Abstract

It is proposed that the lytB gene encodes an enzyme of the deoxyxylulose-5-phosphate (DOXP) pathway that catalyzes a step at or subsequent to the point at which the pathway branches to form isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP). A mutant of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis strain PCC 6803 with an insertion in the promoter region of lytB grew slowly and produced greenish-yellow, easily bleached colonies. Insertions in the coding region of lytB were lethal. Supplementation of the culture medium with the alcohol analogues of IPP and DMAPP (3-methyl-3-buten-1-ol and 3-methyl-2-buten-1-ol) completely alleviated the growth impairment of the mutant. The Synechocystis lytB gene and a lytB cDNA from the flowering plant Adonis aestivalis were each found to significantly enhance accumulation of carotenoids in Escherichia coli engineered to produce these colored isoprenoid compounds. When combined with a cDNA encoding deoxyxylulose-5-phosphate synthase (dxs), the initial enzyme of the DOXP pathway, the individual salutary effects of lytB and dxs were multiplied. In contrast, the combination of lytB and a cDNA encoding IPP isomerase (ipi) was no more effective in enhancing carotenoid accumulation than ipi alone, indicating that the ratio of IPP and DMAPP produced via the DOXP pathway is influenced by LytB.

The more than twenty thousand isoprenoids so far identified (4) include an incredible variety of essential and secondary compounds, such as carotenoids, cholesterol, rubber, dolichols, the side chains of quinones, the phytol tail of chlorophylls, and the prenyl groups of prenylated proteins and isopentenylated tRNAs. The biosynthesis of all isoprenoids begins with one or both of the two C5 building blocks of the pathway: isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP). In animals, fungi, and certain bacteria, the synthesis of IPP occurs via the well-known mevalonate (MVA) pathway that begins with acetyl coenzyme A (CoA) and proceeds via hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA and MVA (16). DMAPP is then derived from IPP through the action of an IPP isomerase (IPI) enzyme (35).

In plant chloroplasts, algae, cyanobacteria, and many other bacteria, an alternative or nonmevalonate pathway, now known as the deoxyxylulose-5-phosphate (DOXP) pathway, serves to produce the isoprenoid precursors IPP and DMAPP (12, 28, 40). This pathway, illustrated for Escherichia coli in Fig. 1, utilizes pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate as the initial precursors rather than acetyl-CoA. The first two steps of the DOXP pathway, leading to the compound 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate (MEP), are catalyzed by the enzymes deoxyxylulose-5-phosphate synthase (DXS) (29, 45) and deoxyxylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR) (48). Several subsequent reactions, the order of which is not yet certain, are catalyzed by products of the ygbB, ygbP, and ychB genes (21, 26, 30, 39).

FIG. 1.

The DOXP pathway for biosynthesis of the isoprenoid precursors IPP and DMAPP in E. coli. Gene products implicated in the pathway are boxed. The order of the reactions catalyzed by the products of ygbB, ygbP, and ychB is uncertain. Later reaction steps in the pathway remain to be determined. Note that a gene encoding IPI, although present in E. coli, is not routinely found in organisms that utilize the DOXP pathway (Table 1). The plasmid pAC-LYC (10), shown to the lower right, encodes enzymes (products of the crtE, crtB, and crtI genes) that lead to the synthesis of the pink isoprenoid lycopene from IPP and DMAPP. Cm, chloramphenicol resistance gene; G-3-P, d-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; GAPD, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Recent evidence (1, 5, 14, 33, 38) indicates that, in contrast to the MVA pathway, the DOXP pathway branches and separately produces DMAPP and IPP. Although E. coli contains an isomerase activity, this activity is low (14, 18), the ipi gene in this bacterium is dispensable (18), and ipi is, in any case, not present in the genomes of many bacteria with the DOXP pathway (Table 1). Synechocystis strain PCC 6803, for example, lacks a homologue of ipi (Table 1), and cell extracts of this cyanobacterium and of Synechococcus strain PCC 7942 are devoid of isomerase activity (14).

TABLE 1.

Occurrence of known and prospective isoprenoid pathway genes in members of the Bacteria, Archaea, and Eucaryota

| Genea |

Bacteria

|

Archaea

|

Eucaryota

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aquifex aeolicus | Synechocystis strain PCC 6803 | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Bacillus subtilis | Mycoplasma genitalium | Mycoplasma pneumoniae | Ureaplasma urealyticum | Chlamydia pneumoniae | Chlamydia trachomatis | Rickettsia prowazekii | Neisseria meningitidis | Campylobacter jejuni | Helicobacter pylori | Haemophilus influenzae | Escherichia coli | Borrelia burgdorferi | Treponema pallidum | Thermatoga maritina | Deinococcus radiodurans | Aeropyrum pernix | Archaeoglobus fulgidus | Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum | Methanococcus jannaschii | Pyrococcus abyssi | Pyrococcus horikoshii | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Arabidopsis thaliana | Homo sapiens | |

| dxs | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| dxr | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| ygbB | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| ygbP | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| ychB | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| lytBb | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| gcpEb | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| ipi | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| hmgr | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||

| mvk | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||

| pmk | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| mvd | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

mvk, mevalonate kinase gene; pmk, phosphomevalonate kinase gene; mvd, mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase gene.

Genes of unknown function with a genomic distribution consistent with a role in the DOXP pathway.

