Abstract

Objectives

Community-based support for people with earlier-stage dementia and their care partners, such as regularly meeting groups and activities, can play an important part in postdiagnostic care. Typically delivered piecemeal in the UK, by a variety of agencies with inconsistent funding, provision is fragmented and many such interventions struggle to continue after only a short start-up period. This realist review investigates what can promote or hinder such interventions in being able to sustain long term.

Methods

Key sources of evidence were gathered using formal searches of electronic databases and grey literature, together with informal search methods such as citation tracking. No restrictions were made on article type or study design; only data pertaining to regularly meeting, ongoing, community-based interventions were included. Data were extracted, assessed, organised and synthesised and a realist logic of analysis applied to trace context–mechanism–outcome configurations as part an overall programme theory. Consultation with stakeholders, involved with a variety of such interventions, informed this process throughout.

Results

Ability to continually get and keep members; staff and volunteers; the support of other services and organisations; and funding/income were found to be critical, with multiple mechanisms feeding into these suboutcomes, sensitive to context. These included an emphasis on socialising and person-centredness; lowering stigma and logistical barriers; providing support and recognition for personnel; networking, raising awareness and sharing with other organisations, while avoiding conflict; and skilled financial planning and management.

Conclusions

This review presents a theoretical model of what is involved in the long-term sustainability of community-based interventions. Alongside the need for longer-term funding and skilled financial management, key factors include the need for stigma-free, person-centred provision, sensitive to members’ diversity and social needs, as well as the need for a robust support network including the local community, health and care services. Challenges were especially acute for small scale and rural groups.

Keywords: health policy, organisation of health services, dementia, old age psychiatry, social medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This review brings together transferable learning from a wide range of intervention types on a topic that has received little formal, integrated research attention, to deepen our understanding on how such interventions could be implemented and supported to sustain more universally and consistently across the sector.

This review’s realist approach is well suited to accommodate and account for the complexity of such ‘real life’ intervention programmes, as implemented under different conditions in different settings, to extract transferable conclusions.

This review was designed to gather evidence regarding how interventions can be sustained, not on the efficacy/effectiveness of interventions of this type, hence conclusions regarding the latter are beyond its scope.

Literature was limited as this research question is not commonly the main focus of study in dementia care research.

Not all data were equal in depth and detail or the highest empirical rigour, rather they contributed together in a way that was useful to an overall programme theory that will benefit from further refinement and revision with empirical testing in subsequent research.

Introduction

Supporting people with dementia and their carers to live as well as possible in their communities, with timely psychosocial support, is a global public health goal,1 though remains a challenging aspiration in many countries. In the UK, with an ageing population2 and increasing pressure on already-stretched health services,3 policy has for some time pointed to the need to move towards a model of social care where more people are cared for and supported at home, in the community. Improving provision of early, postdiagnosis support, support for family carers and better integrated care (involving the voluntary and independent sectors)—all in a more dementia-friendly community environment—are contemporary UK Government priorities for dementia care.4

Support following a diagnosis of dementia is patchy,4 however, with families in some areas lacking any formal proactive support for those with less severe symptoms beyond occasional contact with primary care and third sector. There are significant gaps in social care for people affected by dementia across the UK.5–7 Multiple recent reports describe a climate where the state of social care provision—mainly delivered piecemeal by private and third-sector organisations—is ‘precarious and dysfunctional’ in many parts of the country6 and in some areas has ‘broken down’ creating ‘care deserts’.5 There is an associated reliance on informal carers (eg, family members) but there is a growing recognition that informal carers’ own health and well-being is often negatively impacted by their caring activities.6 The detrimental health impact of social isolation and loneliness is also increasingly being recognised,8 9 with survey data revealing nearly 60% of people living with dementia report loneliness, isolation and losing touch with people in their lives since diagnosis, around a quarter feeling they are not part of their community and that people avoid them.7 Family carers can also be subject to such loneliness and isolation.10 This situation has only been exacerbated by the recent impact of COVID-19,11 bringing the need for groups and activities that provide social connection and support for people and families affected by dementia into stark relief.

There have been various attempts to mitigate these challenges in communities across the country, in the form of groups and activities for people with dementia and family carers. These aim to serve a number of functions: peer support, companionship and help for people to reintegrate with their communities; delivery of professional support, psychosocial interventions and physical exercise; a point of contact, signposting and referral for other services; or raising awareness and acting as a dementia-friendly community hub. The benefits of such community-based initiatives are now being recognised.12–16 There is evidence that regular social activity, where people are able to leave their homes and gather together in a communal setting on a frequent and ongoing basis, can be helpful both for people living with dementia and the people who care for them.12 13 17–19 With care systems unprepared for the forecasted UK doubling of the number of people living with dementia (1.6 million) and tripling of social care costs by 2040,20 improving provision of evidence-based community initiatives for people with dementia, and their families, is imperative.12–16 21 22 However, even prior to the 2020 pandemic restrictions, such initiatives, groups and activities already faced a variety of challenges with long-term sustainability. These challenges and how to meet them are much talked about in the dementia care policy, rhetoric and practice arenas but have received very little research attention.

This realist review aims to deepen our understanding of what can help or hinder the long-term sustainability of regularly meeting, place-based community interventions, such as groups and activities, for people affected by dementia. It aims to use data gathered as the basis of evidence-informed recommendations for policy and practice.

Methods

This review was conducted from December 2018 to December 2020. A project protocol was registered with PROSPERO in March 201923 and the protocol was published in this journal in June 2019.24

The realist review is an interpretive, theory-driven approach to synthesising evidence from a range of sources, including qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods research.25 This approach is designed to accommodate and account for the complexity of ‘real-life’ intervention programmes, as implemented under different conditions in different settings, aiming to explain how and why context can influence outcomes.26 Hence it is well suited to extracting transferable lessons from reviewing the functioning and success (or otherwise) of a range of community-based interventions for people affected by dementia, as these are likely to involve a high level of complexity and be responsive to contextual factors which are likely to vary considerably from intervention to intervention. Data were gathered and synthesised, with a realist logic of analysis applied to identify causal chains involving different contexts, mechanisms and outcomes that can in turn affect an initiative’s long-term sustainability. We define context as the conditions that trigger or modify the behaviour of mechanisms;27 mechanisms are the usually-hidden processes that generate outcomes, defined as ‘underlying entities, processes or structures which operate in particular contexts to generate outcomes of interest.’28; outcomes can be ‘either intended or unintended and can be proximal, intermediate or final’27 and in this review refer to any identifiable result (of the interaction between contexts and mechanisms) that can directly have a bearing on an intervention’s ability to sustain long term.

Our review followed Pawson’s five iterative stages29 as outlined below.

Step 1: locating existing theories

This initial step was to identify and gather existing ideas around what can help or hinder the sustainability of a group or activity, from those who have first-hand experience of them. In line with realist review guidelines (RAMESES: Realist and Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses Evolving Standards),29 stakeholders were contacted by TA and TM and consulted for input at points throughout the project. These stakeholders were lay experts involved with community-based interventions in various capacities, whether commissioning, leading, running, supporting or attending. In the first instance, a workshop was held in March 2019 with a group of 13 invited stakeholders to gather their content expertise on barriers and facilitators to engagement and sustainability. Eight others were subsequently consulted by TM individually, in person, by telephone or by email. Input was also taken by TA and TM from members and facilitators of various local Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project30 groups at a national meeting in June 2019, and TM also visited three community groups in Herefordshire, Oxfordshire and Wolverhampton. In addition, an exploratory search of the literature was conducted by TM, using informal methods such as citation tracking and snow-balling31 along with informal scoping searches32 and the gathering of relevant publications and materials recommended by stakeholders. Together, this contributed towards the building of an initial theoretical model, or programme theory, with the guidance of GW, prior to our main search, both to inform our formal search strategy and to be tested and refined by the data subsequently found. This model began as two diagrams (one regarding engagement, one regarding sustainability), drawn up by TM and TA by batching issues raised at the March workshop, and possible links between them. These diagrams were then discussed, altered and added to iteratively over 4 months as new stakeholder input became available (these can be seen in online supplemental file 1). These diagrams were speculative so kept deliberately broad and fluid in focus, as a work in progress. Detailed analysis of possible context–mechanism–outcome configurations (CMOCs) was not considered appropriate at this stage, as: (1) Not enough data had been gathered; (2) This would be both labour intensive and too limiting for a model whose purpose was only as a steering guide to inform the review proper, yet to be undertaken.

