Abstract

Reprogramming of a gene’s expression pattern by acquisition and loss of sequences recognized by specific regulatory RNA binding proteins may be a major mechanism in the evolution of biological regulatory programs. We identified that RNA targets of Puf3 orthologs have been conserved over 100–500 million years of evolution in five eukaryotic lineages. Focusing on Puf proteins and their targets across 80 fungi, we constructed a parsimonious model for their evolutionary history. This model entails extensive and coordinated changes in the Puf targets as well as changes in the number of Puf genes and alterations of RNA binding specificity including that: 1) Binding of Puf3 to more than 200 RNAs whose protein products are predominantly involved in the production and organization of mitochondrial complexes predates the origin of budding yeasts and filamentous fungi and was maintained for 500 million years, throughout the evolution of budding yeast. 2) In filamentous fungi, remarkably, more than 150 of the ancestral Puf3 targets were gained by Puf4, with one lineage maintaining both Puf3 and Puf4 as regulators and a sister lineage losing Puf3 as a regulator of these RNAs. The decrease in gene expression of these mRNAs upon deletion of Puf4 in filamentous fungi (N. crassa) in contrast to the increase upon Puf3 deletion in budding yeast (S. cerevisiae) suggests that the output of the RNA regulatory network is different with Puf4 in filamentous fungi than with Puf3 in budding yeast. 3) The coregulated Puf4 target set in filamentous fungi expanded to include mitochondrial genes involved in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and other nuclear-encoded RNAs with mitochondrial function not bound by Puf3 in budding yeast, observations that provide additional evidence for substantial rewiring of post-transcriptional regulation. 4) Puf3 also expanded and diversified its targets in filamentous fungi, gaining interactions with the mRNAs encoding the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) complex I as well as hundreds of other mRNAs with nonmitochondrial functions. The many concerted and conserved changes in the RNA targets of Puf proteins strongly support an extensive role of RNA binding proteins in coordinating gene expression, as originally proposed by Keene. Rewiring of Puf-coordinated mRNA targets and transcriptional control of the same genes occurred at different points in evolution, suggesting that there have been distinct adaptations via RNA binding proteins and transcription factors. The changes in Puf targets and in the Puf proteins indicate an integral involvement of RNA binding proteins and their RNA targets in the adaptation, reprogramming, and function of gene expression.

A map of the evolutionary history of Puf proteins and their RNA targets shows that reprogramming of global gene expression programs via adaptive mutations that affect protein-RNA interactions is an important source of biological diversity.

Author Summary

We set out to trace the evolutionary history of an RNA binding protein and how its interactions with targets change over evolution. Identifying this natural history is a step toward understanding the critical differences between organisms and how gene expression programs are rewired during evolution. Using bioinformatics and experimental approaches, we broadly surveyed the evolution of binding targets of a particular family of RNA binding proteins—the Puf proteins, whose protein sequences and target RNA sequences are relatively well-characterized—across 99 eukaryotic species. We found five groups of species in which targets have been conserved for at least 100 million years and then took advantage of genome sequences from a large number of fungal species to deeply investigate the conservation and changes in Puf proteins and their RNA targets. Our analyses identified multiple and extensive reconfigurations during the natural history of fungi and suggest that RNA binding proteins and their RNA targets are profoundly involved in evolutionary reprogramming of gene expression and help define distinct programs unique to each organism. Continuing to uncover the natural history of RNA binding proteins and their interactions will provide a unique window into the gene expression programs of present day species and point to new ways to engineer gene expression programs.

Introduction

The phenotypic diversity of life on earth results not only from differences in the proteins encoded by each genome but, perhaps even more, from differences in the programs that specify where, when, under what conditions, and at what levels these proteins are expressed. A grand challenge in biology is to understand these gene expression programs. Uncovering the similarities in and differences between gene expression programs in related organisms can help reveal fundamental properties of these programs, how they have evolved, how they may be wired and rewired, and ultimately how they can be engineered.

The seminal step in gene expression and the focus of much current effort is the initiation of transcription through transcription factors that bind in proximity to genes and regulate the timing and magnitude of RNA synthesis (see [1–7] for reviews). Each transcription factor regulates a set of genes, numbering a few to thousands, specified by short DNA sequences that are in proximity to those genes and are recognized by that transcription factor. One major mechanism for diversification of gene expression programs is the loss or gain of regulation by individual transcription factors, due to mutations that, respectively, disrupt or create the proximal recognition sequences (see [8–13] for reviews). The binding specificity, regulation, and targets of a transcription factor tend to be conserved over a short evolutionary timescale, but each of these properties has changed over evolution, allowing the regulatory roles of orthologous transcription factors to diverge and diversify.

Evolutionary changes in regulation at the next level of gene expression are virtually unexplored. After transcription, each messenger RNA (mRNA) undergoes a functional odyssey and can be regulated at steps that include splicing, transport, localization, translation, and decay [14]. RNA binding proteins function in each step, and each mRNA interacts with many RNA binding proteins over its lifetime [15–22]. Each RNA binding protein can recognize a few to thousands of mRNAs, and the target sets of each individual RNA binding protein often share functional themes, encoding proteins involved in a particular biological process or localized to the same part of the cell [15,23–37]. These effects can be described in terms of a model originally referred to as the “RNA operon” model in which RNA binding proteins bind to and coordinate the regulation of mRNAs encoding functionally or cytotopically related proteins [18,20,21].

We set out to trace the evolutionary history of an RNA binding protein and how its interactions with targets change over evolution. Identifying this natural history is a step toward understanding the critical differences between organisms, how evolution has progressed, why these differences have arisen, and how gene expression programs are “wired.”

We chose to investigate the Puf (Pumilio–Fem-3-binding factor) family of RNA binding proteins, taking particular advantage of the relatively well-understood relationship between Puf protein sequences and the specific RNA sequences they recognize (Fig 1). Puf proteins are found in most, if not all, eukaryotes [38–40] and have been implicated in regulating the decay, translation, and localization of distinct sets of functionally related RNA targets [38,41–43]. For example, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Puf3 binds and regulates hundreds of distinct RNAs transcribed from the nuclear genome that, almost without exception, encode for proteins localized to the mitochondrion [25]. Puf3 promotes localization of its target mRNAs to the periphery of mitochondria [44–46] and can repress the expression of these mRNAs by promoting their decay [25,47,48]. Puf3 recognizes a specific sequence element usually found in the 3' untranslated region (3' UTR) of its targets (Fig 1) [25].

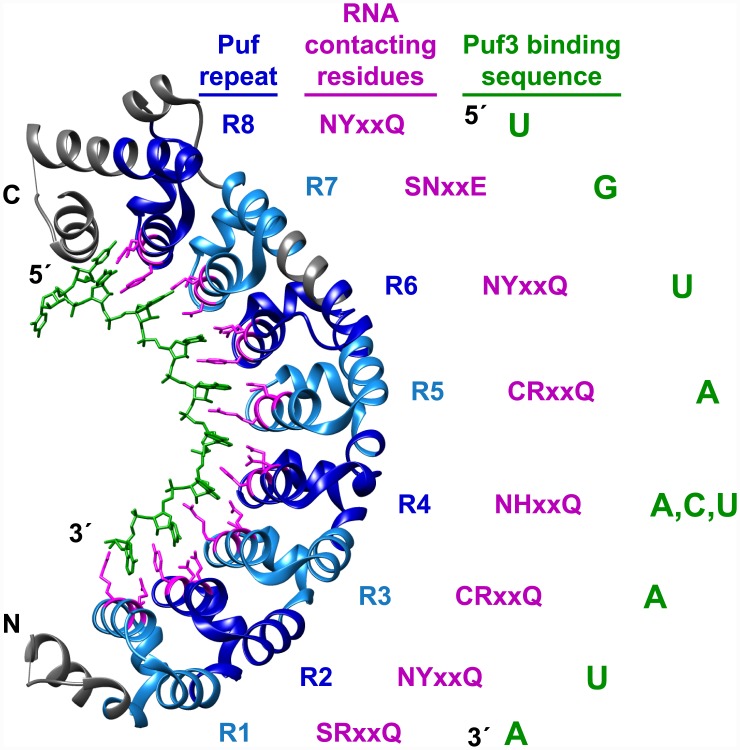

Fig 1. Puf3 recognition of RNA.

S. cerevisiae Puf3 structure displayed as a ribbon model from PDB (Protein Data Bank) entry 3k49 [49]. The RNA molecule with sequence CCUGUAAAUA is indicated in green. Puf repeats are highlighted in alternating light and dark blue. The Puf proteins with the same RNA-base-contacting amino acids as Puf3 (pink) that have been studied have a conserved RNA binding specificity [24,25,27,29,50,51]; the Puf proteins with different RNA-base-contacting amino acids have different RNA binding specificities [25,31,51–55]. The conserved RNA binding sequence is eight nucleotides, containing UGUA at the 5' end, flexibility for A, C, or U at the 5th position, and AUA at the 3' end. Mutating the RNA-interacting amino acids alters RNA binding specificity and can be done to make predictable changes in sequence specificity [51,56–59]. S. cerevisiae Puf3 contains additional residues that contact a nucleotide upstream of the core binding sequence, but these interactions are not conserved across eukaryotes.

S. cerevisiae Puf3 and its orthologs in Drosophila melanogaster (Pumilio) and Homo sapiens (Pum1 and Pum2) recognize nearly identical RNA sequence motifs, but they bind to distinct sets of mRNAs that encode proteins with distinct functional themes [24,25,27,29]. Fewer than 20% of the targets of the Puf3 orthologs in humans and flies are themselves orthologs [24,29], and the functional themes of their mRNA targets in flies and humans starkly contrast with those for yeast Puf3 [24,27,29]. Thus, the mRNA targets of Puf3 orthologs have diverged since humans, flies, and yeast shared ancestors. Nevertheless, bioinformatics studies have suggested that Puf targets are conserved over short timescales, underscoring the importance of these distinct interactions [60–65].

