ABSTRACT

Bacterial biofilm communities are associated with profound physiological changes that lead to novel properties compared to the properties of individual (planktonic) bacteria. The study of biofilm-associated phenotypes is an essential step toward control of deleterious effects of pathogenic biofilms. Here we investigated lipopolysaccharide (LPS) structural modifications in Escherichia coli biofilm bacteria, and we showed that all tested commensal and pathogenic E. coli biofilm bacteria display LPS modifications corresponding to an increased level of incorporation of palmitate acyl chain (palmitoylation) into lipid A compared to planktonic bacteria. Genetic analysis showed that lipid A palmitoylation in biofilms is mediated by the PagP enzyme, which is regulated by the histone-like protein repressor H-NS and the SlyA regulator. While lipid A palmitoylation does not influence bacterial adhesion, it weakens inflammatory response and enhances resistance to some antimicrobial peptides. Moreover, we showed that lipid A palmitoylation increases in vivo survival of biofilm bacteria in a clinically relevant model of catheter infection, potentially contributing to biofilm tolerance to host immune defenses. The widespread occurrence of increased lipid A palmitoylation in biofilms formed by all tested bacteria suggests that it constitutes a new biofilm-associated phenotype in Gram-negative bacteria.

IMPORTANCE

Bacterial communities called biofilms display characteristic properties compared to isolated (planktonic) bacteria, suggesting that some molecules could be more particularly produced under biofilm conditions. We investigated biofilm-associated modifications occurring in the lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a major component of all Gram-negative bacterial outer membrane. We showed that all tested commensal and pathogenic biofilm bacteria display high incorporation of a palmitate acyl chain into the lipid A part of LPS. This lipid A palmitoylation is mediated by the PagP enzyme, whose expression in biofilm is controlled by the regulatory proteins H-NS and SlyA. We also showed that lipid A palmitoylation in biofilm bacteria reduces host inflammatory response and enhances their survival in an animal model of biofilm infections. While these results provide new insights into the biofilm lifestyle, they also suggest that the level of lipid A palmitoylation could be used as an indicator to monitor the development of biofilm infections on medical surfaces.

INTRODUCTION

Biofilm communities developing on medical and industrial surfaces constitute a recognized reservoir of bacterial pathogens, and control of biofilm-associated infections is a major focus of microbiology at this time (1, 2). Identification of key biofilm determinants in several pathogens led to potential antibiofilm strategies based either on prevention of initial bacterial adhesion, inhibition of biofilm maturation, biofilm dispersion, or eradication of highly antibiotic-tolerant biofilm bacteria (3, 4). Study of gene expression and physiological changes occurring during biofilm formation suggested that specific molecules might be associated with the biofilm environment (5–8). Consistently, several compounds were shown to accumulate within biofilms, including biofilm matrix components, antiadhesion molecules, and amino acids (9–11).

We previously showed that formation of biofilms by certain Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains induced reversible loss of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) O antigen and alteration of lipid A that contributes to modulating the host inflammatory response to P. aeruginosa biofilms (12). LPS is a major component of all Gram-negative bacterial outer membranes, and although its structure varies in response to certain environmental stimuli (13), few studies have investigated modifications in LPS structure in biofilms (12, 14, 15). Here, we compared Escherichia coli LPS from biofilm and planktonic bacteria and identified a reversible increased LPS modification corresponding to incorporation of a palmitate acyl chain to lipid A (palmitoylation) mediated by the PagP enzyme. While the appearance of this LPS modification is correlated to the ability of the bacteria to form biofilms, it occurs progressively and only after several days in very long stationary-phase culture bacteria. We show that pagP is negatively regulated by H-NS, which itself is under the biofilm-regulated control of the SlyA regulator. We demonstrate that increased lipid A palmitoylation in biofilm bacteria decreases the inflammatory response and increases biofilm bacterial survival in an in vivo rat model of catheter-associated biofilm infection. Since increased lipid A palmitoylation also occurs in biofilms formed by a wide range of Gram-negative bacteria, our study therefore identified a new biofilm phenotype, which could be used as a biofilm biomarker to monitor Gram-negative bacterial biofilm-associated infections.

RESULTS

Evidence for biofilm-associated LPS modification in E. coli biofilm.

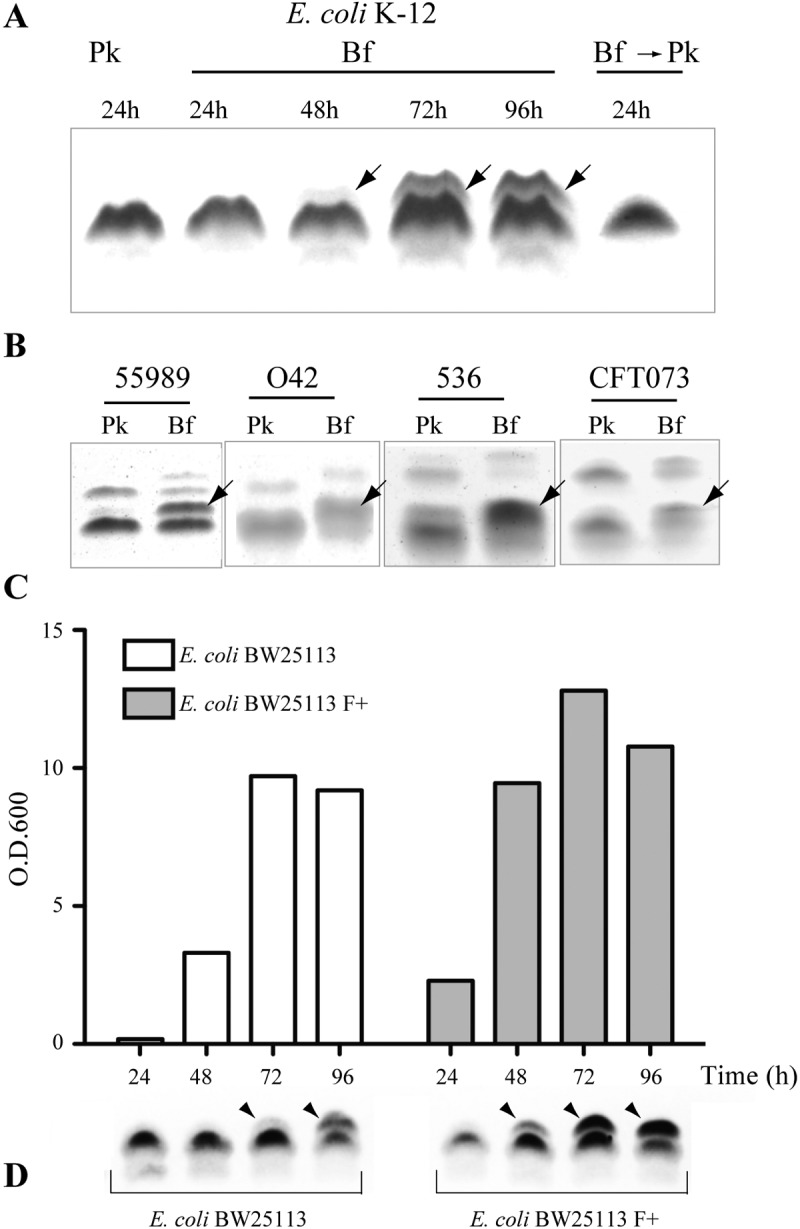

To identify potential modifications of LPS in E. coli biofilms, we compared patterns of rough LPS (Ra, with no O antigen) produced in biofilm and planktonic E. coli K-12 BW25113 bacteria. Tricine SDS-PAGE analysis revealed that LPS extracted from 96-h mature biofilm grown in microfermentors with constant medium renewal had a higher molecular weight than LPS species extracted from 15- to 24-h overnight stationary-phase planktonic culture (Fig. 1A; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). An additional band was progressively detected along with aging biofilms and disappeared in LPS extracted from 96-h biofilm bacteria reinoculated under planktonic conditions (Fig. 1A). We also observed an additional LPS band associated with biofilms formed by various pathogenic E. coli strains (Fig. 1B). To further investigate the correlation between biofilm formation and appearance of the additional LPS band, we compared the E. coli BW25113 strain with its closely related derivative, the BW25113 F strain, forming more biofilm than BW25113 due to the presence of the biofilm-promoting F conjugative plasmid (Fig. 1C) (16). Analysis of LPS extracted from biofilms formed by E. coli BW25113 and BW25113 F strains at different time points showed that the additional LPS band appeared more rapidly in the BW25113 F strain (48 h versus 72 h) (Fig. 1D). Whereas this suggested a link between biofilm capacity and LPS modification, monitoring LPS profiles in planktonic cultures (without medium renewal) also revealed the emergence of the additional LPS band in aging planktonic culture (48 h and beyond) (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). In contrast, the regular renewal of the growth medium in these very late stationary-phase cultures, performed to limit nutrient exhaustion and approximate microfermentor conditions, significantly reduced the appearance of this band (Fig. S2B). These results therefore suggested that the studied LPS modification occurs in mature biofilms and under conditions created in unusually long planktonic cultures.

