Abstract

Background

Depression is associated with an increased risk of mortality in cancer patients; it has been hypothesized that depression-associated alterations in cell aging mechanisms in particular, the telomere/telomerase maintenance system, may underlie this increased risk. We evaluated the association of depressive symptoms and telomere length to mortality and recurrence/progression in 464 bladder cancer patients.

Methods

We used the CES-D and SCID to assess current depressive symptoms and lifetime MDD, respectively, and telomere length was assessed from peripheral blood lymphocytes. Multivariate Cox regression was used to assess the association of depression, and telomere length to outcomes and the joint effect of both. Kaplan-Meier plots and log rank tests were used to compare survival time of subgroups by depression variables and telomere length.

Results

Patients with depressive symptoms (CES-D ≥16) had a 1.83-fold (95%CI= 1.08 to 3.08, P=0.024) increased risk of mortality compared to patients without depressive symptoms (CES-D < 16) and shorter disease-free survival time (P=0.004). Patients with both depressive symptoms and lifetime history of MDD were at 4.88-fold (95%CI=1.40 to 16.99; P=0.013) increased risk compared to patients with neither condition. Compared to patients without depressive symptoms and long telomere length, patients with depressive symptoms and short telomeres exhibited a 4-fold increased risk of mortality (HR=3.96, 95% CI=1.86 to 8.41, P=0.0003) and significantly shorter disease-free survival time (P<0.001).

Conclusion

Short telomere length and depressive symptoms are associated with bladder cancer mortality individually and jointly.

Impact

Further investigation of interventions that impact depression and telomere length may be warranted in cancer patients.

Keywords: Depression, telomere length, bladder cancer

Introduction

In the United States, bladder cancer is the fourth most frequently diagnosed cancer in men and eleventh in women, with an estimated 55,600 new cases and 10,510 deaths in 2012 (1). During the past 20 years, treatment of bladder cancer has not changed significantly and the outcomes for patients remain suboptimal (2). Even though grade, stage, and treatment are important prognostic predictors of bladder cancer outcome, current prediction models and nomograms are limited in accuracy and lack external validation (3). Incorporation of novel prognostic variables into current models and simultaneous evaluation of multiple factors has potential to improve outcome prediction (4).

There is compelling evidence that depression is associated with elevated mortality in the general population (5), and poor survival in aging-related diseases (6, 7). Prospective studies have found depression to be associated with 20% to 40% increased mortality in cancer patients (8, 9), although the association between depression and cancer incidence, recurrence, and progression remains inconclusive (9). Most studies have included mixed cancer types, or evaluated outcomes of common cancers, such as breast cancer (10, 11). No study has been conducted to assess the impact of depression on mortality in bladder cancer patients.

It has been hypothesized that depression may affect cancer mortality and progression through shared biochemical pathways that lead to an increase in cell damaging processes and a decrease in cell protective or restorative processes (12). One way in which such processes may mediate the effects of depression on cancer outcomes is through alterations in cell aging mechanisms, in particular, the telomere/telomerase maintenance system (12).

Telomeres are specialized repetitive DNA sequences at the ends of chromosomes that protect chromosomes and are critical in maintaining genomic integrity (13). Telomere attrition results in cellular senescence and apoptosis (13). Telomere dysfunction has been linked to many aging-related human diseases, including cancer. Several studies have found a relationship between shorter telomere length and major depressive disorder (MDD) (14–16).

Compared to extensive studies of telomere length in the context of modifiable risk factors (17) and disease risks (18), research on the relationship between telomere length and disease prognosis is sparse. One series of studies that prospectively examined the association between telomere length and mortality in cancer patients (19, 20), found that shorter telomere length was associated with increased all-cause mortality of cancer patients over a 10 and 15 year period.

The primary objective of the current study was to prospectively evaluate the association between baseline depressive symptoms, symptoms of lifetime MDD, and telomere length to all-cause mortality, recurrence and disease progression in 464 bladder cancer patients. We hypothesized that depressive symptoms, history of MDD, and short telomere length would each be associated with increased mortality and recurrence/progression, and that patients with current depressive symptoms and history of MDD would have shorter survival and greater likelihood for recurrence/progression than those who met criteria on only one of the depression measures. A secondary objective was to evaluate whether telomere length moderated the relationship between depressive symptoms/lifetime MDD and mortality and recurrence/progression outcomes, such that those with depressive symptoms and history of MDD with short telomere length would have the shortest survival time and greater likelihood for progression. We also evaluated whether telomere length mediated the association between depression symptoms and history of MDD and mortality, and recurrence/progression.

Materials and Methods

Study Population, Data Collection and Laboratory Assays

All of the human participation procedures were approved by the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Boards. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before enrollment.

Bladder cancer patients were recruited in an ongoing epidemiologic study of bladder cancer at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and Baylor College of Medicine. Patient recruitment began in 1999. Procedures for recruitment and eligibility criteria have been described previously (21). Briefly, incident bladder cancer patients were identified through a daily review of computerized appointment schedules. Patients were diagnosed within one year upon recruitment, were histologically confirmed with urinary bladder cancer, and had not received prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy before enrollment. There were no recruitment restrictions on age, gender, ethnicity or stage.

After written informed consent was obtained, trained MD Anderson staff interviewers administered a 45-minute structured risk factor questionnaire to collect data on demographic characteristics, social-economic status, detailed tobacco use history, lifestyles, occupational history, medical history and medications, and family history of cancer.

