ABSTRACT

The rate of recovery of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) isolates has increased significantly in recent decades in Taiwan. This study investigated the molecular epidemiology of CRAB with a focus on the mechanisms of resistance and spread in isolates with blaOXA-23-like or blaOXA-24-like. All 555 CRAB isolates in our multicenter collection, which were recovered from 2002 to 2010, were tested for the presence of class A, B, and D carbapenemase genes. All isolates with blaOXA-23-like or blaOXA-24-like were subjected to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and 82 isolates (60 isolates with blaOXA-23-like and 22 isolates with blaOXA-24-like) were selected for multilocus sequence typing to determine the sequence type (ST) and clonal group (CG) and for detection of additional β-lactamase and aminoglycoside resistance genes. The flanking regions of carbapenem and aminoglycoside resistance genes were identified by PCR mapping and sequencing. The localization of blaOXA was determined by S1 nuclease and I-CeuI assays. The numbers of CRAB isolates carrying blaOXA-23-like or blaOXA-24-like, especially those carrying blaOXA-23-like, increased significantly from 2008 onward. The blaOXA-23-like gene was carried by antibiotic resistance genomic island 1 (AbGRI1)-type structures located on plasmids and/or the chromosome in isolates of different STs (CG92 and novel CG786), whereas blaOXA-24-like was carried on plasmids in CRAB isolates of limited STs (CG92). No class A or B carbapenemase genes were identified. Multiple aminoglycoside resistance genes coexisted in CRAB. Tn6180-borne armA was found in 74 (90.2%) CRAB isolates, and 58 (70.7%) isolates had Tn6179 upstream, constituting AbGRI3. blaTEM was present in 38 (46.3%) of the CRAB isolates tested, with 35 (92.1%) isolates containing blaTEM in AbGRI2-type structures, and 61% of ampC genes had ISAba1 upstream. We conclude that the dissemination and spread of a few dominant lineages of CRAB containing various resistance island structures occurred in Taiwan.

KEYWORDS: Acinetobacter baumannii, carbapenem resistance, AbGRI, aminoglycoside resistance, transposon

INTRODUCTION

Acinetobacter baumannii has become one of the most important pathogens because of its high prevalence of multidrug resistance, and the rate of recovery of carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii (CRAB) isolates has especially increased worldwide during the past few decades (1–3). CRAB isolates are concomitantly resistant to multiple antibiotics, and infections caused by CRAB are associated with higher rates of mortality and prolonged hospital stays because of limited treatment options and the increased chance of inappropriate therapy (2, 4, 5).

The class D carbapenemases are one of the most important mechanisms responsible for carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter, and of these, OXA-23-like and/or OXA-24-like has commonly been reported to be the most prevalent carbapenemase in many countries (1, 2, 6). Our prior cross-sectional multicenter studies also showed different distributions of carbapenemase genes among geographic regions in Taiwan (7, 8). The rapid acquisition of carbapenem resistance determinants has been attributed to transposons or plasmids (1, 9). The blaOXA-23-like gene is almost always found within a transposon, which is commonly associated with an antibiotic resistance genomic island (AbGRI) (9), and blaOXA-24-like is influenced by clonal spread and sometimes horizontal transfer by plasmids (10). While these cross-sectional studies provided information on and an understanding of the molecular epidemiology and mechanism of carbapenem resistance, little effort was focused on determination of their dynamic changes over time and mechanisms of spread.

The Taiwan Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance (TSAR), a longitudinal multicenter surveillance program, has observed a dramatic increase in the rates of carbapenem resistance among A. baumannii isolates over the years (from 3.4% in 2002 to 58.7% in 2010) (11). Using isolates collected in the TSAR program, the aim of this study was to detail the prevalence of and dynamic changes to the carbapenemase gene in CRAB over the 8-year span and the diverse mechanisms that CRAB strains have adopted to become carbapenem resistant. In addition to carbapenems, A. baumannii can easily acquire resistance to other antibiotics through a variety of mechanisms, especially lateral gene transfer (1, 12–14). For example, insertion of ISAba1 provides promoter activity that drives the overexpression of the downstream AmpC β-lactamases (15). Recent studies also found IS26-mediated recombination events in the antibiotic resistance genomic island to be responsible for the different resistance genes and their variants, including those encoding aminoglycoside resistance, observed in A. baumannii (16, 17). Therefore, the prevalence of determinants of resistance to β-lactams and aminoglycosides and their mechanisms of spread in representative CRAB isolates were also investigated.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

All 555 CRAB isolates were positive for blaOXA-51-like. Among them, 227 (40.9%) had ISAba1-blaOXA-51-like, 292 (52.6%) also had blaOXA-23-like, 59 (10.6%) also had blaOXA-24-like, and 6 (1.1%) also had blaOXA-58-like (see Table S1). The concomitant existence of the carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D β-lactamases (excluding blaOXA-51 without ISAba1 upstream) was found in 40 isolates (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Twelve isolates were negative for all of the four class D β-lactamase genes as well as the blaOXA-143-like and blaOXA-235-like genes. Neither class A (blaNMC, blaSME, blaIMI, blaKPC, and blaGES) nor class B (blaIMP, blaVIM, blaGIM, blaSPM, blaSIM-1, and blaNDM-1) β-lactamase genes with carbapenemase activity were detected.