We first systematically investigated the conservation and divergence of the RNA targets that are likely to be recognized by orthologs of S. cerevisiae Puf3 in diverse eukaryotes. We then focused in detail on the larger family of Puf RNA binding proteins and their RNA targets in fungi, as the many sequenced fungal genomes provide the power to identify major and minor evolutionary changes in the repertoires of Puf proteins, their binding specificities, and their RNA targets. The numerous and often concerted changes in this single family of proteins and their RNA targets provide strong corroborative evidence for the role of coordinated protein binding to sets of related mRNAs in organizing gene expression [18,20,21]. The observed extensive evolutionary changes suggest that changes in RNA binding proteins and their interacting mRNAs are an important source of biological diversification and specialization; studies of these changes across evolutionary time may provide a powerful complement to traditional deep investigations of specific model organisms.

Results and Discussion

Evolutionary Interplay between Puf3 and Its RNA Targets

We searched for orthologs of S. cerevisiae Puf3 in 99 diverse eukaryotes (S1 Text, S1 Fig, S1 Table, Materials and Methods) and used the identified orthologs to determine the conservation of features important for RNA binding specificity. Puf3 is a canonical Puf protein containing eight Puf repeats [39,40,66,67] that together fold to form a characteristic crescent shape with an RNA binding interface on the inner side (Fig 1) [54,55,59,68–73]. Three amino acid residues within each Puf repeat typically contact an RNA base directly and are important determinants of RNA binding specificity (Fig 1 legend and references [49,54,55,59,68–73]).

The observations that Puf3 orthologs have a distinctly conserved pocket around the bound RNA and that the residues that determine RNA binding specificity are especially conserved suggest that orthologs of Puf3 recognize the same RNA sequence motifs (S2 Text, S2 Fig). This inference is consistent with experimental results from Puf3 orthologs in diverse eukaryotes [24,25,27,29,50,51]. We used this insight to infer, by analysis of RNA sequences, the extent to which the RNA targets of Puf3 are conserved.

RNA target sets of Puf3 orthologs are distinct and conserved in five eukaryotic lineages

We investigated the conservation and divergence in the sets of orthologous RNA recognized by Puf3 orthologs in diverse eukaryotes by evaluating the frequency with which orthologous RNAs contained a 3' UTR sequence that is recognized by the Puf3 protein family (i.e., UGUA[ACU]AUA). When a larger than expected fraction of the orthologous transcripts contained Puf3 recognition elements, relative to a null model (see Materials and Methods), we inferred that those targets were conserved from a common ancestor.

To measure the conservation of targets between each pair of 99 eukaryote species, we applied a network-level approach similar to that implemented by the program Fastcompare [63,74,75]. We first determined orthologous sequence sets for each pair of species and then determined the number of ortholog pairs that both contained a putative Puf3 binding site. This number was then compared to the number expected by chance, given the frequency of sequences with putative Puf3 binding sites in each species (using the hypergeometric test, Materials and Methods). To control for the extent of sequence similarity expected for each set of two species, the result with the Puf3 motif was compared to results from all permutations of this motif under a model that the permutated motifs are neutral with respect to natural selection (S3 Fig).

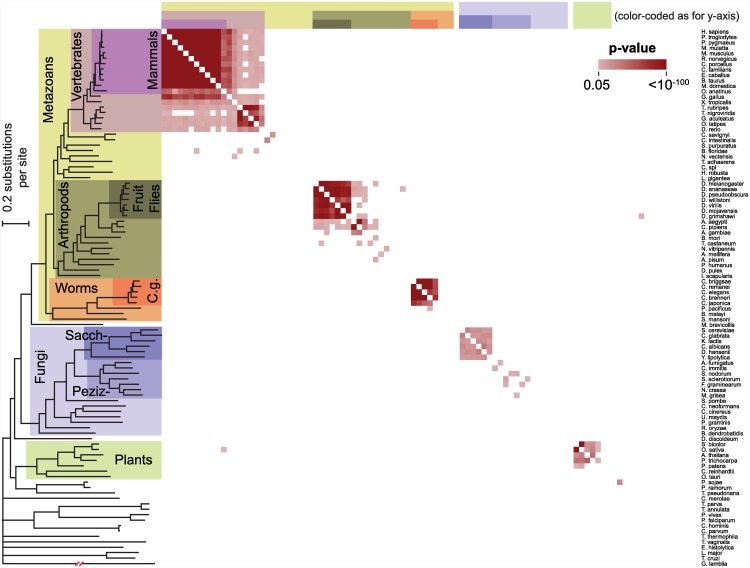

We found evidence for conservation of Puf3 targets within each of five taxonomic groups (Fig 2): (1) vertebrates; (2) fruit flies and mosquitoes; (3) Caenorhabditis worms; (4) budding yeasts of Saccharomycotina; (5) and land plants. The most recent common ancestor of each of these five groups lived approximately 500, 250, 100, 300, and 470 million years ago, respectively [76–79].

Fig 2. Conservation of Puf3 RNA targets across eukaryotes.

A heatmap displaying whether the Puf3 binding sequence UGUA[ACU]AUA is shared by orthologs in a pair of species. A significant p-value is displayed as a colored square and was determined by the hypergeometric test. Color is used only if the Puf3 motif ranks in the top 1% relative to all motif permutations (Materials and Methods). (The heatmap is not fully symmetrical since the orthology assignments are not necessarily reciprocal.) The phylogeny shown was inferred using a maximum-likelihood approach from a concatenated alignment of 53 protein sequences (Materials and Methods). "Sacch-" refers to Saccharomycotina fungi, "Peziz-" to Pezizomycotina fungi, and "C.g." to the Caenorhabditis genus of worms. The break noted in red corresponds to 0.5 substitutions per site in the branch to Giardia lamblia. p-Values and ranks of the Puf3 motif against its permutations can be found in S9 Dataset.

Despite evidence for conservation within the five groups noted above, we found no evidence for conservation of the Puf3 regulatory program or a subset of that program between any pair of the five groups (Fig 2). No pairwise comparisons between the groups were statistically significant.

The common ancestor of all of these groups presumably had a Puf3 protein and a single set of RNA targets. These findings suggest divergence of the Puf3-mediated regulatory programs prior to establishment of the five lineages, despite the strong conservation of Puf3’s RNA-sequence specificity. The subsequent conservation of distinct targets within lineages strongly suggests significant selective pressure operating to maintain Puf3’s interactions and thus its regulatory roles and provides additional evidence for distinct roles of Puf3 orthologs in different organisms and lineages. In addition, our estimates of the timing of major changes in Puf3's RNA targets can be compared to the inferred timing of changes in other aspects of the gene expression programs to better understand the changes in gene regulation through evolution and the interplay of gene regulatory elements in the gene expression programs unique to each species.

Puf Proteins and Their RNA Targets in Fungi

The diversity of the fungal kingdom is a result of more than one billion years of evolution [77], and the many available sequenced genomes and their relatively low complexity render fungi accessible and powerful for evolutionary studies. Here we synthesize the sequence data with biochemical and functional data to build a model of the evolution of Puf proteins and their targets in fungi.

Evolutionary reprogramming of post-transcriptional regulation: concerted changes in Puf3 targets

Puf3 in fungi provides a starting point for dissecting how target sets of an RNA binding protein diversify over evolution. As noted above, the S. cerevisiae Puf3 protein binds to more than 200 mRNAs [25], nearly all of which encode proteins that function in the mitochondrion and in particular act in mitochondrial organization, biogenesis, and translation [25,44]. We and others have noted a general conservation of these Puf3 targets in Saccharomycotina (Fig 2) [62,64]. The analysis in the preceding section suggested that the predicted Puf3 targets in the sister Pezizomycotina lineage do not share a detectable similarity with the Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets for the species studied (Fig 2), as did a previous less extensive analysis [60]. A more detailed analysis (below) leads us to a model for the nature and timing of these and other evolutionary changes.

Puf3 orthologs in Saccharomycotina and early-diverging Pezizomycotina species bind a common set of RNAs

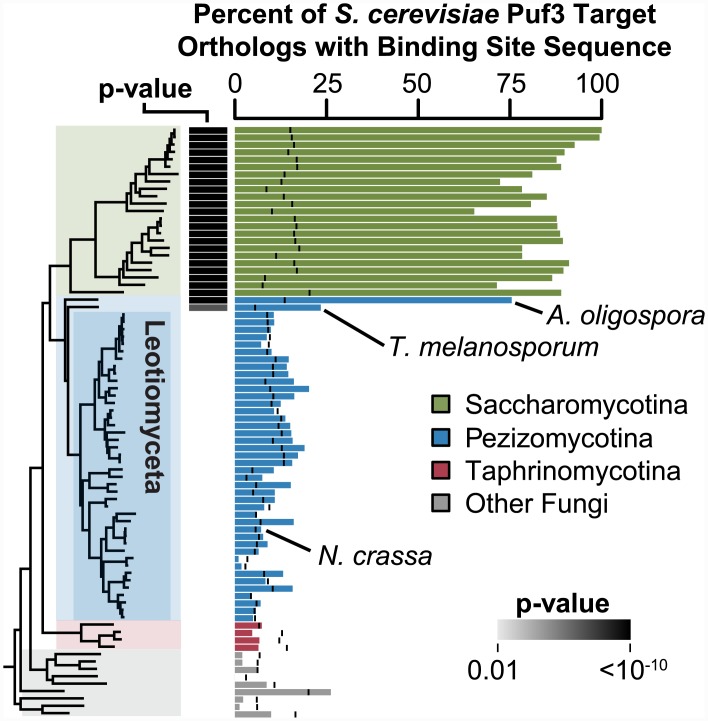

We sought to identify which fungi have a Puf3 protein that binds mRNA targets orthologous to the mRNA targets of S. cerevisiae Puf3, using sequence data from 80 fungi, including 23 from Saccharomycotina, 44 from Pezizomycotina, and 13 from other fungi (Materials and Methods). Of the 210 S. cerevisiae Puf3 mRNA targets identified experimentally [25], 176 (84%) contain a match to the Puf3 motif in the 500 nucleotides downstream of the stop codon, which presumably includes all or nearly all of the 3’ UTR [80]. We tracked conservation of Puf3 binding to RNAs orthologous to these 176 S. cerevisiae Puf3 targets, using the Puf3 motif as the insignia of Puf3 binding targets and the same operational definition of 3’ UTRs (Fig 3). Matches to the Puf3 motif are also found, albeit rarely, in the 3' UTRs of mRNAs not experimentally identified as Puf3 targets. To control for the background frequency of the presumptive Puf3 binding site in nontarget RNAs, we tested whether the enrichment of Puf3 motif matches in orthologs of Puf3 targets exceeded their overall frequency in all 3' UTRs for that species (Fig 3). In all species in the Saccharomycotina subphylum, matches to the motif recognized by Puf3 are enriched in orthologs of S. cerevisiae Puf3 targets (p < 10−50, Fig 3), consistent with our results above and with previous results that traced the conservation of Puf3 targets to the ancestor of Saccharomycotina [62,64].