bmjopen-2020-047789supp001.pdf (972.1KB, pdf)

Step 2: search for evidence

Formal search

Formal searching activity took place between May and September 2019. A search strategy was designed, piloted and conducted by the research team with the guidance from an information specialist (CK) (see online supplemental file 2). The following databases were searched: Academic Search Complete; AMED; CINAHL; EMBASE; MEDLINE; ProQuest; PsycINFO; PubMed; Scopus and Social Care Online. In keeping with RAMESES guidelines,29 no restrictions were made on the type of article or study design eligible for inclusion, other than being more recent than 1990. Documents such as editorials, opinion pieces, information guides, publicity materials, newspaper and magazine articles, evaluation reports, PhD theses and research poster and slide presentations were included along with peer-reviewed journal articles, if found to be holding relevant information. Search terms were kept uniform across all databases and searching was carried out by looking for the occurrence of these within the title, abstract and key words of documents (or nearest equivalent) in each database. Database-specific defined keywords were not used as the types of intervention were not only very diverse but often without a common agreed terminology, hence using too narrowly-specified terms would have resulted in an unmanageably voluminous list of possible key words, without necessarily locating better-targeted results, and could be limiting and misleading. In addition the nature of this review’s research question is atypical in that it does not have an efficacy/effectiveness focus in common with many of its sources of data, hence manual screening was key in determining relevance. A disadvantage of this was that we had to accept a higher ratio of irrelevant search hits which then had to be excluded through manual screening of title and abstract.

bmjopen-2020-047789supp002.pdf (65.3KB, pdf)

After removing duplicates, records were screened by title and abstract by TM using the eligibility criteria, ensuring interventions covered were those targeted towards people with dementia and their families living in the community, that brought people together physically and met on a frequent, regular and an ongoing basis (these criteria are outlined in full detail in online supplemental file 3). Interventions exclusively for those with severe dementia at advanced stages were excluded as these were not the focus of this review. Those with severe dementia have high needs and are less likely to be living independently in the community, hence by their nature community-based interventions where people meet outside of their home are likely to serve those who are towards the start of their dementia journey rather than those at an advanced stage, and are distinct from more acute care.

bmjopen-2020-047789supp003.pdf (123KB, pdf)

Full text of documents were then obtained of the remaining records, and again screened by close reading against the eligibility criteria by TM. A 10% random subsample of was reviewed independently at each of these stages by a second reviewer (TA) with disagreements recorded and resolved by discussion. Informal searching continued iteratively alongside the formal search and in response to articles found in it, congruent with the realist review process which allows searching to be revised as necessary as the review progresses.29 In certain cases, documents regarding on interventions that met only some, not all, of the inclusion criteria were included, if found to contain information on hypothesised mechanisms with reason to believe such mechanisms may function similarly or analogously in types of intervention that are closely related.33

Steps 3 and 4: article selection, data extraction and organisation

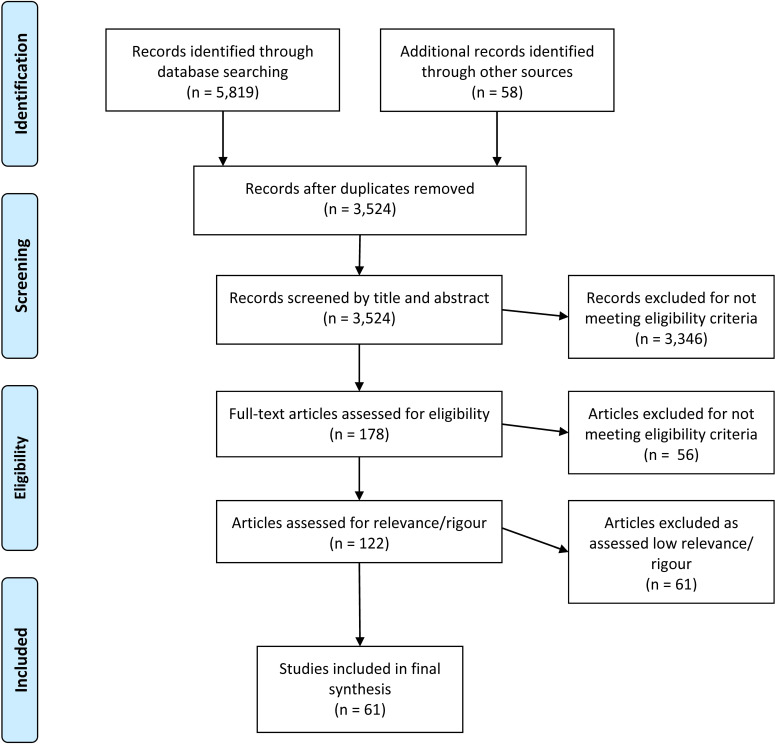

Figure 1 shows a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram outlining the full screening and selection process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Following screening and close-reading of full texts for eligibility, full texts of the remaining 122 articles were loaded into NVivo qualitative data analysis software to help locate and categorise (code) relevant sections of text containing data regarding contexts, mechanisms or outcomes pertinent to the long-term sustainability of the intervention they described. Coding was both inductive (codes created in response to data as found) and deductive (codes created in advance, informed by the initial programme theory) and carried out by TM (An overview of top-level ‘parent’ codes can also be seen in online supplemental file 1); deductive codes can be identified in that they mirror the headings of the initial model diagrams). The characteristics of the articles were also extracted separately into an EXCEL spreadsheet.

During this extraction and organisation process, more fine-grained assessments of relevance (to answering the research question) and rigour (the trustworthiness and credibility of the data and its source)25 34 were made by TM, with a random sample of 10% of articles again selected, assessed independently and discussed with TA. The data contained in an article was assessed on its own merits, not on the merits of the paper or study as a whole. This is because it was recognised that poorly designed or conducted research may still contain good quality ‘nuggets’ of information for a realist review,34 35 or a document meeting inclusion criteria may not contain any relevant data. Due to the variety and breadth of the type of article included in the review, a standardised relevance and rigour assessment tool that would be appropriate in all cases was impossible to design.25 Rather a set of general principles was agreed to guide a ‘traffic light’ assessment system of low, medium and high relevance, and low, medium and high rigour (see online supplemental file 3 for detail). Reasons for each assessment were outlined and logged for each article and compared with each other to ensure consistency. Ambiguous cases of relevance or rigour were discussed with the wider project team as they arose. A decision was made by the project team to exclude articles assessed to have data of low relevance or low rigour to ensure a more robust dataset with which to build the final programme theory and CMOCs.

Step 5: synthesising the evidence and drawing conclusions

Once data from the remaining articles were extracted and categorised, key outcome themes were identified by discussion with the whole team. These themes and categories were presented to the stakeholders for comment and feedback, to determine what was most important to focus on, if they felt anything had been overlooked and if any changes or refinements should be made. Four key outcome areas (getting and keeping members, personnel, support of other organisations and funding/income) were settled on. Data were then organised under these headings in the form of ‘If-then’ statements that provided initial explanations of how, why, for whom and in which contexts these outcomes might arise, initially by TM but with input from DB and TA. These were then further refined, with guidance from GW, using a realist logic of analysis to identify cause-and-effect chains in the data and finally elaborated into CMOCs.29 Related CMOCs were then grouped together to create recommendations for practice or policy that also acted as a summary of the CMOCs found. Diagrams of the factors found affecting sustainability, and how they are likely to relate to each other within an overall programme theory, were also designed through team discussion and drawn by TM.

