Key Points

Question

Does combining varenicline with the nicotine patch or extending cessation treatment duration increase smoking abstinence compared with the standard length of therapy with varenicline only?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 1251 participants smoking 5 cigarettes/d or more, treatment with varenicline monotherapy for 12 weeks, varenicline plus nicotine patch for 12 weeks, varenicline monotherapy for 24 weeks, and varenicline plus nicotine patch for 24 weeks resulted in 7-day point prevalence abstinence rates at 52 weeks of 25.1%, 23.6%, 24.4%, and 25.1%, respectively. None of the comparisons was statistically significant.

Meaning

These findings do not support the use of combined varenicline plus nicotine patch vs varenicline monotherapy or of 24-week vs 12-week treatment for smoking cessation.

Abstract

Importance

Smoking cessation medications are routinely used in health care. Research suggests that combining varenicline with the nicotine patch, extending the duration of varenicline treatment, or both, may increase cessation effectiveness.

Objective

To compare combinations of varenicline plus the nicotine or placebo patch vs combinations used for either 12 weeks (standard duration) or 24 weeks (extended duration).

Design, Settings, and Participants

Double-blind, 2 × 2 factorial randomized clinical trial conducted from November 11, 2017, to July 9, 2020, at 1 research clinic in Madison, Wisconsin, and at 1 clinic in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Of the 5836 adults asked to participate in the study, 1251 who smoked 5 cigarettes/d or more were randomized.

Interventions

All participants received cessation counseling and were randomized to 1 of 4 medication groups: varenicline monotherapy for 12 weeks (n = 315), varenicline plus nicotine patch for 12 weeks (n = 314), varenicline monotherapy for 24 weeks (n = 311), or varenicline plus nicotine patch for 24 weeks (n = 311).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was carbon monoxide–confirmed self-reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence at 52 weeks.

Results

Among 1251 patients who were randomized (mean [SD] age, 49.1 [11.9] years; 675 [54.0%] women), 751 (60.0%) completed treatment and 881 (70.4%) provided final follow-up. For the primary outcome, there was no significant interaction between the 2 treatment factors of medication type and medication duration (odds ratio [OR], 1.03 [95% CI, 0.91 to 1.17]; P = .66). For patients randomized to 24-week vs 12-week treatment duration, the primary outcome occurred in 24.8% (154/622) vs 24.3% (153/629), respectively (risk difference, −0.4% [95% CI, −5.2% to 4.3%]; OR, 1.01 [95% CI, 0.89 to 1.15]). For patients randomized to varenicline combination therapy vs varenicline monotherapy, the primary outcome occurred in 24.3% (152/625) vs 24.8% (155/626), respectively (risk difference, 0.4% [95% CI, −4.3% to 5.2%]; OR, 0.99 [95% CI, 0.87 to 1.12]). Nausea occurrence ranged from 24.0% to 30.9% and insomnia occurrence ranged from 24.4% to 30.5% across the 4 groups.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among adults smoking 5 cigarettes/d or more, there were no significant differences in 7-day point prevalence abstinence at 52 weeks among those treated with combined varenicline plus nicotine patch therapy vs varenicline monotherapy, or among those treated for 24 weeks vs 12 weeks. These findings do not support the use of combined therapy or of extended treatment duration.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03176784

This randomized clinical trial compares combinations of varenicline plus the nicotine or placebo patch vs combinations used for either 12 weeks (standard duration) or 24 weeks (extended duration) for smoking cessation in adults who smoked 5 cigarettes/d or more.

Introduction

Evidence-based pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation has been shown to be effective in diverse populations of those who smoke,1 and different strategies to enhance the effectiveness of such therapies have been explored.2 Research has supported the effectiveness of combination therapy with varenicline and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) vs varenicline alone. One large study3 reported significant benefit of combination therapy with varenicline and NRT vs varenicline alone. Two smaller studies4,5 did not show a statistically significant benefit with this treatment, but a meta-analysis of the 3 studies showed a statistically significant association with benefit.6 Such evidence led the American Thoracic Society to conditionally recommend varenicline plus nicotine patch combination therapy over varenicline monotherapy for smoking cessation.7 However, most guidelines recommend monotherapy with varenicline, NRT, or bupropion or recommend combination therapy with different types of NRT.8,9

There is also evidence that extending the duration of pharmacotherapy can enhance its effectiveness.10,11,12 However, little research has been done on extended varenicline treatment. Two relapse prevention studies13,14 and a Cochrane meta-analysis15 found that extended treatment with varenicline can increase long-term abstinence rates among individuals who already attained abstinence after prior treatment.

Because it remains uncertain whether combining varenicline with NRT or extending varenicline treatment duration increases smoking cessation rates, this randomized clinical trial was conducted to examine both treatment strategies among individuals expressing an interest in quitting smoking.

Methods

Study Oversight and Recruitment

This research was approved by the University of Wisconsin health sciences institutional review board. The trial protocol appears in Supplement 1. All participants provided written informed consent.

