Abstract

Objectives

Hyper-inflammation caused by COVID-19 may be mediated by mast cell activation (MCA) which has also been hypothesized to cause Long-COVID (LC) symptoms. We determined prevalence/severity of MCA symptoms in LC.

Methods

Adults in LC-focused Facebook support groups were recruited for online assessment of symptoms before and after COVID-19. Questions included presence and severity of known MCA and LC symptoms and validated assessments of fatigue and quality of life. General population controls and mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) patients were recruited for comparison if they were ≥18 years of age and never had overt COVID-19 symptoms.

Results

There were 136 LC subjects (89.7% females, age 46.9 ±12.9 years), 136 controls (65.4% females, age 49.2 ±15.5), and 80 MCAS patients (85.0% females, age 47.7 ±16.4). Pre-COVID-19 LC subjects and controls had virtually identical MCA symptom and severity analysis. Post-COVID-19 LC subjects and MCAS patients prior to treatment had virtually identical MCA symptom and severity analysis.

Conclusions

MCA symptoms were increased in LC and mimicked the symptoms and severity reported by patients who have MCAS. Increased activation of aberrant mast cells induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection by various mechanisms may underlie part of the pathophysiology of LC, possibly suggesting routes to effective therapy.

Keywords: COVID-19, Long-COVID, mast cell activation, fatigue

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence intervals; MC, mast cell; MCA, mast cell activation; MCs, mast cells; MCAS, mast cell activation syndrome; MCMRS, mast cell mediator release syndrome; N, number; NS, not significant; OR, odds ratio; SD, standard deviation

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has spread throughout the world, with calamitous outcomes for some of those acutely infected and for those who struggle with Long-COVID (LC), also known as Long-Haul COVID and post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (Yong, 2021). Several COVID-19 outcome studies have determined that long-standing, often disabling symptoms are common (Davis et al., 2021, FAIR Health White Paper, 2021, Yong, 2021). The largest studies determined that LC symptoms occurred in: 1) 23.2% overall, and in 50% of those who were hospitalized, in 1.9 million Americans; (FAIR Health White Paper, 2021) 2) 44.2% in 1142 Spaniards; (Fernández-de-Las-Peñas et al., 2021) and 3) 47.1% of 2649 Russians (Munblit et al., 2021). LC has been described as “a mysterious mix of symptoms with no clear pattern” by one expert from The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Stulpin, 2021).

The hyper-inflammatory responses seen in acute COVID-19 infection and in LC have been hypothesized to be mediated in part by mast cell activation (MCA) (Kritas et al., 2020, Theoharides and Conti, 2020, Theoharides, 2021). We hypothesized that baseline/pre-existing mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS, whether clinically recognized prior to COVID-19 infection or not) might explain hyper-inflammatory responses in acute COVID-19 infection and LC (Afrin et al., 2020a). In MCAS, unregulated release of chemical mediators produces a remarkable multitude of symptoms, many of which are suffered by LC patients (Afrin et al., 2017 Mar, Afrin et al., 2016a, Afrin et al., 2020, Afrin et al., 2016b). First reported in 2007, MCAS is a multifactorial, usually somatically polygenic chronic multisystem disorder with inflammatory and allergic themes and has an estimated prevalence of 17% (Afrin et al., 2020b, Molderings et al., 2007, Molderings et al., 2013). Patients with MCAS often remain undiagnosed and symptomatic for decades (Afrin et al., 2017). The natural history of MCAS not uncommonly sees significant escalation of its baseline level of dysfunctional mast cell behavior, for long or indefinite periods, shortly (days to a few months) following major physical or psychological stressors, possibly due to induction of additional somatic mutations by stressor-induced cytokine storms (Afrin et al., 2020b).

We examined the prevalence and severity of MCA symptoms in LC.

Methods

The study was approved by the Missouri Baptist Medical Center Investigational Review Board in St. Louis, Missouri. Data collection started in October 2020 and ended May 2021. LC-focused Facebook group organizers were contacted to allow us to advertise an online study on their website promoting an investigation of symptoms present before and after COVID-19 infection. No other descriptors were provided that might bias recruitment. Questions included presence/severity of known symptoms of MCA (Afrin et al., 2017) and LC symptoms (Davis et al., 2021, FAIR Health White Paper, 2021, Yong, 2021) and validated assessments of fatigue and quality of life (QOL) (Balestroni and Bertolotti, 2012, De Vries et al., 2003, Hendriks et al., 2018). The fatigue assessments scale (FAS) was calculated from a 10-item questionnaire with 5 questions for physical fatigue and 5 questions for mental fatigue. These ten FAS questions were ranked from 1 to 5: scores 10 to 21: no fatigue; scores 22 to 34: substantial fatigue; and scores 35 to 50: extreme fatigue. The self-rated overall general health scores or QOL scores were ranked on a scale from 0 to 100 where 0 was the worst imaginable health and 100 was the best imaginable health. The LC subjects filled out their pre-COVID-19 questionnaire by recall; at the same time, they filled out their identical post-COVID-19 questionnaire. The MCAS patients were asked to answer the questionnaire by recall of their original symptoms and severity prior to treatment. The questions in the control and MCAS patient questionnaires were identical to those for the COVID-19 patients. The LC group filled out the two questionnaires which were titled: 1) BEFORE THE COVID INFECTION QUESTIONS and 2) AFTER THE COVID INFECTION QUESTIONS (Appendix 1A and 1B). In this article, we designate the Long-COVID participants in the following manner: 1) pre-COVID-LC participants refers to the LC groups’ characteristics and recall of symptoms prior to the acute infection with COVID-19; and 2) post-COVID-LC participants refers to the LC groups’ current characteristics and symptoms in the LC state.

The general population control group was composed of employees and their spouses from the Missouri Baptist Medical Center and the offices of the lead investigator (LBW). The MCAS patients were diagnosed in the last two years by the lead investigator and consented to filling out the questionnaire. The controls and the MCAS patients never had symptoms of an acute COVID-19 infection. The consent for the control group stated that they could volunteer even if they had chronic symptoms, conditions, or diseases. In this manner we did not exclude MCA symptoms in this group. The only other exclusion criteria for all groups were age <18 and current pregnancy (or pregnancy during COVID-19). General population control group was recruited through an Intranet posting and handouts advertising the study (Appendix 2). The MCAS patients diagnosed in the last two years by the lead investigator were mailed a cover letter explaining the study, and the consent form and questionnaires were enclosed in the packet (Appendix 3). The IRB committee gave their permission for these activities.

