Abstract

Background

Sixty percent of surgically resected brain metastases (BrM) recur within 1 year. These recurrences have long been thought to result from the dispersion of cancer cells during surgery. We tested the alternative hypothesis that invasion of cancer cells into the adjacent brain plays a significant role in local recurrence and shortened overall survival.

Methods

We determined the invasion pattern of 164 surgically resected BrM and correlated with local recurrence and overall survival. We performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) of >15,000 cells from BrM and adjacent brain tissue. Validation of targets was performed with a novel cohort of BrM patient-derived xenografts (PDX) and patient tissues.

Results

We demonstrate that invasion of metastatic cancer cells into the adjacent brain is associated with local recurrence and shortened overall survival. scRNAseq of paired tumor and adjacent brain samples confirmed the existence of invasive cancer cells in the tumor-adjacent brain. Analysis of these cells identified cold-inducible RNA-binding protein (CIRBP) overexpression in invasive cancer cells compared to cancer cells located within the metastases. Applying PDX models that recapitulate the invasion pattern observed in patients, we show that CIRBP is overexpressed in highly invasive BrM and is required for efficient invasive growth in the brain.

Conclusions

These data demonstrate peritumoral invasion as a driver of treatment failure in BrM that is functionally mediated by CIRBP. These findings improve our understanding of the biology underlying postoperative treatment failure and lay the groundwork for rational clinical trial development based upon invasion pattern in surgically resected BrM.

Keywords: brain metastasis, leptomeningeal, recurrence, scRNAseq, stereotactic radiosurgery

Key Points.

Invasion into the brain is associated with recurrence in surgically resected brain metastases.

scRNAseq reveals distinct transcriptional profiles in metastatic cells that have invaded into the brain.

Importance of the Study.

We demonstrate a critical role for invasive growth as a driver of poor outcomes in patients with brain metastases. These findings have direct implications for practicing neurosurgeons, neuropathologists, and radiation oncologists in the management of patients with surgically resected brain metastases and lay the groundwork for clinical trials incorporating invasion pattern as a prognostic or predictive biomarker.

Brain metastases (BrM) occur in 20%-40% of cancer patients, most commonly in patients with primary cancers of the lung, breast, and skin.1 While longevity and quality of life for BrM patients are poor, treatment options exist to improve outcomes.2 These include surgery, whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT), stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), and systemic treatments such as targeted and immune-modulating therapies.2 Determining which treatment or combination of treatments is appropriate depends on the cancer type, patient performance status, systemic disease burden, targeted therapy options, and the number, size, and site of BrM.2

Surgical resection is the standard treatment for large and symptomatic BrM. However, approximately 60% of patients with postoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-confirmed total resections will suffer a local recurrence within 1 year.3,4 For this reason, WBRT or SRS with a 1-2 mm margin surrounding the surgical resection cavity is often delivered as an adjuvant treatment.4,5 WBRT reduces the risk of local recurrence by 80% but is associated with severe adverse events.3 SRS reduces the risk of local recurrence by 50% and has fewer adverse events than WBRT.4

Since local recurrence is common and the negative effects of radiotherapy are significant, understanding why some BrM recur following a total resection is a clinically important and unresolved question. For over 30 years, clinicians and researchers have hypothesized that local recurrence results from the surgical dispersion of cancer cells into the cavity, which grow following attachment to the cavity wall, and that postoperative radiotherapy eliminates a large percentage of these cells.3,6,7 The only existing evidence supporting this hypothesis is that en-bloc resections are less likely to result in local recurrence compared to piecemeal resections.8,9

Since WBRT more effectively prevents local recurrence than SRS, which targets only 1-2 mm of the surgical resection margin,5 we hypothesized that brain metastatic cancer cells may engage invasive programs that drive their invasion into the adjacent brain. This possibility is not currently thought to be the cause of local recurrence because of the well-circumscribed appearance of BrM using brain imaging and their macroscopic appearance.10 However, evidence does exist to suggest that BrM are not necessarily invasion incompetent.11,12

To address the potential role of cancer cell invasion in BrM, we dichotomized surgically resected BrM into two groups based on their invasion pattern. The first group contains minimally invasive (MI) BrM that display limited or no invasion into the brain parenchyma. The second group comprises highly invasive (HI) lesions exhibiting marked invasion of cancer cells, as clusters or single cells, into the surrounding brain. We demonstrate, using a large cohort of annotated BrM specimens with associated neuroimaging data, that patients with HI BrM exhibit a greater probability of experiencing postoperative local recurrence and shortened overall survival compared to those with MI lesions. scRNAseq of paired HI BrM and adjacent brain samples confirmed the presence of invasive cancer cells in the tumor-adjacent brain. These invasive cancer cells overexpressed cold-inducible RNA-binding protein (CIRBP), a gene also overexpressed in HI compared to MI BrM. To study the role of CIRBP in HI BrM, we established a biobank of patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models of BrM that faithfully recapitulate the invasion pattern observed in patients and which confirmed the function of CIRBP in efficient growth of HI BrM.

Methods

Ethics Statement

All patient information and specimens were obtained after written informed consent and were de-identified. Studies were conducted in accordance with the 1996 Declaration of Helsinki and approved by institutional review boards of McGill University and the Montreal Neurological Institute-Hospital (MNIH) (IRB # 2018-4150). Operations performed on all patients occurred at the MNIH between 2007 and 2019. For animal studies, the methods used were in accordance with standards set by the institutional animal care and use committee at the Goodman Cancer Research Centre under animal use protocol number 2001-4830.