FIG 1 .

LPS modification in E. coli biofilm bacteria. (A) Tricine SDS-PAGE/periodate-silver staining analysis of LPS extracted from planktonic (Pk) or biofilm (Bf) E. coli K-12 BW25113. The arrows indicate a modified LPS band. To assess whether biofilm bacteria reinoculated in planktonic conditions still display a modified LPS profile, bacteria grown for 96 h were recultured overnight in planktonic conditions (Bf → Pk). (B) LPS analysis of 24-h planktonic or 96-h biofilm cultures from pathogenic E. coli strains, including enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) strains 55989 and O42 and uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) strains 536 and CFT073. (C) Comparison, at different time points, of biofilm biomass produced in continuous-flow microfermentors by E. coli K-12 BW25113 strain with its closely related derivative BW25113 F, carrying the biofilm-promoting F conjugative plasmid. O.D.600, optical density at 600 nm. (D) Tricine SDS-PAGE/periodate-silver staining analysis of LPS extracted from corresponding biofilm cultures.

LPS modification associated with Enterobacteriaceae biofilms corresponds to lipid A palmitoylation.

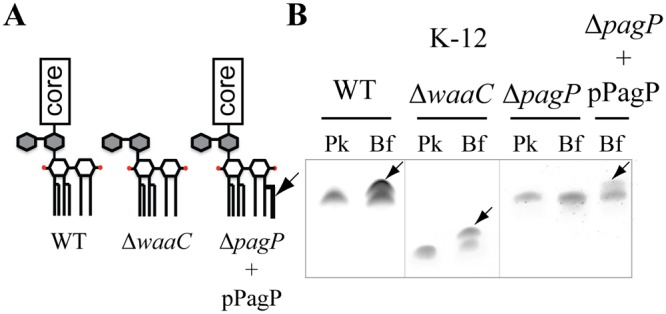

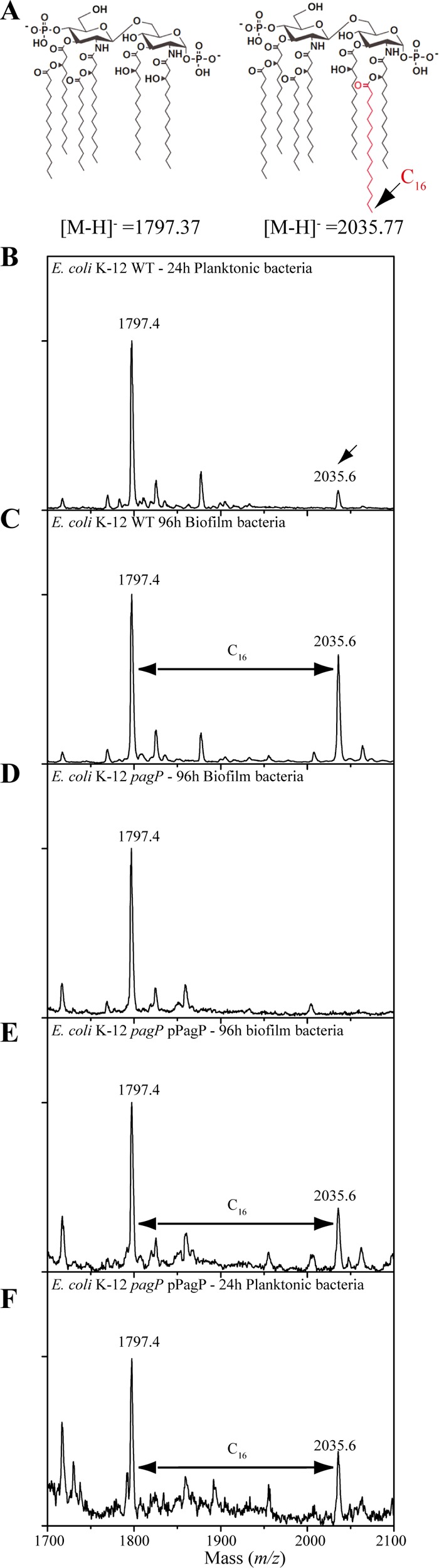

The presence of the additional band in LPS extracted from rough E. coli K-12, and enteropathogenic E. coli strains 55989 and O42 and uropathogenic 536 and CFT073 smooth E. coli strains (with O antigen) suggested that the modification occurs in the smallest common LPS part in all tested strains, corresponding to lipid A and the inner core. Moreover, detection of the additional band in LPS extracted from 96-h biofilms formed by E. coli K-12 BW25113 waaC deep rough mutant suggested that the biofilm-associated modification could take place on lipid A bound to a 3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonic acid (Kdo) disaccharide part of the LPS (lipid A-Kdo2) (Fig. 2A and B). Of the E. coli enzymes potentially involved in chemical modifications of the lipid A-Kdo2 portion, four are common to E. coli 55989, O42, 536, CFT073, and K-12 strains: ArnT (amino-arabinose addition to lipid A), EptA (phosphoethanolamine addition to lipid A), EptB (phosphoethanolamine addition to Kdo) and PagP (palmitate addition to lipid A) (17). We analyzed LPS extracted from planktonic (24-h) and biofilm (96-h) bacteria corresponding to arnT, eptA, eptB, and pagP E. coli mutants and detected the biofilm-associated LPS band in biofilm formed by all mutants except the pagP mutant (data not shown and Fig. 2B). Complementation of the E. coli pagP mutant by a plasmid expressing pagP restored LPS modification in 96-h biofilm bacteria (Fig. 2B). These results suggested lipid A palmitoylation in biofilm bacteria (18). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization−time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) analysis of lipid A in 24-h planktonic bacteria showed one major peak at m/z = 1,797.4, corresponding to a hexa-acylated nonpalmitoylated lipid A species and only a minor species at m/z = 2,035.6, corresponding to a hepta-acylated palmitoylated lipid A species (Fig. 3A and B). In contrast, the spectrum obtained for 96-h biofilm showed two major peaks, at m/z = 1,797.4 and m/z = 2,035.6, thereby indicating significant lipid A palmitoylation under biofilm conditions. We did not detect palmitoylated lipid A in E. coli ΔpagP biofilm bacteria (Fig. 3D), while production of palmitoylated lipid A was restored upon complementation by plasmid pPagP under planktonic and biofilm conditions (Fig. 3E and F). MALDI-TOF MS analysis of LPS extracted from E. coli waaC deep rough (Re) mutant grown under planktonic condition already showed significant lipid A palmitoylation, potentially due to increased membrane stress-dependent pagP expression (19). However, comparison between planktonic and biofilm bacteria showed that the only detected modification occurring in biofilm is a difference at m/z = 2,035 and m/z = 2,475 peaks, corresponding to palmitoylated lipid A and palmitoylated lipid A-Kdo2, respectively (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Finally, biofilm-associated lipid A palmitoylation is a general feature, since MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis of lipid A extracted from biofilms formed by several pathogenic E. coli strains as well as various Gram-negative bacteria, including Serratia marcescens, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Citrobacter koseri species, consistently showed increased levels of lipid A palmitoylation compared to corresponding planktonic cultures (Table 1 and Fig. S4A to S4D).

FIG 2 .

The LPS modification in E. coli biofilm bacteria is pagP dependent. (A) Schematic representation of rough LPS from wild-type (WT) E. coli K-12 BW25113, ΔwaaC mutant, and ΔpagP mutant complemented with pPagP plasmid. (B) LPS analysis of 24-h planktonic (Pk) or 96-h biofilm (Bf) cultures from wild-type pathogenic E. coli K-12 strain and ΔwaaC mutant, ΔpagP mutant, and ΔpagP mutant complemented with plasmid pPagP.

FIG 3 .

E. coli biofilm bacteria add a palmitate chain to their lipid A. (A) Proposed structures corresponding to major peaks detected by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, according to previously reported structures of Gram-negative bacterial lipid A. (B to F) MALDI-TOF analysis of lipid A extracted from E. coli K-12 BW25113 bacteria. The E. coli K-12 BW25113 bacteria were 24-h planktonic bacteria (B), 96-h BW25113 biofilm bacteria (C), 96-h BW25113 ΔpagP biofilm bacteria (D), 96-h BW25113 ΔpagP mutant biofilm bacteria complemented with plasmid pPagP (E), and 96-h BW25113 ΔpagP mutant planktonic bacteria complemented with plasmid pPagP (F).

TABLE 1 .

