Abstract

Obesity, defined as a state of positive energy balance with a body mass index (BMI) exceeding 30 kg/m2 in adults and 95th percentile in children, is an increasing global concern. Approximately one-third of the world’s population is overweight or obese, and in the U.S. alone, obesity affects one in six children. Meta-analysis studies suggest that obesity increases the likelihood of developing several types of cancer, and with poorer outcomes, especially in children. The contribution of obesity to cancer risk requires a better understanding of the association between obesity-induced metabolic changes and its impact on genomic instability, which is a major driving force of tumorigenesis. In this review we discuss how molecular changes during adipose tissue dysregulation can result in oxidative stress and subsequent DNA damage. This represents one of the many critical steps connecting obesity and cancer, since oxidative DNA lesions can result in cancer-associated genetic instability. In addition, the by-products of the oxidative degradation of lipids (e.g., malondialdehyde, 4-hydroxynonenal, and acrolein), and gut microbiota-mediated secondary bile acid metabolites (e.g., deoxycholic acid and lithocholic acid), can function as genotoxic agents and tumor promoters. We also discuss how obesity can impact DNA repair efficiency, potentially contributing to cancer initiation and progression. Finally, we outline obesity-related epigenetic changes and identify the gaps in knowledge to be addressed for the development of better therapeutic strategies for the prevention and treatment of obesity-related cancers.

Keywords: obesity, DNA damage, DNA repair, oxidative stress, genetic instability

Introduction

The present global burden of issues affecting human health is not limited to infectious disease, as non-communicable disease, such as obesity is the fifth leading global risk factor for mortality1. The global prevalence of children and adults being overweight or obese has increased by ~47% and ~28%, respectively, between 1980 and 20132. Overweight and obesity are defined as the accumulation of excess body fat, which can have a negative effect on health. The body-mass index (BMI), measured as a ratio of weight in kilograms to the square of the height in meters, is often used as a tool for assessing overall adiposity. Adults with a BMI of 25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2 are considered overweight, whereas a BMI of >30 kg/m2 is considered as obese. BMI-for-age percentiles define whether a child or young adult is overweight (85th to 95th percentile) or obese (>95th percentile)3. With one-third of the world’s population being overweight or obese, both developed and developing countries are coping with the challenges posed by this epidemic4.

Apart from the psychological challenges such as depression, anxiety, eating disorders and low self-esteem5, obesity is also associated with a number of psychiatric disorders6. High adiposity also elevates the risk for developing other serious diseases and health conditions such as metabolic syndrome, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, sleep disorders, cardiovascular disease, and osteoarthritis7. Evidence from several epidemiological studies have suggested that a significant increase in the amount of body fat is associated with an increased risk of various cancers, including endometrial, breast, colon, kidney, gallbladder, liver and melanoma to name a few8–11. In fact, according to a 2012 population-based study, ~4% of all cancer cases in adults worldwide may be attributed to high BMI levels12.

Meta-analysis data from epidemiological studies have enabled us to identify the existence of a link between obesity and several diseases. But owing to the differences in metabolic profiles, genetics, and the environment to which an individual is exposed, mechanistic studies are required to determine the physiological and pathological alterations instigated at the molecular level. For example, there are several metabolic alterations that are thought to link obesity and cancer, including: 1) chronic low-level systemic inflammation due to elevated levels of cytokines13; 2) insulin resistance due to high levels of insulin and insulin like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), resulting in altered insulin signaling14; 3) dysregulation of adipokines, e.g., leptin and adiponectin15; 4) elevated levels of estrogen in adipose tissue16; 5) increased lipids and alterations in lipid signaling17; and 6) oxidative stress leading to cellular and molecular alterations, including DNA damage18.

The molecular mechanisms that underlie the effects of obesity on tumor formation are complex and certainly involve multiple pathways. An important factor associated with obesity-induced metabolic dysregulation is alterations in the adipose tissue19. Adipose tissue is a dynamic endocrine organ, which apart from serving as an energy reservoir, has biochemical and metabolic functions that are implicated in cancer incidence and progression20,21. Many groups have found that p53 levels are elevated in adipose tissue under conditions of chronic nutrient abundance. Contrary to its role as a tumor suppressor, the sustained activation of p53 signaling has been linked to the development of insulin resistance and adiposity. Activation of p53 also contributes to the induction of inflammatory cytokines that can promote the initiation and progression of cancer22–24.

Another pathway that seems to associate obesity with cancer development is genetic instability25. Many studies have indicated that obesity-related modulations in DNA damage and/or repair pathways may be involved in obesity-induced genetic instability26. However, little is known about the impact of obesity on DNA damage and DNA repair mechanisms that play critical roles in tumor initiation and progression. A better understanding of the relationship between obesity and cancer at the molecular level is important as it may aid in the development of effective therapies and non-invasive interventions that can help attenuate the obesity-associated cancer risk.

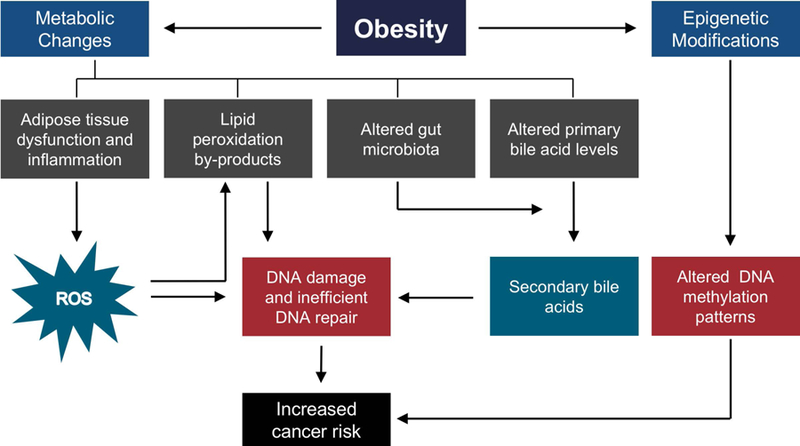

Studies have shown that oxidative stress and lipid dysregulation in obese individuals can result in elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which in turn can cause oxidative DNA damage directly or via the formation of reactive lipid peroxidation by-products (e.g., malondialdehyde, 4-hydroxynonenal and acrolein) and secondary bile acid metabolites (e.g., deoxycholic acid and lithocholic acid)18,27–29. Another aspect central to obesity-induced carcinogenesis is the inefficient repair and/or failure of DNA repair mechanisms to process ROS-induced and other obesity associated metabolite-mediated DNA lesions, which can result in genetic instability26. Recent studies have also suggested that obesity-induced epigenomic reprogramming can serve as signatures for the prediction of the development of obesity-related metabolic disorders and cancers30–32. This review specifically focuses on obesity-associated alterations in DNA damage (including oxidative DNA damage, and DNA damage induced by lipid peroxidation by-products and secondary bile acid metabolites), and DNA repair mechanisms that may result in genetic instability and increased cancer risk (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the impact of obesity on genetic instability.

1. DNA Damage

1.1. Obesity-induced oxidative stress promotes DNA damage

Formation of free-radicals is a consequence of many endogenous biochemical processes, as well as the result of exposure to external factors. The presence of unpaired electrons in free radicals such as the hydroxyl radical (•OH) and the superoxide radical (O2•-) makes them unstable and highly reactive33. Biological macromolecules such as nucleic acids, proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids are potential targets of free radicals or ROS, which can result in perturbations to cell and tissue homeostasis34. This process of oxidative stress can increase the potential for tissue damage; thus, cells have evolved a variety of anti-oxidative defense mechanisms35. However, the onset of several pathological conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease can disturb this balance leading to additional systemic oxidative stress36,37. Several studies in mice and humans have confirmed a positive correlation between systemic oxidative stress and fat dysregulation in adipose tissue, resulting in obesity-related metabolic disorders27,38,39.

Adipose tissue is the preferred site of excess fat storage during nutrient abundance. However, the expansion capacity of adipose tissue is finite and when a critical limit is reached, lipid spillage from adipocytes and accumulation in other metabolically harmful ectopic tissues can occur, resulting in lipid toxicity40. Environmental and genetic factors can modulate the capacity of adipose tissue to increase in mass41. Moreover, the regulation of the fat-storing capacity of adipose tissue, while maintaining homeostasis during obesity, is dependent on the ability of existing adipocytes to expand (hypertrophy) and or pre-adipocytes to differentiate into adipocytes (adipogenesis)42. For example, several studies in mouse models and humans have shown that hypertrophic expansion of adipocytes resulted in adipose tissue dysregulation associated with impaired insulin sensitivity, disturbed adipokine secretion, and induction of inflammation due to the activation and infiltration of immune/inflammatory cells43.

