Abstract

Background

Flooding during seasonal monsoons affects millions of hectares of rice-cultivated areas across Asia. Submerged rice plants die within a week due to lack of oxygen, light and excessive elongation growth to escape the water. Submergence tolerance was first reported in an aus-type rice landrace, FR13A, and the ethylene-responsive transcription factor (TF) gene SUB1A-1 was identified as the major tolerance gene. Intolerant rice varieties generally lack the SUB1A gene but some intermediate tolerant varieties, such as IR64, carry the allelic variant SUB1A-2. Differential effects of the two alleles have so far not been addressed. As a first step, we have therefore quantified and compared the expression of nearly 2500 rice TF genes between IR64 and its derived tolerant near isogenic line IR64-Sub1, which carries the SUB1A-1 allele. Gene expression was studied in internodes, where the main difference in expression between the two alleles was previously shown.

Results

Nineteen and twenty-six TF genes were identified that responded to submergence in IR64 and IR64-Sub1, respectively. Only one gene was found to be submergence-responsive in both, suggesting different regulatory pathways under submergence in the two genotypes. These differentially expressed genes (DEGs) mainly included MYB, NAC, TIFY and Zn-finger TFs, and most genes were downregulated upon submergence. In IR64, but not in IR64-Sub1, SUB1B and SUB1C, which are also present in the Sub1 locus, were identified as submergence responsive. Four TFs were not submergence responsive but exhibited constitutive, genotype-specific differential expression. Most of the identified submergence responsive DEGs are associated with regulatory hormonal pathways, i.e. gibberellins (GA), abscisic acid (ABA), and jasmonic acid (JA), apart from ethylene. An in-silico promoter analysis of the two genotypes revealed the presence of allele-specific single nucleotide polymorphisms, giving rise to ABRE, DRE/CRT, CARE and Site II cis-elements, which can partly explain the observed differential TF gene expression.

Conclusion

This study identified new gene targets with the potential to further enhance submergence tolerance in rice and provides insights into novel aspects of SUB1A-mediated tolerance.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi: 10.1186/s12284-017-0192-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Submergence tolerance, SUB1A, Rice, Transcription factors

Background

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is an important food crop globally and the most advanced genetic monocot model amongst the cereal crops (Cantrell and Reeves, 2002). Biotic and abiotic stresses, such as drought and heat, are known to be detrimental to crop production. Rice production is additionally constraint by submergence stress during the rainy season with complete submergence and water stagnation affecting about 20 million hectares of rice fields in the tropics, causing significant yield and economic losses, and food insecurity (Septiningsih et al., 2012). Rice fields can be flooded with several meters of water for weeks and plants die within a few days from lack of oxygen and impaired photosynthesis (Gibbs and Greenway, 2003; Fukao and Bailey-Serres, 2004). Furthermore, in the attempt to escape the water, plants excessively elongate leaves thereby depleting their carbohydrate and energy reserves, and as water recedes, the plants lodge thus impairing any recovery growth (Singh, Singh, and Ram, 2001; Das, Sarkar, and Ismail, 2005; Fukao, Xu, Ronald, and Bailey-Serres, 2006).

Submergence-tolerant rice varieties were identified in the early 1960s and breeding efforts to introgress this trait into rice cultivars have been ongoing since the 1970s. Submergence tolerance was initially considered a complex trait involving many genes located in multiple quantitative trait loci (QTL) (Mackill, Ismail, Singh, Labios, and Paris, 2012). However, advances in molecular marker technologies and optimized phenotyping techniques aided in the identification of the major QTL Submergence tolerance 1 (Sub1) (Xu, Deb, and Mackill, 2004). Sub1 was identified from the aus-type rice landrace FR13A (Flood Resistance 13A) and it provided a breakthrough in the understanding of submergence tolerance mechanisms, enabling marker-assisted breeding of submergence-tolerant rice (Fukao et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2006; Singh, Mackill, and Ismail, 2009; Bailey-Serres et al., 2010; Mackill et al., 2012). Sub1 rice varieties are now widely grown across Asia enhancing plant survival in flooded fields with yield advantages of one ton per hectare or more (Septiningsih et al., 2009; Mackill et al., 2012).

Molecular and comparative sequence analysis of the Sub1 genomic region in submergence-tolerant and -intolerant rice varieties revealed the presence of a variable cluster of two to three ethylene-responsive TFs (ERFs) genes, namely SUB1A, SUB1B and SUB1C (Xu et al., 2006). In submergence-intolerant and moderately tolerant rice genotypes, the SUB1A-1 gene is either absent, due to an inversion-deletion, or present as an allelic variant, SUB1A-2 (Singh et al., 2010) (Additional file 1: Figure S1a).

Transgenic approaches identified SUB1A-1 as the major tolerance gene, since its constitutive expression conferred submergence tolerance to an intolerant rice variety (M202), which naturally lacks the SUB1A gene (Xu et al., 2006). Under complete submergence, the main phenotypic effect observed in SUB1A-1 overexpression and Sub1 near isogenic lines (NILs), is a significantly reduced elongation growth (Additional file 1: Figure S1b). The Sub1 plants assume a “quiescence” status which prevents excessive elongation growth thereby preserving carbohydrate reserves and preventing an energy crisis, as well as lodging once the water recedes (Fukao et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2006; Voesenek and Bailey-Serres, 2009).

In contrast to the SUB1A-mediated tolerance, deepwater rice responds to submergence with rapid GA-induced elongation growth, so that plants reach the water surface for access to light and oxygen (Fukao et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2006; Bailey-Serres and Voesenek, 2008; Singh et al., 2010). As is the case for SUB1A-1, rapid elongation growth in deepwater rice is also ethylene induced but regulated by different ERFs, namely SNORKEL1 (SK1) and SNORKEL2 (SK2) (Hattori et al., 2009; Nagai, Hattori, and Ashikari, 2010).

At the molecular level, SUB1A-1 functions by preventing ethylene-induced, GA-mediated elongation growth via enhancing the level of the GA-inhibitors SLENDER RICE 1 (SLR1) and SLENDER RICE LIKE 1 (SLRL1) (Fukao and Bailey-Serres, 2008). Further to this, presence of SUB1A-1 is associated with the negative regulation of genes involved in carbohydrate catabolism and cell elongation (via expansins) and positive regulation of genes involved in ethanolic fermentation, such as alcohol dehydrogenase (Fukao et al., 2006; Bailey-Serres and Voesenek, 2010). Recently some studies have revealed that SUB1A-1 is phosphorylated by MITOGEN-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE3 (MAPK3) and in turn physically interacts with MAPK3 and binds to its promoter (Singh and Sinha, 2016). Overall, the suppressed growth and metabolic adjustments during flooding confers a higher recovery rate to Sub1 plants compared to non-Sub1 plants as illustrated in the aerial photo of the IRRI demonstration plot (Additional file 1: Figure S1b).

The aforementioned molecular and physiological studies were conducted by comparing Sub1 NILs and SUB1A-1 overexpressing plants with their corresponding wild-type varieties (M202 and Liaogeng, respectively), which have the SUB1B and SUB1C genes but naturally lack the SUB1A gene (Fukao et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2006). However, an allelic variant of the SUB1A gene exists, SUB1A-2, which is present in a range of rice varieties (Fukao et al., 2006; Singh et al., 2010). Phenotyping of these SUB1A-2 varieties revealed a variable level of submergence tolerance ranging from about 4% to 40% plant survival after two weeks of submergence. SUB1A expression analysis subsequently showed that both, SUB1A-1 and SUB1A-2 are submergence-inducible and expressed at similar levels in leaves, stems and developing panicles. However, gene expression in internodes associated well with submergence tolerance, i.e., a higher level of SUB1A expression in internodes under submergence was observed in varieties with the Sub1A-1 allele compared to varieties with the SUB1A-2 allele (Singh et al., 2010) (Additional file 1: Figure S1c).

To further address differences between SUB1A-1 and SUB1A-2 allele effects, we analysed internode samples from IR64 (SUB1A-2) and the IR64-derived NIL IR64-Sub1, which carries the tolerant Sub1 locus including the SUB1A-1 allele (Singh et al., 2010). Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) targeting nearly 2500 rice TF genes based on the Nipponbare reference genome (Caldana, Scheible, Mueller-Roeber, and Ruzicic, 2007) was conducted with internode samples from plants submerged for 30 h and corresponding non-submerged control plants to (a) identify TFs that are differentially regulated upon submergence in IR64 and IR64-Sub1, (b) compare TFs in both genotypes to provide insights in the SUB1A regulatory pathway and (c) analyse the promoter region of SUB1A-1 and SUB1A-2 to identify single nucleotide polomorphisms (SNPs) that create putative cis-elements and could be binding sites for upstream TFs.

Methods

Plant material and submergence treatment

Seeds of the rice variety IR64 (accession number 66970) and the IR64-Sub1 NIL (accession number IR8419422–139) were provided by the International Rice Germplasm Collection (IRGC) at IRRI, Philippines. Seeds were incubated at 55 °C for 5 days to break dormancy before pre-germination in petri dishes at 37 °C in an incubator. Three-day-old seedlings were transplanted into pots filled with soil substituted with 3 g ammonium sulphate. Four pots with two plants for each accession were grown for 75 days until booting/heading stage, i.e., the onset of internode elongation. At that stage, plants were completely submerged in a concrete tank filled with about 2 m of tap water for 30 h (Singh et al., 2010). Non-submerged control plants were kept under natural conditions in an IRRI screenhouse and sampled in parallel. From each plant, multiple internodes from three tillers were sampled from a total of four submerged and two control plants per genotype. Samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

RNA isolation and cDNA preparation

Total RNA was isolated from the internode tissues of the control and submerged plants using TRIzol® (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quantity and quality of RNA samples were assessed using a Nanodrop ND-100 (Thermo Scientific) and by agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA contamination was removed by treating RNA samples with RNase-free DNase I according to the protocol provided (Promega). cDNA was synthesized from 5 μg of total RNA using Superscript™ III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Germany) as per the manufacturer’s protocol.

