Abstract

Background

Dental caries (tooth decay) and periodontal diseases (gingivitis and periodontitis) affect the majority of people worldwide, and treatment costs place a significant burden on health services. Decay and gum disease can cause pain, eating and speaking difficulties, low self‐esteem, and even tooth loss and the need for surgery. As dental plaque is the primary cause, self‐administered daily mechanical disruption and removal of plaque is important for oral health. Toothbrushing can remove supragingival plaque on the facial and lingual/palatal surfaces, but special devices (such as floss, brushes, sticks, and irrigators) are often recommended to reach into the interdental area.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of interdental cleaning devices used at home, in addition to toothbrushing, compared with toothbrushing alone, for preventing and controlling periodontal diseases, caries, and plaque. A secondary objective was to compare different interdental cleaning devices with each other.

Search methods

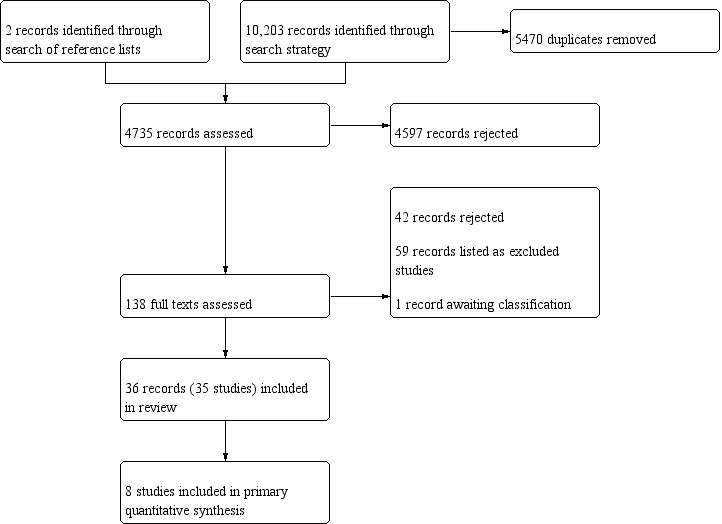

Cochrane Oral Health’s Information Specialist searched: Cochrane Oral Health’s Trials Register (to 16 January 2019), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (the Cochrane Library, 2018, Issue 12), MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 16 January 2019), Embase Ovid (1980 to 16 January 2019) and CINAHL EBSCO (1937 to 16 January 2019). The US National Institutes of Health Trials Registry (ClinicalTrials.gov) and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform were searched for ongoing trials. No restrictions were placed on the language or date of publication.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared toothbrushing and a home‐use interdental cleaning device versus toothbrushing alone or with another device (minimum duration four weeks).

Data collection and analysis

At least two review authors independently screened searches, selected studies, extracted data, assessed studies' risk of bias, and assessed evidence certainty as high, moderate, low or very low, according to GRADE. We extracted indices measured on interproximal surfaces, where possible. We conducted random‐effects meta‐analyses, using mean differences (MDs) or standardised mean differences (SMDs).

Main results

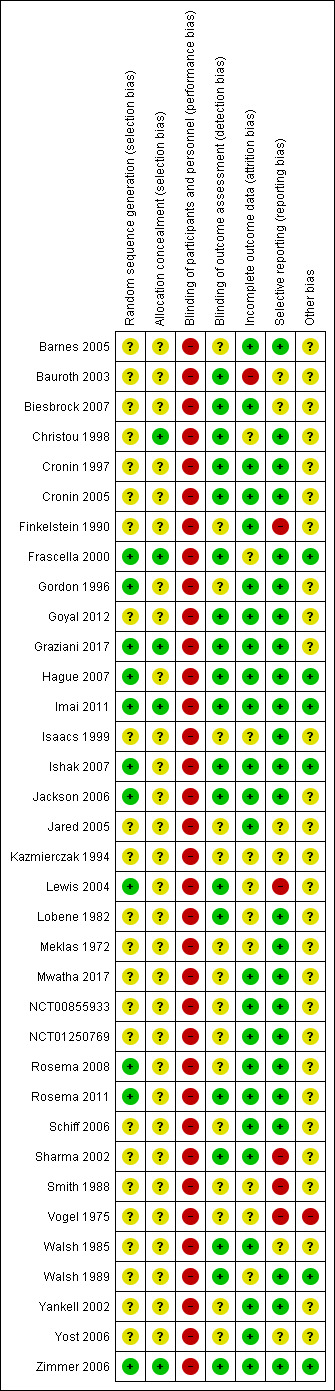

We included 35 RCTs (3929 randomised adult participants). Studies were at high risk of performance bias as blinding of participants was not possible. Only two studies were otherwise at low risk of bias. Many participants had a low level of baseline gingival inflammation.

Studies evaluated the following devices plus toothbrushing versus toothbrushing: floss (15 trials), interdental brushes (2 trials), wooden cleaning sticks (2 trials), rubber/elastomeric cleaning sticks (2 trials), oral irrigators (5 trials). Four devices were compared with floss: interdental brushes (9 trials), wooden cleaning sticks (3 trials), rubber/elastomeric cleaning sticks (9 trials) and oral irrigators (2 trials). Another comparison was rubber/elastomeric cleaning sticks versus interdental brushes (3 trials).

No trials assessed interproximal caries, and most did not assess periodontitis. Gingivitis was measured by indices (most commonly, Löe‐Silness, 0 to 3 scale) and by proportion of bleeding sites. Plaque was measured by indices, most often Quigley‐Hein (0 to 5).

Primary objective: comparisons against toothbrushing alone

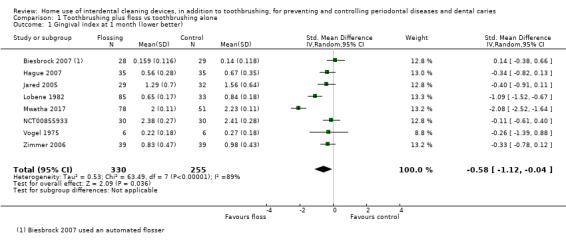

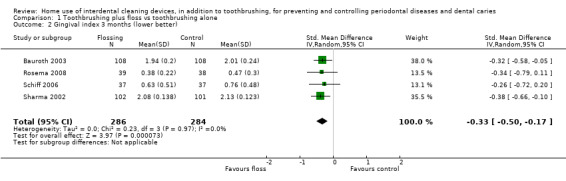

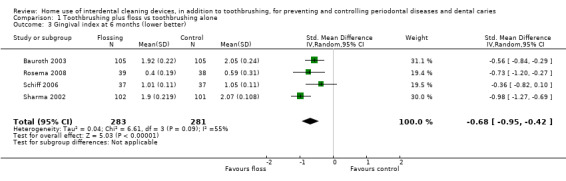

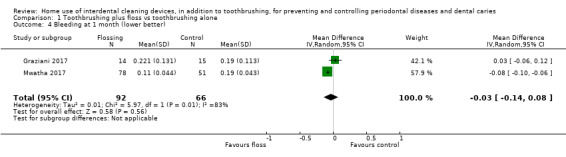

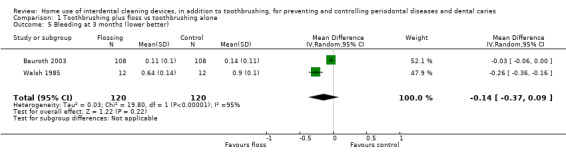

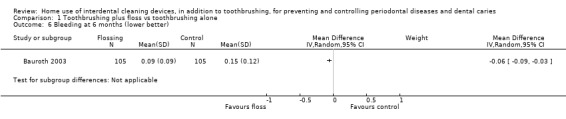

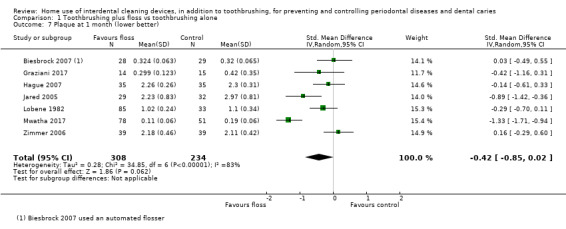

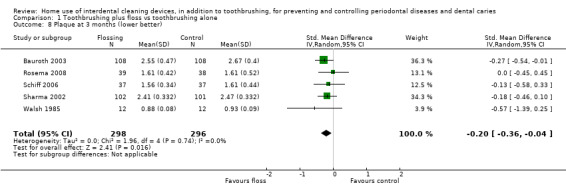

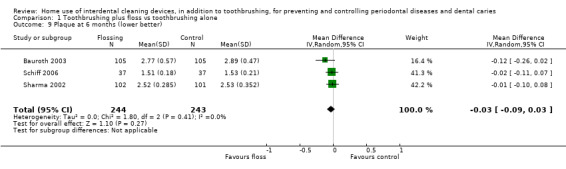

Low‐certainty evidence suggested that flossing, in addition to toothbrushing, may reduce gingivitis (measured by gingival index (GI)) at one month (SMD ‐0.58, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐1.12 to ‐0.04; 8 trials, 585 participants), three months or six months. The results for proportion of bleeding sites and plaque were inconsistent (very low‐certainty evidence).