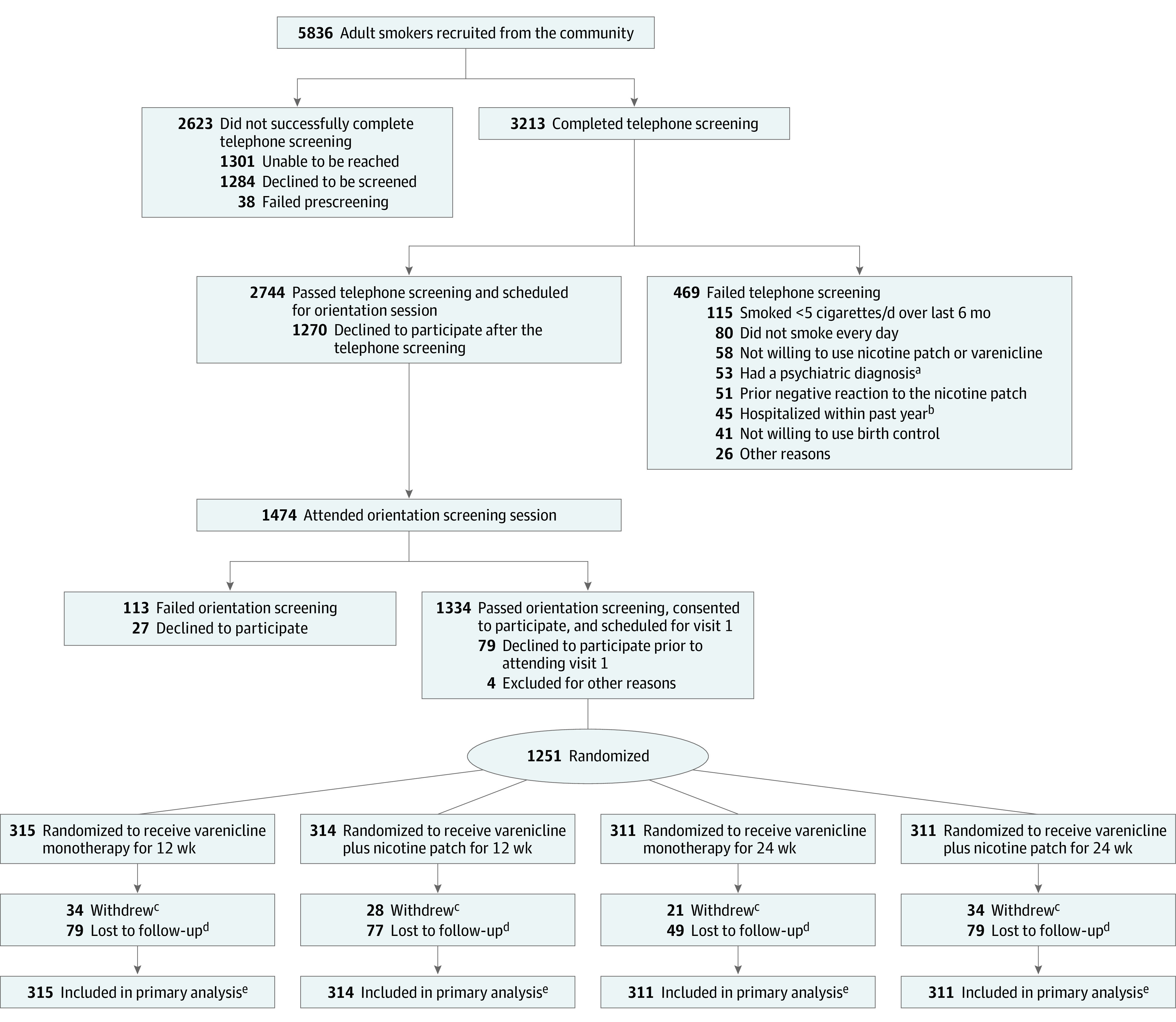

Recruitment occurred via community outreach (eg, social networking sites). The study flow of included and excluded individuals appears in the Figure. Interested respondents were called and screened for initial eligibility. Potentially eligible individuals attended a group orientation conducted by research staff that entailed: final eligibility assessment, consent, baseline assessments, and randomization. Study visits occurred at 2 research clinics, 1 in Madison, Wisconsin, and 1 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Initial enrollment occurred on November 11, 2017, and study completion occurred on July 9, 2020.

Figure. Participant Flow Diagram.

aReceived treatment for schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder within past year.

bFor stroke, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, or diabetes.

cData collected through 52 weeks.

dDid not complete the week 52 telephone assessment. These data include participants who withdrew from the study.

eFor the primary outcome of self-reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence (biochemically confirmed as exhaled carbon monoxide level ≤5 ppm) at 52 weeks after target quit day, the analyses used the full sample randomized to the treatment groups (N = 1251) and assumed that missing observations reflected current smoking.

Individuals were included if they: spoke English; smoked 5 cigarettes/d or more during the last 6 months; had an exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) level of 5 ppm or greater; were aged 18 years or older; expressed a desire to quit smoking; were not currently engaged in smoking cessation treatment; reported no other use of tobacco products (pipe tobacco, cigars, snuff, e-cigarettes, or chewing tobacco) within the past 30 days; had phone access; were willing and able to use both the nicotine patch and varenicline; were able to attend clinic visits for the next 12 months; and were not pregnant and were willing to use an acceptable birth control method. Individuals were excluded if they: were receiving current treatment for psychosis; had suicidal ideation within the past year; had a suicide attempt within the prior 10 years; had severe kidney disease or were receiving dialysis; had been hospitalized for a stroke, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, or uncontrolled diabetes within the past year; had a history of seizure within the past year; were currently taking bupropion, varenicline, or NRT and intended to continue this treatment; had a history of allergic reaction to one of the study medications; and were currently participating in another smoking cessation study.

Randomization

Participants were randomized to 1 of 2 levels of the 2 experimental factors (medication type and medication duration) via a database that used stratified permuted block randomization. SAS Proc Plan version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) was used to stratify by site (Madison or Milwaukee), sex, race (non-White or White), and smoking heaviness (5-15 [low] or ≥16 [high] cigarettes/d) with a fixed block size of 4 based on the 4 unique treatment groups (in random order within each block). The double-blind treatment assignment meant that all participants took pills and wore patches for the same treatment length.

Race is often related to cessation success.16,17,18 Race and ethnicity were assessed via participant self-report to fixed-choice responses. The assessment of race permitted (1) stratification to prevent the chance association of these variables with treatment assignment, (2) use of race as a covariate in multivariable analyses to increase the precision of the estimates for the treatment effects, and (3) use of race as a moderator of the treatment effects.

