Abstract

Background

Two Southeast Asian spider collections: that of Frances and John Murphy, now in the Manchester University Museum and the Deeleman collection, now at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden constituted the basis of this analysis of Chrysilla Thorell, 1887 and related genera. The latter collection also includes many thousands of spiders obtained by canopy fogging for an ecological project in Borneo by A. Floren.

New information

Some incongruences within the genera of the tribe Chrysillini are disentangled. The transfer of C.jesudasi Caleb & Mathai, 2014 from Chrysilla as type species of Phintelloides Kanesharatnam & Benjamin, 2019, based on analysis of molecular data is validated by morphology. An interesting new species known only from the forest canopy in Borneo, Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov, is described based on both male and female specimens. Distinguishing chrysilline genera is mostly based on traditional somatic characters, e.g., habitus, carapace and abdomen patterns, mouthparts, and genital organs. The utility of two character systems for distinguishing chrysilline genera is highlighted: 1) the presence of a flexible, articulating embolic tegular branch (etb) in combination with the conformation of the characteristic construction of the epigyne in Chrysilla and Phintelloides; 2) presence of red colour on carapace and abdomen of live males and females, in combination with abundant blue/violet/white iridescent scales such as in Chrysilla and Siler. The red colour usually gets lost in alcohol, hampering species identification of alcohol material. The genera Chrysilla and Phintelloides are redefined. Specimens of the heretofore unknown female of Chrysilla deelemani Prószyński & Deeleman-Reinhold, 2010 are described. The male and female of Chrysillalauta and male of C.volupe are redescribed. The genus Chrysilla is diagnosed and discriminated from PhintellaBösenberg & Strand, 1906, SilerSimon, 1889, Phintelloides Kanesharatnam & Benjamin, 2019 and Proszynskia Kanesharatnam & Benjamin, 2019. The structure of the female genital organ of Phintelloidesflavumi Kanesharatnam & Benjamin, 2019 is scrutinized and the generic placement of Phintelloides is discussed. Males and females of one of the most variable species, Phintelloidesversicolor (C. L. Koch, 1846) are redescribed. Phintelloidesmunita (Bösenberg & Strand, 1906) is removed from synonymy with P.versicolor. Phintellaleucaspis Simon 1903 (male, Sumatra) is synonymized with P.versicolor.

Biodiversity data are increasingly reliant on digital infrastructure. By linking physical specimens to digital representations of their associated data, we can lower barriers to information flow. Here we demonstrate a workflow whereby persistent identifiers (PIDs) in the form of DOIs issued by DataCite are assigned to specimens. Recognized taxa are identified by their catalog of life identifier, or by registration in ZooBank where no catalog of life identifier is available. We demonstrate the use of nanopublications, creating a series of machine readable, scientifically meaningful assertions regarding the provenance and identification of cited specimens. All human agents associated with the specimen data are linked to a persistent identifier issued by either ORCiD or Wikidata.

Keywords: Biodiversity informatics, canopy fogging, copulatory mechanics, discoloration, specimen preservation, tropical Asian jumping spiders

Introduction

Jumping spiders (family Salticidae) attract attention as a highly diverse taxon (>6600 species described across >680 genera, World Spider Catalog 2024) featuring colorful, day active, visually oriented species; this is especially true of the tropics. In some, such as the members of the tribe Chrysillini (Maddison 2015: 247), live specimens attract attention with sparkling colours: silvery white, violet, blue, green and red, often borne on iridescent scales and appressed setae on the integument of the carapace, abdomen and male palps. Unfortunately, colours may change or disappear altogether in alcohol preserved specimens. This can make preserved specimens and live animals of the same species appear so different that they are challenging to recognize as conspecifics. Compounding this taxonomic challenge, males and females are often dissimilar in habitus making it difficult to match sexes; a relatively low proportion of species are known from both sexes. It is not unusual to find species of Chrysillini that have had males and females described as separate species.

It is well known that in the tropics, fauna and flora are generally more diverse than in colder climates. The tropical rainforest, the most species-rich terrestrial habitat in the world, hosts the highest number of unknown, undescribed arthropod species. The forests of tropical Asia are among the world’s tallest, characterized by emergent trees such as Dipterocarpus. Such trees may grow up to a height of 40-80 meters. Perhaps 99% of the species known from tropical forests have been collected from the lower 2 meters. Although we lack a rigorous estimate of the degree to which the canopy fauna is distinct from that of the lowest stratum, collections from forest canopy are a rich source for novel discovery. This publication is the latest in a series based on the unique and remarkable collection of more than 10,000 spiders collected by A. Floren during a long-term ecological project on Borneo (van Dorp 2020). This collection includes an unknown number of remarkable species that are quite unlike relatives from the understorey (Floren and Deeleman-Reinhold 2005), or are geographically distant from their closest known relatives (Deeleman-Reinhold et al. 2016). It is clear from the many new discoveries derived from the modest samples available that these forests harbour a profusion of undiscovered species. In the face of intensifying anthropogenic environmental change, we hope that fundamental research on the biodiversity of this critical region can be supported. Contemporary practices in international taxonomic research emphasize data mobilization as a mechanism for maximizing value of biodiversity data. This means lowering technological and social barriers to sharing, aggregating, and applying data flexibly to serve a broad spectrum of stakeholders, and providing data resources and inspiration to future generations of scientists.

The genera of Chrysillini that have been selected for this study belong to the core group of genera, characterized by the presence of a tegular bump on the male pedipalp (Fig. 1a, Maddison 2015: 247). A phylogenetic study of the Chrysillini explored in part the evolution of their conspicuous coloration (Kanesharatnam and Benjamin 2019). The most eye-catching genera in the group, such as Chrysilla, Siler, Cosmophasis, and Orsima, exhibit iridescent colours (such as red, green, blue and violet) on setae and scales on the cephalothorax, abdomen and male palps. Others, such as Phintella, Phintelloides, and Proszynskia, express more modest colours (such as black, white, brown and yellow). Photos of live spiders (Fig. 2) can be found in the field guides of Borneo and Singapore (Koh and Bay 2019, Koh et al. 2022, Koh and Ming 2013), taxonomic publications (e.g., Caleb et al. 2018, Yamasaki et al. 2018), and online databases (Metzner 1996-2020, Prószyński 2016). It is clear that some genera in this group have been ill defined in the past as witnessed by the frequent transfer of species between genera. In particular, the genus Chrysilla has often been misinterpreted. For much of the history of Chrysilla, no species were known from both sexes. Female Chrysilla species have an epigyne with a characteristic structure. Chrysilla are usually sexually dimorphic; C.acerosa Wang & Zhang, 2012 is an exception. Kanesharatnam and Benjamin (2019) recently established the genus Phintelloides for a set of new species from Sri Lanka, revealing a remarkable radiation. Phintelloides species are united by putative synapomorphies, such as specific black and white patterns on the carapace, the shape of the tegulum in the male palp, and the path of the copulatory ducts of the epigyne.

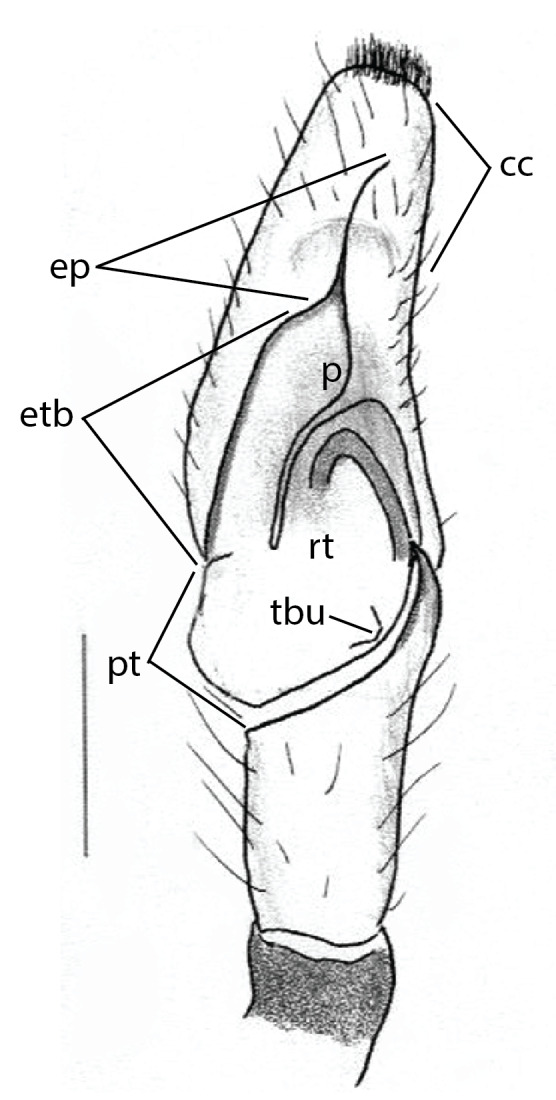

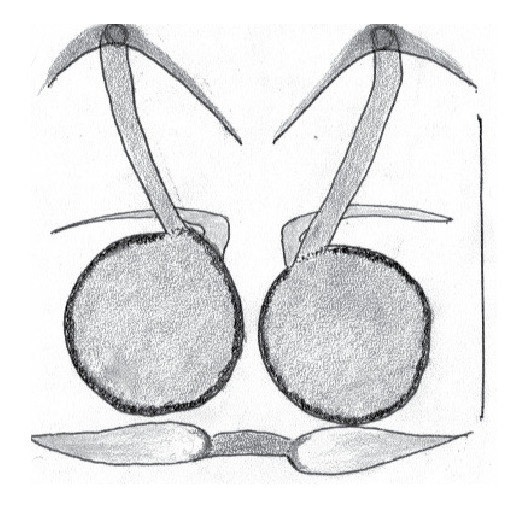

Annotated illustrations and photographs of male pedipalp in Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887

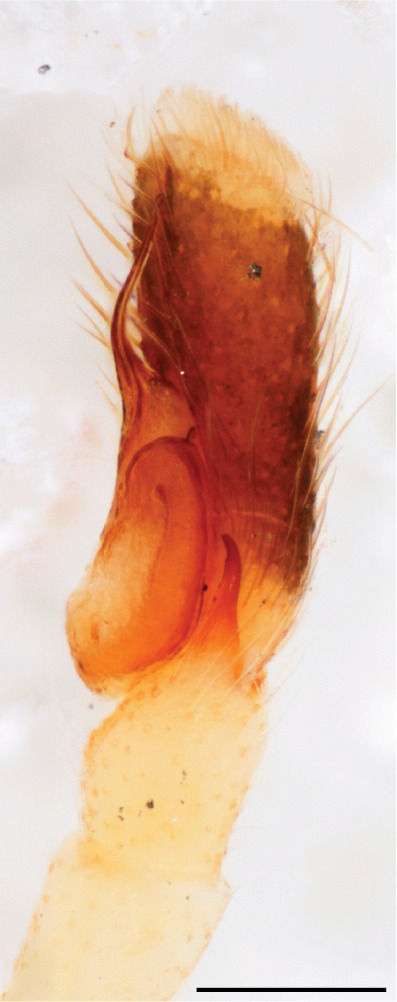

Figure 1a.

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887, left male pedipalp, ventral view cc cymbium cap ep embolus proper etb embolar tegular branch p distal projection of embolar tegular branch beyond retrolateral lobe of tegulum excluding embolus proper pt proximal lobe of tegulum rt retrolateral lobe of tegulum tbu tegular bump. Scale bar: 0.3 mm

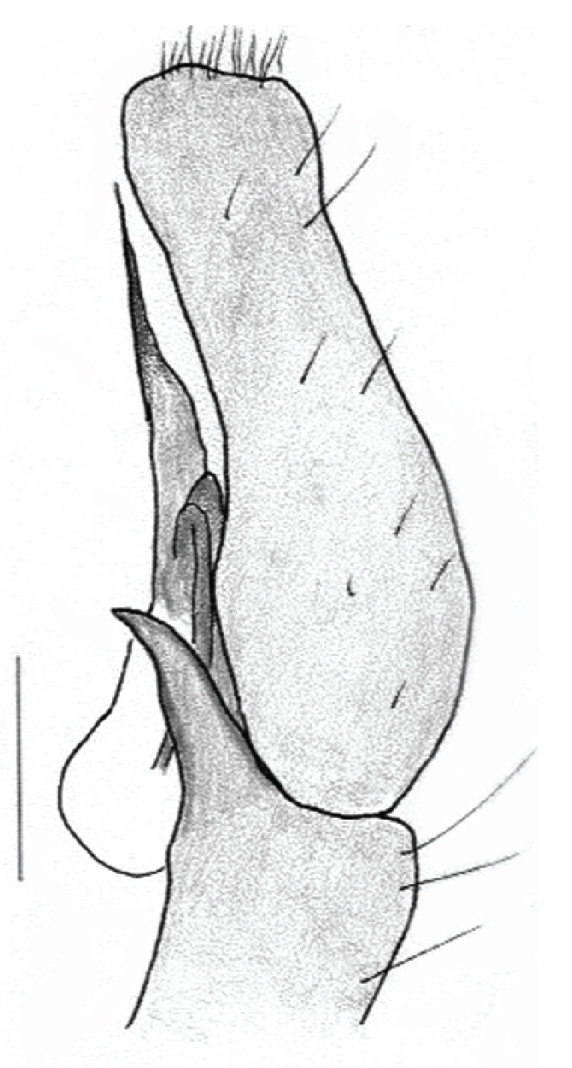

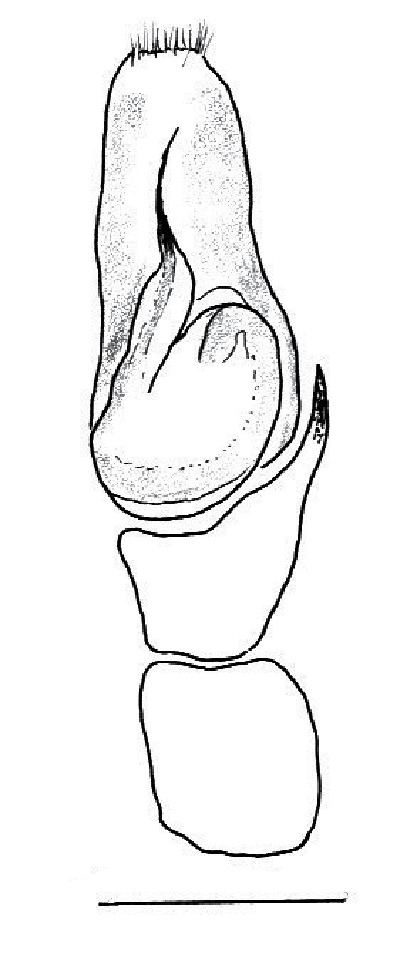

Figure 1b.

