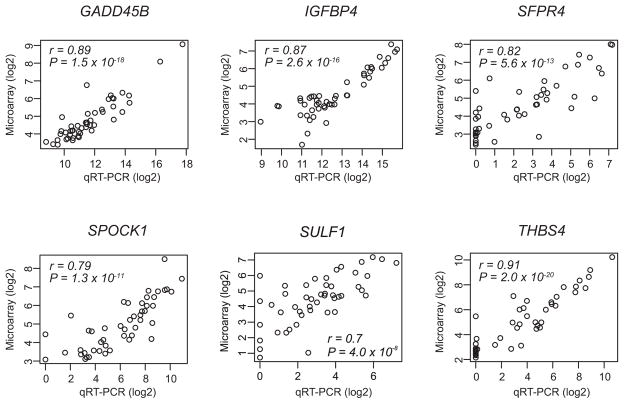

We next assessed the reproducibility of gene expression measurements in our microarray study by carrying out qRT-PCR experiments with RNAs that were randomly selected from the training cohort (48 samples). Reproducibility was high for the vast majority of genes. In particular, intermeasurement correlation was extremely high for 26 genes (r > 0.7 and P < 1.0 × 10−7). On the basis of nonoverlapping biological characteristics, we selected six genes: IGFBP4 and SFRP4, cellular signaling; SPOCK1, SULF1, and THBS, interaction with the microenvironment; and GADD45B, stress response (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 2). To generate RRSs in the range of 0 to 100 from the reference-normalized expression measurements, a four-step strategy was used (Supplementary Fig. 6A). As expected, the three RRS categories—low, intermediate, and high risk—were significantly associated with RFS (P = 0.02) and OS (P = 0.006) (Supplementary Fig. 6B and 6D). The combined low-intermediate risk category was also significantly associated with RFS (P = 0.005) and OS (P = 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 6C and 6E). ROC analysis showed that overall performance of RRS for prognostication of patients is better than individual genes (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Figure 3.

Concordance of gene expression data from quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT- PCR) and microarray experiments.