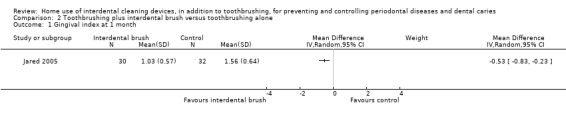

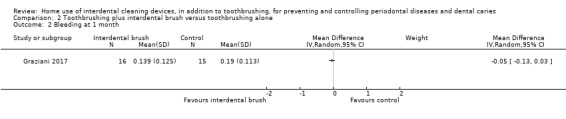

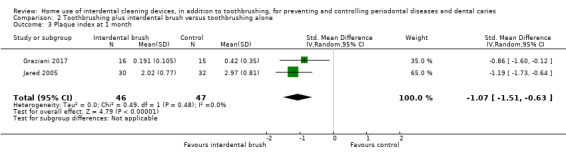

Very low‐certainty evidence suggested that using an interdental brush, plus toothbrushing, may reduce gingivitis (measured by GI) at one month (MD ‐0.53, 95% CI ‐0.83 to ‐0.23; 1 trial, 62 participants), though there was no clear difference in bleeding sites (MD ‐0.05, 95% CI ‐0.13 to 0.03; 1 trial, 31 participants). Low‐certainty evidence suggested interdental brushes may reduce plaque more than toothbrushing alone (SMD ‐1.07, 95% CI ‐1.51 to ‐0.63; 2 trials, 93 participants).

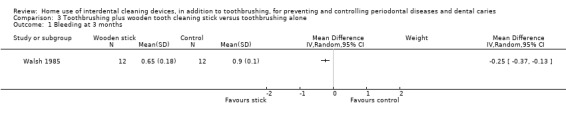

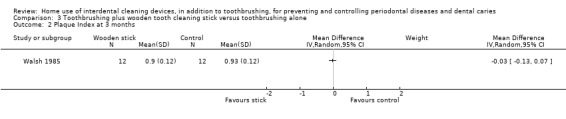

Very low‐certainty evidence suggested that using wooden cleaning sticks, plus toothbrushing, may reduce bleeding sites at three months (MD ‐0.25, 95% CI ‐0.37 to ‐0.13; 1 trial, 24 participants), but not plaque (MD ‐0.03, 95% CI ‐0.13 to 0.07).

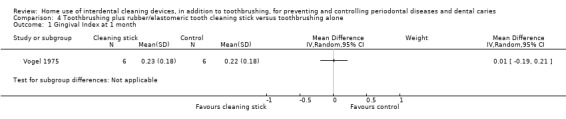

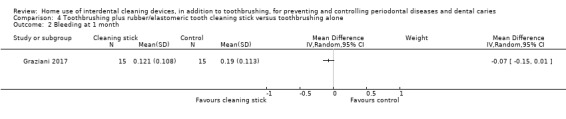

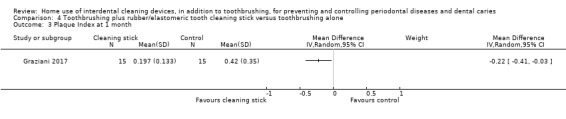

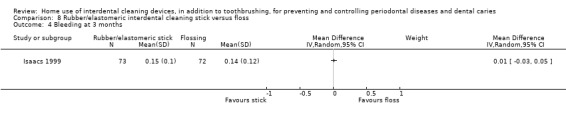

Very low‐certainty evidence suggested that using rubber/elastomeric interdental cleaning sticks, plus toothbrushing, may reduce plaque at one month (MD ‐0.22, 95% CI ‐0.41 to ‐0.03), but this was not found for gingivitis (GI MD ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.21; 1 trial, 12 participants; bleeding MD 0.07, 95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.01; 1 trial, 30 participants).

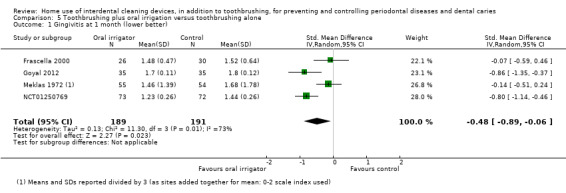

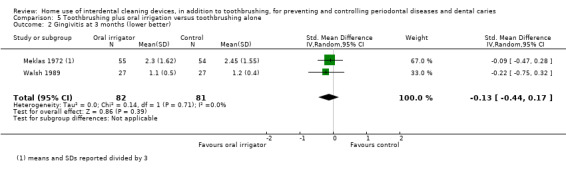

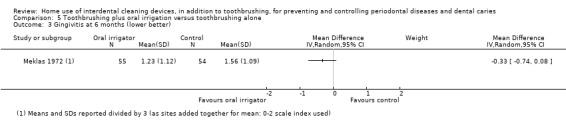

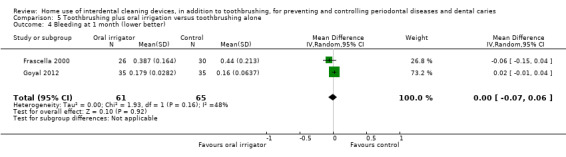

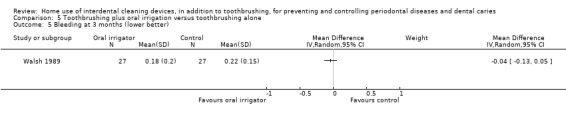

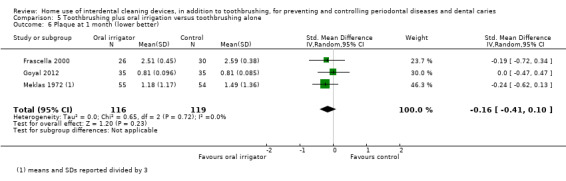

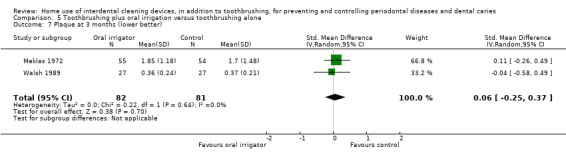

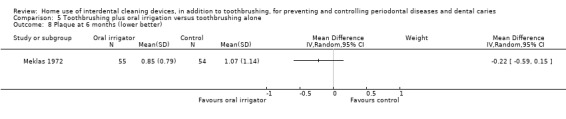

Very‐low certainty evidence suggested oral irrigators may reduce gingivitis measured by GI at one month (SMD ‐0.48, 95% CI ‐0.89 to ‐0.06; 4 trials, 380 participants), but not at three or six months. Low‐certainty evidence suggested that oral irrigators did not reduce bleeding sites at one month (MD ‐0.00, 95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.06; 2 trials, 126 participants) or three months, or plaque at one month (SMD ‐0.16, 95% CI ‐0.41 to 0.10; 3 trials, 235 participants), three months or six months, more than toothbrushing alone.

Secondary objective: comparisons between devices

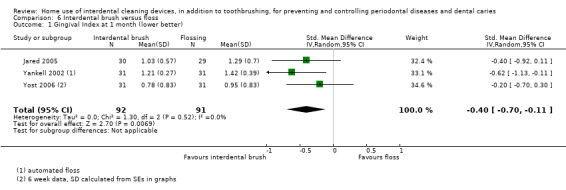

Low‐certainty evidence suggested interdental brushes may reduce gingivitis more than floss at one and three months, but did not show a difference for periodontitis measured by probing pocket depth. Evidence for plaque was inconsistent.

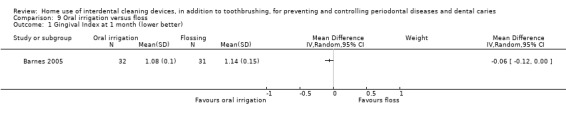

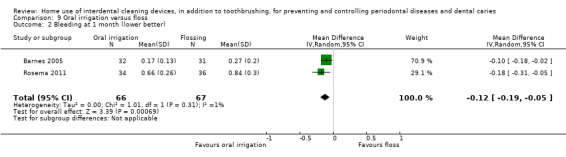

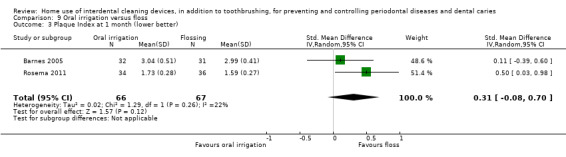

Low‐ to very low‐certainty evidence suggested oral irrigation may reduce gingivitis at one month compared to flossing, but very low‐certainty evidence did not suggest a difference between devices for plaque.