The diagnosis of MCAS in the MCAS patient group was based on the following Consensus-2 diagnostic criteria, i.e., typical symptoms of MCA in 5 or more organ systems plus both of the following criteria: at least one or more elevated mast cell (MC) mediator(s) and clinical improvement with MC-directed therapy (Afrin et al., 2020b). If intestinal biopsies had been performed in the work-up, the MC density had to be ≥20 per high power field (HPF). We modified these Consensus-2 criteria to require 5 systems in place of the previous 2 or more systems in order to reduce potential overdiagnosis of MCAS. The MC mediator measurements included: 1) plasma prostaglandin D2, histamine, and heparin; 2) serum tryptase and chromogranin A; and 3) 24-hour urine prostaglandin 11-β-PGF2α, N-methylhistamine, and leukotriene E4. To help confirm a clinical diagnosis and the severity of MCA, the latest version of the mast cell mediator release syndrome (MCMRS) score was employed, which includes symptoms and severity scores of symptoms seen in MCA disorders (Appendix 4) (Molderings et al., 2006, Afrin et al, 2016a, Theoharides et al, 2019, Weinstock et al., 2021, Weinstock et al., 2020). The MCMRS score also includes points for abnormal laboratory, radiographic, and biopsy findings, but these were not measured in the LC or general control group subjects. A score of ≥14 is consistent with a MC mediator release syndrome which is found in MCAS, mastocytosis, MC leukemia, and other disorders of MC activation (Appendix 4). The final requirement to diagnose MCAS was to exclude other appropriate disorders in the differential diagnosis.

The questions in the MCMRS were used to construct the questionnaire that was administered to all 3 groups in the study. Additional questions were added to this that assessed known LC symptoms, FAS, and QOL (Appendix 1A and 1B). The MCMRS symptoms were assessed for LC participants and controls, but laboratory and biopsy findings were not measured. The MCMRS questionnaire was used in all subjects in three ways: total number of MCMRS symptoms, cumulative MCMRS severity score which was the total of all symptom severity scores, and MCMRS system count which was the total number of body systems that were affected. The total number of MC and LC symptoms was also tabulated.

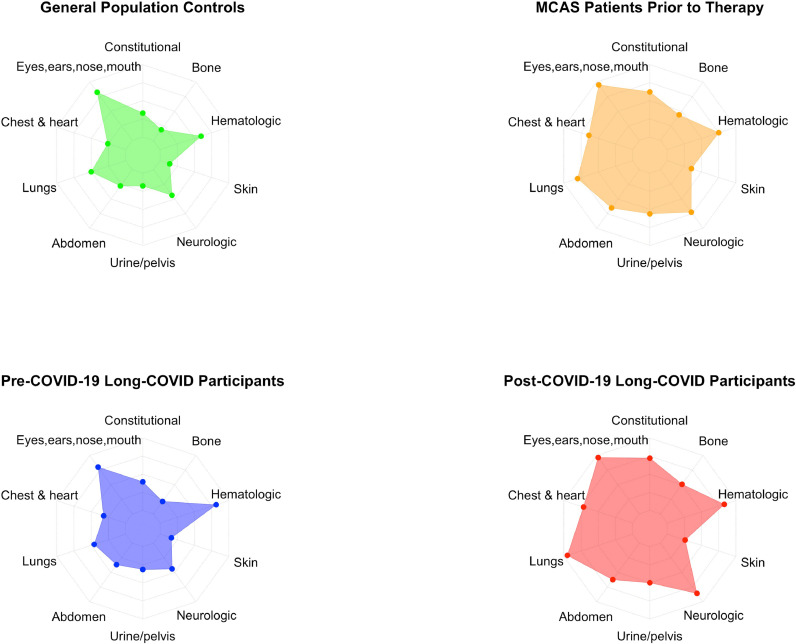

The primary aims were to determine whether prevalence and severity of MCA symptoms in LC were: 1) starting from a baseline similar to healthy controls; 2) significantly higher after COVID-19; and 3) ultimately reaching a level that resembled MCAS patients. After scores were calculated for the MCMRS, each score and symptom underwent three analyses. First, independent samples t-tests or chi-square tests of independence compared LC group's pre-COVID-19 mean scores or symptom prevalence to those of controls. Second, paired samples t-tests or McNemar's tests were used to determine whether the LC group's mean scores or symptom prevalence were significantly higher after COVID-19. Third, independent samples t-tests or chi-square tests were again used to compare post-COVID scores/prevalence to those of MCAS patients prior to MCAS treatment. A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Finally, a spider web plot was created to better display mean MCMRS scores, with each spoke representing a system sub-score (e.g., lungs, heart, skin, etc.). The system sub-scores were normalized on a scale from 0 to 100%, to make each spoke the same length despite different maximum point values. Four spider web plots representing mean MCMRS scores were created, one each for general population controls, MCAS patients, pre-COVID-19 LC, and post-COVID-19 LC.

All groups were queried as to a variety of medications and supplements. The LC group was also asked about medications and supplements used after COVID-19 infection. Medicines and supplements included: 1) those which could specifically affect the severity of acute COVID-19 (angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, carvedilol, and hydrochloroquine, five additional immune modulators and ten different biological agents); and 2) those that could reduce symptoms of MCA, MCAS, and/or COVID-19 (all anti-histamines including H2 blockers, aspirin, benzodiazepines, montelukast, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, steroids, and vitamins C and D). Multivariant analysis was performed to determine if any clinical characteristic, medicine, or supplement altered the prevalence or severity of MCA symptoms in LC.

Results

As shown in Table 1 , study participants included 136 LC participants: 89.7% females, mean age 46.9 ±12.9 years, mean BMI 28.2 ±8.4 kg/m2. The 136 controls were 65.4% females, age 49.2 ±15.5, BMI 25.5 ±4.6. The 80 MCAS patients were 85% females, age 47.7 ±16.4, BMI 25.9 ±6.7. There were no significant differences between groups in age [F(2, 349)=.84, p=0.43] or proportion of Caucasian/White participants [X2(2, N=352)=4.2, p=0.12]. The control group had a lower percentage of females (65.4%) than the LC group (89.7%) or MCAS group [85%; X2(2, N=351)=27.3, p<0.0001]. One-way analysis of variance with Tukey HSD post hoc analysis on BMI showed that LC participants had significantly higher BMI (M=28.2, SD=8.4) than both healthy controls (M=25.5, SD=4.6) and MCAS patients [M=25.9, SD=6.7; F(2,349)=6.04, p=0.0026]. Among LC participants, 110 (80.9%) reported their infection was confirmed by testing, and the remainder stated that their physicians clinically diagnosed their original illness as COVID-19 without testing. Twenty-two (16.2%) LC participants reported they were hospitalized for COVID-19 (19 diagnosed with testing and 2 clinically diagnosed). The use of medications and supplements which can affect MC activation, COVID-19, and/or LC is summarized in Table 2 .

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study participants

| Controls | Long-COVID Participants | MCAS Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size (N) | 136 | 136 | 80 |

| Females, N (%) | 89 (65.4%) | 122 (89.7%) | 68 (85.0%) |

| Males, N (%) | 47 (34.6%) | 14 (10.3%) | 11 (13.8%) |

| Age, Mean (SD) | 49.2 (15.5) | 46.9 (12.9) | 47.7 (16.4) |

| BMI, Mean (SD) | 25.5 (4.6) | 28.2 (8.4) | 25.9 (6.7) |

| Race: (%) | |||

| White | 93.3% | 88.2% | 96.3% |

| Asian | 2.2% | 1.5% | 0% |

| Black | 2.2% | 2.9% | 0% |

| Native American | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.3% |

| Hispanic | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.3% |

| Other | 2.2% | 7.4% | 1.3% |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index, kg/m2; MCAS, mast cell activation syndrome; N, number; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Number and percent of participants taking various medications or dietary supplements. The usage of the remainder of the medications examined was negligible.

