Abstract

Obesity is a chronic disease that affects more than 650 million adults worldwide. Obesity not only is a significant health concern on its own, but predisposes to cardiometabolic comorbidities, including coronary heart disease, dyslipidemia, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and some cancers. Lifestyle interventions effectively promote weight loss of 5% to 10%, and pharmacological and surgical interventions even more, with some novel approved drugs inducing up to an average of 25% weight loss. Yet, maintaining weight loss over the long-term remains extremely challenging, and subsequent weight gain is typical. The mechanisms underlying weight regain remain to be fully elucidated. The purpose of this Pennington Biomedical Scientific Symposium was to review and highlight the complex interplay between the physiological, behavioral, and environmental systems controlling energy intake and expenditure. Each of these contributions were further discussed in the context of weight-loss maintenance, and systems-level viewpoints were highlighted to interpret gaps in current approaches. The invited speakers built upon the science of obesity and weight loss to collectively propose future research directions that will aid in revealing the complicated mechanisms involved in the weight-reduced state.

INTRODUCTION

In the face of a worsening obesity epidemic over the past half century, a wide variety of interventions have been demonstrated to result in varying degrees of successful weight loss. Unfortunately, long-term maintenance of weight loss has proven painfully difficult [1–4]. As such, it is imperative to shed light on the complex physiological, behavioral, and environmental underpinnings of weight-loss maintenance (WLM). To begin to work toward this goal, the 2022 Pennington Biomedical Scientific Symposium assembled leading scientists and clinicians to discuss the “State of the Science” surrounding the mechanisms of weight loss with an emphasis on WLM. The symposium described the physiology (genetics and biological mechanisms) underlying energy balance dynamics over time, the impact of weight loss on energy intake and expenditure, and the behavioral and environmental modulators of these two limbs of energy balance after weight loss. The symposium concluded with a discussion of the ongoing efforts to understand the complex impediments to maintenance of lost weight, as well as identify knowledge gaps and future research needs.

WEIGHT LOSS AND WLM: TWO DIFFERENT PHYSIOLOGICAL STATES

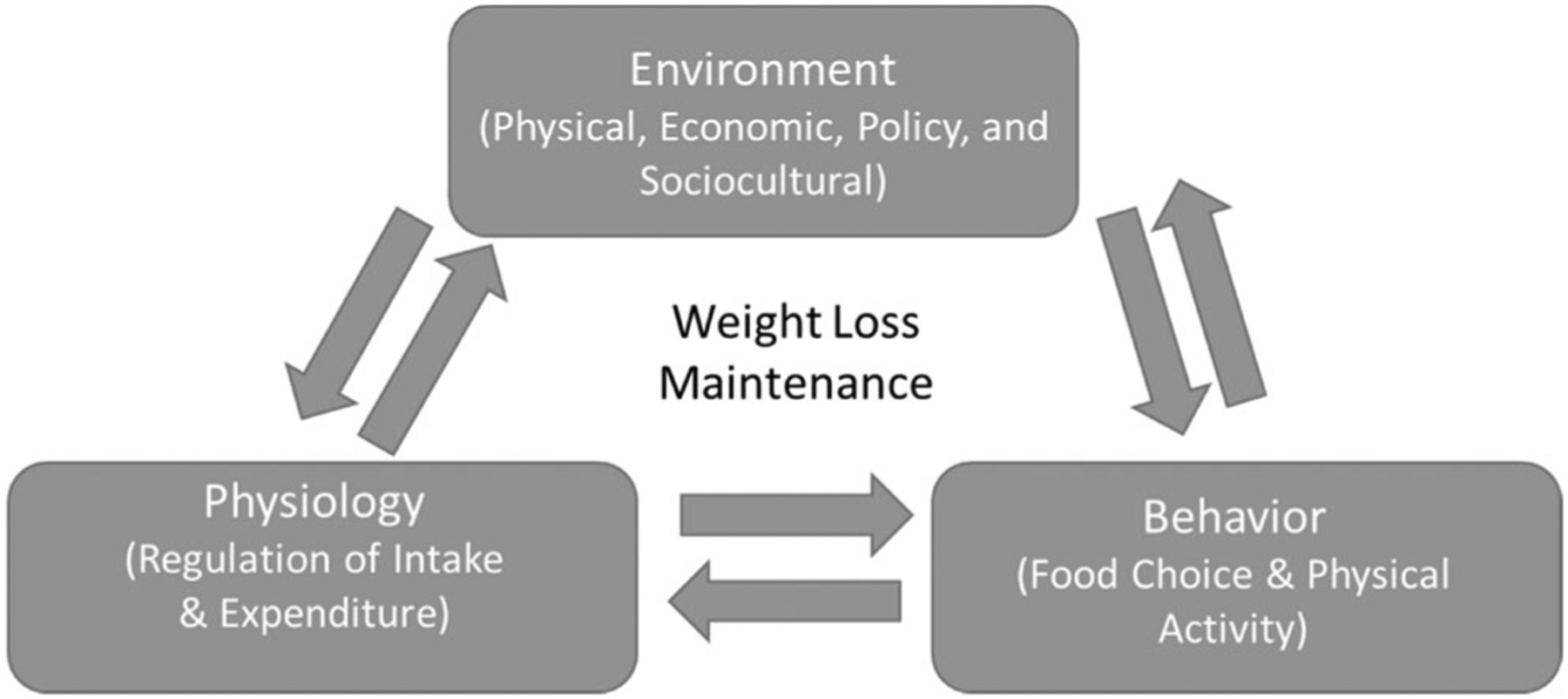

There may be distinct physiological drivers of weight loss that differ from the drivers of subsequent maintenance of the lost weight, coined WLM. For example, the authors of the symposium propose and argue that the genotypic and phenotypic correlates of the amount of weight loss in controlled interventions are distinct from those which are correlated with success in keeping the lost weight off [5]. We propose that the differing physiological states between weight loss and WLM emerge at the cellular and organ levels, resonate through behaviors, and are both influenced by the surrounding environment (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The proposed interplay between environment, physiology, and behaviors on weight-loss maintenance.

During maintenance at usual weight, energy intake and expenditure are directly coupled such that when energy intake goes up or down so does energy output in service of maintaining a relatively constant level of energy stores over time. In the event of weight loss, an individual attempts to “uncouple” these two processes, usually by trying to decrease caloric intake and increase energy output. Thus, when expenditures exceed intake values, there is a loss of body mass. Following weight loss, this seemingly “simple” feedback system is perturbed by internal physiological processes that oppose further weight loss and make it very difficult to maintain the newly achieved body mass.

Long after the seminal observation by Stunkard and McLaren-Hume [6], many researchers have shown that regain of intentionally lost body mass occurs in the face of the most rigorous weight-loss interventions [7]. Despite successful weight loss, it has been shown that approximately half of the lost weight is gained back within 2 years and up to 70% by 5 years [8]. Importantly, such weight regain occurs regardless of weight-loss therapy. Bariatric surgery was once thought to be the standard for effective and durable weight loss showing greater maintenance of weight loss up to 5 years out compared with behavioral and pharmacological interventions [9, 10]. Recent evidence, however, has shown that bariatric surgery is no longer spared from weight regain, with nearly 50% of patients showing some weight regain 2 years following surgery and 60% by 5 years [11]. Yet, surgical interventions remain the most effective long-term weight-loss intervention with the least amount of weight gain and may reveal insights into the possibility of “reprogramming” of the endocrine and neural pathways involved in body mass regulation [12] (discussed in detail further).

METABOLIC ADAPTATIONS TO WEIGHT LOSS

The theory that the human body acts in a way to defend a body mass, or rank order of body fatness in a given environment, via a hypothetical “set point” has been long debated [13–15]. As heuristic, this simple feedback loop is like a thermostat and is clearly untenable in the face of obvious trends of weight gain among most individuals as they age among nearly all populations over time. The concept of a “settling point” allows for the inclusion of more complexity by considering that a person’s weight is the net result of multiple, competing metabolic pathways through energy intake and expenditure as well as the external factors of the current obesogenic environment. Where the balance of these influences settles determines the person’s weight. For example, the level of a natural body of water is settling as the result of all the inflows, outflows, soakage, and evaporation. In contrast to the set point (a fixed predetermined value), the human body is much more adaptive and results from the interactions between the biology of the person and the behaviors acquired in a given environment. Such “regulation” comes to the heart of the challenge of WLM. Although human behavior acts to defend weight loss through hedonic pathways and ingrained lifestyle behaviors (discussed in detail further), human physiology also responds to weight loss (and weight gain) in an active, responsive way. Adaptive increases in appetite and declines in expenditure occur in response to weight loss. For instance, a prolonged state of increased energy expenditure may be met with increased skeletal muscle efficiency, whereas prolonged energy deficit is met with hypometabolism and hyperphagia. Such defense mechanisms, likely once crucial traits for survival, now serve to reverse weight loss, furthering the development of obesity.

