Abstract

BRAF becomes constitutively activated in 50% to 70% of melanoma cases. CEACAM1 has a dual role in melanoma, including facilitation of cell proliferation and suppression of infiltrating lymphocytes, which are consistent with its value as a marker for poor prognosis in melanoma patients. Here we show that BRAFV600E melanoma cells treated with BRAF and MEK inhibitors (MAPKi) downregulate CEACAM1 mRNA and protein expression in a dose- and exposure time–dependent manners. Indeed, there is a significant correlation between the presence of BRAFV600E and CEACAM1 expression in melanoma specimens obtained from 45 patients. Vemurafenib-resistant cell systems reactivate the MAPK pathway and restore basal CEACAM1 mRNA and protein levels. These combined results suggest transcriptional regulation. Indeed, luciferase reporting assays show that CEACAM1 promoter (CEACAM1p) activity is significantly reduced by MAPKi. Importantly, we show that the MAPK-driven CEACAM1p activity is mediated by ETS1, a major transcription factor and downstream effector of the MAPK pathway. Phosphorylation mutant ETS1T38A shows a dominant negative effect over CEACAM1 expression. The data are consistent with independent RNAseq data from serial biopsies of melanoma patients treated with BRAF inhibitors, which demonstrate similar CEACAM1 downregulation. Finally, we show that CEACAM1 downregulation by MAPKi renders the cells more sensitive to T-cell activation. These results provide a new view on a potential immunological mechanism of action of MAPKi in melanoma, as well as on the aggressive phenotype observed in drug-resistant cells.

Introduction

Melanoma accounts for nearly 4% of all skin cancers, and it causes 75% of skin cancer–related deaths worldwide [1]. Disease progression and development of metastasis require stepwise acquisition of aggressive characteristics [2], including resistance to the immune system [3]. In the last years, the US Food and Drug Administration approved anti-CTLA4 mAb (ipilimumab), anti–PD-1 mAbs (nivolumab, pembrolizumab), selective BRAFV600E inhibitors (vemurafenib, dabrafenib), as well as MEK inhibitors (trametinib, cobimetinib) as monotherapies or in combination for the indication of metastatic melanoma. Although these drugs show proven benefit in overall survival [4], [5], [6], the treatment for melanoma is still far from being satisfactory.

Activating BRAF mutations appear early in melanoma development, mostly at the premalignant nevus [7], and cause constitutive activation of the MAPK pathway. Targeting of the MAPK pathway in BRAF-mutant patients yields high response rates with rapid kinetics, leading to an overall survival benefit [8], [9], [10], [11]. This effect is mediated by shutdown of the pathway, as reflected by decreased pERK expression. Unfortunately, in almost all cases, pathway reactivation occurs in the face of the medications via a variety of resistance mechanisms [12], [13], leading to treatment failure and rapid disease progression. Being such a dominant pathway, further understanding of how it is involved in the disease is still warranted.

CEACAM1 is a transmembrane glycoprotein that belongs to the carcinoembryonic antigen family and is encoded on chromosome 19 [14]. The gene gives rise to several alternative splice forms, including a long and short cytosolic tail. CEACAM1 interacts homophilically with CEACAM1 and heterophilically with CEACAM5 but not with other CEACAM proteins [15]. CEACAM1 is expressed on a variety of cells of epithelial and hematological origins, including melanoma and activated lymphocytes [14]. Many different functions have been attributed to the CEACAM1 protein, including antiproliferative properties in carcinomas of the colon and prostate, central involvement of CEACAM1 in angiogenesis and insulin clearance, as well as immune-modulation (reviewed in [14], [16]).

CEACAM1 is deeply involved in the biology of melanoma. Indeed, the presence of CEACAM1 on primary cutaneous melanoma lesions strongly predicts the development of metastatic disease [17], and CEACAM1 expression predicts metastatic spread in melanoma xenograft models in immunodeficient mice [18]. We have previously shown that CEACAM1 is an immune checkpoint in activated NK cells [19], [20], [21] and melanoma-derived tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes [22] and that it is used as an adaptive immune resistance mechanism by melanoma cells [23]. Following these findings, we developed a novel anti-CEACAM1 mAb [24]. Moreover, we found that CEACAM1 expression increases along melanoma development and progression [25], and it directly facilitates the proliferation of melanoma cells [26]. It was also recently reported that CEACAM1 facilitates melanoma cell invasion and metastasis [27]. In addition, increased CEACAM1 expression on peripheral blood lymphocytes and concentration of soluble CEACAM1 in the serum has been observed in melanoma patients [28], with serum CEACAM1 potentially enabling monitoring melanoma patients treated with autologous vaccination [29] or with adoptive cell transfer therapy [30].

Here we report that CEACAM1 expression is associated with mutant BRAF and is regulated by the MAPK pathway at the transcriptional level via the ETS1 transcription factor.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Tissue Culture

The human melanoma lines 526mel and 624mel (obtained from Dr. S.A. Rosenberg, NCI, USA) bear BRAFV600E. BRAFWT 04mel and 076mel were established from surgically removed specimens, as described previously [31]. SKmel-5 and SKmel-2 (ATCC, USA) bear BRAFV600ENRASWT and BRAFWTNRASQ61R, respectively. All melanoma cultures were cultured in standardized supplemented RPMI medium as described previously [31]. Primary melanoma patient-derived tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes culture (TIL14) was established from a surgically excised melanoma specimen (Israel Ministry of Health approval no. 3518/2004) and cultured as previously described [32].

BRAFi- and MEKi-Resistant Cell Lines

526mel and 624mel cells were cultured in the chronic presence of a BRAFV600E inhibitor vemurafenib (PLX4032) or ERK1/2 inhibitor selumetinib (AZD6244, ARRY-142886). The inhibitors were initially added to the culture in ×0.01 IC50. Once a week, the concentration was doubled up to ×10 IC50. Cells with acquired resistance are maintained in 310 nM vemurafenib or 140 nM selumetinib.

Antibodies

MRG1 is a home-made mouse monoclonal antibody specific to human CEACAM1 [24]. Other antibodies used were anti–phospho-p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2) Thr 202/Tyr 204 (Cell Signaling), anti–p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2) (Cell Signaling), and anti-ETS1 antibody [1G11] 10936 (Abcam). FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse polyclonal antibodies were used as secondary reagent in FACS assays (Jaxon Immunoresearch, USA).

Flow Cytometry and Immunoblotting

A total of 100,000 cells were stained using standard extracellular and intracellular flow cytometry staining protocols [24]. Cells were analyzed with FACSCalibur instrument (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software. Lysates of 5×106cells were washed with PBS, lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (Sigma Aldrich), and incubated with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (PMSF 1 mM, sodium orthovanadate 1mM, beta-glycerophosphate 2.5 nM, NaF 5mM, DTT 50 mM), where applicable. Standard immunoblotting protocols were used with specific antibodies and visualized with by standard ECL reaction [33]. Band quantification was determined by densitometry using Image-J software.

RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcription

Total RNA was isolated from Trizol-homogenized cells using Tri Reagent (Sigma Aldrich) extraction method. Integrity of the RNA was determined by spectrophotometry and electrophoresis. The cDNA pools were generated with a high-capacity reverse transcriptase kit (Applied Biosystems) using random hexamer primers.

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Primers were designed using Primer-Express software guidelines (Applied Biosystems) and manufactured by Sigma Aldrich (Supplementary Table 1). The qRT-PCRs were run on LightCycler 480 (Roche) in triplicates. Transcripts were detected using 2× SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche) according to manufacturer’s instructions and were normalized to GAPDH. The list of primers appears in Supplementary Table 1.

Cloning and Mutagenesis

ETS1 isoform 2 was PCR-amplified from cDNA of melanoma cells and cloned into pQCXIP vector (Clontech laboratories, Mountain View, CA) using enzyme restriction sites NotI and PacI (New England Biolabs, MA). The promoter of CEACAM1 (CEACAM1p) cloned into the pGL1.4 luciferase reporting vector was generated previously [26]. ETS1 point mutation at position 38 (ETS1T38A) and deletions of the sequences GGGGGATCCTCCTCCCCT on the negative strand and GCGTTCCTG on the positive strand (putative ETS1 binding sites) from CEACAM1p to create CEACAM1p-ΔETS1(−) and CEACAM1p-DETS1(+), respectively, or both were done using QuikChange Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA), according to manufacturer's protocol. The list of primers appears in Supplementary Table 1. All cloned inserts were fully sequenced (Hylabs Laboratories, Israel).

Quantification of Promoter Activity with Luciferase Assay

To measure the effect of BRAF or MEK inhibitors on CEACAM1 promoter activity, pGL4.14 empty vector, CEACAM1p or CEACAM1p-ΔETS1 constructs were co-transfected with pRL Renilla Luciferase Reporter Vector (Promega, Madison, WI) into melanoma cells in a 50:1 ratio using TurboFect Transfection Reagent (Fermentas, Burlington, Canada) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were incubated with 1 μM of vemurafenib or selumetinib for 48 hours. After 48 hours, cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. To measure the effect of ETS1 on CEACAM1 promoter activity, 293T cells were co-transfected with 10 ng pGL4.14 empty vector or CEACAM1p, together with 100 ng ETS1 or ETS1T38A or mock (pQCXIP), along with 0.4 ng pRL Renilla Luciferase Reporter Vector using TurboFect Transfection Reagent according to manufacturer’s instructions. After 48 hours, cells were lysed and luciferase activity was measured. All assays were measured by Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) using GlowMarx microplate reader (Promega) and normalized to the Renilla signal.

LDH Cytotoxicity Assays

Cytotoxicity assays were performed by measuring lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release using CytoTox-96 (Promega). Briefly, target cells were co-incubated for 18 hours with effector cells at an E:T ratio of 5:1 in a 96-well plate. Wells with target cells only were lysed prior to readout to obtain maximum LDH release. Plates were centrifuged, and 50 μl of supernatants was transferred to a new 96-well plate. Fifty microliters of LDH substrate mix was added to each well, and plates were incubated covered at room temperature for 30 minutes, followed by 50 μl of stop buffer to each well. Optic density was estimated at a wavelength of 490 nm (GlowMax). All experiments were performed in triplicate wells. Percent of specific lysis was calculated using the equation (Experiment-Effector spontaneous − Target spontaneous) / (Target maximum − Target spontaneous) × 100.

Statistics

Significance of effects of specific treatments compared to control was determined by Student’s t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA). Association between two binary parameters was tested with Fisher's exact test. In all graphs, bars represent standard error.

Results

Correlation of CEACAM1 Expression with BRAF-V600E Mutation in Melanoma

The association of BRAF mutation genotype and CEACAM1 expression status, as determined by flow cytometry or qPCR, was tested in 24 low-passage primary cultures of metastatic cutaneous melanoma cell lines [32] and by immunohistochemistry in other 21 metastatic cutaneous melanoma specimens (Table 1). Remarkably, almost all of the CEACAM1-negative melanoma cultures or histological specimens were among the BRAF WT cases (Table 1). These observations could suggest that CEACAM1 expression is controlled by the constitutively activated MAPK pathway.

Table 1.

Association between CEACAM1 Expression and BRAF Mutation Status

| Cell Cultures |

Histopathology |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Type | V600 | Wild Type | V600 | |

| Positive | 3 | 18 | 6 | 9 |

| Negative | 3 | 0 | 5 | 1 |

| P value | 0.009 | 0.06 | ||

CEACAM1 expression status was tested in cell cultures using RT-PCR and flow cytometry, and with immunohistochemistry in tissue specimens. BRAF genotyping was performed by sequencing. Fisher’s exact test was used to determine the statistical significance of the association.

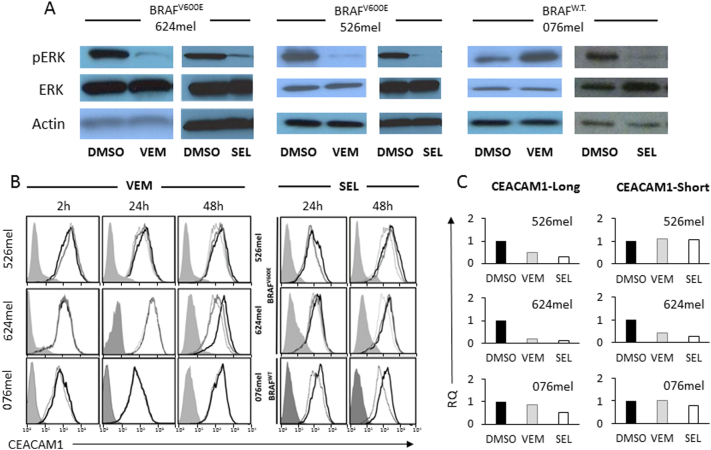

The Effect of MAPK Inhibition on CEACAM1 Expression

BRAFV600E melanoma cells (526mel and 624mel) and BRAFWT melanoma cells (076mel) were incubated in the presence of BRAFV600E inhibitor vemurafenib or the MEK1/2 inhibitor selumetinib. Expectedly, vemurafenib and selumetinib significantly reduced pERK expression among the BRAFV600E melanoma cells (Figure 1A). While vemurafenib had no functional effect on BRAFWT cells and in some cases even resulted in a paradoxical increase in pERK, selumetinib reduced pERK expression in these cells as well (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Inhibition of MAPK pathway downregulates CEACAM1 expression.

