Abstract

Chromosome band 8q24 is the most frequently amplified locus in various types of cancers. MYC has been identified as the primary oncogene at the 8q24 locus, whereas a long noncoding gene, PVT1, which lies adjacent to MYC, has recently emerged as another potential oncogenic regulator at this position. In this study, we established and characterized a novel cell line, AMU‐ML2, from a patient with diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (DLBCL), displaying homogeneously staining regions at the 8q24 locus. Fluorescence in situ hybridization clearly detected an elevation in MYC copy numbers corresponding to the homogenously staining region. In addition, a comparative genomic hybridization analysis using high‐resolution arrays revealed that the 8q24 amplicon size was 1.4 Mb, containing the entire MYC and PVT1 regions. We also demonstrated a loss of heterozygosity for TP53 at 17p13 in conjunction with a TP53 frameshift mutation. Notably, AMU‐ML2 cells exhibited resistance to vincristine, and cell proliferation was markedly inhibited by MYC‐shRNA‐mediated knockdown. Furthermore, genes involved in cyclin D, mTOR, and Ras signaling were downregulated following MYC knockdown, suggesting that MYC expression was closely associated with tumor cell growth. In conclusion, AMU‐ML2 cells are uniquely characterized by homogenously staining regions at the 8q24 locus, thus providing useful insights into the pathogenesis of DLBCL with 8q24 abnormalities.

Keywords: chromosome 8q24, diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma, homogeneously staining region, MYC, oncogene amplification, patient‐derived cell line

Abbreviations

- aCGH

array comparative genomic hybridization

- CCND1

cyclin D1

- CNA

copy number alteration

- DLBCL

diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma

- FISH

fluorescence in situ hybridization

- GSEA

gene set enrichment analysis

- HSR

homogeneously staining region

- PBL

peripheral blood leukocyte

- PVT1

plasmacytoma variant translocation 1

- qRT‐PCR

quantitative reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction

- R‐CHOP

rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone

- R‐Hyper‐CVAD/MA

high‐dose methotrexate and cytarabine

Gene amplification, observed in the form of double‐minute chromosomes or homogeneously staining regions (HSRs), is recurrent and plays an important role in cancer 1. HSR is rarely seen in hematopoietic neoplasms compared with solid tumors and is observed at a lower frequency in lymphoid neoplasms than in myeloid neoplasms 2.

Chromosome 8q24 is the most frequently amplified locus in many cancers, with MYC being the most likely oncogene at this locus. The MYC gene encodes a transcription factor that regulates the expression of many target genes that control cell proliferation. The deregulation of MYC, resulting from t(8;14) and gene amplification, leads to the constitutive overexpression of MYC in numerous cancers and plays a pathogenetic role in oncogenesis 3, 4.

Plasmacytoma variant translocation 1 (PVT1) is also located at 8q24, 57 kb downstream of MYC, and extends over 200 kb in the direction of the telomeres. PVT1 is a non‐protein‐coding gene and a homologue of mouse Pvt1 5. The Pvt1 locus is a site of recurrent translocation in mouse plasmacytomas and a common integration site for the murine leukemia virus, which is capable of inducing T‐cell lymphomas in mice. In contrast to the typical Burkitt lymphoma (BL), in which the t(8;14) translocation contains a breakpoint within MYC, the t(2;8) or t(8;22) variant translocations in BL contain breakpoints in PVT1 6.

PVT1 produces a variety of noncoding RNAs, including several microRNAs 7. The precise functions of the PVT1 region and its noncoding RNAs remain unclear, although the long noncoding PVT1 RNA has a documented role in stabilization of the MYC protein 8. Moreover, several groups have reported that the amplification and subsequent overexpression of PVT1 have an oncogenic function in ovarian and breast cancers 9. A genomewide screen using array comparative genomic hybridization (array‐CGH) and gene expression profiling identified PVT1 as a candidate oncogene in breast and ovarian cancers, acute myeloid leukemia, and Hodgkin lymphoma 10, 11. Furthermore, we have previously reported two novel chimeric genes, PVT1‐NBEA and PVT1‐WWOX, in multiple myeloma cell lines 12.

In addition, a circular RNA obtained from exon 3 of PVT1 (circPVT1) has been shown to function as a promoter of cell proliferation in fibroblasts 13, an important prognostic factor in gastric cancer 14, and a diagnostic marker in osteosarcoma 15, and to have an oncogenic role in head and neck carcinoma and myeloid leukemia 16, 17. Hu et al. 18 have also described circPVT1 overexpression in B‐cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and performed functional studies indicating its role in B‐cell proliferation. Taken together, these reports highlight the potential importance of the MYC/PVT1 locus in the pathophysiology of many cancers.

Diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of non‐Hodgkin lymphoma and is known as a biologically heterogeneous tumor. Although approximately 70% of patients with DLBCL survive longer than five years when treated with immunochemotherapy involving rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone (R‐CHOP), the remainder succumb to the disease 19. A high international prognostic index, extranodal lesions, a non‐germinal center B‐cell phenotype, BCL2 expression, the deletion of CDKN2A, and MYC rearrangements have been recognized as high‐risk features in DLBCL treated using R‐CHOP 20. The prognostic and biological significance of MYC rearrangements in DLBCL has been thoroughly investigated. However, the role of PVT1, which may be co‐amplified with MYC, remains unclear.

We herein report the AMU‐ML2 novel DLBCL cell line, obtained from a primary refractory patient. This cell line is uniquely characterized by a HSR at the 8q24 locus, containing MYC and PVT1 and displaying a high expression of PVT1 long noncoding RNAs. Here, we report the genetic and biological characteristics of this cell line in comparison with other B‐cell lymphoma cell lines.

Materials and methods

Case history

A 64‐year‐old man was referred to the clinic presenting pancytopenia, a 2‐month history of anorexia, and general fatigue in November 2011. The laboratory and chest X‐ray examinations revealed a white blood cell count of 1000 μL−1, hemoglobin of 9.6 g·dL−1, a platelet count of 5000 μL−1, LDH of 2397 U·L−1, and bilateral pleural effusion (Fig. S1A,B). Abnormal lymphocytes with Burkitt‐like morphology were observed in the pleural effusion and bone marrow (Fig. S1C,D). The patient was diagnosed with DLBCL and commenced treatment with R‐CHOP. G‐banding of cells revealed a complex karyotype; however, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) using a MYC/IGH probe set revealed a significant increase in MYC copy number, in the absence of a fusion signal. Subsequently, the patient underwent a more intensive regimen involving rituximab plus hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and dexamethasone, alternating with high‐dose methotrexate and cytarabine (R‐Hyper‐CVAD/MA) 21 after one cycle of R‐CHOP. The patient responded to the treatment; however, he developed cytomegalovirus pneumonia after four cycles of R‐Hyper‐CVAD/MA and died of Trichosporon asahii sepsis at 6 months postdiagnosis.

Establishment of the AMU‐ML2 cell line

The patient provided written informed consent for his cells from the pleural effusion to be used in a procedure approved by the Institutional Review Board of Aichi Medical University. The study methodologies conformed to the standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki. The cells were collected at the time of initial diagnosis, prior to chemotherapy. The cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% heat‐inactivated fetal bovine serum (Thermo Electron, Melbourne, Vic., Australia) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (GIBCO‐BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA). Cultures were maintained at 37 °C in 5% CO2, and the medium was partially exchanged every 5–7 days. After 2 months in culture, cell proliferation became continuous. The cell line was designated as AMU‐ML2 after confirmation that cells had started growing again after the conventional freeze–thaw procedure.

B‐cell lymphoma cell lines, cell culture, and drugs

The AMU‐ML2, SU‐DHL‐10, Raji, P3HR‐1, VAL, and Farage B‐cell lymphoma cell lines were cultured as previously described 22. Prednisolone, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and doxorubicin were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan).

Chromosomal analyses and spectral karyotyping

Chromosome preparations for G‐banding, spectral karyotyping, and FISH were performed according to standard procedures (SRL Inc., Tokyo, Japan) 23, 24. A total of 20 metaphase spreads were analyzed by G‐banding, and the karyotype was defined according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature 25. Spectral karyotyping analyses were performed in metaphase spreads according to standard procedures (SRL Inc.) 26.