Current level of depressive symptom severity was assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), a 20-item self-report measure developed to assess depressive symptoms in community populations.(22) Patients with a CES-D score ≥ 16 were classified at screening as meeting criteria suggestive of current depression.(23)

Lifetime history of MDD was measured using the two cardinal items for major depressive episode from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorder (SCID) (24); these items assessed lifetime presence of depressed mood or anhedonia for two weeks or more. Patients were considered to have lifetime MDD if they endorsed one or both of the items.

Clinical data, including tumor size, grade, stage, presence of carcinoma in situ (CIS), number of tumor foci at diagnosis, intravesical therapy, dates of recurrence and progression events, systemic chemotherapy, radical cystectomy, pathologic findings at cystectomy, and vital status, were abstracted from medical charts. The date of death or date of last follow-up for patients alive or lost to follow up was recorded. The MD Anderson Tumor Registry conducts annual vital status follow-ups on all cancer patients. Computer matches are performed with MD Anderson appointment files to identify patients who have presented for a recent appointment. For those patients who have not had a visit within the past 12–15 months, letters are sent to the patient to ask about the patient’s health and vital status. If the patient does not respond to the letter, phone calls are made, and the social security death index is checked. The end point outcomes in this study included all-cause mortality which was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up, whichever came first. In addition, recurrence and progression were also recorded for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). Recurrence was defined as a newly found bladder tumor following a previous negative follow-up cystoscopy, and progression was defined as the transition from non-muscle-invasive to invasive or metastatic tumors (25).

Immediately after the interview, a 40 ml blood sample was collected in sodium-heparinized tubes. Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood using the QIAamp DNA blood Maxi Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The DNAs were stored in −80°C freezer for future use.

The relative overall telomere length was measured by real-time quantitative PCR as previously described (26). Briefly, the relative overall telomere length is proportional to the ratio (T/S) of the telomere repeat copy number and the single (human globulin) copy number. The T/S ratio of each sample was normalized to a calibrator DNA to standardize between different runs. The PCR reaction mixture (15 μL) for telomere amplification consists of 5 ng genomic DNA, 1 × SYBR Green Mastermix (Applied Biosystem), 200 nmol/L Tel-1 primer (CGGTTTGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGG-GTTTGGGTT), and 200 nmol/L Tel-2 primer (GGCTTGCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCC-T). The PCR reaction mixture (15 μL) for human globulin consists of 5 ng genomic DNA, 1 × SYBR Green Mastermix, 200 nmol/L Hgb-1 primer (GCTTCTGACACAACTGTGTTCACTAGC), and 200 nmol/L Hgb-2 primer (CACCAACTTCATCCACG-TTCACC). The thermal reactions are: 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15s and 56°C (for telomere amplification) or 58°C (for Hgb amplification) for 1 min. The PCR reaction for telomere and Hgb amplification were done in two separate 384 plates with the same arrangement of samples on plates. Each plate, besides samples, included negative and positive controls (3.9 Kb telomere and 1.2 Kb telomere from Roche Applied Science commercial telomere length assay kit), and a calibrator DNA. Each plate contained six 2-fold serially diluted reference DNA (from 20 to 0.625 ng) for a six-point standard curve. The acceptable standard deviation of Ct values was ≤ 0.25. Otherwise, the sample was repeated. The inter-assay variations were tested by two samples for three runs.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the Intercooled Stata 10 statistical software package (Stata, College Station, TX) and were two-sided. P value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant. To evaluate the effect of depressive symptoms, lifetime MDD, and telomere length on bladder cancer mortality, hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) were estimated by Cox proportional hazard regression for the overall analysis, and stratified analysis by stage. Patients who were lost to follow-up before the endpoint events (death, recurrence, and progression) were censored. Univariate Cox regression was performed to evaluate the association between outcomes with demographic, clinical variables, telomere length, and depression variables. Variables that were significantly associated with bladder cancer outcomes in univariate Cox regression were included in the multivariate Cox regression model.

The CES-D score was analyzed as both categorical (CES-D Scale ≥ 16 or <16) and continuous. Telomere length was also analyzed both as a continuous and categorical variable by median split and quartiles to assess dose-response trends. Further, in a sensitivity analysis, we used age as the time scale in the Cox proportional hazard regression and observed similar estimates for HRs and 95% CIs for the depressive symptoms, lifetime MDD, and telomere length (data not shown). The Kaplan-Meier plots and log rank tests were applied to compare the difference in event-free survival time by the dichotomized groups for current depressive symptoms, lifetime MDD, and telomere length, where appropriate. Median survival time of each group was estimated based on the Kaplan-Meier curve. Joint association of short telomere and depression measures was assessed by both multivariate Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier curves. Multivariate logistic regression was used to assess the association between telomere length and depression variables.

Mediation analyses were conducted using standard procedures (27) from multivariate regression analyses noted above. The criterion for mediation requires that the predictor variables (CES-D/MDD) are associated with telomere length and mortality; telomere length (mediator) is associated with mortality; and when both CES-D/MDD and telomere length are entered in the same model, the association between CES-D/MDD and mortality is decreased.

