Abstract

We have generated a molecular taxonomy of lung carcinoma, the leading cause of cancer death in the United States and worldwide. Using oligonucleotide microarrays, we analyzed mRNA expression levels corresponding to 12,600 transcript sequences in 186 lung tumor samples, including 139 adenocarcinomas resected from the lung. Hierarchical and probabilistic clustering of expression data defined distinct subclasses of lung adenocarcinoma. Among these were tumors with high relative expression of neuroendocrine genes and of type II pneumocyte genes, respectively. Retrospective analysis revealed a less favorable outcome for the adenocarcinomas with neuroendocrine gene expression. The diagnostic potential of expression profiling is emphasized by its ability to discriminate primary lung adenocarcinomas from metastases of extra-pulmonary origin. These results suggest that integration of expression profile data with clinical parameters could aid in diagnosis of lung cancer patients.

Carcinoma of the lung claims more than 150,000 lives every year in the United States, thus exceeding the combined mortality from breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers (1). The current lung cancer classification is based on clinicopathological features. More fundamental knowledge of the molecular basis and classification of lung carcinomas could aid in the prediction of patient outcome, the informed selection of currently available therapies, and the identification of novel molecular targets for chemotherapy. The recent development of targeted therapy against the Abl tyrosine kinase for chronic myeloid leukemia illustrates the power of such biological knowledge (2).

Lung carcinomas are usually classified as small-cell lung carcinomas (SCLC) or non-small-cell lung carcinomas (NSCLC). Neuroendocrine features, defined by microscopic morphology and immunohistochemistry, are hallmarks of the high-grade SCLC and large-cell neuroendocrine tumors and of intermediate/low-grade carcinoid tumors (3). NSCLC is histopathologically and clinically distinct from SCLC, and is further subcategorized as adenocarcinomas, squamous cell carcinomas, and large-cell carcinomas, of which adenocarcinomas are the most common (3).

The histopathological subclassification of lung adenocarcinoma is challenging. In one study, independent lung pathologists agreed on lung adenocarcinoma subclassification in only 41% of cases (4). However, a favorable prognosis for bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC), a histological subclass of lung adenocarcinoma, argues for refining such distinctions (5, 6). In addition, metastases of nonlung origin can be difficult to distinguish from lung adenocarcinomas (7, 8).

The development of microarray methods for large-scale analysis of gene expression (9–12) makes it possible to search systematically for molecular markers of cancer classification and outcome prediction in a variety of tumor types (13–19). Currently, the only effective prognostic indicator for NSCLC in clinical use is surgical–pathological staging (20). However, the simultaneous analysis of a large number of independent clinical markers may offer a powerful adjunct approach in surgical–pathological staging.

Here we report a gene expression analysis of 186 human carcinomas from the lung, in which we provide evidence for biologically distinct subclasses of lung adenocarcinoma.

Materials and Methods

The procedures are described only briefly here. Please refer to supporting information, which is published on the PNAS web site (www.pnas.org) and at www.genome.wi.mit.edu/MPR/lung, for details.

Specimens and Datasets.

A total of 203 snap-frozen lung tumors (n = 186) and normal lung (n = 17) specimens were used to create two datasets. Of these, 125 adenocarcinoma samples were associated with clinical data and with histological slides from adjacent sections.

The 203 specimens (Dataset A) include histologically defined lung adenocarcinomas (n = 127), squamous cell lung carcinomas (n = 21), pulmonary carcinoids (n = 20), SCLC (n = 6) cases, and normal lung (n = 17) specimens. Other adenocarcinomas (n = 12) were suspected to be extrapulmonary metastases based on clinical history (see SampleData.xls, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org, and at www.genome.wi.mit.edu/MPR/lung). Dataset B, a subset of Dataset A, includes only adenocarcinomas and normal lung samples.

Microarray Experiments.

Total RNA extracted from samples was used to generate cRNA target, subsequently hybridized to human U95A oligonucleotide probe arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) according to standard protocols (13).

Feature Selection and Hierarchical Clustering.