The indicated BRAF mutant or wild-type (WT) melanoma cells were incubated with vemurafenib (VEM), selumetinib (SEL), or control (DMSO). (A) The effect of each treatment on pERK. (B) The effect of different doses of each treatment on CEACAM1 expression, as tested by flow cytometry, in each of the melanoma cell lines, in the indicated time points. Shaded histograms represent staining with secondary reagent only. Black histograms represent treatment with DMSO. Gray and dotted histograms represent treatment with 0.1 μM or 1 μM, respectively, of VEM or SEL. (C) The effect of each treatment on CEACAM1 isoform expression (long, short) using RT-PCR. Results are depicted as fold change (RQ) of the DMSO control. Figure shows a representative experiment out of three performed.

Melanoma cells were exposed to the inhibitors for 2, 24, or 48 hours using concentrations of 0.1 μM or 1 μM. Importantly, CEACAM1 expression was downregulated among the BRAFV600E melanoma lines in response to both inhibitors in dose- and exposure time–dependent manners (Figure 1B). Notably, in line with the reduction in pERK expression following exposure to selumetinib (Figure 1A), CEACAM1 was also downregulated in BRAFWT melanoma cells in response to seulmetinib only (Figure 1B). A similar decrease was also observed in intracellular staining, arguing against altered intracellular trafficking as a potential explanation (Supplementary Figure 1). The response to the inhibitors was similarly evident at the mRNA level (Figure 1C). There was no preferential effect on certain CEACAM1 cytoplasmic tail splice variants, suggesting that splicing is unaffected (Figure 1C). Similar results were observed with additional BRAF mutant or wild-type melanoma cells (Supplementary Figure 2). CEACAM1 downregulation was observed also using Western blotting (Supplementary Figure 3). CEACAM1 expression was downregulated in NRAS mutant (Q61R) SK-mel2 cells only following treatment with selumetinib, as vemurafenib had little or no effect (Supplementary Figure 4). Collectively, these results indicate that CEACAM1 expression is controlled by the MAPK pathway at the transcriptional level.

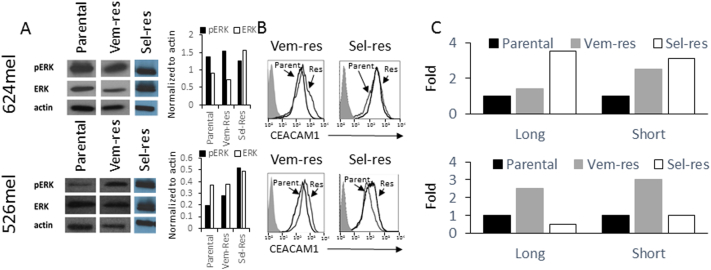

Resistance to MAPK Pathway Inhibitors Restores CEACAM1 Expression

526mel and 624mel cells with acquired resistance to vemurafenib or selumetinib (526VEM, 526SEL, 624VEM, and 624SEL, respectively) were generated by prolonged culturing in increasing concentrations of vemurafenib or selumetinib, as detailed in Materials and Methods. While acute exposure to vemurafenib or selumetinib reduces pERK (Figure 1), its expression was restored or increased in all cells resistant to vemurafenib or selumetinib (Figure 2A). The mechanisms of resistance here are undefined, but the restoration of the MAPK pathway activity was confirmed, which is in line with the outcome of the majority of resistance mechanisms to BRAF or MEK inhibitors [13]. Remarkably, CEACAM1 expression increased in all cells resistant to vemurafenib or selumetinib at the protein level using flow cytometry (Figure 2B) or Western blot (Supplementary Figure 3) and the mRNA level (Figure 2C). There were no significant differences between long and short CEACAM1 isoforms (Figure 2C). These results substantiate the control of CEACAM1 expression by the MAPK pathway at the transcription level.

Figure 2.

Resistance to inhibitors of the MAPK pathway restores CEACAM1 expression.

Vemurafenib-resistant (Vem-Res) and selumetinib-resistant (Sel-Res) sublines of 624mel and 526mel cells were tested. (A) The restored expression of pERK. The graph shows the ratio of each indicated protein as normalized according to actin using densitometry. (B) The restored expression of CEACAM1 using flow cytometry. Shaded histograms represent staining with secondary reagent only. Parental (Parent.) and resistant (Res) histograms are indicated in each panel. (C) The effect of each treatment on CEACAM1 isoform expression (long, short) using. RT-PCR. Results are depicted as fold change (RQ) of the parental cell control. Figure shows a representative experiment out of three performed.

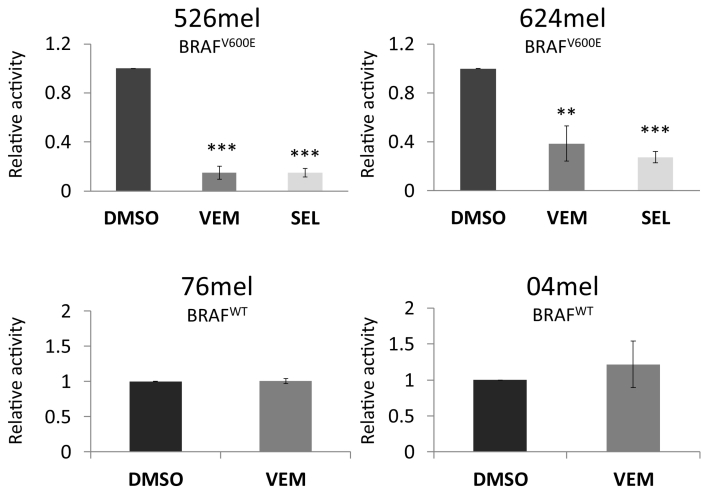

Inhibition of MAPK Pathway Reduces CEACAM1 Promoter Activity in BRAFV600E Melanoma Cells

The promoter of CEACAM1 was cloned upstream to a firefly luciferase reporter gene. Empty vector served as control. Each construct was transiently transfected into BRAFV600E 526mel or 624mel cells, or into BRAFWT 076mel or 04mel cells. Activity was standardized by co-transfection with Renilla luciferase under a constitutive promoter. The different transfectants were exposed to vemurafenib or selumetinib (1 μM, for 48 hours) or to 0.01% DMSO as control. A significant reduction in CEACAM1 promoter activity following treatment with MAPK inhibitors as compared to control treatment was observed exclusively in BRAFV600E cells but not in BRAFWT cells (Figure 3). These experiments confirm that CEACAM1 is controlled by the MAPK pathway at the level of transcription.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of MAPK pathway downregulates the activity of the CEACAM1 promoter.

CEACAM1 promoter was cloned upstream to firefly luciferase and co-transfected into the indicated melanoma cell lines together with a normalizing construct of Renilla luciferase. Empty vector served as negative control. Cells were treated for 2 days with DMSO, or 1 μM vemurafenib (VEM) or selumetinib (SEL). Relative promoter activity was calculated relative to the control (cells transfected with an empty vector and treated with DMSO). Figure shows the average results of four independent experiments. Significance was tested with ANOVA, ** and *** depict P value of <.01 and <.001, respectively.