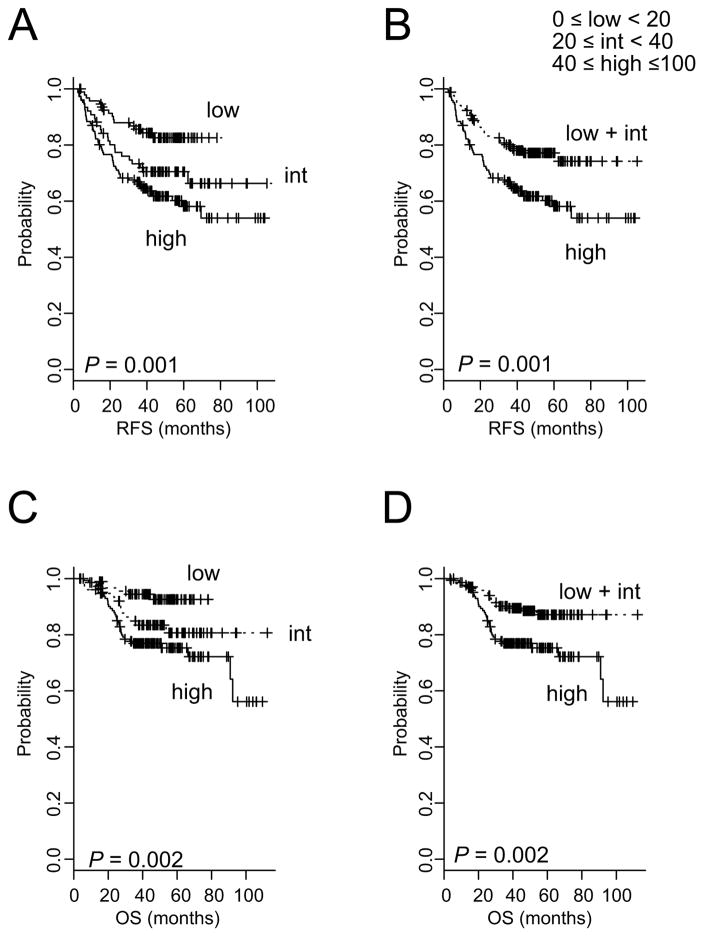

Validation of the RRS Assay

We next sought to validate the RRS assay in an independent cohort by using RNAs from FFPE tissues. We found that the continuous RRS was significantly associated with risk of recurrence as evidenced by their linear correlation with probability of recurrence within 5 years postsurgery (Supplementary Fig. 9A). When patients in validation cohort were stratified according to RRS, the 5-year RFS rate was 82.5% for low-risk, 70.5% for intermediate-risk, and 58.1% for high-risk patients (P = 0.001; Fig. 4A). Likewise, two subgroup stratification showed significant association with RFS (P = 0.001; Fig. 4B). RRS was also significantly associated with OS (Fig. 4C and 4D). Furthermore, when patients with stage II/III disease (n = 264), who are routinely treated with adjuvant chemotherapy as standard treatment, were only included in analysis, association of RRS with prognosis remained significant (Supplementary Fig. 9B–9E). Taken together, these results clearly demonstrate the robustness of the RRS regardless of differences in the source of RNAs (fresh frozen or FFPE tissues) and its clinical relevance.

Figure 4. Significant association of recurrence risk scores with recurrence-free survival (RFS) in the validation cohort.

(A & C) Patients were stratified into three groups on the basis of the indicated RRS cutoffs. int, intermediate. (B & D) Patients were stratified into two groups. P values were obtained by using the log-rank test. Censored data are indicated by the + symbol.

To evaluate the prognostic value of the RRS in combination with other clinical variables, we next carried out univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses. Like TNM (tumor-node-metastasis) stage, which is a well-known predictor of RFS, RRS was a statistically significant indicator of RFS (hazard ratio = 1.92, 95% confidence interval = 1.02–3.6, P = 0.04; univariate analysis) (Supplementary Table 3). In multivariate analysis, which included all clinicopathological variables with moderate association (P < 0.2), RRS remained a significant prognostic factor (hazard ratio = 1.6, 95% confidence interval = 1.02–2.4, P = 0.03).

Because stage II GC is considered to be heterogeneous as reflected in lower recurrence rate than stage III but higher recurrence rate than stage I after D2 gastrectomy (6, 7, 35), we carried out a subset analysis in stage II disease. In multivariate analyses, RRS was a significant predictor of RFS (Table 2), providing independent predictive value beyond tumor stage and number of nodes examined. Taken together, our data strongly suggest that the RRS model measures underlying biological characteristics that are predictive of clinical outcomes and that are not captured by traditional clinical and pathological indicators.

Table 2.

Multivariate Cox Regression Analyses of Recurrence Free Survival of Patients with Stage II disease in validation cohort (n = 136).

| Variable | Multivariate Analysis

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p value | |

| Patient Sex (Male or Female) | 0.97 (0.4–2.6) | 0.96 |

| Age (>70 years) | 0.5 (0.07–4.0) | 0.53 |

| T stage (T3 or T2, T1) | 1.4 (0.4–4.8) | 0.61 |

| N stage (N1, N2 or N0) | 0.7 (0.2–2.5) | 0.61 |

| RRS (High or Int/Low) | 2.9 (1.09–7.9) | 0.03 |

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that YAP1 activation is significantly associated with poor prognosis in GC. Using a systematic multistep strategy, we developed a six-gene-based RRS assay that can identify patients at high risk for cancer recurrence after surgery by measuring underlying biological differences. The robustness of the RRS assay was validated in an independent cohort of 317 patients. Because the RRS system uses qRT-PCR on RNAs from FFPE tissues, it can be easily implemented in the clinic.

Multigene assays are currently being investigated for their abilities to improve prognostication and prediction of treatment outcomes for various cancers. For example, the Oncotype DX Breast Cancer Assay (Genomic Health, Redwood City, CA) uses 21 genes (16 recurrence risk-associated genes and 5 reference genes) that were identified from 250 candidate genes using tumor recurrence data and FFPE tumor tissues (8). In this system, the mRNA expression level of each gene measured by qRT-PCR is used to generate a recurrence score. In a retrospective analysis of data from two clinical trials, the assay not only quantified risk of recurrence in patients with hormone receptor-positive, axillary lymph node-negative breast cancer (8) but also predicted the magnitude of the chemotherapy benefit (9). Another assay system, the Oncotype DX Colon Cancer Assay (Genomic Health), uses 7 recurrence risk-associated and 6 chemotherapy benefit-associated genes that were identified from 761 candidate genes (10). Clinical validation using stage II/III colon cancer clinical trial data showed that a recurrence score based on 7 genes was prognostic for recurrence, but a treatment score based on 6 genes was not predictive of benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy (11). All these recurrence score validation analyses were retrospectively conducted and thus could not give definitive conclusion. Prospective clinical trials to evaluate the clinical usefulness of these assays are under way.