Data source for transcription factor sequences and primers

A qRT-PCR platform was used for expression profiling of the rice TF genes (Caldana et al., 2007). The initial source dataset used for the annotation and primer design was version 2.0 of the Rice Genome Annotation Project (RGAP) (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/) and encompassed a total of 2508 (2487 unique) TF genes. TF sequences were extracted from version 1 of the Plant Transcription Factor Database (Riano-Pachon, Ruzicic, Dreyer, and Mueller-Roeber, 2007; Perez-Rodriguez et al., 2010). The TF genes were initially synchronized with version 5.0 of the RGAP Pseudomolecule and genome annotations resulting in 2221 unique genes with appropriate annotation in version 5.0. Twenty of these were represented in two distinct positions in the qPCR platform as internal controls. Based on version 5.0 of the RGAP Pseudomolecules, 266 unique genes out of 2487 missed annotations (Additional file 2: Table S1). The TF genes were further revised based on the most recent RGAP version 7.0 annotation and details are given in Additional file 2: Table S2. For the genes with missing annotations in Release 7, BLAST searches were performed taking the sequences of the PCR amplicons as queries against the RGAP database.

Transcription factor profiling

The qPCR platform used for this study had the primer pairs specific to the TF genes described above and were distributed on a total of seven 396 well-plates (Caldana et al., 2007). On each plate, twelve wells were reserved for three reference genes (RGs; represented in quadruplicate) and four wells were for negative water control. For the current study, the RGs 9631.m04973, 9629.m05807 and 9633.m03388 were used (Additional file 2: Table S3 and S4). Of these, 9633.m03388 (LOC_Os05g36290, actin) was selected as the best suitable RG for all subsequent calculations and normalizations. There were three technical replicates for each of the four samples (IR64C, IR64S, IR64-Sub1C and IR64-Sub1S, where C denoted control and S submergence treated plants). Real-time PCR analysis was based on SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems, Germany) and was conducted in a total volume of 5 μl (2.5 μl of SYBR Green master mix, 0.5 μl of cDNA (1.25 ng/μl) and 200 nM forward and reverse primers). PCR amplifications were carried out as described in (Caldana et al., 2007) in an ABI PRISM 7900 HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Germany).

Data processing and statistical analysis

Based on the obtained amplification curves, the Ct values (fractional cycle number at threshold), the value of PCR efficiency and the corresponding coefficient of determination (R2) were calculated using LinRegPCR software (Ruijter et al., 2009) for all four samples (IR64C, IR64S, IR64-Sub1C and IR64-Sub1S). Ct values for all reactions were log2 transformed (Additional file 2: Table S3 and S4). The average Ct values for RGs (CtRG) were calculated from Ct values of quadruplicates for each 396 well-plate separately for control and submerged conditions. The RG selected for all subsequent calculations was actin (LOC_Os05g36290). Based on the average CtRG, the ΔCt for each selected gene (SG) was calculated as ΔCt = CtSG - CtRG. All reactions with R2 < 0.995, reflecting low-quality amplifications and those designated as “undetermined” (did not deliver a Ct < 40) were excluded from further analyses. The obtained sets of ΔCt values for control and submerged conditions for each gene model (in three replicates) were examined for significant differential expression using LIMMA’s moderated t-test (Smyth, 2005). LIMMA computes moderated t-statistics and log-odds of differential expression by empirical Bayes shrinkage of the standard errors towards a common value. False Discovery Rate (FDR) corrections of p-values were carried out using Benjamini and Hochberg method (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). A gene was considered differentially expressed if the moderated t-test resulted in a corrected p-value <0.01. Hence, the list of differentially expressed TF genes and corresponding log2FC (fold change) values under submergence stress were generated from both, the IR64 and the IR64-Sub1 submerged plants compared to the respective control plants. In addition, we examined the data for genotype-specific expression differences. For this, we used the contrast matrix referred from the LIMMA manual (https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/devel/bioc/vignettes/limma/inst/doc/ usersguide.pdf) as follows:

Contrast.matrix <− makeContrasts (SubmergenceIR64 = IR64S-IR64C, SubmergenceIR64Sub1 = IR64Sub1S - IR64Sub1C, Genotype = (IR64Sub1S + IR64Sub1C) - (IR64S + IR64C) levels = design).

Promoter analysis

The promoter sequences of the SUB1A-1 and SUB1A-2 alleles (Additional file 2: Table S5) were aligned using Clustal Omega (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/) and analysed using PlantPAN 2.0 (Chow et al., 2016) as well as manually. A 2 kb upstream DNA region of the DEGs was extracted from RAP-DB (http://rapdb.dna.affrc.go.jp/index.html) and analysed by PlantPAN (http://plantpan2.itps.ncku.edu.tw/) to identify putative cis-regulatory elements.

Results

In order to investigate the difference between submergence tolerance as mediated by the strong allele SUB1A-1 (present in IR64-Sub1) and the weak allele SUB1A-2 (present in IR64), expression of 2487 rice TF genes was quantified by qPCR in internodes of submerged and non-submerged control plants. Internodes were chosen for this study since differences in the expression of the SUB1A-1 and SUB1A-2 alleles were most pronounced in this tissue (Singh et al., 2010).

Update of TF gene annotations

The 2487 TF genes given in Additional file 2: Table S1 were synchronised to the latest version 7.0 of the RGAP Pseudomolecules and annotation of the rice genome (Kawahara et al., 2013). For 72 of the 266 genes with missing annotations, we could obtain annotations from version 7.0 (Additional file 2: Table S2) and one gene was marked as obsolete. Therefore, only 193 genes remained as not being annotated in version 7.0. Nine genes previously annotated in version 5 miss annotations in version 7, eight of these are now considered obsolete and one is without annotation in versions 6.1 and 7.0 of RGAP annotations. Hence, a total of 2284 TF gene models were updated with version 7.0 annotations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the total number of genes with and without annotations in the RGAP pseudomolecules version 7.0

| Number of TF Genes with and without annotations in version 7.0 of RGAP annotations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Version 5.0 annotation from RGAP | |||||

| Genes | All | Missing annotations | With annotations | ||

| Total | 2508 | 267 | 2241 | ||

| Unique | 2487 | 266 | 2221 | ||

| Version 7.0 annotation from RGAP | |||||

| Obsolete | With annotations | Obsolete | Without annotations | ||

| Unique | 1 | 72 | 8 | 1 | |

| 193 missing annotations | 2212 annotated | ||||

| Total | 2284 annotated genes | ||||

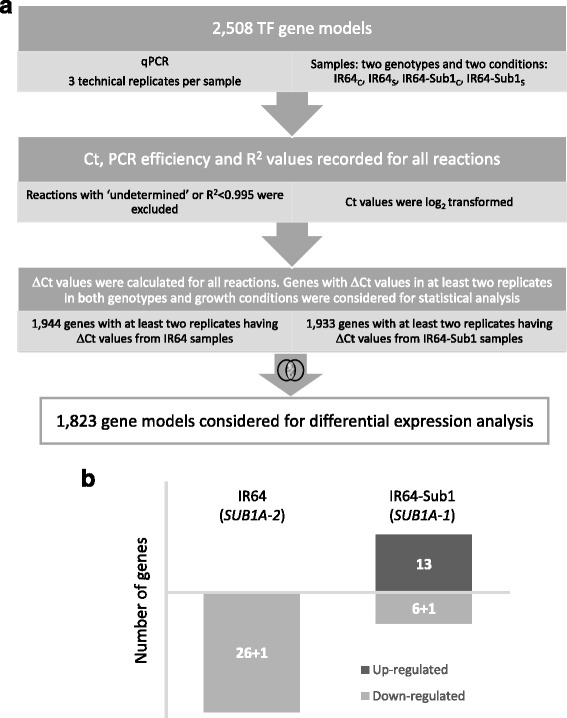

Differential gene expression analysis in IR64 and IR64-Sub1

The expression patterns of the TF genes in four samples (IR64C, IR64S, IR64-Sub1C and IR64-Sub1S) were analysed by qPCR. Statistical comparisons for the identification of DEGs were performed only for those genes which possessed at least two calculated ΔCt values in both genotypes and both growth conditions (control and submerged). For performing differential expression analysis an intersect of 1823 TF genes, 1944 genes of the IR64 dataset and 1933 of the IR64-Sub1 dataset, were taken as input for LIMMA’s moderated t-test comparisons (Fig. 1a). The resulting p-values, FDR corrected p-values and log2FC values for all gene models are provided in Additional file 2: Table S6.

Fig. 1.

Identification of differentially expressed transcription factor genes. a Overview of the data processing and selection of genes as input for the statistical analysis of differential gene expression using LIMMA. b Differentially expressed transcription factor genes under submergence stress in IR64 and IR64-Sub1. +1 indicates the common TF gene (MYB), which is submergence-responsive in both genotypes

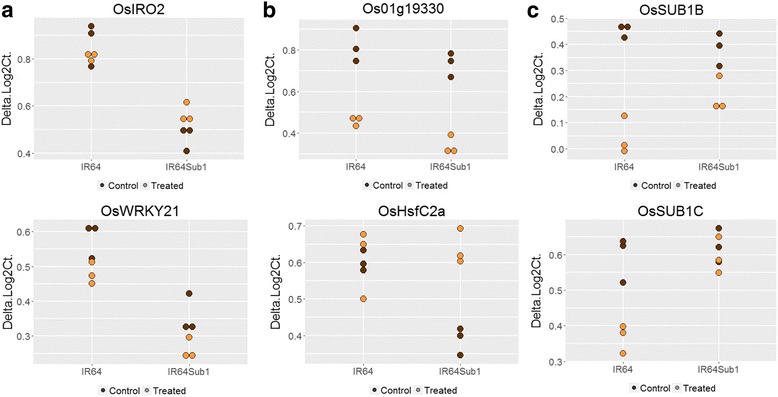

Genotype-specific expression differences of TFs

The genotypic comparison revealed a total of four TF genes that were not submergence responsive but depicted genotype-dependent expression differences between IR64 and IR64-Sub1 (Table 2). These genes code for a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) factor OsIRO2 (LOC_Os01g72370), OsWRKY21 (LOC_Os01g60640) and two TIFY type TFs (OsTIFY11e/OsZIM18/OsJAZ13 (LOC_Os10g25230); OsTIFY11d/OsJAZ12 (LOC_Os10g25290)). All four genes had overall lower expression levels in IR64-Sub1 compared to IR64 (Fig. 2a).

Table 2.