Lipid A palmitoylation level in 24-h planktonic and 96-h biofilm bacteria of different Gram-negative bacterial speciesa

| Bacterial species | Palmitoylation levelb |

Bf/Pk ratioc | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pk | Bf | ||

| E. coli strains | |||

| K-12 BW25113 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 6 |

| K-12 BW25113 ΔwaaC | 0.94 | 1.35 | 1.4 |

| 55989 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 3.7 |

| O42 | 0.62 | 1.3 | 2.1 |

| 536 | 1 | 1.35 | 1.35 |

| CFT073 | 0.96 | 1.72 | 1.8 |

| Citrobacter koseri | 1.2 | 2.7 | 2.3 |

| Serratia marcescens SM365 | 2.4 | 4.3 | 1.8 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae strains | |||

| LM21 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 2.3 |

| CH994 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 2.3 |

| CH995 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| CH996 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 2.3 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains | |||

| PA14 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 1.3 |

| BJN8 | 0.23 | 0.5 | 2.17 |

| BJN33 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.83 |

| BJN53 | 0.1 | 0.34 | 3.4 |

Some of the corresponding spectra can be found in Fig. 2 and in Fig. S3 and S4 in the supplemental material.

The palmitoylation level was determined as the peak area of the major palmitoylated species, normalized by the peak area of the corresponding nonpalmitoylated species (Fig. S4).

Ratio of the palmitoylation level in biofilm to the palmitoylation level in planktonic conditions, with all other conditions identical in the analysis.

H-NS represses pagP transcription in planktonic cultures.

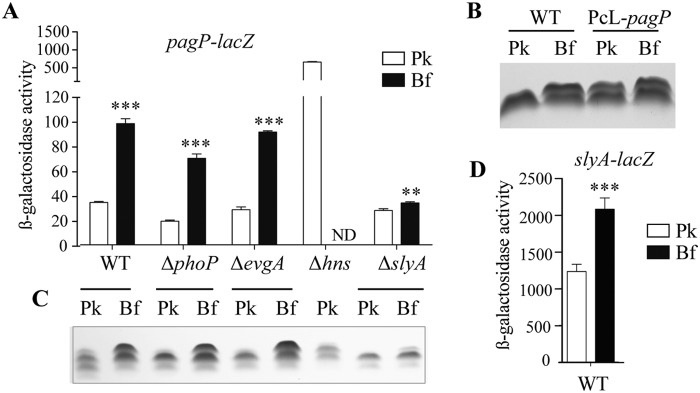

To investigate regulation of lipid A palmitoylation in biofilm, we introduced a lacZ transcriptional fusion downstream of the pagP stop codon in E. coli BW25113 (transcriptional operon fusion) and observed a 3-fold increase in β-galactosidase activity in 96-h biofilm compared to planktonic culture (Fig. 4A). Moreover, constitutive expression of pagP in E. coli BW25113 PcL-pagP led to production of the additional LPS band under both planktonic and biofilm conditions (Fig. 4B), suggesting that lipid A palmitoylation is regulated at the transcriptional level. Previous studies involved PhoP and EvgA as positive regulators of pagP expression in response to magnesium limitation (19, 20); however, deletion in these 2 genes had no effect on pagP expression or on the LPS profile, demonstrating that biofilm-associated palmitoylation is PhoP and EvgA independent (Fig. 4A and C). Interestingly, the emergence of the additional LPS band under very late stationary-phase conditions (96 h of planktonic culture) is also PhoP and EvgA independent and is not inhibited upon supplementation with excess magnesium in the culture medium (see Fig. S5A in the supplemental material). Moreover, inactivation of various stress response regulators, including cpxR, rcsB, pspF, oxyR, soxR, arcA, rpoS, relA, and luxS, had no impact on lipid A palmitoylation (Fig. S5B). To identify regulators of pagP expression in E. coli, we took advantage of the white color displayed by E. coli BW25113 pagP-lacZ colonies on 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) agar plates, and we used TnSC189 mariner-based transposon mutagenesis to screen for blue BW25113 pagP-lacZ mutants derepressed for pagP expression. We identified 7 dark blue colonies corresponding either to trivial TnSC189 insertion upstream of the pagP-lacZ fusion or to insertion into the hns gene, which encodes the global silencing protein repressor H-NS (21). To confirm the role of H-NS in pagP expression, we monitored pagP expression in E. coli BW25113 Δhns pagP-lacZ planktonic cultures and observed 18-fold-increased pagP expression in the hns deletion mutant compared to the parental strain (Fig. 4A). Consistent with this result, the previously biofilm-associated LPS band could be detected in 24-h planktonic bacteria in LPS extracted from E. coli Δhns pagP-lacZ mutant (Fig. 4C). Since the ability of this mutant to form a biofilm was strongly affected, we could not meaningfully monitor pagP expression or LPS palmitoylation in biofilms. Complementation of the Δhns pagP-lacZ mutant with plasmid pBAD33-hns decreased expression of pagP (Fig. S6A), therefore demonstrating that H-NS represses lipid A palmitoylation in E. coli planktonic bacteria.

FIG 4 .

Lipid A palmitoylation is transcriptionally regulated by H-NS and SlyA. (A) E. coli BW25113 pagP-lacZ strains with the phoP, evgA, hns, or slyA gene deleted were grown overnight in planktonic conditions (Pk) or in biofilms (Bf) for 96 h. β-Galactosidase activity was measured. Values are means plus standard deviations (SDs) from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was assessed using an unpaired t test. Values for planktonic bacteria that are significantly different from the values for biofilm bacteria are indicated by asterisks as follows: **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. ND, not determined. (B) Tricine SDS-PAGE analysis of LPS from E. coli BW25113 and BW25113 PcL-pagP, which constitutively expresses the pagP gene, grown in planktonic cultures (Pk) overnight or in biofilms (Bf) for 96 h. (C) LPSs from the strains shown in panel A were analyzed by Tricine SDS-PAGE. (D) The E. coli BW25113 slyA-lacZ strain was grown overnight under planktonic conditions (Pk) or in biofilms (Bf) for 96 h, and β-galactosidase activity was measured.

The anti-H-NS factor SlyA activates pagP transcription in mature biofilms.

Increased pagP expression under mature biofilm conditions suggested potential alleviation of H-NS repression by another E. coli regulator. Analysis of the pagP promoter region actually revealed three sequences closely matching the proposed consensus binding site for SlyA, an anti-H-NS factor that antagonizes H-NS binding on a number of cell envelope E. coli genes (see Fig. S6B in the supplemental material) (22–25). We therefore tested the contribution of SlyA to pagP regulation and compared pagP expression in E. coli BW25113 pagP-lacZ and BW25113 ΔslyA pagP-lacZ both under planktonic and biofilm conditions. We observed that a slyA deletion very significantly reduced pagP induction in biofilm, with only a 1.3-fold induction of pagP expression in the ΔslyA background, compared to 2.9-fold induction observed in the wild-type (WT) background (Fig. 4A). Consistent with this result, analysis of LPS extracted from the ΔslyA mutant showed only a minor modification of the LPS profile between planktonic and biofilm conditions (Fig. 4C). However, complementation of the slyA mutation in E. coli ΔslyA pagP-lacZ mutant with plasmid pCA24N-slyA partially restored biofilm-associated induction of pagP expression (Fig. S6C). Finally, we compared slyA expression under planktonic and biofilm conditions, and we observed a 1.7-fold induction of slyA expression in biofilm, therefore confirming the role of SlyA in biofilm-associated pagP expression (Fig. 4D).

Lipid A palmitoylation increases in vivo survival of biofilm bacteria.