Quite apart from the background obesogenic environment continuing to promote weight gain, the metabolic adaptation driving weight regain gives the appearance that it is defending the prior body weight. Comparative models show that some living species are designed to preserve adiposity [16], but others hypothesize that, for humans, it is the lean mass that the body is trying to preserve [17]. Applying systems science models to this problem may provide a clearer, big-picture view of what goal the metabolic responses are trying to achieve with the multitude of adaptations to significant weight loss (discussed in detail further).

Adaptations in energy expenditure

In the state of a negative energy balance and corresponding weight loss, a slowing of the metabolic rate termed “metabolic adaptation” is triggered. Metabolic adaptation is the larger than expected reduction in resting energy expenditures based on the loss of metabolic mass. These reductions in energy expenditure are hypothesized to persist over time and to play a role in the resistance to further weight loss and the failure to maintain a new, lower body weight [18]. Three landmark studies have revealed the presence of metabolic adaptation up to several years following weight loss. The first are data from the well-known Comprehensive Assessment of Long-Term Effects of Reducing Intake of Energy (i.e., CALERIE) trials, where an average of 9 kg were lost over 2 years and resulted in a metabolic adaptation of approximately 100 kcal/day after 2 years (N = 34 adults undergoing caloric restriction) [19]. In a separate weight-loss trial, with a 10% loss of body mass, metabolic adaptation was found to amount to ~350 kcal/day (N = 41; of which 18 had obesity) [20]. Careful phenotyping using titration of fed calories of a liquid formula diet necessary to maintain body weight and resting metabolic rate (RMR) found that these metabolic adaptations persisted in individuals who were able to maintain a 10% weight loss at 6 years following the initial weight loss [21]. The third set of data comes from individuals who participated in “The Biggest Loser” competition (N = 14 studied). After an almost 50% reduction in body weight, RMR declined 700 kcal/day below baseline. Importantly, metabolic adaptation was again shown to persist 6 years later, despite significant weight regain [22–24].

One particular physiological determinant of the degree of metabolic adaptation has gained attention over recent years. Leptin, a central adipokine hormone regulating food intake and many other neuroendocrine pathways, is related to metabolic adaptation [24, 25]. Leptin tracks with adipose tissue and therefore is reduced in the face of weight loss. Data from the CALERIE trials show that after an 11% weight loss, the degree of metabolic adaptation was significantly and independently related to the reduction in 24-h leptin [25]. In another study, comparing weight loss by intensive lifestyle interventions versus bariatric surgery, metabolic adaptation was strongly correlated with the degree of energy imbalance and the decline in circulating leptin [24]. Together, the data indicate that leptin may serve as a neuroendocrine defense mechanism to regulate energy expenditure (and of course energy intake) in the presence of a negative energy balance and beyond.

Adaptations in energy intake

Even if metabolic adaptation plays a role in opposing the weight-reduced state, it is often argued that hyperphagia is a fierce defender and probably the primary driver of weight regain [5, 26]. Physiological changes to homeostatic pathways are responsible for driving energy intake after weight loss [3, 4]. Indeed, mathematical models of energy balance, developed by Hall and colleagues, clearly illustrate that appetite increases progressively above baseline and to a higher degree than the respective reductions in energy expenditure. Such models estimate that for each kilogram of lost weight, caloric expenditure decreases by 25 kcal/day and is met by a 95 kcal/day appetite increase [27]. For these reasons, reduced satiety, increased hunger, and altered perceptions of food create the “perfect physiological storm” for weight regain.

During weight loss, leptin fluctuations may play a role in maintaining energy balance. Following 10% weight loss and subsequent declines in energy expenditure, repletion of leptin was found to reverse the metabolic adaptation to weight loss by increasing energy expenditure [28]. Importantly, leptin levels are observed to be significantly below baseline 1 year following weight loss [29]. Additional anorexigenic hormones, including peptide YY and cholecystokinin, appear to remain lower than pre-weight loss levels at 1 year [29]. Together, these hormone changes appear to work against maintenance of lost weight.

BIOLOGICAL CONTRIBUTORS OF ENERGY BALANCE FOLLOWING WEIGHT LOSS

Central control of energy homeostasis; lessons from animal studies

Energy balance dynamics are centrally orchestrated by the brain, but this requires feedback from peripheral signals as well as environmental cues and top-down processing. The question becomes why does obesity occur in the first place if the brain is supposed to maintain energy homeostasis by defending a certain body weight and can the proposed settling point change? Additionally, after achieving weight loss, why does the body fight to reestablish the obese state? In rodent models, feeding of palatable energy-dense diets results in greater weight gain compared with standard chow diet [30]. Furthermore, numerous studies in diet-induced obese mice and rat models have shown that by restricting caloric intake, weight can be significantly reduced, but if they have been fed high-fat diet for many weeks, they defend a higher body weight and not the weight of lean animals [31–34]. These studies demonstrate that, although the brain seems to work toward defending a certain body weight, this target weight can be perturbed and shifted upward.

Homeostatic control of energy balance occurs in the basomedial hypothalamus and brainstem circuits, which relay energy state information from the periphery and turn it into a behavioral output. Appetite and energy expenditure are largely mediated by two populations of neurons in the arcuate nucleus: agouti-related protein (AgRP)/neuropeptide Y neurons, which encode hunger and anabolic signals, and proopiomelanocortin/cocaine and amphetamine-regulated transcript neurons, which encode the satiety and catabolic signals [35]. The importance of these neurons has been demonstrated in animal models. If AgRP neurons are silenced, mice will stop eating to the point of fatality [36, 37]. Conversely, experimentally activating this population of neurons increases food intake, weight gain [38], and motivation for food seeking [39]. These AgRP neurons integrate many hormonal and neuronal signals to maintain energy homeostasis and defend an individualized body weight [35].

Peripheral signals from the gut, such as mechanical distention and macronutrient absorption, are also relayed to arcuate nucleus neurons via vagal or spinal afferences [40]. In mice, glucose infusion into the gut inhibits AgRP neural activity, thereby decreasing appetite [40]. Hormones such as leptin and insulin are also important signals of energy intake with receptors on these two populations of neurons [35]. When leptin and insulin act upon AgRP neurons, the hypothalamus signals to decrease appetite and increase energy expenditure [41]. Unfortunately, this does not remain true after prolonged periods of consuming obesogenic foods. Signals such as leptin are less effective in chronically obese animals [32], and ultimately, AgRP neurons are desensitized after obesity has occurred [42]. Another insight that the hypothalamus can modulate counter-regulatory mechanisms comes from animals with seasonal body weight changes. The body weight of Siberian hamsters, for instance, fluctuates throughout the year triggered by shorter daylight periods, and the mechanism seems to be distinct from those that are engaged during calorie restriction [16]. These examples demonstrate that the hypothalamus may be malleable and could be an important target for therapies.

Higher-level cortical and limbic processing mediate the hedonic and cognitive aspects of eating. Hedonic processes drive the motivation and “wanting” of food within the brain’s reward system, which may serve as a memory mechanism placing value on beneficial foods. The mesolimbic dopamine system is a key part of this circuitry, driving motivated behaviors and rewarding experiences [35]. When a high caloric or high sugar food is consumed, there is greater dopaminergic tone in this pathway, representing another way in which obesogenic foods can “highjack” the brain into raising energy intake, which, in the obesogenic environment, is counteractive to WLM [35]. The prefrontal cortex, on the other hand, is the area responsible for orchestrating cognition and executive functions modulating the restraint in food choice and, in individuals with obesity, is less active in response to food [35]. Together, these systems represent the “neuro-economics” of energy intake (i.e., what is the assigned goal value, decision value, and prediction error) [43].