| Controls | Pre-COVID-19 Long-COVID Patients | Post-COVID-19 Long-COVID Patients | MCAS Patients with MC Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antihistamines | 38 (27.5%) | 49 (36.0%) | 77 (56.6%)C | 56 (70.0%) |

| Antidepressants | 27 (19.6%) | 24 (17.6%) | 24 (17.6%) | 19 (23.7%) |

| Aspirin and NSAIDS | 54 (39.1%) | 57 (41.9%) | 80 (58.8%)C | 23 (28.8%)D |

| ImmunosuppressantsA | 4 (2.9%) | 10 (7.4%) | 40 (29.4%)C | 7 (8.7%)D |

| Montelukast | 4 (2.9%) | 13 (9.6%)B | 14 (10.3%) | 13 (16.2%) |

| Vitamin C | 41 (29.7%) | 54 (39.7%) | 89 (65.4%)C | 50 (62.5%) |

| Vitamin D | 66 (47.8%) | 70 (51.5%) | 98 (72.1%)C | 51 (63.7%) |

| Melatonin | 15 (10.9%) | 20 (14.7%) | 50 (36.8%) | 9 (11.2%) D |

Immunosuppressants included hydrochloroquine, five additional immune modulators and ten different biological agents.

Significantly different from controls.

Significantly different from pre-COVID Long-COVID.

Significantly different from post-COVID Long-COVID.

Work-up of the MCAS patients showed a mean of 1.4 abnormal mediators per patient: prostaglandin D2 (37.5%), histamine (33.8%), chromogranin (33.8%), leukotriene E4 (11.8%), N-methylhistamine (8.8%), and 2,3-dinor-11-beta-prostaglandin F2 alpha (6.3%). The majority had gastrointestinal symptoms which is characteristic for MCAS patients. The prior diagnostic studies in the 80 patients had included the following: upper endoscopy (100%), colonoscopy (96.3%), abdominal computerized tomography (65.0%), abdominal ultrasound (45.0%), gastric emptying study (20%), video capsule endoscopy (11%), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (6.3%), and cholecystokinin-stimulated hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scans (6.3%). With this work-up and a careful history and physical examination, appropriate differential diagnoses were excluded.

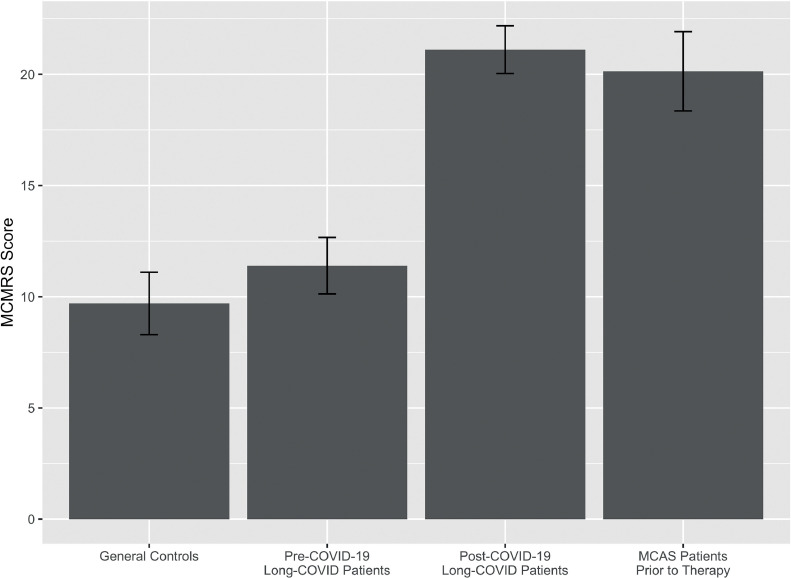

MCMRS scores were calculated for each participant and ranged from 0 to 34, with means shown in Figure 1 and Table 3 . Mean MCMRS scores for controls (9.7, SD 8.3) and pre-COVID-19 LC (mean 11.4, SD 7.5) did not significantly differ [t(267.3)=-1.8, p=0.08]. Scores of LC participants increased significantly to 21.1 (SD 6.3) after COVID-19 [t(135)=-6.1, p=0.0001]. Post-COVID-19 scores did not significantly differ from those of MCAS patients prior to MCAS treatment [mean 20.1, SD 8.0; t(136.9)=-0.9, p=0.4]. Mean MCMRS scores were translated into spider web plots, with each spoke representing the mean score of symptoms affecting a different system (i.e., skin, abdomen, neurologic, etc.). Since each system had a different maximum possible score, they were normalized on a 0-100% scale to make each spoke the same length. The resulting MCMRS spider web plots are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 1.

Mean mast cell mediator release syndrome scores for each group, with whiskers showing 95% confidence intervals.

Table 3.

Mean (SD) mast cell mediator release syndrome scores (total score, cumulative severity, and system count), combined mast cell activation and Long-COVID symptom count, fatigue, and quality of life scores.

| Score, mean (SD) | Controls | Pre-COVID-19 Long-COVID Participants | Post-COVID-19 Long-COVID Participants | MCAS Patients Rating Prior to Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCMRS | ||||

| Score | 9.7 (8.3) | 11.4 (7.5) | 21.1 (6.3)B | 20.1 (8.0) |

| MCMRS cumulative severity | 47.9 (66.6) | 47.2 (43.0) | 154.1 (67.9)B | 161.0 (94.3) |

| MCMRS system count | 5.3 (2.8) | 6.1 (2.3)A | 8.3 (1.4)B | 8.0 (2.1) |

| MC activation and LC symptom count | 10.2 (8.6) | 11.6 (7.7) | 22.0 (6.6)B | 20.4 (8.4) |

| Fatigue assessment scale score | 18.2 (7.7) | 16.6 (6.4) | 34.5 (10.7)B | 31.2 (11.8) |

| Quality of life score | 75.4 (20.2) | 75.6 (16.6) | 40.5 (21.7)B | 56.6 (21.1)C |

Significantly different from controls.

Significantly different from pre-COVID-19 Long-COVID.

Significantly different from post-COVID-19 Long-COVID.

Abbreviations: LC, Long-COVID; MC, mast cell; MCMRS, mast cell mediator release syndrome; MCAS, mast cell activation syndrome; N, number; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 3.

Spider web plots of mean mast cell mediator release syndrome scores.

The MCMRS symptom count ranged from 0 to 35 among participants. As shown in Table 3, mean pre-COVID-19 symptom count (11.6, SD 7.7) was not significantly different from that of controls [10.2, SD 8.6; t(267.1.0)=-1.5, p=0.1]. Mean symptom count significantly increased after COVID to 22.0 [SD 6.6; t(135)=-16.5, p<0.0001]. This mean count did not significantly differ from that of MCAS patients prior to MCAS treatment [20.4, SD 8.4; t(137.4)=-1.4, p=0.2].