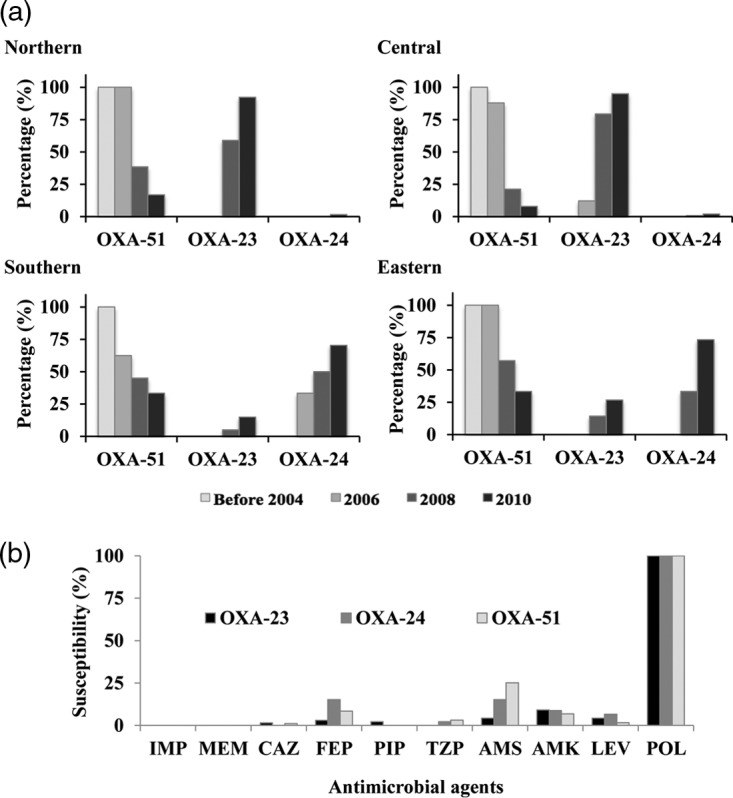

Isolates with ISAba1-blaOXA-51-like comprised all the CRAB isolates recovered in 2002 and 2004 (6 and 45 isolates, respectively), but this proportion decreased to 15.9% (33/208) in 2010 for the whole island of Taiwan. In contrast, isolates with blaOXA-23-like and blaOXA-24-like emerged in 2006, and their prevalence quickly increased, from 4.3% (4/94) and 8.5% (8/94), respectively, in 2006 to 61.4% (124/202) and 8.9% (18/202), respectively, in 2008 and 78.8% (164/208) and 15.9% (33/208), respectively, in 2010 (Table S1) with a regional predominance. By 2010, isolates with blaOXA-23-like comprised >90% of the CRAB isolates from northern and central Taiwan, while those with blaOXA-24-like comprised >70% of the CRAB isolates from southern and eastern Taiwan (Fig. 1a and Table S3). Although isolates with blaOXA-23-like, blaOXA-24-like, or ISAba1-blaOXA-51-like had similar susceptibility profiles (Fig. 1b), the MICs of several other β-lactams, including cefepime and ampicillin-sulbactam, were higher for blaOXA-23-like transformants (Table 1). The contribution of OXA-23 to cefepime resistance was shown a decade ago, with the MICs of cefepime for blaOXA-23 transformants being increased by 8-fold (18). A recent kinetic study also showed that OXA-23 is weakly inhibited by sulbactam (19).

FIG 1.

Secular change of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) carrying specific carbapenemase genes recovered from different regions of Taiwan from 2002 to 2010 (a) and their susceptibility to antibiotics (b). Isolates carrying multiple carbapenemase genes were counted more than once. OXA-51, CRAB isolates with ISAba1-blaOXA-51-like; OXA-23, CRAB isolates with blaOXA-23-like, and OXA-24, CRAB isolates with blaOXA-24-like. IMP, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; CAZ, ceftazidime; FEP, cefepime; TZP, piperacillin-tazobactam; AMS, ampicillin-sulbactam; AMK, amikacin; LEV, levofloxacin; POL, polymyxin B.

TABLE 1.