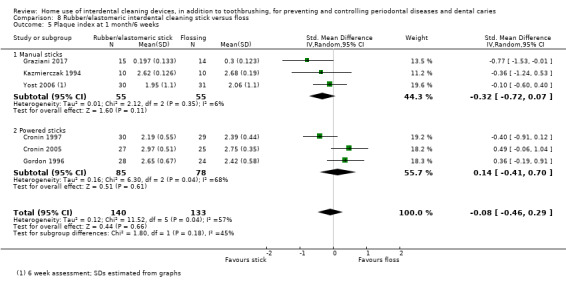

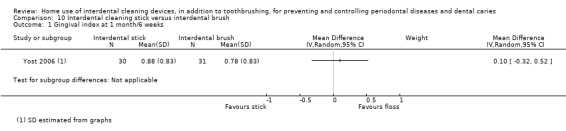

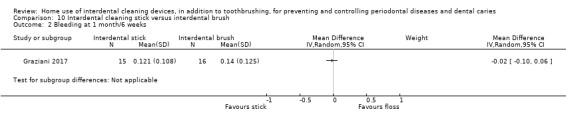

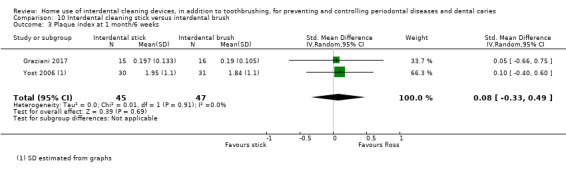

Very low‐certainty evidence for interdental brushes or flossing versus interdental cleaning sticks did not demonstrate superiority of either intervention.

Adverse events

Studies that measured adverse events found no severe events caused by devices, and no evidence of differences between study groups in minor effects such as gingival irritation.

Authors' conclusions

Using floss or interdental brushes in addition to toothbrushing may reduce gingivitis or plaque, or both, more than toothbrushing alone. Interdental brushes may be more effective than floss. Available evidence for tooth cleaning sticks and oral irrigators is limited and inconsistent. Outcomes were mostly measured in the short term and participants in most studies had a low level of baseline gingival inflammation. Overall, the evidence was low to very low‐certainty, and the effect sizes observed may not be clinically important. Future trials should report participant periodontal status according to the new periodontal diseases classification, and last long enough to measure interproximal caries and periodontitis.

Keywords: Humans; Dental Devices, Home Care; Dental Caries; Dental Caries/prevention & control; Dental Plaque; Dental Plaque/prevention & control; Gingivitis; Gingivitis/prevention & control; Oral Health; Periodontal Diseases; Periodontal Diseases/prevention & control; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Home use of devices for cleaning between the teeth (in addition to toothbrushing) to prevent and control gum diseases and tooth decay

Review question

How effective are home‐use interdental cleaning devices, plus toothbrushing, compared with toothbrushing only or use of another device, for preventing and controlling periodontal (gum) diseases (gingivitis and periodontitis), tooth decay (dental caries) and plaque?

Background

Tooth decay and gum diseases affect most people. They can cause pain, difficulties with eating and speaking, low self‐esteem, and, in extreme cases, may lead to tooth loss and the need for surgery. The cost to health services of treating these diseases is very high.

As dental plaque (a layer of bacteria in an organic matrix that forms on the teeth) is the root cause, it is important to remove plaque from teeth on a regular basis. While many people routinely brush their teeth to remove plaque up to the gum line, it is difficult for toothbrushes to reach into areas between teeth ('interdental'), so interdental cleaning is often recommended as an extra step in personal oral hygiene routines. Different tools can be used to clean interdentally, such as dental floss, interdental brushes, tooth cleaning sticks, and water pressure devices known as oral irrigators.

Study characteristics

Review authors working with Cochrane Oral Health searched for studies up to 16 January 2019. We identified 35 studies (3929 adult participants). Participants knew that they were in an experiment, which might have affected their teeth cleaning or eating behaviour. Some studies had other problems that might make their findings less reliable, such as people dropping out of the study or not using the assigned device.

Studies evaluated the following devices plus toothbrushing compared to toothbrushing only: floss (15 studies), interdental brushes (2 studies), wooden cleaning sticks (2 studies), rubber/elastomeric cleaning sticks (2 studies) and oral irrigators (5 studies). Four devices were compared with floss: interdental brushes (9 studies), wooden cleaning sticks (3 studies), rubber/elastomeric cleaning sticks (9 studies), oral irrigators (2 studies). Three studies compared rubber/elastomeric cleaning sticks with interdental brushes.

No studies evaluated decay, and few evaluated severe gum disease. Outcomes were measured at short (one month to six weeks) and medium term (three and six months).

Key results

We found that using floss, in addition to toothbrushing, may reduce gingivitis in the short and medium term. It is unclear if it reduces plaque.

Using an interdental brush, in addition to a toothbrush, may reduce gingivitis and plaque in the short term.

Using wooden tooth cleaning sticks may be better than toothbrushing only for reducing gingivitis (measured by bleeding sites) but not plaque in the medium term (only 24 participants).

Using a tooth cleaning stick made of rubber or an elastomer may be better than toothbrushing only for reducing plaque but not gingivitis in the short term (only 30 participants).

Toothbrushing plus oral irrigation (water pressure) may reduce gingivitis in the short term, but there was no evidence for this in the medium term. There was no evidence of a difference in plaque.

Interdental brushes may be better than flossing for gingivitis at one and three months. The evidence for plaque is inconsistent. There was no evidence of a difference between the devices for periodontitis measured by probing pocket depth.

There is some evidence that oral irrigation may be better than flossing for reducing gingivitis (but not plaque) in the short term.

The available evidence for interdental cleaning sticks did not show them to be better or worse than floss or interdental brushes for controlling gingivitis or plaque.

The studies that measured 'adverse events' found no serious effects and no evidence of differences between study groups in minor effects such as gum irritation.

Certainty of the evidence

The evidence is low to very low‐certainty. The effects observed may not be clinically important. Studies measured outcomes mostly in the short term and many participants had a low level of gum disease at the beginning of the studies.

Future research

Future studies should use the new periodontal diseases classification to describe the gum health of participants, and they should last long enough to measure periodontitis and tooth decay.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Flossing plus toothbrushing compared with toothbrushing alone for periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults.

| Flossing plus toothbrushing for periodontal disease and dental caries in adults | ||||||

|

Population: adults, 16 years and older

Setting: everyday self‐care

Intervention: flossing plus toothbrushing Comparison: toothbrushing only | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Toothbrushing only | Flossing plus toothbrushing | |||||

|

Gingivitis measured by gingival index SD units: investigators measured gingivitis using different scales Lower score means less severe gingivitis Follow‐up: 1 month |

The gingivitis score in the flossing group was on average 0.58 SDs lower (95% CI 0.04 lower to 1.12 lower) than the control group | ‐ | 585 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | Flossing also reduced gingivitis at 3 months (‐0.33, ‐0.50 to ‐0.17, 4 studies, 570 participants) and 6 months (‐0.68, ‐0.95 to ‐0.42, 4 studies, 564 participants). | |

|

Gingivitis measured by proportion of bleeding sites Follow‐up: 1 month |

The median score in the control group was 0.16 | The mean score in the intervention group was 0.03 less (0.14 less to 0.08 more) | ‐ | 158 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2 | 3‐month follow‐up: ‐0.14 (‐0.37 to 0.09, 2 studies, 240 participants) 6‐month follow‐up: ‐0.06 (‐0.09 to ‐0.03; 1 study, 210 participants) |

| Periodontitis | One study measured probing pocket depth but no data were reported. | |||||

| Interproximal caries | No included study assessed caries as an outcome. | |||||

|

Plaque SD units: investigators measured plaque using different scales Lower score means less plaque Follow‐up: 1 month |

The plaque score in flossing group was on average 0.42 SDs lower (0.85 lower to 0.02 higher) than the control group | ‐ | 542 (7 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2 | Significant difference found for plaque at 3 months (SMD 0.20, ‐0.36 to ‐0.04, 5 studies, 594 participants), but not at 6 months (‐0.13, ‐0.30 to 0.05, 3 studies, 487 participants). | |

| Harms and adverse effects | Adverse effects were assessed and reported in seven studies. Three reported no adverse events on the oral hard or soft tissues. Four reported sporadic adverse events with mild severity, with no evidence of a difference between the flossing plus toothbrushing group and toothbrushing only group. | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; SD: standard deviation;SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgraded two levels due to high and unclear risk of bias in the studies and substantial heterogeneity

2 Downgraded three levels due to high and unclear risk of bias in the studies, substantial heterogeneity and lack of precision in the estimate

Summary of findings 2. Interdental brushing with toothbrushing compared to toothbrushing alone for periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults.

| Interdental brushing for periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults | ||||||

| Population: adults, 16 years and older Setting: everyday self care Intervention: interdental brushing plus toothbrushing Comparison: toothbrushing only | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Toothbrushing only | Interdental brush plus toothbrushing | |||||

|

Gingivitis measured by gingival index SD units: investigators measure gingivitis using different scales Lower score means less severe gingivitis Follow‐up: 1 month |

The gingivitis score in interdental brush group was on average 0.53 SDs lower (0.23 to 0.83 lower) than the control group | ‐ | 62 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | ||

|

Gingivitis measured by proportion of bleeding sites Follow‐up: 1 month |

The mean score in the control group was 0.19 | The mean score in the interdental brush group was 0.05 less (0.13 less to 0.03 more) | ‐ | 31 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ very low2 | |

| Periodontitis | One study measured probing pocket depth but no data were reported. | |||||

| Interproximal caries | No included study assessed caries as an outcome | |||||

|

Plaque SD units: investigators measure plaque using different scales Lower score means less plaque Follow‐up: 1 month |