Fig 3. Conservation of S. cerevisiae Puf3 targets in other fungi.

The percent of orthologs of S. cerevisiae Puf3 targets (identified by Gerber et al. [25]) that have a match to the Puf3 motif UGUA[ACU]AUA in the 3' UTRs in each species is shown as a bar plot. A black vertical bar marks the background frequency of the Puf3 motif for each species. The 3' UTR was defined as the 500 nucleotides downstream of the stop codon. Only orthologs of S. cerevisiae Puf3 targets that have a Puf3 motif match in 3' UTR were used (n = 176) so that S. cerevisiae S288C is set at 100%. A significant p-value (gray or black box) indicates that Puf3 motif matches are enriched in orthologs of S. cerevisiae Puf3 targets relative to all other orthologs. p-Values were computed using Fisher's exact test and are Bonferroni corrected for multiple hypothesis testing by multiplication by 80, the number of species tested. The phylogeny represents the evolutionary relationships of the fungi, inferred with a maximum-likelihood approach from a concatenated alignment of 20 protein sequences (Materials and Methods). Species names can be found in S19 Fig Percentages and p-values can be found in S1 Dataset.

These comparisons also identified two species from the neighboring Pezizomycotina subphylum in which the Puf3 recognition element was significantly enriched in the orthologs of S. cerevisiae Puf3 targets (Fig 3, p = 10−42 and 10−7). Arthrobotrys oligospora and Tuber melanosporum were the earliest to diverge from the remainder of the Pezizomycotina species analyzed herein (hereafter Leotiomyceta; see S19 Fig for phylogeny with species names).

The phylogenetic relationships of these fungi suggest a parsimonious evolutionary model in which the regulatory program embodied by Puf3 and its RNA targets in S. cerevisiae has been conserved since the Saccharomycotina and Pezizomycotina fungi diverged from their common ancestor, which is estimated to have occurred 500 million years ago [77,78,81]. Our results provide strong evidence that the regulation of mitochondrial protein transcripts by Puf3 is not unique to Saccharomycotina, in contrast to the conclusion from previous work [62]. As described below (see “Evolutionary Transition of the Regulation of a Large Set of Mitochondria-Related Genes from Puf3 to Puf4"), analysis of additional early-diverging Pezizomycotina species provided further evidence for this timing and additional insight into this apparent regulatory reprogramming. An alternative parsimonious model is discussed in S14 Text.

Leotiomyceta Puf3 shares a conserved binding specificity with S. cerevisiae Puf3 but interacts with a functionally distinct set of RNAs

The RNAs with putative Puf3 binding sites in the remaining 42 Leotiomyceta species (i.e., the Pezizomycotina species other than A. oligospora and T. melanosporum) have little in common with the Puf3 targets in S. cerevisiae (Fig 3). Two models could explain this divergence: Leotiomyceta Puf3 proteins changed their RNA sequence specificity and maintain the same targets as S. cerevisiae Puf3, or the Leotiomyceta Puf3 proteins retained their RNA sequence specificity but the sequences recognized by Puf3 were lost in the original RNA targets and acquired by a distinct new set of RNAs.

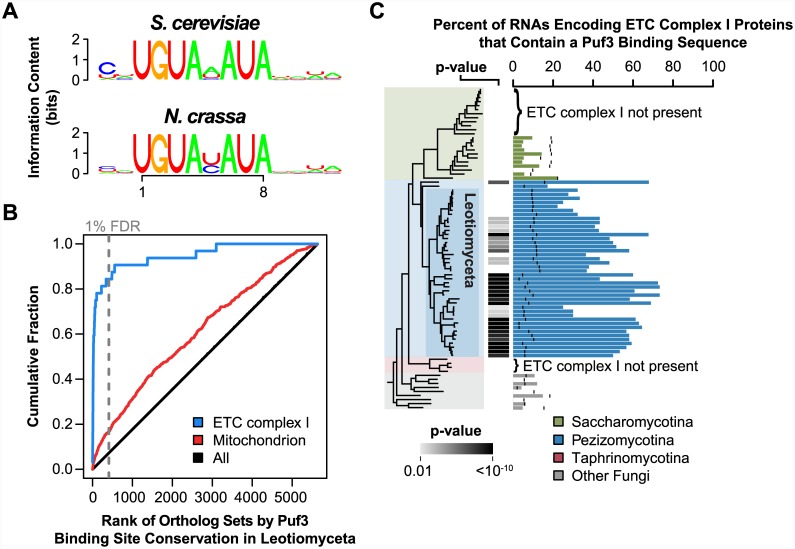

The conservation of the critical RNA recognition residues in Puf3 proteins from all eukaryotes, described above (S2 Fig, S2 Text), including the extended set of 80 fungi that we have analyzed in greater depth (S5 Fig), argues against the first model in which Puf3 proteins in the Leotiomyceta have evolved a novel sequence specificity. Nevertheless, we tested this model by experimentally determining the binding specificity of Puf3 from the Pezizomycotina species Neurospora crassa. We ectopically expressed N. crassa Puf3 protein fused to a tandem affinity purification tag (TAP-tag) in a S. cerevisiae strain missing endogenous Puf proteins, Puf1-5 (derived from 5Δpufs strain [47]), and we identified the RNAs bound by N. crassa Puf3 (Materials and Methods). Sequence analysis of the RNAs associated with N. crassa Puf3 identified a uniquely enriched motif strongly matching the eight-nucleotide motif preferred by S. cerevisiae Puf3 (Fig 4A, S6 Fig, S3 Text). Outside of this core eight-nucleotide motif, the N. crassa Puf3 motif lacks the modest preference of S. cerevisiae Puf3 for a cytosine residue two nucleotides upstream of the UGUA [25,49]. Comparative analysis of the conserved Puf3 targets in Saccharomycotina suggests that this preference was acquired within the Saccharomycotina lineage (S7 Fig), possibly to reduce competition with other Puf proteins (see S16 Text).

Fig 4. Binding specificity and targets of Leotiomyceta Puf3.

(A) Motifs identified by the motif discovery program FIRE [82] within the 3' UTRs of S. cerevisiae mRNAs associated with S. cerevisiae Puf3 or the ectopically expressed N. crassa Puf3. FIRE identified eight nucleotide motifs, and these motifs were extended to display any preferences for flanking nucleotides. A match to the Puf3 motif UGUA[ACU]AUA is found in the 3' UTRs of 241 out of 392 (61%) of S. cerevisiae Puf3 targets and 83 out of 250 (33%) of mRNAs associated with N. crassa Puf3. The motif frequency across all 3' UTRs is 11%. Position frequency matrices can be found in S5 Dataset. (B) Cumulative distributions based on the ranked conservation score for Puf3 sites across Leotiomyceta species. The gray dashed line represents the 1% false discovery rate (FDR) cutoff for ortholog sets within which Puf3 sites are considered conserved. N. crassa annotations were used to define mitochondrion and electron transport chain (ETC) complex I groups [83]. Annotations and conservation scores can be found in S7 Dataset. (C) The percent of 3' UTRs of transcripts encoding components of ETC complex I that have a Puf3 binding site sequence. A black vertical bar marks the background frequency of the Puf3 motif for each species. A significant p-value indicates that Puf3 motif matches are enriched in complex I encoding RNAs relative to all other transcripts. The p-value was computed using Fisher's exact test and is corrected for multiple hypothesis testing. The multi-subunit, transmembrane complex I was independently lost in several fungal lineages, and species lacking this complex are noted. Percentages and p-values can be found in S1 Dataset.

As the Saccharomycotina Puf3 target orthologs in Leotiomyceta species lack the canonical Puf3 recognition element (Fig 3) and Puf3 in Leotiomyceta has maintained its sequence specificity (Fig 4), Leotiomyceta Puf3 proteins then presumably recognize a different set or sets of RNAs that acquired the Puf3 recognition sequence through evolution. In the following section we describe these putative Leotiomyceta Puf3 targets.

RNA targets of Leotiomyceta Puf3 are involved in distinct mitochondrial and non-mitochondrial functions

We used sequence comparisons and conservation in 42 Leotiomyceta species to infer the RNAs that are bound by Leotiomyceta Puf3 proteins. First, we had to identify orthologous sets of Leotiomyceta genes. We anchored this search with the N. crassa genome because it is the most thoroughly annotated among the Leotiomyceta genomes. To do this we carried out pairwise sequence comparisons between N. crassa and each of the other genomes to identify orthologous genes (i.e., each N. crassa protein and its orthologs across the other Leotiomyceta species). We then searched the 3' UTRs of each orthologous gene set for matches to the Puf3 motif UGUA[ACU]AUA, defining a score for Puf3 binding site conservation that reflects the prevalence of 3' UTRs with Puf3 binding sites and accounts for the relatedness of the species (Materials and Methods). A false discovery rate (FDR) for each ortholog set was obtained from the rank of its calculated conservation score relative to the conservation scores from 100 permuted Puf3 motifs. For comparison, we also identified a set of conserved Puf3 targets in Saccharomycotina fungi defined relative to S. cerevisiae RNAs, and we refer to this set as Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets or ancestral Puf3 targets (n = 276, ≤1% FDR; S4 Text provides further discussion and additional evidence that members of this conserved target set that were not identified as targets experimentally are indeed Puf3 targets).