Using genetically engineered and/or diet-induced mouse models of obesity and insulin resistance, Prieur et al. (2011) showed that lipid-induced toxicity might serve as a link between obesity and inflammation due to adipose tissue macrophage (ATM) polarization44. The infiltration of macrophages and the induction of anti-inflammatory M2 markers, in association with remodeling of adipose tissue, may protect against progressive early-stage positive energy balance. However, later stages of obesity characterized by hypertrophic expansion of adipocytes can lead to ATM class switching from anti-inflammatory M2 to pro-inflammatory M1 cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin IL-1β, IL-6, leptin, visfatin, resistin, angiotensin II, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)45–49. In adipose tissue, these pro-inflammatory cytokines can promote insulin resistance either directly by inhibiting insulin signal transduction via serine phosphorylation of the insulin receptor50,51, or indirectly by disrupting the insulin signaling pathways via the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and the I-kappa B kinase β (IKKβ)/nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NFκB) pathways52. In addition, pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, TNF-α, and interferon gamma (IFN-γ) can stimulate the production of ROS stimulating oxidative stress53,54.

Though the inherent mechanism linking adipose tissue dysfunction and oxidative stress is unclear, various studies have suggested that the production of ROS and free radical generation is increased in adipose tissue in the obese state27,55. The role of oxidative stress in adipogenesis is not yet clearly understood. For example, while elevated oxidative stress in aging can inhibit pre-adipocyte differentiation56, in obesity, ROS and free radicals can promote pre-adipocyte differentiation57. To support a role of oxidative stress in the promotion of adipogenesis in obesity, Lee et al. (2009) demonstrated that redox-induced DNA binding of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-β (C/EBPβ) is crucial for the clonal expansion and differentiation of adipocytes58. Further, a study in non-diabetic obese Zucker fatty rats also showed that the association of obesity with a reduced redox state could promote differentiation of pre-adipocytes59.

The parallel increase of ROS levels with the expansion of adipocytes has also been found to be associated with the upregulation of NADPH oxidase 4 (Nox4)27,60,61. Although some studies have provided evidence for the protective effect of Nox462,63, others have reported Nox4-mediated ROS as a molecular switch promoting the differentiation of pre-adipocytes, the onset of insulin resistance, and adipose tissue inflammation60,64–66. Additionally, increased expression of Nox4 in white adipose tissue can result in the production of H2O2, which can be converted to •OH radicals via the Fenton and Haber-Weiss reactions in the presence of Fe2+ and Cu2+ ions, eventually leading to oxidative DNA damage27. Weyemi et al. (2012) have reported that the H-Ras oncogene positively regulated Nox4, resulting in the production of ROS, the induction of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), and subsequent cellular senescence67. In an obese mouse model, gain-of-function mutations in the H-Ras oncogene were found to be associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)68. Obesity has also been reported to be a risk factor for an aggressive acute myeloid leukemia phenotype containing an internal tandem duplication of the FMS-like tyrosine kinase receptor (FLT3-ITD). It has been shown that FLT3-ITD-expressing cell lines stimulated Nox-mediated ROS generation that resulted in error-prone DNA repair or DNA repair that may contribute to drug resistance69–72.

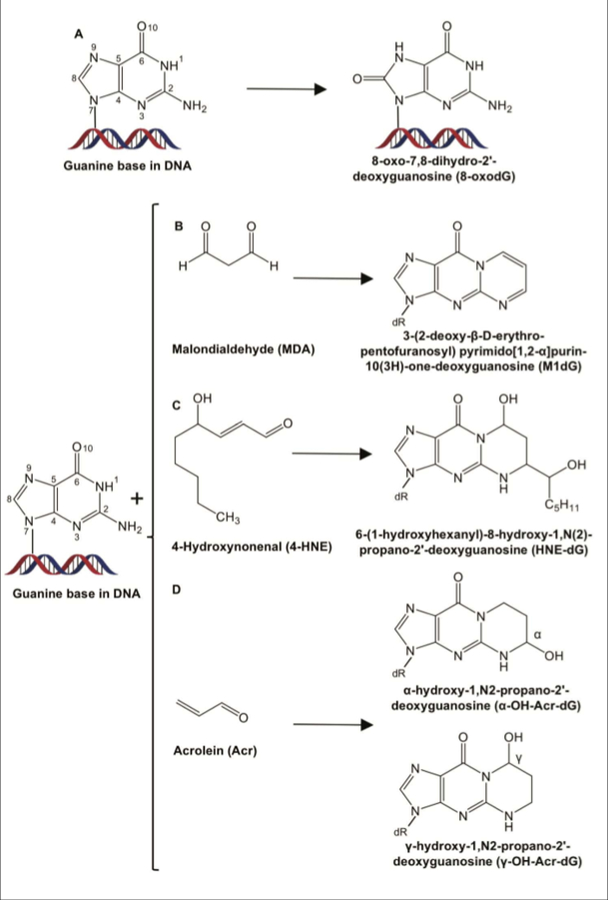

Thus, there are several obesity-related mechanisms of increased ROS production which can result in the formation of mutagenic lesions in the DNA such as 8‐hydroxy‐2′‐deoxyguanosine (8‐OH-dG) or 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-oxo-dG)18,73 (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Chemical structures of deoxyguanosine (dG) adducts in DNA generated endogenously via oxidation (A), and reactions of lipid peroxidation by-products with DNA (B-D).

A. 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-oxo-dG). B. 3-(2-deoxy-β-D-erythro-pentofuranosyl)pyrimido[1,2-α]purin-10(3H)-one-deoxyguanosine (M1dG). C. 6-(1-hydroxyhexanyl)-8-hydroxy-1,N(2)-propano-2’-deoxyguanosine (HNE-dG). D. α-hydroxy-1,N2-propano-2’-deoxyguanosine (α-OH-Acr-dG) and γ-hydroxy-1,N2-propano-2′-deoxyguanosine (γ-OH-Acr-dG).

Oxidized guanine bases (e.g., 8-oxo-dG) are sensitive biomarkers for the elevated levels of oxidative stress during obesity and carcinogenesis74–78. The induction and distribution of oxidative DNA damage depends on a number of factors, including but not limited to, chromatin structure, the accessibility of DNA repair proteins79, the DNA sequence80 and context (e.g., guanines are more susceptible to oxidation due to their low redox potential compared to other bases)81, alternative DNA secondary structures, which are known sources of genetic instability82,83 (e.g., hairpin-forming triplet repeat sequences are hypersensitive to oxidative damage)84,85, and metal ions86.

During DNA replication, DNA polymerases can misincorporate an A opposite 8-oxo-dG with a frequency of 10–75%, resulting in GC to TA mutations87. Other mutations that can result from guanine oxidation products include GC to AT or GC to CG mutations75,88,89. Such base substitution events have been frequently observed in the RAS oncogene and the p53 tumor suppressor gene in skin, lung and breast cancers90–92. Formation of 8-oxo-dG lesions adjacent to 5’-methyl-cytosine (5-mC) may inhibit the binding of methyl-binding proteins, thereby interfering with various steps of chromatin condensation, resulting in epigenetic alterations93. Oxidative DNA damage may also result in other cellular effects such as microsatellite instability, frameshift mutations, and acceleration of telomere shortening, leading to cellular senescence94,95.

The abundance and stability of 8-oxo-dG lesions and their mutagenic potential during DNA replication may represent one of the many critical steps connecting metabolic disorders and cancer96. However, the correlation between BMI and 8-oxo-dG levels is not clear. For example, one study found a negative correlation between BMI and 8-oxo-dG levels, and concluded that occupational stress combined with social and lifestyle factors increased cancer risk97. Whereas another study showed no correlation existed between BMI and 8-oxo-dG levels in urine samples, and suggested that urban living might contribute to elevated urinary 8-oxo-dG levels98. However, a one-year follow-up study in obese patients showed significantly reduced antioxidant enzymes (e.g., superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase) and increased oxidized/reduced glutathione ratios in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in addition to elevated serum and urinary 8-oxo-dG levels99.

DNA replication of guanine oxidation products may result in somatic mutations that can cause proliferation of smooth muscle cells contributing to the etiology of atherosclerosis plaque formation, a risk factor of obesity100,101. Obesity is also associated with NAFLD, and ROS-induced oxidative DNA damage that may contribute to chronic conditions, such as liver fibrosis and HCC in NAFLD patients102–104. The molecular mechanisms connecting obesity, ROS, and cancer are unclear; however, obesity-stimulated oxidative stress, contributing to DNA damage and consequently to genetic instability, appears to play an important role.

