Abstract

The vast bacteriophage population harbors an immense reservoir of genetic information. Almost 2000 phage genomes have been sequenced from phages infecting hosts in the phylum Actinobacteria, and analysis of these genomes reveals substantial diversity, pervasive mosaicism, and novel mechanisms for phage replication and lysogeny. Here, we describe the isolation and genomic characterization of 46 phages from environmental samples at various geographic locations in the U.S. infecting a single Arthrobacter sp. strain. These phages include representatives of all three virion morphologies, and Jasmine is the first sequenced podovirus of an actinobacterial host. The phages also span considerable sequence diversity, and can be grouped into 10 clusters according to their nucleotide diversity, and two singletons each with no close relatives. However, the clusters/singletons appear to be genomically well separated from each other, and relatively few genes are shared between clusters. Genome size varies from among the smallest of siphoviral phages (15,319 bp) to over 70 kbp, and G+C contents range from 45–68%, compared to 63.4% for the host genome. Although temperate phages are common among other actinobacterial hosts, these Arthrobacter phages are primarily lytic, and only the singleton Galaxy is likely temperate.

Introduction

The bacteriophage population is vast, dynamic, old, and highly diverse genetically [1]. The majority of the reference-sequenced bacteriophages in the GenBank database [2] correspond to just five host phyla, the Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Cyanobacteria, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria. Within the Actinobacteria, most of the phages were isolated on Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155 (http://www.phagesdb.org), with smaller numbers on Gordonia [3, 4], Nocardia [5], Rhodococcus [6, 7] Streptomyces [8], and Tsukamurella [9] hosts. Comparative genomic analyses of 627 mycobacteriophages showed them to span considerable genetic variability reflecting a continuum of diversity but with highly uneven representation of different genomic types [10]. This contrasts with comparative genomics of 142 cyanobacteriophages grouped into ten lineages, which appear as discrete genetic populations [11].

To further investigate the genetic diversity of phages infecting Actinobacterial hosts, we explored the use of Arthrobacter sp. for the isolation of phages from environmental samples. Arthrobacter spp. are primarily soil organisms, some of which break down complex hydrocarbons, including hexavalent chromium, 4-chlorophenol, and various aromatic compounds such as pyridine and its derivatives; as such, they may have potential for use in bioremediation [12–14]. Arthrobacter spp. including A. arilaitensis are also components of smear-ripened cheese [15], and some Arthrobacter strains produce antibacterials such as penicillin derivatives [16]. Arthrobacter cells lack mycolic acids, and stain as gram-variable related to a transition from coccus to rod morphology during cell growth [17].

Several phages of Arthrobacter hosts have been isolated and used for bacterial strain typing [18–22] although only two have been sequenced: vB_ArS-ArV2 (ArV2) [23] and vB_ArtM-ArV1(ArV1) [24], both isolated on the environmental strain Arthrobacter sp. 68b. Here we describe the isolation and characterization of 46 phages infecting Arthrobacter sp. ATCC 21022 [25]. They are genomically diverse, but share no nucleotide sequence similarity with other phages infecting actinobacterial hosts including the mycobacteriophages.

Results and discussion

Arthrobacter phage isolation

Forty-six phages were isolated from soil samples using Arthrobacter sp. ATCC21022 as host (Table 1), one of which (Gordon) was isolated by direct plating of processed environmental samples onto an Arthrobacter lawn. The others were obtained by enrichment as described previously [26]. Phages were isolated by students in the Phage Hunters Integrating Research and Education (PHIRE) [27] at the University of Pittsburgh and Science Education Alliance-Phage Hunters Advancing Genomics and Evolutionary Science (SEA-PHAGES) [28] program, from nine institutions: Baylor University, Bucknell University, Cabrini University, Carnegie Mellon University, Lehigh University, Saint Joseph’s University, University of North Texas, Western Kentucky University, and University of Wisconsin-River Falls. Most phages were isolated from samples collected near these universities (S1 Fig and S1 Table). Phages were identified as plaques on lawns of Arthrobacter ATCC 21022, plaque purified, amplified, and genomic DNA was extracted as described previously [29]. All of the phages form clear plaques, with the exception of Galaxy that forms turbid plaques.

Table 1. Forty-six Arthrobacter phages.

| Phage | Cluster | GenBank Acc. no. | Genome Length(bp) | %GC | # genes | Virion Morphology | Structure of Genome Ends | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bennie | AK | KU160640 | 43,075 | 61.4 | 62 | Sipho | 13 base 3' | South Park, PA |

| DrRobert | AK | KU160643 | 42,601 | 60.6 | 59 | Sipho | 13 base 3' | Pittsburgh, PA |

| Glenn | AK | KU160645 | 44,389 | 60.8 | 64 | Sipho | 13 base 3' | Pittsburgh, PA |

| HunterDalle | AK | KU160648 | 43,336 | 61.6 | 60 | Sipho | 13 base 3' | Laurel Springs, NJ |

| Immaculata | AK | KU160649 | 43,661 | 61 | 62 | Sipho | 13 base 3' | Immaculata, PA |

| Joann | AK | KU160652 | 44,183 | 60.7 | 63 | Sipho | 13 base 3' | Clayton, OK |

| Korra | AK | KU160653 | 43,707 | 61.1 | 60 | Sipho | 13 base 3' | Bethel Park, PA |

| Preamble | AK | KU160659 | 43,374 | 60.7 | 64 | Sipho | 13 base 3' | Radnor, PA |

| Pumancara | AK | KU160661 | 42,830 | 61.7 | 61 | Sipho | 13 base 3' | Pittsburgh, PA |

| RAP15 | AK | KU160662 | 44,259 | 60.9 | 63 | Sipho | 13 base 3' | Pittsburgh, PA |

| Vulture | AK | KU160671 | 43,336 | 61.1 | 64 | Sipho | 13 base 3' | Marlton, NJ |

| Wayne | AK | KU160672 | 44,371 | 61.1 | 62 | Sipho | 13 base 3' | N. Huntingdon, PA |

| Laroye | AL | KU160654 | 60,005 | 64.8 | 99 | Sipho | Circularly permuted | Pittsburgh, PA |

| Salgado | AL | KU160664 | 59,807 | 64.6 | 99 | Sipho | Circularly permuted | Pittsburgh, PA |

| Circum | AM | KU160642 | 58,353 | 45.2 | 99 | Sipho3 | 9 base 3' | Denton, TX |

| Mudcat | AM | KU647628 | 59,443 | 45.1 | 95 | Sipho3 | 9 base 3' | Central City, KY |

| Decurro | AN | KT355471 | 15,524 | 60.2 | 26 | Sipho | 11 base 3' | Lewisburg, PA |

| Jessica | AN | KT355473 | 15,556 | 60.1 | 26 | Sipho | 11 base 3' | Lewisburg, PA |

| Maggie | AN | KU160655 | 15,556 | 60.1 | 26 | Sipho | 11 base 3' | Bethlehem, PA |

| Moloch | AN | KU160657 | 15,630 | 60 | 26 | Sipho | 11 base 3' | Pittsburgh, PA |

| Muttlie | AN | KU160658 | 15,524 | 60.2 | 26 | Sipho | 11 base 3' | West Chester, PA |

| Sandman | AN | KT355475 | 15,630 | 60 | 26 | Sipho | 11 base 3' | Seaside Heights, NJ |

| Stratus | AN | KU160667 | 15,630 | 60 | 26 | Sipho | 11 base 3' | Radnor, PA |

| Toulouse | AN | KU160670 | 15,319 | 60.3 | 25 | Sipho | 11 base 3' | Hudson, WI |

| TymAbreu | AN | KT783672 | 15,556 | 60.1 | 26 | Sipho | 11 base 3' | Hudson, WI |

| Yank | AN | KU160674 | 15,524 | 60.2 | 26 | Sipho | 11 base 3' | Lewisburg, PA |

| Brent | AO | KT365401 | 49,879 | 63.4 | 74 | Myo | Circularly permuted | Broomall, PA |

| Jawnski | AO | KU160651 | 49,419 | 63.4 | 73 | Myo | Circularly permuted | Pittsburgh, PA |

| BarretLemon | AO | KU647629 | 51,290 | 60.9 | 79 | Myo | Circularly permuted | Chippewa Falls, WI |

| Martha | AO | KU160656 | 51,027 | 61 | 77 | Myo | Circularly permuted | Pittsburgh, PA |

| Sonny | AO | KU160665 | 50,909 | 61.1 | 77 | Myo | Circularly permuted | Pittsburgh, PA |

| TaeYoung | AO | KU160668 | 50,999 | 61 | 78 | Myo | Circularly permuted | Pittsburgh, PA |

| Tank | AP | KU160669 | 67,592 | 62.9 | 105 | Sipho | 589 base Direct terminal rpt1 | Philadelphia, PA |

| Wilde | AP | KU160673 | 68,203 | 62.9 | 109 | Sipho | 589 base Direct terminal rpt | Montclair, NJ |

| Amigo | AQ | KU160638 | 59,173 | 52.9 | 86 | Sipho | 1584 Direct terminal rpt | Spring, Texas |

| Anansi | AQ | KU160639 | 58,848 | 53 | 86 | Sipho | 1584 Direct terminal rpt | Phoenixville, PA |

| Gorgeous | AQ | KU160647 | 58,979 | 53 | 86 | Sipho | 1584 Direct terminal rpt | Lafayette, Hills PA |

| Rings | AQ | KU160663 | 59,167 | 53 | 86 | Sipho | 1584 Direct terminal rpt | Radnor, PA |

| SorJuana | AQ | KU160666 | 58,979 | 53 | 86 | Sipho | 1584 Direct terminal rpt | Royersford, PA |

| KellEzio | AT | KU647626 | 58,871 | 63.3 | 99 | Sipho | unknown2 | Burkesville, KY |

| Kitkat | AT | KU647627 | 58,560 | 63.4 | 100 | Sipho | unknown2 | Greenbrae, CA |

| CapnMurica | AU | KU160641 | 58,159 | 49.6 | 88 | Sipho | 9 base 3' | Pittsburgh, PA |

| Gordon | AU | KU160646 | 58,279 | 49.8 | 89 | Sipho | 9 base 3' | South Park, PA |

| PrincessTrina | AR | KU160660 | 70,265 | 61.6 | 112 | Myo | Circularly permuted | Laurel Springs, NJ |

| Galaxy | Singleton | KU160644 | 37,809 | 68.4 | 65 | Sipho | 12 base 3' | Harmony, PA |

| Jasmine | Singleton | KU160650 | 46,723 | 45.9 | 58 | Podo | 1330 Direct terminal rpt | Pittsburgh, PA |