The terminal reaction steps in the DOXP pathway have not yet been established. To identify genes that might encode enzymes that catalyze these later reactions, we took two different and complementary approaches. First, the occurrence of the known DOXP pathway genes in 28 completely sequenced bacterial genomes and in yeast, humans, and the green plant Arabidopsis thaliana was ascertained, and genes that exhibited the same pattern of occurrence were identified. Second, we screened bacterial genomic libraries and plant cDNA libraries for genes or cDNAs that increased the accumulation of a colored “reporter” isoprenoid compound, lycopene, in Escherichia coli engineered to produce this pink carotenoid. Common to both the correlative (genomic occurrence) and functional (lycopene enhancement) screening approaches was the identification of homologues of the E. coli lytB gene as prospective DOXP pathway genes. Experimental evidence of a role for LytB in the DOXP pathway is presented.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genomic analysis.

The occurrence of homologues of known DOXP and MVA pathway genes within 28 sequenced bacterial genomes and in Saccharomyces cerevisiae was determined by using the default parameters for creation of homologous gene tables at the Microbial Genome Database for Comparative Analysis (http://mbgd.genome.ad.jp/). For a few genomes in which the ygbP gene is fused to the ygbB gene, both genes were considered to be present. Because results were identical for sequenced genomes of two different strains of Chlamydia trachomatis, Helicobacter pylori, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, each species is listed only once in the tabulated results (Table 1). The occurrence of DOXP pathway gene homologues in A. thaliana and in humans was determined by searching the protein, nucleotide, and expressed sequence tag (EST) databases at GenBank by using the same significance thresholds as for the microbial database.

Cell strains and culture.

Escherichia coli strains XL1-Blue MRF′ (Stratagene Cloning Systems, La Jolla, Calif.) and Top10 (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, Calif.) were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 28°C in darkness on a platform shaker at 225 cycles per min. Cultures grown on solid media (1.5% [wt/vol] Difco Bacto agar) were incubated at room temperature (ca. 22°C) in darkness. The growth media were supplemented, as appropriate, with 150 μg of ampicillin (sodium salt) per ml, 30 μg of chloramphenicol per ml, and/or 30 μg of kanamycin sulfate per ml.

Cultures of Synechocystis strain PCC 6803, obtained from Wim Vermaas (Arizona State University, Tempe) were grown at 30°C in liquid BG-11 medium (36) containing 5 mM TES [N-tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid]-KOH (pH 8.2). For agar plates (1.5% [wt/vol] Difco Bacto agar), 0.3% sodium thiosulfate and 10 mM TES-KOH (pH 8.2) were included in the medium (49). The growth media were supplemented as needed with kanamycin sulfate, 3-methyl-3-buten-1-ol (Fluka 66095; Fluka Chemical Corporation, Milwaukee, Wis.), and/or 3-methyl-2-buten-1-ol (Fluka 66093). Agar plates and liquid cultures were continuously illuminated with 20 μE provided by fluorescent lamps (alternating tubes of GE cool white and Philips agro), with cheesecloth used to reduce the irradiance to the desired level.

Disruption of the Synechocystis strain PCC 6803 lytB gene.

Genomic DNA was prepared from cells of Synechocystis strain PCC 6803 as previously described (49). PCR primers lytB6803N (ATT GCC CCT GGG TAC AAG AC) and lytB6803C (TCA AGG CAG TGA CCA AGA AAC) were designed to amplify the lytB gene and flanking DNA of Synechocystis strain PCC 6803 (23). PCR primers EclytBN (CAC CTT CAA CCT TGC CGA TAC) and EclytBC (ACC GGC ATT TTC GCA TAA CT) were designed to amplify the E. coli lytB gene along with the preceding slpA gene and the two promoters that immediately precede slpA. PCR was performed with an MJ Research (Waltham, Mass.) PTC-150-25 MiniCycler with a heated lid and in-sample temperature probe. The Advantage KlenTaq polymerase mix (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.) was used with a reaction volume of 50 μl in 100-μl thin-wall tubes. An initial denaturation at 94°C for 1 min was followed by 10 cycles of 94, 60, and 68°C for 10, 60, and 150 s, respectively, and then 20 to 25 more cycles with an additional 10 s added to the extension time with each new cycle. The PCR products of the expected size (2.5 kb for the Synechocystis lytB) (Fig. 2) were purified by electrophoresis in a 1% (wt/vol) agarose gel, recovered by using the Geneclean kit (Bio 101, Inc., Carlsbad, Calif.) and cloned in the plasmid vector pSTBlue1 (Novagen, Inc., Madison, Wis.). A 2.2-kb fragment containing Synechocystis lytB was excised with the BamHI and SmaI sites contained within the genomic PCR product and inserted into the BamHI and Klenow-blunted HindIII sites of pTrcHisA (Invitrogen) and in the BamHI and EcoRV sites of pBluescript SK− (Stratagene) to yield p6803lytBTrcA and p6803lytBSK. Digestion of p6803lytBTrcA with BamHI and HindIII, filling in of the ends with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase, and ligation to recircularize yielded plasmid p6803lytBfus, in which the lytB of Synechocystis was fused in frame to a small peptide under the control of the strong Trc promoter.

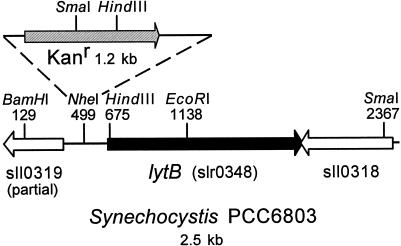

FIG. 2.

Schematic illustration of Synechocystis strain PCC 6803 genomic DNA encompassing the lytB gene. A kanamycin resistance gene (Kanr) was inserted into the NheI site immediately upstream of the lytB gene.