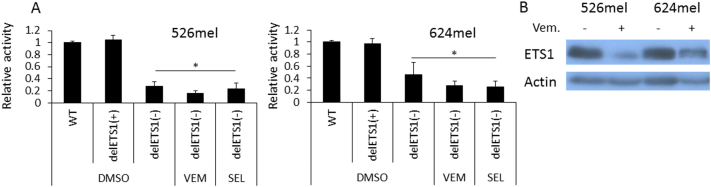

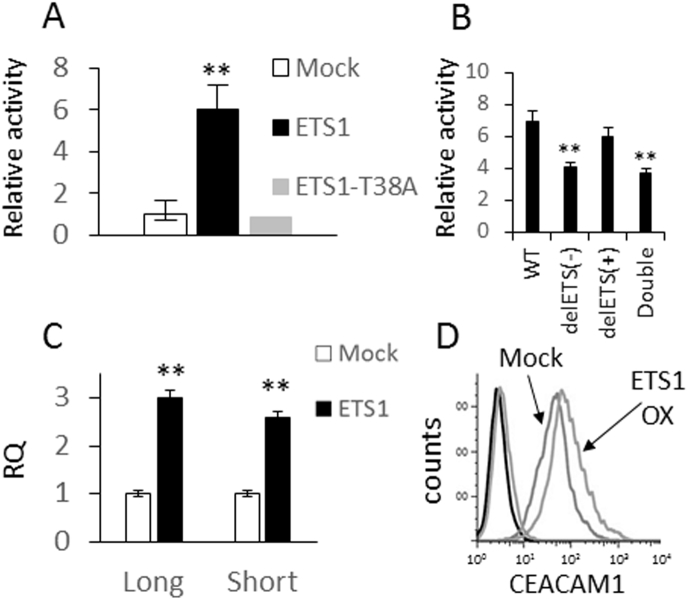

CEACAM1 Promoter Is Controlled by the MAPK Pathway Via ETS1

Bioinformatics prediction with MAPPER tool [34] points to a putative binding site for ETS1 on the negative strand, from which CEACAM1 is transcribed, as well as on the positive strand (Supplementary Figure 5A). ETS1 was recently reported as a potential effector of the MAPK pathway [35] and has known oncogenic roles in various types of cancer, including melanoma [36], [37]. There are no previous reports on the regulation of CEACAM1 by ETS1.

The putative ETS1 binding site was deleted in the CEACAM1p/pGL4.14 promoter construct from the negative strand (CEACAM1p ΔETS1(−)), the positive strand (CEACAM1p ΔETS1(+)), or both (CEACAM1p-ΔETS1(double)). The wild-type CEACAM1p, ΔETS1(−), ΔETS1(+), or mock/pGL4.14 constructs were transiently transfected into BRAFV600E cells (526mel or 624mel) or the BRAFWT cells (076mel). Activity was standardized by co-transfection with Renilla luciferase under a constitutive promoter. A significant reduction in the basal activity of CEACAM1p-ΔETS1(−) but not of CEACAM1p-ΔETS1(+) was evident in BRAFV600E cells as compared to wild-type CEACAM1p activity. This observation suggests that ETS1 positively regulates the promoter activity of CEACAM1 via the binding site on the negative strand (Figure 4A). Some decrease in the basal activity of CEACAM1p-ΔETS1(−) as compared to wild-type CEACAM1p was observed also in BRAFWT 076mel cells, probably reflecting the effect of the endogenous ETS1 in these cells (Supplementary Figure 5B). Remarkably, treatment of BRAFV600E cells with MAPK inhibitors (1uM for 48h) did not further decrease the promoter activity of CEACAM1p-ΔETS1(−) (Figure 4A). Western blot shows that blocking of the MAPK pathway downregulates the expression of ETS1 in these cells (Figure 4B). These collective results suggest that the MAPK pathway regulates the activity of the CEACAM1 promoter via ETS1 by controlling ETS1 expression levels.

Figure 4.

CEACAM1 expression is controlled by the MAPK pathway via the ETS1 transcription factor.

(A) CEACAM1 promoter with a deletion in the putative ETS1 binding site on the negative strand (delETS1(−)), positive strand (delETS1(+)), or the wild-type sequence (WT) was cloned upstream to firefly luciferase and co-transfected into the indicated melanoma cell lines together with a normalizing construct of Renilla luciferase. Empty vector served as negative control. Cells were treated for 2 days with DMSO, or 1 μM vemurafenib (VEM) or selumetinib (SEL). Relative promoter activity was calculated relative to the control (cells transfected with an empty vector and treated with DMSO). Figure shows the average results of four independent experiments. (B) ETS1 expression in the indicated melanoma lines in the presence or absence of vemurafenib. Figure shows a representative experiment out of four independent experiments. Significance was tested with ANOVA, * depicts P value of <.05.

ETS1 Activates the Promoter of CEACAM1

ETS1 isoform analysis in five primary low-passage metastatic melanoma cultures shows that isoform 2 (known as p51/p54) is the dominant form in melanoma (Supplementary Figure 5C), and therefore, it was cloned for subsequent mechanistic studies. The threonine-38 residue, which is important for the Ras-responsive transcriptional activity of ETS1 [38], was mutated to alanine (ETS1-T38A). Co-transfection of WT CEACAM1p into 293T cells with ETS1, but not with ETS1-T38A or with an empty vector, dramatically increased the promoter activity of CEACAM1p (Figure 5A). This observation points to the regulation of CEACAM1 promoter by ETS1 in a way that depends on active phosphorylation of threonine-38. Further, the activity of the CEACAM1p-ΔETS1(−) or CEACAM1p-ΔETS1(double) constructs is substantially less responsive to co-transfection with ETS1 as compared to WT CEACAM1p or CEACAM1p-ΔETS1(+) (Figure 5B). This suggests that ETS1 regulates CEACAM1p only through the putative binding site in the negative DNA strand. The fact that ETS1 still increases to a certain degree the activity of CEACAM1p-ΔETS1 (Figure 5B) suggests that there are additional indirect mechanisms. In line with the promoter experiments, overexpression of ETS1 in melanoma cells moderately but consistently induces CEACAM1 expression at both the mRNA and the protein levels (Figure 5C and D). These collective results show that ETS1 controls CEACAM1 expression at the transcription level.

Figure 5.

ETS1 upregulates the expression of CEACAM1.

(A) CEACAM1 promoter was cloned upstream to firefly luciferase and co-transfected with a normalizing construct of Renilla luciferase, together with a vector encoding for ETS1 (ETS1), mutated ETS1 (ETS1-T38A), or an empty vector (Mock). Relative promoter activity was calculated relative to the effect of transfection with Mock vector. (B) Wild type (WT) or deletions in the putative ETS1 binding site in the negative strand (delETS1(−)), positive strand (delETS1(+)), or both (double) of the CEACAM1 promoter were cloned upstream to firefly luciferase and co-transfected with a normalizing construct of Renilla luciferase, together with a vector encoding for ETS1 (ETS1) or an empty vector (Mock). Data shown are normalized to Mock. (C) The effect of ETS1 (ETS1) compared to an empty vector (Mock) on CEACAM1 isoform (long, short) expression following transfected into melanoma was tested at the mRNA level using RT-PCR. (D) CEACAM1 expression was tested at the protein level using flow cytometry. The histograms of each of the transfectants are indicated in the figure. (A-C) The average results of three independent experiments. Significance was tested with Student’s t test, ** depicts P value of <.01.