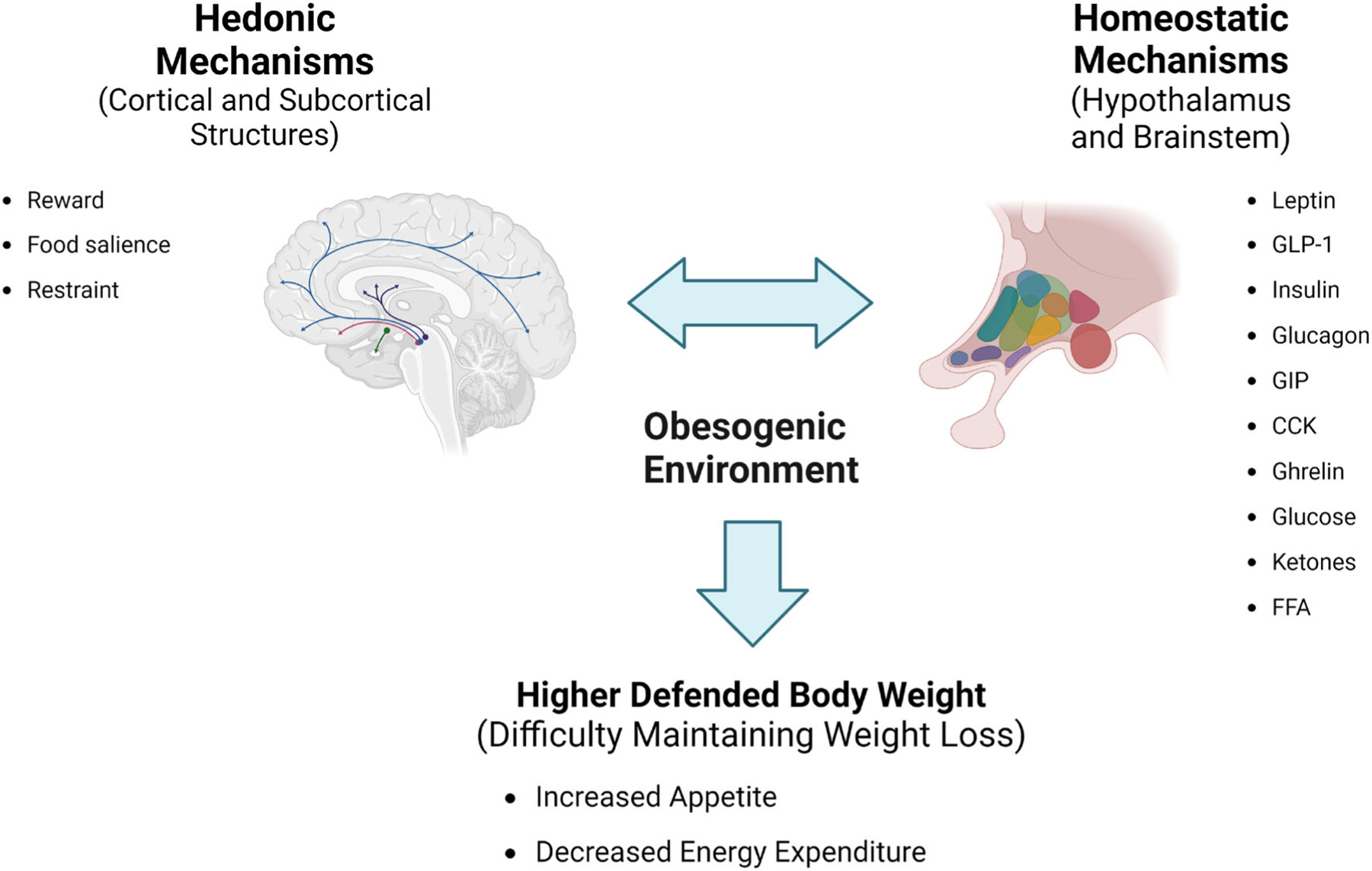

The homeostatic regulation of body and upper-level processing are often thought of as two separate systems. However, there is accumulating evidence that they are very interactive and signal in both directions (Figure 2) [44]. In humans, functional magnetic resonance imaging studies with food images show that the nucleus accumbens exhibits greater activity in a low-leptin state (e.g., a weight-reduced state) and that this response is abolished when the participants are administered leptin [45]. In rodents, optogenetically stimulating AgRP neurons not only drives food intake but has a sustained positive reinforcing effect via projections to cortical structures [39]. Together, these two examples demonstrate the complex interaction between homeostatic and hedonic systems. Thus, in the weight-reduced state, therapy aimed at opposing these circuits must take both processes into account.

FIGURE 2.

Central mechanisms influencing weight-loss maintenance. Hedonic and homeostatic mechanisms in the brain work together to regulate energy balance and generate eating behavior. In the obesogenic environment, these mechanisms are altered, leading to increased body weight and working against weight-loss management treatments. CCK, cholecystokinin; FFA, free fatty acids; GIP, gastric inhibitory protein; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1. Created with BioRender.com.

Gut interface and microbiome

At the other end of energy homeostasis is the gut interface itself where nutrients are absorbed. It has been determined that humans lose from 2 to 9% of ingested calories through the stool [46, 47], but whether stool energy loss is involved in the development of obesity or the failure of WLM is poorly understood. To elucidate this question, one study measured calorie intake and excretion using bomb calorimetry and found no differences between calories excreted in stool between individuals with normal weight versus those with obesity [48]. One aspect of the gut (particularly in the large intestine) which might impact energy excretion is the gut microbiota.

Although studies are limited, some evidence exists for a role of the gut microbiome in energy harvest. For instance, germ-free mice do not gain as much weight on a Western diet as conventional mice [49], whereas transplanting gut microbiota from obese mice leads to lower calories/gram in excreted stool [50]. In humans, when individuals with normal weight and those with obesity were compared, there was no baseline difference in gut microbiota composition. Yet, overfeeding both groups for just 3 days by 1000 kcal led to an increase in the relative abundance of the bacterium species Firmicutes and a decrease of Bacteroidetes related to increased calorie absorption in lean individuals [48]. Conversely, underfeeding for 3 days resulted in an increase in Akkermansia Muciniphila abundance in conjunction with increased stool calorie loss (i.e., decreased calorie absorption) [46]. Likewise, by treating study participants with the oral antibiotic vancomycin, A. Muciniphila was similarly reduced and stool calorie loss increased [46] (reproducing findings in a prior study [50]). Intriguingly, this bacterium is known to play a role in mucous layer maintenance [51]. Despite this relative reduction in A. Muciniphila no difference was found in plasma gut permeability markers after antibiotic treatment, indicating no change in the integrity of the gut epithelial barrier [46]. These results demonstrated that changes in gut microbiota may play a role in stool calorie loss. However, this difference only accounted for ~2.5% of ingested calories (~80 kcal/day). Changes in stool calorie loss that occur with underfeeding and alteration of the gut microbiota need further exploration in terms of their effect on WLM.

Lessons from bariatric surgery

Bariatric surgery has, for a long time, been the most effective and durable means of weight loss. Multiple studies have found that, compared with standard behavioral or pharmacological interventions, bariatric operations are superior in their ability to sustain weight loss and treat type 2 diabetes [10, 52, 53]. However, recent advances, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and now gut peptides in combinations, have made pharmacological interventions more efficacious and may very well rival bariatric surgery for weight loss and WLM [54].

The striking difference between bariatric surgery and other interventions seems to be the superiority of surgery to counter compensatory mechanisms of voluntary reduced calorie intake, such as increased appetite or reduced energy expenditure, even if the studies have not always been conclusive. Through clinical research, we have learned that individuals who receive Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, which of bariatric surgeries has been around longer and studied more, consume 40% fewer calories and absorb 10% fewer calories from fat compared with before surgery when matched on energy intake [55, 56]. Additionally, patients of both vertical sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass report a decrease in hunger and hedonic appeal of food [57], supported by functional magnetic resonance imaging studies [58, 59].

Rodent models of bariatric surgery allow researchers to test for potential mechanisms involved in sustained weight loss. Animal models of diet-induced obesity lose up to 50% of their body weight and initially consume less food than presurgical amounts, even though they remain on a high-fat diet [60]. Animals post-vertical sleeve gastrectomy, however, have the ability to consume as much volume of food as nonsurgery animals [60] demonstrating that the surgery is not mechanically restrictive, rather, animals choose to eat less for some other reason. Bariatric surgery in rats also alters food preferences, with postsurgery animals choosing less energy-dense diets [61], providing further evidence that the rewarding aspect of food may be altered by surgery. Many hormones and peptides have been investigated and found to be not related to the effectiveness of bariatric surgery, and studies have yet to identify a definitive mechanism for the lack of compensatory response [62]. As with antibiotic treatment, research of bariatric surgery mechanisms reveals a connection to the gut microbiome. Bariatric surgery has been shown to alter the gut microbiome and transcriptional regulation in the gut that is linked to bacterial metabolites [63–65], demonstrating that future research should consider the importance of the gut interface and immune signaling when investigating methods to improve WLM.

BEHAVIORAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE ENERGY BALANCE FOLLOWING WEIGHT LOSS

Food composition

External factors, such as where we live and the availability of food, also influence the weight-reduced state. Environmental and societal changes have an increasing role in the prevalence of obesity and the upward shift in an individual’s defended weight. One theory is that the abundance of highly processed carbohydrate-rich foods in our modern world is the root of the problem. Many studies have now been conducted demonstrating the relationship between macronutrient composition and body weight regulation. In well-controlled clinical trials, isocaloric diets with varying amounts of carbohydrate and fat have no meaningful impact on energy storage or expenditure [66–71]. Such studies demonstrate that low-carbohydrate diets have a negligible advantage over low-fat/high-carbohydrate diets for short-term weight loss [67]. Furthermore, ad libitum energy intake was measured when a minimally processed low-carbohydrate and high-carbohydrate diet were compared, participants consumed almost 700 kcal/day less of the high-carbohydrate diet and lost more body fat [72]. It is therefore difficult to support the idea that high-carbohydrate diets are the culprit for the failure of WLM.

Although both low-fat and low-carbohydrate diets are capable of reducing body weight, proponents of the two dietary approaches tend to agree that people should decrease consumption of ultraprocessed foods. However, ultraprocessed foods are difficult to avoid because they are ubiquitous, highly marketed, inexpensive, convenient, and tasty. A domiciled cross-over study comparing diets rich in ultraprocessed compared with unprocessed foods, but matched for sodium, sugar, fat, and fiber, showed that a diet high in ultraprocessed food resulted in greater consumption of calories and body fat gain, whereas participants lost body fat when fed an unprocessed diet [73]. These studies suggest that reducing the consumption of ultraprocessed foods would be beneficial during WLM.