The kanamycin resistance gene from Tn903 was excised from plasmid pBR329K (3) with PstI, the ends were made blunt with mung bean nuclease, and the Kanr gene was inserted into the blunted HindIII site near the beginning of the lytB gene (Fig. 2) in p6803lytBTrcA, into the blunted EcoRI site in the lytB gene in p6803lytBSK, and into the blunted NheI site upstream of lytB in p6803lytBSK. After transformation of E. coli and selection of the appropriate transformants, plasmid minipreps were prepared (11). The plasmids were linearized by digestion with BamHI, the reaction mixtures were extracted twice with phenol and then once with CHCl3, and the DNA was precipitated with sodium acetate and ethanol (42), washed with ice-cold 70% ethanol, and resuspended in sterile Tris-EDTA buffer. Transformation of Synechocystis strain PCC 6803 was performed as described by Williams (49), except that the concentrated cultures were grown for 24 h after addition of the transforming DNA and spread directly on BG-11 agar plates supplemented with 10 μg of kanamycin sulfate per ml. Colonies appearing on these plates were streaked onto plates with 25 μM kanamycin, and colonies arising on these plates were streaked, in turn, on plates containing 50 μM kanamycin.

Library construction and screening.

A unidirectional cDNA library in lambda ZAPII, using mRNA isolated from immature and developing flower buds of Adonis aestivalis (pheasant's eye), was constructed (by Stratagene) with EcoRI and XhoI adapters. The library was excised en masse to produce a phagemid library (according to the manufacturer's instructions), which was then introduced into E. coli strain XL1-Blue MRF′ that had been engineered to accumulate the pink carotenoid lycopene (10). Transfected cultures were spread on LB agar plates to yield a density of ca. 2,000 to 10,000 colonies per large petri plate (150 mm in diameter and containing ca. 100 ml of growth medium). Both liquid and solid growth media contained ampicillin to select and maintain transformants and chloramphenicol to maintain the plasmid required for lycopene production (pAC-LYC; Fig. 1) (10). Plates were incubated at room temperature in darkness and examined visually after 2 days and daily thereafter for 7 to 10 days. The rare dark pink colonies observed in the midst of the multitude of paler pink colonies were selected, the library plasmids within the cells of these colonies were recovered, and the sequences of the cDNA inserts were determined. Full details of the screening protocol are given elsewhere (9, 10).

A related approach to identification of prospective isoprenoid pathway genes has been described by Hemmi et al. (20), who mapped mutations that reduced lycopene accumulation in E. coli to 29 loci. Although ipi was found in this screen, lytB, gcpE, and dxs were not among the prospective isoprenoid pathway genes identified this way.

Plasmids and plasmid constructs.

A 0.85-kb KpnI-EcoRI fragment containing most of the Arabidopsis ipi cDNA (8) was excised from the original library plasmid and ligated in the corresponding sites of plasmid pTrcHisB (Invitrogen). Subsequent digestion with NcoI and XhoI, filling-in with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase, and ligation to recircularize yielded a plasmid in which the coding region of ipi, lacking the first 48 codons, is fused in frame to the strong bacterial Trc promoter and 6 additional codons that specify the amino acids MSRSAA. An EcoRV-KpnI fragment, containing the cDNA and fused Trc promoter, was excised and inserted in the corresponding sites of pBluescript SK− to produce the plasmid pAtipiTrc.

A marigold dxs cDNA in the original cloning vector (pBluescript SK−), here referred to as pTedxs, has already been described (C. P. Moehs, L. Tian, and D. DellaPenna, submitted for publication). An Adonis lytB cDNA (GenBank accession no. AF270978), along with the lacZ promoter immediately upstream of it in the cloning vector (pBluescript SK−), was excised from the original library clone (pAplytB) with PvuII and inserted into the Klenow-blunted SalI site of plasmid pTedxs to yield pdxs/lytB.

An EcoRV-EcoRI fragment containing the Arabidopsis ipi1-Trc promoter fusion (see above) was excised from pAtipiTrc, treated with the Klenow enzyme to blunt the ends, and inserted into the blunted SalI site downstream of the marigold dxs cDNA in pTedxs, in the blunted KpnI site downstream of the Adonis lytB cDNA in pAplytB, and in the blunted XhoI site of pdxs/lytB. The resulting plasmids are referred to as pdxs/ipiTrc, plytB/ipiTrc, and pdxs/lytB/ipiTrc.

Assay of carotenoid accumulation.

Competent cells of lycopene-, β-carotene-, and zeaxanthin-accumulating E. coli strain Top10 (9, 10, 47) were prepared (6) from cultures grown at 28°C in darkness with shaking. After transformation with various plasmids, cells were spread on agar plates with the appropriate selective agents and incubated at room temperature for 2 to 3 days in darkness. Culture tubes containing 5 ml of LB medium (with ampicillin and chloramphenicol) were each inoculated with a single fresh colony, and the cultures were grown for 48 h at 28°C with shaking, conditions previously reported as optimal for carotenoid accumulation in E. coli (41). Two 1.5-ml aliquots from each tube were harvested by centrifugation in microcentrifuge tubes (90 s at maximum speed in an Eppendorf 5415C microcentrifuge). The well-drained pellets were extracted with 1.5 ml of chloroform-methanol (2/1 [vol/vol]) for 3 h in darkness, with occasional gentle mixing by inversion of the tubes. Extracts were clarified by centrifugation for 10 min at maximum speed in the microcentrifuge. The A480.5 (the major peak in the visible region of the absorption spectrum of lycopene) or the A458.5 (the major peak for β-carotene and zeaxanthin) was determined with an accumulation time of 4 s and the slit width set to 4 nm in a Perkin-Elmer lambda 6 spectrophotometer. A650 was also monitored to ensure that the reading at 480.5 (or 458.5) nm was not due to turbidity of the extract. At least 6 (zeaxanthin and β-carotene) or 12 (lycopene) individual transformants were analyzed for each plasmid construct.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The Adonis aestivalis lytB cDNA has been assigned GenBank accession no. AF270978.

