Abstract

A number of microaerophilic eukaryotes lack mitochondria but possess another organelle involved in energy metabolism, the hydrogenosome. Limited phylogenetic analyses of nuclear genes support a common origin for these two organelles. We have identified a protein of the mitochondrial carrier family in the hydrogenosome of Trichomonas vaginalis and have shown that this protein, Hmp31, is phylogenetically related to the mitochondrial ADP-ATP carrier (AAC). We demonstrate that the hydrogenosomal AAC can be targeted to the inner membrane of mitochondria isolated from Saccharomyces cerevisiae through the Tim9-Tim10 import pathway used for the assembly of mitochondrial carrier proteins. Conversely, yeast mitochondrial AAC can be targeted into the membranes of hydrogenosomes. The hydrogenosomal AAC contains a cleavable, N-terminal presequence; however, this sequence is not necessary for targeting the protein to the organelle. These data indicate that the membrane-targeting signal(s) for hydrogenosomal AAC is internal, similar to that found for mitochondrial carrier proteins. Our findings indicate that the membrane carriers and membrane protein-targeting machinery of hydrogenosomes and mitochondria have a common evolutionary origin. Together, they provide strong evidence that a single endosymbiont evolved into a progenitor organelle in early eukaryotic cells that ultimately give rise to these two distinct organelles and support the hydrogen hypothesis for the origin of the eukaryotic cell.

A variety of phylogenetically diverse eukaryotes, including ciliates, fungi, and amoeboflagellates, lack typical eukaryotic organelles such as the mitochondrion and the peroxisome. Interestingly, these organisms often contain a double-membrane-bounded organelle called the hydrogenosome (32, 40). Organisms that contain this organelle live in microaerophilic habitats and rely on the hydrogenosome for fermentative carbohydrate metabolism. Similar to mitochondria, the hydrogenosome produces ATP, requiring its exchange with ADP from the cytosol. The hydrogenosome participates in carbohydrate metabolism, producing ATP, carbon dioxide, acetate, and molecular hydrogen from the fermentation of pyruvate. In this respect, hydrogenosomes can be regarded as the anaerobic equivalents of mitochondria as ATP generators in these cells.

Although similar in many aspects, mitochondria and hydrogenosomes differ significantly in structure and function. The absence of cristae, DNA, F1F0 ATPase, respiratory-chain components, and cardiolipin and the presence of the enzymes hydrogenase and pyruvate-ferredoxin oxidoreductase in the hydrogenosome set it apart from the mitochondrion (17, 32). Based on the detection of enzymes typically present in anaerobic bacteria, it was proposed that the hydrogenosome originated from an endosymbiont related to the strict anaerobe Clostridium (31). Later, emerging similarities between mitochondria and hydrogenosomes led to the proposal that hydrogenosomes were converted mitochondria that lost their respiratory function as a result of movement into anaerobic habitats (6). Unfortunately, the lack of hydrogenosomal DNA has precluded a direct analysis of the origin of hydrogenosomes similar to that carried out using mitochondrial DNA which demonstrated that mitochondria evolved from an endosymbiont of the α-proteobacterial family (14).

Recently, molecular analyses of hydrogenosomal heat shock proteins from Trichomonas vaginalis (5, 11, 16, 41) have demonstrated a close phylogenetic relationship between the nuclear genes encoding these proteins and their mitochondrial counterparts, suggesting a common symbiotic origin for the two organelles. The latest theory is one based on the metabolic force behind the symbiotic event—the hydrogen hypothesis (29). This hypothesis propounds that an α-proteobacterium which produced molecular hydrogen and carbon dioxide established a symbiosis with a methanogenic archaeon that utilized these as sources of energy. As these gases became depleted with changes in the early Earth's atmosphere, the host (the archaeon) would have become dependent on its symbiotic partner for its needs. This association further led to the transfer of genes from the symbiont to the host and to its successful establishment as an organelle. This ancient cell is proposed to be ancestral to eukaryotes that have diverged into a respiratory (mitochondria-containing) or a fermentative (hydrogenosome-containing) fate, depending on their habitats.

A critical step in the evolution of the ancestral endosymbiont to an organelle would be the evolution of membrane proteins to allow communication between the organelle and its host cell. Hydrogenosomes and mitochondria undergo biogenesis by binary fission, followed by translocation of the nuclear-encoded proteins required for their functions (37, 40). Hence, membrane proteins would be essential not only for intracellular transport of substrates and products but also for translocation of host-encoded proteins during organelle biogenesis. These membrane proteins would have evolved at the time of or shortly prior to DNA transfer from symbiont to host nucleus. One of the first such membrane proteins that would have evolved in the case of ATP-producing organelles would be an ADP-ATP exchanger that would provide ATP to the cytosol (6). The evolution of this translocator would not be complete without developing a translocation machinery and organelle-targeting signals, all of which would involve a series of rare mutations. Therefore, the presence of phylogenetically-related membrane proteins and the use of similar translocation pathways for mitochondria and hydrogenosomes would reveal their evolution from a common progenitor if indeed a single ancestor gave rise to them as proposed (4, 29). Previous studies have indicated that common import signals are used for targeting proteins to the matrix of mitochondria and hydrogenosomes (4, 15, 50); however, studies comparing membrane translocation pathways have not been reported.

Here, we report the characterization of the first membrane protein isolated from T. vaginalis hydrogenosomes and demonstrate that it is a member of the mitochondrial carrier family (MCF) (23). Within this group of MCF proteins, phylogenetic analysis indicates that the hydrogenosomal protein has a common origin with ADP-ATP carrier (AAC) proteins. In vivo and in vitro translocation analyses with hydrogenosomes and mitochondria demonstrate that AACs from the two organelles utilize similar translocation pathways and rely on internal signals for specific membrane targeting. These data reveal the presence of conserved membrane carriers in hydrogenosomes and mitochondria and indicate the coevolution of membrane protein-targeting pathways in the two organelles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and sequencing of Hmp31.

Hydrogenosomes were purified from T. vaginalis C1 (ATCC 30001) cultures as described previously (4). The organelles were alkaline extracted by incubation for 30 min at 4°C at a concentration of 0.03 mg/ml in 0.1 M sodium carbonate, pH 11.5 (10). The insoluble fraction was separated from the soluble proteins by centrifugation at 200,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. The insoluble proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue staining. A major band of 31 kDa was excised from the gel and digested with endoproteinase Lys-C (Boehringer Mannheim), and the resulting peptides were subjected to microsequencing. For N-terminal sequencing, the protein was transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes prior to Edman degradation.

Construction and screening of T. vaginalis cDNA and genomic DNA libraries.

