Abstract

The cellular origin of gastric cancer remains elusive. Leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor 5 (Lgr5) is the first identified marker of gastric stem cells. However, the role of Lgr5+ stem cells in driving malignant gastric cancer is not fully validated. Here, we deleted Smad4 and PTEN in murine gastric Lgr5+ stem cells by the inducible Cre-LoxP system and marked mutant Lgr5+ stem cells and their progeny with Cre-reporter Rosa26tdTomato. Rapid onset and progression from microadenoma and macroscopic adenoma to invasive intestinal-type gastric cancer (IGC) were found in the gastric antrum with the loss of Smad4 and PTEN. In addition, invasive IGC developed at the murine gastro-forestomach junction, where a few Lgr5+ stem cells reside. In contrast, Smad4 and PTEN deletions in differentiated cells, including antral parietal cells, pit cells and corpus Lgr5+ chief cells, failed to initiate tumor growth. Furthermore, mutant Lgr5+ cells were involved in IGC growth and progression. In the TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) database, an increase in LGR5 expression was manifested in the human IGC that occurred at the gastric antrum and gastro-esophageal junction. In addition, the concurrent deletion of SMAD4 and PTEN, as well as their reduced expression and deregulated downstream pathways, were associated with human IGC. Thus, we demonstrated that gastric Lgr5+ stem cells were cancer-initiating cells and might act as cancer-propagating cells to contribute to malignant progression.

Keywords: gastric tumorigenesis, gastric stem cell, Lgr5, lineage tracing

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common malignancy and the third leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide1. The vast majority of gastric cancer is adenocarcinoma, which consists of the intestinal-type and diffuse-type according to the Lauren classification, and it is thought to arise from the gastric epithelium via sequentially acquired mutations in specific genes. The gastric epithelium is organized into multiple gastric units that are fueled by a pool of stem cells capable of self-renewal and multilineage differentiation. In the adult gastric antrum, the Lgr5+ stem cells reside at the base of each gland and generate transit-amplifying cells, yielding differentiated cells that constitute the bulk of the glandular epithelium2. More recently, Troy+ chief cells and Mist1+ isthmus cells in the murine gastric corpus were identified as stem cells3,4, while Sox2-labeled gastric corpus isthmus and antral stem cells are distinct from Lgr5+ stem cells5.

Theoretically, gastric stem cells are the favored targets of transformation due to their inherent capacity for self-renewal and longevity, which permits the sequential acquisition of mutations and/or epigenetic changes required for tumorigenesis. A recent study showed that the murine corpus isthmus Mist1+ stem cells serve as a cellular origin of invasive diffuse-type gastric cancer (DGC)4. In Mist1+ stem cells, double deletions of E-cadherin gene (Cdh1), the most frequently mutated gene in human DGC, and p53 gene in the presence of chronic inflammation lead to invasive DGC4. As for intestinal-type gastric cancer (IGC), however, gastric stem cells with several pathways altered fail to give rise to malignant or invasive IGC4. Wnt signaling activation by Apc deletion or β-catenin stabilization in murine gastric antral Lgr5+ stem cells only leads to microadenoma even after a 100-day period2,6. Chronic Notch activation in murine antral Lgr5+ stem cells induces hyperplastic polyps within 1 year7. Similarly, in corpus Mist1+ stem cells, double mutations in Kras and Apc or Notch activation lead to intramucosal intestinal-type dysplasia4. To further complicate this, some clinical studies have revealed the increased LGR5-expressing cells or elevated LGR5 expression in IGC specimens, while some studies found that LGR5+ cells were absent in the premalignant IGC lesions8,9,10,11. Thus, whether gastric stem cells could act as cancer-initiating cells to drive malignant IGC formation lacks in vivo validation.

To elucidate the role of Lgr5+ stem cells in gastric carcinogenesis, we deleted Smad4 and PTEN in murine gastric Lgr5+ stem cells, and investigated the LGR5 expression as well as the alteration of SMAD4 and PTEN in human gastric cancers.

Results

Deletion of Smad4 and PTEN in murine Lgr5+ stem cells resulted in gastric tumor

Smad4, a central mediator of TGF-β signaling, is a well-known tumor suppressor, as evidenced by various murine models of different cancer types, including gastric cancer12. However, all of these murine models of gastric cancer arise from the germline heterozygous or T cell-specific deletion of Smad413,14,15,16. The epithelium-autonomous role of Smad4 in suppressing gastric cancer has not yet been clearly defined. Our previous study has demonstrated that PTEN deletion in the entire gastric epithelium leads to adenoma in the corpus and slight hyperplasia in the antrum17, implying that PTEN deletion alone is insufficient to initiate cancer in the gastric antrum, where Lgr5+ stem cells reside.