For Dataset A, we used a standard deviation threshold of 50 expression units to select the 3,312 most variable transcript sequences (see Fig1Tree.cdt.tsv and Fig. 10, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). For Dataset B, 52 pairs of replicates (representing 36 duplicate adenocarcinomas) were used to determine the quality of the dataset, and 45 pairs having a R2 > 0.9 for expression measurements were used to select 675 transcript sequences (features) whose expression varied the most across all sample pairs (see Figs. 5–9, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

We used the CLUSTER and TREEVIEW programs (21) for hierarchical clustering and visualization of both Datasets A and B. Hierarchical clustering was performed following median centering and normalization.

Probabilistic Clustering and Class Definition.

To validate the classes discovered by hierarchical clustering, we used probabilistic model-based clustering as implemented in AUTOCLASS (22). We performed probabilistic clustering on 200 bootstrap datasets that were subjected to resampling with replacements from the original number of samples in Dataset B. A normalized score indicating frequency of membership to a subclass was plotted and indexed according to the hierarchical clustering order of Dataset B (see Figs. 11–15, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Analysis of Marker Genes.

We built a supervised classifier by first defining subclasses based on hierarchical and probabilistic clustering and chose marker genes by using “K-Nearest Neighbor” classifiers based on the signal-to-noise statistic (13). See Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, for details.

Kaplan–Meier Analysis.

We generated Kaplan–Meier (K-M) curves for each cluster and compared survival within the cluster to all other samples. A similar analysis was performed for stage I patient samples.

Results

Molecular Classification of Diverse Lung Tumors.

First, we applied hierarchical clustering (21) to classify all 203 samples, using the 3,312 most variably expressed transcripts (Dataset A; see Materials and Methods). The resulting clusters recapitulated the distinctions between established histologic classes of lung tumors—pulmonary carcinoid tumors, SCLC, squamous cell lung carcinomas, and adenocarcinomas—thus validating our experimental and analytic approach (Fig. 1; see Fig1Tree.cdt.tsv for a complete gene tree).

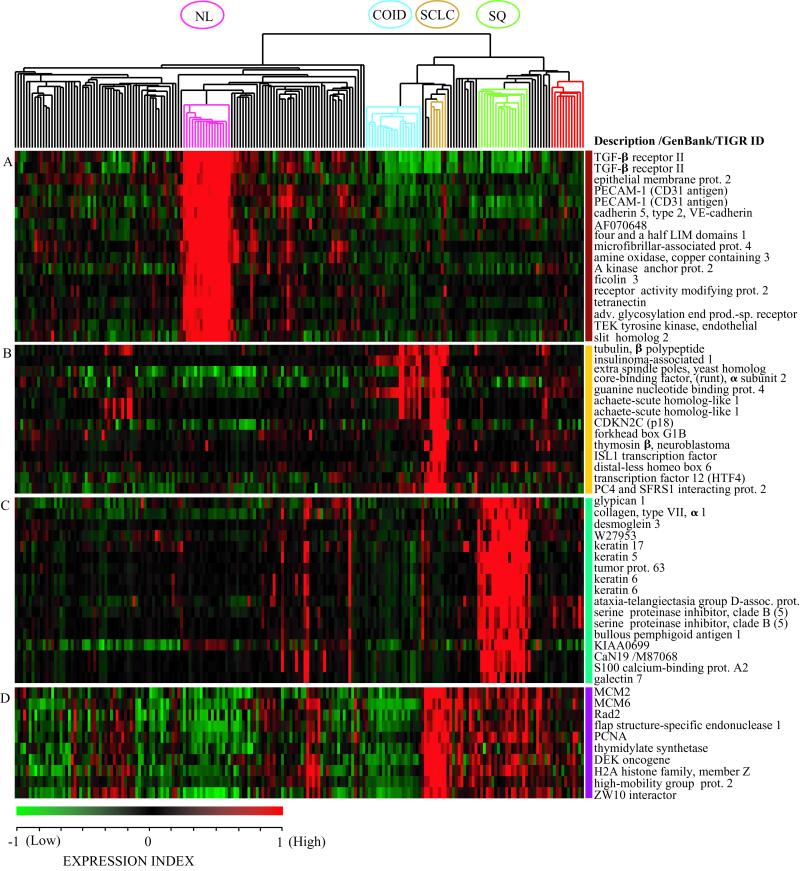

Figure 1.