1right end is clear, left end is ambiguous

295% of sequencing reads align to reverse strand

3prolate head

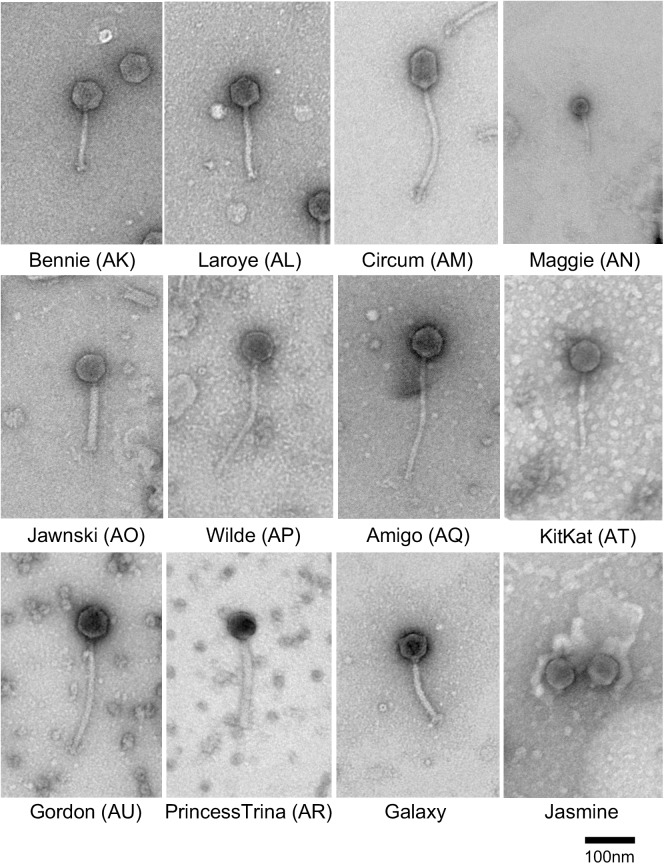

Virion morphologies

Phage particles were observed by transmission electron microscopy with negative staining (Fig 1). Most have siphoviral morphologies with non-contractile, flexible tails, ranging in length from 111.2 (± 11.0) to 242.3 (± 13.3) nm, and isometric heads ranging in size from 55.8 (± 4.0) to 61.4 (± 2.4) nm. Two of the siphoviruses (Circum and Mudcat) have prolate heads with length of 73.7 (± 1.3) nm x width of 50.5 (± 2.2) nm (Fig 1, S2 Table). Seven of the phages (Brent, Jawnski, Martha, Sonny, TaeYoung, BarretLemon, and PrincessTrina) have myoviral morphologies with a rigid tail and a tail sheath similar in appearance to P2-like [30] or Mu-like [31] myoviral phages infecting E. coli and other Enterobacteria. Myoviral phages of other Actinobacterial hosts are less common than siphoviruses but include the Cluster C mycobacteriophages [32] and the singleton Rhodococcus phage E3 [33]. Interestingly, Jasmine has a podoviral morphology with a head diameter of 59.8 (± 2.9) nm and a short stubby tail of 10.3 (± 0.9) nm (Fig 1). Two phages of Arthrobacter have been previously described with similar morphologies [20] but their genomes have yet to be sequenced, and to our knowledge, these are the only podoviruses of Actinobacterial hosts among over 1,000 sequenced phages that been examined morphologically.

Fig 1. Arthrobacter virion morphologies.

Electron micrographs of representative Arthrobacter phages. Scale bar corresponds to 100 nm.

Arthrobacter phage genometrics

The Arthrobacter phage genomes were sequenced and putative gene locations and functions were assigned based on bioinformatic analyses as described previously [10, 32, 34]. Genome lengths range considerably, from 15,319 bp (Toulouse) to 70,265 bp (PrincessTrina), with an average genome length of 45,832 bp (Table 1). The G+C contents span a broad range, from 45.1% (Mudcat) to 68.4% (Galaxy), such that the G+C content for many of the phages is substantially different from the Arthrobacter sp. ATCC 21022 host (63.4%) [25]. The genome termini vary considerably: many have cohesive ends with 3’ single stranded DNA extensions of 9–13 bases, some are circularly permuted and terminally redundant, and others have a direct terminal repeat ranging from 589 bp to 1584 bp long (Table 1). For two genomes, KellEzio and Kitkat, the ends could not be readily determined, but they are likely circularly permuted (manuscript in preparation). For these and the other circularly permuted terminally redundant genomes the sequences were linearized at positions near the 5’ ends of the predicted terminase genes.