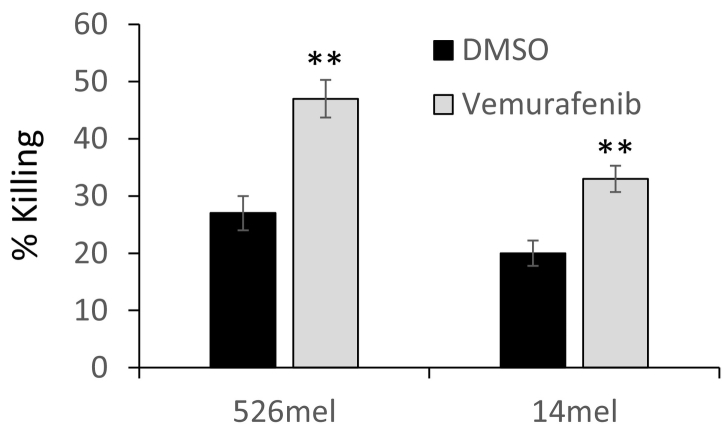

Enhanced Elimination of Vemurafenib-Treated Melanoma Cells by Specific T Cells

526mel and mel14 cells were used as target cells for bulk tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte culture obtained from melanoma patient (TIL14). TIL14 are late effector T cells comprised of more than 97% CD8(+) T cells. They were derived from the same patient as mel14, and we have previously shown that it specifically recognizes 526mel through HLA-A2 [22], [23]. Melanoma cells were exposed to vemurafenib (1 μM; 48 hours) or volume equivalent DMSO and co-cultured with TIL14 for 18 hours in an effector-to-target ratio of 5:1. Remarkably, vemurafenib-treated melanoma cells were significantly more sensitive to T cells than the DMSO-treated cells (Figure 6). This is in line with the reduction in CEACAM1 expression induced by vemurafenib (Figure 1). These experiments suggest that indeed BRAF inhibitors could mediate a local, transient, enhancement of T-cell activity following reduction of immune checkpoint ligands such as CEACAM1.

Figure 6.

Vemurafenib enhances the cytotoxic effect by T cells.

526mel and 14mel cells were treated with vemurafenib (VEM) or DMSO control and then co-cultured for 18 hours with cognate T cells in an E:T ratio of 5:1. Cytotoxicity was measured using LDH release assay. Figure shows the average of three independent experiments. Significance was tested with Student’s t test, ** depicts P value of <.01.

Discussion

CEACAM1 holds a key role in the pathogenesis of metastatic melanoma. It is not expressed on normal melanocytes but becomes upregulated during melanoma development and progression, and is eventually found on the majority of metastatic melanoma cases [25], [26]. Functionally, CEACAM1 protects melanoma cells from both activated NK and T cells by inhibiting their cytotoxic activity [19], [21], [22], [23], and in parallel, it enhances melanoma cell proliferation [26]. These probably account for its prognostic association with poor survival in melanoma [17]. Understanding the regulation of CEACAM1 expression in melanoma is therefore important but still mostly unknown. Here we show for the first time the mechanistic link between the extensively investigated MAPK pathway and the expression of the CEACAM1 protein.

We observed an association between the presence of activating BRAF mutation and the expression of CEACAM1 (Table 1). Selective BRAFV600 inhibition with vemurafenib leads to CEACAM1 downregulation in dose- and time-dependent manners (Figure 1), establishing the mechanistic regulation of CEACAM1 by the MAPK pathway. Similar results were also observed following downstream inhibition of MEK1/2 with selumetinib (Figure 1). This phenomenon was demonstrated with several detection methods and in several melanoma lines of different mutational status (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Figure 2, Supplementary Figure 3, Supplementary Figure 4) to solidify its validity. Interestingly, both CEACAM1 expression on the primary tumor [17] and BRAF V600 mutations [39] are considered as markers of poor prognosis, particularly once the first metastasis is diagnosed.

It should be noted, however, that analysis of CEACAM1 according to BRAF mutational status of the RNAseq data of the 468 tumors in the TCGA collection shows nonstatistically significant trends of a) higher CEACAM1 levels among primary BRAF-mutant melanoma as compared to BRAF-WT and b) an increase in CEACAM1 levels in metastasis as compared to primary tumors in BRAF-WT melanoma but not in BRAF-mutant melanoma cells (data not shown). The lack of conclusive evidence from the TCGA indicates the complexity of CEACAM1 regulation. Indeed, it is regulated by SOX9 [40], AP-2 [41], and IFNg [23], [42]. Importantly, independent in vivo support for CEACAM1 decrease following acute exposure to BRAFi was obtained from a recently published RNAseq database of serial melanoma biopsies before and during response to vemurafenib, dabrafenib, or combined BRAF and MEK inhibitors [43]. Indeed, CEACAM1 was downregulated in 50% of the patients by at least two-fold, and in 43% of them, a concomitant downregulation in ETS1 mRNA by at least two-fold was observed [43]. Reestablishment of MAPK signaling in different BRAFi- or MEKi-resistant melanoma lines is coupled with restored CEACAM1 expression (Figure 2). Albeit the exact resistance mechanism to BRAFi and MEKi in our melanoma cells has not been determined, reestablishment of MAPK signaling is visible by pERK upregulation (Figure 2). In the independent RNAseq data, CEACAM1 mRNA was still downregulated upon disease progression but to a lesser extent than during response [43]. The differences between this data set and our in vitro results may be explained by tumor heterogeneity in biopsies versus in vitro straightforward cell line data. Another possibility is the difference between mRNA and protein measurements, as the effect of mRNA quantities on protein quantities cannot be easily extrapolated.

Functionally, BRAF inhibition has a dominant and direct effect on cell survival and proliferation, which probably overshadows the effect of reduced CEACAM1 on proliferation. Nevertheless, we show that acute exposure of melanoma cells to BRAF inhibitors renders melanoma cells more sensitive to cognate T cells (Figure 6), concurring with the downregulation in CEACAM1 levels (Figure 1) and its known T-cell–suppressive effect [21], [22], [23], [24]. This observation is in line with previous reports that BRAF inhibition may result in immune sensitization, albeit transient [44]. The CEACAM1 downregulation observed in the RNAseq data in MAPK inhibitor-treated patients supports this direction [43]. It should be noted that the expression of PD-L1 in melanoma cells is variably regulated following treatment with BRAF inhibitors [45]. As melanoma cells hardly express PD-L1 in vitro (unpublished data) unless stimulated with interferons, it does not seem plausible that the enhanced immune sensitivity observed here can be accounted for by PD-L1 downregulation. Importantly, it was recently demonstrated that disease progression on MAPK inhibitors is associated in at least half of the cases with CD8(+) T-cell deficiency. RNAseq demonstrated reduced antigen presentation, cytolytic function, and exhaustion markers on T-cell subset [43]. It would be interesting to study in the future the expression of CEACAM1 on these cells in such specimens. Taken together, it seems that CEACAM1 downregulation following patient therapy with BRAF inhibitors may contribute to a transiently facilitated immune-mediated effect against the melanoma cells; however, in the face of a frequent subsequent T-cell depletion, further studies are needed to determine a scientific rationale for combination therapies.