Details of the differentially expressed TF genes and their corresponding fold change value (log2FC) under submergence in IR64 and IR64-Sub1

| Gene # | Locus ID ver 7.0 | Gene Description/TF Family | Gene name | og2FC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype specific differences |

1 | LOC_Os01g72370 | Helix-loop-helix DNA-binding domain containing protein; bHLH | OsIRO2/OsbHLH056 | −0.64 |

| 2 | LOC_Os10g25230 | ZIM domain containing protein; Tify | OsTIFY11e/OsZIM18/OsJAZ13 | −0.50 | |

| 3 | LOC_Os10g25290 | ZIM domaincontaining protein; Tify | OsTIFY11d/OsJAZ12 | −0.36 | |

| 4 | LOC_Os01g60640 | WRKY21; WRKY | OsWRKY21 | −0.44 | |

| Submergence responsive in IR64 |

1 | LOC_Os07g22730 | AP2 domain containing protein; AP2-EREBP | OsERF136/AP2/EREBP#106 | −0.19 |

| 2 | LOC_Os05g27930 | AP2 domain containing protein; AP2-EREBP | OsERF042/AP2/EREBP#048/OsDREB2b | −0.28 | |

| 3 | LOC_Os04g47059 | bHLH | OsbHLH16/OSB2 | 0.26 | |

| 4 | LOC_Os01g36220 | bZIP transcription factor domain containing protein; bZIP | OsbZIP4 | 0.31 | |

| 5 | LOC_Os02g35770 | Homeobox associated leucine zipper; HB | OsHox7 | 0.18 | |

| 6 | LOC_Os02g13800 | HSF-type DNA binding domain containing protein; HSF | OsHsfC2a/OsHsf-05 | 0.25 | |

| 7 | LOC_Os02g40530 | MYB family transcription factor; MYB | MYB/OsMPS | −0.28 | |

| 8 | LOC_Os07g37210 | MYB family transcription factor; MYB | MYB/OsMyb7 | 0.17 | |

| 9 | LOC_Os11g47460 | MYB family transcription factor; MYB | MYB | 0.16 | |

| 10 | LOC_Os06g51260 | MYB family transcription factor; MYB-related | MYB/ OsLHY-like_chr.6 | 0.36 | |

| 11 | LOC_Os01g47370 | MYB family transcription factor; MYB-related | MYB | 0.20 | |

| 12 | LOC_Os08g06110 | MYB family transcription factor; MYB-related | MYB/OsCCA1/OsLHY/LHY-like_chr.8 | 0.33 | |

| 13 | LOC_Os07g26150 | MYB family transcription factor; MYB-related | MYB/Hsp40 | 0.18 | |

| 14 | LOC_Os04g41560 | B-box zinc finger family protein; Orphans | OsBBX11/OsSTO | 0.21 | |

| 15 | LOC_Os08g08120 | B-box zinc finger family protein; Orphans | OsBBX24 | 0.21 | |

| 16 | LOC_Os09g25060 | WRKY76; WRKY | OsWRKY76 | −0.31 | |

| 17 | LOC_Os03g08310 | ZIM domain containing protein; Tify | OsTIFY11a/OsJAZ9 | −0.31 | |

| 18 | LOC_Os02g35329 | RING-H2 finger protein ATL3F | ATL3F/OsELF5 | −0.28 | |

| 19 | LOC_Os07g43740 | Zinc finger, C3HC4 type domain containing protein | Zn finger | 0.20 | |

| Common gene | 1 | LOC_Os01g19330 | MYB family transcription factor; MYB | MYB | −0.394 |

| −0.36 | |||||

| Submergence responsive in IR64 | 1 | LOC_Os08g06120 | B3 DNA binding domain containing protein; ABI3VP1 | Similar to NGA1 (NGATHA1) | −0.26 |

| 2 | LOC_Os09g11480 | AP2 domain containing protein; AP2-EREBP | OsSUB1B/OsERF063/AP2/EREBP#166 | −0.41 | |

| 3 | LOC_Os09g11460 | AP2 domain containing protein; AP2-EREBP | OsSUB1C/ OsERF73/AP2/EREBP#122 | −0.23 | |

| 4 | LOC_Os07g47790 | AP2 domain containing protein; AP2-EREBP | OsERF067/AP2/EREBP#076 | −0.22 | |

| 5 | LOC_Os03g22170 | AP2 domain containing protein; AP2-EREBP | OsERF066/AP2/EREBP#030 | −0.31 | |

| 6 | LOC_Os01g54890 | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor 2; AP2-EREBP | OsERF922/AP2/EREBP#078 | −0.21 | |

| 7 | LOC_Os01g64020 | Transcription factor; bZIP | OsLG2/OsbZIP11 | −0.16 | |

| 8 | LOC_Os02g49230 | CCT/B-box zinc finger protein; C2C2-CO-like | OsBBX7 | −0.17 −0.18 −0.20 |

|

| 9 | LOC_Os01g74410 | MYB family transcription factor; MYB | OsMYB48–1 | −0.23 −0.32 |

|

| 10 | LOC_Os03g20090 | MYB family transcription factor; MYB | OsMYB2 | −0.18 | |

| 11 | LOC_Os08g43550 | MYB family transcription factor; MYB | OsMYB7 | −0.24 | |

| 12 | LOC_Os03g04900 | MYB family transcription factor; MYB | MYB | −0.20 | |

| 13 | LOC_Os11g05614 | No apical meristem protein; NAC | OsONAC7/ONAC17/ONAC30/OsNAC111 | −0.26 | |

| 14 | LOC_Os07g37920 | No apical meristem protein; NAC | OsSNAC/ONAC10/OsSTA199 | −0.18 | |

| 15 | LOC_Os03g04070 | No apical meristem protein; NAC | OsANAC34/ONAC22 | −0.21 | |

| 16 | LOC_Os01g66120 | No apical meristem protein; NAC | OsNAC6/SNAC2/NAC48 | −0.26 | |

| 17 | LOC_Os01g10580 | B-box zinc finger family protein; Orphans | OsBBX1/OsDBB3c | −0.22 | |

| 18 | LOC_Os12g10660 | B-box zinc finger family protein; Orphans | OsBBX30 | −0.21 | |

| 19 | LOC_Os02g05470 | CCT motif family protein; Orphans | OsCCT03/OsCMF3 | −0.43 | |

| 20 | LOC_Os07g07690 | PHD-finger domain containing protein; PHD | PHD | −0.43 | |

| 21 | LOC_Os05g49620 | WRKY19; WRKY | OsWRKY19 | −0.25 | |

| 22 | LOC_Os09g25070 | WRKY62; WRKY | OsWRKY62 | −0.33 | |

| 23 | LOC_Os02g08440 | WRKY71; WRKY | WRKY71/OsEXB1 | −0.25 | |

| 24 | LOC_Os09g30400 | WRKY90; WRKY | OsWRKY90 | −0.18 | |

| 25 | LOC_Os06g03580 | Zinc RING finger protein | OsBBI1 | −0.20 | |

| 26 | LOC_Os01g11460 | Zinc finger, C3HC4 type domain containing protein | Zn finger ATL2K | −0.20 |

Fig. 2.

Differentially expressed transcription factor genes in IR64 and IR64-Sub1. Representative dot plots are shown illustrating three different categories of DEGs: a Non-submergence-responsive genes with genotype-dependent differential expression, (b). submergence-responsive genes in IR64-Sub1, (c). and submergence-responsive genes in IR64

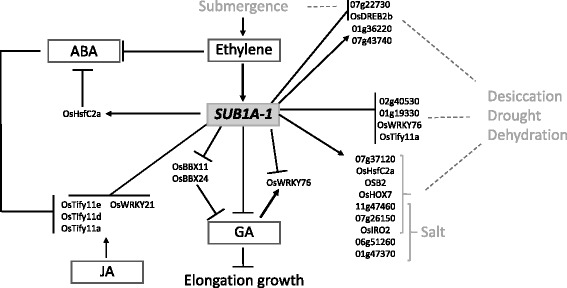

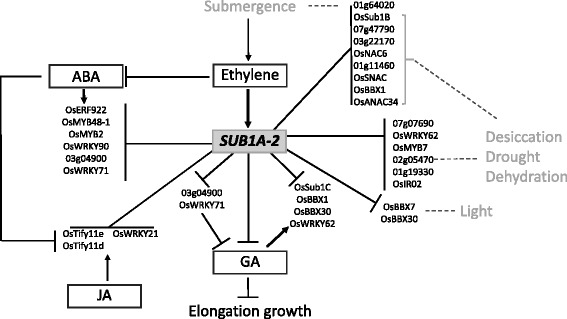

Studies have shown these four TF genes to be regulated (upregulated - ↑ or downregulated- ↓) under the following conditions: iron (Fe) starvation (OsIRO2 ↑); desiccation/drought (OsIRO2 ↓, TIFY11d & 11e ↑); salinity (OsIRO2 ↓, TIFY11d & 11e ↑); salicylic acid (SA) (OsWRKY21 ↑); wounding (TIFY11d & 11e ↑); pathogens (TIFY11d & 11e ↑); cold (TIFY11d & 11e ↑); JA (TIFY11d & 11e ↑), GA (TIFY11e ↓) and ABA (TIFY11d & 11e ↓) (Ogo et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2013; Ramamoorthy, Jiang, Kumar, Venkatesh, and Ramachandran, 2008; Ye, Du, Tang, Li, and Xiong, 2009; Ranjan et al., 2015; Yang, Chen, Jen, Liu, and Chang, 2015; Shankar, Bhattacharjee, and Jain, 2016; Xiang et al., 2017). Under submergence, OsTIFY11e was reported to be downregulated in M202-Sub1 compared to M202 but upregulated under drought (Fukao, Yeung, and Bailey-Serres, 2011). Information on these genes is summarized in Figs. 3 and 4 and details are given in Additional file 2: Table S7.

Fig. 3.

Differentially expressed transcription factor genes in IR64-Sub1. An overview of the transcription factor genes and their related pathways is provided for all genes that are specifically submergence-responsive in IR64-Sub1 which carries the SUB1A-1 allele. The figure is based on a literature review, see text for details

Fig. 4.