To the best of our knowledge, no assay system that can potentially provide prognostic or predictive information to assist decision making for GC in clinics has been tested in clinical trials. In most existing multigene assays for GC, genes were selected using predefined candidate genes from the literature (36) or small scale screening of candidate genes (37). To overcome our previous analysis with smaller number of patients that did not well reflect biological characteristics of GC (37), we applied multi-step systematic strategy that may reflect underlying biology of GC and prognostic significance. In the current study, we found the robustness of the YAP1 signature in predicting GC recurrence after resection, which were in agreement with previous observations in other cancers (38–41). Therefore, we decided to develop an easy-to-use RRS assay that reflects underlying biological differences (YAP1 activation) in GC. We found that 156 genes were significantly associated with RFS, OS, and YAP1 activation. From the 156 candidate genes, we identified 6 recurrence risk-associated genes on the basis of biological function and data reproducibility of gene expression measurements in qRT-PCR and microarray experiments. Notably, one of the six genes, GADD45B, was previously identified as one of recurrence risk-associated genes in colon cancer (10), suggesting that this gene may play a critical role in progression of gastrointestinal cancers in general.

The continuous RRS was linearly correlated with probability of recurrence, allowing classification of risk as low, intermediate, or high. The six-gene RRS assay was validated in an independent patient cohort, and the prognostic relevance of RRS was independent of other clinical variables. Given that the rate of recurrence for stage II GC after a D2 gastrectomy alone is ~30% compared with >50% for stage III (6, 7, 35), the decision on whether adjuvant chemotherapy should be administered is more challenging in stage II than in stage III. The subset analysis clearly showed that the six-gene RRS assay can be used to stratify stage II patients according to recurrence risk. These findings suggest that the six-gene RRS assay might help clinicians decide whether to administer adjuvant chemotherapy to patients after gastrectomy. Because our RRS assay uses qRT-PCR of RNA from FFPE tissues, we expect that it will be easily applicable in clinical practice.

The limitations of our study should be acknowledged. First, the study was performed retrospectively. Second, the sample of patients was heterogeneous and included patients with stage I or IV disease, who were not candidates for adjuvant chemotherapy. However, vast majority of patients were in stage II or III. In subset analysis with patients with stage II/III disease, who are candidates for adjuvant chemotherapy, association of RRS with prognosis remained significant. Third, the association between the RRS and benefit from adjuvant treatment could not be investigated because all patients in validation cohort received adjuvant chemotherapy. The potential of RRS in predicting benefit from adjuvant therapy after gastrectomy needs to be validated in future prospective study. Forth, since all patients in current study were from Korea, the applicability of our RRS system to patients with different ethnicities needs to be further investigated.

In conclusion, our robust RRS assay can help facilitate rational design of clinical studies by stratifying patients according to their risk of cancer recurrence. Prospective studies will need to be conducted to validate the clinical usefulness of the assay.

Supplementary Material

Translational relevance.

Recurrence of gastric cancer occurs in up to 30%–40% of patients within 5 years after surgery. However, there are no clinically useful easy-to-use prognostication methods that can reliably predict the recurrence after surgery. Our data suggested that activation of YAP1, downstream target of Hippo pathway, is significantly associated with poor prognosis of patients with gastric cancer. Thus, we developed recurrence risk scores based on expression of six genes reflecting activation of YAP1 in gastric cancer. The recurrence risk score may help clinicians prognosticate recurrence of gastric cancer patients after surgery and might be useful in deciding whether to administer additional treatment to patients after surgery.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA127672, CA129906, CA138671, CA 172741, and CA150229); 2016 Institutional Research Grant (IRG) and 2016 Sister Institute Network Fund (SINF) grant from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center; Bio & Medical Technology Development Program (M10642040002-07N4204-00210); and Scientific Research Center Program (2012R1A5A1048236); Research Initiative grant from Korean Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Authors’ Contributions