Patient and public involvement

The research question was developed during the authors’ previous work with community interventions (eg, but not limited to, Meeting Centres)12 13 and the practical problems encountered with sustaining such interventions expressed both by personnel and by members of the public attending. This review mainly involved the gathering of secondary data so did not involve patients or public directly as study participants. However, people with dementia, their family and friends, intervention staff and volunteers, and other community stakeholders were consulted as content experts throughout, informing the search strategy, data synthesis, development of materials and channels for dissemination. More information on our stakeholder consultation process can be found under step 1: locating existing theories and step 5: synthesising the evidence and drawing conclusions.

Results

In total, 61 articles were coded to develop the CMOCs used to refine and expand our initial programme theory (see online supplemental file 4) for a detailed list of included articles). They were published between 1990 and 2020, and ranged in type: most were either peer-reviewed journal articles (28) or formal reports/evaluations (18); information guides (8), news feature articles (3), doctoral theses (2) and conference presentation paraphernalia (2) were also analysed. About half of these articles (33) were authored (or coauthored) in the UK, consistent with a proportion being identified informally through UK-based stakeholders (see figure 2). Four articles had international authorship. Other countries of origin (or co-origin) comprised the US (8), Netherlands (7), Germany (5), Canada (4), Italy (4), Norway (3), Poland (3), Australia (2), Ireland (2), Sweden (2), Chile (1), Japan (1), Portugal (1) and Thailand (1). The type of intervention discussed in these articles varied broadly, including: day centres/day care, social activities, sports and exercise initiatives, peer support groups, arts and crafts groups, singing and music groups, cognitive stimulation, gardening activities and other outdoor activities. Many interventions had multiple and overlapping elements, for example, a sports activity may have a social function, a drop-in day centre may have exercise and cognitive stimulation activities, or a craft club may have peer support built in. When an article’s remit was general (for example community support services, outdoor activities, social and leisure activities or third sector groups), data were included from the article only if it was relevant to our programme theory and the kind of interventions outlined in the inclusion criteria (see online supplemental file 3).

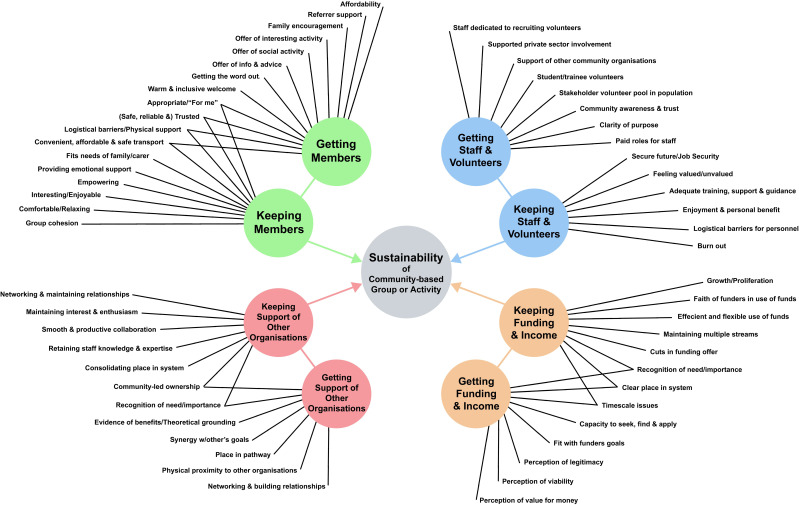

Figure 2.

Factors affecting the sustainability of community-based groups and activities.

bmjopen-2020-047789supp004.pdf (185.6KB, pdf)

Our analysis, together with stakeholder input, identified four critical areas affecting the sustainability of an intervention: members, staff and volunteers, support of other organisations and funding/income. These were each subdivided into ‘getting’ and ‘keeping’ outcomes in recognition of changes in focus over time regarding these areas, and likely different contexts and mechanisms involved as an intervention continues. Figure 2 shows an overview of factors leading to the getting and keeping of members, staff and volunteers, support of other organisations and funding/income, found in the article data (individual diagrams tracing factors for each critical area can be found in online supplemental file 5).

bmjopen-2020-047789supp005.pdf (2.9MB, pdf)

Our analysis of the data produced 201 CMOCs (outlined in full in online supplemental file 6), all covered by the above eight subdivisions. These CMOCs provide causal explanations relating to sustainability of community-based groups and activities either at the level of the individual, organisation or wider. Due to the high number of CMOCs, they were further organised by grouping them under practical recommendations that could follow. These recommendations are not simply an end conclusion, but were also part of the data synthesising process, as they act as a way in which to categorise and summarise the large number of CMOCs. Examples of how several grouped CMOCs were related to a recommendation can be seen in table 1.

Table 1.

Examples of CMOCs leading to recommendations

| Recommendation | CMOCs |

| Getting members: Ensure a warm, welcoming, non-stigmatising introduction, with strong staff interpersonal skills and an appealing venue |

CMOC 3: If facilitators are knowledgeable and empathetic, with good interpersonal skills (C), an initiative will be perceived as more welcoming and inclusive (O), as they will be better at understanding needs, engaging and building trust with potential members and their families (M).41–46 CMOC 4: If an initiative has an informal, unrushed and warm welcome on first visit (C), then people are more likely to want to return (O), as they are more likely to find the experience relaxing and enjoyable, not uncomfortable and intimidating (M).45 47–50 CMOC 5: If potential members have had poor previous experiences with groups or activities (dementia related or not) (C), they may not want to try another group or activity (O), because they think the experience will be similar and will want to avoid it (M).42 46 51 52 CMOC 6: If time is taken for personal contact, home visits or taster sessions with potential members (C), then people are more likely to come (O), as they will feel more familiar with the initiative and more trusting of those running it (M).41 43 52–55 CMOC 7: If an initiative is familiar and trusted, or local and well-integrated with other organisations in the community (C), then people are more likely to come (O), as its links to familiar things that they trust will make it less intimidating (M).42 46 47 53 56–61 CMOC 8: If an intervention is based in familiar surroundings in, and open to, the community (C), then people are more likely to come (O), because potential members will find the normalcy, lack of stigma and chance for social integration appealing (M).43 46 53 57 62–67 CMOC 9: If a venue is dementia-friendly, comfortable and accessible (C), people are more likely to come (O), as they will not have concerns about comfort or access (M).53 60 68 69 |

| Keeping members: Keep activities relaxed, loose and focused on the social and encourage friendships and peer support |

CMOC 47: If there is group cohesion and mutual trust between members (C), then a group is more likely to sustain (O), because members will feel more solidarity and investment in the group (M).70 CMOC 48: If friendships between members are encouraged, recognised and supported by staff and activities (C), then people are likely to keep coming (O), as they will feel more supported, comfortable and engaged, and able to support each other (M).48 59 71–73 CMOC 49: If an intervention is too focused on agendas, rules and expectations (C), then people may stop coming (O), because they feel pressured, restricted and unable to relax and enjoy the social and emotional benefits important to them (M).49 50 68 72 74–76 CMOC 50: If the pace of activity through the day/session is too fast and strict (C), then people may stop coming (O), because they will struggle to stay engaged and will not enjoy themselves (M).48 53 62 66 77 CMOC 51: If ample informal time is made for socialising, peer support and feedback (C), then members are more likely to keep coming (O), as they will be more likely to feel comfortable and supported (M).45 48 53 55 63 67 70 72 74–80 CMOC 52: If there is opportunity to have communal eating and relaxing in a ‘cosy’ environment (C), then members are more likely to keep coming (O), as this will provide comfort and foster group cohesion (M).45 70 |

CMOCs, context–mechanism–outcome configurations.

bmjopen-2020-047789supp006.pdf (196.9KB, pdf)

Recommendations for practice

In total, 41 recommendations for practice were drawn from the CMOCs as can be seen in table 2.

Table 2.