RESULTS

The genomic occurrence of known DOXP pathway genes is matched only by lytB and gcpE.

The occurrence of homologues of the known DOXP pathway genes dxs, dxr, ygbB, ygbP, and ychB was determined for 22 bacterial (including the cyanobacterium Synechocystis strain PCC 6803) and 6 archaebacterial genomes for which the complete sequences were available in public databases. Their occurrence in the yeast genome, in the substantially completed Arabidopsis thaliana genome and EST databases, and in the human genome and EST databases was also ascertained. For comparison, the occurrence of four MVA pathway genes and ipi was determined as well. The results of this analysis are displayed in Table 1.

DOXP pathway genes dxs, dxr, and ygbB were present in all but five of the bacteria, in none of the six archaea, and in Arabidopsis, but not in yeast or humans. The ygbP and ychB gene occurrence patterns were similar, but not quite identical to that of these first three. The exact occurrence pattern exhibited by dxs, dxr, and ychB was displayed by only two other genes, both of unknown or uncertain function: lytB and gcpE. An observed co-occurrence of genes in this type of analysis has been found to be a strong predictor of a functional linkage (31, 34). Therefore, lytB and gcpE must be considered strong candidates for the few DOXP pathway genes that remain to be identified.

Alcohol analogues of IPP and DMAPP complement an insertion immediately upstream of Synechocystis lytB.

The lytB gene of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis strain PCC 6803 was obtained by PCR amplification of genomic DNA. A kanamycin resistance gene from Tn903 was inserted into either the EcoRI or HindIII site in the coding region of lytB or the NheI site immediately upstream of the coding region (Fig. 2), and Synechocystis was separately transformed with linearized DNA containing these constructs. Colonies appearing after transformation with constructs containing the Kanr gene in the HindIII or EcoRI sites of lytB were quite small, nearly transparent in appearance, and did not survive restreaking on 25 μM kanamycin plates. Serial restreaking on agar plates containing increasing concentrations of kanamycin (see Materials and Methods) did, however, yield a lytB::Kanr strain with the insertion into the NheI site of all copies of the genome (Fig. 3). Colonies produced by this strain grew slowly on the 50 μM kanamycin plates, were greenish-yellow in color (Fig. 4, upper panel), and eventually became bleached despite a relatively low light regimen (20 μE of continuous white light).

FIG. 3.

PCR amplification of lytB in Synechocystis PCC6803 using genomic DNA obtained from the wild-type strain and from a mutant with a Kanr insertion in the NheI site immediately upstream of lytB. The ca. 3.7-kb PCR product from the insertion mutant lytB(NheI)::Kanr, displayed in the right lane of this 1% agarose gel, is the expected 1.2 kb larger than the wild-type product of about 2.5 kb (middle lane). No trace of the wild-type (i.e., uninterrupted) gene is discernable in the mutant lane. The PCR primers were those used for the initial amplification of lytB and flanking regions (see Fig. 2 and Materials and Methods) and lie outside the BamHI and SmaI sites that define the cloned DNA fragment used to transform Synechocystis. The standards lane (left lane) contains DNA fragments of the indicated sizes.

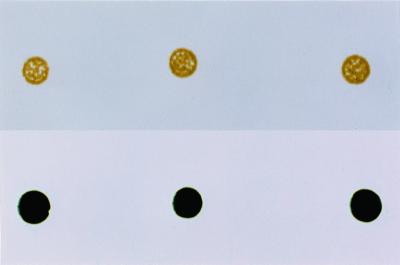

FIG. 4.

Impaired growth of Synechocystis strain PCC 6803 lytB(NheI)::Kanr mutant strain on BG-11 agar plates containing 50 μg of kanamycin per ml (upper panel) is much improved by supplementation of the growth medium with 2.5 mM (each) 3-methyl-3-buten-1-ol and 3-methyl-2-buten-1-ol (lower panel). The dark blue-green color of the colonies in the lower panel is comparable to that displayed by the wild type grown on BG-11 agar plates lacking kanamycin and alcohols.

It was reported earlier (25, 48) that the alcohol analogue (2-C-methylerythritol [ME]) of the DOXP pathway intermediate MEP could chemically complement a mutation in an E. coli gene (yaeM [now known as dxr]) encoding an enzyme (DXR) (Fig. 1) that catalyzes the formation of this compound. We reasoned that the alcohol analogues of IPP and DMAPP (3-methyl-3-buten-1-ol and 3-methyl-2-buten-1-ol, respectively) might similarly be taken up by Synechocystis, phosphorylated by endogenous kinases, and thereby serve to chemically complement mutations that eliminate or reduce the production of IPP and/or DMAPP via the DOXP pathway. Supplementation of solid media with 3-methyl-3-buten-1-ol and 3-methyl-2-buten-1-ol completely ameliorated the impairment in growth observed for the lytB(NheI)::Kanr insertion mutant of Synechocystis. Colonies formed by cells of this mutant on agar plates containing the alcohols exhibited the dark blue-green color (Fig. 4, lower panel) typical of colonies formed by wild-type cells.

Cyanobacterial and plant lytB enhance isoprenoid accumulation in Escherichia coli.

The Synechocystis lytB gene, fused to the strong bacterial Trc promoter in the plasmid vector pTrcHis (see Materials and Methods), was introduced into a strain of Escherichia coli engineered to produce the pink-colored isoprenoid compound lycopene (Fig. 1). Cells of E. coli containing this plasmid form colonies much darker pink than those formed by cells containing the empty plasmid vector (Fig. 5). Much the same enhancement of lycopene accumulation has previously been achieved by increasing the copy number of two genes that encode enzymes of the isoprenoid pathway in E. coli: dxs (19, 32) and ipi (7, 14, 22, 46, 47).