1.2. Obesity-induced lipid peroxidation by-products promote DNA damage

The microenvironment created by the dysregulation of adipose tissue allows for a continuous cycle where increased oxidative stress and inflammation together stimulate the induction of signaling molecules involved in transduction pathways maintaining adipogenesis and metabolic homeostasis. ROS-mediated oxidative degradation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), i.e., lipid peroxidation, results in unsaturated reactive aldehyde by-products such as malondialdehyde (MDA; Figure 2B), 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE; Figure 2C) and acrolein (Acr; Figure 2D)28. Both MDA and 4-HNE levels have been found to be increased in obese patients27,74. In fact, it has been reported that MDA levels in newborns positively correlated with maternal BMI and were also found to be elevated in obese children105,106. These electrophilic molecules can form adducts with nucleophilic centers of phospholipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, potentially altering their biological functions107. Of these, MDA is thought to be the most mutagenic, and 4-HNE the most genotoxic of all lipid peroxidation by-products108.

1.2.1. Malondialdehyde

MDA reacts with DNA to form 3-(2-deoxy-β-d-erythro-pentofuranosyl)pyrimido[1,2-α]purin-10(3H)-one-deoxygunanosine (M1dG) adducts109,110 (Figure 2B). M1dG has been detected in DNA from human leukocytes, liver, pancreas, and breast tissues typically at levels from 2–150 per 108 bases111–113. The cytotoxic and mutagenic effects of MDA have been demonstrated in Escherichia coli (E. coli) and mammalian cells114–116. For example, transfection of MDA-adduct containing plasmid DNA into mammalian cells stimulated a ~15-fold increase in mutation frequency over background levels115.

The high reactivity of MDA toward CG-rich sequences has been evidenced by the prevalence of MDA-induced base-pair substitutions or frameshift mutations at repetitive CG base-pairs in mammalian cells117. MDA adducts can also form DNA interstrand crosslinks (ICLs) which can block DNA replication and transcription. In addition to point mutations, these lesions can also result in large insertions and deletions during their processing and repair115. Further, unrepaired MDA-induced DNA lesions have been shown to result in frameshift mutations, point mutations, strand breaks, cell cycle arrest, and cellular apoptosis115–119.

MDA levels have been used as a biomarker for measuring seminal oxidative stress and were found to be positively correlated with oxidative guanine adduct levels120,121. Hosen et al. (2015) measured seminal MDA levels in 41 infertile male subjects, and found that oxidative stress-induced sperm DNA damage was associated with the pathogenesis of male infertility121. Further, several epidemiological studies indicated an increased infertility risk that correlated with increased levels of MDA in obese males compared to their non-obese counterparts122,123.

1.2.2. 4-Hydroxynonenal

Another by-product of lipid peroxidation, 4-HNE, is a reactive aldehyde that acts as a second messenger of free radicals124. At low intracellular concentrations (<2 μM), 4-HNE has been reported to promote cell survival and proliferation, but at higher concentrations (10 to 60 μM) it can result in mutagenesis (e.g., GC to AT mutations) and can function as a genotoxic agent (e.g., facilitating the formation of sister chromatid exchange, micronuclei formation, and DNA fragmentation) in mammalian cells125,126. 4-HNE can also cause inhibition of DNA synthesis leading to cytotoxicity127. The electrophilic nature of 4-HNE results in interactions with DNA bases with different specificities (G>C>A>T), leading to the formation of adducts that can interfere with DNA replication and transcription128. 4-HNE can be further metabolized by liver enzymes to an epoxide that can interact with DNA to form exocyclic etheno-guanine -cytosine and -adenine adducts129, where the major bulky exocyclic adduct in various human and rat tissues is 6-(1-hydroxyhexanyl)-8-hydroxy-1,N(2)-propano-2’-deoxyguanosine (HNE-dG; Figure 2C)130–132. Some stereoisomers of 4-HNE can form ICLs, which covalently link the two complementary strands of DNA, impeding DNA replication and transcription133.

A role for HNE-dG in the etiology of HCC has been reported134, and the tumor suppressor gene p53, is frequently mutated at codon 249 in HCC135–138. Using a wild-type p53 human lymphoblastoid cell line, Hussain et al. (2000) found that 4-HNE can bind to the third guanine of codon 249 (– AGG –) of p53, resulting in G to T transversions139. The p53 gene was mapped for 4-HNE-DNA adducts using the UvrABC nuclease, an E. coli nucleotide excision repair (NER) enzyme, and the results revealed preferential formation of 4-HNE adducts at the second guanine in codons 174 and 249, which contain the same sequence -G AGG* C-. Perhaps due to the chromatin structure in vivo, 4-HNE more frequently binds to the mutational hotspot in codon 249 than 174, providing a growth advantage to liver cells, contributing to HCC136,140.

1.2.3. Acrolein

Acrolein, a carcinogenic by-product of lipid peroxidation, can form two exocyclic DNA adducts, α- and γ-hydroxy-1,N2-propano-2′-deoxyguanosine (α-OH-Acr-dG and γ-OH-Acr-dG; Figure 2D), in human cells under conditions of oxidative stress141–144. Both adduct types, α-OH-Acr-dG and γ-OH-Acr-dG can induce base substitution mutations, and can inhibit DNA synthesis145,146. Acr-DNA adducts are thought to form predominantly at guanine residues, specifically in G-rich sequences, though Acr adducts with dC, dA and dT have also been reported147–150. A preference for Acr-DNA adduct formation has been shown at CpG sites containing methylated cytosines (5-mC), which are cytotoxic and mutagenic in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells and can exert dose-dependent effects in NER-deficient human xeroderma pigmentosum complement group A (XPA) cells when compared to NER-proficient human fibroblast cells150.

The interactions of Acr with newly-synthesized histones such as H4K12ac and H3K9 and K14ac has been reported. For example, Acr can interact with lysine residues 5 and 12 of histone H4 to form adducts that subsequently reduce histone acetylation. This can prevent certain protein-protein interactions ultimately affecting chromatin assembly151,152. Acr can also form ICLs or DNA-protein crosslinks (DPCs)153, which have been implicated in lung, liver and bladder cancers154–156.

1.3. Obesity-induced secondary bile acid metabolites promote DNA damage

Several studies have reported an association between obesity and alterations in the gut microbiome in mouse models and in humans157,158. However, a meta-analysis report suggested that this association was more robust in animal models than in the human cohorts studied. The variations in metabolism and the immune system from person to person may result in the inability of these studies to tease out the microbial differences (and causes and effects of obesity and microbiome alterations) in such cohort studies159. Nevertheless, the gut microbiota found in the intestinal epithelium of the host, through symbiotic interactions can assist in digestion and nutrient metabolism160, preservation of the structural integrity of the gut mucosal barrier to promote caloric extraction from the diet161,162, xenobiotic and drug detoxification, antimicrobial activities, and other homeostatic functions such as modulation of the immune system and modulation of apoptosis163,164.

Gut microbiota play an important role in digestion, and due to this function have been implicated in obesity and metabolic syndrome165,166. Studies in animal models and in humans have shown that obesity is associated with phylum-level changes in the microbiota. For example, metagenomic analyses of gut bacteria in mice and humans have shown increases in the Firmicute to Bacteroidete ratio in obese subjects compared to their lean counterparts167–169. However, Duncan et al. (2008) were unable to confirm this observation in humans, indicating variation in study outcomes related to the complexity of lifestyle and other factors170.

Gut microbiota also participate in the production of bioactive metabolites such as bile acids (BA) that signal through their cognate receptors to regulate the host metabolism171. The oxidation of cholesterol to primary BA in the liver is mediated by cytochrome P-450 enzymes172. In liver, the primary BA, cholic acid (CA) and chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) produced by humans, and CA and muricholic acid (MCA) produced by mice, conjugate with glycine and/or taurine to form bile salts before being secreted in the bile171. In the intestine, small amounts of the bile salts can undergo dehydroxylation by gut microbial populations with active BA-inducible genes to produce secondary bile metabolites such as deoxycholic acid (DCA; Figure 3A) and lithocholic acid (LCA; Figure 3B)173–175. Bacteria that can convert primary BA into secondary metabolites have been identified in Clostridium (clusters XIVa and XI) and in Eubacterium, both genera belonging to the Firmicutes phylum173,176–178. In addition to their important roles in cholesterol homeostasis172, BA can directly bind and activate the farnesoid X receptor (FXR), the pregnane X receptor (PXR), and the vitamin D receptor (VDR) to regulate lipid, glucose, and drug metabolism in liver and/or the intestine, which are frequently exposed to BA at relatively high concentrations179–183.

Figure 3. Chemical structures of secondary bile acids.