The plaque score in the interdental brush group was on average 1.07 SDs lower (0.63 to 1.51 lower) than the control group | ‐ | 93 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 | ||

| Harms and adverse outcomes | Neither study reported any information about adverse events. | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; IDB: interdental brushing; SD: standard deviation; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgraded three levels due to being based on only one small trial at unclear risk of bias

2 Downgraded three levels due to being based on only one small trial at unclear risk of bias

3 Downgraded two levels due to being based on only two small trials at unclear risk of bias

Summary of findings 3. Wooden cleaning stick plus toothbrushing compared to toothbrushing alone for periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults.

| Wooden interdental cleaning stick compared to flossing for periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults | ||||||

| Population: adults, 16 years and older Setting: everyday self care Intervention: wooden interdental cleaning stick plus toothbrushing Comparison: toothbrushing only | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Toothbrushing alone | Wooden cleaning stick plus toothbrushing | |||||

| Gingivitis measured by gingival index | Not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

|

Gingivitis measured by proportion of bleeding sites Follow‐up: 3 months |

The mean gingivitis score in the control group was 0.90 | The mean gingivitis score in the intervention group was 0.25 lower (from 0.13 to 0.37 lower) | ‐ | 24 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | 3‐month data only |

| Periodontitis | No included study assessed periodontitis as an outcome | |||||

| Interproximal caries | No included study assessed caries as an outcome | |||||

|

Plaque

(proportion of sites with plaque) Follow‐up: 3 months |

The mean plaque in the control group was 0.22 | The mean plaque score in the intervention group was 0.03 lower (0.13 lower to 0.07 higher) | ‐ | 24 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2 | 3‐month data only |

| Harms and adverse outcomes | Not reported | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; IDB: interdental brushing; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgraded three levels due to there being only one small trial at unclear risk of bias

2 Downgraded three levels due to there being only one small trial, at unclear risk of bias, and lack of precision in the estimate

Summary of findings 4. Rubber/elastomeric cleaning stick plus toothbrushing compared to toothbrushing alone for periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults.

| Interdental cleaning stick compared to flossing for periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults | ||||||

| Population: adults, 16 years and older Setting: everyday self care Intervention: interdental cleaning stick plus toothbrushing Comparison: toothbrushing only | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Toothbrush alone | Cleaning stick plus toothbrushing | |||||

|

Gingivitis measured by gingival index Lower score means less severe gingivitis Follow‐up: 1 month |

The mean score in the control group was 0.22 | The mean score in the intervention group was on average 0.01 lower (0.19 lower to 0.21 higher) than the control group.1 | ‐ | 12 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

|

Gingivitis measured by proportion of bleeding sites Follow‐up: 1 month |

The mean score in the control group was 0.19 | The mean score in the intervention group was 0.07 lower (0.15 lower to 0.01 higher) | ‐ | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2 | |

| Periodontitis | One study measured probing pocket depth but no data were reported. | |||||

| Interproximal caries | No included study assessed caries as an outcome. | |||||

|

Plaque (proportion of sites with plaque) Follow‐up: 1 month |

The mean plaque in the control group was 0.42 | The mean plaque score in the intervention group was 0.22 lower (0.03 to 0.41 lower) | ‐ | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2 | |

| Harms and adverse outcomes | Not reported | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; IDB: interdental brushing; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgraded three levels due to being based on single small study at high risk of bias, and lack of precision in the estimate 2 Downgraded three levels due to being based on single small study at unclear risk of bias

Summary of findings 5. Oral irrigation plus toothbrushing compared to toothbrushing alone for periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults.

| Oral irrigation plus toothbrushing compared to toothbrushing alone for periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults | ||||||

| Population: adults, 16 years and older Settings: everyday self care Intervention: oral irrigation plus toothbrushing Comparison: toothbrushing only | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Toothbrushing alone | Oral irrigation plus toothbrushing | |||||

|

Gingivitis measured by gingival index SD units: investigators measure gingivitis using different scales Lower score means less severe gingivitis Follow‐up: 1 month |

The gingivitis score in oral irrigation group was on average 0.48 SDs lower (0.06 lower to 0.89 lower) than the control group. | ‐ | 380 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | No significant evidence of a difference at 3 months (SMD ‐0.13, ‐0.44 to 0.17; 2 trials, 163 participants) or 6 months (MD ‐0.33, ‐0.74 to 0.08; 1 trial, 109 participants) | |

|

Gingivitis measured by proportion of bleeding sites Follow‐up: 1 month |

The mean score in the control group was 0.30 | The mean score in the intervention group was the same (0.07 lower to 0.06 higher) | ‐ | 126 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 | Nor any evidence of a difference at 3 months (MD ‐0.04, ‐0.13 to 0.05, 1 study, 54 participants) |

| Periodontitis | Measured in one study but useable data not provided | |||||

| Interproximal caries | No included study assessed caries as an outcome | |||||

|

Plaque SD units: investigators measure plaque using different scales. Lower score means less plaque. Follow‐up: 1 month |

The plaque score in the oral irrigation group was on average 0.16 SDs lower (0.41 lower to 0.10 higher)1 than the control group | ‐ | 235 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 | Nor did the evidence suggest benefit from the oral irrigator at 3 months (SMD 0.06, ‐0.25 to 0.37; 2 studies, 163 participants) or 6 months (MD 0.22, ‐0.59 to 0.15; 1 study, 109 participants) | |

| Harms and adverse outcomes | Three studies reported that there were no adverse events, one reported one incidence of aphthous ulcer in irrigator group, one reported oral lacerations but found no difference between the interventions, and one did not measure adverse events. | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; IDB: interdental brushing; SMD: standardised mean difference; SD: standard deviation | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgraded three levels as studies at unclear risk of bias, with substantial heterogeneity and imprecise estimate 2 Downgraded two levels as studies at unclear risk of bias, with moderate heterogeneity 3 Downgraded two levels as studies at unclear risk of bias, imprecise estimate

Summary of findings 6. Interdental brushing compared to flossing for periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults.

| Interdental brushing compared to flossing for periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults | ||||||

| Population: adults, 16 years and older Setting: everyday self care Intervention: interdental brushing plus toothbrushing Comparison: flossing plus toothbrushing | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Flossing | Interdental brush (IDB) | |||||

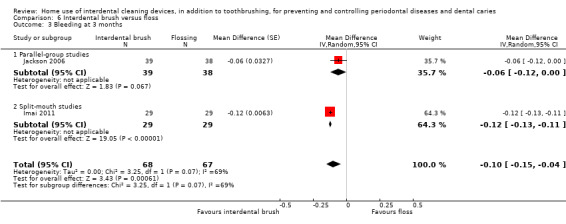

|

Gingivitis measured by gingival index SD units: investigators measure gingivitis using different scales Lower score means less severe gingivitis Follow‐up: 4 to 6 weeks |

The gingivitis score in the IDB group was on average 0.40 SDs lower (0.11 to 0.70 lower)1than the flossing group | ‐ | 183 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | Not measured at 3 months | |

|

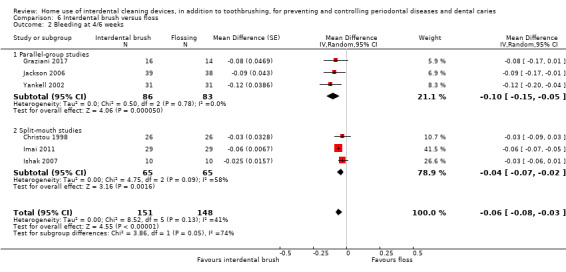

Gingivitis measured by proportion of bleeding sites Follow‐up: 4 to 6 weeks |

The mean score in the flossing group was 0.20 | The mean score in the IDB group was 0.06 lower (0.08 to 0.03 lower) | ‐ | 234 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 | Results at 3 months also indicated a small benefit for interdental brushes: MD ‐0.10 (‐0.15 to ‐0.04), 2 studies, 106 participants. |

|

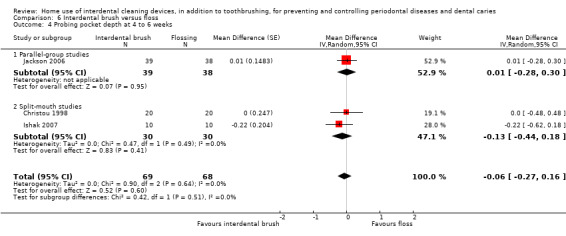

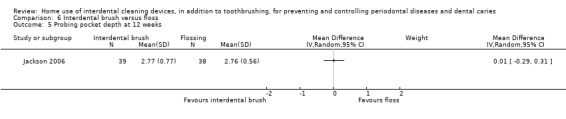

Periodontitis Probing pocket depth in mm Follow‐up: 4 to 6 weeks |

The mean PPD score for the flossing group was 5.01 mm | The mean PPD score in the IDB group was0.06 lower (0.27 lower to 0.16 higher) | ‐ | 107 (3 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 | Results were consistent at 3 months: MD 0.01 mm (‐0.29 to 0.31), 1 parallel‐group study, 77 participants. |

| Interproximal caries | No included study assessed caries as an outcome | |||||

|

Plaque SD units: investigators measure plaque using different scales Lower score means less plaque Follow‐up: mean 1 month (4 to 6 weeks) |