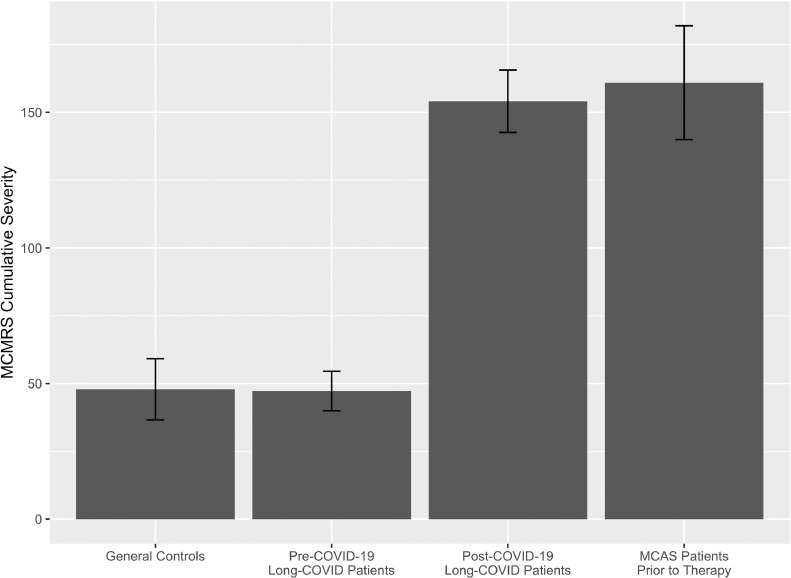

To further investigate potential similarities between post-COVID-19 symptoms and MCAS symptoms, the MCMRS cumulative severity score was calculated. Scores ranged from 0 to 466 among participants. As shown in Figure 2 and Table 3, mean pre-COVID-19 scores (47.2, SD 43.0) were not significantly different from those of controls [47.9, SD 66.6; t(231.0)=0.1, p=0.9]. The mean cumulative severity scores significantly increased after COVID-19 [154.1, SD 67.9; t(135)=-19.6, p<0.0001]. This severity did not significantly differ from the severity scores of MCAS patients prior to MCAS treatment [161.0, SD 94.3; t(127.6)=0.6, p=0.6].

Figure 2.

Mean mast cell mediator release syndrome cumulative severity for each group, with whiskers showing 95% confidence intervals.

Symptoms in the MCMRS were attributed to ten different bodily systems (lungs, skin, urinary/pelvic, etc.), and each participant's total number of affected systems was counted. Scores ranged from 0 to 10 among participants. As shown in Table 3, mean pre-COVID-19-infection system count (6.1, SD 2.3) in LC participants was significantly higher than that of controls [5.3, SD 2.8; t(261.2)=-2.5, p=0.01]. Mean system count significantly increased after COVID-19 infection to 8.3 [SD 1.4; t(135)=-12.3, p<0.0001]. This mean count after COVID-19 infection did not significantly differ from that of MCAS patients [8.0, SD 2.1; t(121.9)=-1.1, p=0.3].

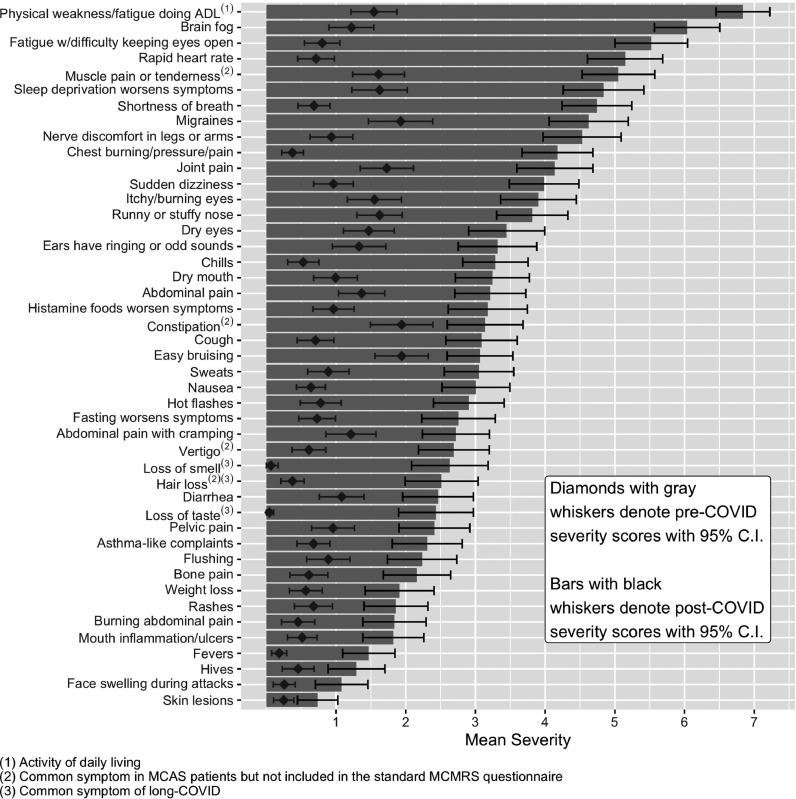

Individual symptoms - from the MCMRS and other common symptoms of MC activation or LC - were compared among the four groups. Symptom severity ratings ranged from 0 (not present) to 10 (most severe imaginable). For each of the 51 symptoms queried for severity, mean scores for pre-COVID-19 LC participants were first compared to those of controls using independent samples t-tests in order to determine whether baseline symptoms recalled by LC participants differed from those of controls. The first two columns of Table 4 show that baseline symptoms were not significantly different between pre-COVID-19 LC and controls for 48 of the 51 symptoms measured. There were significant differences for three symptoms: controls had more chest burning/pressure/pain, more brain fog, and less constipation than pre-COVID-19 LC participants.

Table 4.

Mean (SD) symptom severity with a range of 0 to 10 in the three groups of participants.

| Symptoms | Controls | Pre-COVID-19 Long-COVID Patients | Post-COVID-19 Long-COVID Patients | MCAS Patients Rating Prior to Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical weakness doing ADL | 1.3 (2.1) | 1.5 (1.9) | 6.8 (2.3)B | 5.7 (3.1)C |

| Brain fog | 1.9 (2.5) | 1.2 (1.9)A | 6.0 (2.8)B | 5.2 (3.6) |

| Fatigue attacks with difficulty keeping eyes open | 1.0 (1.8) | 0.8 (1.5) | 5.5 (3.1)B | 4.4 (3.6)C |

| Rapid heart rate | 1.2 (2.2) | 0.7 (1.6) | 5.1 (3.2)B | 4.3 (3.2) |

| Muscle pain or tenderness | 1.7 (2.4) | 1.6 (2.2) | 5.0 (3.1) B | 4.0 (3.7) C |

| Sleep deprivation worsens symptoms | 1.8 (2.5) | 1.6 (2.4) | 4.8 (3.4)B | 4.4 (4.1) |

| Shortness of breath | 0.8 (1.9) | 0.7 (1.3) | 4.7 (2.9)B | 4.0 (3.3) |

| Migraines | 1.5 (2.8) | 1.9 (2.7) | 4.6 (3.3)B | 4.7 (4.0) |

| Nerve discomfort in legs or arms | 1.4 (2.6) | 0.9 (1.8) | 4.5 (3.3)B | 4.7 (3.6) |

| Chest burning, pressure, or pain | 0.8 (2.0) | 0.4 (0.9)A | 4.2 (3.0)B | 3.3 (3.3)C |