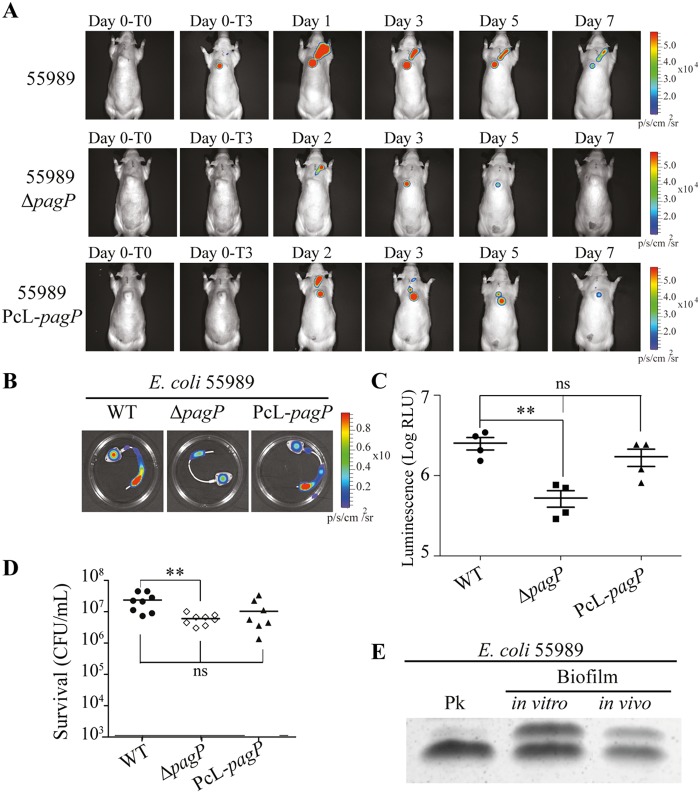

To investigate the role of lipid A palmitoylation in biofilm bacteria, we first compared E. coli wild-type and ΔpagP and PcL-pagP mutant capacities to form in vitro biofilm on microtiter plates or continuous-flow microfermentors. We observed that neither the lack of, nor constitutive PagP-dependent palmitoylation, affected commensal E. coli BW25113 or pathogenic E. coli 55989 in vitro biofilm formation (see Fig. S7A and S7B in the supplemental material). We then used our previously described in vivo rat model of biofilm-associated infection in a totally implanted venous access port (TIVAP) (26) to compare the extent of in vivo biofilm development of bioluminescent wild-type, ΔpagP, or PcL-pagP E. coli 55989 derivatives in an inoculated TIVAP (Fig. 5A). Monitoring of bioluminescent biofilm biomass formed in an implanted TIVAP during the 7 days of the experiment showed a decrease in luminescence in the TIVAP colonized by E. coli 55989 ΔpagP compared to wild-type and PcL-pagP strains (Fig. 5B and C). However, inoculated TIVAP showed no initial difference in CFU recovered 3 h after inoculation, indicating that the lack of lipid A palmitoylation has no effect on initial adhesion on TIVAP in vivo (Fig. S7C). Nevertheless, we observed a significant decrease in 55989 ΔpagP bacterial number at day 7 compared to TIVAP colonized with wild-type 55989 bacteria (Fig. 5D). Since in vivo formation of E. coli 55989 biofilm in the chamber of the implanted device also led to PagP-dependent modifications of the LPS profile (Fig. 5E), we investigated the potential contribution of lipid A palmitoylation to control of biofilm infection dynamics by the host.

FIG 5 .

pagP-dependent lipid A palmitoylation increases in vivo survival of biofilm bacteria. (A) Totally implanted venous access ports (TIVAPs) implanted in rats were inoculated with wild-type bioluminescent E. coli 55989, ΔpagP, or PcL-pagP strain. The bioluminescent signal was monitored for 7 days after inoculation. T0, just before injection; T3, 3 h after injection. (B) Seven days after inoculation, the TIVAPs were flushed, rats were sacrificed 2 h after the TIVAPs were flushed, and the TIVAPs were removed. (C and D) The biofilm biomass was assessed by bioluminescence measurement (log relative luminescence units [RLU] [p/s/cm/s2]) (C) and by CFU count (n = 8) (D). Each value represents the value for an individual rat. The means (short black lines) ± standard deviations (error bars) for the groups of rats are shown in panel C. In panel D, the means (short black lines) for the groups of rats are shown. Values that are statistically significantly different (P < 0.01) by an unpaired t test are indicated by bars and two asterisks. Values that are not significantly different are indicated by bars labeled ns. (E) E. coli 55989 was grown in 24-h planktonic cultures (Pk), in 96-h biofilm culture on a glass spatula (biofilm in vitro), or in TIVAPs implanted in rats for 7 days (biofilm in vivo). LPS extracts were analyzed by Tricine SDS-PAGE.

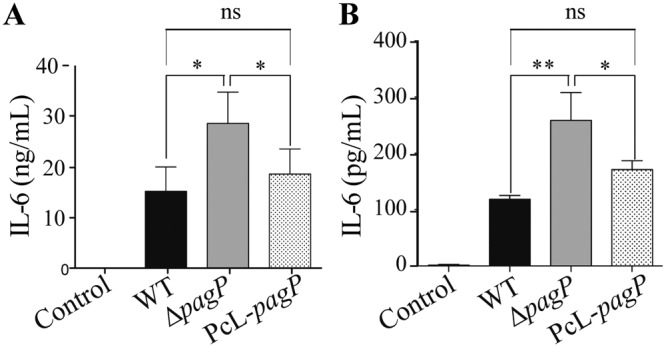

Lipid A palmitoylation in E. coli was previously shown to decrease the inflammatory activity of lipid A (27). To test in a controlled manner whether nonpalmitoylated E. coli 55989 ΔpagP lipid A triggers a higher inflammatory response than palmitoylated biofilm bacteria, we injected E. coli 55989 wild-type ΔpagP and PcL-pagP biofilm bacteria intravenously into rats. Two hours after injection, we used rat serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to measure the amount of interleukin-6 (IL-6) proinflammatory cytokine and observed a significant increase in the IL-6 level induced by E. coli 55989 ΔpagP biofilm bacteria compared to wild-type and PcL-pagP bacteria (Fig. 6A). We consistently observed a 2-fold reduction in the release of IL-6 by the macrophage when brought into contact with bacteria producing palmitoylated lipid A (Fig. 6B). Moreover, palmitoylated E. coli biofilm bacteria also displayed resistance to the antimicrobial peptide protegrine-1 (PG-1) compared to unpalmitoylated bacteria (see Fig. S8 in the supplemental material). Taken together, these results showed that lipid A palmitoylation increased biofilm bacteria survival in vivo, potentially by damping the inflammatory response to and host immune defenses against biofilm bacteria.

FIG 6 .

Lipid A palmitoylation decreases the inflammatory response to biofilm bacteria. (A) Biofilms of E. coli 55989 derivatives were grown on a glass spatula for 96 h and injected intravenously in rats (6.5 × 108 wild-type bacteria, 4 × 108 ΔpagP bacteria, 4 × 108 PcL-pagP bacteria). Sera were collected 2 h after injection, and the amount of IL-6 was measured by ELISA (mean plus SD; n = 4). (B) J774A.1 macrophage-like cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 0.3 for 2 h with E. coli 55989 derivatives grown on a glass spatula for 96 h. The amount of IL-6 in the supernatants was measured by ELISA (mean plus SD; n = 3). Statistical significance was assessed using an unpaired t test. Values that are significantly different are indicated by bars and asterisks as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Values that are not significantly different are indicated by bars labeled ns.

DISCUSSION

LPS is a major structural component of the outer membrane of the Gram-negative bacterial envelope composed of three covalently linked domains, including the lipid A (or endotoxin) hydrophobic anchor, the core region, and the O-antigen polymer (28). LPS size and composition are highly dynamic and vary according to the strain and growth conditions, contributing to bacterial adaptation to changing environments (29). Here we identified a new biofilm phenotype corresponding to a high level of lipid A palmitoylation in biofilms formed by various Gram-negative bacteria and depending on the outer membrane β-barrel palmitoyl transferase PagP.

Regulation of lipid A palmitoylation was previously studied as a response to a variety of host factors or conditions and shown to be both transcriptional and posttranslational (19, 30–32). Indeed, the PagP enzyme can remain dormant until its phospholipid substrates reach the external leaflet of the outer membrane, where the PagP active site is located. Migration of phospholipids to the external leaflet occurs in response to a variety of membrane perturbations, including antimicrobial peptides, chelating agents, or temperature shift (32). Alternatively, pagP transcription can also be induced in response to several cues, for instance to magnesium limitation, triggering the PhoP-PhoQ two-component regulatory system (32, 33).

Whereas the basal level of lipid A palmitoylation in E. coli LPS is very low in planktonic batch cultures (31), here, we identified biofilm as an environment naturally inducing palmitoylation of lipid A. We show that the PhoPQ system is not involved in biofilm-associated PagP-dependent lipid A palmitoylation, which is also not inhibited upon supplementation with excess magnesium in the culture medium. In contrast, we show that pagP expression is repressed by H-NS and that biofilm-associated induction of SlyA, a DNA binding protein that inhibits H-NS activity, leads to pagP derepression. Although the signal-inducing slyA and pagP expression in mature biofilm formed under continuous culture conditions is as yet unknown, we observed that lipid A palmitoylation was also SlyA and H-NS dependent and PhoP and EvgA independent in very late stationary-phase cultures grown over long incubation time (48 h and beyond). Interestingly, regular medium renewal in these extended planktonic cultures very significantly reduced lipid A palmitoylation. This suggests that lipid A palmitoylation could be induced by extreme physicochemical conditions present in both biofilm and very late stationary-phase planktonic cultures. Such conditions could correspond to general stress induced within inner biofilm layers, potentially including major nutrient starvation or microaerobic conditions. In this study, we showed, however, that inactivation of various envelope stress and general response regulators, including cpxR, rcsB, pspF, oxyR, soxR, arcA, rpoS, relA, and luxS, had no impact on lipid A palmitoylation. Alternatively, slyA and resulting pagP induction could also be triggered by the production of yet uncharacterized metabolites or a physiological process produced within biofilm and very late stationary-phase planktonic cultures. The contribution of other factors or conditions inducing lipid A palmitoylation in biofilm is under investigation.