A unidirectional cDNA library was constructed in the λZAPII vector (Stratagene) using T. vaginalis poly(A)+ RNA. A fragment of 257 bp, FP257, was amplified from a cDNA pool of 5 × 107 phage using the T7 promoter primer on the vector as a reverse primer and LA1 (Table 1), a degenerate forward primer designed from the peptide PIYSGMMQAF. A genomic library constructed in the λFIXII vector (Stratagene) from 9- to 23-kb T. vaginalis BamHI genomic DNA fragments was screened with FP257, yielding positive clones with 9.4-kb inserts. A 1.7-kb HindIII fragment from one of these was further subcloned into pBluescript KS (Stratagene) and was found by sequencing to contain the complete open reading frame, 948 bp long. DNA and protein sequences were analyzed using the MacVector program (Oxford Molecular Group).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| LA1 | 5′-GGYATGATGCARGCHTTY-3′ |

| 5′ α-SCSBFor | 5′-CGCGAGCTCGAACCGAAAATTCTTA-3′ |

| 5′ α-SCSBRev | 5′-GGCTTTGTTCACTTCACATTACATATGGAATTCC-3′ |

| +2HAKpnBam | 5′-GTACCTACCCATACGATGTTCCAGATTACGCTTACCCATACGATGTTCCAGATTACGCTTAAG-3′ |

| −2HAKpnBam | 5′-GATCCTTAAGCGTAATCTGGAACATCGTATGGGTAAGCGTAATCTGGAACATCGTATGGGTAG-3′ |

| AACHAN | 5′-GGAATTCCATATGGCACAGCCAGCAGAACAG-3′ |

| DAACHAN | 5′-GGAATTCCATATGTCTCCAAAGCCATCCCTCTCACC-3′ |

| AACHAK | 5′-CGGGGTACCTTTCTTCTTTGGAGCAACCTTTCCC-3′ |

| FdHAN | 5′-GGAATTCCATATGCTCTCTCAAGTTTGCCGC-3′ |

| DFdHAN | 5′-GGAATTCCATATGGGAACAATCACAGCCGTCAAGG-3′ |

| FdHAK | 5′-CGGGGTACCGAGCTCGAAAACAGCACCATCG-3′ |

| AACL+ | 5′-TATGGCACAGCCAGCAGAACAGATCCTCATCGCTACATCTCCAAAGCA-3′ |

| AACL− | 5′-TATGCTTTGGAGATGTAGCGATGAGGATCTGTTCTGCTGGCTGTGCCATCA-3′ |

| FdL+ | 5′-TATGCTCTCTCAAGTTTGCCGCTTTGGAACAATCCA-3′ |

| FdL− | 5′-TATGGATTGTTCCAAAGCGGCAAACTTGAGAGAG-3′ |

| AAC1F | 5′-GGAATTCCATATGTCTCACACAGAAACACAGAC-3′ |

| AAC1R | 5′-CGCGGGGTACCCTTGAATTTTTTGCCAAACATTATG-3′ |

Constructs for selectable transformation of T. vaginalis.

The α-SCSB-CAT (α-succinyl coenzyme A synthetase B-chloramphenicol transferase) construct described previously (8) was modified by introducing an NdeI restriction site at the initiation codon of the α-SCSB gene by site-directed mutagenesis. All primers used are listed in Table 1. The construct was digested with SacI and NdeI to replace the 1.66-kb 5′ untranslated region of α-SCSB with a shorter SacI-NdeI-digested 340-bp 5′ untranslated region fragment generated by PCR using the primers 5′ α-SCSBFor and 5′ α-SCSBRev. To generate the dihemagglutinin [(HA)2] epitope tag, primers with KpnI (+2HAKpnBam) and BamHI (−2HAKpnBam) overhangs, respectively, were hybridized to each other and used to replace the CAT gene in the modified α-SCSB-CAT template. The Fd- and Hmp31-coding regions were amplified by PCR to introduce an NdeI site at the initiation codon and a KpnI after the ultimate codon for restriction digestion, followed by ligation into the (HA)2 template. For the Hmp31-(HA)2 and ΔHmp31-(HA)2 constructs, the forward PCR primers used were AACHAN and DAACHAN, respectively, with the reverse primer AACHAK. For the Fd-(HA)2 and ΔFd-(HA)2 constructs, forward PCR primers were FdHAN and DFdHAN, respectively, with the reverse primer FdHAK. For presequence insertion into ΔFd-(HA)2 and ΔHmp31-(HA)2, two sets of primers with NdeI overhangs were designed. For the Hmp31 presequence, these were AACL+ and AACL−; for the Fd presequence, these were FdL+ and FdL−. In each case, the primers corresponded to the presequence and the first three amino acids of the mature protein. These primer sets were annealed and ligated into the NdeI site of the ΔHmp31-(HA)2 or ΔFd-(HA)2 construct to create FdLΔHmp31-(HA)2 and Hmp31LΔFd-(HA)2. For the Saccharomyces cerevisiae AAC1-(HA)2 construct, primers AAC1F and AAC1R were used. A ClaI restriction fragment containing the neomycin phosphotransferase (neo) cassette was transferred into each of the above constructs from the α-TUB-neo construct previously described (27).

Selectable transformation of T. vaginalis.

Electroporation of T. vaginalis strain C1 was carried out as described previously (8) with 30 to 50 μg of circular plasmid DNA. The transformants were selected with G418 (100 μg/ml) prior to crude fractionation and organelle purification.

Crude fractionation of T. vaginalis cells.

T. vaginalis transformant cultures were harvested and resuspended in SMDI (250 mM sucrose, 10 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid [MOPS] [pH 7.2], 10 mM dithiothreitol, Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone [TLCK] [50 μg/ml], and leupeptin [10 μg/ml]). The cells were broken in a cell disrupter (Energy Service Co.) and 100 μl of broken cells was removed as a whole-cell aliquot. One milliliter of the resuspended broken cells was centrifuged at 12,000 × g after which an aliquot of 100 μl of supernatant was removed. The remaining pellet, consisting of the organelles was resuspended in 1 ml of SMDI, from which an aliquot of 100 μl was removed. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Protein sequences of 25 representative MCF members and Hmp31 were aligned using CLUSTAL W (49) and edited manually with LINEUP (Wisconsin package version 10.0; Genetics Computer Group). Phylogenetic analysis was performed on regions corresponding to residues 24 to 280 of the hydrogenosomal protein using maximum-parsimony analysis from PAUP (48) by 50 rounds of random sequence addition heuristic searches with tree bisection reconnection branch swapping on 100 bootstrap replicates. Only groups that occurred in more than 50% of the bootstrap replicates were included in the consensus tree. Protein distance matrices were calculated using the PROTDIST program of the PHYLIP (9) package on 100 bootstrap replicates of the alignment. A majority consensus tree was generated using the FITCH program (9) with five multiple jumbles per replicate and with global rearrangement. Both trees were rooted using the midpoint method.

Import of radiolabelled proteins into isolated mitochondria.

Mitochondria were purified from lactate-grown yeast cells of the tim10-1 mutant and parental strains (13, 21). The protein-coding regions from T. vaginalis Hmp31 and the S. cerevisiae AAC1 genes were subcloned into pSP65 (Promega), and SP6 polymerase was used for in vitro transcription. Proteins were then synthesized in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate in the presence of [35S]methionine. The reticulocyte lysate containing radiolabelled precursor was incubated at 25°C with isolated mitochondria in import buffer (1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 0.6 M sorbitol, 150 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM EDTA, 2 mM ATP, 2 mM NADH, 20 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.4]). Where indicated, the potential across the mitochondrial inner membrane was dissipated with 1 μM valinomycin and 25 μM carbonyl cyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone. Nonimported radiolabelled proteins were removed by treatment with 100 μg of trypsin per ml; trypsin was then inhibited with 200 μg of soybean trypsin inhibitor per ml. Following reisolation, mitochondria were subjected to sodium carbonate extraction, and membrane proteins were separated on SDS–12% PAGE gels, followed by fluorography. Import was quantitated with a laser-scanning densitometer and expressed as a percentage of total import with the four-minute time point of import into wild-type mitochondria set at 100%.

Miscellaneous.

Polyclonal antibodies against endogenous Hmp31 were raised in rabbits and used for immunodecoration of Hmp31 in Western blot analysis. Western blot analyses of the epitope-tagged transformants were performed using an anti-hemagglutinin (HA) mouse immunoglobulin G. Detection in both cases was carried out using the respective secondary horseradish peroxidase-linked immunoglobulin G, followed by enhanced chemiluminescence with Amersham substrates. Quantitation of the scanned images was performed using the IQUANT (Molecular Dynamics) program.