Results

Of the 464 bladder cancer patients enrolled (Table 1), 368 (79.3%) were male, and 432 (93.1%) were Caucasian. The mean age at diagnosis was 65 years. There were 234 (53.7%) patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) and 202 (46.3%) with muscle invasive and metastatic bladder cancer (MIBC). At follow-up, clinical data were available for 441 of the 464 patients enrolled. During the median follow up of 21.6 months, 88 patients died, 124 patients experienced recurrence, and 73 patients progressed from NMIBC to a more advanced stage.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Subjects | 464 | 100 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 64.87 | 10.99 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 368 | 79.31 |

| Female | 96 | 20.69 |

| Race | ||

| White | 432 | 93.1 |

| Hispanic | 15 | 3.23 |

| Black | 15 | 3.23 |

| Other | 2 | 0.44 |

| Smoking status* | ||

| Never | 133 | 28.66 |

| Former | 199 | 42.89 |

| Current | 132 | 28.45 |

| Pack years*, mean (SD) | 79.64 | 78.67 |

| Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer | ||

| No | 202 | 46.33 |

| Yes | 234 | 53.67 |

| Survival status | ||

| Alive | 353 | 80.05 |

| Dead | 88 | 19.95 |

| Recurrence | ||

| No | 317 | 71.88 |

| Yes | 124 | 28.12 |

| Progression | ||

| No | 366 | 83.37 |

| Yes | 73 | 16.63 |

Note: SD=Standard Deviation;

Never smoker=Individuals who never smoked or had smoked less than 100 cigarettes in his or her lifetime; Former smoker= Individuals who had quit smoking at least 1 year prior to diagnosis were defined as former smokers; Current smoker= Individuals who were currently smoking or who had stopped less than one year prior to diagnosis were defined as current smokers. Pack year of smoking was defined as number of cigarettes per day divided by 20 (20 cigarettes per pack) and then multiplied by years of smoking.

Primary Objectives

Relationship of depression to mortality

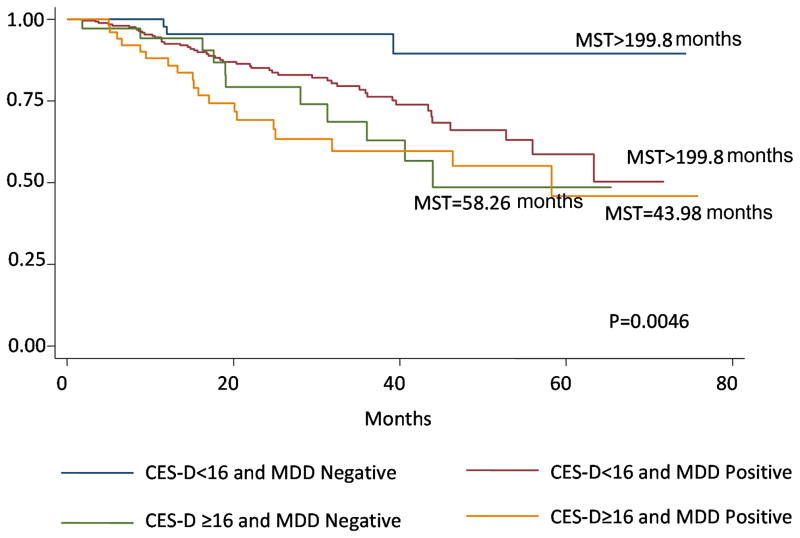

Age at cancer diagnosis, cancer stage, grade and treatment for MIBC were all significantly associated with overall survival (Table 2). The presence of current depressive symptoms (CES-D scores ≥ 16) was significantly associated with increased risk of bladder cancer mortality (HR=1.90; 95% CI=1.21 to 2.98; P= 0.005) (Table 2). The association between bladder cancer mortality and current depressive symptoms was also confirmed using CES-D as a continuous measure. However, lifetime MDD history alone was not significantly associated with bladder cancer survival (Table 2). In multivariate Cox regression analysis (Table 3), after adjusting for age, gender, ethnicity, smoking status, cancer stage, grade, and treatment regimens, patients with current depressive symptoms exhibited a 1.83-fold (95%CI=1.08 to 3.08; P=0.024) elevated mortality risk, and shorter median survival time, based on Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (58.26 months vs. greater than 200 months; P=0.004) (SI Figure 1), compared to those with CES-D scores < 16. Patients with lifetime MDD also showed increased mortality in multivariate analyses, although the association did not reach statistical significance (Table 3). In joint multivariate analysis of lifetime MDD and current depressive symptoms, patients with current depressive symptoms and lifetime MDD experienced 4.88-fold (95% CI=1.40 to 16.99; P=0.013) increased risk of mortality compared to those with CES-D scores < 16 and no lifetime MDD (Table 4). Patients with both forms of depression had significantly shorter median survival time (44 months vs. greater than 200 months; P=0.005) (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Association between demographic, clinical variables, depression, and mortality in bladder cancer patients in univariate Cox regression models

| Alive N (%) |

Dead N (%) |

Univariate HR (95% CI) |

P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 64.4(11.0) | 67.4(10.6) | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) | 0.003 |

| Smoking Pack Years | 38.4(27.3) | 43.0(32.4) | 1.01(0.998–1.02) | 0.129 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 275(79.71) | 70(20.29) | 1(reference) | |

| Female | 78(81.25) | 18(18.75) | 1.06(0.63–1.78) | 0.825 |

| Smoking status | 0.275* | |||

| Never | 110(82.09) | 24(17.91) | 1(reference) | |

| Former | 158(82.29) | 34(17.71) | 0.92(0.55–1.56) | 0.761 |

| Current | 85(73.91) | 30(26.09) | 1.38(0.80–2.37) | 0.248 |

| CES-D | ||||

| <16 | 280(84.08) | 53(15.92) | 1(reference) | |

| ≥16 | 63(67.74) | 30(32.26) | 1.90(1.21–2.98) | 0.005 |

| Continuous, mean (SD) | 9.05(8.30) | 13.18(9.54) | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | 0.001 |