Arthrobacter phage cluster assignments

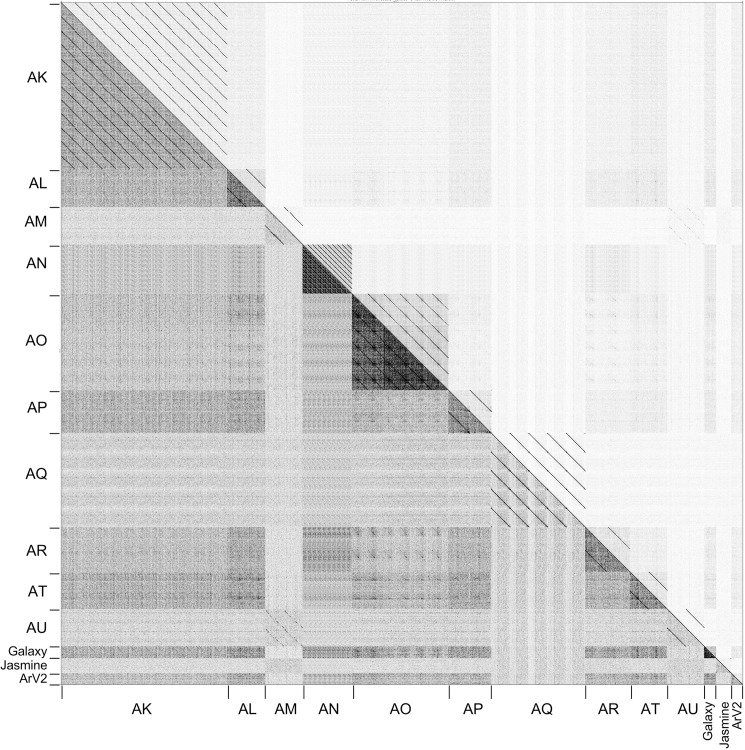

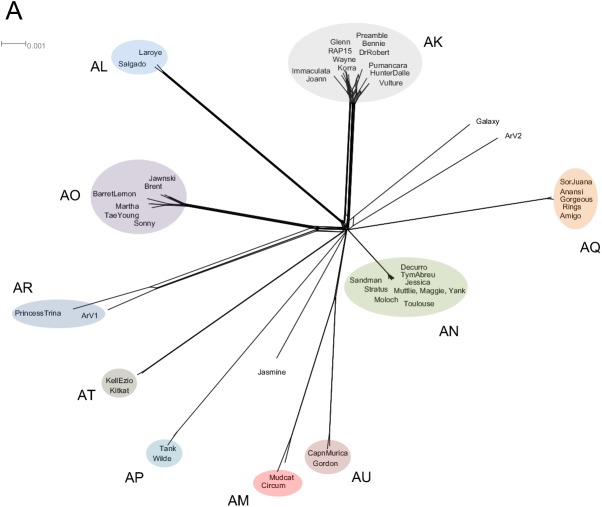

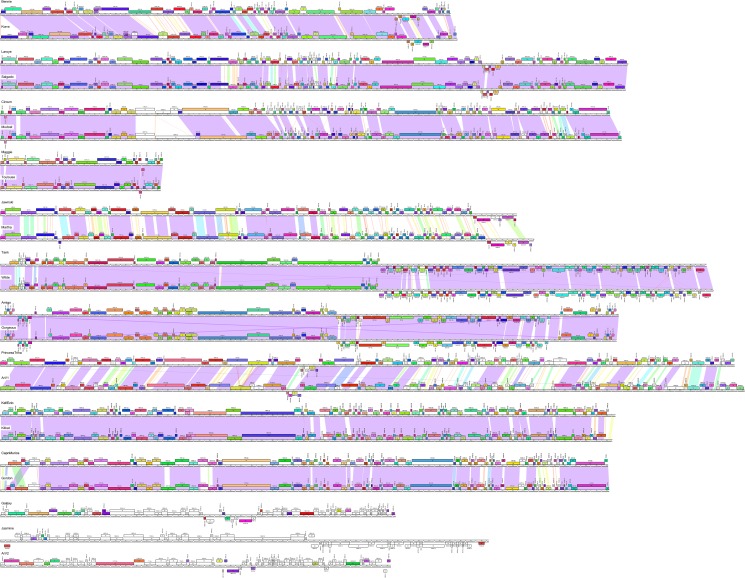

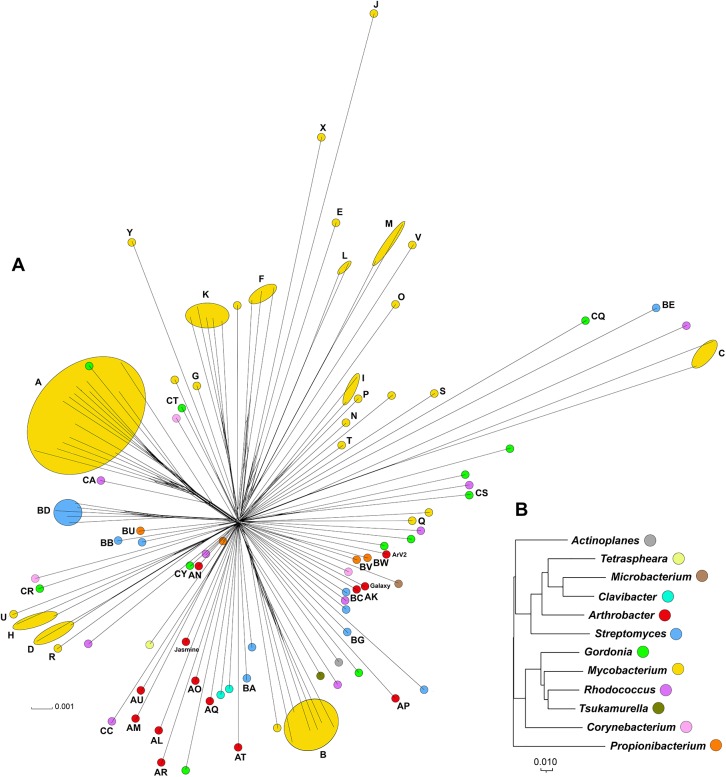

Dotplot comparison of Arthrobacter phage genomes shows distinct lineages with some phages more closely related to some than to others (Fig 2). Using this information, together with a gene content-based phylogeny (Fig 3), average nucleotide identity (ANI) values (S3 Table), pairwise genome alignments (Fig 4) and similar clustering parameters to those described previously [29, 32], these phages group into ten distinct clusters (AK–AU) and two singletons (Galaxy and Jasmine) (Table 1). The previously described phage, ArV1, clusters with PrincessTrina (Cluster AR); phage ArV2 is a singleton (Table 1, Fig 2). We note that phages in Cluster AM and AU share some observable nucleotide similarity in the Dotplot comparison (Fig 2), although their shared ANI values are below 0.6 (S3 Table); they also have a common branch in the network gene-content phylogeny (Fig 2) corresponding to them sharing approximately 30% of their genes using amino acid sequence comparisons. However, they are sufficiently different to warrant grouping into the separate Clusters AM and AU. None of the clusters warrant subdivision based on ANI values (S3 Table).

Fig 2. Nucleotide sequence comparison of Arthrobacter phages.

Dot Plot of Arthrobacter phage genomes displayed using Gepard [35]. Individual genome sequences were concatenated into a single file arranged such that related genomes were adjacent to each other. The assignment of clusters is shown along both the left and bottom.

Fig 3. Splitstree representation of Arthrobacter phages and average nucleotide comparisons of Cluster AO Arthrobacter phages.

All Arthrobacter phage predicted proteins were assorted into 1052 phams according to shared amino acid sequence similarities. Each genome was then assigned a value reflecting the presence or absence of a pham member, and the genomes were compared and displayed using Splitstree [36]. Cluster and subcluster assignments derived from the dot plot and ANI analyses are annotated. The scale bar indicates 0.001 substitutions/site.

Fig 4. Pairwise alignment of clustered Arthrobacter phages.

The genomes of 23 Arthrobacter phages are shown. Pairwise nucleotide sequence similarity is displayed by color-spectrum coloring between the genomes, with violet as most similar and red as least similar. Genes are shown as boxes above (transcribed rightwards) and below (transcribed leftwards) each genome line; boxes are colored according to the gene phamilies they are assigned [29]. Maps were generated using Phamerator and its database Actinobacteriophage_692.

Arthrobacter phage genome organizations

General genomic features

The ten clusters and singletons Galaxy and Jasmine display a variety of genome organizations, reflecting variations on common architectural themes seen in other phages of the order Caudovirales. In general, the virion structure and assembly genes are organized with typical syntenic arrangement–terminase, portal, capsid maturation protease, scaffolding protein, major capsid protein, head-tail connectors, major tail subunit, tail chaperone proteins, tape measure protein, and minor tail proteins [32]–but are compactly organized in some genomes (e.g. Cluster AM) and are interrupted by non-structural genes in others (e.g. Cluster AL). In most of the genomes, the lytic functions are encoded immediately downstream of the virion genes, the exceptions being the Cluster AM and AU phages where the lytic gene is located upstream of the terminase, and in the Cluster AT phages, where it is between the terminase and capsid maturation protease genes; the remaining parts of the genomes include DNA metabolism genes and predicted regulatory functions. Galaxy is the only phage to encode an integrase, suggesting this it is temperate. Collectively, 62% of genes in these phages have unknown functions, and we note that the singletons Galaxy and Jasmine are replete with orphams, genes without homologues elsewhere in the Actinobacteriophages. We will briefly discuss the features of each cluster, and representative genomes maps are shown in Figs 5–15.

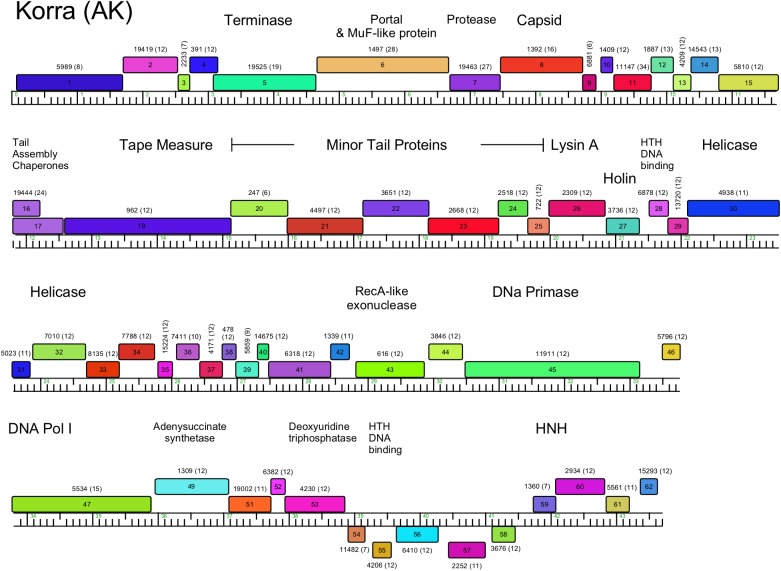

Fig 5. Genome organization of Arthrobacter phage Korra, Cluster AK.

The genome of Arthrobacter phage Korra is shown with predicted genes depicted as boxes either above (rightwards-expressed) or below (leftwards-expressed) the genome. Genes are colored according to the phamily designations using Phamerator and database Actinobacteriophage_692, with the phamily number shown above each gene with the number of phamily members in parentheses.

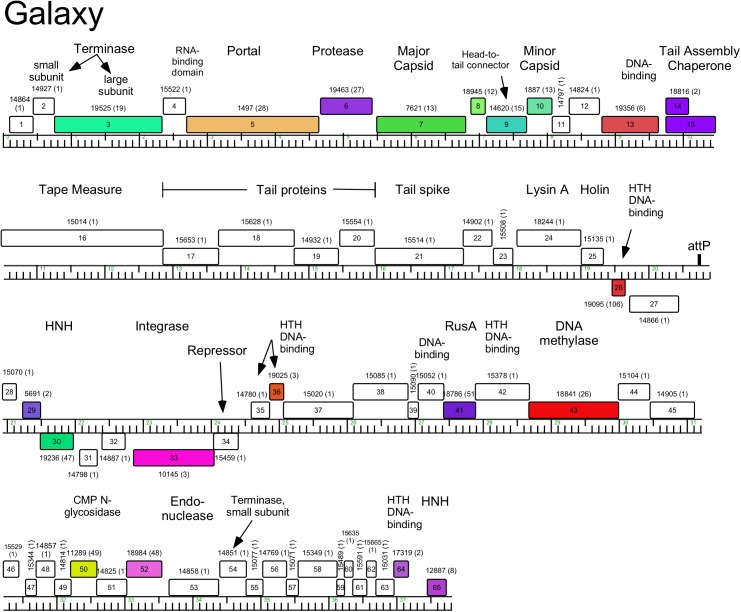

Fig 15. Genome organization of Arthrobacter phage Galaxy, Singleton.

See Fig 5 for details.

Cluster AK

The twelve Cluster AK phages (Table 1) are related to each other (Figs 2–4), with the virion genes in the left part of the genome and non-structural genes in the right part (Fig 5, S2 Fig). All genes are transcribed rightwards, with the exception of five leftwards-transcribed genes near the right end, one of which is a putative DNA binding protein (Fig 5). The portal and a Mu F-like protein are fused as a single gene (6) as shown in Fig 5.

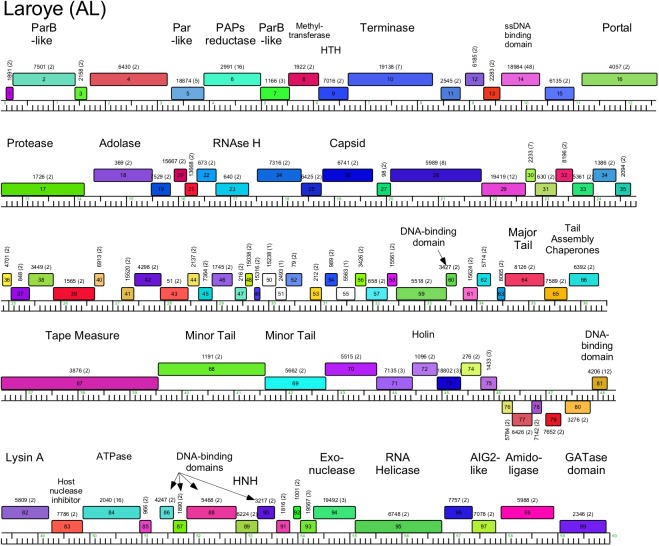

Cluster AL

The two Cluster AL genomes are closely related and differ by 7–8 small insertions or replacements in the right portion of the genomes (Fig 6, S3 Fig). The genomes have been bioinformatically linearized 6.7 kbp upstream of the terminase large subunit gene, where there is a small non-coding gap. The genome organizations are unusual in that, although the virion structure and assembly genes have the canonical order, there are numerous and sometimes quite large insertions between them (Fig 6, S3 Fig). For example, in Laroye there are five genes inserted between the terminase large subunit (10) and portal genes (16), eight genes are inserted between the protease (17) and major capsid (26) genes, and 37 genes are found between the major capsid subunit (26) and major tail subunit gene (64) (where there are typically 5–6 head-tail connector genes). Although genes coding for ssDNA binding protein (14), adolase (18), RNase (23), and another DNA binding domain (60) are found in the insertions, most of the inserted genes are of unknown function. With these insertions, the virion structure genes span over 35 kbp, and more than 50% of the 60 kbp genome. The remaining parts of the genomes contain several genes whose functions can be predicted but are atypical in phage genomes, including an RNA helicase (95), an AIG2-like protein (gamma-glutamylcyclotransferase; 97), an amidoligase (98), and a GTPase domain protein (99).

