Abstract

Proteins are complex molecules, yet their folding kinetics is often fast (microseconds) and simple, involving only a single exponential function of time (called two-state kinetics). The main model for two-state kinetics has been transition-state theory, where an energy barrier defines a slow step to reach an improbable structure. But how can barriers explain fast processes, such as folding? We study a simple model with rigorous kinetics that explains the high speed instead as a result of the microscopic parallelization of folding trajectories. The single exponential results from a separation of timescales; the parallelization of routes is high at the start of folding and low thereafter. The ensemble of rate-limiting chain conformations is different from in transition-state theory; it is broad, overlaps with the denatured state, is not aligned along a single reaction coordinate, and involves well populated, rather than improbable, structures.

The kinetics of protein folding is often remarkably simple. For many proteins, both folding (from the denatured state D to the native state N) and unfolding processes are single-exponential functions of time (1–5). Combined with the observation that the ratio of the forward to reverse rate constants equals the equilibrium constant, folding is often described in terms of a two-state mass-action model,

|

and a corresponding Arrhenius diagram (Fig. 1). The main ideas underlying such Arrhenius diagrams are the following: (i) a single reaction coordinate exists from D to N; (ii) relatively distinct molecular structures appear in sequential order along the reaction coordinate, e.g., D → TS → N; and (iii) the single-exponential behavior arises from a bottleneck called the transition state (TS) (6), which also appears in Kramers' theory for reactions in solution (7), resulting from a slow step to an improbable structure. Barriers originated to explain why chemical and physical processes are slower than a “speed limit” such as kBT/h = 0.16 psec, where kB is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, and h is Planck's constant.

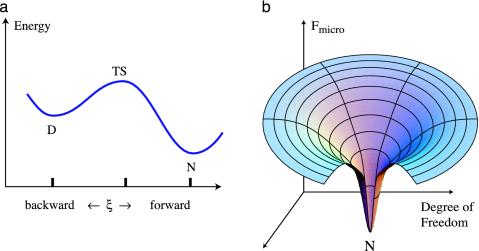

Fig. 1.

(a) Transition-state explanation of single-exponential processes, such as protein folding, involves a rate-limiting step, shown as an obligatory thermodynamic barrier. (b) Theory and simulations show that energy landscapes for protein folding are funnel-shaped and have no apparent microscopic energetic or entropic barriers.

But for protein folding, this macroscopic description does not give microscopic insight. Mass-action symbols such as D and TS define macrostates, or ensembles of chain conformations. What chain conformations, i.e., microstates, constitute those ensembles? Two main issues exist. First, barriers explain “slowing down” relative to an upper speed limit, but the challenge for proteins is to explain why folding is so fast, not why it is slow. Hundreds to thousands of bonds must rotate for a typical denatured conformation to become native, fine details of packing must be satisfied, and each rotation probably requires 1–100 psec, yet some proteins can fold in as little as 10 μsec (2, 4). The key to understanding the mechanism of protein-folding kinetics is in explaining how this happens so quickly.

Second, because the many denatured conformations are so different from each other, a single microscopic reaction coordinate, or trajectory, cannot lead to the folded state. Folding kinetics has been studied by microscopic theory and simulations (8–18). This type of modeling shows that protein folding can be described in terms of funnel-shaped energy landscapes (19–21) (see Fig. 1b). The depth represents the interaction free energy of the chain in fixed configurations, and the width represents the chain entropy. At deeper levels, the landscape represents lower-energy, more native-like structures; the funnel shape results because the more native-like the energy, the fewer the conformations (22). The funnel concept shows how a single native structure can emerge rapidly from an astronomical number of different denatured starting conformations, but funnel pictures are often shown without a barrier. It has been suggested that if all the steps were energetically downhill, folding kinetics would not be two-state (8, 17). In short, TS theory rationalizes two-state kinetics but not the speed, whereas funnel cartoons rationalize the speed but not the two-state kinetics. How can we understand both behaviors?

Experiments are not yet able to observe the microscopic folding processes. Experiments “see” only ensemble-averaged properties. Atomically detailed computer simulations give valuable insights (23–25), but they explore only a relatively small sampling of the conformational space. Currently, questions of the full microscopic folding kinetics can only be addressed by using low-resolution models of the type used here. Here, we generate and solve the master equation for the folding of the 2D lattice model. We use a Gō potential (26). Gō models are widely used for studying two-state protein folding (27–30), because such models have two-state kinetics for folding and unfolding, unique lowest-energy native states, and exponentially growing conformational searches with chain length. Restricting the conformations to a 2D lattice reduces the conformational space so that the complete solution is tractable, without compromising any of the general properties of proteins described above (see Methods). To obtain the kinetics, we follow the eigenvector method of Banavar and colleagues (31). We find the exact solution of the master equation for folding in terms of its eigenvalues and eigenvectors to reveal the details of the rate-limiting transitions. From this model, we reach three conclusions about the microscopic basis for fast-folding kinetics.