Clinical Specimen Analysis and Chart Reviews

Available H&E slides from all patients in the initial cohort of 284 BrM were screened for cancer-brain interface and scored for invasion pattern by two observers, including one neuropathologist. Scores were averaged when the two reviewers provided divergent assessments. A detailed outline of the scoring system and definition of clinical endpoints used can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

BrM samples were procured at the MNIH under a protocol approved by the MNIH IRB (NEU-10-066) following patient consent. Samples were obtained from within and just outside of the contrast-enhancing area of the lesion. Details pertaining to sample preparation and analysis can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

Orthotopic PDX Models of BrM

Orthotopic PDX models of BrM were established as previously described.13 Further details are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Tissue Microarrays (TMA)

TMAs were constructed using a TMA Grand Master (3DHISTECH) platform. TMA details are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC was performed using the Ventana Benchmark Ultra Autostainer using the antibodies and concentrations described in the Supplementary Methods.

shRNA-Mediated CIRBP Knockdown and cDNA Overexpression

CIRBP knockdown (KD) was performed using shRNA clones from a lentivirus derived MISSION shRNA library (Sigma). CIRBP overexpression constructs (Supplementary Methods) were verified by sequencing. Plasmids were packaged into lentiviral particles in 293T cells (ATCC, CRL-3216) and used to infect cells with 1× polybrene.

Lentiviral Infection of PDX Models

Subcutaneous tumors were dissociated and subjected to short-term suspension culture in tumorsphere media (Supplementary Methods). Cells were immediately infected with pHIV-Luc-ZsGreen lentivirus (Addgene #39196). Luciferase-labeled cancer cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline and intracranially injected into NSG mice. Luminescence signals were quantified using an IVIS Spectrum (PerkinElmer) instrument.

Immunoblotting

Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis as previously described.13 Antibody details are described in Supplementary Methods.

Statistical Tests

The following statistical tests were used, as indicated in the appropriate figure legend: Kaplan-Meier estimator, log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test, two-sided Mann-Whitney test, Pearson’s Chi-Square, two-sided Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test.

Results

HI Histopathology Is Associated With Poor Patient Outcomes

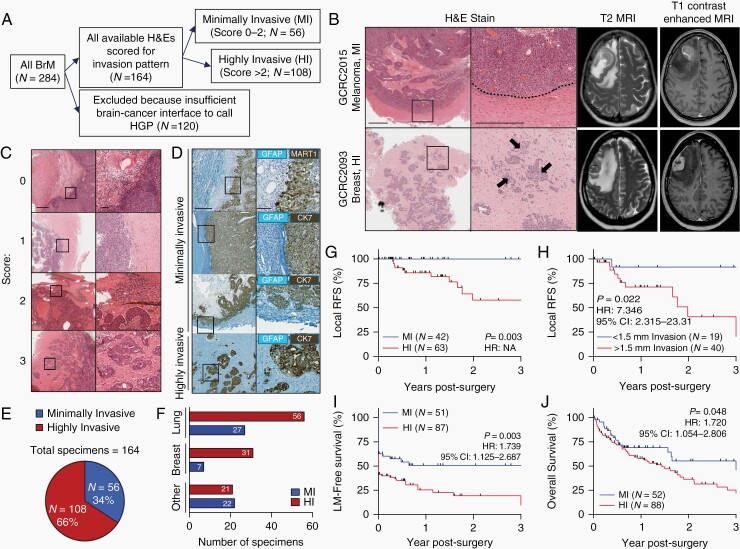

We assessed invasion pattern in 284 consecutive BrM resections. After excluding 120 BrM with inadequate brain-cancer interface that prevented an invasion pattern designation, 164 specimens from 147 patients were included in the cohort (Figure 1A, Supplementary Table S1). While varying degrees of invasion are detectable by histopathology, these differences are indistinguishable by MRI (Figure 1B). These samples were scored for invasion pattern by two independent observers blinded to clinical outcomes using a scoring system for invasion that spanned from 0 to 3. An average score of 0-2 denoted lesions with no or limited invasion into the brain (MI) while an average score >2 indicated lesions with extensive invasion into the adjacent brain (HI) (Figure 1C and D). 56 BrM (34%) from 54 patients (37%) showed a MI pattern while 108 samples (66%) from 93 patients (63%) had HI lesions that included cancer cell clusters or single cells invading the brain parenchyma (Figure 1E). BrM originating from primary breast cancers were more likely to demonstrate a HI pattern relative to those derived from non-breast primary tumors (Figure 1F, Supplementary Table S2).

Fig. 1.

HI invasion pattern predicts poor outcome in patients with surgically resected brain metastases. A, Flow diagram representing the inclusion process for incorporating patient specimens into the cohort. B, Representative H&E images demonstrating MI (top) and HI (bottom) brain metastases (left). A dotted line represents the well-demarcated margin in a MI lesion and arrows point to invasive tumor cell clusters in a HI lesion. Scale bars: 1 mm (left panel), 500 µm (right panel). Matched T2 and T1 contrast-enhanced MRI scans from the same patients (right). C, H&E (Scale bars: 1 mm—left panels, 100 µm—right panels) and D, Two-color IHC (Teal-GFAP, Dab-CK7/MART1) demonstrating examples of the scoring system used to define invasion pattern. Scale bars: 500 µm—left panels, 100 µm—right panels. E, Proportion of MI and HI brain metastases identified in the cohort. F, Breakdown of invasion pattern by primary cancer type. G, Kaplan-Meier curve plotting local recurrence-free survival (local RFS) in patients with MI vs HI brain metastases. Their removal by gross total resection was confirmed by postoperative MRI and were not themselves locally recurrent lesions. P value calculated by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test, hazard ratio (HR) unable to be calculated because no local recurrence events occurred in the MI group. H, Kaplan-Meier curve plotting local RFS in patients harboring specimens with at least 2 mm of adjacent brain needed to calculate distance of invasion of greater or less than 1.5 mm. P value, HR, and 95% confidence interval (CI) calculated by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. I, Kaplan-Meier curve plotting leptomeningeal metastasis-free survival (LM-free survival) in patients with MI vs HI brain metastases, calculated from the time of the patient’s first neurosurgical resection. P value, HR, and 95% CI calculated by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. J, Kaplan-Meier curve plotting overall survival in patients with MI vs HI brain metastases, calculated from the time of the patient’s first neurosurgical resection. P value, HR, and 95% CI calculated by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Abbreviations: HI, highly invasive; IHC, immunohistochemistry; MI, minimally invasive.