Susceptibility of transformants with different carbapenemases

| Strain | MIC (mg/liter)a |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMP | MEM | CAZ | FEP | TZP | AMS | AMK | LEV | POL | |

| Wild-type A. baumannii ATCC 15151 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤4 | ≤2 | ≤2 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.5 |

| Wild type with shuttle vector pYMAb2 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤4 | ≤2 | ≤2 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.5 |

| Transformant with ISAba1-blaOXA-23 | 4 | ≥16 | 4 | 32 | ≥128 | 16 | ≤2 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.5 |

| Transformant with blaOXA-72b | 4 | ≥16 | 4 | 2 | ≥128 | 4 | ≤2 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.5 |

| Transformant with ISAba1-blaOXA-82b | 4 | ≥16 | 4 | 2 | ≥128 | ≤2 | ≤2 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.5 |

| Transformant with ISAba1-blaOXA-66b | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | ≥128 | 4 | ≤2 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.5 |

IMP, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; CAZ, ceftazidime; FEP, cefepime; TZP, piperacillin-tazobactam; AMS, ampicillin-sulbactam; AMK, amikacin; LEV, levofloxacin; POL, polymyxin B.

blaOXA-72 is a variant of blaOXA-24-like genes, whereas blaOXA-66 and blaOXA-82 are variants of blaOXA-51-like genes.

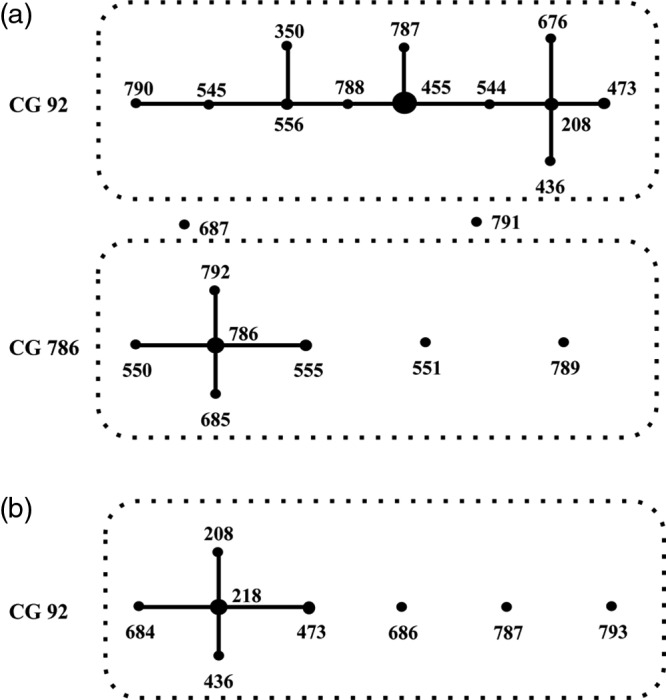

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed on all blaOXA-23-like and blaOXA-24-like-positive CRAB isolates to determine whether their increase was due to clonal spread. The results (not shown) indicated that isolates with blaOXA-23-like belonged to diverse clonal groups (pulsotypes 23A to 23E and multiple other distinct pulsotypes), while those with blaOXA-24-like (pulsotypes 24A to 24C) were less diverse. A total of 82 representative isolates (60 with blaOXA-23-like and 22 with blaOXA-24-like) from different pulsotypes and collection years (Fig. S1) were selected for multilocus sequence typing (MLST). The sources of these isolates are shown in Table 2. eBURST analysis of the MLST data (Fig. 2) showed that the majority of isolates with blaOXA-23-like genes belonged to clonal group 92 (CG92), which is also referred to as international clone II (3, 20, 21). In addition, a new local CG, CG786, was also identified. CG786 includes sequence type 550 (ST550), ST551, ST555, and ST685, as well as three newly assigned STs (ST786, ST789, and ST792). CG92 and CG786 differed in the gltA, cpn60, gpi, and rpoD gene loci. In contrast, isolates with blaOXA-24-like were highly similar, and all belonged to CG92 (international clone II). CC92 has been prevalent in Asia (22), and our study showed that this clone, carrying either blaOXA-23-like or blaOXA-24-like, is also widespread in Taiwan. In contrast, CG786, which appeared in 2006, has limited its spread locally to northern and central Taiwan (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Clinical information and molecular characteristics of selected CRAB isolates with blaOXA-23-like or blaOXA-24-like

| Characteristic | No. (%) of CRAB isolates with: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| blaOXA-23-like | blaOXA-24-like | Overall | |