Morphology and immunophenotype of bone marrow‐ and pleural effusion‐derived patient cells

Cells obtained from the patient's bone marrow and a pleural effusion were air‐dried on a glass slide. The cellular morphology was analyzed using May–Grunwald–Giemsa and immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining. The following antigens were examined by flow cytometry (SRL Inc.): CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5, CD7, CD8, CD10, CD19, CD20, CD34, and CD56. The CD3, CD5, CD10, CD20, CD79a, cyclin D1, BCL2, BCL6, TP53, TdT and MIB‐1 labeling indices were examined by IHC. The anti‐TP53 antibody was purchased from DAKO Japan Inc. (clone DO‐7; Kyoto, Japan). The Epstein–Bar virus‐encoded RNA was examined by in situ hybridization.

FISH analysis

Detection of the 8q24 aberration and deletion of 17p in both metaphase and interphase nuclei was performed using the Vysis LSI IGH/MYC/CEP8 Tri‐Color Dual Fusion Probes (Fig. S1A) and the Vysis LSI TP53/CEP17 Dual Fusion Probes (Abbot Molecular, Des Plaines, IL, USA). Bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) and P1‐derived artificial chromosome (PAC) clones RP1‐160A22, RP1‐193B12, RP1‐109F14, and RP11‐55J15 were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). FISH probes for the analysis of chromosome 6p and 8q breakpoints were prepared with DNA extracted from BAC clones and Poseidon Sub‐Telomeric Probes for chromosome 8 (KREATECH, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) (Fig. S1A,B). DNA extraction was performed using the NucleoBond Xtra Midi kit (Macherey‐Nagel, Düren, Germany). Labeling and hybridization of DNA were performed as previously described 27. BAC/PAC information was obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/gdv/), and the probes were confirmed to map to the precise chromosomal bands using metaphase spreads from peripheral blood lymphocytes of healthy donors.

Genome copy number analyses

Array‐CGH was performed using the SurePrint G3 Human CGH 2 × 400K, Oligo Microarray Kit (G4448A; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), which contains approximately 400 000 60‐mer oligonucleotides covering the entire human genome. Genomic DNA was extracted from AMU‐ML2 cells using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). DNA labeling, hybridization, and washing were performed according to the manufacturer's protocols. Scanning analyses were performed using the Agilent Microarray Scanner (Agilent Technologies). The array data were analyzed to determine chromosomal copy numbers using the feature extractions version 11.0 software program (Agilent Technologies) and the analytical software program dna analytics, version 4.0 (Agilent Technologies). The ADM‐1 algorithm (Threshold 6.0) was adopted to detect genomic aberrations 28. The relationship between the log2 ratio (X), the copy number in the reference sample (A), the average copy number in tumor cells (B), and the ratio of tumor cells (C) was determined as X = Log2.

DNA sequence analyses

Total RNA was isolated from AMU‐ML2 cells using the NucleoSpin RNA kit (TaKaRa Bio, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Complementary DNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA by using the High‐Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Invitrogen). PCR amplification of the open reading frame of TP53 was performed with a gene‐specific primer set as follows: forward primer, 5′‐ATGGAGGAGCCGCAGTCAGA; reverse primer, 5′‐TCAGTCTGAGTCAGGCCCTT. Sequence analysis was performed using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit and an Applied Biosystems 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Foster City, CA, USA).

Western blot analyses

Western blot analyses were performed as described previously 29. Briefly, proteins in the cell lysate were separated on 10% polyacrylamide gels, followed by transfer onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). The membrane was hybridized with a mouse monoclonal anti‐c‐Myc antibody (9E10; Wako) and a rabbit anti‐β‐actin antibody (13E5; Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA, USA). The membrane was visualized using ImmunoStar LD (Wako).

Real‐time qRT‐PCR

The expression levels of the MYC and PVT1 transcripts were quantified by real‐time qRT‐PCR using TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (MYC, Hs00153408_m1; PVT1, Hs00413039_m1; β‐actin, Hs99999903_m1; Applied Biosystems) and the StepOnePlus™ Real‐Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). In brief, total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and cDNA was synthesized from total RNA by using the SuperScript III First‐Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). The expression level of circPVT1 was quantified by real‐time qRT‐PCR using SYBR Green I (TaKaRa Bio, Inc.) with the StepOnePlus™Real‐Time PCR System, as previously described 13, 30, 31. cDNA was amplified using KOD FX Neo polymerase (Toyobo, Tokyo, Japan) with SYBR Green I. Primers for circPVT1 were follows: forward: 5′‐GGTTCCACCAGCGTTATTC; reverse: 5′‐CAACTTCCTTTGGGTCTCC 32. GAPDH was used as an internal standard for the SYBR Green I‐based analysis. Relative expression was determined using the 2−ΔΔCT method. The relative gene expression was determined using the gene expression in peripheral blood leukocytes (PBLs) from healthy donors as a control.

MYC knockdown

The pRetrosuper Myc shRNA and pMKO.1‐puro GFP shRNA were gifts from Addgene (plasmids #15662 and #10675, respectively; Cambridge, MA, USA) 33, 34. To obtain cells stably expressing decreased levels of MYC, the MYC shRNA vector (AMU‐ML2/MYCsh) or the control GFP shRNA vector (AMU‐ML2/GFPsh) was introduced into AMU‐ML2 cells. The retroviral plasmids were packaged into 293T cells using the pCL10A vector. Viral supernatants were harvested 96 h after transfection and filtered before infection. The cells were infected with retroviruses in the presence of 8 μg·mL−1 Polybrene (Sigma‐Aldrich). Antibiotic selection (puromycin; 0.3 μg·mL−1; Wako) was begun 48 h after infection and continued for at least 3 days. Following infection and antibiotic selection, the cells were examined for MYC protein levels using western blotting.

Microarray gene expression analyses

The experimental procedure for the cDNA microarray analysis was based on the manufacturer's protocol (Agilent Technologies). In brief, cDNA synthesis and cRNA labeling with the cyanine 3 (Cy3) dye were performed using the Agilent Low Input Quick Amp Labeling Kit. The Cy3‐labeled cRNA was purified, fragmented, and hybridized on a Whole Human Genome 4 × 44k Oligo Microarray Chip containing 43 377 oligonucleotide probes, using a Gene Expression Hybridization kit. The microarray slide was washed and scanned using an Agilent DNA microarray scanner (Agilent Technologies). The scanned data were quantified using the feature extraction software program, version 11.0.1.1 (Agilent Technologies). The signal intensities were then normalized as described elsewhere 35.

The background signals were also normalized, and the microarray expression data were rank‐ordered based on the differential expression in AMU‐ML2/MYCsh cells versus AMU‐ML2/GFPsh cells as follows: Up‐ and downregulated genes were called when exhibiting a > 0.27 increase (fold change > 2.0) or < −0.27 decrease (fold change < 0.5), respectively, in AMU‐ML2/MYCsh cells versus AMU‐ML2/GFPsh cells.