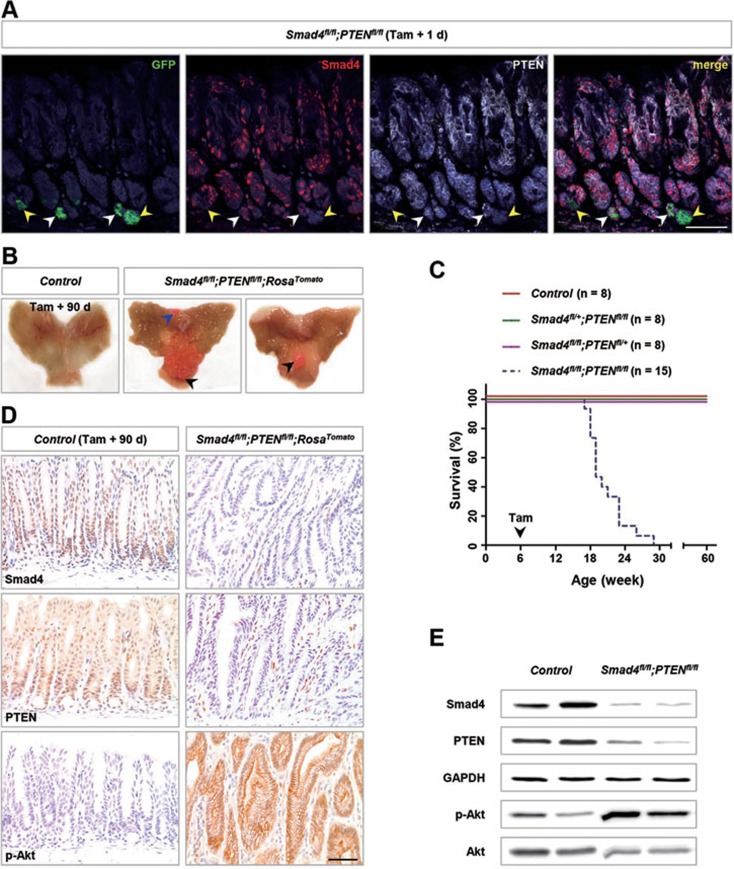

Thus, to fully clarify whether mutant Lgr5+ stem cells in the gastric antrum are involved in gastric tumorigenesis, mice carrying floxed Smad418 and PTEN19 alleles were bred with Lgr5-eGFP-IRES-CreERT2 knock-in mice20 to generate Lgr5-CreERT2;Smad4fl/+;PTENfl/+ (hereafter control), Lgr5-CreERT2;Smad4fl/fl;PTENfl/+ (Smad4fl/fl;PTENfl/+), Lgr5-CreERT2;Smad4fl/+;PTENfl/fl(Smad4fl/+;PTENfl/fl) and Lgr5-CreERT2;Smad4fl/fl;PTENfl/fl(Smad4fl/fl;PTENfl/fl) mice. We also used Rosa26-loxP-stop-loxP-tdTomato (RosaTomato) reporter mice21 to lineage trace the mutant Lgr5+ cells. Cre-mediated recombination within the reporter locus activates the expression of a red fluorescent protein variant, tdTomato, which indelibly marks the recombined cells and their progenies through their entire lifespan. Due to the previously reported low activity of Lgr5-CreERT2 transgenic mice, tamoxifen was administered for 6 consecutive days in 6-week-old mice, and no morphological abnormality associated with tamoxifen was observed in the gastric antral epithelium (Supplementary information, Figure S1A). Because the Lgr5-eGFP-IRES-CreERT2 knock-in mice carried an enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) cassette, Lgr5+ cells could be visualized by GFP expression. Immunofluorescence analysis of the Smad4fl/fl;PTENfl/fl antrum showed the concurrent loss of Smad4 and PTEN expression in Lgr5+ stem cells (Figure 1A, yellow arrowheads). On day 15 post induction, Smad4fl/fl;PTENfl/fl;RosaTomato antrum showed that clonal patches were negative for Smad4 and PTEN and positive for p-Akt and RFP (RFP antibody is also specific for Tomato), suggesting that Smad4 and PTEN were efficiently deleted in the progenies of Lgr5+ stem cells (Supplementary information, Figure S1B).

Figure 1.

Deletion of Smad4 and PTEN in murine gastric Lgr5+ stem cells resulted in tumorigenesis. (A) Immunofluorescence (IF) analysis using Smad4 (red), PTEN (white) and GFP (green; for Lgr5+ cells) antibodies in Lgr5+ stem cells from Lgr5-CreERT2;Smad4fl/fl;PTENfl/fl (hereafter Smad4fl/fl;PTENfl/fl) antrum 1 day after tamoxifen (Tam) administration. White arrowheads indicated the wild-type Lgr5+ stem cells, and yellow arrowheads indicated the deficient Lgr5+ stem cells. (B) Gross anatomy of the representative stomach of control and Smad4fl/fl;PTENfl/fl;RosaTomato double-mutant mice 90 days after tamoxifen treatment; the latter shows macroscopic polyps (arrowheads). Of note, red polyps could be clearly seen without a microscope. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of Smad4fl/fl;PTENfl/fl compound mutant mice (blue dotted line; n = 15) compared with control mice (red solid line; n = 8; P < 0.0001 by log-rank test), Smad4fl/+;PTENfl/fl mice (green solid line; n = 8; P < 0.0001) or Smad4fl/fl;PTENfl/+ mice (purple solid line; n = 8; P < 0.0001). (D) IHC analysis of Smad4, PTEN and p-Akt confirmed complete loss of Smad4 and PTEN and activation of Akt. (E) Western blot analysis of Smad4, PTEN and p-Akt in the control antral epithelium and Smad4fl/fl;PTENfl/fl polyps 90 days post induction. Scale bar, 50 μm.

As early as 3 months post induction, 65% (13/20) of Smad4 and PTEN double-mutant mice in the RosaTomato background developed red polyps in the gastric antrum (Figure 1B, black arrowheads, Table 1). In addition, red polyps adjacent to forestomach, where a few Lgr5+ cells at the base of corpus glands near forestomach/esophageal border act as stem cells2, were found in 25% (5/20) of mice lacking Smad4 and PTEN (Figure 1B, blue arrowhead). Afterwards, double-mutant mice exhibited progressive weakness and died within 5 months (Figure 1C).

Table 1. Cancer incidence in double-mutant and control mice.

| Months | Control | Smad4fl/+;PTENfl/fl | Smad4fl/fl;PTENfl/+ | Smad4fl/fl;PTENfl/fl | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 m | MA | 0/9 | 0/8 | 0/8 | 6/10* |

| A | 0/9 | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0/10 | |

| IA | 0/9 | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0/10 | |

| 3 m | MA | 0/12 | 0/11 | 0/8 | 20/20* |

| A | 0/12 | 0/11 | 0/8 | 13/20* | |

| IA | 0/12 | 0/11 | 0/8 | 8/20* | |

| 12 m | MA | 0/10 | 5/8* | 8/8* | NA |

| A | 0/10 | 0/8 | 4/8* | NA | |

| IA | 0/10 | 0/8 | 0/8 | NA |

MA, microadenoma; A, adenoma; IA, invasive adenocarcinoma; NA, not applicable.

*P < 0.05. The Fisher's exact test was used for comparison with control.

Red polyps indicated that the lesions might arise as a result of Cre activity in mutant Lgr5+ cells (Figure 1B, arrowheads). Consistent with this, immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis displayed clear loss of Smad4 and PTEN as well as consequent p-Akt activation, which were further supported by the western blot results (Figure 1D and 1E). Taken together, the above data demonstrate that mutant gastric Lgr5+ cells produced gastric tumors.