In patients who had multiple BrM resected either temporally (locally recurrent BrM) or spatially (anatomically distinct BrM), the invasion pattern was preserved in 16/16 matched pairs, affirming the notion that BrM within the same patient are genomically homogeneous,11,14 and suggesting that invasion pattern is intrinsic to a patient’s cancer (Supplementary Table S3).

A HI invasion pattern is associated with local recurrence in previously untreated lesions with complete macroscopic gross total resections confirmed by postoperative MRI (Figure 1G, Supplementary Figure S1). We corroborated these findings by calculating the distance of invasion from the cancer-brain interface to the most deeply invaded cancer cell detectable on a representative H&E slide. This approach provided a quantifiable metric for invasion, with only specimens harboring >2 mm of measurable brain parenchymal margin included in the analysis (N = 59). Using a threshold of 1.5 mm of invasion from the edge of the main cancer mass to represent the 1-2 mm SRS margins used, we observed that specimens with >1.5 mm of invasion were more likely to experience local recurrence compared to those with <1.5 mm of invasion (Figure 1H). Patients with leptomeningeal enhancement at the time of surgery experienced similar rates of local recurrence compared to those who did not, ruling out leptomeningeal metastases (LM) as drivers of local recurrence (Supplementary Figure S1J).

Among patients with at least one contrast-enhanced MRI scan, those with a HI invasion pattern were more likely to have or develop contrast-enhancing lesions in the leptomeninges (Figure 1I, Supplementary Figure S2). This phenotype is driven by a greater percentage of patients with HI BrM exhibiting LM at the time of surgery, as determined by a neuroradiologist blinded to invasion pattern (51/87 HI patients vs 19/51 MI patients, Pearson’s Chi-Square 5.87, P = .015). Patients with a HI invasion pattern experienced inferior overall survival compared to those with MI invasion pattern (Figure 1J, Supplementary Figure S3), although the specific cause of death was unavailable in the health records of patients. Together, these findings establish the prognostic significance of invasion pattern for patients with surgically resected BrM.

We identify three distinct invasion subtypes within HI specimens—angiocooptive, diffuse, and lobular (Supplementary Figure S4A), in line with the existing literature.14 Lobular is the most common subtype, particularly BrM derived from breast and lung primary tumors (Supplementary Figure S4B). While sample size is limiting within each category, we observe poor prognosis in patients with diffusely invasive BrM compared to the lobular invasion subtype (Supplementary Figure S4C-E).

Invasive Brain Metastatic Cancer Cells Exhibit Altered Transcriptional Profiles Compared to Cancer Cells Within the Bulk Metastases

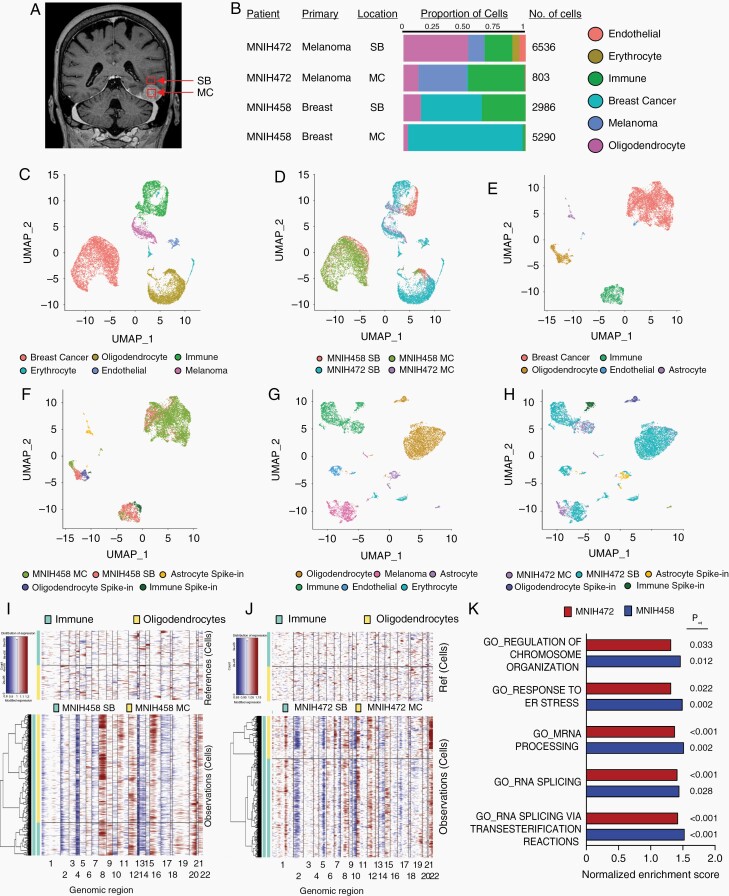

To confirm the existence of cancer cells in the tumor-adjacent brain and compare their transcriptome to those in the metastatic lesion from which they were derived, we performed droplet-based scRNAseq analysis of 15,615 cells derived from two paired HI BrM specimens (MNIH458; Breast and MNIH472; Melanoma). We obtained two samples from each patient; one was taken from the contrast-enhancing BrM (metastasis center, MC; Figure 2A), and the second was collected from the surrounding brain outside of the resection cavity (surrounding brain, SB). The identity of various cell types was determined by generating a cell atlas and using the expression of cell type-specific markers on the uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) representation, revealing clusters of breast cancer (GATA3+), melanoma (PMEL+), oligodendrocytes (OLIG1+), macrophages/microglia (C1QC+), endothelial cells (CLDN5+), and erythrocytes (HBA1+) (Figure 2B-D, Supplementary Figure S5). Cancer cell clusters in each pair were better resolved by implementing clusters of characterized spike-in populations of healthy adult oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and macrophages/microglia (Figure 2E-H).15,16 Confirmation of copy number variants was performed in the cancer cell clusters from each BrM pair (Figure 2I and J) and analysis of markers of each cluster (Supplementary Figure S6). Each pair was analyzed individually in order to identify gene expression profiles in cancer cells from MC and SB. In keeping with the invasive nature of these BrM, we identified abundant cancer cells present in non-enhancing SB from both patients (Figure 2F and H).