Interventions

Pharmacotherapy

Study medication was dispensed at visit 1 (week −2) and at visit 2 (the target quit day) and mailed to participants at week 8. The 4 treatment groups created by the 2 × 2 factorial design were: (1) varenicline monotherapy for 12 weeks: active varenicline for week −1 to week 11 and placebo varenicline from week 12 to week 23 (placebo patch from week −2 to week 24); (2) varenicline plus nicotine patch for 12 weeks: active varenicline from week −1 to week 11 and placebo varenicline from week 12 to week 23 plus active nicotine patch from week −2 to week 12 and placebo nicotine patch from week 13 to week 24; (3) varenicline monotherapy for 24 weeks: active varenicline from week −1 to week 23 (placebo patch from week −2 to week 24); and (4) varenicline plus nicotine patch for 24 weeks: active varenicline from week −1 to week 23 plus active nicotine patch from week −2 to week 24.

As in the study by Koegelenberg et al,3 varenicline treatment began 1 week before the target quit day, whereas nicotine patch treatment started 2 weeks before the target quit day. Active varenicline treatment lasted 12 weeks or 24 weeks and nicotine patch treatment lasted 14 weeks or 26 weeks due to the different medication start and stop times. To mask treatment assignment, all participants were given 24 weeks of varenicline pills and 26 weeks of nicotine patches (active and placebo medications). Varenicline treatment started with one 0.5-mg varenicline pill for 3 days, two 0.5-mg pills for 4 days, and two 1-mg pills thereafter (to either week 11 or week 23). Active nicotine patch use started in week −2 and involved use of one 14-mg patch/d until either 12 weeks or 24 weeks after the target quit day. Placebo products had the same use instructions as the respective active products (eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

Cessation Counseling

Participants received six 15-minute counseling sessions at visits 1, 2, and 3 (ie, at week −2, target quit day, and week 2) and during calls at weeks −1, 4, and 8. Counseling focused on instructions for medication use, support, coping skills, and motivation to quit. A manual was created to standardize the counseling and the audio during the sessions was recorded for quality assurance assessment and feedback.

Assessments

Baseline assessments occurred at the group orientation and at visit 1, which occurred 2 weeks before the target quit day. Questionnaires assessed smoking history and nicotine use, nicotine dependence, and negative affect. Treatment contacts (at week −2, week −1, target quit day, week 2, week 4, and week 8) included assessments of smoking, noncigarette nicotine use, exhaled CO level (at in-person visits), treatment mechanisms (eg, withdrawal), medication use, and adverse events. Participants provided nightly interactive voice responses to calls for 3 days prior to treatment, 14 days prior to the target quit day, and 14 days after the target quit day. The interactive voice response calls assessed withdrawal, tobacco use, and medication use.

Participants were contacted at weeks 11, 17, 23, 39, and 52 after the target quit day for a telephone assessment of smoking status, use of other nicotine products or cessation aids, medication use, and adverse events. Participants claiming abstinence at weeks 23 or 52 were invited to in-person biochemical testing.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was self-reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence (biochemically confirmed with exhaled CO level ≤5 ppm) at 52 weeks after the target quit day19 collected by blinded research staff. Secondary abstinence outcomes included self-reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence (biochemically confirmed with exhaled CO level) at 23 weeks after the target quit day and prolonged abstinence defined as no smoking from day 7 to day 160 and from day 7 to day 352 after the target quit day (target quit day = day 0). COVID-19 restrictions prevented biochemical confirmation of abstinence in some participants.

The interactive voice response calls yielded 2 withdrawal measures for post hoc determination: (1) the mean of 5 noncraving withdrawal items (assessing negative mood, concentration, and sleep quality) and (2) the mean of 2 craving items. The withdrawal and craving items were rated on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all; 7 = extremely) and computed as means for the 7 days prior to and following the target quit day.

Medication adherence during the prior week was determined using self-reports of medication use for the 7 days prior to study contacts from week −1 to week 24 (2 visits and 6 calls). Adherence during the prior week for varenicline was defined post hoc as taking 1 or 2 pills per day for 6 days or longer and using 1 nicotine patch per day for 6 days or longer (0 = nonadherent and 1 = adherent).

Sample Size Calculation

The a priori analyses estimating power using the Pearson χ2 test for 2 proportions focused on the primary outcome and the main effect comparisons assuming P < .05 and 2-tailed tests. This study was powered to detect an increase in abstinence of at least 9% at week 52 in the active condition vs the inactive (placebo) condition for each factor (medication type and medication duration), assuming a base abstinence rate of 29% in the inactive conditions for both factors,3,18 and with a planned sample size of 1000. The difference in abstinence of at least 9% reflected a midpoint in the abstinence rates from the 2 prior studies3,5 that reported long-term follow-up for combination treatment with varenicline and nicotine patch. Participant recruitment was more efficient than anticipated, enabling a larger sample size than planned. Prior to examining any results, the decision was made to expand recruitment to 1250 participants to increase power if the treatment effects were somewhat less than forecast (approved by the institutional review board on November 9, 2018).

Statistical Analysis

The binary primary outcome was analyzed via logistic regression, using effect coding to model effects for the medication type and medication duration main and interaction effects. Study site was included as a dummy-coded covariate in the model. Similar logistic regression models were used to analyze secondary abstinence outcomes. The primary abstinence outcome and the secondary outcomes were analyzed with risk differences of the specific treatment combinations relative to standard treatment (varenicline monotherapy for 12 weeks) with adjustment for site. The main analyses of the abstinence outcome models were analyzed according to randomization group and assumed that missing observations reflected ongoing smoking. For the analysis of 23-week and 52-week point prevalence abstinence, post hoc sensitivity analyses (using a pattern-mixture strategy that incorporated multiple imputation) were conducted assuming that missingness was related to ongoing smoking at elevated odds ratios (ORs) of either 2 or 5.20,21 The results were similar across these different assumptions about missingness (eMethods and eTables 2A-2B in Supplement 2).