| Lifetime MDD | ||||

| Negative | 79 (84.95) | 14 (15.05) | 1.0 (reference) | |

| Positive | 273 (78.89) | 73 (21.10) | 1.59 (0.90–2.82) | 0.112 |

| Stage | <0.0001* | |||

| 0a and 0is | 115(94.26) | 7(5.74) | 1(reference) | |

| I | 96(88.89) | 12(11.11) | 2.05(0.81–5.22) | 0.131 |

| II | 95(75.40) | 31(24.60) | 7.27(3.15–16.77) | <0.0001 |

| III | 19(59.38) | 13(40.63) | 10.42(4.11–26.43) | <0.0001 |

| IV | 18(46.15) | 21(53.85) | 18.44(7.73–44.01) | <0.0001 |

| Grade | ||||

| 1 and 2 | 84(92.31) | 7(7.69) | 1(reference) | |

| 3 | 256(77.81) | 73(22.19) | 3.52(1.62–7.67) | 0.002 |

| Treatment (for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer) | 0.484* | |||

| TUR only | 55(85.94) | 9(14.06) | 1(reference) | |

| Induction BCG | 59(89.39) | 7(10.61) | 0.81(0.29–2.24) | 0.679 |

| Maintenance BCG | 58(96.67) | 2(3.33) | 0.35(0.07–1.67) | 0.189 |

| Other treatment | 42(95.45) | 2(4.55) | 0.50(0.11–2.36) | 0.381 |

| Treatment (for muscle-invasive bladder cancer) | 0.0035* | |||

| Cystectomy | 34(70.83) | 14(29.17) | 1(reference) | |

| Cystectomy and chemotherapy | 48(73.85) | 17(26.15) | 1.07(0.53–2.18) | 0.85 |

| Chemotherapy | 12(48.00) | 13(52.00) | 3.89(1.81–8.38) | 0.001 |

| TUR only | 8(61.54) | 5(38.46) | 3.35(1.20–9.35) | 0.021 |

| Other | 34(66.67) | 17(33.33) | 1.52(0.75–3.10) | 0.244 |

Note: SD=Standard deviation; HR=Hazard Ratio; CI=Confidence Interval; MDD=Major Depressive Disorder; CES-D= Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Likelihood ratio p-value comparing the model with the variable and the model without the variable

Table 3.

Association between depression and mortality in bladder cancer patients in multivariate Cox regression analyses

| Alive, N(%) | Dead, N(%) | HR (95% CI)* | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CES-D | ||||

| <16 | 280(84.08) | 53(15.92) | 1(reference) | |

| ≥ 16 | 63(67.74) | 30(32.26) | 1.83(1.08–3.08) | 0.024 |

| Continuous, mean (SD) | 1.03(1.01–1.06) | 0.013 | ||

| Lifetime MDD | ||||

| Negative | 79(84.95) | 14(15.05) | 1(reference) | |

| Positive | 273(78.90) | 73(21.10) | 1.67(0.87–3.22) | 0.124 |

| Lifetime MDD and CES-D | ||||

| CES-D <16, MDD negative | 51(94.44) | 3(5.56) | 1(reference) | |

| CES-D <16, MDD positive | 228(82.01) | 50(17.99) | 2.36(0.71–7.81) | 0.160 |

| CES-D ≥ 16, MDD negative | 26(70.27) | 11(29.73) | 2.61(0.64–10.61) | 0.179 |

| CES-D ≥16, MDD positive | 37(66.07) | 19(33.93) | 4.88(1.40–16.99) | 0.013 |

Adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, smoking status, grade, treatments by stage

Note: HR=Hazard Ratio; CI=Confidence Interval; MDD=Major Depression Disorder; CES-D= Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Table 4.

Joint effect of depression variables and telomere length on mortality in bladder cancer patients in multivariate Cox regression analyses

| Alive, N(%) | Dead, N(%) | Adjusted HR (95% CI)* | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telomere and CES_D | ||||

| Long telomere and CES-D<16 | 102(83.61) | 20(16.39) | 1(reference) | |

| Short telomere and CES-D<16 | 103(83.06) | 21(16.94) | 0.96(0.49–1.88) | 0.9064 |

| Long telomere and CES-D≥16 | 29(74.36) | 10(25.64) | 1.16(0.50–2.70) | 0.7343 |

| Short telomere and CES-D≥16 | 19(55.88) | 15(44.12) | 3.96(1.86–8.41) | 0.0003 |

| Telomere and Lifetime MDD | ||||

| Long telomere and MDD negative | 33(82.50) | 7(17.50) | 1(reference) | |

| Short telomere and MDD negative | 25(89.29) | 3(10.71) | 1.36(0.31–5.93) | 0.6860 |

| Long telomere and MDD positive | 102(80.95) | 24(19.05) | 1.70(0.65–4.47) | 0.2834 |

| Short telomere and MDD positive | 103(74.64) | 35(25.36) | 2.24(0.88–5.75) | 0.0923 |

Adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, smoking status, grade and treatments by stage

Note: HR=Hazard Ratio; CI=Confidence Interval; MDD=Major Depression Disorder; CES-D= Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves by cross-classification of CES-D (≥16 vs.<16) and lifetime MDD (positive vs. negative). Differences among curves were tested by Log-Rank test with P-value shown. Note: CES-D=Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; MDD=Major Depression Disorder.