Fig. 2.

Single-cell transcriptome profiling of HI brain metastases and adjacent brain reveals abundant invading cells with distinct gene expression profiles. A, Patient MRI outlining the sampling approach whereby two samples were sequenced from each patient: from the contrast-enhancing cancerous region (metastasis center, MC), and from the non-enhancing region peripheral to the lesion (surrounding brain, SB). B, Proportion of cell types identified from each cluster in each sample and the total number of cells sequenced. C, UMAP plot indicating clusters of cells derived from the entire dataset. D, UMAP plot indicating sample identity of the cells in the dataset. E, UMAP plot indicating clusters of cells derived from patient MNIH458 (breast primary). F, UMAP plot indicating sample identity of the cells in the MNIH458 dataset. G, UMAP plot indicating clusters of cells derived from patient MNIH472 (melanoma primary). H, UMAP plot indicating sample identity of the cells in the MNIH472 dataset. I, Copy number variant analysis comparing the cancer cell cluster in MNIH458 and J, MNIH472 patient samples with defined noncancerous oligodendrocyte and macrophage/microglia/immune cell clusters derived from noncancerous clusters in the same samples and spike-in cells derived from white matter on the way to resection in two epilepsy patients and white/grey matter distant to a glioblastoma lesion. K, Gene set enrichment analysis for gene ontology biological processes overexpressed in cancer cells from SB vs MC from each of the two pairs. All gene sets where Padj < 0.05 for both pairs are shown. Abbreviations: HI, highly invasive; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

To narrow our search to genes functionally involved in BrM invasive growth, we performed gene set enrichment analysis, querying gene ontology biological process signatures. This analysis revealed 33 and 8 gene sets overexpressed in SB vs MC cancer cells from MNIH458 and MNIH472, respectively. Intersection of these two lists of gene sets yielded 5 common gene sets that center around functions related to mRNA biology and cellular responses to stress (Figure 2K). To identify a putative functional mediator of invasive growth, we next identified individual genes that were differentially expressed between cancer cells in the SB vs MC. This revealed 17 overexpressed (Supplementary Table S4) and 7 downregulated genes in the invasive cancer cells (Supplementary Table S5). One of these genes, CIRBP, is a mRNA-binding protein with known functions in cellular adaptation to stressors similar to those that may be encountered by cancer cells invading into the adjacent brain.17–19

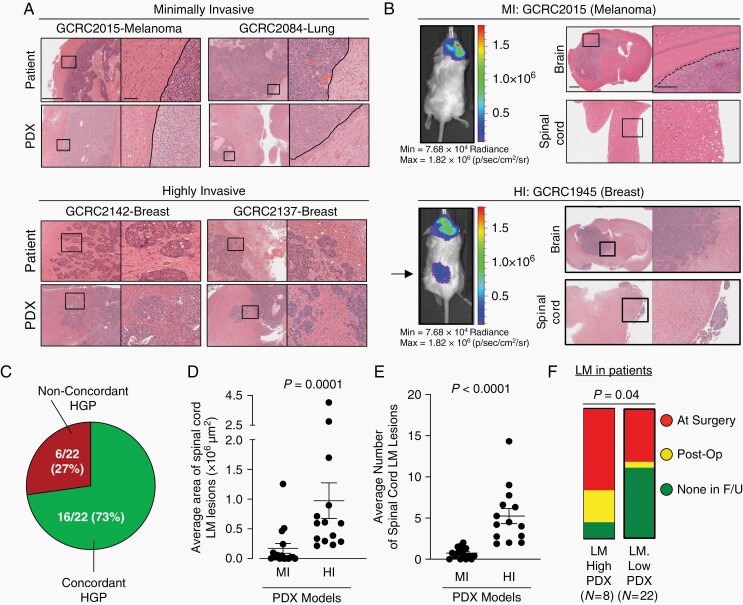

PDX Models of BrM Recapitulate Invasion and LM Phenotypes

To functionally validate the role of CIRBP in HI BrM, we established 30 PDX models from human BrM (16 lung, 8 breast, 4 melanoma, 2 gastrointestinal primaries). When implanted orthotopically in the brain of immune-compromised mice, the invasion pattern observed in PDX models were consistent with the patient from which they were derived. Indeed, 16/22 (73%) of evaluable PDX-patient pairs displayed concordant invasion pattern (Figure 3A-C, Supplementary Figure S7). PDX BrM models revealed concordant levels and staining patterns for routinely used pathological markers compared to the patient specimens from which they were derived, including CD45 staining as a quality control measure to assure that PDXs truly represent solid cancers and not lymphocyte outgrowth (Supplementary Table S6, Supplementary Figure S8).

Fig. 3.