Nucleotide sequence accession number. The sequence for Hmp31 has been deposited with GenBank with the accession number AF216971.

RESULTS

Isolation and characterization of Hmp31.

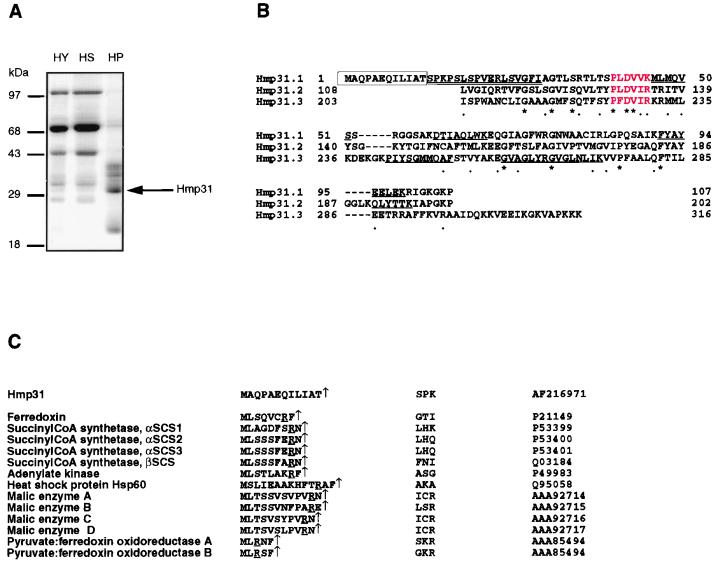

To identify hydrogenosomal translocases, we isolated integral membrane proteins from purified T. vaginalis hydrogenosomes by alkaline extraction (10). One of the most abundant proteins (Fig. 1A), is an approximately 31-kDa protein designated Hmp31 (for hydrogenosomal membrane protein 31), which was microsequenced. A fragment of the gene encoding Hmp31 was amplified from a cDNA library by PCR with primers designed from the peptide sequences. The complete gene was isolated from a genomic DNA library and sequenced, revealing a protein-coding region of 316 amino acids of a calculated molecular mass of 33 kDa. The presence of all six proteolytic peptide sequences generated by analysis of the purified hydrogenosomal membrane protein in the translated sequence confirmed that the correct gene had been isolated and characterized (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, internal protein sequence comparison of Hmp31 revealed a tripartite repeat structure with a frequency of about 100 amino acids (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Abundance and structure of the 31-kDa hydrogenosomal membrane protein Hmp31. (A) SDS-PAGE of hydrogenosomal proteins. Hydrogenosomes (HY) were subjected to sodium carbonate extraction to separate the soluble fraction (HS), comprising matrix and intermembrane space proteins from the insoluble fraction (HP), consisting of integral membrane proteins. Samples were loaded in the ratio HY:HS:HP = 1:1:10, size separated by SDS–12% PAGE, and visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue staining. (B) The Hmp31 protein sequence was divided into three repeat units: Hmp31.1, residues 1 to 107; Hmp31.2, residues 108 to 202; and Hmp31.3, residues 203 to 316, prior to alignment. Identities are indicated by an asterisk (∗) and conserved substitutions by a dot (•). Sequences in red correspond to the MCF degenerate signature sequence P (Hy) (D, E) X X (K, R). Underlined sequences match proteolytic peptide sequences obtained from the endogenous 31-kDa membrane protein. The double-underlined sequence denotes the N-terminal sequence of endogenous Hmp31. The boxed sequence corresponds to the Hmp31 N-terminal presequence. (C) Comparison of the Hmp31 N-terminal presequence with hydrogenosomal matrix protein presequences. The cleavage site, determined by N-terminal sequencing in each reported case, is indicated by a vertical arrow. The first three amino acids from the mature proteins are given. Accession numbers for each protein are indicated in the rightmost column.

N-terminal sequencing of the endogenous Hmp31 protein gave a sequence starting at position 13 of the conceptual translated reading frame, indicating that Hmp31 is synthesized with an N-terminal presequence of 12 amino acids (Fig. 1B) which is cleaved to give rise to the mature hydrogenosomal protein. This N-terminal sequence was confirmed from an independent purification, and protease inhibitors were included throughout our procedures to exclude digestion by cellular exoproteases. Interestingly, the Hmp31 N-terminal presequence is different from hydrogenosomal matrix presequences which we have previously shown to be necessary for targeting matrix proteins (4). Hence, the Hmp31 presequence constitutes a novel presequence (Fig. 1C). The majority of the matrix presequences (Fig. 1C) start with a Met-Leu dipeptide (12 of 13) and are enriched in the amino acids serine, leucine, and arginine. The Hmp31 presequence starts with a Met-Ala dipeptide and bears no arginine or serine residues. The matrix presequences invariantly have arginine at position −2 or −3 relative to the cleavage site, unlike the Hmp31 presequence. Moreover, the matrix presequences (12 of 13) have either a phenylalanine or an asparagine at position −1 relative to the cleavage site that is not found in the Hmp31 presequence. These differences could reflect the presence of two distinct presequence-processing peptidases in the hydrogenosome.

The Hmp31 N-terminal presequence is not necessary for translocation.

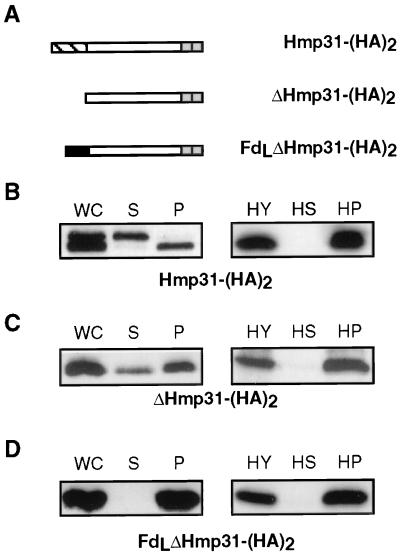

To study the role of the Hmp31 presequence in translocation, we have expressed mutant and chimeric hydrogenosomal proteins in T. vaginalis (8, 27) using the influenza HA epitope to detect the proteins. Constructs carrying the HA-tagged genes also carry a neo gene cassette (24) for selection of transformants. The selectable transformants were lysed and separated into soluble cellular and organellar fractions. Hydrogenosomes were then purified from the organellar fraction (4) and further subjected to alkaline sodium carbonate extraction to separate the hydrogenosomal membrane proteins from the soluble proteins. Western analyses using an anti-HA epitope antibody revealed the location of the protein of interest.

To determine whether the Hmp31 presequence is necessary for translocation, we created two selectable transformants (Fig. 2A) that express Hmp31-(HA)2, a full-length Hmp31 construct with the presequence and ΔHmp31-(HA)2, a mutant Hmp31 construct lacking amino acid residues 2 to 12, corresponding to a presequence-minus version of the protein. Western analysis of a crude fractionation of Hmp31-(HA)2-transformed cells showed that 48% of the expressed protein was present as a precursor-sized species in the soluble cellular fraction and 52% was targeted to the organellar fraction. The targeted protein corresponded in size to the presequence-minus protein, indicating that it had been cleaved (Fig. 2B). Within the organelles, Western blot analysis of Hmp31 revealed its location exclusively in the membrane fraction (Fig. 2B), whereas a known matrix protein, β-succinyl coenzyme A synthetase (24) localized to the supernatant fraction (data not shown). The presence of precursor-sized Hmp31-(HA)2 protein in the soluble cellular fraction could be due to misfolding or overabundance. Within the hydrogenosomes from this transformant, the tagged protein is targeted exclusively to the membrane (Fig. 2B). Similar analyses on the transformant expressing the presequence-minus version revealed that removal of the presequence did not affect translocation to the hydrogenosomes (36% of the expressed protein in the soluble cellular fraction and 64% in the organellar fraction) and also resulted in targeting exclusively to the membrane fraction (Fig. 2C). These results show that the Hmp31 presequence is not necessary for the translocation of Hmp31 to the hydrogenosomal membrane, indicating that the protein bears internal membrane-targeting signals. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the presequence participates in the translocation process.