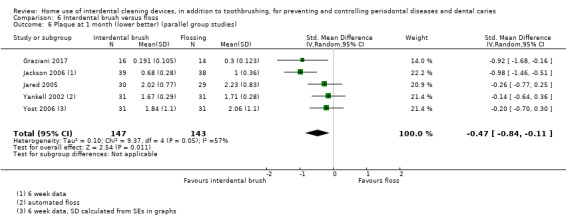

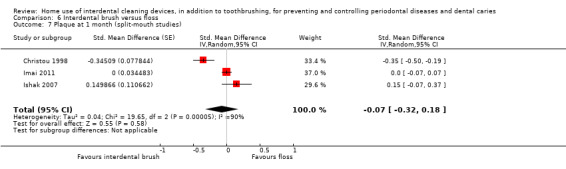

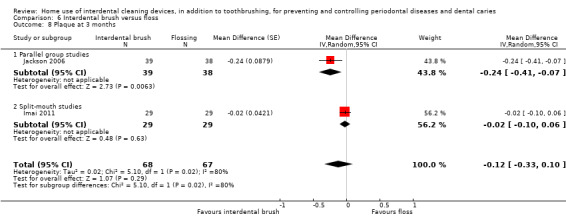

The plaque in the IDB group was on average 0.47 SDs lower (0.84 to 0.11 lower) than the flossing group | ‐ | 290 (5 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4 | This benefit for IDB compared to flossing for parallel‐group studies is not supported by the meta‐analysis of the split‐mouth studies at one month (SMD ‐0.07 (‐0.32 to 0.18), 3 studies, 66 participants). Nor by the 3‐month data (MD ‐0.12, 95% ‐0.33 to 0.10; two trials (one parallel and one split‐mouth), 106 participants). | |

| Harms and adverse outcomes | Five studies reported there were no adverse events. Two studies reported on problems with the use of interdental brushes or floss, which sometimes caused soreness. | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; IDB: interdental brushing; SMD: standardised mean difference; SD: standard deviation | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgraded two levels due to studies at unclear risk of bias, imprecise estimate (although consistent)

2 Downgraded two levels due to studies at unclear risk of bias, moderate heterogeneity

3 Downgraded two levels due to studies at unclear risk of bias, imprecise estimate

4 Downgraded three levels due to unclear risk of bias, imprecise estimates and moderate heterogeneity

Summary of findings 7. Wooden cleaning stick compared to flossing for periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults.

| Wooden cleaning stick compared to flossing for periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults | ||||||

| Population: adults, 16 years and older Setting: everyday self care Intervention: interdental cleaning stick plus toothbrushing Comparison: flossing plus toothbrushing | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Flossing plus toothbrushing | Wooden cleaning stick plus toothbrushing | |||||

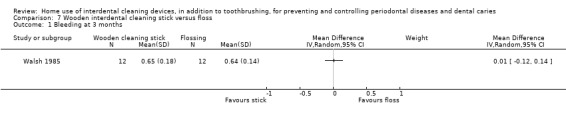

| Gingivitis measured by gingival index | Not measured | |||||

|

Gingivitis measured by proportion of bleeding sites Follow‐up: 3 months |

The mean gingivitis score in the control group was 0.64 | The mean gingivitis score in the intervention group was 0.01 higher (from 0.12 lower to 0.14 higher) | ‐ | 24 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | Only 3‐month data useable |

| Periodontitis | No included study assessed periodontitis | |||||

| Interproximal caries | No included study assessed caries as an outcome | |||||

|

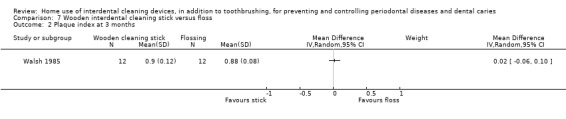

Plaque

(proportion of sites with plaque) Follow‐up: 3 months |

The mean plaque in the control group was 0.88 | The mean plaque score in the intervention group was 0.02 higher (0.06 lower to 0.10 higher) | ‐ | 24 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | Only 3‐month data useable |

| Harms and adverse outcomes | Not reported | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; IDB: interdental brushing; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgraded three levels due to there being only one small trial, at unclear risk of bias, and lack of precision of estimate

Summary of findings 8. Rubber/elastomeric cleaning stick compared to flossing for periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults.

| Interdental cleaning stick compared to interdental brushing for periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults | ||||||

| Population: adults, 16 years and older Setting: everyday self care Intervention: cleaning stick plus toothbrushing Comparison: interdental brushing plus toothbrushing | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Floss | Cleaning stick | |||||

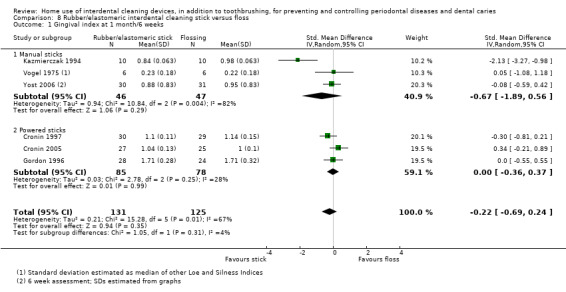

|

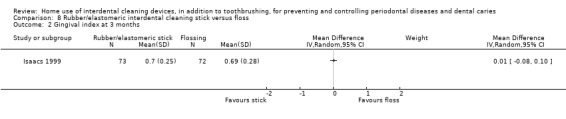

Gingivitis measured by gingival index SD units: investigators measure gingivitis using different scales Lower score means less severe gingivitis. Follow‐up: 4 to 6 weeks |

The gingivitis score in the cleaning stick group was on average 0.22 SDs lower (0.69 lower to 0.24 higher) than the floss group | ‐ | 256 (6 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | Nor was there was evidence that one intervention performed better than the other with regards to gingivitis control at 3 months (MD 0.01, 95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.10, 1 study, 145 participants). | |

|

Gingivitis measured by proportion of bleeding sites Follow‐up: 4 to 6 weeks |

The mean score in the floss group was 0.22 | The mean score in the cleaning stick group was 0.03 lower (0.08 lower to 0.03 higher) | ‐ | 212 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 | Nor was there was evidence that one intervention performed better than the other with regards to bleeding sites at 3 months (MD 0.01, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.05, 1 study, 145 participants) |

| Periodontitis | One study measured periodontitis but the data were not usable | |||||

| Interproximal caries | No included study assessed caries as an outcome | |||||

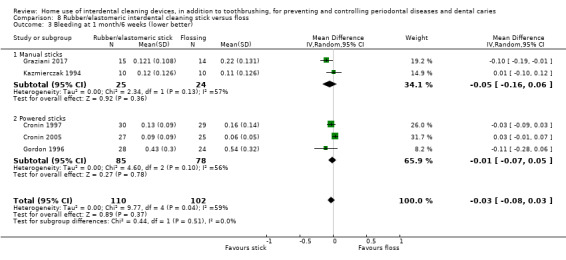

|

Plaque SD units: investigators measure plaque using different scales Lower score means less plaque Follow‐up: 4 to 6 weeks |

The plaque score in the cleaning stick group was on average 0.08 SDs lower (0.46 lower to 0.29 higher) than the floss group | ‐ | 273 (6 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3 | ||

| Harms and adverse outcomes | Five studies assessed adverse events. One did not report findings, but the others reported either no adverse events or minor adverse events that did not significantly differ between interventions. | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; IDB: interdental brushing; SMD: standardised mean difference; SD: standard deviation | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgraded three levels due to one study being at high risk of bias (others unclear), moderate heterogeneity and serious imprecision

2 Downgraded two levels due to studies at unclear risk of bias and moderate heterogeneity

3 Downgraded three levels due to studies at unclear risk of bias, moderate heterogeneity and serious imprecision

Summary of findings 9. Oral irrigation compared to flossing for periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults.

| Oral irrigation compared to flossing for periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults | ||||||

| Population: adults, 16 years and older Setting: everyday self care Intervention: oral irrigation plus toothbrushing Comparison: flossing plus toothbrushing | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Flossing | Oral irrigation | |||||

|

Gingivitis measured by gingival index SD units: investigators measure gingivitis using different scales Lower score means less severe gingivitis Follow‐up: 1 month |

The mean score in the floss group was 1.14 | The mean score in the irrigator group was 0.06 lower (0.12 lower to 0.00) | ‐ | 63 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

|

Gingivitis measured by proportion of bleeding sites Follow‐up: 1 month |

The mean score in the floss group was 0.56 |

The mean score in the irrigator group was 0.12 lower (0.19 lower to 0.05 lower) | ‐ | 133 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| Periodontitis | No included study assessed periodontitis | |||||

| Interproximal caries | No included study assessed caries as an outcome | |||||

|

Plaque SD units: investigators measure plaque using different scales Lower score means less plaque Follow‐up: 1 month |

The plaque in the oral irrigation group was on average 0.31 SDs higher (0.08 lower to 0.70 higher) than the flossing group | ‐ | 133 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2 | ||

| Harms and adverse outcomes | Both studies reported there were no adverse events in either study group. | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; SMD: standardised mean difference; SD: standard deviation | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgraded three levels due to single small study at unclear risk of bias