Differentially expressed transcription factor genes in IR64. An overview of the transcription factor genes and their related pathways is provided for all genes that are specifically submergence-responsive in IR64 which carries the SUB1A-2 allele. The figure is based on a literature review, see text for details

Submergence-responsive TFs in IR64-Sub1

In IR64-Sub1, 19 TF genes were found to be submergence-responsive, of which thirteen genes were upregulated and six genes were downregulated (Fig. 1b, Table 2). The group of upregulated genes include: 6 MYB factors, 3 Zn finger TFs, 1 Heat Shock Factor (HSF), 1 bHLH, 1 bZIP, and 1 HOX TFs. And the seven (6 + 1) downregulated genes include: 2 AP2-type TFs, 2 MYBs, a WRKY, a TIFY and a RING-H2 finger gene. One of the seven downregulated genes, the MYB factor LOC_01g19330, was downregulated in response to 30 h of submergence in both IR64 and IR64-Sub1 genotypes and is placed in the category of a common gene (Fig. 2, Table 2). Studies of these TFs in relation to abiotic stress and hormonal response are detailed below and an overview of the data is provided in Fig. 3.

Upregulated genes

MYB TFs have been reported to play various biological functions in plants. With respect to abiotic stresses and hormonal pathways the following have been documented in rice: salinity stress (LOC_Os06g51260 ↓, LOC_Os01g47370 ↓, LOC_Os07g26150 ↓); GA (MYB_LOC_Os11g47460 ↓, LOC_Os01g47370 ↓), desiccation/drought showed both up and downregulated depending on variety analysed (MYB_LOC_Os07g37210 ↑↓, MYB_LOC_Os11g47460 ↑↓, MYB_LOC_Os07g26150 ↓); and seed dormancy regulated via ABA-GA antagonism (MYB_LOC_ Os08g06110 ↑) (Baxter et al., 2007; Gao et al., 2009; Katiyar et al., 2012; Boyden et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2016; Park et al., 2015; Shankar et al., 2016; Xiang et al., 2017).

The Zn finger TFs included two B-Box domain genes, namely OsBBX11 (LOC_Os04g41560) and OsBBX24 (LOC_Os08g08120), and one gene with a Zn-finger binding domain (LOC_Os07g43740). OsBBX11 has been reported to have two BBX domains, whereas OsBBX24 has one BBX domain. These two genes are responsive to various hormones; auxin (OsBBX11 ↓); GA (OsBBX11 ↓, OsBBX24 ↓); cytokinin (OsBBX11 ↓); kinetin (OsBBX11 ↓, OsBBX24 ↓↓) and naphthalene acetic acid (NAA) (OsBBX24 ↓). OsBBX11 was also seen to be upregulated by light and downregulated by desiccation (Huang, Zhao, Weng, Wang, and Xie, 2012; Shankar et al., 2016). LOC_Os07g43740 has been document to be upregulated under several abiotic stresses, i.e. anoxia, drought, desiccation, salt, heat and chilling (Ham, Moon, Hwang, and Jang, 2013; Shankar et al., 2016).

The heat shock factor (HSF) gene, OsHsfC2a (LOC_Os02g13800), which was upregulated upon submergence in IR64-Sub1, has also been reported to have increased expression under other abiotic stresses, i.e. heat, cold, oxidative stress (Mittal et al., 2009; Mittal et al., 2012) as well as drought and desiccation (Chauhan, Khurana, Agarwal, and Khurana, 2011; Shankar et al., 2016). This TF also showed upregulation in response to brassinosteroids (BR) and SA but the expression decreased in response to ABA (Chauhan et al., 2011; Shankar et al., 2016). Promoter analysis of OsHsfC2a revealed presence of light, ABA and methyl-jasmonate (MeJA) responsive cis-elements (Wang, Zhang, and Shou, 2009).

The bHLH OsbHLH016/OSB2 (LOC_Os04g47059) and the HOX OsHOX7 (LOC_Os02g35770) TF genes show upregulation under desiccation stress (Shankar et al., 2016), whereas no information on the bZIP factor (LOC_Os01g36220) is available.

Only two of the above-mentioned genes have previously been reported to be upregulated under submergence and dehydration in IR64-Sub1, namely the bZIP gene (LOC_Os01g36220) and the Zn-finger gene (LOC_Os07g43740) (Fukao et al., 2011). The latter is also upregulated under anoxia, heat and chilling (Ham et al., 2013; Shankar et al., 2016).

Downregulated genes

In this category, two AP2-type TFs (LOC_Os07g22730, LOC_Os05g27930) have previously been reported as submergence-responsive (Jung et al., 2010). LOC_Os07g22730 belongs to the AP2 group IIIb and was slightly upregulated in M202-Sub1 after 6d of submergence but downregulated under anoxia. This gene is also upregulated under desiccation and salt stress (Shankar et al., 2016) and known to be highly expressed in roots and embryos (Rashid, He, Yang, Hussain, and Yan, 2012). The other AP2 factor (LOC_Os05g27930) codes for OsDREB2b, which was reported to be slightly downregulated under submergence in both, M202 and M202-Sub1 (Jung et al., 2010). OsDREB2b is a transcriptional activator and is upregulated in the nodes of drought-stressed plants (Todaka et al., 2012). It is also responsive to high and low-temperature stress and over-expressing lines exhibit increased plant survival under drought (Matsukura et al., 2010).

The two downregulated MYB TF genes (LOC_Os02g40530, LOC_01g19330) encode putative calmodulin-binding proteins and are known to play important roles in signal transduction regulating plant development and adaptation responses to different stress conditions (Chantarachot, Buaboocha, Gu, and Chadchawan, 2012). Both genes were reported to be upregulated under drought, desiccation and salt stress whereas downregulated when treated with GA (Chantarachot et al., 2012; Katiyar et al., 2012; Shankar et al., 2016; Xiang et al., 2017).

The other downregulated genes in this category code for OsWRKY76 (LOC_Os09g25060), OsTIFY11a/OsJAZ9 (LOC_Os03g08310) and a RING-H2 finger gene (LOC_Os02g35329). OsWRKY76 is constitutively expressed in vegetative and reproductive tissues and upregulated under desiccation, salinity, auxin, GA and MeJA treatments (Ramamoorthy et al., 2008; Shankar et al., 2016). In contrast, OsTIFY11a/JAZ9 is specifically expressed in young panicles (Ye et al., 2009). OsTIFY11a/JAZ9 is widely stress-responsive and induced by JA, wounding, drought, desiccation, salt and cold stress but downregulated by ABA treatment (Shankar et al., 2016). It was shown that overexpression of TIFY11a/JAZ9 enhances shoot growth in rice under salt and mannitol treatment (Ye et al., 2009). OsTIFY11a/JAZ9 interacts with OsCOI1 suggesting its involvement in JA signalling as a transcriptional regulator for salt stress tolerance (Wu, Ye, Yao, Zhang, and Xiong, 2015). No information was found for the RING-H2 finger gene.

Submergence-responsive TFs in IR64

There were 26 submergence-responsive TF genes specific to IR64, excluding the above-mentioned MYB factor LOC_01g19330 common to both genotypes. The genes encode: 5 AP2 domain TFs, 4 NAC, 4 WRKY, 4 MYB, 1 B3 DNA binding protein and a number of different Zn-finger proteins. All of these genes were downregulated under submergence (Fig. 1b; Table 2) and an overview of the data is provided in Fig. 4. Documented studies of these TF genes are summarised below based on their response to submergence, hormone signalling pathways and other abiotic and biotic stresses.

The most responsive gene in IR64 was LOC_Os07g07690, an uncharacterized gene with a putative Jas-domain (pham16135), plant homeodomain (PHD) and Zn-finger domain (cd15539, pfam00628, smart00249). The second most downregulated gene, interestingly, was SUB1B (LOC_Os09g11480), one of the three ERF factors within the Sub1 QTL (Xu et al., 2006) (Table 2, Fig. 2 and Additional file 1: Figure S1a). SUB1B is reportedly not responsive to GA or ethylene (Fukao et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2006). The other AP2 TF genes include SUB1C (LOC_Os09g11460) and three additional ERFs (LOC_Os03g22170, LOC_Os07g47790 and OsERF922: LOC_Os01g54890). The SUB1C gene was reported to be induced by GA and ethylene and upregulated under submergence in the intolerant japonica variety M202, which naturally lacks the SUB1A gene (Fukao et al., 2006). The same study also suggested that SUB1A-1 negatively regulates SUB1C expression. Our results are in agreement with that finding and suggest that SUB1A-2 also negatively regulates SUB1C under submergence (Fig. 2). However, downregulation of SUB1C was not observed in IR64-Sub1 suggesting an alternate regulatory pathway. One of the recent studies revealed that desiccation stress could also downregulate SUB1C and SUB1B in IR64 plants (Shankar et al., 2016). The three other AP2/ERF genes have also been reported from studies on submergence tolerance. OsERF067 (LOC_Os07g47790) was shown to be upregulated in M202 under submergence and in IR64 under dehydration. This gene was seen to be upregulated by SUB1A during submergence and dehydration in M202-Sub1 and IR64-Sub1 suggesting a downstream position in the SUB1A pathway (Fukao et al., 2011). Contrastingly, another study reported downregulation of OsERF067 in M202 under submergence but upregulation in M202-Sub1 (Jung et al., 2010). The same study showed a similar expression pattern for OsERF066 (LOC_Os03g22170). Both of these AP2 factors are downregulated under GA treatment (Xiang et al., 2017), involved in cytokinin response (Lara et al., 2004) and are positively responsive to anaerobic germination in Nipponbare (Magneschi and Perata, 2009). The gene OsERF922 was shown to be upregulated in M202-Sub1 after 6 days of submergence but downregulated in M202 after 1 day of submergence (Jung et al., 2010). OsERF922 is strongly induced by ABA, salt treatment, and biotic stress. A study on the crosstalk between abiotic and abiotic stress signalling through modulation of ABA levels further suggests that OsERF922 functions as a transcriptional activator (Liu, Chen, Liu, Ye, and Guo, 2012).

Of the 4 NAC genes downregulated in IR64, two have been reported to respond to various biotic and abiotic stresses, including submergence. OsANAC34 (LOC_Os03g04070) is upregulated under submergence, desiccation and by rice stripe virus infection but downregulated under GA (Nuruzzaman et al., 2010; Shankar et al., 2016; Xiang et al., 2017). The OsNAC6/SNAC2 (LOC_Os01g66120) gene contains ABRE and CBE elements in its promoter and is upregulated under drought, cold and submergence stress (Nuruzzaman et al., 2010). These two genes are responsive in Nipponbare, suggesting they are not under the control of SUB1A, which is absent in this rice variety. OsNAC6/SNAC2 was also reported to be upregulated under desiccation and salinity stress in a drought-tolerant rice (N22) mutant (Shankar et al., 2016).