Results

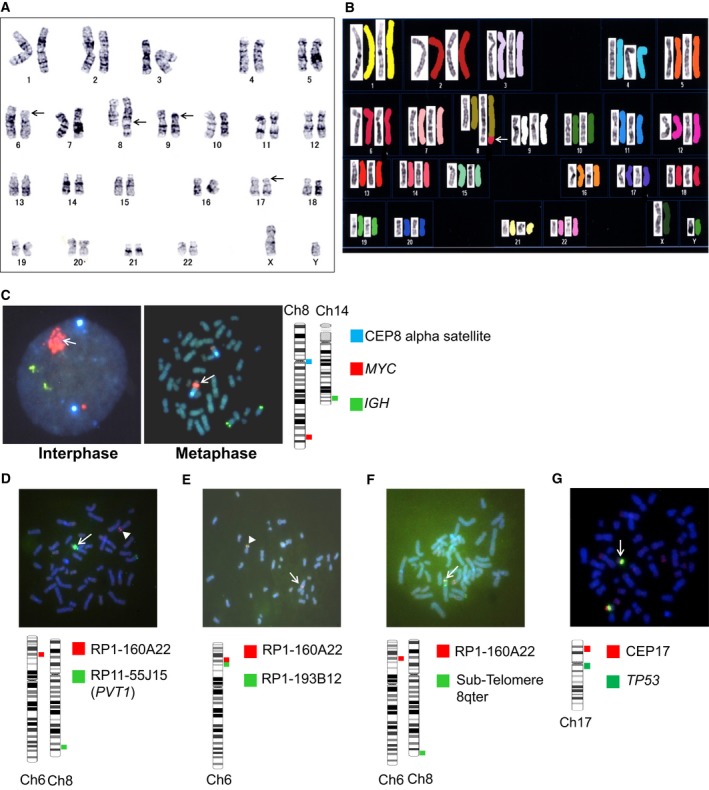

Karyotyping and FISH analysis of 8q24 abnormalities in AMU‐ML2 cells

The karyotyping of AMU‐ML2 cells by G‐banding and spectral karyotyping revealed the following karyotype: 46,XY,del(6)(p21p23),der(8)(8pter→8q24::hsr::6p21→6pter),add(9)(p13),del(17)(p?) 21 (Fig. 1A,B). The FISH analysis of AMU‐ML2 cells using a MYC/IGH probe set revealed no fusion signal for IGH and MYC; however, a significant increase in the MYC copy number was observed, corresponding to the HSR on chromosome 8q24 (Fig. 1C). The copy number of the amplicon at 8q24.21 was approximately 26 per tumor cell. A FISH analysis using RP11‐55J15, containing a segment of PVT1 but not the MYC gene (Fig. S2A), also showed a significant increase in the copy number at the PVT1 gene locus (Fig. 1D). The FISH analysis of AMU‐ML2 cells using an RP1‐160A22/RP11‐55J15 probe set revealed that chromosome 6p21.2‐22.2 translocated on chromosome 8q (white arrow), and a significant increase in the PVT1 copy number was observed (white triangle), corresponding to the HSR on chromosome 8q24 (Fig. 1D). RP11‐55J15 contained a segment of PVT1 but not the MYC gene (Fig. S2A), and also showed a significant increase in the copy number at the PVT1 gene locus. The FISH analysis of AMU‐ML2 cells using a RP1‐160A22/RP1‐193B12 probe set revealed fusion signal for both probes on chromosome 6p (white triangle); however, the other RP1‐193B12 was absent on chromosome 6p, and the other RP1‐160A22 translocated on chromosome 8q (white arrow) (Fig. 1E). The FISH analysis of AMU‐ML2 cells using a RP1‐160A22/Sub‐Telomere 8qter probe set revealed a fusion signal for both probes on chromosome 8q telomere (Fig. 1F). The FISH analysis of AMU‐ML2 cells using a TP53/ CEP17 set revealed that one of TP53 disappeared on chromosome 17p (Fig. 1G). The copy number of the amplicon at 8q24.21 was approximately 26 per tumor cell.

Figure 1.

Karyotype and FISH analyses of AMU‐ML2 cells. (A, B) Representative karyotype by G‐banding and spectral karyotyping indicated 46,XY,del(6)(p21p23),der(8)(8pter→8q24::hsr::6p21→6pter),add(9)(p13),del(17)(p?). (A) The black arrows indicate abnormal sites detected by G‐banding. (B) Spectral karyotyping analysis; the white arrow indicates the fusion of part of chromosome 6 (6ptel–6p21, red) with the telomeric region of 8q24. (C–F) FISH analysis of 8q24 containing the entire MYC and PVT1 regions (C), the 6p22–p21 breakpoint of t(6;8) (D–F) and the 17p13.2 locus, containing the TP53 gene (G) in AMU‐ML2 cells. Schematic illustrations of the FISH probes used in this study are presented beside each figure panel. (C) Interphase (left) and metaphase (right) FISH analyses using Vysis LSI IGH (green), MYC (red), and CEP8 (aqua) Tri‐Color Dual Fusion Probes are shown. The white arrow indicates the HSR on the MYC probe (red), without any IGH/MYC fusion signals. The copy number of the amplicon at 8q24.21 was approximately 26 per tumor cell. (D) The white arrow indicates the HSR on RP11‐55J15 (green), which covers part of PVT1 but not MYC, as depicted in Fig. S2A. The white arrowhead indicates a single copy signal on RP1‐160A22 (red) at 6p22. (E) The white arrowhead indicates a fusion signal on the normal chromosome 6. RP1‐160A22, shown in red; RP1‐193B12, shown in green. The white arrow indicates another red signal but no green signal on the derivative chromosome 8. (F) The white arrow indicates a fusion signal on the derivative chromosome 8. RP1‐160A22, shown in red; KREATECH Sub‐Telomere 8qter, shown in green. (G) The white arrow indicates a single copy signal at the TP53 gene locus. Vysis LSI CEP17, show in green; TP53 probe, shown in red. Ch, chromosome.

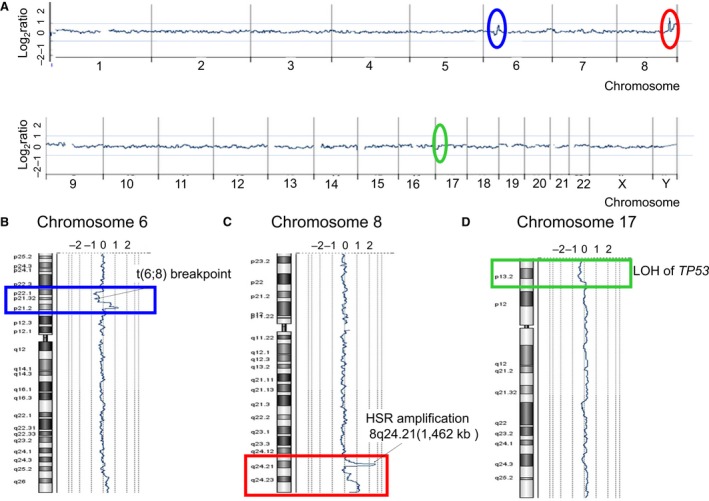

Array‐CGH analyses and TP53 sequencing of AMU‐ML2 cells

To further investigate the genomewide copy number aberrations in AMU‐ML2 cells, we performed an array‐CGH (aCGH) analysis using an Agilent human CGH 400K Oligo Microarray format (Agilent Technologies; Fig. 2A, Table 1). The aCGH analysis identified several large deletions and amplifications as follows: a 7431‐kb deletion at 6p22.1–6p21.31, which contains the t(6;8) breakpoint detected by FISH (Fig. 2B); a 1462‐kb amplification at 8q24.21, which contains MYC and PVT1 (Fig. 2C); and a 7522‐kb deletion at 17p13.3–17p.13.1, which harbors the TP53 gene (Fig. 2D). The aCGH analysis also showed that the HIST1 gene locus, spanning 27.9–35.3 Mb on 6p22–6p21, contained a monoallelic deletion (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, our aCGH analysis detected 14 additional copy number alterations (CNAs). Segment gains were detected on chromosomes 6p21.31–p21.2, 8p11.23, 8q24.21, 8q24.3, 9p24.3–9p13.1, 14q11.2, and 19q13.2, whereas segment losses were detected on chromosomes 6p25.3, 6p22.1–6p21.31, 6p12.3, 7q31.33, 14q32.33, and 17p13.3–17p.13.1 (Table 1).

Figure 2.

High‐resolution aCGH analysis in AMU‐ML2 cells. Genomewide copy number aberrations in AMU‐ML2 cells were determined using an Agilent SurePrint G3 Human CGH 2× 400K Oligo Microarray (Agilent Technologies). The median probe spacing was approximately 4.6 kb. (A) Summary of the aCGH analysis. The x‐axis indicates the chromosome number, whereas the y‐axis indicates the log2 ratio (copy number aberrations). The red oval indicates a 1462‐kb highly amplified region, containing MYC and PVT1 at 8q24.21. The blue and green ovals indicate copy number changes at 6p22 to 6p21 and at 17p13, respectively. The other copy number alterations (CNAs) detected are summarized in Table 1. (B) The aCGH analysis shows a 7431‐kb deletion at 6p22.1–6p21.31, where the t(6;8) breakpoint was detected by FISH, as indicated in Fig. 4F. Blue rectangle, copy number changes at 6p22–6p21. (C) A 1462‐kb amplification detected by the aCGH analysis, containing MYC and PVT1 at 8q24.21, where 8q24.1 HSR was detected by FISH, as indicated in Fig. 4C. Red rectangle, copy number changes at 8q24. (D) A 7522‐kb deletion at 17p13.3–17p.13.1 detected by the aCGH analysis, where a single copy deletion of TP53 was detected by FISH, as indicated in Fig. 4F. Green rectangle, copy number changes at 17p13.