Hierarchical clustering defines subclasses of lung tumors. Two-dimensional hierarchical clustering of 203 lung tumors and normal lung samples was performed with 3,312 transcript sequences. The normalized expression index for each transcript sequence (rows) in each sample (columns) is indicated by a color code (see EXPRESSION INDEX bar at lower left of figure). (A) Clusters of genes with high relative expression in normal lung (NL, pink branch). (B) Neuroendocrine tumors: small-cell lung cancer (SCLC, gold branch) and pulmonary carcinoids (COID, light blue branch). (C) squamous cell lung carcinomas with keratin markers (SQ, light green branch). (D) Proliferation-related markers. Adenocarcinomas resected from the lung (black branches) and a subset of adenocarcinomas suspected as colon metastases (red branch) are indicated. Color bars on the right correspond to regions displayed in Fig. 10.

The normal lung samples form a distinct group, but are most similar to the adenocarcinomas. Marker genes that characterize normal lung samples include TGF-β receptor type II, tetranectin, and ficolin 3 (Fig. 1A). This is not unexpected, because elevated TGF-β receptor type II levels have been previously reported for normal bronchial and alveolar epithelium compared with lung carcinomas (23).

SCLC and carcinoid tumors both show high-level expression of neuroendocrine genes (Fig. 1B), including insulinoma-associated gene 1 (24, 25), achaete scute homolog 1 (24, 25), gastrin-releasing peptide, and chromogranin A (see Fig1Tree.cdt.tsv). We also observed several previously uncharacterized markers for SCLC, such as thymosin-β and the cell cycle inhibitor p18INK4c (Fig. 1B). Only a few markers are shared between SCLC and carcinoids, whereas a distinct group of genes defines carcinoid tumors (see Fig1Tree.cdt.tsv and Fig. 10), suggesting that carcinoids are highly divergent from malignant lung tumors, as has been reported (26).

Squamous cell lung carcinomas, for which diagnostic criteria include evidence of squamous differentiation such as keratin formation (27), form a discrete cluster with high-level expression of transcripts for multiple keratin types and the keratinocyte-specific protein stratifin (Fig. 1C). The squamous tumors also show overexpression of p63, a p53-related gene essential for the formation of squamous epithelia (28), as has been observed (29). Several adenocarcinomas that express high levels of squamous-associated genes (Fig. 1C) also display histological evidence of squamous features (see SampleData.xls, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org).

Finally, expression of proliferative markers, such as PCNA, thymidylate synthase, MCM2, and MCM6, is highest in SCLC, which is known to be the most rapidly dividing lung tumor (Fig. 1D). However, unlike the other major lung tumor classes shown above, lung adenocarcinomas were not defined by a unique set of marker genes.

Class Discovery Among Lung Adenocarcinomas.

Strong signatures in other lung tumors may obscure the successful subclassification of lung adenocarcinoma in the above analysis. Therefore, we used hierarchical clustering to subclassify a dataset restricted to adenocarcinomas (Fig. 2, top dendrogram, and Fig. 3). To avoid spurious variations contributing to the clustering process, we selected 675 transcript sequences whose expression levels were most highly reproducible in duplicate adenocarcinoma samples, yet whose expression varied widely across the chosen sample set (Dataset B; see Materials and Methods). We included normal lung specimens in this dataset, because normal epithelium is a component of the grossly dissected adenocarcinoma samples.