FIG. 5.

A lycopene-accumulating strain of E. coli that contains a plasmid with an Adonis aestivalis cDNA encoding LytB (pAplytB; see Materials and Methods) yields colonies much darker (the dark pink colonies) and containing much more of this pink isoprenoid than colonies produced by cells in which the second plasmid is the empty cloning vector (pale pink colonies).

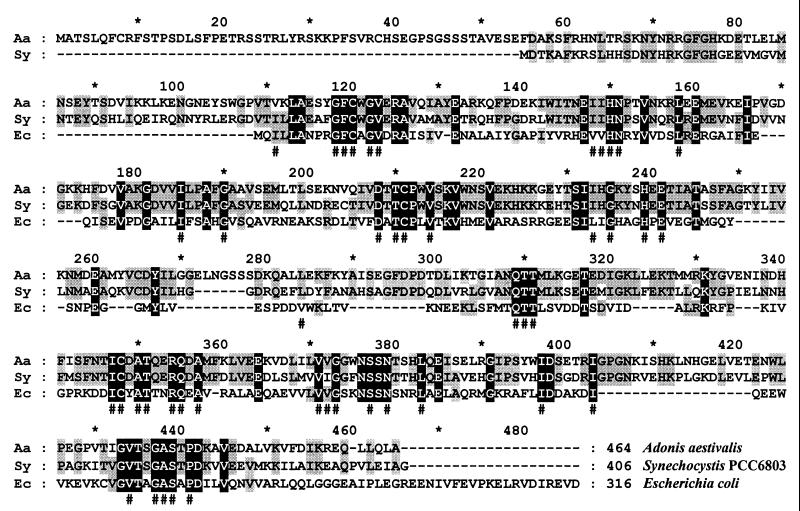

A flower cDNA library of the green plant Adonis aestivalis (pheasant's eye) was screened in the lycopene-accumulating E. coli strain for clones that produced a dark pink colony color. Two of the selected dark pink colonies contained plasmids with cDNAs encoding homologues of the Synechocystis LytB (most of the cDNAs were of ipi) (8). Although differing in length, the two Adonis lytB cDNAs were otherwise identical in sequence, and both were in the correct frame to produce a fusion protein (with an additional 41 or 50 amino acids derived from the presumed 5′ untranslated region of the cDNA, from the N-terminal adapter used to produce the cDNA, and from lacZ) under the control of the lacZ promoter of the cloning vector (pBluescript SK−). Reading from the first methionine, the 464-amino-acid polypeptide predicted by the Adonis cDNAs has an N-terminal extension of 54 amino acids when aligned with the closely related (more than 60% identity) Synechocystis LytB (Fig. 6). The Adonis N-terminal extension has the characteristics expected of a plastid targeting sequence, and the polypeptide was indeed predicted to be targeted to the chloroplast by the program ChloroP (13; http://www.cbs.dtu.dk /services/ChloroP/).

FIG. 6.

Alignment of amino acid sequences deduced from a bacterial (Escherichia coli; Ec), a cyanobacterial (Synechocystis strain PCC 6803; Sy), and a plant (Adonis aestivalis; Aa) lytB gene or cDNA. Residues identical in a given position for the three sequences are in white text on a black background. Where two of the three are identical, residues are in black text on a grey background. A pound sign (#) below the alignment denotes a position at which the amino acid residues are identical in more than 90% and/or similar in 100% of 22 sequences deduced from lytB homologues for which the complete coding regions are currently available in GenBank (5 April 2000). GenBank accession numbers are as follows: A. aestivalis, AF270978:27-1421; E. coli, AE000113:5618-6568; and Synechocystis strain PCC 6803, D64000:46364-47584.

The amounts of lycopene produced by liquid cultures of E. coli containing plant cDNAs encoding LytB (Adonis), IPI (Arabidopsis), and DXS (marigold) were quantified and compared to a control strain containing the empty cloning vector (Table 2). E. coli strains producing the carotenoids zeaxanthin (Table 2) and β-carotene (data not shown; results were essentially the same as for the lycopene and zeaxanthin strains) were also employed. The lytB cDNA (the longer of the two selected clones; see above) increased lycopene, β-carotene, and zeaxanthin accumulation by about 1.5-fold. The Synechocystis lytB gene also yielded a 1.5-fold increase (when fused to the strong Trc promoter; data not shown). The plant cDNAs encoding IPI and DXS were a bit more effective, producing a slightly more than twofold increase in carotenoid accumulation.

TABLE 2.

Enhancement of carotenoid accumulation in E. coli by plant cDNAs individually and in combination

| Plasmid | cDNA(s) | % of controla

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Lycopene | Zeaxanthin | ||

| pBluescript SK− | Control | 100 ± 4 | 100 ± 8 |

| pAalytB | Adonis lytB | 152 ± 7 | 149 ± 2 |

| pAtipiTrc | Arabidopsis ipi | 205 ± 9 | 204 ± 15 |

| pTedxs | Marigold dxs | 209 ± 8 | 223 ± 10 |

| plytB/ipiTrc | lytB, ipi | 203 ± 16 | 208 ± 21 |

| pdxs/lytB | lytB, dxs | 338 ± 23 | 342 ± 32 |

| pdxs/ipiTrc | ipi, dxs | 355 ± 14 | 345 ± 29 |

| pdxs/lytB/ipiTrc | lytB, ipi, dxs | 324 ± 8 | 306 ± 8 |

Values are means ± standard deviations for micrograms of carotenoid per volume of cell culture as a percentage of the empty cloning vector (pBluescript SK−) control. For extracts of the lycopene control cultures, A480.5 was 0.288 ± 0.011. For the zeaxanthin control cultures, A458.5 was 0.204 ± 0.016.