A. Deoxycholic acid. B. Lithocholic acid.

Differences in BA production and physiology in obese mice and humans have been reported. In obese (ob/ob) mice, hyperglycemia can stimulate the overexpression of CYP7A1 in the liver leading to increased synthesis and altered BA composition184. Conversely, studies in Fxr-deficient mice (Fxr−/−) bred on a genetically obese background (ob−/−Fxr−/−) or Fxr−/− mice fed on a high fat diet (HFD) showed resistance to weight gain compared to their respective ob/ob and wild-type control mice185,186. A recent study examining 32 obese, non-diabetic human subjects for the effects of obesity and insulin resistance on BA synthesis and transport, reported a substantial increase in BA synthesis markers and variations in BA serum levels along with defective hepatic BA transport187. Obesity is also associated with an altered representation of bacterial genes and metabolic pathways. For example, by modulation of the hepatic FXR signaling, a primary sensor for endogenous BA, gut bacteria not only regulate secondary bile salt metabolism, but also hepatic BA synthesis185,188. Thus, the microbiota-BA interactions play important roles in obesity and other metabolic disorders171.

One of the earliest studies suggesting the carcinogenic potential of BA, particularly secondary BA in mice was published in 1940189. Since that time, much research has been done to elucidate the roles of secondary bile metabolites in obesity-related gastrointestinal and pancreatic cancers29,190. Epidemiological studies have shown that consumption of a diet containing high fat and a high intake of beef products was associated with high fecal levels of the secondary bile acids DCA and LCA, similar to patients with carcinoma of the colon191,192. The inability to accurately measure the different forms of secondary bile acids may limit direct interpretation of such results; however, several mechanistic studies described below also provide support for the carcinogenic effects of DCA and LCA in rodents and humans.

Several bacterial studies have revealed the mutagenic effects of BA and their metabolites. Through single-gel electrophoresis assays, Ames tests, fluctuation assays and reversion assays in various Salmonella strains, research groups have identified the formation of DSBs, single-strand DNA breaks, abasic sites, frameshift mutations, base-pair substitutions, and point mutations in response to bile-salt exposure193–198. Results have shown that frameshift mutations (−1) were a result of the adaptive SOS response to the stressor BA, and point mutations were largely comprised of nucleotide substitutions (GC to AT transitions), suggesting that exposure to BA salts can result in oxidative DNA damage196.

1.3.1. Deoxycholic acid

DCA, a hydrophobic secondary metabolite of CA, is known to be a stress inducer and at higher than normal levels, DCA can adversely affect colon epithelial cells199. A diet high in fat has been associated with high levels of DCA, which can cause oxidative DNA damage, including modified bases, DSBs, aneuploidy, chromosomal alterations, micronuclei formation, and mitotic aberrations200–203. For example, DCA-induced mutations in the K-Ras gene in colon epithelial cells can provide a proliferative advantage to those cells, contributing to carcinogenesis204.

In obese mice, the levels of DNA-damaging DCA were found to be elevated in the enterohepatic circulation, and this was thought to be due to their altered gut bacterial metabolism191,205. DCA has been shown to induce a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) in hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) via upregulation of the 53BP1 and p21 genes. HSCs can also secrete inflammatory and tumor-promoting factors [e.g., IL-6, growth-regulated oncogene-alpha (Gro-α) and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL-9)] in the liver, thereby facilitating the development of HCC in mice after carcinogen exposure206,207. Reducing the production of DCA, by either reducing primary to secondary BA converting Clostridium cluster XI or XIVa bacterial strains by antibiotic treatment, or by decreasing 7α-dehydroxylation activity with difructose anhydride III, substantially reduced the development of HCC in obese mice207. In non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) patients, the induction of SASP has been observed, indicating that the DCA-SASP axis may play a role in the development of obesity-associated HCC in humans208. In another experiment involving the incorporation of radiolabeled thymidine into hepatocyte DNA, DCA was found to inhibit DNA synthesis, suggesting that this secondary BA metabolite may affect DNA repair and cellular proliferation209.

Shi et al. (2016) demonstrated the effects of DCA on the gastric epithelial cell line (GES-1) in vitro. Among other factors, DCA downregulated the core histone H2A.1. This histone is involved in chromatin structure, which is important in DNA repair, DNA replication and transcription, and chromosomal stability210. Since obesity has been associated as a risk factor for gastritis211–213 and DCA is upregulated in the obese state, it is plausible that DCA might be a contributing factor to obesity-related gastric cancers.

DCA has also been implicated in the development of Barrett adenocarcinoma. DCA treatment of Barrett’s epithelial cells increased the formation of DSBs as evidenced by γ-H2AX staining, and stimulated the phosphorylation of proteins in the NF-κB signaling pathway214,215. Burnat et al. (2010) found that DCA upregulated NFκB-mediated induction of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and downregulated the DNA repair glycosylases, 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase (OGG1) and MutY glycosylase homologue (MUTYH), in Barrett’s epithelial cancer cells216. These findings suggest that DCA exerts its carcinogenic potential by increasing DNA damage.

1.3.2. Lithocholic acid

LCA, the other major secondary metabolite of BA, is known to function as an oncometabolite. Generally, post synthesis in the liver, most of the primary BA and its secondary metabolites enter the enterohepatic circulation before passing through the small intestine for re-absorption by the intestinal lumen. The unabsorbed metabolites are brought back to the liver for secretion into the bile217. LCA on the contrary, is partly absorbed in the intestine and transits to the colon where it is concentrated, and has been found to be excreted in feces at levels of up to 200 µM218. This may promote tumor initiation in colon epithelial cells by forming adducts with DNA219. Kulkarni et al. (1980) showed that within one hour of treating mouse lymphoblastoma L1210 cells with LCA (at 250 µM), single-strand breaks (SSBs) appeared in DNA, which were subsequently repaired when the cells were incubated in LCA-free media220. Similar results of DNA damage and repair were observed in an LCA-induced insult study in colon epithelium crypt cells involved in colon carcinogenesis221. Treatment of colon cells with LCA over a range of physiologically relevant concentrations (25–300 µM) also led to DNA strand breaks as assessed by comet assays222,223.

LCA can promote methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG)-induced carcinogenesis in rat colon epithelial cells, presumably by inhibiting the base excision repair (BER) enzyme, DNA polymerase β (pol β), which plays an essential role in repairing DNA damage induced by MNNG224,225. The demonstration that BER was inhibited by LCA has provided a possible mechanism for its role as an oncometabolite225,226. LCA is also an inhibitor of topoisomerase II (topo II), which simultaneously breaks and rejoins DNA strands to manage supercoiling during DNA metabolic processes such as DNA repair. Three dimensional computational analysis revealed interaction sites for LCA with pol β at amino acids Lys60, Leu77, and Thr79, and interaction sites for LCA with topo II were identified at Lys720, Leu760, and Thr791227. The identification of these binding sites should prove helpful for the development of selective DNA repair inhibitors in cancer therapy228.

1. DNA Repair

The DNA repair machinery is crucial to maintain genome stability, and thus eukaryotic cells have evolved several highly conserved mechanisms to remove DNA damage229. Depending on the complexity of the damage, the repair proteins/pathways work in a concerted fashion targeting different types of DNA lesions to maintain genome stability. While some lesions involving alkylation of the bases can be reversed by direct methyltransferase repair230, more complex lesions require repair mechanisms that involve a number of proteins that can excise damaged bases and resynthesize DNA. For example, BER removes many types of DNA lesions that result in modification of single bases using specialized DNA glycosylases and apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) endonucleases231. Proteins in the NER pathway process helix-distorting bulky adducts, for example, those created by exposure to UV radiation232. DSBs can be processed by a variety of homologous or non-homologous pathways; for example, breaks with non-homologous ends can be processed via non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) repair mechanisms233, whereas homologous recombination repair (HR) is guided by sequence homology234 often provided by a sister chromatid during S-phase repair. Mismatch repair (MMR) processes base-base mismatches, and small loops or insertion/deletion mispairs generated during replication and recombination235.

Although the molecular mechanisms underlying the obesity-cancer link are poorly understood, there is some mechanistic evidence to suggest that inefficient repair of DNA adducts formed as a result of obesity-induced metabolic changes may contribute to carcinogenesis.

2.1. Repair of oxidative stress-induced DNA lesions

Obesity results in altered lipid homeostasis, cellular oxidative stress, and inflammation that can result in DNA damage and overwhelm or reduce the repair capacity and accuracy of various DNA repair mechanisms. Over time, the accumulation of unrepaired DNA lesions and/or the error-generating repair of DNA lesions can result in mutations and genetic alterations involved in the etiology of many diseases, including cancer236,237.