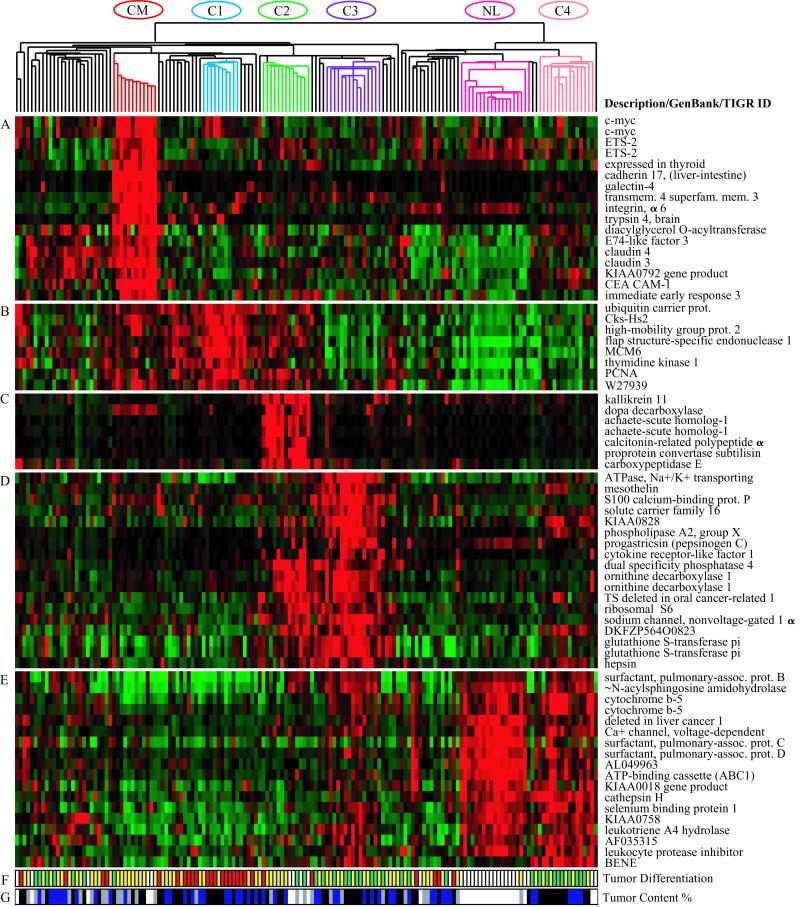

Figure 2.

Clustering defines adenocarcinoma subclasses. Comparison of classifications derived by hierarchical clustering (dendrogram) and probabilistic clustering (colored matrix) algorithms. The two-dimensional colored matrix is a visual representation of a corresponding numerical matrix whose entries record a normalized measure of association strength between samples. Strong association approaches a value of 1 (red) and poor association is close to 0 (blue). CM, colon metastasis; NL, normal lung; C1 through C4 are adenocarcinoma clusters; I (gold), II, and III are additional groups with weaker association. See Figs. 12–15 for details and sample names.

Figure 3.

Gene expression clusters and histologic differentiation within lung adenocarcinoma subclasses. Genes expressed at high levels in specific subsets of adenocarcinomas. The normalized expression index is shown as in Fig. 1. (A) Colon metastases. (B) Proliferation-related gene expression (C1). (C) Neuroendocrine gene expression (C2). (D) Ornithine decarboxylase 1 and surfactant gene expression (C3 and C2). (E) Type II pneumocyte gene expression (C4, C3, and normal lung). (F) Histopathological degree of differentiation (red, poor; yellow, moderate; green, well; white, not available or irrelevant). (G) Estimated nucleated tumor content: white, not determined or irrelevant; gray, 30–40%; blue, 40–70%; black, greater than 70%).

To reduce potential classification-bias due to choice of clustering method, and to clarify adenocarcinoma subclass boundaries, we also used a model-based probabilistic clustering method (22). To assess the overall strength of each pair-wise association, we measured the frequency with which two samples appeared together in a cluster in 200 clustering iterations over bootstrap datasets. We defined a stable cluster as a set of at least ten samples with a high degree of association (a threshold of 0.45 was used, corresponding to shared cluster membership in at least 45% of the bootstrap datasets in which both samples were included). According to this definition, several clusters suggested by the hierarchical tree are stable. Fig. 2 shows these associations as a color matrix (strongest associations shown in red) overlaid on the tree structure obtained from hierarchical clustering. The blocks of associated samples (red groups) show that both clustering methods recognized subclasses corresponding to normal lung and putative colon metastases (CM; see below). Four subclasses of primary lung adenocarcinoma (C1–C4) were also observed by both probabilistic and hierarchical clustering. Several smaller and/or less robust groups were also observed (Groups I, II, and III in Fig. 2).