2 Downgraded three levels due to single small study at unclear risk of bias with serious imprecision

Summary of findings 10. Rubber/elastomeric interdental cleaning stick compared to interdental brush for periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults.

| Interdental cleaning stick compared to interdental brushing for periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults | ||||||

| Population: adults, 16 years and older Setting: everyday self care Intervention: cleaning stick plus toothbrushing Comparison: interdental brushing plus toothbrushing | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| IDB | Stick | |||||

|

Gingivitis measured by gingival index Lower score means less severe gingivitis Follow‐up: 4 to 6 weeks |

The mean score in the interdental brush group was 0.78 | The mean score in the cleaning stick group was 0.10 (0.32 lower to 0.52 higher) | ‐ | 61 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

|

Gingivitis measured by proportion of bleeding sites Follow‐up: 4 to 6 weeks |

The mean score in the interdental brush group was 0.14 | The mean score in the cleaning stick group was 0.02 lower (0.10 lower to 0.06 higher) | ‐ | 31 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2 | |

| Periodontitis | Two studies measured periodontitis but data not presented or usable | |||||

| Interproximal caries | No included study assessed caries as an outcome | |||||

|

Plaque SD units: investigators measure plaque using different scales Lower score means less plaque Follow‐up: 4 to 6 weeks |

The plaque score in the cleaning stick group was on average 0.08 SDs higher (0.33 lower to 0.49 higher) than the IDB group | ‐ | 92 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3 | ||

| Harms and adverse outcomes | Not reported | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; IDB: interdental brushing; SMD: standardised mean difference; SD: standard deviation | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgraded three levels due to single study at unclear risk of bias and serious imprecision

2 Downgraded three levels due to single study at unclear risk of bias and imprecision

3 Downgraded three levels due to 2 small studies at unclear risk of bias and serious imprecision

Background

Description of the condition

Periodontal diseases

Periodontal diseases are multifactorial oral health conditions (Llorente 2006; Timmerman 2006), consisting of a diverse family of pathological conditions affecting the periodontium (a collective term that comprises gingival tissue, periodontal ligament, cementum and alveolar bone). Periodontal diseases include two main conditions: gingivitis and periodontitis. Gingivitis is the presence of gingival inflammation without loss of connective tissue attachment and appears as red, puffy, shiny gums that bleed easily (Mariotti 1999). Periodontitis is inflammation and destruction of the supportive tissues of teeth and is, by its behaviour, characterised as aggressive or chronic (Armitage 1999). Periodontitis can influence quality of life through psychosocial impacts as a result of negative effects on comfort, function, appearance, and socialisation (Durham 2013; Needleman 2004), and can lead to tooth loss (Broadbent 2011).

Some form of periodontal disease affects the majority of the population, and is found in high‐, middle‐ and low‐income countries (Adult Dental Health Survey 2009; Eke 2012). A 2009 survey in the UK found only 17% of adults had healthy gums; 66% had visible plaque; and of those with plaque, 65% had bleeding gums compared with 33% with no plaque (Adult Dental Health Survey 2009). Whilst more severe forms of periodontal disease, with alveolar bone loss, are much less common, gingivitis is prevalent at all ages and is the most common form of periodontal disease (Mariotti 1999). The exact prevalence of periodontitis is difficult to establish across studies because of non‐standardised criteria, different study population characteristics, different clinical measurements, and the use of partial versus full mouth examinations (Cobb 2009; Savage 2009). Of particular concern are the differing definitions and clinical measurements used (Cobb 2009; Savage 2009). A global workshop organised by the American Academy of Periodontology and the European Federation of Periodonotology took place in 2017 to produce an updated classification scheme for periodontal and peri‐implant diseases (Caton 2018; Chapelle 2018; Papapanou 2018). This has provided "a staging and grading system for periodontitis that is based primarily upon attachment and bone loss and classifies the disease into four stages based on severity (I, II, III or IV) and three grades based on disease susceptibility (A, B or C)" (Dietrich 2019).

The primary aetiological factor in the development of periodontal diseases (and dental caries) is dental plaque (Dalwai 2006; Kuramitsu 2007; Marsh 2006; Periasamy 2009; Selwitz 2007). Dental plaque is a highly organised and specialised biofilm comprising of an intercellular matrix consisting of various micro‐organisms and their by‐products. The bacteria found within dental plaque mutually support each other, using chemical messengers, in a complex and highly evolved community, that protects them from an individual's immune system and chemical agents such as antimicrobial mouth rinses. Bacteria in biofilm are 1000 to 1500 times more resistant to antibiotics than in their free‐floating state, reducing the effectiveness of chemical agents as a solo treatment option. Therefore, disruption of the oral biofilm via mechanical methods remains one of the best treatment options (Chandki 2011). Calcified plaque (calculus) is not involved in the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases but it provides an ideal surface to collect further dental plaque and acts as a 'retention web' for bacteria, protecting plaque from appropriate preventive and therapeutic periodontal measures (Ismail 1994; Lindhe 2003).

Since periodontal diseases are inflammatory, bacterially‐mediated diseases that trigger the host's immune system, it is postulated that the individual's oral health status may influence their systemic health. Susceptibility to periodontal diseases is variable and depends upon the interaction of various risk factors, for example genetic makeup, smoking, stress, immunocompromising diseases, immunosuppressive drugs, and certain systemic diseases (Van Dyke 2005). Studies have shown some possible associations between periodontal diseases and coronary heart disease (Machuca 2012), hyperlipidaemia (Fentoğlu 2012), preterm births (Huck 2011), and lack of glycaemic control in people with diabetes mellitus (Columbo 2012; Simpson 2015). Socioeconomic factors, for instance educational and income levels, have been found to be strongly associated with the prevalence and severity of periodontal diseases (Borrell 2012).

Dental caries

Dental caries is a multifactorial, bacterially‐mediated, chronic disease (Addy 1986; Richardson 1977; Rickard 2004). It is the most common disease in the world (Frencken 2017; WHO 1990), affecting most school‐aged children and the vast majority of adults (Petersen 2003). Although the prevalence and severity of dental caries in most industrialised countries has substantially decreased in the past two decades (Marthaler 1996), this preventable disease continues to be a common public health problem in some parts of these countries (RCSEng 2018), and in other parts of the world (Burt 1998). In 2017, dental caries affected the permanent teeth of 2.3 billion people globally (GHDx 2017).

Deep pits and fissures, as well as interdental spaces, represent areas of increased risk for the collection and accumulation of dental plaque and are therefore regarded as susceptible tooth surfaces for the occurrence of carious lesions. The presence and growth of dental plaque is further encouraged by compromised host response factors, for example reduced salivary flow (hyposalivation) (Murray 1989). Fermentation of sugars by cariogenic bacteria within the plaque results in localised demineralisation of the tooth surface, which may ultimately result in cavity formation (Marsh 2006; Selwitz 2007).

People with carious teeth may experience pain and discomfort (Milsom 2002; Shepherd 1999); and, if left untreated, may lose their teeth. In the United Kingdom, tooth decay accounts for almost half of all dental extractions performed (Chadwick 1999).

Description of the intervention

Although the incidence of periodontal diseases and dental caries differs, based on regional, social, and genetic factors, the prevention of both diseases has a significant healthcare and economic benefit for society as a whole and for individuals. Prevention of dental caries and periodontal diseases is generally regarded as a priority for oral healthcare professionals because it is more cost‐effective than treating it (Brown 2002; Burt 1998). Daily mechanical disruption and removal of dental plaque is considered important for oral health maintenance (Rosing 2006; Zaborskis 2010). Additional professional plaque removal can sometimes be required, though the routine provision of this for people who regularly attend the dentist has recently been questioned (Lamont 2018). People routinely use toothbrushes at home to remove supragingival dental plaque, but toothbrushes are unable to penetrate the interdental area where periodontal diseases first develop and are prevalent (Asadoorian 2006; Berchier 2008; Berglund 1990; Casey 1988). Besides toothbrushing, which is the most common method for removing dental plaque (Addy 1986; Mak 2011; Richardson 1977), different interdental aids to plaque removal, for example, dental floss or interdental brushes, are widely available and often recommended for use in addition to toothbrushing (Bosma 2011; Särner 2010). Whilst floss can be used in all interdental spaces, the interdental brush and other interdental cleaning aids require sufficient interdental space to be used by patients. The choice of interdental cleaning aid will depend on the size of the space and the ability of the patient to use it.

Toothbrushes

Regular daily toothbrushing is a key strategy for preventing and controlling periodontal diseases and dental caries, because it disrupts supragingival dental plaque and reduces the number of periodontal pathogens in supragingival plaque (Caton 2018; Chandki 2011; Ismail 1994; Needleman 2004; Rosing 2006; Zaborskis 2010). In order to achieve highest level of dental plaque removal, various types of toothbrushes have been designed, and different toothbrushing techniques have been developed over time (Lindhe 2003). In an update of a Cochrane systematic review published in 2014 that included 56 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), moderate‐certainty evidence suggested that powered toothbrushes are more effective in reducing plaque and gingivitis than manual toothbrushes in the short and long term, with very few adverse events reported overall and no apparent differences between the two toothbrushing regimens (Yacob 2014). However, the observed likely benefit of powered toothbrushing is of unclear clinical significance, as it reduced dental plaque by 11% after one to three months of use, and by 21% after three months of use. As for clinical signs of gingivitis, there was a reduction of 6% at one month and 11% after three months of use.