Table 1.

Copy number alteration (CNA) regions and estimated target genes detected by array‐CGH in AMU‐ML2 cells

| Chromosome band | Start (kb) | End (kb) | Size (kb) | Average log2 ratio | Number of genes | Candidate genesa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gains | ||||||

| 6p21.31–6p21.2 | 35 339 | 38 624 | 3285 | 0.62 | 39 | MAPK14, MAPK13, ETV7, PIM1 |

| 38 629 | 39 800 | 1171 | 1.21 | 9 | ||

| 8p11.23 | 39 354 | 39 505 | 151 | 1.07 | 0 | |

| 8q24.21 | 126 515 | 128 586 | 2071 | 0.55 | 2 | |

| 8q24.21 | 128 611 | 130 073 | 1462 | 2.62 | 2 | MYC, PVT1 |

| 8q24.3 | 138 653 | 146 147 | 7494 | 1.04 | 82 | EIF2C2, BOP1, MAPK15, MAF1 |

| 9p24.3–9p13.1 | 189 | 390 481 | 390 292 | 0.45 | 128 | JAK2, PAX5 |

| 14q11.2 | 21 523 | 22 237 | 714 | 0.57 | 2 | |

| 19q13.2 | 46 947 | 47 693 | 746 | 0.54 | 22 | LYPD4, CD79A |

| Losses | ||||||

| 6p25.3 | 158 | 318 | 160 | −0.54 | 1 | DUSP22 |

| 6p22.1–6p21.31 | 27 896 | 35 327 | 7431 | −0.52 | 133 | HIST1H2AK, HIST1H2AL, HIST1H3I, HIST1H4L, HIST1H3J, HIST1H2AM, HIST1H2BO, HLA‐E, NOTCH4, HLA‐A, HLA‐B, HLA‐C, HLA‐DRA, HLA‐DRB5, HLA‐DRB1, HLA‐DQA1, HLA‐DQB1, HLA‐DQA2, |

| 6p12.3 | 50 840 | 50 944 | 104 | −0.7 | 2 | TFAP2D, TFAP2B |

| 7q31.33 | 124 941 | 125 414 | 473 | −0.83 | 0 | |

| 14q32.33 | 105 314 | 106 037 | 723 | −1.12 | 0 | |

| 17p13.3–17p13.1 | 51 | 7522 | 7471 | −0.45 | 110 | TP53 |

Genes listed here are candidates based on their putative function.

In addition, reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) and Sanger sequencing analysis detected a frameshift mutation of TP53 in AMU‐ML2 cells (c.377_378delAC; Fig. S5).

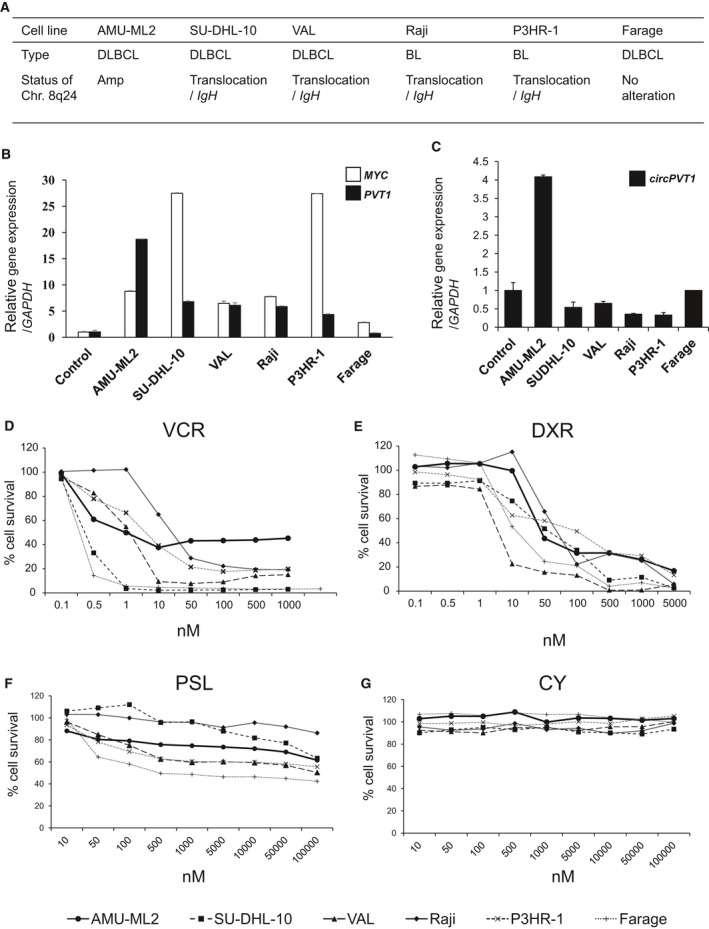

MYC, PVT1, and circPVT1 mRNA levels in AMU‐ML2 and other B‐cell lymphoma cell lines

To investigate the influence of the 8q24.21 amplification on MYC, PVT1, and circPVT1 expression, we performed quantitative RT‐PCR (qRT‐PCR) analysis in AMU‐ML2 cells and other B‐cell lymphoma cell lines, for which the chromosomal status at 8q24 is summarized in Fig. 3A. qRT‐PCR analysis showed that the expression of MYC, PVT1, and circPVT1 was significantly higher in AMU‐ML2 cells than that in PBLs from healthy donors. In addition, the expression of PVT1 and circPVT1 in AMU‐ML2 cells was the highest among the cell lines used in this study (Fig. 3B,C).

Figure 3.

MYC and PVT1 expression and the effect of chemotherapy on cell survival in AMU‐ML2 and other B‐cell lymphoma cell lines. (A) Chromosome 8q24 status in the B‐cell lymphoma cell lines used in this study. Amp, amplification. (B) MYC and PVT1 expression in B‐cell lymphoma cell lines (AMU‐ML2, SU‐DHL‐10, VAL, Raji, P3HR‐1, and Farage) and normal PBLs using TaqMan probe methodology. No association between the relative mRNA expression of MYC and that of PVT1 is observed. The relative gene expression is shown after normalization to GAPDH. The data are expressed relative to the mRNA levels found in the corresponding PBL samples, arbitrarily defined as 1. The values shown represent the means ± SE (n = 3). (C) circPVT1 expression in B‐cell lymphoma cell lines as determined by real‐time qRT‐PCR using SYBR Green methodology. The expression of circPVT1 in AMU‐ML2 cells was the highest among the cell lines used in this study. (D–G) Effect of chemotherapy on cell survival in AMU‐ML2 and other B‐cell lymphoma cell lines. AMU‐ML2 and other B‐cell lymphoma cell lines (SU‐DHL‐10, VAL, Raji, P3HR‐1, and Farage) were treated with the indicated concentration of vincristine (VCR, C) (1000, 500, 100, 50, 10, 1, 0.5, or 0.1 nm), doxorubicin (DXR, D) (5000, 1000, 500, 100, 50, 10, 1, 0.5, or 0.1 nm), prednisolone (PSL, E) (100 000, 50 000, 10 000, 5000, 1000, 500, 100, 50, or 10 nm), and cyclophosphamide (CY, F) (the same as prednisolone) for 72 h. After incubation, the cells were assayed using the MTT assay. Data are expressed relative to the mean optical density (595 nm) found in untreated cells, which was arbitrarily defined as 100%. Data are expressed as the means ± SE (n = 3).

Resistance of AMU‐ML2 cells to vincristine

To clarify the effect of anticancer drugs used in the chemotherapy of DLBCL on AMU‐ML2 cells, we performed an MTT assay using AMU‐ML2 and other B‐cell lymphoma cell lines following treatment with vincristine, doxorubicin, prednisolone, and cyclophosphamide. The MTT assay showed that AMU‐ML2 cells exhibited resistance to vincristine (at 100, 500, and 1000 nm), whereas cell survival in other B‐cell lymphoma cell lines was almost completely suppressed in a dose‐dependent manner (Fig. 3D). The MTT assay also showed that doxorubicin dose‐dependently decreased the cell survival rate in all cell lines used in this study (Fig. 3E). Prednisolone partially suppressed cell proliferation in AMU‐ML2 and B‐cell lymphoma cell lines, whereas cyclophosphamide did not exhibit any tumor‐suppressive effects (Fig. 3F,G).