Probabilistic clustering also revealed correlations between samples that do not directly cluster together. For example, although cluster C4 falls in the right branch of the hierarchical dendrogram with normal lung, it shows significant association with some subclasses in the left dendrogram (Groups I and III and cluster C3) but not with other subclasses (clusters CM, C1, and C2).

Clusters C2, C3, and C4 were also seen as coherent adenocarcinoma groups within the hierarchical clustering of the larger set of lung tumors when using the 3,312-transcript sequence set (Dataset A; see Fig. 10). The reproducible generation of these adenocarcinoma subclasses, across both clustering methods and both gene sets analyzed, supports the validity of the adenocarcinoma clusters and their boundaries.

To identify genes that best defined the proposed clusters, we used a supervised approach to extract marker genes from the entire set of 12,600 transcript sequences. For each cluster, we selected genes that were most preferentially expressed in the cluster relative to all other samples, using the signal-to-noise metric described (13). The genes whose expression correlated best with each class (see Table 1) may serve as markers for class prediction in future studies.

Identification of Adenocarcinomas Metastatic to the Lung.

A key issue in lung tumor diagnosis is the discrimination of a primary lung adenocarcinoma from a distant metastasis to the lung. We identified one distinct hierarchical cluster of 12 samples that most likely represent metastatic adenocarcinomas from the colon. These tumors express high levels of galectin-4, CEACAM1, and liver–intestinal cadherin 17, as well as c-myc, which is commonly overexpressed in colon carcinoma (see Fig. 1, CM, and Fig. 3A). Of the ten samples in this group for which clinical history and/or histopathologic information was available, only seven samples had been previously diagnosed as metastases of colonic origin (see SampleData.xls). Other adenocarcinomas that showed nonlung signatures included AD163, which expressed several breast-associated markers including estrogen receptor and mammaglobin, and was associated with a clinical history and histopathology consistent with breast metastasis (see Fig1Tree.cdt.tsv). Also, AD368, which was not identified as a metastasis, expressed high levels of albumin, transferrin, and other markers associated with the liver. Thus, clustering identified suspected metastases of extra-pulmonary origin, including some that were previously undetected, suggesting a pivotal role for gene expression analysis in lung tumor diagnosis.

Molecular Signature of Lung Adenocarcinoma Subclasses.

Hierarchical and probabilistic clustering defined four distinct subclasses of primary lung adenocarcinomas. Tumors in the C1 cluster express high levels of genes associated with cell division and proliferation (Fig. 3B), which are also expressed in the squamous cell lung carcinoma and SCLC samples in Dataset A (Fig. 1D). Relatively high-level expression of proliferation-associated genes was also seen in cluster C2.

Several neuroendocrine markers, such as dopa decarboxylase and achaete-scute homolog 1, define cluster C2 (Fig. 3C) and are also expressed in SCLC and pulmonary carcinoids. However, the serine protease, kallikrein 11, is uniquely expressed in the neuroendocrine C2 adenocarcinomas, and not in other neuroendocrine lung tumors (see Fig1Tree.cdt.tsv).

C3 tumors are defined by high-level expression of two sets of genes. Expression of one gene cluster, including ornithine decarboxylase 1 and glutathione S-transferase pi (Fig. 3D), is shared with the neuroendocrine C2 cluster. Expression of the second set of genes is shared with cluster C4 and with normal lung (Fig. 3E). Highest expression of type II alveolar pneumocyte markers, such as thyroid transcription factor 1, and surfactant protein B, C, and D genes, was seen in cluster C4, followed by normal lung and C3 cluster (Fig. 3E). Other markers that defined cluster C4 included cytochrome b5, cathepsin H, and epithelial mucin 1 (see Fig1Tree.cdt.tsv).