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887, left male pedipalp, retrolateral view. Scale bar: 0.3 mm

Figure 1c.

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887, ventral view, CM 15726, scale bar 0.2 mm

Figure 1d.

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887, retrolateral view, CM 15726, scale bar 0.2 mm

Selected images of Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887 reproduced from field guides and taxonomic literature showing fresh specimens and animals in living color

Figure 2a.

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887, Kanesharatnam and Benjamin, 2019, fig. 19A, male habitus, dorsal view. Scale bar 1 mm

Figure 2b.

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887, Koh et al., 2022, p. 347, live female, reproduced with permission, photo credit Paul Y.C. Ng

Figure 2c.

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887, Koh et al., 2022, p. 347, live male, reproduced with permission, photo credit Melvyn Yeo

Figure 2d.

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887, Koh et al., 2022, p. 347, live male, reproduced with permission, photo credit Melvyn Yeo

Colour pattern can be useful for species identification in such flamboyant spiders. Unfortunately, there is an inconvenient discrepancy between colours in live or freshly preserved specimens, and specimens that have been preserved in alcohol for some time. In most cases, we found that long preserved specimens (for example, >20 years) had lost nearly all colour. Red is among the colours most prone to disappearing in alcohol. Label data sometimes record color notes. Red areas visible on photographs of live animals may appear in preserved specimens as bare, pale brown, usually without any setae, hairs or scales at all.

Pigment colouration can be supplemented by regions with tiny iridescent multicolored scales and flattened setae. Several of the alcohol preserved specimens we examined were swimming in clouds of floating colourless scales of various size. Some iridescent scales bearing blue, violet, or green can be retraced on the teguments of carapace and abdomen but the colours were not always the same as that on photos; in both live and alcohol specimens, colours may change when shifting direction of viewing or change of position of light source. Iridescent blue and violet usually are associated with round scales, the size of these scales may differ on different parts of the body.

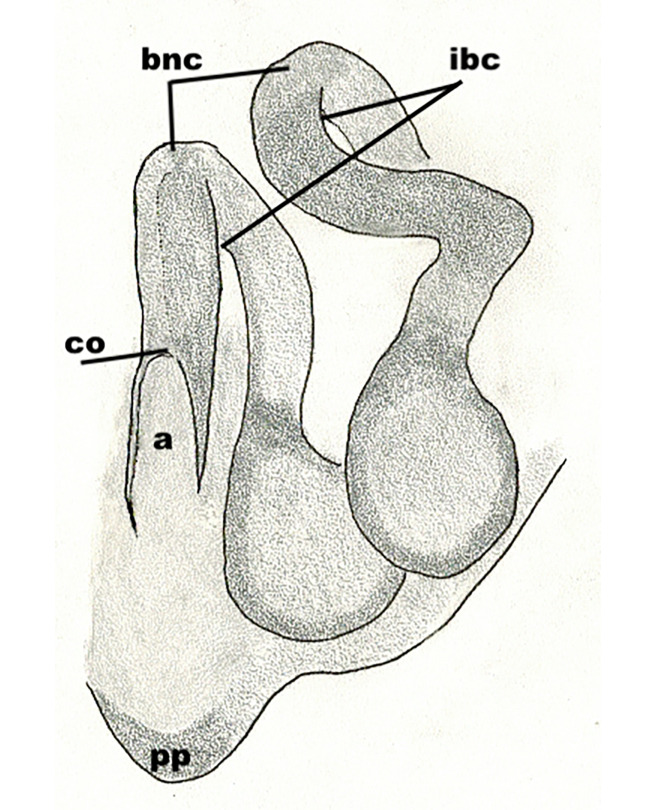

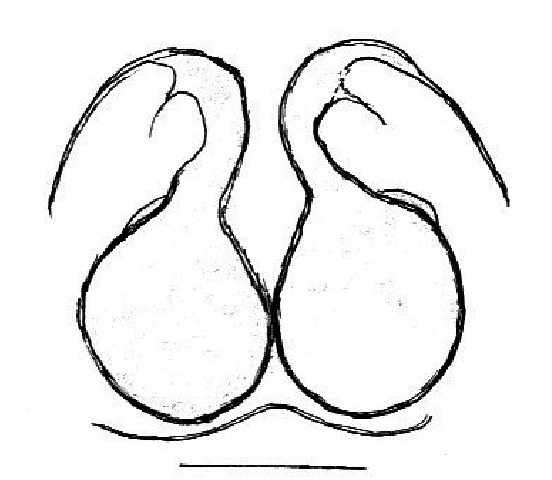

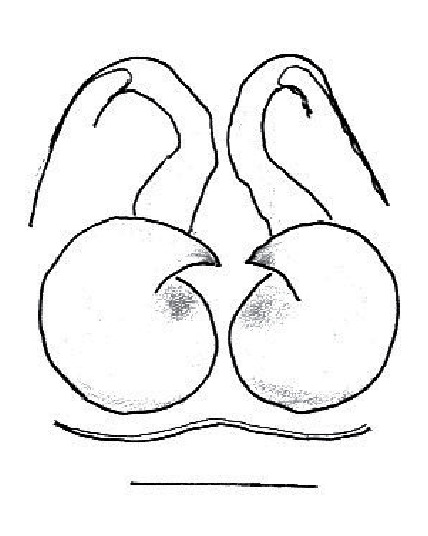

Copulatory mechanics in Chrysillaand Phintelloides

The male pedipalp of Chrysillaand Phintelloidesfeatures an atypical configuration. The tegulum is cleft into pro- and retrolateral parts: the prolateral branch we call embolar tegular branch (etb), with the embolus proper (ep) sitting on top; the base of the etb is attached dorsally, hidden by the larger retrolateral part (rt) containing the U-shaped spermduct-loop (sdl). The etb is long and flexible, freely movable, articulated at the base with the proximal tegular lobe (pt). This can be ascertained by manual examination with fine forceps and needle. The structure of the epigyne is likewise unusual, having copulatory ducts distally diverging as a bird-neck-shaped curve (bnc) with often inflated walls (possibly glands?) directed outwards, ending as an open bird’s beak (here called atrium, a); it lacks a distinct copulatory opening. Also, the pockets in the posterior ridge of the epigyne (pp) are rigid and probably play a role in anchoring the proximal part of the palp.

In search for the copulatory opening, CLD-R separated a palp and a cleared epigyne from specimens of Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov. and of Chrysillalauta (Figs 5, 16) and an epigyne of Phintelloidesflavumi (Fig. 11) and manipulated them, measuring the lengths and widths testing if these would allow a transfer of sperm into the spermatheca by introducing the tegulum and embolus inside the vulva (Figs 5, 16; tegulum in yellow, etb in red). In each species, the length of the embolus proper proved to match the length of the copulatory duct.

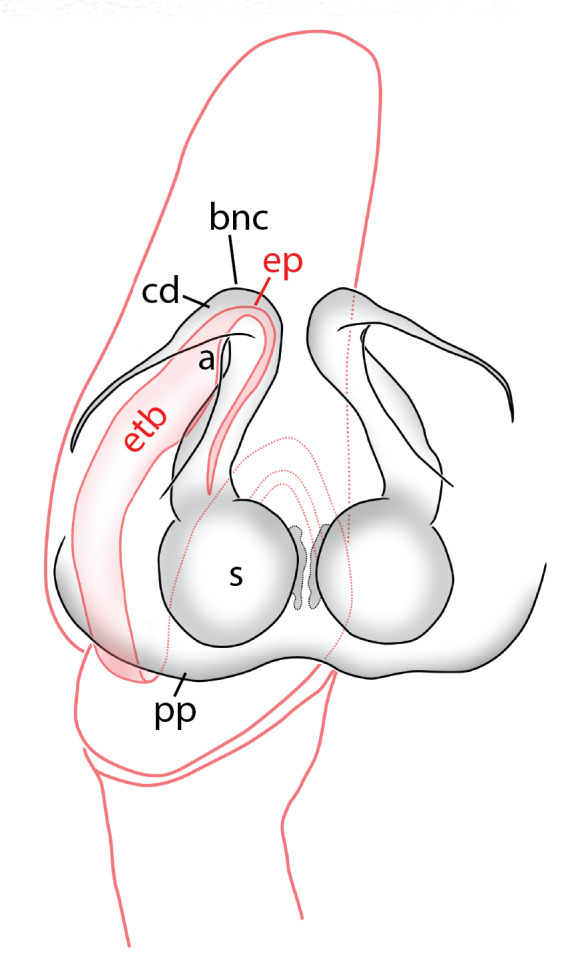

Figure 5.

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887, schematic illustrations showing hypothetical interaction between male and female genitalia a atrium bnc bird’s neck curve cd copulatory duct ep embolus proper etb embolar tegular branch pp posterior pockets s spermatheca

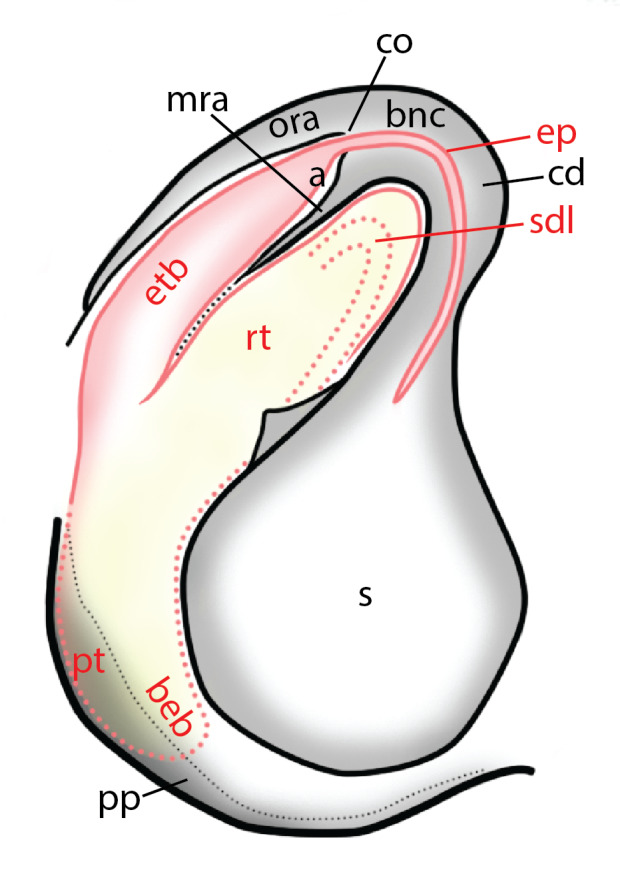

Figure 16.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., schematic illustrations showing hypothetical interaction between male and female genitalia a atrium beb base of embolar tegular branch bnc bird’s neck curve cd copulatory duct co copulatory opening ep embolus proper etb embolar tegular branch mra median rim of atrium ora outer rim of atrium pp posterior pockets pt proximal lobe of tegulum rt retrolateral lobe of tegulum s spermatheca sdl sperm duct loop