Fig 6. Genome organization of Arthrobacter phage Laroye, Cluster AL.

See Fig 5 for details.

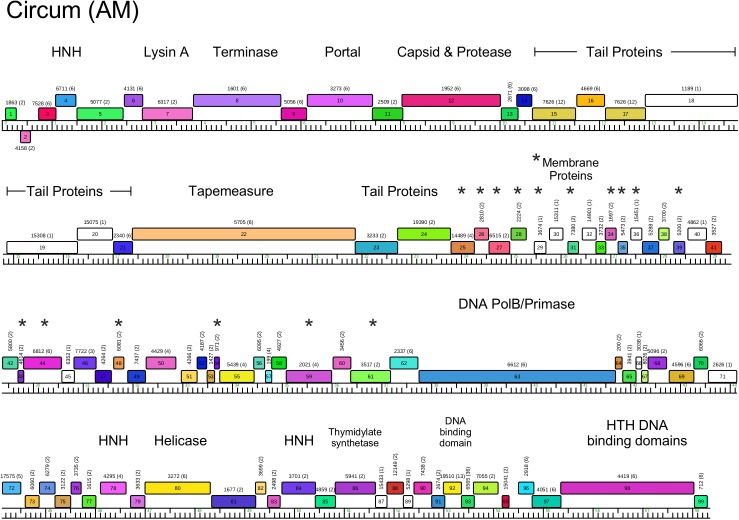

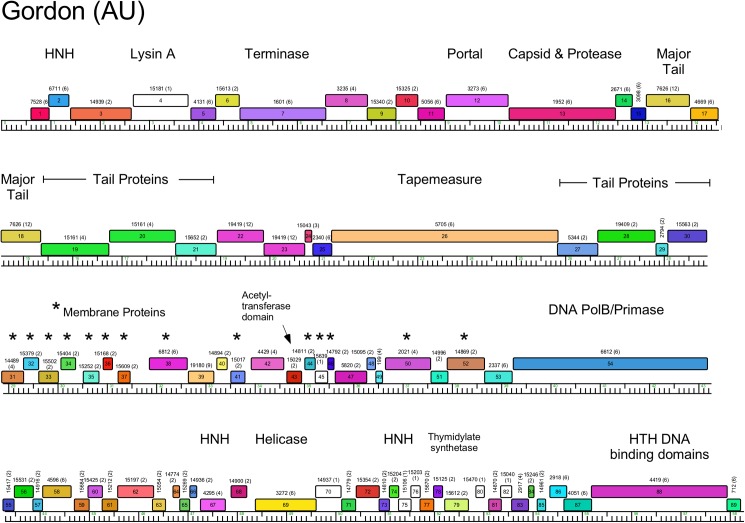

Clusters AM and AU

As noted above, the Cluster AM and AU genomes are distantly related, but share 25–30% of their genes, and the genome maps of Circum (AM) and Gordon (AU) are shown in Figs 7 and 8 and S4 Fig. The endolysin genes (Circum 7, Gordon 4) are located upstream of the terminase large subunit genes (Figs 7 and 8 and S3 Fig), as seen in Cluster A mycobacteriophages [37]. An unusual feature is the apparent fusion of the major capsid subunit and capsid maturation protease functions into a single gene (e.g. Circum 12). This is reminiscent of previously described fusion proteins, such as the capsid and scaffold genes in E. coli HK97 [38] and the scaffold and protease fusions in phage Lambda [39].

Fig 7. Genome organization of Arthrobacter phage Circum, Cluster AM.

See Fig 5 for details.

Fig 8. Genome organization of Arthrobacter phage Gordon, Cluster AU.

See Fig 5 for details.

Another unusual feature in the genomes of Cluster AM and AU phages is the presence of several small genes downstream of the tail genes, many of which encode putative membrane proteins. In Circum, 14 genes in the region of genes 25–61 encode proteins with between one and four membrane spanning domains, and 16 Gordon genes in the region of genes 31–52 (Figs 7 and 8) encode proteins with between one and five membrane spanning domains. The functions of these genes are unknown, but we note that similar arrays of putative membrane proteins are also present in Rhodococcus phages Pepy6 and Poco6 [6], and some of these share amino acid sequence similarity to Cluster AM and AU phages genes.

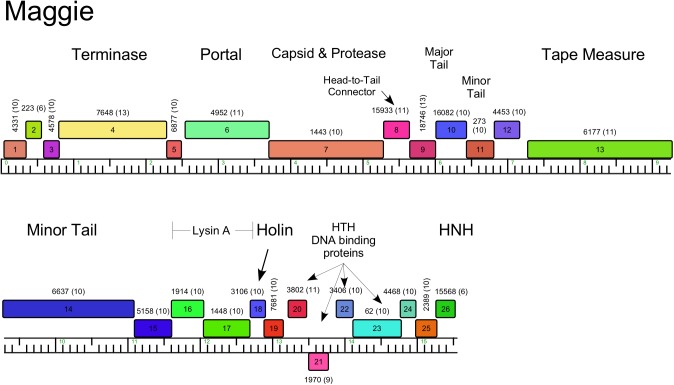

Cluster AN

The ten cluster AN phages are very closely related with small differences at their extreme left ends and some small regions of no sequence similarities (Fig 9 and S5 Fig). They have unusually small genomes for dsDNA phages, and are among the smallest of the Siphoviridae (Table 1). With an average of 15.5 kbp they are slightly larger than the smallest siphovirus genome reported, Rhodococcus phage RRH1 (14,270 bp) [40]. Much of the genome coding potential is occupied by the larger virion structure and assembly protein genes as shown in the map of Maggie (Fig 9), including a fused protease-capsid gene, similar to the gene fusions in Cluster AM and AU phages, but share little or no sequence similarity to Maggie gene 7. Interestingly, the small Rhodococcus phage RHH1 has a similarly fused gene, and the predicted protein is a distant relative (27% amino acid identity) of Maggie gp7 (Fig 9). The non-structural genes (20, 21, 22, 23), include those coding for four putative DNA binding proteins one of which (21) is the only leftwards transcribed gene. There are no genes coding for DNA metabolism functions, and these phages illustrate how few genes are required for propagation as a dsDNA tailed virus.

Fig 9. Genome organization of Arthrobacter phage Maggie, Cluster AN.

See Fig 5 for details.

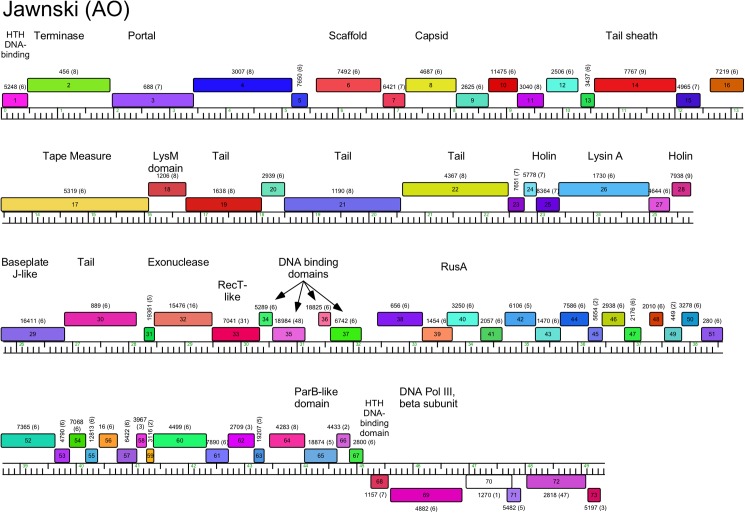

Cluster AO

The six Cluster AO phages share substantial genome similarity (Figs 2–4, S6 Fig) and a map of the Jawnski genome is shown in Fig 10. The virion structure and assembly genes are canonically ordered, but include a tail sheath and baseplate-like protein genes consistent with the contractile tail virion morphology (Fig 1); the lysis cassette appears to be inserted within the end of the tail gene operon (Fig 10). Jawnski codes for a RecET recombination system (genes 32 and 33) and a beta subunit of DNA Pol III (69), but most of the non-structural genes are of unknown function.

Fig 10. Genome organization of Arthrobacter phage Jawnski, Cluster AO.

See Fig 5 for details.

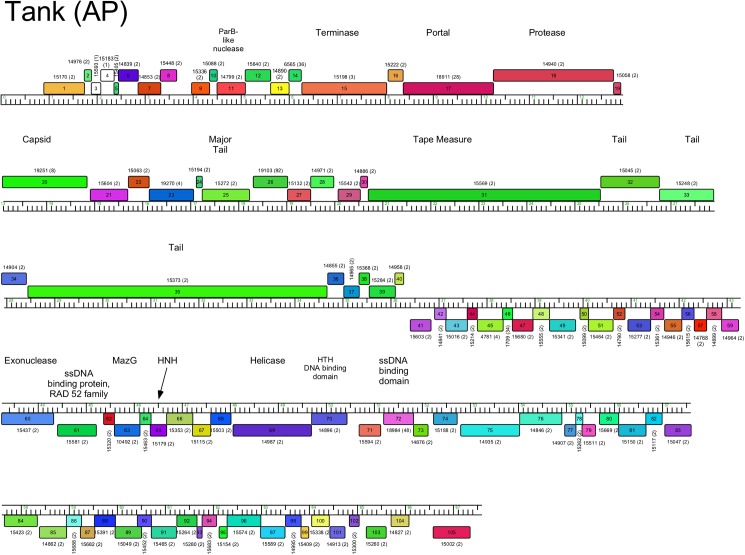

Cluster AP

The two Cluster AP genomes, Tank and Wilde, are closely related with 5–6 small insertions and deletions relative to each other (Fig 11, S7 Fig). The genomes have direct terminal repeats and the virion structure and assembly genes are canonically ordered but include an unusually long minor tail gene (35, 6.5 kbp), which atypically exceeds the length of the tape measure protein gene (31, 4.8 kbp). The genome is organized into rightwards- and leftwards transcribed genes (1–40 and 41–105, respectively), which converge close to the center of the genome (Fig 11, S7 Fig). Most of the leftwards-transcribed genes are of unknown function, with the exceptions of those coding for a single-stranded DNA binding protein (72), a DNA helicase (69), a MazG-like protein (63), and a Rad52_Rad22 family recombinase (61) that likely functions together with a putative exonuclease (60).