Lipid A palmitoylation is known to stabilize the LPS outer membrane leaflet by increasing hydrophobic interactions between neighboring LPS molecules (34). Hence, palmitoylation of lipid A could correspond to an adaptation to LPS destabilization potentially occurring under biofilm conditions wherein bacteria are subjected to various physical and chemical stresses (7, 35). However, we showed that lipid A palmitoylation does not contribute to the ability of E. coli to form biofilms in vitro. Although the biofilm biomass of a PcL-pagP strain that constitutively synthesizes palmitoylated lipid A is not significantly altered, measures were variable compared to those of the wild-type strain. This difference could indicate that deregulation of pagP expression and lipid A palmitoylation could be slightly detrimental for biofilm formation. In contrast, the absence of pagP reduces biofilm formation in a clinically relevant in vivo model of device infection in rat (26, 36). Palmitoylation of lipid A was shown to attenuate the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-mediated inflammatory response induced by lipid A (37). This is consistent with the fact that biofilm bacteria with palmitoylated lipid A also displayed decreased cytokine responses in macrophage culture cell lines and in vivo. Our results therefore suggest that lipid A palmitoylation protects biofilm bacteria from the host immune response and thus contributes to the general tolerance of bacterial biofilms during infections.

A biofilm is a highly heterogeneous environment in which bacteria undergo phenotypic differentiation, raising the question of the distribution of bacteria with palmitoylated lipid A within the biofilm population. Since our lipid A analyses were performed on all bacteria composing the biofilm, they likely reflect the average level of palmitoylation within a population composed of palmitoylated and nonpalmitoylated bacteria. Use of increased pagP and slyA expression as reporter tools will help clarify the spatial patterns of palmitoylation within biofilm microniches or layers.

Biofilm bacteria shed from colonized devices are sources of systemic bloodstream infections (38). In the absence of efficient methods to treat biofilms, replacement of contaminated devices is required in many clinical situations in order to prevent biofilm-associated infections (39, 40). Removal of implanted devices suspected of infection constitutes a difficult therapeutic decision, based as much on the nature of the pathogen colonizing the device than on actual evidence for the presence of biofilms (5). Currently, there is no routine approach to demonstrate the presence of biofilms on medical devices, and development of simplified detection methods could therefore assist clinicians in evaluating the extent of biofilm-associated risk of medical device infections (5). Our findings suggest that monitoring the lipid A palmitoylation level could be used as an indicator of the presence of high-density population of Gram-negative bacterial pathogens. While sensitivity and specificity issues will need to be addressed, we are currently evaluating whether clinical samples withdrawn from totally implantable venous access port of infected patients can be used to detect lipid A palmitoylation using immunoassay or mass spectrometry.

We showed that increased lipid A palmitoylation could be a widespread characteristic of Gram-negative bacterial biofilms. While the pagP gene is present in all sequenced E. coli and enterobacterial genomes, sequence analyses indicate that PagP homologs are also present in numerous other Proteobacteria, especially beta- and gammaproteobacteria. Interestingly, P. aeruginosa has a divergent homolog of enterobacterial PagP, and the analysis of four clinical strains showed increased level of lipid A palmitoylation in biofilms. Consistently, cystic fibrosis (CF) isolates that form biofilms in the lungs of CF patients also display palmitoylated lipid A, while isolates from patients with other conditions and isolates from the environment do not (41, 42). Interestingly, Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium PagP enzyme was also recently shown to palmitoylate outer membrane glycerophospholipids and generate triacylated palmitoyl-glycerophospholipids (43). This therefore suggests that increased PagP activity in biofilms could also lead to increased palmitoylation of glycerophospholipids.

In conclusion, we showed that, in addition to known characteristic properties of biofilm bacteria, including tolerance to stress, 3-dimensional architecture, and production of extracellular matrix components, increased level of PagP activity leading to palmitoylation remodeling of lipid A constitutes a new biofilm-associated phenotype potentially contributing to resistance of Gram-negative bacterial biofilms to stress and host immune responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

Animals were housed in the Institut Pasteur animal facilities, accredited by the French Ministry of Agriculture for performing experiments on live rodents (permit A-75-1061). Work on animals was performed in compliance with French and European regulations on care and protection of laboratory animals (European Commission directive 2010/63; French law 2013-118, 6 February 2013). The protocols used in this study for the animal model, catheter placement, in vivo biofilm formation, and in vivo study of inflammatory responses were approved by the ethics committee of “Paris Centre et Sud no. 59” under reference no. 2012-0045.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains used in this study are described in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: kanamycin, 50 µg/ml; chloramphenicol, 25 µg/ml; ampicillin, 100 µg/ml; and zeocin, 50 µg/ml. Biofilm formation in continuous-flow microfermentors was performed as previously described in reference 16. Briefly, continuous-flow microfermentors containing a removable glass spatula were used as described (http://www.pasteur.fr/recherche/unites/Ggb/matmet.html) to maximize biofilm development and minimize planktonic growth. Inoculation was performed by dipping the glass spatula for 2 min in a culture adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1 from overnight bacterial cultures grown in M63B1 minimal medium [KH2PO4 100 mM, (NH4)2SO4 15 mM, MgSO4 0.8 mM, vitamin B1 3 µM, pH 7.4] supplemented with 0.4% glucose and the appropriate antibiotics. The spatula was then reintroduced into the microfermentor, and biofilm culture was performed at 37°C in M63B1 with glucose. Biofilm biomass produced at different time points was rapidly resuspended in 15 ml of microfermentor medium (OD600 < 0.01), and biofilm bacterial LPS was analyzed after centrifugation and elimination of the resuspension supernatant.

Planktonic and biofilm cultures were performed in M63B1 medium supplemented with 0.4% glucose at 37°C.

Transposon mutagenesis, strain construction, and molecular techniques.

TnSC189 mariner-based transposon of E. coli pagP-lacZ was performed as described in reference 44. Transposon insertion sites were determined as described in reference 45. Constitutive expression of the pagP gene was carried out by insertion of the previously described ampPcL genetic element in front of pagP at its native chromosomal location, leading to the constitutive expression of the pagP gene from the phage lambda constitutive promoter (λPr) (23). Insertion of the ampPcL cassette and deletion of the pagP gene were performed using the λ-Red recombinase gene replacement system and a three-step PCR procedure described previously (46, 47). The primers used are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. When necessary, the antibiotic resistance marker of the inserted cassette was removed using the flippase-encoding pCP20 plasmid. For construction of pagP-lacZ and slyA-lacZ fusions, the same principle was used. The lacZ-zeo cassette was inserted downstream of the stop codon of the target gene. To construct pagP-lacZ derivatives, mutations were transferred by P1vir transduction from Keio collection E. coli JW1116 (ΔphoP), JW2366 (ΔevgA), JW1225 (Δhns), and JW5267 (ΔslyA) (48) mutants into the E. coli BW25113 pagP-lacZ strain. All constructs were confirmed by PCR and sequencing.

LPS analysis by Tricine SDS-PAGE.

Bacteria (108) were pelleted and resuspended in 100 µl of lysing buffer (Bio-Rad) containing 1% SDS, 20% glycerol, 100 mM Tris (pH 6.8), and Coomassie blue G-250. Lysates were heated at 100°C for 10 min; then, proteinase K was added at 1 mg/ml and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. These samples (4 µl) were electrophoresed in a tricine SDS-PAGE system, which improves resolution of the low-molecular-weight LPS band, using a 4% stacking gel and a 20% separating gel (49). LPSs were then visualized by the periodate-silver staining method adapted from reference 50. Gels were immersed in fixing solution (30% ethanol, 10% acetic acid) for 1 h, washed three times for 5 min each time in water, oxidized in 0.7% periodic acid for 10 min, and washed three times for 5 min each time in water. Gels were then immersed for 1 min in 0.02% thiosulfate pentahydrate, rinsed quickly in water, and stained in 25 mM silver nitrate for 10 min. After a 15-s wash in water, gels were developed in 3.5% potassium carbonate and 0.01% formaldehyde. Development was stopped in 4% Tris base and 2% acetic acid for 30 min.

Direct lipid A isolation from bacterial cells.

Lipid A was isolated directly by hydrolysis of bacterial cells as described in references 51 and 52. Briefly, 5 mg of lyophilized bacterial cells was suspended in 100 µl of a mixture of isobutyric acid−1 M ammonium hydroxide (5:3 [vol/vol]) and kept for 1.5 h at 100°C in a screw-cap test tube in a Thermomixer system. The suspension was cooled in ice water and centrifuged (2,000 × g, 5 min). The recovered supernatant was diluted with 2 volumes of water and lyophilized. The sample was then washed once with 100 µl of methanol (by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 5 min). Finally, lipid A was extracted from the pellet in 50 µl of a mixture of chloroform, methanol, and water (3:1.5:0.25 [vol/vol/vol]).