PDX models of brain metastasis retain invasion pattern from patient of origin and are associated with patterns of leptomeningeal dissemination. A, Examples of margins from MI (top) and HI (bottom) PDX models of brain metastasis with matched patient specimens demonstrating the same invasion pattern. Scale bars: 1 mm (low magnification), 100 µm (high magnification). B, Representative images of PDX models with MI invasion pattern (top) remaining localized in the brain parenchyma while those with HI invasion pattern (bottom) are more likely to develop leptomeningeal metastases surrounding the brain and spinal cord, shown by both IVIS (left; arrow points to spinal cord leptomeningeal metastases) and histology (right). Scale bars: 1 mm, 500 µm. C, Ratio of invasion pattern concordance between patient and matched PDX models D, Quantification of leptomeningeal metastases area (µm2 per mouse spinal cord) and E, number of lesions, between MI (n = 16) and HI (n = 14) independent brain metastasis PDX models. For each PDX model, 1 H&E-stained slide from 3 to 5 mice were assessed and averaged for analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using a two-sided Mann-Whitney test. F, High- and low-LM-forming PDXs with associated patient information on the development of radiographically confirmed LM. Patients from whom LM-high-forming PDXs were established were more likely to have or develop LM than patients from whom LM-low-forming PDXs were established (Pearson’s Chi-Square 4.2236, P = .04). LM-high-forming PDXs are defined as those models that develop of an average equal to or greater than 4 distinct spinal cord LM lesions with a cancer cell area of >250 00 00 µm2 per mouse H&E-stained spinal cord analyzed. Abbreviations: HI, highly invasive; MI, minimally invasive; LM, leptomeningeal metastases; PDX, patient-derived xenografts.

Interestingly, we noted that PDX models exhibited varying degrees of LM along the spinal cord. In agreement with our clinical findings, PDXs with HI invasion pattern exhibit a greater degree of leptomeningeal dissemination along the spinal cord (Figure 3B). Indeed, mice harboring HI BrM displayed larger and more numerous LM lesions along the spinal cord when compared to mice with MI lesions (Figure 3D and E). We established criteria for PDX models to be dichotomized as high- vs low-LM-forming (≥4 leptomeningeal lesions and cancer cell area >250 00 00 µM2 per spinal cord analyzed by H&E) and observed that the patients whose BrM led to high-LM-forming PDXs were more likely to have developed LM than patients whose BrM gave rise to low-LM-forming PDXs (Figure 3F).

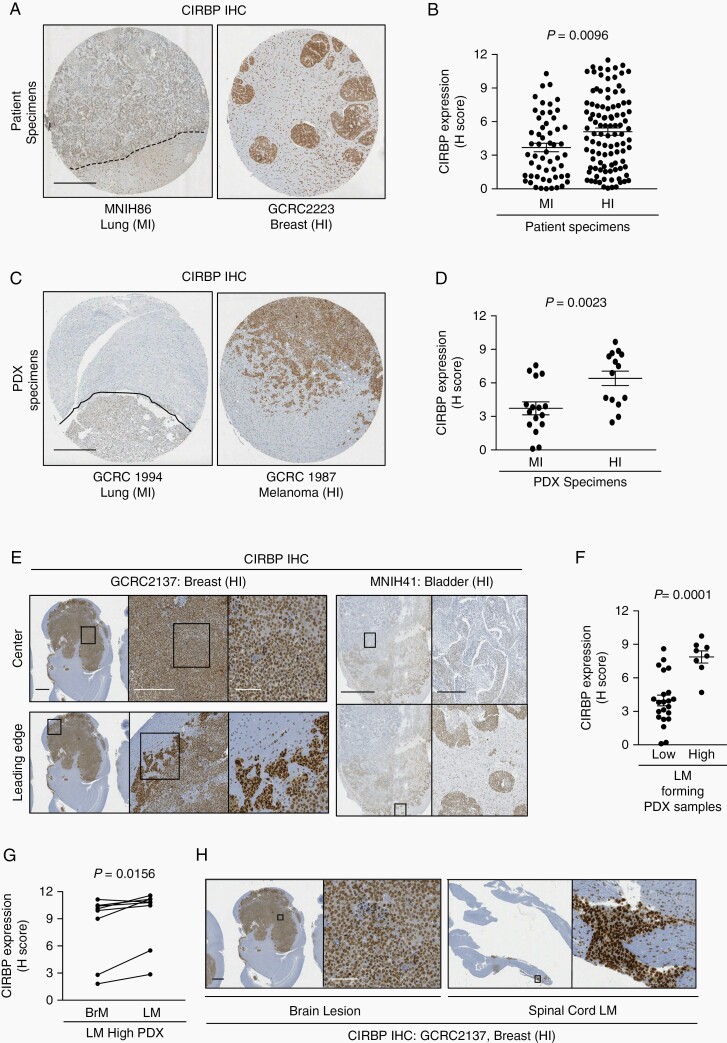

CIRBP Is Overexpressed in HI BrM and Is Required for Efficient Invasive Growth in the Brain

We established TMAs containing 157 human and 30 PDX BrM specimens with annotated invasion pattern. TMA slides were stained by IHC for CIRBP and the specific signal within tumor cells was quantified. These analyses revealed significant overexpression of CIRBP in HI compared to MI BrM from both human and PDX cohorts (Figure 4A-D). CIRBP expression was also higher in cancer cells at the leading edge of HI PDX models and patient BrM when compared to cancer cells in the center of the lesion, in concordance with aforementioned scRNAseq data (Figure 4E). In PDX specimens, CIRBP expression was elevated in the parenchymal BrM of high-LM-forming PDXs compared to low-LM-forming PDXs (Figure 4F). Within the high-LM-forming PDX models, the LM from 7 out of 8 models expressed higher levels of CIRBP compared to the matched parenchymal BrM (Figure 4G and H). Together, we demonstrate that CIRBP expression is associated with parenchymal invasion and leptomeningeal dissemination in human BrM and PDX models.

Fig. 4.