Combinations of lytB and dxs or ipi and dxs were substantially and significantly more effective than any individual cDNA in enhancement of carotenoid pigment accumulation (Table 2). Because the increase obtained with the combination of the two cDNAs fall within the range of values obtained by multiplying the individual effects, the influence of the Adonis lytB cDNA on carotenoid accumulation can be said to be independent of that provided by the marigold dxs cDNA. The individual effects of ipi and dxs were also multiplicative, or nearly so, in combination. With these results to establish that sink or substrate supply limitations are not significant, it is noteworthy that the combination of ipi and lytB yielded no more carotenoid pigment than ipi alone, whether the cDNAs were combined in a single plasmid (Table 2) or introduced on separate, compatible plasmids that individually bestowed the expected enhancement (data not shown).

lytB mRNA is elevated in plant cells specialized for isoprenoid biosynthesis.

mRNAs encoding enzymes of the isoprenoid pathways have been shown to be well represented in a cDNA library constructed with mRNA obtained from certain isoprenoid-rich cells (glandular trichomes) of Mentha piperita (mint) (27). Although not well represented in the plant EST database in general, we found the frequency of cDNAs encoding an LytB homologue to be extraordinarily high in a collection of ESTs obtained from this mint glandular trichome library: 11 of the 1,316 ESTs deposited as of 5 April 2000 (accession no. AW254730, AW254735, AW254890, AW254988, AW255092, AW2551238, AW255223, AW255312, AW255412, AW255711, and AW255721). Almost the entire M. piperita lytB cDNA sequence can be assembled from these EST sequences. Coincidentally, the frequency of dxs cDNAs in the deposited mint ESTs is exactly the same: 11 of 1,316 (0.84%).

DISCUSSION

The case for lytB.

The phenotype of the Synechocystis lytB(NheI)::Kanr mutant (Fig. 4) and the lethality of insertions in the coding region of this gene are in accord with a role for lytB in isoprenoid biosynthesis. Because chlorophyll is one of the major isoprenoids produced in Synechocystis and because the inorganic growth medium that was used required photosynthesis for growth of the organism, an impairment of the DOXP pathway would be expected to result in a pale green and easily bleached colony color with a diminished rate of growth. Although we attribute the observed phenotype of the lytB(NheI)::Kanr mutant to reduced transcription of the lytB gene, we do not have direct evidence of this. The Kanr in this insertion mutant resides in what is also the putative promoter region of an open reading frame (s110319) that precedes lytB and reads in the opposite direction (Fig. 2). Our data do not rule out an influence on this hypothetical gene. However, the deduced product of this gene has no obvious homologues in the protein databases, and therefore it is unlikely to be either an isoprenoid pathway gene or essential to the organism, if indeed it is transcribed. In combination with the genomic occurrence pattern of lytB relative to DOXP pathway genes (Table 1), the significant salutary effect of the Adonis and Synechocystis lytBs on carotenoid production in E. coli (Fig. 5 and Table 2), and the high frequency of lytB in a cDNA library of isoprenoid-rich mint glandular trichomes (see Results), the chemical complementation of the pale green, easily bleached Synechocystis lytB(NheI)::Kanr mutant with alcohol analogues of IPP and DMAPP (Fig. 4) makes a compelling, albeit not unequivocal, case for the involvement of lytB in the DOXP pathway.

The choice of Synechocystis as the experimental organism for insertional inactivation of lytB appears to have been a fortuitous one. It does not appear that E. coli is similarly able to utilize the alcohol analogues of IPP and DMAPP for isoprenoid biosynthesis. Supplementation of the culture media with these compounds did not increase carotenoid accumulation in liquid cultures of E. coli, nor yield more deeply pigmented colonies on agar plates (data not shown).

What is otherwise known of lytB?

Relatively little is known of lytB or of the polypeptide encoded by this gene. (Note that a Streptococcus pneumoniae murein hydrolase, also referred to as LytB [15], is unrelated to the lytB gene under discussion here.) The amino acid sequences predicted by the E. coli, Synechocystis, and Adonis lytB genes provide no obvious indication (e.g., informative sequence motifs or significant resemblance to polypeptides of known function) as to the function of the polypeptide. Certain temperature-sensitive mutations in the E. coli lytB gene have been reported to confer a tolerance to penicillin (17), a phenotype thought to derive from an influence of lytB on the stringent response (37). A tolerance of polymyxin B was also attributed to mutations in lytB in Burkholderia pseudomallei (2). These observations are not inconsistent with a role for lytB in the DOXP pathway. Any inhibition of the biosynthesis of the two major classes of isoprenoids produced in E. coli, dolichols and respiratory quinones (43), likely would impact cell wall biosynthesis (dolichols) (24) and polymyxin B uptake (quinones). The importance of the DOXP pathway to wall synthesis is made clear by the most visible response of E. coli to inhibition of the DOXP pathway by the chemical inhibitor fosmidomycin: the formation of spheroplasts (44).

What might be the function of LytB in the DOXP pathway?