MALDI-TOF MS analysis.

LPS samples were dispersed in water at 1 µg/µl. Lipid A extracts in chloroform-methanol-water were used directly in this mixture of solvents. In both cases, a few microliters of sample solution was desalted with a few grains of ion-exchange resin Dowex 50W-X8 (H+). Aliquots of 0.5 to 1 µl of the solution were deposited on the target, and the spot was then overlaid with matrix solution and left to dry. Dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as the matrix. It was dissolved at 10 mg/ml in 0.1 M citric acid solution in the same solvents as those used for the analytes (53). Different analyte/matrix ratios (1:2, 1:1, and 2:1 [vol/vol]) were tested to obtain the best spectra. Negative- and positive-ion mass spectra were recorded on a PerSeptive Voyager-DE STR time of flight mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems) in the linear mode with delayed extraction. The ion-accelerating voltage was set at [minus]20 kV, and the extraction delay time was adjusted to obtain the best resolution and signal-to-noise ratio.

β-Galactosidase activity assay.

To determine the level of β-galactosidase enzyme activity, bacteria were grown in M63B1 minimal medium supplemented with 0.4% glucose for 24 h under planktonic conditions or for 96 h under continuous-flow biofilm conditions. β-Galactosidase activity was assayed in triplicate as described previously (54) and expressed in Miller units.

Animal model. (i) Catheter placement.

Totally implanted venous access ports (TIVAPs) were surgically implanted in CD/SD (IGS:Crl) rats (Charles River) as described previously (26). Briefly, the port was implanted at dorsal midline toward the lower end of the thoracic vertebrae, and the catheter was inserted into the jugular vein. Prior to inoculation of clinical strains, all rats were checked for the absence of infection by plating 100 µl blood and by monitoring rats for the absence of luminescence signals.

(ii) TIVAP contamination in rats and in vivo biofilm formation.

The inoculum dose of 104 cells for overnight grown cultures of E. coli 55989 pAT881 wild type (WT), ΔpagP, or PcL-pagP were injected into the port in a 50-µl volume. Planktonic bacteria were removed after 3 h of injection. Progression of colonization was monitored using an IVIS100 imaging system. Rats were sacrificed either 3 h or 7 days postinjection, and TIVAPs were harvested. Serial dilutions from samples were plated on LB agar medium for enumerating CFU/ml.

(iii) In vivo inflammatory response.

To estimate the host inflammatory response due to LPS palmitoylation, E. coli 55989 WT, ΔpagP, or PcL-pagP grown in a microfermentor for 4 days were adjusted to 109 cells per 500 µl and injected into rats intravenously. Rats were sacrificed 2 h after injection, and blood was harvested aseptically and analyzed for IL-6 cytokine release in serum using ELISA.

Statistical analysis.

Two-tailed unpaired Student t test analyses were performed using Prism 5.0 for Mac OS X (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Each experiment was performed at least 3 times. Statistical significance was indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Strains and plasmids used in this study

Primers used in this study

Mature biofilm formation by E. coli K-12 BW25113. Pictures were taken after 24, 48, 72, and 96 h of growth on glass slides inserted into continuous-flow microfermentors. Download

LPS modification in aging planktonic culture of E. coli K-12 BW25113. (A) Tricine SDS-PAGE/periodate-silver staining analysis of LPS extracted at different time points from a planktonic culture of E. coli strain K-12 BW25113. The modified LPS band is indicated with a black arrow. (B) Tricine SDS-PAGE/periodate-silver staining analysis of LPS extracted at different time points from a similar planktonic culture of E. coli strain K-12 BW25113, in which growth medium was renewed every 24 h by resuspension of the bacteria in fresh medium after centrifugation of the whole culture and elimination of the used medium. Download

Palmitoylation is the only modification detected in biofilm of the E. coli K-12 ΔwaaC deep rough mutant. (A and B) The E. coli K-12 ΔwaaC mutant was grown under planktonic conditions (Pk 24 h) (A) or in biofilm (Bf 96 h) (B), and LPS was extracted and analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Nonpalmitoylated and palmitoylated lipid A species are indicated by blue and red arrows, respectively. The peak at m/z = 2,035 corresponds to palmitoylated lipid A, while the peak at m/z = 2,475 corresponds to palmitoylated lipid A-Kdo2. Download

Biofilm-associated palmitoylation is common among members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. (A to H) E. coli 55989 (A), E. coli CFT073 (B), Klebsiella pneumoniae LM21 (C), Klebsiella pneumoniae CH994 (D), Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 (E), Pseudomonas aeruginosa BJN8 (F), Citrobacter koseri (G), and Serratia marcescens 365 (H) were grown under planktonic (Pk 24 h) conditions or in biofilms (Bf 96 h). Corresponding lipid A was extracted and analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Nonpalmitoylated and palmitoylated lipid A species are indicated by blue and red arrows, respectively. Download

Effects of deletion of regulators on lipid A palmitoylation. (A) Wild-type E. coli BW25113 and ΔphoP, ΔevgA, Δhns, and ΔslyA mutants were grown under planktonic conditions for 24 and 96 h and under biofilm conditions for 96 h. LPSs were analyzed by SDS-PAGE/periodate-silver staining. The hns mutant was strongly affected, and LPS palmitoylation in biofilm could not be meaningfully tested. n.d., not determined. (B) Wild-type BW25113 and stress membrane regulator mutants (ΔcpxR, ΔbaeR, ΔrcsB, and ΔpspF mutants) were grown under planktonic conditions for 24 h and under biofilm conditions for 96 h. LPSs were analyzed by SDS-PAGE/periodate-silver staining. Download

Complementation of Δhns and ΔslyA mutants. (A) E. coli BW25113 complemented with plasmid pBAD33 [BW25113(pBAD33)], BW25113 Δhns pagP-lacZ(pBAD33), and BW25113 Δhns pagP-lacZ(pBAD33-hns) were grown to log phase in M63B1 with 0.4% glucose and then induced in M63B1 with 0.4% glycerol and 0.2% arabinose. After 2 h of induction, expression of pagP was assessed by measuring β-galactosidase activity (Miller units). (B) Promoter region of the pagP gene, showing putative SlyA binding sites (boxes) and SlyA binding site consensus. (C) E. coli BW25113(pCA24N), BW25113 ΔslyA pagP-lacZ(pCA24N), and BW25113 ΔslyA pagP-lacZ(pCA24N-slyA) were grown in planktonic cultures overnight in M63B1 with 0.4% glucose (Pk) or in biofilms for 96 h (Bf) in M63B1 with 0.4% glucose and 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). The average values ± SDs from three independent experiments are shown. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-tailed unpaired t test, and values that were significantly different (P < 0.05) are indicated by an asterisk. Download

Lipid A palmitoylation effect on bacterial adhesion. (A) Biofilms of wild-type E. coli 55989 and ΔpagP and PcL-pagP mutants were grown in continuous-flow microfermentors for 96 h. Images of the biofilm formed in a microfermentor and on an internal glass slide are shown. (B) Biofilms formed in the microfermentor and on the internal glass slide were resuspended, and the optical density at 600 nm was measured (n = 3). (C) Palmitoylation had no effect on initial adhesion to TIVAPs in vivo. TIVAPs implanted in rats were inoculated with bioluminescent E. coli 55989, 55989 ΔpagP, or 55989 PcL-pagP. Three hours after inoculation, the TIVAPs were surgically removed, and the biofilm biomass was assessed by CFU count (n = 4). Download

PG-1 antimicrobial peptide sensitivity assay. To assess the resistance of E. coli 55989 wild-type and PcL-pagP strains to protegrine-1 (PG-1) peptide (AnaSpec, Fremont, CA), bacterial biofilms were grown on polyvinyl chloride (PVC) microtiter plates for 24 h in M63B1 medium supplemented with 0.4% glucose. Planktonic bacteria were then removed by washing the wells twice. M63B1 medium supplemented with glucose with or without 20 µg/ml PG-1 was then added to the wells and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The wells were washed, biofilms were collected, and bacterial survival was determined by CFU counts (n = 3). Statistical significance was assessed using a two-tailed unpaired t test and values that were significantly different (P < 0.05) are indicated by an asterisk. Download

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J.-M. Cavaillon for his interest throughout the course of this study. We thank S. Létoffé, D. Lebeaux, and O. Rendueles for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Institut Mérieux-Institut Pasteur collaborative research program and by the French Government’s Investissement d’Avenir program, Laboratoire d’Excellence “Integrative Biology of Emerging Infectious Diseases” (grant ANR-10-LABX-62-IBEID).