Relation Between Gene Expression Tumor Classes, Histological Analysis, and Smoking History.

Cluster C1 primarily contains poorly differentiated tumors, whereas C3 and C4 predominantly contain well differentiated tumors. Adenocarcinomas of cluster C2 fell in between (Fig. 3F). Ten of the fourteen C4 tumors had been identified as BACs by at least one of three pathologists who examined the tumors; in contrast, 15 of the remaining 113 adenocarcinomas were similarly described as BACs. The presence of type II pneumocyte markers and the high fraction of putative BACs suggest that cluster C4 is likely to be a gene expression counterpart to BAC. All of the C4 tumors in this study were surgical–pathological stage I tumors.

Although microscopic analysis indicated that our samples varied in homogeneity (Fig. 3G), contamination of normal lung cells does not seem to have overwhelmed the expression signatures. The degree to which tumors clustered with normal samples did not reflect the percentage of tumor cells in a sample in most cases. Class C4 is most similar to normal lung in both hierarchical and probabilistic clustering, yet these tumors all revealed at least an estimated 50% tumor nuclei and in most samples over 80%. In contrast, classes C2 and CM contain tumors with as few as 30% estimated tumor nuclei but are sharply distinguishable from the normal lung. Note that only adenocarcinoma specimen AD363, with an estimated 30% tumor content in the adjacent section, clustered with normal lung (see Fig. 10 and SampleData.xls).

Two adenocarcinoma subclasses were associated with lower tobacco smoking histories. The presumed metastases of colon origin (CM) and C4 adenocarcinomas with type II pneumocyte gene expression have median smoking histories of 2.5 and 23 pack-years, respectively. The entire dataset had a median smoking history of 40 pack-years.

Correlation of Patient Outcome with Putative Adenocarcinoma Classes.

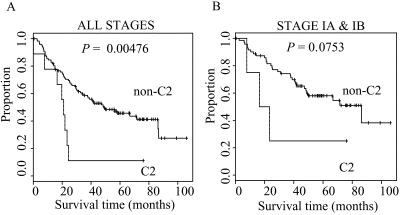

We asked whether lung cancer patient outcome correlated with the subclasses of lung adenocarcinomas defined herein. The neuroendocrine C2 adenocarcinomas were associated with a less favorable survival outcome than all other adenocarcinomas (Fig. 4 A and B). The median survival for C2 tumors was 21 months compared with 40.5 months for all non-C2 tumors (P = 0.00476). When only stage I tumors are considered, the median survival for patients with C2 tumors was 20 months compared with 47.8 months for patients with non-C2 tumors; as the numbers are smaller, the P value for this comparison is 0.0753. In contrast, C4 adenocarcinomas with type II pneumocyte gene expression (n = 14) were associated with a more favorable survival outcome than non-C4 tumors. The median survival for patients with C4 tumors was 49.7 months, whereas the median survival for patients with non-C4 tumors was 33.2 months (P = 0.049; note that the non-C2 and non-C4 groups are different because of the exclusion of each group separately in the comparison). For patients with stage I tumors, the median survival in the C4 group was 49.7 months and 43.5 months in the non-C4 group (P = 0.191). There was no detectable difference in prognosis between the primary lung adenocarcinomas and the metastases to the lung of colonic origin.

Figure 4.

Survival analysis of neuroendocrine C2 adenocarcinomas. Kaplan–Meier curves for C2 versus all other adenocarcinomas. (A) All patients: C2, n = 9; non-C2, n = 117. (B) Patients with stage I tumors only: C2, n = 4; non-C2, n = 72.

Discussion

In this study, we present a comprehensive gene expression analysis of human lung tumors, wherein we identified distinct lung adenocarcinoma subclasses that were reproducibly generated across different cluster methods. Notably, the C2 adenocarcinoma subclass, defined by neuroendocrine gene expression, is associated with a less favorable outcome, whereas the C4 group appears to be associated with a more favorable outcome.