FIG. 2.

Expression and translocation of epitope-tagged Hmp31 in T. vaginalis. (A) Epitope-tagged full-length Hmp31 and mutant Hmp31 proteins. The C-terminal (HA)2 epitope is denoted by the two adjacent shaded boxes. The Hmp31 presequence is indicated by the hatched box and the Fd presequence by the black box. (B to D) Western blot analysis of fractions from the in vivo transformants shown in panel A with anti-HA antibody. WC, whole cell; S, soluble cellular fraction; P, crude pelleted organelles. Equivalent amounts of each fraction were loaded on the gels so that WC = S + P. HY, purified hydrogenosomes; HS, soluble organellar fraction; P, insoluble membrane pellet from sodium carbonate-extracted hydrogenosomes. Equivalent amounts of soluble and insoluble fractions were loaded so that HY = HS + HP.

We have also investigated the effect of fusing a hydrogenosomal presequence from a matrix protein, ferredoxin, Fd (4, 18, 25), to the presequence-minus Hmp31 moiety by creating a transformant expressing FdLΔHmp31-(HA)2. Interestingly, this fusion protein was exclusively targeted to the organellar fraction, with no detectable trace in the soluble cellular fraction (Fig. 2D). It appears that replacing the Hmp31 presequence with the Fd presequence results in more efficient targeting. Within the hydrogenosomes, the fusion protein was found entirely in the membrane fraction. These data show that the matrix presequence cannot override the internal membrane-targeting signal in the Hmp31 protein and cause mistargeting to the soluble fraction of the hydrogenosome. The Fd presequence was not cleaved upon translocation to the organelle membrane. This is likely to reflect a requirement for a matrix-processing peptidase for cleavage of this presequence. The N terminus of the fusion protein may not be facing the matrix, or the conformation of the presequence may be altered in the fusion protein such that it is no longer a substrate for the processing peptidase.

The Hmp31 N-terminal presequence can replace a hydrogenosomal matrix presequence.

We have previously shown that a presequence-minus version of the Fd protein, ΔFd, was unable to bind to and hence translocate into isolated hydrogenosomes in vitro (4). To test whether the Hmp31 presequence can restore translocation of ΔFd, we transformed T. vaginalis cells with the chimeric construct Hmp31LΔFd-(HA)2, consisting of the Hmp31 presequence fused to presequence-minus Fd (Fig. 3A). As controls, we also generated the transformants Fd-(HA)2 and ΔFd-(HA)2, which express full-length Fd and presequence-minus Fd, respectively (Fig. 3A). Full-length Fd was targeted to the soluble fraction (91%) of purified hydrogenosomes as expected from its matrix location (Fig. 3B). A small amount (9%) was found to be associated with the membranes, perhaps due to saturation of the organelle with this protein. The presequence-minus Fd protein was 100% in the soluble cellular fraction (Fig. 3C), confirming previous in vitro translocation results (4) and showing that the Fd presequence is necessary for translocation into the hydrogenosome in vivo. The addition of the Hmp31 presequence to the presequence-minus Fd restored translocation to the hydrogenosome, with 47% of the protein going to the organellar fraction and 53% in the soluble cellular fraction. As with the fusion protein FdLΔHmp31-(HA)2, no cleavage of the Hmp31 presequence was observed. Within the purified hydrogenosomes, this fusion protein was found only in the soluble fraction. These data show that the Hmp31 presequence, although not necessary for translocation, can substitute for a targeting signal that has been shown to be necessary to direct proteins to the hydrogenosomal soluble fraction (4). Furthermore, the results show that the Hmp31 presequence does not appear to bear any membrane-targeting signal. Thus, it appears that there are at least two types of targeting signals within the precursor Hmp31 protein.

FIG. 3.

Expression and translocation of epitope-tagged Fd in T. vaginalis. (A) Epitope-tagged full-length Fd and mutant Fd proteins. The C-terminal (HA)2 epitope is denoted by the two adjacent shaded boxes. The Hmp31 presequence is indicated by the hatched box and the Fd presequence is indicated by the black box. (B to D) Western analysis of fractions from the above in vivo transformants with anti-HA antibody. WC, whole cell; S, soluble cellular fraction; P, crude pelleted organelles. Equivalent amounts of each fraction were loaded on the gels so that WC = S + P. HY, purified hydrogenosomes; HS, soluble organellar fraction; HP, insoluble membrane pellet from sodium carbonate-extracted hydrogenosomes. Equivalent amounts of soluble and insoluble fractions were loaded so that HY = HS + HP.

Hmp31 appears to be an inner-membrane hydrogenosomal protein.

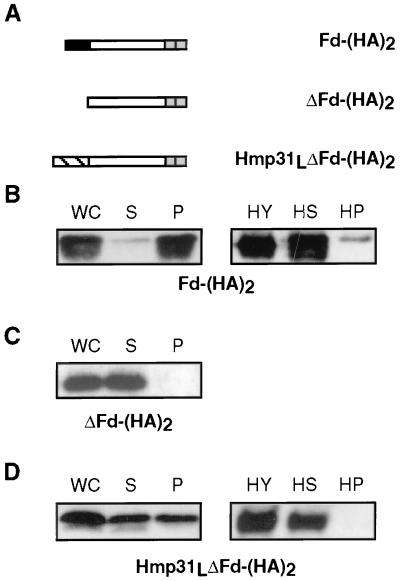

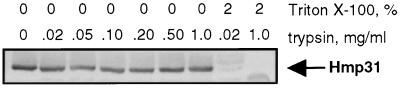

To determine whether Hmp31 is on the outer or the inner membrane of the hydrogenosome, we subjected intact purified wild-type T. vaginalis hydrogenosomes to protease treatment with increasing concentrations of trypsin. The effect on endogenous Hmp31 was monitored by Western analysis of digested hydrogenosomes using a polyclonal anti-Hmp31 antibody (Fig. 4). To ascertain whether the Hmp31 protein is inherently resistant to the protease, we also included Triton X-100-solubilized hydrogenosomes that were exposed to 20 and 1 mg of trypsin per ml, the lowest and the highest trypsin concentrations used in the assay. The Hmp31 protein appeared to be unaffected by the trypsin treatment in intact hydrogenosomes, but the levels were greatly reduced even at concentrations of 20 μg of trypsin per ml and completely abolished at 1 mg of trypsin per ml in the solubilized samples (Fig. 4). Control experiments using an antibody against a matrix protein showed that this protein was also intact in trypsin-treated samples and was digested upon solubilization of the organelles with detergent (data not shown). This assay indicates that the Hmp31 membrane protein is in a protease-protected location, suggesting that it is an inner-membrane hydrogenosomal protein.

FIG. 4.