Fig 11. Genome organization of Arthrobacter phage Tank, Cluster AP.

See Fig 5 for details.

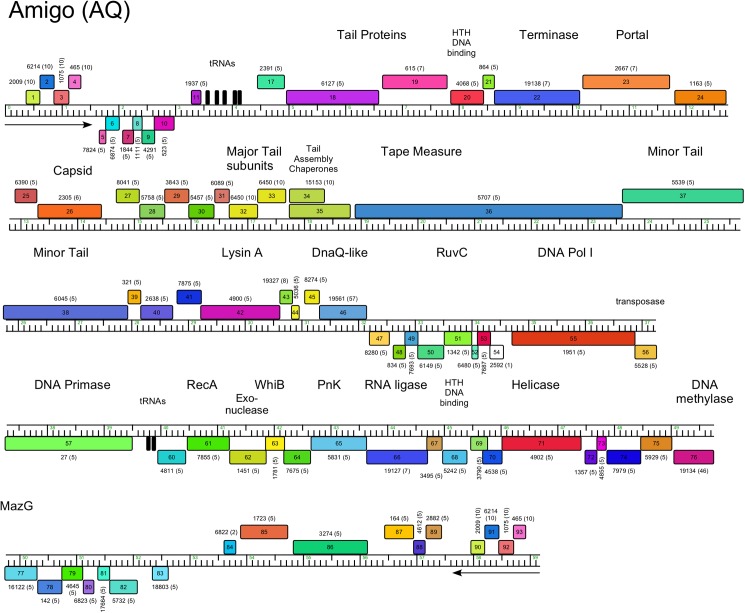

Cluster AQ

The five Cluster AQ genomes also have long terminal direct repeats (1.5 Kbp), but which include four protein-coding genes of unknown function (Fig 12, S8 Fig). The organization of the virion structure and assembly genes is somewhat non-canonical with two large predicted tail genes upstream of the terminase large subunit gene as shown in the map of Amigo (Fig 12). A long operon of leftwards-transcribed gene (47–83) includes many with predicted DNA metabolism functions including DNA Pol I (55), RuvC (51), DNA Primase (57), RecA (61), DNA Helicase (71) and a DNA Methylase (76), as well as an RNA Ligase (66) and a polynucleotide kinase (65). The Cluster AQ phages are the only Arthrobacter phages encoding tRNA genes (Fig 12), each having seven tRNA genes with the exception of phage Rings, which has lost one of these.

Fig 12. Genome organization of Arthrobacter phage Amigo, Cluster AQ.

See Fig 5 for details.

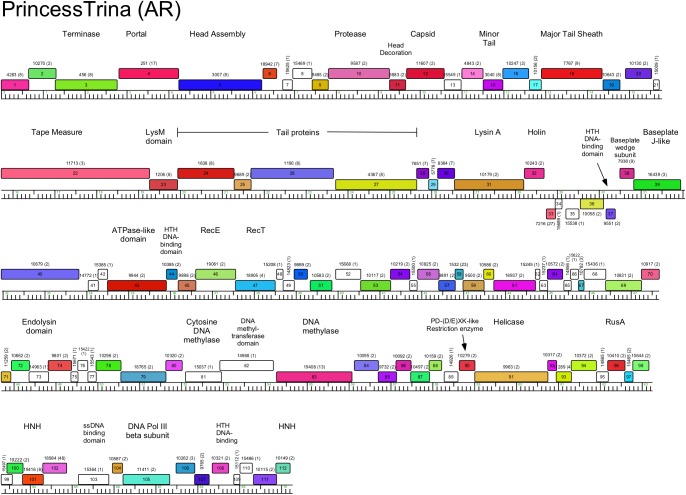

Cluster AR

PrincessTrina and the previously described ArV1 [24] constitute Cluster AR and they share extensive nucleotide sequence similarity. Apart from five leftwards-transcribed genes (33–37), all of the genes are transcribed rightwards (Fig 13). The virion structure and assembly genes are canonically ordered but include major tail sheath (PrincessTrina 18) and baseplate proteins (39) consistent with a contractile tail morphology; the lysis genes are located immediately downstream. Most of the non-structural genes are of unknown function, although several are predicted DNA metabolism genes including three putative DNA methylase genes (81, 82, 83); downstream, gene 90 codes for a PD-(D/E)XK-like restriction enzyme. Collectively, these genes may function as a restriction modification systems, or the DNA methylases could provide defense against host restriction systems.

Fig 13. Genome organization of Arthrobacter phage PrincessTrina, Cluster AR.

See Fig 5 for details.

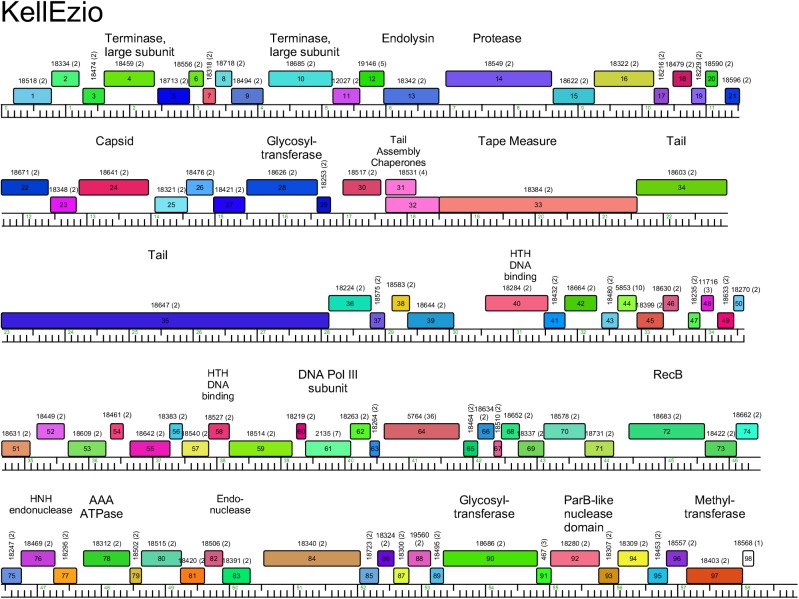

Cluster AT

The two Cluster AT phages, KitKat and KellEzio, are closely related with 4–5 insertions and deletions relative to each other. All genes are transcribed in the rightwards direction (Fig 14, S9 Fig), and there are several unusual organizational features. First, there is an uncommonly long tail gene (35; 5.1 kbp) that exceeds the length of the tape measure gene (33; 3 kbp) reflecting a similar feature in the Cluster AP phages. Second, the endolysin gene (13) is located between the terminase large subunit and capsid maturation protease genes, a position unique to these Cluster AT phages. Third, there are two genes coding for products related to terminase large subunit genes (4, 10). We also note the presence of two glycosyltranferase genes (28, 90), one of which (28) is located between the capsid subunit and major tail subunit genes.

Fig 14. Genome organization of Arthrobacter phage KellEzio, Cluster AT.

See Fig 5 for details.

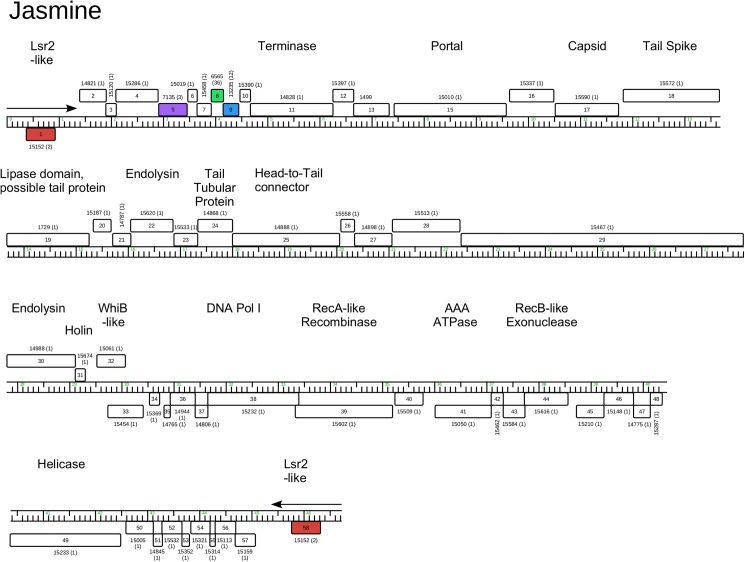

Singletons Galaxy and Jasmine

Galaxy’s genome is 37,809 bp with defined genome cohesive ends (Fig 15). Galaxy unusually has two genes (2, 54) predicted to code for terminase small subunits. We note that several of the structural genes (e.g. 5, 6, 7) have sequence similarity to some mycobacteriophages, a rare example of genes shared between mycobacteriophages and Arthrobacter phages. However, a high proportion of Galaxy genes are orphams (i.e. do not have relatives elsewhere in the Actinobacteriophage_692 database and shown as white boxes in Fig 15), a typical feature of singleton phages [10].

Galaxy is the only temperate phage among this group of Arthrobacter phages, and integrase (Int-Y) and repressor genes are predicted (33 and 34, respectively; Fig 15). Their organization is reminiscent of the mycobacteriophage integration-dependent immunity systems [41], but lack other common features such as recognizable degradation tags. Also, the attP site is not located within the repressor gene, and is positioned between genes 27 and 28 (coordinates 20,716–20,755) displaced by five genes from the integrase gene (33; Fig 15). The host genome contains two putative attB sites, located in identical tandemly repeated tRNAmet genes (AUT_13455 and AUT26_13460). However, we have been unsuccessful in isolating stable Galaxy lysogens in Arthrobacter sp. ATCC21022, a similar scenario to that reported for Arthrobacter phage ArV2, which also has putative integrase and repressor genes, but for which stable lysogens could not be recovered [23].