| Total | 60 | 22 | 82 |

| Period of isolation | |||

| Before 2006 | 2 (3.3) | 5 (22.7) | 7 (8.5) |

| 2008 | 27 (45) | 7 (31.8) | 34 (41.5) |

| 2010 | 31 (51.7) | 10 (45.5) | 41 (50) |

| Hospital level | |||

| Medical center | 19 (31.7) | 9 (40.9) | 28 (34.1) |

| Regional hospital | 41 (68.3) | 13 (59.1) | 54 (65.9) |

| Region of Taiwan | |||

| Eastern | 0 (0) | 4 (18.2) | 4 (4.9) |

| Central | 44 (73.3) | 0 (0) | 44 (53.7) |

| Northern | 16 (26.7) | 1 (4.5) | 17 (20.7) |

| Southern | 0 (0) | 17 (77.3) | 17 (20.7) |

| Specimen source | |||

| Respiratory | 41 (68.3) | 12 (54.5) | 53 (64.6) |

| Pus/discharge | 6 (10) | 5 (22.7) | 11 (13.4) |

| Blood | 4 (6.7) | 1 (4.5) | 5 (6.1) |

| Urine | 7 (11.7) | 2 (9.1) | 9 (11) |

| Others | 2 (3.3) | 2 (9.1) | 4 (4.9) |

| Patient age group | |||

| Adult | 12 (20) | 7 (31.8) | 19 (23.2) |

| Elderly | 42 (70) | 13 (59.1) | 55 (67.1) |

| Pediatric | 1 (1.7) | 2 (9.1) | 3 (3.7) |

| Unknown | 5 (8.3) | 0 (0) | 5 (6.1) |

| Presence of other resistance genes | |||

| armA | 55 (91.7) | 21 (95.5) | 76 (92.7) |

| aphA1 | 52 (86.7) | 20 (90.9) | 72 (87.8) |

| aphA6 | 3 (5) | 1 (4.5) | 4 (4.9) |

| aacC1 | 48 (80) | 20 (90.9) | 68 (82.9) |

| aacA4 | 54 (90) | 20 (90.9) | 74 (90.2) |

| aadB | 0 (0) | 3 (13.6) | 3 (3.7) |

| aadA1 | 58 (96.7) | 21 (95.5) | 79 (96.3) |

| blaTEM | 28 (46.7) | 10 (45.5) | 38 (46.3) |

| ISAba1-ampC | 34 (56.7) | 16 (72.7) | 50 (61) |

| blaSHV | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| blaPER | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

FIG 2.

Clonal groups (CGs) of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates with blaOXA-23-like (a) or blaOXA-24-like (b), determined using eBURST analysis. A CG was defined as a group of STs sharing at least 5 identical loci among the 7 housekeeping genes tested.

Sequencing of the blaOXA-23-like genes from 60 selected isolates showed that they were all blaOXA-23. PCR mapping of Tn2006 was carried out, as previous studies suggested (23). Tn2006 could be embedded in different backbones of Tn6022, which belongs to AbGRI1 (9), and our study showed the presence of at least 2 different Tn6022 constructs, Tn6166 (tniD) and Tn6166 (ΔtniD) (Fig. S2c), which has been found to be widespread in Asia (22). Tn6166 (tniD) was present in 53 isolates, Tn6166 (ΔtniD) was present in 16 isolates, and 11 isolates had both types of Tn6022. The remaining 2 isolates had an unidentified genetic environment flanking Tn2006. The direct repeat flanking Tn2006 was sequenced in 10 isolates with different AbGRI1 types, and in all isolates the sequence was ATTCGCGGG (9), indicative of an AbaR4 structure. S1 nuclease and I-CeuI assays were performed on 22 blaOXA-23 isolates, and blaOXA-23 was located in the chromosomes of 16 isolates and on plasmids in 14 isolates; that is, in 8 isolates, blaOXA-23 could be detected both in the chromosome and on plasmids (Fig. S2a and b). Among the blaOXA-23-carrying plasmids with six different sizes identified, a 90-kbp plasmid was the most prevalent (12 of 22 isolates). Although blaOXA-23-like has been reported to be located either on plasmids or in the chromosome (23), few studies have reported their presence in both. In contrast to the single copy of blaOXA-23-like observed in other studies (22, 24), we detected the carriage of multiple copies of blaOXA-23 by different AbGRI1 types in some of our isolates (Fig. S2a and b). Further investigation of the presence of AbaR4 within AbGRI1 elsewhere in the chromosome or on plasmids is warranted.

The amino acid sequences of the OXA-24-like enzymes in all 22 selected isolates showed that they belonged to OXA-72. An outbreak of CRAB has commonly been attributed to the transmission of various blaOXA-24-like-carrying plasmids (10). Among the blaOXA-72-positive CRAB isolates that we studied, the S1 nuclease assay showed that the blaOXA-72 gene was located in six different patterns on 8 plasmids ranging from 9 to 90 kb in size (Fig. S3). PCR mapping indicated that the sequence of a 9-kb blaOXA-72-carrying plasmid with pattern I was similar to that of a previously reported plasmid carrying blaOXA-24-like (pAB-NCGM253; GenBank accession no. NC_021489.1) (14).