Hierarchical clustering methods (21) offer a powerful approach to class discovery, but provide no means of determining confidence for the classes discovered. Combining bootstrap probabilistic clustering with the hierarchical method allowed us to measure the strength of sample–sample association, thereby defining cluster membership with greater confidence. Although the C1 and C3 subclasses do not correspond with prognostic distinctions in this dataset, the reproducible formation of these classes across distinct clustering methods supports their validity.

Although adenocarcinomas with neuroendocrine features have been reported (30, 31), unique markers that precisely define such tumors have not been described. Our current study uncovered putative neuroendocrine markers such as kallikrein 11 that discriminate the C2 tumors from all other lung tumors. This marker, which is related to the vasodepressor renal kallikrein (32), may be of clinical interest given the unexplained observation of orthostatic hypotension in some lung cancer patients (33).

Furthermore, we discovered putative metastases of extrapulmonary origin with non-lung expression signatures among presumed lung adenocarcinomas. This result suggests that gene expression analysis could serve as a diagnostic tool to confirm and identify metastases to the lung.

Comparison of our results to an independent study performed with a different set of tumors and expression-profiling platform (34) reveals a number of similarities. Expression signatures for previously defined tumor classes, such as SCLC and squamous cell lung carcinoma, overlap heavily between the two analyses. Furthermore, two of the adenocarcinoma classes we have identified, those with type II pneumocyte gene expression (C4) and those with surfactant/ornithine decarboxylase 1 gene expression (C3), have counterparts in the data of Garber et al. (34). However, other findings were unique to our dataset. Differences between the two studies indicate that the number of samples in either study alone is probably too small to allow for the generation of a classification scheme that fully represents the complexity of lung cancer.

In summary, we have generated a gene expression-based classification of lung cancer and a subclassification of lung adenocarcinoma. This study serves as a step toward defining a new molecular taxonomy of such tumors and demonstrates the potential power of gene expression profiling in lung cancer diagnosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We offer special thanks to David Livingston, who has stimulated and coordinated this project funded by U01 CA84995 from the National Cancer Institute. The work was also supported in part by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Affymetrix, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. M.M. is a Pew Scholar in the Biomedical Sciences.