The C3HC4 Zn finger (LOC_Os01g11460) and B-Box Zn finger OsBBX1 (LOC_Os01g10580) TF genes were upregulated under submergence in the intolerant variety M202, the former also in M202-Sub1, and in IR64 upon dehydration (Fukao et al., 2011). OsBBX1 is highly expressed in seeds, roots and the endosperm, and is induced by auxin, GA and cytokinin (Huang et al., 2012). The bZIP TF factor LOC_Os01g64020 was found to be downregulated under submergence in IR64 plants in our study and was reported to be nitrogen-responsive in studies in rice and Arabidopsis (Obertello, Shrivastava, Katari, and Coruzzi, 2015).

The induction of ethylene in response to submergence is known to contribute to a decline in ABA and an increase in GA thereby regulating elongation growth (see above). ABA in-turn is involved in the regulation of the crosstalk between JA and SA signalling pathways (Liu et al., 2012). A complex interplay and fine-tuning of hormonal responses is therefore likely to determine the level of submergence tolerance.

Several studies have shown that four of the IR64-downregulated TFs are upregulated (↑) or downregulated (↓) in response to ABA: OsMYB48–1 (LOC_Os01g74410) ↑; R2R3-type OsMYB2 gene (LOC_Os03g20090) ↑; OsWRKY90 (LOC_Os09g30400) ↑ and OsERF066 (LOC_Os03g22170) ↑. These genes were also reported to be responsive to PEG-induced water stress (OsMYB48–1 ↑↓), H2O2 (OsMYB48–1 ↑), drought (OsMYB48–1 ↑, OsMYB2 ↑; OsWRKY90 ↑), dehydration (OsMYB48–1 ↑), desiccation (OsMYB2 ↑), salinity (OsMYB48–1 ↑, OsMYB2 ↑) and cold (OsMYB48–1 ↑, OsMYB2 ↑). Other stress responses include pathogen attack (OsWRKY90 ↑), wounding (OsWRKY90 ↑), iron toxicity (OsWRKY90 ↑) and senescence (OsWRKY90 ↑) (Ricachenevsky, Sperotto, Menguer, and Fett, 2010) (Katiyar et al., 2012; Xiong et al., 2014). OsMYB48–1 also plays a positive role in drought and salinity tolerance by regulating ABA synthesis (Xiong et al., 2014).

The other important set of genes is GA-responsive, including OsSUB1C (↑) and the Zn finger OsBBX30 (LOC_Os12g10660) mostly expressed in vegetative tissues and mature panicles (↑), the B-Box factors OsBBX1 and OsBBX7 (↑), the WRKY gene OsWRKY62 (LOC_Os09g25070), highly expressed in mature leaves and young roots (↑), OsWRKY71/OsEXB1 (LOC_Os02g08440) (↓), OsANAC34 (↓) and two MYB TF genes (OsMYB2 and LOC_Os03g04900) (↓). Expression of these TFs was also responsive to light (OsBBX30 ↑), auxin (OsBBX30 ↑, OsBBX1 ↑), cytokinin (OsBBX30 ↑, OsBBX1 ↑), IAA (OsWRKY62 ↑), SA (OsWRKY62 ↑, OsWRKY71↑), JA (OsWRKY71↑), ABA (OsWRKY71↑↑), desiccation (OsWRKY62 ↑, MYB ↑), cold (OsWRKY62 ↓), osmotic stress (OsWRKY62 ↑), salinity (MYB ↑), and pathogen attack (OsWRKY62 ↑) (Ramamoorthy et al., 2008; Shankar et al., 2016; Xiang et al., 2017). OsBBX7 (LOC_Os02g49230) is highly expressed in leaves, hull and endosperm and is light-responsive. It displays a diurnal expression pattern, i.e. upregulated at night under short-day conditions and high expression during light compared to dark under long-day conditions (Huang et al., 2012). OsWRKY62 was also observed to be non-responsive to ABA treatment and therefore likely acts in an ABA-independent signalling pathway. OsWRKY71 is a general stress-responsive gene and was reported to be upregulated by submergence in M202 and dehydration in IR64. However, this response was not observed in M202-Sub1 and IR64-Sub1 (Fig. 2) (Fukao et al., 2011). This gene is also involved in desiccation and salt stress responses in the rice variety N22 (Shankar et al., 2016) and overexpression of OsWRKY71 in rice enhances tolerance to cold (Kim et al., 2016) and resistance to Xanthomonas (Liu, Bai, Wang, and Chu, 2007; Berri et al., 2009; Chujo et al., 2013). The MYB TF gene shares high sequence similarity with MULTIPASS (OsMPS), which regulates plant growth via expansins and was shown to be downregulated by GA and auxin but upregulated by ABA and cytokinin (Schmidt et al., 2013).

The other TF genes have not been reported to be ABA- or GA-responsive and/or responsive to submergence. OsBBI1 (LOC_Os06g03580) and OsONAC7 (LOC_Os11g05614) have been associated with biotic stress response. OsBBI1 encodes a RING finger protein with E3 ligase activity, which modifies cell wall defence and confers broad-spectrum disease resistance to blast fungus (Magnaporthe oryzae). Expression of OsBBI1 is also induced by the rice blast fungus, benzothiadiazole and SA (Li et al., 2011). OsONAC7 is expressed and highly upregulated in rice stripe virus (RSV) and tungro virus (RTSV) infected plants (Nuruzzaman et al., 2010). The NAC TF gene OsSNAC (LOC_Os07g37920) was shown to be downregulated under drought stress in the intolerant variety Nipponbare (Nuruzzaman et al., 2010) but upregulated under desiccation stress in the rainfed varieties N22 and Pokkali (Shankar et al., 2016).

Limited information is available for the remaining genes downregulated in IR64. An in-silico study proposed B3 domain factor LOC_Os08g06120 to colocalize with a QTL for seed width (Peng and Weselake, 2013). The PHD Zn finger gene OsMYB7 (LOC_Os08g43550) and the CCT motif orphan gene (LOC_Os02g05470) have no defined function but were both downregulated under desiccation stress in IR64 (Shankar et al., 2016). OsWRKY19 (LOC_Os05g49620) was shown to be constitutively low expressed across different tissues and was upregulated by IAA and SA with no clear involvement in any stress response (Ramamoorthy et al., 2008).

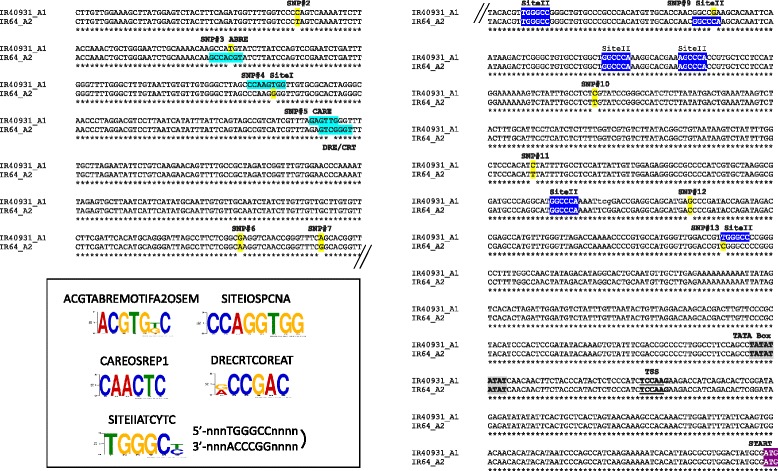

SUB1A promoter analysis

A comparative sequence analysis of the promoter region of the SUB1A-1 and SUB1A-2 alleles (Additional file 2: Table S5) revealed the presence of 13 SNPs. Out of these, 5 SNPs gave rise to allele-specific putative cis-regulatory elements that could be targets of upstream TFs. (Fig. 5; Additional file 3: Figure S2).

Fig. 5.

Comparison between the SUB1A-1 and SUB1A-2 upstream region. The SUB1A-1 and SUB1A-2 upstream regions were aligned and analysed to identify the promoter region and allele-specific putative cis-elements constituted by the thirteen single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Annotation of the putative cis-elements is indicated in the figure and explained in detail in the text. Other relevant promoter elements are additionally indicated. TSS, transcription start site. The complete alignment is provided in Additional file 1: Figure S1

In the SUB1A-1 allele, SNP4, SNP5, and SNP13 create putative motifs (Fig. 5). SNP4 constitutes a Site I (SITEIOSPCNA) motif that resembles the G-box and was discovered in the rice PROLIFERATING CELL NUCLEAR ANTIGEN (PCNA) promoter. Promoter deletion studies had shown that the Site I element is a transcriptional activation site of PCNA and that it is essential for meristematic tissue-specific expression (Kosugi, Suzuka, and Ohashi, 1995). SNP5 resulted in two distinct cis-elements in the two SUB1A alleles (see below) creating a CAREOSREP1 motif in SUB1A-1. This motif was shown to confer GA-mediated increased expression of a proteinase gene in rice seeds (Sutoh and Yamauchi, 2003). SNP13 creates the other constituent of the Site I bipartite motif, i.e., the Site II element (SITEIIATCYTC). This motif was also formed by SNP9 in the SUB1A-2 allele (see below). In addition to PCNA, Site II elements are present in the promoters of many Arabidopsis cell cycle, mitochondrial, ribosomal and cytochrome genes (Tremousaygue et al., 2003; Welchen and Gonzalez, 2005). They are also overrepresented in the promoters of genes encoding nuclear components of the oxidative phosphorylation complex in Arabidopsis and rice (Welchen and Gonzalez, 2005; Welchen and Gonzalez, 2006). Promoter::GUS studies showed that the Site II motif is sufficient to mediate gene expression in shoot and root meristems, as well as in anthers (Kosugi and Ohashi, 1997). It is recognised by TCP and bHLH TFs, which play crucial roles in hormone response pathways, light and abiotic stress responses (Danisman, 2016). Importantly, the position of the Site II element specific to the SUB1A-1 allele is closer to the transcription start site (TSS), which was shown to be the more active position, thus makes this element more relevant in SUB1A-1 allele compared to SUB1A-2, where it is located further upstream (Tremousaygue et al., 2003; Welchen and Gonzalez, 2006).