| Joint pain | 2.1 (2.8) | 1.7 (2.3) | 4.1 (3.2)B | 3.8 (3.6) |

| Sudden dizziness | 1.2 (2.3) | 1.0 (1.7) | 4.0 (2.9)B | 4.3 (3.7) |

| Itching or burning eyes | 1.6 (2.4) | 1.6 (2.3) | 3.9 (3.2)B | 4.2 (3.4) |

| Runny or stuffy nose | 2.0 (2.4) | 1.6 (1.9) | 3.8 (3.0)B | 4.3 (3.3) |

| Dry eyes | 1.4 (2.2) | 1.5 (2.1) | 3.4 (3.2)B | 2.6 (3.5) |

| Ears have ringing or odd sounds | 1.5 (2.4) | 1.3 (2.3) | 3.3 (3.3)B | 3.9 (3.7) |

| Chills | 0.8 (1.9) | 0.5 (1.3) | 3.3 (2.8)B | 2.7 (3.3) |

| Dry mouth | 0.8 (2.0) | 1.0 (1.8) | 3.2 (3.1)B | 2.4 (3.6) |

| Abdominal pain | 1.5 (2.3) | 1.4 (1.9) | 3.2 (3.0)B | 4.9 (3.5)C |

| Histamine foods worsen symptoms | 1.1 (2.1) | 1.0 (1.7) | 3.2 (3.3)B | 5.4 (3.6)C |

| ConstipationE | 1.1 (2.2) | 1.9 (2.7)A | 3.1 (3.2)B | 3.2 (3.8) |

| Cough | 1.0 (1.9) | 0.7 (1.5) | 3.1 (3.0)B | 1.9 (2.6)C |

| Easy bruising | 1.7 (2.4) | 1.9 (2.3) | 3.1 (2.8)B | 3.4 (3.1) |

| Sweats | 0.7 (1.7) | 0.9 (1.7) | 3.0 (2.9)B | 2.0 (3.1)C |

| Nausea | 1.0 (2.2) | 0.6 (1.2) | 3.0 (2.9)B | 4.6 (3.7)C |

| Hot flashes | 0.7 (2.0) | 0.8 (1.7) | 2.9 (3.0)B | 3.5 (3.7) |

| Fasting worsens symptoms | 0.8 (1.8) | 0.7 (1.6) | 2.8 (3.1)B | 3.4 (4.0) |

| Abdominal pain with cramping | 1.3 (2.4) | 1.2 (2.1) | 2.7 (2.8)B | 4.8 (3.6)C |

| VertigoE | 0.8 (1.8) | 0.6 (1.4) | 2.7 (3.0)B | 2.1 (3.3) |

| Loss of smellF | 0.0 (0.3) | 0.1 (0.6) | 2.6 (3.2)B | 0.4 (1.4)C |

| Loss of hairE,F | 0.4 (1.3) | 0.4 (1.0) | 2.5 (3.1)B | 1.3 (2.6)C |

| Diarrhea | 1.0 (2.2) | 1.1 (1.9) | 2.5 (3.0)B | 4.2 (3.7)C |

| Loss of tasteF | 0.0 (0.3) | 0.0 (0.4) | 2.4 (3.2)B | 0.3 (1.3)C |

| Pelvic Pain | 0.8 (2.0) | 1.0 (1.8) | 2.4 (3.0)B | 3.8 (3.9)C |

| Wheezing | 0.7 (1.6) | 0.7 (1.4) | 2.3 (3.0)B | 1.9 (2.9) |

| Flushing | 0.6 (1.4) | 0.9 (1.8) | 2.2 (2.9)B | 3.8 (3.7)C |

| Bone pain | 0.6 (1.5) | 0.6 (1.6) | 2.2 (2.8)B | 2.9 (3.6) |

| Weight loss | 0.6 (1.7) | 0.6 (1.4) | 1.9 (2.9)B | 1.8 (3.0) |

| Heavy menstrual bleeding | 1.1 (2.3) | 1.8 (2.7) | 2.1 (3.2) | 2.3 (3.5 |

| Rashes | 0.5 (1.4) | 0.7 (1.0) | 1.9 (2.7)B | 2.2 (2.9) |

| Abdominal pain with burning | 0.5 (1.4) | 0.5 (1.4) | 1.8 (2.7)B | 2.2 (3.6) |

| Mouth inflammation or ulcers | 0.6 (1.8) | 0.5 (1.3) | 1.8 (2.6)B | 2.9 (3.4)C |

| Hemangiomas | 0.8 (1.8) | 1.0 (1.8) | 1.5 (2.3)B | 1.9 (3.0) |

| Fever | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.2 (0.6) | 1.5 (2.2)B | 0.6 (1.8)C |

| Hives | 0.5 (1.5) | 0.5 (1.3) | 1.3 (2.4)B | 2.9 (3.5)C |

| Face swelling during attacks | 0.2 (.8) | 0.3 (.9) | 1.1 (2.2)B | 1.6 (2.9) |

| Skin lesions | 0.2 (1.0) | 0.2 (0.9) | 0.7 (1.7)B | 1.4 (2.7) |

| Anal itching during attacks | 0.3 (1.5) | 0.3 (1.6) | 0.6 (1.6)B | 1.9 (3.1)C |

| Skin nodules | 0.2 (0.7) | 0.2 (0.9) | 0.6 (1.6)B | 1.3 (2.4)C |

| Unusual nasal bleeding | 0.4 (1.3) | 0.3 (1.0) | 0.6 (1.5)B | 0.9 (2.1) |

| Seizures | 0.1 (0.9) | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.2 (1.1) |

Pre-COVID-19 Long-COVID mean is significantly different from controls.

Post-COVID-19 Long-COVID mean is significantly different from pre-COVID-19 Long-COVID.

MCAS patients’ mean is significantly different from post-COVID-19 Long-COVID.

Common symptom in MCAS patients but not included in the standard MCMRS questionnaire.

Common symptom in Long-COVID.

Abbreviations: ADL, activity of daily living; MCAS, mast cell activation syndrome; MCMRS, mast cell mediator release syndrome.

Next, repeated measures t-tests determined whether mean symptom severity scores increased in after COVID-19, as compared to before COVID-19. As shown in Table 4, mean severity increased significantly for every symptom measured except seizures.

To determine whether post-COVID-19 symptom severity resembled that reported by MCAS patients prior to MCAS treatment, independent samples t-tests were performed for each symptom. As shown in the last two columns of Table 4, there were significant differences between post-COVID-19 LC participants and MCAS patients prior to MCAS treatment for 21 of the 51 symptoms: MCAS patients prior to MCAS treatment reported significantly higher severity of abdominal pain, high-histamine-content foods making symptoms worse, nausea, abdominal pain with cramping, diarrhea, pelvic pain, mouth inflammation/ulcers, flushing, anal itching during attacks, hives, and skin nodules. Post-COVID-19 LC participants reported significantly higher severity of physical weakness doing activities of daily living, severe fatigue attacks that makes it difficult to keep eyes open, muscle pain or tenderness, chest burning/pressure/pain, cough, sweats, loss of smell, hair loss, and loss of taste. For the other 30 symptoms, there were no significant differences between symptom severity reported by post-COVID-19 LC and MCAS patients prior to MCAS treatment.

Fatigue scores were calculated for each participant, with means shown in Table 3. Pre-COVID-19 LC participant scores (mean 16.6, SD 6.4) were not significantly different than those of controls [mean 18.2, SD 7.7; t(261.6)=1.8, p=0.08] but escalated significantly post-COVID-19 in LC participants [mean 34.5, SD 10.7; t(135)=-19.8, p<0.0001] to resemble those of MCAS patients prior to MCAS treatment (mean 31.2, SD 11.8; t(113.5)=-1.9, p=0.06].