Relationship of telomere length to mortality

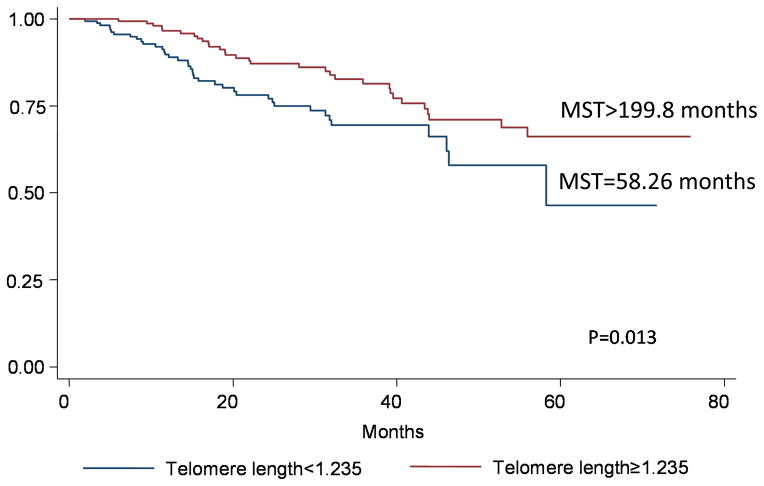

In univariate analyses, one unit increase in telomere length was associated with a significantly reduced risk of death (HR=0.39; 95% CI=0.20 to 0.78; P=0.007) (SI Table 1). When dichotomized by median, long telomere length was associated with a 45% reduction in mortality (HR=0.55; 95%CI=0.34 to 0.89; P=0.015) (SI Table 1). Reduced mortality was observed with long telomere length in quartile analyses suggesting a significant dose-response relationship between quartiles and mortality (P for trend=0.018 in quartile analysis) (SI Table 1). However, in multivariate models adjusting for age, gender, ethnicity, smoking status, tumor stage, grade and treatment, the associations were attenuated and did not reach statistical significance (SI Table 1). Kaplan-Meier survival curves for median split showed that median survival time was significantly shorter in patients with short versus long telomere lengths (58.26 months vs. greater than 200 months, P=0.013) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves by telomere length categories. Telomere length was categorized (long vs. short) by median split. Differences between curves were tested by Log-Rank test with P value shown. Note: MST=median survival time.

Relationship of telomere length and depression to recurrence/progression

In the subset of superficial bladder cancer patients, due to the small sample size and endpoint events, we combined recurrence and progression as one endpoint event. The recurrence/progression-free survival times did not differ significantly between subjects with short versus long telomere lengths. However, multivariate Cox regression analysis indicated that patients with a lifetime history of MDD had a 1.99 fold elevated risk for having a recurrence or progression of disease compared to those with no history of MDD (OR=1.99; 95% CI=1.14 to 3.47; P=0.016) (SI Table 2)

Secondary Objectives

Joint effect of depression and telomere length on mortality

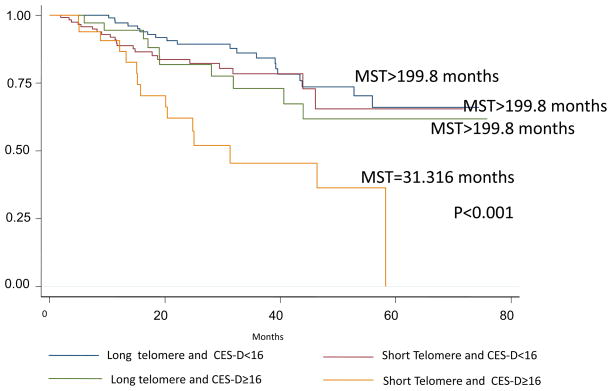

In joint analysis, patients with both short telomere length and CES-D scores ≥ 16 experienced a 3.96-fold (95%CI: 1.86 to 8.41; P=0.0003) increased mortality compared to patients with long telomeres and CES-D scores < 16 (Table 4), as well as shorter median survival time as compared to other groups (31 months vs. greater than 200 months, P<0.001) (Figure 3). A similar joint analysis of MDD history and telomere length on mortality was nonsignificant (Table 4). However, patients with lifetime MDD and short telomere length had significantly shorter median survival time than other groups (58.26 months vs. greater than 200 months; P=0.025) (SI Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves by cross-classification of CES-D (≥16 vs. <16) and telomere length (long vs. short). Telomere length was categorized (long vs. short) by median split. Differences between curves were tested by Log-Rank test with P value shown. Note: MST=median survival time; CES-D= Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Evaluation of telomere length as mediator

There were no direct associations between CES-D scores and telomere length (SI Table 3). However, in multivariate Cox regression analysis, history of lifetime MDD was associated with increased risk of having short telomere length (OR=1.85; 95% CI=1.03 to 3.32; P=0.039) (SI Table 3). Further, the mean telomere length was significantly shorter in patients with lifetime MDD than patients with no history of MDD (1.23 vs. 1.42, P=0.002). However, the criterion for meditational analyses did not support the hypothesis of telomere length as a mediator of the effects of CES-D scores or history of MDD on mortality.

Discussion

We found that current depressive symptoms were associated with increased bladder cancer mortality by almost two-fold and that current depressive symptoms and lifetime history of MDD further increased the risk to almost five fold. We did not, however, find evidence to support the hypothesis that telomere length mediated these effects. Our results did support a strong joint association of short telomere length and current depressive symptoms with mortality (3.96 fold).