Methods

We use a 2D lattice formulation of the Gō model. The conformation-to-conformation transition rate is given by kij = exp(–Bθ – ηr), where θ is the number of bond angles that differ between structures i and j, and r is the sum of the squares of the displacements of each bead of the chain. The parameters B and η correspond to the energies for dihedral angle rotation and diffusion through the solvent, respectively. Values of B = 0.5 and η = 0.1 give transition probabilities similar to those in traditional Monte Carlo dynamics move sets. The transition rates are multiplied by a Metropolis factor: the lesser of exp(–Hij) or 1, where Hij is the difference in energy between the first and second conformations. In a Goō model this energy is determined solely by the number of native contacts.

The evolution of the ensemble with time is governed by a master equation (31, 32): dp(t)/dt = Kp(t), where p is a vector that contains the population of each conformation at each instant, and K is a matrix that contains the transition probability (per unit time) between each conformation. The elements of this matrix are the weighted kij values described above. The dynamical evolution of this entire ensemble can be solved exactly in terms of the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the matrix K by using readily available numerical algorithms (33). (The results in this article are based on a chain of nine residues, which leads to a tractable 750-by-750 matrix for the master equation.) The smallest nonzero eigenvalue corresponds to the rate constant for the onset of the native state. Its corresponding eigenvector represents all the relative contributions of the microscopic transitions that contribute to the slowest rate-limiting step. Hence, this eigenvector defines the TS macrostate.

Results

Fast Folding Results from Parallel Microscopic Routes. Fig. 2 compares series vs. parallel kinetic processes. Fig. 2 Right shows the bottleneck principle: if microscopic steps are in series, one step is rate-limiting. An example would be a high-energy protein conformation. In this model, the folding flux (number of proteins folded per unit time) would be slower than the slowest microscopic step, the flux through the bottleneck step. In contrast, Fig. 2 Left shows that in a parallel process, the folding flux is faster than the fastest microscopic step. Fig. 3 shows that in the fast early steps, our simulations most closely resemble the parallel model. If the rate of a microscopic step is kij from conformation i to j and pi is the population of i, then the flux from i to j is pikij. But if multiple routes go to j, the flux to j is higher, Σipikij, because of the parallelization of routes.

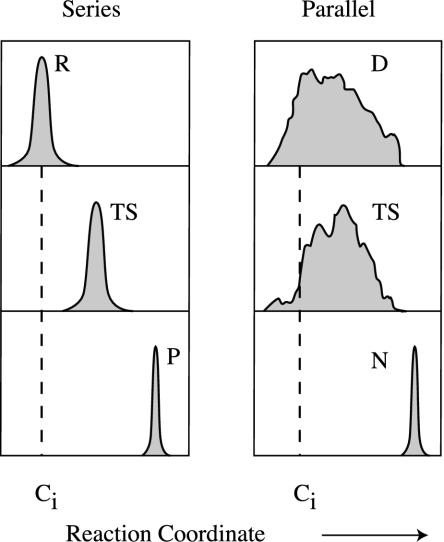

Fig. 2.

Series vs. parallel models of kinetics. (Right) When microscopic steps are in series, the macroscopic flux is limited by the microscopic bottleneck rate. The hypothetical numbers illustrate the fluxes through different microscopic steps. (Left) But if parallel microscopic routes exist, the macroscopic flux is greater than the largest microscopic flux.

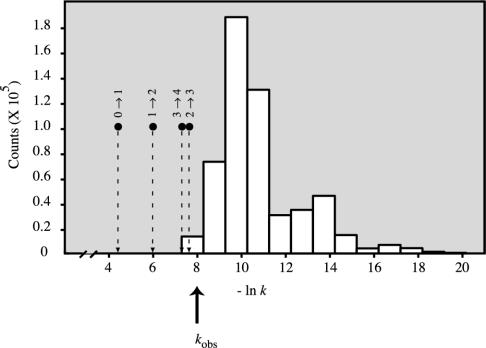

Fig. 3.