One of the critical markers of oxidative stress in accumulated fat is elevated levels of Nox4 and ATM class switching from anti-inflammatory to pro-inflammatory cytokines which can stimulate ROS27,53, resulting in the formation of oxidative DNA damage lesions such as 8-oxo-dG18,73. To limit mutagenesis and cytotoxicity, 8-oxo-dG lesions are primarily repaired by OGG1 via the BER mechanism238. OGG1 cleaves the N-glycosidic bond between the sugar and the base, followed by endonucleolytic cleavage and subsequent gap-filling with limited specificity toward the 8-oxo-dG lesions on the daughter strand231. Mutations and gene polymorphisms in the human OGG1 gene have been found to be associated with an increased risk of developing various cancers239. Moreover, mice deficient in OGG1 (OGG1−/−) have been found to accumulate 8-oxo-dG lesions in an age-related and tissue specific manner240. Rozalski et al. (2005) have shown a ~26% reduction in urinary levels of 8-oxo-dG in OGG1−/− mice compared to wild-type mice suggesting the important role of OGG1 glycosylase241.

However, several groups have reported the existence of back-up BER glycosylases242,243. As an example, DNA constructs containing a single 8-oxo-dG lesion incubated in mammalian cell extracts were primarily repaired by BER via pol β-dependent removal and gap-filling of a single nucleotide. However, 8-oxo-dG lesions were also repaired in pol β-deficient cells, suggesting the existence of an alternative pathway(s) for their removal244. Other glycosylases that may be involved in processing 8-oxo-dG include the Nei endonuclease VIII-like or NEIL family of glycosylases (NEIL1, NEIL2, and NEIL3)243,245, and evidence has suggested potential roles for the NER and MMR mechanisms to compensate for deficient OGG1 activity in processing these lesions246,247.

The role of BER glycosylases in modulating cellular and whole body energy homeostasis has been reported. For example, Sampath et al. (2011, 2012) showed that mice deficient in the BER enzymes, DNA glycosylase NEIL1 or OGG1, increased susceptibility to the development of metabolic syndrome248,249. A recent report by the same group indicated protection from diet-induced obesity in mice overexpressing mitochondrial OGG1, further reinforcing the idea that BER plays an important role in body weight regulation250.

GC to TA transversion mutations can result during DNA replication past 8-oxo-dG lesions. Using immunofluorescence experiments in mammalian cells, van Loon and Hϋbscher (2009) demonstrated the involvement of MUTYH in recognizing these lesions. MUTYH generates an apurinic (AP) site, which is subsequently processed by apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1). This is followed by the incorporation of deoxycytidine triphosphate (dCTP) in the single nucleotide gap by DNA pol λ, replication protein A, (RPA), proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), and finally ligation of the DNA strand by DNA ligase I and flap endonuclease 1 (FEN1)251.

Cockayne syndrome group A (CSA) and B (CSB) proteins involved in the transcription-coupled repair sub-pathway of NER (TC-NER) have also been implicated in processing 8-oxo-dG lesions by several groups252–256. Compared to control human cells, primary fibroblasts from CS patients were unable to repair ionizing radiation-induced 8-oxo-dG lesions, suggesting that unrepaired oxidative DNA lesions might contribute to neurodegeneration in CS patients255.

MMR has been reported as an alternative pathway for processing 8-oxo-dG lesions. For example, MMR-deficient mouse cells treated with oxidizing agents or low-dose ionizing radiation showed elevated levels of 8-oxo-dG compared to MMR-proficient wild-type cells257,258. In addition, oxidized purines in MMR-deficient cells have been implicated in frame-shift mutations resulting in microsatellite instability259. Though the precise mechanism is unclear, human MUTSα (a dimer of MSH2 and MSH6) preferentially recognized 8-oxoG-containing duplexes with an unpaired C or T, suggesting a role for MMR in repairing 8-oxo-dG lesions260,261. In response to oxidative stress-induced DNA damage, loss of key MMR genes has been reported. MSH2-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts contained higher levels of both basal and ROS-induced 8-oxo-dG lesions when compared to wild-type cells257.

Unsurprisingly, 8-oxo-dG is also an important biomarker for the prognosis and progression of colorectal cancers (CRC), a risk factor of obesity262, and MMR status is used to classify CRC into different sub-types263. Epigenetic inactivation of the MutL homolog 1, colon cancer, nonpolyposis type 2 (MLH1) gene promoter and germline mutations in the MMR genes resulted in microsatellite instability, which occurs in 10–20% of CRC cases264–268. However, obesity alone presented a poor prognosis for overall survival in patients with CRC, as obese patients were found to be ~40% less likely to have a deficient MMR status compared to normal-weight CRC patients269,270. In fact, obese CRC patients exhibited a prognostically unfavorable proficient MMR molecular subtype characterized with chromosomal instability266,271.

Several groups have reported the mutagenic effects of oxidative stress-induced 8-oxo-dG lesions in DNA regions with repetitive sequences capable of adopting alternative DNA structures. For example, we have observed stimulation of oxidative stress and induction of mutations in and around mirror-repeat sequences capable of forming alternative DNA structures in a diet-induced obese mouse model (Kompella & Vasquez, unpublished, 2019). Other groups have found that when the repair of 8-oxo-dG lesions occurred at or near triplet-repeat sequences such as CAG or CTG or CGG, GCC or GAA, slipped DNA or hairpin structures can form transiently within the sequence, which were improperly processed by the BER machinery272–275, impacting deletion or expansion of the repeats. This error generating repair of 8-oxo-dG within triplet-repeat sequences may be involved in disease etiology, as triplet-repeat expansions have been implicated in many neurological disorders274.

2.2. Repair of lipid peroxidation by-product-induced DNA lesions

The by-products of lipid peroxidation generally have long half-lives and can diffuse from their sites of formation across membranes, thus acting as second messengers of oxidative stress (e.g., 4-HNE)124,276. Their electrophilic nature enables them to react with nucleophilic functional groups in DNA, and sulfhydryl, guanidine and amino groups in proteins277. Aldehydes such as (MDA and 4-HNE) often form covalent mutagenic exocyclic adducts with the free -NH2- in the DNA bases leading to genetic instability, and subsequently contributing to the development of various cancers276.

2.2.1. Malondialdehyde

Chemically stable propanodeoxyguanosine (PdG)-DNA adducts have been used as an in vitro model for unstable M1dG adducts as they are structurally analogous. In both E. coli and mammalian cell systems, PdG-DNA adducts have been shown to be repaired by the NER mechanism278, and that formamidopyrimidine glycosylase or 3-methyladenine glycosylase do not play roles in the removal of M1dG adducts116,278. Transformation of M1dG adduct-containing plasmids in NER-deficient E. coli (LM103) cells resulted in an ~3-fold increase in mutation frequency compared to the NER-proficient wild-type (LM102) cells. Further, without a functional NER system, the half-life of the M1dG adducts was longer, likely contributing to the increased mutagenicity116. Interestingly, when an M1dG adduct-containing plasmid was replicated in human fibroblasts deficient in NER (XP12BE and XP12RO), no increase in mutation frequency was observed relative to NER-proficient wild type cells (GM00637F)115. A possible explanation for this result could be the presence of another repair mechanism in human cells that is capable of removing the M1dG adducts in the absence of NER.

TC-NER has been implicated in the processing of endogenous lipid peroxidation by-products such as 4-HNE279. Thus, a potential role for TC-NER in the processing and repair of M1dG adducts has also been examined. When present in the transcribed strand of a DNA template, M1dG was able to arrest T7 RNA polymerase and mammalian RNA polymerase II (RNAPII). Also, an M1dG adduct opposite to a C posed a stronger block to transcription than when present opposite to a T. These results suggest that M1dG-induced DNA adducts might have negative implications for patients with Cockayne’s syndrome280.

The non-bulky nature of M1dG adducts might prevent them from being efficiently recognized by NER, making them substrates for MMR. Johnson et al. (1999) transfected an M1dG-containing M13 phage vector into MMR-deficient E. coli cells and found them to be recognized by mutator S (MutS), which appeared to compete with NER for processing these lesions. In the absence of MutS, M1dG-DNA adducts were repaired by NER, thereby reducing their mutagenic potential. The researchers used surface plasmon resonance assays and gel mobility shift assays to show that MutS interacted with M1dG when located opposite to T with a similar affinity to a GT mismatch, suggesting that M1dG adducts can also be recognized and repaired by the MMR system281.

Singh et al. (2014) tested the role of the E. coli dioxygenase enzyme, AlkB, in repairing Acr and MDA adducts in single-stranded and double-stranded DNA282. AlkB is an alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent hydroxylase, which is involved in the direct reversal of alkylation damage283. Using high-resolution quadrupole time-of-flight (Q-TOF) mass spectrometry, they found that AlkB repaired MDA-induced single-stranded DNA lesions more efficiently than double-stranded DNA lesions and the repair efficiency depended on the base opposite the lesion282.