Bivariable and multivariable models also were computed for the secondary analyses of all abstinence outcomes with sex, race, treatment site, and level of tobacco dependence (Fagerström Test of Cigarette Dependence [FTCD] item 1) used as prespecified covariates. A larger set of covariates was used in post hoc logistic regression analyses to determine covariate relationships with the primary 52-week abstinence outcome. This same larger set of covariates was used in post hoc moderation analyses incorporating separate logistic regression models that included effect coding for treatment, dummy coding for the covariate, and the interaction of the covariate with each treatment factor. Means and percentages are reported for several post hoc outcomes for which there were no prespecified analyses. The means for the 2 withdrawal outcomes were calculated for the first week after the quit date and were analyzed with linear regression in which values prior to the quit date (mean score 1 week prior to the target quit day) were used as covariates to determine the change between the 2 dates. The medication adherence, adverse events, and visit and call attendance data permitted post hoc computation of proportions for each of the 4 treatment groups. A bivariate histogram was computed for the brief 37-item Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM37) assessment (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2).

The significance threshold was P < .05 for all tests, testing was 2-sided, and the statistical analyses were computed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, the findings for the analyses of the secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Participant demographics and smoking-related variables appear in Table 1. Among 1251 patients who were randomized (mean [SD] age, 49.1 [11.9] years; 675 [54.0%] women), 751 (60.0%) completed treatment and 881 (70.4%) provided final follow-up.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics and Baseline Smoking-Related Variables.

| Treatment duration of 12 wk | Treatment duration of 24 wk | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Varenicline monotherapy (n = 315) |

Varenicline plus nicotine patch (n = 314) |

Varenicline monotherapy (n = 311) |

Varenicline plus nicotine patch (n = 311) |

|

| Sex, No. (%) | ||||

| Female | 171 (54.3) | 171 (54.5) | 167 (53.7) | 166 (53.4) |

| Male | 144 (45.7) | 143 (45.5) | 144 (46.3) | 145 (46.6) |

| Race, No. (%)a | ||||

| Asian | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (1.0) |

| Black/African American | 70 (22.2) | 71 (22.6) | 78 (25.2) | 68 (21.9) |

| Native American/Alaska Native | 5 (1.6) | 3 (1.0) | 2 (0.6) | 4 (1.3) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| White | 219 (69.5) | 221 (70.4) | 214 (69.0) | 213 (68.5) |

| Other | 12 (3.8) | 12 (3.8) | 6 (1.9) | 14 (4.5) |

| >1 | 6 (1.9) | 5 (1.6) | 7 (2.3) | 9 (2.9) |

| Hispanic ethnicity, No. (%) | 10 (3.3) | 14 (4.7) | 5 (1.7) | 12 (4.0) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 48.9 (12.4) | 48.6 (11.4) | 48.9 (12.3) | 49.9 (11.5) |

| Income ≥$35 000, No. (%) | 166 (56.3) | 182 (61.7) | 162 (54.5) | 159 (55.4) |

| Education level of at least some college, No. (%) | 208 (66.7) | 195 (62.3) | 227 (73.5) | 212 (68.6) |

| Cigarettes per day, mean (SD) | 15.9 (7.6) | 16.0 (7.3) | 16.2 (7.4) | 16.0 (7.7) |

| Smoking history, mean (SD), y | 28.7 (12.8) | 27.5 (12.3) | 28.9 (12.8) | 28.7 (12.1) |

| Fagerström Test of Cigarette Dependence score, mean (SD)b | 5.1 (2.0) | 4.9 (2.0) | 4.9 (2.0) | 5.0 (2.1) |

| Heaviness of Smoking Index, mean (SD)c | 3.0 (1.2) | 3.0 (1.2) | 3.0 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.3) |

| Exhaled carbon monoxide level, mean (SD), ppm | 16.9 (9.6) | 16.5 (9.0) | 16.9 (9.6) | 16.4 (9.7) |

| Smokes menthol cigarettes, No. (%) | 181 (57.5) | 164 (52.2) | 179 (57.7) | 158 (50.8) |

| Prior use of cessation medication, No. (%)d | 244 (77.5) | 248 (79.0) | 245 (79.0) | 255 (82.0) |

| Prior use of varenicline, No. (%) | 124 (39.4) | 136 (43.3) | 149 (48.1) | 133 (42.8) |

| Lives with another person who smokes, No. (%) | 134 (42.5) | 109 (34.7) | 125 (40.3) | 112 (36.0) |

| Motivation to quit score, mean (SD)e | 6.4 (0.9) | 6.4 (0.9) | 6.4 (0.8) | 6.4 (0.9) |

| Confidence in quitting score, mean (SD)e | 5.5 (1.4) | 5.5 (1.3) | 5.5 (1.3) | 5.5 (1.3) |

Participants selected among the following choices and could mark all that apply: Asian, Black/African American, Native American/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, White, or other (individuals who indicated that they did not belong in any of the categories), do not know/not sure, or refuse to answer.

Six-item scale with 4 binary items scored 0 or 1 and 2 multiple choice items scored from 0 to 3. The score range is 0 to 10, with values near 5 representing a moderate level of cigarette dependence.

Two-item scale derived from the Fagerström Test of Cigarette Dependence with items assessing the number of cigarettes smoked per day and latency to smoke after waking; higher scores indicate greater smoking dependence (range, 0-6). The obtained mean scores indicate a moderate level of dependence.

Varenicline or nicotine patch, gum, or lozenge.

Rated on a scale from 1 to 7 (1 = not at all; 7 = extremely). The obtained mean scores, ranging from 5.5 to 6.4 (out of a maximum of 7), indicate strong agreement about being motivated to quit and having confidence in ability to quit.

Primary Outcome

Of the 1251 participants, 967 (77.3%) provided 12-month self-reported follow-up data and 477 (49.3% of 967) claimed abstinence. Of the 477 participants who claimed abstinence, 317 (66.5%) were able to undergo the CO test and 74 (15.5% of 477 claiming abstinence and 5.9% of all participants in the study) were not able to undergo the CO test due to COVID-19 restrictions. Of those who underwent the CO test, 247 participants (77.9% of 317) had their self-report confirmed by the CO test results.