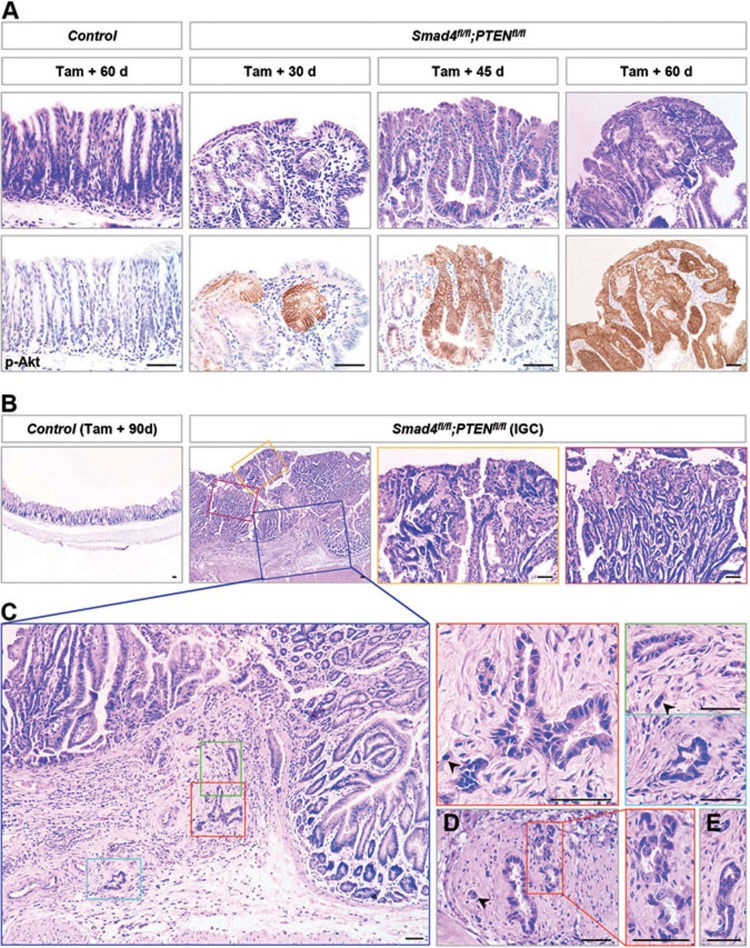

Mutant gastric Lgr5+ stem cells gave rise to invasive IGC

Histological examination showed a normally defined glandular structure in the control antrum on day 60 post induction (Figure 2A). In sharp contrast, as early as 30 days post induction, a single adenomatous gland visualized by p-Akt expression appeared in the Smad4 and PTEN double-mutant antrum (Figure 2A). On day 45, 60% (6/10) of mutant mice developed microadenomas that consisted of more than one adenomatous gland (Figure 2A and Table 1). By 60 days, double-mutant mice displayed robust and widespread microadenomas (Figure 2A). On day 90 post induction, 65% (13/20) of mutants presented with macroscopic adenomas that were greater than 2 mm × 2 mm in size and could be viewed by the naked eye (Figure 1B and Table 1). Adenoma exhibited a marked increase in proliferative cells and loss of differentiated cells, such as chief cells, pit cells, parietal cells and hormone-secreting G cells (Supplementary information, Figure S2). In addition, ectopic expression of intestinal epithelial markers, such as Villin, Cdx1 and Cdx2, was observed in adenoma (Supplementary information, Figure S3). Notably, 40% (8/20) of Smad4 and PTEN compound deficient mice developed IGC that invaded into the submucosa (Figure 2B, Table 1 and Supplementary information, Figure S4). Invasive lesions displayed irregularly shaped and multi-layered glands that varied in size, shape and contour, as well as a string of cells and single cancer cells, which were accompanied by cytological atypia (Figure 2C-2E and Supplementary information, Figure S4). In addition, some cancer cells disruptively infiltrated into the muscularis propria (Figure 2D). Accordingly, a 2.5- and 2-fold increase in Ki67-positive cells was observed in intramucosal and invasive lesions, respectively (Supplementary information, Figure S5). In contrast, until 12 months after tamoxifen treatment, 50% (4/8) of Smad4 single-mutant mice presented with polypoid adenoma (Supplementary information, Figure S6A, Table 1), while 63% (5/8) of PTEN single-mutant mice only developed microadenoma (Supplementary information, Figure S6B, Table 1). At the gastro-forestomach/esophageal junction, Lgr5+ stem cells with Smad4 and PTEN mutations produced identical phenotypes, while the penetrance was 25% (5/20) and lower than that in the antrum (Supplementary information, Figure S7). Collectively, we revealed that gastric Lgr5+ stem cells served as the cellular origin of invasive IGC.

Figure 2.

Gastric adenocarcinoma was driven by antral Lgr5+ stem cells with the loss of Smad4 and PTEN. (A) H&E staining and p-Akt IHC were performed on the serial sections from control and Smad4 and PTEN double-mutant antrum. Control mice exhibited a normal structure of antral glands 60 days post induction. However, as early as 30 days post induction, a single adenomatous gland visualized by p-Akt staining appeared in the double-mutant antrum. 45 days post induction, double-mutant mice presented with microadenomas that were smaller than 2 mm × 2 mm in size and only detected on microscopic examination. On day 60 after tamoxifen treatment, microadenomas became robust and widespread throughout the gastric antrum. (B) H&E staining of control and double-mutant antrum 90 days post induction. On day 90, 40% (8/20) of Smad4 and PTEN compound deficient mice exhibited the invasive adenocarcinoma. The yellow and purple solid-line boxes in B were magnified on the right. (C-E) The submucosal lesions of gastric antral invasive adenocarcinoma. The invasive glands exhibited irregular outpouchings and sharp edges, and consisted of only a few epithelial cells (arrowheads). (C) The lesion is magnified from the blue solid-line box in B. The green, red and light blue solid-line boxes in C were magnified on the right. (D) Some invasive lesions displayed destructive infiltration into the muscularis propria. Scale bar, 50 μm.

As expected, invasive adenocarcinomas were also found in Smad4 and PTEN double-mutant small intestine and colon where Lgr5 also marks stem cells (Supplementary information, Figure S8). Of note, the invasive adenocarcinoma in the colon with complete penetrance was histologically more extensive and destructive (Supplementary information, Figure S8C and S8D).

In addition, we examined whether Smad4 loss combined with alterations of other genes in gastric Lgr5+ stem cells could lead to invasive IGC. Either simultaneous deletion of Smad4 and p53 genes22 (Lgr5-Cre;Smad4fl/fl;p53fl/fl) or Smad4 deletion with KrasG12D23 expression (Lgr5-Cre;Smad4fl/fl;KrasG12D/+) was insufficient to initiate adenoma (Supplementary information, Figure S9A and S9B). When KrasG12D was expressed in the background of Smad4 and p53 double deletion (Lgr5-Cre;Smad4fl/fl;p53fl/fl;KrasG12D/+), these triple mutantmice showed hyperplasia polyps in gastric antrum (Supplementary information, Figure S9C).

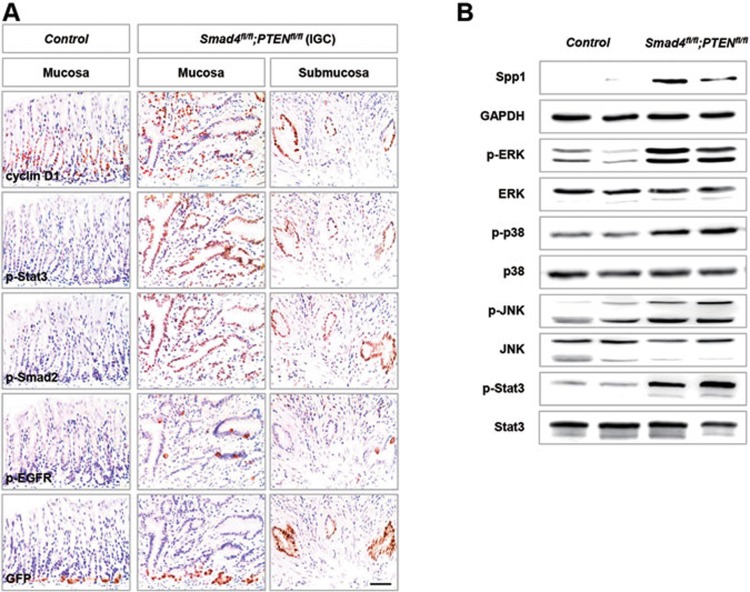

Molecular alterations in gastric cancer caused by Smad4 and PTEN deletion

Next, we investigated the downstream effectors of Smad4 and PTEN pathways responsible for tumor formation and progression. IHC and western blot results showed that Smad4 deletion resulted in a dramatic increase in the expression of Smad4 targets, cyclin D1 and Spp1, two key effectors in cancer growth and metastasis24 (Figure 3A and 3B). In addition, the level of phosphorylated Smad2 (p-Smad2), a progression-associated factor in human advanced gastric cancer25, was strikingly increased in Smad4 and PTEN deficient tumors (Figure 3A). We also found that the Stat3, EGFR and MAPK pathways were activated in adenoma and invasive adenocarcinoma, as supported by phosphorylation of Stat3, EGFR, ERK, p38 and JNK (Figure 3A and 3B). All of them are involved in gastric cancer progression and correlate with a poor prognosis in human gastric cancer26,27,28. Taken together, Smad4 and PTEN deletion in gastric Lgr5+ stem cells led to invasive IGC phenocopying the molecular alterations of human gastric cancer.