As shown in Table 3 and Figure 4 mean self-rated overall general health scores or quality of life scores were also not significantly different between pre-COVID-19 LC participants (mean 75.6, SD 16.6) and controls [mean 75.4, SD 20.2; t(260.4)=-0.1, p=0.95). In post-COVID-19 LC participants, these mean scores dropped significantly to 40.5 (SD= 21.7; t(135)=16.5, p<0.0001). In post-COVID-19 LC participants, these scores were significantly lower than those of MCAS patients prior to MCAS treatment (mean 56.6, SD 21.1, t(118.6)=4.9, p=<0.0001).

Figure 4.

Changes in Long-COVID participants mean symptom severity scores before and after COVID-19 (all are statistically different; p<0.05).

Discussion

The occurrence of MCA symptoms in LC patients has previously not been examined in a detailed manner. In the present study, there was a high prevalence of MCA symptoms in LC patients prior to MCAS treatment. The symptom data and spider web plots illustrated that LC patients’ symptoms are virtually identical to those experienced by MCAS patients. These results support, but do not provide definitive proof of, our earlier hypothesis that LC might often arise out of a SARS-CoV-2-driven provocation of primary or secondary MCAS (Afrin et al., 2020a). Theories to explain promotion of MCA in LC include: 1) complex interactions of stressor-induced cytokine storms with epigenetic-variant-induced states of genomic fragility to induce additional somatic mutations in stem cells or other mast cell progenitors; (Afrin et al., 2020a) 2) cytokine or SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus activation of mast cells and microglia; (Theoharides and Conti, 2020) 3) dysregulation of genes by SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus leading to loss of genetic regulation of mast cells; (Maxwell et al., 2021) 4) development of autoantibodies which react with immunoglobulin receptors on mast cells; (Liu et al., 2021, Vojdani et al., 2021) and 5) increase in Toll-like receptor activity by the coronavirus (Mukherjee et al., 2021).

When major stressors drive escalations of MCAS, those escalations tend to be sustained for long/indefinite periods and sometimes clearly are permanent. This is likely due to complex interactions between epigenetic and genetic aberrancies and the stressor's induced cytokine storm, inducing additional mutations in the stem cells giving rise to the aberrant mast cells (Altmüller et al., 2017; Haenisch et al., 2012; Haenisch et al., 2014; Molderings et al., 2007, Molderings et al., 2010, Molderings, 2015, Molderings, 2016). In a similar fashion, post-infectious chronic multisystem inflammatory syndromes are suspected to be rooted in initiation of mutations of normal stem cells leading to aberrant controller genes (e.g., Epstein-Barr virus and tick-borne infections) (Afrin et al., 2016a, Kempuraj et al., 2020, Talkington and Nickell, 1999).

Potential limitations of our study include gender recruitment imbalance. LC females outnumbered LC males. This is likely due to the makeup of the LC Facebook group and/or gender preference for recruitment. In a concurrent study to ours with a similar design/methodology, 78.9% of 3762 LC Internet responders were women (Davis et al., 2021). In the largest study to date, LC was more common in women (FAIR Health White Paper, 2021). With respect to gender imbalance in the general population control, it is likely that more women than men were recruited because of gender imbalance of employees at the hospital and endoscopy center and these individuals may not have recruited male spouses. In our studies and clinical practices, we have observed that MCAS patients have a significantly higher percentage of women (Afrin et al., 2017, Molderings et al., 2013). We recognize that members of most social media groups are largely self-selected and do not constitute a randomly selected population and may not necessarily represent the general population of patients who have LC. Subjects who join a medical support group might be more ill than other patients. Yet, examination of such groups may provide preliminary insights which may provide useful guidance for further research. The fact that the MCAS patients were diagnosed at a gastroenterology clinic that subspecializes in MCAS could have biased the comparison group by having increased severity of gastrointestinal symptoms. Nonetheless, MCAS patients often present to gastroenterologists as well as many other specialists (e.g., allergists, cardiologists, neurologists, and urologists) (Weinstock et al., 2021). Retrospective data entered by the MCAS patients was not ideal methodology. Their symptoms, however, were experienced within a 2-year period of the study and MCAS symptoms often are present for decades. Another potential problem is that the LC group completed their pre-COVID-19 questionnaire by recall, and thus this part of the study was retrospective. This was a limitation of the study design, yet the spider symptom/severity plots at baseline were remarkably similar to the general population control group, likely negating this issue.

In this study, symptoms suggesting new MCA were significantly increased in LC. Although the symptoms that LC share with MCAS patients are similar, we are not equating LC with a mutual diagnosis of MCAS since diagnosis of MCAS compliant with published criteria requires testing not pursued in the LC participants. Furthermore, MCA symptoms can be present purely due to normal reactivity to various stimuli by normal MCs and may fade as the MC activation-driving stimulus resolves. At present, detection of somatic mutations in mast cells is not available in any clinical laboratories and thus it is not possible to prove whether any given case of LC is primary vs. secondary MCAS. A number of small trials have found benefit from MC-stabilizing drugs in acute COVID-19 and LC (Kazama, 2020). We have seen improvement in our LC patients in our clinics (LBW, LBA) using a varying combination of MC-directed therapies including antihistamines, cromolyn, flavonoids (quercetin and lutein), low dose naltrexone, montelukast, and vitamins C and D (Barré et al., 2020, Choubey et al., 2020, Colunga Biancatelli et al., 2020, Freedberg et al., 2020, Gigante et al., 2020, Hogan et al., 2020, Janowitz et al., 2020, Mather et al., 2020, Patterson et al., 2021, Pinheiro et al., 2021, Theoharides, 2020, Theoharides et al, 2021, Weng et al, 2015). Low dose naltrexone has also been used to treat MCAS and may be effective in Long-COVID, possibly by reducing cytokines from T-cells which activate mast cells and by blocking Toll-like receptors on mast cells and microglia (Mukherjee et al., 2021, Weinstock and Blasingame, 2020).

Conclusion

In this study, MCA symptoms were significantly increased in LC. Uncontrolled, aberrant mast cells may in part underlie the pathophysiology of LC. Inflammation caused by COVID-19 is complicated, and other immune disturbances that have been seen in the acute infection such as excess dysfunction of the macrophage and serotonin release from platelets might or might not play roles in LC (Koupenova and Freedman, 2020, Maxwell et al., 2021, Perricone et al., 2020). Our observations may lead to effective therapy for those suffering from LC. Further studies of LC patients with measurements of MC mediators and clinical trials using MC-directed medications are warranted.

Disclosures

Dr. Weinstock and Dr. Afrin are uncompensated volunteer medical advisors to the startup company MC Sciences, Ltd. Dr. Walters has received research funding from the National Institutes of Health, Xenoport, Arbor, and Mundi Pharma. Mrs. Brook and Ms. Goris have no disclosures. Dr. Molderings is the chief medical officer of the startup company MC Sciences, Ltd.