Endogenous Hmp31 is protected from trypsin digestion in intact hydrogenosomes. Intact hydrogenosomes in SM (250 mM sucrose, 10 mM MOPS [pH 7.2]) at a concentration of 0.5 μg of total protein per ml were subjected to increasing concentrations of trypsin, from 0.02 to 1.0 mg/ml, for 30 min on ice. Two aliquots were solubilized with 2% Triton X-100 prior to trypsin treatment at concentrations of 0.02 and 1.0 mg/ml, respectively. Soybean trypsin inhibitor was added to a final concentration of 2.0 mg/ml to all samples. Following a 5-min incubation on ice, intact hydrogenosomes were washed with SM supplemented with soybean trypsin inhibitor and reisolated by centrifugation. The solubilized samples were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid at a final concentration of 10% and recovered by centrifugation. The pellets and precipitates were resuspended in Laemmli buffer for SDS–12% PAGE separation, followed by Western blotting and analysis using a polyclonal antibody against Hmp31.

Hmp31 is a member of the MCF.

Database homology searches with BLAST showed that Hmp31 displays 16 to 30% identity and 34 to 56% similarity with members of the MCF. The carrier family consists of mostly mitochondrial and some peroxisomal membrane proteins of approximately 30 kDa that translocate anions across the organelle membranes. Protein comparisons and phylogenetic analyses have revealed a common ancestral origin for these carriers (23). Hmp31 is structurally similar to these carriers which are also characterized by three repeats, each about 100 amino acids in length (44). The repeats of MCF proteins consist of two transmembrane domains, resulting in proteins that traverse the membrane six times (23). The mitochondrial MCF proteins are inner-membrane proteins, as appears to be the case for Hmp31 (Fig. 4).

A further characteristic is the presence at three equivalent locations of the degenerate signature sequence P (Hy) (D, E) X X (K, R) where Hy designates a hydrophobic residue and X designates any residue (33). This sequence is present in triplicate in all characterized mitochondrial MCF proteins but is found only in the first two repeat units of peroxisomal MCF members. The alignment of approximately 100 amino-acid segments of Hmp31 revealed such a tripartite structure with three highly conserved MCF signature sequences (Fig. 1B). The highest database hits for Hmp31 are to the mitochondrial Graves' disease carriers of unknown function (30% identity and 48% similarity), followed by the peroxisomal-mitochondrial PECA protein (51), a Ca2+-dependent carrier of unknown function (29% identity and 47% similarity), and finally the mitochondrial AACs (21 to 26% identity and 36 to 44% similarity). The latter group of carriers exchange ATP produced in the mitochondrial matrix with ADP from the cytosol.

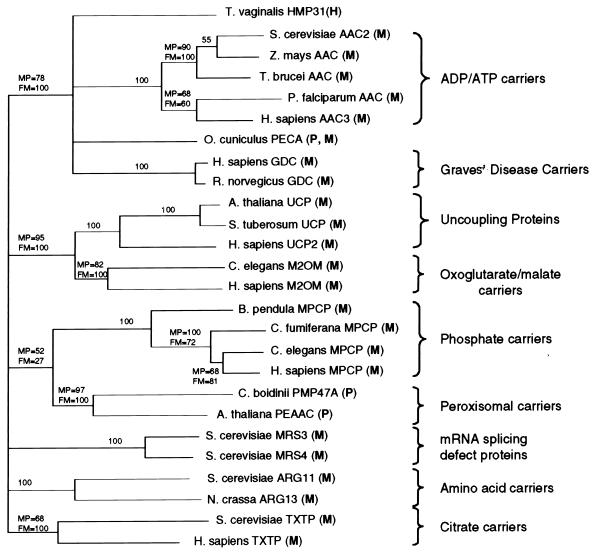

Using maximum-parsimony and distance methods, phylogenetic analyses of Hmp31 with representative members of each subgroup of the MCF proteins showed that this protein groups with high bootstrap values (78% for the maximum-parsimony tree and 100% for the distance tree) with the mitochondrial AACs, the peroxisomal-mitochondrial PECA protein, and the mitochondrial Graves' disease carriers, indicating a common ancestry with these carriers (Fig. 5). The grouping of the hydrogenosomal protein Hmp31 with the PECA protein might suggest a peroxisomal nature for this protein. However, the common ancestral node with the exclusively mitochondrial AAC and Graves' disease carriers, together with the presence of the carrier signature sequence in all three repeats of the hydrogenosomal protein, points more towards a mitochondrial nature (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the PECA protein is synthesized with an N-terminal extension of 193 amino acids, which is not present in either the T. vaginalis protein or the mitochondrial AACs and Graves' disease carriers.

FIG. 5.

Phylogenetic analysis of Hmp31. A maximum-parsimony analysis using PAUP (48) was performed to display the relationship between the hydrogenosomal membrane protein Hmp31 and representative members of MCFs. The topology of the tree was identical to that obtained from the Fitch-Margoliash distance method (9). Bootstrap values for the maximum-parsimony analysis are given in percentages at each branch node. The bootstrap values from the distance (FM) tree are displayed where they differ from the maximum-parsimony (MP) tree. The organelles to which the proteins localize are indicated in brackets next to the protein name: H, hydrogenosome; M, mitochondrion; and P, peroxisome. Accession numbers of proteins from top to bottom are AF216971, AF004161, P18239, X15712, AF049130, P12236, S51132, P16260, 016261, AJ223983, Y11220, P55851, S44091, Q02978, Y08499, AF062383, P40614, B53737, P10566, P23500, P21245, AF002109, X87417, Q01356, P38152, and P53007.

Conservation of charge-pair network residues indicates that Hmp31 is a homologue of the mitochondrial AAC.

The Hmp31 protein shows 26% identity and 44% similarity with the most extensively studied MCF member, AAC2 of S. cerevisiae. In addition to the conserved motifs discussed above, Hmp31 contains charge-pair networks (Fig. 6) which have been found to be essential for AAC function in yeast (33, 34). Of the 12 residues in the charge-pair networks, 7 are identical in the hydrogenosomal MCF-like protein, 4 have conserved charge substitutions, and 1 has an opposite charge. Six of the conserved residues appear to be AAC specific (33), including the positive charges on the arginine cluster at positions 252 to 254 in the yeast sequence which are thought to interact with the negative charges on the phosphate group of ATP on the matrix-facing side of the membrane. The motif RRRMMM, found in all the AACs characterized to date, is highly conserved in the hydrogenosomal Hmp31 sequence RKRMML except for a positive charge substitution and a nonpolar substitution. This level of conservation drops in the PECA protein and in Graves' disease carriers, where the sequences at this position are RTRMQA and RRRMQL, respectively. Similarities in these key motifs provide strong evidence that the Hmp31 protein is a functional homologue of the mitochondrial AAC. Moreover, the AAC is the most abundant protein in the mitochondrial membrane (20), paralleling the high levels of Hmp31 in hydrogenosomal membranes (Fig. 1A).

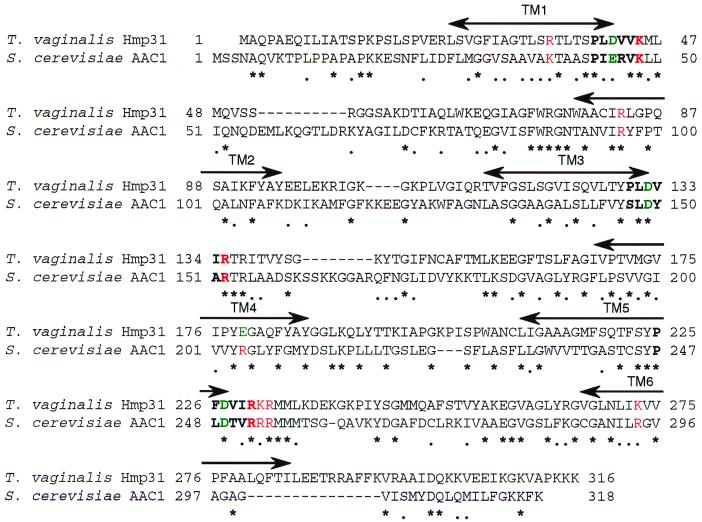

FIG. 6.