The rate of folding is faster than almost all the microscopic transitions between conformations, supporting the parallel model. The large arrow shows the overall folding rate. The histogram to the right shows the distribution of microscopic transition fluxes. The small arrows on the left show the level-to-level transition rates between energy levels: 0–1 indicates transitions at the top of the energy funnel, 1–2 is the next level down, etc. The level-to-level fluxes are high because many microroutes contribute to them.

A previous argument [the Levinthal paradox (34)] suggested that the folding search for the native structure should be slowest at the earliest stages, because the chain has so many high-energy (open, denatured) conformations to explore. Our model shows the opposite: the chain wastes the least amount of its folding time in the high-energy states. The large numbers conspire to speed up folding, not to slow it down. Fig. 3 shows this also in another way. The energy level-to-level rates are faster than the conformation-to-conformation rates, because the level-to-level transitions include many parallel routes. Hence, we believe that early stages of folding are not well described by the term “search,” for the same reasons that water moving down a hillside is more akin to a highly directed flow, and less like a search.

The Separation of Timescales Results from Diminishing Multiplicities of Routes Down the Landscape. Zwanzig (16) has noted that single-exponential behavior can result from a separation of timescales. In our model, the single-exponential dynamics does not result from a microscopic barrier (i.e., a barrier along only one specific trajectory). Rather, we observe that the separation of timescales results from the funnel-shaped route structure. This route structure is a property of the whole landscape, not of a single trajectory. In funnel landscapes, the bottleneck is relatively low where the funnel becomes narrow.

Consider two different conformations: one is high-energy, nonnative and the other is low-energy, nearly native. The unfolded conformation has a much higher probability per unit time of making a new native contact to proceed downhill, simply because it can happen so many different ways. In contrast, the near-native conformation is slower to make a new native contact, because the vast majority of conformations accessible to it are uphill and more unfolded. It has few routes downhill. Zwanzig has called such near-native conformations “gateway” structures (16). When folding is initiated, fast rearrangements take place to reach the gateway conformations, then slow steps from there to the native state. Gateway conformations act like transition states in the sense that they are obligatory and rate-limiting, but they differ in a fundamental way from transition states: they are not rare, improbable, or high in free energy. Rather, the gateway conformations are among the most heavily populated of the nonnative conformations because they are the funnelnecks for the microroutes.

Hence two-state kinetics need not be caused by a structure of low population that is reached slowly. It can also be caused by a state having few exit routes that is reached quickly.

Transition-State Conformations Overlap with Denatured Conformations. What are the rate-limiting conformations in the funnel model? Four macrostates in the model are relevant: N, the single native conformation; Du, the Boltzmann-weighted denatured ensemble under the unfolding conditions from which folding is initiated; Df, the Boltzmann-weighted nonnative ensemble under particular folding conditions; and TSf (the apparent transition state under folding conditions), the eigenvector of conformations that fold to the native state having the lowest eigenvalue relaxation time.

In transition-state theories, the macrostates, such as reactants, intermediates, transition states, or products, are all identifiable as distinct ensembles of microstates (specific atomic structures) that occur along a single reaction coordinate. Along any such 1D coordinate, a state A is either “before” or “after” some other state B. Applied to proteins, it implies the transition state is between, and distinct from, the denatured state (D) and the native state (N): D → TS → N.

That description is macroscopic, however. In chemical rate theory, the observed kinetics (macroscopic behavior) has a microscopic explanation in terms of structure: the bottlenecks are specific atomic structures along a sequence of structures from reactant to product. For chemical reactions, macro- and microdescriptions coincide. But for folding, the present model microdescription of folding bears little resemblance to the macrodescription. No single trajectory, reaction coordinate or specific sequence of the microstates exist. Fig. 4 Right is a cartoon showing how the TSf ensemble could be so broad that it includes many of the same conformations that are in Du and Df. Indeed, this finding is observed in our simulations (Fig. 5). No individual chain conformation is exclusively in one state Du, Df, or TSf, without being in the others at the same time. These ensembles differ only in the statistical weights of the individual conformations. The heterogeneity of the rate-limiting steps has also been observed in other simulations (23, 35, 36). The folding process is the evolution of a single ensemble, not a time sequence of distinct ensembles, such as the pouring of D into TS followed by the pouring of TS into N.

Fig. 4.

(Left) The transition-state model involves macrostates (R, reactant; TS, transition state; P, product) that are small, localized ensembles of microstates. Each microscopic structure is a member of only one macrostate. (Right) The present model shows that the macrostates for two-state protein folding (D), the denatured state, or TS, the transition state under folding conditions) are broad ensembles that encompass all the nonnative chain conformations. A given chain conformation is not a unique member of only one macrostate.