It has become apparent that the DOXP pathway leads separately to DMAPP and IPP (1, 5, 14, 33, 38) (see the introduction and Fig. 1). What remains uncertain is whether distinct enzymes lead to each of these C5 isomers or, perhaps more conservatively, whether a single enzyme of the pathway yields both compounds or immediate precursors thereof. The nonadditivity of the effects of ipi and lytB on carotenoid accumulation in E. coli (Table 2) indicates that the product of lytB somehow influences the ratio of DMAPP and IPP formed by means of the DOXP pathway in E. coli, although LytB is not itself an isomerase (14, 38). It would seem, therefore, that LytB likely acts at or subsequent to the branch point of the DOXP pathway. Experiments to ascertain the biochemical function of LytB are in progress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported primarily by grants from DOE (DEFG0298ER2032) and NSF (MCB 9631257) with additional support provided by Monsanto, Quest International, and Zeneca Plc.

We are grateful to Charles P. Moehs and Dean DellaPenna of the University of Nevada at Reno for providing the marigold dxs cDNA and to Yuri Ershov and Raymond Gantt for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arigoni D, Eisenreich W, Latzel C, Sagner S, Radykewicz T, Zenk M H, Bacher A. Dimethylallyl pyrophosphate is not the committed precursor of isopentenyl pyrophosphate during terpenoid biosynthesis from 1-deoxyxylulose in higher plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1309–1314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burtnick M N, Woods D E. Isolation of polymyxin B-susceptible mutants of Burkholderia pseudomallei and molecular characterization of genetic loci involved in polymyxin B resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2648–2656. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.11.2648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chamovitz D, Pecker I, Sandmann G, Böger P, Hirschberg J. Cloning a gene coding for norflurazon resistance in cyanobacteria. Z Naturforsch Sect C. 1990;45:482–486. doi: 10.1515/znc-1990-0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chappell J. Biochemistry and molecular biology of the isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1995;46:521–547. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charon L, Hoeffler J F, Pale-Grosdemange C, Lois L M, Campos N, Boronat A, Rohmer M. Deuterium-labelled isotopomers of 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol as tools for the elucidation of the 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis. Biochem J. 2000;346:737–742. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung C T, Niemela S L, Miller R H. One-step preparation of competent Escherichia coli: transformation and storage of bacterial cells in the same solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2172–2175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.7.2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham F X, Jr, Gantt E. Genes and enzymes of carotenoid biosynthesis in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1998;49:557–583. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunningham F X, Jr, Gantt E. Identification of multi-gene families encoding isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase in plants by heterologous complementation in Escherichia coli. Plant Cell Physiol. 2000;41:119–123. doi: 10.1093/pcp/41.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham F X, Jr, Pogson B, Sun Z, McDonald K A, DellaPenna D, Gantt E. Functional analysis of the β and ɛ lycopene cyclase enzymes of Arabidopsis reveals a mechanism for control of cyclic carotenoid formation. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1613–1626. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.9.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham F X, Jr, Sun Z, Chamovitz D, Hirschberg J, Gantt E. Molecular structure and enzymatic function of lycopene cyclase from the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp strain PCC7942. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1107–1121. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.8.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Sal G, Manfioletti G, Schneider C. A one-tube plasmid DNA minipreparation suitable for sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9878. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.20.9878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenreich W, Schwarz M, Cartayrade A, Arigoni D, Zenk M H, Bacher A. The deoxyxylulose phosphate pathway of terpenoid biosynthesis in plants and microorganisms. Chem Biol. 1998;5:R221–R233. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(98)90002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emanuelsson O, Nielsen H, von Heijne G. ChloroP, a neural network-based method for predicting chloroplast transit peptides and their cleavage sites. Protein Sci. 1999;8:978–984. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.5.978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ershov Y, Gantt R R, Cunningham F X, Jr, Gantt E. Isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase deficiency in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. FEBS Lett. 2000;473:337–340. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01516-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia P, Gonzalez P, Garcia E, Lopez R, Garcia J L. LytB, a novel pneumococcal murein hydrolase essential for cell separation. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1275–1277. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein J L, Brown M S. Regulation of the mevalonate pathway. Nature. 1990;343:425–430. doi: 10.1038/343425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gustafson C E, Kaul S, Ishiguro E E. Identification of the Escherichia coli lytB gene, which is involved in penicillin tolerance and control of the stringent response. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1203–1205. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.1203-1205.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hahn F M, Hurlburt A P, Poulter C D. Escherichia coli open reading frame 696 is idi, a nonessential gene encoding isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4499–4504. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4499-4504.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harker M, Bramley P M. Expression of prokaryotic 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphatases in Escherichia coli increases carotenoid and ubiquinone biosynthesis. FEBS Lett. 1999;448:115–119. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00360-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hemmi H, Ohnuma S, Nagaoka K, Nishino T. Identification of genes affecting lycopene formation in Escherichia coli transformed with carotenoid biosynthetic genes: candidates for early genes in isoprenoid biosynthesis. J Biochem. 1998;123:1088–1096. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herz S, Wungsintaweekul J, Schuhr C A, Hecht S, Luttgen H, Sagner S, Fellermeier M, Eisenreich W, Zenk M H, Bacher A, Rohdich F. Biosynthesis of terpenoids: YgbB protein converts 4-diphosphocytidyl-2C-methyl-d-erythritol 2-phosphate to 2C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2486–2490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040554697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kajiwara S, Fraser P D, Kondo K, Misawa N. Expression of an exogenous isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase gene enhances isoprenoid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Biochem J. 1997;324:421–426. doi: 10.1042/bj3240421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaneko T, Sato S, Kotani H, Tanaka A, Asamizu E, Nakamura Y, Miyajima N, Hirosawa M, Sugiura M, Sasamoto S, Kimura T, Hosouch T, Matsuno A, Murak A, Nakazaki N, Naruo K, Okumura S, Shimpo S, Takeuchi C, Wada T, Watanabe A, Yamada M, Yasuda M, Tabata S. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions. DNA Res. 1996;3:109–136. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.3.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kato J-I, Fujisaki S, Nakajima K-I, Nishimura Y, Sato M, Nakano A. The Escherichia coli homologue of yeast Rer2, a key enzyme of dolichol synthesis, is essential for carrier lipid formation in bacterial cell wall synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2733–2738. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.9.2733-2738.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuzuyama T, Takahashi S, Seto H. Construction and characterization of Escherichia coli disruptants defective in the yaeM gene. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1999;63:776–778. doi: 10.1271/bbb.63.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lange B M, Croteau R. Isopentenyl diphosphate biosynthesis via a mevalonate-independent pathway: isopentenyl monophosphate kinase catalyzes the terminal enzymatic step. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;96:13714–13719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lange B M, Wildung M R, Stauber E J, Sanchez C, Pouchnik D, Croteau R. Probing essential oil biosynthesis and secretion by functional evaluation of expressed sequence tags from mint glandular trichomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2934–2939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.6.2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lichtenthaler H K. The 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate pathway of isoprenoid synthesis in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50:47–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lois L M, Campos N, Putra S R, Danielsen K, Rohmer M, Boronat A. Cloning and characterization of a gene from Escherichia coli encoding a transketolase-like enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis of d-1-deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate, a common precursor for isoprenoid, thiamin, and pyridoxol biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2105–2110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luttgen H, Rohdich F, Herz S, Wungsintaweekul J, Hecht S, Schuhr C A, Fellermeier M, Sagner S, Zenk M H, Bacher A, Eisenreich W. Biosynthesis of terpenoids: YchB protein of Escherichia coli phosphorylates the 2-hydroxy group of 4-diphosphocytidyl-2C-methyl-d-erythritol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1062–1067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marcotte E M, Pellegrini M, Thompson M J, Yeates T O, Eisenberg D. A combined algorithm for genome-wide prediction of protein function. Nature. 1999;402:83–86. doi: 10.1038/47048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matthews P D, Wurtzel E T. Metabolic engineering of carotenoid accumulation in Escherichia coli by modulation of the isoprenoid precursor pool with expression of deoxyxylulose phosphate synthase. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;53:396–400. doi: 10.1007/s002530051632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCaskill D, Croteau R. Isopentenyl diphosphate is the terminal product of the deoxyxylulose-5-phosphate pathway for terpenoid biosynthesis in plants. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:653–656. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pellegrini M, Marcotte E M, Thompson M J, Eisenberg D, Yeates T O. Assigning protein functions by comparative genome analysis: protein phylogenetic profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4285–4288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramos-Valdivia A C, van der Heijden R, Verpoorte R. Isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase: a core enzyme in isoprenoid biosynthesis. A review of its biochemistry and function. Nat Prod Rep. 1997;14:591–603. doi: 10.1039/np9971400591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rippka R, Deruelles J, Waterbury J B, Herdmann M, Stanier R Y. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1979;111:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodionov D G, Ishiguro E E. Direct correlation between overproduction of guanosine 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate (ppGpp) and penicillin tolerance in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4224–4229. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.15.4224-4229.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodríguez-Concepción M, Campos N, Lois L M, Maldonado C, Hoeffler J-F, Grosdemange-Billiard C, Rohmer M, Boronat A. Genetic evidence of branching in the isoprenoid pathway for the production of isopentenyl diphosphate and dimethylallyl diphosphate in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 2000;473:328–332. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01552-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rohdich F, Wungsintaweekul J, Fellermeier M, Sagner S, Herz S, Kis K, Eisenreich W, Bacher A, Zenk M H. Cytidine 5′-triphosphate-dependent biosynthesis of isoprenoids: YgbP protein of Escherichia coli catalyzes the formation of 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methylerythritol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11758–11763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rohmer M, Seemann M, Horbach S, Bringer-Meyer S, Sahm H. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate and pyruvate as precursors of isoprenic units in an alternative non-mevalonate pathway for terpenoid biosynthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:2564–2566. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruther A, Misawa N, Böger P, Sandmann G. Production of zeaxanthin in Escherichia coli transformed with different carotenogenic plasmids. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;48:162–167. doi: 10.1007/s002530051032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sherman M M, Petersen L A, Poulter C D. Isolation and characterization of isoprene mutants of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3619–3628. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.3619-3628.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shigi Y. Inhibition of bacterial isoprenoid synthesis by fosmidomycin, a phosphonic acid-containing antibiotic. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1989;24:131–145. doi: 10.1093/jac/24.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sprenger G A, Schörken U, Wiegert T, Grolle S, de Graaf A A, Taylor S V, Begley T P, Bringer-Meyer S, Sahm H. Identification of a thiamin-dependent synthase in Escherichia coli required for formation of the 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate precursor to isoprenoids, thiamin, and pyridoxol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12857–12862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.12857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun Z, Cunningham F X, Jr, Gantt E. Differential expression of two isopentenyl pyrophosphate isomerases and enhanced carotenoid accumulation in a unicellular chlorophyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11482–11488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun Z, Gantt E, Cunningham F X., Jr Cloning and functional analysis of the β-carotene hydroxylase of Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24349–24352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takahashi S, Kuzuyama T, Watanabe H, Seto H. A 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase catalyzing the formation of 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate in an alternative nonmevalonate pathway for terpenoid biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9879–9884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams J G K. Construction of specific mutations in photosystem II photosynthetic reaction center by genetic engineering methods in Synechocystis 6803. Methods Enzymol. 1988;167:766–778. [Google Scholar]