The Jasmine genome is notable for the large number of orpham genes that lack relatives in the Actinobacteria database (Fig 16); only four of the 58 predicted genes have close relatives. It is the only sequenced Actinobacteriophage with a podoviral morphology (Fig 1), and the genome has 1,330 bp terminal direct repeats. Interestingly, the terminal repeat contains the complete coding region for an Lsr2-like gene, a distant relative to the Lsr2-like genes in several mycobacteriophages [42]. Database comparisons suggest the virion structure and assembly genes are coded in the left part of the genome (genes 11–29), and include a putative tail spike gene (18; HHpred 99.81% probability score with the HK620 tail spike protein).

Fig 16. Genome organization of Arthrobacter phage Jasmine, Singleton.

See Fig 5 for details.

Lysis functions

Phage lysis functions are of interest as they provide insights into the host cell wall that must be compromised for cell lysis. Arthrobacter spp. lack mycolic acids in their cell walls, and thus the complete absence of lysin B genes encoding esterases cleaving the linkage of mycolic acids to the cell wall [43] is not surprising. However, endolysin genes can be identified in most of the phages, and in most cases a closely linked putative membrane protein likely acts as a holin. Notable exceptions are the Cluster AP phages (Tank, Wilde) for which we have not been able to identify an endolysin gene. We note that there are several small genes at the left ends of the genomes coding for putative membrane proteins that are holin candidates (3, 5, 6), and it is plausible that one of the genes between the leftmost direct terminal repeat and the terminase gene codes for an endolysin that is not discovered by database searches. The Arthrobacter phage endolysins are highly diverse and modular (Table 2), reflecting the complex structures reported for the mycobacteriophage endolysins [44]. Some have three domains (peptidase, amidase, and cell wall binding domains; Clusters AL, AO, AR), whereas others have only subsets of these (Table 2). The phages in Cluster AN (e.g. Maggie) have the lysis functions coded in two separate genes (e.g. Maggie 16 and 17); gp16 has the predicted peptidase activity and the amidase and cell wall binding activities are in gp17. We note that Jasmine has two genes (22 and 30) predicted to code for amidase functions, but 22 is located with the tail genes, and thus is more likely to be associated with phage infection than lysis.

Table 2. Endolysin domains.

| Endolysin domains | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster | Phage | Gene | Length (aa) | HHPred match | phage match in HHPred | CDD match |

| AK | Korra | 26 | 286 | N-acetylmuramoyl-L-ala amidase | Prophage Lambdaba02, E4e-26 | amidase-2, pfam01510 |

| AL | Laroye | 82 | 299 | L-Ala-D-Glu peptidase | Enterobacter phage T5 lysozyme, E6e-12 | no match |

| peptidoglycan hydrolase | Pseudomonas phage PhiKZ lysin,E1.3e-05 | no match | ||||

| peptidoglycan binding | Pseudomonas phage PhiKZ lysin, E4.9e-10 | PG-binding-1, pfam01471 | ||||

| AM | Circum | 5 | 309 | N-acetylmuramoyl-L-ala amidase | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, E1.8e-23 | M23 pfam01551 |

| AN | Maggie | 16 | 148 | peptidase_M23 | E1.2e-17 | M23, pfam01551 |

| 17 | 213 | N-acetylmuramoyl-L-ala amidase | Staphylococcus phage GH15, E2.4e-28 | PGRP, cI02712 | ||

| AO | Jawnski | 26 | 535 | N-acetylmuramoyl-L-ala peptidase | Streptococcus phage C1, E6e-15 | CHAP, pfam05257 |

| peptidoglycan hydrolase | Clostridium phage PHISM101, E7.7e-12 | no match | ||||

| peptidoglycan binding, amidase | Prophage Lambdaba02, E2.94e-23 | PGRP, cI02712 | ||||

| AP | Tank | none identified | ||||

| AQ | Amigo | 42 | 464 | Peptidoglycan peptidase | Streptococcus phage K, E1.5e-23 | NLPC_60, cI21534 |

| N-acetylmuramoyl-L-ala amidase | Enterobacteria phage T7, E4e-24 | PGRP, cd06583 | ||||

| AR | PrincessTrina | 31 | 551 | peptidase | Staphylococcus phage K, E8.4e-24 | NLPC_60, cI21534 |

| muramidase, peptidoglycan hydrolase | Clostridium phage PHISM101, E9.8e-38 | GH25 muramidase, pfam01183 | ||||

| peptidoglycan binding | Thermus thermophilus, E1.4e-19 | LysM (3 domains), cd00118 | ||||

| AT | KellEzio | 13 | 286 | peptidase | Staphylococcus phage K, E8.4e-24 | NLPC_60, cI21534 |

| N-acetylmuramoyl-L-ala amidase | Paenibacillus polymyxa hydrolase, E0.026 | no match | ||||

| AU | Gordon | 4 | 369 | amidase-2 domain, hydrolase | Staphylococcus phage GH15 lysin, E1.6e-23 | PGRP, cd06583 |

| peptidoglycan binding | Bacteriophage CP-7 lysozyme, E3.8e-14 | CPL-7 lysozyme, cI07020 (4 domains) | ||||

| Singleton | Galaxy | 24 | 312 | peptidoglycan binding, amidase | Enterobacteria phage T7 lysozyme, E2e-22 | PGRP, cI02712 |

| peptidoglycan binding | Thermus thermophilus, E7.6e-14 | LysM (2 domains), cd00118 | ||||

| Singleton | Jasmine | 22 | 270 | peptidoglycan binding, amidase | Staphylococcus phage GH15 lysin, E2.9e-21 | PGRP, cI02712 |

| 30 | 436 | Lysozyme-like muramidase | Staphylococcus aureus lysozyme, E8.8e-31 | NLPC_60, cI21534 | ||

Evolutionary relationships

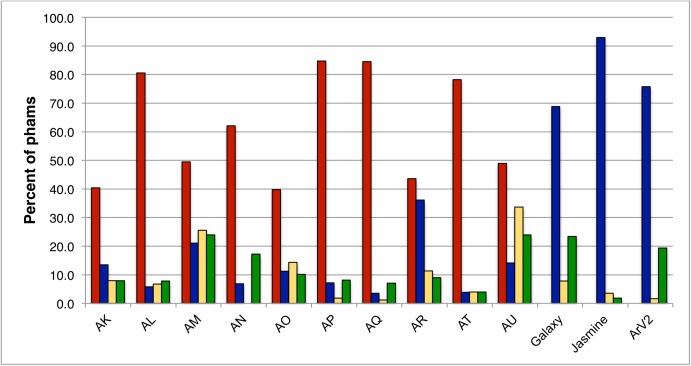

This collection of sequenced Arthrobacter phages provides insights into their spectrum of diversity relative to phages of other hosts, and how they are related specifically to phages of other Actinobacterial hosts. We note that the Arthrobacter phages distribute into a similar number of clusters and singletons (10, 2, respectively) identified when only 60 mycobacteriophage genomes had been sequenced, which formed 9 clusters and 5 singletons [32]. This reflects a greater overall diversity than seen with phages of Propionibacterium acnes [45]. To investigate this further we examined the distributions of gene phamilies (phams) representing groups of related proteins (see Material and Methods). The 3272 genes coding in the 48 genomes are grouped into a total of 1067 phams (S4 Table), 273 of which (26%) are orphams with no close relatives in the database; these are especially prevalent in the singletons Galaxy and Jasmine (Figs 15–17). The proportions of “cluster-associated” phams–those present in all cluster members but not present in any other cluster–varies substantially among the clusters (Fig 17) indicating the degrees to which the overall diversity varies among the clusters; it does not correlate with the numbers of cluster members (Fig 17).

Fig 17. Cluster diversity and inter-cluster relationships.

Intra-cluster diversity was determined by the percent of cluster-identifier phams (phams present in all members of a cluster and not found in phages of other clusters, red bars, not calculated for singleton phages), and the percent of orphams (phams present in only one phage, with no homologues in the database, blue bars). Inter-cluster relationships are shown as the proportion of phams present in each Arthrobacter phage cluster that are also present in at least one phage of another Arthrobacter cluster (yellow bars) or in at least one phage infecting a host other than Arthrobacter (green bars). The number of phages in each cluster is indicated in parentheses below the cluster name.

We also examined the extent to which the Arthrobacter phages are exchanging genes between clusters, or are relatively isolated. This is reflected in the numbers of phams in each cluster that are also present in at least one phage in another Arthrobacter cluster (Fig 17, S5 Table). For six clusters (AK, AL, AN, AP, AQ and AT) fewer than 10% of gene phamilies are in this category, reflecting relatively high levels of cluster isolation. Clusters AM and AU have more of these shared phams in part because they share about 25% of their genes with each other. Cluster AO and AR likewise share about 20% of their genes, and these relationships are also reflected in the shared branches in the Splitstree phylogeny shown in Fig 3. We note that similar cluster isolation measures for the mycobacteriophages range from 16–77% with an average of 60.8% [10].

Interestingly, the number of phams present in phages of Actinobacterial hosts other than Arthrobacter (103 of 1052 phams, 9.7%; S6 Table) is similar to the numbers shared between Arthrobacter phage clusters (Fig 17). Thus, the clusters are not only genetically well isolated from each other, but the genes that are shared are just as likely to be shared by non-Arthrobacter phages as they are by other Arthrobacter phages. We note, however, that there is considerable variation among the clusters in the patterns of shared genes. For example, the Cluster AU phages share more genes with other Arthrobacter phages than non-Arthrobacter phages, whereas in Cluster AN, AP, AQ and the singleton Galaxy, the opposite pattern is observed (Fig 17). Moreover, the genes are not shared with the phages of any one different host, but are broadly distributed, including phages of other Corynebacteriales hosts (Mycobacterium, Gordonia, Rhodococcus, Corynebacterium, Tsukamurella) as well as Streptomyces, Propionibacterium, and other Micrococcales hosts Clavibacter and Microbacterium (S6 Table). Over half of the shared genes (53/101) are in Actinobacteriophages other than those infecting Mycobacterium, even though those are only 10% of the non-Arthrobacter Actinobacteriophages. The most striking relationship is that between Clusters AM and AU with Rhodococcus phages Poco6 and Pepy6 (S10 Fig), with more than 20 shared genes distributed across the entire genome spans, most with more than 50% amino acid identity (S6 Table); there is also weak but evident nucleotide sequence similarity (S10 Fig).