The built environment

In addition to the food environment, evidence links the broader built environment (i.e., where an individual lives) to their health. The built environment comprises the surrounding physical environment such as the walkability (i.e., ability of individuals to walk for leisure or transport through an environment) and availability of recreational spaces and the accessibility of food. A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies investigating the physical environment in the United States, Australia, and Europe found a strong association between higher walkability and less urban sprawl with a lower incidence of obesity or decrease in adiposity [74]. Additionally, greater walkability and access to recreational facilities has been linked to increased physical activity [75]. Natural city planning experiments strengthen these findings. For example, urban redevelopment in Charlotte, North Carolina, demonstrated a reduction in body mass index (BMI) and an increase in physical activity after a light-rail system was created and walking infrastructure was improved [76, 77]. As for food availability, evidence indicates an association between proximity to fast food retail stores and greater adiposity [78]. Conversely, limited evidence suggests there is an increased consumption of fresh fruit and vegetables when access is increased [75]. Not only is the built environment related to obesity risk and physical activity, but data support that environmental factors, including grocery store density, walkability, and economic status of a neighborhood, explains up to 11% of the variability in response to a weight-loss intervention [79]. It is likely that such factors are also involved in the success of WLM. Individuals living in unhealthier environments, defined as ratio of unhealthy (e.g., fast food retail stores) to healthy (e.g., grocery stores), report more difficulty managing weight loss and ultimately do not exhibit as much WLM success [80].

A commonly overlooked aspect of the built environment is the number of chronic stressors that an individual may experience. These stressors come from numerous sources, including social environment features (i.e., economic and housing instability, neighborhood violence, residential segregation, limited social cohesion) and interpersonal discrimination, which promote adverse health behaviors like disrupted sleep [81]. Such stressors also lead to increased hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and sympathetic nervous system activity, which promotes chronic inflammation, thereby exacerbating obesity [81]. Multiple studies found associations between lack of green spaces [82], living in a lower socioeconomic neighborhood [83], and food insecurity and greater inflammation or markers of stress [84, 85]. Furthermore, physical limitations in recreational spaces and lack of neighborhood safety may also limit the amount of physical activity among pediatric populations [86]. Limited research exists, however, on whether interventions that address these stressors or the lack of environmental support are effective at improving health. The interplay between the available food and the built environments with individual level factors, such as sociocultural preferences, create added complexities to elucidating effective WLM approaches.

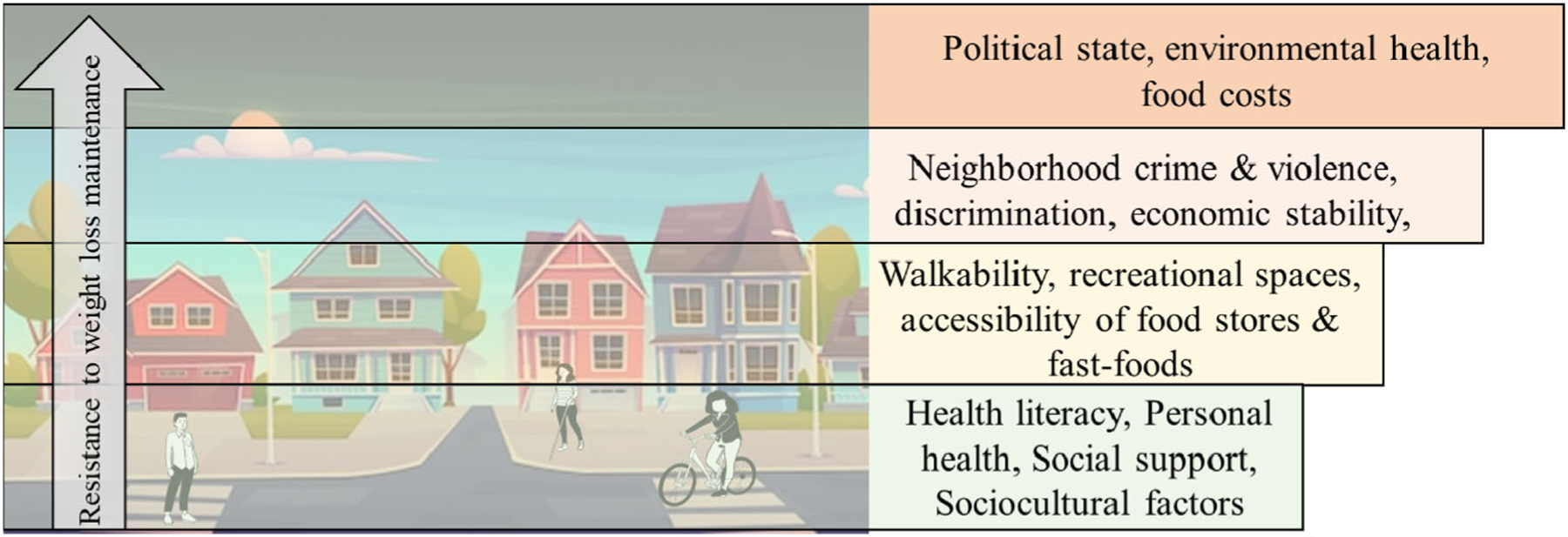

The “syndemic”

A novel “systems-level” approach may reveal insights into weight loss and abilities to effectively maintain a reduced weight (Figure 3). The food environment can be viewed as a flawed system, with the ultimate purpose of economic viability and not the health of the individual or the planet. This has led to the proposal that we are entangled within a “Global Syndemic,” comprising climate change and environmental destruction, along with the obesity epidemic often coinciding with undernutrition [87]. At the center of this syndemic lie ultraprocessed foods, which make up over 50% of total energy consumption in Western countries [88]. Such foods are cheaper, more shelf-stable, more palatable, and readily marketable, while being worse for environmental and human health and reinforcing behavior [88]. Individuals are intimately bound up within the system of ultraprocessed foods through multiple feedback loops (societal, economic, and biological). Arguably, the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the proposed syndemic, with added stressors related to health, economics, and family. As with most interventions for weight loss and WLM, one inherent problem with intervening is the targeting of the “event” or end-goal (e.g., weight or dietary intake). Distinctly, the syndemic strategy proposes that effective interventions must approach system-level changes. Thus, any intervention that can truly influence WLM will have to work against the entire food environment system, undoubtedly a challenging feat.

FIGURE 3.

Environmental factors contributing to energy intake. An example of system-level thinking for weight-loss maintenance. Lower (person-level) changes are increasingly difficult in the presence of higher-level systems (e.g., political policies). System-level changes from top-down are hypothesized to produce largest effects.

BEHAVIORAL INTERVENTIONS FOR WLM

While policymakers and obesity activists target system-level changes, “end-goal” interventions must remain ongoing. One crucial flaw to standard interventions is that it is common practice for an intervention to cease following weight loss. Even if the biological drive to defend lost body mass is initiated, this drive to regain weight may be overcome by behavioral strategies. It comes as little surprise that individuals who regain weight requested more intervention and support during weight loss and the maintenance phases [89]. Contrary to weight-loss interventions alone, treatment for WLM is lifelong, whether with surgery, pharmaceuticals, or behavioral interventions. WLM is often challenged with the loss of familial and social support and lack of reinforcing feedback (e.g., daily weight-loss achievements). This, plus the lack of continued intervention in the WLM phase and the presence of the obesogenic environment, amplify the brain circuits and metabolic adaptations in promoting weight regain after weight loss. Behavioral interventions to support WLM should target efficacy, high-quality diets, and increased physical activity while taking social, food, and built environments into account.

Predictors of successful WLM

In weight loss, the best predictor of the success is the amount of weight lost within the first month of intervention [90]. On the contrary, this is not indicative of WLM success or the degree of weight regain. There are, however, behavioral predictors of weight regain that often resemble those of successful weight loss [89]. After individuals have maintained weight loss for 2 to 5 years, the chance of long-term success greatly increases [3]. In terms of cognitive and mental processes, long-term WLM is associated with low levels of depression and disinhibition [91]. Conversely, internalized weight stigma serves as a significant barrier to WLM. It has been found that, for every unit increase in stigma, the odds of maintaining weight loss decrease by 28% [92]. Familial encouragement of exercise and healthy eating have also been found to predict success of WLM [89]. Intervention modality appears to also contribute to the success of WLM. In one study, individuals with a face-to-face intervention delivery had 2.4 kg less weight regain over 18 months compared with those receiving a remote intervention [93]. Behaviors akin to weight-loss success, including continuing self-monitoring of weight and food, engaging in physical activity, executing portion control, and continuous reductions to energy intake, also promote successful WLM [94].

Although energy intake appears to be the anchor of successful WLM, an accumulating amount of evidence suggests that high levels of physical activity (~200–300 min/week of at least moderate-intensity aerobic activity) are considered to be a trait of those who are successful. In a sample of adults who participated in an 18-month behavioral weight-loss intervention, it was found that successful weight-loss maintainers demonstrated greater increases in moderate to vigorous physical activity compared with those who regained over the course of 2 years [95]. Furthermore, the National Weight Control Registry, a large public database designed to identify the characteristics of successful weight-loss maintainers, provides additional support [96]. Successful weight-loss maintainers from this population spent 60 min/day more in light physical activity and 60 min/day less in sedentary states compared with control individuals with obesity [97].