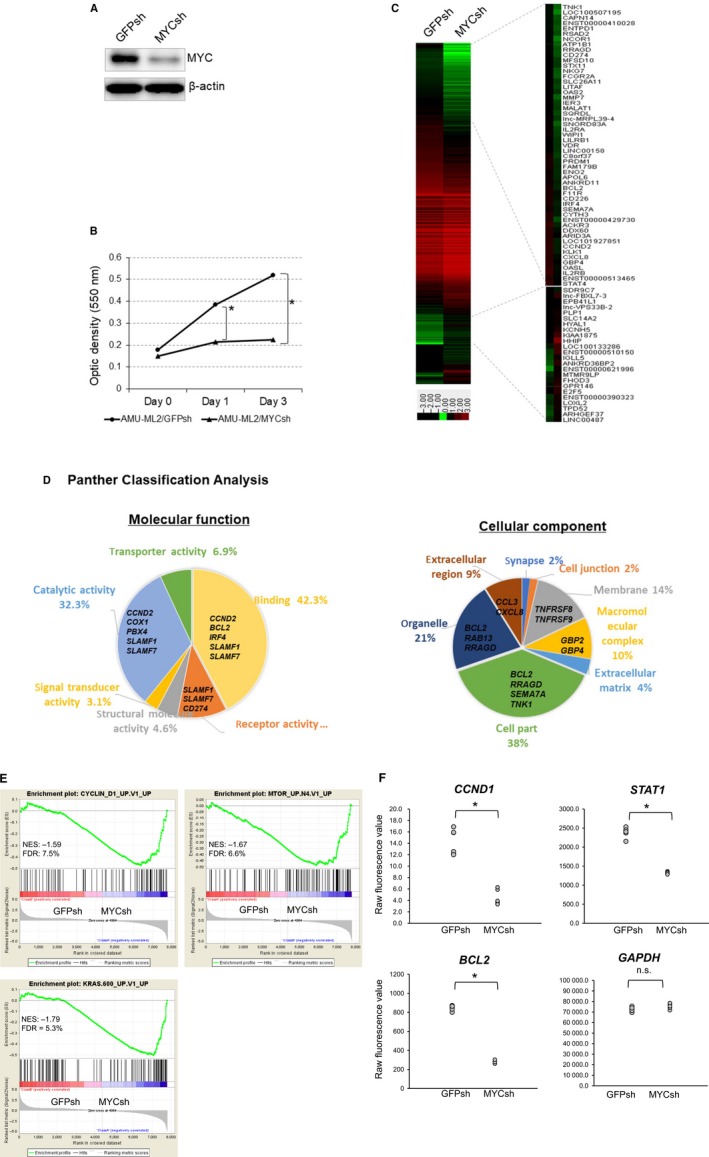

The role of MYC in proliferation and gene expression in AMU‐ML2 cells

As our data showed that MYC expression was higher in AMU‐ML2 cells than that in PBLs from normal healthy volunteers, we next investigated the effects of MYC expression on cell proliferation using RNA interference. Our western blot analysis showed robust MYC expression in AMU‐ML2 cells expressing the control GFPsh vector; the expression of this protein decreased in cells expressing MYCsh (Fig. 4A). Therefore, we examined the effect of MYC knockdown on cell proliferation using an MTT assay. The MTT assay showed that the optical densities reflecting the cell numbers were significantly higher at both days 1 and 3 in cells expressing GFPsh than in those expressing MYCsh, strongly suggesting that MYC expression is closely associated with cell proliferation in AMU‐ML2 cells (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Effect of MYC knockdown on cell proliferation and gene expression in AMU‐ML2 cells. (A) The MYC gene silencing shRNA vector (pRetrosuper Myc shRNA, plasmid 15662 from Addgene) or control GFPsh vector (pMKO.1‐puro GFP shRNA, plasmid 10675 from Addgene) was stably introduced into AMU‐ML2 cells using retroviral transduction. Cell clones were obtained after puromycin selection and subsequent single‐cell cloning. Five micrograms of cell lysate was subjected to a western blot analysis, to detect the MYC protein. β‐Actin was used as an internal control. (B) MTT analysis of the growth rate of AMU‐ML2/GFPsh and AMU‐ML2/MYCsh clones. The optical density (595 nm) at each time point (days 0, 1, and 3) is presented as the means ± SE (n = 4). Statistical significance between groups was determined using Student's t‐test. Statistical analyses were performed using spss 23.0 program (SPSS Inc.). The asterisk (*) indicates significant differences at P < 0.05, compared to the GFPsh clone. (C–E) Gene expression analysis. Total RNA from MYCsh and GFPsh clones was extracted and subjected to a cDNA microarray analysis using a SurePrint G3 Human 8 × 60K V3 format (Agilent Technologies). (C) Heatmap of downregulated (172 genes, fold change < 0.5) and upregulated genes (214 genes; fold change, > 2.0) following MYC knockdown. The heatmap was constructed using normalized values for each sample and the treeview software 43. The corresponding gene names are annotated on the right. (D) Gene ontology analyses using the PANTHER classification system. The downregulated genes were classified using the PANTHER‐Gene List Analysis (http://www.pantherdb.org). Pie chart showing the percentages of genes classified into each molecular pathway and/or cellular component. (E) The GSEA was conducted using the gsea software program, v2.2.4, and Molecular Signatures Database (Broad Institute). All raw data were formatted and applied to oncogenic signatures (C6). Representative GSEA enrichment plots and corresponding heatmap images of the indicated gene sets are shown for the MYCsh and GFPsh clones, respectively. Genes contributing to the enrichment are shown in rows, and the samples are shown in columns on the heatmap. Expression is shown as a gradient from high (red) to low (blue). FDR, false discovery rate; NES, normalized enrichment score. (F) Graphs showing the differential gene expression in cells expressing GFPsh and MYCsh. Raw fluorescence values obtained by scanning were utilized for the comparison of gene expression. The gene oligonucleotide probes corresponding to cyclin D1, STAT1, and BCL2 are shown. *P < 0.05, significant difference.

To further investigate the role of MYC in tumorigenesis in AMU‐ML2 cells, we performed a comprehensive gene expression analysis using Agilent cDNA microarrays. A heatmap analysis revealed different gene expression patterns between cells expressing GFPsh and those expressing MYCsh (Fig. 4C). We also observed that MYC knockdown downregulated the expression of 172 genes by < 0.5‐fold and upregulated the expression of 214 genes by > 2.0‐fold compared with that in cells expressing GFPsh (Tables S1 and S2). Moreover, we found that MYC knockdown significantly decreased the expression of cyclin D1 (CCND1), BCL2, and STAT1 but not that of GAPDH in AMU‐ML2 cells (Fig. 4F). By using a PANTHER classification analysis, we showed that 42.3% of the downregulated genes encoded binding proteins, including CCND2, BCL2, IRF4, SLAMF1, and SLAMF7 (Fig. 4D,E). Notably, this analysis also showed that 8.0% of the downregulated genes encoded either inflammation‐ or apoptosis‐related signaling molecules (Fig. S3). Therefore, we performed a gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) to investigate whether the expression of a specific set of oncogenesis‐associated genes significantly differed between the MYC knockdown and control cells. Genes with oncogenic signatures showed a significant inactivation of cyclin D signaling‐related genes (NKG7, IFITM1, and PDE2), of genes induced by mTOR signaling (ITPR1, ATF3, and BATF), and of Ras signaling‐associated genes (NR4A3, DOCK4, and SATB1) (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, a GSEA using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes database showed a significant inactivation of genes associated with peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐, hematopoietic‐, and cytokine–cytokine receptor‐related signaling (Fig. S4). Collectively, these results suggest that MYC expression is closely associated with tumor cell growth in AMU‐ML2 cells.