Interestingly, these relationships do not obviously mirror the phylogeny of the actinobacterial hosts. Arthrobacter is more closely related to Streptomyces that it is to Mycobacteria, Gordonia, or Rhodococcus (Fig 18), but only nine Arthrobacter phage phams are shared with Streptomyces phages (of which there are 32 in the database used). In contrast, 36 Arthrobacter phage phams are shared with Rhodococcus phages (of which there are 16 in the database used). Although the numbers of phages available for these types of analyses are still small, there is little evidence of a correlation between shared gene content of representative phages from each actinobacteriophage cluster and phylogenetic proximity of their hosts (Fig 18, S7 Table). We also tested 21 Arthrobacter phages for their abilities to infect 29 different Actinobacterial hosts, including nine other Arthrobacter species (see Materials and Methods). None of the Arthrobacter phages tested infected any of these strains, and no mutants with expanded host range were identified. These narrow host preferences reflect those reported previously for ArV2 [24] and ArV1 [23].

Fig 18. Comparison of phage shared gene content and host phylogeny.

A. One representative phage genome from each cluster including singletons were assigned a value reflecting the presence or absence of each pham in the database, and the genomes were compared and displayed using Splitstree [36]. Clusters are labeled with the cluster name, and singleton phages isolated in Arthrobacter are identified; all others are singleton phages isolated in other hosts. Colors correspond to bacterial host genera in panel B. The scale bar indicates 0.001 substitutions/site. B. Phylogenetic tree derived from 16S rRNA sequences from representative bacteria from each phage host genus in the database. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7 [46] using the Neighbor-Joining method with gaps eliminated. The scale bar indicates 0.01 base substitutions per site. The 16S rRNA sequences (GenBank accession numbers in parentheses) were from Actinoplanes sp. SE50/110 (CP003170), Arthrobacter sp. ATCC 21022 (CP014196), Clavibacter michiganensis (AB299158), Corynebacterium vitaeruminis DSM 20294 (NR_121721), Gordonia terrae 3612 (CP016594), Microbacterium foliorum strain 122 (CP019892), M. smegmatis mc2 155 (Y08453), Propionibacterium acnes ATCC 11828 (CP003084), Rhodococcus erythropolis PR4 (AP008957), Streptomyces griseus strain DSM 40236 (AP009493), Tetraspheara remsis strain 3-M5-R-4 (DQ447774), Tsukamurella paurometabola DSM 20162 (NR_074458). This tree mirrors the phylogeny of 90 actinobacteria based on 16S rRNA gene sequences as described previously [47] but also includes Actinoplanes and Tetraspheara.

Concluding remarks

Here we have described 46 newly isolated phages of Arthrobacter sp. ATCC21022 and compared their genomic sequences. They are richly diverse in morphotype and genotype, with 12 distinct lineages forming ten clusters and two singletons. These clearly represent an under-sampling of the broader population-at-large of phages infecting this strain, and the diversity of the large collection of mycobacteriophages suggests that the sequenced Arthrobacter phage collection will need to be expanded 10-20-fold to reflect better their genomic diversity. Given the narrow host range of these phages, we also predict that phages isolated on other Arthrobacter strains will reveal phage genomic lineages not previously described. The dearth of temperate phages among those described here is somewhat surprising, as they represent the majority of phages isolated on M. smegmatis [10] and on Gordonia terrae (unpublished observations). Because all of these phages were isolated from similar environments, the relative preponderance of temperate and lytic phages appears to be a function of the host used for isolation, rather than different environmental parameters, although we note that metagenomic studies suggest that temperate phages are more prevalent in environments with higher bacterial densities [48]. The roles of the hosts in directing evolution of phage lifestyles remains obscure, but isolation and genomic characterization of large sets of phages on hosts within the Actinobacteria will hopefully illuminate this question.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and media

All phages were isolated on Arthrobacter species, ATCC strain 21022. Either LB media (L-agar base) or PYCa media (containing per 1 liter volume: 1.0 g Yeast extract, 15 g Peptone, 2.5 mL 40% Dextrose, and 4.5 ml 1M CaCl2) were used for phage isolation and amplification.

Arthrobacter phage isolation, propagation, and virion analysis

All phages were obtained from soil samples with permissions granted (S1 Table). For the soil enrichment protocol, 1–2 grams of soil were incubated at 30°C with Arthrobacter sp. in PYCa or LB medium supplemented with 1–4.5 mM CaCl2 a and Arthrobacter sp. host for 2–5 days. These enriched soil samples were filtered with 0.22 μm—0.45 μm filters and the filtrates were introduced to a pure culture of Arthrobacter sp. Some soil samples were not enriched with host bacteria prior to performing a plaque assay. For these samples, the soil samples were treated with phage buffer (10mM Tris-HCL, pH 7.5; 10mM MgSO4; 68.5mM NaCl; 1mM CaCl2), shaken vigorously, filtered, and plated directly on solid overlays containing 0.35% agar and Arthrobacter host and incubated at 30°C for 16–48 hours. For both the enriched soil samples and the direct soil samples, individual plaques were purified. Once plaque purified, high-titer Arthrobacter phage stocks and plate lysates were obtained using methods described previously for Mycobacterial hosts [26]. Phage particles were spotted onto formvar and carbon-coated 400 mesh copper grids, rinsed with distilled water and stained with 1% uranyl acetate. Images were taken using a FEI Morgagni transmission electron microscope. Measurements were performed on at least 3 particles for each phage.

Genome sequencing, annotation, and analysis

Arthrobacter phages were isolated, sequenced, and annotated in the PHIRE or SEA-PHAGES programs. Phage genomes were shotgun-sequenced using either 454, Ion Torrent, or Illumina platforms to at least 20-fold coverage. Shotgun reads were assembled de novo with Newbler versions 2.1 to 2.9. Assemblies were checked for low coverage or discrepant areas, and targeted Sanger reads were used to resolve weak areas and identify genome ends. Genomes were annotated using DNA Master (http://cobamide2.bio.pitt.edu), GLIMMER [49], GeneMark [50], BLAST, HHPred [51], and Phamerator [29]. Actinobacteriophage_692 is the Phamerator database used for the analyses of this project. Further analyses included Dot plot (Gepard) [35], Splitstree [36], kAlign [52], and TMHMM transmembrane helix prediction (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/). All genome sequences are publicly available at phagesdb.org and in GenBank.

Host range testing

High titer lysates of 21 Arthrobacter phages (Bennie, Joann, Korra, Pumancara, Wayne, Laroye, Salgado, Circum, Maggie, Moloch, Toulouse, Jawnski, Martha, Sonny, TaeYoung, Wilde, Amigo, KellEzio, Kitkat, Gordon,and Galaxy) were serially diluted in phage buffer and 10 μl of ten-fold dilutions were spotted onto 29 Actinobacteria hosts lawns prepared from the following strains: Arthrobacter atrocyaneus B-2883, Arthrobacter citreus B-1258, Arthrobacter globiformis B-2979, Arthrobacter globiformis B-2880, Arthrobacter humicola B-24479, Arthrobacter pascens B-2884, Arthrobacter viscosus B-1973, Arthrobacter viscosus B-1797, Arthrobacter sulfureus B-14730, Tsukamurella wrastlaviensis NRRL B-16958, Tsukamurella sunchanesis NRRL 24668, Tsukamurella pauramutabola NRRL 16960, Rhodococcus erythroplois NRRL 1574, M. smegmatis mc2155, Mycetocola saprophilus NRRL B-24119, Microbacterium hominus NRRL B-24220, Microbacterium foliorum NRRL B-24224, Microbacterium aerolatum NRRL B-24228, Kocuria species (Hatfull lab collection), Kocuria 68 (Dutton lab collection), Gordonia westfalica NRRL 16540, Gordonia terrae NRRL 3612, Gordonia rubripertincta NRRL 24152, Corynebacterium vitaeruminis ATCC 10234, Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 14020, Corynebacterium flavescens ATCC 10340, Brevibacterium samyangense NRRL B-41420, Brevibacterium fuscum NRRL B-14687, and Brachybacterium sp. 113 (Dutton lab collection). The plates were incubated at room temperature with the exception of M. smegmatis mc2155, which was incubated at 37°C, and Gordonia terrae and Microbacterium foliorum, which were incubated at 30°C. Plates were examined after 24 and 48 hours of incubation.

Supporting information

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(PDF)

(XLSX)

(NEX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Rachel Dutton for providing bacterial strains, and John Andersland at Western Kentucky University for electron microscopy. David Dunbar passed away before the submission of the final version of this manuscript. Graham F. Hatfull accepts responsibility for the integrity and validity of the data collected and analyzed.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files. The exception are the annotated sequenced files available at NCBI, accession numbers are listed in Table 1.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health GM116884 to GFH, Howard Hughes Medical Institute 54308198 to GFH, National Science Foundation 1247842 to TNM, and National Institutes of Health P20GM103436 to RAK and CAR.