Figure 3.

Molecular alterations in Smad4 and PTEN double-mutant gastric cancer. (A) IHC analysis of control antral epithelium (column 1), mucosa (column 2) and submucosa (column 3) from Smad4 and PTEN compound mutant adenocarcinoma 3 months post induction. Antibodies against cyclin D1, p-Stat3, p-Smad2, p-EGFR and GFP (for Lgr5+ cells) were used. (B) Western blot analysis of the control antral epithelium and adenoma from a Smad4 and PTEN compound mutant. Antibodies against Spp1, GAPDH, p-ERK, ERK, p-p38, p38, p-JNK, JNK, p-Stat3 and Stat3 were used. Scale bar, 50 μm.

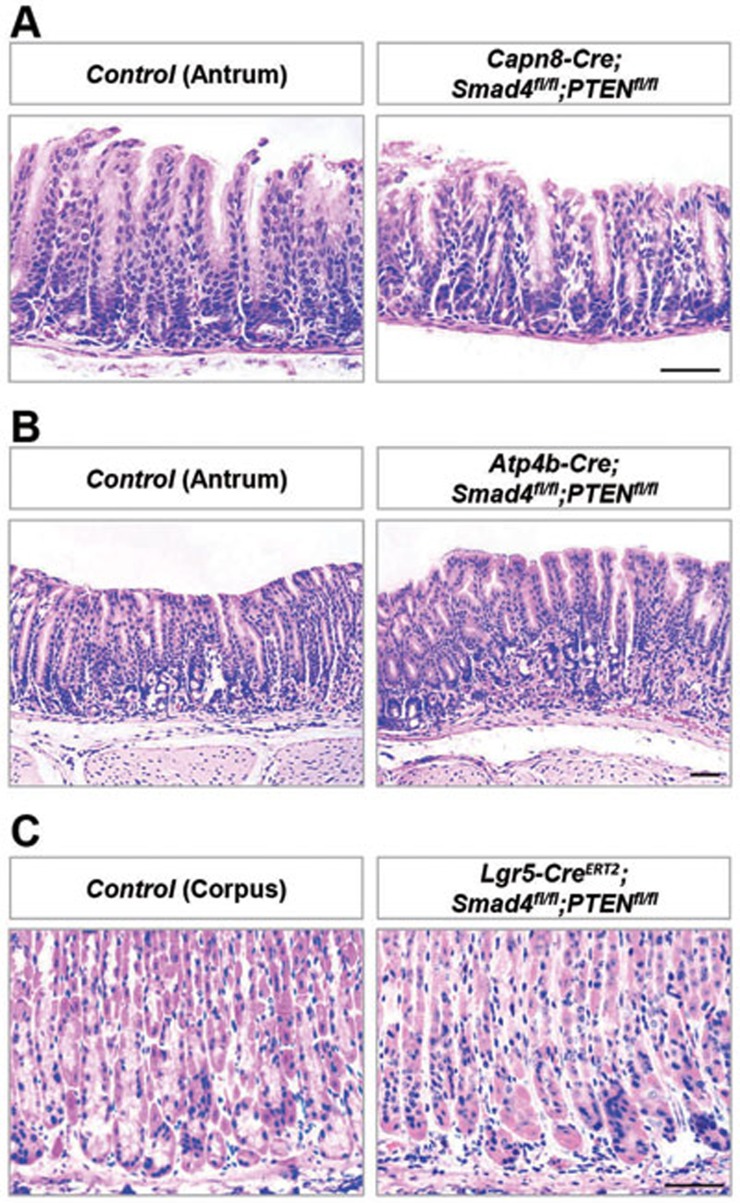

Gastric differentiated cells with loss of Smad4 and PTEN failed to initiate tumor formation

We further examined whether Lgr5+ stem cells were more prone to driving malignant transformation than their differentiated progeny. A previous study has shown that Lgr5+ stem cells give rise to pit cells in the antrum and parietal cells located at the transition zone between the antrum and corpus on the lesser curvature2. We utilized two Cre transgenic mouse lines, Capn8-Cre29 and Atp4b-Cre30, in which Cre-mediated recombination occurred in pit and parietal cells. In the same Smad4 and PTEN mutant background, no morphological aberration was found in the gastric antrum or transition zone of these two murine lines (Figure 4A and 4B; Supplementary information, Figure S10A and S10B).

Figure 4.

No tumor formation in mice with gastric differentiated cell-specific deletion of Smad4 and PTEN. (A) H&E staining of gastric antrum from 3-month-old control and pit cell-specific Smad4 and PTEN double-mutant mice driven by Capn8-Cre. (B) H&E staining of the transition zone between the gastric antrum and corpus on the lesser curvature from 3-month-old control and parietal cell-specific Smad4 and PTEN double-mutant mice driven by Atp4b-Cre. (C) H&E staining of the gastric corpus on the lesser curvature from 3-month-old control and Lgr5+ chief cell-specific Smad4 and PTEN double-mutant mice driven by Lgr5-CreERT2. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Lgr5 also marks some chief cells at the gastric lesser curvature31 (Supplementary information, Figure S10C). In the same double-mutant mouse, Lgr5+ chief cells with Smad4 and PTEN deletion did not lead to morphological alteration at the gastric lesser curvature even 90 days post induction (Figure 4C and Supplementary information, Figure S10C), which coincided with a previous study performed in the setting of acute oxyntic atrophy revealing that Lgr5+ chief cells do not contribute to the induction of metaplasia31. Collectively, these results suggested that, at least in the context of Smad4 and PTEN loss, the gastric Lgr5+ stem cells are favored targets for gastric tumorigenesis.