Recommendations for practice (for a full list of CMOCs, see online supplemental file 6)

| Getting members | Keeping members |

| Emphasise the social aspects of your intervention, including food and refreshments, for wide appeal CMOC 1–CMOC 245 53 55 62–64 67 69 80 Ensure a warm, welcoming, non-stigmatising introduction, with strong staff interpersonal skills and an appealing venue CMOC 3–CMOC 941–69 Foster understanding and support from trusted friends, family and health professionals, as their encouragement can be key CMOC 10–CMOC 1441 43 46 47 52 53 59 61 63 67 70 78 80–84 Provide meaningful activities that have resonance with people’s interests and experience, personal history and culture CMOC 15–CMOC 2046 49 50 52 53 55 58 61–63 67–70 72 74–77 82 85–89 Be sensitive to differences in abilities, ages and stages and aim to empower members rather than avoid challenges for them CMOC 21–CMOC 2442 48 53 63 65 67–69 74 78 84 Offer information and advice to connect with a broad range of people who may be in need CMOC 2547 49 50 59 78 90 Ensure people can get there easily, safely, reliably and cheaply CMOC 26–CMOC 3041–43 49 50 52–54 58 61 64–66 69 70 78 81 83 87 90 91 Stay in constant contact with potential referrers and keep them involved CMOC 31–CMOC 3246 51 56 59 60 66 79 80 84 Your ‘public relations’ strategy should focus on who the intervention is for and what people can expect, and use existing networks to spread your message CMOC 33–CMOC 4141–43 46 49–54 56 59 61 64 66 67 71 72 75 77–80 83 85 87–89 92–94 Consider simple and easy self referral CMOC43–CMOC 4643 49 50 52 62 66 79 81 84 85 88 93 |

Keep activities relaxed, loose and focused on the social, and encourage friendships and peer support CMOC 47–CMOC 5245 48–50 53 55 59 62 63 66–68 70–80 Encourage normalised activities and social integration outside of the group to empower members and reduce stigma CMOC 53–CMOC 5742 43 46 51–54 57 59 62–64 66 67 71 72 76 81 95 Be person-centred: Give members input into planning and decision-making, and respect their individual needs and autonomy CMOC 58–CMOC 6341 45–51 53 57 60 64 66 68 70–72 76 79 89 96 Talk to family or care partners about what arrangements and support they need in place CMOC 64–CMOC 6543 49 50 52–55 59 62 65 66 78 83 Be sensitive to differences in abilities, ages and stages and have strategies to differentiate and manage activities so needs don’t clash CMOC 66–CMOC 7042 46 48–54 62–66 71 72 76 79–81 83 Ensure your venue is comfortable, stable and familiar, with adequate facilities and multiple spaces for use CMOC 71–CMOC 7248 53 60 68 94 Stability and reliability matters to members, so aim for structure and minimise disruption CMOC 73–CMOC 7741–43 45 48 52 53 66 70–72 77 78 80 |

| Getting staff and volunteers | Keeping staff and volunteers |

| Network proactively: Engage in outreach activities to boost visibility and awareness; approach other groups and organisations for help CMOC 78–CMOC 8351 53 55 61 63 64 66 72 74 82 85 88 89 94 96 Get to know potential stakeholder groups in the local population that may provide a reliable volunteer base, and consider how to reach out to them CMOC 84–CMOC 9058 61 67 70 86 88 96–98 Not all personnel need expertise, but ensure facilitators have good interpersonal and leadership skills, and your volunteer workforce is reliable CMOC 91–CMOC 9543 55 56 63 66 76–78 80 84 |

Foster flexibility, collaboration and communication skills in personnel to create a healthy and effective working environment CMOC 96–CMOC 9764 65 81 84 98 Plan strategies to maintain the satisfaction and enjoyment of staff and volunteers, and to avoid burnout CMOC 98–CMOC 10443 48 57 63 66 75 79 80 89 If possible, have financial support in place for staff roles and volunteers activities, so they will feel secure and valued CMOC 105–CMOC 10856 72 78 84 89 92 |

| Getting Support of Other Organisations | Keeping support of other organisations |

| Focus on raising awareness and communicating value both to professionals and the community, involving them where possible CMOC 110–CMOC 11442 44 46 47 55 59 60 66 75 80 84 85 89 91 95 Approach and ask other community organisations if they can help with venue, resources, training, volunteers or contacts CMOC 115–CMOC 11851 53 57 63 67 70 72 74 76 77 80 82 85 97 98 Use your physical location (venue or neighbourhood) as an opportunity to build links with others sharing that space CMOC 119–CMOC 12146 47 53 63 64 67 84 Seek out like-minded groups to band together with and share knowledge, resources, contacts and strategy CMOC 122–CMOC 12447 72 82 To avoid conflict with other organisations, minimise overlap, involve them or offer them something of benefit CMOC 125–CMOC 13146 47 51 56 65 66 72 75 77 84 89 91 93 |

Maintain constant contact and information sharing with the organisations, services and referrers you work with, with a dedicated person responsible if possible CMOC 138–CMOC 14244 46 49 50 55 56 60 72 82 84 89 Seek authoritative external advice on overcoming differences in culture with other organisations, and up-skilling staff for collaboration CMOC 143–CMOC 14846 56 64 65 75 81 82 84 91 Take time to formally plan how collaboration will work, involving collaborators in that planning CMOC 149–CMOC 15246 49 50 56 66 75 |

| Getting funding and income | Keeping funding and income |

| Ensure communication is clear about what the intervention does and its value CMOC 153–CMOC 16344 46 51 56 61 66 75 80 84 85 94 99 Build ‘social capital’ and forge partnerships with other community organisations to help with costs and boost the case for viability and value for money CMOC 164–CMOC 16961 65 66 75 80 81 83–85 92 98–100 Learn how to effectively plan and network to find funding, through knowledge-sharing with like-minded groups and seeking external advice CMOC 170–CMOC 17542 51 60 65 66 85 91 96 99 Initiatives in rural areas should make clear the particular challenges that they face when seeking funding CMOC 176–CMOC 17955 89 96 Find out what the national priorities are for dementia, and see if you can tailor your activities to fit; if not, lobby to change the national agenda CMOC 180–CMOC 18444 46 47 55 56 60 64 81 82 85 89 91 92 96 100 101 |

Keep in touch with previous, current and potential funders on an ongoing basis, as this will help when applying in the future CMOC 185–CMOC 18851 60 66 75 99 Pay attention to how money can be put to use most efficiently and effectively for the benefit of all by co-operating and sharing with other organisations CMOC 189–CMOC 19075 80 81 83 85 98 Plan a long-term strategy to build a portfolio of multiple income streams that are flexible in what they contribute to paying for CMOC 191–CMOC 19449 50 75 85 89 99 Ensure someone has the time and expertise to continually seek and apply for funding CMOC 195–CMOC 19775 85 89 Emphasise deep learning and experience as an asset when calling for longer term funding CMOC 198–CMOC 20144 55 56 81 82 84 91 92 101 |

CMOC, context–mechanism–outcome configuration.

Data regarding getting and keeping members was the most abundant and showed most consensus. As may be expected, boosting the motivation and understanding of potential referrers, while lowering bureaucratic and logistical barriers, was important to getting members (CMOC 10–CMOC 14; CMOC 31–CMOC 46; CMOC 64–CMOC 65). Transport from home to venue was particularly key: not just its availability, but people’s experiences of the accessibility, appropriateness and convenience of it (CMOC 10–CMOC 14). Other salient mechanisms involved how respected, valued and comfortable members felt, or perceived they would feel should they attend: both for overcoming initial anxiety and stigma and fostering a happy, cohesive group (CMOC 3–CMOC 9; CMOC 15–CMOC 24; CMOC 53–CMOC 63; CMOC 71–CMOC 72). Staff attitudes and a comfortable, accessible venue play a role in this, but also planned practices, such as involving members in decision making (CMOC 58–CMOC 63), differentiating activities for need and ability (CMOC 21–CMOC 24; CMOC 66–CMOC 70) and ensuring enough opportunity and time for socialising (reported to be of high importance to people no matter what the intervention or activity) (CMOC 1–CMOC 2; CMOC 47–CMOC 52). The stability and reliability of an intervention was also important, though often at odds with nature of groups run informally with few personnel and unstable income (CMOC 73–CMOC 77). Overall, ensuring individual wants and needs are met—that people they feel they are gaining something useful and appropriate to them in particular—was important to keeping members long term (CMOC 47–CMOC 72).