The physical environment of successful weight-loss maintainers

In addition to the way individuals think and feel, environmental factors can serve as friction or fuel when it comes to making behavior changes. It is highly likely that the reduction of commercially available energy-dense foods (e.g., food manufacturers, supermarkets, restaurants) would facilitate weight-loss control in populations [98]. Progressive implementation of public health policies to encourage systematic changes is ultimately needed but is still a distant reality. Meanwhile, to optimize weight-maintenance interventions, it is prudent, if not imperative, to alter the individuals’ food environment, such as by eliminating food deserts where high-quality foods are less fresh and more expensive and by providing resources when the physical environment cannot be changed. Interventions that modify the home food environment appear effective. In one study comparing behavioral interventions, meal replacement therapy, or modification of the home food environment, the latter showed the highest degree of weight loss during the 6-month intervention as well as during the 36-month follow-up [99]. Modification of the home food environment included reducing energy-dense foods and instead replacing with preportioned foods and those with high levels of protein and fiber to promote satiety. Altering the home food environment was additionally shown to improve cognitive restraint, a predictor of successful WLM.

It should be noted that alteration of the environment may not always be feasible. This dilemma becomes increasingly relevant when understanding how the environment may modify interventions. For instance, environmentally disadvantaged individuals live in less supportive environments, characterized by poorer social environments and quality of physical activity and dietary resources. Such inequities in social environments and access to quality resources may underlie health disparities related to physical activity, diet, and subsequently, the ability to maintain healthy weight losses. Thus, individuals residing in such communities require greater support to ensure equally effective interventions. It is important to consider whether environmental factors impact the intervention response by complementing the intervention or substituting for environmental deficiencies, as each provide a different type of support [100]. Complement interventions enhance the intervention to increase success and predict better weight loss in environments with greater support. On the other hand, substitute interventions are more appropriately suited for less supportive environments, as they provide resources or support that make up for environmental deficits. To effectively foster the maintenance of lost weight, there is a critical need to support individuals most at risk for obesity-related disparities. This should be approached by allocating substitutive resources to individuals with low environmental support.

Future of interventions for WLM

Several strategies have emerged to effectively improve WLM. Two of the most successful strategies are the use of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and increased physical activity [101]. ACT is a practice that uses acceptance and mindfulness strategies to increase patterns of value-consistent behavior and reduce avoidance behaviors. It was found that in individuals with high internal disinhibition or eating in response to cognitive cues (a predictor of weight regain), ACT therapy may be effective for improving WLM over 2 years [102]. Interventions incorporating ACT over standard behavioral treatment resulted in 2.5 kg less weight regain, and individuals were more likely to maintain 10% weight loss at 3 years [103]. Yet, given that only one third of individuals were able to maintain 10% weight loss at 3 years, such interventions alone may not be enough to promote WLM.

Furthermore, the incorporation of high levels of physical activity into WLM interventions should be considered a high value. One reason in support of physical activity for WLM success, is the potential counteraction of the biologic adaptations that occur during weight loss. For instance, it has been shown that physical activity increases sympathetic nervous system tone, hepatic de novo lipogenic capacity, skeletal muscle dietary fat oxidation, circulating glucose, and free fatty acids [104]. Physical activity may help fill the “energy gap” that was caused by weight loss (i.e., metabolic adaptations in energy expenditure and energy intake). With higher levels of total daily energy expenditure, the energy intake required to match energy expenditure and maintain the new, lower “settling point” may be more feasible for weight-reduced individuals. For example, in a cross-sectional sample of weight-loss maintainers, it was found that energy expended from physical activity was significantly higher compared with non-weight-reduced individuals of a similar BMI [105]. Furthermore, strategies to dissipate negative preconceptions about physical activity and to meet people where they are at are needed. This may be achieved through supporting autonomy, focusing on exercise enjoyment, allowing all movement to “count” toward exercise goals, increasing access in our environment, and initiating a shift toward language of “movement” and “activity” rather than “exercise” [106].

It is also possible that WLM interventions that are separate and distinct from a weight-loss intervention may have greater efficacy. As already reviewed, the bulk of the literature provides quite sobering data on long-term WLM for most. These data are exclusively based on study designs that follow people from baseline through a weight-loss phase and then for several months for follow-up assessments (typically 12–24 months). By contrast, studies that have recruited people after weight loss into a program specifically designed for WLM have quite different results and show greater success [107, 108].

PRECISION TREATMENT FOR WLM

One reason WLM has proven difficult is due to individual differences in genetics and how people interact with the environment. Yet, the question remains: is it possible to match a personalized treatment to an individual? Human biology is complex and is compounded by the complexity of food that is made up of many nutritive and nonnutritive components that humans do not perceive when eating. These make predicting how people will respond challenging; however, by studying links between who we are (including our genetics, microbiome, metabolome, age, sex), the food that we eat, the context in which we eat (including sleep, physical activity, meal ordering, eating speed, time of day of meal), and the reason we make the dietary choices that we make, it may be possible to move toward more personalized treatments [109]. The NIH recently launched a study called Nutrition for Precision Health powered by All of US, which is a large step toward personalized nutrition (https://commonfund.nih.gov/nutritionforprecisionhealth).

Common obesity is a polygenic disease in which approximately 50% of interindividual variability in susceptibility can be explained by genetics, whereas the other 50% is due to environmental contribution [110]. Genome-wide association studies have identified over 1500 genetic variants associated with obesity-related outcomes, mostly BMI. Tissue enrichment analyses that compare gene expression of genes near these BMI-associated variants with that of genes not near these variants have highlighted the brain as the key organ involved in body weight regulation. Yet, the translation of a genetic variant associated with BMI to new insights into pathways underlying body weight regulation has been challenging. Furthermore, polygenic risks scores that aggregate all BMI-associated variants into one score to assess people’s genetic susceptibility to obesity explain up to 12% of the variation in BMI, but do not have a high predictive power for determining who is at risk for excessive weight gain [110]. The difficulty in variant-to-function translation and the limited predictive ability of genetic risk scores may be ascribed to the use of a simple metric, BMI, to define obesity. Because of the simplicity of this metric, it is no surprise that obesity is a heterogenous condition. Specifically, two individuals that have obesity (and even have exactly the same high BMI) may differ in the underlying (biological) causes of their weight gain. They may also differ in the presentation of the disease, its prognosis, the complications, and the response to treatment. To account for this heterogeneity, there is a growing interest to subclassify obesity in smaller, more homogenous subtypes. So far, subclassifications have been predominantly performed based on clinical features present in individuals that have obesity (i.e., phenotypic subclassification) [111–113]. With the increasing number of genetic variants associated with obesity, genetic subclassification has become possible. A key advantage of subclassifications that are based on genetic variants is that they may reveal new insights in the etiology of the disease and its subtypes. In addition, genetic subclassification can be done early on in life, before the onset of disease, allowing for timely prevention. Researchers used this multitrait approach and identified 62 variants, including MTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), PPARG (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma), and VEGFA (vascular endothelial growth factor A), for which enrichment analyses point to a key role of adipose tissue and adipocyte biology in the uncoupling of obesity from its comorbidities. This is in stark contrast to the enrichment analyses performed for BMI-only associated variants, which point to the brain [114]. An association with this sort of specificity is more likely to allow us to predict from birth who is more likely to develop a similar phenotype.

The wealth of data that modern technology affords has provided new aspects of phenotype that may better predict how individuals respond to the obesogenic environment. The ZOE PREDICT trial (Personalized Responses to Dietary Composition Trial-1), a large-scale nutritional study investigating individual metabolic responses, used clinical studies with over 1000 participants with at-home data; remote technologies, such as stool collection (microbiome testing); blood spot sampling; twin studies; diet logging; physical activity and sleep monitoring; and machine learning to determine how people respond to food consumption [109]. Researchers were able to predict about 70% of the variability in postprandial glucose responses based on multiple phenotypic inputs (including genetic, microbiome, and metabolomic factors), lifestyle factors of the participants, and food they ate [109]. Additionally, by using continuous glucose monitors, investigators showed that people vary in their postprandial blood glucose decline. Those with larger dips (2–4 h after a meal) feel less full and consume more calories than those with smaller postprandial declines in glucose [115]. In another study that measured individual phenotypes through blood tests, microbiome genotyping, and food diaries, participants had a better response to a personalized diet when compared with Mediterranean diet [116]. Common cardiometabolic biomarkers, including glycated hemoglobin, triglycerides, and cholesterol, were all reduced after 3 months of treatment with personalized diets [116]. Furthermore, in preliminary studies using phenotypes of appetite and energy expenditure, personalized pharmaceutical interventions were shown to improve weight loss [111, 117].