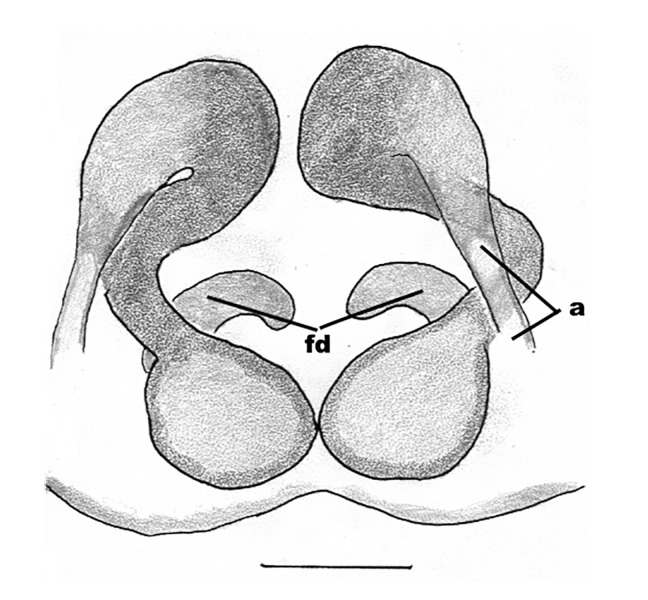

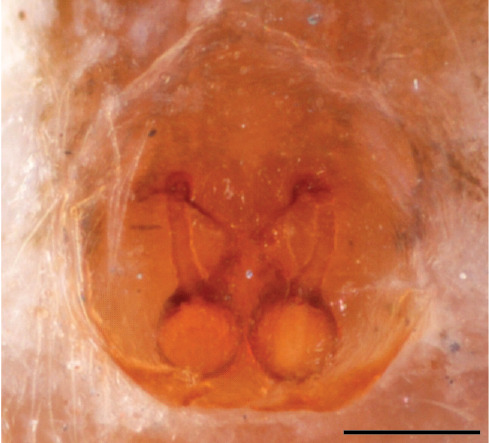

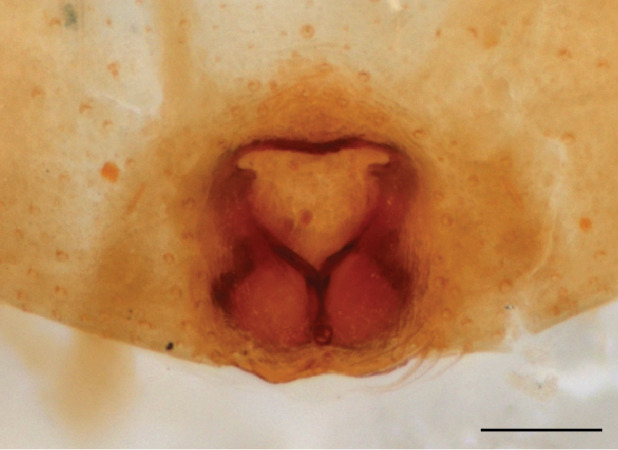

Phintelloidesflavumi Kanesharatnam & Benjamin, 2019, photographs and illustrations of female reproductive structures

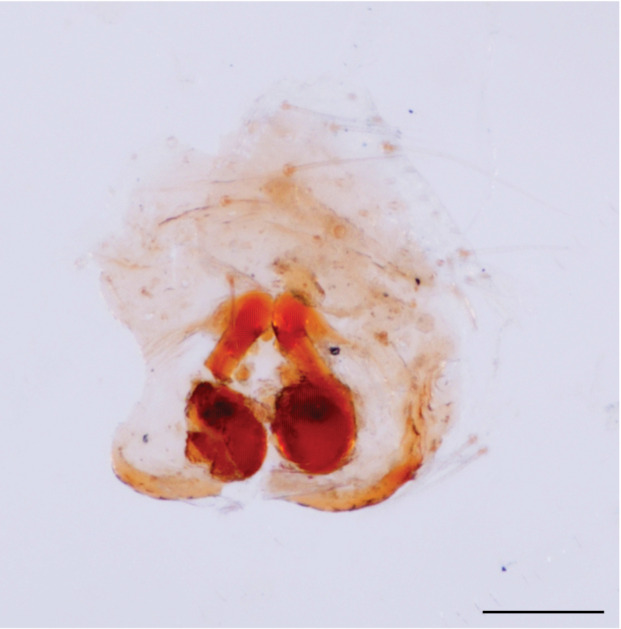

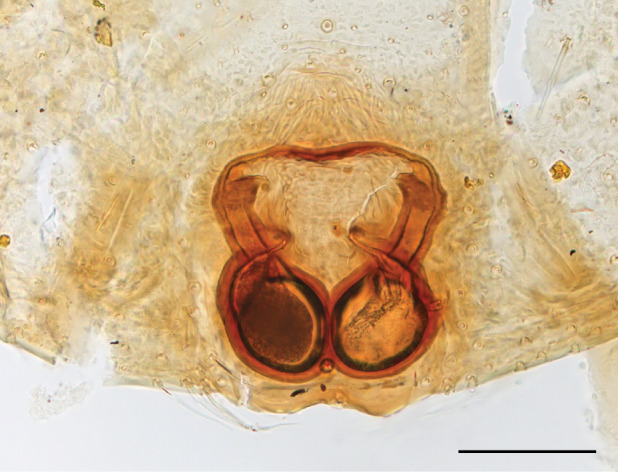

Figure 11a.

Phintelloidesflavumi Kanesharatnam & Benjamin, 2019, female vulva, dorsal view, RMNH.ARA.18250

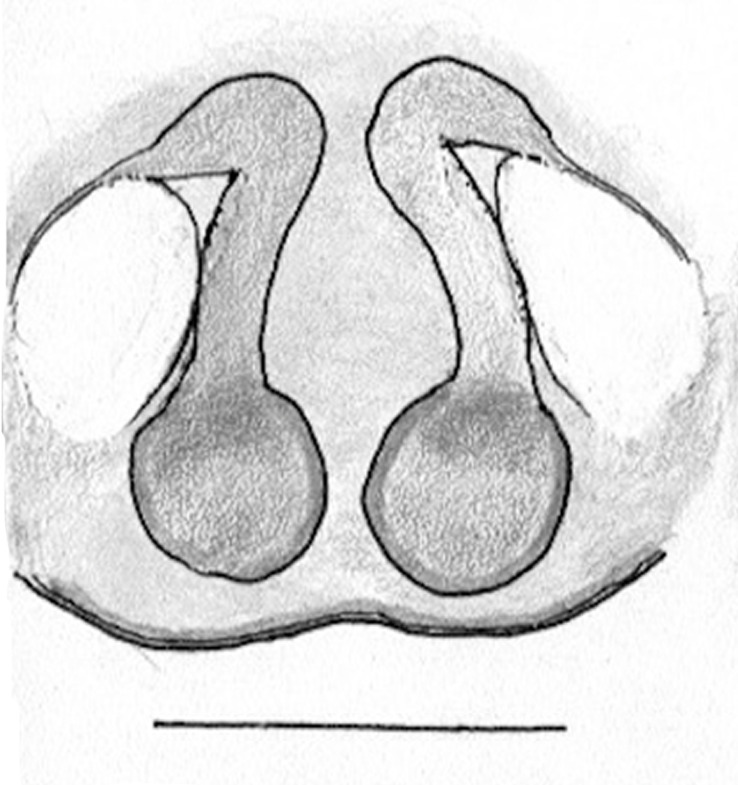

Figure 11b.

Phintelloidesflavumi Kanesharatnam & Benjamin, 2019, female vulva, dorsal view, illustration a atrium fd ferilization ducts. Scale bar 0.1 mm

Figure 11c.

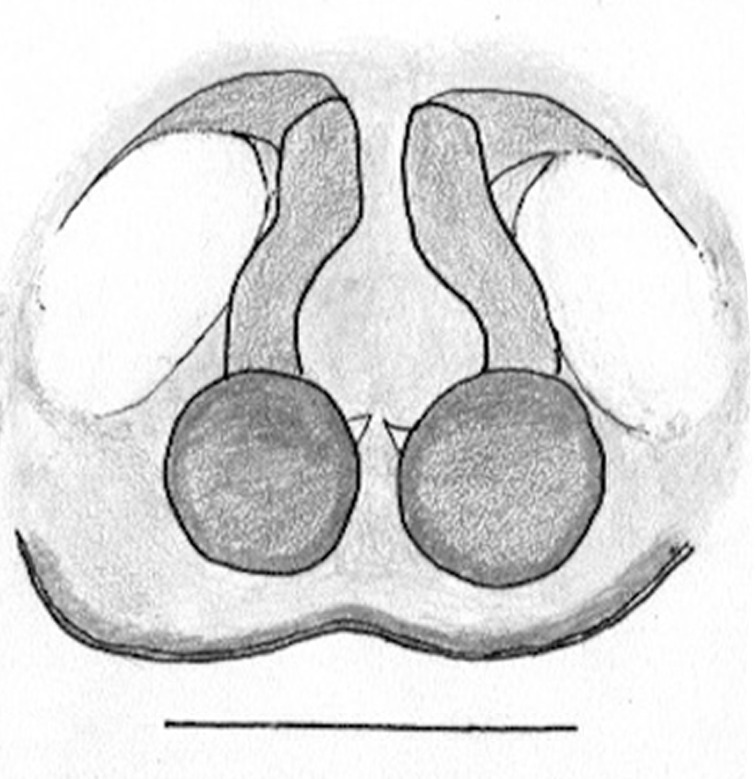

Phintelloidesflavumi Kanesharatnam & Benjamin, 2019, female vulva, oblique view, RMNH.ARA.18250

Figure 11d.

Phintelloidesflavumi Kanesharatnam & Benjamin, 2019, female vulva, oblique view, illustration a atrium bnc bird’s neck curve co copulatory opening ibc inner bend of bird’s-neck shaped curve pp posterior pockets

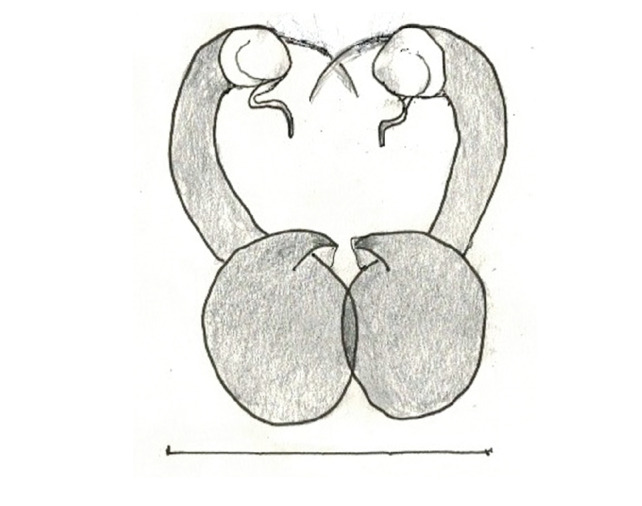

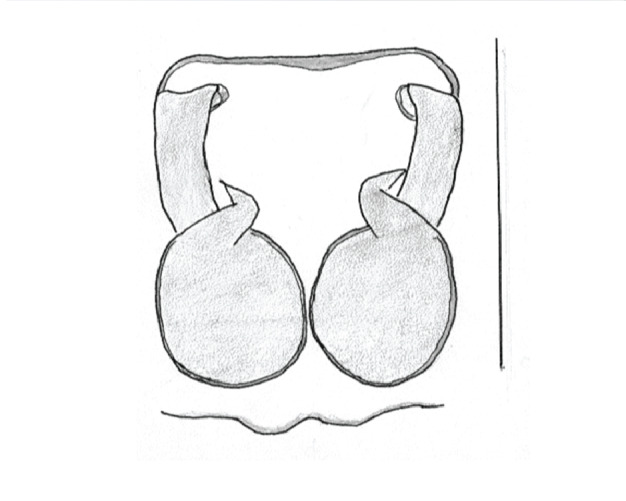

In females of P.scandens viewed from the ventral aspect, two round adjacent excavations are seen on in the left and the right part of the epigyne (Figs 11c, d, 16). The outer one, the atrium (Fig. 16: a), confined between the outer (ora) and the inner (mra) atrium rim, encompasses the copulatory opening (co) and during copulation hosts the etb. The inner excavation is separated from the atrium by the median rim (mra) and is confined by the proximal wall of the bird-neck (bnc). It is blind and matches the shape and size of the retrolateral part of the tegulum (rt). The total length of the tegulum just about equals the distance between the pockets in the posterior ridge in the epigyne (pp) and the inner excavation. The shape of the distal part of the etb matches the shape of the atrium and its length equals the length of the ora and mra so that the embolus proper (ep) can be pushed into the copulatory opening. This supports the idea that during copulation the tegulum is lengthwise pinched between the posterior pocket and the inner excavation and provides a grip for the stability of the male palp while pushing the etb into the atrium and the embolus into the copulatory ducts.

In P.flavumi, as can be seen in the vulva oriented in oblique ventro-lateral view (Fig. 11c, d), the atrium is clearly seen in the shape of a funnel which would be suitable to lodge the etb, so that the embolus can be pushed through the copulatory opening (co). Behind it the inner (lower) bend of the bird-neck-curve can be seen, providing a rounded excavation, suitable to anchor the tegulum tip.

In C.lauta the hypothetical functioning during copulation is also visualized in ventral view (Fig. 5). The inner excavation is obscured by the bird neck curve which is inclined ventrally. A large atrium is seen between the outer and the inner atrium rim leading to the copulatory opening. By contrast with P.scandens, in C.lauta the total length of the tegulum exceeds the distance between the posterior pocket and the atrial cavity. However, the proximal part of the tegulum in C.lauta is considerably swollen ventrally (Fig. 1b, d); an attempt to visualize the possible mating positions is made in Fig. 5, where the tegular bulge (tbu) is anchored against the posterior ridge of the epigyneal pocket (pp); the etb (red) is inserted into the atrium, the embolus (ep) inside the copulatory duct, the retrolateral part of the tegulum (yellow) distally resting on the ventral surface of the epigyne; the contours of the palp positioned on the ventral surface of the epigyne is presented as red dotted line. A similar construction in male and female genital organs is found in the genus BristowiaReimoser, 1934 (Szüts 2004).

Materials and methods

A stereomicroscope Zeiss Stemi SV11, ocular 10 x objective zoom 0.8 - 6.6 x, with Muiji halogen microscope lamp and Schott glass fiber optic lighting was used for examination and photography. Drawings were made with Zeiss drawing tube with drawing pens MICRON 1,0, 3,0 5,0 and 7,0 mm, lead pencils H, B and 2B and H, 3B and 8B cretacolor on special drawing paper. Photographs were made with a DS-R:1 digital camera driven by NIS Elements software with composite extended focus images generated using Helicon Focus 7 (Kozub et al. 2000). Additional photographs were made using a Nikon J5 digital camera. Measurements were made by using an ocular micrometer and reported in millimeters. Body lengths exclude protruding eye lenses and spinnerets; leg length measured on the dorsal side. Epigynes were detached for examination and temporarily immerged in clove oil for clearing.