Footnotes

Citation Chalabaev S, Chauhan A, Novikov A, Iyer P, Szczesny M, Beloin C, Caroff M, Ghigo J-M. 2014. Biofilms formed by Gram-negative bacteria undergo increased lipid A palmitoylation, enhancing in vivo survival. mBio 5(4):e01116-14. doi:10.1128/mBio.01116-14.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hall-Stoodley L, Costerton JW, Stoodley P. 2004. Bacterial biofilms: from the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:95–108. 10.1038/nrmicro821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Høiby N, Ciofu O, Johansen HK, Song ZJ, Moser C, Jensen PO, Molin S, Givskov M, Tolker-Nielsen T, Bjarnsholt T. 2011. The clinical impact of bacterial biofilms. Int. J. Oral Sci. 3:55–65. 10.4248/IJOS11026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rendueles O, Ghigo JM. 2012. Multi-species biofilms: how to avoid unfriendly neighbors. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36:972–989. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00328.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Römling U, Balsalobre C. 2012. Biofilm infections, their resilience to therapy and innovative treatment strategies. J. Intern. Med. 272:541–561. 10.1111/joim.12004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hall-Stoodley L, Stoodley P, Kathju S, Høiby N, Moser C, Costerton JW, Moter A, Bjarnsholt T. 2012. Towards diagnostic guidelines for biofilm-associated infections. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 65:127–145. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.00968.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Whiteley M, Bangera MG, Bumgarner RE, Parsek MR, Teitzel GM, Lory S, Greenberg EP. 2001. Gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Nature 413:860–864. 10.1038/35101627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beloin C, Valle J, Latour-Lambert P, Faure P, Kzreminski M, Balestrino D, Haagensen JA, Molin S, Prensier G, Arbeille B, Ghigo JM. 2004. Global impact of mature biofilm lifestyle on Escherichia coli K-12 gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 51:659–674. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03865.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ghigo JM. 2003. Are there biofilm-specific physiological pathways beyond a reasonable doubt? Res. Microbiol. 154:1–8. 10.1016/S0923-2508(02)00012-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Valle J, Da Re S, Schmid S, Skurnik D, D’Ari R, Ghigo JM. 2008. The amino acid valine is secreted in continuous-flow bacterial biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 190:264–274. 10.1128/JB.01405-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rendueles O, Travier L, Latour-Lambert P, Fontaine T, Magnus J, Denamur E, Ghigo JM. 2011. Screening of Escherichia coli species biodiversity reveals new biofilm-associated antiadhesion polysaccharides. mBio 2(3):e00043-11. 10.1128/mBio.00043-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rendueles O, Beloin C, Latour-Lambert P, Ghigo JM. 2014. A new biofilm-associated colicin with increased efficiency against biofilm bacteria. ISME J. 8:1275–1288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ciornei CD, Novikov A, Beloin C, Fitting C, Caroff M, Ghigo JM, Cavaillon JM, Adib-Conquy M. 2010. Biofilm-forming Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteria undergo lipopolysaccharide structural modifications and induce enhanced inflammatory cytokine response in human monocytes. Innate Immun. 16:288–301. 10.1177/1753425909341807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Raetz CR, Whitfield C. 2002. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71:635–700. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beveridge TJ, Makin SA, Kadurugamuwa JL, Li Z. 1997. Interactions between biofilms and the environment. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 20:291–303. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1997.tb00315.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hansen SK, Rainey PB, Haagensen JA, Molin S. 2007. Evolution of species interactions in a biofilm community. Nature 445:533–536. 10.1038/nature05514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ghigo JM. 2001. Natural conjugative plasmids induce bacterial biofilm development. Nature 412:442–445. 10.1038/35086581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Raetz CR, Reynolds CM, Trent MS, Bishop RE. 2007. Lipid A modification systems in gram-negative bacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76:295–329. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.010307.145803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bishop RE, Gibbons HS, Guina T, Trent MS, Miller SI, Raetz CR. 2000. Transfer of palmitate from phospholipids to lipid A in outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria. EMBO J. 19:5071–5080. 10.1093/emboj/19.19.5071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jia W, El Zoeiby A, Petruzziello TN, Jayabalasingham B, Seyedirashti S, Bishop RE. 2004. Lipid trafficking controls endotoxin acylation in outer membranes of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 279:44966–44975. 10.1074/jbc.M404963200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eguchi Y, Okada T, Minagawa S, Oshima T, Mori H, Yamamoto K, Ishihama A, Utsumi R. 2004. Signal transduction cascade between EvgA/EvgS and PhoP/PhoQ two-component systems of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 186:3006–3014. 10.1128/JB.186.10.3006-3014.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dorman CJ. 2004. H-NS: a universal regulator for a dynamic genome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:391–400. 10.1038/nrmicro883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Corbett D, Bennett HJ, Askar H, Green J, Roberts IS. 2007. SlyA and H-NS regulate transcription of the Escherichia coli K5 capsule gene cluster, and expression of slyA in Escherichia coli is temperature-dependent, positively autoregulated, and independent of H-NS. J. Biol. Chem. 282:33326–33335. 10.1074/jbc.M703465200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Da Re S, Le Quéré B, Ghigo JM, Beloin C. 2007. Tight modulation of Escherichia coli bacterial biofilm formation through controlled expression of adhesion factors. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3391–3403. 10.1128/AEM.02625-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McVicker G, Sun L, Sohanpal BK, Gashi K, Williamson RA, Plumbridge J, Blomfield IC. 2011. SlyA protein activates fimB gene expression and type 1 fimbriation in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Biol. Chem. 286:32026–32035. 10.1074/jbc.M111.266619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stapleton MR, Norte VA, Read RC, Green J. 2002. Interaction of the Salmonella typhimurium transcription and virulence factor SlyA with target DNA and identification of members of the SlyA regulon. J. Biol. Chem. 277:17630–17637. 10.1074/jbc.M110178200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chauhan A, Lebeaux D, Decante B, Kriegel I, Escande MC, Ghigo JM, Beloin C. 2012. A rat model of central venous catheter to study establishment of long-term bacterial biofilm and related acute and chronic infections. PLoS One 7:e37281. 10.1371/journal.pone.0037281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kawasaki K, Ernst RK, Miller SI. 2004. 3-O-deacylation of lipid A by PagL, a PhoP/PhoQ-regulated deacylase of Salmonella typhimurium, modulates signaling through Toll-like receptor 4. J. Biol. Chem. 279:20044–20048. 10.1074/jbc.M401275200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang X, Quinn PJ. 2010. Lipopolysaccharide: biosynthetic pathway and structure modification. Prog. Lipid Res. 49:97–107. 10.1016/j.plipres.2009.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Trent MS, Stead CM, Tran AX, Hankins JV. 2006. Diversity of endotoxin and its impact on pathogenesis. J. Endotoxin Res. 12:205–223. 10.1179/096805106X118825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Reinés M, Llobet E, Llompart CM, Moranta D, Pérez-Gutiérrez C, Bengoechea JA. 2012. Molecular basis of Yersinia enterocolitica temperature-dependent resistance to antimicrobial peptides. J. Bacteriol. 194:3173–3188. 10.1128/JB.00308-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhou Z, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CR. 1999. Lipid A modifications characteristic of Salmonella typhimurium are induced by NH4VO3 in Escherichia coli K12. Detection of 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose, phosphoethanolamine and palmitate. J. Biol. Chem. 274:18503-18514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bishop RE. 2008. Structural biology of membrane-intrinsic beta-barrel enzymes: sentinels of the bacterial outer membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1778:1881–1896. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Guo L, Lim KB, Poduje CM, Daniel M, Gunn JS, Hackett M, Miller SI. 1998. Lipid A acylation and bacterial resistance against vertebrate antimicrobial peptides. Cell 95:189–198. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81750-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nikaido H. 2003. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:593–656. 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Prigent-Combaret C, Vidal O, Dorel C, Lejeune P. 1999. Abiotic surface sensing and biofilm-dependent regulation of gene expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181:5993–6002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chauhan A, Lebeaux D, Ghigo JM, Beloin C. 2012. Full and broad-spectrum in vivo eradication of catheter-associated biofilms using gentamicin-EDTA antibiotic lock therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:6310–6318. 10.1128/AAC.01606-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kawasaki K, Ernst RK, Miller SI. 2004. Deacylation and palmitoylation of lipid A by Salmonellae outer membrane enzymes modulate host signaling through Toll-like receptor 4. J. Endotoxin Res. 10:439–444. 10.1179/096805104225006264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lebeaux D, Fernández-Hidalgo N, Chauhan A, Lee S, Ghigo JM, Almirante B, Beloin C. 2014. Management of infections related to totally implantable venous-access ports: challenges and perspectives. Lancet Infect. Dis. 14:146–159. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70266-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, Craven DE, Flynn P, O’Grady NP, Raad II, Rijnders BJ, Sherertz RJ, Warren DK. 2009. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49:1–45. 10.1086/599117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zimmerli W, Moser C. 2012. Pathogenesis and treatment concepts of orthopaedic biofilm infections. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 65:158–168. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.00938.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ernst RK, Moskowitz SM, Emerson JC, Kraig GM, Adams KN, Harvey MD, Ramsey B, Speert DP, Burns JL, Miller SI. 2007. Unique lipid A modifications in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from the airways of patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Infect. Dis. 196:1088–1092. 10.1086/521367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thaipisuttikul I, Hittle LE, Chandra R, Zangari D, Dixon CL, Garrett TA, Rasko DA, Dasgupta N, Moskowitz SM, Malmström L, Goodlett DR, Miller SI, Bishop RE, Ernst RK. 2014. A divergent Pseudomonas aeruginosa palmitoyltransferase essential for cystic fibrosis-specific lipid A. Mol. Microbiol. 91:158–174. 10.1111/mmi.12451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dalebroux ZD, Matamouros S, Whittington D, Bishop RE, Miller SI. 2014. PhoPQ regulates acidic glycerophospholipid content of the Salmonella typhimurium outer membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111:1963–1968. 10.1073/pnas.1316901111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ferrières L, Hémery G, Nham T, Guérout AM, Mazel D, Beloin C, Ghigo JM. 2010. Silent mischief: bacteriophage Mu insertions contaminate products of Escherichia coli random mutagenesis performed using suicidal transposon delivery plasmids mobilized by broad-host-range RP4 conjugative machinery. J. Bacteriol. 192:6418–6427. 10.1128/JB.00621-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Da Re S, Ghigo JM. 2006. A CsgD-independent pathway for cellulose production and biofilm formation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 188:3073–3087. 10.1128/JB.188.8.3073-3087.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chaveroche MK, Ghigo JM, d’Enfert C. 2000. A rapid method for efficient gene replacement in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:e97. 10.1093/nar/28.22.e97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Derbise A, Lesic B, Dacheux D, Ghigo JM, Carniel E. 2003. A rapid and simple method for inactivating chromosomal genes in Yersinia. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 38:113–116. 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00181-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2:2006.0008. 10.1038/msb4100050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lesse AJ, Campagnari AA, Bittner WE, Apicella MA. 1990. Increased resolution of lipopolysaccharides and lipooligosaccharides utilizing Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J. Immunol. Methods 126:109–117. 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90018-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tsai CM, Frasch CE. 1982. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 119:115–119. 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90673-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. El Hamidi A, Tirsoaga A, Novikov A, Hussein A, Caroff M. 2005. Microextraction of bacterial lipid A: easy and rapid method for mass spectrometric characterization. J. Lipid Res. 46:1773–1778. 10.1194/jlr.D500014-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tirsoaga A, El Hamidi A, Perry MB, Caroff M, Novikov A. 2007. A rapid, small-scale procedure for the structural characterization of lipid A applied to Citrobacter and Bordetella strains: discovery of a new structural element. J. Lipid Res. 48:2419–2427. 10.1194/jlr.M700193-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Therisod H, Labas V, Caroff M. 2001. Direct microextraction and analysis of rough-type lipopolysaccharides by combined thin-layer chromatography and MALDI mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 73:3804–3807. 10.1021/ac010313s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Miller JH. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Strains and plasmids used in this study