We show that CEACAM1 expression is controlled by the MAPK pathway at the transcriptional level (Figure 3) and provide evidence that this is mediated by ETS1 transcription factor. ETS1 is an important oncogenic factor in various types of cancer [36], including melanoma [37], [46], [47], [48]. It was previously published that ETS1 phosphorylation at T38 by ERK1/2 increases its transcriptional activity [49]. Here we show that deletion of the putative ETS1 binding site within the CEACAM1 promoter abrogates the effect of MAPK inhibition (Figure 4). In line with the previous report [49], mutation at the critical phosphorylation site T38 within ETS1 eliminates its ability to induce CEACAM1 promoter activity (Figure 5). In addition, we show that inhibition of the MAPK pathway downregulates ETS1 expression (Figure 4). This suggests that the MAPK pathway controls ETS1-mediated effects at both the expression and function levels. ETS1 similarly induces both long and short isoforms of CEACAM1 (Figure 5), suggesting no effect on splicing of the transcribed mRNA. This is in agreement with the effects of MAPK inhibitors on CEACAM1 isoform expression (Figures 1 and 2).

We have previously published that the rare, highly linked germline alleles of SNPs rs8103285 and rs8102519 within the promoter of CEACAM1 dramatically enhance the activity of CEACAM1 promoter and are associated with melanoma (allelic OR of 2.05), and that homozygosity to these alleles confers an increased risk to melanoma (RR of 1.35, 95% CI: 1.01-1.81, p=0.05) [26]. Strikingly, this genotype generates a new putative binding site for ETS1, which could explain the promoter hyperactivity. Taking into account that CEACAM1 facilitates melanoma proliferation [26] and as the activating BRAF mutation is acquired along melanoma transformation at the premalignant stage, it may particularly increase the risk for melanoma among individuals with this SNP genotype. Further genetic analyses are required to establish the clinical link between this genotype and BRAF mutation, but as it is a rare genotype, this can only be tested in large patient cohorts.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

CEACAM1 intracellular staining of vemurafenib- or selumetinib-treated melanoma cells. In order to understand in more detail the nature of reduction in CEACAM1 expression due to the inhibitors exposure, the intracellular amounts of total CEACAM1 were tested. 526mel and 624mel cells (BRAF mutant) were incubated at the optimal dosing determined (1 μM, 48 hours) of vemurafenib or selumetinib. Treated cells were analyzed for CEACAM1 protein expression by intracellular flow cytometry staining: background (gray), 0.01% DMSO as control (black line), 0.1 μM selumetinib (dark gray dashed line),1 μM vemurafenib (dark gray dotted line). Figure shows a representative experiment out of three performed. Staining in this technique is weaker than the extracellular stains (Figure 2), probably due to inherent technical reasons. Nevertheless, it is still evident that the total intracellular staining of CEACAM1 was downregulated in BRAFV600E melanoma lines in response to both vemurafenib and selumetinib. This suggests that the downregulation of CEACAM1 expression following MAPK inhibition is not the result of subcellular redistribution of the protein but rather is a true effect on protein quantity.

Inhibition of MAPK downregulates CEACAM1 expression: additional cell lines. The effect of selective MAPK inhibition was tested in additional cell lines. BRAF-mutant (Skmel-5) and wild-type (013mel) melanoma cells were exposed for 48 hours to 1 μM vemurafenib (VEM) or volume and concentration equivalent of DMSO. CEACAM1 expression was tested with flow cytometry. Shaded histograms: secondary reagent only; black line: DMSO-treated cells; dotted line: vemurafenib-treated cells. The effect of vemurafenib was verified by testing pERK and total ERK using antibody-specific immunoblotting. Actin served as housekeeping gene. The results here concur with those depicted in Figure 2.

MAPK pathway controls CEACAM1 expression at the protein level: immunoblotting. The effect of selective MAPK inhibition was tested in additional methods (immunoblotting). CEACAM1 expression was tested using immunoblotting with specific mAb in BRAF-mutant 526mel melanoma cells that were exposed for 48 hours to 1 μM vemurafenib (VEM), selumetinib (SEL), or volume and concentration equivalent of DMSO. In addition, 526mel vemurafenib resistance (Vem Res) cells were tested as well. Actin served as housekeeping control. Figure shows a representative blot.

MAPK pathway controls CEACAM1 expression at the protein level: NRAS mutant cell line. The effect of selective MAPK inhibition was tested in NRAS mutant cell line. CEACAM1 expression was tested using flow cytometry in NRAS-mutant Skmel-2 melanoma cells that were exposed for 48 hours to 1 μM vemurafenib, selumetinib, or volume and concentration equivalent of DMSO. Figure shows a representative experiment.

(A) The prediction of putative binding sites for various transcription factors within the CEACAM1 promoter. ETS-1 is highlighted by red box. (B) Minor effect on the CEACAM1 promoter activity following deletion of the ETS-1 putative binding site, as compared to the wild-type promoter, when tested in BRAF-WT cells. Promoter activity was tested with standardized luciferase experiments. The expression of ETS1 was verified with immunoblotting. (C) Isoform specific real-time PCR shows the dominance of isoform-2 of ETS1 in various melanoma lines.

List of Specific Primers Used for qPCR, Cloning, and Mutagenesis

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Lemelbaum Family and the Aronson Fund for their generous support. This study was made in partial fulfilment of KK’s thesis.