Puf3 recognition sites were significantly conserved (≤1% FDR) in the 3' UTRs of 409 ortholog sets in the Leotiomyceta species. The identity and functional themes in this set of putative Leotiomyceta Puf3 targets have multiple and profound differences relative to the Puf3 targets in Saccharomycotina. Whereas the vast majority of Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets have mitochondrial functions (256 of 276 targets, 93%), only about one-fourth of the conserved Puf3 target RNAs in Leotiomyceta encode mitochondrial proteins (113 targets, according to N. crassa annotation from [83]). Thus, the Leotiomyceta have nearly 300 inferred Puf3 targets that function in non-mitochondrial processes, in contrast to the near universal mitochondrial annotation of the Saccharomycotina targets. Furthermore, although enrichment of RNAs with mitochondrial functions among the Leotiomyceta Puf3 targets was highly significant (Fig 4B, odds-ratio = 3.9, p = 10−25 by Fisher's exact test), and the overlap with Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets was also significant (13%, odds-ratio = 3.2, p = 10−6 by Fisher's exact test), the Leotiomyceta Puf3 target set included only 26 of the 202 Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets that have orthologs in N. crassa and included 87 mitochondrial targets not observed in Saccharomycotina.

To understand the distinctions between mitochondrial targets of Puf3 in Leotiomyceta and Saccharomycotina, we determined within which of the 36 functional categories of mitochondrial genes [83] the Leotiomyceta Puf3 mRNA targets fall. We found remarkable enrichment for components of a particular mitochondrial protein complex, the ETC complex I; 27 of the 33 RNAs encoding ETC complex I subunits contained conserved Puf3 binding sequences (Fig 4B, odds-ratio = 107, p = 10−30 by Fisher's exact test). The frequency with which Puf3 binding sites were found in ETC complex I RNAs was significantly enriched in 33 out of 44 Pezizomycotina species, including the "basal" species A. oligospora (Fig 4C). In the remaining 11 species, Puf3 sites still occurred more frequently than expected by chance in ETC complex I RNAs (i.e., odds-ratio > 1 for all 11 species and p = 0.001 by two-sided binomial test). These data suggest that in the common ancestor of all Pezizomycotina species analyzed here the Puf3 ortholog bound RNAs encoding ETC complex I components.

The Leotiomyceta Puf3 targets were also significantly enriched for other mitochondrial categories not enriched in the Saccharomycotina targets: genes involved in amino acid metabolism (odds-ratio = 4.8, p = 0.005) and those categorized as "other" under import and biogenesis (odds-ratio = 4.8, p = 0.005) (S5 Table contains results for all mitochondrial subsets; p-values were Bonferroni corrected for testing of 36 subsets).

As the Leotiomyceta Puf3 targets contained 296 targets not annotated as mitochondrial, we searched for other themes among these genes using the annotations of S. cerevisiae orthologs. Despite the large number of targets, we found only a modest enrichment for the broad category of "membrane" (odds-ratio = 2.3, p = 0.0001 after Bonferroni correction for testing all gene ontology [GO] categories) whereas the majority of targets do not connect to a common, known functional theme. Understanding the selective advantages conferred by the conserved interactions with Puf3, in this large set of genes without known functional commonalities, is an important challenge (see Summary and Implications).

Evolutionary reprogramming of post-transcriptional regulation between Puf proteins: Pezizomycotina Puf4 binds >150 mRNAs orthologous to Puf3 targets in Saccharomycotina

The Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets encode particular mitochondrial proteins involved in multiple aspects of mitochondrial organization and biogenesis. The results presented above lead us to a parsimonious model in which the ancestral Puf3 gained these RNAs as targets in an ancestor to Saccharomycotina and Pezizomycotina and subsequently lost its interaction with these RNAs in an ancestor of Leotiomyceta species. We explored what happened to the post-transcriptional regulation of this set of related RNAs in the Leotiomyceta species, and specifically whether the coordinated regulation of these mRNAs might have been preserved via interactions with an alternative RNA binding protein or whether the coregulation of these RNAs was lost or reconfigured.

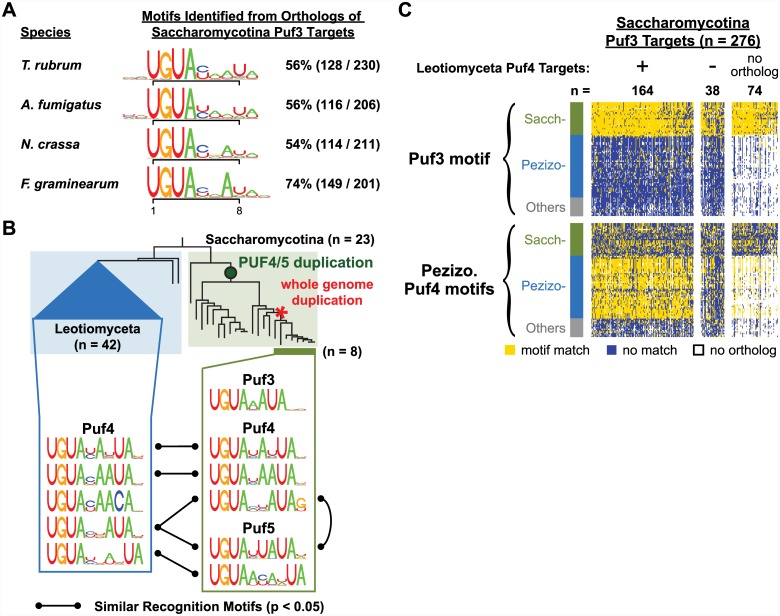

If another protein were to maintain coordinated post-transcriptional regulation of these RNAs, a distinct sequence element corresponding to the binding site of this hypothetical regulator might be a shared feature of these RNAs, discoverable via bioinformatic analysis. We therefore applied the motif finding program REFINE [61] to the Leotiomyceta orthologs of the Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets. We identified a motif in all Leotiomyceta species that was similar to, but distinct from, the Puf3 motif (see Fig 5A for representative motifs; all significant motifs are shown in S8 Fig). The tetranucleotide UGUA at the 5' end of the enriched sequence is a characteristic feature of sequences recognized by Puf family proteins [25,51], but the motif differs from the Puf3 motif in containing an extra nucleotide between the UGUA and the 3' end UA, resulting in a motif nine nucleotides in length instead of eight as with Puf3's motif.

Fig 5. Evidence for Pezizomycotina Puf4 binding to RNA orthologs of Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets.

(A) Motifs identified by the motif discovery program REFINE [61] using the 3' UTRs of orthologs of conserved Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets. Representatives spanning the Leotiomyceta lineage are shown. Numbers on the right indicate how many orthologous RNAs of Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets contain a match to the identified motif. All significant motifs found across the 80 fungi are displayed in S8 Fig, a summary of significance testing can be found in S11 Table, and position frequency matrices can be found in S5 Dataset. (B) Characterization and comparison of Puf binding specificity in Leotiomyceta and Saccharomycotina. Saccharomycotina Puf motifs were identified from S. cerevisiae Puf targets [25] and their orthologs in the seven closely related species up to S. castelli. The Pezizomycotina Puf motifs were identified from orthologs of conserved Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets in Leotiomyceta species. Our approach involved first identifying ten nucleotide sequences (containing UGUA at the 5' end and six other nucleotides) that help discriminate a Puf protein's RNA targets from its nontargets. These informative sequences were then clustered and assigned into groups (Materials and Methods). A black line between motifs indicates similarity in the non-UGUA positions as identified by MotifComparison [84]. For simplicity, a motif can only make one connection to another protein’s collection of motifs, and the motifs with higher similarity were given priority. Position frequency matrices can be found in S5 Dataset. (C) Heatmaps showing the prevalence of RNAs containing sequences recognized by Puf3 or Pezizomycotina Puf4. Each row represents results from one species, and each column represents an ortholog set. Ortholog sets for conserved Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets are shown and divided into groups based on whether the ortholog set is among the Leotiomyceta Puf4 targets. The third group contains Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets that did not have an ortholog in N. crassa. Complete motif search results can be found in S8 Dataset.

The predicted Puf binding motif resembles the sequence recognized by S. cerevisiae Puf4. Previous work suggested Puf4 in Pezizomycotina species binds a small but significant fraction of RNAs encoding mitochondrial proteins [60]. This previous work assumed that the binding specificity of Puf4 in Pezizomycotina species is the same as that of S. cerevisiae Puf4 [60], but two observations suggested that this assumption may not hold. First, sequences matching the motifs that we identified from de novo comparative sequence analysis are found in the majority of the Leotiomyceta orthologs of the Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets (Fig 5A), whereas the previous work assuming a conserved Puf4 recognition motif found putative Puf4 binding sites in only ~20% of these RNAs. Second, Pezizomycotina Puf4 is orthologous to both S. cerevisiae Puf4 and Puf5, yet S. cerevisiae Puf4 and Puf5 binding specificities are distinct. Puf4 and Puf5 resulted from a gene duplication that we have dated to an early ancestor of nearly all Saccharomycotina species (S17 Text), and Puf4 and Puf5 in Saccharomycotina could have experienced changes in RNA sequence recognition subsequent to this duplication, rendering Saccharomycotina Puf4 recognition partially distinct from that of Pezizomycotina Puf4. Indeed, the following analyses provide evidence for such distinctions in binding specificities.

We carried out additional bioinformatic analyses to learn more about the RNA binding specificity of Pezizomycotina Puf4. Because Puf proteins can recognize RNA through multiple binding modes that are not best represented by a single motif [51,53,85], we developed a procedure that identifies enriched ten-nucleotide sequences that start with the canonical UGUA and collapses the sequences into a collection of motifs, instead of just one motif, that together represent the RNA binding specificity (Materials and Methods). This procedure yielded five motifs for Pezizomycotina Puf4 that represent sequences enriched within the 3’ UTRs of Pezizomycotina orthologs of Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets (Fig 5B and S11 Fig). Applying this procedure to characterize S. cerevisiae Puf3, Puf4, and Puf5 specificity yielded one motif for Puf3 and multiple motifs for Puf4 and Puf5 (Fig 5B and S11 Fig). Each of the motifs identified for the S. cerevisiae Puf3, Puf4, or Puf5 protein is supported by previous experimental data [51,85], demonstrating that our procedure can reveal RNA interaction information that would otherwise be obscured by a single motif representation.