Data regarding getting and keeping staff and volunteers were least abundant of the four critical outcome areas, though working with other organisations was frequently alluded to as helpful in finding personnel (CMOC 78–CMOC 83). Data regarding skills of personnel were largely around the role of communication and collaboration in creating an encouraging and effective environment for staff and volunteers (CMOC 84–CMOC 97). Context was key with regards to the availability of potential volunteers in the local population, as this could be very different depending on location (eg, rural or urban), with different likely mechanisms requiring different approaches to finding and encouraging volunteers from different demographic groups (CMOC 84–CMOC 90). With regard to keeping volunteers, issues raised included the importance of maintaining work satisfaction and avoiding burnout, and having financial support available (CMOC 98–CMOC 108).

Getting and keeping support of other organisations, such as other community groups, health and social care services, third sector bodies, local authorities and local businesses was a widely recurring theme in the data. Actively involving other organisations, minimising overlap, sharing knowledge and resources and offering something of benefit were all ways to encourage them to feel invested in supporting an intervention rather than threatened or indifferent to it (CMOC 122–CMOC 131), in addition to proactive awareness raising and networking (CMOC 110–CMOC 121). Good collaboration planning (with expert advice on collaborative working), along with continual attention to maintaining communication, were strategies to avoid problems developing or loss of enthusiasm with partner organisations (CMOC 138–CMOC 152).

On getting and keeping funding and income, salient CMOCs again involved continual networking and communication, for the reason that this would support multiple mechanisms: by reducing costs through sharing and partnership; boosting visibility, legitimacy and value in the eyes of potential and existing funders; and helping to locate more funding and income opportunities (CMOC 153–CMOC 175; CMOC 185–CMOC 190). Data made some reference to the importance of strategic planning in finding and managing funds, with outside expertise and dedicated personnel helpful in carrying this out (CMOC 170–CMOC 175; CMOC 191–CMOC 197). While tailoring an intervention to national (and therefore funders’) priorities may increase its chances of obtaining funding, this is not always possible or desirable for a group (CMOC 180–CMOC 184). Groups in rural areas particularly, or experienced groups unable to find anything but short-term solutions, may have to raise greater awareness with commissioners and policy-makers about the specific challenges that face them, and lobby for change to ensure better conditions for groups in their situation long term (CMOC 170–CMOC 179; CMOC 198–CMOC 201). For example, rural groups with a small number of members and personnel can struggle to meet funders demands, especially if put in competition with larger, well-resourced organisations.

Recommendations for policy and commissioning

In addition, 13 recommendations for policy-making and commissioning were also drawn (see box 1), for the most part mirroring those for practice and drawing on the same CMOCs.

Box 1. Recommendations for commissioning/policy-making (for a full list of context–mechanism–outcome configuration (CMOCs), see online supplemental file 6).

Recommendations for commissioning/policy-making.

Service users value the social side of an intervention highly, often more than the intervention or activity itself

CMOC 1–CMOC 2; CMOC 47–CMOC 5343 45 46 48–50 52–55 57 59 62–64 66–80

Service users need to feel an intervention is ‘for them’ to want to attend and keep attending

CMOC 15–CMOC 24; CMOC 66–CMOC 7042 46–55 58 61–72 74–89

Lack of appropriate transport can be a major barrier to an intervention getting and keeping attendees

CMOC 26–CMOC 30; CMOC 6541–43 49 50 52–55 61 62 64–66 69 70 78 81–83 87 90 91

Health and social care services that may refer to an intervention need incentive and guidance to do so

CMOC 42–CMOC 44; CMOC 134–CMOC 13552 55 66 74 81 82 84 85 93

To retain staff and volunteers there needs to be adequate financial support in place for roles and activities

CMOC 105–CMOC 10955 56 72 78 84 89 92

Established community organisations, including local authorities, can offer help in a number of ways to enable small-scale interventions to flourish

CMOC 115–CMOC 11851 53 57 63 67 70 72 74 76 77 80 81 85 97 98

Access to advice on how to create partnerships, collaborate and overcome differences in culture with other organisations can help

CMOC 143–CMOC 14846 56 64 65 75 81 82 84 91

Access to advice on how to effectively plan and network to help find and manage funding and income can help

CMOC 170–CMOC 17542 51 60 65 66 85 91 96 99

Commissioners should be flexible and accommodating of the challenges facing small groups regarding evidence gathering

CMOC 176–CMOC 17955 89 96

Policy-makers should ensure policy meets local needs with adequate, protected and accessible resources attached

CMOC 180–CMOC 182; CMOC 18444 46 47 55 56 60 64 81 82 85 89 91 92 96 100

Longer-term funding, with simplified application processes, would help smaller initiatives with less capacity to continue

CMOC 195–CMOC 19775 85 89

Longer term funding to support what is already being done will help retain and develop learning and practice on how best to meet local need

CMOC 198–CMOC 20044 55 56 81 82 84 91 92

Authorities and national organisations can help create conditions that encourage support for small initiatives, though policy, leadership and commissioning

CMOC 132 – CMOC 13744 52 55 56 64 74 82

The final recommendation covers CMOCs unique to policy-making and commissioning, highlighting issues such as the detrimental effect of a disjoin between national policy and local need on an intervention finding support (as by adhering to one they will neglect the other) (CMOC 132). Practices that could benefit the sustainability of community interventions included ring-fencing funding specifically for dementia-targeted community initiatives; commissioning health and social care services to work with community initiatives; and developing health pathways around existing community networks (CMOC 133–CMOC 135). National and official organisations can also encourage a more strategic, joined up direction regarding community-based dementia support by showing leadership in working with smaller, local initiatives and support for potential private sector partners (CMOC 136–CMOC 137).

Discussion

Summary of findings

Being able to continually get and hold on to members, staff and volunteers, the support of other services and organisations, and funding/income are the key factors in the long-term sustainability of a community-based intervention for people affected by dementia. There are multiple mechanisms that feed into these suboutcomes, sensitive to context. Ability to attract members was found to be driven by perceptions that a group or activity was ‘for them’, and expectations they would be welcomed, respected and supported without stigma once attending, as well as having motivated referrers and low logistical barriers, including transport. Members are more likely to keep attending if they feel comfortable, at home, respected and empowered, with individual needs understood. Opportunity for socialising was found to be of high importance no matter what the intervention type, with stability and reliability also important. Networking and outreach were found to be important in getting staff and volunteers; feeling satisfied, valued and supported (including financially) was important in keeping them. Proactive measures to raise awareness and involve other organisations, avoiding conflict and sharing knowledge and resources, were found to help in securing essential support, though requiring significant maintenance through skilled communication, planning and working practices. Such networking and collaboration were found to be helpful in finding and securing funding and income, with skilled planning and management of multiple income streams helpful in sustaining long term. However, the often short-term nature of funding was found to be a barrier to retaining deep learning and experience, and disjoins between national policy and local need a barrier to securing both funding and wider support. Challenges in meeting funders’ requirements and overcoming logistical barriers were especially acute for small-scale and rural groups.

Strengths and limitations

This review was designed to gather evidence regarding how regularly meeting community-based interventions for people affected by dementia can be sustained, not on the efficacy/effectiveness of interventions of this type, hence conclusions regarding the latter are beyond its scope. Literature was limited as this research question is not commonly the main focus of study in dementia care research. This meant some CMOCs arrived at were the result of abundant data sources, while others were not, hence the CMOCs here vary in robustness (see online supplemental file 6). While efforts were made to exclude data of low rigour (see online supplemental file 3), it is the nature of a realist review to include data from a variety of source types to build a theoretical model piecemeal; not all of the data were of equal depth and detail and many will not meet the highest level of empirical rigour, rather they contribute together in a way that is useful to the theoretical constructs that are the CMOCs and overall programme theory.33 The results of this review therefore should be taken as theory and sit in relation to other research: SCI-Dem provides a theoretical framework which can be put to the test and further refines by subsequent empirical research.33 The breadth of intervention types covered in this review is on the one hand a strength, as it has enabled the surfacing of commonalities in experience likely relevant to a wide range of real-world initiatives broadly in the same category; on the other hand, it means this review cannot be specific on certain details. An example is that little could be concluded on the cost-effectiveness or economic functioning of the interventions covered, because details were both too scant and too specific to draw robust CMOCs that might usefully be applicable to others.