Potential Conflicts of Interests

Dr. Weinstock and Dr. Afrin are uncompensated volunteer medical advisors to the startup company MC Sciences, Ltd. Dr. Walters has received research funding from the National Institutes of Health, Xenoport, Arbor, and Mundi Pharma. Mrs. Brook and Ms. Goris have no disclosures. Dr. Molderings is the chief medical officer of the startup company MC Sciences, Ltd.

Funding source

Missouri Baptist Healthcare Foundation

Ethical Approval

The study was approved on December 9, 2020 by the Missouri Baptist Medical Center Investigational Review Board in St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

Acknowledgment

We wish to thank Michael Brook, who assisted in statistical analysis and preparation of the figures.

Footnotes

Study design: Dr. Weinstock, Mrs. Brook, Dr. Walters, Mrs. Goris, Dr. Afrin.

Collection and analysis of data: Dr. Weinstock, Mrs. Brook, and Mrs. Goris.

Manuscript writing: Dr. Weinstock, Mrs. Brook, Dr. Walters, and Dr. Afrin wrote the manuscript. Statistics: Mrs. Brook. Revisions and critical review of manuscript: Dr. Walters, Dr. Afrin, Dr. Molderings, Mrs. Brook. Clinical work: performed in St. Louis, MO, USA.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.09.043.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Afrin L.B., Butterfield J.H., Raithel M., Molderings G.J. Often seen, rarely recognized: mast cell activation disease–a guide to diagnosis and therapeutic options. Review article. Ann Med. 2016;48:190–201. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2016.1161231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afrin L.B., Cichocki F., Hoeschen A., Beckman K.B., Gupta K., Nguyen J., et al. Mast cell regulatory gene variants are common in mast cell activation syndrome. Blood. 2016;128(22):4878. doi: 10.1182/blood.V128.22.4878.4878. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Afrin L.B., Self S., Menk J., Lazarchick J. Characterization of mast cell activation syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 2017;353(3):207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.12.013. Mar PMID: 28262205; PMCID: PMC5341697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afrin L.B., Ackerley M.B., Bluestein L.S., Brewer J.H., Brook J.B., Buchanan A.D., et al. Diagnosis of mast cell activation syndrome: a global "consensus-2". Diagnosis (Berl) 2020;8(2):137–152. doi: 10.1515/dx-2020-0005. PMID: 32324159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afrin L.B., Weinstock L.B., Molderings G.J. Covid-19 hyperinflammation and post-Covid-19 illness may be rooted in mast cell activation syndrome. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;100:327–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmüller J., Haenisch B., Kawalia A., Menzen M., Nöthen M.M., Fier H., et al. Mutational profiling in the peripheral blood leukocytes of patients with systemic mast cell activation syndrome using next-generation sequencing. Immunogenetics. 2017;69(6):359–369. doi: 10.1007/s00251-017-0981-y. PMID: 28386644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balestroni G., Bertolotti G. L'EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D): uno strumento per la misura della qualità della vita [EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D): an instrument for measuring quality of life] Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2012;78(3):155–159. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2012.121. PMID: 23614330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barré J., Sabatier J.M., Annweiler C. Montelukast drug may improve COVID-19 prognosis: a review of evidence. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:1344. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.01344. PMID: 33013375; PMCID: PMC7500361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choubey A., Dehury B., Kumar S., Medhi B., Mondal P. Naltrexone a potential therapeutic candidate for COVID-19. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020;15:1–8. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1820379. PMID: 32930058; PMCID: PMC7544934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colunga Biancatelli R.M.L., Berrill M., Catravas J.D., Marik P.E. Quercetin and vitamin C: an experimental, synergistic therapy for the prevention and treatment of SARS-CoV-2 related disease (COVID-19) Front Immunol. 2020;11:1451. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01451. PMID: 32636851; PMCID: PMC7318306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis H.E., Assaf G.S., McCorkell L., Wei H., Low R.J., Re'em Y., et al. Characterizing long Covid in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019. (Last accessed 8/14/21) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries J., Michielsen H.J., Van Heck G.L. Assessment of fatigue among working people: a comparison of six questionnaires. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60(Suppl 1) doi: 10.1136/oem.60.suppl_1.i10. i10-5PMID: 12782741; PMCID: PMC1765720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAIR Health White Paper. A detailed study of patients with long-haul COVID. https://s3.amazonaws.com/media2.fairhealth.org/whitepaper/asset/A%20Detailed%20Study%20of%20Patients%20with%20Long-Haul%20COVID–An%20Analysis%20of%20Private%20Healthcare%20Claims–A%20FAIR%20Health%20White%20Paper.pdf. June 15, 2021. (Last accessed 8/14/21).