Mutant Lgr5+ cells were involved in IGC growth and progression

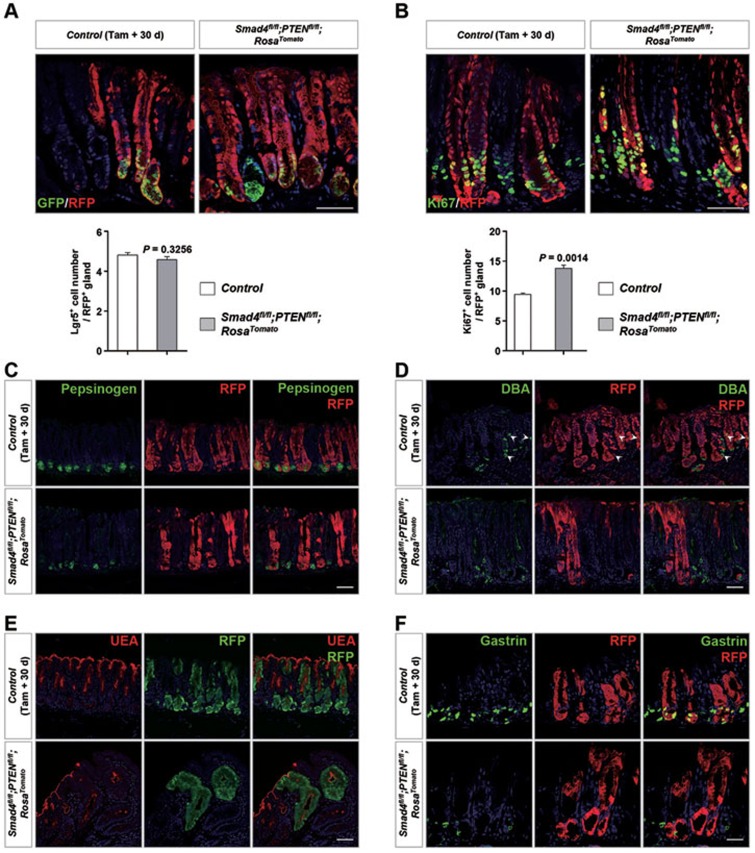

Next, we assessed how Lgr5+ stem cells initiated malignant gastric cancer. First, we examined Lgr5+ stem cells at the early stage of tumor formation. On day 30 post induction, the majority of antral glands deficient in Smad4 and PTEN, as monitored by RFP, were morphologically well-defined and indistinguishable from the nearby neutral glands (Figure 5). The Lgr5+ cell number in RFP+ glands was similar between wild-type and mutant mice (Figure 5A), and mutant Lgr5+ cells still resided in the normal position at the gland base. However, right above the Lgr5+ stem cell domain, a marked increase of Ki67+ cells and expansion of the Ki67+ proliferative zone were found in double-mutant mice (Figure 5B). Meanwhile, mutant Lgr5+ cells failed to differentiate into chief, parietal, pit and hormone-secreting G cells, as confirmed by loss of the corresponding markers (Figure 5C-5F). Thus, in the early stage of tumorigenesis, although the Lgr5+ stem cell, as the cancer-initiating cell, acquired the Smad4 and PTEN mutations, Lgr5+ stem cell-derived progenies mainly contributed to hyperplasia by promoting proliferation and blocking differentiation.

Figure 5.

Mutant Lgr5+ progenies rapidly expanded and failed to differentiate. (A) Double IF analysis using RFP (for recombined cells) and GFP (for Lgr5+ cells) antibodies in control as well as Smad4 and PTEN double-mutant glands 30 days after induction. Quantification of the Lgr5+ cell number per RFP+ gland is shown below. (B) Double IF analysis using RFP and Ki67 antibodies in control and double-mutant glands 30 days after induction. Quantification of the Ki67+ cell number per RFP+ gland is shown below. (C-E) Double IF analysis of RFP and differentiated cell markers, such as Pepsinogen (C, for chief cell), DBA (D, for parietal cell) and UEA (E, for pit cell) in control and double-mutant glands. (F) Double staining of RFP by IF and Gastrin (for hormone-secreting G cell) mRNA by in situ hybridization in control and double-mutant glands. Significance was calculated using Student's t-test (n = 4). Scale bar, 50 μm.

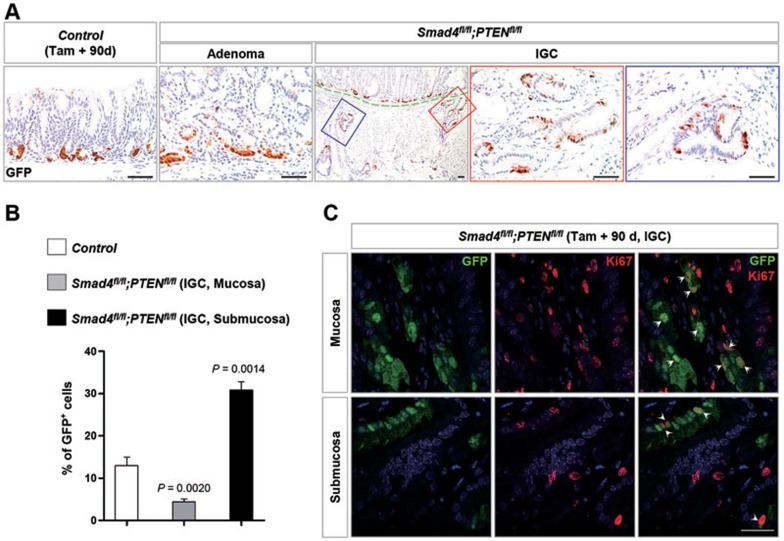

Mutant Lgr5+ cells still resided at the very base when hyperplasia progressed into benign adenoma in Smad4 and PTEN double or Smad4 single mutant antrum (Figure 6A and Supplementary information, Figure S6A). Even in the intramucosal lesion of antral IGC, Lgr5+ cells were not increased in number and were still restricted toward the base (Figure 6A). Unexpectedly, in the invasive lesion of the antral IGC, the Lgr5+ cells accounted for 31% of tumor cells, which is strikingly higher than 4.4% in the intramucosal lesion, and showed an extensive distribution throughout the invasive lesion (Figure 6B). More importantly, mutant Lgr5+ cells, regardless of their position, displayed proliferative capability (Figure 6C). In addition, a similar expression pattern of Lgr5+ cells was found in the invasive adenocarcinoma of the intestine and colon (Supplementary information, Figure S8B and S8E). Notably, a prior in vivo lineage tracing study identified intestinal Lgr5+ adenoma cells as so-called cancer stem cells that promote mouse intestinal adenoma growth32. Taken together, the above results suggested that mutant Lgr5+ cells contribute to gastric tumor growth and progression.

Figure 6.

Lgr5+ cells in antral IGC. (A) Lgr5+ cells, indicated by GFP staining, were restricted to the base in control, adenoma, and mucosal IGC lesions, but they expanded throughout the invasive IGC lesion. The green dotted line divided the mucous layer and submucosa. Red frame (submucosa) and blue frame (muscularis propria) were magnified to clearly show Lgr5 expression. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) Quantification of the percentage of Lgr5+ cells in control gastric antral epithelium and IGC. Significance was calculated using the Student's t-test. (C) Double IF analysis using GFP (green) and Ki67 (red) antibodies revealed that mutant Lgr5+ cells were actively proliferating. Scale bar, 25 μm.