Alignment of Hmp31 with S. cerevisiae AAC2. Identities are indicated by an asterisk (∗) and conserved substitutions by a dot (•). Sequences in boldface correspond to the MCF degenerate signature sequence P (Hy) (D,E) X X (K, R). Essential charge-pair network residues in AAC2 (33, 34) and their counterparts in the hydrogenosomal protein are indicated in color: positive charges are shown in red and negative charges are shown in green. Charges are conserved at all positions except for residue E179 in the hydrogenosomal protein aligning with R204, resulting in an opposite charge at this position. The horizontal arrowed lines show putative transmembrane domains TM1 to TM6.

Import of the yeast AAC into hydrogenosomes in vivo.

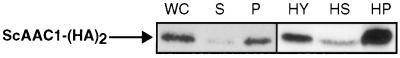

Given the similarity between the hydrogenosomal and mitochondrial AAC membrane proteins, we examined whether the yeast mitochondrial AAC could be targeted to hydrogenosomes in vivo. We transformed T. vaginalis cells with a ScAAC1-(HA)2 construct for expression of C-terminal HA-tagged yeast AAC1 (Fig. 7). The mitochondrial AAC was very efficiently targeted to the organelle fraction (91% in the organelle pellet and 9% in the soluble cellular fraction). Within the hydrogenosomes, 87% of the translocated fusion protein was present in the membrane fraction and 13% was present in the soluble fraction. We have obtained similar results using in vitro translocation of radiolabelled AAC1 into isolated hydrogenosomes, followed by protease treatment (data not shown). These studies, the first to examine translocation of proteins to hydrogenosomal membranes, show that a hydrogenosomal and a mitochondrial membrane protein are targeted with similar efficiencies. Moreover, they strongly indicate that the hydrogenosomal translocation machinery can recognize a membrane-targeting signal on yeast AAC and can correctly direct this heterologous protein to the membrane.

FIG. 7.

Expression and translocation of epitope-tagged yeast AAC1 in T. vaginalis. S. cerevisiae AAC1 is imported into T. vaginalis hydrogenosomes in vivo. Western analysis of fractions from the ScAAC1-(HA)2 in vivo transformant with anti-HA antibody. WC, whole cell; S, soluble cellular fraction; P, crude pelleted organelles. Equivalent amounts of each fraction were loaded on the gels so that WC = S + P. HY, purified hydrogenosomes; HS, soluble organellar fraction; HP, insoluble membrane pellet from sodium carbonate extracted hydrogenosomes. Equivalent amounts of soluble and insoluble fractions were loaded so that HY = HS + HP.

Import of hydrogenosomal AAC into isolated mitochondria in vitro.

Conversely, we tested whether the hydrogenosomal AAC protein, Hmp31, can be correctly targeted to yeast mitochondria in vitro. We found that radiolabelled Hmp31 was translocated into isolated yeast mitochondria in a membrane potential-dependent manner, as was the mitochondrial AAC (39). As described above for translocation of hydrogenosomal and yeast AAC into hydrogenosomes, both proteins were specifically inserted into the mitochondrial membrane (Fig. 8A). Depletion of the membrane potential resulted in a reduction in the amount of protease-protected, membrane-inserted T. vaginalis Hmp31, in accordance with the pathway taken by the mitochondrial AAC (39).

FIG. 8.

The T. vaginalis Hmp31 protein is imported into isolated yeast mitochondria in vitro. (A) Radiolabelled T. vaginalis Hmp31 and S. cerevisiae AAC1 were incubated for 1, 2, and 4 min at 25°C with yeast wild-type (WT) and tim10-1 mutant mitochondria (21) in the presence (+) or absence (−) of a membrane potential (ΔΨ). Following trypsin treatment, the organelles were reisolated and subjected to sodium carbonate extraction. The fractions were then separated by SDS-PAGE, followed by fluorography. STD, 10% of the radiolabelled precursor present in each assay. (B) Quantitation of Hmp31 import data shown in panel A. The densitometer reading at the 4-min time point was set at 100%.

A new import pathway has been defined in yeast mitochondria, which is specific for inner membrane proteins. The intermembrane space proteins Tim9 and Tim10 mediate import of the carrier proteins (1, 21, 22, 45). To address whether this pathway might be conserved between hydrogenosomes and mitochondria, we investigated the requirement for a functional Tim10 protein in the import of Hmp31 into yeast mitochondria using temperature-sensitive tim10-1 mutant mitochondria (Fig. 8A). In the case of Hmp31, the efficiency of import in vitro in tim10-1 mitochondria dropped by 83% relative to wild-type mitochondria (Fig. 8B). This is comparable to the effect of the tim10-1 mutation on the efficiency of import of S. cerevisiae AAC (Fig. 8A and data not shown), which is reduced by 85 to 99% at steady state (21). Hence, these translocation data show, first, that there is a common inner-membrane-targeting signal between the hydrogenosomal carrier and the mitochondrial carriers. Second, the import deficiency seen in the tim10-1 mutant suggests that an intermembrane space pathway similar to that defined in mitochondria (19, 21, 36, 45) may be used to translocate membrane proteins in hydrogenosomes.

DISCUSSION

We have identified and characterized the first membrane protein from hydrogenosomes and found that it is phylogenetically related to the mitochondrial carrier family of proteins. Specifically, this protein is a homologue of the mitochondrial ADP-ATP carrier, an inner-membrane component that exchanges ADP and ATP between the cytosol and the organelle. Like the mitochondrial AAC, Hmp31 is one of the most abundant membrane proteins of hydrogenosomes. We have established a system to study targeting of proteins to hydrogenosomes in vivo and have shown that the hydrogenosomal AAC contains an N-terminal, cleavable presequence; however, this sequence is not necessary for translocation of the protein into hydrogenosomes. These data indicate that internal sequences are used to target hydrogenosomal membrane carriers, similar to that known for targeting mitochondrial carriers (38, 46). Our results also demonstrate that the translocation machinery of hydrogenosomes can effectively recognize and target a mitochondrial AAC. Conversely, we have shown that the hydrogenosomal AAC homologue can be targeted to mitochondrial membranes in vitro utilizing the same pathway used for assembly of mitochondrial inner-membrane carrier proteins (19, 21, 26, 39, 43, 45). This compatibility in the translocation machinery in the two organelles is quite remarkable given the biochemical differences between hydrogenosomes and mitochondria.

We have shown that the mature Hmp31 protein, lacking the presequence, is translocation competent. Unlike Hmp31, however, the majority of MCF proteins do not possess an N-terminal cleavable targeting sequence. Two notable exceptions are the plant AACs and mammalian phosphate carriers (35). In plants, the AACs are synthesized with long N-terminal presequences (12) which have been found not to be necessary for translocation (30, 52). Although the Hmp31 presequence is shorter than those on plant AACs, it has an amino acid composition similar to that of the N-terminal extremity of plant AAC presequences. The latter generally start with a Met-Ala dipeptide, are enriched in the amino acids glutamine and alanine, and likewise have a negatively charged amino acid residue (12).