References

- 1.Hendrix RW. Bacteriophages: evolution of the majority. Theor Popul Biol. 2002;61(4):471–80. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson DA, Clark K, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Sayers EW. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D32–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1030 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3965104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dyson ZA, Tucci J, Seviour RJ, Petrovski S. Lysis to Kill: Evaluation of the Lytic Abilities, and Genomics of Nine Bacteriophages Infective for Gordonia spp. and Their Potential Use in Activated Sludge Foam Biocontrol. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0134512 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134512 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4524720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu M, Gill JJ, Young R, Summer EJ. Bacteriophages of wastewater foaming-associated filamentous Gordonia reduce host levels in raw activated sludge. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13754 doi: 10.1038/srep13754 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4563357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khairnar K, Pal P, Chandekar RH, Paunikar WN. Isolation and characterization of bacteriophages infecting nocardioforms in wastewater treatment plant. Biotechnol Res Int. 2014;2014:151952 doi: 10.1155/2014/151952 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4129933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Summer EJ, Liu M, Gill JJ, Grant M, Chan-Cortes TN, Ferguson L, et al. Genomic and functional analyses of Rhodococcus equi phages ReqiPepy6, ReqiPoco6, ReqiPine5, and ReqiDocB7. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(2):669–83. Epub 2010/11/26. AEM.01952-10 [pii] doi: 10.1128/AEM.01952-10 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3020559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrovski S, Seviour RJ, Tillett D. Characterization and whole genome sequences of the Rhodococcus bacteriophages RGL3 and RER2. Archives of virology. 2013;158(3):601–9. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1530-5 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith MC, Hendrix RW, Dedrick R, Mitchell K, Ko CC, Russell D, et al. Evolutionary relationships among actinophages and a putative adaptation for growth in Streptomyces spp. J Bacteriol. 2013;195(21):4924–35. doi: 10.1128/JB.00618-13 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3807479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petrovski S, Seviour RJ, Tillett D. Genome sequence and characterization of the Tsukamurella bacteriophage TPA2. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(4):1389–98. Epub 2010/12/25. AEM.01938-10 [pii] doi: 10.1128/AEM.01938-10 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3067230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pope WH, Bowman CA, Russell DA, Jacobs-Sera D, Asai DJ, Cresawn SG, et al. Whole genome comparison of a large collection of mycobacteriophages reveals a continuum of phage genetic diversity. Elife. 2015;4:e06416 doi: 10.7554/eLife.06416 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4408529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gregory AC, Solonenko SA, Ignacio-Espinoza JC, LaButti K, Copeland A, Sudek S, et al. Genomic differentiation among wild cyanophages despite widespread horizontal gene transfer. BMC Genomics. 2016;17(1):930 doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3286-x ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5112629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camargo FA, Bento FM, Okeke BC, Frankenberger WT. Hexavalent chromium reduction by an actinomycete, arthrobacter crystallopoietes ES 32. Biological trace element research. 2004;97(2):183–94. Epub 2004/02/27. doi: 10.1385/BTER:97:2:183 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westerberg K, Elvang AM, Stackebrandt E, Jansson JK. Arthrobacter chlorophenolicus sp. nov., a new species capable of degrading high concentrations of 4-chlorophenol. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50 Pt 6:2083–92. Epub 2001/01/13. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-6-2083 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Loughlin EJ, Sims GK, Traina SJ. Biodegradation of 2-methyl, 2-ethyl, and 2-hydroxypyridine by an Arthrobacter sp. isolated from subsurface sediment. Biodegradation. 1999;10(2):93–104. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monnet C, Loux V, Gibrat JF, Spinnler E, Barbe V, Vacherie B, et al. The arthrobacter arilaitensis Re117 genome sequence reveals its genetic adaptation to the surface of cheese. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e15489 Epub 2010/12/03. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015489 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2991359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao B, Gupta RS. Phylogenetic framework and molecular signatures for the main clades of the phylum Actinobacteria. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews: MMBR. 2012;76(1):66–112. Epub 2012/03/07. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05011-11 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3294427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ward CM Jr., Claus GW. Gram characteristics and wall ultrastructure of Arthrobacter crystallopoietes during coccus-rod morphogenesis. J Bacteriol. 1973;114(1):378–89. ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC251776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casida LE, Liu KC. Arthrobacter globiformis and Its Bacteriophage in Soil. Applied microbiology. 1974;28(6):951–9. Epub 1974/12/01. ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC186862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Einck KH, Pattee PA, Holt JG, Hagedorn C, Miller JA, Berryhill DL. Isolation and characterization of a bacteriophage of Arthrobacter globiformis. J Virol. 1973;12(5):1031–3. Epub 1973/11/01. ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC356733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown DR, Holt JG, Pattee PA. Isolation and characterization of Arthrobacter bacteriophages and their application to phage typing of soil arthrobacters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;35(1):185–91. Epub 1978/01/01. ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC242800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Achberger EC, Kolenbrander PE. Isolation and characterization of morphogenetic mutants of Arthrobacter crystallopoietes. J Bacteriol. 1978;135(2):595–602. Epub 1978/08/01. ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC222420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ostle AG, Holt JG. Elution and inactivation of bacteriophages on soil and cation-exchange resin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979;38(1):59–65. Epub 1979/07/01. ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC243435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simoliunas E, Kaliniene L, Stasilo M, Truncaite L, Zajanckauskaite A, Staniulis J, et al. Isolation and characterization of vB_ArS-ArV2—first Arthrobacter sp. infecting bacteriophage with completely sequenced genome. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e111230 Epub 2014/10/22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111230 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4205034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaliniene L, Simoliunas E, Truncaite L, Zajanckauskaite A, Nainys J, Kaupinis A, et al. Molecular analysis of Arthrobacter myovirus vB_ArtM-ArV1: we blame it on the tail. J Virol. 2017. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00023-17 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russell DA, Hatfull GF. Complete Genome Sequence of Arthrobacter sp. ATCC 21022, a Host for Bacteriophage Discovery. Genome announcements. 2016;4(2). doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00168-16 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4807237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarkis GJ, Hatfull GF. Mycobacteriophages. Methods Mol Biol. 1998;101:145–73. Epub 1999/01/28. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-471-2:145 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanauer DI, Jacobs-Sera D, Pedulla ML, Cresawn SG, Hendrix RW, Hatfull GF. Inquiry learning. Teaching scientific inquiry. Science. 2006;314(5807):1880–1. doi: 10.1126/science.1136796 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jordan TC, Burnett SH, Carson S, Caruso SM, Clase K, DeJong RJ, et al. A broadly implementable research course in phage discovery and genomics for first-year undergraduate students. mBio. 2014;5(1):e01051–13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01051-13 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pope WH, Jacobs-Sera D, Russell DA, Peebles CL, Al-Atrache Z, Alcoser TA, et al. Expanding the diversity of mycobacteriophages: insights into genome architecture and evolution. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e16329 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016329 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3029335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bebeacua C, Tremblay D, Farenc C, Chapot-Chartier MP, Sadovskaya I, van Heel M, et al. Structure, adsorption to host, and infection mechanism of virulent lactococcal phage p2. J Virol. 2013;87(22):12302–12. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02033-13 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3807928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.To CM, Eisenstark A, Toreci H. Structure of mutator phage Mu1 of Escherichia coli. J Ultrastruct Res. 1966;14(5):441–8. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hatfull GF, Jacobs-Sera D, Lawrence JG, Pope WH, Russell DA, Ko CC, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of 60 Mycobacteriophage genomes: genome clustering, gene acquisition, and gene size. Journal of molecular biology. 2010;397(1):119–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.011 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2830324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salifu SP, Valero-Rello A, Campbell SA, Inglis NF, Scortti M, Foley S, et al. Genome and proteome analysis of phage E3 infecting the soil-borne actinomycete Rhodococcus equi. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2013;5(1):170–8. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12028 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cresawn SG, Pope WH, Jacobs-Sera D, Bowman CA, Russell DA, Dedrick RM, et al. Comparative genomics of Cluster O mycobacteriophages. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0118725 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118725 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4351075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krumsiek J, Arnold R, Rattei T. Gepard: a rapid and sensitive tool for creating dotplots on genome scale. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(8):1026–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm039 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kloepper TH, Huson DH. Drawing explicit phylogenetic networks and their integration into SplitsTree. BMC evolutionary biology. 2008;8:22 Epub 2008/01/26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-22 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2253509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hatfull GF. The secret lives of mycobacteriophages. Adv Virus Res. 2012;82:179–288. Epub 2012/03/17. B978-0-12-394621-8.00015–7 [pii] doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394621-8.00015-7 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Veesler D, Khayat R, Krishnamurthy S, Snijder J, Huang RK, Heck AJ, et al. Architecture of a dsDNA viral capsid in complex with its maturation protease. Structure. 2014;22(2):230–7. Epub 2013/12/24. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.11.007 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3939775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hendrix RW, Casjens S. Bacteriophage lambda and its genetic neighborhood In: Abedon STC, R. L., editor. The Bacteriophages. Oxford University Press, New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petrovski S, Dyson ZA, Seviour RJ, Tillett D. Small but sufficient: the Rhodococcus phage RRH1 has the smallest known Siphoviridae genome at 14.2 kilobases. Journal of virology. 2012;86(1):358–63. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05460-11 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3255915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Broussard GW, Oldfield LM, Villanueva VM, Lunt BL, Shine EE, Hatfull GF. Integration-dependent bacteriophage immunity provides insights into the evolution of genetic switches. Molecular cell. 2013;49(2):237–48. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.11.012 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3557535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pedulla ML, Ford ME, Houtz JM, Karthikeyan T, Wadsworth C, Lewis JA, et al. Origins of highly mosaic mycobacteriophage genomes. Cell. 2003;113(2):171–82. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Payne K, Sun Q, Sacchettini J, Hatfull GF. Mycobacteriophage Lysin B is a novel mycolylarabinogalactan esterase. Mol Microbiol. 2009;73(3):367–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06775.x . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Payne KM, Hatfull GF. Mycobacteriophage endolysins: diverse and modular enzymes with multiple catalytic activities. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e34052 Epub 2012/04/04. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034052 PONE-D-12-02640 [pii]. ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3314691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marinelli LJ, Fitz-Gibbon S, Hayes C, Bowman C, Inkeles M, Loncaric A, et al. Propionibacterium acnes Bacteriophages Display Limited Genetic Diversity and Broad Killing Activity against Bacterial Skin Isolates. mBio. 2012;3(5). Epub 2012/09/28. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00279-12 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–4. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verma M, Lal D, Kaur J, Saxena A, Kaur J, Anand S, et al. Phylogenetic analyses of phylum Actinobacteria based on whole genome sequences. Res Microbiol. 2013;164(7):718–28. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2013.04.002 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knowles B, Silveira CB, Bailey BA, Barott K, Cantu VA, Cobian-Guemes AG, et al. Lytic to temperate switching of viral communities. Nature. 2016;531(7595):466–70. doi: 10.1038/nature17193 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salzberg SL, Delcher AL, Kasif S, White O. Microbial gene identification using interpolated Markov models. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26(2):544–8. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Besemer J, Borodovsky M. GeneMark: web software for gene finding in prokaryotes, eukaryotes and viruses. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W451–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki487 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1160247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soding J, Biegert A, Lupas AN. The HHpred interactive server for protein homology detection and structure prediction. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W244–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki408 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1160169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lassmann T, Sonnhammer EL. Kalign—an accurate and fast multiple sequence alignment algorithm. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:298 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-298 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1325270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(PDF)

(XLSX)

(NEX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files. The exception are the annotated sequenced files available at NCBI, accession numbers are listed in Table 1.