Aberrations in the SMAD4 and PTEN pathways and increased LGR5 expression in human IGC

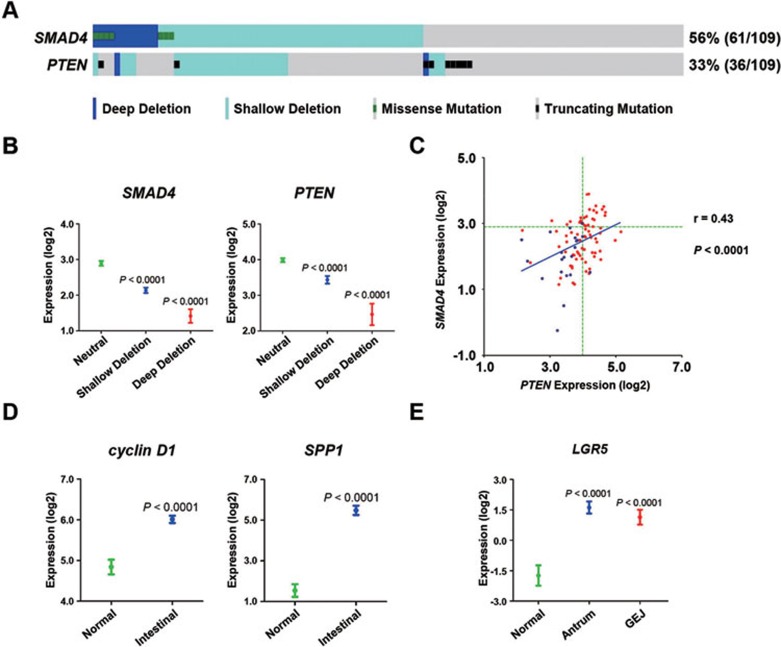

To confirm whether the murine model generated here would recapitulate human IGC, we analyzed 152 human gastric cancer samples from the TCGA database that occurred at the gastric antrum and gastro-esophageal junction (GEJ)33. We found that gene deletion in the SMAD4 or PTEN locus was more frequent in the intestinal subtype than in the diffuse subtype (Supplementary information, Tables S1 and S2). As shown in Figure 7A, in the intestinal subtype, 56% (61/109) of gastric samples had SMAD4 deletion and/or mutation, and 33% (36/109) had PTEN deletion and/or mutation. As expected, SMAD4 or PTEN deletion was tightly associated with low mRNA and protein expression in human intestinal subtype gastric cancer (Figure 7B and Supplementary information, Tables S3 and S4).

Figure 7.

Aberrations in the SMAD4 and PTEN pathways and the increased LGR5 expression in human IGC. The DNA copy number, mutations and RNA data of human gastric cancer were downloaded or derived from the TCGA database (Supplementary information, Table S8). (A) Deletion and mutations of SMAD4 and PTEN were found in 109 human gastric cancer samples that were classified as the intestinal subtype and occurred at gastric antrum and GEJ. The classes of deletion and mutations were distinguished by color. (B) Deletion of SMAD4 or PTEN in human gastric cancer was associated with their low mRNA expression. The y-axis indicated log2-transformaed reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RPKM). If no reads were mapped on the corresponding gene, the y-axis is set to −10. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Significance was calculated by Student's t-test or Wilcoxon two-sample test. SMAD4: Neutral (diploid), n = 34; shallow deletion, n = 41; deep deletion, n = 12. PTEN: Neutral, n = 57; shallow deletion, n = 22; and deep deletion, n = 2. (C) Scatterplots of SMAD4 versus PTEN mRNA expression in 94 human IGC samples. The green dotted lines indicate the average expression level of the diploid genes. The blue dots (n = 21) indicate the samples carrying the concurrent deletion of SMAD4 and PTEN. Spearman's correlation coefficients (r) and P-values are shown. (D) High mRNA expression of cyclin D1 and SPP1 were found in the IGC samples. Significance was calculated using the Student's t-test or Wilcoxon's two-sample test. Normal: n = 29; intestinal: n = 94. (E) High mRNA expression of LGR5 was found in the IGC samples and in the intestinal subtype subpopulation that occurred at the gastric antrum and GEJ. Significance was calculated using the Student's t-test or Wilcoxon's two-sample test. Normal: n = 29; antrum: n = 62; GEJ: n = 32.

Notably, concurrent deletions in the SMAD4 and PTEN loci were found in 24% (26/109) of the intestinal type samples from the gastric antrum and GEJ (Figure 7A and Supplementary information, Table S5), and there was a statistically significant difference between double and single deletion of SMAD4 and PTEN (Supplementary information, Table S5). Consistent with this, the mRNA levels of SMAD4 versus PTEN were positively correlated in the intestinal type samples (Figure 7C), indicating the contribution of SMAD4 and PTEN downregulation in human gastric cancer growth. Then, we assessed the downstream effectors of SMAD4 and PTEN pathways in human IGC. An increase in the cyclin D1 and SPP1 expression was identified in the intestinal subtype (Figure 7D). In addition, an inverse correlation between SMAD4 and cyclin D1, as well as PTEN and p-AktT308, was confirmed in human IGC (Supplementary information, Tables S6 and S7).

Analysis of the same data revealed elevated LGR5 expression in the intestinal subtype of gastric adenocarcinoma at the gastric antrum and GEJ (Figure 7E), supporting that LGR5+ stem cells might be involved in human gastric tumor growth and progression.

Discussion

We provide the first critical in vivo evidence that gastric stem cells are the cellular origin of aggressively muscle-invasive gastric adenocarcinoma. Lgr5 is a well-established tissue stem cell marker for various epithelial types, such as gastric antrum, intestine, colon and skin2,20,34. The tumor-initiating role of the Lgr5+ stem cell was first identified in the murine intestine where the rapid onset of and progression to adenoma resulted from Lgr5+ stem cell-specific Apc loss32,35. However, in the gastric antral epithelium, these same mice only display microadenoma and invariably fail to develop into adenomas during a 100-day period2,6, challenging the role of Lgr5+ stem cells in driving gastric tumorigenesis. Here, in our model, microadenomas were readily visible throughout the antrum as early as 60 days post induction and they developed into macroscopic adenoma by 90 days, demonstrating the stem cell origin of gastric tumor. More strikingly, following malignant transformation, adenoma developed into aggressively invasive adenocarcinoma. Finally, the notion that mutant Lgr5+ stem cells give rise to invasive IGC was formally validated by Cre-reporter RosaTomato that permanently marked the mutant Lgr5+ stem cells and their progenies.