The high prevalence of CRAB with blaOXA-23-like had been repeatedly reported in cross-sectional surveillance studies (1). The present nationwide longitudinal surveillance revealed dynamic changes to isolates with carbapenemase genes over the 8 study years in Taiwan. The exact reason that isolates with blaOXA-23-like replaced those with ISAba1-blaOXA-51-like is unknown. Our findings of the diverse clonality of CRAB carrying blaOXA-23-like, the colocalization of blaOXA-23-like in the chromosome and/or on different plasmids, and the presence of different genetic backgrounds flanking blaOXA-23-like imply the long and successful evolution of these strains in Taiwan. The same direct repeats flanking Tn2006 indicated the importance of clonal expansion in isolates with blaOXA-23-like, with plasmid-borne blaOXA-23-like providing other means of transmission (9). The contribution of OXA-23-like to additional resistance to other β-lactams (Table 1) may also provide some advantages over the overproduction of OXA-51-like. The presence of blaOXA-24-like in plasmids of similar patterns carried by CRAB isolates with the same CG content indicated that their spread was most likely due to clonal dissemination and therefore was limited to certain regions of Taiwan (southern and eastern Taiwan).

We also tested for other β-lactamase genes that have been commonly reported in A. baumannii (Table 2) (1, 2). The blaTEM gene was present in 38 of 82 isolates (46.3%), but no blaSHV or blaPER gene was identified (Table 2). Since the blaTEM gene is usually seen within AbGRI2 or AbGRI3 (25) and since whole-genome sequencing of one of the isolates found its blaTEM to be located within AbGRI2 (data not shown), a PCR targeting this structure was employed, and 35 (92.1%) of the 38 isolates with blaTEM were positive (where blaTEM was found within ABA1_01191Δ-blaTEM-ΔtnpA1000). All 82 isolates also had Acinetobacter AmpC genes (also called Acinetobacter-derived cephalosporinase [blaADC]) since its chromosomal location is inherent to A. baumannii (1, 26). Overproduction of these AmpCs provides A. baumannii intrinsic resistance to penicillins, cephamycins, and even oxyiminocephalosporins (26, 27). Various insertion sequence elements, the most common of which is ISAba1, have been shown to provide strong promoter activity to facilitate overexpression of downstream genes (28). We also found that 50 (61.0%) of our isolates had ISAba1 preceding ampC.

The concomitant existence of several aminoglycoside resistance genes (aphA1, aacA4, aadA1, and armA) was found in our CRAB isolates of different clonalities, indicating the presence of a common genetic structure (Table 2). In A. baumannii, aminoglycoside resistance genes are known to cluster in two separate chromosomal resistance islands, AbGRI2 and AbGRI3 (25, 29). AbGRI2 is an IS26-bound structure containing different resistance mechanisms and has been present in international clone 2 isolates since the 1980s. AbGRI3 was recently discovered in A. baumannii isolates recovered in the early 2000s, and after that genomic island is another IS26-bound structure that contains armA (25, 29). The accumulation of different resistance mechanisms in AbGRI2 and AbGRI3 is attributed to the action of IS26, thus creating the multiple variants reported in the literature (16, 29). AbGRI2 has been well studied and shown to be conserved in all international clone II isolates (25). In contrast, less is known about the recently discovered AbGRI3 (29). Therefore, the present study focused on aminoglycoside resistance genes in AbGRI3. PCR mapping results showed that 74 of 82 tested isolates harbored the Tn6180 segment (29), which contained multiple antimicrobial resistance genes (aacA4, catB8, aadA1, and armA). Among them, 58 isolates had the upstream Tn6179 (IS26, ΔIS26, aphA1b, IS26), which constituted AbGRI3 (24, 29). The wide dissemination of the Tn6180-borne armA or AbGRI3 has also been observed worldwide, especially in Japan and East Asia (14, 24, 29).

In conclusion, this nationwide surveillance study showed the simultaneous acquisition of multiple resistance genes via a variety of mechanisms by CRAB to successfully render the majority of antibiotics ineffective. For carbapenem resistance, the nationwide dissemination of isolates with plasmid-borne and/or chromosomal blaOXA-23-like carbapenemase genes evolved quickly, resulting in different Tn6022 clones of diverse genetic backgrounds. In contrast, isolates with blaOXA-24-like carbapenemase genes carried by plasmids were relatively conserved and confined to some geographic regions. Other resistance determinants (AbGRI3, ISAba1-ampC, or blaTEM) also accumulated in CRAB isolates of different STs to further render CRAB multidrug resistant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolate collection for species identification and antimicrobial testing.

The CRAB isolates were identified from the collection of Acinetobacter isolates recovered as part of the biennial Taiwan Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance (TSAR) program from 2002 to 2010 (corresponding to TSAR III to VII). The isolate collection protocol, the participating hospitals, and antimicrobial susceptibility testing have been described previously (11). The bacterial isolates were recovered from clinical samples taken as part of standard care. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the National Health Research Institutes (EC960205). MICs were determined by a reference broth microdilution method using Sensititre custom-designed plates. Data on the CRAB isolate source are presented in Table S1 in the supplemental material. All CRAB isolates initially identified to be part of the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex by the Vitek I system or Vitek II GN card (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) were further tested to differentiate A. baumannii from A. pittii, A. nosocomialis, and A. calcoaceticus by the gyrB genospecies PCR typing method (30). All isolates were stored at −80C for subsequent testing.