Each of the five Pezizomycotina Puf4 motifs identified using our approach above shares a significant similarity with motifs recognized by S. cerevisiae Puf4 and/or Puf5, which are both orthologs of Pezizomycotina Puf4 (Fig 5B). In contrast, apart from the canonical UGUA core element, none of the motifs matched the S. cerevisiae (or N. crassa (Fig 4A)) Puf3 motif. Thus, this comparison provides evidence that Pezizomycotina Puf4 recognizes, at a minimum, a large subset of the ancestral Puf3 targets. This comparison also suggests that S. cerevisiae Puf4 and Puf5 specificity each became restricted to recognize distinct sequences after the gene duplication (S16 Text).

With reasonable confidence in our assignment of sequence motifs recognized by the Pezizomycotina Puf4 orthologs, based on the analyses described above and in S12 Fig, we wanted to determine the subset of former Puf3 targets co-opted by Puf4. To accomplish this, we defined a set of conserved Leotiomyceta Puf4 targets using the above motif criteria (n = 605, ≤1% FDR, Materials and Methods), and we compared it to the conserved Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets (Fig 5C). Of the 276 Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets, 202 have an ortholog in N. crassa, and 164 (81%) of those with orthologs are conserved as Puf4 targets in Leotiomyceta (Fig 5C). These results indicate that the Puf4 ortholog in Leotiomyceta binds a majority of the RNAs that, in Saccharomycotina, are bound by Puf3 and suggest that these RNAs may have been reprogrammed as a large set.

Evolutionary transition of the regulation of a large set of mitochondria-related genes from Puf3 to Puf4

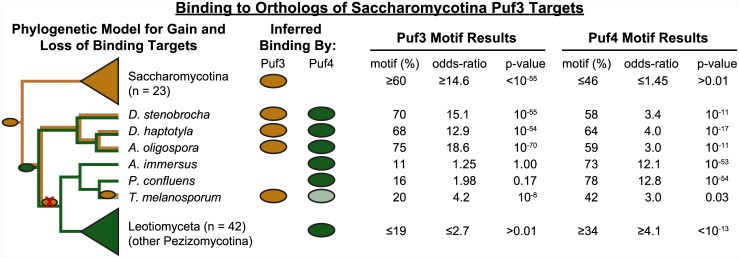

To better reconstruct the evolutionary history of the reprogramming of Puf3 and Puf4 targets that accompanied the divergence of the Saccharomycotina and Pezizomycotina lineages, we looked specifically for species that might represent an intermediate state.

We tested each sequenced fungal genome for enrichment of the Pezizomycotina Puf4 motif in the 3' UTRs of RNAs orthologous to Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets. As expected from our previous results, matches to the Pezizomycotina Puf4 motif were enriched in all Leotiomyceta species, and the Puf4 motif was not enriched in the Puf3 target RNAs in Saccharomycotina species (S14 Fig). Surprisingly, both Puf3 and Puf4 motifs were enriched in RNAs related to Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets in the basal species A. oligospora (Fig 6 and S14 Fig). This overlap suggests that regulation by Puf3 and Puf4 is not mutually exclusive.

Fig 6. Inferring when Puf4 acquired RNA targets related to Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets.

Prevalence of putative Puf3 and Puf4 binding sites in the orthologs of Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets in early diverging Pezizomycotina species. A putative binding site is inferred based on the presence of sequences matching the Puf3 or the Pezizomycotina Puf4 motif. Listed under motif results is the percentage of RNAs with a binding site sequence in the 3' UTR. The odds-ratio represents the enrichment of orthologs of Saccharomycotina Puf3 target RNAs containing a binding site sequence compared to the prevalence in all other RNAs. The p-value was computed using Fisher's exact test and was Bonferroni corrected. A colored oval in the "Inferred Binding By" column indicates significant enrichment of Puf3 or Puf4 sites in each species. The light green oval for Puf4 indicates borderline significance. The cladogram on the left represents a parsimonious model with color along a branch indicating the binding of Puf3 (gold) or Puf4 (green) to the orthologs of Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets (see S21 Fig for an alternative model). A colored oval within the cladogram denotes a gain in binding, and a red X over an oval denotes a loss of binding. Literature results were used to derive the relationships of species within Orbiliomycetes [86,87] and Pezizomycetes [88–91].

To clarify the history of Puf-RNA interaction changes, we analyzed genome and protein sequences for four additional species in early diverging classes, two within Orbiliomycetes and two within Pezizomycetes. This allowed us to assess the full set of sequences for these classes available when our analyses commenced. In the Orbiliomycetes species Drechslerella stenobrocha and Dactylellina haptotyla, as in A. oligospora, putative binding sites for both Puf3 and Puf4 were enriched in the RNAs orthologous to Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets (Fig 6). However, in the Pezizomycetes species, Ascobolus immersus and Pyronema confluens, in contrast to what we found for T. melanosporum, only Puf4 sites, and not Puf3 sites, were significantly enriched in RNAs orthologous to Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets, suggesting still additional complexity in the natural history of this regulatory program in Pezizomycetes (Fig 6).

The prevailing consensus phylogenetic model has the Orbiliomycetes branching prior to the Pezizomycetes [88,92–94]. Mapping our results onto this framework leads to the conclusion that acquisition of Puf4 regulation of some of the Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets preceded the loss of Puf3 regulation of this gene set. This model implies that the loss of Puf3 regulation of this set of genes occurred within the Pezizomycotina lineage (Fig 6). Other models are possible, but all models require a complex sequence of evolutionary events affecting interactions of Puf3 and Puf4 with this RNA target set (S21 Fig, S14 Text).

Puf3 and Puf4 confer distinct selective advantages in Orbiliomycetes

Two general mechanisms can account for evolutionary changes: drift and selective pressure. For the Puf protein targets described above, sequence changes in a common set of at least 164 mRNAs switched them from interacting with one Puf protein to another. Under a model of neutral drift, Puf3 and Puf4 are predicted to have redundant advantages in the regulation of the conserved targets. For a model involving selection, Puf4’s function with respect to the conserved targets would be distinct from Puf3’s function (i.e., Puf3 and Puf4 provide distinguishable selective advantages in the regulation of the common mRNAs).

The models of drift and selection for evolutionary changes make distinct predictions for how Puf3 and Puf4 binding sites have evolved and how the binding sites are distributed among the conserved targets in Orbiliomycetes. Under a model of drift wherein Puf3 and Puf4 are redundant, the fitness cost of losing a Puf3 site from a given RNA would be reduced (and its likelihood thereby increased) by the presence of a Puf4 site in that same RNA, and vice versa. Under a model in which Puf3 and Puf4 provide completely independent functions, the fitness cost, and thus the probability of observing the loss of a binding site for one of these factors in a given RNA, should be independent of the presence or absence of binding sites for the other factor in the same RNA. We inferred the rates of binding site gain and loss across target 3' UTRs in Orbiliomycetes and found that the rate of Puf3 binding site gain or loss was not different when a Puf4 binding site was already present, and vice versa, counter to the prediction for neutral drift (S11 Text, S16 Fig).

Extending the above predictions for how binding sites evolve, a model for redundancy between Puf3 and Puf4 also predicts that fewer of the conserved targets will contain binding sites for both Puf3 and Puf4 than expected by their prevalence. When formalized in a statistical model, Puf3 and Puf4 binding sites will display a negative interaction (i.e., using Puf3 and Puf4 sites to predict which RNAs are conserved targets will not be additive, see model 3 in Table 1). This model can be compared to an alternative model in which Puf3 and Puf4 provide independent advantages in the regulation of these mRNAs; the statistical model formalized from this evolutionary model does not include an interaction term (see model 2 in Table 1). We used stepwise logistic regression to find the most parsimonious model that effectively explains which mRNAs are conserved targets. We compared the fits to the models separately for each Orbiliomycetes species (n = 3), and we found that the best model for all three Orbiliomycetes species was one in which Puf3 and Puf4 independently contributed to the prediction of which mRNAs are conserved targets (Table 1). In other words, the additional parameter invoking dependence between Puf3 and Puf4 sites did not significantly help account for the data (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of stepwise logistic regression tests for dependence between Puf3 and Puf4 in Orbiliomycetes.

| Species | Model a | ΔX2 | p-Value | Variable | β (SE) | Odds-ratio [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. oligospora | 0 | Constant | −3.5 (0.083)*** | |||