The following abbreviations are used in the text and figures:

a - atrium

AME - anterior median eyes

beb – base of embolar tegular branch

bnc – bird’s neck curve

cc - cymbium cap, distance between distal edge of alveolus and top of cymbium

cd - copulatory duct or insemination duct

CM – Collection Murphy, in MMUE

co - copulatory opening

ep – embolus proper

etb - prolateral embolar tegular branch

fd - fertilisation duct

ibc - inner bend of bird's-neck shaped curve

MMUE – Manchester Museum, University of Manchester, U.K. (Arzuza Buelvas 2018)

mra - median rim of atrium

ora - outer rim of atrium

p – projection of prolateral embolar tegular branch (etb) beyond retrolateral lobe of tegulum (rt), exluding embolus proper (ep)

pt – proximal tegular lobe

pp - posterior pockets

RMNH – Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden, NL, formerly Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie

rt – retrolateral part of tegulum

rta - retrolateral tibial apophysis

s - spermatheca

sdl - sperm duct loop

tbu - tegular bump

Total length is measured exclusive of AME lenses and spinnerets. Leg measurements are presented thus: total (femur – patella – tibia – metatarsus – tarsus). All measurements in milimetres.

Hairs are thin filiform, erect or appressed; setae are elongate acuminate, flattened, sometimes appressed and iridescent; scales are round, thin and iridescent.

Use of identifiers

Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs) are globally unique, resolvable and persistent unique identifiers that are in widespread use for citing publications. In the realm of biodiversity informatics, they have been adopted to identify and electronically link multiple classes of data objects within taxonomic publications. Journal publishers like Pensoft as well as the biodiversity data group Plazi have developed workflows for biodiversity publications which issue DOIs for elements within the publication, such as figures, taxonomic treatments, and supplementary data (Penev et al. 2009, Fawcett et al. 2022, Miller et al. 2015). Taxonomic treatments are the content within a taxonomic publication concerned with one particular taxon, such as a species description including its diagnosis, figures, specimens, and other data (Agosti and Egloff 2009, Miller et al. 2015). The paper you are reading now contains 10 treatments, two generic treatments and 8 species treatments. The EU research project BiCIKL is an European Union Horizon 2020 biodiversity informatics infrastructure project that is innovating in the area of data mobilisation by means of persistent unique identifiers (Penev et al. 2022).

In this contribution to spider taxonomy, we demonstrate an innovation in the mobilisation of biodiversity data. All specimen records cited herein have been assigned a digital object identifier (DOI; Table 1) that points to a digital representation of the specimen, a digital specimen, which can become a digital extended specimen by digitally linking it to relevant ecological, environmental, and related data from numerous domains (Hardisty et al. 2022). This contribution from the BiCIKL project proposes an electronic extension of a physical object archived in a natural history collection and digitized through its institutional collections database (Addink et al. 2023).

Table 1.

Digital specimen DOIs and institutional identifiers for the specimens cited. Recognied species are hyperlinked to their Catalog of Life (https://www.catalogueoflife.org/) record; our new species and the revalidated species P.minuta are linked to Zoobank (https://zoobank.org/) records created for them. Institutional identifiers are catalog numbers in the case of the University of Manchester collection (MMUE), and machine readable persistent identifiers (PIDs) in the case of the Naturalis collection (RMNH).

The digital specimen is a mutable and versioned FAIR Digital Object (FDO) that is machine actionable through inclusion of a data type definition, a machine readable description of its data structure and allowed operations which is included in the metadata of the DOI record. Machine actionablilty allows systems to act upon the data by for example adding annotations with new information. Digital Specimen DOIs include, in contrast with most other DOIs, more metadata in the DOI record than only the URL to which it should redirect. This can be seen by specifying the noredirect parameter with the DOI, a feature of the Handle system on which DOIs are build, for example: https://doi.org/10.3535/1CE-SXA-2BC?noredirect. This allows the retrieval of some metadata describing the object without having to retrieve the full data object. It allows machines to quickly navigate billions of objects but can also be used in applications to provide a user with extra information about the object referenced by a DOI before going to its HTML landingpage, like the type of specimen, its name or its catalog number. Also, these DOIs implement multiple redirects (another feature of the Handle system): one for machines pointing to a JSON version of the data and one for humans pointing to a HTML landingpage. This can be further extended with for example a redirect directly to the bit-sequence of the object, which is useful for specimen images. In other words: a machine can decide to either retrieve the full digital media object including metadata and annotations, or directly retrieve the binary image file. The first digital specimen DOIs in existence have been created for this publication through DataCite by making use of FDO infrastructure developed by DiSSCo.

Another innovation we demonstrate in this publication is the use of nanopublications, which are supported by the Pensoft Arpha journal system. A nanopublication is a scientifically meaningful assertion about something, that can be uniquely identified and attributed to its author, its original source (provenance) and citation record (publication info). A nanopublication can directly link a scientific paper to the specimens it discusses together with provenance information, like: "This digital specimen DOI is discussed in this article DOI, published on [date] by [author]". This makes it very easy to digitally track which specimens are cited in which publication and by whom.

In addition, all human agents associated with these specimens (for example, collectors) have been linked through a machine readable persistent unique identifier (Table 2). Where possible, we found existing identifiers such as ORCiD or Wikidata. Where no such pre-existing identifier could be found, we created records in Wikidata.

Table 2.

Wikidata identifiers for collectors and other human agents cited in the specimen data.

| Name string | Full Name | Wikidata QID |

| F. Murphy | Frances Murphy | Q22111840 |

| J. A. Murphy | John A. Murphy | Q22113060 |

| P. R. Deeleman | Paul Robert Deeleman | Q60057036 |

| C. L. Deeleman | Christa Deeleman-Reinhold | Q2964921 |

| A. Floren | Andreas Floren | Q23068668 |

| P. Schwendinger | Peter Schwendinger | Q7174897 |

| W. Corley | Wendy Corley | Q125189589 |

| S. Djojosudharmo | Suharto Djojosudharmo | Q125189757 |

Taken together, the use of machine readable persistent unique identifiers, constructed according to FAIR principles to facilitate the widest possible exchange of data, facilitate the linking of biodiversity data elements that are both logical and flexible. Biodiversity data are a challenge for several reasons, but they include both magnitude (occurrence records for all species across space and time), and the multiple forms of physical objects and electronic data that contribute to this sphere of knowledge. In an era of biodiversity crisis, the importance of an effective infrastructure to facilitate the storage and recall of these data and linked objects is coming into clear focus.

Taxon treatments

Chrysilla

Thorell, 1887

0D9462C8-DAB5-5752-BA64-36EA50D1D855

https://www.checklistbank.org/dataset/288943/taxon/62LN8

World Spider Catalog: urn:lsid:nmbe.ch:spidergen:02890

Chrysilla Thorell, 1887 - Thorell 1887

Chrysilla lauta Thorell, 1887Thorell 1887: 378.

Description

Middle-sized (body length 3.2–7.2 mm) unidentate, sexually dimorphic spiders. Carapace profile sloping down directly behind the eyes in a straight line. Chelicerae in males simple, elongated and sometimes divergent, in females parallel. In males, leg I dark and longer than the others, other legs pale, in females all legs pale and leg I proportional; both sexes with some black rings on leg IV. Spination of legs: femur I-IV with 1-1-1d, tibia I and II with 2-2-2 v or 2–2-2-1 v, metatarsus I and II with 2-2 v in both sexes; in C.lauta ventral spines on tibia I and II very strong, in other Chrysilla species front legs usually not so strongly armed. Abdomen in males about 1½ – 2 times longer than carapace, in female shorter and more rounded. The dorsal pattern is variable between species.

Diagnosis

Chrysilla can be distinguished from other chrysillines by the following set of characters: 1) – body colour: live specimens are conspicuously coloured in patterns of white, black, red, iridescent blue or green; in specimens kept in alcohol, the red colour rapidly disappears. Similar colours are also found in SilerSimon, 1889; 2) – clypeus: Chrysilla lauta Thorell, 1887, C.volupe (Karsch, 1879), C.deelemani Prószyński & Deeleman-Reinhold, 2010, and Proszynskia Kanesharatnam & Benjamin, 2019 lack a bunch of long white setae and have only dark metallic scales on the clypeus (in life), whereas a white bunch on the clypeus is characteristic for Phintelloides. However, the description of Chrysillaacerosa Wang & Zhang, 2012 is provided with numerous colour photos, one of which clearly shows bundles of white flattened setae in front of the AME; 3) – thorax margins: in Chrysilla and Siler semiglaucus, both sexes have the thorax sides lined by a narrow strip of iridescent scales (Kanesharatnam and Benjamin 2019, fig. 21A; Yamasaki et al. 2018, fig. 11), whereas Phintelloides and Phintella have a wide band of white flattened setae along the margin of the thorax in both sexes; 4) – abdomen: in all known Chrysilla species, males have a long, cylindrical abdomen, about three times longer than wide and clearly narrower than the carapace, sometimes with a dorsal scutum covered with colourful iridescent scales. In the field, the species can be recognized by their colour pattern. In females, the abdomen is notably shorter. By contrast, the male abdomen in Phintella and Phintelloides is shorter and more rounded, occasionally with something like a scutum; 5) – cymbium length: in Chrysillaand Phintelloidesthe slender palp has a long cymbium cap (cc) with parallel sides, measuring more than half the bulbus length. This contrasts with Phintella, which has a cc of less than half the bulbus length, and Siler, which has a short cc that protrudes only barely beyond the tip of the embolus; 6) – embolus: in Chrysilla the embolus proper (ep) is thin and filiform as in Phintelloides; in Phintella and Proszynskia the ep is short and sclerotized, rigid and conical or acuminate, never filiform; in Siler the embolus is conical; 7) – embolar tegular branch (etb) is present in males of Chrysilla and in Phintelloidesscandens and most probably also in the Phintelloides species from India and Sri Lanka; it is long, slender and flexible; the tegulum is like a fingerless glove with movable thumb; in Phintella, Proszynskia and Siler, the etb is absent, the embolus-bearing part not separate, the tegulum is rigid like a trowel 8) – tegular lobe (pl) and tegular bump: in Chrysilla and Phintelloides the lobe is broad and rounded (Fig. 1), or shallow as in P.scandens (Fig. 14a, b, c, d, e); in Phintella and Silerit is triangular/funnel-shaped; in Proszynkia it is expanded and broadly rounded; all species have a bump on the tegulum, traditionally present in all chrysillines, usually in the middle or in the proximal half of the tegulum; 9) – palpal colour: in Chrysilla, palp segments are contrasting, with different segments exhibiting different combinations of dark and white. The dark segments look iridescent blue or black in photos of live specimens; this seems to be a reliable character for species identification. In Phintella and Phintelloides, palps are uniformly coloured, or all pale with dark cymbium; in Silersemiglaucus specimens, the femur, patella and tibia have various shades of buff or grey (in life probably blue or green), the cymbium is pure white as in Chrysilla; 10) – epigynal structure: Chrysilla and Phintelloides have a similar structure, deviating from all related genera: the lateral copulatory opening is vaguely defined (except in C.deelemani), the entrance section to the copulatory ducts is a large atrium, usually funnel-shaped like an opened birds beak, leading through a conspicuous, U-turn section with swollen parietal walls (bnc) (not swollen in C.deelemani and C.scandens) in transition to the vertical section of the copulatory ducts (cd) which are tubular and rigid. In Phintella, the copulatory opening is normally marked with a rigid ring, usually but not always positioned anteriorly (Kanesharatnam and Benjamin 2019: figs 33F, 36C). In Chrysilla, the middle, U-shaped section is often described as a birds’ neck (bnc), with a beak (atrium); spermathecae are situated near the posterior edge of the epigyne, they are round or reniform as in Phintella and relatively small; in Phintella the ducts are straight or curved and of various lengths; in Siler the copulatory opening is hidden in an anterior hood, the copulatory ducts are very short. The posterior epigynal margin is chitinized and provided with a pair of shallow pockets in most chrysilline genera.