Detection of carbapenemase genes.

PCR was used to detect genes belonging to class A (blaNMC, blaSME, blaIMI, blaKPC, and blaGES,), class B (blaIMP, blaVIM, blaGIM, blaSPM, blaSIM-1, and blaNDM-1), and class D (blaOXA-23-like, blaOXA-24-like, blaOXA-58-like, and blaOXA-51-like,) β-lactamases with carbapenemase activity in all CRAB isolates (31–33). Since ISAba1 facilitates the expression of class D carbapenemase genes, such as blaOXA-23-like or blaOXA-51-like, in addition to the mobilization of resistance determinants, the presence of ISAba1 upstream of the class D carbapenemase gene described above was determined using a reverse primer specific for ISAba1 and a reverse primer specific for the target gene.

Transformation of resistance determinants to confirm their contribution.

The transformation experiment was performed as previously described (15). In brief, the PCR products were amplified with Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland) and confirmed by sequencing. After being cloned into the shuttle vector pYMAb2, electroporation into strain ATCC 15151 was performed with a Gene Pulser electroporator (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and 2-mm-electrode-gap cuvettes. Transformants were selected on the basis of kanamycin resistance, and sequencing was performed to confirm the presence of each resistance gene. The MICs of the transformants were determined by use of a Vitek II system (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France).

Selection of emerging isolates on the basis of PFGE.

All CRAB isolates carrying either blaOXA-23-like or blaOXA-24-like, or both, were subjected to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) after digestion with ApaI as previously described (34). The stained gels were photographed and analyzed using BioNumerics software (Applied Maths), and dendrograms were generated to determine the relatedness of these isolates. Isolates with ≥80% similarity were designated to be in the same cluster (pulsotype). Isolates were selected for the additional studies described below from each PFGE cluster at a ratio of 1/5, and the isolates with the least similarity to the other isolates within each cluster were chosen. If there were fewer than 5 isolates in a cluster, only one isolate was chosen. However, many isolates with a blaOXA-23-like gene were not clustered, and 19 isolates were randomly selected from among these isolates. A total of 82 isolates, including 60 with blaOXA-23-like and 22 with blaOXA-24-like, were selected (Fig. S4).

MLST.

The 82 isolates were subjected to multilocus sequence typing (MLST) according to the Oxford scheme using primers specific for seven housekeeping genes listed on the PubMLST website (https://pubmlst.org/abaumannii/), and the sequences were compared to those in the MLST (Oxford) database. New alleles were designated via the PubMed website (http://pubmlst.org/abaumannii/submission.shtml). The eBURST (v3) algorithm (http://eBURST.mlst.net/) was used to assess the evolutionary relationship of STs. A clonal group (CG) was defined as a group of STs sharing at least 5 identical loci among the 7 housekeeping genes tested.

Detection of genes responsible for resistance to other β-lactams and aminoglycosides and their genetic structure.

The 82 isolates were also tested for the presence of other prevalent class A and C β-lactamase genes (blaTEM, blaPER, blaSHV, and ampC) (35) and genes responsible for aminoglycoside resistance, including the armA, aphA1, aphA6, aacC1, aacA4, aadB, and aadA1genes (36). PCR mapping was further performed on all 82 isolates to elucidate the genetic environment of blaOXA-23-like, blaOXA-24-like (7, 8, 22), or other resistance genes, if present (14, 24, 25). The AbGRI2-like structure in which blaTEM was embedded was detected using primers published previously (25). Sequencing of the PCR products was performed by the DNA Sequencing Core Lab, National Health Research Institutes.

Localization of blaOXA-23-like and blaOXA-24-like.

S1 nuclease and I-CeuI assays were used to determine if the blaOXA-23-like and blaOXA-24-like.genes were present on a plasmid or in the chromosome (37). Among the 82 isolates mentioned above, 44 (22 with blaOXA-23-like and 22 with blaOXA-24-like) were selected (Fig. S4). Briefly, bacterial cells embedded in agarose gel plugs were first digested with S1 nuclease or I-CeuI, followed by PFGE, and then transferred to a nylon membrane. Both the S1 nuclease and I-CeuI digests were hybridized with labeled target genes, and the I-CeuI digests were further hybridized with labeled 23S rRNA genes amplified from our clinical isolates.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We express our sincere appreciation to the following 26 hospitals for their participation in the Taiwan Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance (TSAR): Buddhist Tzu Chi General Hospital, Cathay General Hospital, Changhua Christian Hospital, Cheng-Ching Hospital, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Ditmanson Medical Foundation Chia-Yi Christian Hospital, Far Eastern Memorial Hospital, Hua-Lien Hospital, Jen-Ai Hospital, Kaohsiung Armed Forces General Hospital, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital of the CGMF, Kaohsiung Medical University Chung-Ho Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital, Kuang Tien General Hospital, Lo-Hsu Foundation, Inc.-Lotung Poh-Ai Hospital, Mennonite Christian Hospital, Min-Sheng Healthcare, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Saint Mary's Hospital Luodong, Show Chwan Memorial Hospital, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Tainan Sin-Lau Hospital-the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan, Taipei City Hospital Heping Fuyou Branch, Taipei City Hospital Zhongxiao Branch, Tri-Service General Hospital, and Tungs' Taichung MetroHarbor Hospital.