Conception and design: K-W Lee, SS Lee, J-S Lee

Development of methodology: S-B. Kim, Kim, S-C. Kim, W. Jeong, BH Sohn

Acquisition of data (provided animals, acquired and managed patients, provided facilities, etc.): K-W Lee, SS Lee, H-J J, H-S Lee, SC Oh, BH Sohn, SH Lee, J-H Cheong, JY Cho, JY Lim, SH Noh, ES Park,

Analysis and interpretation of data (e.g., statistical analysis, biostatistics, computational analysis): K-W Lee, SS Lee, J-E Hwang, JJ Shim, M Cha, ES Park, S-C Kim, S-B Kim, Y-K Kang, JA Ajani, H-J Jang, H-S Lee, J-S Lee.

Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: KW Lee, SS Lee, J-S. Lee

Administrative, technical, or material support (i.e., reporting or organizing data, constructing databases): S-B. Kim, M Cha, BH Sohn.

Study supervision: J-S. Lee

Reference List

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hundahl SA, Phillips JL, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base Report on poor survival of U.S. gastric carcinoma patients treated with gastrectomy: Fifth Edition American Joint Committee on Cancer staging, proximal disease, and the “different disease” hypothesis. Cancer. 2000;88:921–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kovoor PA, Hwang J. Treatment of resectable gastric cancer: current standards of care. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:135–42. doi: 10.1586/14737140.9.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, Thompson JN, van de Velde CJ, Nicolson M, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macdonald JS, Smalley SR, Benedetti J, Hundahl SA, Estes NC, Stemmermann GN, et al. Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:725–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakuramoto S, Sasako M, Yamaguchi T, Kinoshita T, Fujii M, Nashimoto A, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer with S-1, an oral fluoropyrimidine. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1810–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bang YJ, Kim YW, Yang HK, Chung HC, Park YK, Lee KH, et al. Adjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin for gastric cancer after D2 gastrectomy (CLASSIC): a phase 3 open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:315–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61873-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paik S, Shak S, Tang G, Kim C, Baker J, Cronin M, et al. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2817–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paik S, Tang G, Shak S, Kim C, Baker J, Kim W, et al. Gene expression and benefit of chemotherapy in women with node-negative, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3726–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Connell MJ, Lavery I, Yothers G, Paik S, Clark-Langone KM, Lopatin M, et al. Relationship between tumor gene expression and recurrence in four independent studies of patients with stage II/III colon cancer treated with surgery alone or surgery plus adjuvant fluorouracil plus leucovorin. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3937–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.9538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray RG, Quirke P, Handley K, Lopatin M, Magill L, Baehner FL, et al. Validation study of a quantitative multigene reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction assay for assessment of recurrence risk in patients with stage II colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4611–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.8732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halder G, Johnson RL. Hippo signaling: growth control and beyond. Development. 2011;138:9–22. doi: 10.1242/dev.045500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu FX, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway: regulators and regulations. Genes Dev. 2013;27:355–71. doi: 10.1101/gad.210773.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong W, Guan KL. The YAP and TAZ transcription co-activators: key downstream effectors of the mammalian Hippo pathway. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:785–93. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Da CL, Xin Y, Zhao J, Luo XD. Significance and relationship between Yes-associated protein and survivin expression in gastric carcinoma and precancerous lesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4055–61. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lam-Himlin DM, Daniels JA, Gayyed MF, Dong J, Maitra A, Pan D, et al. The hippo pathway in human upper gastrointestinal dysplasia and carcinoma: a novel oncogenic pathway. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2006;37:103–9. doi: 10.1007/s12029-007-0010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zender L, Spector MS, Xue W, Flemming P, Cordon-Cardo C, Silke J, et al. Identification and validation of oncogenes in liver cancer using an integrative oncogenomic approach. Cell. 2006;125:1253–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Overholtzer M, Zhang J, Smolen GA, Muir B, Li W, Sgroi DC, et al. Transforming properties of YAP, a candidate oncogene on the chromosome 11q22 amplicon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12405–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605579103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J, Yang YC, Zhu JS, Zhou Z, Chen WX. Clinicopathologic characteristics of YES-associated protein 1 overexpression and its relationship to tumor biomarkers in gastric cancer. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2012;25:977–87. doi: 10.1177/039463201202500415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Da CL, Xin Y, Zhao J, Luo XD. Significance and relationship between Yes-associated protein and survivin expression in gastric carcinoma and precancerous lesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4055–61. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song S, Ajani JA, Honjo S, Maru DM, Chen Q, Scott AW, et al. Hippo coactivator YAP1 upregulates SOX9 and endows esophageal cancer cells with stem-like properties. Cancer Res. 2014;74:4170–82. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simon R, Lam A, Li M-C, Ngan M, Menenzes S, Zhao Y. Analysis of Gene Expression Data Using BRB-Array Tools. Cancer Informatics. 2007;3:11–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14863–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JS, Thorgeirsson SS. Functional and genomic implications of global gene expression profiles in cell lines from human hepatocellular cancer. Hepatology. 2002;35:1134–43. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JS, Chu IS, Mikaelyan A, Calvisi DF, Heo J, Reddy JK, et al. Application of comparative functional genomics to identify best-fit mouse models to study human cancer. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1306–11. doi: 10.1038/ng1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee JS, Heo J, Libbrecht L, Chu IS, Kaposi-Novak P, Calvisi DF, et al. A novel prognostic subtype of human hepatocellular carcinoma derived from hepatic progenitor cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:410–6. doi: 10.1038/nm1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JS, Leem SH, Lee SY, Kim SC, Park ES, Kim SB, et al. Expression signature of E2F1 and its associated genes predict superficial to invasive progression of bladder tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2660–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oh SC, Park YY, Park ES, Lim JY, Kim SM, Kim SB, et al. Prognostic gene expression signature associated with two molecularly distinct subtypes of colorectal cancer. Gut. 2012;61:1291–8. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Xie C, Li Q, Xu K, Wang E. Clinical and prognostic significance of Yes-associated protein in colorectal cancer. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:2169–74. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0751-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shao DD, Xue W, Krall EB, Bhutkar A, Piccioni F, Wang X, et al. KRAS and YAP1 converge to regulate EMT and tumor survival. Cell. 2014;158:171–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song M, Cheong JH, Kim H, Noh SH, Kim H. Nuclear expression of Yes-associated protein 1 correlates with poor prognosis in intestinal type gastric cancer. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:3827–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, Ye K, Niu B, Lu C, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502:333–9. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramaswamy S, Tamayo P, Rifkin R, Mukherjee S, Yeang CH, Angelo M, et al. Multiclass cancer diagnosis using tumor gene expression signatures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:15149–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211566398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–9. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sasako M, Sakuramoto S, Katai H, Kinoshita T, Furukawa H, Yamaguchi T, et al. Five-year outcomes of a randomized phase III trial comparing adjuvant chemotherapy with S-1 versus surgery alone in stage II or III gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4387–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.5908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pietrantonio F, De BF, Da PV, Perrone F, Pierotti MA, Gariboldi M, et al. A review on biomarkers for prediction of treatment outcome in gastric cancer. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:1257–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cho JY, Lim JY, Cheong JH, Park YY, Yoon SL, Kim SM, et al. Gene expression signature-based prognostic risk score in gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1850–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park YY, Sohn BH, Johnson RL, Kang MH, Kim SB, Shim JJ, et al. Yes-associated protein 1 and transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif activate the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 pathway by regulating amino acid transporters in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2016;63:159–72. doi: 10.1002/hep.28223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee KW, Lee SS, Kim SB, Sohn BH, Lee HS, Jang HJ, et al. Significant association of oncogene YAP1 with poor prognosis and cetuximab resistance in colorectal cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:357–64. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jeong W, Kim SB, Sohn BH, Park YY, Park ES, Kim SC, et al. Activation of YAP1 is associated with poor prognosis and response to taxanes in ovarian cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:811–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sohn BH, Shim JJ, Kim SB, Jang KY, Kim SM, Kim JH, et al. Inactivation of Hippo Pathway Is Significantly Associated with Poor Prognosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:1256–64. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.