Footnotes

Funding: G. M. is supported by grants from the Israel Science Foundation15/1925 and from the Israel Ministry of Health.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller AJ, Mihm MC., Jr. Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:51–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gajewski TF. Failure at the effector phase: immune barriers at the level of the melanoma tumor microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5256–5261. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, Nathan P, Garbe C, Milhem M, Demidov LV, Hassel JC, Rutkowski P, Mohr P. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:107–114. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, O'Day S, M DJ, Garbe C, Lebbe C, Baurain JF, Testori A, Grob JJ. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2517–2526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sang M, Wang L, Ding C, Zhou X, Wang B, Lian Y, Shan B. Melanoma-associated antigen genes - an update. Cancer Lett. 2011;302:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pollock PM, Harper UL, Hansen KS, Yudt LM, Stark M, Robbins CM, Moses TY, Hostetter G, Wagner U, Kakareka J. High frequency of BRAF mutations in nevi. Nat Genet. 2003;33:19–20. doi: 10.1038/ng1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flaherty KT, Infante JR, Daud A, Gonzalez R, Kefford RF, Sosman J, Hamid O, Schuchter L, Cebon J, Ibrahim N. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1694–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, Ribas A, McArthur GA, Sosman JA, O'Dwyer PJ, Lee RJ, Grippo JF, Nolop K. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:809–819. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, Jouary T, Gutzmer R, Millward M, Rutkowski P, Blank CU, Miller WH, Jr., Kaempgen E. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:358–365. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60868-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sosman JA, Kim KB, Schuchter L, Gonzalez R, Pavlick AC, Weber JS, McArthur GA, Hutson TE, Moschos SJ, Flaherty KT. Survival in BRAF V600-mutant advanced melanoma treated with vemurafenib. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:707–714. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johannessen CM, Johnson LA, Piccioni F, Townes A, Frederick DT, Donahue MK, Narayan R, Flaherty KT, Wargo JA, Root DE. A melanocyte lineage program confers resistance to MAP kinase pathway inhibition. Nature. 2013;504:138–142. doi: 10.1038/nature12688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villanueva J, Vultur A, Lee JT, Somasundaram R, Fukunaga-Kalabis M, Cipolla AK, Wubbenhorst B, Xu X, Gimotty PA, Kee D. Acquired resistance to BRAF inhibitors mediated by a RAF kinase switch in melanoma can be overcome by cotargeting MEK and IGF-1R/PI3K. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:683–695. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray-Owen SD, Blumberg RS. CEACAM1: contact-dependent control of immunity. Nat Rev. Immunol. 2006;6:433–446. doi: 10.1038/nri1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markel G, Gruda R, Achdout H, Katz G, Nechama M, Blumberg RS, Kammerer R, Zimmermann W, Mandelboim O. The critical role of residues 43R and 44Q of carcinoembryonic antigen cell adhesion molecules-1 in the protection from killing by human NK cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:3732–3739. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sapoznik S, Ortenberg R, Schachter J, Markel G. CEACAM1 in malignant melanoma: a diagnostic and therapeutic target. Curr Top Med Chem. 2012;12:3–10. doi: 10.2174/156802612798919259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thies A, Moll I, Berger J, Wagener C, Brummer J, Schulze HJ, Brunner G, Schumacher U. CEACAM1 expression in cutaneous malignant melanoma predicts the development of metastatic disease. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2530–2536. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thies A, Mauer S, Fodstad O, Schumacher U. Clinically proven markers of metastasis predict metastatic spread of human melanoma cells engrafted in SCID mice. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:609–616. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markel G, Lieberman N, Katz G, Arnon TI, Lotem M, Drize O, Blumberg RS, Bar-Haim E, Mader R, Eisenbach L. CD66a interactions between human melanoma and NK cells: a novel class I MHC-independent inhibitory mechanism of cytotoxicity. J Immunol. 2002;168:2803–2810. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Markel G, Mussaffi H, Ling KL, Salio M, Gadola S, Steuer G, Blau H, Achdout H, de Miguel M, Gonen-Gross T. The mechanisms controlling NK cell autoreactivity in TAP2-deficient patients. Blood. 2004;103:1770–1778. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markel G, Wolf D, Hanna J, Gazit R, Goldman-Wohl D, Lavy Y, Yagel S, Mandelboim O. Pivotal role of CEACAM1 protein in the inhibition of activated decidual lymphocyte functions. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:943–953. doi: 10.1172/JCI15643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markel G, Seidman R, Stern N, Cohen-Sinai T, Izhaki O, Katz G, Besser M, Treves AJ, Blumberg RS, Loewenthal R. Inhibition of human tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte effector functions by the homophilic carcinoembryonic cell adhesion molecule 1 interactions. J Immunol. 2006;177:6062–6071. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markel G, Seidman R, Cohen Y, Besser MJ, Sinai TC, Treves AJ, Orenstein A, Berger R, Schachter J. Dynamic expression of protective CEACAM1 on melanoma cells during specific immune attack. Immunology. 2009;126:186–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02888.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ortenberg R, Sapir Y, Raz L, Hershkovitz L, Ben Arav A, Sapoznik S, Barshack I, Avivi C, Berkun Y, Besser MJ. Novel immunotherapy for malignant melanoma with a monoclonal antibody that blocks CEACAM1 homophilic interactions. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:1300–1310. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zippel D, Barlev H, Ortenberg R, Barshack I, Schachter J, Markel G. A longitudinal study of CEACAM1 expression in melanoma disease progression. Oncol Rep. 2015;33:1314–1318. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ortenberg R, Galore-Haskel G, Greenberg I, Zamlin B, Sapoznik S, Greenberg E, Barshack I, Avivi C, Feiler Y, Zan-Bar I. CEACAM1 promotes melanoma cell growth through Sox-2. Neoplasia. 2014;16:451–460. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Löffek S, Ullrich N, Görgens A, Murke F, Eilebrecht M, Menne C, Giebel B, Schadendorf D, Singer BB, Helfrich I. CEACAM1-4L promotes anchorage-independent growth in melanoma. Front Oncol. 2015;5:234. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00234. [eCollection 2015] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Markel G, Ortenberg R, Seidman R, Sapoznik S, Koren-Morag N, Besser MJ, Bar J, Shapira R, Kubi A, Nardini G. Systemic dysregulation of CEACAM1 in melanoma patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59:215–230. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0740-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sivan S, Suzan F, Rona O, Tamar H, Vivian B, Tamar P, Jacob S, Gal M, Michal L. Serum CEACAM1 correlates with disease progression and survival in malignant melanoma patients. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:290536. doi: 10.1155/2012/290536. [Epub 2012 Jan 16] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ortenberg R, Sapoznik S, Zippel D, Shapira-Frommer R, Itzhaki O, Kubi A, Zikich D, Besser MJ, Schachter J, Markel G. Serum CEACAM1 elevation correlates with melanoma progression and failure to respond to adoptive cell transfer immunotherapy. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:290536. doi: 10.1155/2015/902137. [Epub 2012 Jan 16] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Shelton TE, Even J, Rosenberg SA. Generation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte cultures for use in adoptive transfer therapy for melanoma patients. J Immunother. 2003;26:332–342. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200307000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Besser MJ, Shapira-Frommer R, Itzhaki O, Treves AJ, Zippel DB, Levy D, Kubi A, Shoshani N, Zikich D, Ohayon Y. Adoptive transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with metastatic melanoma: intent-to-treat analysis and efficacy after failure to prior immunotherapies. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:4792–4800. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nemlich Y, Greenberg E, Ortenberg R, Besser MJ, Barshack I, Jacob-Hirsch J, Jacoby E, Eyal E, Rivkin L, Prieto VG. MicroRNA-mediated loss of ADAR1 in metastatic melanoma promotes tumor growth. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2703–2718. doi: 10.1172/JCI62980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marinescu VD, Kohane IS, Riva A. The MAPPER database: a multi-genome catalog of putative transcription factor binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D91–D97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plotnik JP, Budka JA, Ferris MW, Hollenhorst PC. ETS1 is a genome-wide effector of RAS/ERK signaling in epithelial cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:11928–11940. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dittmer J. The biology of the Ets1 proto-oncogene. Mol Cancer. 2003;2:29–50. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-2-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kubic JD, Little EC, Lui JW, Iizuka T, Lang D. PAX3 and ETS1 synergistically activate MET expression in melanoma cells. Oncogene. 2015;34(38):4964–4974. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.420. [Epub 2014 Dec 22] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang BS, Hauser CA, Henkel G, Colman MS, Van Beveren C, Stacey KJ, Hume DA, Maki RA, Ostrowski MC. Ras-mediated phosphorylation of a conserved threonine residue enhances the transactivation activities of c-Ets1 and c-Ets2. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:538–547. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.2.538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Long GV, Menzies AM, Nagrial AM, Haydu LE, Hamilton AL, Mann GJ, Hughes TM, Thompson JF, Scolyer RA, Kefford RF. Prognostic and clinicopathologic associations of oncogenic BRAF in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1239–1246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ashkenazi S, Ortenberg R, Besser MJ, Schachter J, Markel G. SOX9 indirectly regulates CEACAM1 expression and immune resistance in melanoma cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7:30166–30177. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nédellec P, Turbide C, Beauchemin N. Characterization and transcriptional activity of the mouse biliary glycoprotein 1 gene, a carcinoembryonic antigen-related gene. Eur J Biochem. 1995;231:104–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen CJ, Lin TT, Shively JE. Role of interferon regulatory factor-1 in the induction of biliary glycoprotein (cell CAM-1) by interferon-gamma. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28181–28188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hugo W, Shi H, Sun L, Piva M, Song C, Kong X, Moriceau G, Hong A, Dahlman KB, Johnson DB. Non-genomic and immune evolution of melanoma acquiring MAPKi resistance. Cell. 2015;162:1271–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boni A, Cogdill AP, Dang P, Udayakumar D, Njauw CN, Sloss CM, Ferrone CR, Flaherty KT, Lawrence DP, Fisher DE. Selective BRAFV600E inhibition enhances T-cell recognition of melanoma without affecting lymphocyte function. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5213–5219. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Atefi M, Avramis E, Lassen A, Wong DJ, Robert L, Foulad D, Cerniglia M, Titz B, Chodon T, Graeber TG. Effects of MAPK and PI3K pathways on PD-L1 expression in melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:3446–3457. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dong L, Jiang CC, Thorne RF, Croft A, Yang F, Liu H, de Bock CE, Hersey P, Zhang XD. Ets-1 mediates upregulation of Mcl-1 downstream of XBP-1 in human melanoma cells upon ER stress. Oncogene. 2011;30:3716–3726. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rothhammer T, Hahne JC, Florin A, Poser I, Soncin F, Wernert N, Bosserhoff AK. The Ets-1 transcription factor is involved in the development and invasion of malignant melanoma. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:118–128. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3337-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tajima A, Miyamoto Y, Kadowaki H, Hayashi M. Mouse integrin alphav promoter is regulated by transcriptional factors Ets and Sp1 in melanoma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1492:377–384. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(00)00121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mattia G, Errico MC, Felicetti F, Petrini M, Bottero L, Tomasello L, Romania P, Boe A, Segnalini P, Di Virgilio A. Constitutive activation of the ETS-1-miR-222 circuitry in metastatic melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011;24:953–965. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2011.00881.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