For 7-day point prevalence abstinence (biochemically confirmed with exhaled CO level) rates at 52-week follow-up, there was no significant interaction between the 2 treatment factors of medication type and medication duration (OR, 1.03 [95% CI, 0.91 to 1.17]; P = .66). For patients randomized to 24-week vs 12-week treatment duration, the primary outcome occurred in 24.8% (154/622) vs 24.3% (153/629), respectively (risk difference, −0.4% [95% CI, −5.2% to 4.3%]; OR, 1.01 [95% CI, 0.89 to 1.15]; Table 2). For patients randomized to varenicline combination therapy vs varenicline monotherapy, the primary outcome occurred in 24.3% (152/625) vs 24.8% (155/626), respectively (risk difference, 0.4% [95% CI, −4.3% to 5.2%]; OR, 0.99 [95% CI, 0.87 to 1.12]).

Table 2. Biochemically Confirmed 7-Day Point Prevalence Abstinence Rates at Weeks 23 and 52 and Prolonged Abstinence Rates by Treatment Main Effects of Medication Type and Duration.

| Abstinent, No. (%)a | Main effects | Site-adjusted OR (95% Cl)c | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication type | Medication duration | Medication type | Medication duration | ||||||||

| Varenicline monotherapy (n = 626) |

Varenicline plus nicotine patch (n = 625) |

12 wk (n = 629) | 24 wk (n = 622) | Abstinence RD for monotherapy vs combination therapy, % (95% CI)b |

P value | Abstinence RD for 12 wk vs 24 wk, % (95% CI)b |

P value | Medication type of monotherapy vs combination therapy | Medication duration of 12 wk vs 24 wk | Medication type × medication duration interaction | |

| 7-d point prevalence abstinence d | |||||||||||

| At 23 wk | 136 (21.7) | 156 (25.0) | 140 (22.3) | 152 (24.4) | −3.2 (−7.9 to 1.5) | .18 | −2.2 (−6.9 to 2.5) | .37 | 1.1 (0.96 to 1.2) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) |

| At 52 wke | 155 (24.8) | 152 (24.3) | 153 (24.3) | 154 (24.8) | 0.4 (−4.3 to 5.2) | .85 | −0.4 (−5.2 to 4.3) | .86 | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) |

| Prolonged abstinence | |||||||||||

| At 23 wkf | 137 (21.9) | 139 (22.2) | 138 (21.9) | 138 (22.2) | −0.4 (−5.0 to 4.2) | .90 | −0.3 (−4.8 to 4.4) | .93 | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.2) |

| At 52 wkg | 101 (16.1) | 104 (16.6) | 102 (16.2) | 103 (16.6) | −0.5 (−4.6 to 3.6) | .83 | −0.3 (−4.5 to 3.8) | .89 | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.1 (0.96 to 1.3) |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; RD, risk difference.

Missing values were imputed.

Tested via SAS Proc Freq.

Based on a logistic regression analysis controlling for site.

Biochemically confirmed via exhaled carbon monoxide testing (level of ≤5 ppm).

This is the primary outcome.

No smoking from day 7 to week 23 after the target quit day.

No smoking from day 7 to week 52 after the target quit day.

The participants who claimed abstinence (n = 74, ranging from 16-21 participants across the 4 treatment groups) but could not be biochemically verified with exhaled CO level for 52-week abstinence because of COVID-19 restrictions were treated as abstinent in the outcome analyses (Table 2) and were treated as having missing 52-week outcome data in the sensitivity analyses. No significant effects were found for the primary outcome across any of the sensitivity analyses (eTables 2A-2B in Supplement 2) or in the analyses with the 4 prespecified covariates of sex, race, treatment site, and level of tobacco dependence (eTables 3-4 in Supplement 2).

The primary outcome also was analyzed in a prespecified analysis that compared the group receiving 12 weeks of varenicline monotherapy vs the other 3 treatment groups generated by the factorial design. The 52-week abstinence rates for the 4 treatment groups adjusted for site appear in Table 3; there were no significant between-group differences for the standard duration of varenicline monotherapy (12 weeks) and any other treatment group.

Table 3. Biochemically Confirmed 7-Day Point Prevalence Abstinence Rates at Weeks 23 and 52 and Prolonged Abstinence Rates Adjusted for Site.

| Abstinent, No. (%)a | Abstinence RD for varenicline monotherapy vs varenicline plus nicotine patch for 12 wk, % (95% CI)b |

P value | Abstinence RD for varenicline monotherapy for 12 wk vs 24 wk, % (95% CI)b |

P value | Abstinence RD for varenicline monotherapy for 12 wk vs varenicline plus nicotine patch for 24 wk, % (95% CI)b |

P value | Site-adjusted OR (95% Cl)c | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment duration of 12 wk | Treatment duration of 24 wk | ||||||||||||

| Varenicline monotherapy (n = 315) |

Varenicline plus nicotine patch (n = 314) |

Varenicline monotherapy (n = 311) |

Varenicline plus nicotine patch (n = 311) |

Varenicline monotherapy vs varenicline plus nicotine patch for 12 wk | Varenicline monotherapy for 12 wk vs 24 wk | Varenicline monotherapy for 12 wk vs varenicline plus nicotine patch for 24 wk | |||||||

| 7-d point prevalence abstinence d | |||||||||||||

| At 23 wk | 66 (21.0) | 74 (23.6) | 70 (22.5) | 82 (26.4) | −2.6 (−9.1 to 3.9) | .44 | −1.6 (−8.0 to 4.9) | .61 | −5.4 (−12.1 to 1.2) | .12 | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.7) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.6) | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.0) |