The practice of one researcher carrying out the bulk of article selection and data analysis, with a second researcher independently checking 10% at each stage for consistency (along with regular input and discussion with other members of the research team) is common in realist review, but nevertheless can be seen as a limitation, as in Cochrane-style systematic reviews double-screening by two reviewers independently is recommended for greater reliability of results. However, it should be noted realist review is a theory-driven interpretive approach with significant differences to more traditional forms of systematic review29; that is, the aim is to develop an evidence-informed theory rather than a comprehensive summation of all research data available on a particular research question.

Recommendations and comparison with existing literature

Recommendations for practice and policy are presented in table 2, Box 1, in the results section. However, they also highlight some common problems for which there may be no easy solution, for example, what to do in rural areas where public transport coverage is poor and potential members and volunteers are few and widespread, given that transport to venue is a key factor in getting and keeping members. The issue of whether interventions can be entirely self-sustaining or must rely on service-level agreements and grant funding is also a key one. This review suggests that costs can be reduced and income opportunities found by proactive networking and collaborative working; though rather than removing the need for grant funding, this is, more likely, useful in leveraging it, adding to it and helping it to go further. Recent research into whether social enterprises delivering adult social care services (not dementia specific) could be self-sustaining suggests that marketing is key but needs to focus on building relationships with stakeholders at multiple levels rather than adopting an approach akin to selling a product36: networking and marketing are closely bound up with each other. Delivering social quality as well as service quality, having a hybrid workforce and diverse income streams to strengthen financial viability and reduce reliance on grants were also found to help.37 This review echoes all of these points with regards to dementia-targeted community-based interventions, in particular that interventions cannot sustain without a cultivated support network around them, as well as careful collaborative financial planning and management.

The emphasis found in this review on the value to members of social activity and a respectful, empowering person-centred approach, reinforces the benefits of community-based initiatives and regular social activity, both for people living with dementia and the people who care for them.12–19 However, the time-limited nature of most research in this area is unhelpful when seeking data on the long-term sustainability of such interventions, with a large number of articles excluded from this review due to this. Recent systematic reviews have found that psychosocial interventions tend to be short term, with short-term trials only measuring short-term impact, and a pressing need for more longer-term studies with larger sample sizes.14 38 However, there is a ‘chicken and egg’ problem: if policy and commissioning is hesitant to support interventions unless there is evidence of robust statistical effects, then such interventions will struggle to sustain long enough, in enough abundance, to have the numbers to carry out the research required to produce that evidence. Equally, if research focuses only on efficacy/effectiveness without attention to the implementation process, and reporting of how costs were met and resources, personnel, and service users were found, then little can be learnt about sustaining them.

Future research directions

When drafting inclusion criteria for this review in 2018 it was decided to focus on interventions that brought people together to meet physically and socially, as distinct from community services that go into people’s homes. It did not take into account virtual community activities or communities at-a-distance, which at the time seemed like a distinct niche. In 2020, however, this kind of activity became much more important, and integrated with the activities of existing community groups that met physically prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. With COVID-19 the landscape for community-based interventions has changed significantly, presenting further unprecedented challenges, but the need for groups that connect people socially remains acute. A recent study by the Alzheimer’s Society11 revealed COVID-19 restrictions have had particularly negative impacts on the health and well-being of people affected by dementia and their carers, a finding echoed by the Alzheimer’s Disease International’s update report for 2020.39 Restrictions have forced changes to routine, causing anxiety and strain in relationships; led to a reduction in skills and confidence; and increased pressure on home carers, not least through the erosion of support systems.40 Many support initiatives will have ceased operating either temporarily or permanently. As the effects of the pandemic continue to be felt, there is an urgent need for community-based interventions to find ways to keep going or re-establish quickly when emerging from COVID-19 restrictions. While the data used in this review predated the pandemic, it can provide a framework for new research to look at what sustainability-impacting elements have been affected and how. This review presents a theoretical model of the factors and mechanisms involved in the long-term sustainability of community-based interventions. As such it is for further research to put this model to the test by comparing it empirically with real-world interventions going forward, which will further refine and add to this programme theory in a postpandemic climate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Alzheimer's Society. Dr Shirley Evans (Association for Dementia Studies, University of Worcester) contributed to the writing of the protocol for this review. Clive Kennard (information specialist, University of Worcester), helped design, pilot and carry out the formal search. The authors would like to thank all those who shared their invaluable experience and contributed to advising and guiding this project as a stakeholder consultant: Alzheimer’s Society research monitors Sue Comely, Maggie Ewer and Mair Graham; Philly Hare, Rachael Litherland, Damian Murphy and Rachel Niblock of DEEP/Innovations in Dementia, and all who attended the national meeting of DEEP groups at Wooodbrooke, Birmingham, July 2019; Teresa ‘Dory’ Davies, James McKillop and Dreane Williams of DEEP; Judith Baron and the Face It Together DEEP group; Jill Turley and The Buddies DEEP group; the Friends for Life DEEP group; Kim Badcock of Kim’s Cafe (Denmead, Havant and Waterlooville, Hampshire); Jo Barrow and the Forget Me Not Lunch and Friendship Club (Bicester, Oxfordshire); Elizabeth Bartlett of the Laverstock Memory Support Group (Wiltshire); Shirley Bradley of Friends of the Elderly (Worcester); David Budd of Our Connected Neighbourhoods (Stirling); Di Burbidge of Liverpool DAA Diversity Sub-Group and Chinese Wellbeing (Liverpool); Kishwar Butt of the South Asian Ladies’ Milaap Group (Wolverhampton); Michelle Candlish of Ceartas Advocacy (Kirkintilloch, East Dunbartonshire); Annette Darby of Brierly Hill Health and Social Care Centre (West Midlands); Sue Denman of Solva Care (Haverfordwest); Gerry Fouracres of Scrubditch Farm (Cirencester); Graham Galloway of Kirrie Connections (Kirriemuir, Angus); Reinhard Guss; Deborah Harrold of Agewell CIC (Oldbury, West Midlands); June Hennell; Jacoba Huizenga of Health and Social Care in Communities, Utrecht (Netherlands); Lynden Jackson of the Debenham Project (Suffolk); Ghazal Mazloumi of Trent Dementia Services Development Centre; Cheryl Poole of Leominster Meeting Centre; Anita Tomaszewski and Jennifer Williams of Me, Myself and I (Briton Ferry, Neath Port Talbot); Dame Louise Robinson; Droitwich Meeting Centre; Leominster Meeting Centre; the members of the UKMCSP National Reference Group; and Jennifer Bray, Shirley Evans, Nicola Jacobson-Wright, Chris Russell and Mike Watts of the Association for Dementia Studies, University of Worcester.

Footnotes

Twitter: @ThomasMortonADS

Contributors: DB and TA conceptualised the study (along with SBE of the University of Worcester, who cowrote the protocol but does not meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship of this paper). GW and TM had input into developing the study (along with information specialist CK of the University of Worcester, who helped design the search strategy but does not meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship of this paper). The study was conducted by DB as principal investigator, TA as project manager, TM research associate and GW providing methodological expertise. TM wrote the first draft of this manuscript. GW, DB and TA critically contributed to and refined the originally submitted manuscript, as well as responses to reviewers’ comments and the revised manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by The Alzheimer’s Society, Grant No: 402, AS-PG-17b-023. Gold Open Access Article Processing Charges met by the University of Worcester.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Alzheimer’s Society.