CIRBP is associated with HI invasion pattern in BrM. CIRBP expression in MI and HI BrM from a tissue micro-array of A and B, patient specimens; C and D, PDX models. Representative images of MI (left) and HI (right) lesions shown in A and C. Dotted lines represent the well-demarcated margin in MI lesions. Scale bars: 500 µm. Quantification of staining shown in B and D. H-Score was calculated as a score out of 12 that encompasses percentage positivity and staining intensity by the following formula: (% positivity/25) × ((1× % of 1+ cells) + (2× % of 2+ cells) + (3× % of 3+ cells)). Statistical analyses were performed using a two-sided Mann-Whitney test. E, Representative examples demonstrating overexpression of CIRBP at the leading edge of parenchymal brain lesion in a PDX model (left) and patient specimen (right). Scale bars: 1 mm, 500 µm, 100 µm and 5 mm, 500 µm, respectively. F, CIRBP expression in low- and high-LM-forming PDX models. Statistical analyses were performed using a two-sided Mann-Whitney test. G, Fold-change comparing CIRBP H-score in spinal cord LM compared to parenchymal BrM in high-LM-forming PDX models. Statistical analyses were performed using a two-sided Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. H, Representative example demonstrating overexpression of CIRBP in spinal cord LM compared to parenchymal brain lesion. Scale bars: 1 mm, 100 µm. Abbreviations: BrM, brain metastases; CIRBP, cold-inducible RNA-binding protein; HI, highly invasive; MI, minimally invasive; LM, leptomeningeal metastases; PDX, patient-derived xenografts.

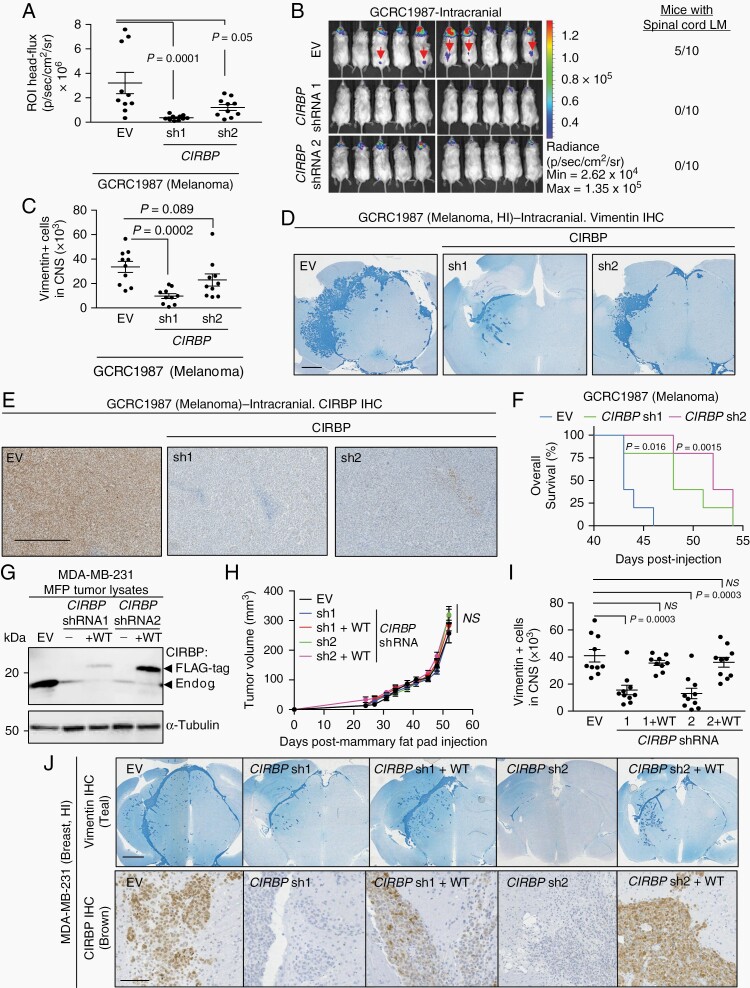

Next, we sought to validate CIRBP’s function in the development of BrM by performing CIRBP shRNA KD in luciferase-labeled cancer cells derived from a HI melanoma BrM PDX model (GCRC1987). This model was chosen due to the fact that mice bearing cranial injections of GCRC1987 developed significant LM along the spinal cord. When injected intracranially, CIRBP KD in the GCRC1987 model suppresses cancer growth in both the brain parenchyma and spinal cord leptomeninges by bioluminescence imaging (Figure 5A and B) and histopathology (Figure 5C and D). In a separate cohort, animals bearing intracranially injected GCRC1987 cells with CIRBP KD had prolonged overall survival compared to mice injected with empty vector (EV) control GCRC1987 cells (Figure 5E and F). We observe a decrease in the proliferative marker KI67 and phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) by IHC in CIRBP KD BrM, consistent with existing evidence that CIRBP is known to promote ERK signaling and proliferation (Supplementary Figure S9).20

Fig. 5.

CIRBP expression modulates efficient invasive growth of BrM. Cranial injection of 1 × 105 GCRC1987 melanoma cells. A, Quantification of bioluminescence signal in the head of mice at experimental endpoint. Mann-Whitney test: EV vs CIRBP sh1: P = .0001, EV vs CIRBP sh2: P = .05. B, Bioluminescence images showing reduction in head signal in CIRBP shRNA cohorts compared to EV cohort. Spinal cord leptomeningeal metastases (arrows) were identified in 5/10 EV mice but 0/10 CIRBP shRNA mice from each independent shRNA. C, Quantification of cancer cells (Vimentin +) in CNS at experimental endpoint by histopathology. Mann-Whitney test: EV vs CIRBP sh1: P = .0002, EV vs CIRBP sh2: P = .0892. D, Representative images of Vimentin IHC (Teal) from (C). Scale bar: 1 mm. E, CIRBP IHC from GCRC1987 EV and CIRBP shRNAs. Scale bar: 500 µm. F, Survival of GCRC1987 EV and CIRBP shRNAs. P value calculated by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test: EV vs CIRBP sh1: P = .016, HR: 2.947, 95% CI: 0.7088-12.26, EV vs CIRBP sh2: P = .0015, HR: 4.122, 95% CI: 0.863-19.69. G, Immunoblot of MDA-MB-231 mammary fat pad tumor lysates expressing an empty vector (EV) control, shRNA knockdown of CIRBP (sh1 and sh2) and shRNA knockdown with overexpression of wild-type (WT) FLAG-tagged CIRBP. Lower arrow points to the endogenous CIRBP band and the upper arrow points to the FLAG-tagged overexpressed CIRBP. H, Mammary fat pad tumor growth of 1 × 105 parental MDA-MB-231 cells and cells expressing EV, CIRBP knockdown (sh1 and sh2), and WT CIRBP rescues. P > .05 for all comparators by Mann-Whitney test. I, Cranial injection of 1 × 105 parental MDA-MB-231 cells and cells expressing EV, CIRBP knockdown (sh1 and sh2), and shRNA knockdown with overexpression of WT FLAG-tagged CIRBP at experimental endpoint. Quantification of cancer cells (Vimentin +) in CNS. Mann-Whitney test: EV vs sh1: P = .0003 EV vs sh2: P = .0003, EV vs sh1+WT: P > .999, EV vs sh2+WT: P = .4813. J, Representative images of Vimentin (top) and CIRBP (bottom) IHC from (I). Scale bar: top—1 mm, bottom—100 µm. Abbreviations: BrM, brain metastases; CIRBP, cold-inducible RNA-binding protein; EV, empty vector; HR, hazard ratio; IHC, immunohistochemistry.