| At 52 wke | 79 (25.1) | 74 (23.6) | 76 (24.4) | 78 (25.1) | 1.5 (−5.2 to 8.2) | .66 | 0.6 (−6.1 to 7.4) | .85 | −0.0 (−6.8 to 6.8) | >.99 | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.3) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) |

| Prolonged abstinence | |||||||||||||

| At 23 wkf | 72 (22.9) | 66 (21.0) | 65 (20.9) | 73 (23.5) | 1.8 (−4.6 to 8.3) | .65 | 2.0 (−4.5 to 8.3) | .60 | −0.6 (−7.2 to 6.0) | .86 | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.3) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.3) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.5) |

| At 52 wkg | 55 (17.5) | 47 (15.0) | 46 (14.8) | 57 (18.3) | 2.5 (−3.3 to 8.3) | .43 | 2.7 (−3.1 to 8.4) | .37 | −0.9 (−6.9 to 5.1) | .81 | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.3) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.3) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.6) |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; RD, risk difference.

Missing values were imputed.

Tested via SAS Proc Genmod controlling for site.

Based on a logistic regression analysis controlling for site.

Biochemically confirmed via exhaled carbon monoxide testing (level of ≤5 ppm).

This is the primary outcome.

No smoking from day 7 to week 23 after the target quit day.

No smoking from day 7 to week 52 after the target quit day.

Secondary Outcomes

There were no significant main or interaction effects for 7-day point prevalence abstinence at 23-week follow-up for medication duration (risk difference, −2.2% [95% CI, −6.9% to 2.5%]) or for medication type (risk difference, −3.2% [95% CI, −7.9% to 1.5%]). There were no significant effects for prolonged abstinence at 23-week follow-up for medication duration (risk difference, −0.3% [95% CI, −4.8% to 4.4%]) or for medication type (risk difference, −0.4% [95% CI, −5.0% to 4.2%]). There were no significant effects for prolonged abstinence at 52-week follow-up for medication duration (risk difference, −0.3% [95% CI, −4.5% to 3.8%]) or for medication type (risk difference, −0.5% [95% CI, −4.6% to 3.6%]; Table 2 and eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

When standard duration (12 weeks) varenicline monotherapy was compared with the other 3 treatment groups, neither extended duration (24 weeks) varenicline monotherapy nor either standard or extended duration varenicline combination therapy significantly increased abstinence in any of the secondary abstinence outcomes (Table 3 and eTable 4 in Supplement 2).

Post Hoc Outcomes

An expanded set of binary variables was evaluated for bivariable association with 52-week point prevalence abstinence (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2). The significant variables associated with increased likelihood of 52-week CO-confirmed point prevalence abstinence (values predicting higher abstinence likelihood are listed first) were older age (>49 years) vs younger age (18-49 years) (risk difference, 5.0% [95% CI, 2.7% to 9.8%]); White race vs non-White race (risk difference, 8.7% [95% CI, 3.8% to 13.6%]); smoking within 30 minutes of awakening vs later (FTCD item 1; risk difference, 9.7% [95% CI, 3.1% to 16.3%]); below the median vs above the median for the WISDM37 primary score (risk difference, 9.0% [95% CI, 4.3% to 13.7%]); lower (0-4) vs higher (5-10) FTCD total score (risk difference, 7.1% [95% CI, 2.2% to 12.1%]); no menthol cigarette smoking vs menthol cigarette smoking (risk difference, 6.3% [95% CI, 1.5% to 11.1%]); and lower (5-14 ppm) vs higher (>14 ppm) exhaled CO level at baseline (risk difference, 5.6% [95% CI, 0.8% to 10.4%]; eFigure 2 in Supplement 2).

Of the variables that were significantly related to increased abstinence in the bivariable models, only White vs Non-White race (adjusted risk difference, 9.8% [95% CI, 3.9% to 15.7%]), older age (>50 years) vs younger age (18-49 years) (adjusted risk difference, 5.0% [95% CI, 0.2% to 9.9%]), and baseline exhaled CO level of 5 ppm to 14 ppm vs 15 ppm or higher (adjusted risk difference, 8.5% [95% CI, 3.2% to 13.9%]) remained statistically significant in a multivariable model including all the covariates.

The covariates also were examined as moderators of response to the medication type and medication duration factors. There were no significant 2-way interactions with treatment for any covariate (eTable 5 and eFigure 1 [distribution of the WISDM3722 total score] in Supplement 2).

The adherence rates for the nicotine patch and the varenicline pills (assessed on the target quit date and after the quit date at weeks 2, 4, 8, 11, and 23 that reflect adherence during the prior week) appear in eTable 6 in Supplement 2. The mean attendance rate at both counseling sessions prior to the quit date was 85%; 71% of participants attended more than 2 of the 4 counseling sessions after the quit date (eTable 7 in Supplement 2). The means for noncraving withdrawal symptoms during the first week after the quit date and the means for the craving ratings (both with statistical adjustment for baseline score) appear in eTable 8 in Supplement 2.

Adverse Events

Across the 4 treatment groups, the most common adverse events were nausea, insomnia, and changes in mood (Table 4), with 24.0% to 30.9% of participants reporting nausea and 24.4% to 30.5% reporting insomnia.