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C., Palacios-Ceña D., Gómez-Mayordomo V., Rodríuez-Jiménez J., Palacios-Ceña M., Velasco-Arribas M., et al. Long-term post-COVID symptoms and associated risk factors in previously hospitalized patients: A multicenter study. J Infect. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.04.036. S0163-4453(21)00223-1PMID: 33984399; PMCID: PMC8110627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedberg D.E., Conigliaro J., Wang T.C., Tracey K.J., Callahan M.V., Abrams J.A. Famotidine use is associated with improved clinical outcomes in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: a propensity score matched retrospective cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1129–1131. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.053. PMID: 32446698 PMCID: PMC7242191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigante A., Aquili A., Farinelli L., Caraffa A., Ronconi G., Enrica Gallenga C., et al. Sodium chromo-glycate and palmitoylethanolamide: A possible strategy to treat mast cell-induced lung inflammation in COVID-19. Med Hypotheses. 2020;143 doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109856. PMID: 32460208; PMCID: PMC7236677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenisch B., Nöthen M.M., Molderings G.J. Systemic mast cell activation disease: the role of molecular genetic alterations in pathogenesis, heritability and diagnostics. Immunology. 2012;137(3):197–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2012.03627.x. PMID: 22957768; PMCID: PMC3482677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenisch B., Fröhlich H., Herms S., Molderings G.J. Evidence for contribution of epigenetic mechanisms in the pathogenesis of systemic mast cell activation disease. Immunogenetics. 2014;66(5):287–297. doi: 10.1007/s00251-014-0768-3. PMID: 24622794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks C., Drent M., Elfferich M., De Vries J. The fatigue assessment scale: quality and availability in sarcoidosis and other diseases. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2018;24(5):495–503. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000496. PMID: 29889115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan R.B., II, Hogan R.B., III, Cannon T., Rappai M., Studdard S., Paul D., et al. Dual-histamine receptor blockade with cetirizine - famotidine reduces pulmonary symptoms in COVID-19 patients. Pulm Pharm Ther. 2020;63 doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2020.101942. ISSN 1094-5539PMID: 32871242; PMCID: PMC7455799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janowitz T., Gablenz E., Pattinson D., Wang T.C., Conigliaro J., Tracey K., et al. Famotidine use and quantitative symptom tracking for COVID-19 in non-hospitalised patients: a case series. Gut. 2020;69:1592–1597. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazama I. Stabilizing mast cells by commonly used drugs: a novel therapeutic target to relieve post-COVID syndrome? Drug Discov Ther. 2020;14(5):259–261. doi: 10.5582/ddt.2020.03095. PMID: 33116043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempuraj D., Selvakumar G.P., Ahmed M.E., Raikwar S.P., Thangavel R., Khan A., et al. COVID-19, mast cells, cytokine storm, psychological stress, and neuroinflammation. Neuroscientist. 2020;26(5-6):402–414. doi: 10.1177/1073858420941476. PMID: 32684080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koupenova M., Freedman J.E. Platelets and COVID-19: inflammation, hyperactivation and additional questions. Circ Res. 2020;127(11):1419–1421. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.318218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritas S.K., Ronconi G., Caraffa A., Gallenga C.E., Ross R., Conti P. Mast cells contribute to coronavirus-induced inflammation: new anti-inflammatory strategy. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2020;34(1):9–14. doi: 10.23812/20-editorial-kritas. PMID: 32013309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Sawalha A.H., Qianjin Lu Q. COVID-19 and autoimmune diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2021;33:155–162. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000776. PMID: 33332890; PMCID: PMC7880581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather J.F., Seip R.L., McKay R.G. Impact of famotidine use on clinical outcomes of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(10):1617–1623. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000832. PMID: 32852338; PMCID: PMC7473796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell A.J., Ding J., You Y., Dong Z., Chehade H., Alvero A., et al. Identification of key signaling pathways induced by SARS-CoV2 that underlie thrombosis and vascular injury in COVID-19 patients. J Leukoc Biol. 2021;109:35–47. doi: 10.1002/JLB.4COVR0920-552RR. PMID: 33242368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molderings G.J., Kolck U., Scheurlen C., Brüss M., Frieling T., Raithel M., Homann J. Die systemische Mastzellerkrankung mit gastrointestinal betonter Symptomatik–eine Checkliste als Diagnoseinstrument [Systemic mast cell disease with gastrointestinal symptoms–a diagnostic questionnaire] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2006;131(38):2095–2100. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-951337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molderings G.J., Kolck U.W., Scheurlen C., Brüss M., Homann J., Von Kügelgen I. Multiple novel alterations in Kit tyrosine kinase in patients with gastrointestinally pronounced systemic mast cell activation disorder. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42(9):1045–1053. doi: 10.1080/00365520701245744. PMID: 17710669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molderings G.J., Meis K., Kolck U.W., Homann J., Frieling T. Comparative analysis of mutation of tyrosine kinase kit in mast cells from patients with systemic mast cell activation syndrome and healthy subjects. Immunogenetics. 2010;62(11-12):721–727. doi: 10.1007/s00251-010-0474-8. PMID: 20838788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molderings G.J., Haenisch B., Bogdanow M., Fimmers R., Nöthen M.M. Familial occurrence of systemic mast cell activation disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e76241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076241. PMID: 24098785; PMCID: PMC3787002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molderings G.J. The genetic basis of mast cell activation disease - looking through a glass darkly. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;93(2):75–89. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2014.09.001. PMID: 25305106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molderings G.J. Transgenerational transmission of systemic mast cell activation disease-genetic and epigenetic features. Transl Res. 2016;174:86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2016.01.001. PMID: 26880691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee R., Bhattacharya A., Bojkova D., Mehdipour A.R., Shin D., Khan K.S., et al. Famotidine inhibits Toll-like receptor 3-mediated inflammatory signaling in SARS-CoV2 infection. J Biol Chem. 2021 Jun 29 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100925. PMID: 34214498; PMCID: PMC8241579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munblit D., Bobkov P., Spiridonova E., Shikhaleva A., Gamirova A., Blyuss O., et al. Risk factors for long-term consequences of COVID-19 in hospitalised adults in Moscow using the ISARIC Global follow-up protocol: StopCOVID cohort study. medRxiv 2021.02.17.21251895. doi: 10.1101/2021.02.17.21251895.

- Patterson T., Isales C.M., Fulzele S. Low level of vitamin C and dysregulation of vitamin C transporter might be involved in the severity of COVID-19 Infection. Aging Dis. 2021;12(1):14–26. doi: 10.14336/AD.2020.0918. PMID: 33532123; PMCID: PMC7801272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perricone C., Bartoloni E., Bursi R., Cafaro G., Guidelli G.M., Shoenfeld Y., Gerl R. COVID-19 as part of the hyperferritinemic syndromes: the role of iron depletion therapy. Immunol Res. 2020;68(4):213–224. doi: 10.1007/s12026-020-09145-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro M.M., Fabbri A., Infante M. Cytokine storm modulation in COVID-19: a proposed role for vitamin D and DPP-4 inhibitor combination therapy (VIDPP-4i) Immunotherapy. 2021;13(9):753–765. doi: 10.2217/imt-2020-0349. PMID: 33906375; PMCID: PMC8080872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stulpin C. Long COVID: A ‘mysterious’ syndrome with ‘no clear pattern’ of symptoms. https://www.healio.com/news/infectious-disease/20210713/long-covid-a-mysterious-syndrome-with-no-clear-pattern-of-symptoms. July 21, 2021. (Last accessed 8/14/21).

- Talkington J., Nickell S.P. Borrelia burgdorferi spirochetes induce mast cell activation and cytokine release. Infect Immun. 1999;67(3):1107–1115. doi: 10.1128/IAI.67.3.1107-1115.1999. PMID: 10024550; PMCID: PMC96436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theoharides T.C., Tsilioni I., Ren H. Recent advances in our understanding of mast cell activation - or should it be mast cell mediator disorders? Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019;15(6):639–656. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2019.1596800. Jun Epub 2019 Apr 22. PMID: 30884251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theoharides T.C. COVID-19, pulmonary mast cells, cytokine storms, and beneficial actions of luteolin. Biofactors. 2020;46(3):306–308. doi: 10.1002/biof.1633. PMID: 32339387; PMCID: PMC7267424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theoharides T.C, Conti P. COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome, or is it mast cell activation syndrome? J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2020;34(5):1633–1636. doi: 10.23812/20-EDIT3. PMID: 33023287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theoharides TC, Cholevas C, Polyzoidis K, Politis A. Long-COVID syndrome-associated brain fog and chemofog: Luteolin to the rescue. Biofactors. 2021;47(2):232–241. doi: 10.1002/biof.1726. Mar Epub 2021 Apr 12. PMID: 33847020; PMCID: PMC8250989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theoharides T.C. Potential association of mast cells with coronavirus disease 2019. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126(3):217–218. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.11.003. PMID: 33161155; PMCID: PMC7644430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vojdani A., Vojdani E., Kharrazian D. Reaction of human monoclonal antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 proteins with tissue antigens: implications for autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.617089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng Z, Patel AB, Panagiotidou S, Theoharides TC. The novel flavone tetramethoxyluteolin is a potent inhibitor of human mast cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(4) doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.10.032. Apr 1044-1052.e5Epub 2014 Dec 10. PMID: 25498791; PMCID: PMC4388775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock L.B., Pace L.A., Rezaie A., Afrin L.B., Molderings G.J. Mast cell activation syndrome: a primer for the gastroenterologist. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66(4):965–982. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06264-9. PMID: 32328892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong S.J. Long COVID or post-COVID-19 syndrome: putative pathophysiology, risk factors, and treatments. Infect Dis (Lond) 2021:1–18. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2021.1924397. PMID: 34024217; PMCID: PMC8146298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock L.B., Blasingame K. Low dose naltrexone and gut health. In: Elsegood L., (Ed.) The LDN Book Volume 2. Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing. 2020. p. 35–54.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.