| 1 | 336 | 3.70E-75 | Constant | −5 (0.19)*** | ||

| Puf3 Motif | 3.3 (0.21)*** | 28 [19, 43] | ||||

| 2 | 30.6 | 3.10E-08 | Constant | −5.4 (0.21) *** | ||

| Puf3 Motif | 3.2 (0.21) *** | 25 [17, 39] | ||||

| Puf4 Motif | 0.98 (0.18) *** | 2.7 [1.9, 3.8] | ||||

| 3 | 1.63 | 0.2 | Constant | −5.2 (0.25)*** | ||

| Puf3 Motif | 2.9 (0.3)*** | 19 [11, 35] | ||||

| Puf4 Motif | 0.55 (0.38) | 1.7 [0.8, 3.7] | ||||

| Puf3 Motif x Puf4 Motif | 0.55 (0.44) | 1.7 [0.74, 4.2] | ||||

| D. stenobrocha | 0 | Constant | −3.5 (0.088)*** | |||

| 1 | 302 | 1.47E-67 | Constant | −5 (0.2)*** | ||

| Puf3 Motif | 3.3 (0.23)*** | 28 [18, 45] | ||||

| 2 | 19.6 | 9.60E-06 | Constant | −5.3 (0.22) *** | ||

| Puf3 Motif | 3.2 (0.23) *** | 24 [16, 39] | ||||

| Puf4 Motif | 0.83 (0.19) *** | 2.3 [1.6, 3.4] | ||||

| 3 | 0.0247 | 0.88 | Constant | −5.3 (0.27)*** | ||

| Puf3 Motif | 3.2 (0.32)*** | 23 [13, 45] | ||||

| Puf4 Motif | 0.78 (0.4) | 2.2 [0.96, 4.8] | ||||

| Puf3 Motif x Puf4 Motif | 0.072 (0.46) | 1.1 [0.44, 2.7] | ||||

| Dactyl. haptotyla | 0 | Constant | −3.5 (0.083)*** | |||

| 1 | 260 | 1.37E-58 | Constant | −4.7 (0.16)*** | ||

| Puf3 Motif | 2.9 (0.19)*** | 17 [12, 25] | ||||

| 2 | 48.4 | 3.39E-12 | Constant | −5.2 (0.19) *** | ||

| Puf3 Motif | 2.6 (0.19) *** | 14 [9.7, 21] | ||||

| Puf4 Motif | 1.3 (0.19) *** | 3.5 [2.4, 5.1] | ||||

| 3 | 2.62 | 0.11 | Constant | −5 (0.22)*** | ||

| Puf3 Motif | 2.3 (0.3)*** | 9.6 [5.3, 17] | ||||

| Puf4 Motif | 0.84 (0.32)* | 2.3 [1.2, 4.3] | ||||

| Puf3 Motif x Puf4 Motif | 0.64 (0.4) | 1.9 [0.87, 4.2] |

We used stepwise logistic regression to find the most parsimonious model that effectively explains which mRNAs are conserved targets. We used the presence or absence of a Puf binding sequence (“Puf3 Motif” or “Puf4 motif”) to predict the outcome of being an ancestral Puf3 target (defined here as the intersection of Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets with Leotiomyceta Puf4 or Puf3 targets). The term "(Puf3 Motif x Puf4 Motif)" in model 3 represents a statistical interaction that accounts for a dependence between Puf3 and Puf4. Modeling was performed with the R function glm() with family = “binomial.” The accepted model is highlighted in bold for each species, which is model 2 (~Constant + Puf3 Motif + Puf4 Motif) in all three species.

a 0: ~ Constant, 1: ~ Constant + Puf3 Motif, 2: ~ Constant + Puf3 Motif + Puf4 Motif, 3: ~ Constant + Puf3 Motif + Puf4 Motif + (Puf3 Motif x Puf4 Motif)

*** p < 0.0001

* p < 0.01

To summarize, a large set of RNAs that share common functional characteristics appear to be regulatory targets of Puf3 in the Saccharomycotina lineage and targets of Puf4 in the sister lineage Pezizomycotina. In the earliest branch of the Pezizomycotina lineage, these RNAs are targets of both Puf3 and Puf4. The binding sequences of Puf3 and Puf4 appear to have conferred independent selective advantages during the divergence of the Orbiliomycetes lineage, suggesting that the proteins mediate distinct regulatory programs.

Differential change in RNA abundance upon Puf4 protein loss suggests that the regulatory logic of Puf4 network in N. crassa is different from the logic of the Puf3 network in S. cerevisiae

The distribution of Puf3 and Puf4 binding sites in Orbiliomycetes suggests that Puf evolution was subjected to a change in selection. The distinct advantage of Puf4 could have been gained in the ancestor of Pezizomycotina, thereby also affecting Puf evolution in Leotiomyceta, or it could have been gained specifically in Orbiliomycetes. As Puf3 binding sites have largely been lost in the conserved targets in Leotiomyceta, Puf3 appears to have lost its selective advantage in their regulation. This regulation could have been replaced by a functionally redundant Puf4 or replaced by Puf4 with a separate function.

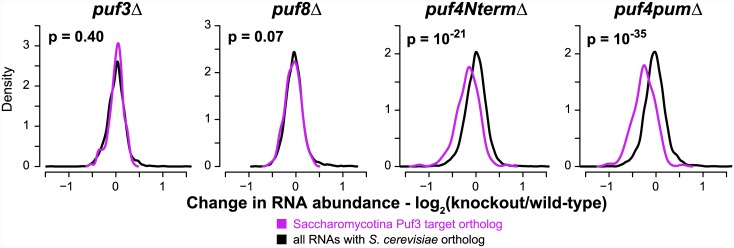

The simplest drift model for conversion to Puf4 targets in Leotiomyceta predicts that Puf4 would have the same affect on these targets as Puf3 after takeover. S. cerevisiae Puf3 mediates the decay of its target RNAs, in part by recruiting the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex [95,96]. In an S. cerevisiae Puf3 knockout, the abundance of Puf3 target RNAs is higher than in wild-type cells with Puf3 present [25,97]. If Puf3’s mRNA decay function has been conserved and shared with Puf3 in ancestor of Pezizomycotina, then Puf4 is predicted to share this function under a model of redundancy.

To probe Puf4's regulation of the orthologs of Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets, we performed gene expression profiling in Puf knockouts in N. crassa using DNA microarrays. We profiled strains with partial gene knockouts of Puf4, one strain with the C-terminus encompassing the Puf RNA binding domain removed (puf4pumΔ) and another with the sequence coding for the N-terminus removed (puf4NtermΔ); strains with gene knockouts for Puf3 or Puf8 were used as controls. (Puf8 appears to have been derived from a Puf3 duplication in a common ancestor of Pezizomycotina and Saccharomycotina, and is predicted to recognize sequences containing UGUA; see S5 Text) RNA was isolated from N. crassa strains growing as vegetative mycelia and compared to RNA isolated from a wild-type strain grown in parallel. In the Puf3 and Puf8 knockouts, there was no significant change in the relative abundance of RNAs orthologous to Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets (Fig 7). However, in each of the Puf4 mutant strains, the relative abundance of these RNAs was selectively altered (Fig 7). This collective change provides additional strong evidence that, in Pezizomycotina, Puf4 regulates the set of RNAs related to the Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets. Importantly, mutation of Puf4 in N. crassa led to a decrease in the abundance of these RNAs, in contrast to the increase observed when Puf3 is knocked out in S. cerevisiae [25,97].

Fig 7. Gene expression profiling of Puf mutants in N. crassa.

Density plots displaying changes in RNA abundance for orthologs of Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets (purple) or orthologs of any S. cerevisiae protein (black). The p-values were computed using the two-sided Wilcoxon test. Note that the partial gene knockouts of Puf4 each exhibited a significant growth defect of ~5% relative to a wild-type strain, signifying a functional defect despite part of the gene remaining in each strain (S13 Fig, S7 Table). Gene expression data can be found in S10 Table.

Although the detailed working of the regulatory networks remains to be elucidated, the opposite effects on RNA target levels indicate that the evolutionary rewiring of targets of Puf3 and Puf4 was accompanied by significant change in the logic of the regulatory program. The simplest model for the timing of this change is that Puf4 gained its distinct regulatory advantage in the ancestor of Pezizomycotina.

The changes in regulators of the conserved Puf mRNA targets were further accompanied by diversification in the RNAs that Puf3 binds (e.g., addition of ETC I targets) and in the RNAs that Puf4 binds (see next section), perhaps altering the coordination of mitochondrial regulation.

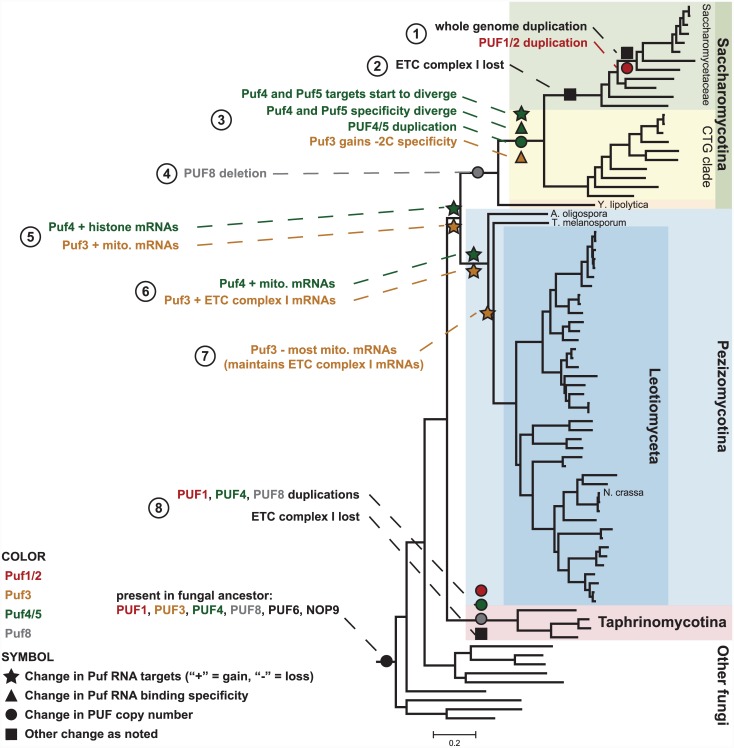

Additional events in the evolution of Pufs and their RNA targets in fungi

The changes in Puf3 and its mRNA targets that we document above are only a subset of the changes that have occurred for Puf proteins in fungi. Fig 8 summarizes a model for events in the evolution of Puf proteins and their targets in fungi, as derived from our analyses and experiments. This figure highlights how gene expression programs diversified as the result of changes in Puf proteins and their mRNAs targets.

Fig 8. Phylogenetic model for changes in Puf proteins and their RNA interactions throughout fungal evolution.

Symbols indicate the type of change, and colors link the indicated event to a particular Puf protein.

Our investigation of Puf3 uncovered links to Puf4. In Pezizomycotina, Puf4 binds hundreds of RNAs distinct from the conserved Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets. We describe these distinctions in S6 Text and S23 Fig, and we describe a speculative model for the transition from Puf3 to Puf4 in S14 Text.

In S16 Text, we document the history of acquisition and loss of Puf genes in fungi. We also relate changes in Puf genes to changes in the regulatory specificity of Puf proteins in fungal evolution.