Our group and other research groups have demonstrated cooperative functionality between Smad4 and PTEN signaling in suppressing tumorigenesis in various tumor mouse models of different tissues, such as squamous cell carcinoma in the skin and esophagus and adenocarcinoma in the prostate and pancreas24,36,37,38. Here, we demonstrated the synergetic effect between Smad4 and PTEN deletion in driving gastric tumor initiation in the context of tissue stem cells. Most importantly, the contribution of SMAD4 and PTEN loss to human gastric cancer was verified in human gastric cancer samples. A high rate of deletion and mutation at SMAD4 and PTEN loci was revealed in human gastric cancer, especially in the intestinal subtype. Furthermore, co-occurrence of SMAD4 and PTEN deletion and mRNA downregulation was observed in the intestinal subtype. Finally, the deregulated SMAD4 and PTEN pathways in human gastric cancer resembled the alterations that we observed in mice.

Another meaningful finding emerged from the Lgr5 expression pattern in gastric adenoma and invasive adenocarcinoma. In the murine intestine, evidence from in vitro proliferative activity and in vivo lineage tracing analysis demonstrated that intestinal Lgr5+ stem cells act as cancer stem cells to fuel the growth of the established intestinal adenomas32. Here, we observed that the mutant Lgr5+ cells were exclusively located at the base of benign adenoma, which is similar to the previously reported pattern in the mutant Lgr5+ cell-driven intestinal adenoma32. Unexpectedly and not previously reported in murine intestine models, a markedly elevated proportion of Lgr5+ cells were present throughout the invasive region of gastric adenocarcinoma, implying that the mutant Lgr5+ cells may be involved in the malignant transition and progression. Of note, the mutant Lgr5+ cells, regardless of their location, exhibited proliferative ability that could be measured by Ki67 staining. Together, these data demonstrated the potential of Lgr5+ cells to promote gastric cancer growth and propagation. Notably, two studies from human gastric cancer samples have shown that Lgr5+ cells exclusively reside at the base of adenoma, but they have a widespread distribution in invasive adenocarcinoma, especially at the invasive front8,9. Moreover, our analysis in human advanced gastric cancer samples confirmed the markedly elevated LGR5 expression. Thus, the particular pattern and proliferative capability of Lgr5+ cells indicate the therapeutic potential of targeting LGR5+ cells in human gastric cancer.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Smad4fl/fl, PTENfl/fl, p53fl/fl and KrasG12D/+ mice were described earlier18,19,22,23. The Lgr5-eGFP-IRES-CreERT2 and Rosa26-loxP-stop-loxP-tdTomato mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory20,21. Cre-recombinase was induced by six daily intraperitoneal injections of 2 mg of tamoxifen (Sigma Aldrich, T5648) in an ethanol/corn oil mixture. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with BrdU (Sigma Aldrich, 35002-5G, 100 mg/kg body weight) in PBS at 10 mg/ml 2 h before sacrifice. Animal experiments were approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of the Institute of Biotechnology.

Data analysis

The data of human gastric cancer analyzed here were downloaded or derived from a previous TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) study33. Supplementary information, Table S8 lists the detailed human gastric cancer information, including the clinicopathological characteristics, DNA, mRNA and/or protein data for SMAD4, PTEN, cyclin D1, SPP1, p-AktT308 and LGR5. The mRNA and protein expression data (level 4 data) were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/docs/publications/stad_2014/). Protein measurements were corrected for loading using median centering across antibodies. A value > 0 was defined as high expression, and a value < 0 was defined as low expression in Supplementary information, Tables S3, S4, S6 and S7. The DNA copy number and mutation data were downloaded from cBioPortal (http://www.cbioportal.org) in which the corresponding TCGA data were analyzed. “–2” in copy number indicates “deep deletion”, “–1” indicates “shallow deletion”, and “0” indicates “diploid”. All quantitative values are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.2 and GraphPad Prism software v5. We also analyzed the data using OncoPrinter, which is from the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics39,40. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Other Materials and Methods in detail are provided in Supplementary information, Data S1.

Author Contributions

YT and XY developed the concept of this study and wrote the manuscript. X-BL and GY conducted most of the experiments. LZ, Y-LT and CZ contributed to histological analyses. ZJ contributed to the data analysis. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Competing Financial Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (2011CB504202 to XY, 2012CB945103 to XY and YT, and 2012CB966904 to GY), the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (2012AA022402) to YT, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81572717 and 81272702 to YT and X-BL, 31030040 to XY, 31171249 to YT, 81172220 to X-BL, and 31571512 to GY and LZ).

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Information

Smad4 and PTEN were efficiently deleted in the progenies of Lgr5+ stem cells at gastric antrum.

Gastric antral adenoma in Smad4 and PTEN mutant mice exhibited a marked increase in proliferative cells and a complete loss of differentiated cells.

Gastric antral adenoma in Smad4 and PTEN mutant mice ectopically expressed intestinal epithelial markers.

Invasive IGC in Smad4 and PTEN compound mutant mice.

Active proliferation in IGC of Smad4 and PTEN compound mutant mice.

Gastric tumor formation in Smad4 or PTEN single mutant mice.

Invasive IGC at the gastro-forestomach/esophageal junction of Smad4 and PTEN double mutant stomach.

Invasive adenocarcinoma in the intestine and colon of Smad4 and PTEN compound mutant mice.

Smad4 deletion with combination of p53 deletion and/or KrasG12D expression in gastric Lgr5+ stem cells led to tumor formation.

Concurrent loss of Smad4 and PTEN expression in pit and parietal cells at antral region and chief cells at corpus region.

A correlation between SMAD4 gene deletion and human gastric cancer subtypes occurring at the antrum and gastro-esophageal junction (GEJ)

A correlation between PTEN gene deletion and human gastric cancer subtypes occurring at the antrum and GEJ

SMAD4 gene deletion relative to protein expression in human intestinal-type gastric cancers occurring at the antrum and GEJ

PTEN gene deletion relative to protein expression in human intestinal-type gastric cancers occurring at the antrum and GEJ

A correlation in the gene deletion between SMAD4 and PTEN in human intestinal-type gastric cancers occurring at the antrum and gastro-esophageal junction (GEJ)

SMAD4 protein expression relative to cyclin D1 in human intestinal-type gastric cancers occurring at the antrum and GEJ

PTEN protein expression relative to p-AktT308 in human intestinal-type gastric cancers occurring at the antrum and GEJ