We next employed a MDA-MB-231 triple negative breast cancer cell model that forms HI BrM when injected intracranially. In this model, cells preferentially seed in the subarachnoid space and invade into the brain parenchyma, a finding observed frequently in histopathology of patients with HI BrM. We established shRNA KD of CIRBP in these MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 5G). When implanted in the mammary fat pad to model primary tumor growth in the breast, there were no significant differences in growth of MDA-MB-231 EV-expressing cells and those with KD and rescue of CIRBP (Figure 5G and H). However, when injected intracranially, MDA-MB-231 cells harboring two independent stable KDs of endogenous CIRBP grow markedly less in the central nervous system (CNS) compared to EV-expressing cells, which develop HI lesions (Figure 5I and J). This reduction is rescued by re-expression of CIRBP in both cell populations harboring independent CIRBP shRNAs (Figure 5I and J). Together, these results demonstrate a critical role for CIRBP in the efficient growth of HI BrM.

Discussion

Clinicians and researchers generally conceptualize BrM as noninvasive masses that appear to be well-demarcated from the adjacent brain parenchyma by MRI.21 However, this cannot be reconciled with the high local recurrence rate after surgical resection. Histopathological evidence suggests that BrM can invade the brain.11,12 The hypothesis that invading metastatic cells beyond the resection cavity play a role in poor prognosis can be supported by scattered reports in the clinical literature. Notably, >50% of BrM patients treated with gross total surgical resection alone recur locally without postoperative radiation to the area around the resection cavity.3,4 Local disease control has been shown to be improved marginally by performing microscopic total resection to achieve negative margins or by treating 1-2 mm of the surgical margin with postoperative radiotherapy.5,22 This suggests the importance of eliminating invasive cancer cells beyond the contrast-enhancing margin to achieve local disease control.

While invasion pattern in BrM has been previously described, these studies have either used autopsy specimens in a nonsurgical population,11,12 or were underpowered to identify the strong correlations between invasion pattern and local recurrence or the formation of LM identified herein.12 In this study, we identify invasion pattern as an important prognostic factor for patients with surgically resected BrM. This finding has important clinical implications that can be studied in randomized controlled trials. First, one can ask whether HI BrM patient outcomes can be improved by expanding the postoperative SRS field, delivering multi-fraction SRS or by applying new surgical tools or techniques, such as Raman spectroscopy, to identify and remove invading metastatic cells in the brain.23 One may also ask whether there is clinical value in sparing patients with MI BrM from postsurgical delivery of SRS altogether if they indeed comprise the group of patients who would never recur postoperatively even in the absence of postoperative radiation. With the answers to these questions, it is indeed plausible that invasion pattern can guide management of surgical BrM patients.

scRNAseq has allowed us to profile BrM and the adjacent brain, revealing the transcriptomes of >15,000 cells. We focus our studies on the cancer cells themselves, where we identified pathways related to mRNA biology and cellular stress responses in distantly invaded cancer cells compared to those in the MC. This led us to identify CIRBP as a gene overexpressed in HI BrM with a functional role in BrM development and colonization of the leptomeninges. CIRBP has well-characterized roles in cancer initiation, progression, and invasion, but has yet to be studied in the context of metastasis in vivo.18 CIRBP is an RNA-binding protein that may exert its function in the context of HI BrM by binding to select mRNA transcripts involved in mitigating reactive oxygen species or promoting survival in the stressful microenvironment of the CNS.24 Alternatively, secreted CIRBP may be critical in modulating crosstalk with the neuroinflammatory stroma and may mediate invasive growth in this capacity.25 These findings highlight the potential offered by therapeutically targeting CIRBP or its downstream mRNA targets in the treatment of HI BrM.

We modeled invasion pattern with an extensive cohort of BrM PDXs. Our results from these models corroborate our clinical findings that HI invasion pattern is associated with LM. Previous studies suggest some BrM may dynamically shuttle between the CNS compartments of the brain parenchyma and the leptomeninges.26 Whether this is caused by a true invasive process between the brain and leptomeninges, or one that is associated with enhanced cell survival in the leptomeningeal compartment mediated by genes upregulated in HI BrM, such as CIRBP, remains unclear.

This work together challenges the paradigm by which clinicians and researchers perceive BrM as uniformly circumscribed masses. We demonstrate robust clinical evidence that BrM frequently exhibit meaningful degrees of invasion that correlate with patient outcomes and identify CIRBP as a functional mediator of this process.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients and their families who donated the tissues studied in this work, the operating room team at the MNIH, the McGill/GCRC Histology core facility, the McGill Comparative Medicine and Animal Resources Centre, and the McGill Platform for Cellular Perturbation. We acknowledge the assistance of Valentina Muñoz Ramos, Margarita Souleimanova, Veena Sangwan, Carmen Sabau, Vasilios Papavasiliou, Anie Monast, Sébastien Tabariès, and members of the Siegel and Petrecca laboratories.