Discussion

A HSR is occasionally observed in solid tumors, but rarely detected in DLBCL 36. In this study, we established a novel DLBCL cell line, AMU‐ML2, using patient cells, which was uniquely characterized by a HSR at the 8q24 locus, containing MYC and PVT1 (Fig. 1). Our aCGH analysis clearly identified the 8q24 amplicon size as ranging from 128 611 to 130 073 kb in the HSR (Fig. 2, Table 1). Moreover, we found that the amplicon contained the entire MYC and PVT1 sequences and was amplified at more than 20 copies per cell. To our knowledge, this is the first to report of a DLBCL cell line showing an amplicon containing the entire MYC and PVT1 genes at 8q24. As the patient‐derived cells were collected before the initiation of chemotherapy and established within 2 weeks, the detected chromosomal aberrations reflect the actual pathogenesis for the onset of aggressive DLBCL and do not reflect chemotherapy and/or long‐term cell culture.

The expression levels of both MYC and PVT1 were significantly higher in AMU‐ML2 and other B‐lymphoma cells with 8q24 abnormalities than those in PBLs from healthy donors and Farage cells lacking 8q24 abnormalities (Fig. 3B). The expression of MYC and PVT1 appears similar to that observed in gene amplification and translocation events at immunoglobulin loci.

MYC, a candidate oncogene at the 8q24 amplification, has been reported to play an important role in the pathogenesis of lymphoma and leukemia 37. In this study, we show that the MYC‐shRNA‐mediated knockdown significantly suppressed cell proliferation in AMU‐ML2 cells (Fig. 4A,B). Furthermore, a cDNA microarray analysis revealed that the CCND2 cell‐cycle‐promoting gene, the IRF4 oncogenic transcription factor, and the BCL2 anti‐apoptotic gene were all downregulated following MYC knockdown (Fig. 4C). Although MYC is assumed to repress the transcription of BCL2 directly or through p53, BCL2 expression was repressed by MYC inhibition in AMU‐ML2 cells. This suggests the dysfunction of p53 in the AMU‐ML2 background. Our GSEA also showed that MYC knockdown inactivated gene expression for oncogenic gene sets, including the Ras, mTOR, and cyclin D signaling pathways (Fig. 4E). These results strongly suggest that the survival and proliferation of AMU‐ML2 cells strongly depend on the aberrant MYC expression.

Recent reports have suggested that the deregulation of PVT1 consequent to gene amplification and chromosomal translocation may contribute to tumorigenesis and drug resistance 9, 38. Patients with DLBCL often suffer from resistance to chemotherapy, including R‐CHOP. Resistance to cisplatin by PVT1 overexpression has been reported in gastric and ovarian cancers 39. In addition, it has been reported that PVT1 promotes the development of multidrug resistance by mediating the mTOR/HIF‐1α/P‐glycoprotein pathway and/or the MRP1 signaling pathway 40. Moreover, overexpression of circPVT1 has been recently shown to serve as a prognostic factor in gastric cancer 14. In the present study, we found that AMU‐ML2 cells displayed vincristine resistance, in contrast to other B‐cell lymphoma cell lines (Fig. 3D). As the expression of PVT1 and circPVT1 in AMU‐ML2 cells was the highest among the cell lines tested (Fig. 3B,C), the overexpression of PVT1 and circPVT1 may contribute to vincristine resistance in AMU‐ML2 cells. Although the pathogenic role of PVT1 in lymphoma is not precisely known, the examination of whether the microRNAs and/or circPVT1 transcribed from the PVT1 locus are linked to tumorigenesis and drug sensitivity in AMU‐ML2 cells is worthy of further study.

The co‐amplification of MYC and PVT1 has been reportedly observed in several types of solid tumors and is associated with a shortened survival 9. However, the biological differences underlying the deregulation of MYC alone, or that of both MYC and PVT1, are not well characterized in DLBCL. Future clinical studies utilizing RNA‐seq, whole‐genome sequencing, and functional experiments will help clarify the precise incidence, clinical implications, and biological significance of the co‐amplification of MYC and PVT1 in DLBCL.

In addition to the HSR at 8q24, we have identified several other CNA loci (Table 1, Fig. 2A). TP53 is a well‐known tumor suppressor gene at the 17p13.1 locus. Loss of heterozygosity and inactivating mutations in the TP53 gene are frequently observed in many cancers and constitute a poor prognosis for DLBCL. In the present study, our aCGH analysis showed a monoallelic 7.8‐Mb deletion, which contains the TP53 gene (Fig. 2D). Moreover, the identification of a TP53 frameshift mutation in AMU‐ML2 cells suggested that p53 does not function in these cells. It has been reported that the disruption of the p14/ARF‐MDM2‐p53 pathway that accompanies MYC overexpression contributes to the pathogenesis of BL 41. It may therefore be possible that the pathophysiology of DLBCL is partly associated with the HSR at 8q24 as well as with the dysregulation of p53 in AMU‐ML2 cells. We also detected a chromosomal breakpoint and a single copy deletion in the HIST1 gene in AMU‐ML2 cells (Table 1, Fig. 2B). The HIST1 gene spans over 2 Mb and contains all the replication‐dependent H1 histone genes and other core histone genes at the 6p22–p21 locus. Moreover, it encodes histone proteins, which associate with the double‐stranded helical DNA molecule to form the chromatin, and play a role in gene regulation 42. In AMU‐ML2 cells, the deletion of a part of HIST1, after the t(6;8) translocation, may result in the haploinsufficiency of HIST1, which may influence chromatin remodeling and cellular gene expression.

In conclusion, the present study is the first to show a HSR containing both MYC and PVT1 at the 8q24 locus, in the AMU‐ML2 novel DLBCL cell line. We also demonstrated a loss of heterozygosity for TP53 at 17p13 with a frameshift mutation of TP53, suggesting that the high expression of MYC and TP53 dysfunction may contribute to cell survival in DLBCL. The AMU‐ML2 cell line is useful for investigating the roles of MYC and PVT1 and the interaction of the products of both genes in lymphomagenesis. Furthermore, it would be of interest to investigate the molecular mechanism through which AMU‐ML2 cells induce vincristine resistance. Our finding that MYC expression is closely related to the expression of oncogenic genes, including those in the Ras, mTOR, and CCND signaling pathways, provides new insights that may aid in the development of novel molecular‐targeted drugs for the treatment of patients with DLBCL. Further studies are required to clarify the role of PVT1 in the pathophysiology of DLBCL.

Author contributions

IH designed the study. SM, AO, SK, JK, and MT performed the experimental analyses. SM, IH, and AO wrote the manuscript. AN, ST, KU, TH, MG, SM, MG, HY, MW, and MS contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. YH, HM, RU, MN, and AT contributed to overall project management.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. Chest X‐ray and computed tomography (CT) findings of the patient with DLBCL on admission. (A) Chest X‐ray and B) CT findings revealing a bilateral moderate to severe pleural effusion. Morphology and immunohistochemistry (IHC) for the pleural effusion and bone marrow (BM) samples in the patient with DLBCL. (C, D) Cells from the pleural effusion and bone marrow showing medium to large cells with Burkitt‐like morphology (E‐H) IHC analysis of the patient‐derived BM cells. BM‐derived cells were incubated with anti‐BCL6 (E), anti‐cyclin D1 (F), anti‐MUM (G), and anti‐BCL2 (H) antibodies according to the manufacturer's instructions. Original magnification: 400×; MG: May–Grunwald–Giemsa staining.

Fig. S2. Schema of the detected genomic aberrations and the BAC/PAC probes in the corresponding chromosomal gene locus. (A) Genomic features at 8q24. The amplicon detected by aCGH analysis (green), the gene structure of MYC and PVT1, the PVT1‐encoded microRNAs, BAC clone (RP11‐55J15, green bar), and Vysis FISH probe (LSI/MYC, shown in red) are depicted. The FISH probe for MYC (red bar) covers an 821‐kb region containing the entire MYC and PVT1 genes. The RP11‐55J15 BAC clone partially covers the PVT1 region, but not the MYC region. The size of the 8q24 amplicon (green bar) detected by aCGH approximately spans 1462 kb, containing the entire MYC and PVT1 genes. PVT1 encodes at least six microRNAs (miR‐1204, miR‐1205, miR‐1206, miR‐1207‐5p, miR‐1207‐3p, and miR‐1208; blue bar). The black horizontal bars indicate exons in each gene. (B) Genomic features at 6p22‐p21. The deletion detected by aCGH (purple), gene structure including a HIST1 gene cluster, and PAC clones (RP1‐97D16, black bar; RP1‐160A22, red bar; RP1‐193B12, green bar; RP3‐408B20 and RP1‐109F14, black bar) used for FISH analysis are depicted. The positional data for genes, microRNAs, and PAC/BAC clones were obtained from the NCBI website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and the dna analytics software (Agilent Technologies). The positions (Mb) indicate the distance from the telomeric end on the short arm of each chromosome. Mb, mega base.