In S7 Text, we further explore the natural history of Puf4 and its paralog Puf5 in Saccharomycotina. We provide evidence that mRNA targets and binding specificity diverged after the Puf4/Puf5 duplication (S7 Text, S24 Fig, S16 Text). Puf4 and Puf5 may have maintained functionally distinct subsets of the ancestral Puf4 targets (S9 Text). Yet, despite divergence in binding specificity and substantial changes in targets, Puf4 and Puf5 also bind to a small, common set of mRNAs that include those encoding histone proteins. The interactions between the Puf4 protein and RNAs encoding histone proteins appear to have been conserved through much or all of fungal evolution, dating back 750 million years or more, even while many other changes were occurring in Puf4 targets (S8 Text, S24 Fig). It is possible that Puf4 (and other RNA binding proteins) serves multiple functions within the same organism, even organisms as simple as fungi. It is also possible that individual RNA binding proteins serve to functionally connect different RNAs with different functions (see Summary and Implications).

Summary and Implications

The rewiring of gene expression programs plays a major role in evolution and adaption of new species. Considerable effort has been dedicated to analyzing evolutionary changes in transcription factors and in their targets (see [8–13] for reviews), but far less is known about rewiring at the level of RNA and its binding proteins. We surveyed the evolutionary changes in one family of RNA binding proteins and their cognate recognition elements, broadly across eukaryotes and more deeply within fungi (Figs 2 and 8).

Our evidence points to the existence of mRNA targets of Puf proteins that have been maintained for hundreds of millions of years (Figs 2 and 8). Overlaid on this conservation are numerous and remarkable changes in the number of Puf proteins, their specificity, their regulatory output, and their targets. The substantial changes in Puf proteins and targets over evolution followed by long periods of high conservation together underscore the importance of these protein–RNA interactions for organismal adaptation and fitness. Puf proteins represent only ~1% of all RNA binding proteins [15], but similar rewiring of interactions between RNA binding proteins and their targets has likely been a pervasive adaptive strategy throughout evolution.

The highly conserved binding specificity of Pufs suggests that the conserved interactions between each protein and its many mRNA targets place a large constraint on binding specificity. A change in binding specificity thus marks a period of innovation in the gene regulatory program. In the time following Puf4 duplication in Saccharomycotina, the binding specificity of the paralogs (Puf4 and Puf5) became restricted with respect to the ancestral specificity and diverged with respect to each other (Figs 5B and 8 #3). Analogous binding and catalytic promiscuity has been proposed to have been present in ancestral enzymes that later duplicated and specialized [98–103]. Our phylogenetic studies and evolutionary model suggest specificity changes, potential physical origins (S15 Text), and support the idea that aspects of the evolution of RNA binding proteins and their targets proceeded via early promiscuous binding proteins that later underwent gene duplication and subdivision of the ancestral RNA recognition.

The observations that the conserved RNA targets of each Puf protein share functional themes and that a set of functionally-related RNA targets can switch in concert from specific interactions with one RNA-binding protein to another, provide strong support for the notion that RNA binding proteins play an important biological role in organizing and coordinating aspects of gene expression [18,20,21]. Concerted evolutionary changes in mRNAs encoding mitochondrial organization and biogenesis proteins involved hundreds of RNA sequences, placing the same set of orthologous genes in distinct fungal lineages under the regulation of Puf3, Puf4, or both proteins. The evolutionary history of changes in their post-transcriptional regulation, suggested by this analysis, provides strong evidence for the fitness advantage of coordinating the regulation of distinct sets of genes and may harbor clues to the selective pressures that led to changes in the regulatory program.

Whereas essentially all of the inferred RNA targets of Puf3 in Saccharomycotina are transcribed from nuclear genes encoding proteins with mitochondrial functions, not every ortholog of each gene we identified as encoding a Puf3 target in the Saccharomycotina contains a recognizable Puf3 binding site. It is possible that the fitness advantage (or disadvantage) conferred by Puf3 regulation of each of the individual genes in this set is often small enough to allow for considerable genetic drift within the lineage. The evolutionary plasticity that this would allow might help account for the distinct but overlapping functional and cytotopic themes shared by the targets of a given Puf protein in distinct species and lineages.

Although Saccharomycotina Puf3 is essentially monogamous in its relationship to RNAs with mitochondrial functions and has served as a “poster child” for RNA binding protein-based coordination of gene expression, the targets of other Puf proteins are functionally and cytotopically more promiscuous. For example, Saccharomycotina Puf4 binds RNAs encoding histone and nucleolar proteins, while Pezizomycotina Puf4 binds RNAs encoding histone and mitochondrial proteins. The RNA targets of Leotiomyceta Puf4 also encompass a broader array of cellular functions relative to the Saccharomycotina Puf3 targets, including targets with roles in energy metabolism (through the ETC and TCA cycle) and the proteasome. We do not know whether these multiple themes arise because RNA binding proteins help coordinate and integrate cell status and signals between different systems or whether they represent multiple uses of the same protein for independent functions [104–106]. It is also possible that limitations in our understanding of and ability to identify biological function could account for our inability to map mRNA targets to function in a 1:1 fashion.

Evolutionary changes in regulatory RNA–protein interactions are likely to have many similarities to the changes observed in the evolution of transcriptional control (S12 Table). By comparing the changes in transcriptional regulation (as reflected by gain or loss of specific promoter elements) and post-transcriptional regulation (as reflected by gain or loss of Puf-protein recognition elements in the corresponding transcripts) in sets of functionally related genes that share features of both transcriptional regulation and putative Puf-protein regulation, we found that the timing and likely the consequences of evolutionary changes at these two levels of regulation of a common set of genes can be distinct (S13 Text). RNA–protein interactions can thus provide an additional and independently evolvable infrastructure by which global gene expression networks can be orchestrated and reconfigured to generate phenotypic diversity.

By using systematic investigation of evolutionary changes in gene expression programs to enrich the pictures of these programs acquired from years of detailed studies of “representative” model organisms, we found compelling evidence for dramatic changes in the gene expression program at the level of RNA–RNA binding protein interactions during fungal evolution. Mapping evolutionary changes in post-transcriptional regulation can provide new insights into the makeup, logic, and malleability of gene expression programs, and may contribute to our ability to engineer new phenotypes by rewriting or de novo design of post-transcriptional programs.

Materials and Methods

Retrieving Data for Species Represented in the InParanoid Database

Protein sequence files and SQL tables containing ortholog information were downloaded from InParanoid [107] (version 7.0, http://inparanoid.sbc.su.se/). Genome sequences for each species were downloaded in July 2010 from the sources listed in S3 Table.

Identifying Puf Proteins Based on Similarity to Known Puf Proteins

We used a two-step BLASTP search to identify putative Puf proteins in each species. A custom BLAST database was created for each species' protein sequences using makeblastdb (part of the blast+ package from NCBI). In the first step, the sequences of the Pum domains of S. cerevisiae Pufs 1–6 (Puf1:557–913, Puf2:511–872, Puf3:513–871, Puf4:539–888, Puf5:188–596, Puf6:133–483) and the complete protein sequence of S. cerevisiae Nop9 were used as a query to search for similar protein sequences in each species using blastp (NCBI BLAST version 2.2.23 [108–110]), using an E-value cutoff of 10−5. Sequences identified in the first step were then used to search for additional Puf proteins in a second step, also with an E-value cutoff of 10−5. In the second step only the parts of the protein sequence identified in the first step as having significant similarity to S. cerevisiae Pum domains were used. If more than one of the query sequences from the first step was similar to a searched sequence, the similar sequence of longest length was kept.

Results from the first round yielded near-complete coverage of known Pufs from Caenorhabditis elegans, A. thaliana, and O. sativa (12/12, 24/26, and 17/19, respectively) [38,111–113]. The second round yielded one more known Puf from A. thaliana and two from O. sativa. Additionally, putative Pufs in these organisms were found in both rounds (one from the first round, two from the second). Two of the three additional putative Pufs contained one or more Puf repeats according to the SMART annotation tool [114,115], suggesting these hits are real Puf proteins. As our next step was to classify Puf proteins, we aimed for high coverage at the expense of a small fraction of false positives.

Classifying Puf Proteins as Orthologs to S. cerevisiae Puf Proteins or N. crassa Puf8

We classified Puf proteins as orthologs to each of the S. cerevisiae Puf proteins or to N. crassa Puf8, a previously uncharacterized Puf that we identified and named. We chose S. cerevisiae because of our focus on fungi in this work, and the results suggest that S. cerevisiae Pufs well represent the diversity of Puf proteins found across eukaryotes, with the exception of N. crassa Puf8, which our initial phylogenetic analysis suggested was deleted in an ancestor of S. cerevisiae. More than 90% of the eukaryotic Pufs and 98% of the fungal Pufs were classified as orthologs to S. cerevisiae Pufs or N. crassa Puf8.

We classified Puf proteins based on a combination of information: reciprocal best BLAST hits, the pattern of amino acids predicted to contact RNA bases within each Puf repeat, and phylogenetic analysis. For reciprocal best BLAST, we checked each Puf against S. cerevisiae and N. crassa Pufs. A protein was tentatively assigned as an ortholog if it was a reciprocal best BLAST hit to at least one S. cerevisiae or N. crassa Puf protein, and the reciprocal best BLAST hit did not disagree between the S. cerevisiae Puf and its N. crassa ortholog.

A Puf protein was also tentatively assigned as an ortholog to S. cerevisiae Puf1/Puf2, Puf3, Puf4/Puf5, or N. crassa Puf8 based on predicted RNA-contacting amino acids. RNA-contacting amino acids are highly conserved but are different in distantly related Pufs. The S. cerevisiae Puf1 and Puf2 have similar RNA-contacting amino acids, and those in S. cerevisiae Puf4 and Puf5 are identical to each other so this type of classification cannot distinguish between these two proteins. Outside of these two pairs, the RNA-contacting amino acids are sufficiently different to allow this classification. We performed this classification manually and note any differences between the protein and its tentatively assigned ortholog with respect to these amino acids in S1 and S2 Tables.