Table 4. Adverse Events Among Participants During the First 12 Weeks of Treatment.

| Adverse eventa | Adverse event, No. (%) | Adverse event RD, % (95% CI)b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment duration of 12 wk | Treatment duration of 24 wk | Varenicline monotherapy vs varenicline plus nicotine patch for 12 wk | Varenicline monotherapy for 12 wk vs 24 wk | Varenicline monotherapy for 12 wk vs varenicline plus nicotine patch for 24 wk | |||

| Varenicline monotherapy (n = 300) |

Varenicline plus nicotine patch (n = 305) |

Varenicline monotherapy (n = 307) |

Varenicline plus nicotine patch (n = 295) |

||||

| Insomnia | 88 (29.3) | 93 (30.5) | 83 (27.0) | 72 (24.4) | −1.2 (−8.5 to 6.1) | 2.3 (−4.9 to 9.5) | 4.9 (−2.2 to 12.0) |

| Nausea | 72 (24.0) | 92 (30.2) | 95 (30.9) | 73 (24.7) | −6.2 (−13.2 to 0.9) | −6.9 (−14.0 to 0.1) | −0.8 (−7.7 to 6.2) |

| Changes in mood | 48 (16.0) | 50 (16.4) | 50 (16.3) | 53 (18.0) | −0.4 (−6.3 to 5.5) | −0.3 (−6.1 to 5.6) | −2.0 (−8.0 to 4.1) |

| Skin rash | 34 (11.3) | 53 (17.4) | 30 (9.8) | 51 (17.3) | −6.0 (−11.6 to −0.5) | 1.6 (−3.3 to 6.5) | −6.0 (−11.6 to −0.3) |

| Headache | 20 (6.9) | 12 (3.9) | 17 (5.5) | 16 (5.4) | 2.7 (−0.8 to 6.3) | 1.1 (−2.7 to 4.9) | 1.2 (−2.6 to 5.1) |

| Itching or hives | 9 (3.0) | 40 (13.1) | 14 (4.6) | 39 (13.2) | −10.1 (−14.4 to −5.9) | −1.6 (−4.6 to 1.5) | −10.2 (−14.5 to −5.9) |

Abbreviation: RD, risk difference.

Includes only those that exceeded 5%. Two participants experienced a serious adverse event that was definitely related to varenicline medication (1 for an allergic reaction and 1 for anaphylaxis); neither participant was hospitalized as a result of the serious adverse event.

SAS Proc Freq RISKDIFF was used to obtain standard Wald asymptotic confidence limits.

Discussion

Among adults smoking 5 cigarettes/d or more, there were no statistically significant differences in 7-day point prevalence abstinence at 52 weeks among those treated with combined therapy of varenicline pills plus nicotine patch vs varenicline monotherapy, or among those treated with varenicline monotherapy for 24 weeks vs 12 weeks. No statistically significant interactions were observed for these 2 treatment factors of medication type and medication duration. Furthermore, no statistically significant effects were obtained when the group receiving 12 weeks of varenicline monotherapy was compared with each of the other 3 treatment groups. No statistically significant differences were obtained with biochemically confirmed point prevalence abstinence at 23-week follow-up or with prolonged abstinence assessed at weeks 23 or 52. These findings do not support recommendations that combination therapy with varenicline plus the nicotine patch be used in clinical care or that extended duration varenicline therapy be used during quit attempts.

The standard 12-week varenicline monotherapy used in this study did not have an exceptionally high abstinence rate, and thus likely did not produce a ceiling effect. The abstinence rate for participants in this group was similar to, or lower than, rates obtained with such treatment in prior studies.18,23,24,25 It is unclear why standard varenicline combination therapy or extended varenicline monotherapy produced some positive effects in prior trials but showed little evidence of enhanced effectiveness in the present study.

The analyses revealed no significant moderation effects for any of the covariates used in those analyses; thus, no subgroup of participants was identified for whom the effectiveness of the different treatments varied significantly. Post hoc analyses showed small differences in varenicline use at some time points, with those receiving the active nicotine patch appearing to use less varenicline than those getting only varenicline. It is unclear how much this modest reduction in varenicline use might have affected the effectiveness of the combination treatment but such competitive intertreatment effects are common.26

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, a small percentage of participants was unable to have their self-report of abstinence biochemically confirmed at 12-month follow-up due to COVID-19 restrictions. However, the results were not meaningfully affected if these individuals were assumed to be smoking or missing at relevant follow-up time points. Second, adherence to medication declined over the course of the study.

Third, about 23% of the sample was lost to follow-up at the 52-week follow-up time point and 9% of participants withdrew from the study. Such loss of data might have reduced the accuracy of the effect sizes obtained and perhaps contributed to the failure to detect predicted group differences.

Conclusions

Among adults smoking 5 cigarettes/d or more, there were no significant differences in 7-day point prevalence abstinence at 52 weeks among those treated with combined varenicline plus nicotine patch therapy vs varenicline monotherapy, or among those treated for 24 weeks vs 12 weeks. These findings do not support the use of combined therapy or of extended treatment duration.

Trial protocol

eTable 1. Medication dosing in the experimental conditions

eTable 2A. Results for logistic regression analyses under four assumptions about missing outcomes, biochemically-confirmed 7-day point prevalence abstinence rates (CO cutoff=5 ppm) at week 23

eTable 2B. Results for logistic regression analyses under four assumptions about missing outcomes, biochemically-confirmed 7-day point prevalence abstinence rates (CO cutoff=5 ppm) at week 52

eTable 3. Biochemically confirmed (CO ≤ 5 ppm) 7-day point prevalence abstinence rates at weeks 23 and 52, and prolonged abstinence by treatment factors, with 4 covariates

eTable 4. Biochemically-confirmed 7-day point prevalence abstinence rates (CO cutoff=5 ppm) at weeks 23 and 52, and prolonged abstinence by the 4 treatment conditions, with four prespecified covariates

eTable 5. Moderation analyses for a priori covariates and week 52 biochemically confirmed point prevalence abstinence (CO cutoff=5 ppm)

eTable 6. Patch and varenicline adherence data (n’s and percentages) among participants in the four treatment conditions

eTable 7. Pre-quit and post-quit counseling call and visit attendance data (n’s and percentages) among participants in the four treatment conditions

eTable 8. Means of first week post-quit non-craving withdrawal and craving with statistical adjustment for baseline pre-quit score

eMethods

eFigure 1. Histogram of the Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives, brief version total score

eFigure 2. Associations of demographic and smoking related variables with 52-week point prevalence abstinence