Primers used in this study

Mature biofilm formation by E. coli K-12 BW25113. Pictures were taken after 24, 48, 72, and 96 h of growth on glass slides inserted into continuous-flow microfermentors. Download

LPS modification in aging planktonic culture of E. coli K-12 BW25113. (A) Tricine SDS-PAGE/periodate-silver staining analysis of LPS extracted at different time points from a planktonic culture of E. coli strain K-12 BW25113. The modified LPS band is indicated with a black arrow. (B) Tricine SDS-PAGE/periodate-silver staining analysis of LPS extracted at different time points from a similar planktonic culture of E. coli strain K-12 BW25113, in which growth medium was renewed every 24 h by resuspension of the bacteria in fresh medium after centrifugation of the whole culture and elimination of the used medium. Download

Palmitoylation is the only modification detected in biofilm of the E. coli K-12 ΔwaaC deep rough mutant. (A and B) The E. coli K-12 ΔwaaC mutant was grown under planktonic conditions (Pk 24 h) (A) or in biofilm (Bf 96 h) (B), and LPS was extracted and analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Nonpalmitoylated and palmitoylated lipid A species are indicated by blue and red arrows, respectively. The peak at m/z = 2,035 corresponds to palmitoylated lipid A, while the peak at m/z = 2,475 corresponds to palmitoylated lipid A-Kdo2. Download

Biofilm-associated palmitoylation is common among members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. (A to H) E. coli 55989 (A), E. coli CFT073 (B), Klebsiella pneumoniae LM21 (C), Klebsiella pneumoniae CH994 (D), Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 (E), Pseudomonas aeruginosa BJN8 (F), Citrobacter koseri (G), and Serratia marcescens 365 (H) were grown under planktonic (Pk 24 h) conditions or in biofilms (Bf 96 h). Corresponding lipid A was extracted and analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Nonpalmitoylated and palmitoylated lipid A species are indicated by blue and red arrows, respectively. Download

Effects of deletion of regulators on lipid A palmitoylation. (A) Wild-type E. coli BW25113 and ΔphoP, ΔevgA, Δhns, and ΔslyA mutants were grown under planktonic conditions for 24 and 96 h and under biofilm conditions for 96 h. LPSs were analyzed by SDS-PAGE/periodate-silver staining. The hns mutant was strongly affected, and LPS palmitoylation in biofilm could not be meaningfully tested. n.d., not determined. (B) Wild-type BW25113 and stress membrane regulator mutants (ΔcpxR, ΔbaeR, ΔrcsB, and ΔpspF mutants) were grown under planktonic conditions for 24 h and under biofilm conditions for 96 h. LPSs were analyzed by SDS-PAGE/periodate-silver staining. Download

Complementation of Δhns and ΔslyA mutants. (A) E. coli BW25113 complemented with plasmid pBAD33 [BW25113(pBAD33)], BW25113 Δhns pagP-lacZ(pBAD33), and BW25113 Δhns pagP-lacZ(pBAD33-hns) were grown to log phase in M63B1 with 0.4% glucose and then induced in M63B1 with 0.4% glycerol and 0.2% arabinose. After 2 h of induction, expression of pagP was assessed by measuring β-galactosidase activity (Miller units). (B) Promoter region of the pagP gene, showing putative SlyA binding sites (boxes) and SlyA binding site consensus. (C) E. coli BW25113(pCA24N), BW25113 ΔslyA pagP-lacZ(pCA24N), and BW25113 ΔslyA pagP-lacZ(pCA24N-slyA) were grown in planktonic cultures overnight in M63B1 with 0.4% glucose (Pk) or in biofilms for 96 h (Bf) in M63B1 with 0.4% glucose and 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). The average values ± SDs from three independent experiments are shown. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-tailed unpaired t test, and values that were significantly different (P < 0.05) are indicated by an asterisk. Download

Lipid A palmitoylation effect on bacterial adhesion. (A) Biofilms of wild-type E. coli 55989 and ΔpagP and PcL-pagP mutants were grown in continuous-flow microfermentors for 96 h. Images of the biofilm formed in a microfermentor and on an internal glass slide are shown. (B) Biofilms formed in the microfermentor and on the internal glass slide were resuspended, and the optical density at 600 nm was measured (n = 3). (C) Palmitoylation had no effect on initial adhesion to TIVAPs in vivo. TIVAPs implanted in rats were inoculated with bioluminescent E. coli 55989, 55989 ΔpagP, or 55989 PcL-pagP. Three hours after inoculation, the TIVAPs were surgically removed, and the biofilm biomass was assessed by CFU count (n = 4). Download

PG-1 antimicrobial peptide sensitivity assay. To assess the resistance of E. coli 55989 wild-type and PcL-pagP strains to protegrine-1 (PG-1) peptide (AnaSpec, Fremont, CA), bacterial biofilms were grown on polyvinyl chloride (PVC) microtiter plates for 24 h in M63B1 medium supplemented with 0.4% glucose. Planktonic bacteria were then removed by washing the wells twice. M63B1 medium supplemented with glucose with or without 20 µg/ml PG-1 was then added to the wells and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The wells were washed, biofilms were collected, and bacterial survival was determined by CFU counts (n = 3). Statistical significance was assessed using a two-tailed unpaired t test and values that were significantly different (P < 0.05) are indicated by an asterisk. Download