Puf proteins were assigned a final ortholog if the BLAST-based classification or the RNA contact classification identified a tentative ortholog and so long as the assignment from the two classification methods did not disagree. Any Pufs not assignable by these criteria were subject to a phylogenetic analysis. Protein sequences for S. cerevisiae Pufs, N. crassa Pufs, and the unassigned Pufs were aligned as a group using MUSCLE [116,117] in Geneious (using default settings). Columns with more than 50% gaps were stripped, and a maximum likelihood tree was built using PhyML [118,119] implemented through Geneious (WAG substitution model, 8 substitution rate categories, best of NNI [Nearest Neighbor Interchange] and SPR [Subtree Pruning and Regrafting] search). Many of the remaining Pufs were classified based on this tree (S1 and S2 Tables). In some cases, we referred back to the pattern of RNA-contacting amino acids to inform our decision (see notes in column “unknownGroup_ML tree” in S1 and S2 Tables)

The relationship of a group of Puf proteins from worms, including C. elegans Fbf-1 and Fbf-2, remained ambiguous. This relationship was resolved by considering which Pufs were likely present in the ancestor of these species. These worm Pufs tend to have eight predicted Puf repeats and are closest to Puf3 and Puf4 among S. cerevisiae Pufs. We inferred that the Puf4 gene was deleted in an ancestor to metazoans and the choanoflagellate Monosiga brevicollis and therefore could not be orthologous to these worm Pufs. In contrast, Puf3 is inferred to be present in the ancestor of these worms, and we had already identified other Puf3 orthologs in these species. We assigned the worm Pufs as orthologs to Puf3 under a model that Puf3 underwent several duplications (duplication of Puf3 and duplication of duplicates) along the worm lineage with subsequent divergence of many of the duplicates.

Multiple Sequence Alignments, Calculation of Percent Identity, and Definition of Puf Repeats

For S2 and S5 Figs, protein sequences were aligned using MUSCLE [116,117], as implemented through the program Geneious and using default settings. For calculating percent identity of residues, all columns containing gaps in S. cerevisiae Puf3 were removed. Percent identity was calculated as the percent of residues matching the most abundant residue within each column of the alignment. Puf repeats were defined using the SMART annotation tool [114,115]. The S. cerevisiae Puf3 repeats are residues 538–573, 574–609, 610–645, 646–681, 682–717, 718–752, 760–795, and 809–844. The multiple sequence alignments and calculated percent identities are presented in S2 Dataset.

Extracting 3' UTR Sequences for Species Found in the InParanoid (v7) Database and Fungi Species

Protein sequences were mapped back to the respective genome to identify coding sequence boundaries using standalone BLAT v34 [120] (with parameters–q = prot–t = dnax). BLAT output was processed to identify for each query the hit with the smallest discrepancy (defined as the smallest difference between query and match lengths). We assessed overall performance by calculating the average percent discrepancy and average coverage for the best hits. The median across all InParanoid species for average coverage was 99.8%, and the average discrepancy was 0.2%. Eighty of the InParanoid species had proteins mapping back to the genome with an average coverage >99% and a discrepancy <1%. G. gallus had the lowest average coverage (90.6%), and G. lamblia had the highest average discrepancy (12.5%). All 80 fungi had an average coverage of >99% and a discrepancy of <1% (median: 99.9% coverage, 0.1% discrepancy). The 500 nucleotides downstream (3' on the coding strand) of each best BLAT hit were extracted as the 3' UTR.

Testing Puf3/Pumilio Target Conservation across Eukaryotes

We used a custom Perl script analogous to Fastcompare [63,74,75] to search for the Puf3 motif in orthologous sequence sets of two species, yielding a 2 x 2 contingency table of the number of sets that have a motif match in both species, in only one of the species, or in neither of the species. We searched 3' UTRs of orthologs identified by InParanoid in 99 eukaryote species [107]. The significance of ortholog sets that both have motif matches was computed by the hypergeometric test. To control for sequence similarity expected between closely related species, we repeated the search using permutations of the Puf3 motif (e.g., UA[ACU]AUAGU) and used the hypergeometric p-value as a score to rank the Puf3 motif against all of its permutations (n = 1119). We report a p-value if the overlap between two species for the Puf3 motif is significant after correcting the hypergeometric p-value for multiple hypothesis testing (p < 0.05 after Bonferroni correction) and if the Puf3 motif is ranked in the top 1% (i.e., empirical p < 0.01 for comparison against all permutations).

Inferred Eukaryote Phylogeny

Phylogenetic trees were inferred using methods similar to those used previously [121–123]. To identify proteins whose sequence has preserved the underlying phylogenetic signal, we searched for proteins that contained an ortholog to a human protein in at least 90 of the 99 species investigated herein, and that within each species contained at most two orthologs to a human protein (1:1 or 2:1 orthologs); we identified a total of 53 sets of proteins meeting this criteria, and within each set, most species only had one ortholog for each human protein used (1:1 orthologs). Each set of orthologs was multiply aligned using standalone MUSCLE [116,117] (version 3.8.31 with default settings). The alignments were concatenated, and during the concatenation process, we kept only the first ortholog encountered for each species and added a sequence of gaps where an ortholog was not found. Columns containing more than 5% gaps were removed, yielding a final alignment with 27,239 columns. A tree was inferred by maximum likelihood using standalone PhyML [118,119] (version 20120412, parameters -d aa -b 1 -m WAG -o tlr -s SPR—n_starts 10 -v e -c 8). For the phylogeny displayed, the descendants of a node were collapsed if a branch length from the ancestor node to one of the descendant nodes (i.e., the internode distance) was greater than 0.65. The branches that were collapsed largely reflect uncertainty in the relationship of species diverging earliest within eukaryotes and uncertainty about the root of the tree. The final phylogeny displayed generally agrees with the literature consensus, and points of disagreement did not affect our conclusions. For example, N. vectensis, T. adhaerens, Capitella sp. I, H. robusta, and L. gigantea are proposed to be basal metazoan species in the literature consensus, and the worms (nematode, trematode) are proposed to be grouped with the insects to the exclusion of vertebrates. The final phylogeny with species names can be found in S20 Fig. The multiple sequence alignment and a newick-formatted tree can be found in S3 Dataset.

Inferred Fungal Phylogeny

For fungi we identified 20 sets of proteins that across all species were 1:1 ortholog to an S. cerevisiae protein. We allowed A. macrogynus to have multiple orthologs to each S. cerevisiae protein because its genome contains many duplicated genes. Each set of orthologs was multiply aligned using standalone MUSCLE [116,117] (version 3.8.31 with default settings). The alignments were concatenated, and during the concatenation process, we kept only the first A. macrogynus sequence encountered. Columns containing gaps were removed, yielding a final alignment with 4,251 columns. An initial maximum likelihood tree was inferred using standalone PhyML [118,119] (version 20120412, parameters -d aa -b 100 -m WAG -o tlr -s SPR—n_starts 10 -v e).

The initial fungi phylogeny placed A. oligospora (a species within Orbiliomycetes) and T. melanosporum (a species within Pezizomycetes) together. We suspected that this was a long-branch artifact, as it disagreed with previous studies that used a higher sampling of species within Orbiliomycetes and Pezizomycetes [88,92–94]. The previous studies placed Orbiliomycetes and Pezizomycetes as separate lineages that diverged the earliest within Pezizomycotina. Nevertheless, one study [88] disagreed with others [92–94] in terms of which lineage is most basal (i.e., earliest diverging). We chose to constrain the topology to place Orbiliomycetes (A. oligospora) as the most basal lineage followed by Pezizomycetes (T. melanosporum) then the rest of Pezizomycotina. This order is consistent with two of the three studies that inferred phylogenies using multiple gene sequences [92,94] and the study using the "ultrastructure" character of different species [93]. The alternative topologies (the one from the literature and our unconstrained topology) lead to models in which an additional loss event is required to account for the Puf3 pattern and thus would alter details of our models but not the overall conclusions drawn (S21 Fig).

We constrained the tree topology and optimized the branch lengths and rate parameters using PhyML (with parameter -o lr). The resulting tree was rooted between the species within Chyridiomycota (A. macrogynus, B. dendrobatidis, S. punctatus) and all other fungi, but this root should be viewed as a hypothesis. The final phylogeny used for fungi contains discrepancies with previously published trees, but the discrepancies occur at parts of the tree where the literature itself is inconsistent. As the alternative topologies would not affect our conclusions, we did not attempt to resolve these discrepancies. The multiple sequence alignment and a newick-formatted tree can be found in S3 Dataset.

Retrieving Sequence Data and Identifying Orthologs in Fungi

Protein and genome sequence data were retrieved from the sources listed in S4 Table. We used InParanoid v4.1 [107,124–126] (default settings with no outgroup species) to identify orthologs of S. cerevisiae or N. crassa proteins in each of the other fungi. Tables containing orthologs can be found in S4 Dataset.

N. crassa Strains and Linear Race Growth Assays

N. crassa strains were obtained from the Fungal Genetics Stock Center [127]. Strains were the wild-type N. crassa 74-OR23-1VA (FGSC #2489) [128] and knockout strains of the gene NCU06199.2 (PUF1, FGSC #13194), NCU06511.2 (PUF3, FGSC #13380), NCU01774.2 (part of PUF4 removes N-terminus of protein, FGSC #14089), NCU01775.2 (part of PUF4 removes Pumilio domain, FGSC #14547), NCU01760.2 (PUF8, FGSC #15499), or NCU06199.2 (PUF1, FGSC #13194 [129]. The Puf4 gene was originally annotated as two separate genes, so the Neurospora knockout collection had a separate knockout strain for each of the original annotated genes. One strain has a deletion of the sequence encoding the 5' portion of the mRNA including the predicted natural start codon. The other deletion strain is missing the sequence encoding the 3' end of the mRNA, including the sequence that encodes the Pumilio RNA binding domain and the natural translation stop codon. The knockout strains were homokaryons and of mating-type A. Strains were preserved long-term by resuspending conidia in sterile 7% milk, mixing with an equal volume of 50% glycerol, and storing at −80°C.

Agar "race" tubes were prepared in 25 mL pipets (Falcon 352575). Pipets were filled with 13 mL of autoclaved medium containing 1X Vogel's Medium, 1.5% agar (BD Difco 214530), and 2% of a carbon source (sucrose, glucose, maltose, or glycerol). Medium was allowed to solidify on a flat surface.