2.2.2. 4-Hydroxynonenal

Hydroxynonenal can form bulky exocyclic HNE-dG-DNA adducts that are primarily repaired by the NER mechanism284, as evidenced by significantly higher levels of 4-HNE-dG-induced mutations in NER-deficient human and E. coli cells compared to NER-proficient cells285. Choudhury et al. (2004) demonstrated the efficient repair of HNE-dG adducts in human cell nuclear extracts in a dose and time dependent manner. The NER proteins recognized and repaired HNE-dG adducts more efficiently (~2.4-fold) than UV adducts (the canonical NER substrate), which might explain the relatively low levels of HNE-dG-induced DNA lesions in mammalian cells286.

CSB, a protein required for TC-NER, has been reported to be involved in the processing of HNE-dG lesions. Compared to CSB-proficient wild-type human fibroblast cells (CS1AN/pc3.1-CSBwt), treatment of CSB-deficient human fibroblast cells (CS1AN/pc3.1) with 4-HNE at physiological concentrations (1–10 μM), resulted in hypersensitivity and enhanced sister chromatid exchanges. Endogenous HNE-induced DNA adducts can also elicit DNA replication and transcription arrest. At concentrations of 1–20 μM in vitro, 4-HNE exposure was found to dephosphorylate CSB in a dose-dependent manner, resulting in increased CSB ATPase activity and activation of TC-NER. However, at higher concentrations (100 and 200 μM), 4-HNE significantly inhibited CSB ATPase activity, which led to cell death279. This affect was thought to be due to the formation of direct adducts with the CSB protein. Through Michael adduction, 4-HNE can react with the amino group of lysine, the imidazole group of histidine, and the sulfhydryl group of cysteine107,287,288. If the adducted proteins are part of the DNA repair machinery, then the removal of HNE-dG adducts could be inhibited or inefficient, contributing to cytotoxicity and carcinogenicity. For example, NER was inhibited in in vitro host cell reactivation assays using human colon and lung epithelial cells and cell extracts treated with 4-HNE, BPDE- or UV-damaged DNA, all of which are substrates for NER289.

Winczura et al. (2014) examined the modulation of BER enzymes by 4-HNE. Pre-treatment of the human fibroblast cell line, K21, with physiological concentrations of 4-HNE hypersensitized the cells to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and the alkylating agent, methyl methanesulfonate (MMS). Direct exposure of purified BER enzymes to high concentrations (1–2 mM) of 4-HNE showed inhibitory effects on alkyl-N-purine glycosylase (APNG) and thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG); whereas, OGG1 glycosylase and APE-1 were unaffected. Exposure of 4-HNE pretreated K21 cells to H2O2 and MMS resulted in the accumulation of SSBs, suggesting that 4-HNE also inhibited DNA ligation290.

2.2.3. Acrolein

Acr-dG adducts have been shown to be repaired by the NER pathway in both E. coli and mammalian cells145,291,292. However, the repair kinetics of Acr-dG was shown to be much slower than HNE-dG in human colon cancer cells. This was suggested to be due to the poor excision efficiency of Acr-dG adducts, such that their repair was inhibited in the presence of HNE-dG293. These results support the observation that the in vivo levels of Acr-dG adducts were two orders of magnitude higher than HNE-dG adducts132,144. α-OH-Acr-dG adducts have been found to be better substrates for excision repair than γ-OH-Acr-dG adducts, and thus are repaired more efficiently150. Interestingly, Acr-adducts are repaired by NER proteins in normal human bronchial epithelia (NHBE) cells and normal human lung fibroblasts (NHLF), but treatment of NHBE and NHLF cell lysates with acr decreased the capacity of NER to remove Acr-adducts within the p53 gene and the overall genome of these cells294. Following treatment with Acr, the gene expression levels of XPA, XPC, hOGG1, PMS2 and MLH1 were unaffected, but protein degradation was increased, perhaps via Michael addition with the amino acids lysine, cysteine, and histidine142. These findings suggested that Acr treatment could inhibit NER, BER, and MMR by degradation of repair proteins in these pathways, contributing to its mutagenic and carcinogenic potential291.

In E. coli, Pol I catalyzes the error-free translesion synthesis past Acr-dG adducts, whereas in eukaryotic cells, various translesion synthesis polymerases participate in catalyzing bypass of the Acr-dG adduct, often resulting in mutations292,295. Lee et al. (2014) showed that endogenous (e.g., oxidative stress-induced lipid peroxidation) and exogenous (e.g., tobacco smoke) sources of Acr can cause bladder tumors in a rat model. Treatment of urothelial cells with Acr revealed that it induced degradation of repair proteins, thereby inhibiting the NER and BER pathways, implicating it in tobacco-smoke induced bladder cancers156. Interestingly, a meta-analysis study showed that obesity is associated with an ~10% increase in the risk of bladder cancer296. Though smoking did not seem to play a role, studies on the contribution of obesity-induced increases in oxidative stress-induced Acr levels are required to understand the molecular mechanisms involved in obesity-associated bladder cancers.

Like MDA, Acr-dG adducts can also be repaired by AlkB. Interestingly, the γ-OH-Acr-dG adducts were oxidatively dealkylated more efficiently by AlkB than α-OH-Acr-dG adducts in both open- and closed-ring forms282. Acr was also shown to inhibit DNA polymerase α (Pol α), and influence DNA methylation by either inhibiting the repair enzyme O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyl transferase or DNA methylase by covalently binding to guanine residues and modifying DNA such that it is no longer a substrate for these enzymes297,298.

2.3. Repair of secondary bile acid metabolite-induced DNA lesions

The DNA damaging effects of BA and their metabolites leading to carcinogenesis have been reported29,190–192,299, but their effects on DNA repair mechanisms are not well understood. In Salmonella enterica, bile salts have been reported to induce oxidative SOS responses when the lesions impaired DNA replication, and when single-stranded DNA was generated by BER or dam-directed MMR during the processing of the oxidative DNA lesions. Their repair can generate SSBs which can be converted to DSBs during DNA replication. However, the replication block can be overcome by the dinB polymerase via translesion synthesis, followed by the action of recA, recBCD and PolIV enzymes that repair the DSBs via homologous recombination195,196,300. Bernstein et al. (1999) have observed similar SOS-induced DNA repair responses to bile salts in E. coli301. Importantly, bile salt-induced mutagenesis in bacterial species colonizing the intestine may lead to chronic infection or adaptation giving rise to antibiotic-resistant strains301,302.

Of note, the molecular mechanisms that underlie the cellular responses to BA salts in mouse models do not always mirror the mechanisms found in human carcinogenesis. Factors limiting the applicability of rodent data to humans may be due to: 1) differences in rodent and human gut physiology; 2) the shorter life span of rodents, such that the experimental exposure time is insufficient to recapitulate the long-term effects of BA metabolites in humans; 3) the carcinogenic effects of BA metabolites often manifest at particular sites and under specific physiological conditions; and 4) BA metabolites are carcinogenic in humans, while they show tumorigenic effects in animal studies, suggesting that they may be tumor promoters only and not carcinogens in rodents29,303.

2.3.1. Deoxycholic acid

The bile salt, deoxycholate, has been found to be associated with colon cancer in individuals on a high-fat diet304. To better understand this finding, Romagnolo et al. (2003) treated colon epithelial cells in vitro with sodium deoxycholate at a low non-cytotoxic concentration (10 µM), and found that the expression of BRCA1, which is an important protein for DNA repair and apoptosis, was induced; whereas, at higher cytotoxic concentrations (≥100 µM) of sodium deoxycholate, BRCA1 expression was inhibited. These observations correlated with BRCA1 gene expression levels in colon cancer patients, suggesting that clonal selection of colon epithelial cells resistant to apoptosis (in part due to BA-induced loss of BRCA1) contributed to colon carcinogenesis305.

Kandell et al. (1991) demonstrated the induction of unscheduled DNA repair synthesis when human fore-skin fibroblasts were exposed to CDCA and DCA. In addition, UV4 CHO cells deficient in excision repair and DNA crosslink removal were more sensitive to sodium chenodeoxycholate than wild-type cells, and EM9 CHO cells deficient in single-strand DNA repair were more sensitive to sodium deoxycholate than wild-type cells299. In response to sodium-deoxycholate-induced DNA damage, human Jurkat cells and rat epithelial cells were found to overexpress the stress response proteins NFκB and poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP), thereby facilitating DNA repair and protecting the cells from bile-salt induced apoptosis306. Conversely, Glinghammar et al. (2002) showed that the treatment of human HCT 116 and HT-29 colon cancer cells with DCA led to the activation of caspase-3 and cleavage of PARP, subsequently resulting in apoptosis199.

The exposure of Barrett’s epithelial cells to DCA was shown to increase the production of ROS215. Among other cellular changes, this led to the accumulation of oxidative DNA damage-induced mutations, perhaps contributing to the etiology of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). Recently, Hong et al. (2016) investigated the role of the BER protein, APE1, on the survival of mutant p53 EAC cells in response to BA. They found that overexpression of APE1 in EAC cells suppressed BA-induced DSBs, perhaps by enhancing BER and regulating stress responses, which reduced JNK- and p38-associated apotposis307.