The Sub1A-2 allele had three SNPs (SNP3, SNP5, SNP9) creating allele-specific putative cis-regulatory elements. SNP3 generates an ABRE motif (ACGTABREMOTIFA2OSEM) in the negative strand, a motif present in many ABA-responsive genes (Hattori, Totsuka, Hobo, Kagaya, and Yamamoto-Toyoda, 2002; Narusaka et al., 2003). SNP5 constitutes the core of the DRE/CRT (dehydration-responsive element/C-repeat; DRECRTCOREAT) motif present in many drought-responsive Arabidopsis and rice genes (Dubouzet et al., 2003; Qin et al., 2004; Diaz-Martin, Almoguera, Prieto-Dapena, Espinosa, and Jordano, 2005; Skinner et al., 2005; Suzuki, Ketterling, and McCarty, 2005). As is the case for SNP13 in the SUB1A-1 allele, SNP9 gave rise to a Site II element (SITEIIATCYTC) but was located further upstream of the TSS as mentioned above.

A third Site II element is present in both alleles (Fig. 5). In addition to Site I and Site II elements, a telo-box (5’-AAACCCTAA-3′) was identified in the PCNA promoters and shown to act as a transcriptional activator (Tremousaygue et al., 2003). In the SUB1A alleles, no perfect match for the telo-box could be found, however, two truncated telo-box motifs (5’-ACCCTA-3′ and 5’-AAACCCT-3′) are present near the SUB1A-2 and SUB1A-1 specific Site II elements, respectively (Fig. 5).

Promoter analysis of the DEGs

The analysis of the 2Kb upstream regions of the DEGs identified 32 distinct motifs present in at least one of the genes (Table 3). These motifs can be categorized into four groups based on their relatedness to hypoxia & light, energy & sugar metabolism, transcription & cell division, and hormones & stress.

Table 3.

Putative cis-elements identified in differentially expressed TF genes

| CATERGORY | MOTIF | IR64 down (#27 genes) | IR64-Sub1 down (#7 genes) | IR64-Sub1 up (#13 genes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoxia & light | GT1CONC4:C36SENSUS | 26 | 7 | 13 |

| ANAERO2CONSENSUS | 18 | 6 | 8 | |

| ANAERO1CONSENSUS | 16 | 5 | 8 | |

| ANAERO3CONSENSUS | 9 | 2 | 4 | |

| ANAERO4CONSENSUS | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Energy | PYRIMIDINEBOXOSRAMY1A | 24 | 7 | 10 |

| TATCCAOSAMY | 17 | 4 | 12 | |

| CGACGOSAMY3 | 16 | 7 | 8 | |

| TATCCAYMOTIFOSRAMY3D | 9 | 1 | 8 | |

| CAREOSREP1 | 23 | 5 | 7 | |

| SITEIIATCYTC | 21 | 5 | 10 | |

| SITEIIBOSPCNA | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| SITEIIAOSPCNA | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| SITEIOSPCNA | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| AACACOREOSGLUB1 | 13 | 3 | 3 | |

| PROLAMINBOXOSGLUB1 | 5 | 1 | 5 | |

| GCN4OSGLUB1 | 8 | 1 | 0 | |

| ACGTOSGLUB1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | |

| GARE1OSREP1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | |

| GARE2OSREP1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | |

| BP5OSWX | 3 | 2 | 2 | |

| Transcription & cell devision | BIHD1OS | 25 | 7 | 12 |

| TATABOXOSPAL | 16 | 4 | 7 | |

| TATABOX1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| E2FCONSENSUS | 13 | 1 | 10 | |

| E2F1OSPCNA | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| LEAFYATAG | 3 | 0 | 4 | |

| WUSATAg | 6 | 0 | 1 | |

| Hormones and stress | DRECRTCOREAT | 17 | 6 | 7 |

| ACGTABREMOTIFA2OSEM | 9 | 4 | 5 | |

| ABREOSRAB21 | 6 | 4 | 2 | |

| IRO2OS | 3 | 1 | 0 |

Under submergence, plants are exposed to hypoxia and low light conditions and in agreement with this, four anaerobic consensus motifs (ANAERO1–4) and the light response motif GT1CONC4:C36SENSUS were found in most DEGs. The anaerobic consensus motifs were previously identified in genes involved in the anaerobic fermentative pathway (Mohanty, Krishnan, Swarup, and Bajic, 2005). The GT1 motif has been found in light-regulated genes and is known to stabilize the TATA box complex (Terzaghi and Cashmore, 1995; Villain, Mache, and Zhou, 1996; Buchel, Brederode, Bol, and Linthorst, 1999; Le Gourrierec, Li, and Zhou, 1999; Zhou, 1999).

Sixteen of the identified motifs were related to energy and sugar metabolism, and studies associated with some of these motifs are detailed below. RAMY motifs, identified in alpha-amylase genes, were highly represented in all four groups of DEGs (up and downregulated DEG in IR64 and IR64-Sub1). The RAMY3D motif (TATCCAY) was found in the rice RAmy3D alpha-amylase gene promoter and is responsible for sugar repression (Toyofuku, T-a, and Yamaguchi, 1998). The AMY3 motif (CGACGO) is present in the GC-rich regions of amylase genes and functions as a coupling element for the G-box element (Hwang, Karrer, Thomas, Chen, and Rodriguez, 1998). The other AMY motif (TATCCA) is a binding site for OsMYBS1, OsMYBS2 and OsMYBS3 TFs, which mediate sugar and hormone regulation of alpha-amylase gene expression (Lu, Lim, and Yu, 1998; Lu, Ho, Ho, and Yu, 2002; Chen, Chiang, Tseng, and Yu, 2006). GARE and CARE motifs are necessary for GA regulation of alpha-amylases genes (Sutoh and Yamauchi, 2003) and the BP5OSWX motif acts as a transcriptional activator in the waxy gene (Zhu, Cai, Wang, and Hong, 2003). The GARE motif was present in about 50% of the IR64-Sub1 upregulated genes and less frequent (15%) in the downregulated genes in both genotypes (Table 3). The GARE and RAMY1A (PYRIMIDINEBOX) motifs participate in sugar repression and are present in the promoter of the rice alpha-amylase gene RAmy1A and the barley alpha-amylase gene Amy2/32b, both of which are GA inducible (Morita et al., 1998; Mena, Cejudo, Isabel-Lamoneda, and Carbonero, 2002). The four identified GLUB1 motifs have been associated with the rice glutelin gene OsGluB-1. They are related to energy metabolism and are proposed to control endosperm-specific expression (Washida et al., 1999; Wu, Washida, Onodera, Harada, and Takaiwa, 2000; Qu, Xing, Liu, Xu, and Song, 2008). Glutelins are primary energy storage proteins and the relevance of these motifs remains to be assessed with respect to submergence response. Site II motifs as detailed above, were also found in most DEGs.

Seven of the identified motifs have been related to transcription (E2F, EF1, and TATA Box), meristems (LEAFYATAG and WUSATAg) and homeotic development (BIHD1OS). The E2F binding site was present in 80% of the IR64-Sub1 upregulated genes and less frequent in the downregulated genes (IR64–50% and IR64-Sub1–10%). E2F TFs are regulators of the cell cycle and can act as transcriptional activators or repressors (Vandepoele et al., 2005). The meristem motifs were rare compared to BIHD1OS, which was present in most DEGs. The BIHD1OS motif has been reported to be the binding site for OsBIHD1, a rice BELL homeodomain TF that integrates ethylene and BR hormonal responses (Liu et al., 2017).

Four of the DEG motifs were associated with hormone and stress responses. The drought-related DRE/CRT and ABA-responsive ABRE motifs were most frequent (Dubouzet et al., 2003; Qin et al., 2004; Diaz-Martin et al., 2005; Skinner et al., 2005; Suzuki et al., 2005), whereas the Fe starvation related motif IRO2 (Ogo et al., 2006) was present in only about 10% of the genes. Amongst the groups of DEGs, DRE/CRT and ABRE motifs were most common in the IR64-Sub1 downregulated genes (60–80%) compared to the other two groups (Table 3).

Discussion

All SUB1A-related studies so far have been conducted using contrasting genotypes with and without the SUB1A gene and, therefore, limited information is available on the differential effect of the two alleles. As a first step, the objective of this study was therefore to assess if different sets of TF genes are regulated by the strong SUB1A-1 allele, as present in IR64-Sub1, and the weaker SUB1A-2 allele, naturally present in the wild-type IR64. An earlier study on a range of rice genotypes had shown that both alleles are highly expressed in nodes of submerged plants, however, differences in the expression level in internodes were most pronounced and correlated best with submergence tolerance (Singh et al., 2010). Therefore, internode tissue was used for this comparative study.

The qPCR analysis of the 2487 TF genes revealed a relatively small number (46) of TF genes that were significantly differentially expressed under submergence. Interestingly, the predominant transcriptional response was reduced expression and only thirteen genes, all in IR64-Sub1, were upregulated under submergence. This, per se, might at least partly explain the higher tolerance level of IR64-Sub1. Further to this, with the exception of an uncharacterized MYB factor, distinct sets of TFs were identified in IR64 and IR64-Sub1, suggesting that the two genotypes employ different regulatory pathways leading to different levels of tolerance.

Association between submergence responsive DEGs and plant hormones

Nineteen TF genes were specifically submergence-responsive in IR64-Sub1, making them candidates to explain the higher tolerance of IR64-Sub1 compared to IR64. The upregulated genes were previously reported in studies on drought, salt and other abiotic stresses, but not with respect to submergence stress (Additional file 2: Table S7). In agreement with our data, the OsbZIP4 and the Zn-finger gene LOC_Os07g43740 were found to be upregulated under anoxia (Ham et al., 2013; Shankar et al., 2016).

Available data on the hormonal response of some of these genes (OsHsfC2a, OsBBX11, OsBBX24, OsWRKY76 and OsTIFY11a) suggest that they are part of the ABA/GA regulatory pathway (Fig. 4). For instance, one of the six upregulated MYB factors (LOC_Os08g06110) was reported to reduce seed dormancy in a rice mutant through ABA-GA antagonism (Wu et al., 2016). OsHsfC2a is downregulated by ABA, while, GA causes downregulation of OsBBX11 and OsBBX24 (Huang et al., 2012). Additionally, OsBBX11 is regulated by light, which plays a critical role in the submergence response (Das et al., 2009).