Fig. S3. Results of Panther Classification Analysis. Gene ontology analyses using the Panther Classification System. The downregulated genes in cells expressing MYCsh were classified using PANTHER‐Gene List Analysis (http://www.pantherdb.org). The percentages of genes classified into each pathway are shown as a pie chart.

Fig. S4. GSEA with Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) gene sets. GSEA was conducted using GSEA v2.2.4 software and the Molecular Signatures Database (Broad Institute). All of the raw data were formatted and applied to the KEGG gene sets (C2).

Fig. S5. Sequencing analysis of TP53 gene in AMU‐ML2 cells. (A) Total RNA was isolated from AMU‐ML2 cells using the NucleoSpin RNA kit (TaKaRa Bio, Inc.). After synthesizing complementary DNA, PCR amplification of TP53 gene was performed with a gene‐specific primer set, as described in Online Supplementary Data. Sequence analysis was performed by using an Applied Biosystems 3130 Genetic Analyzer. The TP53 frameshift mutation c.377_378delAC was detected in AMU‐ML2 cells (arrowhead). (B) Sequence alignment of TP53 with wild‐type (WT) TP53 gene. Nucleotide number is in reference to GenBank accession NM_000546.5 (TP53 transcript variant 1, mRNA).

Table S1. Downregulated genes under MYC knockdown in AMU‐ML2 cells.

Table S2. Upregulated genes under MYC knockdown in AMU‐ML2 cells.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. A Nakamura and Ms. T Nakamura for their valuable secretarial assistance and Editage for their editorial assistance. This study was supported by grants from the Aichi Cancer Research Foundation, Hori Sciences and Arts Foundation, Japan Blood Products Organization, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports and Technology of Japan (15K19561), the Nagao Memorial Fund, the Research Grant from Aichi Medical University Aikeikai Foundation, the SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation, and the YOKOYAMA Foundation for Clinical Pharmacology.

References

- 1. Cowell JK (1982) Double minutes and homogeneously staining regions: gene amplification in mammalian cells. Annu Rev Genet 16, 21–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jin C, Mertens F, Jin Y, Wennerberg J, Heim S and Mitelman F (1995) Complex karyotype with an 11q13 homogeneously staining region in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 82, 175–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dang CV (2012) MYC on the path to cancer. Cell 149, 22–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boxer LM and Dang CV (2001) Translocations involving c‐myc and c‐myc function. Oncogene 20, 5595–5610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Palumbo AP, Boccadoro M, Battaglio S, Corradini P, Tsichlis PN, Huebner K, Pileri A and Croce CM (1990) Human homologue of Moloney leukemia virus integration‐4 locus (MLVI‐4), located 20 kilobases 3ʹ of the myc gene, is rearranged in multiple myelomas. Cancer Res 50, 6478–6482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sun LK, Showe LC and Croce CM (1986) Analysis of the 3ʹ flanking region of the human c‐myc gene in lymphomas with the t(8;22) and t(2;8) chromosomal translocations. Nucleic Acids Res 14, 4037–4050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huppi K, Volfovsky N, Runfola T, Jones TL, Mackiewicz M, Martin SE, Mushinski JF, Stephens R and Caplen NJ (2008) The identification of microRNAs in a genomically unstable region of human chromosome 8q24. Mol Cancer Res 6, 212–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tseng YY, Moriarity BS, Gong W, Akiyama R, Tiwari A, Kawakami H, Ronning P, Reuland B, Guenther K, Beadnell TC et al (2014) PVT1 dependence in cancer with MYC copy‐number increase. Nature 512, 82‐86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guan Y, Kuo WL, Stilwell JL, Takano H, Lapuk AV, Fridlyand J, Mao JH, Yu M, Miller MA, Santos JL et al (2007) Amplification of PVT1 contributes to the pathophysiology of ovarian and breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 13, 5745–5755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Enciso‐Mora V, Broderick P, Ma Y, Jarrett RF, Hjalgrim H, Hemminki K, van den Berg A, Olver B, Lloyd A, Dobbins SE et al (2010) A genome‐wide association study of Hodgkin's lymphoma identifies new susceptibility loci at 2p16.1 (REL), 8q24.21 and 10p14 (GATA3). Nat Genet 42, 1126–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sircoulomb F, Bekhouche I, Finetti P, Adélaïde J, Ben Hamida A, Bonansea J, Raynaud S, Innocenti C, Charafe‐Jauffret E, Tarpin C et al (2010) Genome profiling of ERBB2‐amplified breast cancers. BMC Cancer 10, 539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nagoshi H, Taki T, Hanamura I, Nitta M, Otsuki T, Nishida K, Okuda K, Sakamoto N, Kobayashi S, Yamamoto‐Sugitani M et al (2012) Frequent PVT1 rearrangement and novel chimeric genes PVT1‐NBEA and PVT1‐WWOX occur in multiple myeloma with 8q24 abnormality. Cancer Res 72, 4954–4962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Panda AC, De S, Grammatikakis I, Munk R, Yang X, Piao Y, Dudekula DB, Abdelmohsen K and Gorospe M (2017) High‐purity circular RNA isolation method (RPAD) reveals vast collection of intronic circRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 45, e116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen J, Li Y, Zheng Q, Bao C, He J, Chen B, Lyu D, Zheng B, Xu Y, Long Z et al (2017) Circular RNA profile identifies circPVT1 as a proliferative factor and prognostic marker in gastric cancer. Cancer Lett 388, 208–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kun‐Peng Z, Xiao‐Long M and Chun‐Lin Z (2018) Overexpressed circPVT1, a potential new circular RNA biomarker, contributes to doxorubicin and cisplatin resistance of osteosarcoma cells by regulating ABCB1. Int J Biol Sci 14, 321–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Verduci L, Ferraiuolo M, Sacconi A, Ganci F, Vitale J, Colombo T, Paci P, Strano S, Macino G, Rajewsky N et al (2017) The oncogenic role of circPVT1 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma is mediated through the mutant p53/YAP/TEAD transcription‐competent complex. Genome Biol 18, 237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. L′Abbate A, Tolomeo D, Cifola I, Severgnini M, Turchiano A, Augello B, Squeo G, D Addabbo P, Traversa D, Daniele G et al (2018) MYC‐containing amplicons in acute myeloid leukemia: genomic structures, evolution, and transcriptional consequences. Leukemia 32, 2152–2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hu J, Han Q, Gu Y, Ma J, McGrath M, Qiao F, Chen B, Song C and Ge Z (2018) Circular RNA PVT1 expression and its roles in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Epigenomics 10, 723–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sweetenham JW (2005) Diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma: risk stratification and management of relapsed disease. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2005, 252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jardin F, Jais JP, Molina TJ, Parmentier F, Picquenot JM, Ruminy P, Tilly H, Bastard C, Salles GA, Feugier P et al (2010) Diffuse large B‐cell lymphomas with CDKN2A deletion have a distinct gene expression signature and a poor prognosis under R‐CHOP treatment: a GELA study. Blood 116, 1092–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thomas DA, Faderl S, O'Brien S, Bueso‐Ramos C, Cortes J, Garcia‐Manero G, Giles FJ, Verstovsek S, Wierda WG, Pierce SA et al (2006) Chemoimmunotherapy with hyper‐CVAD plus rituximab for the treatment of adult Burkitt and Burkitt‐type lymphoma or acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer 106, 1569–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mizuno S, Hanamura I, Ota A, Karnan S, Narita T, Ri M, Mizutani M, Goto M, Gotou M, Tsunekawa N et al (2015) Overexpression of salivary‐type amylase reduces the sensitivity to bortezomib in multiple myeloma cells. Int J Hematol 102, 569–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Seabright M (1971) A rapid banding technique for human chromosomes. Lancet 2, 971–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Siebert R, Matthiesen P, Harder S, Zhang Y, Borowski A, Zühlke‐Jenisch R, Metzke S, Joos S, Weber‐Matthiesen K, Grote W et al (1998) Application of interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization for the detection of the Burkitt translocation t(8;14)(q24;q32) in B‐cell lymphomas. Blood 91, 984–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shaffer LG, McGowan‐Jordan J, Schmid M, International Standing Committee on Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (2013) ISCN 2013: An International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature. Karger, Basel, Switzerland and New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Veldman T, Vignon C, Schrock E, Rowley JD and Ried T (1997) Hidden chromosome abnormalities in haematological malignancies detected by multicolour spectral karyotyping. Nat Genet 15, 406–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hanamura I, Stewart JP, Huang Y, Zhan F, Santra M, Sawyer JR, Hollmig K, Zangarri M, Pineda‐Roman M, van Rhee F et al (2006) Frequent gain of chromosome band 1q21 in plasma‐cell dyscrasias detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization: incidence increases from MGUS to relapsed myeloma and is related to prognosis and disease progression following tandem stem‐cell transplantation. Blood 108, 1724–1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lipson D, Aumann Y, Ben‐Dor A, Linial N and Yakhini Z (2006) Efficient calculation of interval scores for DNA copy number data analysis. J Comput Biol 13, 215–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gotou M, Hanamura I, Nagoshi H, Wakabayashi M, Sakamoto N, Tsunekawa N, Horio T, Goto M, Mizuno S, Takahashi M et al (2012) Establishment of a novel human myeloid leukemia cell line, AMU‐AML1, carrying t(12;22)(p13;q11) without chimeric MN1‐TEL and with high expression of MN1. Genes Chromosom Cancer 51, 42–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Takahashi M, Ota A, Karnan S, Hossain E, Konishi Y, Damdindorj L, Konishi H, Yokochi T, Nitta M and Hosokawa Y (2013) Arsenic trioxide prevents nitric oxide production in lipopolysaccharide‐stimulated RAW 264.7 by inhibiting a TRIF‐dependent pathway. Cancer Sci 104, 165–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wahiduzzaman M, Ota A, Karnan S, Hanamura I, Mizuno S, Kanasugi J, Rahman ML, Hyodo T, Konishi H, Tsuzuki S et al (2018) Novel combined Ato‐C treatment synergistically suppresses proliferation of Bcr‐Abl‐positive leukemic cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Lett 433, 117–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Panda AC and Gorospe M (2018) Detection and analysis of circular RNAs by RT‐PCR. Bio‐protocol 8, e2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Masutomi K, Possemato R, Wong JM, Currier JL, Tothova Z, Manola JB, Ganesan S, Lansdorp PM, Collins K and Hahn WC (2005) The telomerase reverse transcriptase regulates chromatin state and DNA damage responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 8222–8227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Popov N, Wanzel M, Madiredjo M, Zhang D, Beijersbergen R, Bernards R, Moll R, Elledge SJ and Eilers M (2007) The ubiquitin‐specific protease USP28 is required for MYC stability. Nat Cell Biol 9, 765–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Huber W, von Heydebreck A, Sültmann H, Poustka A and Vingron M (2002) Variance stabilization applied to microarray data calibration and to the quantification of differential expression. Bioinformatics 18, S96–S104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Storlazzi CT, Lonoce A, Guastadisegni MC, Trombetta D, D'Addabbo P, Daniele G, L'Abbate A, Macchia G, Surace C, Kok K et al (2010) Gene amplification as double minutes or homogeneously staining regions in solid tumors: origin and structure. Genome Res 20, 1198–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Anderson NM, Li D, Peng HL, Laroche FJ, Mansour MR, Gjini E, Aioub M, Helman DJ, Roderick JE, Cheng T et al (2016) The TCA cycle transferase DLST is important for MYC‐mediated leukemogenesis. Leukemia 30, 1365–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. You L, Chang D, Du HZ and Zhao YP (2011) Genome‐wide screen identifies PVT1 as a regulator of Gemcitabine sensitivity in human pancreatic cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 407, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu E, Liu Z, Zhou Y, Mi R and Wang D (2015) Overexpression of long non‐coding RNA PVT1 in ovarian cancer cells promotes cisplatin resistance by regulating apoptotic pathways. Int J Clin Exp Med 8, 20565–20572. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Eischen CM, Weber JD, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ and Cleveland JL (1999) Disruption of the ARF‐Mdm2‐p53 tumor suppressor pathway in Myc‐induced lymphomagenesis. Genes Dev 13, 2658–2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Marzluff WF, Gongidi P, Woods KR, Jin J and Maltais LJ (2002) The human and mouse replication‐dependent histone genes. Genomics 80, 487–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Harshman SW, Young NL, Parthun MR and Freitas MA (2013) H1 histones: current perspectives and challenges. Nucleic Acids Res 41, 9593–9609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Page RD (1996) TreeView: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput Appl Biosci 12, 357–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Chest X‐ray and computed tomography (CT) findings of the patient with DLBCL on admission. (A) Chest X‐ray and B) CT findings revealing a bilateral moderate to severe pleural effusion. Morphology and immunohistochemistry (IHC) for the pleural effusion and bone marrow (BM) samples in the patient with DLBCL. (C, D) Cells from the pleural effusion and bone marrow showing medium to large cells with Burkitt‐like morphology (E‐H) IHC analysis of the patient‐derived BM cells. BM‐derived cells were incubated with anti‐BCL6 (E), anti‐cyclin D1 (F), anti‐MUM (G), and anti‐BCL2 (H) antibodies according to the manufacturer's instructions. Original magnification: 400×; MG: May–Grunwald–Giemsa staining.