2.3.2. Lithocholic acid

LCA is a potent inhibitor of Polβ, a key enzyme required for the BER mechanism226,228, and other DNA polymerase enzymes (Pol α, Pol δ, Pol ε) involved in DNA replication and repair226. Inefficient BER can result in intermediates that require BRCA2-dependent HR for their repair. Stachelek et al. (2010) found that LCA reduced the efficiency of BER by inhibiting Polβ in EUFA423 BRCA2-deficient human fibroblasts. LCA was found to inhibit the formation of a stable pol β–DNA complex, thereby suppressing the DNA polymerase and 5′-deoxyribose phosphate lyase activities of pol β. These effects were synergistic with the cytotoxic effects of the alkylating agent temozolomide, which can methylate guanine residues in DNA. This synergism depended on the conversion of BER-induced SSBs into DSBs during replication, as evidenced by γH2AX immunofluorescence. Co-treatment with LCA and temozolomide eventually led to cell death likely due to the accumulation of unrepaired DSBs in BRCA2-deficient cells, suggesting that BRCA2-deficient cancers may be an attractive target for synergistic drug therapy308.

2. Obesity-induced epigenetic changes

Several studies have been published on the role of epigenetics in the etiology of obesity. It is only recently that we have begun to understand that the obesogenic state, apart from eliciting a DNA damage and repair response, can also result in epigenetic alterations. Studies have shown that our environment influences changes in gene expression, sometimes leading to the onset of disease, but due to genome-wide epigenetic reprogramming, the trans-generational inheritance of these changes is not well defined309.

Epigenetic marks are tissue specific and include DNA methylation and histone modifications. Since all the tissues in the body depend on the uptake of glucose and lipids, their cellular states are affected directly or indirectly by increases in the nutrient levels during obesity. As mentioned previously, in the adipose tissue the increase in lipids is accommodated via hyperplasia under the regulation of the adipogenic transcription factor C/EBPβ. During adipocyte differentiation, C/EBPβ can be hypermethylated whereas, the promoter region of the fatty acid storage regulator, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), can be hypomethylated310. There is evidence that histone deacetylases (HDACs) are also involved in adipocyte differentiation. Specifically, HDAC9 was found to negatively regulate adipogenesis in a deacetylase-independent manner311. Rodents fed on a HFD have been shown to undergo chromatin modifications in the liver and at regulatory regions near genes associated with metabolism and insulin signaling312,313.

Mendelson et al. (2017) performed a microarray-based analysis of DNA from whole blood samples from 3,743 adult participants to study the association between BMI and differential methylation over 400,000 CpG sites. They identified BMI-related differential methylation at 83 of these CpG sites (replicating across cohorts), which were associated with concurrent expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism314. Though the cross-sectional nature of the data makes it difficult to draw causal relationships between BMI and DNA methylation, the results provide evidence to warrant further investigation to establish the mechanistic relationship between the two. Other research groups have performed similar epigenome-wide association studies in human blood samples from a variety of study cohorts with similar results30,315. Interestingly, Wahl et al. (2017) using methylation array analyses of blood and tissue samples from 5,387 individuals, identified 187 CpG sites with altered methylation patterns that were associated with BMI. These methylation changes led to alterations in the expression of several genes involved in lipid metabolism, substrate transport, and inflammation. They also identified 62 markers that were associated with Type II Diabetes (T2DM), with one marker in the ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily G Member 1 (ABCG1) locus involved in insulin secretion and β-cell function showing the strongest association. This association was observed to be independent of the canonical T2DM risk factors, supporting the authors’ view that changes in obesity-related DNA methylation might represent a predictive measure for obesity-related disorders, such as T2DM30.

Obesity associated reprogramming of the epigenome via DNA methylation may alter the expression of genes that inhibit tumor progression thereby increasing cancer risk. As an example, the epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor genes by estrogen in mammary epithelial cells in obese women may contribute to the development of or drive the progression of breast cancer31. Similarly, obesity-induced dysregulation of DNA methylation in endometrial epithelial cells may result in endometrial cancer development in obese women32.

Conclusions

The dearth of studies correlating DNA damage, DNA repair, genetic instability and cancer in overweight or obese humans (or in non-human animal models) makes it challenging to draw direct causal links. However, the available mechanistic studies have proved useful in postulating hitherto unexplained obesity-cancer links via genetic instability.

Many gaps in knowledge still exist as to which stage(s) of increases in body weight initiate cellular responses leading to increases in oxidative stress, and subsequent DNA lesion formation and DNA damage responses. Information is limited regarding the consequences of obesity-associated DNA damage on oncogenes and malignant transformation of cells. Studies utilizing genetic and/or diet-induced obesity animal models deficient in, or overexpressing a specific DNA repair protein, will assist in a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the obesity-cancer link. Further research focus is also needed to investigate the association between oxidative DNA damage and modification of DNA methylation during obesity. Information provided by such studies will assist in the design of personalized therapies targeted to specific pathways involved in DNA damage, DNA repair, epigenetic modifications, and genetic instability associated with obesity. As we and many other research groups continue to investigate obesity-induced genetic instability and its potential contribution to cancer development, the findings will assist in the development of improved therapeutic strategies for the prevention and treatment of obesity-related cancers.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an NIH/NCI grant (CA225029) to KMV and an American Foundation for Pharmaceutical Education Pre-Doctoral Fellowship to PK.

Grant Support: National Institute of Health / National Cancer Institute.

Grant Number: R01-CA225029.

Abbreviations

- OH

hydroxyl radical

- 4-HNE

4-hydroxynonenal

- 5-mC

5’-methyl-cytosine

- 8-OH-dG

8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine

- 8-oxo-dG

8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine

- ABCG1

ATP binding cassette subfamily G member 1

- Acr

acrolein

- AP

apurinic/apyrimidinic

- APE-1

apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1

- APNG

alkyl-N-purine glycosylase

- ATM

adipose tissue macrophage

- BA

bile acids

- BER

base excision repair

- BMI

body mass index

- BPDE

Benzo(a)pyrene diol epoxide

- C/EBPβ

CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-β

- CA

cholic acid

- CDCA

chenodeoxycholic acid

- CHO

chinese hamster ovary

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- CRC

colorectal cancers

- CSA

cockayne syndrome group A

- CSB

cockayne syndrome group B

- CXCL-9

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9

- DCA

deoxycholic acid

- dCTP

deoxycytidine triphosphate

- DPCs

DNA-protein crosslinks

- DSBs

DNA double-strand breaks

- E.Coli

Escherichia coli

- EAC

esophageal adenocarcinoma

- FEN-1

flap endonuclease 1

- FLT3-ITD

FMS-like tyrosine kinase receptor

- FXR

farnesoid X receptor

- Gro-α

growth-regulated oncogene-alpha

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HDACs

histone deacetylases

- HFD

high fat diet

- HNE-dG

6-(1-hydroxyhexanyl)-8-hydroxy-1,N(2)-propano-2’-deoxyguanosine

- HR

homologous recombination repair

- HSCs

hepatic stellate cells

- ICLs

inter-strand crosslinks

- IFN-γ

interferon gamma

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor 1

- IKKβ

Inhibitor of kappa B kinase beta

- IL

interleukin

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LCA

lithocholic acid

- M1dG

3-(2-deoxy-β-d-erythro-pentofuranosyl)pyrimido[1,2-α]purin-10(3H)-one deoxygunanosine