This project was supported by an intramural grant from the National Health Research Institutes (IV-104-PP-15 and IV-105-PP-01) and the National Science Council (Ministry of Science and Technology; 103-2314-B-400-020-MY2, 105-2628-B-400-002-MY2, and 105-2320-B-038-011).

We have no competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01215-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. 2008. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 21:538–582. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doi Y, Murray GL, Peleg AY. 2015. Acinetobacter baumannii: evolution of antimicrobial resistance-treatment options. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 36:85–98. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1398388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zarrilli R, Pournaras S, Giannouli M, Tsakris A. 2013. Global evolution of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clonal lineages. Int J Antimicrob Agents 41:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwon KT, Oh WS, Song JH, Chang HH, Jung SI, Kim SW, Ryu SY, Heo ST, Jung DS, Rhee JY, Shin SY, Ko KS, Peck KR, Lee NY. 2007. Impact of imipenem resistance on mortality in patients with Acinetobacter bacteraemia. J Antimicrob Chemother 59:525–530. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sunenshine RH, Wright M-O, Maragakis LL, Harris AD, Song X, Hebden J, Cosgrove SE, Anderson A, Carnell J, Jernigan DB, Kleinbaum DG, Perl TM, Standiford HC, Srinivasan A. 2007. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter infection mortality rate and length of hospitalization. Emerg Infect Dis 13:97–103. doi: 10.3201/eid1301.060716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee CR, Lee JH, Park M, Park KS, Bae IK, Kim YB, Cha CJ, Jeong BC, Lee SH. 2017. Biology of Acinetobacter baumannii: pathogenesis, antibiotic resistance mechanisms, and prospective treatment options. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7:55. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuo SC, Yang SP, Lee YT, Chuang HC, Chen CP, Chang CL, Chen TL, Lu PL, Hsueh PR, Fung CP. 2013. Dissemination of imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii with new plasmid-borne bla(OXA-72) in Taiwan. BMC Infect Dis 13:319. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee MH, Chen TL, Lee YT, Huang L, Kuo SC, Yu KW, Hsueh PR, Dou HY, Su IJ, Fung CP. 2013. Dissemination of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii carrying bla(OxA-23) from hospitals in central Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 46:419–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nigro SJ, Hall RM. 2016. Structure and context of Acinetobacter transposons carrying the oxa23 carbapenemase gene. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:1135–1147. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grosso F, Quinteira S, Poirel L, Novais A, Peixe L. 2012. Role of common blaOXA-24/OXA-40-carrying platforms and plasmids in the spread of OXA-24/OXA-40 among Acinetobacter species clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:3969–3972. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06255-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuo SC, Chang SC, Wang HY, Lai JF, Chen PC, Shiau YR, Huang IW, Lauderdale TL, TSAR Hospitals. 2012. Emergence of extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii complex over 10 years: nationwide data from the Taiwan Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance (TSAR) program. BMC Infect Dis 12:200. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saule M, Samuelsen O, Dumpis U, Sundsfjord A, Karlsone A, Balode A, Miklasevics E, Karah N. 2013. Dissemination of a carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strain belonging to international clone II/sequence type 2 and harboring a novel AbaR4-like resistance island in Latvia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1069–1072. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01783-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu LL, Ji SJ, Ruan Z, Fu Y, Fu YQ, Wang YF, Yu YS. 2015. Dissemination of blaOXA-23 in Acinetobacter spp. in China: main roles of conjugative plasmid pAZJ221 and transposon Tn2009. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:1998–2005. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04574-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tada T, Miyoshi-Akiyama T, Shimada K, Shimojima M, Kirikae T. 2014. Dissemination of 16S rRNA methylase ArmA-producing Acinetobacter baumannii and emergence of OXA-72 carbapenemase coproducers in Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:2916–2920. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01212-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuo SC, Lee YT, Yang Lauderdale TL, Huang WC, Chuang MF, Chen CP, Su SC, Lee KR, Chen TL. 2015. Contribution of Acinetobacter-derived cephalosporinase-30 to sulbactam resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Front Microbiol 6:231. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nigro SJ, Farrugia DN, Paulsen IT, Hall RM. 2012. A novel family of genomic resistance islands, AbGRI2, contributing to aminoglycoside resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii isolates belonging to global clone 2. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:554–557. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harmer CJ, Hall RM. 2015. IS26-mediated precise excision of the IS26-aphA1a translocatable unit. mBio 6:e01866-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01866-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mugnier P, Poirel L, Pitout M, Nordmann P. 2008. Carbapenem-resistant and OXA-23-producing Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in the United Arab Emirates. Clin Microbiol Infect 14:879–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shapiro AB. 2017. Kinetics of sulbactam hydrolysis by β-lactamases, and kinetics of β-lactamase inhibition by sulbactam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01612-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01612-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diancourt L, Passet V, Nemec A, Dijkshoorn L, Brisse S. 2010. The population structure of Acinetobacter baumannii: expanding multiresistant clones from an ancestral susceptible genetic pool. PLoS One 5:e10034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomaschek F, Higgins PG, Stefanik D, Wisplinghoff H, Seifert H. 2016. Head-to-head comparison of two multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) schemes for characterization of Acinetobacter baumannii outbreak and sporadic isolates. PLoS One 11:e0153014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim DH, Choi JY, Kim HW, Kim SH, Chung DR, Peck KR, Thamlikitkul V, So TM, Yasin RM, Hsueh PR, Carlos CC, Hsu LY, Buntaran L, Lalitha MK, Song JH, Ko KS. 2013. Spread of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii global clone 2 in Asia and AbaR-type resistance islands. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5239–5246. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00633-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mugnier PD, Poirel L, Naas T, Nordmann P. 2010. Worldwide dissemination of the blaOXA-23 carbapenemase gene of Acinetobacter baumannii. Emerg Infect Dis 16:35–40. doi: 10.3201/eid1601.090852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karah N, Dwibedi CK, Sjostrom K, Edquist P, Johansson A, Wai SN, Uhlin BE. 2016. Novel aminoglycoside resistance transposons and transposon-derived circular forms detected in carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:1801–1818. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02143-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blackwell GA, Nigro SJ, Hall RM. 2015. Evolution of AbGRI2-0, the progenitor of the AbGRI2 resistance island in global clone 2 of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:1421–1429. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02662-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karah N, Jolley KA, Hall RM, Uhlin BE. 2017. Database for the ampC alleles in Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS One 12:e0176695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacoby GA. 2009. AmpC β-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev 22:161–182. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00036-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamidian M, Hall RM. 2013. ISAba1 targets a specific position upstream of the intrinsic ampC gene of Acinetobacter baumannii leading to cephalosporin resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:2682–2683. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blackwell GA, Holt KE, Bentley SD, Hsu LY, Hall RM. 2017. Variants of AbGRI3 carrying the armA gene in extensively antibiotic-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii from Singapore. J Antimicrob Chemother 72:1031–1039. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgins PG, Lehmann M, Wisplinghoff H, Seifert H. 2010. gyrB multiplex PCR to differentiate between Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and Acinetobacter genomic species 3. J Clin Microbiol 48:4592–4594. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01765-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ellington MJ, Kistler J, Livermore DM, Woodford N. 2007. Multiplex PCR for rapid detection of genes encoding acquired metallo-β-lactamases. J Antimicrob Chemother 59:321–322. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Queenan AM, Bush K. 2007. Carbapenemases: the versatile β-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev 20:440–458. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00001-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee Y-T, Kuo S-C, Chiang M-C, Yang S-P, Chen C-P, Chen T-L, Fung C-P. 2012. Emergence of carbapenem-resistant non-baumannii species of Acinetobacter harboring a blaOXA-51-like gene that is intrinsic to A. baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:1124–1127. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00622-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang LY, Chen TL, Lu PL, Tsai CA, Cho WL, Chang FY, Fung CP, Siu LK. 2008. Dissemination of multidrug-resistant, class 1 integron-carrying Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in Taiwan. Clin Microbiol Infect 14:1010–1019. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rezaee MA, Pajand O, Nahaei MR, Mahdian R, Aghazadeh M, Ghojazadeh M, Hojabri Z. 2013. Prevalence of Ambler class A β-lactamases and ampC expression in cephalosporin-resistant isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 76:330–334. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aghazadeh M, Rezaee MA, Nahaei MR, Mahdian R, Pajand O, Saffari F, Hassan M, Hojabri Z. 2013. Dissemination of aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes and 16S rRNA methylases among Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates. Microb Drug Resist 19:282–288. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2012.0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arias CA, Panesso D, Singh KV, Rice LB, Murray BE. 2009. Cotransfer of antibiotic resistance genes and a hylEfm-containing virulence plasmid in Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:4240–4246. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00242-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.