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the association between depression and increased mortality risk in cancer patients (8, 28). The association may be due to symptom overlap between depressive symptoms and disease severity. However, previous meta-analyses have found depressive symptoms to be predictive of cancer mortality, independent of a number of clinical prognosticators including stage of disease, cancer site, performance status, treatment status and smoking (8, 9), as was the case in the current trial. The association may also be due to inequities in access to care for patients with depression which could result in lower receipt of appropriate cancer treatments following diagnosis (29, 30), although receipt of appropriate treatment was not found to mediate the relationship of psychiatric disorder and mortality risk in these studies (29, 30). Depressed individuals may be more likely to engage in behaviors that negatively impact health, including smoking and drinking alcohol in excess, overeating, engaging in low levels of physical activity, and poor sleep hygiene. In the current study, we found depression was associated with mortality, independent of smoking. Although data on these other behavioral factors was not available in the current study, other studies have shown that the effect of depression on mortality was attenuated after adjusting for these behavioral factors, but remained a significant predictor (31, 32).

Alternatively, depression may enhance cancer mortality via neuroendocrine and immunological mechanisms (28, 33). MDD is associated with abnormalities in stress related biological systems including the sympathetic nervous system, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA); and immune function, including increased circulating cortisol concentrations, inflammation, free radical production, and oxidative stress (12, 34), which could lead to immune response suppression to tumors. Increased concentrations of neutrophils and the expression of pro-inflammatory interleukins such as IL1, IL6, TNFα and other inflammatory factors (35), as well as an imbalance between Th1 and Th2 immune response have been found in depressed patients (35). Depression is associated with decreased activity of cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells, which may affect immune surveillance of tumors (28, 35). Dysfunctional immune surveillance could lead to the accumulation of somatic mutations, genome instability, tumorigenesis and progression of disease (35). Other cancer related events such as DNA damage, angiogenesis, cell growth and reactive oxygen species have also been linked to depression (35).

A significant finding of the current study is that patients with both depressive symptoms and short telomere length had a higher level of mortality risk. The neuroendocrine and immunological processes associated with depression, noted above, have also been found to be related to telomere length, telomerase activity (12) and tumor growth and progression (36). The joint association of depression and telomere length with mortality might suggest an additive effect of these depression-associated processes to other factors we found to be associated with telomere length including age and type of treatment in MIBC (chemotherapy and transurethral resection).

Although we found telomere length was associated with mortality in univariate analyses, the association was nonsignificant in multivariate analyses that adjusted for demographic and clinical variables. Our findings differ from those of multivariate analysis findings in a longitudinal population-based study of cancer-free individuals (19), and studies of recently diagnosed cancer patients (37, 38) that found telomere length was associated with cancer mortality. Discrepancies in findings may be due to differences in telomere length assessment methodology, tumor type and telomere length response to different types of cancer disease.

Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find depressive symptoms were associated with telomere length. However, we did find an inverse association between lifetime MDD and telomere length. A majority of studies examining the relationship between depressive episodes in MDD and bipolar disorder found shorter telomeres and a higher load of short telomeres in individuals with these disorders compared to nonpsychiatric controls (14–16, 39), and findings from several studies suggest that depressive chronicity may play an important role in the association between depression and telomere length. (14, 16) In contrast, a number of studies have failed to find an association between telomere length and severity of depressive symptoms assessed by self-report measures such as the CES-D (40, 41). Our results are consistent with these findings. It is important to note that studies examining the effects of chronic psychological stress on telomere length have also found a negative dose-response relationship of telomere length with increasing levels of stress and traumatic life events in adults and children (42–44), which could suggest that chronic exposure to the biological effects of psychological stress (12) may be a common mechanism underlying the association of telomere length and these various forms of stress exposure.

The current study is the first to assess the association between telomere length and bladder cancer outcomes. Results from previous studies examining the association between telomere length and cancer mortality were inconsistent by cancer type, with mortality in some cancers related to short telomere length (45), and long telomere length in other cancers (37, 38). However, results from most of these studies were based on small samples, and/or had limited control for confounding factors, potentially leading to unreliable risk estimates.

Cognitive behavioral, pharmacological, and combined treatment approaches have been found to be efficacious in the treatment of depressive symptoms, and should be considered in cancer patients with MDD or those who score high on measures of depressive symptoms. Moreover, telomere shortening has been linked to a number of modifiable environmental and lifestyle factors that contribute to disease risk and progression such as smoking, pollution, obesity (46, 47), and early and chronic life stress (44, 48). Higher engagement in healthy behaviors, including diet, exercise and sleep has been found to moderate, in a protective fashion, the effect of major life stressors on telomere attrition across a 1 year period in healthy, older women. In addition, there is preliminary evidence that interventions designed to impact diet, physical activity, stress and social support are associated with increases in telomerase activity and telomere length in low-risk prostate cancer patients.(49, 50) Additional research is needed on the effect of behavioral interventions on telomere attrition.

Current bladder cancer outcome prediction has largely relied on clinical parameters (3, 4, 51), which has resulted in low predictive power with appreciably different outcomes in patients with similar clinical characteristics. The current study strongly suggests that incorporating psychological risk factors into outcome models could provide additional and important information regarding predictors of risk. Depressive symptoms remained statistically significant in the model after adjusting for demographic and clinical variables, supporting depression as an independent predictor of mortality in bladder cancer patients. Because depression has biological effects, as previously discussed, incorporating depression into current prediction models may account for the effects of biological predictors that have not yet been identified or characterized.