Among the genes downregulated in IR64-Sub1 were two AP2-type TFs (OsERF136, OsDREB2b), both of which are submergence-responsive in M202 and M202-Sub1 (Jung et al., 2010). Since the wild-type genotype M202 naturally lacks SUB1A, the two AP2 genes might act in a different pathway, independent of SUB1A. DREB2b has also been reported to function as a transcriptional activator under low- and high-temperature stress and it enhances drought tolerance when overexpressed (Matsukura et al., 2010; Todaka et al., 2012). Similarly, SUB1A has been implicated with enhanced recovery growth after severe drought (Fukao et al., 2011) and submerged plants generally survive longer in cooler water (Das et al., 2009). These similarities between SUB1A and DREB2b make the latter an interesting candidate gene for integrating these signal responses.

In contrast to IR64-Sub1, the DEGs in IR64 were all downregulated (Fig. 5). The most highly downregulated gene encodes an uncharacterized protein, with putative Jas- and PHD Zn-finger domains, suggesting that it may be a part of the JA signalling pathway and/or a regulator of development. The second most highly responsive gene was OsSUB1B, followed by WRKY and additional ERF/AP2 factors, including OsSUB1C. Interestingly, both OsSUB1B and OsSUB1C are, despite also in IR64-Sub1, only differentially expressed (downregulated) in IR64. OsSUB1B is non-responsive to GA and ethylene and no tolerant-specific allele has been identified for this gene (Xu et al., 2006). A clear downregulation of OsSUB1B under submergence in IR64 justifies more in-depth analysis of its function and regulation of expression. In contrast, tolerance-specific alleles for OsSUB1C are known and its induction by GA and ethylene specifically in M202-Sub1 has been documented (Fukao et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2006). These studies also indicated that SUB1A-1 might be a negative regulator of OsSUB1C. Downregulation of OsSUB1C in IR64 suggests that the OsSUB1A-2 allele can likewise act as a negative regulator of OsSUB1C, directly or indirectly.

The three AP2/ERF genes downregulated in IR64 (OsERF067, OsERF066, OsERF922) had previously been shown to be upregulated in M202-Sub1 under submergence (Jung et al., 2010). This was not observed in IR64-Sub1 in this study, however, their downregulation in IR64 might at least partly explain a lower level of submergence tolerance. OsERF922 may be of particular interest here since this gene acts as a transcriptional activator and modulator of ABA levels (Liu et al., 2012).

The BBX1 gene had previously been shown to be submergence induced in the variety M202, which lacks the SUB1A gene (Fukao et al., 2011). This is in contrast to the observed downregulation of BBX1 in IR64 in our study, suggesting that BBX1 might be under the control of the SUB1A-2 allele contributing to the higher tolerance level of IR64 compared with M202.

As was the case for IR64-Sub1, a number of the IR64 downregulated DEGs have been associated with GA and ABA regulation. Among the GA-responsive genes, the MYB TF (LOC_Os03g04900) might be of particular interest as it is similar to OsMPS, which acts as a regulator of plant growth by suppressing expansin genes and is downregulated by GA and upregulated by ABA treatment (Schmidt et al., 2013). Suppression of expansins has previously been shown to be a critical component of the SUB1A-mediated quiescence response and it will be interesting to assess if this MYB factor functions in a way similar to OsMPS.

Genes upregulated by ABA (OsMYB2, OsWRKY90, OsERF922 and OsMYB48–1) activate the ABA synthesis pathway and OsMYB48–1, specifically, has been reported to induce other ABA-responsive genes under drought (Xiong et al., 2014). On the other hand, four genes (OsSUB1C, OsBBX1, OsBBX30, OsWRKY62) have antagonistic effects to ABA and respond positively to GA (Ramamoorthy et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2012; Shankar et al., 2016). The fact that all of these genes are downregulated in IR64 under submergence suggests that at least part of the GA signalling pathway is inactivated, as required for submergence tolerance. That these genes have not identified as differentially expressed in IR64-Sub1 is not necessarily a contradiction but instead suggests that submergence tolerance might be related to low or neutral expression of these genes.

Role of iron uptake and JA in submergence tolerance

Iron solubility and availability in plants is altered based on soil pH and submergence conditions and can result in excess iron availability. Difficulties in iron uptake cause chlorosis whereas iron overload or increased uptake leads to oxidative stress and permanent cell and tissue damage (Zheng 2010). One of the four TFs that showed a constitutive difference between the two genotypes, OsIRO2, was constitutively lower expressed in IR64-Sub1 (Fig. 2a). IRO2 has so far only been described in relation to Fe and it was shown to be specifically induced by Fe deficiency (Ogo et al., 2006; Kobayashi et al., 2007). Although the specific role during submergence remains to be determined, the higher expression of the IRO2 in IR64 might suggest a higher Fe uptake in this cultivar resulting in oxidative stress and cell damage.

As expression of IRO2 is not induced by submergence, a specific role for IRO2 is perhaps unlikely, however, it might be possible that the SUB1A-2 allele specifically acts as an enhancer of OsIRO2 thereby causing a secondary, negative effect under submergence. It will, therefore, be interesting to compare the performance of IR64 and IR64-Sub1 under Fe deficiency conditions and quantify plant iron content.

Five of the other TF genes identified in this study (OsTIFY11e, OsTIFY11d, OsWRKY76, OsTIFY11a, OsWRKY71) were reported to be upregulated by JA and downregulated by ABA (Ye et al., 2009; Ranjan et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2015; Shankar et al., 2016). Additionally, WRKY76 and WRKY71 are also upregulated by GA (Ramamoorthy et al., 2008; Shankar et al., 2016). This is well in support of the finding that fine-tuning of GA and ABA levels under submergence is a major component of regulating elongation growth in rice (Fukao et al., 2006; Fukao and Bailey-Serres, 2008) and studies on Arabidopsis have further shown that JA plays a crucial role in protecting plants during post-submergence re-oxygenation (Yuan et al., 2017). The genes identified in this study might therefore play a role in integrating various hormonal signals and analysing their expression in IR64 and IR64-Sub1 plants upon de-submergence will provide more insights into the role of SUB1A-2 during recovery growth.

A significant number of DEGs controlled by submergence have also been described as cold stress responsive. In addition, it has been shown that plant survival in cooler submergence water is higher (Das et al., 2009). Therefore, higher expression of these cold-induced genes in IR64-Sub1 may contribute to its higher tolerance level. For the genes listed in Additional file 2: Table S7, cold responsiveness was also observed in M202 and M202-Sub1 (Jung et al., 2010).

Putative cis-regulatory elements

The diversity of the putative regulatory cis-elements identified in the promoters of the DEGs (Table 3) is well in agreement with the diverse environmental stimuli associated with submergence requiring plants to adjust to low oxygen, light and temperature, alter their energy and sugar metabolism, cell divisions, as well as hormone-regulated growth. For instance, the light-responsive motif (GT1CONC4:C36SENSUS) occurred in all genes except one, suggesting that low-light is an integral signal that can trigger both, up- and downregulation of genes. Likewise, the majority of genes appears to be responsive to hypoxia, as indicated by the presence of the anaerobic consensus motifs, ANAERO1CONSENSUS and ANAERO2CONSENSUS, as well as the PYRIMIDINEBOXOSRAMY1A, found in alpha-amylase genes. The AMY motif (TATCCA) appears to be more frequent in IR64-Sub1 downregulated genes, whereas the AMY3 motifs (CGACG), which functions as a G-box coupling element, is more prevalent in upregulated genes. The former is the binding site of OsMYBs, which mediate sugar and hormone regulation of alpha-amylase genes (Lu et al., 1998; Lu et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2006). Since maintenance of a higher level of soluble sugars has been implicated with tolerance and better recovery growth (Singh et al., 2001; Das et al., 2005; Fukao et al., 2006) these TF genes might be part of the regulatory pathway controlling sugar consumption under submergence. Despite the importance of ABA in submergence tolerance, surprisingly few genes had ABRE elements. In contrast, the DRE/CRT element was more frequent, which, in conjunction with the identified differential expression of DREB2b (Matsukura et al., 2010; Todaka et al., 2012), reinforces a possible relationship between submergence and drought tolerance (Fukao et al., 2011).

Among the most interesting elements identified in the promoter analysis is the bi-partite Site II element. This motif was frequently present in the DEGs and also distinguished the SUB1A-1 and SUB1A-2 alleles at the SNPs (Fig. 5). Since this motif has been implicated with meristem-specific expression (Tremousaygue et al., 2003; Welchen and Gonzalez, 2006) its presence might indicate that control of cell division, in addition to elongation growth, is important for tolerance. This is supported by promoter::GUS reporter studies that showed specific SUB1A-1 expression in the base of growing leaves (Singh et al., 2010). It will be interesting to study this motif in more detail and to determine if the position closer to the TTS of the SUB1A-1-specific Site II element enhances the capacity of tolerant plants to suppress cell division under submergence. In relation to this, it is relevant that the two SUB1A alleles are also distinct in their coding region for a MAPK3 phosphorylation target site, which is specifically present in SUB1A-1 (Singh and Sinha, 2016). The same study also showed that both, SUB1A-1 and SUB1A-2, physically interact with MAPK3 but that the interaction with SUB1A-2 was weaker. Thus, SUB1A-2 would still be a component of this regulatory pathway but might be less efficient. It will indeed be interesting to investigate the role of SUB1A in regulating cell division in more detail and to establish whether SUB1A-2 binds to the MAPK3 promoter, as was shown for SUB1A-1 (Singh and Sinha, 2016).

Conclusion

This study identified distinct sets of submergence-responsive transcription factor genes in IR64 and IR64-Sub1 which might at least partly explain differences in the level of tolerance between the two genotypes. These genes should now be assessed for putative additive effects with SUB1A and their potential to enhance tolerance. The promoter analysis identified allele-specific site II elements, which should be studied in more detail to establish if SUB1A directly or indirectly suppresses cell division, in addition to its documented role in suppressing cell elongation.