eReferences

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Patnode CD, Henderson JT, Coppola EL, Melnikow J, Durbin S, Thomas RG. Interventions for tobacco cessation in adults, including pregnant persons: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;325(3):280-298. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.23541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindson N, Chepkin SC, Ye W, Fanshawe TR, Bullen C, Hartmann-Boyce J. Different doses, durations and modes of delivery of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;4:CD013308. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koegelenberg CF, Noor F, Bateman ED, et al. Efficacy of varenicline combined with nicotine replacement therapy vs varenicline alone for smoking cessation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(2):155-161. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hajek P, Smith KM, Dhanji AR, McRobbie H. Is a combination of varenicline and nicotine patch more effective in helping smokers quit than varenicline alone? a randomised controlled trial. BMC Med. 2013;11:140. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramon JM, Morchon S, Baena A, Masuet-Aumatell C. Combining varenicline and nicotine patches: a randomized controlled trial study in smoking cessation. BMC Med. 2014;12:172. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0172-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang PH, Chiang CH, Ho WC, Wu PZ, Tsai JS, Guo FR. Combination therapy of varenicline with nicotine replacement therapy is better than varenicline alone: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:689. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2055-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leone FT, Zhang Y, Evers-Casey S, et al. Initiating pharmacologic treatment in tobacco-dependent adults: an official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(2):e5-e31. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202005-1982ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barua RS, Rigotti NA, Benowitz NL, et al. 2018 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on tobacco cessation treatment: a report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(25):3332-3365. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force . Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021;325(3):265-279. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.25019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schlam TR, Fiore MC, Smith SS, et al. Comparative effectiveness of intervention components for producing long-term abstinence from smoking: a factorial screening experiment. Addiction. 2016;111(1):142-155. doi: 10.1111/add.13153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes JR, Solomon LJ, Peasley-Miklus CE, Callas PW, Fingar JR. Effectiveness of continuing nicotine replacement after a lapse: a randomized trial. Addict Behav. 2018;76:68-81. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnoll RA, Goelz PM, Veluz-Wilkins A, et al. Long-term nicotine replacement therapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):504-511. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evins AE, Cather C, Pratt SA, et al. Maintenance treatment with varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(2):145-154. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.285113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzales D, Hajek P, Pliamm L, et al. Retreatment with varenicline for smoking cessation in smokers who have previously taken varenicline: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;96(3):390-396. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2014.124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livingstone-Banks J, Norris E, Hartmann-Boyce J, West R, Jarvis M, Hajek P. Relapse prevention interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2:CD003999. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003999.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulak JA, Cornelius ME, Fong GT, Giovino GA. Differences in quit attempts and cigarette smoking abstinence between Whites and African Americans in the United States: literature review and results from the International Tobacco Control US Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(suppl 1):S79-S87. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nollen NL, Ahluwalia JS, Sanderson Cox L, et al. Assessment of racial differences in pharmacotherapy efficacy for smoking cessation: secondary analysis of the EAGLES randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2032053. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.32053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker TB, Piper ME, Stein JH, et al. Effects of nicotine patch vs varenicline vs combination nicotine replacement therapy on smoking cessation at 26 weeks: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(4):371-379. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.19284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benowitz NL, Bernert JT, Foulds J, et al. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and abstinence: 2019 update. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(7):1086-1097. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hedeker D, Mermelstein RJ, Demirtas H. Analysis of binary outcomes with missing data: missing = smoking, last observation carried forward, and a little multiple imputation. Addiction. 2007;102(10):1564-1573. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01946.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Little RJA. Pattern-mixture models for multivariate incomplete data. J Am Stat Assoc. 1993;88(421):125-134. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1993.10594302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith SS, Piper ME, Bolt DM, et al. Development of the Brief Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence motives. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(5):489-499. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aubin HJ, Bobak A, Britton JR, et al. Varenicline versus transdermal nicotine patch for smoking cessation: results from a randomised open-label trial. Thorax. 2008;63(8):717-724. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.090647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, et al. ; Varenicline Phase 3 Study Group . Varenicline, an α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296(1):47-55. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams KE, Reeves KR, Billing CB Jr, Pennington AM, Gong J. A double-blind study evaluating the long-term safety of varenicline for smoking cessation. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(4):793-801. doi: 10.1185/030079907X182185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker TB, Bolt DM, Smith SS. Barriers to building more effective treatments: negative interactions among smoking-intervention components. Clin Psychol Sci. Published online April 26, 2021. doi: 10.1177/2167702621994551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

eTable 1. Medication dosing in the experimental conditions

eTable 2A. Results for logistic regression analyses under four assumptions about missing outcomes, biochemically-confirmed 7-day point prevalence abstinence rates (CO cutoff=5 ppm) at week 23

eTable 2B. Results for logistic regression analyses under four assumptions about missing outcomes, biochemically-confirmed 7-day point prevalence abstinence rates (CO cutoff=5 ppm) at week 52

eTable 3. Biochemically confirmed (CO ≤ 5 ppm) 7-day point prevalence abstinence rates at weeks 23 and 52, and prolonged abstinence by treatment factors, with 4 covariates

eTable 4. Biochemically-confirmed 7-day point prevalence abstinence rates (CO cutoff=5 ppm) at weeks 23 and 52, and prolonged abstinence by the 4 treatment conditions, with four prespecified covariates

eTable 5. Moderation analyses for a priori covariates and week 52 biochemically confirmed point prevalence abstinence (CO cutoff=5 ppm)

eTable 6. Patch and varenicline adherence data (n’s and percentages) among participants in the four treatment conditions

eTable 7. Pre-quit and post-quit counseling call and visit attendance data (n’s and percentages) among participants in the four treatment conditions

eTable 8. Means of first week post-quit non-craving withdrawal and craving with statistical adjustment for baseline pre-quit score

eMethods

eFigure 1. Histogram of the Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives, brief version total score

eFigure 2. Associations of demographic and smoking related variables with 52-week point prevalence abstinence

eReferences

Data sharing statement