Although toothbrushing is effective in removing dental plaque from buccal and lingual tooth surfaces, because of their shape, toothbrushes are not able to penetrate interdental areas and adequately clean interproximal teeth surfaces (Christou 1998). Likewise, toothbrushes are able to reach only 0.9 mm under the gingival margin, and therefore cannot reduce the rate of subgingival areas affected by periodontal pathogens (Waerhaug 1981; Xiemenez‐Fyvie 2000). Interdental plaque accumulates more quickly, is more prevalent, and more acidogenic than plaque on other tooth surfaces (Cumming 1973; Igarashi 1989; Lindhe 2003; Lovdal 1961; Warren 1996). It is important that plaque is controlled in the interdental areas because these are the sites where periodontal diseases occur more frequently, with greater severity (Asadoorian 2006; Berchier 2008; Berglund 1990; Christou 1998; Lindhe 2003; Loe 1965). Caries also occurs more often on the interproximal tooth surfaces (Berglund 1990; Casey 1988; Lindhe 2003).

Dental floss

The concept of interdental cleaning with a filamentous material was first introduced by Levi Spear Parmly, as a measure for preventing dental disease together with a dentifrice and toothbrush (Parmly 1819). Unwaxed silk floss was first produced in 1882, by Codman & Shurtleff, but it was Johnson & Johnson who made silk floss widely available from 1887, as a by‐product of sterile silk leftover from the manufacture of sterile sutures (Johnson & Johnson).

Since dental floss is able to remove some interproximal plaque (Asadoorian 2006; Waerhaug 1981), it is thought that frequent regular dental flossing will reduce the risk of periodontal diseases and interproximal caries (Hujoel 2006). Daily dental flossing in combination with toothbrushing for the prevention of periodontal diseases and caries is frequently recommended for both children and adults (Bagramian 2009; Brothwell 1998). However, patient compliance with daily dental flossing is low (Schuz 2009). People attribute their lack of dental flossing compliance to lack of motivation and difficulties using floss (Asadoorian 2006). A study of a cohort of young people at ages 15, 18, and 26 found that at age 26, only 51% of both females and males believed that using dental floss was important, with females rating flossing more important than males (Broadbent 2006).

Certain organisations, for example the American Dental Association, recommend that children’s teeth are flossed as soon as they have two teeth that touch. However, studies that measure compliance show that few children have their teeth flossed or use floss: a study in West Virginia found that only 21% of children had their teeth flossed (Wiener 2009). When measures are taken to increase compliance, for example using behavioural change techniques, then the proportion of adolescent flossing increases (Gholami 2015).

Interdental brushes

Interdental brushes are small cylindrical or cone‐shaped bristles on a thin wire that may be inserted between the teeth. They have soft nylon filaments aligned at right angles to a central stiffened rod, often twisted stainless steel wire, very similar to a bottle brush. Interdental brushes used for cleaning around implants have coated wire to avoid scratching the implants or causing galvanic shock. They are available in a range of different widths to match the interdental space and their shape can be conical or cylindrical. Most are round in section, although interdental brushes with a more triangular cross‐section can also be found on the market. Originally, interdental brushes were recommended by dental professionals to patients with large embrasure spaces between the teeth (Slot 2008; Waerhaug 1976), caused by the loss of interdental papilla mainly due to periodontal destruction. Patients who had interdental papillae that filled the embrasure space were usually recommended to use dental floss as an interdental cleansing tool. However, with the greater range of interdental brush sizes and cross‐sectional diameters now available, they are considered a potentially suitable alternative to dental floss for patients who have interdental papillae that fill the interdental space (Imai 2011). Daily dental flossing adherence is low because it requires a certain degree of dexterity and motivation (Asadoorian 2006), whereas interdental brushes have been shown as being easier to use and are therefore preferred by patients (Christou 1998; Imai 2010). Furthermore, when compared to dental floss, they are thought to be more effective in plaque removal because the bristles fill the embrasure and are able to deplaque the invaginated areas on the tooth and root surfaces (Bergenholtz 1984; Christou 1998; Imai 2011; Jackson 2006; Kiger 1991; Waerhaug 1976). However, there are conflicting study results regarding the efficacy of interdental brushes in the reduction of clinical parameters of gingival inflammation (Jackson 2006; Noorlin 2007); and whether they are only suitable for patients with moderate to severe attachment loss and open embrasures, or whether they are a suitable aid for healthy patients to prevent gingivitis who have sufficient interdental space to accommodate them (Gjermo 1970; Imai 2011).

Tooth cleaning sticks

Sticks and twigs, composed of bone, ivory, metal, plastic, quills, wood, and other substances, have been used for cleaning tooth surfaces and interdentally since prehistoric times (Christen 2003). The continuing use of hard materials for cleaning interdentally has been questioned (Mandel 1990); however, they continue to be used in different parts of the world. The meswak (or miswak) is one of the most widely used tooth cleaning sticks (Saha 2012); however, it is important to differentiate its use between cleaning tooth surfaces and interdentally (Furuta 2011). Toothpicks continue to be used, particularly in the United States and Scandinavia, predominantly in older age groups (Sarner 2010), whereas dental floss and interdental brushes are more likely to be used by younger people. Toothpicks are commonly used in East Asia such as in China, Korea, and Japan, though the main purpose is to remove food debris in the interdental areas. Interdental rubber tip stimulators, usually consisting of a carrying handle and disposable rubber tip stimulator, are readily available and are designed to stimulate gingival blood flow and remove interdental plaque.

Oral irrigators

Oral irrigation with water under pressure has been available for just over fifty years (Lyle 2012), and the benefits are described as the removal of biofilm from tooth surfaces and bacteria from periodontal pockets. Oral irrigators were first designed to be used supragingivally, using water pressure to displace and remove plaque, relying on pressure to irrigate subgingival regions (Goyal 2012). Since then, various tips have been designed that may be used subgingivally and several manufacturers provide products to do this.

How the intervention might work

Dental plaque‐induced gingivitis and incipient, non‐cavitated carious lesions are reversible (Mariotti 1999; Silverstone 1983). The progression in either disease may be attributed to a change in the environmental equilibrium that favours disease conditions. For example, gingivitis has been shown to be a risk factor in the clinical course of chronic periodontitis (Schatzle 2009); and it is important to treat gingivitis when inflammation is only in the gingival tissues and has not affected other parts of the periodontal system (Mariotti 1999). Early carious lesions can be arrested in the enamel and may or may not progress to the dentine depending on the dynamic equilibrium between demineralisation and remineralisation (Marinho 2003; Marinho 2013; Marinho 2015).

Periodontal diseases

Gingival diseases are classified as one of the periodontal diseases (Armitage 1999; Caton 2018), and are categorised as either dental plaque‐induced diseases or non‐plaque‐induced gingival lesions. Gingival inflammation, gingivitis, induced by dental plaque is an inflammatory response of the gingival tissues caused by bacteria in dental plaque (Page 1986), and characterised by swelling, redness and bleeding on probing. If dental plaque is left in place for more than two weeks, then gingivitis will occur (Loe 1965). The severity of gingivitis can be modified by factors other than plaque (Trombelli 2013).

Periodontal diseases are complex interactions of bacteria and the immune system (Page 2007; Sanz 2011); and dental plaque is the primary aetiological factor (Marsh 2006). Dental plaque may be either supragingival or subgingival and the plaque biofilm comprises different bacterial colonies at the supragingival or subgingival levels. By disrupting the plaque, the main cause of periodontal diseases can be removed. Although there is a lack of RCT evidence for the best approaches to ensuring periodontal health is maintained after treatment for periodontitis (Manresa 2015), a key aspect of supportive periodontal therapy is training in self‐administered mechanical plaque removal techiques, and this is also widely regarded as a crucial part of preventive strategies (Greenwell 2001; Lindhe 2003).

Dental caries

Dental plaque contains many bacterial species that are acidogenic. In 1890, Miller published 'The microorganisms of the human mouth' which postulated that oral bacteria found in plaque were acidogenic, but, as no specific bacteria were implicated, it became known as the "non‐specific plaque hypothesis" (Ring 2002). Later, Loesche 1976 postulated a "specific plaque theory", implicating Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus acidophilus as the primary bacteria involved in caries generation. Since then, the importance of the plaque biofilm has been recognised and an “ecological plaque hypothesis” proposed (Marsh 1994).

Acidogenic plaque bacteria utilise dietary sugars to demineralise dental tissues, which may progress into carious tooth lesions. The most susceptible regions of teeth to caries are the occlusal and interdental surfaces (Demirci 2010). Interdental plaque is more prevalent (Lindhe 2003), forms more readily (Igarashi 1989) and is more acidogenic than plaque on other tooth surfaces in the mouth. Therefore, interdental cleaning is often recommended as an adjunctive self care therapy, particularly when caries risk is increased (Sarner 2010; Wright 1977). Removal of dental plaque by mechanical interdental cleaning should reduce the frequency and degree of demineralisation interproximally and lead to decreased caries incidence.