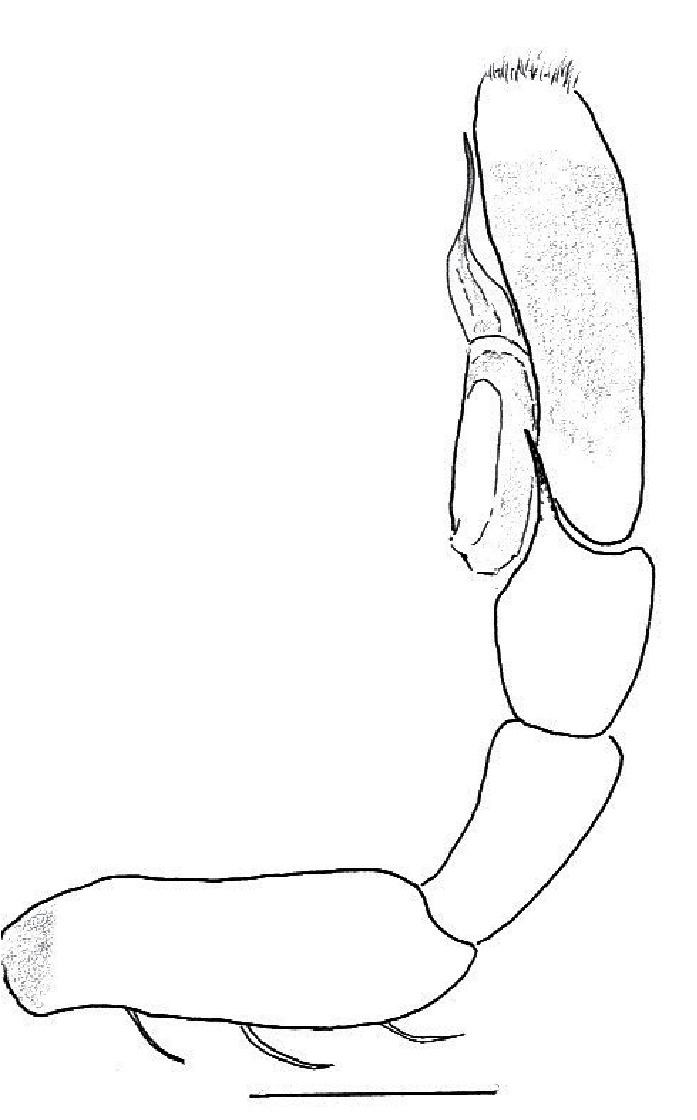

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., photographs and illustrations of male pedipalp and prosoma

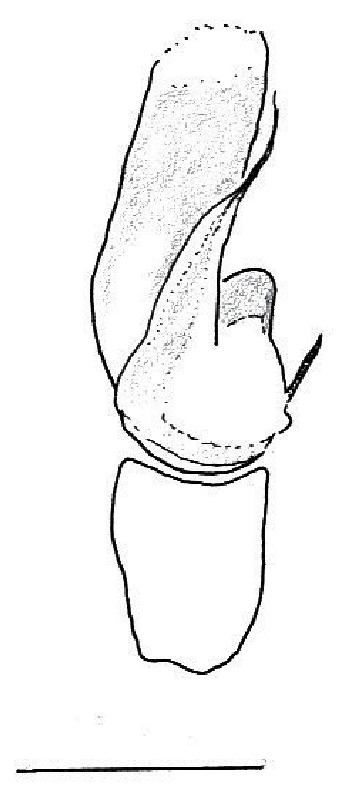

Figure 14a.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., male holotype, pedipalp, ventral view, RMNH.ARA.18251, scale bar 0.2 mm

Figure 14b.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., male holotype, pedipalp, retrolateral view, RMNH.ARA.18251, scale bar 0.2 mm

Figure 14c.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., male pedipalp, ventral view, illustration, scale bar 0.2 mm

Figure 14d.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., male pedipalp, retrolateral view, illustration, scale bar 0.2 mm

Figure 14e.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., male pedipalp, prolateral view, illustration, scale bar 0.2 mm

Figure 14f.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., male holotype, prosoma, dorsal view, RMNH.ARA.18251, scale bar 1 mm

Distribution

Seven Chrysilla species have been recorded from South and Southeast Asia with specimen records from the following countries: Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, Indonesia and southwest China. In addition, two species are recorded from tropical Africa, and one from Australia.

Taxon discussion

Chrysilla species are sexually dimorphic, and preserved specimens appear substantially different compared to living animals. This led to much confusion about the identity of the genus. It was more than a century after the first description of Chrysilla that males and females were associated (Caleb et al. 2018, Wang and Zhang 2012). Live animals of the different sexes exhibit different patterns and colours in both carapace and abdomen (Fig. 2; Caleb et al. 2018, Koh et al. 2022, Wang and Zhang 2012). Ten species are currently catalogued (World Spider Catalog 2024); with the description herein of the previously unknown female of C.deelemani Prószyński & Deeleman-Reinhold, 2010, five Chrysilla species are known from only one sex. Chrysilla doriae Thorell, 1890 (male, Sumatra), has a palp which is typical for Phintella species and the species probably is a synonym (CDR personal observation of holotype). The holotype of Chrysilla delicata Thorell 1892 (female, Sumatra; not Myanmar, contra World Spider Catalog 2024) was very recognisably illustrated (Prószyński 1984: 69), together with the palp of a syntopic male "Iciusglaucochira Thorell, 1890." Later, the male Phintellaconradi Prószyński and Deeleman-Reinhold 2012 was described from another (but likely conspecific) male specimen from Sumatra. Recently, Kanesharatnam and Benjamin (2019) established Chrysillajesudasi Caleb & Mathai, 2014 as the type species of the new genus Phintelloides.

Chrysillain many ways resembles and has been repeatedly confused with Phintella Strand, 1906 (Żabka 1985). A series of phylogenetic analyses of chrysilline salticids found Phintella and Phintelloides to be closely related, possibly in a clade with Proszynskia and Icius; Chrysilla is somewhat distantly related from these genera, and more closely related to Siler (Kanesharatnam and Benjamin 2019). Conflict within the Kanesharatnam and Benjamin (2019) study derives from analytical permutations of morphological and DNA sequence data under parsimony and likelihood optimality criteria. The absence of conspicuous bright colours makes species of Phintelloides look superficially like Phintella species. Nevertheless, the morphological and functional copulatory characters are substantially similar in Chrysilla and Phintelloides, and distinct from those in genera such as Phintellaand Proszynskia.

Our diagnosis can be expressed in simple words: genus Chrysilla and Phintelloides share their reproductive engine (copulatory organs) but are enveloped in a different coat; black, white and yellow setae in Phintelloides, red body colour in life and iridescent scales with black and white in Chrysilla. Involving more chrysilline genera: the “Chrysilla coat” is more widespread and also is characteristic for other chrysilline genera, such as Siler, Cosmophasis and Orsima, whereas the specialised “Chrysilla engine” is shared between Chrysilla and Phintelloides, but remarkably is also present in the genus Bristowia, a genus Maddison (2015) provisionally placed in the Hasariini.

Chrysilla lauta

Thorell, 1887

8F06576C-F835-5EA0-BC67-BE0E95FBD9C6

https://www.checklistbank.org/dataset/288943/taxon/5YKJJ

World Spider Catalog: urn:lsid:nmbe.ch:spidersp:032753

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887 - Thorell 1887: 378 (spider catalogue of Roewer 1955 erroneously cites p. 387) (m), type locality: Bhamo, Myanmar; Prószyński 1976: 154, fig. 237 (m); Prószyński 1983a: 44, figs 4-6 (m); Żabka 1985: 210, figs 81-82 (m) Vietnam (synonymy with Cosmophasislongiventris); Koh 1989: 103 (m, photo) Singapore; Song and Chai 1991: 14, fig. 2 (m) Hainan; Song et al. 1999: 507, fig. 290N-O (m) Hainan, Myanmar, Vietnam; Prószyński and Deeleman-Reinhold 2010: figs 36-37 (m); Koh and Ming 2013: 180 (m, photo); Prószyński 2018: fig. 5G (m); Yamasaki et al. 2018: 27, figs 2-24 (mf) Taiwan; Kanesharatnam and Benjamin 2019: 46, figs. 19A-E, 20A, B (mf) Sri Lanka; Koh and Bay 2019: 216 (m, photo); Peng 2020: 75 fig. 35a-b (m); Koh et al. 2022: 347 (mf) Singapore.

Cosmophasislongiventris Simon, 1903 - Simon 1903a: 732 (m) Sri Lanka (Ceylon), Philippines.

Materials

Type status: Other material. Occurrence: catalogNumber: MMUE G7572.5441; occurrenceRemarks: labeled “blue and red”; recordedBy: F. & J. A. Murphy; individualCount: 1; sex: male; lifeStage: adult; otherCatalogNumbers: https://doi.org/10.3535/G0G-G7D-N5J; occurrenceID: 52F7782C-1297-59F2-95B3-032DD4842E7A; Taxon: scientificName: Chrysillalauta; Location: country: Singapore; locality: Kent Ridge; verbatimCoordinates: 1°17’N 103°47’E; decimalLatitude: 1.2833333333333; decimalLongitude: 103.78333333333; Event: eventDate: 1986-07-06; habitat: garden; Record Level: institutionID: https://ror.org/027m9bs27; institutionCode: MMUE; basisOfRecord: PreservedSpecimen

Type status: Other material. Occurrence: catalogNumber: MMUE G7572.6430; recordNumber: DSC 6285-6591; recordedBy: F. & J. A. Murphy; individualCount: 1; sex: male; lifeStage: adult; otherCatalogNumbers: https://doi.org/10.3535/PER-LNE-HEW; occurrenceID: EA93CB0B-5889-5F48-A7F4-8DF6D466C5A9; Taxon: scientificName: Chrysillalauta; Location: country: Singapore; locality: Pulau Ubin; verbatimCoordinates: 1°25’N 103°57’E; decimalLatitude: 1.4166666666667; decimalLongitude: 103.95; Event: eventDate: 1991-01-27; habitat: roadside; Record Level: institutionID: https://ror.org/027m9bs27; institutionCode: MMUE; basisOfRecord: PreservedSpecimen

Type status: Other material. Occurrence: catalogNumber: MMUE G7572.6440; recordNumber: DSC 3727-36; recordedBy: F. & J. A. Murphy; individualCount: 1; sex: male; lifeStage: adult; otherCatalogNumbers: https://doi.org/10.3535/HS2-8W8-F23; occurrenceID: 5C4F929A-3E03-5EE2-8D8A-513EBF473EA3; Taxon: scientificName: Chrysillalauta; Location: country: Malaysia; stateProvince: Selangor; locality: Banting; verbatimElevation: 100 m; verbatimCoordinates: 2°48’04”N 101°30’46”E; decimalLatitude: 2.8011111111111; decimalLongitude: 101.51277777778; Event: eventDate: 1982-12-17; Record Level: institutionID: https://ror.org/027m9bs27; institutionCode: MMUE; basisOfRecord: PreservedSpecimen

Type status: Other material. Occurrence: recordNumber: CM 19182; recordedBy: F. & J. A. Murphy; individualCount: 1; sex: female; lifeStage: adult; otherCatalogNumbers: https://doi.org/10.3535/SGZ-EFZ-VRK; occurrenceID: 8DF23168-B93F-546A-AE23-EF2321DE0C54; Taxon: scientificName: Chrysillalauta; Location: country: Malaysia; stateProvince: Pahang; locality: Genting; verbatimCoordinates: 3°24’N 101°46’E; decimalLatitude: 3.4; decimalLongitude: 101.76666666667; Event: eventDate: 1990-12-08; Record Level: institutionID: https://ror.org/027m9bs27; institutionCode: MMUE; basisOfRecord: PreservedSpecimen

Description

Male. Total length from Singapore 7.1 mm and 4.2 mm, from Banting 4.3 mm. For differences with C.volupe, see under that species. Colouring of carapace, abdomen and palps see chapter “coloration in various chrysilline species”. Carapace with all red areas in live specimens bare and lacking setae and scales, remains of small iridescent particles visible on the anterior transverse bars. Chelicerae slanting, divergent in the large male, parallel in both smaller males (Fig. 3b). Legs I longest, dark with white contrasting band apically on tibia, other legs pale, femur I dorsally with some long thin white setae in alcohol, violet in life, leg IV with some dark rings. Abdomen long, thin and shiny and gradually tapering. In all 3 available males, dorsum black and shiny, central band with round iridescent scales uninterrupted all through, at 2/3 of the length with a bell-shaped area with small round white iridescent scales; sides with a pair of narrow strips bearing small round green reflecting scales; venter pale brown, a median pale band bordered by a pair of dark bands. Coxae dorsally with white flattened setae. Palps (Fig. 1), tibia and cymbium pale, strongly contrasting with dark femur and patella (blue in life). Proximal part of tegulum with ventral bulge (Fig. 1a: tb) and a tegular bump (Fig. 1a: tbu) as in C.volupe. Embolar tegular branch (Fig. 1a: etb) narrow and elongate, flexible, proximally articulating at basal, hidden part of tegulum (cf. Fig. 1c: beb), partly running alongside tegulum and projecting distally beyond retrolateral part of tegulum containing the sperm duct loop over distance p (Fig. 1a: p); embolus filiform, slightly flexed at base, length same as p.

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887, photographs of male and female preserved specimens

Figure 3a.

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887, male habitus, dorsal view, CM 15726, scale bar 2 mm

Figure 3b.

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887, male prosoma, ventral view, CM 15726

Figure 3c.

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887, female habitus, dorsal view, CM19182

Figure 3d.

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887, female habitus, ventral view, CM19182

Measurements (Singapore: Kent Ridge). Body length 7.10. Carapace 2.70 long, 1.80 wide, 1.15 high. Abdomen 4.30 long, 1.20 wide. Leg I 7.70 (2.50 [0.70 wide] – 1.10 – 1.90 – 1.50 – 0.70), leg II 5.20 (1.60 [0.45 wide] – 0.80 – 1.20 – 1.00 – 0.60) leg III 5.00 (1.50 – 0.70 – 1.00 – 1.30 – 0.50) leg IV 6.60 (1.80– 0.70 – 1.60 – 1.70 – 0.80). Palp 0.9 – 0.5 – 0.5 – 0.7 width cymbium 0.3.

Female (Genting). Colour photos of live females (Yamasaki et al. 2018: fig. 16, Koh et al. 2022: 347) show parts of carapace covered with white setae and abdomen with pattern of red, white, black and iridescent greenish spots with considerable variation between specimens. In the only female specimen available to us (Fig. 3c), iridescent scales as seen on carapace of males are lacking and green colour is lost. Chelicerae with parallel sides, promargin with one distal tooth, retromargin with two distal teeth. Legs all pale. Abdomen with few iridescent scales suggesting a vague dorsal pattern, lateral patch consisting of reddish procumbent hair, posteriorly a pattern of dark areas covered with simple black setae as in males, these are visible in several reversed V- arranged bars on posterior half of abdomen; venter as in males. Epigyne similar to that in Phintelloidesjesudasi, except spermathecae not touching and halfway twist in copulatory ducts as in P.jesudasi, absent in C.lauta.