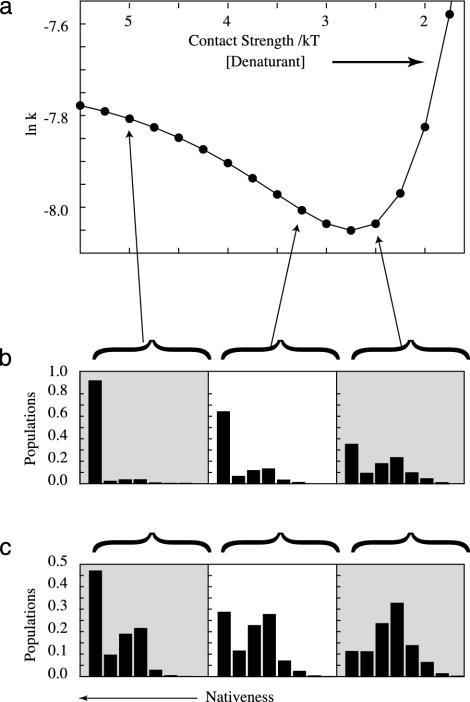

Fig. 5.

(a) Chevron plot showing predicted relaxation rate (k = kf + ku) versus strength of native contacts. The histograms show the distribution of conformations (most native-like to the left) under different folding conditions for the denatured ensemble Df (b) and the apparent transition state TSf (c). Under increasingly native-like conditions, both ensembles Df and TSf become more native-like. Hence, the left (folding branch) of the chevron curve shows rollover, a deviation from linearity. Under strong native conditions, the Df ensemble is more native-like than the TSf ensemble.

In TS theory models, the transition state is between the reactant and the product. For folding, this placement would mean D → TS → N, but this is not what we observe here. The ensembles Du, Df, and TSf change with external conditions. If we rank-order these macrostates in terms of their structural similarity to the native state, Fig. 5 shows that, under strong native conditions, the order would be TSf → Df → N. This nonsensical result is a consequence of using a single reaction coordinate at the microscopic level and a series model to represent a process that is intrinsically parallel.

We conclude that the TS is broad, but caveats exist. First, even in this model, different conformations have different weights. Ways exist to cluster the most important conformations into macrostates (37) that resemble more traditional ways of viewing transition states. Second, the breadth depends on conditions; weak folding conditions lead to a broader transition state. Our conclusion that the TS is late in folding may be limited by the short chain lengths accessible in our model. Indeed, the present model is perhaps best regarded as representing the early fast stages of secondary-structure formation and some assembly, which may represent nucleation events, because larger complexes are not explored here.

A principal test of a two-state folding model is whether it predicts the “chevron” (V-shaped) dependence of the folding rate on the driving force (denaturant or temperature) that is observed in experiments (38–41). Fig. 5 shows that this model does so. Moreover, some experiments show small downward curvature on the left (folding) branch of the chevron plot, called “rollover” (42, 43). This downward curvature is also predicted by the model. What is the basis for this curvature? Classical theories expect no curvature, based on assuming that the TS doesn't change with external conditions. In that light, the curvature has been explained as resulting from intermediate states (43) or broad transition states (44). Fig. 5 shows the microscopic interpretation that the gateway conformations change with denaturant or temperature. TSf reaches a limiting native-like distribution under strong native conditions.

Discussion

Some proteins fold and unfold rapidly with single-exponential (two-state) kinetics. Some explanations have been based on transition-state assumptions that (i) macrostates (D, TS, and N) are distinct nonoverlapping collections of identifiable microstates, (ii) there is a single reaction coordinate, so the terms “forward” and “backward” have meaning, and (iii) the rate of folding does not exceed the rate of some microscopic (energetic or entropic) bottleneck step.

The present work offers a different interpretation at the microscopic level. (i) The macrostates, the denatured and apparent transition states, encompass all the nonnative conformations, but each macrostate is a different distribution of microscopic populations. (ii)Multiple microscopic routes exist in the high-dimensional conformational space, so a single microscopic reaction coordinate is not sufficient. (iii) Folding is faster than an intrinsic slowest rate, not a slowing down relative to an intrinsic fastest rate. (iv) The folding flux can be greater than individual microscopic fluxes. In this model, the apparent rate limit that gives single-exponential behavior arises because the multiplicity of parallel routes diminishes at the bottom of the folding funnel, not as the result of a microscopic barrier.