Additional files

The submergence tolerance locus Sub1 in rice. The Sub1 locus is located on rice chromosome 9 with a variable number of SUB1 genes. In different rice genotypes, SUB1A is either absent or present as different allele. (a). Introgression of the Sub1 locus into the rice variety IR64 (IR64-Sub1) enhanced survival after complete submergence. (b). The photo shows the IRRI demonstration field plot in the Philippines. Phenotyping for submergence tolerance can also be conducted by submerging plants grown in trays (inlay). The SUB1A-1 and SUB1A-2 alleles are both highly expressed in nodes of submerged plants but SUB1A-1 expression is higher in internodes. (c). Schematic illustration based on (Singh et al., 2010). (PPTX 3066 kb)

Table S1. List of genes represented in Rice TF Primer Platform (Caldana et al., 2007). Complete list of 2508 TF genes, their primer sequences and their corresponding PCR efficiencies. Genes were presented with version 2.0 and version 5.0 RGAP genome annotations. Table S2. Transcription factor genes with and without annotations in version 5.0 and 7.0 of RGAP Pseudomolecule. Table S3. Expression profile of transcription factor genes in IR64 control and stress-treated plants upon submergence. Recorded Ct, R2, Efficiency and ΔCt values for all reactions. The list of used reference genes and their distribution on the plates is also given. Table S4. Expression profile of transcription factor genes in IR64-Sub1 control and stress-treated plants upon submergence. Worksheets record Ct, R2, Efficiency and ΔCt values for all reactions. The list of used reference genes and their distribution on the plates is also given. Table S5. Promoter sequences of SUB1A-1 and SUB1A-2. Table S6. Moderated t-tests results from LIMMA package for identifying differentially expressed genes. P-values were recorded and FDR corrections were also performed. Table S7. Details about the list of differentially expressed genes and their putative functions. (DOCX 29 kb)

Sequence alignment of the SUB1A-1 and SUB1A-2 upstream promoter regions. 2 kb upstream of the start site (promoter regions) were analysed for SUB1A-1 and SUB1A-2 alleles and putative cis-regulatory elements were identified. (XLSX 3.76 kb)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI; Philippines), the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology (Potsdam, Germany), and the University of Potsdam. Rothamsted Research is supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC, UK).

Authors’ contributions

SH designed and supervised the study. BMR has developed and provided access to the qPCR analysis pipeline. TDM and SR performed the experiments, NiS and UB updated and re-analysed the qPCR data. NiS, NaS and SH wrote the manuscript with inputs from UB and BMR. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi: 10.1186/s12284-017-0192-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- Bailey-Serres J, Fukao T, Ronald P, Ismail A, Heuer S, Mackill D. Submergence tolerant Rice: SUB1's journey from landrace to modern cultivar. Rice (N Y) 2010;3(2–3):138–147. doi: 10.1007/s12284-010-9048-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey-Serres J, Voesenek LA. Flooding stress: acclimations and genetic diversity. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:313–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey-Serres J, Voesenek LACJ. Life in the balance: a signaling network controlling survival of flooding. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2010;13(5):489–494. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter CEL, Costa MMR, Coen ES. Diversification and co-option of RAD-like genes in the evolution of floral asymmetry. Plant Journal. 2007;52(1):105–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate - a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc Ser B-Methodological. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Berri S, Abbruscato P, Faivre-Rampant O, Brasileiro AC, Fumasoni I, Satoh K, Kikuchi S, Mizzi L, Morandini P, Pe ME, Piffanelli P. Characterization of WRKY co-regulatory networks in rice and Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2009;9:120. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyden GS, Donoghue MJ, Howarth DG. Duplications and Expression of Radialis-Like Genes in Dipsacales. International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2012;173(9):971–983. doi: 10.1086/667626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buchel AS, Brederode FT, Bol JF, Linthorst HJM. Mutation of GT-1 binding sites in the pr-1A promoter influences the level of inducible gene expression in vivo. Plant Mol Biol. 1999;40(3):387–396. doi: 10.1023/A:1006144505121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldana C, Scheible WR, Mueller-Roeber B, Ruzicic S. A quantitative RT-PCR platform for high-throughput expression profiling of 2500 rice transcription factors. Plant Methods. 2007;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell RP, Reeves TG (2002) The rice genome. The cereal of the world's poor takes center stage. Science 296(5565):53 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chantarachot T, Buaboocha H, Gu H, Chadchawan S. Putative Calmodulin-binding R2R3-MYB transcription factors in Rice (Oryza Sativa L.) Thai J Botany. 2012;4(Special Issue):101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan H, Khurana N, Agarwal P, Khurana P. Heat shock factors in rice (Oryza Sativa L.): genome-wide expression analysis during reproductive development and abiotic stress. Mol Gen Genomics. 2011;286(2):171–187. doi: 10.1007/s00438-011-0638-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PW, Chiang CM, Tseng TH, Yu SM. Interaction between rice MYBGA and the gibberellin response element controls tissue-specific sugar sensitivity of alpha-amylase genes. Plant Cell. 2006;18(9):2326–2340. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.038844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow CN, Zheng HQ, Wu NY, Chien CH, Huang HD, Lee TY, Chiang-Hsieh YF, Hou PF, Yang TY, Chang WC. PlantPAN 2.0: an update of plant promoter analysis navigator for reconstructing transcriptional regulatory networks in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D1154–D1160. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chujo T, Miyamoto K, Shimogawa T, Shimizu T, Otake Y, Yokotani N, Nishizawa Y, Shibuya N, Nojiri H, Yamane H, Minami E, Okada K. OsWRKY28, a PAMP-responsive transrepressor, negatively regulates innate immune responses in rice against rice blast fungus. Plant Mol Biol. 2013;82(1–2):23–37. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danisman S (2016) TCP transcription factors at the Interface between environmental challenges and the Plant's growth responses. Front Plant Sci 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Das KK, Sarkar RK, Ismail AM. Elongation ability and non-structural carbohydrate levels in relation to submergence tolerance in rice. Plant Sci. 2005;168(1):131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.07.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das KK, Panda D, Sarkar RK, Reddy JN, Ismail AM. Submergence tolerance in relation to variable floodwater conditions in rice. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2009;66(3):425–434. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2009.02.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Martin J, Almoguera CN, Prieto-Dapena P, Espinosa JM, Jordano J. Functional interaction between two transcription factors involved in the developmental regulation of a small heat stress protein gene promoter. Plant Physiol. 2005;139(3):1483–1494. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.069963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubouzet JG, Sakuma Y, Ito Y, Kasuga M, Dubouzet EG, Miura S, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. OsDREB genes in rice, Oryza Sativa L., encode transcription activators that function in drought-, high-salt- and cold-responsive gene expression. Plant J. 2003;33(4):751–763. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukao T, Bailey-Serres J. Plant responses to hypoxia--is survival a balancing act? Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9(9):449–456. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukao T, Bailey-Serres J. Submergence tolerance conferred by Sub1A is mediated by SLR1 and SLRL1 restriction of gibberellin responses in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(43):16814–16819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807821105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukao T, Xu K, Ronald PC, Bailey-Serres J. A variable cluster of ethylene response factor-like genes regulates metabolic and developmental acclimation responses to submergence in rice. Plant Cell. 2006;18(8):2021–2034. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.043000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukao T, Yeung E, Bailey-Serres J. The submergence tolerance regulator SUB1A mediates crosstalk between submergence and drought tolerance in rice. Plant Cell. 2011;23(1):412–427. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.080325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao FH, Zhang HL, Wang HG, Gao H, Li ZC. Comparative transcriptional profiling under drought stress between upland and lowland rice (Oryza sativa L.) using cDNA-AFLP. Chinese Science Bulletin. 2009;54(19):3555–3571. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs J, Greenway H. Mechanisms of anoxia tolerance in plants. I. Growth, survival and anaerobic catabolism. Funct Plant Biol. 2003;30(1):1–47. doi: 10.1071/PP98095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham DJ, Moon JC, Hwang SG, Jang CS. Molecular characterization of two small heat shock protein genes in rice: their expression patterns, localizations, networks, and heterogeneous overexpressions. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40(12):6709–6720. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2786-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori T, Totsuka M, Hobo T, Kagaya Y, Yamamoto-Toyoda A. Experimentally determined sequence requirement of ACGT-containing abscisic acid response element. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43(1):136–140. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori Y, Nagai K, Furukawa S, Song XJ, Kawano R, Sakakibara H, Wu JZ, Matsumoto T, Yoshimura A, Kitano H, Matsuoka M, Mori H, Ashikari M. The ethylene response factors SNORKEL1 and SNORKEL2 allow rice to adapt to deep water. Nature. 2009;460(7258):1026–U1116. doi: 10.1038/nature08258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Zhao X, Weng X, Wang L, Xie W. The rice B-box zinc finger gene family: genomic identification, characterization, expression profiling and diurnal analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e48242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang YS, Karrer EE, Thomas BR, Chen L, Rodriguez RL. Three cis-elements required for rice alpha-amylase Amy3D expression during sugar starvation. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;36(3):331–341. doi: 10.1023/A:1005956104636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung KH, Seo YS, Walia H, Cao PJ, Fukao T, Canlas PE, Amonpant F, Bailey-Serres J, Ronald PC. The submergence tolerance regulator Sub1A mediates stress-responsive expression of AP2/ERF transcription factors. Plant Physiol. 2010;152(3):1674–1692. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.152157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katiyar A, Smita S, Lenka SK, Rajwanshi R, Chinnusamy V, Bansal KC. Genome-wide classification and expression analysis of MYB transcription factor families in rice and Arabidopsis. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:544. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara Y, de la Bastide M, Hamilton JP, Kanamori H, McCombie WR, Ouyang S, Schwartz DC, Tanaka T, Wu JZ, Zhou SG, Childs KL, Davidson RM, Lin HN, Quesada-Ocampo L, Vaillancourt B, Sakai H, Lee SS, Kim J, Numa H, Itoh T, Buell CR, Matsumoto T. Improvement of the Oryza Sativa Nipponbare reference genome using next generation sequence and optical map data. Rice (N Y) 2013;6:4. doi: 10.1186/1939-8433-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CY, Vo KTX, Nguyen CD, Jeong DH, Lee SK, Kumar M, Kim SR, Park SH, Kim JK, Jeon JS. Functional analysis of a cold-responsive rice WRKY gene, OsWRKY71. Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2016;10(1):13–23. doi: 10.1007/s11816-015-0383-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Ogo Y, Itai RN, Nakanishi H, Takahashi M, Mori S, Nishizawa NK. The transcription factor IDEF1 regulates the response to and tolerance of iron deficiency in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(48):19150–19155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707010104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosugi S, Ohashi Y. PCF1 and PCF2 specifically bind to cis elements in the rice proliferating cell nuclear antigen gene. Plant Cell. 1997;9(9):1607–1619. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.9.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]