- MCA

muricholic acid

- MCP-1

monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- MDA

malondialdehyde

- MLH1

MutL homolog 1 colon cancer, nonpolyposis type 2

- MMR

mismatch repair

- MMS

methyl methanesulfonate

- MNNG

methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine

- MutS

mutator S

- MUTYH

mutY glycosylase homologue

- NAFLD

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- NEIL

nei endonuclease VIII-like

- NER

nucleotide excision repair

- NFκB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- NHBE

normal human bronchial epithelia

- NHEJ

non-homologous end-joining

- NHLF

normal human lung fibroblasts

- Nox 4

NADPH oxidase 4

- O2•

superoxide radical

- OGG1

8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase

- PARP

poly ADP ribose polymerase

- PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- PdG

propanodeoxyguanosine

- Pol α

DNA polymerase α

- Pol β

DNA polymerase β

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma

- PUFA

polyunsaturated fatty acids

- PXR

pregnane X receptor

- Q-TOF

high-resolution quadrupole time-of-flight

- RNAPII

RNA polymerase II

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RPA

replication protein A

- SASP

senescence-associated secretory phenotype

- SSBs

single-strand breaks

- T2DM

type II diabetes

- TC-NER

transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair

- TDG

thymine DNA glycosylase

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- topo II

topoisomerase II

- VDR

vitamin D receptor

- XPA

xeroderma pigmentosum complement group A

- α-OH-Acr-dG

α-hydroxy-1,N2-propano-2′-deoxyguanosine

- γ-OH-Acr-dG

γ-hydroxy-1,N2-propano-2′-deoxyguanosine

- μM

micromolar

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

The authors disclose that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.WHO. Global health risks : mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks Geneva: : World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014;384(9945):766–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garrow JS, Webster J. Quetelet’s index (W/H2) as a measure of fatness. Int J Obes 1985;9(2):147–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collaborators GBDO, Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, et al. Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years. N Engl J Med 2017;377(1):13–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Degirmenci T, Kalkan-Oguzhanoglu N, Sozeri-Varma G, Ozdel O, Fenkci S. Psychological Symptoms in Obesity and Related Factors. Noro Psikiyatr Ars 2015;52(1):42–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon GE, Von Korff M, Saunders K, et al. Association between obesity and psychiatric disorders in the US adult population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63(7):824–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative Expert Panel on the Identification E, and Treatment of Obesity in Adults (US). Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: The Evidence Report Bethesda (MD): National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 1998. Sep. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J, Chi M, Chen C, Zhang XD. Obesity and melanoma: exploring molecular links. J Cell Biochem 2013;114(9):1955–1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Pergola G, Silvestris F. Obesity as a major risk factor for cancer. J Obes 2013;2013:291546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, et al. Body Fatness and Cancer--Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med 2016;375(8):794–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet 2008;371(9612):569–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnold M, Pandeya N, Byrnes G, et al. Global burden of cancer attributable to high body-mass index in 2012: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 2015;16(1):36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fenton JI, Nunez NP, Yakar S, Perkins SN, Hord NG, Hursting SD. Diet-induced adiposity alters the serum profile of inflammation in C57BL/6N mice as measured by antibody array. Diabetes Obes Metab 2009;11(4):343–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaaks R. Nutrition, insulin, IGF-1 metabolism and cancer risk: a summary of epidemiological evidence. Novartis Found Symp 2004;262:247–260; discussion 260–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Booth A, Magnuson A, Fouts J, Foster M. Adipose tissue, obesity and adipokines: role in cancer promotion. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 2015;21(1):57–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siiteri PK. Adipose tissue as a source of hormones. Am J Clin Nutr 1987;45(1 Suppl):277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Louie SM, Roberts LS, Nomura DK. Mechanisms linking obesity and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013;1831(10):1499–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cerdá C, Sánchez C, Climent B, et al. Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage in Obesity-Related Tumorigenesis. In: Camps J, ed. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Non-communicable Diseases - Molecular Mechanisms and Perspectives in Therapeutics Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2014:5–17. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sam S, Mazzone T. Adipose tissue changes in obesity and the impact on metabolic function. Transl Res 2014;164(4):284–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cozzo AJ, Fuller AM, Makowski L. Contribution of Adipose Tissue to Development of Cancer. Compr Physiol 2017;8(1):237–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lengyel E, Makowski L, DiGiovanni J, Kolonin MG. Cancer as a Matter of Fat: The Crosstalk between Adipose Tissue and Tumors. Trends Cancer 2018;4(5):374–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krstic J, Reinisch I, Schupp M, Schulz TJ, Prokesch A. p53 Functions in Adipose Tissue Metabolism and Homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Labuschagne CF, Zani F, Vousden KH. Control of metabolism by p53 - Cancer and beyond. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2018;1870(1):32–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zwezdaryk K, Sullivan D, Saifudeen Z. The p53/Adipose-Tissue/Cancer Nexus. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018;9:457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Usman M, Volpi EV. DNA damage in obesity: Initiator, promoter and predictor of cancer. Mutat Res 2018;778:23–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Setayesh T, Nersesyan A, Misik M, et al. Impact of obesity and overweight on DNA stability: Few facts and many hypotheses. Mutat Res 2018;777:64–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furukawa S, Fujita T, Shimabukuro M, et al. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest 2004;114(12):1752–1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burcham PC. Genotoxic lipid peroxidation products: their DNA damaging properties and role in formation of endogenous DNA adducts. Mutagenesis 1998;13(3):287–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernstein H, Bernstein C, Payne CM, Dvorakova K, Garewal H. Bile acids as carcinogens in human gastrointestinal cancers. Mutat Res 2005;589(1):47–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wahl S, Drong A, Lehne B, et al. Epigenome-wide association study of body mass index, and the adverse outcomes of adiposity. Nature 2017;541(7635):81–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coleman WB. Obesity and the breast cancer methylome. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2016;31:104–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagashima M, Miwa N, Hirasawa H, Katagiri Y, Takamatsu K, Morita M. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis in obese women predicts an epigenetic signature for future endometrial cancer. Sci Rep 2019;9(1):6469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bayr H Reactive oxygen species. Critical Care Medicine 2005;33(12):S498–S501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sies H, Cadenas E. Oxidative stress: damage to intact cells and organs. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1985;311(1152):617–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu BP. Cellular defenses against damage from reactive oxygen species. Physiol Rev 1994;74(1):139–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Betteridge DJ. What is oxidative stress? Metabolism 2000;49(2 Suppl 1):3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rani V, Deep G, Singh RK, Palle K, Yadav UC. Oxidative stress and metabolic disorders: Pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Life Sci 2016;148:183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grattagliano I, Palmieri VO, Portincasa P, Moschetta A, Palasciano G. Oxidative stress-induced risk factors associated with the metabolic syndrome: a unifying hypothesis. J Nutr Biochem 2008;19(8):491–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khan NI, Naz L, Yasmeen G. Obesity: an independent risk factor for systemic oxidative stress. Pak J Pharm Sci 2006;19(1):62–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rzheshevsky AV. Fatal “Triad”: Lipotoxicity, oxidative stress, and phenoptosis. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2013;78(9):991–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spalding KL, Arner E, Westermark PO, et al. Dynamics of fat cell turnover in humans. Nature 2008;453(7196):783–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gray SL, Vidal-Puig AJ. Adipose tissue expandability in the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis. Nutr Rev 2007;65(6 Pt 2):S7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gustafson B, Hedjazifar S, Gogg S, Hammarstedt A, Smith U. Insulin resistance and impaired adipogenesis. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2015;26(4):193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prieur X, Mok CY, Velagapudi VR, et al. Differential lipid partitioning between adipocytes and tissue macrophages modulates macrophage lipotoxicity and M2/M1 polarization in obese mice. Diabetes 2011;60(3):797–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bing C Is interleukin-1beta a culprit in macrophage-adipocyte crosstalk in obesity? Adipocyte 2015;4(2):149–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fernandez-Sanchez A, Madrigal-Santillan E, Bautista M, et al. Inflammation, oxidative stress, and obesity. Int J Mol Sci 2011;12(5):3117–3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galassetti P. Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, and Diabetes. Experimental Diabetes Research 2012;2012:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ouchi N, Parker JL, Lugus JJ, Walsh K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2011;11(2):85–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Panee J Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein 1 (MCP-1) in obesity and diabetes. Cytokine 2012;60(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Luca C, Olefsky JM. Inflammation and insulin resistance. FEBS Lett 2008;582(1):97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kang YE, Kim JM, Joung KH, et al. The Roles of Adipokines, Proinflammatory Cytokines, and Adipose Tissue Macrophages in Obesity-Associated Insulin Resistance in Modest Obesity and Early Metabolic Dysfunction. PLoS One 2016;11(4):e0154003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tilg H, Moschen AR. Inflammatory mechanisms in the regulation of insulin resistance. Mol Med 2008;14(3–4):222–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chapple IL. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidants in inflammatory diseases. J Clin Periodontol 1997;24(5):287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Valko M, Rhodes CJ, Moncol J, Izakovic M, Mazur M. Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chem Biol Interact 2006;160(1):1–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Houstis N, Rosen ED, Lander ES. Reactive oxygen species have a causal role in multiple forms of insulin resistance. Nature 2006;440(7086):944–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Findeisen HM, Pearson KJ, Gizard F, et al. Oxidative stress accumulates in adipose tissue during aging and inhibits adipogenesis. PLoS One 2011;6(4):e18532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gummersbach C, Hemmrich K, Kroncke KD, Suschek CV, Fehsel K, Pallua N. New aspects of adipogenesis: radicals and oxidative stress. Differentiation 2009;77(2):115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee H, Lee YJ, Choi H, Ko EH, Kim JW. Reactive oxygen species facilitate adipocyte differentiation by accelerating mitotic clonal expansion. J Biol Chem 2009;284(16):10601–10609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Galinier A, Carriere A, Fernandez Y, et al. Adipose tissue proadipogenic redox changes in obesity. J Biol Chem 2006;281(18):12682–12687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]