Why it is important to do this review

Effective oral hygiene is a crucial factor in maintaining good oral health, which is, in turn, associated with overall health and health‐related quality of life (McGrath 2002; Sheiham 2005). Poor oral health may affect appearance in terms of stained or missing teeth; can contribute to bad breath (Morita 2001); and negatively influence self confidence, self esteem, and the ability to communicate (Exley 2009). Poor oral health is often accompanied by pain arising from carious lesions, which may lead to discomfort when eating, drinking, and speaking (Dahl 2011). Individuals with high levels of dental plaque, after accounting for sex, socioeconomic status, and dental care attendance frequency, are more likely to experience dental caries and periodontal diseases (Broadbent 2011).

The regular and effective removal of dental plaque by toothbrushing is important for the prevention and successful management of common oral diseases, in conjunction with use of fluoride toothpaste (Walsh 2019). Mechanical interdental cleaning, using either dental floss, interdental brushes, or tooth cleaning sticks, is widely recommended and advertised, but it is unclear whether there is a benefit in using interdental cleaning devices as an adjunct to toothbrushing and if a particular type of interdental cleaning device is superior to others. What the benefits may be for children and adolescents is unknown.

This review, which incorporates and expands previous reviews on flossing (Sambunjak 2011) and interdental brushing (Poklepovic Pericic 2013), was identified as a topic of clinical priority when Cochrane Oral Health undertook a comprehensive prioritisation exercise (Worthington 2015). A systematic review and meta‐analysis, combining the results of randomised controlled trials, will provide health care commissioners, practitioners, and consumers with evidence about the effectiveness of mechanical interdental cleaning at home for oral health.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of interdental cleaning devices used at home, in addition to toothbrushing, compared with toothbrushing alone, for preventing and controlling periodontal diseases, caries, and plaque. A secondary objective was to compare different interdental cleaning devices with each other.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including split‐mouth design, cross‐over trials and cluster‐randomised trials, that lasted four weeks or more. We included data from both periods of a cross‐over trial only if there was a washout period of at least two weeks before the cross‐over. Studies were included irrespective of publication status and language.

Types of participants

The review included studies of dentate participants irrespective of age, race, sex, socioeconomic status, geographical location, background exposure to fluoride, initial dental health status, setting, or time of intervention. We excluded studies if the majority of participants had any orthodontic appliances. Likewise, we excluded studies if participants were selected on the basis of special (general or oral) health conditions (for example, severely immunocompromised people), or if the majority of participants had severe periodontal disease.

Types of interventions

We included all trials that compared a combination of toothbrushing and any home‐use mechanical interdental cleaning device with toothbrushing alone, or with another mechanical interdental cleaning device.

We excluded intervention or control groups receiving any additional active agent(s) (i.e. caries‐preventive agents) as part of the study (e.g. chlorhexidine mouthwash, additional fluoride‐based procedures, oral hygiene procedures, xylitol chewing gum), in addition to interdental cleaning procedures or toothbrushing. However, we included studies using floss impregnated with active agents such as chlorhexidine or fluoride. We included studies that involved participants in both groups receiving additional measures as part of their routine oral care, such as oral hygiene advice, supervised brushing, fissure sealants, etc. We excluded studies that compared two variations of the same type of interdental cleaning device.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Outcomes did not form part of the inclusion criteria. We included all RCTs of home‐use devices in this review, even if they did not report these outcomes.

Gingivitis ‐ assessed by gingival indices and bleeding indices in separate analyses;

Periodontitis ‐ assessed by clinical attachment loss and pocket probing depth;

Interproximal caries ‐ assessed by (a) progression of caries into enamel or dentine, (b) change in decayed, missing and filled tooth surfaces (D(M)FS) index, (c) radiographic evidence. Studies had to contain explicit criteria for diagnosing dental caries. As caries increment could be reported differently in different trials, we planned to use a set of a priori rules to choose the primary outcome data for analysis from each study (Marinho 2013; see Table 11);

Plaque – assessed by plaque scores or indices;

Harms and adverse effects.

1. A priori rules for selecting data to extract for caries increment.

| As we were aware that caries increment could be reported differently in different trials, we developed a set of a priori rules to choose the primary outcome data (decayed, missing or filled surfaces (D(M)FS)) for analysis from each study, drawing on Marinho 2013: DFS data would be chosen over DMFS data, and these would be chosen over DS or FS; data for 'all surface types combined' would be chosen over data for 'specific types' only; data for 'all erupted and erupting teeth combined' would be chosen over data for 'erupted' only, and these over data for 'erupting' only; data from 'clinical and radiological examinations combined' would be chosen over data from 'clinical' only, and these over 'radiological' only; data for dentinal/cavitated caries lesions would be chosen over data for enamel/non‐cavitated lesions; net caries increment data would be chosen over crude (observed) increment data; and follow‐up nearest to three years (often the one at the end of the treatment period) would be chosen over all other lengths of follow‐up, unless otherwise stated. When no specification was provided with regard to the methods of examination adopted, diagnostic thresholds used, groups of teeth and types of tooth eruption recorded, and approaches for reversals adopted, the primary choices described above were assumed. |

For gingivitis, plaque and adverse effects, we considered outcomes at all time points measured by the included studies except those with a duration of less than one month. We planned to use only data with at least six months' follow‐up for the outcomes of clinical attachment loss, pocket probing depth, and interproximal caries.

Secondary outcomes

Halitosis;

Patient satisfaction;

Cost of intervention.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Oral Health’s Information Specialist conducted systematic searches in the following databases for randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials. There were no language, publication year, or publication status restrictions:

Cochrane Oral Health’s Trials Register (searched 16 January 2019) (see Appendix 1);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 12) in the Cochrane Library (searched 16 January 2019) (see Appendix 2);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 16 January 2019) (see Appendix 3);

Embase Ovid (1980 to 16 January 2019) (see Appendix 4);

CINAHL EBSCO (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1937 to 16 January 2019) (see Appendix 5).

Subject strategies were modelled on the search strategy designed for MEDLINE Ovid. Where appropriate, they were combined with subject strategy adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by Cochrane for identifying randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Chapter 6 (Lefebvre 2011).

We also initially searched Web of Science Conference Proceedings, but discontinued this search due to a poor yield of studies for inclusion (see Appendix 6 for details of the search strategy).

Searching other resources

The following trial registries were searched for ongoing studies:

US National Institutes of Health Trials Register (http://clinicaltrials.gov) (to 16 January 2019) (see Appendix 7);

The WHO Clinical Trials Registry Platform (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/default.aspx) (to 16 January 2019) (see Appendix 8).

We searched the reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews for further studies.

We did not perform a separate search for adverse effects of interventions used; we considered adverse effects described in included studies only.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently carried out the selection of studies and made decisions about eligibility; one of them a methodologist and the other a topic area specialist. The search was designed to be sensitive and include controlled clinical trials; these were filtered out early in the selection process if they were not randomised. If the relevance of a study report was unclear, we read the full text and resolved disagreements by discussion with other authors.

Data extraction and management

At least two review authors independently extracted data; at least one of them a methodologist and one a topic area specialist. We compared the extracted data and identified disagreements, which we then resolved by consensus.

We extracted and entered the following data into a customised collection form. We had previously designed a data extraction form for a similar review (Sambunjak 2011).

Study characteristics: design, including details if a study differed from standard parallel‐group design, e.g. split‐mouth or cross‐over; recruitment period, setting.

Participants: number randomised and evaluated (by group); inclusion and exclusion criteria; demographic characteristics of participants: age, sex, country of origin, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, comorbidity, condition‐related health status. We recorded demographic characteristics for the study as a whole and for each intervention group, when available.

Intervention and control groups: type of interdental cleaning procedure, including type of toothbrush (powered or manual) and type of toothpaste (with or without fluoride); frequency of interdental cleaning procedure; duration of the intervention period; whether the participants were trained/instructed how to brush interdentally, floss or toothbrush, or a combination of all three, and by whom; length of follow‐up; loss to follow‐up; assessment of adherence; level of fluoride in the water supply.

Outcomes: detailed description of the outcomes of interest (both beneficial and adverse), including the definition and timing of measurement; methods of assessment; other outcomes reported in the included studies that were not outcomes of this review (we did not extract results for these outcomes).

Data on funding sources if reported.

We intended to enter the data from cross‐over studies, split‐mouth studies, and for the prevented fraction, into RevMan (Review Manager (RevMan)) using the generic inverse variance outcome type.

We extracted both gingival indices and bleeding indices (assessed as bleeding either present or absent on a site) where both were reported. We extracted data from indices assessed on the interproximal sites if available; otherwise we used the indices on the sites reported.

In studies that used both bleeding on probing (BOP) and Eastman Interdental Bleeding Index (EIBI), we included EIBI in the meta‐analyses. The suitability of the EIBI is justified by its reproducibility and high inter‐examiner and intra‐examiner reliability (Blieden 1992).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias in each study using Cochrane's 'Risk of bias' tool as described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). The tool addresses seven domains: random sequence generation, allocation sequence concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other issues. For split‐mouth and cross‐over designs, our assessment of risk of bias included additional considerations such as suitability of the design, and risk of carry‐over or spill‐over effects.