Although there may be great value in precision treatment, especially for the treatment of obesity and WLM, caution is also warranted. Personalized treatment has the potential to favor those who are more affluent and marginalize lower socioeconomic levels and must not be allowed to widen disparities. Additionally, the modern nutrition landscape is littered with misinformation, pseudoscience, and fad diets that promise to hold the key to weight loss. For instance, although certain species of gut bacterium have been associated with favorable or unfavorable blood glucose, blood lipid, and cardiovascular health and may play a role in WLM [118], there is no predictive value in the data and no diets have been developed that are matched to an individual’s microbiome. Whether personalized treatment for weight management is at a point where it can be widely used is debatable, but advances in technology may bring it within reach sooner than we think. It is imperative that phenotypic, dietary, and “real-time” lifestyle data are collected at a scale, precision, resolution, breadth, and depth to implement meaningful personalized advice.

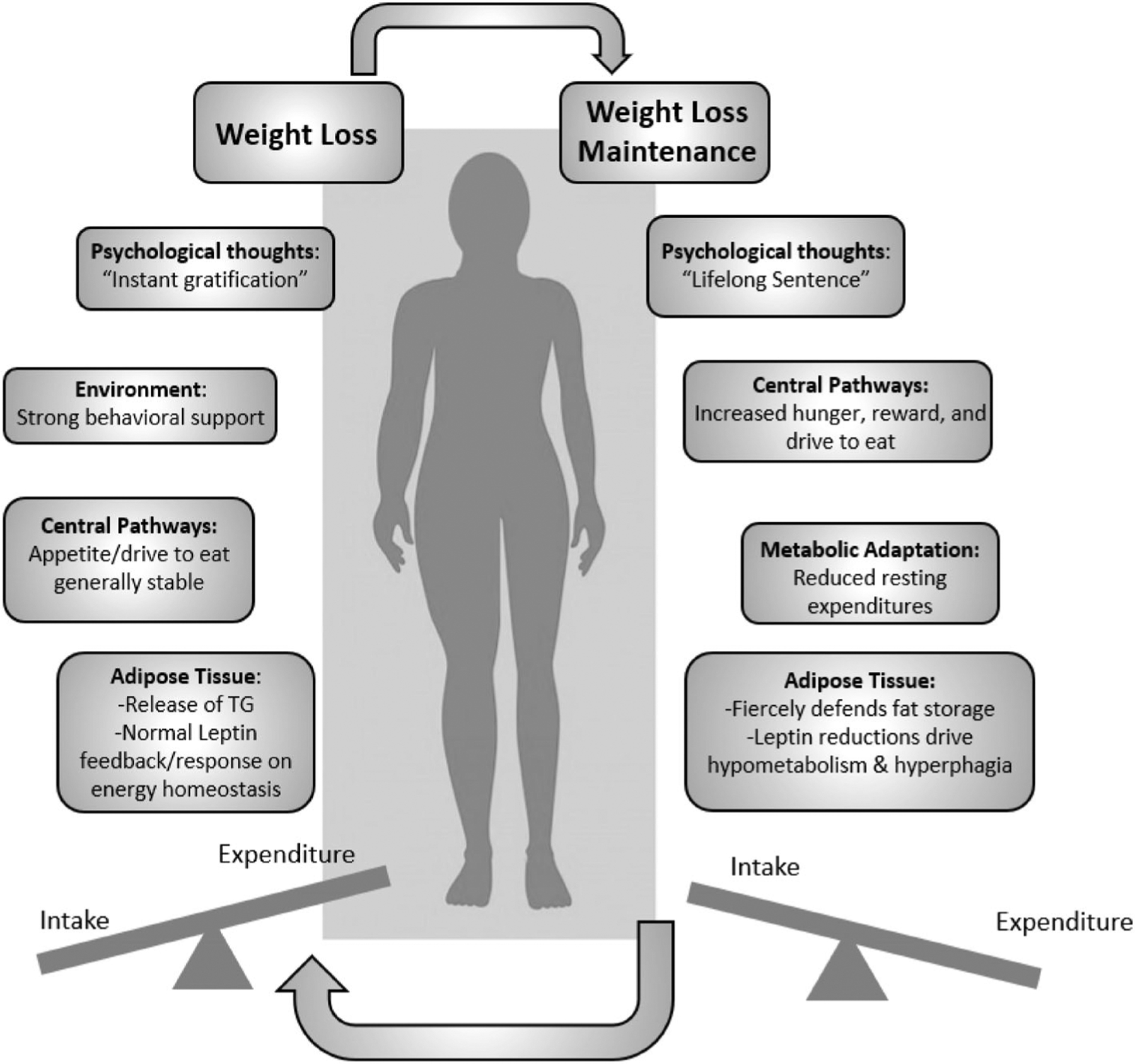

FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS IN WLM

The consensus of the symposium was that there is a critical need to understand the pathophysiology behind how and why weight loss triggers metabolic adaptations that promote the commonly seen weight regain. There are clear physiological differences between obesity, during weight loss, and the weight-reduced state. In the design phase, studies should clearly differentiate between the three conditions of obesity, weight loss, or WLM. Understanding the biology, internal physiology, and external environments that oppose how the weight-reduced state continues to drive an intense futile cycle of weight loss and regain is crucial (Figure 4). Clinical trials and basic science aimed to understand the physiological and molecular drivers of weight stability and differences between weight loss and regain are needed. Biomarkers and external factors that can predict an individual’s response to weight regain would be course-changing to prescribe individualized, adaptive, and just-in-time interventions before weight-loss benefits are abolished.

FIGURE 4.

The futile cycle of weight loss and weight-loss maintenance. TG, triglycerides.

It was also discussed that an individual’s metabolic “fingerprint” may develop in utero. Longitudinal studies starting from preconception and following through to adulthood are the ultimate model. Until then, early discovery of metabolic phenotypes and homeostatic/hedonic development are needed. The biological “reprogramming” following bariatric surgery is perplexing and may serve as an additional model of weight-loss physiology.

Studies that focus on optimization of interventions specific to WLM will aid in our understanding of which intervention components foster lifelong adoption. Last, interventions that leverage stakeholder input and the needs of communities will ensure that interventions are acceptable, feasible, and sustainable for real-world settings.

Understanding the physiology of the weight-reduced state is a priority of leading scientific agencies, including the NIH. In 2019, NIDDK hosted a workshop discussing the physiology of the weight-reduced state [5, 119–122] and shortly after, released a funding opportunity announcement (https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-DK-19-017.html) aimed to elucidate the complex physiological underpinnings of WLM. In 2021, the Physiology of the Weight Reduced State (POWeRS) consortium was formed, including Columbia University, Drexel University, University of Pennsylvania, and Tufts University. The POWeRS trials (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05748158) will aim to understand the molecular, metabolic, and behavioral mechanisms before and for 12 months after initial weight loss. Over 200 participants will enroll into a weight-loss intervention akin to previous trials (DPP, Look AHEAD, and CALERIE) with the goal of achieving ≥7% weight loss over 37 weeks. Following weight loss, the intervention is stopped, and the study participants are evaluated at 4 and 12 months for the primary outcome of weight regain. Tissue biospecimens will allow for molecular phenotyping in the weight-reduced state. This study aims to provide rigorous novel information regarding the mechanisms and physiological state of WLM. Until this large, collaborative project is complete, rigorous clinical trials and mechanistic work using animal models should continue to investigate weight loss and WLM. Without such trials, obesity will continue to impose an enormous social and economic burden on families and communities and to strain public health resources. Importantly, scientists in the field of obesity and its associated diseases should provide rigorous data to lawmakers to implement novel public health policies to curb the dramatic increase in the deterioration of the health of our populations. We cannot afford to have a decrease in health span and life-span after all the scientific progress achieved in the 20th century.