The other MCF proteins that bear a cleavable N-terminal presequence, the mammalian phosphate carriers, are synthesized with an extension of 44 to 49 amino acids. In this case, deletion of the presequence still results in an import competent protein; however, efficiency is reduced to 40 to 50% of normal. Thus, although the presequence is not necessary for translocation, it probably has a role in enhancing import efficiency. It was further observed that the presequence alone was able to target a passenger protein into mitochondria, albeit at a very low efficiency. The mitochondrial phosphate carriers therefore seem to have multiple targeting signals (53). These comparisons reveal a similarity between import signals on membrane proteins of mitochondria and hydrogenosomes. Both appear to rely upon internal membrane-targeting signals; however, when present, a cleavable N-terminal presequence also appears to be capable of restoring translocation of proteins to the organelles.

We have demonstrated that the addition of a matrix-targeting signal to the N terminus of Hmp31 that lacks its own presequence does not cause mistargeting to the matrix, indicating that the matrix-targeting signal is not capable of overriding the internal membrane signal. A similar experiment was done in mitochondria using the presequence of preornithine carbamyltransferase, a matrix protein, fused to the mitochondrial uncoupling protein, an inner-membrane protein of the MCF which normally lacks a presequence. In this case, the chimeric protein was translocated across the inner membrane into the matrix, where the matrix presequence was cleaved and the protein was not inserted into the membrane (28). These results indicate that the membrane-targeting signal on the uncoupling protein can be overridden by the matrix-targeting signal, contrary to our observations using a chimeric construct consisting of a matrix presequence fused to Hmp31.

Translocation of mitochondrial inner-membrane proteins, such as the AAC and the Tim components, follows a different import pathway than that of proteins destined for the mitochondrial matrix (19, 21, 26, 39, 43, 45). After passing through the Tom complex, these precursor proteins are assisted by a family of small Tim proteins, Tim8, Tim9, Tim10, and Tim13, which guide the precursors through the intermembrane space to inner-membrane translocase complexes that mediate membrane insertion. We have shown that hydrogenosomal AAC is imported efficiently into yeast mitochondria and that its import requires the Tim9-Tim10 complex as does mitochondrial AAC. These data indicate that the import pathway used for inner-membrane proteins is conserved between hydrogenosomes and mitochondria. We have also demonstrated that yeast mitochondrial AAC is translocated efficiently into hydrogenosomes, providing additional evidence for a conservation of the import pathway for inner-membrane proteins. One would therefore predict that homologues of the Tim proteins are present in hydrogenosomes. Our data also indicate that a common inner-membrane-targeting signal for MCF proteins is used by the two organelles. Specific targeting sequences have not been identified for mitochondrial inner-membrane proteins; however, deletion studies of yeast AAC indicate that the targeting information is internal and occurs in two distinct parts of the protein (38, 46).

Previous studies have shown that the matrix-targeting pathway is conserved between hydrogenosomes and mitochondria (4, 15, 50). Taken together with our current studies on the translocation of proteins into the membranes of hydrogenosomes, it can be concluded that both matrix and membrane-targeting pathways are far more similar than is reasonable to predict if these two organelles were to have had independent origins.

Current phylogenetic analyses support the theory that the mitochondrion originated from an endosymbiotic ancestor related to the contemporary members of the α-proteobacteria (14). The debate over the origins of the hydrogenosome and of the mitochondrion basically involves two possibilities: either the two organelles evolved from two independent symbioses of related α-proteobacteria, or there was one common bacterial ancestor that subsequently diverged into the specific organelles.

Phylogenetic analyses of heat shock proteins in hydrogenosome-containing T. vaginalis (5, 11, 16, 41) as well as in Giardia lamblia (42) and Entamoeba histolytica (7), two eukaryotes that harbor neither organelle but appear to have lost mitochondria secondarily, indicate that these proteins are closely related to mitochondrial heat shock proteins. These findings, however, are still compatible with independent symbioses of two related proteobacteria (47) bearing similar heat shock proteins, which are indeed still conserved in their modern-day relatives. On the other hand, the MCF proteins have no known proteobacterial or archaebacterial homologues, and statistical analyses of the MCF repeat units have indicated that the tripartite proteins have evolved from the triplication of an ancestral gene around the time mitochondria first appeared in eukaryotes (23) before diverging into the various specific solute carriers. Hence, the origin of these MCF proteins appears to be closely associated with the symbiotic event that gave rise to the mitochondrion. It seems unlikely that such a triplication event occurred independently in different progenitors of mitochondria and hydrogenosomes, to give rise to the mitochondrial carrier proteins in the former case and to Hmp31 in the latter case. Moreover, mitochondrial AAC proteins are phylogenetically unrelated to the ADP-ATP translocators of Rickettsia, the microbe which is most closely related to mitochondria (3). This implies that the event which gave rise to mitochondrial AAC is different from that in which the mitochondria as a whole originated (2).