Acknowledgments

J.S. was a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Predoctoral Fellow. K.D. thanks the National Institutes of Health for support (Grant GM34993).

Abbreviation: TS, transition state.

References

- 1.Jackson, S. E. (1998) Folding Des. 3 R81–R91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burton, R. E., Myers, J. K. & Oas, T. G. (1998) Biochemistry 37 5337–5343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim, P. S. & Baldwin, R. L. (1990) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 59 631–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fersht, A. R. (1999) Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science (Freeman, New York).

- 5.Englander, W. (2000) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 29 213–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eyring, H. (1935) J. Chem. Phys. 3 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramers, H. A. (1940) Physica 7 284–304. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryngelson, J. D., Onuchic, J. N., Socci, N. D. & Wolynes, P. G. (1995) Proteins 21 167–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pande, V. S., Grosberg, A. Y. & Tanaka, T. (1997) Folding Des. 2 109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan, H. S. & Dill, K. A. (1994) J. Chem. Phys. 100 9238–9257. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Socci, N. D., Onuchic, J. N. & Wolynes, P. G. (1998) Proteins 32 136–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klimov, D. K. & Thirumalai, D. (1998) J. Mol. Biol. 282 471–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shakhnovich, E. I., Abkevich, V. I. & Ptitsyn, O. B. (1996) Nature 379 96–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou, Y. & Karplus, M. (1999) Nature 401 400–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dill, K. A. (1999) Protein Sci. 8 1166–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zwanzig, R. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94 148–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bicout, D. J. & Szabo, A. (2000) Protein Sci. 9 452–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zangi, R., Kovacs, H., van Gunsteren, W. F., Johansson, J. & Mark, A. E. (2001) Proteins 43 395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leopold, P. E., Montal, M. & Onuchic, J. N. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89 8721–8725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolynes, P. G., Onuchic, J. N. & Thirumalai, D. (1995) Science 267 1619–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dill, K. A. & Chan, H. S. (1997) Nat. Struct. Biol. 4 10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan, H. S. & Dill, K. A. (1989) Macromolecules 22 4559–4573. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lazaridis, T. & Karplus, M. (1997) Science 278 1928–1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duan, Y. & Kollman, P. A. (1998) Science 282 740–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kazmirski, S. L., Wong, K.-B., Freund, S. M. V., Tan, Y.-J., Fersht, A. R. & Daggett, V. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98 4349–4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taketomi, H., Ueda, Y. & Go, N. (1975) Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 7 445–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takada, S. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 11698–11700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galzitskaya, O. V. & Finkelstein, A. V. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 11299–11304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alm, E. & Baker, D. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 11305–11310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muñoz, V., Henry, E. R., Hofrichter, J. & Eaton, W. A. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 11311–11316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cieplak, M., Karbowski, J., Henkel, M. & Banavar, J. R. (1998) Phys. Rev. Lett. 80 3654–3657. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan, H. S. (1998) in Monte Carlo Approach to Biopolymers and Protein Folding, eds. Grassberger, P., Barkema, G. T. & Nadler, W. (World Scientific, Teaneck, NJ), pp. 29–44.

- 33.Press, W. H., Teukolsky, S. A., Vetterling, W. T. & Flannery, B. P. (1992) Numerical Recipes in C (Cambridge Univ. Press, New York), Chap. 11.

- 34.Levinthal, C. (1968) J. Chim. Phys. 65 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klimov, D. K. & Thirumalai, D. (2001) Proteins 43 465–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sali, A., Shakhnovich, E. & Karplus, M. (1994) Nature 369 248–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ozkahn, S. B., Bahar, I. & Dill, K. A. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8 765–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jackson, S. E. & Fersht, A. R. (1991) Biochemistry 30 10428–10435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Otzen, D. E., Kristensen, O., Proctor, M. & Oliveberg, M. (1999) Biochemistry 38 6499–6511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burton, R. E., Huang, G. S., Daugherty, M. A., Calderone, T. L. & Oas, T. G. (1997) Nat. Struct. Biol. 4 305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matthews, R. (1993) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 62 653–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khorasanizadeh, S., Petrs, I. D. & Roder, H. (1996) Nat. Struct. Biol. 3 193–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matouschek, A., Kellis, J.T., Jr., Serrano, L., Bycroft, M. & Fersht, A. R. (1990) Nature 346 440–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oliveberg, M. (1997) Acc. Chem. Res. 31 765–772. [Google Scholar]