CONCLUSION

Overall, this summary presents the accumulating evidence for the environmental, behavioral, and physiological mechanisms involved within the weight-reduced state. Obesity itself is a complex disease, but its multiple impacts on health and wellbeing justify a radical shift toward prevention and treatment to reverse the current trends. Understanding the biological and psychosocial responses to, as well as the environmental predictors of, weight loss is the key to progressing obesity research. Future population, clinical, and molecular research should begin to unravel the complexities involved in this unique physiological state and develop inclusive interventions that leverage personalized medicine. Collaboration across sectors is crucial for the advancement of the field and, in particular, systems science methods may help to explain the bigger picture of weight regain after weight loss. The scientific community has achieved success in weight-loss science, but the future of obesity research must focus on the weight-reduced state.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Gary D. Foster is an employee and shareholder WW International. Sarah E. Berry reports consultancy and options for ZOE Ltd. The other authors declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines/The Obesity Society. Expert panel report: guidelines (2013) for the management of overweight and obesity in adults. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22(Suppl 2):S41–S410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loveman E, Frampton GK, Shepherd J, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of long-term weight management schemes for adults: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15(2):1–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:222S–225S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu T, Gao X, Chen M, van Dam RM. Long-term effectiveness of diet-plus-exercise interventions vs. diet-only interventions for weight loss: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2009;10(3):313–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aronne LJ, Hall KD, Jakicic JM, et al. Describing the weight-reduced state: physiology, behavior, and interventions. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29 (Suppl 1):S9–S24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stunkard A, McLaren-Hume M. The results of treatment for obesity: a review of the literature and report of a series. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1959;103(1):79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marlatt KL, Redman LM, Burton JH, Martin CK, Ravussin E. Persistence of weight loss and acquired behaviors 2 y after stopping a 2-y calorie restriction intervention. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(4):928–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson JW, Konz EC, Frederich RC, Wood CL. Long-term weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of US studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74(5):579–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schauer PR, Kashyap SR, Wolski K, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(17):1567–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes – 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):641–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magro DO, Geloneze B, Delfini R, Pareja BC, Callejas F, Pareja JC. Long-term weight regain after gastric bypass: a 5-year prospective study. Obes Surg. 2008;18(6):648–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tam CS, Berthoud HR, Bueter M, et al. Could the mechanisms of bariatric surgery hold the key for novel therapies? Report from a Pennington scientific symposium. Obes Rev. 2011;12(11):984–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller MJ, Bosy-Westphal A, Heymsfield SB. Is there evidence for a set point that regulates human body weight? F1000 Med Rep. 2010; 2:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tam J, Fukumura D, Jain RK. A mathematical model of murine metabolic regulation by leptin: energy balance and defense of a stable body weight. Cell Metab. 2009;9(1):52–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall KD, Heymsfield SB. Models use leptin and calculus to count calories. Cell Metab. 2009;9(1):3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan PJ, Ross AW, Mercer JG, Barrett P. What can we learn from seasonal animals about the regulation of energy balance? Prog Brain Res. 2006;153:325–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blundell JE, Gibbons C, Beaulieu K, et al. The drive to eat in homo sapiens: energy expenditure drives energy intake. Physiol Behav. 2020;219:112846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ravussin E, Redman LM. Metabolic adaptation: is it really an illusion? Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;112(6):1653–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Redman LM, Smith SR, Burton JH, Martin CK, Il’yasova D, Ravussin E. Metabolic slowing and reduced oxidative damage with sustained caloric restriction support the rate of living and oxidative damage theories of aging. Cell Metab. 2018;27(4):805–815.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leibel RL, Rosenbaum M, Hirsch J. Changes in energy expenditure resulting from altered body weight. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(10): 621–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenbaum M, Hirsch J, Gallagher DA, Leibel RL. Long-term persistence of adaptive thermogenesis in subjects who have maintained a reduced body weight. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(4):906–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johannsen DL, Knuth ND, Huizenga R, Rood JC, Ravussin E, Hall KD. Metabolic slowing with massive weight loss despite preservation of fat-free mass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(7):2489–2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fothergill E, Guo J, Howard L, et al. Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after “The Biggest Loser” competition. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(8):1612–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knuth ND, Johannsen DL, Tamboli RA, et al. Metabolic adaptation following massive weight loss is related to the degree of energy imbalance and changes in circulating leptin. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22(12):2563–2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lecoultre V, Ravussin E, Redman LM. The fall in leptin concentration is a major determinant of the metabolic adaptation induced by caloric restriction independently of the changes in leptin circadian rhythms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(9):E1512–E1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo J, Brager DC, Hall KD. Simulating long-term human weight-loss dynamics in response to calorie restriction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018; 107(4):558–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polidori D, Sanghvi A, Seeley RJ, Hall KD. How strongly does appetite counter weight loss? Quantification of the feedback control of human energy intake. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(11):2289–2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenbaum M, Murphy EM, Heymsfield SB, Matthews DE, Leibel RL. Low dose leptin administration reverses effects of sustained weight-reduction on energy expenditure and circulating concentrations of thyroid hormones. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002; 87(5):2391–2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sumithran P, Prendergast LA, Delbridge E, et al. Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365(17):1597–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sclafani A, Springer D. Dietary obesity in adult rats: similarities to hypothalamic and human obesity syndromes. Physiol Behav. 1976; 17(3):461–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hill JO. Body weight regulation in obese and obese-reduced rats. Int J Obes (Lond). 1990;14:31–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin BE, Keesey RE. Defense of differing body weight set points in diet-induced obese and resistant rats. Am J Physiol. 1998;274(2): R412–R419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rolls BJ, Rowe EA, Turner RC. Persistent obesity in rats following a period of consumption of a mixed, high energy diet. J Physiol. 1980; 298:415–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo J, Jou W, Gavrilova O, Hall KD. Persistent diet-induced obesity in male C57BL/6 mice resulting from temporary obesigenic diets. PloS One. 2009;4(4):e5370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berthoud HR, Morrison C. The brain, appetite, and obesity. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:55–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luquet S, Perez FA, Hnasko TS, Palmiter RD. NPY/AgRP neurons are essential for feeding in adult mice but can be ablated in neonates. Science. 2005;310(5748):683–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu Q, Boyle MP, Palmiter RD. Loss of GABAergic signaling by AgRP neurons to the parabrachial nucleus leads to starvation. Cell. 2009; 137(7):1225–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krashes MJ, Koda S, Ye C, et al. Rapid, reversible activation of AgRP neurons drives feeding behavior in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(4): 1424–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Y, Lin YC, Zimmerman CA, Essner RA, Knight ZA. Hunger neurons drive feeding through a sustained, positive reinforcement signal. Elife. 2016;5:e18640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldstein N, McKnight AD, Carty JRE, Arnold M, Betley JN, Alhadeff AL. Hypothalamic detection of macronutrients via multiple gut-brain pathways. Cell Metab. 2021;33(3):676–687.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Porte D Jr, Seeley RJ, Baskin DG. Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature. 2000;404(6778): 661–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beutler LR, Corpuz TV, Ahn JS, et al. Obesity causes selective and long-lasting desensitization of AgRP neurons to dietary fat. Elife. 2020;9:e55909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hare TA, O’Doherty J, Camerer CF, Schultz W, Rangel A. Dissociating the role of the orbitofrontal cortex and the striatum in the computation of goal values and prediction errors. J Neurosci. 2008;28(22):5623–5630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berthoud HR, Munzberg H, Morrison CD. Blaming the brain for obesity: integration of hedonic and homeostatic mechanisms. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(7):1728–1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farooqi IS, Bullmore E, Keogh J, Gillard J, O’Rahilly S, Fletcher PC. Leptin regulates striatal regions and human eating behavior. Science. 2007;317(5843):1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Basolo A, Hohenadel M, Ang QY, et al. Effects of underfeeding and oral vancomycin on gut microbiome and nutrient absorption in humans. Nat Med. 2020;26(4):589–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heymsfield SB, Smith J, Kasriel S, et al. Energy malabsorption: measurement and nutritional consequences. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34(9): 1954–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jumpertz R, Le DS, Turnbaugh PJ, et al. Energy-balance studies reveal associations between gut microbes, caloric load, and nutrient absorption in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(1):58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Backhed F, Manchester JK, Semenkovich CF, Gordon JI. Mechanisms underlying the resistance to diet-induced obesity in germ-free mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(3):979–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444(7122):1027–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodrigues VF, Elias-Oliveira J, Pereira IS, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila and gut immune system: a good friendship that attenuates inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, and diabetes. Front Immunol. 2022;13:934695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aminian A, Zajichek A, Arterburn DE, et al. Association of metabolic surgery with major adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity. JAMA. 2019;322(13):1271–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sjostrom L Review of the key results from the Swedish obese subjects (SOS) trial – a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273(3):219–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Davies M, et al. Weight regain and cardiometabolic effects after withdrawal of semaglutide: the STEP 1 trial extension. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24(8):1553–1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moreland AM, Santa Ana CA, Asplin JR, et al. Steatorrhea and hyper-oxaluria in severely obese patients before and after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(5):1055–1067.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Odstrcil EA, Martinez JG, Santa Ana CA, et al. The contribution of malabsorption to the reduction in net energy absorption after long-limb Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(4):704–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Akalestou E, Miras AD, Rutter GA, le Roux CW. Mechanisms of weight loss after obesity surgery. Endocr Rev. 2022;43(1):19–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baboumian S, Pantazatos SP, Kothari S, McGinty J, Holst J, Geliebter A. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) of neural responses to visual and auditory food stimuli pre and post Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and sleeve gastrectomy (SG). Neuroscience. 2019;409:290–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scholtz S, Miras AD, Chhina N, et al. Obese patients after gastric bypass surgery have lower brain-hedonic responses to food than after gastric banding. Gut. 2014;63(6):891–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stefater MA, Perez-Tilve D, Chambers AP, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy induces loss of weight and fat mass in obese rats, but does not affect leptin sensitivity. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(7):2426–2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilson-Perez HE, Chambers AP, Sandoval DA, et al. The effect of vertical sleeve gastrectomy on food choice in rats. Int J Obes. 2013; 37(2):288–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Albaugh VL, He Y, Munzberg H, Morrison CD, Yu S, Berthoud HR. Regulation of body weight: Lessons learned from bariatric surgery. Mol Metab. 2022;68:101517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Evers SS, Shao Y, Ramakrishnan SK, et al. Gut HIF2alpha signaling is increased after VSG, and gut activation of HIF2alpha decreases weight, improves glucose, and increases GLP-1 secretion. Cell Rep. 2022;38(3):110270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seeley RJ, Chambers AP, Sandoval DA. The role of gut adaptation in the potent effects of multiple bariatric surgeries on obesity and diabetes. Cell Metab. 2015;21(3):369–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shin JH, Bozadjieva-Kramer N, Shao Y, et al. The gut peptide Reg3g links the small intestine microbiome to the regulation of energy balance, glucose levels, and gut function. Cell Metab. 2022;34:1765–1778.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guyenet SJ, Hall KD. Overestimated impact of lower-carbohydrate diets on total energy expenditure. J Nutr. 2021;151(8):2496–2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hall KD, Bemis T, Brychta R, et al. Calorie for calorie, dietary fat restriction results in more body fat loss than carbohydrate restriction in people with obesity. Cell Metab. 2015;22(3):427–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hall KD, Chen KY, Guo J, et al. Energy expenditure and body composition changes after an isocaloric ketogenic diet in overweight and obese men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104(2):324–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hall KD, Guo J. Obesity energetics: body weight regulation and the effects of diet composition. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(7):1718–1727.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hall KD, Guo J, Chen KY, et al. Methodologic considerations for measuring energy expenditure differences between diets varying in carbohydrate using the doubly labeled water method. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;109(5):1328–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hall KD, Guo J, Speakman JR. Do low-carbohydrate diets increase energy expenditure? Int J Obes (Lond). 2019;43(12):2350–2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hall KD, Guo J, Courville AB, et al. Effect of a plant-based, low-fat diet versus an animal-based, ketogenic diet on ad libitum energy intake. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):344–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hall KD, Ayuketah A, Brychta R, et al. Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: an inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell Metab. 2019;30(1):67–77.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chandrabose M, Rachele JN, Gunn L, et al. Built environment and cardio-metabolic health: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Obes Rev. 2019;20(1):41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dixon BN, Ugwoaba UA, Brockmann AN, Ross KM. Associations between the built environment and dietary intake, physical activity, and obesity: a scoping review of reviews. Obes Rev. 2021;22(4): e13171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smith M, Hosking J, Woodward A, et al. Systematic literature review of built environment effects on physical activity and active transport – an update and new findings on health equity. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stappers NEH, Van Kann DHH, Ettema D, De Vries NK, Kremers SPJ. The effect of infrastructural changes in the built environment on physical activity, active transportation and sedentary behavior – a systematic review. Health Place. 2018;53:135–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lam TM, Vaartjes I, Grobbee DE, Karssenberg D, Lakerveld J. Associations between the built environment and obesity: an umbrella review. Int J Health Geogr. 2021;20(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tewahade S, Berrigan D, Slotman B, et al. Impact of the built, social, and food environment on long-term weight loss within a behavioral weight loss intervention. Obes Sci Pract. 2023;9(3):261–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Clynes S, Moran A, Wolfson J, et al. A healthier retail food environment around the home is associated with longer duration of weight-loss maintenance among successful weight-loss maintainers. Prev Med. 2023;172:107536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Powell-Wiley TM, Baumer Y, Baah FO, et al. Social determinants of cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2022;130(5):782–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yeager R, Riggs DW, DeJarnett N, et al. Association between residential greenness and cardiovascular disease risk. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(24):e009117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Farmer N, Gutierrez-Huerta CA, Turner BS, et al. Neighborhood environment associates with trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) as a cardiovascular risk marker. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(8): 4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bergmans RS, Palta M, Robert SA, Berger LM, Ehrenthal DB, Malecki KM. Associations between food security status and dietary inflammatory potential within lower-income adults from the United States National Health and nutrition examination survey, cycles 2007 to 2014. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(6):994–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gowda C, Hadley C, Aiello AE. The association between food insecurity and inflammation in the US adult population. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(8):1579–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Broyles ST, Myers CA, Drazba KT, Marker AM, Church TS, Newton RL Jr. The influence of neighborhood crime on increases in physical activity during a pilot physical activity intervention in children. J Urban Health. 2016;93(2):271–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Swinburn BA, Kraak VI, Allender S, et al. The global Syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: the lancet commission report. Lancet. 2019;393(10173):791–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vandevijvere S, Jaacks LM, Monteiro CA, et al. Global trends in ultraprocessed food and drink product sales and their association with adult body mass index trajectories. Obes Rev. 2019;20(Suppl 2): 10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Reyes NR, Oliver TL, Klotz AA, et al. Similarities and differences between weight loss maintainers and regainers: a qualitative analysis. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(4):499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Williamson DA, Anton SD, Han H, et al. Early behavioral adherence predicts short and long-term weight loss in the POUNDS LOST study. J Behav Med. 2010;33(4):305–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Klem ML, Wing RR, McGuire MT, Seagle HM, Hill JO. A descriptive study of individuals successful at long-term maintenance of substantial weight loss. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66(2):239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Puhl RM, Quinn DM, Weisz BM, Suh YJ. The role of stigma in weight loss maintenance among U.S. Adults. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(5): 754–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wing RR, Papandonatos G, Fava JL, et al. Maintaining large weight losses: the role of behavioral and psychological factors. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(6):1015–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Varkevisser RDM, van Stralen MM, Kroeze W, Ket JCF, Steenhuis IHM. Determinants of weight loss maintenance: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2019;20(2):171–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ostendorf DM, Blankenship JM, Grau L, et al. Predictors of long-term weight loss trajectories during a behavioral weight loss intervention: an exploratory analysis. Obes Sci Pract. 2021;7(5):569–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Thomas JG, Bond DS, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR. Weight-loss maintenance for 10 years in the National Weight Control Registry. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(1):17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ostendorf DM, Lyden K, Pan Z, et al. Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behavior in successful weight loss maintainers. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2018;26(1):53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lowe MR. Self-regulation of energy intake in the prevention and treatment of obesity: is it feasible? Obes Res. 2003;11:44S–59S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lowe MR, Butryn ML, Zhang F. Evaluation of meal replacements and a home food environment intervention for long-term weight loss: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;107(1):12–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zenk SN, Wilbur J, Wang E, et al. Neighborhood environment and adherence to a walking intervention in African American women. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(1):167–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change. Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lillis J, Niemeier HM, Thomas JG, et al. A randomized trial of an acceptance-based behavioral intervention for weight loss in people with high internal disinhibition. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(12): 2509–2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Forman EM, Manasse SM, Butryn ML, Crosby RD, Dallal DH, Crochiere RJ. Long-term follow-up of the mind your health project: acceptance-based versus standard behavioral treatment for obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019;27(4):565–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Foright RM, Presby DM, Sherk VD, et al. Is regular exercise an effective strategy for weight loss maintenance? Physiol Behav. 2018;188:86–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ostendorf DM, Caldwell AE, Creasy SA, et al. Physical activity energy expenditure and total daily energy expenditure in successful weight loss maintainers. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019;27(3):496–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Segar M, Taber JM, Patrick H, Thai CL, Oh A. Rethinking physical activity communication: using focus groups to understand women’s goals, values, and beliefs to improve public health. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wing RR, Tate DF, Gorin AA, Raynor HA, Fava JL. A self-regulation program for maintenance of weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15): 1563–1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yancy WS Jr, Shaw PA, Reale C, et al. Effect of escalating financial incentive rewards on maintenance of weight loss: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1914393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Berry SE, Valdes AM, Drew DA, et al. Human postprandial responses to food and potential for precision nutrition. Nat Med. 2020;26(6): 964–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Loos RJF, Yeo GSH. The genetics of obesity: from discovery to biology. Nat Rev Genet. 2022;23(2):120–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Acosta A, Camilleri M, Shin A, et al. Quantitative gastrointestinal and psychological traits associated with obesity and response to weight-loss therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(3):537–546.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fagherazzi G, Zhang L, Aguayo G, et al. Towards precision cardiometabolic prevention: results from a machine learning, semi-supervised clustering approach in the nationwide population-based ORISCAV-LUX 2 study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):16056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lin Z, Feng W, Liu Y, et al. Machine learning to identify metabolic subtypes of obesity: a multi-center study. Front Endocrinol. 2021;12: 713592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Huang LO, Rauch A, Mazzaferro E, et al. Genome-wide discovery of genetic loci that uncouple excess adiposity from its comorbidities. Nat Metab. 2021;3(2):228–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wyatt P, Berry SE, Finlayson G, et al. Postprandial glycaemic dips predict appetite and energy intake in healthy individuals. Nat Metab. 2021;3(4):523–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ben-Yacov O, Godneva A, Rein M, et al. Personalized postprandial glucose response-targeting diet versus Mediterranean diet for glycemic control in prediabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(9):1980–1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Acosta A, Camilleri M, Abu Dayyeh B, et al. Selection of antiobesity medications based on phenotypes enhances weight loss: a pragmatic trial in an obesity clinic. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29(4): 662–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Asnicar F, Berry SE, Valdes AM, et al. Microbiome connections with host metabolism and habitual diet from 1,098 deeply phenotyped individuals. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):321–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Laughlin MR, Osganian SK, Yanovski SZ, Lynch CJ. Physiology of the weight-reduced state: a report from a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases workshop. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29(suppl 1):S5–S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Berthoud HR, Seeley RJ, Roberts SB. Physiology of energy intake in the weight-reduced state. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29(suppl 1): S25–S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]