There were several limitations in this study. Because of the observational nature of the study, a causal link between depression, telomere length, and survival cannot be established. However, the data are consistent with well controlled animal studies examining the role of stress in progression of disease (52). We used a measure of depressive symptoms rather than clinical diagnosis. Our measure of lifetime MDD was based on just two questions, and the measure we used has not yet been validated. However, it should be noted that a 2-item screen for current MDD that utilizes the same two cardinal questions, has been found to have high levels of sensitivity and specificity in cancer patients and other clinical populations.(53–56) Further, our measure of lifetime MDD did not provide information on whether participants were experiencing a current major depressive episode, level of symptom severity or the duration or number of previous major depressive episodes. This is an important limitation, given recent findings from a large, population based study, showing a dose-response association between severity and chronicity of symptoms and telomere length in individuals with current MDD, with the most severely disordered individuals having the shortest telomeres. However, this study also found individuals with remitted MDD to have significantly shorter telomeres than healthy controls, and no differences in telomere length in individuals with current versus remitted MDD.(57) Finally, depression was measured only once at study entry, thus the temporal relationship of depressive symptom changes to cancer outcomes could not be assessed.

This is the first prospective study investigating depressive symptoms, telomere length and mortality in a cohort of bladder cancer patients. We observed a joint association of depressive symptoms and short telomere length with all-cause mortality. Our findings have significant public health implications regarding the importance of intervening on depressive symptoms and utilizing behavioral interventions that may slow telomere attrition rate in cancer patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support

Research supported by the National Institutes of Health (U01 CA 127615 (X. Wu) and P50 CA 91846 (X. Wu and C.P. Dinney).

Footnotes

Previously presented at Eleventh Annual American Association for Cancer Research International Conference on Frontiers in Cancer Prevention Research, Anaheim, CA, 10/2012