Measurements. Body length 5.0. Carapace 1.90 long, 1.30 wide, 0.95 high. Abdomen 3.00 long, 2.00 wide, 0.80 high. Measurements of legs: I 4.05 [1.40 (0.40 wide]– 0.60 – 1,00 - 0.65 – 0.40) leg II 3.00 (1.00 [0.30 wide]– 0.50 – 0.70 – 0.50 -0.30), leg III 3.30 (0.90 – 0.50 – 0.70 – 0.50 – 0.70) leg IV 4.20 (1.20 – 0.50 – 1.00 – 0.90– 0.60).

Distribution

The species has been cited from Myanmar, Vietnam, Singapore, Thailand, Borneo, Taiwan, China and Sri Lanka (Fig. 6). The type locality Bhamo, Myanmar is situated close to the western border of southern Yunnan in a large mountain massive/complex across the Burmese - Chinese border, about 60 km from the Xishuangbanna tropical Botanical garden. This area has been extensively explored for spiders in the first decade of the 21th century in primary and various kinds of disturbed forest. Unfortunately, no Chrysilla species have been reported from that project.

Figure 6.

Map showing occurrence records for selected species. Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887: blue circle for previously published records, red circle for new records; Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov.: black circles.

Ecology

In forests and gardens, usually by beating/sweeping shrub and trees, from lowland up to 600 m.

Notes

The contrasting colouring of the male palps: dark femur and patella, pale tibia and cymbium was already mentioned by Thorell, 1887 in the description of the type specimen from Bhamo in northeastern Myanmar. It is consistently present in the material studied for the present paper.

Chrysilla volupe

(Karsch, 1879)

1AFC737F-365F-59AD-82A9-C4BE43F6FDA2

https://www.checklistbank.org/dataset/288943/taxon/5YKJD

World Spider Catalog: urn:lsid:nmbe.ch:spidersp:035559

Attusvolupe Karsch, 1879 - Karsch 1879: 552 (m) Sri Lanka (Ceylon).

Chrysillasp. - Prószyński 1984: 19 (m) Bhutan (according to Żabka 1988: 465).

Silersemiglaucus (Simon, 1901) - Prószyński 1985: 73, figs 16-17 (f, misidentified according to Caleb et al. 2018: 144) Sri Lanka (Ceylon).

Phintellavolupe (Karsch, 1879) - Żabka 1988: 465, figs 122-125 (m); Caleb and Mathai 2014: 64, figs 15-23 (m) India.

Chrysillavolupe (Karsch, 1879) - Caleb 2016: 271, India; Thumar and Dholakia 2018: 2, figs 1-6 (m) India; Caleb et al. 2018: 144, figs 1-25 (mf) India; Kanesharatnam and Benjamin 2019: 49, figs 20C-F, 21A-E, 22A-D (mf) Sri Lanka; Magar et al. 2020: 4, figs 4-6 (mf) Nepal.

Materials

Type status: Other material. Occurrence: catalogNumber: MMUE 7572.6434; recordNumber: CM 15916; recordedBy: F. & J. A. Murphy; individualCount: 1; sex: male; lifeStage: adult; otherCatalogNumbers: https://doi.org/10.3535/67X-9R9-YCM; occurrenceID: 01C98BCA-9D5C-5E2A-B63A-6417E1E0562B; Taxon: scientificName: Chrysillavolupe; Location: country: Sri Lanka; locality: Peradeniya, Leersia; verbatimElevation: 500 m; verbatimCoordinates: 7°16’01”N 80°35'44”E; decimalLatitude: 7.2669444444444; decimalLongitude: 80.595555555556; Event: eventDate: 1986-11-25; Record Level: institutionID: https://ror.org/027m9bs27; institutionCode: MMUE; basisOfRecord: PreservedSpecimen

Type status: Other material. Occurrence: catalogNumber: RMNH.ARA.18249; recordedBy: P. R. & C. L. Deeleman; individualCount: 1; sex: male; lifeStage: adult; otherCatalogNumbers: https://doi.org/10.3535/6H9-R1R-330; occurrenceID: 1F561749-E7FA-5747-AA7A-FF9401CC24C8; Taxon: scientificName: Chrysillavolupe; Location: country: Sri Lanka; locality: Kataragama Peak (Tissamaharama); verbatimCoordinates: 6°23’35”N 81°20’17”E; decimalLatitude: 26.393055555556; decimalLongitude: 81.338055555556; Event: eventDate: 1981-08-18; habitat: dry bush litter; Record Level: institutionID: https://ror.org/0566bfb96; institutionCode: RMNH; basisOfRecord: PreservedSpecimen

Type status: Other material. Occurrence: catalogNumber: RMNH.ARA.18259; recordedBy: P. R. & C. L. Deeleman; individualCount: 1; sex: female; lifeStage: adult; otherCatalogNumbers: https://doi.org/10.3535/WL8-0R1-42B; occurrenceID: C37E9FA4-7FA4-59B4-BF7A-7F5A705DC44B; Taxon: scientificName: Chrysillavolupe; Location: country: Sri Lanka; locality: Kataragama Peak (Tissamaharama); verbatimCoordinates: 6°23’35”N 81°20’17”E; decimalLatitude: 26.393055555556; decimalLongitude: 81.338055555556; Event: eventDate: 1981-08-18; habitat: dry bush litter; Record Level: institutionID: https://ror.org/0566bfb96; institutionCode: RMNH; basisOfRecord: PreservedSpecimen

Description

Additions to the description of the male (Leersia). Abdomen in alcohol with middle band slightly paler than lateral areas, as in lauta ornamented with some gold reflecting scales and anteriorly areas with black setae; venter as in lauta. All legs dark, tarsi mostly light. Male palp (Fig. 7): femur, patella and tibia and basal half of cymbium brown (blue in life), distal half of cymbium white. Measurements. Body length 3.40 (smaller then described specimens from India), carapace length 1.40, width 1.00, height 0.60. Abdomen length 2.00 width 0.55. Palp femur 0.60, patella 0.20, tibia 0.15, cymbium length 0,60, width 0.20. Chelicerae not diverging. Leg I 3.70 (1.10 [width 0.35] – 0.40 – 0.80 - 1.10 – 0.30), legs II lost, leg III 2.60 (0.70 – 0.40 - 0.50 – 0.60 – 0.40), leg IV 3.30 (1.00 - 0.30 – 0.70 – 0.90 – 0.40).

Chrysillavolupe (Karsch, 1879), photographs of right male pedipalp reversed so as to appear as a left pedipalp to facilitate comparison

Figure 7a.

Chrysillavolupe (Karsch, 1879), reversed right male pedipalp, ventral view, CM 15916

Figure 7b.

Chrysillavolupe (Karsch, 1879), reversed right male pedipalp, retrolateral view, CM 15916

Female (Tissamaharama). No abdominal pattern distinguishable in preserved specimen (Fig. 8c; Kanesharatnam and Benjamin 2019: fig 22A). Live animals with mottled black, red, and iridescent blue (Kanesharatnam and Benjamin 2019: fig 22A; Caleb et al. 2018: figs 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12). Copulatory ducts longer than in C.lauta, length 1½ x diameter of spermatheca, in anterior half running adjacent and parallel to each other (Kanesharatnam and Benjamin 2019: fig. 20E, F); in C.lauta ducts length not much more than 1 diameter of spermathecae and curved over whole length (Fig. 4b, c, d).

Chrysillavolupe (Karsch, 1879) and Chrysilladeelemani Prószyński & Deeleman-Reinhold, 2010, photographs of male and female preserved specimens

Figure 8a.

Chrysillavolupe (Karsch, 1879), male habitus, dorsal view, CM 15916

Figure 8b.

Chrysillavolupe (Karsch, 1879), male habitus, ventral view, CM 15916

Figure 8c.

Chrysillavolupe (Karsch, 1879), female habitus, dorsal view, RMNH.ARA.18259, scale bar 1 mm

Figure 8d.

Chrysilladeelemani Prószyński & Deeleman-Reinhold, 2010, female habitus, dorsal view, RMNH.ARA.18265

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887, photographs and illustrations of preserved specimens and female reproductive structures

Figure 4a.

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887, male prosoma, anterior view, CM 15726

Figure 4b.

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887, female vulva, dorsal view, CM19182, scale bar 0.1 mm

Figure 4c.

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887, female epigynum, ventral view, illustration, scale bar 0.2 mm

Figure 4d.

Chrysillalauta Thorell, 1887, female epigynum, dorsal view, illustration, scale bar 0.2 mm

Diagnosis

This species is similar to C. lauta. The carapace as in C. lauta, the dorsal abdomen pattern is distinctive, in life with an anterior iridescent green band followed by a wide M-shaped band in red, behind which another red band with green in between, distally an iridescent black/violet tail (Fig. 2, Caleb et al. 2018: figs 1-12); this pattern may be preserved or lost in alcohol. Male palp with several features that can be used for identification. In C.volupe (Fig. 7), the palpal tibia and basal part of cymbium are darkish, (blue in life), white in C.lauta; the dorsal margin of rta is more slender and smoothly curved, in C.lauta it is somewhat wider and dorsally slightly undulating. This latter key character agrees with drawings of a palp of the type specimen of C.volupe from Sri Lanka by Żabka 1988 (figs 122, 124), but not when comparing with Prószyński's palp drawing of “Chrysilla” sp. from Bhutan (Prószyński 1984: 19), which was interpreted as this species by Żabka 1988: 466). In female C. lauta all legs are uniform pale, in female C.volupe legs are pale with a few black rings on leg IV.

Distribution

Sri Lanka, India, Bhutan, Nepal. Caleb and Mathai 2014 (p. 64) erroneously cite Burma among the distribution records (Caleb et al. 2018). In addition, the online biodiversity monitoring community iNaturalist.org has research grade records from Bangladesh and Myanmar.

Ecology

Foliage and dry leaf litter.

Biology

Male C.volupe spiders have been seen moving their palps up and down continuously and waving their long thin abdomen in circles up in the air, exhibiting large white light-reflecting spots.

Chrysilla deelemani

Prószyński & Deeleman-Reinhold, 2010

BC93DFED-4D0D-5AD6-B773-973AB0FE44A9

https://www.checklistbank.org/dataset/288943/taxon/5YKK7

World Spider Catalog: urn:lsid:nmbe.ch:spidersp:043594

Chrysilladeelemani Prószyński & Deeleman-Reinhold 2010 - Prószyński and Deeleman-Reinhold 2010: 159, figs 30-35 (m) Indonesia.

Materials

Type status: Holotype. Occurrence: catalogNumber: RMNH.ARA.18264; recordedBy: S. Djojosudharmo; individualCount: 1; sex: male; lifeStage: adult; otherCatalogNumbers: https://doi.org/10.3535/VYQ-YW1-AGE; occurrenceID: F26693C8-F659-5D7C-BDCB-A4CBDDEB6EEB; Taxon: scientificName: Chrysilladeelemani; Location: island: Lesser Sunda Islands; country: Indonesia; locality: Lombok Island, Kuta; verbatimCoordinates: 8°52’S 116°17’E; decimalLatitude: -7.1333333333333; decimalLongitude: 116.28333333333; Event: eventDate: 1990-01-08/09; habitat: secondary forest, from foliage; Record Level: institutionID: https://ror.org/0566bfb96; institutionCode: RMNH; basisOfRecord: PreservedSpecimen

Type status: Other material. Occurrence: catalogNumber: RMNH.ARA.18265; recordedBy: S. Djojosudharmo; individualCount: 3; sex: female; lifeStage: adult; otherCatalogNumbers: https://doi.org/10.3535/Z2J-WMP-FDH; occurrenceID: FA85005B-DC87-537F-A347-F1C0ADB2F377; Taxon: scientificName: Chrysilladeelemani; Location: island: Lesser Sunda Islands; country: Indonesia; locality: Lombok Island, Kuta; verbatimCoordinates: 8°52’S 116°17’E; decimalLatitude: -7.1333333333333; decimalLongitude: 116.28333333333; Event: eventDate: 1990-01-08/09; habitat: secondary forest, from foliage; Record Level: institutionID: https://ror.org/0566bfb96; institutionCode: RMNH; basisOfRecord: PreservedSpecimen

Description

Male. No photo exists of a live specimen. The ornamentation of the abdomen with bands and stripes of coloured scales in alcohol is basically similar as in the other Chrysilla. The species can be diagnosed by the long thin abdomen with dark dorsum with thin pale undulating strip in the middle, somewhat similar as in lauta and also present in females (Fig. 8d; Prószyński and Deeleman-Reinhold 2010: fig. 31), and the broad distally rounded tegulum. Carapace all brown, whole ocular area and rear part of thorax with small round bluish iridescent scales in both male and females, across anterior eye row and around AME a transverse band of white flattened setae and a patch of similar setae behind AME; white moustache below the AME lacking in both male and female, marginal strip on thorax thin, marked with iridescent scales. Chelicerae in male slightly diverging distally. Leg I dark, leg II – III pale, leg IV pale with dark metatarsus. Abdomen thin and elongate, shiny and dark with a brown area on sort of dorsal scutum; central dorsal band and a pair of narrow lateral strips covered with green-violet iridescent scales, as in Chrysillalauta. Venter covered all over with greenish scales. Palp white except dark base of femur, origin of ep from etb obliquely prolateral (Fig. 9a).

Chrysilladeelemani Prószyński & Deeleman-Reinhold, 2010, photographs and illustrations of reproductive structures

Figure 9a.

Chrysilladeelemani Prószyński & Deeleman-Reinhold, 2010, male pedipalp, ventral view, RMNH.ARA.18264, scale bar 0.2 mm

Figure 9b.