CEACAM1 intracellular staining of vemurafenib- or selumetinib-treated melanoma cells. In order to understand in more detail the nature of reduction in CEACAM1 expression due to the inhibitors exposure, the intracellular amounts of total CEACAM1 were tested. 526mel and 624mel cells (BRAF mutant) were incubated at the optimal dosing determined (1 μM, 48 hours) of vemurafenib or selumetinib. Treated cells were analyzed for CEACAM1 protein expression by intracellular flow cytometry staining: background (gray), 0.01% DMSO as control (black line), 0.1 μM selumetinib (dark gray dashed line),1 μM vemurafenib (dark gray dotted line). Figure shows a representative experiment out of three performed. Staining in this technique is weaker than the extracellular stains (Figure 2), probably due to inherent technical reasons. Nevertheless, it is still evident that the total intracellular staining of CEACAM1 was downregulated in BRAFV600E melanoma lines in response to both vemurafenib and selumetinib. This suggests that the downregulation of CEACAM1 expression following MAPK inhibition is not the result of subcellular redistribution of the protein but rather is a true effect on protein quantity.

Inhibition of MAPK downregulates CEACAM1 expression: additional cell lines. The effect of selective MAPK inhibition was tested in additional cell lines. BRAF-mutant (Skmel-5) and wild-type (013mel) melanoma cells were exposed for 48 hours to 1 μM vemurafenib (VEM) or volume and concentration equivalent of DMSO. CEACAM1 expression was tested with flow cytometry. Shaded histograms: secondary reagent only; black line: DMSO-treated cells; dotted line: vemurafenib-treated cells. The effect of vemurafenib was verified by testing pERK and total ERK using antibody-specific immunoblotting. Actin served as housekeeping gene. The results here concur with those depicted in Figure 2.

MAPK pathway controls CEACAM1 expression at the protein level: immunoblotting. The effect of selective MAPK inhibition was tested in additional methods (immunoblotting). CEACAM1 expression was tested using immunoblotting with specific mAb in BRAF-mutant 526mel melanoma cells that were exposed for 48 hours to 1 μM vemurafenib (VEM), selumetinib (SEL), or volume and concentration equivalent of DMSO. In addition, 526mel vemurafenib resistance (Vem Res) cells were tested as well. Actin served as housekeeping control. Figure shows a representative blot.

MAPK pathway controls CEACAM1 expression at the protein level: NRAS mutant cell line. The effect of selective MAPK inhibition was tested in NRAS mutant cell line. CEACAM1 expression was tested using flow cytometry in NRAS-mutant Skmel-2 melanoma cells that were exposed for 48 hours to 1 μM vemurafenib, selumetinib, or volume and concentration equivalent of DMSO. Figure shows a representative experiment.

(A) The prediction of putative binding sites for various transcription factors within the CEACAM1 promoter. ETS-1 is highlighted by red box. (B) Minor effect on the CEACAM1 promoter activity following deletion of the ETS-1 putative binding site, as compared to the wild-type promoter, when tested in BRAF-WT cells. Promoter activity was tested with standardized luciferase experiments. The expression of ETS1 was verified with immunoblotting. (C) Isoform specific real-time PCR shows the dominance of isoform-2 of ETS1 in various melanoma lines.

List of Specific Primers Used for qPCR, Cloning, and Mutagenesis