Therefore, the results presented here, showing the presence of a mitochondrial-type membrane carrier protein in hydrogenosomes and a compatible translocation mechanism for targeting membrane proteins into both organelles, provide unequivocal evidence that the two organelles originated from a common progenitor organelle. This does not, however, preclude the possibility that later symbioses delivered specific proteins to the two organelles after their divergence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Miriam Makabi for technical assistance, Harry Hahn for help with the phylogeny programs, and Gottfried Schatz, James Lake, Alexander van der Bliek, and members of our laboratory for helpful advice and critical comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI27857 to P.J.J., postdoctoral fellowships from the Damon Runyon-Walter Winchell Cancer Research Foundation and the National Science Foundation to C.M.K. and from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to E.P., and a predoctoral training grant (NIH AI07323) to P.J.B. P.J.J. is a recipient of a Burroughs-Wellcome Scholar in Molecular Parasitology award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adam A, Endres M, Sirrenberg C, Lottspeich F, Neupert W, Brunner M. Tim9, a new component of the TIM22.54 translocase in mitochondria. EMBO J. 1999;18:313–319. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.2.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson S G E, Kurland C G. Origins of mitochondria and hydrogenosomes. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:535–541. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)00013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson S G E, Zomorodipour A, Andersson J P, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Alsmark U C M, Podowski R M, Naslund A K, Eriksson A-S, Winkler H H, Kurland C G. The genome sequence of Rickettsia prowazekii and the origin of mitochondria. Nature. 1998;396:133–140. doi: 10.1038/24094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley P J, Lahti C J, Plümper E, Johnson P J. Targeting and translocation of proteins into the hydrogenosome of the protist Trichomonas: similarities with mitochondrial protein import. EMBO J. 1997;16:3484–3493. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bui E T N, Bradley P J, Johnson P J. A common evolutionary origin for mitochondria and hydrogenosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9651–9656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavalier-Smith T. The simultaneous symbiotic origin of mitochondria, chloroplasts, and microbodies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1987;503:55–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb40597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark C G, Roger A J. Direct evidence for secondary loss of mitochondria in Entamoeba histolytica. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6518–6521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delgadillo M G, Liston D R, Niazi K, Johnson P J. Transient and selectable transformation of the parasitic protist Trichomonas vaginalis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4716–4720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP—phylogeny inference package, version 3.57c. Seattle: University of Washington; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujiki Y, Hubbard A L, Fowler S, Lazarow P B. Isolation of intracellular membranes by means of sodium carbonate treatment: application to endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol. 1982;93:97–102. doi: 10.1083/jcb.93.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Germot A, Philippe H, Le Guyader H. Presence of a mitochondrial-type 70-kDa heat shock protein in Trichomonas vaginalis suggests a very early mitochondrial endosymbiosis in eukaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14614–14617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glaser E, Sjöling S, Tanudji M, Whelan J. Mitochondrial protein import in plants. Signals, sorting, targeting, processing and regulation. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;38:311–338. doi: 10.1023/a:1006020208140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glick B S, Pon L A. Isolation of highly purified mitochondria from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 1995;260:213–223. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)60139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray M W, Burger G, Lang B F. Mitochondrial evolution. Science. 1999;283:1476–1481. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hausler T, Stierhof Y D, Blattner J, Clayton C. Conservation of mitochondrial targeting sequence function in mitochondrial and hydrogenosomal proteins from the early-branching eukaryotes Crithidia, Trypanosoma and Trichomonas. Eur J Cell Biol. 1997;73:240–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horner D S, Hirt R P, Kilvington S, Lloyd D, Embley T M. Molecular data suggest an early acquisition of the mitochondrion endosymbiont. Proc R Soc Lond Series B Biol Sci. 1996;263:1053–1059. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1996.0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson P J, Bradley P J, Lahti C J. Cell biology of trichomonads: protein targeting to the hydrogenosome. In: Boothroyd J C, Komuniecki R, editors. Molecular approaches to parasitology. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Liss, Inc.; 1995. pp. 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson P J, d'Oliveira C E, Gorrell T E, Müller M. Molecular analysis of the hydrogenosomal ferredoxin of the anaerobic protist Trichomonas vaginalis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6097–6101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerscher O, Holder J, Srinivasan M, Leung R S, Jensen R E. The Tim54p-Tim22p complex mediates insertion of proteins into the mitochondrial inner membrane. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1663–1675. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.7.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klingenberg M. The enzymes of biological membranes. 3. Membrane transport. New York, N.Y: Plenum Publishing Corp.; 1976. pp. 383–438. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koehler C M, Jarosch E, Tokatlidis K, Schmid K, Schweyen R J, Schatz G. Import of mitochondrial carriers mediated by essential proteins of the intermembrane space. Science. 1998;279:369–373. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koehler C M, Merchant S, Oppliger W, Schmid K, Jarosch E, Dolfini L, Junne T, Schatz G, Tokatlidis K. Tim9p, an essential partner subunit of Tim10p for the import of mitochondrial carrier proteins. EMBO J. 1998;17:6477–6486. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuan J, Saier M H., Jr The mitochondrial carrier family of transport proteins: structural, functional, and evolutionary relationships. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1993;28:209–233. doi: 10.3109/10409239309086795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lahti C J, d'Oliveira C E, Johnson P J. β-succinyl CoA synthetase from Trichomonas vaginalis is a soluble hydrogenosomal protein with an amino-terminal sequence that resembles mitochondrial presequences. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6822–6830. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.21.6822-6830.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lahti C J, Johnson P J. Trichomonas vaginalis hydrogenosomal proteins are synthesized on free polyribosomes and may undergo processing upon maturation. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;46:307–310. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90055-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leuenberger D, Bally N A, Schatz G, Koehler C M. Different import pathways through the mitochondrial intermembrane space for inner membrane proteins. EMBO J. 1999;18:4816–4822. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liston D R, Johnson P J. Analysis of a ubiquitous promoter element in a primitive eukaryote: early evolution of the initiator element. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2380–2388. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu X Q, Freeman K B, Shore G C. An amino-terminal signal sequence abrogates the intrinsic membrane-targeting information of mitochondrial uncoupling protein. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin W, Müller M. The hydrogen hypothesis for the first eukaryote. Nature. 1998;392:37–41. doi: 10.1038/32096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mozo T, Fischer K, Flugge U I, Schmitz U K. The N-terminal extension of the ADP/ATP translocator is not involved in targeting to plant mitochondria in vivo. Plant J. 1995;7:1015–1020. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.07061015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Müller M. The hydrogenosome. In: Gooday G W, Lloyd D, Trinci A P J, editors. The eukaryotic microbial cell. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Müller M. The hydrogenosome. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:2879–2889. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-12-2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson D R, Felix C M, Swanson J M. Highly conserved charge-pair networks in the mitochondrial carrier family. J Mol Biol. 1998;277:285–308. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson D R, Lawson J E, Klingenberg M, Douglas M G. Site-directed mutagenesis of the yeast mitochondrial ADP/ATP translocator. Six arginines and one lysine are essential. J Mol Biol. 1993;230:1159–1170. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neupert W. Protein import into mitochondria. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:863–917. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pfanner N. Mitochondrial import: crossing the aqueous intermembrane space. Curr Biol. 1998;8:R262–R265. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfanner N, Craig E A, Hönlinger A. Mitochondrial preprotein translocase. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:25–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfanner N, Hoeben P, Tropschug M, Neupert W. The carboxyl-terminal two-thirds of the ADP/ATP carrier polypeptide contains sufficient information to direct translocation into mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:14851–14854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pfanner N, Neupert W. Distinct steps in the import of ADP/ATP carrier into mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:7528–7536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plümper E, Bradley P J, Johnson P J. Implications of protein import on the origin of hydrogenosomes. Protist. 1998;149:303–311. doi: 10.1016/S1434-4610(98)70037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roger A J, Clark C G, Doolittle W F. A possible mitochondrial gene in the early-branching amitochondriate protist Trichomonas vaginalis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14618–14622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roger A J, Svärd S G, Tovar J, Clark C G, Smith M W, Gillin F D, Sogin M L. A mitochondrial-like chaperonin 60 gene in Giardia lamblia: evidence that diplomonads once harbored an endosymbiont related to the progenitor of mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:229–234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryan M T, Pfanner N. The preprotein translocase of the mitochondrial outer membrane. Biol Chem. 1998;379:289–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saraste M, Walker J E. Internal sequence repeats and the path of polypeptide in mitochondrial ADP/ATP translocase. FEBS Lett. 1982;144:250–254. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(82)80648-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sirrenberg C, Endres M, Fölsch H, Stuart R A, Neupert W, Brunner M. Carrier protein import into mitochondria mediated by the intermembrane proteins Tim10/Mrs11 and Tim12/Mrs5. Nature. 1998;391:912–915. doi: 10.1038/36136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smagula C S, Douglas M G. ADP-ATP carrier of Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains a mitochondrial import signal between amino acids 72 and 111. J Cell Biochem. 1988;36:323–327. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240360402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sogin M. History assignment: when was the mitochondrion founded? Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:792–799. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swofford D L. PAUP: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony, version 4.0. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van der Giezen M, Kiel J A, Sjollema K A, Prins R A. The hydrogenosomal malic enzyme from the anaerobic fungus Neocallimastix frontalis is targeted to mitochondria of the methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha. Curr Genet. 1998;33:131–135. doi: 10.1007/s002940050318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weber F E, Minestrini G, Dyer J H, Werder M, Boffelli D, Compassi S, Wehrli E, Thomas R M, Schulthess G, Hauser H. Molecular cloning of a peroxisomal Ca2+-dependent member of the mitochondrial carrier superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8509–8514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winning B M, Sarah C J, Purdue P E, Day C D, Leaver C J. The adenine nucleotide translocator of higher plants is synthesized as a large precursor that is processed upon import into mitochondria. Plant J. 1992;2:763–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zara V, Palmieri F, Mahlke K, Pfanner N. The cleavable presequence is not essential for import and assembly of the phosphate carrier of mammalian mitochondria but enhances the specificity and efficiency of import. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:12077–12081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]