Funding

M.D. acknowledges funding from McGill MD/PhD Program, Brain Tumour Foundation of Canada, and Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarships. P.M.S. is a McGill University William Dawson Scholar, M.P. is a James McGill Professor and holds the Diane and Sal Guerrera Chair in Cancer Genetics. This research has been supported by grants from the Terry Fox Foundation and the Quebec Breast Cancer Foundation (Grant #: 251427-251690 to P.M.S.), by the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec and the Quebec Breast Cancer Foundation, to M.P., by Genome Canada Genome Technology Platform and the Canada Foundation for Innovation (to J.R. and G.B.).

Conflict of interest statement. The authors have declared that no conflicts of interest exist.

Author contributions. Designing research studies: M.D., M.C.G., S.L., K.P., and P.M.S. Conducting experiments: M.D., P.U.L., and D.Z. Acquiring data: M.D., T.A.S., W.Q.Y., S.M.M., H.A., M.C.G., and S.L. Analyzing data: M.D., M.C., V.O., J.N., C.P.C., J.M., and H.D. Providing reagents: R.E., M.G.A., N.S.N., P.S., R.J.D., and K.P. Writing manuscript: M.D., C.P.C., P.S., M.P., M.C.G., S.L., K.P., and P.M.S. Supervision of study: G.B., J.R., M.P., M.C.G., S.L., K.P., and P.M.S.

References

- 1.Patchell RA. The management of brain metastases. Cancer Treat Rev. 2003;29(6):533–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suh JH, Kotecha R, Chao ST, Ahluwalia MS, Sahgal A, Chang EL. Current approaches to the management of brain metastases. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17(5):279–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF, et al. . Postoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of single metastases to the brain: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1998;280(17):1485–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahajan A, Ahmed S, McAleer MF, et al. . Post-operative stereotactic radiosurgery versus observation for completely resected brain metastases: a single-centre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(8):1040–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown PD, Ballman KV, Cerhan JH, et al. . Postoperative stereotactic radiosurgery compared with whole brain radiotherapy for resected metastatic brain disease (NCCTG N107C/CEC·3): a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(8):1049–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Routman DM, Yan E, Vora S, et al. . Preoperative stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases. Front Neurol. 2018;9:959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Walsh JW, et al. . A randomized trial of surgery in the treatment of single metastases to the brain. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(8):494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel AJ, Suki D, Hatiboglu MA, et al. . Factors influencing the risk of local recurrence after resection of a single brain metastasis. J Neurosurg. 2010;113(2):181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahn JH, Lee SH, Kim S, et al. . Risk for leptomeningeal seeding after resection for brain metastases: implication of tumor location with mode of resection. J Neurosurg. 2012;116(5):984–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cha S. Neuroimaging in neuro-oncology. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6(3):465–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berghoff AS, Rajky O, Winkler F, et al. . Invasion patterns in brain metastases of solid cancers. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(12):1664–1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siam L, Bleckmann A, Chaung HN, et al. . The metastatic infiltration at the metastasis/brain parenchyma-interface is very heterogeneous and has a significant impact on survival in a prospective study. Oncotarget. 2015;6(30):29254–29267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dankner M, Lajoie M, Moldoveanu D, et al. . Dual MAPK inhibition is an effective therapeutic strategy for a subset of Class II BRAF mutant melanomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(24):6483–6494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brastianos PK, Carter SL, Santagata S, et al. . Genomic characterization of brain metastases reveals branched evolution and potential therapeutic targets. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(11):1164–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wheeler MA, Clark IC, Tjon EC, et al. . MAFG-driven astrocytes promote CNS inflammation. Nature. 2020;578(7796):593–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perlman K, Couturier CP, Yaqubi M, et al. . Developmental trajectory of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells in the human brain revealed by single cell RNA sequencing. Glia. 2020;68(6):1291–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liao Y, Tong L, Tang L, Wu S. The role of cold-inducible RNA binding protein in cell stress response. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(11):2164–2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang ET, Parekh PR, Yang Q, Nguyen DM, Carrier F. Heterogenous ribonucleoprotein A18 (hnRNP A18) promotes tumor growth by increasing protein translation of selected transcripts in cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7(9):10578–10593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klotz R, Thomas A, Teng T, et al. . Circulating tumor cells exhibit metastatic tropism and reveal brain metastasis drivers. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(1):86–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Artero-Castro A, Callejas FB, Castellvi J, et al. . Cold-inducible RNA-binding protein bypasses replicative senescence in primary cells through extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(7):1855–1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nathoo N, Chahlavi A, Barnett GH, Toms SA. Pathobiology of brain metastases. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(3):237–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoo H, Kim YZ, Nam BH, et al. . Reduced local recurrence of a single brain metastasis through microscopic total resection. J Neurosurg. 2009;110(4):730–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jermyn M, Mok K, Mercier J, et al. . Intraoperative brain cancer detection with Raman spectroscopy in humans. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(274):274ra219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lujan DA, Ochoa JL, Hartley RS. Cold-inducible RNA binding protein in cancer and inflammation. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2018;9(2). doi: 10.1002/wrna.1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiang X, Yang WL, Wu R, et al. . Cold-inducible RNA-binding protein (CIRP) triggers inflammatory responses in hemorrhagic shock and sepsis. Nat Med. 2013;19(11):1489–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allen JE, Patel AS, Prabhu VV, et al. . COX-2 drives metastatic breast cells from brain lesions into the cerebrospinal fluid and systemic circulation. Cancer Res. 2014;74(9):2385–2390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.