Competing interests: GW is Deputy Chair of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Prioritisation Committee: Integrated Community Health and Social Care (A).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. This study was a qualitative review of secondary data, hence no new primary dataset was generated. However, we can share more information on what data was extracted and how it was analysed if requested. Please contact TM at t.morton@worc.ac.uk, ORCID 0000-0001-8264-0834.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.World Health Organisation . Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017-2025. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2017. https://www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/action_plan_2017_2025/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office for National Statistics (ONS) . Living longer: caring in later life. London: ONS, 2019. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/ageing/articles/livinglongerhowourpopulationischangingandwhyitmatters/2019-03-15 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Care Quality Commission . The state of health care and adult social care in England 2018/19. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Care Quality Commission, 2019. https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20191015b_stateofcare1819_fullreport.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health . Prime Minister’s challenge on dementia 2020. London: Department of Health, 2015. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/414344/pm-dementia2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5.Incisive Health . Care deserts: the impact of a dysfunctional market in adult social care provision. London: Incisive Health, 2019. https://www.incisivehealth.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/care-deserts-age-uk-report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Age UK . Briefing: health and care of older people in England 2019. London: Age UK, 2019. https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/reports-and-publications/reports-and-briefings/health-wellbeing/age_uk_briefing_state_of_health_and_care_of_older_people_july2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alzheimer’s Society . A lonely future: 120,000 people with dementia living alone, set to double in the next 20 years. London: Alzheimer’s Society, 2019. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/news/2019-05-15/lonely-future-120000-people-dementia-living-alone-set-double-next-20-years [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav 2009;50:31–48. 10.1177/002214650905000103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci 2015;10:227–37. 10.1177/1745691614568352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brodaty H, Donkin M. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2009;11:217–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alzheimer’s Society . Worst hit: dementia during coronavirus. London: Alzheimer’s Society, 2020. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-09/Worst-hit-Dementia-during-coronavirus-report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooker D, Evans S, Evans S, et al. Evaluation of the implementation of the meeting centres support program in Italy, Poland, and the UK; exploration of the effects on people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2018;33:883–92. 10.1002/gps.4865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans S, Evans S, Brooker D, et al. The impact of the implementation of the Dutch combined meeting centres support programme for family caregivers of people with dementia in Italy, Poland and UK. Aging Ment Health 2020;24:280-290. 10.1080/13607863.2018.1544207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lord K, Beresford-Dent J, Rapaport P, et al. Developing the new interventions for independence in dementia study (nidus) theoretical model for supporting people to live well with dementia at home for longer: a systematic review of theoretical models and randomised controlled trial evidence. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2020;55:1–14. 10.1007/s00127-019-01784-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDermott O, Charlesworth G, Hogervorst E, et al. Psychosocial interventions for people with dementia: a synthesis of systematic reviews. Aging Ment Health 2019;23:393–403. 10.1080/13607863.2017.1423031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van't Leven N, Prick A-EJC, Groenewoud JG, et al. Dyadic interventions for community-dwelling people with dementia and their family caregivers: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr 2013;25:1581–603. 10.1017/S1041610213000860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dröes R-M, van der Roest HG, van Mierlo L, et al. Memory problems in dementia: adaptation and coping strategies and psychosocial treatments. Expert Rev Neurother 2011;11:1769–82. 10.1586/ern.11.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dröes R-M, Meiland F, Schmitz M, et al. Effect of combined support for people with dementia and carers versus regular day care on behaviour and mood of persons with dementia: results from a multi-centre implementation study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2004;19:673–84. 10.1002/gps.1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dröes R-M, Meiland FJM, Schmitz MJ, et al. Effect of the meeting centres support program on informal carers of people with dementia: results from a multi-centre study. Aging Ment Health 2006;10:112–24. 10.1080/13607860500310682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wittenberg R, Hu B, Barraza-Araiza L, et al. Projections of older people with dementia and costs of dementia care in the United Kingdom, 2019-2040 (CPEC working paper 50). London: LSE, 2019. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-11/cpec_report_november_2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dröes R-M, Breebaart E, Meiland FJM, et al. Effect of meeting centres support program on feelings of competence of family carers and delay of institutionalization of people with dementia. Aging Ment Health 2004;8:201–11. 10.1080/13607860410001669732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dröes RM, Meiland FJM, Schmitz M, et al. Effect of combined support for people with dementia and carers versus regular day care on behaviour and mood of persons with dementia: results from a multicentre implementation study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2004;19:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Booth A, Clarke M, Ghersi D, et al. An international registry of systematic-review protocols. Lancet 2011;377:108–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60903-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morton T, Atkinson T, Brooker D, et al. Sustainability of community-based interventions for people affected by dementia: a protocol for the SCI-Dem realist review. BMJ Open 2019;9:e032109. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pawson R. Evidence-based policy: a realist perspective. London: Sage Publications, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, et al. Realist review--a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10(Suppl 1):21–34. 10.1258/1355819054308530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jagosh J, Macaulay AC, Pluye P, et al. Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: implications of a realist review for health research and practice. Milbank Q 2012;90:311–46. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00665.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Astbury B, Leeuw F. Unpacking black boxes: mechanisms and theory building in evaluation. Am J Eval 2010;31:363–81. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, et al. Development of methodological guidance, publication standards and training materials for realist and meta-narrative reviews: the RAMESES (Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses - Evolving Standards) project. Health Serv Deliv Res 2014;2:1–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DEEP . DEEP: the UK network of dementia voices website, 2020. Available: http://dementiavoices.org.uk

- 31.Greenhalgh T, Peacock R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. BMJ 2005;331:1064. 10.1136/bmj.38636.593461.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Booth A, Harris J, Croot E, et al. Towards a methodology for cluster searching to provide conceptual and contextual "richness" for systematic reviews of complex interventions: case study (CLUSTER). BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:118. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G. Realist synthesis – an introduction. ESRC working paper series. London: ESRC, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong G. Data gathering in realist reviews: Looking for needles in haystacks. In: Emmel N, Greenhalgh J, Manzano A, eds. Doing realist research. London: Sage Publications, 2018: 131–45. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pawson R. Digging for nuggets: How ‘bad’ research can yield ‘good’ evidence. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2006;9:127–42. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Powell M, Osborne SP, enterprises S. Marketing, and sustainable public service provision. International Review of Administrative Sciences 2020;86:62–79. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Powell M, Gillett A, Doherty B. Sustainability in social enterprise: hybrid organizing in public services. Public Management Review 2019;21:159–86. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oyebode JR, Parveen S. Psychosocial interventions for people with dementia: an overview and commentary on recent developments. Dementia 2019;18:8–35. 10.1177/1471301216656096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barbarino P, Lynch C, Bliss A. From plan to impact III: maintaining dementia as a priority in unprecedented times. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2020. https://www.alzint.org/u/from-plan-to-impact-2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 40.Canevelli M, Valletta M, Toccaceli Blasi M, et al. Facing dementia during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68:1673–6. 10.1111/jgs.16644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Actifcare . Best practice recommendations from the Actifcare study: access to community care services for home-dwelling people with dementia and their carers. Bangor: Dementia Services Development Centre Wales, 2017. http://dsdc.bangor.ac.uk/documents/ShortversionBestPracticeRecommendationwithoutsupportingfindings_000.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daykin N, Julier G, Tomlinson A. Review of the grey literature: music, singing and wellbeing. London: What Works Wellbeing, 2016. https://whatworkswellbeing.files.wordpress.com/2016/11/grey-literature-review-music-singing-wellbeing-nov2016.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hochgraeber I, von Kutzleben M, Bartholomeyczik S, et al. Low-threshold support services for people with dementia within the scope of respite care in Germany - A qualitative study on different stakeholders' perspective. Dementia 2017;16:576–90. 10.1177/1471301215610234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McDonald A, Heath B. Developing services for people with dementia. Work Older People 2009;13:18–21. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strandenæs MG, Lund A, Rokstad AMM. Experiences of attending day care services designed for people with dementia - a qualitative study with individual interviews. Aging Ment Health 2018;22:764–72. 10.1080/13607863.2017.1304892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Mierlo LD, Chattat R, Evans S, et al. Facilitators and barriers to adaptive implementation of the meeting centers support program (MCSP) in three European countries; the process evaluation within the MEETINGDEM study. Int Psychogeriatr 2018;30:527–37. 10.1017/S1041610217001922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brooker D, Evans SB, Evans SC. Meeting centres support programme UK: overview, evidence and getting started. Worcester: association for dementia studies, University of worcester, 2017. Available: https://www.worcester.ac.uk/documents/Meeting-Centres-Support-Progamme-Overview-evidence-and-getting-started-Conference-booklet.pdf