Abbreviations

- SCLC

small-cell lung carcinomas

- NSCLC

non-small-cell lung carcinomas

- CM

colon metastases

- BAC

bronchioloalveolar carcinoma

References

- 1.Greenlee R T, Hill-Harmon M B, Murray T, Thun M. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:15–36. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Druker B J, Talpaz M, Resta D J, Peng B, Buchdunger E, Ford J M, Lydon N B, Kantarjian H, Capdeville R, Ohno-Jones S, et al. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1031–1037. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Travis W D, Travis L B, Devesa S S. Cancer. 1995;75:191–202. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950101)75:1+<191::aid-cncr2820751307>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorensen J B, Hirsch F R, Gazdar A, Olsen J E. Cancer. 1993;71:2971–2976. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930515)71:10<2971::aid-cncr2820711014>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breathnach O S, Kwiatkowski D J, Finkelstein D M, Godleski J, Sugarbaker D J, Johnson B E, Mentzer S. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;121:42–47. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.110190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breathnach O S, Ishibe N, Williams J, Linnoila R I, Caporaso N, Johnson B E. Cancer. 1999;86:1165–1173. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991001)86:7<1165::aid-cncr10>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shirakusa T, Tsutsui M, Motonaga R, Ando K, Kusano T. Am Surg. 1988;54:655–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flint A, Lloyd R V. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1992;116:39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chee M, Yang R, Hubbell E, Berno A, Huang X C, Stern D, Winkler J, Lockhart D J, Morris M S, Fodor S P. Science. 1996;274:610–614. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lockhart D J, Dong H, Byrne M C, Follettie M T, Gallo M V, Chee M S, Mittmann M, Wang C, Kobayashi M, Horton H, et al. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:1675–1680. doi: 10.1038/nbt1296-1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schena M, Shalon D, Davis R W, Brown P O. Science. 1995;270:467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schena M, Shalon D, Heller R, Chai A, Brown P O, Davis R W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10614–10619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golub T R, Slonim D K, Tamayo P, Huard C, Gaasenbeek M, Mesirov J P, Coller H, Loh M L, Downing J R, Caligiuri M A, et al. Science. 1999;286:531–537. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alizadeh A A, Eisen M B, Davis R E, Ma C, Lossos I S, Rosenwald A, Boldrick J C, Sabet H, Tran T, Yu X, et al. Nature (London) 2000;403:503–511. doi: 10.1038/35000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bittner M, Meltzer P, Chen Y, Jiang Y, Seftor E, Hendrix M, Radmacher M, Simon R, Yakhini Z, Ben-Dor A, et al. Nature (London) 2000;406:536–540. doi: 10.1038/35020115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perou C M, Sorlie T, Eisen M B, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey S S, Rees C A, Pollack J R, Ross D T, Johnsen H, Akslen L A, et al. Nature (London) 2000;406:747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welsh J B, Zarrinkar P P, Sapinoso L M, Kern S G, Behling C A, Monk B J, Lockhart D J, Burger R A, Hampton G M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1176–1181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alon U, Barkai N, Notterman D A, Gish K, Ybarra S, Mack D, Levine A J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6745–6750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan J, Wei J S, Ringner M, Saal L H, Ladanyi M, Westermann F, Berthold F, Schwab M, Antonescu C R, Peterson C, et al. Nat Med. 2001;7:673–679. doi: 10.1038/89044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mountain C F. Semin Surg Oncol. 2000;18:106–115. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2388(200003)18:2<106::aid-ssu4>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisen M B, Spellman P T, Brown P O, Botstein D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheeseman P, Stutz J. In: Advances in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. Fayyad U M, Piatetsky-Shapiro G, Smyth P, Uthurasamy R, editors. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1996. pp. 153–180. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang Y, Prentice M A, Mariano J M, Davarya S, Linnoila R I, Moody T W, Wakefield L M, Jakowlew S B. Exp Lung Res. 2000;26:685–707. doi: 10.1080/01902140150216765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ball D W, Azzoli C G, Baylin S B, Chi D, Dou S, Donis-Keller H, Cumaraswamy A, Borges M, Nelkin B D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5648–5652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lan M S, Russell E K, Lu J, Johnson B E, Notkins A L. Cancer Res. 1993;53:4169–4171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anbazhagan R, Tihan T, Bornman D M, Johnston J C, Saltz J H, Weigering A, Piantadosi S, Gabrielson E. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5119–5122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Travis W D, Colby T V, Corrin B, Shimosato Y, Brambilla E. Histological Typing of Lung and Pleural Tumors. Berlin: Springer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang A, Schweitzer R, Sun D, Kaghad M, Walker N, Bronson R T, Tabin C, Sharpe A, Caput D, Crum C, et al. Nature (London) 1999;398:714–718. doi: 10.1038/19539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hibi K, Trink B, Patturajan M, Westra W H, Caballero O L, Hill D E, Ratovitski E A, Jen J, Sidransky D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5462–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berendsen H H, de Leij L, Poppema S, Postmus P E, Boes A, Sluiter H J, The H. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:1614–1620. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.11.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skov B G, Sorensen J B, Hirsch F R, Larsson L I, Hansen H H. Ann Oncol. 1991;2:355–360. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a057955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vio C P, Olavarria V, Gonzalez C, Nazal L, Cordova M, Balestrini C. Biol Res. 1998;31:305–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gosney M A, Gosney J R, Lye M. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:1102–1105. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.12.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garber M E, Troyanskaya O G, Schluens K, Petersen S, Thaesler Z, Pacyna-Gengelbach M, van de Rijn M, Rosen G D, Perou C M, Whyte R I, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13784–13789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241500798. . (First Published November 13, 2001; 10.1073/pnas.241500798) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.