Chrysilladeelemani Prószyński & Deeleman-Reinhold, 2010, male pedipalp, retrolateral view, RMNH.ARA.18264, scale bar 0.2 mm

Figure 9c.

Chrysilladeelemani Prószyński & Deeleman-Reinhold, 2010, female epigynum, ventral view, RMNH.ARA.18265, scale bar 0.1 mm

Figure 9d.

Chrysilladeelemani Prószyński & Deeleman-Reinhold, 2010, female vulva, dorsal view, illustration, scale bar 0.2 mm

Female. Total lengths 3.20 - 3.40 mm. Dorsal pattern on carapace (Fig. 8d) with white flattened setae and tiny round green iridescent dots, predominantly on rear slope of thorax. Legs I-IV uniform pale. Abdomen brown with interrupted pale central band and a pair of parallel lateral strips (Fig. 8d) covered with elongate golden iridescent setae, rest of dorsum with dispersed white flattened setae; venter with short white hair. Epigyne (Fig. 9d) with slender copulatory ducts distally curved ventralwards showing copulatory openings; atrium short and wide, crescent-shaped, parallel to the anterior epigyneal margin.

Measurements. Male carapace 1.80 long, 1. 20 wide, abdomen 2.7 long, 0.95 wide. Legs lost. Palp femur 0.85, patella 0.24, tibia 0.26, cymbium 0.70, width cymbium. 0.20. Female, total body length 3.20, carapace 1.30 long, 1.0 wide, 0.6 high. Abdomen 1.5 long, 1.0 wide, epigyne 0.25 wide 0.25 high. Legs: femur I 0.8, femur II 0.7, femur III, 0.7 femur IV 0.9.

Phintelloides

Kanesharatnam & Benjamin, 2019

C4D9ADA9-8DE8-508C-AA23-8AB34BFE5346

https://www.checklistbank.org/dataset/288943/taxon/6NMB

World Spider Catalog: urn:lsid:nmbe.ch:spidergen:04527

Phintelloides Kanesharatnam & Benjamin, 2019 - Kanesharatnam and Benjamin 2019: 20.

Chrysilla jesudasi (Caleb & Mathai, 2014)Kanesharatnam and Benjamin 2019: 20.

Diagnosis

Kanesharatnam and Benjamin 2019 (p. 22) diagnose the genus as follows: male with white tuft of flattened setae on the clypeus; white diamond-shaped mark behind the eye field; prosoma with pale yellow/white transverse band behind AME; abdomen with blackish or brownish grey, longitudinal median band bordered by pale yellow bands (or devoid of markings). In addition, they noted the presence of a comparatively long embolus in males; the apical portion of the bulbus with a lamellar process (although this is absent in some including P.jesudasi, P.brunne, and P.scandens, CLD); and the bird’s-neck-shaped diverging curves at anterior margin of epigynum. Furthermore, Phintelloides have white belt markings on the lateral prosoma, the leg I slightly robust in males, and male pedipalps featuring a small posterior lobe and a long RTA with a bent tip. Females have black patches on the eye field and surrounding PME, behind PLE, and on the posterior slope of the prosoma. In the female genitalia, CO oriented laterally outwards; CD medium-to-very long and bent or twisted; spermatheca pyriform or spherical.

We consider the above diagnosis difficult to interpret from a defining point of view. Several of the listed character states are not compared to that in related genera and some are not valid for all species. Diagnostic somatic characters for the genera involved can be found above in the diagnosis section for the genus Chrysilla, where different states of 10 main cognitive characters between Chrysilla and related genera are summarized. Here we restrict ourselves to adding a few aspects we consider useful. In female Phintelloides species, carapace pattern allegedly is distinctive viz. black and white pattern with 3 pairs of black eye spots (Fig. 10a, c). Indeed this character is found in females of P.jesudasi, P.arborea and P.flavumi but not in P.brunne, P.flavoviri or P.orbisa, or the species described below, P.scandens sp. nov. A similar pattern is also found in females of Phintellapiatensis Barrion and Litsinger 1995, and it possible that this species fits in the genus Phintelloides. In males, the basal part of etb seems to be attached dorsally and is hidden underneath the tegulum; this can only be ascertained by probing the palp manually. Epigyna with a bird’s neck curve (bnc) are, unlike any other salticid genus except Chrysilla, suggestive of a specialised copulatory system.

Phintelloidesjesudasi (Caleb & Mathai, 2014) and Phintelloidesflavumi Kanesharatnam & Benjamin, 2019, photographs of preserved female specimens

Figure 10a.

Phintelloidesjesudasi (Caleb & Mathai, 2014), female habitus, dorsal view, RMNH.ARA.18258, scale bar 1 mm

Figure 10b.

Phintelloidesjesudasi (Caleb & Mathai, 2014), female epigynum, ventral view, RMNH.ARA.18258, scale bar 0.1 mm

Figure 10c.

Phintelloidesflavumi Kanesharatnam & Benjamin, 2019, female habitus, dorsal view, RMNH.ARA.18250, scale bar 1 mm

Figure 10d.

Phintelloidesflavumi Kanesharatnam & Benjamin, 2019, female prosoma, anterior view, RMNH.ARA.18250, scale bar 0.5 mm

A “white moustache” turns up seemingly at random in various chrysilline genera and is inconvenient as a tool when identifying genera. In Phintelloides scandens sp. nov. males it is lacking (Fig. 15a), although females have a tuft of white setae in front of the AME (Fig. 15b).

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., photographs of male and female preserved specimens

Figure 15a.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., male prosoma, anterior view, RMNH.ARA.18255, scale bar 1 mm

Figure 15b.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., female prosoma, anterior view, RMNH.ARA.18257, scale bar 1 mm

Figure 15c.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., male habitus, lateral view, RMNH.ARA.18255, scale bar 2 mm

Figure 15d.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., female habitus, lateral view, RMNH.ARA.18257, scale bar 1 mm

Phintelloidesversicolor and P.munita are morphologically at the edge of the genus because the copulatory organs deviate from all other species by the following characters: the tegulum is undivided and distally bulgy and rigid, the prolateral margin is concave in ventral view; the tegular proximal lobe (pl) is broad and round, the filiform embolus is shorter than that in all known species of Phintelloides and at the base curved over 90°. Females of >versicolor and munita are distinct from other related species by the pair of characteristic black curled marks on white background on the rear part of the carapace (Fig. 17b, e). Furthermore, these females are quite distinct from those of Phintelloides and Phintella by the straight copulatory ducts directed anteriorly and, the absence of the bird’s-neck-shaped curves the absence of the atrium; the opening is connected to a single pair of transverse, horizontal hood-like folds running parallel to the anterior edge of the epigyne.

Phintelloidesversicolor (C. L. Koch, 1846) and Phintelloidesmunita (Bösenberg & Strand, 1906), photographs of preserved male and female specimens

Figure 17a.

Phintelloidesversicolor (C. L. Koch, 1846), male habitus, dorsal view, RMNH.ARA.18261

Figure 17b.

Phintelloidesversicolor (C. L. Koch, 1846), female habitus, dorsal view, CM 19264

Figure 17c.

Phintelloidesversicolor (C. L. Koch, 1846), male face, RMNH.ARA.18261

Figure 17d.

Phintelloidesversicolor (C. L. Koch, 1846), female face, CM 19264

Figure 17e.

Phintelloidesmunita (Bösenberg & Strand, 1906), female habitus, dorsal view, CM 15605

Figure 17f.

Phintelloidesmunita (Bösenberg & Strand, 1906), female face, CM 15605

Phintelloides flavumi

Kanesharatnam & Benjamin, 2019

0144CA91-EFD8-5A96-9CBA-BAA99FC79FA0

https://www.checklistbank.org/dataset/288943/taxon/76YQL

World Spider Catalog: urn:lsid:nmbe.ch:spidersp:051095

Phintelloidesflavumi Kanesharatnam & Benjamin, 2019 - Kanesharatnam and Benjamin 2019: 35, figs 3, 10A-D, 14A-F, 15A-E, 16A-D (mf) Sri Lanka.

Materials

Type status: Other material. Occurrence: catalogNumber: RMNH.ARA.18250; recordedBy: P. R. & C. L. Deeleman; individualCount: 1; sex: female; lifeStage: adult; otherCatalogNumbers: https://doi.org/10.3535/B59-03B-FWV; occurrenceID: 3E2FBFE3-4F1C-54E0-AC09-B662B82EFF44; Taxon: scientificName: Phintelloidesflavumi; Location: country: Sri Lanka; locality: Rathnapura; verbatimCoordinates: 6°42'N 80°23'E; decimalLatitude: 6.7; decimalLongitude: 80.383333333333; Event: eventDate: 1981-08-22/23; habitat: forest below tennis club; Record Level: institutionID: https://ror.org/0566bfb96; institutionCode: RMNH; basisOfRecord: PreservedSpecimen

Description

Additions to the description. Female. The total length of our female is similar to that given for the type specimen, however the legs in our specimen are 50% shorter than the legs measured in the type specimen; the posterior legs are longer than the anterior legs unlike the type material. The underside of the abdomen has small iridescent scales, like scandens. Fig. 11a, c shows the vulva, cleared in clove oil, viewed from ventral and ventrolateral. The bird’s neck-shaped curve tilts in ventral direction. The funnel-shaped openings (Fig. 11c) are the atrium (a), the copulatory opening is at the bottom of the funnel. As in Chrysilla. the atrium is delineated by an upper and a lower projection of the duct wall suggesting an opened birds’ beak. In male P.flavumi, according the description the embolar tegular branch is shorter than the adjacent tegulum; this would agree with the concept that during copulation, the bird’s beak (the atrium) lodges the tip of the etb and swallows the embolus through the copulatory opening whereas the more anteriorly situated cavity on the inner birds’ neck curve (Fig. 11d: ibc) is spatially correctly situated to receive the tegular tip and at the same time fix the base on the posterior pocket (see sketch of P.scandens, Fig. 1c). Measurements. Total length 4.50, Carapace 2.0 long, 1.65 wide, 1.00 high. Abdomen 2.50 long. Legs: I 3.75 (1.15– 0.65 – 0.85 - 0.60 – 0.50), leg II 3.70 (1.15– 0.60 – 0.90 – 0.55 -0.50), leg III 4.30 (1.40 – 0.60 – 0.90 – 1.00 – 0.40), Leg IV 4.30 (1.50 – 0.55 – 0.85 – 0.90 – 0.50), palp 0.70 – 0.60 – 0.30 - 0.35. Epigyne 0.25 wide, 0.30 long.

Phintelloides jesudasi

(Caleb & Mathai, 2014)

6B87D13E-9298-5CD3-9BC3-F93AD1C82780

https://www.checklistbank.org/dataset/288943/taxon/76Z2L

World Spider Catalog: urn:lsid:nmbe.ch:spidersp:047200

Chrysillajesudasi Caleb & Mathai, 2014 - Caleb and Mathai 2014: 63, figs 1-14 (mf) India.

Phintelloidesjesudasi (Caleb & Mathai, 2014) - Kanesharatnam and Benjamin 2019: 41, figs 3, 6E-H, 17A-E, 18A-D (mf) Sri Lanka; Caleb 2020: 15739, figs 17E-G, 29B (mf) India.

Materials

Type status: Other material. Occurrence: catalogNumber: RMNH.ARA.18258; recordedBy: P. R. & C. L. Deeleman; individualCount: 1; sex: female; lifeStage: adult; otherCatalogNumbers: https://doi.org/10.3535/SVV-BR5-KGE; occurrenceID: EB5E12DA-2878-544A-BE8C-3B5C783FD0CE; Taxon: scientificName: Phintelloidesjesudasi; Location: country: Sri Lanka; locality: Tissamaharama, Kataragama Peak; verbatimCoordinates: 6°42'N 80°23'E; decimalLatitude: 6.3930555555556; decimalLongitude: 81.338055555556; Event: eventDate: 1981-08-18; habitat: dry bush litter; Record Level: institutionID: https://ror.org/0566bfb96; institutionCode: RMNH; basisOfRecord: PreservedSpecimen

Taxon discussion

Originally described by Caleb and Mathai (2014) as a species of Chrysilla, Kanesharatnam and Benjamin (2019) established the genus Phintelloidesfor this and a few simliar species with jesudasi as the type species. Phylogenetic analysis based on both morphological and molecular data generally supported the monophyly of this group, with the exception that Phintelloidesversicolor did not always cluster with the rest of the genus (see treatment of Phintelloidesversicolor).

Phintelloides scandens

Deeleman-Reinhold, Addink & Miller sp. nov.