152 human gastric cancer data from TCGA

Materials and Methods

References

- Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015; 65:87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, Huch M, Kujala P, et al. Lgr5+ve stem cells drive self-renewal in the stomach and build long-lived gastric units in vitro. Cell Stem Cell 2010; 6:25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stange DE, Koo BK, Huch M, et al. Differentiated Troy+ chief cells act as reserve stem cells to generate all lineages of the stomach epithelium. Cell 2013; 155:357–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa Y, Ariyama H, Stancikova J, et al. Mist1 expressing gastric stem cells maintain the normal and neoplastic gastric epithelium and are supported by a perivascular stem cell niche. Cancer Cell 2015; 28:800–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold K, Sarkar A, Yram MA, et al. Sox2+ adult stem and progenitor cells are important for tissue regeneration and survival of mice. Cell Stem Cell 2011; 9:317–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulescu S, Ridgway RA, Cordero J, et al. Acute WNT signalling activation perturbs differentiation within the adult stomach and rapidly leads to tumour formation. Oncogene 2013; 32:2048–2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demitrack ES, Gifford GB, Keeley TM, et al. Notch signaling regulates gastric antral LGR5 stem cell function. EMBO J 2015; 34:2522–2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon E, Petke D, Boger C, et al. The spatial distribution of LGR5+ cells correlates with gastric cancer progression. PLoS One 2012; 7:e35486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang BG, Lee BL, Kim WH. Distribution of LGR5+ cells and associated implications during the early stage of gastric tumorigenesis. PLoS One 2013; 8:e82390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi HQ, Cai AZ, Wu XS, et al. Leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor 5 is associated with invasion, metastasis, and could be a potential therapeutic target in human gastric cancer. Br J Cancer 2014; 110:2011–2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Yeoh KG, Salto-Tellez M. Lgr5 expression is absent in human premalignant lesions of the stomach. Gut 2012; 61:1777–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Yang X. Smad4-mediated TGF-beta signaling in tumorigenesis. Int J Biol Sci 2010; 6:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Brodie SG, Yang X, et al. Haploid loss of the tumor suppressor Smad4/Dpc4 initiates gastric polyposis and cancer in mice. Oncogene 2000; 19:1868–1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaku K, Miyoshi H, Matsunaga A, et al. Gastric and duodenal polyps in Smad4 (Dpc4) knockout mice. Cancer Res 1999; 59:6113–6117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BG, Li C, Qiao W, et al. Smad4 signalling in T cells is required for suppression of gastrointestinal cancer. Nature 2006; 441:1015–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JN, Falck VG, Jirik FR. Smad4 deficiency in T cells leads to the Th17-associated development of premalignant gastroduodenal lesions in mice. J Clin Invest 2011; 121:4030–4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo SL, Ye H, Teng Y, et al. Akt-p53-miR-365-cyclin D1/cdc25A axis contributes to gastric tumorigenesis induced by PTEN deficiency. Nat Commun 2013; 4:2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Li C, Herrera PL, Deng CX. Generation of Smad4/Dpc4 conditional knockout mice. Genesis 2002; 32:80–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Itami S, Ohishi M, et al. Keratinocyte-specific Pten deficiency results in epidermal hyperplasia, accelerated hair follicle morphogenesis and tumor formation. Cancer Res 2003; 63:674–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 2007; 449:1003–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci 2010; 13:133–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkers J, Meuwissen R, van der Gulden H, et al. Synergistic tumor suppressor activity of BRCA2 and p53 in a conditional mouse model for breast cancer. Nat Genet 2001; 29:418–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson EL, Willis N, Mercer K, et al. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev 2001; 15:3243–3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z, Wu CJ, Chu GC, et al. SMAD4-dependent barrier constrains prostate cancer growth and metastatic progression. Nature 2011; 470:269–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinto O, Yashiro M, Toyokawa T, et al. Phosphorylated smad2 in advanced stage gastric carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2010; 10:652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson AL, Shannon NB, Lao-Sirieix P, et al. A systematic approach to therapeutic target selection in oesophago-gastric cancer. Gut 2013; 62:1415–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putoczki TL, Thiem S, Loving A, et al. Interleukin-11 is the dominant IL-6 family cytokine during gastrointestinal tumorigenesis and can be targeted therapeutically. Cancer Cell 2013; 24:257–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okines A, Cunningham D, Chau I. Targeting the human EGFR family in esophagogastric cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2011; 8:492–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Sun Y, Hou N, et al. Capn8 promoter directs the expression of Cre recombinase in gastric pit cells of transgenic mice. Genesis 2009; 47:674–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Hou N, Sun Y, Teng Y, Yang X. Atp4b promoter directs the expression of Cre recombinase in gastric parietal cells of transgenic mice. J Genet Genomics 2010; 37:647–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam KT, O'Neal RL, Coffey RJ, et al. Spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia (SPEM) in the gastric oxyntic mucosa does not arise from Lgr5-expressing cells. Gut 2012; 61:1678–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepers AG, Snippert HJ, Stange DE, et al. Lineage tracing reveals Lgr5+ stem cell activity in mouse intestinal adenomas. Science 2012; 337:730–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature 2014; 513:202–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaks V, Barker N, Kasper M, et al. Lgr5 marks cycling, yet long-lived, hair follicle stem cells. Nat Genet 2008; 40:1291–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, Ridgway RA, van Es JH, et al. Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of intestinal cancer. Nature 2009; 457:608–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Mao C, Teng Y, et al. Targeted disruption of Smad4 in mouse epidermis results in failure of hair follicle cycling and formation of skin tumors. Cancer Res 2005; 65:8671–8678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng Y, Sun AN, Pan XC, et al. Synergistic function of Smad4 and PTEN in suppressing forestomach squamous cell carcinoma in the mouse. Cancer Res 2006; 66:6972–6981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Ehdaie B, Ohara N, Yoshino T, Deng CX. Synergistic action of Smad4 and Pten in suppressing pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma formation in mice. Oncogene 2010; 29:674–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov 2012; 2:401–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal 2013; 6:pl1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Smad4 and PTEN were efficiently deleted in the progenies of Lgr5+ stem cells at gastric antrum.

Gastric antral adenoma in Smad4 and PTEN mutant mice exhibited a marked increase in proliferative cells and a complete loss of differentiated cells.

Gastric antral adenoma in Smad4 and PTEN mutant mice ectopically expressed intestinal epithelial markers.

Invasive IGC in Smad4 and PTEN compound mutant mice.

Active proliferation in IGC of Smad4 and PTEN compound mutant mice.

Gastric tumor formation in Smad4 or PTEN single mutant mice.

Invasive IGC at the gastro-forestomach/esophageal junction of Smad4 and PTEN double mutant stomach.

Invasive adenocarcinoma in the intestine and colon of Smad4 and PTEN compound mutant mice.

Smad4 deletion with combination of p53 deletion and/or KrasG12D expression in gastric Lgr5+ stem cells led to tumor formation.

Concurrent loss of Smad4 and PTEN expression in pit and parietal cells at antral region and chief cells at corpus region.

A correlation between SMAD4 gene deletion and human gastric cancer subtypes occurring at the antrum and gastro-esophageal junction (GEJ)

A correlation between PTEN gene deletion and human gastric cancer subtypes occurring at the antrum and GEJ

SMAD4 gene deletion relative to protein expression in human intestinal-type gastric cancers occurring at the antrum and GEJ

PTEN gene deletion relative to protein expression in human intestinal-type gastric cancers occurring at the antrum and GEJ

A correlation in the gene deletion between SMAD4 and PTEN in human intestinal-type gastric cancers occurring at the antrum and gastro-esophageal junction (GEJ)

SMAD4 protein expression relative to cyclin D1 in human intestinal-type gastric cancers occurring at the antrum and GEJ

PTEN protein expression relative to p-AktT308 in human intestinal-type gastric cancers occurring at the antrum and GEJ

152 human gastric cancer data from TCGA

Materials and Methods