Fig. S2. Schema of the detected genomic aberrations and the BAC/PAC probes in the corresponding chromosomal gene locus. (A) Genomic features at 8q24. The amplicon detected by aCGH analysis (green), the gene structure of MYC and PVT1, the PVT1‐encoded microRNAs, BAC clone (RP11‐55J15, green bar), and Vysis FISH probe (LSI/MYC, shown in red) are depicted. The FISH probe for MYC (red bar) covers an 821‐kb region containing the entire MYC and PVT1 genes. The RP11‐55J15 BAC clone partially covers the PVT1 region, but not the MYC region. The size of the 8q24 amplicon (green bar) detected by aCGH approximately spans 1462 kb, containing the entire MYC and PVT1 genes. PVT1 encodes at least six microRNAs (miR‐1204, miR‐1205, miR‐1206, miR‐1207‐5p, miR‐1207‐3p, and miR‐1208; blue bar). The black horizontal bars indicate exons in each gene. (B) Genomic features at 6p22‐p21. The deletion detected by aCGH (purple), gene structure including a HIST1 gene cluster, and PAC clones (RP1‐97D16, black bar; RP1‐160A22, red bar; RP1‐193B12, green bar; RP3‐408B20 and RP1‐109F14, black bar) used for FISH analysis are depicted. The positional data for genes, microRNAs, and PAC/BAC clones were obtained from the NCBI website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and the dna analytics software (Agilent Technologies). The positions (Mb) indicate the distance from the telomeric end on the short arm of each chromosome. Mb, mega base.

Fig. S3. Results of Panther Classification Analysis. Gene ontology analyses using the Panther Classification System. The downregulated genes in cells expressing MYCsh were classified using PANTHER‐Gene List Analysis (http://www.pantherdb.org). The percentages of genes classified into each pathway are shown as a pie chart.

Fig. S4. GSEA with Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) gene sets. GSEA was conducted using GSEA v2.2.4 software and the Molecular Signatures Database (Broad Institute). All of the raw data were formatted and applied to the KEGG gene sets (C2).

Fig. S5. Sequencing analysis of TP53 gene in AMU‐ML2 cells. (A) Total RNA was isolated from AMU‐ML2 cells using the NucleoSpin RNA kit (TaKaRa Bio, Inc.). After synthesizing complementary DNA, PCR amplification of TP53 gene was performed with a gene‐specific primer set, as described in Online Supplementary Data. Sequence analysis was performed by using an Applied Biosystems 3130 Genetic Analyzer. The TP53 frameshift mutation c.377_378delAC was detected in AMU‐ML2 cells (arrowhead). (B) Sequence alignment of TP53 with wild‐type (WT) TP53 gene. Nucleotide number is in reference to GenBank accession NM_000546.5 (TP53 transcript variant 1, mRNA).

Table S1. Downregulated genes under MYC knockdown in AMU‐ML2 cells.

Table S2. Upregulated genes under MYC knockdown in AMU‐ML2 cells.