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaufman DS, Shipley WU, Feldman AS. Bladder cancer. Lancet. 2009;374(9685):239–49. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porta N, Calle ML, Malats N, Gomez G. A dynamic model for the risk of bladder cancer progression. Stat Med. 2012;31(3):287–300. doi: 10.1002/sim.4433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bochner BH, Kattan MW, Vora KC. Postoperative nomogram predicting risk of recurrence after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(24):3967–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuijpers P, Smit F. Excess mortality in depression: a meta-analysis of community studies. J Affect Disord. 2002;72(3):227–36. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barth J, Schumacher M, Herrmann-Lingen C. Depression as a risk factor for mortality in patients with coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(6):802–13. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000146332.53619.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan A, Lucas M, Sun Q, van Dam RM, Franco OH, Willett WC, et al. Increased mortality risk in women with depression and diabetes mellitus. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(1):42–50. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Depression and cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40(11):1797–810. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Satin JR, Linden W, Phillips MJ. Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2009;115(22):5349–61. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giese-Davis J, Collie K, Rancourt KM, Neri E, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. Decrease in depression symptoms is associated with longer survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a secondary analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(4):413–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hjerl K, Andersen EW, Keiding N, Mouridsen HT, Mortensen PB, Jorgensen T. Depression as a prognostic factor for breast cancer mortality. Psychosomatics. 2003;44(1):24–30. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.44.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolkowitz OM, Epel ES, Reus VI, Mellon SH. Depression gets old fast: do stress and depression accelerate cell aging? Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(4):327–38. doi: 10.1002/da.20686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DePinho RA, Wong KK. The age of cancer: telomeres, checkpoints, and longevity. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(7):S9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elvsashagen T, Vera E, Boen E, Bratlie J, Andreassen OA, Josefsen D, et al. The load of short telomeres is increased and associated with lifetime number of depressive episodes in bipolar II disorder. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1–3):43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simon NM, Smoller JW, McNamara KL, Maser RS, Zalta AK, Pollack MH, et al. Telomere shortening and mood disorders: preliminary support for a chronic stress model of accelerated aging. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(5):432–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolkowitz OM, Mellon SH, Epel ES, Lin J, Dhabhar FS, Su Y, et al. Leukocyte telomere length in major depression: correlations with chronicity, inflammation and oxidative stress--preliminary findings. PloS one. 2011;6(3):e17837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludlow AT, Roth SM. Physical activity and telomere biology: exploring the link with aging-related disease prevention. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:790378. doi: 10.4061/2011/790378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma H, Zhou Z, Wei S, Liu Z, Pooley KA, Dunning AM, et al. Shortened telomere length is associated with increased risk of cancer: a meta-analysis. PloS one. 2011;6(6):e20466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willeit P, Willeit J, Mayr A, Weger S, Oberhollenzer F, Brandstatter A, et al. Telomere length and risk of incident cancer and cancer mortality. JAMA. 2010;304(1):69–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willeit P, Willeit J, Kloss-Brandstatter A, Kronenberg F, Kiechl S. Fifteen-year follow-up of association between telomere length and incident cancer and cancer mortality. JAMA. 2011;306(1):42–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu X, Lin J, Grossman HB, Huang M, Gu J, Etzel CJ, et al. Projecting individualized probabilities of developing bladder cancer in white individuals. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(31):4974–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.7557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Husaini BA, Neff JA, Harrington JB, Hughes MD, Stone RH. Depression in rural communities: Validating the CES-D scale. Journal of Community Psychology. 1980;8:20–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV-TR Disorders - Patient Edition (with psychotic screen) 2. New York, New York: New York Psychiatric Institute; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen M, Hildebrandt MA, Clague J, Kamat AM, Picornell A, Chang J, et al. Genetic variations in the sonic hedgehog pathway affect clinical outcomes in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3(10):1235–45. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(10):e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.10.e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–82. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spiegel D, Giese-Davis J. Depression and cancer: mechanisms and disease progression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):269–82. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00566-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baillargeon J, Kuo YF, Lin YL, Raji MA, Singh A, Goodwin JS. Effect of mental disorders on diagnosis, treatment, and survival of older adults with colon cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(7):1268–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodwin JS, Zhang DD, Ostir GV. Effect of depression on diagnosis, treatment, and survival of older women with breast cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(1):106–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.da Silva MA, Singh-Manoux A, Shipley MJ, Vahtera J, Brunner EJ, Ferrie JE, et al. Sleep duration and sleep disturbances partly explain the association between depressive symptoms and cardiovascular mortality: the Whitehall II cohort study. Journal of Sleep Research. 2014;23:94–7. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lawrence D, Kisely S, Pais J. The epidemiology of excess mortality in people with mental illness. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(12):752–60. doi: 10.1177/070674371005501202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reiche EM, Nunes SO, Morimoto HK. Stress, depression, the immune system, and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5(10):617–25. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01597-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK, Antoni MH. Host factors and cancer progression: biobehavioral signaling pathways and interventions. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(26):4094–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reiche EM, Morimoto HK, Nunes SM. Stress and depression-induced immune dysfunction: implications for the development and progression of cancer. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2005;17(6):515–27. doi: 10.1080/02646830500382102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi M, Liu D, Yang Z, Guo N. Central and peripheral nervous systems: master controllers in cancer metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2013;32(3–4):603–21. doi: 10.1007/s10555-013-9440-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Svenson U, Nordfjall K, Stegmayr B, Manjer J, Nilsson P, Tavelin B, et al. Breast cancer survival is associated with telomere length in peripheral blood cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68(10):3618–23. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Svenson U, Ljungberg B, Roos G. Telomere length in peripheral blood predicts survival in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69(7):2896–901. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hartmann N, Boehner M, Groenen F, Kalb R. Telomere length of patients with major depression is shortened but independent from therapy and severity of the disease. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(12):1111–6. doi: 10.1002/da.20749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaffer JA, Epel E, Kang MS, Ye S, Schwartz JE, Davidson KW, et al. Depressive symptoms are not associated with leukocyte telomere length: findings from the Nova Scotia Health Survey (NSHS95), a population-based study. PloS one. 2012;7(10):e48318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wikgren M, Maripuu M, Karlsson T, Nordfjall K, Bergdahl J, Hultdin J, et al. Short telomeres in depression and the general population are associated with a hypocortisolemic state. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71(4):294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Gouin JP, Weng NP, Malarkey WB, Beversdorf DQ, Glaser R. Childhood adversity heightens the impact of later-life caregiving stress on telomere length and inflammation. Psychosom Med. 2011;73(1):16–22. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820573b6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shalev I, Moffitt TE, Sugden K, Williams B, Houts RM, Danese A, et al. Exposure to violence during childhood is associated with telomere erosion from 5 to 10 years of age: a longitudinal study. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(5):576–81. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Surtees PG, Wainwright NW, Pooley KA, Luben RN, Khaw KT, Easton DF, et al. Life stress, emotional health, and mean telomere length in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer (EPIC)-Norfolk population study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(11):1152–62. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rossi D, Lobetti BC, Genuardi E, Monitillo L, Drandi D, Cerri M, et al. Telomere length is an independent predictor of survival, treatment requirement and Richter’s syndrome transformation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23(6):1062–72. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoxha M, Dioni L, Bonzini M, Pesatori AC, Fustinoni S, Cavallo D, et al. Association between leukocyte telomere shortening and exposure to traffic pollution: a cross-sectional study on traffic officers and indoor office workers. Environ Health. 2009;8:41. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-8-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valdes AM, Andrew T, Gardner JP, Kimura M, Oelsner E, Cherkas LF, et al. Obesity, cigarette smoking, and telomere length in women. Lancet. 2005;366(9486):662–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66630-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Damjanovic AK, Yang Y, Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Nguyen H, Laskowski B, et al. Accelerated telomere erosion is associated with a declining immune function of caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Immunol. 2007;179(6):4249–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ornish D, Lin J, Daubenmier J, Weidner G, Epel E, Kemp C, et al. Increased telomerase activity and comprehensive lifestyle changes: a pilot study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(11):1048–57. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ornish D, Lin J, Chan JM, Epel E, Kemp C, Weidner G, et al. Effect of comprehensive lifestyle changes on telomerase activity and telomere length in men with biopsy-proven low-risk prostate cancer: 5-year follow-up of a descriptive pilot study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(11):1112–20. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70366-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Youssef RF, Lotan Y. Predictors of outcome of non-muscle-invasive and muscle-invasive bladder cancer. ScientificWorldJournal. 2011;11:369–81. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2011.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Antoni MH, Lutgendorf SK, Cole SW, Dhabhar FS, Sephton SE, McDonald PG, et al. The influence of bio-behavioural factors on tumour biology: pathways and mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(3):240–8. doi: 10.1038/nrc1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–92. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mohr DC, Hart SL, Julian L, Tasch ES. Screening for depression among patients with multiple sclerosis: two questions may be enough. Mult Scler. 2007;13(2):215–9. doi: 10.1177/1352458506070926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ryan DA, Gallagher P, Wright S, Cassidy EM. Sensitivity and specificity of the Distress Thermometer and a two-item depression screen (Patient Health Questionnaire-2) with a ‘help’ question for psychological distress and psychiatric morbidity in patients with advanced cancer. Psychooncology. 2012;21(12):1275–84. doi: 10.1002/pon.2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(7):439–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Verhoeven JE, Revesz D, Epel ES, Lin J, Wolkwitz OM, Penninx BW. Major depressive disorder and accelerated cellular aging: results from a large psychiatric cohort study. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(8):895–901. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.