FAE69C8F-621D-5BAC-9506-64383E8F0113

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:34E30429-650A-413C-A6B3-6313C14C5F5B

Materials

Type status: Holotype. Occurrence: catalogNumber: RMNH.ARA.18251; recordedBy: A. Floren; individualCount: 1; sex: male; lifeStage: adult; otherCatalogNumbers: https://doi.org/10.3535/5SG-PLB-MHT; occurrenceID: CE2C0B1A-7A8D-5384-9A1F-59AC87EE29EA; Taxon: scientificName: Phintelloidesscandens; Location: island: Borneo; country: Malaysia; stateProvince: Sabah; locality: Mt. Kinabalu N. P., Sorinsim; verbatimElevation: 500-700 m; verbatimCoordinates: 6°5'N 116°50'E; decimalLatitude: 6.0833333333333; decimalLongitude: 116.83333333333; Event: samplingProtocol: fogging canopy Vitex pinnata (Verbenacae); eventDate: 1997-03-05/14; habitat: 40 year old secondary forest; fieldNotes: (Loc 57); Record Level: institutionID: https://ror.org/0566bfb96; institutionCode: RMNH; basisOfRecord: PreservedSpecimen

Type status: Paratype. Occurrence: catalogNumber: RMNH.ARA.18252; recordedBy: A. Floren; individualCount: 1; sex: female; lifeStage: adult; otherCatalogNumbers: https://doi.org/10.3535/85R-G3E-4M0; occurrenceID: 2177F899-9F22-50D9-867C-50C57D8C6544; Taxon: scientificName: Phintelloidesscandens; Location: island: Borneo; country: Malaysia; stateProvince: Sabah; locality: Mt. Kinabalu N. P., Sorinsim; verbatimElevation: 500-700 m; verbatimCoordinates: 6°5'N 116°50'E; decimalLatitude: 6.0833333333333; decimalLongitude: 116.83333333333; Event: samplingProtocol: canopy fogging tree 8 Vitex pinnata (Verb.); eventDate: 1997-03-10; habitat: 15 year old secondary forest; fieldNotes: (Loc 46), refog 1 after 8 days; Record Level: institutionID: https://ror.org/0566bfb96; institutionCode: RMNH; basisOfRecord: PreservedSpecimen

Type status: Paratype. Occurrence: catalogNumber: RMNH.ARA.18253; recordedBy: A. Floren; individualCount: 1; sex: female; lifeStage: adult; otherCatalogNumbers: https://doi.org/10.3535/7WH-VHP-M1K; occurrenceID: 1128E2B4-04D3-55A3-BB15-62B1C402FEA2; Taxon: scientificName: Phintelloidesscandens; Location: island: Borneo; country: Malaysia; stateProvince: Sabah; locality: Mt. Kinabalu N. P., Sorinsim; verbatimElevation: 500-700 m; verbatimCoordinates: 6°5'N 116°50'E; decimalLatitude: 6.0833333333333; decimalLongitude: 116.83333333333; Event: samplingProtocol: canopy fogging Vitex pinnata (Verb.); eventDate: 1997-02-26; habitat: 15 year old secondary forest; fieldNotes: (Loc 38, tree code Vp267); Record Level: institutionID: https://ror.org/0566bfb96; institutionCode: RMNH; basisOfRecord: PreservedSpecimen

Type status: Other material. Occurrence: catalogNumber: RMNH.ARA.18254; recordedBy: A. Floren; individualCount: 1; sex: male; lifeStage: adult; otherCatalogNumbers: https://doi.org/10.3535/1CE-SXA-2BC; occurrenceID: 59A912D4-409B-50F8-B622-3F4579A0536F; Taxon: scientificName: Phintelloidesscandens; Location: island: Borneo; country: Malaysia; stateProvince: Sabah; locality: Crocker Range, near Keningau; verbatimCoordinates: 5°26’N 116°08’E; decimalLatitude: 5.4333333333333; decimalLongitude: 116.13333333333; Event: samplingProtocol: fogging canopy Melanopis (Euphorbiaceae); eventDate: 2001-02-19; habitat: 10 year old isolated secondary forest; fieldNotes: (CRI.9, tree code Me305, DSC 2286-88); Record Level: institutionID: https://ror.org/0566bfb96; institutionCode: RMNH; basisOfRecord: PreservedSpecimen

Type status: Other material. Occurrence: catalogNumber: RMNH.ARA.18255; recordedBy: A. Floren; individualCount: 1; sex: male; lifeStage: adult; otherCatalogNumbers: https://doi.org/10.3535/0RA-FVV-2DL; occurrenceID: 2E93698A-6195-532B-B995-C54B919B114F; Taxon: scientificName: Phintelloidesscandens; Location: island: Borneo; country: Malaysia; stateProvince: Sabah; locality: Crocker Range, near Keningau; verbatimCoordinates: 5°26’N 116°08’E; decimalLatitude: 5.4333333333333; decimalLongitude: 116.13333333333; Event: samplingProtocol: fogging canopy Melanopis (Euphorbiaceae); eventDate: 2001-02-18; habitat: 20 year old isolated secondary forest; fieldNotes: (CRII.4, tree code Me310); Record Level: institutionID: https://ror.org/0566bfb96; institutionCode: RMNH; basisOfRecord: PreservedSpecimen

Type status: Other material. Occurrence: catalogNumber: RMNH.ARA.18256; recordedBy: A. Floren; individualCount: 1; sex: male; lifeStage: adult; otherCatalogNumbers: https://doi.org/10.3535/SZV-FJV-MRM; occurrenceID: EDE8AAB1-77E1-5BC6-914F-ACBAF994BA57; Taxon: scientificName: Phintelloidesscandens; Location: island: Borneo; country: Malaysia; stateProvince: Sabah; locality: Crocker Range, near Keningau; verbatimCoordinates: 5°26’N 116°08’E; decimalLatitude: 5.4333333333333; decimalLongitude: 116.13333333333; Event: samplingProtocol: fogging canopy Melanopis (Euphorbiaceae); eventDate: 2001-02-18; habitat: 20 year old isolated secondary forest; fieldNotes: (CR II.3, DSC 1142-52, tree code Me309); Record Level: institutionID: https://ror.org/0566bfb96; institutionCode: RMNH; basisOfRecord: PreservedSpecimen

Type status: Other material. Occurrence: catalogNumber: RMNH.ARA.18257; recordedBy: A. Floren; individualCount: 1; sex: female; lifeStage: adult; otherCatalogNumbers: https://doi.org/10.3535/FEE-JQY-GA4; occurrenceID: 768B340C-2DCC-5A68-928E-685939849112; Taxon: scientificName: Phintelloidesscandens; Location: island: Borneo; country: Malaysia; stateProvince: Sabah; locality: Crocker Range, near Keningau; verbatimCoordinates: 5°26’N 116°08’E; decimalLatitude: 5.4333333333333; decimalLongitude: 116.13333333333; Event: samplingProtocol: fogging canopy Melanopis (Euphorbiaceae); eventDate: 2001-02-18; habitat: 20 year old isolated secondary forest; fieldNotes: (CRII.5, DSC 1178-1185, treecode Me311); Record Level: institutionID: https://ror.org/0566bfb96; institutionCode: RMNH; basisOfRecord: PreservedSpecimen

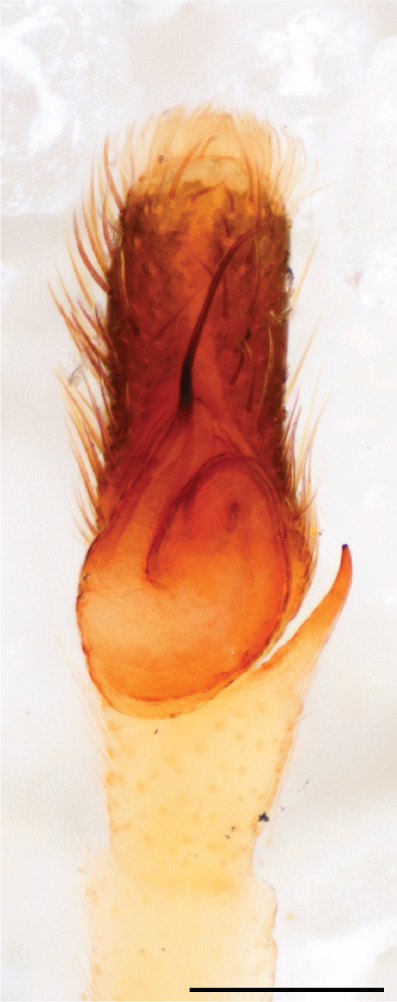

Description

MALE. Total length males 4.30 - 5.40 mm. Holotype: carapace dark brown with white tuft between and behind AME eyes and black protruding setae hooding AM eyes (Fig. 15a), area between and behind PME and between AME and ALE covered with short white setae, intermitted with protruding brown setae; in posterior half of thorax centre a pale narrow longitudinal stripe (Fig. 12a) instead of a diamond-shaped white area in other known species. Posterior margin of thorax with appressed black setae, opposite front edge of abdomen bearing brushes of dark erect hair in the middle, white on sides as in females (Fig. 12a, c), reduced or lost in some specimens. Chelicerae long, divergent (Fig. 12b), medially slanting. Maxillae distally widened with angular tip and a toothlike sub-tip. Leg I with dark femur, tibia and metatarsus dark with one or more pale rings; legs II-IV pale with narrow dark rings around the joints and femora with prolateral dark lengthwise stripes, tibia I and II with 2 pairs of ventral spines, metatarsi I and II with one pair at base (Fig. 12a). Abdomen gradually tapering, dorsally with wide buff coloured central band (colour in live specimens unknown), covered with very small scales, on either side a wide lateral band covered with white scales (Fig. 12a); venter covered with big round to triangular buff to brown scales and flanked by a pale area with some sparce very small iridescent scales (Fig. 12b). Pedipalp with base of palpal femur dark, rest light, patella and tibia white, cymbium dorsally dark except base and tip (Fig. 14b). Tip of etb extends slightly beyond tip of sperm duct loop (Fig. 14a, c). Embolus relatively short (e.g., compared to P.jesudasi, Kanesharatnam and Benjamin 2019: fig. 18A).

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., photographs of male ane female preserved specimens

Figure 12a.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., male habitus, dorsal view, RMNH.ARA.18255, scale bar 2 mm

Figure 12b.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., male habitus, ventral view, RMNH.ARA.18255

Figure 12c.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., female habitus, dorsal view, RMNH.ARA.18257, scale bar 1 mm

Figure 12d.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., female habitus, ventral view, RMNH.ARA.18257, scale bar 1 mm

Measurements. Total length 4.80. Carapace 2.20 long, 1.50 wide, 1.10 high, chelicerae 0.8 long, abdomen 2.50 long, 1.10 wide. Legs: I 4.90 (1.50 long [0.40 wide] – 0.70 – 1.20 – 0.90 – 0.60, leg II 3.80 (1.10 [0.30 wide] – 0.50 – 0.80 – 1.00 – 0.40) leg III 4.00 (1.20 [0.30 wide] – 0.50 – 0.80 – 0.90 – 0.60 leg IV 4.40 (1.40 [0.35 wide)]– 0.50 – 0.90 – 1.10 – 0.50. Palp -0.7 – 0.3 – 0.25 – 0.6, width cymbium 0.25.

FEMALE. Paratype. Carapace paler than that of male, head pale, lacking white area in eye region, but with bunch of white setae on clypeus. Anterior eyes surrounded with white hair, a white moustache is present below the front eyes (Fig. 13c). present. Femur I with a prolateral and retrolateral dark longitudinal stripe, a prolateral one on leg II and III and none on femur IV (Fig. 13a). All legs with black rings at base and tip of the patella and tibia. Abdomen pale, dispersed with brownish scales, mostly on the sides (Fig. 13d). Venter uniform pale, very small iridescent scales (Fig. 13b). Palps uniform pale. Epigyne (Fig. 13) similar to C.lauta and C.volupe, spermathecae considerably larger, touching, “bird’s neck” short and thin and lacking a twist; outer margin (ora) of bird’s beak reaching down till 2/3 of spermathecae. In dorsal view, upturned fertilization ducts pointing to each other with acute tip behind are visible behind spermathecae (Fig. 13d). For hypothetical illustration of copulatory mechanics, see Fig. 16.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., photographs and illustrations of female reproductive structures

Figure 13a.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., female epigynum, ventral view, RMNH.ARA.18257, scale bars 0.2 mm

Figure 13b.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., female vulva, dorsal view, RMNH.ARA.18257, scale bars 0.2 mm

Figure 13c.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., female epigynum, ventral view, illustration, scale bars 0.2 mm

Figure 13d.

Phintelloidesscandens sp. nov., female vulva, dorsal view, illustration, scale bars 0.2 mm

Measurements. Paratype. Total length 4.50. Carapace 1.90 long, 1.30 wide, 1.10 high, abdomen 2.75 long, 1.72 wide. 1.42 high. Legs: I 2.90 (0.90 [0.35 wide]– 0.50 – 0.60 - 0.50 – 0.40) leg II 2.55 (0.80 ([0.25 wide] – 0.35 – 0.55 – 0.45 – 0.40), leg III 3.00 (0.95 – 0.40 – 0.60 – 0.70 – 0.35) leg IV 3.80 (1.15 – 0.50 – 0.75 – 0.90 – 0.50).

Diagnosis

Males of P.scandens differ from most Phintelloides species by the absence of a white tuft on the clypeus in front of the AME in males (Fig. 15a). The thorax in males has a narrow white V-shaped strip in the middle instead of a diamond-shaped white area in other species. The female carapace (Fig. 12c) has markings similar to the male and unlike the characteristic pattern of P.jesudasi. The male abdomen (Fig. 12a), has a wide dark median band on the abdomen between a pair of yellow lateral bands as in P.jesudasi and in P.versicolor. The female abdomen pattern is the reverse of that in males (Fig. 12c). The structure of the male and female reproductive organs are generally similar to those of C.lauta and P.jesudasi. The male can be distinguished by differences in the colour of palpal segments, and by the form of the etb, which is longer and more slender than in P.jesudasi and fairly uniform in width, running alongside the tegulum over most of its length (Fig. 14c); the embolus has the same length as that in jesudasi, the proximal tegular lobe is smaller. The female wears a narrow bunch of white setae on the clypeus (Fig. 15b); epigyne lacks the widening of the bird’s-neck, the atrium is smaller and narrow, the ora (outer rim) is clearly longer; the spermathecae are round and larger than in any other species of the genus, with a diameter equal to the length of the ducts (Fig. 13).

Etymology

From the Latin word scandere, to climb, referring to the fact that all known specimens were collected by fogging tree canopies.

Distribution