- 48.Glover C. Running self-help groups in sheltered and extra care accommodation for people who live with dementia. London: Mental Health Foundation, 2014. https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/dementia-self-help-guide.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reichet M, Wolter V. Sport for people with dementia – implementing physical activity programs (PAP) for people with dementia: results from a German study (conference poster). Dortmund: TU Dortmund University, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reichet M, Wolter V. Implementing physical ACTIVITIY programs for people with dementia: results from a German study. Innov Aging 2017;1:340. 10.1093/geroni/igx004.1247 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.The Me Myself and I Club . The me, Myself and I Club, Briton ferry: a case study in warm humanity and meaningful co-production. Neath Port Talbot: the me Myself and I Club, 2018. Available: https://info.copronet.wales/me-myself-and-i-club-briton-ferry/

- 52.Older People’s Commissioner for Wales . Rethinking respite for people affected by dementia. Cardiff: Older People’s Commissioner for Wales, 2018. http://www.olderpeoplewales.com/en/Reviews/respite.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bould E, McFayden S, Thomas C. Dementia-friendly sport and physical activity guide. London: Alzheimer’s Society, 2019. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-involved/dementia-friendly-communities/organisations/dementia-friendly-sports [Google Scholar]

- 54.Green G, Lakey L. Building dementia-friendly communities: a priority for everyone. London: Alzheimer’s Society, 2013. https://actonalz.org/sites/default/files/documents/Dementia_friendly_communities_full_report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marshall J, Jackson L. Encouraging and supporting the growth of “dementia proactive communities”. Ipswich: Sue Ryder/The Debenham Project, 2015. http://www.the-debenham-project.org.uk/downloads/conference/Supplementary%20contributions/Lynden%20Jackson%20&%20Jo%20Marshall/Lynden%20Jackson%20&%20%20Jo%20Marshall%20-%20Supplementary%20Contribution.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clarke CL, Keyes SE, Wilkinson H, et al. Organisational space for partnership and sustainability: lessons from the implementation of the National dementia strategy for England. Health Soc Care Community 2014;22:634–45. 10.1111/hsc.12134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Health Innovation Network South London . Case study: dulwich helpline and southwark churches care (DH&SCC) – the dementia project, Southwark, South London. London: Health Innovation Network South London, 2015. http://www.hin-southlondon.org/system/resources/resources/000/000/083/original/Case_Study_The_Healthy_Living_Club.pdf?1426083299 [Google Scholar]

- 58.La Rue A, Felten K, Turkstra L. Intervention of multi-modal activities for older adults with dementia translation to rural communities. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2015;30:468–77. 10.1177/1533317514568888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mason T, Slack G. The Debenham project: research into the dementia/memory loss journey for cared-for and carer, 2012-13. Norwich: Norfolk & Suffolk Dementia Alliance, 2013. http://www.the-debenham-project.org.uk/downloads/articles/2014/DebProjResearch_Final_Report_311013.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meiland FJM, Dröes RM, De Lange J, et al. Development of a theoretical model for tracing facilitators and barriers in adaptive implementation of innovative practices in dementia care. Arch Gerontol Geriatr Suppl 2004;38:279–90. 10.1016/j.archger.2004.04.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Research S. Public perceptions and experiences of community-based end of life care initiatives: a qualitative research report. London: Public Health England, 2016. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/569711/Public_Perceptions_of_Community_Based_End_of_Life_Care_Initiatives_Resea.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cahill S, Pierce M, Bobersky A. An evaluation report on flexible respite options of the living well with dementia project in Stillorgan and Blackrock. Dublin: Trinity College, 2014. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331257213_An_Evaluation_Report_on_Flexible_Respite_Options_of_the_Living_Well_with_Dementia_Project_in_Stillorgan_and_Blackrock [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carone L, Tischler V, Dening T. Football and dementia: a qualitative investigation of a community based sports group for men with early onset dementia. Dementia 2016;15:1358–76. 10.1177/1471301214560239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gajardo J, Aravena JM, Budinich M, et al. The Kintun program for families with dementia: from novel experiment to national policy (innovative practice). Dementia 2020;19:488–95. 10.1177/1471301217721863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grinberg A, Lagunoff J, Phillips D. Multidisciplinary design and implementation of a day program specialized for the frontotemporal dementias. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2008;22:499–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meiland FJM, Dröes R-M, de Lange J, et al. Facilitators and barriers in the implementation of the meeting centres model for people with dementia and their carers. Health Policy 2005;71:243–53. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rio R. A community-based music therapy support group for people with alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers: a sustainable partnership model. Front Med 2018;5:293. 10.3389/fmed.2018.00293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gottleib-Tanaka D. Creative expression, dementia and the therapeutic environment (PhD thesis). Vancouver: University of British Columbia, 2006. https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/831/items/1.0076821 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mapes N, Milton S, Nicholls V. Is it nice outside? consulting people living with dementia and their carers about engaging with the natural environment. natural England commissioned reports, number 211. Natural England: York, 2016. http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/publication/5910641209507840 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brataas HV, Bjugan H, Wille T, et al. Experiences of day care and collaboration among people with mild dementia. J Clin Nurs 2010;19:2839–48. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03270.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Casey J. Early onset dementia: getting out and about. Journal of Dementia Care 2004;12:12–13. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oliver-Watkins F, Kendall N, Sow MT. Grow: Report from a two-year Social and Therapeutic Horticultural (STH) programme delivering table-top gardening courses to adults in the community aged 50 and over. Reading: Thrive, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Williams B, Roberts P. Friends in passing: social interaction at an adult day care center. Int J Aging Hum Dev 1995;41:63–78. 10.2190/GHHW-V1QR-NACX-VBCB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Alzheimer’s Australia . The benefits of physical activity and exercise for people living with dementia (Dicussion paper 11. Sydney: Alzheimer’s Australia, 2014. https://www.dementia.org.au/sites/default/files/NSW/documents/AANSW_DiscussionPaper11.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hayes R, Williamson M. Men’s sheds: exploring the evidence for best practice. Melbourne: La Trobe University, 2007. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259313489 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Milligan C, Payne S, Bingley A, et al. Place and wellbeing: shedding light on activity interventions for older men. Ageing Soc 2013;35:124–49. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tuppen J. The benefits of groups that provide cognitive stimulation for people with dementia. Nurs Older People 2012;24:20–4. 10.7748/nop2012.12.24.10.20.c9437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mental Health Foundation . An evaluation of the standing together project. London: Mental Health Foundation, 2018. https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/standing-together-evaluation-WEB.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thrive . Growing4life - a thrive community gardening project: a practical guide to setting up a community gardening project for people affected by mental ill health. Reading: Thrive, 2012. https://www.lumi.org.uk/assets/resources-toolkits/event-and-projects/G4L-Resource-Book.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tuppen J, Burton-Jones J. Cogs clubs: a helpful activity in early dementia. Journal of Dementia Care 2015;23:20–1. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dean J, Silversides K, Crampton J. Evaluation of the Bradford dementia friendly communities programme. Jospeh Rowntree Foundation: York, 2015. https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/evaluation-bradford-dementia-friendly-communities-programme [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dean J, Silversides K, Crampton J. Evaluation of the York dementia friendly communities programme. York: Jospeh Rowntree Foundation, 2015. https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/evaluation-york-dementia-friendly-communities-programme [Google Scholar]

- 83.Noimuenwai P. Effectiveness of adult day care programs on health outcomes of Thai family caregivers of persons with dementia (PHD thesis). Kansas: University of Kansas, 2012. https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/bitstream/handle/1808/11440/Noimuenwai_ku_0099D_12475_DATA_1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Google Scholar]